Abstract

The adenosine monophosphate (AMP)–activated protein kinase (AMPK) has a crucial role in maintaining cellular energy homeostasis. This study shows that human and mouse T lymphocytes express AMPKα1 and that this is rapidly activated in response to triggering of the T cell antigen receptor (TCR). TCR stimulation of AMPK was dependent on the adaptors LAT and SLP76 and could be mimicked by the elevation of intracellular Ca2+ with Ca2+ ionophores or thapsigargin. AMPK activation was also induced by energy stress and depletion of cellular adenosine triphosphate (ATP). However, TCR and Ca2+ stimulation of AMPK required the activity of Ca2+–calmodulin-dependent protein kinase kinases (CaMKKs), whereas AMPK activation induced by increased AMP/ATP ratios did not. These experiments reveal two distinct pathways for the regulation of AMPK in T lymphocytes. The role of AMPK is to promote ATP conservation and production. The rapid activation of AMPK in response to Ca2+ signaling in T lymphocytes thus reveals that TCR triggering is linked to an evolutionally conserved serine kinase that regulates energy metabolism. Moreover, AMPK does not just react to cellular energy depletion but also anticipates it.

During T lymphocyte activation, triggering of the TCR stimulates phospholipase C (PLC)–mediated hydrolysis of phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate to generate inositol-1,4, 5-trisphosphate (IP3) and polyunsaturated diacylglycerol (DAG). IP3 initiates the release of Ca2+ from intracellular stores in the ER, which is followed by a sustained increase in intracellular Ca2+ concentration ([Ca2+]i) mediated by Ca2+ entry via membrane Ca2+ channels. The sustained elevation of [Ca2+]i is critical during the initial phases of T cell activation, particularly for the production of effector cytokines (1, 2). One mediator of Ca2+ signals in T cells is the phosphatase calcineurin, which regulates NFAT transcription factors that control cytokine gene expression (2–6). Ca2+–calmodulin-dependent protein kinases such as CaM kinase II and IV also regulate cytokine genes but can have other functions (e.g., link Ca2+ signals to microtubule dynamics; references 2, 7–9).

CaM kinase IV, which is potently activated by TCR triggering, is activated by upstream Ca2+–calmodulin-dependent protein kinase kinases (CaMKKs; references 10, 11). In this respect, recent studies have suggested that CaMKKs also have the potential to activate the AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK), a protein kinase with a crucial role in maintaining cellular energy homeostasis (12–14). AMPK can be activated by an increased intracellular AMP/ATP ratio, which is a marker of falling cellular energy status, and acts to restore energy balance by inhibiting ATP-consuming processes and stimulating ATP-generating pathways (15). The stimulation of AMPK by an increase in the AMP/ATP ratio requires the phosphorylation of Thr-172 by the kinase LKB1 (16, 17). However, an alternate pathway of AMPK regulation mediated by Ca2+–CaMKK has recently been described in cells stimulated pharmacologically with Ca2+ ionophores and in rat cerebrocortical slices triggered by K+-induced depolarization (12–14). The physiological role of the Ca2+–CaMKK–AMPK pathway outside of neural tissues is not known, but this is an interesting issue for T cell biology because T cell activation is mediated by Ca2+-dependent signaling pathways, and triggering of the TCR induces a rapid increase in [Ca2+]i and CaMKK activation. Whether [Ca2+]i−CaMKK pathways regulate AMPK in T cells has not been examined, but it is an important question because of the key role for AMPK as a regulator of cellular energy balance. AMPK activation by the TCR would be a mechanism to stimulate the conservation and production of ATP in anticipation of the demand for ATP that is invariably initiated by Ca2+-mediated signaling pathways. In this context, a previous study has identified phosphatidylinositol-3,4,5-bisphosphate (PIP3), the product of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinases (PI3Ks), and PIM serine kinases as important regulators of T lymphocyte metabolism (18). However, it is likely that T cells will need to use diverse mechanisms to cope with the energy demands of an immune response. This study shows that triggering of the TCR results in the rapid activation of AMPK via a Ca2+–CaMKK-dependent pathway. The data provide novel insight that Ca2+ signaling in T cells regulates an evolutionally conserved kinase that controls the conservation and production of ATP.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Ca2+ activation of AMPKα1 in T cells

Fig. 1 A shows that mouse and human T cells express the AMPKα1 catalytic domain but do not express detectable levels of AMPKα2. Pharmacological agents that elevate [Ca2+]i (e.g., Ca2+ ionophores) can mimic many aspects of antigen receptor triggering and are widely used to probe the Ca2+ signaling pathways in lymphocytes. Thus, to investigate the possible Ca2+ regulation of AMPK in T cells, primary human T lymphoblasts were stimulated with the Ca2+ ionophore ionomycin and monitored for the phosphorylation of Thr-172 in the activation loop of AMPKα1, a marker of AMPK activation. The data show that ionomycin induced the rapid and sustained phosphorylation of AMPK Thr-172 (Fig. 1 B). Phosphorylation of Thr-172 was not induced when T cells were stimulated with the phorbol ester (phorbol 12,13-dibutyrate [PdBu]), which mimics the action of DAG. Ionomycin-induced Thr-172 phosphorylation was also seen in mouse thymocytes (Fig. 1 C) and peripheral T cells (Fig. 1 D). Thapsigargin, which inhibits the ER Ca2+-ATPase pump and, thereby, promotes Ca2+ release from the ER, also induced Thr-172 AMPK phosphorylation (Fig. 1 D). Further experiments examined the impact of elevating intracellular Ca2+ levels on the phosphorylation of the AMPK substrate Ser-79 in acetyl-CoA carboxylase (ACC). Fig. 1 E shows that ionomycin but not phorbol ester induced ACC phosphorylation. Phorbol esters induce a wide range of energy-consuming processes in lymphocytes, including changes in cell adhesion, motility, and gene expression. Accordingly, the failure of phorbol esters to induce AMPK or ACC phosphorylation indicates that this is a selective response to the elevation of [Ca2+]i and is not a response to T cell activation per se.

Figure 1.

Ca2+ activation of AMPKα1 in T cells. (A) Mouse and human T cells express the AMPKα1 isoform. Data show Western blot (WB) analysis of cell lysates from mouse thymocytes or human and mouse T lymphoblasts probed with antisera specific for AMPKα1 and α2. Protein extracts corresponding to 10 and 20 million mouse thymocytes or 5, 10, and 20 million mouse and human T blast cells were loaded successively on the gel. Cell lysates prepared from mouse muscle extracts were used as a positive control for AMPKα2 expression. (B) Ionomycin but not phorbol ester induces AMPK Thr-172 phosphorylation in human T lymphocytes. Human T cells were unstimulated or treated with 20 ng/ml PdBu or 0.5 μg/ml ionomycin for the indicated time periods (given in minutes). (C) Ionomycin induces AMPK Thr-172 phosphorylation in mouse thymocytes. Mouse thymocytes were unstimulated or treated with 0.5 μg/ml ionomycin in duplicate. (B and C) The data show Western blot analyses of cell lysates prepared from these cells with pThr-172–AMPK or AMPKα1 antisera. (D) Ionomycin and thapsigargin induce AMPK Thr-172 phosphorylation in mouse and human T cells. Mouse and human T lymphocytes were unstimulated (in duplicate for mouse T cells and in triplicate for human cells) or treated with 0.5 μg/ml ionomycin or 500 nM thapsigargin (in duplicate in the case of human cells). Data show Western blot analyses with pThr-172–AMPK or AMPKα1 antisera. (E) Iomomycin but not phorbol ester induces phosphorylation of the AMPK substrate ACC. Human T cells were unstimulated or treated with 20 ng/ml PdBu or 0.5 μg/ml ionomycin in a duplicate experiment. Proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE and Western blotted using a pSer-79–ACC antibody. The quantity of ACC loaded on the gel was measured by its ability to bind streptavidin. Western blots were analyzed by the Odyssey Infrared Imaging System (LI-COR Biosciences). Data show the ratio of phospho-ACC to the total ACC signal.

TCR activation of AMPK

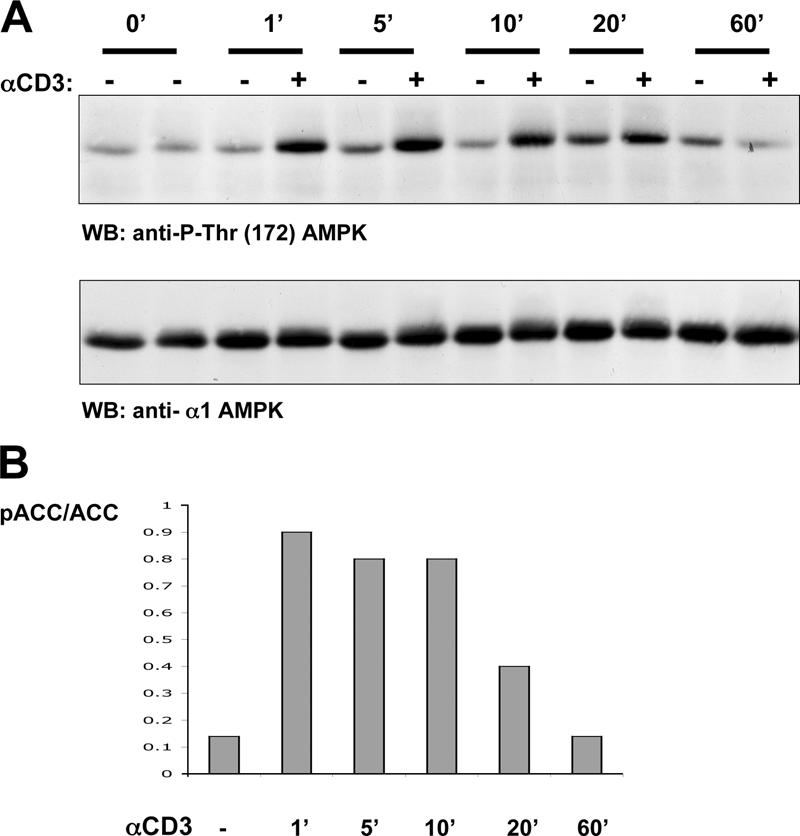

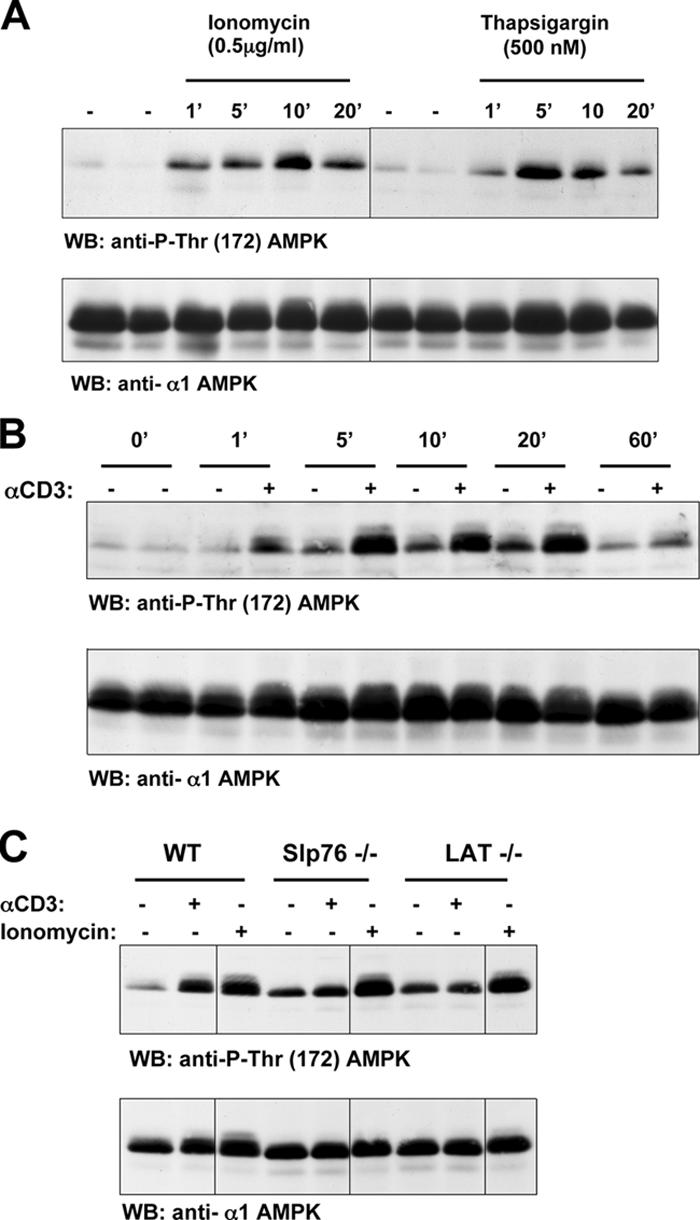

Increased [Ca2+]i is an immediate response to TCR triggering. Fig. 2 A shows that TCR triggering of human T cells rapidly increased AMPK Thr-172 phosphorylation and induced phosphorylation of the AMPK substrate ACC on Ser-79 (Fig. 2 B). The human T leukemic cell line Jurkat has low basal levels of AMPK Thr-172 phosphorylation, but this is readily induced when cells are stimulated with ionomycin, thapsigargin, or via the TCR (Fig. 3, A and B). To probe the signaling pathways used by the TCR to regulate AMPK, we examined AMPK activity in Jurkat cells that lack expression of the adapters LAT or SLP76. These molecules coordinate the assembly of the PLCγ1 signaling complex and are required for the TCR to increase [Ca2+]i (19, 20). Fig. 3 C shows that TCR ligation does not induce the phosphorylation of AMPK on Thr-172 in SLP76- or LAT-deficient Jurkat cells, whereas ionomycin activated AMPK in both cell clones. The failure of TCR activation of AMPK in Jurkat cells with defective TCR-mediated Ca2+ flux is consistent with a model whereby the TCR regulates AMPK via a Ca2+-regulated mechanism. An alternative possibility is that TCR activates AMPK because it increases cellular AMP/ATP ratios. To address this possibility, we directly measured cellular ATP and AMP concentrations in T cells stimulated via TCR. Fig. 4 A shows that 2-deoxyglucose, which is known to deplete cellular ATP, rapidly increases the cellular AMP/ATP ratio in T cells, whereas triggering of the TCR complex did not. AMPK can thus be activated by energy stress that causes ATP depletion, but the ability of TCR to activate AMPK is not secondary to ATP depletion.

Figure 2.

TCR activation of AMPK in human T cells. (A) TCR stimulation induces AMPK Thr-172 phosphorylation in human peripheral blood-derived T cells. Human T cells were unstimulated or treated with 10 μg/ml of the CD3 antibody UCHT1 to cross-link the TCR for the indicated time periods (given in minutes). The data show Western blot (WB) analyses of cell lysates prepared from these T cells with pThr-172–AMPK or AMPKα1 antisera. (B) TCR-stimulated phosphorylation of the AMPK substrate ACC. Human T cells were unstimulated or treated with 10 μg/ml UCHT1, a CD3 cross-linking antibody, for the indicated time periods (given in minutes). Proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE and Western blotted using the pSer79-ACC antibody. The quantity of ACC loaded on the gel was measured by its ability to bind streptavidin. Western blots were analyzed by the Odyssey Infrared Imaging System. Data show the ratio of phospho-ACC to the total ACC signal.

Figure 3.

Ca2+ and TCR activation of AMPK in Jurkat cells. (A) Ionomycin and thapsigargin induce AMPK Thr-172 phosphorylation in Jurkat cells. Jurkat cells were unstimulated or treated with 0.5 μg/ml ionomycin or 500 nM thapsigargin for the indicated time periods (given in minutes). (B) TCR stimulation of AMPK Thr-172 phosphorylation in Jurkat cells. Jurkat T cells were unstimulated or treated with 10 μg/ml of the CD3 antibody UCHT1 to cross-link the TCR for the indicated time periods (given in minutes). (C) TCR stimulation of AMPK Thr-172 phosphorylation is dependent on LAT and SLP76. Wild-type, Slp76-, or LAT-negative Jurkat cells were unstimulated or treated with 10 μg/ml of the CD3 antibody UCHT1 or 0.5 μg/ml ionomycin for 5 min. (A–C) The data show Western blot (WB) analyses of cell lysates prepared from these T cells with pThr-172–AMPK or AMPKα1 antisera. Black lines indicate that intervening lanes have been spliced out.

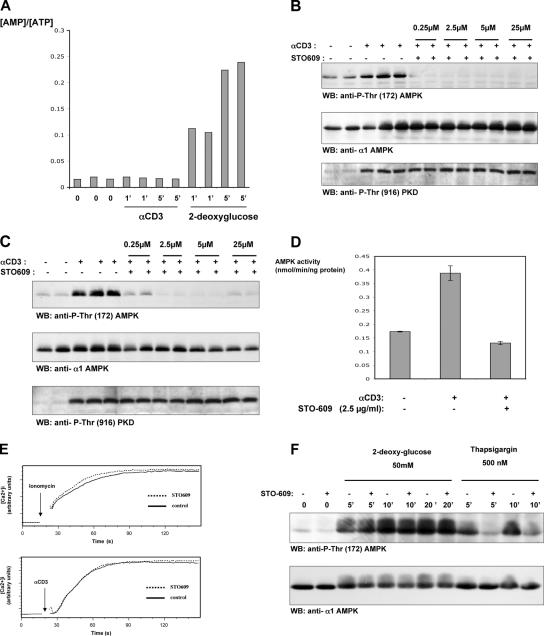

Figure 4.

The CaMKK inhibitor STO-609 inhibits TCR activation of AMPK. (A) AMP/ATP ratios in TCR-triggered T cells are comparable with those in unstimulated cells. Jurkat cells were unstimulated or treated with 10 μg/ml of the CD3 antibody UCHT1 or 50 mM 2-deoxyglucose for 1 and 5 min. The data show the ratios of AMP and ATP intracellular concentrations over the indicated time periods (given in minutes) under different stimulation conditions. (B and C) The CaMKK inhibitor STO-609 inhibits TCR-induced AMPK Thr-172 phosphorylation in human peripheral blood-derived T cells (B) and in Jurkat cells (C). Human T cells (B) and Jurkat T cells (C) were pretreated with STO-609 at the indicated concentrations and were stimulated with the CD3 antibody UCHT1 for 5 min. The data show Western blot (WB) analyses of cell lysates prepared from these T cells with pThr-172–AMPK, AMPKα1 antisera, or pSer-916–PKD antibodies. (D) The CaMKK inhibitor STO-609 inhibits TCR-dependent AMPK activation in human T cells. Human T cells were pretreated with 2.5 μM STO-609 and were stimulated with the CD3 antibody UCHT1 for 5 min. Cells were lysed, and the AMPKα1 subunits were immunoprecipitated both from stimulated and unstimulated cells. Data show the catalytic activity of the immunoprecipitated AMPK in nanomoles/minute/nanogram protein units (mean ± SEM [error bars]; n = 3). (E) The CaMKK inhibitor STO-609 does not inhibit TCR or ionomycin-induced increases in intracellular Ca2+ concentration. Jurkat T cells were labeled with 4.5 μM Indo-1 and treated with 2.5 μM STO-609 as indicated and were stimulated with 10 μg/ml of the CD3 antibody UCHT1 or 0.5 μg/ml ionomycin for the indicated times. [Ca2+]i was then analyzed by flow cytometry. Data show [Ca2+]i over the indicated time periods under different stimulation conditions. (F) 2-deoxyglucose–induced AMPK Thr-172 phosphorylation is resistant to STO-609. Untreated and STO-609–pretreated Jurkat cells were stimulated with 50 mM 2-deoxyglucose or 500 nM thapsigargin for the indicated time periods (given in minutes). Data show Western blot analyses of cell lysates prepared from these T cells with pThr-172–AMPK or AMPKα1 antisera.

The CaMKK inhibitor STO-609 inhibits TCR activation of AMPK

To examine the role of CaMKK in AMPK regulation in T cells, experiments with the CaMKK selective inhibitor STO-609 were performed. Fig. 4 (B–D) shows that STO-609 prevents TCR-mediated increases in AMPK activity. STO-609 did not prevent the TCR-induced activation of protein kinase D (PKD; Fig. 4 B). PKD activation is absolutely dependent on PLCγ-mediated increases in intracellular DAG, and an intact PKD response demonstrates that STO-609 does not affect PLC regulation. Similarly, the data in Fig. 4 E show that STO-609 did not prevent TCR-mediated increases in [Ca2+]i. STO-609 also had no effect on the activation of AMPK induced by 2-deoxyglucose, which regulates AMPK via LKB1 (Fig. 4 F).

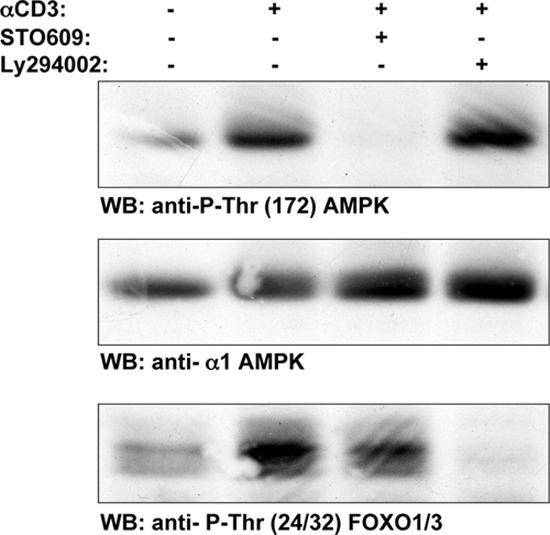

TCR activation of AMPK is not PI3K dependent

Jurkat cells do not express PTEN (phosphatase and tensin homologue deleted on chromosome 10) and have high basal levels of PIP3 and constitutive activation of PKB–Akt. PI3K-mediated signaling pathways, specifically PKB–Akt, regulate T cell metabolism (21, 22), but the low basal activity of AMPK in Jurkat cells argues that the elevation of PIP3 is not sufficient to activate this kinase (Fig. 3, A and B). Fig. 5 also shows that TCR-induced phosphorylation of AMPK Thr-172 was not sensitive to the PI3K inhibitor LY294002, whereas this inhibitor did suppress the TCR-induced phosphorylation of FOXO3A on the PKB–Akt site Thr-32. Conversely, STO-609 treatment, which inhibited the TCR-induced phosphorylation of AMPK, did not block the TCR-mediated phosphorylation of FOXO3A. The PI3K insensitivity of AMPK activation in T cells argues that the activation of AMPK via TCR is a primary response to T cell activation and is not an indirect response to TCR-induced energy depletion.

Figure 5.

TCR-induced phosphorylation of AMPK Thr-172 is not prevented by Ly294002. Human T cells were pretreated with either 2.5 μM STO-609 or 10 μM Ly294002 and were stimulated with the CD3 antibody UCHT1 for 5 min. Data show Western blot analyses of cell lysates prepared from these T cells with pThr-172–AMPK, AMPKα1, or phospho-Thr24/Thr32-FOXO1/3 antisera.

In summary, in T lymphocytes, triggering of TCR activates AMPK, a key regulator of cellular energy homeostasis. TCR regulation of AMPK is mediated via a [Ca2+]i–CaMKK pathway and is not a response to energy stress. Thus, in T cells, AMPK does not function solely to restore energy balance after the depletion of energy stores. Rather, increases in [Ca2+]i that activate CaMKKs stimulate AMPK to promote the conservation and accelerated production of ATP in anticipation of energy supplies becoming depleted. The ability to anticipate energy-intensive processes would be advantageous for cells that need to rapidly respond to an increased demand for ATP. In this context, triggering of the TCR initiates an energy-demanding program that is only successful when cellular energy production satisfies the biosynthetic demands of an immune response. T cells will need to use diverse mechanisms to cope with the energy demands of an immune stimulus, and Ca2+ activation of AMPK would allow a rapid activation of ATP production before the onset of cell proliferation and differentiation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Reagents and antibodies.

STO-609 was purchased from Tocris, LY294002 was obtained from Promega, ionomycin and PdBu were purchased from Calbiochem, and thapsigargin was obtained from Sigma-Aldrich. AMPK antibodies (α1, α2, and pT172), pSer-79 of ACC, and pSer-916 of PKD were described previously (23–25). Phospho-Thr24/Thr32-FOXO1/3 antibody was obtained from Cell Signaling Technology.

Cells and stimulation.

Mouse thymocytes were isolated from 6–8-wk-old C57/BL6/J mice. Human peripheral blood-derived T lymphoblasts and C57/BL6/J splenic mouse T lymphoblasts were generated and maintained as described previously (26, 27). LAT- or SLP76-null Jurkat mutants have been described previously (19, 20). For stimulations, T cells at 5 × 106/ml in RPMI supplemented with 1% FCS were treated with one of the following stimuli: 20 ng/ml PdBu, 0.5 μg/ml ionomycin, 500 nM thapsigargin, or 10 μg/ml of the CD3 antibody UCHT1. Western blot analyses and AMPK catalytic assays were performed as described previously (17, 25). Nucleotide ratios were determined after perchloric acid extraction (28) of Jurkat cells using capillary electrophoresis (29). Ca2+ flux analysis used standard protocols with Indo-1 and an LSR flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson; reference 30). All data shown are representative of at least three independent experiments.

Acknowledgments

Peter Tamás is a long-term Fellow of the Federation of European Biochemical Societies. These studies were supported by the Wellcome Trust and an integrated project from the European Commission (LSHM-CT-2004-005272).

The authors have no conflicting financial interests.

References

- 1.Kane, L.P., J. Lin, and A. Weiss. 2000. Signal transduction by the TCR for antigen. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 12:242–249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Winslow, M.M., J.R. Neilson, and G.R. Crabtree. 2003. Calcium signalling in lymphocytes. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 15:299–307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Heissmeyer, V., F. Macian, R. Varma, S.H. Im, F. Garcia-Cozar, H.F. Horton, M.C. Byrne, S. Feske, K. Venuprasad, H. Gu, et al. 2005. A molecular dissection of lymphocyte unresponsiveness induced by sustained calcium signalling. Novartis Found. Symp. 267:165–174, discussion 174–169. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Im, S.H., and A. Rao. 2004. Activation and deactivation of gene expression by Ca2+/calcineurin-NFAT-mediated signaling. Mol. Cells. 18:1–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schwartz, R.H. 2003. T cell anergy. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 21:305–334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rao, A., C. Luo, and P.G. Hogan. 1997. Transcription factors of the NFAT family: regulation and function. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 15:707–747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lin, M.Y., T. Zal, I.L. Ch'en, N.R. Gascoigne, and S.M. Hedrick. 2005. A pivotal role for the multifunctional calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II in T cells: from activation to unresponsiveness. J. Immunol. 174:5583–5592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Melander Gradin, H., U. Marklund, N. Larsson, T.A. Chatila, and M. Gullberg. 1997. Regulation of microtubule dynamics by Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent kinase IV/Gr-dependent phosphorylation of oncoprotein 18. Mol. Cell. Biol. 17:3459–3467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Marklund, U., N. Larsson, G. Brattsand, O. Osterman, T.A. Chatila, and M. Gullberg. 1994. Serine 16 of oncoprotein 18 is a major cytosolic target for the Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent kinase-Gr. Eur. J. Biochem. 225:53–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Park, I.K., and T.R. Soderling. 1995. Activation of Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase (CaM-kinase) IV by CaM-kinase kinase in Jurkat T lymphocytes. J. Biol. Chem. 270:30464–30469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Anderson, K.A., R.L. Means, Q.H. Huang, B.E. Kemp, E.G. Goldstein, M.A. Selbert, A.M. Edelman, R.T. Fremeau, and A.R. Means. 1998. Components of a calmodulin-dependent protein kinase cascade. Molecular cloning, functional characterization and cellular localization of Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase kinase beta. J. Biol. Chem. 273:31880–31889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hawley, S.A., D.A. Pan, K.J. Mustard, L. Ross, J. Bain, A.M. Edelman, B.G. Frenguelli, and D.G. Hardie. 2005. Calmodulin-dependent protein kinase kinase-beta is an alternative upstream kinase for AMP-activated protein kinase. Cell Metab. 2:9–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Woods, A., K. Dickerson, R. Heath, S.P. Hong, M. Momcilovic, S.R. Johnstone, M. Carlson, and D. Carling. 2005. Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase kinase-beta acts upstream of AMP-activated protein kinase in mammalian cells. Cell Metab. 2:21–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hurley, R.L., K.A. Anderson, J.M. Franzone, B.E. Kemp, A.R. Means, and L.A. Witters. 2005. The Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase kinases are AMP-activated protein kinase kinases. J. Biol. Chem. 280:29060–29066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hardie, D.G. 2004. The AMP-activated protein kinase pathway–new players upstream and downstream. J. Cell Sci. 117:5479–5487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Woods, A., S.R. Johnstone, K. Dickerson, F.C. Leiper, L.G. Fryer, D. Neumann, U. Schlattner, T. Wallimann, M. Carlson, and D. Carling. 2003. LKB1 is the upstream kinase in the AMP-activated protein kinase cascade. Curr. Biol. 13:2004–2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hawley, S.A., J. Boudeau, J.L. Reid, K.J. Mustard, L. Udd, T.P. Makela, D.R. Alessi, and D.G. Hardie. 2003. Complexes between the LKB1 tumor suppressor, STRAD alpha/beta and MO25 alpha/beta are upstream kinases in the AMP-activated protein kinase cascade. J. Biol. 2:28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fox, C.J., P.S. Hammerman, and C.B. Thompson. 2005. Fuel feeds function: energy metabolism and the T-cell response. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 5:844–852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Finco, T.S., T. Kadlecek, W. Zhang, L.E. Samelson, and A. Weiss. 1998. LAT is required for TCR-mediated activation of PLCgamma1 and the Ras pathway. Immunity. 9:617–626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yablonski, D., M.R. Kuhne, T. Kadlecek, and A. Weiss. 1998. Uncoupling of nonreceptor tyrosine kinases from PLC-gamma1 in an SLP-76-deficient T cell. Science. 281:413–416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Frauwirth, K.A., J.L. Riley, M.H. Harris, R.V. Parry, J.C. Rathmell, D.R. Plas, R.L. Elstrom, C.H. June, and C.B. Thompson. 2002. The CD28 signaling pathway regulates glucose metabolism. Immunity. 16:769–777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Frauwirth, K.A., and C.B. Thompson. 2004. Regulation of T lymphocyte metabolism. J. Immunol. 172:4661–4665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sugden, C., R.M. Crawford, N.G. Halford, and D.G. Hardie. 1999. Regulation of spinach SNF1-related (SnRK1) kinases by protein kinases and phosphatases is associated with phosphorylation of the T loop and is regulated by 5′-AMP. Plant J. 19:433–439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Woods, A., I. Salt, J. Scott, D.G. Hardie, and D. Carling. 1996. The alpha1 and alpha2 isoforms of the AMP-activated protein kinase have similar activities in rat liver but exhibit differences in substrate specificity in vitro. FEBS Lett. 397:347–351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Matthews, S.A., E. Rozengurt, and D. Cantrell. 1999. Characterization of serine 916 as an in vivo autophosphorylation site for protein kinase D/Protein kinase Cmu. J. Biol. Chem. 274:26543–26549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cornish, G.H., L.V. Sinclair, and D.A. Cantrell. 2006. Differential regulation of T cell growth by Interleukin 2 and IL-15. Blood. 10.1182/blood-2005-12-4827. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 27.Astoul, E., A.D. Laurence, N. Totty, S. Beer, D.R. Alexander, and D.A. Cantrell. 2003. Approaches to define antigen receptor-induced serine kinase signal transduction pathways. J. Biol. Chem. 278:9267–9275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gadalla, A.E., T. Pearson, A.J. Currie, N. Dale, S.A. Hawley, M. Sheehan, W. Hirst, A.D. Michel, A. Randall, D.G. Hardie, and B.G. Frenguelli. 2004. AICA riboside both activates AMP-activated protein kinase and competes with adenosine for the nucleoside transporter in the CA1 region of the rat hippocampus. J. Neurochem. 88:1272–1282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sakamoto, K., E. Zarrinpashneh, G.R. Budas, A.C. Pouleur, A. Dutta, A.R. Prescott, J.L. Vanoverschelde, A. Ashworth, A. Jovanovic, D.R. Alessi, and L. Bertrand. 2005. Deficiency of LKB1 in heart prevents ischemia-mediated activation of AMPKalpha2 but not AMPKalpha1. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 290:E780–E788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Avril, T., S.D. Freeman, H. Attrill, R.G. Clarke, and P.R. Crocker. 2005. Siglec-5 (CD170) can mediate inhibitory signaling in the absence of immunoreceptor tyrosine-based inhibitory motif phosphorylation. J. Biol. Chem. 280:19843–19851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]