Abstract

Superoxide produced by the phagocyte reduced nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH) oxidase is essential for host defense. Enzyme activation requires translocation of p67phox, p47phox, and Rac-GTP to flavocytochrome b 558 in phagocyte membranes. To examine the regulation of phagocytosis-induced superoxide production, flavocytochrome b558, p47phox, p67phox, and the FcγIIA receptor were expressed from stable transgenes in COS7 cells. The resulting COSphoxFcγR cells produce high levels of superoxide when stimulated with phorbol ester and efficiently ingest immunoglobulin (Ig)G-coated erythrocytes, but phagocytosis did not activate the NADPH oxidase. COS7 cells lack p40phox, whose role in the NADPH oxidase is poorly understood. p40phox contains SH3 and phagocyte oxidase and Bem1p (PB1) domains that can mediate binding to p47phox and p67phox, respectively, along with a PX domain that binds to phosphatidylinositol-3-phosphate (PI(3)P), which is generated in phagosomal membranes. Expression of p40phox was sufficient to activate superoxide production in COSphoxFcγR phagosomes. FcγIIA-stimulated NADPH oxidase activity was abrogated by point mutations in p40phox that disrupt PI(3)P binding, or by simultaneous mutations in the SH3 and PB1 domains. Consistent with an essential role for PI(3)P in regulating the oxidase complex, phagosome NADPH oxidase activation in primary macrophages ingesting IgG-coated beads was inhibited by phosphatidylinositol 3 kinase inhibitors to a much greater extent than phagocytosis itself. Hence, this study identifies a role for p40phox and PI(3)P in coupling FcγR-mediated phagocytosis to activation of the NADPH oxidase.

Phagocytic leukocytes are essential for intact innate immunity to bacterial and fungal pathogens. Upon activation by either soluble stimuli or during phagocytosis, a reduced nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH) oxidase generates large quantities of superoxide at the plasma or phagosomal membrane, which is converted into reactive oxidants used for microbial killing (1–3). The phagocyte NADPH oxidase is comprised of two integral membrane proteins, gp91phox and p22phox, that together form the oxidase flavocytochrome b 558, as well as p47phox, p67phox, and Rac-GTP, which translocate from the cytosol to the membrane to activate electron transport through the flavocytochrome (2, 3). Attesting to its importance in host defense, genetic defects in the aforementioned phox (phagocyte oxidase) subunits result in chronic granulomatous disease, an inherited disorder characterized by recurrent pyogenic infections (1). Conversely, excessive or inappropriate superoxide release has been implicated in the pathogenesis of inflammatory tissue injury. Hence, the activity of this enzyme is highly regulated.

NADPH oxidase activation is triggered by still incompletely defined events downstream of cell surface receptors engaged by opsonized microbes or soluble inflammatory mediators. These include phosphorylation of p47phox on multiple serine residues, which unmasks tandem SH3 domains that bind to a proline-rich motif in p22phox to enable membrane recruitment of p47phox (4). The p47phox subunit also contacts gp91phox in a second interaction with the flavocytochrome that is essential for translocation (5, 6). In turn, p47phox functions as an adaptor protein to mediate translocation of p67phox as well as to optimally position p67phox and Rac-GTP in the active enzyme complex (2, 3, 7). The p47phox and p67phox subunits are linked via a reciprocal interaction involving a proline-rich region (PRR) and SH3 domain, respectively, in the C termini of these subunits (Fig. 1) (8–11). p67phox contains an essential “activation domain,” which interacts with flavocytochrome b 558 to promote electron transfer between NADPH and FAD (12). NADPH oxidase activation also requires concurrent activation and membrane translocation of Rac, which binds to the N terminus of p67phox and flavocytochrome b 558 to induce additional conformational changes necessary for efficient electron transport to O2 (13–16).

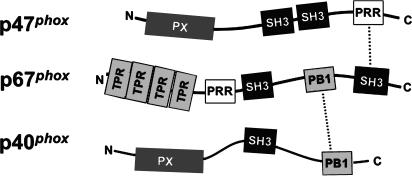

Figure 1.

Interactions between p47phox, p67phox, and p40phox subunits of the phagocyte NADPH oxidase. Structural motifs and identified interactions between p47phox, p67phox, and p40phox are shown schematically. The p47phox subunit contains a PX domain, two SH3 domains, and a C-terminal PRR. A domain containing four tetratricopeptide repeat (TPR) motifs comprises the N terminus of p67phox, followed by an SH3, PB1, and second SH3 domain. The p67phox subunit also contains a PRR adjacent to the N-terminal SH3 domain. p40phox also contains a PX and PB1 domain, along with an intervening SH3 domain. In the p47phox–p67phox–p40phox complex, p47phox associates with p67phox via a high-affinity tail-to-tail interaction involving the C-terminal PRR and SH3 domains in p47phox and p67phox, respectively, whereas p40phox is tethered to p67phox via a back-to-front interaction between their PB1 domains.

In resting neutrophils, a third protein, p40phox, is constitutively associated with p67phox via a high-affinity interaction between phagocyte oxidase and Bem1p (PB1) motifs present in the C-terminal region of each protein (3, 17–21). The p40phox subunit translocates to the membrane upon cellular activation, a process that is dependent on p47phox (22) and appears to involve a ternary complex in which p67phox is tethered both to p40phox and to p47phox via the PB1 domain and SH3–PRR interactions, respectively (Fig. 1) (9–11, 23). An SH3 domain in p40phox is also capable of interacting with the PRR in p47phox (24–26), although in vitro binding studies indicate that the affinity is at least 10-fold lower than that for the p67phox SH3 domain (10, 11). The N terminus of p40phox contains a PX (phox homology) domain, which binds to phosphatidylinositol-3-phosphate (PI(3)P) (27, 28). The role played by p40phox in regulating the NADPH oxidase remains poorly understood. This subunit is not required for high level O2 − formation either in cell-free assays or whole cell model systems (29, 30), and both inhibitory and stimulatory effects of p40phox have been reported using soluble agonists (9, 28, 31–34).

To investigate the molecular mechanisms leading to NADPH oxidase activation, we recently developed a whole cell model in which human cDNAs for gp91phox, p22phox, p47phox, and p67phox are expressed as stable transgenes in monkey kidney COS7 fibroblasts (30). These “COSphox” cells are much more amenable to transfection compared with primary phagocytes, which facilitates expression of other recombinant proteins potentially involved in regulating oxidase activity. COSphox cells exhibit robust superoxide production when stimulated by either PMA or arachidonic acid, two soluble agonists commonly used to activate the neutrophil NADPH oxidase. Assembly of the active oxidase recapitulates features of the phagocyte enzyme, with superoxide production dependent on Rac activation, the presence of all four essential phox subunits, the p67phox activation domain, and multiple serine residues in p47phox previously implicated as critical phosphorylation sites enabling translocation (30).

The regulation of NADPH oxidase activation during phagocytosis is poorly defined. Previous studies have established that introduction of the FcγIIA receptor enables COS7 cells to efficiently ingest IgG-opsonized particles in a manner similar to professional phagocytes (35–38). We therefore used the COSphox system as a platform to analyze requirements for FcγIIA receptor–induced NADPH oxidase activation in whole cells. Although COSphox cells expressing the FcγIIA receptor from a stable transgene produce superoxide when stimulated with phorbol ester and readily ingest IgG-coated erythrocytes, phagocytosis did not activate the NADPH oxidase. Further studies indicated that transient or stable transfection of p40phox in COSphoxFcγR cells was sufficient to activate intraphagosomal superoxide production and suggest critical roles for PI(3)P, a phosphoinositide that is generated on maturing phagosomes (39, 40), along with the p40phox SH3 and PB1 domains, which can interact with p47phox and p67phox subunits of the oxidase.

RESULTS

p40phox is sufficient for coupling FcγR-induced phagocytosis to NADPH oxidase activation in COSphox cells

To examine whether phagocytosis triggers NADPH oxidase activation in COSphox fibroblasts, which already express the phagocyte flavocytochrome b 558, p47phox, and p67phox, a retroviral vector was used to introduce a stable transgene for the human FcγIIA receptor. Expression of the FcγIIA receptor is sufficient to endow COS7 cells with the ability to efficiently bind and internalize IgG-opsonized particles (35–37). Cell surface expression of the FcγIIA receptor in the transduced COSphox cells, which will be referred to as COSphoxFcγR cells, was comparable to levels seen in monocytes (Fig. 2 A) or human neutrophils (not depicted).

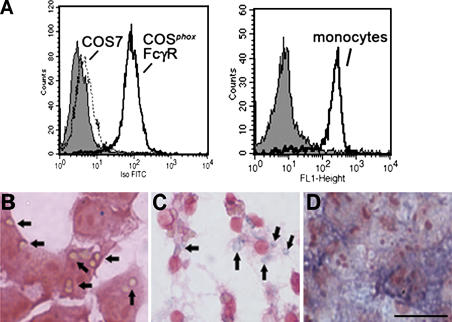

Figure 2.

Expression of FcγIIA receptor, phagocytosis, and NADPH oxidase activity. (A) Analysis of FcγIIA expression by flow cytometry using an FITC-conjugated antibody against CD32 is shown for COS7 and COSphoxFcγR cells (left) and human peripheral blood monocytes (right) as indicated. The gray histogram indicates staining of either COSphoxFcγR or monocytes with an FITC-conjugated isotype control mAb. (B and C) Phagocytosis of IgG–sheep RBCs in media containing NBT. (B) COSphoxFcγR cells incubated with IgG-RBCs for 30 min at 37°C. Many of the ingested IgG-RBCs, which appear tan, are indicated by arrows. (C) Murine bone marrow–derived macrophages incubated with IgG-RBCs for 10 min at 37°C. Formazan-stained phagosomes, indicative of intraphagosomal superoxide production, are indicated by arrows. (D) COSphoxFcγR cells incubated with 100 ng/ml phorbol myristate acetate for 30 min, showing diffuse formazan deposits. Bar, 30 μm.

To assess whether phagocytosis induced superoxide production, COSphoxFcγR cells were incubated with IgG- opsonized RBCs (IgG-RBCs) in the presence of nitroblue tetrazolium (NBT) as a probe to detect superoxide, which reduces NBT into purple formazan deposits. After lysis of uningested IgG-RBCs, microscopic examination revealed numerous ingested RBCs but no detectable formazan (Fig. 2 B). In comparison, murine macrophages after ingestion of IgG-RBCs show formazan deposits within phagosomes, indicative of NADPH oxidase activity (Fig. 2 C). As evidence of their ability to generate superoxide, COSphoxFcγR cells stimulated with PMA in the presence of NBT showed abundant and diffuse formazan staining (Fig. 2 D), with NADPH oxidase activity similar to parental COSphox cells (30) when quantitated by cytochrome c reduction (not depicted).

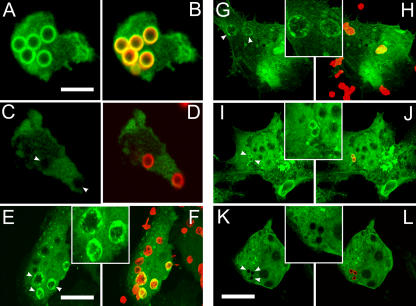

The absence of NADPH oxidase activity in COSphoxFcγR phagosomes, despite the capacity to produce superoxide in response to PMA, suggested that these cells lack one or more proteins important for coupling FcγIIA signaling to NADPH oxidase activity. COS7 cells lack p40phox, which is expressed almost exclusively in hematopoietic cells (41, 42). Importantly, p40phox contains a PX domain that preferentially binds to PI(3)P (27, 28), a phosphoinositide generated on the cytosolic side of maturing phagosomal membranes by the action of class III PI3 kinase, which persists after phagosome closure (39, 40). Although p40phox translocates to membranes of PMA-stimulated neutrophils (22), which appears to involve the formation of a complex with p67phox and p47phox (3), the association of p40phox with phagosome membranes has not been reported. In granulocyte-differentiated PLB-985 cells ingesting IgG-opsonized latex beads, a fusion of full-length p40phox and enhanced yellow fluorescence protein (EYFP) localized to phagosome membranes (Fig. 3, A and B), but not if cells were treated with wortmannin (Fig. 3, C and D). Next, to verify that IgG-RBC phagosomes in COSphoxFcγR cells accumulate PI(3)P, we used a PX domain of p40phox fused to EYFP, which specifically localizes to sites of PI(3)P in a PI3 kinase–dependent manner (27, 28). As shown in Fig. 3 (E and F), IgG-RBC phagosomes in COSphoxFcγR cells readily accumulate EYFP-p40PX. Moreover, the fusion of full-length p40phox and EYFP showed a similar distribution in COSphoxFcγR cells after phagocytosis of IgG-RBCs (Fig. 3, G and H) or IgG-opsonized latex beads (Fig. 3, I and J). Consistent with the importance of PI3 kinase activity in generating PI(3)P, no phagosomal localization of EYFP-p40phox was seen in COSphoxFcγR cells treated with wortmannin before phagocytosis of IgG-opsonized latex beads (Fig. 3, K and L).

Figure 3.

Localization of EYFP-p40PX and full-length EYFP-p40phox in PLB-985 granulocytes and COSphoxFcγR cells during phagocytosis. (A, C, E, G, I, and K) EYFP fluorescence (green). (B, D, F, H, J, and L) EYFP and Alexa Fluor 555 (IgG-RBCs or IgG-beads, red). Regions in which red and green labels overlap appear orange or yellow. (A–D) PLB-985 granulocytes. (E–L) COSphoxFcγR cells. (E and F) EYFP-p40PX, IgG-RBCs. (G and H) Full-length EYFP-p40phox, IgG-RBCs. (A–D and I–L) Full-length EYFP-p40phox IgG beads without (A, B, I, and J) and with (C, D, K, and L) wortmannin. Images are representative of two to three independent experiments. Arrowheads point to representative phagosomes. Bars: A, 5 μm; C and L, 20 μm. Insets are magnified twofold relative to the adjacent panels.

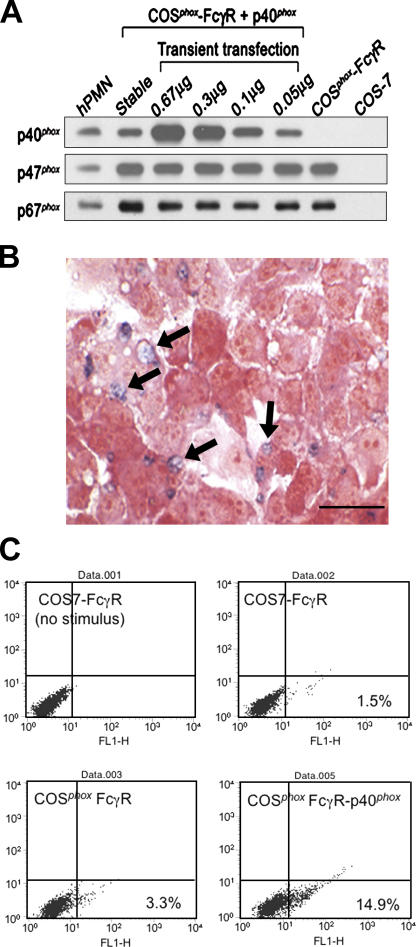

We next expressed untagged p40phox in COSphoxFcγR cells using vectors for either transient or stable expression (Fig. 4 A). Levels of p40phox in lysates prepared from transiently transfected cells were proportional to the amount of plasmid, which for the smallest amount was approximately twofold higher than in human neutrophils, taking into account the transfection efficiency and normalizing to protein content (Fig. 4 A). p40phox expression in a COSphoxFcγR derivative with a stable transgene for p40phox was similar to that in human neutrophils (Fig. 4 A). For comparison, expression of p47phox and p67phox in COSphoxFcγR cells was two- to threefold higher than in human neutrophils (Fig. 4 A).

Figure 4.

Expression of p40phox in COSphoxFcγR cells and FcγR-elicited NADPH oxidase activity. Data shown is representative of at least three independent experiments. (A) Immunoblots of human neutrophil and COS7 cell lysates (10 μg protein per lane) probed with antibodies for p40phox, p47phox, and p67phox. COSphoxFcγR cells were transfected with either a stable p40phox transgene or with varying amounts of p40pRK5 for transient expression as indicated. (B) IgG-RBC–elicited NADPH oxidase activity in COSphoxFcγR cells expressing p40phox. Multiple formazan-stained phagosomes (arrows) in COSphoxFcγR transfected with 0.05 μg p40pRK5 (representative photomicrograph; bar, 30 μm). Similar numbers of formazan-stained phagosomes were present in COSphoxFcγR cells transfected with larger amounts of plasmid or expressing p40phox from a stable transgene. (C) Flow cytometry analysis of COSFcγR cell lines incubated with Fc OxyBURST Green–opsonized zymosan for 30 min. Fluorescence intensity is shown on the x axis.

Expression of p40phox was sufficient to reconstitute NADPH oxidase activation in COSphoxFcγR cells undergoing phagocytosis of IgG-RBCs, as indicated by the presence of formazan-stained phagosomes (Fig. 4 B). The deposition of formazan upon the reduction of NBT is a sensitive assay for superoxide and well suited to monitor the localized intracellular production of oxidants in a subpopulation of cells. As another probe to detect oxidant production by COSphoxFcγR-p40phox cells during phagocytosis of IgG-opsonized particles, we used Fc OxyBURST Green, which detects hydrogen peroxide via the oxidation of dichlorodihydroflurorescein covalently attached to antigen–antibody complexes (43). Although Fc OxyBURST Green alone was a poor stimulus for oxidant production by COSphoxFcγR-p40phox cells (not depicted), zymosan particles opsonized with Fc OxyBURST Green induced oxidant production in COSphoxFcγR-p40phox cells, but not in COS7-FcγR cells or COSphoxFcγR (Fig. 4 C).

NBT+ phagosomes were evident within 5 min of initiating phagocytosis, consistent with studies in phagocytosing macrophages and neutrophils (44, 45). Over the range of p40phox expression tested (Fig. 4 A), the frequency of cells with NBT+ phagosomes was similar. Only NBT− phagosomes were observed in COS7-FcγR cells, with or without p40phox, when the other phox subunits were absent (not depicted). In addition, phagocytosis of IgG-RBCs per se was unaffected by expression of p40phox. Up to 50–70% of COSphoxFcγR-p40phox cells ingesting IgG-RBCs during synchronized phagocytosis contained one to two NBT+ phagosomes. Results in transiently transfected cells were similar, after taking into account a transfection efficiency of ∼40%. Similar results were also seen upon expression of full-length EYFP-p40phox, which was present at levels comparable to untagged p40phox (not depicted). When taken together with the relative levels of p47phox and p67phox (Fig. 4 A), these data indicate that only approximately stoichiometric or near-stoichiometric levels of p40phox are required to activate superoxide production in phagosomes, and that placement of an N-terminal EYFP tag does not interfere with this function. Of note, oxidant production was restricted to the phagosomes in COSphoxFcγR cells expressing p40phox, as was also seen with the ingestion of IgG-RBCs by primary murine macrophages (Fig. 2 C) and human neutrophils (not depicted). Finally, NBT+ phagosomes were seen in only ∼50% of COSphoxFcγR cells expressing p40phox either by transient or stable transfection. Heterogeneity is also observed among cells or even individual phagosomes in primary phagocytes, where it is poorly understood but likely to reflect variable activation of signal transduction upon engagement of phagocytic receptors (46–48).

Mutations in the PX, SH3, or PB1 domains of p40phox impair FcγR-stimulated O2 − production in phagosomes

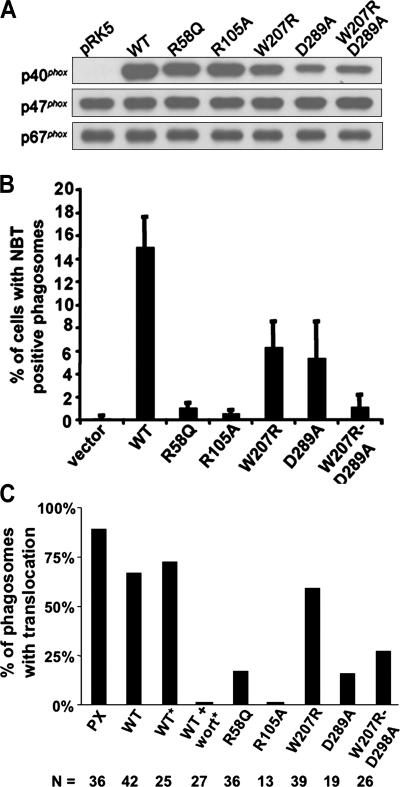

We next examined the effects of point mutations in p40phox on the coupling of FcγIIA-mediated phagocytosis to NADPH oxidase activation. Two different mutations in the PX domain were evaluated, where arginine residues at amino acid 58 and 105 were substituted with glutamine or alanine, respectively (R58Q or R105A), each of which eliminates PI(3)P binding but does not affect the overall structure of p40phox (49). We also introduced point mutations in the p40phox SH3 and PB1 domains. The p40phox SH3 domain interacts with the C-terminal PRR of p47phox (8, 10, 11, 24, 26), and a W207R substitution was placed at a conserved tryptophan residue in the SH3 consensus sequence. In addition, a D289A mutation was introduced in a cluster of acidic residues in the p40phox PB1 domain, which contact the PB1 domain in p67phox (19), thereby disrupting the interaction between these two proteins (32). Finally, a p40phox mutant with simultaneous W207R and D289A substitutions was produced.

Wild-type and p40phox mutants were introduced into COSphoxFcγR cells by transient transfection to evaluate phagosome NADPH oxidase activity during ingestion of IgG-RBCs. The wild-type and mutant proteins were expressed at generally comparable levels (Fig. 5 A). Levels of the D289A and W207R/D289A derivatives were consistently at 30–50% of the others but were still in the range that supports phagosome oxidase activity when using wild-type p40phox (Fig. 4 A). NBT+ phagosomes were only rarely observed using p40phox derivatives harboring point mutations at either site in the PX domain (R58Q or R105A) (Fig. 5 B). Point mutations in either the SH3 (W207R) or PB1 (D289A) domain also reduced the fraction of cells with NBT+ phagosomes, but only by ∼60% (Fig. 5 B). However, a p40phox derivative with simultaneous mutations in both the SH3 and PB1 domains resulted in a loss of function similar to the PX domain mutants in that NBT+ phagosomes were only rarely observed (Fig. 5 B). Thus, binding of PI(3)P appears to be essential for p40phox-mediated activation of superoxide production in COSphoxFcγR cells during phagocytosis of IgG-RBCs. In contrast, interactions mediated by the p40phox PB1 domain, which binds to p67phox, and the SH3 domain, which can bind to p47phox, were interdependent, with abrogation of NADPH oxidase activity only upon their simultaneous disruption. Collectively, these findings suggest that p40phox interacts with PI(3)P, p47phox, and p67phox to activate superoxide production during phagocytosis.

Figure 5.

Expression of p40phox mutants in COSphoxFcγR cells and effect on IgG–sheep RBC–elicited NADPH oxidase activity. Data shown is representative of at least three independent experiments. (A) Immunoblot of cell lysates from COSphoxFcγR cells transfected with 0.67 μg of either empty pRK5 or pRK5 containing cDNAs for either wild-type or mutant p40phox. Blots were probed with antibodies for p40phox, p47phox, and p67phox. (B) COSphoxFcγR cells were transfected as in A and incubated with IgG-RBCs in the presence of NBT for 30 min at 37°C. The percentage of cells with NBT+ phagosomes is shown as the mean ± SD (n = 4 except for W207R/D289A, where n = 3). (C) COSphoxFcγR cells were transfected as in A for expression of YFP-tagged wild-type or mutant derivatives of p40phox as indicated or a YFP-tagged PX domain of p40phox and incubated with IgG–sheep RBCs or with IgG latex beads (*) without or with 50 nM wortmannin, followed by confocal microscopy. Individual phagosomes were scored for either the presence (black bars) or absence of YFP-p40phox or YFP-p40PX translocation. The number of phagosomes scored for each construct is also shown. Data was collected from two to four independent experiments.

To investigate the relationship between phagosome NADPH oxidase activity and translocation of p40phox, EYFP-tagged p40phox mutants were transiently expressed in COSphoxFcγR cells to examine their localization on IgG-RBC phagosomes. The results are summarized in Fig. 5 C, which also includes, for comparison, data for the EYFP-tagged PX domain of p40phox and wild-type EYFP-p40phox, as well as for EYFP-p40phox after phagocytosis of IgG latex beads in the absence or presence of wortmannin. Mutations in the PX domain (R58Q or R105A) substantially decreased the fraction of phagosomes with EYFP-p40phox, consistent with the importance of PI(3)P binding for p40phox localization to phagosomes. Mutations in the PB1 domain (D289A), either as a single mutation or in combination with a mutation in the SH3 domain, also resulted in a marked reduction in the fraction of p40phox-enriched phagosomes, supporting a role for heterodimerization of PB1 motifs in p40phox and p67phox in localizing p40phox to phagosome membranes. However, translocation of a p40phox derivative with an SH3 domain mutation (W207R) was similar to wild-type p40phox, although this mutation led to a decrease in NADPH oxidase–positive phagosomes, particularly in combination with the PB1 domain mutation (Fig. 5 B). This finding suggests that the p40phox SH3 domain plays a role in regulating activity of the assembled NADPH oxidase complex rather than in recruitment or maintenance of p40phox on phagosome membranes.

Phosphoinositide 3 (PI3) kinase activity is required for superoxide production during FcγR-induced phagocytosis in macrophages

Because an intact PI(3)P binding site in p40phox is required for activation of superoxide production in COSphoxFcγR phagosomes, we next examined whether inhibition of PI3 kinase activity during FcγR-induced phagocytosis would prevent NADPH oxidase activation in professional phagocytes. Class I and III PI3 kinases act sequentially to regulate phagosome engulfment and subsequent maturation (50). Class I PI3 kinases, which catalyze the formation of PI(3,4,5)P3 that is transiently present on forming phagosomes (40, 51, 52), are required for FcγR-mediated ingestion of large IgG-opsonized particles and appear to play roles in both fusion of intracellular membranes with the phagosome and contractile activity during phagosome closure (53–56). In contrast, PI(3)P appears in phagosomal membranes at around the time of closure. PI(3)P generation requires the activity of the class III PI3 kinase (also known as VPS34), and this phosphoinositide persists for many minutes in fully formed phagosomes (39, 40, 51).

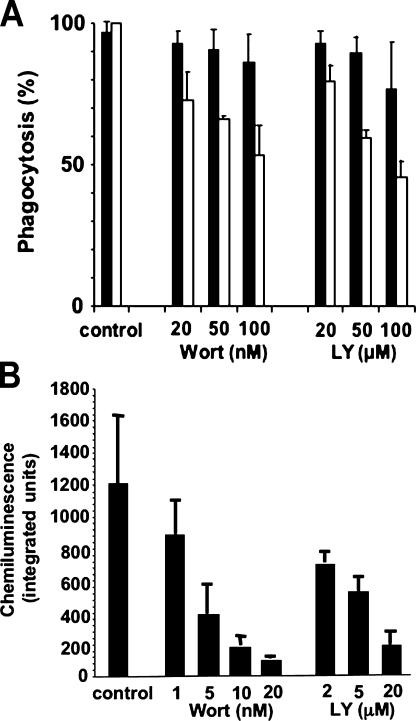

We examined the effects of the PI3 kinase inhibitors wortmannin and LY294002 on phagocytosis and NADPH oxidase activation in murine peritoneal exudate macrophages (PEMs) fed small (3.30-μm) IgG-opsonized latex beads because the ability to ingest small particles is less sensitive to PI3 kinase inhibitors compared with phagocytosis of large targets (55). The phagocytic index for 3.3-μm beads declined by only ∼50% in the presence of 100 nM wortmannin or 100 μM LY294002, with 75% of macrophages still capable of phagocytosis (Fig. 6 A). In contrast, NADPH oxidase activity during phagocytosis of IgG-opsonized beads was substantially reduced by even small amounts of wortmannin or LY294002, with an IC50 of ∼2 nM or 2 μM, respectively (Fig. 6 B). This IC50 is similar to that reported for the effect of wortmannin on oxidase activity in human and murine macrophages ingesting zymosan particles, where phagocytosis was also relatively preserved (57). Note that PI3 kinase inhibitors do not eliminate PMA-stimulated NADPH oxidase activation in COSphoxFcγ cells (not depicted) or neutrophils (58). These results indicate that PI3 kinase activity is important for NADPH oxidase activation during Fcγ receptor–mediated phagocytosis by professional phagocytes, independent of its role in regulating particle ingestion.

Figure 6.

Effects of PI3 kinase inhibitor on macrophage phagocytosis and NADPH oxidase activity elicited by IgG-opsonized latex beads. Murine PEMs were incubated with varying concentrations of wortmannin or LY294002 for 30 min at 37°C or with DMSO vehicle (control) before adding IgG-opsonized latex beads (3.3 μm). Data is the mean ± SD (n ≥ 3 experiments). (A) The percentage of macrophages with internalized beads (black bars) and the phagocytic index (white bars; data normalized as the percentage of the phagocytic index for vehicle-treated control macrophages, which was ∼400–600) are shown. (B) NADPH oxidase activity during phagocytosis of IgG beads, as measured by lucigenin-dependent chemiluminescence integrated over 60 min. Data is the mean ± SD (n ≥ 3 experiments). The background signal from gp91phox-null PEM samples run in parallel was 90.0 ± 27.8 and has been subtracted from the wild-type PEM signal.

DISCUSSION

The role of p40phox in the phagocyte NADPH oxidase has been enigmatic since it was discovered more than a decade ago as a 40-kD polypeptide that copurified in a 250-kD complex with p67phox and p47phox (9, 17, 18). The primary association of p40phox appears to be with p67phox via a high-affinity interaction involving their PB1 domains. The p40phox subunit is dispensable for high-level NADPH oxidase activity in cell-free assays and in whole cells, and both inhibitory and activating effects have been described (9, 28, 31–34). With the recent recognition that the PX domain of p40phox binds specifically to the phosphoinositide PI(3)P (27, 28), which is synthesized by class III PI3 kinase in newly forming phagosomes (39, 40), p40phox has been speculated to participate in phagocytosis-induced superoxide production. However, until now, direct evidence for this link was lacking. Here, we show that concomitant expression of p40phox is necessary and sufficient to activate superoxide production during phagocytosis in COS7 cells expressing the FcγIIA receptor along with the flavocytochrome b 558, p47phox, and p67phox components of the phagocyte NADPH oxidase. These observations are supported by and provide a mechanistic basis for neutrophil NADPH oxidase activation defects in mice with a targeted genetic deletion of p40phox, as reported in the accompanying article by Ellson et al. (59). In the current study, additional experiments using mutant derivatives of p40phox and pharmacological agents suggest that this subunit activates the NADPH oxidase by a network of interactions involving PI(3)P, p47phox, and p67phox.

Interactions between p40phox and PI(3)P appear to be essential for NADPH oxidase activation in the phagosome. FcγIIA receptor–stimulated NADPH oxidase activity was abrogated by point mutations in p40phox that disrupt PI(3)P binding. This is consistent with studies by Ellson et al. (28), in which a PX domain–deficient form of p40phox failed to augment NADPH oxidase activity in a semi-recombinant cell-free system containing PI(3)P that was otherwise markedly enhanced by wild-type p40phox. Similarly, studies by Brown et al. (21) showed that the isolated p40phox PX domain acted in a dominant-negative fashion to suppress ∼50% of the NADPH oxidase activity in a permeabilized neutrophil system stimulated by phorbol ester. Experiments using primary macrophages also support an important role of phosphoinositides for activation of the NADPH oxidase on the phagosome. We found that NADPH oxidase activation induced by macrophage phagocytosis of IgG beads was inhibited by PI3 kinase inhibitors to a much greater extent than was phagocytosis itself (for 3.3-μm beads, IC50 ≈ 2 nm wortmannin or 2 μM LY294002 vs. 100 nM wortmannin or 100 μM LY294002, respectively). These data extend the results of Baggiolini et al. (57), who studied murine and human phagocytes ingesting either unopsonized or serum-opsonized zymosan particles, which are taken up by the dectin receptor (60) or via β2 integrin and FcγR receptors (61), respectively. In addition to class III PI3 kinase–catalyzed formation of PI(3)P, class I PI3 kinases generate PI(3,4)P2 and PI(3,4,5)P3 early during phagocytosis (40). Although it is possible that they may also contribute to NADPH oxidase activation on the phagosome, these phosphoinositides are present only for a short time on the phagocytic cup and disappear upon phagosome closure (40, 52).

Additional studies established that the p40phox SH3 and PB1 domains are also critical for mediating FcγIIA receptor–induced NADPH oxidase activity on the phagosome. Interestingly, in contrast to disruption of the p40phox PI(3)P-binding pocket, mutation of either the SH3 or PB1 domain in p40phox reduced but did not eliminate the appearance of NADPH oxidase activity in phagosomes, and their simultaneous mutation was required to abrogate phagosome oxidant production. A p40phox–p67phox–p47phox complex has been isolated from resting neutrophils, although recent evidence suggests that the presence of p47phox may reflect a partially activated state (21). In a current model, p67phox is linked to both p40phox via heterodimerization of their PB1 domains and to p47phox via a tail-to-tail interaction of the p67phox C-terminal SH3 domain and the C-terminal PRR of p47phox (Fig. 1) (10, 11). The p40phox subunit also contains an SH3 domain whose only identified binding partner is also the C-terminal PRR of p47phox. The p47phox PRR exhibits an ∼20-fold lower affinity for the p40phox SH3 domain compared with the p67phox SH3 domain, as evaluated in vitro using derivative peptides and protein fragments (10, 11). However, these relative affinities may change in the assembled membrane complex, such that the p40phox participates in a dynamic series of interactions between p67phox and p47phox during NADPH oxidase activation on the phagosome.

A positive role for p40phox in NADPH oxidase activation in whole cells was also reported by Kuribayashi et al. (32), who used K562 leukemia cells expressing transgenic phox subunits, and by He et al. (33) in COSphox cells activated through a transgenic fMLP receptor (33). In fMLP-activated COSphox cells, p40phox enhanced NADPH oxidase activity by approximately twofold (33). Expression of p40phox in the K562 model also increased superoxide production by two- to threefold in response to PMA and had an even greater effect for activation by a muscarinic receptor peptide that acts via Gi (32). In K562 cells, disruption of the p40phox–p67phox interaction by reciprocal PB1 domain mutations in either p40phox or p67phox was sufficient to prevent p40phox translocation and enhancement of superoxide production (32). In contrast, we observed only partial reduction of FcγIIA receptor–stimulated NADPH oxidase activation using a PB1 domain mutant of p40phox, unless the p40phox SH3 domain was also disrupted.

The molecular basis by which p40phox activates superoxide production will require further investigation. It is possible that p40phox facilitates or stabilizes recruitment of p47phox and p67phox to the phagosome. However, in intact cells, the initial translocation of cytosolic phox components to the membrane upon cellular activation is driven by the p47phox adaptor protein, as p67phox and p40phox fail to translocate in chronic granulomatous disease patients lacking p47phox (22, 62). Membrane localization of p40phox in activated K562 cells (32) is also dependent on its interaction with p67phox and, indirectly, p47phox, and EYFP-tagged p40phox does not translocate to phagosomes in COS7 cells expressing the FcγIIA receptor, but not the other phox subunits (unpublished data). Thus, p40phox may act primarily as a PI(3)P-dependent tether that optimally positions the p40phox–p67phox–p47phox complex and the flavocytochrome in phagosome membranes to activate the superoxide production. Studies in which PI(3)P (21, 28) and p40phox (28) markedly enhance superoxide production in semi-recombinant systems support a role for PI(3)P-bound p40phox in directly regulating activity of the assembled NADPH oxidase complex. In addition, the analysis of p40phox mutants in our study suggests that the SH3 domain of p40phox also participates in stimulating NADPH oxidase activity on phagosomes.

In phagocytic leukocytes, the role of p40phox in activating the NADPH oxidase in the phagosome may be selective, based on studies described in the accompanying article by Ellson et al. (59), who saw a substantial reduction in NADPH oxidase activity with phagocytosis of IgG-coated latex beads or of Staphylococcus aureus, but little or no effect upon phagocytosis of zymosan particles. Signaling events initiated by phagocytosis are complex and incompletely understood, and the relative roles of different downstream pathways are likely to vary depending on the phagocytic receptor and on the type and size of the target particle (46, 47).

In conclusion, this study identifies a positive role for p40phox in coupling NADPH oxidase activation to FcγIIA receptor–induced phagocytosis and establishes a critical requirement for the p40phox PI(3)P-binding domain in superoxide production. Moreover, although the functional importance of the p40phox PB1 domain in mediating binding to p67phox was previously recognized, this study suggests that the SH3 domain in p40phox also contributes to NADPH oxidase activation during phagocytosis. The COSphox model should be a useful system to analyze contributions of other signaling events to NADPH oxidase activation during phagocytosis and to elucidate their underlying mechanisms.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Chemicals were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich unless otherwise stated. PBS, pH 7.2, blasticidin, penicillin/streptomycin, neomycin, trypsin/EDTA, Lipofectamine reagent, DMEM with low glucose, and RPMI 1640 were purchased from Invitrogen Life Technologies, hygromycin was from EMD Biosciences, puromycin was from BD Clontech, and bovine growth serum and FCS were from HyClone Laboratory.

Expression plasmids.

The human p40phox cDNA (provided by S. Chanock, National Institutes of Health [NIH], Bethesda, MD) was cloned into the EcoRI site of pRK5 (BD Biosciences) (33) and pcDNA6/myc-HisC (Invitrogen Life Technologies) to generate p40pRK5 and p40-pcDNA6/myc-HisC, where the myc tag is not in frame with the p40phox cDNA. p40phox-EYFP and p40PX-EYFP (27) plasmids for expression of fluorescently tagged full-length p40phox or its PX domain, respectively, were prepared using pEYFP-C1 (BD Clontech). The YFP-tagged p40phox cDNA was also subcloned into the HpaI and EcoRI sites of pMSCVpuro (BD Clontech), and the phosphoglycerate kinase puromycin-resistance gene cassette was removed by digesting with EcoRI and ClaI, blunting, and religating. Site-directed mutagenesis of p40phox was performed in p40pRK5 using the QuikChange Site-Directed Mutagenesis kit (Stratagene) and confirmed by sequencing. To generate YFP-tagged p40phox mutants, the pEYFP-C1 plasmid containing the p40phox cDNA was digested with BamHI (which cuts at an internal site in the p40phox cDNA just 5′ to the codon for R58) and XmaI (a site in the 3′ polylinker). The excised wild-type p40phox cDNA fragment was replaced with the corresponding BamHI–XmaI fragment from p40pRK5 plasmids harboring specific p40phox mutations. The MFG-FcγRIIa vector was constructed by inserting the human FcγRIIa cDNA (provided by B. Seed, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA) into the NcoI site of the MFG-S retroviral vector (provided by H. Malech, NIH, Bethesda, MD).

Cell lines.

COS7 lines were grown in low-glucose DMEM with 10% bovine growth serum at 37°C under 5% CO2. Media for COSphox cell lines (63) also included 0.2 mg/ml hygromycin, 0.8 mg/ml neomycin, and 1 μg/ml puromycin. Lipofectamine reagent was used for transfection, with a transient transfection efficiency of ∼40% as monitored using pIRES2-EGFP (BD Clontech). Lines with stable expression of the FcγRIIa receptor were generated by retroviral transduction of COS7 and COSphox cells with VSVG-pseudotyped MFG-FcγRIIa packaged using the Pantropic Retroviral Expression System (BD Clontech). Transduced cells were stained with an FITC-conjugated CD32 antibody (BD Biosciences) and sorted for FcγRIIa expression using a FACSVantage (BD Biosciences). The resulting COS7-FcγR and COSphoxFcγR lines were grown as described above. To generate COS7 lines with stable expression of p40phox, COS7-FcγR and COSphoxFcγR cells were transfected with p40-pcDNA6/myc-HisC, followed by cloning in the presence of 10 μg/ml blasticidin. A clone with the highest expression of p40phox was selected from each group and carried in 30–60 μg blasticidin to maintain stable p40phox expression.

Human PLB-985 myelomonocytic cells were cultured as described previously (64). PLB-985 cells with stable expression of EYFP-p40phox were generated by retroviral transduction with VSVG-pseudotyped MSCV-EYFP-p40phox packaged using the Pantropic Retroviral Expression System (BD Clontech). After transduction, 89% of the cells were EYFP+. For granulocytic differentiation, PLB-985-EYFP-p40phox cells were cultured in 0.5% dimethylformamide for 5 d.

Isolation of murine macrophages.

Sodium periodate–elicited murine PEMs were prepared from 8–10-wk-old male or female C57/BL6J mice (The Jackson Laboratory) as described previously (65, 66). In experiments where macrophage NADPH oxidase activity was measured by chemiluminescence, PEMs were also prepared from C57/BL6J mice that have a targeted deletion in the gp91phox gene and lack NADPH oxidase activity (67). PEMs were cultured on gelatin-coated coverslips (Fisher Scientific) for 24–72 h before functional assays. For murine bone marrow–derived macrophages, a protocol using L cell–conditioned medium was used (68).

Analysis of protein expression.

COS7 lines and human peripheral blood leukocytes were stained with either FITC-conjugated CD32 antibody for FcγIIA or an IgG2bκ isotype control and analyzed using a FACSCalibur (BD Biosciences) as described previously (66). Monocytes and neutrophils were identified based on forward-side scattering properties. Cell lysates were prepared from COS7 cell lines and from human neutrophils for sodium dodecyl sulfate-PAGE (SDS-PAGE) and immunoblotting using ECL detection (GE Healthcare) as previously described (30). Human neutrophils were isolated from heparinized whole blood using Polymorphprep (Axis-Shield PoC AS). A rabbit polyclonal antibody against p40phox and a mouse mAb against Rac were from Upstate Biotechnology, and mAbs against p67phox and p47phox were from BD Biosciences.

Phagocytosis and NADPH oxidase activity determinations.

IgG-coated RBCs (IgG-RBC) were freshly prepared as described previously using sheep RBCs and rabbit anti–sheep RBC IgG (MP Biomedicals) (66). Opsonization of latex beads (1.98 or 3.30 μm; Bangs Laboratories, Inc.) with human IgG was also performed as described previously (69). Opsonized targets were resuspended in DMEM or RPMI.

Phagocytosis of IgG-RBCs was performed essentially as described previously (66). Derivative COS7 cell lines were split and replated at a concentration of 3.0 × 104 cells/well in eight-well chamber slides (Nalge Nunc International). In experiments where p40phox was transiently expressed, cells were replated into chamber slides 1 d after transfection. 2 d after replating, slides were placed on ice and washed with PBS. IgG-RBCs in DMEM containing 20% of a saturated NBT solution were added at a 100:1 ratio of IgG-RBCs to cells. Cells were then either incubated at 37°C for 30 min or, for synchronized phagocytosis, first centrifuged for 5 min at 800 rpm at 18°C before replacement of medium with prewarmed DMEM containing 20% NBT. Non-internalized RBCs were lysed by incubating with ddH2O for 1 min. Slides were air dried, fixed with methanol, and stained with 0.2% safranin before microscopic examination to assess NBT reduction by superoxide to dark purple formazan deposits (70). At least 200 cells were scored for each variable. In some experiments, duplicate wells were processed in the absence of NBT and stained with Diff-Quik (Dade Behring Inc.) to determine the phagocytic index as the number of IgG-RBCs ingested per 100 cells. In some experiments, COS7 derivatives were activated with 400 ng/ml phorbol myristate acetate and NADPH oxidase activity was assayed by NBT staining or by cytochrome c reduction (30).

NADPH oxidase activity was also measured using zymosan opsonized with Fc OxyBURST Green (Invitrogen), where dichlorodihydrofluorescein (H2DCF) is covalently linked to BSA and then complexed with purified rabbit polyclonal anti-BSA antibodies (43). Zymosan A was opsonized for 60 min at room temperature with Fc OxyBURST Green in PBS. After washing three times with PBS, Fc OxyBURST Green–opsonized zymosan was resuspended in PBSG (PBS plus 0.5 mM MgCl2, 0.9 mM CaCl2, and 7.5 mM dextrose) (30). Prewarmed labeled particles (50 per cell) were added to derivative COS7 cell lines, plated the previous day at 3 × 104 per well in eight-well chamber slides. Cells were incubated at 37°C for 30 min. Phagocytosis was terminated by putting the cells on ice. Cells were removed from the wells with trypsin/EDTA and analyzed immediately by flow cytometry (FACSCalibur; Becton Dickinson). All measurements were performed with the instrument excitation wavelength set at 488 nm and emission wavelength set at 530 nm. In some experiments, trypan blue was added just before flow cytometry, which quenches oxidized dye that might be bound extracellularly, with similar results.

Phagocytosis of IgG-opsonized latex beads by murine macrophages was performed as described previously (69), with minor modifications. PEMs on 12-mm gelatin-coated glass coverslips were pretreated 30 min at 37°C with phosphatidylinositol (PI) 3 kinase inhibitors at 20, 50, or 100 nM for wortmannin and 20, 50, or 100 μM for LY294002, or with DMEM containing DMSO vehicle alone. Medium was then replaced with prewarmed DMEM containing the same concentration of inhibitors, or DMSO alone, and IgG-opsonized 3.3-μm latex beads (3:1 beads per cell). After centrifugation (800 rpm at 18°C for 5 min), plates were incubated at 37°C for 30 min and washed with ice-cold PBS, and external beads were stained with Cy3-conjugated anti–human IgG (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories) before fixation with 4% paraformaldehyde and staining with 1% methylene blue. Macrophage-associated latex beads were counted using bright field microscopy, and external beads were identified using fluorescence to determine the fraction of cells undergoing phagocytosis and the phagocytic index.

NADPH oxidase activity in PEM-ingesting 3.3-μm beads was monitored by a lucigenin chemiluminescence assay (71). Wild-type and gp91phox-null PEMs were plated at 5 × 105 cells per well into 96-well flat-bottom tissue culture–treated plates (Corning Inc.) for 24 h. Before the addition of IgG latex beads, some wells were pretreated for 30 min at 37°C with 1–20 nM wortmannin, 2–20 μM LY294002, or PBSG containing DMSO vehicle alone. IgG latex beads in PBSG with 12.5 μM lucigenin were added (two beads per cell) with the same concentration of inhibitors. Cells were then incubated at 37°C for 60 min in an Lmax microplate luminometer (Molecular Devices). The relative amount of superoxide produced over 60 min was determined by integrating the chemiluminescence unit signals using SoftMax PRO software (Molecular Devices). The background signal from gp91phox-null PEM samples run in parallel, which did not change with IgG latex bead stimulation, was subtracted from the wild-type PEM signal.

Confocal microscopy.

COSphoxFcγR cells were transfected with p40PX-EYFP, p40phox-EYFP, or mutant derivatives of p40phox-EYFP and plated onto gelatin-coated coverslips. 2 d after transfection, cells were incubated with either rabbit IgG–coated RBCs or human IgG–coated 1.98-μm latex beads labeled with either goat anti–rabbit IgG or goat anti–human IgG conjugated to Alexa Fluor 555 (Molecular Probes) for 30 min at room temperature. In some experiments, cells were preincubated with 50 nM wortmannin for 15 min before adding IgG beads. After phagocytosis, the plates were put on ice for 2 min and rinsed twice for 5 min with cold PBS/1% BSA. Uningested IgG beads were stained with Alexa Fluor 633 goat anti–human IgG (Invitrogen). Non-internalized IgG-RBCs were lysed by incubation with water for 4 min. Cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS at room temperature for 10 min. Coverslips were mounted in DABCO, sealed and stored at 4°C overnight, and imaged on a Zeiss LSM-510 confocal microscope system with a 100× 1.4 N.A. oil-immersion objective. Metamorph 6.0 (Molecular Devices) was used to create projections (through-focus images) from three to eight 0.35-μm sections covering the middle of the cell. For confocal microscopy of PLB-985 granulocytes expressing YFP-tagged p40phox, cells were deposited onto polylysine-coated coverslips by centrifugation (800 rpm for 2 min) on day 5 of dimethylformamide differentiation and cultured overnight. 1.98-μm IgG latex beads in RPMI were then deposited onto cells by centrifugation (800 rpm for 2 min), and cells were incubated at 37°C for 30 min. In some experiments, cells were preincubated with 50 nM wortmannin for 30 min before adding IgG beads. Fixation of cells, image acquisition, and analysis were as described above for COS7 derivatives.

Acknowledgments

We thank Shari Upchurch for assistance with manuscript preparation, Ken Dunn for helpful discussions regarding microscopy, and Lee-Ann Allen for advice on measurement of NADPH oxidase activity during phagocytosis.

This work was supported by NIH grants R01 HL45635 (to M.C. Dinauer) and P01 HL069974 (to M.C. Dinauer and S. Atkinson), R01 GM98059 (to M.B. Yaffe), the Indiana University Cancer Center Flow Cytometry and Imaging Cores P30 CA082709, the Canadian Institutes for Health Research (to S. Grinstein), and the Riley Children's Foundation (M.C. Dinauer).

The authors have no conflicting financial interests.

Abbreviations used: EYFP, enhanced yellow fluorescence protein; NADPH, reduced nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate; NBT, nitroblue tetrazolium; PB1, phagocyte oxidase and Bem1p; PEM, peritoneal exudate macrophage; PI3, phosphoinositide 3; PI(3)P, phosphatidylinositol-3-phosphate; PRR, proline-rich region.

References

- 1.Dinauer, M. 2003. The phagocyte system and disorders of granulopoiesis and granulocyte function. In Nathan and Oski's Hematology of Infancy and Childhood. D. Nathan, S. Orkin, D. Ginsburg, and A. Look, editors. W.B. Saunders Company, Philadelphia. 923–1010.

- 2.Quinn, M.T., and K.A. Gauss. 2004. Structure and regulation of the neutrophil respiratory burst oxidase: comparison with nonphagocyte oxidases. J. Leukoc. Biol. 76:760–781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Groemping, Y., and K. Rittinger. 2005. Activation and assembly of the NADPH oxidase: a structural perspective. Biochem. J. 386:401–416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Groemping, Y., K. Lapouge, S.J. Smerdon, and K. Rittinger. 2003. Molecular basis of phosphorylation-induced activation of the NADPH oxidase. Cell. 113:343–355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Biberstine-Kinkade, K.J., L. Yu, and M.C. Dinauer. 1999. Mutagenesis of an arginine- and lysine-rich domain in the gp91phox subunit of the phagocyte NADPH-oxidase flavocytochrome b558. J. Biol. Chem. 274:10451–10457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.DeLeo, F., L. Yu, J. Burritt, L. Loetterle, C. Bond, A. Jesaitis, and M. Quinn. 1995. Mapping sites of interaction of p47phox and flavocytochrome b with a random-sequence peptide phage display library. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 92:7110–7114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cross, A.R., R.W. Erickson, and J.T. Curnutte. 1999. Simultaneous presence of p47phox and flavocytochrome b245 are required for the activation of NADPH oxidase by anionic amphiphiles. Evidence for an intermediate state of oxidase activation. J. Biol. Chem. 274:15519–15525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ito, T., R. Nakamura, H. Sumimoto, K. Takeshige, and Y. Sakaki. 1996. An SH3 domain-mediated interaction between the phagocyte NADPH oxidase factors p40phox and p47phox. FEBS Lett. 385:229–232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tsunawaki, S., S. Kagara, K. Yoshikawa, L. Yoshida, T. Kuratsuji, and H. Namiki. 1996. Involvement of p40phox in activation of phagocyte NADPH oxidase through association of its carboxyl-terminal, but not its amino-terminal, with p67phox. J. Exp. Med. 184:893–902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lapouge, K., S.J. Smith, Y. Groemping, and K. Rittinger. 2002. Architecture of the p40-p47-p67phox complex in the resting state of the NADPH oxidase. A central role for p67phox. J. Biol. Chem. 277:10121–10128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Massenet, C., S. Chenavas, C. Cohen-Addad, M.C. Dagher, G. Brandolin, E. Pebay-Peyroula, and F. Fieschi. 2005. Effects of p47phox C terminus phosphorylations on binding interactions with p40phox and p67phox. Structural and functional comparison of p40phox and p67phox SH3 domains. J. Biol. Chem. 280:13752–13761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nisimoto, Y., S. Motalebi, C. Han, and J. Lambeth. 1999. The p67phox activation domain regulates electron flow from NADPH to flavin in flavocytochrome b558. J. Biol. Chem. 274:22999–23005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Diekmann, D., A. Abo, C. Johnston, A. Segal, and A. Hall. 1994. Interaction of Rac with p67phox and regulation of phagocytic NADPH oxidase activity. Science. 265:531–534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Koga, H., H. Terasawa, H. Nunoi, K. Takeshige, F. Inagaki, and H. Sumimoto. 1999. Tetratricopeptide repeat (TPR) motifs of p67phox participate in interaction with the small GTPase Rac and activation of the phagocyte NADPH oxidase. J. Biol. Chem. 274:25051–25060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Diebold, B., and G. Bokoch. 2001. Molecular basis for Rac2 regulation of phagocyte NADPH oxidase. Nat. Immunol. 2:211–215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dinauer, M. 2003. Regulation of neutrophil function by Rac GTPases. Curr. Opin. Hematol. 10:8–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wientjes, F., J. Hsuan, N. Totty, and A. Segal. 1993. p40phox, a third cytosolic component of the activation complex of the NADPH oxidase to contain src homology 3 domains. Biochem. J. 296:557–561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Someya, A., I. Nagaoka, and T. Yamashita. 1993. Purification of the 260 kDa cytosolic complex involved in the superoxide production of guinea pig neutrophils. FEBS Lett. 330:215–218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wilson, M.I., D.J. Gill, O. Perisic, M.T. Quinn, and R.L. Williams. 2003. PB1 domain-mediated heterodimerization in NADPH oxidase and signaling complexes of atypical protein kinase C with Par6 and p62. Mol. Cell. 12:39–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tsunawaki, S., M. Hiroyuki, H. Namiki, and T. Kuratsuji. 1994. NADPH-binding component of the respiratory burst oxidase system: studies using neutrophil membranes from patients with chronic granulomatous disease lacking the β-subunit of cytochrome b558. J. Exp. Med. 179:291–297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brown, G.E., M.Q. Stewart, H. Liu, V.L. Ha, and M.B. Yaffe. 2003. A novel assay system implicates PtdIns(3,4)P(2), PtdIns(3)P, and PKC delta in intracellular production of reactive oxygen species by the NADPH oxidase. Mol. Cell. 11:35–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dusi, S., M. Donini, and F. Rossi. 1996. Mechanisms of NADPH oxidase activation: translocation of p40phox, Rac1 and Rac2 from the cytosol to the membranes in human neutrophils lacking p47phox or p67phox. Biochem. J. 314:409–412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wientjes, F.B., G. Panayotou, E. Reeves, and A.W. Segal. 1996. Interactions between cytosolic components of the NADPH oxidase: p40phox interacts with both p67phox and p47phox. Biochem. J. 317:919–924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fuchs, A., M. Dagher, and P. Vignais. 1995. Mapping the domains of interaction of p40phox with both p47phox and p67phox of the neutrophil oxidase complex using the two-hybrid system. J. Biol. Chem. 270:5695–5697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yamamoto, S., and M. Nakamura. 1996. Calnexin: its molecular cloning and expression in the liver of the frog, Rana rugosa. FEBS Lett. 387:27–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Grizot, S., N. Grandvaux, F. Fieschi, J. Faure, C. Massenet, J.P. Andrieu, A. Fuchs, P.V. Vignais, P.A. Timmins, M.C. Dagher, and E. Pebay-Peyroula. 2001. Small angle neutron scattering and gel filtration analyses of neutrophil NADPH oxidase cytosolic factors highlight the role of the C-terminal end of p47phox in the association with p40phox. Biochemistry. 40:3127–3133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kanai, F., L. Hui, S. Field, H. Akbary, T. Matsuo, G. Brown, L. Cantley, and M. Yaffe. 2001. The PX domains of p47phox and p40phox bind to lipid products of PI(3)K. Nat. Cell Biol. 3:675–678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ellson, C., S. Gobert-Gosse, K. Anderson, K. Davidson, H. Erdjument-Bromage, P. Temps, J. Thuring, M. Cooper, Z. Lim, A. Holmes, et al. 2001. Ptdlns(3)P regulates the neutrophil oxidase complex by binding to the PX domain of p40phox. Nat. Cell Biol. 3:679–682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.De Mendez, I., and T. Leto. 1995. Functional reconstitution of the phagocyte NADPH oxidase by transfection of its multiple components in a heterologous system. Blood. 85:1104–1110. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Price, M.O., L.C. McPhail, J.D. Lambeth, C.H. Han, U.G. Knaus, and M.C. Dinauer. 2002. Creation of a genetic system for analysis of the phagocyte respiratory burst: high-level reconstitution of the NADPH oxidase in a nonhematopoietic system. Blood. 99:2653–2661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cross, A. 2000. p40phox participates in the activation of NADPH oxidase by increasing the affinity of p47phox for flavocytochrome b558. Biochem. J. 349:113–117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kuribayashi, F., H. Nunoi, K. Wakamatsu, S. Tsunawaki, K. Sato, T. Ito, and H. Sumimoto. 2002. The adaptor protein p40phox as a positive regulator of the superoxide-producing phagocyte oxidase. EMBO J. 21:6312–6320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.He, R., M. Nanamori, H. Sang, H. Yin, M.C. Dinauer, and R.D. Ye. 2004. Reconstitution of chemotactic peptide-induced nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (reduced) oxidase activation in transgenic COSphox cells. J. Immunol. 173:7462–7470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Vergnaud, S., M.H. Paclet, J. El Benna, M.A. Pocidalo, and F. Morel. 2000. Complementation of NADPH oxidase in p67phox-deficient CGD patients p67phox/p40phox interaction. Eur. J. Biochem. 267:1059–1067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Downey, G.P., R.J. Botelho, J.R. Butler, Y. Moltyaner, P. Chien, A.D. Schreiber, and S. Grinstein. 1999. Phagosomal maturation, acidification, and inhibition of bacterial growth in nonphagocytic cells transfected with FcγRIIA receptors. J. Biol. Chem. 274:28436–28444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Indik, Z.K., J.G. Park, S. Hunter, and A.D. Schreiber. 1995. The molecular dissection of Fcγ receptor mediated phagocytosis. Blood. 86:4389–4399. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lowry, M.B., A.M. Duchemin, J.M. Robinson, and C.L. Anderson. 1998. Functional separation of pseudopod extension and particle internalization during Fcγ receptor–mediated phagocytosis. J. Exp. Med. 187:161–176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Indik, Z., C. Kelly, P. Chien, A.I. Levinson, and A.D. Schreiber. 1991. Human FcγRII, in the absence of other Fcγ receptors, mediates a phagocytic signal. J. Clin. Invest. 88:1766–1771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ellson, C.D., K.E. Anderson, G. Morgan, E.R. Chilvers, P. Lipp, L.R. Stephens, and P.T. Hawkins. 2001. Phosphatidylinositol 3-phosphate is generated in phagosomal membranes. Curr. Biol. 11:1631–1635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vieira, O.V., R.J. Botelho, L. Rameh, S.M. Brachmann, T. Matsuo, H.W. Davidson, A. Schreiber, J.M. Backer, L.C. Cantley, and S. Grinstein. 2001. Distinct roles of class I and class III phosphatidylinositol 3-kinases in phagosome formation and maturation. J. Cell Biol. 155:19–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mizuki, K., K. Kadomatsu, K. Hata, T. Ito, Q.F. An, Y. Kage, Y. Fukumaki, Y. Sakaki, K. Takeshige, and H. Sumimoto. 1998. Functional modules and expression of mouse p40phox and p67phox, SH3-domain-containing proteins involved in the phagoctye NADPH oxidase complex. Eur. J. Biochem. 251:573–582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhan, S., N. Vazquez, S. Zhan, F. Wientjes, M. Budarf, E. Schrock, T. Ried, E. Green, and S. Chanock. 1996. Genomic structure, chromosomal localization, start of transcription, and tissue expression of the human p40phox, a new component of the nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate-oxidase complex. Blood. 88:2714–2721. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ryan, T.C., G.J. Weil, P.E. Newburger, R. Haugland, and E.R. Simons. 1990. Measurement of superoxide release in the phagovacuoles of immune complex-stimulated human neutrophils. J. Immunol. Methods. 130:223–233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Robinson, J.M., T. Ohira, and J.A. Badwey. 2004. Regulation of the NADPH-oxidase complex of phagocytic leukocytes. Recent insights from structural biology, molecular genetics, and microscopy. Histochem. Cell Biol. 122:293–304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ueyama, T., M.R. Lennartz, Y. Noda, T. Kobayashi, Y. Shirai, K. Rikitake, T. Yamasaki, S. Hayashi, N. Sakai, H. Seguchi, et al. 2004. Superoxide production at phagosomal cup/phagosome through βI protein kinase C during FcγR-mediated phagocytosis in microglia. J. Immunol. 173:4582–4589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Griffiths, G. 2004. On phagosome individuality and membrane signaling networks. Trends Cell Biol. 14:343–351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Swanson, J.A., and A.D. Hoppe. 2004. The coordination of signaling during Fc receptor-mediated phagocytosis. J. Leukoc. Biol. 76:1093–1103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Underhill, D.M., E. Rossnagle, C.A. Lowell, and R.M. Simmons. 2005. Dectin-1 activates Syk tyrosine kinase in a dynamic subset of macrophages for reactive oxygen production. Blood. 106:2543–2550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bravo, J., D. Karathanassis, C.M. Pacold, M.E. Pacold, C.D. Ellson, K.E. Anderson, P.J. Butler, I. Lavenir, O. Perisic, P.T. Hawkins, et al. 2001. The crystal structure of the PX domain from p40phox bound to phosphatidylinositol 3-phosphate. Mol. Cell. 8:829–839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Vieira, O.V., R.J. Botelho, and S. Grinstein. 2002. Phagosome maturation: aging gracefully. Biochem. J. 366:689–704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Henry, R.M., A.D. Hoppe, N. Joshi, and J.A. Swanson. 2004. The uniformity of phagosome maturation in macrophages. J. Cell Biol. 164:185–194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Marshall, J.G., J.W. Booth, V. Stambolic, T. Mak, T. Balla, A.D. Schreiber, T. Meyer, and S. Grinstein. 2001. Restricted accumulation of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase products in a plasmalemmal subdomain during Fcγ receptor–mediated phagocytosis. J. Cell Biol. 153:1369–1380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Araki, N., M.T. Johnson, and J.A. Swanson. 1996. A role for phosphoinositide 3-kinase in the completion of macropinocytosis and phagocytosis by macrophages. J. Cell Biol. 135:1249–1260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Cox, D., J.S. Berg, M. Cammer, J.O. Chinegwundoh, B.M. Dale, R.E. Cheney, and S. Greenberg. 2002. Myosin X is a downstream effector of PI(3)K during phagocytosis. Nat. Cell Biol. 4:469–477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Cox, D., C.C. Tseng, G. Bjekic, and S. Greenberg. 1999. A requirement for phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase in pseudopod extension. J. Biol. Chem. 274:1240–1247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Niedergang, F., E. Colucci-Guyon, T. Dubois, G. Raposo, and P. Chavrier. 2003. ADP ribosylation factor 6 is activated and controls membrane delivery during phagocytosis in macrophages. J. Cell Biol. 161:1143–1150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Baggiolini, M., B. Dewald, J. Schnyder, W. Ruch, P.H. Cooper, and T.G. Payne. 1987. Inhibition of the phagocytosis-induced respiratory burst by the fungal metabolite wortmannin and some analogues. Exp. Cell Res. 169:408–418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Karlsson, A., J.B. Nixon, and L.C. McPhail. 2000. Phorbol myristate acetate induces neutrophil NADPH-oxidase activity by two separate signal transduction pathways: dependent or independent of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase. J. Leukoc. Biol. 67:396–404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ellson, C.D., K. Davidson, G. John Ferguson, R. O'Connor, L.R. Stephens, and P.T. Hawkins. 2006. Neutrophils from p40phox−/− mice exhibit severe defects in NADPH oxidase regulation and oxidant-dependent bacterial killing. J. Exp. Med. 203:1927–1937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Brown, G.D., J. Herre, D.L. Williams, J.A. Willment, A.S. Marshall, and S. Gordon. 2003. Dectin-1 mediates the biological effects of β-glucans. J. Exp. Med. 197:1119–1124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lowell, C.A., and G. Berton. 1999. Integrin signal transduction in myeloid leukocytes. J. Leukoc. Biol. 65:313–320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Heyworth, P.G., J.T. Curnutte, W.M. Nauseef, B.D. Volpp, D.W. Pearson, H. Rosen, and R.A. Clark. 1991. Neutrophil nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate oxidase assembly. J. Clin. Invest. 87:352–356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Price, M.O., S.J. Atkinson, U.G. Knaus, and M.C. Dinauer. 2002. Rac activation induces NADPH oxidase activity in transgenic COSphox cells and level of superoxide production is exchange factor-dependent. J. Biol. Chem. 277:19220–19228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Zhen, L., A. King, Y. Xiao, S. Chanock, S. Orkin, and M. Dinauer. 1993. Gene targeting of X-linked chronic granulomatous disease locus in a human myeloid leukemia cell line and rescue by expression of recombinant gp91phox. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 90:9832–9836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.De Groote, M.A., U.A. Ochsner, M.U. Shiloh, C. Nathan, J.M. McCord, M.C. Dinauer, S.J. Libby, A. Vazquez-Torres, Y. Xu, and F.C. Fang. 1997. Periplasmic superoxide dismutase protects Salmonella from products of phagocyte NADPH-oxidase and nitric oxide synthase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 94:13997–14001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Yamauchi, A., C. Kim, S. Li, C.C. Marchal, J. Towe, S.J. Atkinson, and M.C. Dinauer. 2004. Rac2-deficient murine macrophages have selective defects in superoxide production and phagocytosis of opsonized particles. J. Immunol. 173:5971–5979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Pollock, J., D. Williams, M. Gifford, L. Li, X. Du, J. Fisherman, S. Orkin, C. Doerschuk, and M. Dinauer. 1995. Mouse model of X-linked chronic granulomatous disease, an inherited defect in phagocyte superoxide production. Nat. Genet. 9:202–209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Mold, C., H.D. Gresham, and T.W. Du Clos. 2001. Serum amyloid P component and C-reactive protein mediate phagocytosis through murine FcγRs. J. Immunol. 166:1200–1205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Coppolino, M.G., R. Dierckman, J. Loijens, R.F. Collins, M. Pouladi, J. Jongstra-Bilen, A.D. Schreiber, W.S. Trimble, R. Anderson, and S. Grinstein. 2002. Inhibition of phosphatidylinositol-4-phosphate 5-kinase Iα impairs localized actin remodeling and suppresses phagocytosis. J. Biol. Chem. 277:43849–43857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Gallois, A., J. Klein, L. Allen, B. Jones, and W. Nauseef. 2001. Salmonella pathogenicity island 2-encoded type III secretion system mediates exclusion of NADPH oxidase assembly from the phagosomal membrane. J. Immunol. 166:5741–5748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Vazquez-Torres, A., Y. Xu, J. Jones-Carson, D.W. Holden, S.M. Lucia, M.C. Dinauer, P. Mastroeni, and F.C. Fang. 2000. Salmonella pathogenicity island 2-dependent evasion of the phagocyte NADPH oxidase. Science. 287:1655–1658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]