Abstract

Primary simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV) infections of rhesus macaques result in the dramatic depletion of CD4+ CCR5+ effector–memory T (TEM) cells from extra-lymphoid effector sites, but in most infections, an increased rate of CD4+ memory T cell proliferation appears to prevent collapse of effector site CD4+ TEM cell populations and acute-phase AIDS. Eventually, persistent SIV replication results in chronic-phase AIDS, but the responsible mechanisms remain controversial. Here, we demonstrate that in the chronic phase of progressive SIV infection, effector site CD4+ TEM cell populations manifest a slow, continuous decline, and that the degree of this depletion remains a highly significant correlate of late-onset AIDS. We further show that due to persistent immune activation, effector site CD4+ TEM cells are predominantly short-lived, and that their homeostasis is strikingly dependent on the production of new CD4+ TEM cells from central–memory T (TCM) cell precursors. The instability of effector site CD4+ TEM cell populations over time was not explained by increasing destruction of these cells, but rather was attributable to progressive reduction in their production, secondary to decreasing numbers of CCR5− CD4+ TCM cells. These data suggest that although CD4+ TEM cell depletion is a proximate mechanism of immunodeficiency, the tempo of this depletion and the timing of disease onset are largely determined by destruction, failing production, and gradual decline of CD4+ TCM cells.

The clinical manifestations of HIV infection typically ensue years after primary infection, despite continuous, often very high levels of viral replication (1–3). Although viral replication clearly drives the development of overt disease (1, 3, 4), the slow tempo of progression implies that host mechanisms must participate in the pathogenic sequence. Over years of investigation, a wide variety of pathogenic mechanisms have been proposed to play a role in AIDS pathogenesis in humans and AIDS-susceptible Asian macaques, including direct viral cytopathogenicity on CD4+ T cells and/or other target cells, indirect effects of infection such as persistent immune “hyperactivation,” and other forms of T cell or accessory cell dysregulation (1, 5–12), but the degree to which these various mechanisms “connect” HIV or simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV) replication to immunodeficiency, as well as their interaction and regulation, remains poorly defined.

Primary CXCR4- or dual-tropic SIV/HIV hybrid virus (SHIV) infection can induce pan-CD4+ T cell depletion and early immune deficiency in rhesus macaques (RMs), suggesting that acute, massive destruction of CD4+ T cells can directly lead to AIDS (13, 14). However, pan-CD4+ T cell depletion is unusual for typical CCR5-tropic SIV infection and is clearly not required for AIDS to develop (15, 16). The CCR5 coreceptor is selectively expressed on (CCR7−) effector site (or effector site–seeking) effector–memory T (TEM) cells (9, 17, 18), and in keeping with this, CCR5-tropic HIV/SIV infection dramatically depletes extra-lymphoid effector sites of their CD4+ TEM cell complement during acute infection (12, 19–23). In most infected monkeys and humans, this acute phase depletion does not result in overt immunodeficiency because in contrast to the pan-CD4+ T cell-depleting SHIVs, CCR5-tropic viruses leave a substantial CD4+ central–memory T (TCM) cell population intact, and the CD4+ TEM cell depletion is accompanied by increased proliferation of these spared CD4+ memory T cells that continuously provides an influx of new CD4+ TEM cells into extra-lymphoid effector sites (15, 23). Because failure of this CD4+ memory T cell–proliferative response was a strong correlate of early AIDS onset (15), CD4+ TEM cell dynamics appear to be a major determinant of immunocompetence in acute CCR5-tropic SIV infection, with clinical immunodeficiency requiring both the destruction of extant TEM cells and a failure to replenish these cells above a critical threshold (15, 23).

Whereas rapid progression results from a relatively abrupt, inadequately compensated alteration of a normal immune system, chronic AIDS is thought to result from a slow, progressive deterioration of a quasi-stable steady-state characterized by ongoing CD4+ T cell death and regeneration, and in particular, a pervasive, chronic immune activation that has been shown to be a strong predictor of the tempo of progression (10–12, 24–26). The question therefore arises as to whether a sustained or increasing CD4+ TEM cell deficit continues to play a primary pathogenic role, and if so, whether and how direct viral cytopathogenicity, immune activation, and/or other factors contribute to this deficit. Here, we address these questions with a detailed analysis of the development of AIDS in RMs chronically infected with SIVmac239. Our results continue to strongly implicate the inability to maintain CD4+ T cell populations in extra-lymphoid effector sites above a critical threshold as the common final pathway in the development of AIDS. However, direct viral destruction of effector site CD4+ TEM cell populations did not appear to be the determining mechanism of AIDS onset. Rather, we found that persistent immune activation renders these populations highly dependent on the proliferation and differentiation of (CCR5−) TCM cells for their homeostasis, and that this CD4+ TCM cell–derived, TEM cell production progressively declines in chronic infection. Thus, although CD4+ TEM cells are the primary targets of HIV/SIV infection, our data suggest that the direct and indirect effects of infection on the less efficiently targeted CD4+ TCM cell population determine the tempo of disease progression during chronic infection.

RESULTS

CD4+ memory T cell depletion in extra-lymphoid effector sites correlates with overt disease

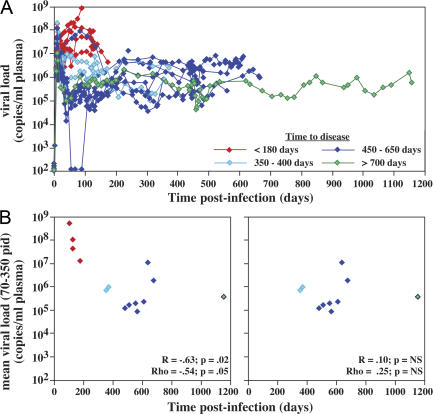

SIVmac239 and related CCR5-tropic SIVs are highly pathogenic for Indian origin RMs, inducing rapid disease progression (AIDS in <200 d) in ∼25% of infected animals and normal progression (AIDS in 1–3 yr) in the majority of the remainder (27). Fig. 1 A shows plasma viral loads (pvls) over the course of infection of 14 SIVmac239-infected RMs that did not receive antiretroviral therapy (ART) and were followed to an AIDS endpoint (4 rapid progressors and 10 normal progressors). As reported previously (15), rapid progressors manifest 1–2 log higher pvls than RMs destined for >350 d survival. However, among the latter group, plateau-phase pvls did not distinguish between RMs with considerably different survival periods. Indeed, when the entire study group was included in a correlation analysis of plateau-phase pvls versus time to endpoint, a significant association was observed (by either parametric or nonparametric analysis); however, when the four rapid progressors were excluded from the analysis, this association was no longer apparent (Fig. 1 B). Moreover, in all the normal progressors, pvls remained steady through the development of overt disease. Thus, within the range of viral replication manifested by typical SIV-infected normal progressors, the time to disease was not closely linked to mean pvls over time nor to any late acceleration of viral replication, observations suggesting that the rate of disease progression in these RMs was largely determined by their ability to handle the consequences of chronic viral replication, rather than by differences in viral replication itself.

Figure 1.

Relationship between pvl and survival in SIVmac239 infection. (A) Pvl data is shown for 14 SIVmac239-infected RMs that did not receive ART during their course and were followed to an AIDS endpoint. Profiles are color-coded according to time to endpoint as indicated. Note that the y axis starts at 102 copies/ml (the threshold sensitivity of the viral load assay) rather than 0 (acute-phase viral load data on these RM can be viewed in detail in reference 15). (B) The mean pvl for each RM from postinfection day (PID) 70 to either endpoint (rapid progressors) or PID 350 (normal progressors) is plotted against time to AIDS for all 14 RMs (left) or the 10 normal progressors alone (right). The graph configuration and color-coding are as described for A. Both linear regression (R) and Spearman rank (Rho) correlation coefficients and the p-values for these analyses are indicated in each plot. NS, nonsignificant.

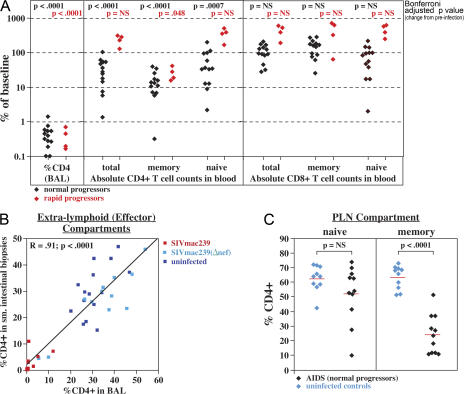

A major consequence of acute CCR5-tropic SIV infection is destruction of CD4+ memory T cells, particularly CD4+ TEM cells in extra-lymphoid effector sites, and we have previously shown that a strong immunologic correlate of rapid progression is the failure to follow this initial CD4+ TEM cell depletion with a sustained increase in the fraction of proliferating CD4+ memory T cells (15). This increase provides “targets” for SIV (12, 20), but also contributes to the continuous production of new CD4+ TEM cells that limits extra-lymphoid tissue deficits and prevents immunological collapse (15). As it is possible that the same mechanisms extend to chronic progression, we asked first whether CD4+ TEM cell depletion was a specific and uniform feature of SIVmac239-mediated AIDS (Fig. 2). Because almost all bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) T cells manifest the phenotypic signature, CCR7− and/or CCR5+, of TEM cells (18, 23), the fate of CD4+ T cells in this site provides insight into the extra-lymphoid CD4+ TEM cell compartment. As shown in Fig. 2 A, analysis of 13 normal progressors and 4 rapid progressors demonstrated that overt disease in both settings was uniformly associated with a striking (>99%) decline in CD4+ T cell representation among BAL TEM cells. Because total lymphocyte recovery from BAL in later stages of infection was comparable to or reduced from preinfection (unpublished data), this decline predominantly represents CD4+ TEM cell depletion, rather than CD8+ TEM cell expansion. Importantly, the representation of CD4+ T cells in BAL closely correlated with that of small intestinal lamina propria, another TEM cell–populated effector compartment (18), suggesting that the BAL compartment was an accurate indicator of systemic effector site CD4+ TEM cell representation (Fig. 2 B).

Figure 2.

Systemic analysis of T cell populations in SIVmac239-infected RMs with overt immunodeficiency. (A) The absolute number of total, memory, and naive CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in the blood and the percent CD4+ T cells (of total CD3+) in BAL were evaluated by flow cytometry at the time of infection (baseline) and at an AIDS endpoint in 17 SIVmac239-infected RMs: 4 rapid progressors (red) and 13 normal progressors (black). Results are presented as percent change from baseline, with the significance of this change assessed separately for normal and rapid progressors using a mixed-effects statistical model. (B) The percent CD4+ of total T cells in BAL is plotted against the same measurement in small intestinal (jejunal) biopsy cell preparations from RMs with pulmonary lavage examination and small intestinal biopsy within 7 d of each other. The analysis includes 12 plateau-phase SIVmac239-infected RMs (red; median pvl = 550,000 copies/ml), 12 SIVmac239(Δnef)-infected RMs (light blue; median pvl = 180 copies/ml), and 15 SIV− normal control RMs (dark blue). The plot shows a linear regression line with the correlation coefficient and p-value of the correlation indicated in the top left corner. (C) PLNs from 11 SIVmac239-infected normal progressors with AIDS and 10 SIV− control RMs were analyzed by flow cytometry for evidence of relative CD4+ depletion in either the memory or naive compartments. CD3+ T cells, including both CD4+ and CD8+ lineages, were first separated into naive and memory compartments by phenotypic criteria (see Materials and methods), and then the relative fractions of CD4+ cells within these compartments were determined. Results are presented as percent CD4+ (of total naive or memory T cells). The red lines designate the mean percent CD4+ values, with significance of differences between SIV− and SIV+ RMs determined by unpaired t test.

Decline in the absolute number of circulating total CD4+ memory T cells was also highly significant in both rapid and normal progression, albeit less dramatic than the loss of CD4+ TEM cells in BAL (Fig. 2 A). In contrast, the numbers of CD4+ naive T cells in blood were not a strong correlate of AIDS as they were only variably and modestly diminished in chronic AIDS and, as described previously (15), were actually increased in rapid progression. Because of this CD4+ naive T cell heterogeneity, the absolute numbers of total CD4+ T cells in blood, the standard marker in disease progression in HIV infection (1), were significantly reduced only in the chronically SIV-infected RMs, and even in this setting, the extent of this loss was highly variable. The numbers of circulating CD8+ T cells, both memory and naive, also varied in overt AIDS but tended to be normal or elevated (Fig. 2 A). Cross-sectional analysis of the overall naive and memory T cell compartments of peripheral LNs (PLNs) in AIDS-stage normal progressors versus uninfected RMs revealed a statistically significant decline in CD4+ representation in the total memory, but not the naive, compartments (Fig. 2 C), providing further evidence that systemic CD4+ memory, but not naive, T cell depletion is a uniform T cell population correlate of AIDS.

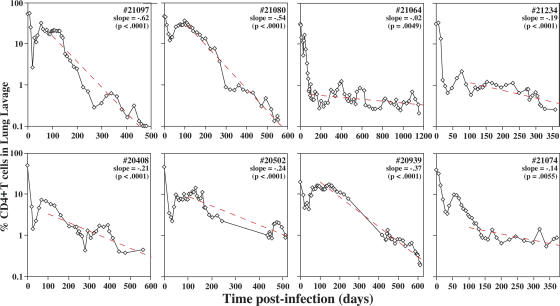

Collectively, these data indicate that BAL CD4+ TEM cell depletion is the most profound T cell population abnormality in AIDS (P < 0.0001), but as severe depletion has already occurred in acute infection, the resulting CD4+ TEM cell deficit might not be expected to play a determining role in the much later onset of chronic-phase disease. However, as shown in Fig. 3, CD4+ T cell frequencies in BAL initially rebounded after acute depletion, but after day 100, they progressively declined in all normal progressors examined (with a mean population half-life of ∼107 d; see legend to Fig. 3). This observation strongly supports the hypothesis that CD4+ TEM cell depletion constitutes a primary mechanism of immunodeficiency, with overt disease ensuing when the representation of these cells in extra-lymphoid effector sites declines below a critical level. At the time of AIDS onset in our cohort, the average (± SEM) fraction of CD4+ T cells within the BAL T cell compartment was 0.42 ± 0.08%, a value that provides a substantive estimate for this critical threshold.

Figure 3.

Kinetics of CD4+ T cell decline in the lung. BAL cell preparations were stained for CD3 and CD4, and the percent CD4+ T cells (of total CD3+ T cells) was determined by flow cytometry for eight SIVmac239-infected normal progressors that did not receive ART during their course and were followed to an AIDS endpoint (note that nearly all BAL T cells are TEM cell phenotype [18]). For each RM, the Δlog10(%CD4) per 100 d was determined from PID 100 to endpoint (“slope”), and the p-value of the regression line is designated in the top right corner of each profile. The pooled Δlog10(%CD4) per 100 d plus SEM for all eight RMs was −0.28 ± 0.04 (P = 0.0003), which corresponds to an average CD4+ T cell population half-life of 107 d (using the formula t1/2 = log10(0.5)/b, where b is the pooled slope estimate).

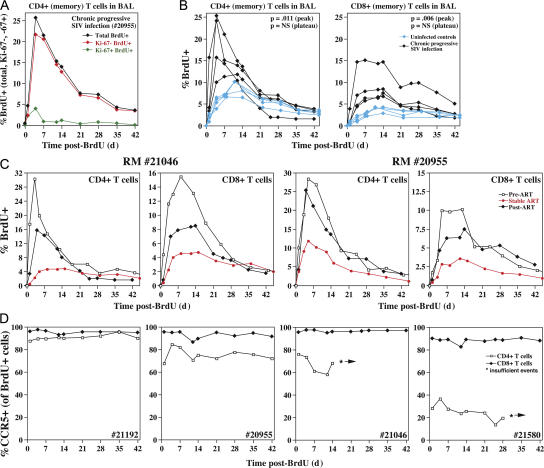

T cell populations in BAL are short-lived and dependent on continuous TEM cell production and migration

To investigate the mechanisms underlying BAL CD4+ TEM cell decline, we used short-term BrdU labeling (three doses over 24 h) to compare the dynamics of BAL TEM cell populations in clinically stable, chronically SIVmac239-infected RMs versus uninfected RMs. Fig. 4 A shows a typical profile of a chronically infected RM. Note that peak labeling exceeds 25% of BAL CD4+ T cells, occurs 4 d after the last BrdU dose, and includes cells that are almost entirely postproliferative (Ki-67−). Collectively with previous observations (15), these data indicate that a substantial fraction of the BAL CD4+ TEM cell population is replaced daily from recently divided precursors, originating elsewhere, and emigrating to the lung via the blood. The vast majority of labeled cells disappear over the ensuing month, which, in the absence of proliferative dilution, is most likely due to in situ death (and replacement by nonlabeled cells). Both the peak labeling of CD4+ TEM cells in chronically infected RMs and the subsequent reduction in number of these labeled cells were two- to threefold greater than in uninfected RMs (Fig. 4 B), indicating a substantial increase in the fraction of short-lived cells within the BAL population of infected versus uninfected animals. Notably, the peak BrdU labeling and the magnitude of the subsequent decay of CD8+ TEM cells in BAL were similarly elevated in the infected versus uninfected RMs, and effective ART normalized the BrdU labeling profiles of both CD4+ and CD8+ TEM cells (Fig. 4 C). As viral cytopathogenicity would affect CD4+ TEM cells much more than CD8+ TEM cells, the essentially identical dynamics and ART response of the two subsets strongly suggest that the accelerated turnover of BAL TEM cells primarily reflects immune activation-mediated apoptosis, rather than viral-mediated destruction. To further assess whether direct coreceptor-targeted, viral-mediated cell destruction contributes to the rapid decline of BrdU-labeled CD4+ TEM cells in BAL, we compared the frequency at which these cells expressed CCR5 over time to that of labeled CD8+ TEM cells (Fig. 4 D). Direct viral-mediated killing would be expected to preferentially target the CCR5+ component of CD4+ TEM cells, resulting in decreasing frequencies of CCR5+ cells over time among labeled CD4+ TEM cells, but not CD8+ TEM cells. Importantly, CCR5 expression was largely stable in the labeled CD4+ TEM cells in the BAL of infected RMs, further indicating that if direct viral killing of recently divided CD4+ TEM cells in BAL was occurring, its contribution to the decreased lifespan of these cells in infected RMs must be quite small relative to their overall rate of loss.

Figure 4.

TEM cell dynamics in the pulmonary airspace. (A) An SIVmac239-infected normal progressor (RM no. 20955: PID 1,125; pvl = 69,000 copies/ml) was administered three intravenous doses (30 mg/kg) of BrdU over 24 h, and BAL samples were obtained before BrdU administration (day 0) and at subsequent intervals for flow cytometric analysis of BrdU incorporation in CD4+ T cells. The first post-BrdU sampling was 14 h after the last BrdU dose and is designated day 1. The percentage of total BrdU+ cells, Ki-67− BrdU+ cells, and Ki-67+ BrdU+ cells was determined at each time point. (B) BrdU was administered to and BAL samples were collected from four uninfected (control) RMs and four plateau-phase SIVmac239-infected RMs (RM no. 20955, as above; no. 21046: PID 1,125; pvl = 360,000 copies/ml; no. 21192: PID 456; pvl = 240,000 copies/ml; no. 21580: PID 876; pvl = 80,000 copies/ml) as described in A. The overall percent BrdU+ in BAL CD4+ and CD8+ T cell populations are shown. Differences in peak and plateau (day 42) labeling were determined by unpaired t test (p-values shown in the top right corner of each profile). (C) BrdU was administered to and BAL samples were collected from RM numbers 21046 and 20955 three successive times over the course of their SIVmac239 infection: Pre-ART (PID 577; pvls = 200,000 and 500,000 copies/ml, respectively; percent CD4+ in BAL = 0.41 and 1.7%, respectively); on stable ART (PID 764: pvls = 280 and <30 copies/ml, respectively; percent CD4+ in BAL = 19.7 and 9.6%, respectively), and 7 mo after ART discontinuation (PID 1,125; pvls = 360,000 and 69,000, respectively; percent CD4+ in BAL: 0.43 and 1.4%, respectively). The overall percent BrdU+ of BAL CD4+ and CD8+ T cell populations is shown. (D) CCR5 expression was determined by flow cytometry on the BrdU-labeled CD4+ and CD8+ T cells of the SIVmac239-infected RMs described in B. The fraction of BrdU+ CD4+ and CD8+ T cells expressing CCR5 is shown over time (*, insufficient cells for analysis). A random slope statistical model was used to determine the stability of CCR5 expression over time for the labeled CD4+ T cells. This analysis showed that (a) none of the individual slopes (loss of CCR5-expressing, BrdU+ CD4+ T cells in BAL over time) was statistically significant after adjusting for multiple comparisons, and (b) the overall slope (average loss per day among four animals) was not statistically significant.

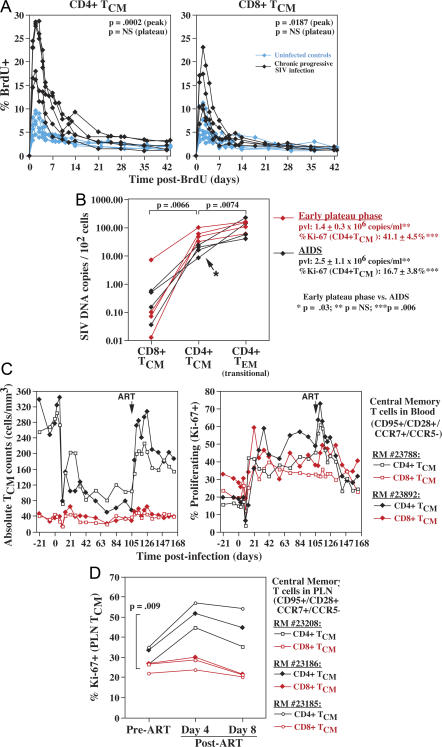

Progressive loss of CD4+ TCM cell homeostasis and TEM cell production in chronic infection

The above data indicate that during chronic infection, the diminished BAL CD4+ TEM cell population is largely comprised of relatively short-lived cells that are highly dependent on new memory cell production and emigration for homeostasis, a finding suggesting that CD4+ memory T cell production dynamics might play a role in the progressive decline of BAL CD4+ TEM cells in chronically infected RMs. As shown in Fig. 5 A, the proliferating (Ki-67+) fraction of CD4+ memory T cells in the blood may indeed fall during chronic infection (RMs nos. 20197 and 20408), but this decline is not uniform, coming very late in some RMs (no. 21064) and not at all in others (no. 20502). However, systemic production is more directly related to the overall number of proliferating cells, and we therefore followed the absolute number of proliferating total memory T cells in the blood throughout the course of infection in eight untreated SIVmac239-infected normal progressors and in four RMs with attenuated (clinically nonprogressive) SIVmac239(Δnef) infection (Fig. 5 B). This analysis demonstrated a highly significant progressive loss of proliferating CD4+ memory T cells in the normal progressors, but not of proliferating CD8+ memory T cells in the same RM. In attenuated SIVmac239(Δnef) infection, the numbers of proliferating CD4+ memory T cells showed a very slight decline over 600 d that did not quite achieve statistical significance.

Figure 5.

Proliferating CD4+ and CD8+ memory T cell dynamics in the blood. (A) The fraction of proliferating cells (Ki-67+) is shown over the course of chronic/progressive SIVmac239 infection in four representative RMs that did not receive ART and were followed to an AIDS endpoint. (B) The absolute number of proliferating (Ki-67+) CD4+ and CD8+ memory T cells is shown for the entire course of SIVmac239 infection in the same group of untreated normal progressors described in Fig. 3, and for comparison, a group of SIV(Δnef)-infected nonprogressors followed for 600 d. The pooled Δlog10(%Ki-67+ memory T cells) per 100 d (± SEM) from PID 100 to endpoint (progressors) or PID 100–600 (nonprogressors) is shown for each analysis, along with the p-value delineating the statistical significance of these pooled slopes.

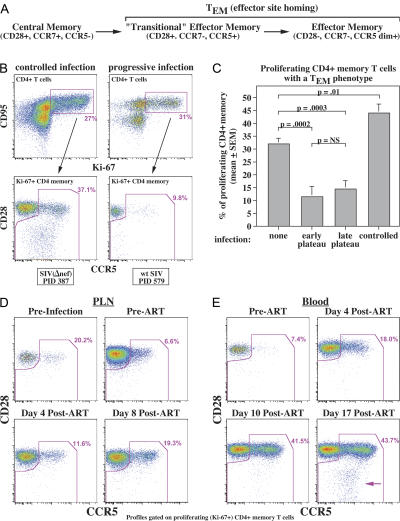

The overall memory T cell population in blood is composed of three phenotypically distinguishable components:TCM cells, transitional TEM cells, and fully differentiated TEM cells, with both TEM cell subsets expressing CCR5 and being effector site directed (Fig. 6 A) (18). On average, approximately one third of the proliferating CD4+ memory T cell compartment in the blood of uninfected RMs is comprised of CCR5-expressing TEM cell subsets; however, in SIV-infected RMs, this fraction is highly dependent on the degree of pathogenesis. In attenuated SIV infections or wild-type SIV infections in RMs with spontaneous control, we observed a significant increase in the TEM cell fraction of proliferating CD4+ memory cells in comparison to uninfected RMs, consistent with the expected effect of chronic immune activation in driving effector differentiation (28). In contrast, the TEM cell fraction was reduced approximately fourfold throughout pathogenic infection (Fig. 6, B and C). CD4+ TEM cells (predominantly transitional type) were also reduced in PLNs in chronic SIVmac239 infection (Fig. 6 D), indicating that the reduction in proliferating CD4+ TEM cells in the blood was not due to retention in secondary lymphoid tissues. Moreover, effective ART results in an immediate burst of proliferating or recently divided transitional CD4+ TEM cells in the PLNs and blood (Fig. 6, D and E), followed later by mature CD4+ TEM cells (Fig. 6 E), suggesting that although rapid CD4+ TEM cell generation and differentiation is continuously driven by infection-associated immune activation, these new TEM cells and/or their immediate precursors are being destroyed almost as rapidly by direct virus-mediated cytopathogenicity. Importantly, the efficiency of this depletion does not appear to change over the course of chronic infection (compare early vs. late plateau-phase in Fig. 6 C), suggesting that this effect acts as a relatively constant impediment to CD4+ TEM cell production that does not, by itself, explain the progressive decline in CD4 TEM cell populations in extra-lymphoid sites.

Figure 6.

Effect of infection on CD4+ TEM cell differentiation from proliferating TCM cell precursors. (A) Schema of memory T cell differentiation in RMs (18). (B) The top profiles show CD4+ T cells from one RM with attenuated SIVmac239(Δnef) infection (PID 387; pvl = 5,200 copies/ml) and one with progressive SIVmac239 infection (PID 579; pvl = 3,800,000 copies/ml), indicating the gating of proliferating (Ki-67+) CD4+ memory T cells. The bottom profiles show the representation of TCM cells (CD28+; CCR5−) versus total TEM cells (including CD28+, CCR5+ transitional TEM cells, and CD28−/CCR5dim+ mature TEM cells) within the proliferating CD4+ memory compartment. (C) The figure shows cross-sectional analysis of the fractional representation of total TEM cells (as in A) in 10 SIV− RMs, 7 RMs with early plateau-phase SIVmac239 infection (PID 105; median pvl = 5,300,000 copies/ml), 8 RMs with late plateau-phase SIVmac239 infection (PID 533–878; median pvl = 660,000 copies/ml), and 12 RMs with controlled SIV infection: 9 infected with SIVmac239(Δnef) (PID 154–390; pvls < 400 copies/ml) and 3 spontaneous controllers of SIVmac239 (PID 105–147: pvls < 4,000 copies/ml). Differences were assessed by unpaired t test. (D) The profiles show the fractional representation of TEM cells among proliferating (Ki-67+) CD4+ memory T cells from PLNs from an RM 5 d before SIVmac239 infection, at PID 150 (immediately before ART; pvl = 4,400,000 copies/ml), and at 4 (pvl = 180,000) and 8 d (pvl = 87,000) after ART initiation. (E) The profiles show the fractional representation of TEM cells among proliferating (Ki-67+) CD4+ memory T cells from the blood of an SIVmac239-infected RM at PID 105 (immediately before ART; pvl = 3,000,000 copies/ml) and days 4 (pvl = 220,000 copies/ml), 10 (pvl = 170,000 copies/ml), and 17 (pvl = 24,000 copies/ml) after ART. The arrow indicates the development of a fully mature CD4+ TEM cell population.

CD4+ TCM cells are susceptible to immune activation, infection, and direct virus-mediated destruction

Collectively, these data (an overall decrease in proliferating CD4+ memory T cells and stable rates of CD4+ TEM cell differentiation) lead to the conclusion that the progressive decline in CD4+ TEM cell production in chronic SIV infection originates from a progressive decline in proliferating CD4+ TCM cells caused by a decreasing CD4+ TCM cell proliferation rate and/or a progressive decline in overall CD4+ TCM cell numbers (Fig. 2, A and C). Factors contributing to loss of CD4+ TCM cell homeostasis would therefore constitute primary determinants of immunodeficiency development. One such factor might be persistent immune activation with its previously demonstrated effect of increasing T cell proliferation and turnover (12, 34). Indeed, we found that in the chronically SIV-infected RMs studied here, CD4+ TCM cells manifest a higher fraction of proliferating cells with rapid turnover (Fig. 7 A), potentially leading to proliferative senescence and/or inadequate renewal of long-lived cells (11, 29). However, interpreting these factors as contributing to the progressive failure of CD4+ TCM cell homeostasis is not straightforward because CD8+ TCM cell populations, which are relatively stable during chronic infection, manifest similar, although somewhat less severe, changes in proliferation and turnover in infected RMs (Fig. 7 A).

Figure 7.

Effect of infection on CD4+ TCM cell homeostasis. (A) BrdU was administered to and blood samples were collected from five uninfected (control) RMs and five late plateau-phase SIVmac239-infected RMs (PID 466–1125; median pvl = 240,000 copies/ml) as described in Fig. 4. The overall percent BrdU+ was determined by flow cytometry on CD95+, CD28+, and CCR5− TCM cells, both CD4+ and CD8+, at the time points shown. Data from all 10 RMs are included in the CD4+ TCM cell analysis. As one SIV+ RM had insufficient numbers of evaluable CD8+ TCM cells, only four SIV+ RMs are included in the CD8+ TCM cell analysis. (B) CD4+ and CD8+ TCM cells (CD95+, CD28+, CCR5−, CCR7+) and CD4+ transitional TEM cells (CD95+, CD28+, CCR5+) were sorted from splenic mononuclear cell preparations taken at necropsy from eight SIVmac239-infected RMs (four with early [asymptomatic] plateau-phase infection [PID 78–85] and four with chronic-onset AIDS [PID 372, 483, 554, and 1,157]) and assessed for SIV DNA content. The average pvl and percent Ki-67+ within the splenic CD4+ TCM cells from each RM group are also shown. The significance of differences was assessed by unpaired t test. (C) The absolute number and fractional proliferation (percent Ki-67+) of highly defined CD4+ and CD8+ TCM cells in the blood are shown for two representative SIVmac239-infected RMs through early plateau phase and after ART. The median pre-ART plateau-phase pvls in both of these RMs were ∼4,000,000 copies/ml, with ART decreasing these values to 22,000 and 50,000 copies/ml for RM numbers 23788 and 23892, respectively. (D) Three SIVmac239-infected RMs were treated with ART at PID 132 (no. 23186) or PID 153 (nos. 23208 and 23186) with PLN biopsy immediately before and 4 and 8 d after ART (mean pre-ART and post-ART days 4 and 8; pvls = 6,000,000, 237,000, and 56,000 copies/ml, respectively). The proliferating fraction (percent Ki-67+) of CD4+ and CD8+ TCM cells from each of these PLN biopsies is shown (with differences between post-ART change in percent Ki-67+ of CD4+ and CD8+ TCM cells evaluated by paired t test).

A factor with perhaps greater potential to differentially affect CD4+ TCM cell versus CD8+ TCM cell homeostasis is direct SIV infection of the former subset. True CD4+ TCM cells lack detectable surface expression of the CCR5 coreceptor and thus would be predicted to be protected from infection; however, previous work has suggested that detectable surface expression of CCR5 may not be necessary for a CD4+ memory cell to be infected (30). Indeed, as shown in Fig. 7 B, SIV DNA was readily detectable by real-time PCR in sorted, precisely defined (CCR7+ CCR5−) CD4+ TCM cells from both early plateau-phase RMs and normal progressors with AIDS. SIV DNA was either absent from CD8+ TCM cells or found at significantly lower levels. In normal progressors with AIDS, SIV DNA levels in CD4+ TCM cells were ∼15% of those detected in CD4+ (CCR5+) transitional TEM cells, consistent with a less efficient infection of the former subset. Interestingly, the SIV DNA content of CD4+ TCM cells from RMs with early plateau-phase SIVmac239 infection was significantly (threefold) higher than in the RMs with end-stage infection, whereas SIV content of CD4+ TEM cells was not different between these RM groups. This difference in CD4+ TCM cell infection was not related to overall SIV replication, as pvls were not significantly different in the two groups. However, CD4+ TCM cell proliferation (%Ki-67) was significantly higher in the early plateau-phase RMs, suggesting that CD4+ TCM cell infection can be driven by high activation/proliferation to levels approaching those of CD4+ TEM cells with overt CCR5 expression.

To determine the pathobiologic significance of this CD4+ TCM cell infection, we compared the dynamics of (CCR7+ CCR5−) CD4+ and CD8+ TCM cells during acute SIVmac239 infection and through early plateau-phase ART administration. As illustrated in two representative RMs (Fig. 7 C), absolute numbers of CD4+ TCM cells in the blood decline ∼70% in acute infection, concomitant with a 98–99% depletion of BAL CD4+ TEM cells in the same RM (not depicted). The observations that (a) CD8+ TCM cells show only a modest, very transient depletion during this period (Fig. 7 C), and (b) that CD4 representation in the PLN TCM cell compartment declines to a similar degree as blood CD4+ TCM cell counts (not depicted) suggest that the CD4+ TCM cell depletion primarily reflects direct viral-mediated killing of CD4+ TCM cells, rather than a redistribution effect. Increased proliferation rates stabilize circulating CD4+ TCM cell numbers in plateau-phase infection, but continued viral-mediated killing is demonstrated by the observation that ART administration in plateau-phase results in a very rapid and lineage-specific increase in CD4+ TCM cell counts and in the fraction of proliferating CD4+ TCM cells (Fig. 7 C). A similar increase in proliferation with ART is observed in PLNs (Fig. 7 D), suggesting that ART is acting immediately to relieve direct viral-mediated destruction of rapidly proliferating CD4+ TCM cells. Thus, despite undetectable CCR5 expression, CD4+ TCM cells, particularly proliferating cells, are SIV infectable and directly killed by virus.

DISCUSSION

In the past few years, it has been widely documented that primary infection with pathogenic, CCR5-tropic HIV and SIV, though generally asymptomatic, has extensive immunologic consequences (12, 20, 21, 23). The high viral replication of primary infection rapidly destroys the bulk of the body's CD4+ memory T cell population, particularly CD4+ TEM cells in mucosal extra-lymphoid effector sites (15, 19, 30, 31), and also initiates a state of persistent immune activation that has been widely implicated in immunodeficiency development (10–12, 21, 24, 25, 32). However, CD4+ memory T cells are not equally susceptible to this acute destruction, and in SIV-infected RMs, we have previously demonstrated that spared populations (predominantly CCR5− TCM cells) undergo a substantial increase in proliferative activity that sustains these populations and provides sufficient TEM cell production and influx into effector sites to maintain clinical immune competence (15). Chronically SIV-infected RMs and HIV-infected humans establish a new immunologic steady-state associated with high CD4+ memory T cell turnover and characterized by a substantially diminished CD4+ TEM cell compartment (11, 12, 15, 22, 33–35). Ultimately, this steady-state is degraded and immunodeficiency ensues, but the quantitative changes in rate-limiting parameters that underlie this degradation in the course of chronic infection, as well as the mechanisms responsible for these changes, have not been clearly defined.

Here, we systematically assessed the relationship between potential determinants of pathogenesis and AIDS onset in chronically SIVmac239-infected RMs. Although it remains possible that there are multiple paths to AIDS in this model, our data strongly support a common “primary” pathway and suggest a surprisingly cohesive mechanistic sequence. Two important virologic observations guided our investigation: first, that within the range of plateau-phase pvls manifested by SIVmac239-infected normal progressors, these pvls did not strongly predict time to disease, and second, that the plateau-phase pvls in these normal progressors remained steady through to disease onset. Regarding the first observation, it is clear that in HIV infection, plateau-phase pvls delineate broad groups of individuals with different rates of disease progression (3), but the predictive value of viral replication is limited (36), and host factors (such as the degree of immune activation) have been demonstrated to exert a major influence on prognosis (24–26). Similarly, although SIVmac239 replication rates predict rapid versus normal versus slow progression in RMs (15, 37–39), they did not account for the range of disease-free survival times exhibited by normal progressors in our study, strongly suggesting that in these RMs, host factors are the primary determinants of chronic-phase disease. The stability of plateau-phase pvls through disease onset in the normal progressors studied here further supports this hypothesis, suggesting that a diminishing ability of host immunity to control viral replication or the emergence of more efficiently replicating viral variants were unlikely to be the critical processes leading to AIDS.

We next established that BAL CD4+ TEM cell depletion was the strongest correlate of disease. Most importantly, having shown that changes in the CD4+ TEM cell representation in BAL closely paralleled changes in the small intestine, we demonstrated a highly consistent, gradual progression in BAL CD4+ TEM cell depletion from the initial post-acute steady-state to disease onset in chronic, progressive infection. The latter observation supports the existence of a threshold in effector site CD4+ TEM cell representation below which the SIV-infected host becomes highly susceptible to opportunistic infection. This interpretation is even more compelling given our previous observation that rapid progression to AIDS was associated with cessation of CD4+ TEM cell production and influx into extra-lymphoid sites (15), and the fact that the opportunistic infections found in our AIDS-afflicted RMs (CMV, cryptosporidia, pneumocystis) most commonly developed in such effector sites (unpublished data). We do not discount the possibility that functional or repertoire alterations of CD4+ or CD8+ memory T cells or abnormalities in accessory non–T cells might also contribute to immune deficiency, but would postulate that such qualitative abnormalities would serve to facilitate immune deficiency only in the setting of profound CD4+ TEM cell depletion, perhaps affecting the threshold of CD4+ TEM cell depletion at which overt immune deficiency ensues.

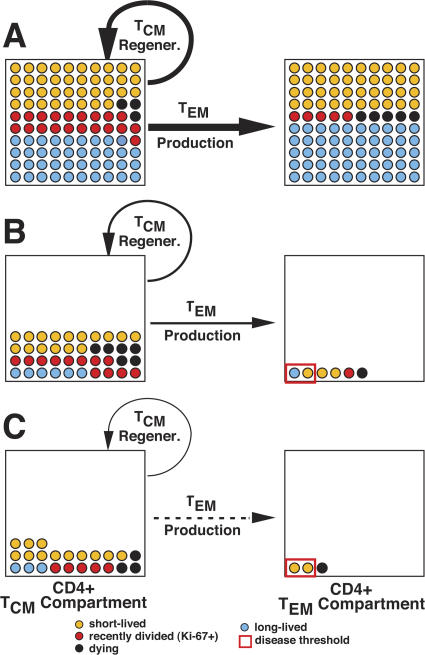

BrdU labeling of chronically SIVmac239-infected RMs was then used to explore the dynamics of pulmonary CD4+ TEM cells and provide insights into the mechanisms underlying their progressive decline. We found that this population is largely comprised of short-lived nonreplicating cells and consequently is highly dependent on the continuous emigration of recently divided TEM cells from the blood. Notably, pulmonary CD8+ TEM cells manifested similar kinetic properties suggesting that (a) the short life span of the CD4+ TEM cells in BAL was not attributable to direct viral-mediated destruction, but rather was likely a result of chronic immune activation (12, 34), and (b) that the progressive decline in CD4+ TEM cells was determined elsewhere, probably by factors controlling the supply of these cells to extra-lymphoid effector sites. In keeping with the latter hypothesis, we found that absolute numbers of proliferating or recently divided CD4+, but not CD8+, memory T cells in the blood progressively declined in chronic SIVmac239 infection (but not in attenuated SIVmac239(Δnef) infection). The fraction of these proliferating or recently divided CD4+ memory cells exhibiting TEM cell differentiation (i.e., the immediate precursors to extra-lymphoid site TEM cells) was considerably diminished in progressive infection by direct virus-mediated destruction (Fig. 6), but, importantly, this fraction did not appear to change over the course of chronic infection. Collectively, these findings strongly suggested that a progressive, systemic decline of the proliferating CD4+ TCM cell compartment resulted in a progressively diminished substrate for CD4+ TEM cell differentiation. This in turn reduced CD4+ TEM cell production and effector site emigration, leading to decreasing effector site CD4+ TEM cell populations and ultimately (when the latter fell below threshold) to AIDS (Fig. 8).

Figure 8.

The descent to AIDS: decreasing numbers and changing proportions of CD4+ memory T cell populations in chronic SIVmac239 infection. The figure schematically illustrates the progressive decline in the regeneration of long-lived TCM cells and, consequently, in the production of short-lived, tissue-seeking TEM cells. The TCM cell compartment consists of TCM cells in secondary lymphoid tissues and recirculating in the blood. The TEM cell compartment represents cells resident in extra-lymphoid effector sites. Estimated populations include: (a) recently divided (Ki-67+) cells (cells that have been in S-phase of the cell cycle in the preceding week), (b) short-lived cells (Ki-67− cells destined to die or resume division in <2–3 wk), (c) long-lived cells (Ki-67− cells destined to live >3 wk without cell division), and (d) dying cells (either apoptosis or direct viral destruction). The left to right horizontal arrows indicate the relative rate of production and effector site emigration of TEM cells. The semicircular arrow adjacent to the TCM cell compartment indicates the relative efficiency of TCM cell regeneration (note that proliferating TCM cells provide the substrate for both TCM cell regeneration and TEM cell production). (A) Preinfection baseline. Both TCM and TEM cell compartments include relatively large proportions of long-lived cells. (B) Asymptomatic chronic phase—mid-course. Both compartments have experienced dramatic acute-phase depletion (TEM > TCM) and have established a quasi-stable steady-state with substantially reduced cell numbers, especially of long-lived cells, and increased proliferation and death rates. Both TCM cell regeneration and TEM cell production are reduced severalfold from baseline, despite the increased proportion of proliferating TCM cells, but this fractional increase in a reduced compartment is still sufficient to maintain predominantly short-lived TEM cell populations above the immune deficiency threshold. (C) End-stage chronic phase—AIDS onset. Progressive decline in the TCM cell compartment has reduced TEM cell production and delivery to effector sites below the minimum necessary to maintain TEM cell populations above threshold, leaving these sites increasingly susceptible to opportunistic infection.

In contrast to a previous report (33), CD4+ naive T cell populations were not generally depleted in the progressive infections studied here, as measured by both the absolute numbers of CD4+ naive T cells in the blood and the relative representation of CD4+ versus CD8+ naive T cells in PLNs. Thus, at least in the SIVmac239 AIDS model, CD4+ TCM cell homeostasis can fail in the face of a relatively intact CD4+ naive cell compartment. Moreover, studies of thymectomized RMs infected with CXCR4-tropic (naive CD4+ T cell–depleting) SIVmac155T3 (15) have demonstrated that CD4+ TCM cell homeostasis can be maintained long-term in the complete absence of a CD4+ naive T cell compartment (unpublished data). These data suggest that although naive CD4+ T cells are nominally the precursors for CD4+ TCM cells, the naive population is not a major determinant of CD4+ TCM cell homeostasis in chronic SIV infection.

What then is responsible for the progressive decline in CD4+ TCM cell production? BrdU labeling studies demonstrate that both CD4+ and CD8+ TCM cell populations manifest a sustained increase in cell turnover in chronic SIV infection, consistent with an immune activation effect (12) and potentially setting up these populations for slow proliferative senescence (10, 29). This increase in turnover, measured in the blood, is slightly more pronounced for CD4+ TCM cells than CD8+ TCM cells, but this difference, by itself, seems unlikely to explain the gross disparity in CD4+ versus CD8+ TCM cell stability. However, we also demonstrate that, as opposed to CD8+ TCM cells, CD4+ TCM cells are readily infected by CCR5-tropic SIV in vivo (albeit less efficiently than CCR5+ TEM cells), and are, in fact, continuously destroyed in vivo by a direct, virus replication-dependent mechanism (as revealed by their immediate post-ART kinetics). This killing clearly targets proliferating CD4+ TCM cells in LNs (Fig. 7 D) before their emigration into the blood, therefore making their loss “invisible” to BrdU analysis in the blood (indicating that total CD4+ TCM cell loss rates are underestimated by this analysis). This ongoing, virus-mediated CD4+ TCM cell destruction, especially of the proliferating compartment in LNs, would clearly put CD4+ TCM cell homeostasis under more stress than its CD8+ counterpart, potentially leading to imbalance in production versus destruction in the former, but not the latter, subset. Other factors could also contribute to a CD4+ TCM cell homeostatic imbalance, including progressive damage to microenvironments supportive of TCM cell homeostasis (9, 40) and progressive loss of regeneration capacity due to accelerated “aging-like” disorganization of the immune system (12). Even though such factors would potentially affect both CD4+ and CD8+ subsets, the effects need not be equal (9, 21).

Our data define a complex interplay between cell destruction by direct infection on the one hand and immune activation on the other in AIDS pathogenesis. With regard to the CD4+ TEM cell compartment, direct viral-mediated destruction (either productive infection or virus-triggered apoptosis) is almost certainly responsible for the initial depletion of extra-lymphoid site CD4+ TEM cells in acute infection (15, 30, 31) and for the continuous elimination of ∼70% of the differentiating CD4+ TEM cells arising from TCM cell precursors in PLNs and blood (this study). In chronic infection, however, the fate of extra-lymphoid site TEM cells, both CD4+ and CD8+, appeared to be governed by immune activation with a considerably larger proportion of cells of both subsets possessing shorter life spans (due to activation-induced apoptosis) than those observed in uninfected controls. Interestingly, although infected CD4+ T cells can be visualized by in situ hybridization in the extra-lymphoid effector sites of these RMs (unpublished data), we found no functional evidence that this infection further shortened the already brief life span of most CD4+ TEM cells. However, the initial viral-mediated depletion and the immune activation-mediated shortening in the average life span of extra-lymphoid site CD4+ TEM cells render this population highly dependent on a continuous influx of new cells that are derived from the proliferation and differentiation of TCM cells. Immune activation drives this CD4+ TCM cell proliferation and differentiation, but at the same time it appears to increase the susceptibility of these cells to infection and destruction, reducing their steady-state production. Persistent immune activation is also thought to be responsible for the microenvironmental destruction and aging-like disorganization of the immune system mentioned above (12), and these indirect processes likely combine with the direct viral effects to destabilize CD4+ TCM cell homeostasis, resulting in the slow, progressive decline of this precursor population.

Our model suggests that CD4+ TCM cell decline may “set the clock” in regard to the timing of AIDS onset in RMs and therefore predicts that protection of CD4+ TCM cell homeostasis may be the key to preventing AIDS, a notion supported by the recently reported positive correlation between the numbers of circulating CD4+ CD28+ T cells (predominantly TCM cells) with long-term survival in vaccinated SIVmac-challenged RMs that fail to control viremia (41). It is also noteworthy that in the natural apathogenic SIV infections of African monkeys, viral loads are as high or higher than in pathogenic infections of humans and RMs and initial extra-lymphoid CD4+ TEM cell depletion is as extensive, but in the vast majority of these infections, CD4+ memory T cell populations in the blood and LNs are maintained and CD4+ TEM cell depletion is not progressive (references 42–46 and Silvestri, G., personal communication). Although the mechanisms underlying the lack of clinical progression in these highly active infections are likely complex and multi-factorial, the fact that preservation of the CD4+ TCM cell compartment is associated with maintenance of a diminished, but stable, CD4+ TEM cell compartment suggests that in these animals, the CD4+ T cell system may be able to tolerate the consequences of continuous viral replication because a preserved CD4+ TCM cell compartment can stably maintain CD4+ TEM cell populations at supra-threshold levels. Notably, these infections lack the chronic immune activation response that characterizes pathogenic infection (42–46), in keeping with our above described hypothesis that chronic immune activation undermines CD4+ TCM cell stability.

Progression of typical SIVmac239 infection to AIDS (e.g., normal progression with AIDS onset at 1.5–2 yr after infection) is approximately fivefold accelerated relative to HIV infection, and the plateau-phase pvls in this model are ∼10-fold higher (3), raising the question of whether the mechanisms proposed here for RMs apply to human infection. In arguing that this is indeed likely to be the case, we would submit that the crucial mechanisms that we have identified in SIVmac-infected RMs as driving disease progression have all been documented in human infection, including selective viral targeting of CCR5+ CD4+ TEM cells and rapid destruction of this compartment in acute infection (22, 35) (but with the ability to infect CD4+ TCM cells as well [47, 48]), the occurrence of generalized immune activation, and in particular, the effect of this immune activation on the turnover and differentiation of CD4+ memory T cells (including TCM cells) and on prognosis (24–26, 34, 49, 50). Moreover, the clinical manifestations of AIDS in SIVmac-infected RMs are highly analogous to those of HIV-infected humans (27, 51, 52), consistent with a similar immune deficit. The generally lower viral replication rates of HIV-infected people deplete the CD4+ TEM cell compartment less completely than in SIV-infected RMs, and the immune activation-driven production of CD4+ TEM cells is clearly better able to initially keep up with direct and indirect destruction of these T cells, as both the fraction of memory T cells among total CD4+ T cells and the fraction of CCR5+ CD4+ TEM cells among these memory cells in the blood are typically normal or elevated in HIV infection (35, 50, 53). However, although these differences may allow post-acute phase HIV-infected subjects to maintain their CD4+ TEM cell tissue compartments above the threshold for clinical immunodeficiency for a longer period of time as compared with SIV-infected RMs, the progressive loss of total CD4+ T cell counts in the blood that is the hallmark of HIV infection (1), and the extensive tissue depletion of CD4+ T cells reported at AIDS (54, 55), clearly indicate that the ability of infected humans to maintain circulating CD4+ TCM cells and their TEM cell progeny declines with time, just as described herein in SIV-infected RMs. Whether in HIV infection a parallel depletion of CD4+ naive T cells is critical for the decline of CD4+ TCM cells, or is only a correlate of the longer time to AIDS, is an open question. Thus, although the extent and/or tempo of CD4+ memory T cell depletion and viral replication are exaggerated in SIV infection compared with HIV infection, we believe the evidence strongly suggests that the fundamental pathogenetic processes are similar in these two situations.

One of the principal enigmas of AIDS pathogenesis, pertinent to both the human disease and the RM model, has been the paradoxical combination of the continuous (often high level) replication of pathogenic virus with long periods of clinical “latency” and delayed, but catastrophic, disease. Our data suggest that this paradox results from a dual nature of CCR5-tropic HIV/SIV infection: an efficient, highly destructive infection of easily replaceable CD4+ TEM cells, and a less efficient/more selective infection and much slower net destruction of precursor CD4+ TCM cells. It is the differential impact of HIV/SIV infection on the CD4+ TCM and TEM cell compartments that probably determines the typical pattern of chronic AIDS. When the TCM cell compartment remains intact (e.g., infection of natural hosts), the infection is nonpathogenic; when both compartments are efficiently targeted (e.g., dual-tropic SHIV infection), disease onset is rapid. What may be most crucial for understanding the pathogenesis of typical chronic AIDS is that although the exquisite susceptibility of the CD4+ TEM cell compartment to infection results in the most dramatic changes to the immune system, it is most likely the more covert dynamics of the CD4+ TCM cell compartment that dictate the tempo of disease progression. If these concepts are accurate, countering this second process, the slow erosion of CD4+ TCM cell homeostasis, may prove to be the most effective target of nonvirus-directed AIDS therapies. Interventions capable of preserving or rejuvenating CD4+ TCM cells might well “reset the clock” with respect to disease progression and provide significant increases in AIDS-free survival.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals and viruses.

A total of 71 purpose-bred male RMs (Macaca mulatta) of Indian genetic background and free of Cercopithicine herpesvirus 1, D type simian retrovirus, and simian T lymphotrophic virus type 1 infection were used in this study: 37 infected with wild-type SIVmac239, 19 with SIVmac239(Δnef), and 15 uninfected controls (15, 56, 57). 14 SIVmac239-infected and 4 SIVmac239(Δnef)-infected RMs were studied longitudinally for virologic or immunologic parameters or both; the remaining animals were used in one or more cross-sectional analyses. Early infection data (<200 d) on the longitudinally studied SIVmac239- and SIVmac239(Δnef)-infected RMs have been reported (15). SIVmac239 and SIVmac239(Δnef) infections were initiated with intravenous injection of 5-ng equivalents of SIV p27 (2.7–3.0 × 104 infectious centers), as described previously (15). ART consisted of daily subcutaneous injections of 30 mg/kg 9-R-(2-phosphonomethoxypropyl)adenine (tenofovir) and 30 mg/kg β-2',3′-dideoxy-3′-thia-5-fluorocytidine (emtricitabine) (58). BAL and small intestinal biopsies were performed as described previously (15). BrdU (Sigma-Aldrich) was prepared as described previously (15) and administered intravenously in three separate doses of 30 mg/kg body weight over a 24-h period. All RMs were housed at the Oregon National Primate Research Center in accordance with standards of the Center's Animal Care and Use Committee and the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (59). RMs that developed disease states that were not clinically manageable were killed in accordance with the recommendations of the Panel on Euthanasia of the American Veterinary Medical Association (60). End-stage AIDS was defined by the presence of AIDS-defining opportunistic infections, wasting syndrome unresponsive to therapy, or non-Hodgkin lymphoma (52, 61).

Viral quantification.

Plasma SIV RNA was assessed using a real-time RT-PCR assay (threshold sensitivity <100 SIV gag RNA copy Eq/ml of plasma; interassay CV ≤25%) (62, 63). Cell-associated SIV DNA was also quantified by real-time PCR (sensitivity = single copy of gag DNA) using parallel quantification of albumin gene copy number to define total cell number in a sample, as described previously (47). When no viral DNA was amplified from a given cell population, we report half the lower limit of detection (47).

Flow cytometric analysis and sorting.

PBMCs, PLN cells, BAL cells, and intestinal mucosal cells were obtained and stained for flow cytometric analysis as described previously (15, 17, 64). Six-parameter flow cytometric analysis was performed on a Becton Dickinson FACSCalibur instrument using FITC, PE, peridinin chlorophyl protein-Cy5.5 (PerCP-Cy5.5), and allophycocyanin (APC) as the four fluorescent parameters. Polychromatic (8–12 parameter) flow cytometric analysis was performed on an LSR II Becton Dickinson instrument using Pacific Blue, AmCyan, FITC, PE, PE-Texas Red, PE-Cy7, PerCP-Cy5.5, APC, APC-Cy7, and Alexa 700 as the available fluorescent parameters. Cell sorting was performed on a Becton Dickinson FACS ARIA at 70 PSI using FITC, PE, PE-Cy5, PE-Texas Red, APC, APC-Cy7, and QD-705 as fluorescent parameters. Instrument set-up, data acquisition, and sorting procedures were performed as described previously (47, 65, 66). List mode multiparameter data files were analyzed using the FlowJo software program (version 6.3.1; Tree Star, Inc.).

Memory and naive T cell subsets were delineated based on CD28, β7-integrin, CCR7, CCR5, and CD95 expression patterns on gated CD4+ or CD8+ T cells, as described previously (18, 64, 66). In brief, naive cells constitute a uniform cluster of cells with a CD28moderate, β7-integrinmoderate, CCR7moderate, CCR5−, CD95low phenotype, which is clearly distinguishable from the phenotypically diverse memory population that is predominantly CD95high and displays one or more of the following “non-naive” phenotypic features: CD28−, CCR7−, CCR5+, β7-integrinbright, or β7-integrin−/dim. All analyses included at least two of these markers (usually CD28 vs. CD95) for memory subset discrimination. The TCM and TEM cell components of the memory subset in the blood and LNs were delineated based on the phenotypic criteria shown in Fig. 6 A, with TEM referring to the combination of transitional and fully differentiated TEM cells. As we have shown that T cells in effector sites such as BAL and jejunal lamina propria are almost exclusively of the TEM cell phenotype (18), CD4+ and CD8+ T cells from these sites are generally referred to as TEM cells. For determination of CD4 representation within the naive versus memory compartments of LNs, CD4 naive and memory and CD8 naive and memory subsets were individually delineated, and Boolean gating was used to create a total naive cell and a total memory cell gate from which the percent CD4 was determined.

mAbs.

mAbs L200 (CD4; AmCyan, APC-Cy7), SP34-2 (CD3; PerCP-Cy5.5), SK1 (CD8α APC-Cy7, PerCP-Cy5.5, PE-Cy7; unconjugated), CD28.2 (CD28; PE, PerCP-Cy5.5), B56 (Ki-67; FITC, PE), B44 (anti-BrdU; FITC; APC), DX2 (CD95; PE, APC, PE-Cy7), 3A9 (CCR5; PE, APC), and FIB504 (β7-integrin, PE, PE-Cy7) were obtained from BD Biosciences. mAb 2ST8.5h7 (CD8β PE, PE-Cy7), CD28.2 (PE-Texas Red), and streptavidin–PE-Cy7 were obtained from Beckman Coulter. FN-18 (CD3) was produced and purified in house and conjugated to Pacific Blue or Alexa 700 using a conjugation kit from Invitrogen. mAb 150503 (anti-CCR7) was purchased as purified immunoglobulin from R&D Systems, conjugated to biotin using a Pierce Chemical Co. biotinylation kit, and visualized with streptavidin–Pacific Blue (Invitrogen). Purified anti-CD8 mAb was conjugated with QD705 (Invitrogen) using standard protocols (http://drmr.com/abcon).

Statistical analysis.

Linear regression analysis was used to determine the association between (a) the percentages of CD4+ T cells in BAL versus small intestinal lamina propria, and (b) percent CD4+ T cells in BAL and absolute numbers of memory cells in blood versus time, and both linear regression and Spearman rank analysis was used to evaluate the association between mean plateau-phase viral loads and time to disease. A random slope model was used to estimate the overall decay rate of percent CD4+ T cells in BAL and absolute numbers of memory cells in the blood in the study animals over time. A mixed effect model was used to determine whether the size or representation of T cell subsets in the blood or BAL significantly changed over the course of infection (preinfection to terminal disease), and if so, determination of which changes were most closely associated with disease. Unpaired t tests were used to determine the significance of differences in (a) CD4 representation in naive and memory compartments of PLNs, (b) peak and plateau BrdU labeling in SIV-infected versus uninfected monkeys, (c) the representation of cells with TEM cell differentiation among proliferating total memory T cells in progressive SIV infection versus controlled infection versus uninfected RMs, and (d) the level of SIV DNA content within the CD4+ TCM, CD8+ TCM, and CD4+ transitional memory T cell subsets of RMs in early plateau-phase versus end-stage SIV infection. Paired t tests were used to determine the significance of differences in the level of (a) SIV DNA content between the CD4+ TCM versus CD8+ TCM versus CD4+ transitional memory T cell subsets, and (b) post-ART proliferation between CD4+ and CD8+ TCM cells in PLNs. Statistical analysis was conducted with the SAS program (SAS Institute) and Statview (Abacus Concepts). p-values of <0.05 were considered significant with the Bonferroni adjustment used in situations with multiple comparisons.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank G. Bocharov and H. Alon for helpful discussions, S. Mongoue and M. Mori for statistical consultation, and M. Miller at Gilead Sciences, Inc. for provision of tenofovir and emtricitabine.

This work was supported by NIH grants RO1-AI054292, P51-RR00163, U42-RR016025, and U24-RR018107, and from National Cancer Institute funds under contract number NO1-CO-124000.

The authors have no conflicting financial interests.

Abbreviations used: ART, antiretroviral therapy; BAL, bronchoalveolar lavage; PID, postinfection day; PLN, peripheral LN; pvl, plasma viral load; RM, rhesus macaque; SHIV, simian immunodeficiency virus/HIV hybrid virus; SIV, simian immunodeficiency virus; TCM, central–memory T; TEM, effector–memory T.

References

- 1.Simon, V., D.D. Ho, and Q. Abdool Karim. 2006. HIV/AIDS epidemiology, pathogenesis, prevention, and treatment. Lancet. 368:489–504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pantaleo, G., C. Graziosi, J.F. Demarest, L. Butini, M. Montroni, C.H. Fox, J.M. Orenstein, D.P. Kotler, and A.S. Fauci. 1993. HIV infection is active and progressive in lymphoid tissue during the clinically latent stage of disease. Nature. 362:355–358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mellors, J.W., C.R. Rinaldo Jr., P. Gupta, R.M. White, J.A. Todd, and L.A. Kingsley. 1996. Prognosis in HIV-1 infection predicted by the quantity of virus in plasma. Science. 272:1167–1170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Detels, R., A. Munoz, G. McFarlane, L.A. Kingsley, J.B. Margolick, J. Giorgi, L.K. Schrager, and J.P. Phair. 1998. Effectiveness of potent antiretroviral therapy on time to AIDS and death in men with known HIV infection duration. Multicenter AIDS Cohort Study Investigators. JAMA. 280:1497–1503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Levy, J.A. 1993. Pathogenesis of human immunodeficiency virus infection. Microbiol. Rev. 57:183–289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shearer, G.M. 1998. HIV-induced immunopathogenesis. Immunity. 9:587–593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hazenberg, M.D., D. Hamann, H. Schuitemaker, and F. Miedema. 2000. T cell depletion in HIV-1 infection: how CD4+ T cells go out of stock. Nat. Immunol. 1:285–289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McCune, J.M. 2001. The dynamics of CD4+ T-cell depletion in HIV disease. Nature. 410:974–979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Douek, D.C., L.J. Picker, and R.A. Koup. 2003. T cell dynamics in HIV-1 infection. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 21:265–304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Appay, V., F. Boutboul, and B. Autran. 2005. The HIV infection and immune activation: “to fight and burn”. Curr. Infect. Dis. Rep. 7:473–479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Grossman, Z., M. Meier-Schellersheim, A.E. Sousa, R.M. Victorino, and W.E. Paul. 2002. CD4+ T-cell depletion in HIV infection: are we closer to understanding the cause? Nat. Med. 8:319–323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Grossman, Z., M. Meier-Schellersheim, W.E. Paul, and L.J. Picker. 2006. Pathogenesis of HIV infection: what the virus spares is as important as what it destroys. Nat. Med. 12:289–295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Reimann, K.A., A. Watson, P.J. Dailey, W. Lin, C.I. Lord, T.D. Steenbeke, R.A. Parker, M.K. Axthelm, and G.B. Karlsson. 1999. Viral burden and disease progression in rhesus monkeys infected with chimeric simian-human immunodeficiency viruses. Virology. 256:15–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nishimura, Y., C.R. Brown, J.J. Mattapallil, T. Igarashi, A. Buckler-White, B.A. Lafont, V.M. Hirsch, M. Roederer, and M.A. Martin. 2005. Resting naive CD4+ T cells are massively infected and eliminated by X4-tropic simian-human immunodeficiency viruses in macaques. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 102:8000–8005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Picker, L.J., S.I. Hagen, R. Lum, E.F. Reed-Inderbitzin, L.M. Daly, A.W. Sylwester, J.M. Walker, D.C. Siess, M. Piatak Jr., C. Wang, et al. 2004. Insufficient production and tissue delivery of CD4+ memory T cells in rapidly progressive simian immunodeficiency virus infection. J. Exp. Med. 200:1299–1314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sopper, S., D. Nierwetberg, A. Halbach, U. Sauer, C. Scheller, C. Stahl-Hennig, K. Matz-Rensing, F. Schafer, T. Schneider, V. ter Meulen, and J.G. Muller. 2003. Impact of simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV) infection on lymphocyte numbers and T-cell turnover in different organs of rhesus monkeys. Blood. 101:1213–1219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Veazey, R.S., K.G. Mansfield, I.C. Tham, A.C. Carville, D.E. Shvetz, A.E. Forand, and A.A. Lackner. 2000. Dynamics of CCR5 expression by CD4(+) T cells in lymphoid tissues during simian immunodeficiency virus infection. J. Virol. 74:11001–11007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Picker, L.J., E.F. Reed-Inderbitzin, S.I. Hagen, J.B. Edgar, S.G. Hansen, A. Legasse, S. Planer, M. Piatak Jr., J.D. Lifson, V.C. Maino, et al. 2006. IL-15 induces CD4 effector memory T cell production and tissue emigration in nonhuman primates. J. Clin. Invest. 116:1514–1524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Veazey, R.S., M. DeMaria, L.V. Chalifoux, D.E. Shvetz, D.R. Pauley, H.L. Knight, M. Rosenzweig, R.P. Johnson, R.C. Desrosiers, and A.A. Lackner. 1998. Gastrointestinal tract as a major site of CD4+ T cell depletion and viral replication in SIV infection. Science. 280:427–432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Haase, A.T. 2005. Perils at mucosal front lines for HIV and SIV and their hosts. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 5:783–792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brenchley, J.M., D.A. Price, and D.C. Douek. 2006. HIV disease: fallout from a mucosal catastrophe? Nat. Immunol. 7:235–239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mehandru, S., M.A. Poles, K. Tenner-Racz, A. Horowitz, A. Hurley, C. Hogan, D. Boden, P. Racz, and M. Markowitz. 2004. Primary HIV-1 infection is associated with preferential depletion of CD4+ T lymphocytes from effector sites in the gastrointestinal tract. J. Exp. Med. 200:761–770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Picker, L.J. 2006. Immunopathogenesis of acute AIDS virus infection. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 18:399–405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Deeks, S.G., C.M. Kitchen, L. Liu, H. Guo, R. Gascon, A.B. Narvaez, P. Hunt, J.N. Martin, J.O. Kahn, J. Levy, et al. 2004. Immune activation set point during early HIV infection predicts subsequent CD4+ T-cell changes independent of viral load. Blood. 104:942–947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Giorgi, J.V., L.E. Hultin, J.A. McKeating, T.D. Johnson, B. Owens, L.P. Jacobson, R. Shih, J. Lewis, D.J. Wiley, J.P. Phair, et al. 1999. Shorter survival in advanced human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection is more closely associated with T lymphocyte activation than with plasma virus burden or virus chemokine coreceptor usage. J. Infect. Dis. 179:859–870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hazenberg, M.D., S.A. Otto, B.H. van Benthem, M.T. Roos, R.A. Coutinho, J.M. Lange, D. Hamann, M. Prins, and F. Miedema. 2003. Persistent immune activation in HIV-1 infection is associated with progression to AIDS. AIDS. 17:1881–1888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hirsch, V.M., and J.D. Lifson. 2000. Simian immunodeficiency virus infection of monkeys as a model system for the study of AIDS pathogenesis, treatment, and prevention. Adv. Pharmacol. 49:437–477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Grossman, Z., B. Min, M. Meier-Schellersheim, and W.E. Paul. 2004. Concomitant regulation of T-cell activation and homeostasis. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 4:387–395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Appay, V., J.R. Almeida, D. Sauce, B. Autran, and L. Papagno. 2007. Accelerated immune senescence and HIV-1 infection. Exp. Gerontol. 42:432–437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mattapallil, J.J., D.C. Douek, B. Hill, Y. Nishimura, M. Martin, and M. Roederer. 2005. Massive infection and loss of memory CD4+ T cells in multiple tissues during acute SIV infection. Nature. 434:1093–1097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Li, Q., L. Duan, J.D. Estes, Z.M. Ma, T. Rourke, Y. Wang, C. Reilly, J. Carlis, C.J. Miller, and A.T. Haase. 2005. Peak SIV replication in resting memory CD4+ T cells depletes gut lamina propria CD4+ T cells. Nature. 434:1148–1152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Brenchley, J.M., D.A. Price, T.W. Schacker, T.E. Asher, G. Silvestri, S. Rao, Z. Kazzaz, E. Bornstein, O. Lambotte, D. Altmann, et al. 2006. Microbial translocation is a cause of systemic immune activation in chronic HIV infection. Nat. Med. 12:1365–1371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nishimura, Y., T. Igarashi, A. Buckler-White, C. Buckler, H. Imamichi, R.M. Goeken, W.R. Lee, B.A. Lafont, R. Byrum, H.C. Lane, et al. 2007. Loss of naive cells accompanies memory CD4+ T-cell depletion during long-term progression to AIDS in Simian immunodeficiency virus-infected macaques. J. Virol. 81:893–902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hellerstein, M.K., R.A. Hoh, M.B. Hanley, D. Cesar, D. Lee, R.A. Neese, and J.M. McCune. 2003. Subpopulations of long-lived and short-lived T cells in advanced HIV-1 infection. J. Clin. Invest. 112:956–966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Brenchley, J.M., T.W. Schacker, L.E. Ruff, D.A. Price, J.H. Taylor, G.J. Beilman, P.L. Nguyen, A. Khoruts, M. Larson, A.T. Haase, and D.C. Douek. 2004. CD4+ T cell depletion during all stages of HIV disease occurs predominantly in the gastrointestinal tract. J. Exp. Med. 200:749–759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rodriguez, B., A.K. Sethi, V.K. Cheruvu, W. Mackay, R.J. Bosch, M. Kitahata, S.L. Boswell, W.C. Mathews, D.R. Bangsberg, J. Martin, et al. 2006. Predictive value of plasma HIV RNA level on rate of CD4 T-cell decline in untreated HIV infection. JAMA. 296:1498–1506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Friedrich, T.C., L.E. Valentine, L.J. Yant, E.G. Rakasz, S.M. Piaskowski, J.R. Furlott, K.L. Weisgrau, B. Burwitz, G.E. May, E.J. Leon, et al. 2007. Subdominant CD8+ T-cell responses are involved in durable control of AIDS virus replication. J. Virol. 81:3465–3476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Staprans, S.I., P.J. Dailey, A. Rosenthal, C. Horton, R.M. Grant, N. Lerche, and M.B. Feinberg. 1999. Simian immunodeficiency virus disease course is predicted by the extent of virus replication during primary infection. J. Virol. 73:4829–4839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Smith, S.M., B. Holland, C. Russo, P.J. Dailey, P.A. Marx, and R.I. Connor. 1999. Retrospective analysis of viral load and SIV antibody responses in rhesus macaques infected with pathogenic SIV: predictive value for disease progression. AIDS Res. Hum. Retroviruses. 15:1691–1701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schacker, T.W., P.L. Nguyen, G.J. Beilman, S. Wolinsky, M. Larson, C. Reilly, and A.T. Haase. 2002. Collagen deposition in HIV-1 infected lymphatic tissues and T cell homeostasis. J. Clin. Invest. 110:1133–1139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Letvin, N.L., J.R. Mascola, Y. Sun, D.A. Gorgone, A.P. Buzby, L. Xu, Z.Y. Yang, B. Chakrabarti, S.S. Rao, J.E. Schmitz, et al. 2006. Preserved CD4+ central memory T cells and survival in vaccinated SIV-challenged monkeys. Science. 312:1530–1533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hirsch, V.M. 2004. What can natural infection of African monkeys with simian immunodeficiency virus tell us about the pathogenesis of AIDS. AIDS Rev. 6:40–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.VandeWoude, S., and C. Apetrei. 2006. Going wild: lessons from naturally occurring T-lymphotropic lentiviruses. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 19:728–762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Silvestri, G., D.L. Sodora, R.A. Koup, M. Paiardini, S.P. O'Neil, H.M. McClure, S.I. Staprans, and M.B. Feinberg. 2003. Nonpathogenic SIV infection of sooty mangabeys is characterized by limited bystander immunopathology despite chronic high-level viremia. Immunity. 18:441–452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Silvestri, G., A. Fedanov, S. Germon, N. Kozyr, W.J. Kaiser, D.A. Garber, H. McClure, M.B. Feinberg, and S.I. Staprans. 2005. Divergent host responses during primary simian immunodeficiency virus SIVsm infection of natural sooty mangabey and nonnatural rhesus macaque hosts. J. Virol. 79:4043–4054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pandrea, I., C. Apetrei, J. Dufour, N. Dillon, J. Barbercheck, M. Metzger, B. Jacquelin, R. Bohm, P.A. Marx, F. Barre-Sinoussi, et al. 2006. Simian immunodeficiency virus SIVagm.sab infection of Caribbean African green monkeys: a new model for the study of SIV pathogenesis in natural hosts. J. Virol. 80:4858–4867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Brenchley, J.M., B.J. Hill, D.R. Ambrozak, D.A. Price, F.J. Guenaga, J.P. Casazza, J. Kuruppu, J. Yazdani, S.A. Migueles, M. Connors, et al. 2004. T-cell subsets that harbor human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) in vivo: implications for HIV pathogenesis. J. Virol. 78:1160–1168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Harari, A., G.P. Rizzardi, K. Ellefsen, D. Ciuffreda, P. Champagne, P.A. Bart, D. Kaufmann, A. Telenti, R. Sahli, G. Tambussi, et al. 2002. Analysis of HIV-1- and CMV-specific memory CD4 T-cell responses during primary and chronic infection. Blood. 100:1381–1387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sieg, S.F., B. Rodriguez, R. Asaad, W. Jiang, D.A. Bazdar, and M.M. Lederman. 2005. Peripheral S-phase T cells in HIV disease have a central memory phenotype and rarely have evidence of recent T cell receptor engagement. J. Infect. Dis. 192:62–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Oswald-Richter, K., S.M. Grill, M. Leelawong, M. Tseng, S.A. Kalams, T. Hulgan, D.W. Haas, and D. Unutmaz. 2007. Identification of a CCR5-expressing T cell subset that is resistant to R5-tropic HIV infection. PLoS Pathog. 3:e58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Simon, M.A., S.J. Brodie, V.G. Sasseville, L.V. Chalifoux, R.C. Desrosiers, and D.J. Ringler. 1994. Immunopathogenesis of SIVmac. Virus Res. 32:227–251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Letvin, N.L., and N.W. King. 1990. Immunologic and pathologic manifestations of the infection of rhesus monkeys with simian immunodeficiency virus of macaques. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 3:1023–1040. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Soares, R., R. Foxall, A. Albuquerque, C. Cortesao, M. Garcia, R.M. Victorino, and A.E. Sousa. 2006. Increased frequency of circulating CCR5+ CD4+ T cells in human immunodeficiency virus type 2 infection. J. Virol. 80:12425–12429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Clayton, F., G. Snow, S. Reka, and D.P. Kotler. 1997. Selective depletion of rectal lamina propria rather than lymphoid aggregate CD4 lymphocytes in HIV infection. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 107:288–292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Miao, Y.M., P.J. Hayes, F.M. Gotch, M.C. Barrett, N.D. Francis, and B.G. Gazzard. 2002. Elevated mucosal addressin cell adhesion molecule-1 expression in acquired immunodeficiency syndrome is maintained during antiretroviral therapy by intestinal pathogens and coincides with increased duodenal CD4 T cell densities. J. Infect. Dis. 185:1043–1050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lewis, M.G., S. Bellah, K. McKinnon, J. Yalley-Ogunro, P.M. Zack, W.R. Elkins, R.C. Desrosiers, and G.A. Eddy. 1994. Titration and characterization of two rhesus-derived SIVmac challenge stocks. AIDS Res. Hum. Retroviruses. 10:213–220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Gibbs, J.S., D.A. Regier, and R.C. Desrosiers. 1994. Construction and in vitro properties of SIVmac mutants with deletions in “nonessential” genes. AIDS Res. Hum. Retroviruses. 10:607–616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Shen, A., M.C. Zink, J.L. Mankowski, K. Chadwick, J.B. Margolick, L.M. Carruth, M. Li, J.E. Clements, and R.F. Siliciano. 2003. Resting CD4+ T lymphocytes but not thymocytes provide a latent viral reservoir in a simian immunodeficiency virus-Macaca nemestrina model of human immunodeficiency virus type 1-infected patients on highly active antiretroviral therapy. J. Virol. 77:4938–4949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Institute for Laboratory Animal Research. 1996. Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. National Academic Press, Washington, D.C.

- 60.Panel on Euthanasia, American Veterinary Medical Association. 2001. 2000 Report of the AVMA Panel on Euthanasia. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 218:669–696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.McClure, H.M., D.C. Anderson, P.N. Fultz, A.A. Ansari, E. Lockwood, and A. Brodie. 1989. Spectrum of disease in macaque monkeys chronically infected with SIV/SMM. Vet. Immunol. Immunopathol. 21:13–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lifson, J.D., J.L. Rossio, M. Piatak Jr., T. Parks, L. Li, R. Kiser, V. Coalter, B. Fisher, B.M. Flynn, S. Czajak, et al. 2001. Role of CD8(+) lymphocytes in control of simian immunodeficiency virus infection and resistance to rechallenge after transient early antiretroviral treatment. J. Virol. 75:10187–10199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Cline, A.N., J.W. Bess, M. Piatak Jr., and J.D. Lifson. 2005. Highly sensitive SIV plasma viral load assay: practical considerations, realistic performance expectations, and application to reverse engineering of vaccines for AIDS. J. Med. Primatol. 34:303–312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Pitcher, C.J., S.I. Hagen, J.M. Walker, R. Lum, B.L. Mitchell, V.C. Maino, M.K. Axthelm, and L.J. Picker. 2002. Development and homeostasis of T cell memory in rhesus macaque. J. Immunol. 168:29–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]