Abstract

CD20 monoclonal antibody (mAb) immunotherapy is effective for lymphoma and autoimmune disease. In a mouse model of immunotherapy using mouse anti–mouse CD20 mAbs, the innate monocyte network depletes B cells through immunoglobulin (Ig)G Fc receptor (FcγR)-dependent pathways with a hierarchy of IgG2a/c>IgG1/IgG2b>IgG3. To understand the molecular basis for these CD20 mAb subclass differences, B cell depletion was assessed in mice deficient or blocked for stimulatory FcγRI, FcγRIII, FcγRIV, or FcR common γ chain, or inhibitory FcγRIIB. IgG1 CD20 mAbs induced B cell depletion through preferential, if not exclusive, interactions with low-affinity FcγRIII. IgG2b CD20 mAbs interacted preferentially with intermediate affinity FcγRIV. The potency of IgG2a/c CD20 mAbs resulted from FcγRIV interactions, with potential contributions from high-affinity FcγRI. Regardless, FcγRIV could mediate IgG2a/b/c CD20 mAb–induced depletion in the absence of FcγRI and FcγRIII. In contrast, inhibitory FcγRIIB deficiency significantly increased CD20 mAb–induced B cell depletion by enhancing monocyte function. Although FcγR-dependent pathways regulated B cell depletion from lymphoid tissues, both FcγR-dependent and -independent pathways contributed to mature bone marrow and circulating B cell clearance by CD20 mAbs. Thus, isotype-specific mAb interactions with distinct FcγRs contribute significantly to the effectiveness of CD20 mAbs in vivo, which may have important clinical implications for CD20 and other mAb-based therapies.

Fc receptors for IgG (FcγR) link innate and adaptive immunity by their ability to mediate effector cell interactions with antigen–antibody (Ab) complexes and Ab-coated target cells (1, 2). Mouse effector cells express four different FcγR classes: FcγRI (CD64), FcγRIIB (CD32), FcγRIII (CD16), and the recently described FcγRIV (also termed FcRL3 and CD16-2; references 3–5). FcγRIV is expressed by myeloid cells and shares 63% amino acid sequence identity with FcγRIII (CD16) in humans (3–5). FcγRI, FcγRIII, and FcγRIV are hetero-oligomeric receptors in which the respective ligand-binding α chains generate stimulatory signals through ITAM sequences found within a shared common γ chain subunit (Fc receptor common γ chain [FcRγ]) that is required for FcγR assembly. FcRγ chain ITAM sequences are essential to initiate or augment effector cell responses such as Ab-dependent cellular cytotoxicity (ADCC) and phagocytosis (1, 2). High-affinity FcγRI preferentially binds monomeric IgG2a, whereas FcγRIII binds with low affinity to IgG2a/IgG1/IgG2b, and FcγRIV binds with intermediate affinity to IgG2a and IgG2b in vitro (1). In contrast to stimulatory FcγRs, FcγRIIB contains ITIM sequences that inhibit effector cell responses. Coexpression of both activation and inhibitory FcγRs on macrophages, neutrophils, and mast cells appropriately balances protective and pathogenic innate effector responses after IgG immune complex engagement (6). Imbalances between stimulatory and inhibitory FcγR functions can also contribute to autoimmunity in humans and mice (7).

Chimeric or radiolabeled mAb therapies directed against CD20 expressed by mature B lymphocytes represent an effective treatment for non-Hodgkin's lymphoma (8–12) and may treat rheumatoid arthritis, idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura, hemolytic anemia, and other immune-mediated diseases (13, 14). Mouse anti–mouse CD20 mAbs (15) have provided a preclinical model for CD20 mAb immunotherapy amenable to mechanistic studies and genetic manipulation. In this model, CD20 mAbs engage the innate mononuclear phagocytic network and deplete blood and tissue B cells through FcγR-dependent and complement-independent mechanisms (16, 17). These anti–mouse CD20 mAbs thereby provide effective tools for understanding how innate effector mechanisms function in vivo. B cell depletion is CD20 mAb isotype specific, with IgG2a/c mAbs exhibiting the greatest potency (16). An IgG2c CD20 mAb effectively depletes B cells in both FcγRI−/− and FcγRIII−/− mice, but is not effective in FcRγ−/− mice (16). The recently identified functional characteristics of FcγRIV may explain the FcγR dependence but FcγRI and FcγRIII independence of this IgG2c CD20 mAb in vivo. These Ab isotype–specific effects are clinically important because the antitumor effect of CD20 mAbs in humans depends in part on FcγR-dependent immune activation (18), and a chimeric CD20 mAb of an isotype different than that used clinically does not deplete normal B cells in nonhuman primates (19). Moreover, human FcγRIIa and FcγRIIIa polymorphisms correlate with the efficiency of B cell and tumor depletion during CD20 mAb therapy in lupus and lymphoma patients (20–22). Thus, a molecular understanding of the different roles of each FcγR during B cell depletion is essential for mechanism-based predictions of biological outcomes for mAb-based immunotherapies.

To identify molecular mechanisms of innate effector cell function in vivo, B cell depletion was assessed in mice with FcγRI, FcγRIIB, FcγRIII, FcγRIV, or FcRγ blockade or deficiency using IgG1, IgG2a/c, and IgG2b isotype mAbs that bind mouse CD20. We show that IgG1 CD20 mAb–induced B cell depletion predominantly, if not exclusively, required FcγRIII expression, whereas IgG2a/c and IgG2b CD20 mAb–induced B cell depletion was primarily performed through FcγRIV with potential FcγRI interactions. In contrast, FcγRIIB expression inhibited CD20 mAb–induced B cell depletion in vivo. These findings provide new insight into the therapeutic as well as potentially pathogenic innate effector mechanisms that can mediate ADCC in vivo.

RESULTS

Isotype-specific CD20 mAb depletion of B cells in vivo

Six CD20 mAbs representative of each IgG isotype effective for B cell depletion, IgG1 (MB20-1 and MB20-14), IgG2a (MB20-16), IgG2c (MB20-11), and IgG2b (MB20-7 and MB20-18), were assessed for their ability to deplete blood and tissue B cells in vivo in a dose-dependent manner 7 d after mAb administration. Although the MB20-18 mAb reacted with B cells at the highest density among CD20 mAbs, each individual CD20 mAb reacted similarly with blood, spleen, and lymph node B220+ cells from wild-type, FcRγ−/−, FcγRI−/−, FcγRIIB−/−, and FcγRIII−/− mice (Fig. 1 and not depicted).

Figure 1.

IgG1, IgG2c, and IgG2b CD20 mAb reactivity with B cells in wild-type, FcRγ−/−, FcγRI−/−, FcγRIIB−/−, and FcγRIII−/− mice. CD20 mAb reactivity with enriched spleen B cells as assessed by indirect immunofluorescence staining with flow cytometry analysis. Fluorescence intensities of CD20+ cells stained with CD20 (solid line) or isotype-matched control (dashed line) mAbs shown on a four-decade log scale.

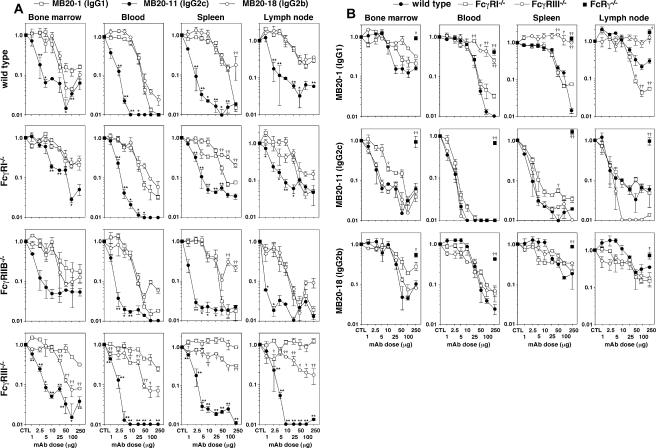

When mAb depletion of tissue B cells in wild-type mice was assessed over a range of mAb concentrations (1–250 μg/mouse), a hierarchy of depletion efficiencies for bone marrow, blood, spleen, and lymph node B cells was observed with MB20-11 (IgG2c) displaying the greatest activity (Fig. 2 A and Table I). Similar, if not identical, results were obtained using the IgG2a (MB20-16) mAb (not depicted), suggesting that IgG2a/c mAbs were similar in their abilities to bind FcγR. The IgG1 (MB20-1 and MB20-14) and IgG2b (MB20-18) mAbs depleted B cells similarly when used at low mAb concentrations, although the IgG1 mAbs depleted significantly more spleen B cells than the MB20-18 mAb when used at 250-μg doses (Fig. 2 A, Table I, and not depicted) as described previously (16). Each of the mAbs (MB20-11, MB20-16, MB20-1, MB20-14, and MB20-18) was saturating at >25-μg doses, which represented the maximal levels of depletion possible, even with higher mAb doses over a 7-d treatment period (Fig. 2 A and Table I). The MB20-7 mAb did not deplete B cells efficiently at any dose (not depicted). The high reactivity of MB20-18 with B cells (Fig. 1) may explain why this mAb depleted 84–94% of wild-type spleen B cells when used at 250 μg/mouse (Table I), whereas the MB20-7 and two other IgG2b CD20 mAbs only depleted 3–36% of B cells (16). The IgG1, IgG2a/c, and IgG2b CD20 mAbs significantly depleted mature bone marrow and circulating B cells, with T1, T2, and mature B cells depleted from the spleen and lymph nodes, whereas peritoneal B cells were only significantly depleted using IgG2a/c CD20 mAbs in wild-type mice (Table I and not depicted). Isotype-matched control mAbs had no measurable effects on B cell numbers (not depicted). Two different IgG3 CD20 mAbs (MB20-3 and MB20-13) failed to deplete significant numbers of tissue B cells when used at any concentration, as described previously (16). As in wild-type mice, the IgG2c (MB20-11) mAb was the most effective for B cell depletion in FcγRI−/−, FcγRIIB−/−, or FcγRIII−/− mice (Fig. 2 A and Table I). Isotype-matched control mAbs did not affect B cell numbers in FcRγ−/−, FcγRI−/− FcγRIIB−/−, or FcγRIII−/− mice (not depicted). Thus, IgG1, IgG2a/c, IgG2b, and IgG3 CD20 mAbs influenced B cell numbers through isotype- and FcγR-specific mechanisms.

Figure 2.

Isotype-specific CD20 mAb utilization of FcγRI, FcγRIIB, FcγRIII, and FcRγ during B cell depletion. (A) MB20-1 (IgG1), MB20-11 (IgG2c), or MB20-18 (IgG2b) CD20 mAb depletion of B cells in wild-type, FcγRI−/−, FcγRIIB−/−, and FcγRIII−/− mice. Bone marrow (mature IgM+B220hi), blood (B220+), spleen (mature CD24+CD21+B220+), and peripheral lymph node (B220+) B cell numbers were determined for 7 d after mAb treatment at the indicated doses. Values (±SEM) represent the percentage of B cells present in mAb-treated mice (two or more mice per value) relative to control mAb–treated littermates (250 μg; two or more mice per value). Significant differences between sample means of mice treated with MB20-1 and MB20-11 mAbs (*, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01) or MB20-1 and MB20-18 mAbs (†, P < 0.05; ††, P < 0.01) are indicated. (B) Comparison of B cell depletion for each mAb isotype in FcRγ−/−, FcγRI−/−, and FcγRIII−/− mice as shown in A. Significant differences between sample means of wild-type mice and each mutant strain are indicated: †, P < 0.05; ††, P < 0.01.

Table I.

Tissue B cell subset-specific depletion with CD20 mAbsa

| Tissue | B subseta | CD20 mAb Isotype | B cells (%) remaining relative to control mAb treatmentb

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wild-type | FcRγ−/− | FcγRI−/− | FcγRIII−/− | FcγRIIB−/− | |||

| Bone marrow | pro/pre | IgG1 | 140 | 149 | 172c | 67d | 84 |

| IgG2c | 130 | 99 | 119 | 122 | 96 | ||

| IgG2b | 141 | 61d | 127 | 107 | 74d | ||

| immature | IgG1 | 46 | 87 | 173c e | 87 | 83 | |

| IgG2c | 75 | 87 | 120e | 114 | 31 | ||

| IgG2b | 69 | 53 | 163c | 75 | 76 | ||

| mature | IgG1 | 17f | 82e | 23f | 40f | 19f | |

| IgG2c | 5f | 82e | 4f | 3f | 6f | ||

| IgG2b | 8f | 54c e | 28f d | 9f | 10f | ||

| Blood | B220+ | IgG1 | 2f | 41f e | 4f | 34f e | 2f |

| IgG2c | <1f | 70c e | 1f | 1f | <1f | ||

| IgG2b | 4f | 43c e | 8f | 7f | 6f | ||

| Spleen | mature | IgG1 | 1f | 140f e | 7f | 109e | 2f |

| IgG2c | 2f | 182f e | 3f | 2f | 2f | ||

| IgG2b | 16 f | 75e | 25f e | 33f | 19f | ||

| T1 | IgG1 | 28f | 88d | 7f | 34c | 11f d | |

| IgG2c | 5f | 42f e | 6f | 4f | 2f | ||

| IgG2b | 14f | 55e | 13f | 14f | 13f | ||

| T2 | IgG1 | <1f | 79e | 5f | 100e | 3f | |

| IgG2c | 1f | 99e | 2f | 1f | 6f d | ||

| IgG2b | 6f | 48f e | 9f | 13f e | 4f | ||

| Peripheral LN | B220+ | IgG1 | 27f | 163e | 6f | 104e | 3f |

| IgG2c | 6f | 97e | 6f | 1f | 2f | ||

| IgG2b | 35f | 72d | 15f | 19f | 6f d | ||

| Peritoneum | B220+ | IgG1 | 115 | 156 | 109 | 85 | 76 |

| IgG2c | 52c | 107d | 52f | 71c | 73 | ||

| IgG2b | 113 | 75 | 60 | 60 | 83 | ||

| B-1a | IgG1 | 147 | 125 | 79 | 54 | 63d | |

| IgG2c | 68 | 127 | 73 | 68 | 78 | ||

| IgG2b | 131 | 78 | 67 | 65 | 53d | ||

| B-1b | IgG1 | 106 | 89 | 123 | 97 | 72 | |

| IgG2c | 66 | 135 | 68 | 69 | 75 | ||

| IgG2b | 107 | 65 | 40 | 93 | 81 | ||

| B2 | IgG1 | 60 | 179 | 89 | 89 | 34f | |

| IgG2c | 33c | 93d | 60c | 77 | 43f | ||

| IgG2b | 50 | 74 | 76 | 94 | 50 | ||

B cell subsets were: bone marrow pro–/pre–B (IgM−B220lo), immature B (IgM+B220lo), and mature B (IgM+B220hi); spleen mature (CD24+CD21+B220+), T1 (CD24hiCD21−B220+), and T2 (CD24hiCD21+B220+); and peritoneal B-1a (CD5+CD11b+IgMhiB220lo), B-1b (CD5−CD11b+IgMhiB220lo), and B2 (CD5−IgMloB220hi). LN, lymph node.

Pooled values indicate the percentages of B cells in CD20 mAb–treated mice (50–250 μg; IgG1 MB20-1, IgG2c MB20-11, and IgG2b MB20-18) relative to control mAb–treated littermates (50–250 μg; n ≥ 4 per value). Significant differences between mean B cell numbers in CD20 mAb–treated mice compared with control mAb–treated littermates are indicated:

P < 0.05 and

p < 0.01.

Significant differences between mean percentages of B cells in each mutant mouse strain after CD20 mAb treatment relative to percentages obtained in wild type mice are indicated:

P < 0.05 and

P < 0.01.

Roles for activating FcγRs in B cell depletion

The roles of individual FcγRs in B cell depletion by CD20 mAbs were assessed by directly comparing B cell depletion in mice deficient in FcRγ, FcγRI, or FcγRIII. IgG1, IgG2a/c, and IgG2b CD20 mAbs each required FcRγ expression for the majority of bone marrow, blood, and tissue B cell depletion (Fig. 2 B, Table I, and not depicted), as described previously (16). Uniquely, FcγRIII expression was required for MB20-1 (IgG1) mAb treatment but had no effect on IgG2a/c or IgG2b CD20 mAb–induced B cell depletion. Two independent FcγRIII−/− mouse lines (23, 24) generated identical results (not depicted). In contrast, FcγRI deficiency had much less dramatic effects on CD20 mAb–induced B cell depletion. Thus, IgG1 CD20 mAbs preferentially, if not exclusively, used FcγRIII for B cell depletion in vivo.

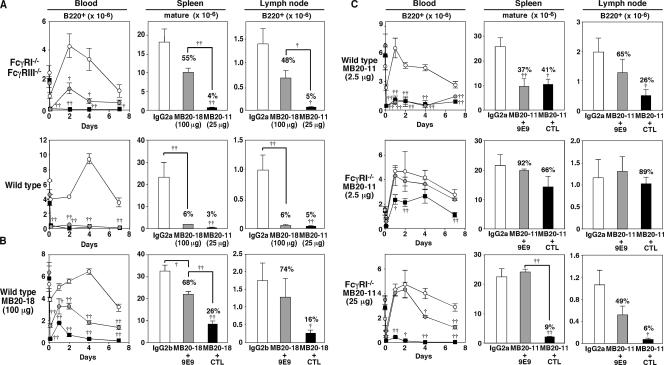

The role of the newly identified FcγRIV molecule in B cell depletion by IgG2b (100 μg MB20-18) and IgG2c (25 μg MB20-11) CD20 mAbs was assessed using FcγRI−/−/FcγRIII−/− mice, where only FcγRIV is expressed. At these doses, both the IgG2b and IgG2c CD20 mAbs depleted significant numbers of blood and spleen B cells in both FcγRI−/−/FcγRIII−/− and wild-type mice (Fig. 3 A). Combined FcγRI/FcγRIII deficiencies inhibited IgG2b CD20 mAb–induced B cell depletion when compared with wild-type mice, suggesting that FcγRI and/or FcγRIII may contribute to IgG2b/c CD20 mAb depletion in addition to FcγRIV. Regardless, FcγRIV mediated effective IgG2b and IgG2c CD20 mAb–induced B cell depletion in the absence of both FcγRI and FcγRIII expression. The role of FcγRIV in B cell depletion by IgG2b CD20 mAbs was further verified in wild-type mice using the recently described FcγRIV function-blocking mAb, 9E9 (5). The MB20-18 (IgG2b) mAb at 100 μg depleted between 50 and 90% of blood and tissue B cells, but this was significantly attenuated or eliminated when FcγRIV function was blocked using the 9E9 mAb (Fig. 3 B). These results suggest that FcγRIV preferentially mediates IgG2b CD20 mAb–induced B cell depletion.

Figure 3.

FcγRIV mediates B cell depletion by IgG2b (MB20-18) and IgG2c (MB20-11) CD20 mAbs. (A) Blood, spleen, and lymph node B cell depletion in FcγRI−/−/FcγRIII−/− and wild-type mice treated with MB20-18 (100 μg; gray circles/bars), MB20-11 (25 μg; filled circles/bars), or control IgG2a (100 μg; open circles/bars) mAbs. Values (±SEM) indicate mean circulating B cell numbers (per ml) before (time 0) and 1 h or 1, 2, 4, or 7 d after mAb treatment (three or more mice per value). Mean (±SEM) spleen or lymph node B cell numbers were determined 7 d after mAb treatment (three or more mice per group). (B) B cell depletion in wild-type mice treated with IgG2b control mAb (100 μg; open circles/bars) or MB20-18 mAb (100 μg; filled circles/bars) in combination with FcγRIV-blocking 9E9 (200 μg; gray circles/bars) or control (CTL; 200 μg; filled circles/bars) mAb on day 0 as indicated. (C) B cell depletion in mAb-treated wild-type or FcγRI−/− mice. Mice were treated with IgG2a control mAb (2.5 or 25 μg; open circles/bars) or MB20-11 mAb (2.5 or 25 μg; filled circles/bars) in combination with FcγRIV-blocking 9E9 mAb (200 μg; gray circles/bars) or control (CTL; 200 μg; filled circles/bars) mAb on day 0 as indicated. In A–C, significant differences between mean results for control and CD20 mAb–treated mice are indicated (†, P < 0.05; ††, P < 0.01), with numbers indicating the mean relative percentages of B220+ lymphocytes in MB20-11/MB20-18 mAb–treated mice compared with control mAb–treated littermates.

In wild-type mice, the IgG2c MB20-11 mAb at 2.5 μg/mouse depleted most circulating (>95%) B cells by day 7 and significantly reduced spleen and lymph node B cell numbers (Fig. 3 C). Blocking FcγRIV activity with the 9E9 mAb in wild-type mice treated with low-dose MB20-11 mAb inhibited lymph node B cell depletion but did not significantly reduce blood and spleen B cell depletion. However, blocking FcγRIV function in FcγRI−/− mice significantly affected the ability of IgG2c CD20 mAbs to deplete B cells in vivo. Specifically, 60% of circulating B cells were depleted in FcγRI−/− mice treated with low-dose MB20-11 mAb (2.5 μg), whereas B cell depletion was not observed when FcγRIV function was also blocked. Circulating, splenic, and lymph node B cells in FcγRI−/− mice were also significantly depleted by MB20-11 mAb at a 25-μg dose, but B cell depletion was significantly reduced when FcγRIV function was also blocked. Thus, FcγRIV contributed substantially to IgG2c CD20 mAb– induced B cell depletion, but FcγRI expression may also facilitate B cell depletion by the MB20-11 mAb, particularly when CD20 mAb doses are limiting.

Role for FcγRIIB in B cell depletion

As an inhibitory receptor expressed by monocytes and B cells, FcγRIIB deficiency could affect B cell depletion. Therefore, FcγRIIB−/− mice were treated with IgG1, IgG2a/c, and IgG2b CD20 mAbs over a range of concentrations. Splenic and lymph node B cell depletion by IgG1 CD20 mAb treatment was significantly augmented in FcγRIIB−/− mice when used at 50–100-μg doses (Fig. 4 and not depicted). Lymph node B cell depletion by IgG2a/c and IgG2b CD20 mAbs was also significantly enhanced by FcγRIIB deficiency (Fig. 4 and not depicted). The MB20-1 (IgG1) and MB20-18 (IgG2b) mAbs depleted >90% of lymph node B cells when used at ≥25-μg doses in FcγRIIB−/− mice, whereas these mAbs maximally depleted 70–80% of B cells when used at higher concentrations in wild-type littermates. The MB20-11 IgG2c mAb depleted 90% of lymph node B cells at 10-fold lower mAb concentrations in FcγRIIB−/− mice. As a result, lymph node B cell depletion in FcγRIIB−/− mice was as efficient as spleen B cell depletion in CD20 mAb–treated wild-type mice. FcγRIIB deficiency did not significantly enhance the degree of bone marrow or blood B cell clearance. Within the peritoneal cavity, FcγRIIB deficiency did not enhance the degree of peritoneal B-1a and B-1b cell clearance after CD20 mAb treatments but did facilitate IgG1 CD20 mAb–induced depletion of conventional B2 cells (Table I). Thus, expression of this inhibitory receptor significantly reduced the effectiveness of B cell depletion by CD20 mAbs in vivo.

Figure 4.

FcγRIIB deficiency augments CD20 mAb–induced B cell depletion. Bone marrow (mature IgM+B220hi), blood (B220+), spleen (mature CD24+CD21+B220+), and lymph node (B220+) B cell numbers were determined for wild-type and FcγRIIB−/− mice 7 d after MB20-1, MB20-11, or MB20-18 mAb treatment at the indicated doses. Values (±SEM) represent the percentage of B cells present in mAb-treated mice (two or more mice per value) relative to control mAb–treated littermates (250 μg; two or more mice per value), with significant differences between sample means of wild-type mice and each mutant strain indicated: †, P < 0.05; ††, P < 0.01.

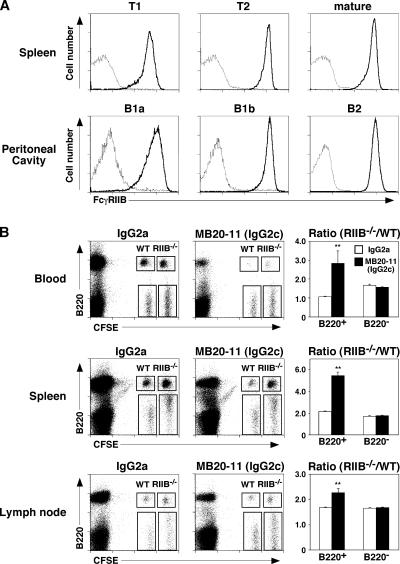

Role for B cell FcγRIIB in B cell depletion

Spleen T1, T2, and mature B cells and peritoneal cavity B-1a, B-1b, and B2 cells uniformly expressed FcγRIIB, although there was variability in FcγRIIB expression densities between individual spleen and peritoneal cavity B cell subsets (Fig. 5 A). It was therefore assessed whether augmented B cell depletion in FcγRIIB−/− mice resulted from a change in B cell or monocyte FcγRIIB expression. FcγRIIB−/− splenocytes and control splenocytes from wild-type mice were differentially labeled with CFSE, mixed together in equal proportions, and adoptively transferred into recipient mice 1 d before CD20 mAb treatment. 1 d after CD20 mAb treatment, the relative frequencies of CFSE-labeled B220+ and B220− lymphocytes in the blood, spleen, and lymph nodes were quantified by flow cytometry (Fig. 5 B). The relative frequency of wild-type B220+ lymphocytes in the blood, spleen, and lymph nodes was more significantly reduced in MB20-11 CD20 mAb–treated mice when compared with the frequency of FcγRIIB−/− B220+ lymphocytes. Control mAb treatment did not affect the relative ratios of B220+ FcγRIIB−/− and B220+ wild-type lymphocytes in these adoptive transfer experiments. Likewise, CD20 mAb treatment did not affect the relative ratios of B220− FcγRIIB−/− and B220− wild-type lymphocytes. Thus, FcγRIIB deficiency reduced the relative rate of B cell depletion compared with wild-type B cells, although FcγRIIB−/− B cells were effectively depleted after 7 d of CD20 mAb treatment (Table I).

Figure 5.

FcγRIIB−/− B cells resist CD20 mAb–induced depletion in wild-type mice. (A) Flow cytometry analysis of FcγRIIB expression (thick lines) by B cell subsets from FcRγ−/− mice. Spleen B cell subsets were identified as mature (CD24+CD21+B220+), T1 (CD24hiCD21−B220+), and T2 (CD24hiCD21+B220+). Peritoneal cavity B cell subsets were identified as B-1a (CD5+CD11b+IgMhiB220lo), B-1b (CD5−CD11b+IgMhiB220lo), and B2 (CD5−IgMloB220hi). Solid lines indicate 2.4G2 mAb staining, and dotted lines indicate isotype-matched control mAb reactivity. (B) Flow cytometry analysis of CFSE-labeled B220+ and B220− lymphocytes from wild-type and FcγRIIB−/− mice on day 1 indicating gates used to assess frequencies of adoptively transferred CFSE+ wild-type and FcγRIIB−/− cells. Splenocytes from wild-type (WT) and FcγRIIB−/− (RIIB−/−) mice were labeled with CFSE at different intensities, mixed, and transferred into wild-type littermates 1 d before treatment with MB20-11 or control mAb (25 μg). After 1 d, blood, spleen, and peripheral lymph node lymphocytes were isolated and assessed for B220 expression. Bar graphs indicate the relative ratios of cells from wild-type and FcγRIIB−/− donors within the CFSE-labeled B220+ and B220− lymphocyte populations. Results represent those obtained with three or more mouse pairs, with significant differences between sample means (±SEM) indicated: *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01.

Role for FcγRs in B cell subset depletion

Subtle effects of FcγR deficiencies on B cell subset depletion were also observed (Table I). For example, the number of pro–/pre–B cells present in bone marrow after IgG1 mAb treatment was significantly increased in FcγRI−/− mice. Similar effects on immature bone marrow B cells in FcγRI−/− mice were observed after IgG1 and IgG2b mAb treatments. MB20-11 mAb treatment also increased spleen B cell numbers in FcRγ−/− mice compared with control mAb–treated littermates, predominantly due to increased numbers of immature B cells (not depicted). Thus, alterations in FcγR expression significantly affected the dynamics of B cell subset depletion after CD20 mAb treatment.

DISCUSSION

The extent of B cell depletion induced by CD20 mAbs correlated closely with IgG isotype, with IgG2a/c mAbs being the most effective and IgG3 mAbs having modest effects in vivo (Fig. 1 and Table I; reference 16). Although our previous studies suggested reciprocal roles for FcγRI or FcγRIII in CD20 mAb–induced depletion of B cells (16), the current studies demonstrate that differential FcγR utilization explains differences in effectiveness between CD20 mAb isotypes. IgG1 CD20 mAb–induced B cell depletion was predominantly, if not exclusively, performed through low-affinity FcγRIII (Fig. 2 and Table I). Preferential IgG1 interactions with FcγRIII for phagocytosis of IgG1-coated erythrocytes or immune complexes, and in animal models of experimental autoimmune hemolytic anemia and passive cutaneous anaphylaxis, have been demonstrated previously (25, 26). In contrast, IgG2b and IgG2a/c CD20 mAb–induced B cell depletion was primarily performed through intermediate affinity FcγRIV, although high-affinity FcγRI interactions may also contribute to this process (Figs. 2 and 3). Importantly, FcγRIV mediated effective B cell deletion by both IgG2a/c and IgG2b CD20 mAbs in the absence of both FcγRI and FcγRIII (Fig. 3 A). Because simultaneous blockade of FcγRIV function and FcγRI expression prevented B cell depletion by IgG2b and IgG2a/c CD20 mAbs, FcγRIII may have minimal interactions with these mAb isotypes. Although mouse IgG3 is reported to bind FcγRI (27), IgG3 CD20 mAbs had little effect in vivo (16). Thus, monocyte expression of either FcγRIV or FcγRIII is sufficient for B cell depletion when mAbs of the correct isotypes are considered. These findings explain why IgG2a/c CD20 mAb therapy was effective in both FcγRI−/− and FcγRIII−/− mice, but not in FcRγ−/− mice (Fig. 2 B and Table I; reference 16). Thereby, each IgG isotype demonstrated preferential specificity for different stimulatory FcγRs.

The importance of mAb isotype in immunotherapy has long been appreciated, particularly for mouse IgG2a mAbs (28–32). Like IgG2a/c CD20 mAbs for B cell depletion (Fig. 2 A and not depicted), IgG2a anti-erythrocyte mAbs induce more severe FcγR-dependent hemolytic anemia than IgG2b mAbs (33). However, because FcγRIV binds IgG2a and IgG2b mAbs with similar affinities in vitro (5), it was surprising that IgG2a/c CD20 mAbs depleted B cells at least 10-fold better than the IgG2b MB20-18 CD20 mAb in vivo (Fig. 1; reference 16). Moreover, the MB20-18 mAb primarily used in the current studies is the most potent of four IgG2b CD20 mAbs assessed for B cell depletion (16). It is therefore possible that engagement of both FcγRIV and FcγRI by IgG2a/c CD20 mAbs explains their higher potency in vivo (Fig. 3 A). High-affinity FcγRI may participate in some IgG2a-mediated effects in certain experimental model systems, although FcγRI may play a minor role in vivo because administered mAbs must compete with intrinsic circulating Abs for high-affinity FcγRI interactions (34). Determining the precise contribution of FcγRI to IgG2a/b/c CD20 mAb effectiveness in vivo will require the generation and characterization of FcγRIV-deficient mice. Alternatively, mAb isotype–specific structural features may explain the potency of IgG2a isotype CD20 mAbs in vivo. For example, IgG2a/c and IgG2b CD20 mAbs may bind cell surface CD20 differently or have different effects on target antigen/Ab densities during CD20 mAb–induced ADCC, or allow the efficient clustering of CD20 on the surface of B cells. IgG2a/c isotype switching may also select for CD20 mAbs with high intrinsic potencies, high mAb affinities, or unique fine specificities for CD20. Regardless, the greater activity of IgG2a/c CD20 mAbs in vivo was not explained by unique effects on ADCC through FcγRIIB negative regulation (Fig. 4).

CD20 mAb–induced B cell depletion was reduced by monocyte expression of FcγRIIB in vivo, with FcγRIIB deficiency also revealing tissue-specific effects on B cells (Fig. 4 and Table I). FcγRIIB deficiency significantly enhanced lymph node B cell depletion by IgG1, IgG2c, and IgG2b CD20 mAbs, whereas FcγRIIB deficiency only enhanced IgG1 CD20 mAb–induced spleen B cell depletion when used at higher mAb doses. Lymph node B cell depletion was less efficient than spleen B cell depletion at equivalent CD20 mAb doses, but lymph node and spleen B cell depletion were similar in the absence of FcγRIIB expression. Likewise, FcγRIIB deficiency did not significantly enhance B-1a or B-1b cell depletion from the peritoneal cavity (Table I), populations of B cells that are more resistant to CD20 mAb–induced depletion than peritoneal B2 cells (17). Therefore, circumventing the negative regulatory role of FcγRIIB may be most advantageous during suboptimal mAb dosing or for B cell depletion within lymph nodes. Consistent with this, FcγRIIB deletion enhances the cytotoxicity of human Fc region–chimerized or -humanized mAbs targeting tumors in vivo, including rituximab targeting of human lymphoma cells in nude mice (18). Surprisingly, however, FcγRIIB−/− B cells were also more resistant to CD20 mAb–induced depletion than wild-type B cells (Fig. 5). FcγRIIB−/− B cell resistance to CD20 mAb treatment did not result from reduced CD20 expression (Fig. 1), and peritoneal B-1a or B-1b cell resistance to CD20 mAb–induced depletion did not result from low FcγRIIB expression (Fig. 5 A). Nonetheless, no significant relationship has been found between FcγRIIB protein expression on diffuse large B cell lymphomas and the prognosis of patients or their outcome after rituximab therapy (35). Thus, circumventing monocyte inhibitory FcγRII function in vivo could result in more effective immunotherapies, but this may be influenced by tissue-specific factors including the localization of target B cells or ADCC effector cells.

Although tissue B cell clearance was FcRγ dependent, circulating B cell clearance was mediated through both FcRγ-dependent and -independent pathways. In the absence of FcRγ expression, 30–57% of circulating B cells were cleared by IgG1, IgG2a/c, and IgG2b CD20 mAbs on day 7 (Fig. 1, Table I, and not depicted). Similar results were obtained for mature bone marrow B cells, which include the recirculating B cell pool. Most IgG2b and IgG3 anti–mouse CD20 mAbs also deplete blood B cells but have modest, if any, effects on spleen B cells (16). This demonstrates that blood and circulating bone marrow B cells share common properties that allow their clearance without operable ADCC. Rapid blood B cell depletion is also observed in patients after CD20 mAb infusions (36–39). However, the current results suggest that blood B cell clearance may not necessarily correlate with tissue B cell clearance. Consistent with this, human FcγRIIIa polymorphisms are not predictive of patient responses in chronic lymphocytic leukemia, which most commonly involves blood and marrow (40). Thus, although FcγR-mediated ADCC remains a primary mechanism for B cell depletion in vivo, FcγR-independent pathways also influence the clearance of circulating B cells.

Collectively, these results indicate that the most important factors influencing CD20 mAb efficacy in vivo are mAb isotype and capacity to interact with FcγRs. These results also further support previous findings whereby Ab isotypes exhibit functional hierarchies in their relative abilities to engage different FcγRs in vivo. The current immunotherapy studies also correlate with models of adaptive immunity where IgG2a Abs are most efficient in providing optimal or substantial protection during bacterial, viral, and fungal infections (41–45). Thus, the intricate innate effector pathways used for B cell depletion in the current studies may have been selected evolutionarily for potency. The current observations also corroborate studies in lupus and lymphoma patients showing that human FcγRIIa and FcγRIIIa polymorphisms correlate with the efficiency of tumor and B cell depletion using a chimeric human IgG1 CD20 mAb (20–22). That mouse FcγRIV is most structurally similar to human FcγRIII (3–5) further implicates the importance of this receptor in human B cell depletion after CD20 mAb treatment. Understanding whether human Ab isotypes exhibit a functional hierarchy in their relative abilities to engage different FcγRs in vivo will be critical for better manipulating FcγR function during immunotherapy or ameliorating the consequences of pathogenic autoantibodies. The current studies also indicate that it may be important to consider disease- and tissue-specific targeting effects when manipulating FcγR expression or function for therapeutic benefit. Because therapeutic andpathogenic Abs are likely to share many common pathways and FcγR-dependent processes, a further understanding of the molecular complexities of FcγR function and signaling in vivo are essential to fully harness the potent stimulatory and inhibitory functions of this receptor system in treating human disease.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Abs and immunofluorescence analysis.

Mouse CD20–specific mouse mAbs were as described previously (15). Hamster anti–mouse FcγRIV mAb, 9E9, was as described previously (5, 46). Other mAbs included: B220 mAb RA3-6B2 (provided by R. Coffman, DNAX Corp., Palo Alto, CA); Thy1.2 mAb (Caltag); and CD1d (1B1), CD5 (53-7.3), CD11b (M1/70), CD16/32 (2.4G2), CD21 (7G6), and CD24 (M1/69) mAbs (BD Biosciences). Isotype-specific and anti-Ig or anti-IgM Abs were from SouthernBiotech.

Single-cell suspensions of bone marrow (bilateral femurs), spleen, and peripheral lymph node (paired axillary and inguinal) lymphocytes were generated by gentle dissection. To isolate peritoneal cavity leukocytes, 10 ml of cold (4°C) PBS was injected into the peritoneum of killed mice followed by gentle massage of the abdomen. Viable cells were counted using a hemocytometer, with relative lymphocyte percentages determined by flow cytometry analysis. Blood erythrocytes were lysed after immunofluorescence staining using FACS Lysing Solution (BD Biosciences). Single-cell leukocyte suspensions were stained on ice using predetermined optimal concentrations of each Ab for 20–60 min and fixed as described previously (47, 48). Cells with the light scatter properties of lymphocytes were analyzed by two- to four-color immunofluorescence staining with FACScan or FACSCalibur flow cytometer analysis (Becton Dickinson). Background staining was determined using unreactive control mAbs (Caltag) with gates positioned to exclude ≥98% of the cells.

In some cases, B cell–enriched single-cell lymphocyte preparations were generated by incubating 2 × 108 splenocytes with 180 μl anti-Thy1.2 mAb–coated magnetic beads (Dynal) in 10 ml RPMI 1640 medium containing 5% FBS for 30 min at 4°C, followed by T cell removal using a magnet. B cell preparations were ≥93% B220+ as determined by immunofluorescence staining with flow cytometry analysis. The B cell preparations were assessed for cell surface CD20 expression as described above, except 106 lymphocytes were incubated with each CD20 mAb at 10 μg/ml, washed, and incubated with PE-conjugated goat anti–mouse IgG1, IgG2a, or IgG2b isotype–specific secondary Ab for immunofluorescence staining.

Mice.

FcγRI−/− and FcγRIII−/− mice were as described previously (23) and crossed to generate FcγRI−/−/FcγRIII−/− mice. C57BL/6, FcγRIIB−/− (B6,129S-Fcgr2tm1Rav), and FcγRIII−/− (C57BL/6-Fcgr3tm1Sjv) mice were from The Jackson Laboratory. FcRγ-deficient mice (FcRγ−/−, B6.129P2-Fcer1gtm1) were from Taconic Farms. All mice were housed in a specific pathogen-free barrier facility and first used at 2–3 mo of age. All studies were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of Duke University.

Immunotherapy.

Sterile anti–mouse CD20 and isotype control mAbs (1–250 μg) in 200 μl PBS were injected through lateral tail veins. Blood leukocyte numbers were quantified by hemocytometer after red cell lysis, with blood and tissue B220+ B cell frequencies determined by immunofluorescence staining with flow cytometry analysis as described previously (16, 17). Because equivalent results were obtained in mice treated with control IgG2a, IgG2b, or IgG1 mAbs, the results were pooled in some instances.

Adoptive transfer experiments.

Unfractionated splenocytes from FcγRIIB−/− and wild-type mice were labeled with 4 and 0.4 μM Vybrant CFSE, respectively (Invitrogen), according to the manufacturer's instructions. The relative frequency of B220+ cells among CFSE-labeled splenocytes was determined by immunofluorescence staining with flow cytometry analysis. Subsequently, equal numbers of CFSE-labeled B220+ FcγRIIB−/− and wild-type splenocytes (4 × 107) were injected i.v. into wild-type mice 1 d before i.v. injection of either MB20-11 or control mAbs. After 1 d, cells were harvested from each tissue and CFSE-labeled B220+ cells were analyzed by immunofluorescence staining with flow cytometry analysis.

Statistical analysis.

All data are shown as means ± SEM. The Student's t test was used to determine the significance of differences between population means.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Jeffrey V. Ravetch for reagents, mice, and helpful suggestions.

This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (CA105001, CA96547, and AI56363) and The Arthritis Foundation. T.F. Tedder is a paid consultant for MedImmune, Inc.

The authors have no other financial conflict of interest.

Abbreviations used: Ab, antibody; ADCC, Ab-dependent cellular cytotoxicity; FcγR, Fc receptor for IgG; FcRγ, Fc receptor common γ chain.

References

- 1.Takai, T. 2002. Roles of Fc receptors in autoimmunity. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2:580–592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ravetch, J.V. 2003. Fc receptors. In Fundamental Immunology. W.E. Paul, editor. Lippincott-Raven, Philadelphia, PA. 685–700.

- 3.Davis, R.S., G. Dennis Jr., M.R. Odom, A.W. Gibson, R.P. Kimberly, P.D. Burrows, and M.D. Cooper. 2002. Fc receptor homologs: newest members of a remarkably diverse Fc receptor gene family. Immunol. Rev. 190:123–136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mechetina, L.V., A.M. Najakshin, B.Y. Alabyev, N.A. Chikaev, and A.V. Taranin. 2002. Identification of CD16-2, a novel mouse receptor homologous to CD16/FcγRIII. Immunogenetics. 54:463–468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nimmerjahn, F., P. Bruhns, K. Horiuchi, and J.V. Ravetch. 2005. FcγRIV: a novel FcR with distinct IgG subclass specificity. Immunity. 23:41–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Clynes, R., J.S. Maizes, R. Guinamard, M. Ono, T. Takai, and J.V. Ravetch. 1999. Modulation of immune complex–induced inflammation in vivo by the coordinate expression of activation and inhibitory Fc receptors. J. Exp. Med. 189:179–185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kimberly, R.P., J. Wu, A.W. Gibson, K. Su, H. Qun, X. Li, and J.C. Edberg. 2002. Diversity and duplicity: human Fcγ receptors in host defense and autoimmunity. Immunol. Res. 26:177–189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Press, O.W., J.P. Leonard, B. Coiffier, R. Levy, and J. Timmerman. 2001. Immunotherapy of non-Hodgkin's lymphomas. Hematology (Am. Soc. Hematol. Educ. Program). 1:221–240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kaminski, M.S., K.R. Zasadny, I.R. Francis, A.W. Milik, C.W. Ross, S.D. Moon, S.M. Crawford, J.M. Burgess, N.A. Petry, G.M. Butchko, et al. 1993. Radioimmunotherapy of B-cell lymphoma with [131I]anti-B1 (anti-CD20) antibody. N. Engl. J. Med. 329:459–465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Weiner, L.M. 1999. Monoclonal antibody therapy of cancer. Semin. Oncol. 26:43–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Onrust, S.V., H.M. Lamb, and J.A. Balfour. 1999. Rituximab. Drugs. 58:79–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McLaughlin, P., C.A. White, A.J. Grillo-Lopez, and D.G. Maloney. 1998. Clinical status and optimal use of rituximab for B-cell lymphomas. Oncology. 12:1763–1769. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Silverman, G.J., and S. Weisman. 2003. Rituximab therapy and autoimmune disorders: prospects for anti-B cell therapy. Arthritis Rheum. 48:1484–1492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Edwards, J.C., and G. Cambridge. 2001. Sustained improvement in rheumatoid arthritis following a protocol designed to deplete B lymphocytes. Rheumatology. 40:205–211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Uchida, J., Y. Lee, M. Hasegawa, Y. Liang, A. Bradney, J.A. Oliver, K. Bowen, D.A. Steeber, K.M. Haas, J.C. Poe, and T.F. Tedder. 2004. Mouse CD20 expression and function. Int. Immunol. 16:119–129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Uchida, J., Y. Hamaguchi, J.A. Oliver, J.V. Ravetch, J.C. Poe, K.M. Haas, and T.F. Tedder. 2004. The innate mononuclear phagocyte network depletes B lymphocytes through Fc receptor–dependent mechanisms during anti-CD20 antibody immunotherapy. J. Exp. Med. 199:1659–1669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hamaguchi, Y., J. Uchida, D.W. Cain, G.M. Venturi, J.C. Poe, K.M. Haas, and T.F. Tedder. 2005. The peritoneal cavity provides a protective niche for B1 and conventional B lymphocytes during anti-CD20 immunotherapy in mice. J. Immunol. 174:4389–4399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Clynes, R.A., T.L. Towers, L.G. Presta, and J.V. Ravetch. 2000. Inhibitory Fc receptors modulate in vivo cytotoxicity against tumor targets. Nat. Med. 6:443–446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Anderson, D.R., A. Grillo-López, C. Varns, K.S. Chambers, and N. Hanna. 1997. Targeted anti-cancer therapy using rituximab, a chimeric anti-CD20 antibody (IDEC-C2B8) in the treatment of non-Hodgkin's B-cell lymphoma. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 25:705–708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cartron, G., L. Dacheux, G. Salles, P. Solal-Celigny, P. Bardos, P. Colombat, and H. Watier. 2002. Therapeutic activity of humanized anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody and polymorphism in IgG Fc receptor FcγRIIIa gene. Blood. 99:754–758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Anolik, J.H., D. Campbell, R.E. Felgar, F. Young, I. Sanz, J. Rosenblatt, and R.J. Looney. 2003. The relationship of FcγRIIIa genotype to degree of B cell depletion by rituximab in the treatment of systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 48:455–459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Weng, W.-K., and R. Levy. 2003. Two immunoglobulin G fragment C receptor polymorphisms independently predict response to rituximab in patients with follicular lymphoma. J. Clin. Oncol. 21:3940–3947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bruhns, P., A. Samuelsson, J.W. Pollard, and J. Ravetch. 2003. Colony-stimulating factor-1-dependent macrophages are responsible for IVIG protection in antibody-induced autoimmune disease. Immunity. 18:573–581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hazenbos, W.L.W., J.E. Gessner, F.M.A. Hofhuis, H. Kuipers, D. Meyer, I.A.F.M. Heijnen, R.E. Schmidt, M. Sandor, P.J.A. Capel, M. Daëron, et al. 1996. Impaired IgG-dependent anaphylaxis and Arthus reaction in FcγRIII (CD16) deficient mice. Immunity. 5:181–188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hazenbos, W.L.W., I.A.F.M. Heijnen, D. Meyer, F.M.A. Hofhuis, C.R. de Lavalette, R.E. Schmidt, P.J.A. Capel, J.G.J. van de Winkel, J.E. Gessner, T.K. van den Berg, and J.S. Verbeek. 1998. Murine IgG1 complexes trigger immune effector functions predominantly via FcγRIII (CD16). J. Immunol. 161:3026–3032. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Meyer, D., C. Schiller, J. Westermann, S. Izui, W.L.W. Hazenbos, J.S. Verbeek, R.E. Schmidt, and J.E. Gessner. 1998. FcγRIII (CD16)-deficient mice show IgG isotype dependent protection to experimental autoimmune hemolytic anemia. Blood. 92:3997–4002. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gavin, A.L., N. Barnes, H.M. Dijstelbloem, and P.M. Hogarth. 1998. Cutting edge: identification of the mouse IgG3 receptor: implications for antibody effector function at the interface between innate and adaptive immunity. J. Immunol. 160:20–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Herlyn, D., and H. Koprowski. 1982. IgG2a monoclonal antibodies inhibit human tumor growth through interaction with effector cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 79:4761–4765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kaminski, M.S., K. Kitamura, D.G. Maloney, M.J. Campbell, and R. Levy. 1986. Importance of antibody isotype in monoclonal anti-idiotype therapy of a murine B cell lymphoma. A study of hybridoma class switch variants. J. Immunol. 136:1123–1130. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Denkers, E.Y., C.C. Badger, J.A. Ledbetter, and I.D. Bernstein. 1985. Influence of antibody isotype on passive serotherapy of lymphoma. J. Immunol. 135:2183–2186. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Liu, A.Y., R.R. Robinson, E.D. Murray Jr., J.A. Ledbetter, I. Hellströom, and K.E. Hellström. 1987. Production of a mouse-human chimeric monoclonal antibody to CD20 with potent Fc-dependent biologic activity. J. Immunol. 139:3521–3526. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Isaacs, J.D., J. Greenwood, and H. Waldmann. 1998. Therapy with monoclonal antibodies. II. The contribution of Fcγ receptor binding and the influence of CH1 and CH3 domains on in vivo effector function. J. Immunol. 161:3862–3869. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fossati-Jimack, L., A. Ioan-Facsinay, L. Reininger, Y. Chicheportiche, N. Watanabe, T. Saito, F.M.A. Hofhuis, J.E. Gessner, C. Schiller, R.E. Schmidt, et al. 2000. Markedly different pathogenicity of four immunoglobulin G isotype-switch variants of an antierythrocyte autoantibody is based on their capacity to interact in vivo with the low-affinity Fcγ receptor III. J. Exp. Med. 191:1293–1302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ioan-Facsinay, A., S.J. de Kimpe, S.M.M. Hellwig, P.L. van Lent, F.M.A. Hofhuis, H.H. van Ojik, C. Sedlik, S.A. da Silveira, J. Gerber, Y.F. de Jong, et al. 2002. FcγRI (CD64) contributes substantially to severity of arthritis, hypersensitivity responses, and protection from bacterial infection. Immunity. 16:391–402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Camilleri-Broet, S., N. Mounier, A. Delmer, J. Briere, O. Casasnovas, L. Cassard, P. Gaulard, B. Christian, B. Coiffier, and C. Sautes-Fridman. 2004. FcγRIIB expression in diffuse large B-cell lymphomas does not alter the response to CHOP+rituximab (R-CHOP). Leukemia. 18:2038–2040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Reff, M.E., K. Carner, K.S. Chambers, P.C. Chinn, J.E. Leonard, R. Raab, R.A. Newman, and N. Hanna. 1994. Depletion of B cells in vivo by a chimeric mouse human monoclonal antibody to CD20. Blood. 83:435–445. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Maloney, D.G., A.J. Grillo-Lopez, C.A. White, D. Bodkin, R.J. Schilder, J.A. Neidhart, N. Janakiraman, K.A. Foon, T.M. Liles, B.K. Dallaire, et al. 1997. IDEC-C2B8 (Rituximab) anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody therapy in patients with relapsed low-grade non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. Blood. 90:2188–2195. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Maloney, D.G., L.A. Grillo, D.J. Bodkin, C.A. White, T.M. Liles, I. Royston, C. Varns, J. Rosenberg, and R. Levy. 1997. IDEC-C2B8: results of a phase I multiple-dose trial in patients with relapsed non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. J. Clin. Oncol. 15:3266–3274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Winkler, U., M. Jensen, O. Manzke, H. Schulz, V. Diehl, and A. Engert. 1999. Cytokine-release syndrome in patients with B cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia and high lymphocyte counts after treatment with an anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody (Rituximab, IDEC- C2B8). Blood. 94:2217–2224. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Farag, S.S., I.W. Flinn, R. Modali, T.A. Lehman, D. Young, and J.C. Byrd. 2004. FcγRIIIa and FcγRIIa polymorphisms do not predict response to rituximab in B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood. 103:1472–1474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Coutelier, J.P., J.T. van der Logt, F.W. Heessen, G. Warnier, and J. Van Snick. 1987. IgG2a restriction of murine antibodies elicited by viral infections. J. Exp. Med. 165:64–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Markine-Goriaynoff, D., and J.P. Coutelier. 2002. Increased efficacy of the immunoglobulin G2a subclass in antibody-mediated protection against lactate dehydrogenase-elevating virus-induced polioencephalomyelitis revealed with switch mutants. J. Virol. 76:432–435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Baldridge, J.R., and M.J. Buchmeier. 1992. Mechanisms of antibody-mediated protection against lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus infection: mother-to-baby transfer of humoral protection. J. Virol. 66:4252–4257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Schlageter, A.M., and T.R. Kozel. 1990. Opsonization of Cryptococcus neoformans by a family of isotype-switch variant antibodies specific for the capsular polysaccharide. Infect. Immun. 58:1914–1918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Taborda, C.P., J. Rivera, O. Zaragoza, and A. Casadevall. 2003. More is not necessarily better: prozone-like effects in passive immunization with IgG. J. Immunol. 170:3621–3630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nimmerjahn, F., and J.V. Ravetch. 2005. Divergent immunoglobulin G subclass activity through selective Fc receptor binding. Science. 310:1510–1512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sato, S., N. Ono, D.A. Steeber, D.S. Pisetsky, and T.F. Tedder. 1996. CD19 regulates B lymphocyte signaling thresholds critical for the development of B-1 lineage cells and autoimmunity. J. Immunol. 157:4371–4378. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zhou, L.-J., H.M. Smith, T.J. Waldschmidt, R. Schwarting, J. Daley, and T.F. Tedder. 1994. Tissue-specific expression of the human CD19 gene in transgenic mice inhibits antigen-independent B lymphocyte development. Mol. Cell. Biol. 14:3884–3894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]