Abstract

Most T cells belong to either of two lineages defined by the mutually exclusive expression of CD4 and CD8 coreceptors: CD4 T cells are major histocompatibility complex (MHC) II restricted and have helper function, whereas CD8 T cells are MHC I restricted and have cytotoxic function. The divergence between these two lineages occurs during intrathymic selection and is thought to be irreversible in mature T cells. It is, however, unclear whether the CD4-CD8 differentiation of postthymic T cells retains some level of plasticity or is stably maintained by mechanisms distinct from those that set lineage choice in the thymus. To address this issue, we examined if coreceptor or effector gene expression in mature CD8 T cells remains sensitive to the zinc finger transcription factor cKrox, which promotes CD4 and inhibits CD8 differentiation when expressed in thymocytes. We show that cKrox transduction into CD8 T cells inhibits their expression of CD8 and cytotoxic effector genes and impairs their cytotoxic activity, and that it promotes expression of helper-specific genes, although not of CD4 itself. These observations reveal a persistent degree of plasticity in CD4-CD8 differentiation in mature T cells.

An emerging concept is that cell differentiation is maintained at least in part by inheritable changes in DNA or chromatin organization, referred to as epigenetic modifications (1). In the lymphoid system, epigenetic control of gene expression is epitomized by the perpetuation of CD4 silencing in postthymic CD8 T cells independently from the genetic elements needed to establish silencing in differentiating CD8 thymocytes (2–5). CD8 T cells are restricted by MHC I molecules and possess cytotoxic activity by direct target cell lysis or through secretion of IFN-γ (6). In contrast, CD4 cells, which are MHC II restricted, generally provide help to other immune cells through cytokine secretion and expression of specific surface molecules. Because epigenetic marking affects the expression of multiple lineage-specific genes in mature T cells, including CD4, CD8, and type 2 effector cytokines such as IL-4 (1, 7–9), it is conceivable that such mechanisms lock CD4-CD8 lineage differentiation after exit from the thymus. A direct correlate of this hypothesis is that CD4-CD8 differentiation in mature T cells should no longer be affected by the transcription factors that direct lineage choice in thymocytes. Because the nuclear effectors that direct lineage choice during positive selection in the thymus were unknown, this prediction remains to be evaluated.

The zinc finger transcription factor cKrox (also called Zbtb7b or Thpok) is a master switch of CD4 differentiation. It is induced during MHC II–induced positive selection, promotes CD4 and helper differentiation (10, 11), and is necessary for CD4 T cell generation (10). Here, we exploited these findings to evaluate how “plastic” lineage-specific gene expression remained in postthymic T cells. We found that introducing cKrox into CD8 T cells, in which it is normally not expressed, inhibited their expression of CD8 coreceptor and cytotoxic effector genes, and up-regulated genes characteristic of helper differentiation, although not of CD4 itself. These findings reveal a substantial plasticity in the CD4-CD8 lineage differentiation of mature T cells.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

To evaluate the “plasticity” of CD4-CD8 differentiation in postthymic T cells, we used a GFP-based retrovirus (Fig. S1 A, available at http://www.jem.org/cgi/content/full/jem.20061982/DC1) to introduce cKrox into CD8 cells, in which it is normally not expressed. Immunoblot analyses detected the cKrox protein in GFP+ CD8 T cells transduced by the cKrox vector but not in GFP+ cells transduced with a control vector lacking the cKrox insert (Fig. S1 B).

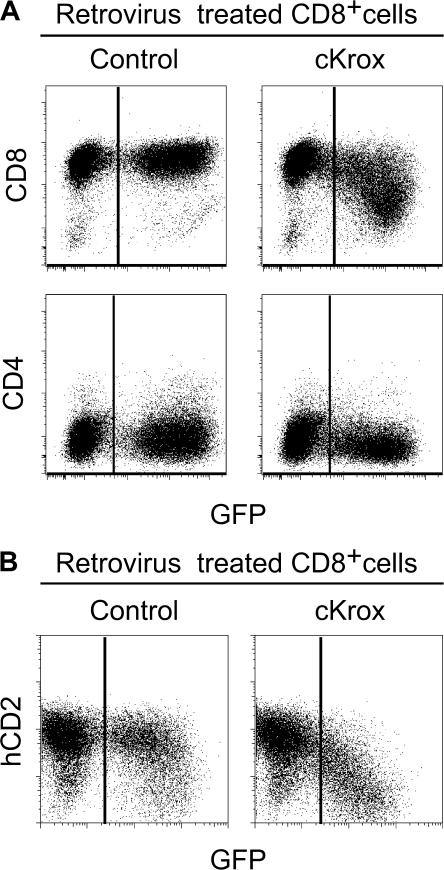

We first assessed the effect of cKrox on coreceptor expression. Although cKrox-transduced CD8 T cells did not reexpress CD4, their CD8 expression was reduced compared with nontransduced or control-transduced cells (Fig. 1 A). To examine if this effect was transcriptional, we evaluated if cKrox affected the activity of the E8(I) CD8 enhancer element, unique among the five known CD8 enhancers for being active in mature CD8 T cells only (2, 9, 12, 13). Mice carrying an E8(I)-driven human CD2 (hCD2) cDNA transgene expressed the hCD2 reporter in CD8 T cells but not in double positive thymocytes or CD4 T cells (13 and not depicted). Retroviral transduction of cKrox in E8(I)-hCD2 transgenic CD8 T cells markedly reduced hCD2 expression (Fig. 1 B), demonstrating that cKrox-mediated CD8 repression is transcriptional. These observations identify E8(I) as a direct or indirect target of cKrox.

Figure 1.

cKrox inhibits CD8 transcription in mature CD8 T cells. (A) CD4-depleted splenocytes transduced with either control (left) or cKrox (right) supernatants were analyzed for GFP and for CD4 and CD8 surface expression by flow cytometry. Two parameter dot plots gated on all live cells are shown. The mean fluorescence intensity of CD8 staining was 3,735 in control- and 867 in cKrox-transduced cells. Results are representative of more than five experiments. (B) T cells from E8(I)-hCD2 reporter mice were transduced with either control or cKrox retrovirus and analyzed by flow cytometry for GFP, hCD2, CD4, and CD8 expression. Two parameter dot plots gated on CD8+ cells are shown. Results are representative of three experiments performed on three distinct founder-derived lines, all with CD8-specific hCD2 expression.

The repression of E8(I) by cKrox was dose dependent, as cells with high cKrox expression (assessed from GFP levels) failed to express hCD2 (Fig. 1 B). In contrast, the repression of endogenous CD8 expression by cKrox was not as clearly dose dependent, as CD8 levels were broadly distributed on GFPhi cKrox-transduced cells (Fig. 1 A). It is possible that additional CD8 enhancers are not repressed by cKrox, or not as strongly as E8(I). However, a more intriguing possibility is that the broad distribution of CD8 levels on GFPhi cKrox-transduced cells is caused by variegation, a pattern typical of epigenetic silencing (9), raising the possibility that epigenetic silencing of CD8 is initiated in postthymic cells as a consequence of repression by cKrox.

cKrox impairs expression of cytotoxic genes in peripheral CD8 T cells

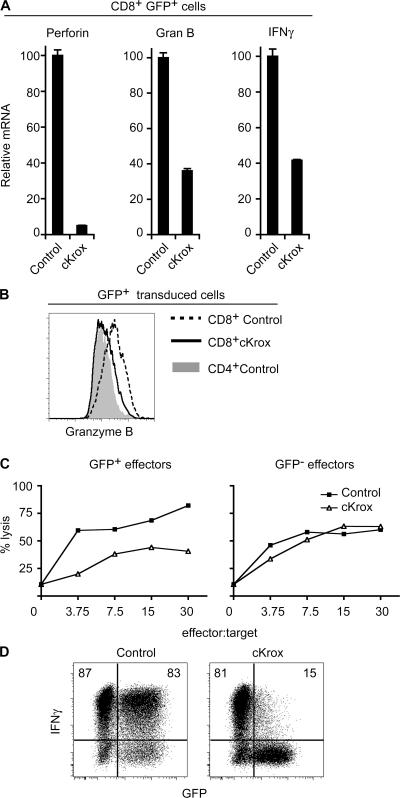

That cKrox impaired CD8 expression in postthymic T cells prompted us to examine whether cKrox would repress cytotoxic effector genes normally expressed in CD8 but not CD4 cells (14). Real-time PCR amplification of reverse-transcribed cDNAs (RT-PCR) showed that cKrox transduction reduced the expression of genes encoding the cytotoxic effectors perforin and granzyme B (Fig. 2 A). Flow cytometric analyses confirmed that cKrox impaired granzyme B protein expression (Fig. 2 B). In agreement with these findings, transduction of cKrox in mature CD8 T cells carrying the Db-restricted P14 TCR transgene impaired their ability to lyse targets cells loaded with their cognate lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus (LCMV) gp33 peptide (Fig. 2 C and Figs. S2 and S3, which are available at http://www.jem.org/cgi/content/full/jem.20061982/DC1).

Figure 2.

cKrox represses cytotoxic effector gene expression and function in CD8 T cells. (A) Expression of perforin, granzyme B (Gran B), and IFN-γ genes was analyzed by RT-PCR in sorted GFP+ CD8 T cells 3 d after transduction with control or cKrox retrovirus. Results are presented relative to gene expression in control-transduced cells (arbitrarily set to 100 for each gene). (B) Analyses of granzyme B protein expression by intracellular staining and flow cytometry are depicted by overlaid histograms showing staining of cKrox- or control-transduced CD8+ T cells or of control-transduced CD4 T cells. (C) cKrox impairs CD8 cell cytotoxicity. P14 TCR T cells transduced with either control or cKrox retroviruses were sorted for GFP expression and assessed for cytotoxicity against LCMV gp33-loaded EL-4 targets labeled with the DiD Vybrant Dye (see Fig. S3 for gating strategy). Graphs plot the percentage of targets lysed (7-AAD+) by infected (GFP+) or uninfected (GFP−) effectors against effector/target ratios. (D) CD4-depleted splenocytes transduced with either control (left) or cKrox (right) retrovirus were restimulated for 4 h by PMA and ionomycin, and analyzed for GFP and IFN-γ expression by intracellular cytokine staining and flow cytometry. Numbers indicate the percentage of GFP− or GFP+ cells that stained for intracellular IFN-γ. Results in each panel are representative of three or more experiments.

We next examined whether cKrox transduction affected production of IFN-γ, a cytokine produced at high levels by CD8 T cells (14). These experiments were performed on cells activated in type 2 conditions that are permissive to IFN-γ production by CD8 but not by CD4 T cells. cKrox reduced CD8 cell expression of IFN-γ both at the mRNA and protein levels (Fig. 2, A and D). This effect was cell autonomous, as IFN-γ production was not reduced in uninfected (GFP−) CD8 cells in the same culture as cKrox-infected cells (GFP+). Thus, cKrox represses the expression of three distinct CD8 lineage markers, namely the CD8 coreceptor itself, cytotoxic genes such as perforin and granzyme B, and the cytokine IFN-γ.

cKrox inhibits the expression of a key regulator of CD8 differentiation

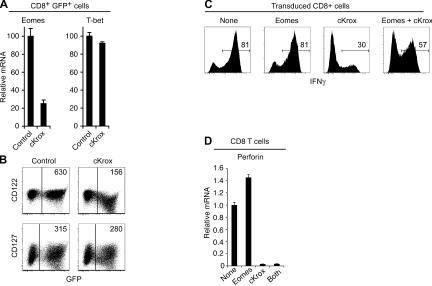

The inhibition by cKrox of IFN-γ production was unexpected, as CD4 T cells can differentiate into type 1 (Th1) effectors that produce IFN-γ. Two T-box transcription factors, eomesodermin (Eomes) and T-bet, control T cell expression of IFN-γ (14–16). Both factors are expressed in CD8 T cells, whereas T-bet is primarily responsible for Th1 CD4 T cell commitment (17). Thus, we considered the possibility that cKrox was impairing IFN-γ production in CD8 T cells by repressing Eomes. Indeed, cKrox transduction in CD8 T cells reduced Eomes mRNA levels to <25% of those in control-transduced cells but had essentially no effect on T-bet expression (Fig. 3 A). Furthermore, cKrox transduction reduced expression of IL-2Rβ (CD122), a target of Eomes in CD8 T cells (18) (Fig. 3 B). In contrast, cKrox did not affect expression of IL-7Rα (CD127), a receptor normally expressed on both CD4 and CD8 T cells (Fig. 3 B).

Figure 3.

cKrox-induced Eomes repression mediates in part its reduction of IFN-γ production. (A) cKrox represses Eomes but not T-bet expression. Sorted GFP+CD8+ cells were analyzed as in Fig. 2 A for Eomes and T-bet gene expression. (B) cKrox- or control-transduced CD4-depleted splenocytes were analyzed by flow cytometry for CD122 and CD127 surface expression. Two parameter dot plots are gated on all live cells. Numbers represent mean fluorescence intensity of CD122 or CD127 expression in GFP+ cells. Results are representative of three experiments. (C and D) CD4-depleted splenocytes were cotransduced with Eomes-NGFR and cKrox-GFP viruses. 3 d later, flow cytometric analysis of CD8, NGFR, and GFP expression distinguishes CD8 cells infected with either the Eomes or cKrox virus, with both viruses (both), and uninfected CD8 cells (none), as depicted in Fig. S4 A. (C) Analyses of IFN-γ production by intracellular cytokine staining are shown as single-parameter histograms gated on each population. Numbers represent the percent of cells producing IFN-γ. (D) Perforin gene expression was analyzed by RT-PCR on sorted cells from each population and is expressed relative to uninfected cells (set to 1 arbitrarily). Results in each panel are representative of two separate transductions.

These findings supported the hypothesis that cKrox impairs IFN-γ production by reducing Eomes expression. If that were the case, enforced coexpression of Eomes with cKrox should restore IFN-γ production to levels normally observed in CD8 T cells. To evaluate this prediction, we cotransduced CD8 T cells with retroviruses encoding cKrox–internal ribosome entry site (IRES)-GFP or an Eomes-IRES–nerve growth factor receptor (NGFR) cassette (19). Cell infection with this virus was detected through surface expression of the truncated NGFR protein (Fig. S4 A, available at http://www.jem.org/cgi/content/full/jem.20061982/DC1) and resulted in a modest increase in Eomes expression compared with nontransduced cells (Fig. S4 B). Cells coinfected by both Eomes and cKrox viruses had greater expression of IFN-γ than cells infected with cKrox alone (Fig. 3 C). This supported the conclusion that cKrox impairs IFN-γ production in part by reducing Eomes expression. However, IFN-γ production by Eomes-cKrox–coinfected cells did not reach levels observed in uninfected or Eomes-only–infected cells. This suggested that additional mechanisms, independent from or downstream of Eomes, contributed to the repression by cKrox of IFN-γ or cytotoxic genes. Supporting this possibility, cotransduction of Eomes did not prevent the repression of perforin by cKrox (Fig. 3 D). We conclude from these experiments that cKrox inhibits cytotoxic gene expression both by repressing Eomes expression and through additional mechanisms that circumvent the functional redundancy between Eomes and T-bet.

Unlike disruption of T-bet and Eomes function (18), cKrox expression represses CD8, implying that the spectrum of cKrox targets extends beyond that of Eomes. As cKrox belongs to a family of proteins that generally act as transcriptional repressors, it is possible that it represses CD8 or effector genes directly by binding to their cis-regulatory elements. Another nonmutually exclusive possibility is that cKrox impairs the expression or function of a so far unknown regulator of CD8 differentiation that would act upstream of T-box proteins and thereby control the expression of CD8 and Eomes.

Retroviral expression of cKrox promotes helper-specific gene expression.

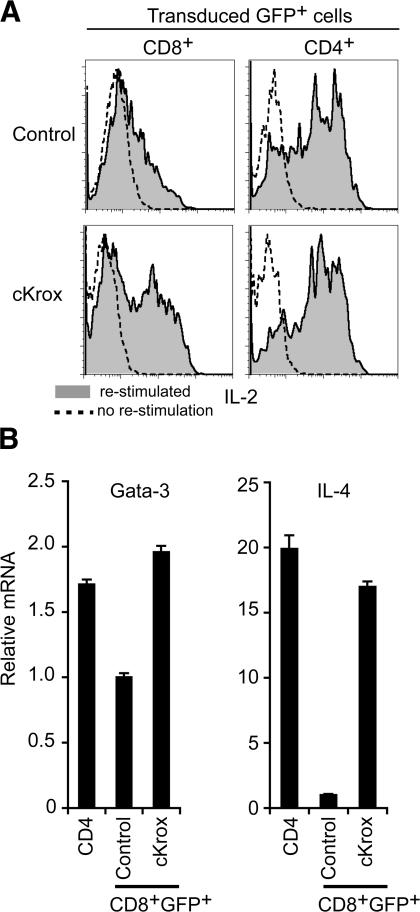

As cKrox represses CD8 lineage genes, we examined if, conversely, it would induce helper-type gene expression. We first assessed its effect on IL-2, a cytokine produced by activated CD4 T cells independently of type 1 or 2 effector differentiation (6). Intracellular cytokine staining and flow cytometry showed that cKrox transduction into CD8 T cells promoted IL-2 production (Fig. 4 A). Another hallmark of CD4 cells is their high expression of Gata3, a transcription factor required for the production of type 2 cytokines such as IL-4 (20–22). cKrox transduction into CD8 cells cultured in type 2 conditions increased mRNA expression of Gata3 and of its target IL-4 (Fig. 4 B).

Figure 4.

cKrox promotes expression of helper-specific genes by CD8 T cells. (A) Lymph node cells transduced with cKrox or control retrovirus were analyzed by intracellular staining and flow cytometry for IL-2 production. Overlaid histograms gated on CD8+GFP+ (left) or CD4+GFP+ (right) cells show IL-2 expression after restimulation with PMA and ionomycin (filled) or without restimulation (dotted line). (B) mRNA expression of Gata3 and IL-4 was analyzed by RT-PCR in cKrox- or control-transduced CD8 cells and in untransduced CD4 cells, all activated in type 2 conditions. Results are relative to control-transduced CD8 cells (arbitrarily set to 1). Results in each panel are representative of three experiments.

Thus, cKrox expression in CD8 T cells induces genes typical of helper differentiation. However, cKrox-transduced CD8 cells had lower IL-2 expression than CD4 cells present in the same cultures (Fig. 4 A). Furthermore, although the levels of IL-4 and Gata3 mRNAs in cKrox-transduced CD8 cells were within the range observed in control CD4 cells (Fig. 4 B), cKrox-transduced CD8 cells failed to produce detectable IL-4 protein (not depicted). We conclude from these experiments that cKrox induces helper-specific genes in CD8 T cells, although it does not cause a complete conversion from cytotoxic to helper differentiation. cKrox-mediated gene up-regulation does not exclude that cKrox primarily acts as a transcriptional repressor, as it could promote helper-specific gene expression through indirect “repression of repressor” circuits. Notably, it is possible that Eomes repression in cKrox-transduced cells contributes to their increased expression of helper-specific genes, as cotransduction of Eomes and cKrox failed to up-regulate Gata3 or IL-4, unlike transduction of cKrox only (Fig. 4 B and not depicted). Such indirect gene cascades could conceivably be less responsive to cKrox than direct gene repression, contributing to limit the up-regulation of helper-specific genes in cKrox-transduced CD8 cells.

In summary, this study identifies functional targets of the zinc finger transcription factor cKrox, including the mature cell–specific E8(I) CD8 enhancer and the key regulator of cytotoxic differentiation Eomes. It shows that cKrox impairs cytotoxic effector differentiation through both Eomes-dependent and -independent mechanisms. These observations demonstrate that the genetic program of CD8 cells remains sensitive to cKrox after these cells exit the thymus, rather than being locked in a configuration constitutively permissive to cytotoxic gene expression. This implies that cKrox must be permanently repressed in CD8 cells to maintain CD8 expression and to preserve their cytotoxic effector function.

Recent findings suggest that epigenetic changes in DNA or chromatin structure are key to perpetuate CD4-CD8 lineage–specific gene expression in postthymic T cells (1, 3, 23–25). Notably, the maintenance of CD4 silencing in CD8 cells may involve repositioning of unexpressed coreceptor loci to heterochromatin (7, 8), whereas type 2 cytokine expression in CD8 cells is repressed in part by DNA methylation (23, 24). Although epigenetic changes at the coreceptor or effector gene level are essential to maintain lineage separation, our findings demonstrate that key aspects of lineage-specific gene expression remain under the dynamic control of transcription factors. The induction of CD4-specific genes by cKrox shows that such plasticity is not limited to genes actively expressed in CD8 cells, despite the constraints to transcription factor access thought to be imposed by epigenetic changes at helper-specific loci in CD8 cells (23, 24).

This study reveals a persistent plasticity in gene expression after the divergence of CD4 and CD8 lineages, reminiscent of the persistent dependence of B cell–specific gene expression on Pax5, a transcription factor key to the emergence of the B cell lineage in hematopoietic precursors (26). Future experiments will assess whether cKrox disruption in mature CD4 T cells results in a loss of CD4 helper differentiation and whether cKrox affects epigenetic chromatin modifications. Finally, this study provides a proof of principle that genetic approaches can dissociate functional differentiation from MHC antigen specificity in mature T cells. Although the identification of cKrox targets will be required for further progress in this direction, our findings open new perspectives for disabling pathologic cytotoxic properties or endowing MHC I–restricted T cells with helper function.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell culture and stimulation.

Peripheral T cells from lymph nodes, spleens, or both were obtained from wild-type (C57BL/6) or E8(I) reporter mice, depleted of B cells using anti–mouse IgG-coated beads (Polysciences) or of CD4 T cells using Dynal beads, and stimulated by either 5 μg/ml of plastic-coated anti-CD3, 1 μg/ml of soluble anti-CD28, and 50 U/ml IL-2, or by 1 μg/ml of soluble anti-CD3 and 2 μg/ml anti-CD28 in the presence of 5 μg/ml anti–IL-12 and 5 U/ml IL-4 (Th2 conditions). E8(I) reporter mice (Fig. 1 B) were newly generated according to published procedures (27) using a previously reported construct (Tg-b) (13). P14 TCR transgenic mice were originally obtained from Taconic Farms. Animal procedures used in this study were approved by the NCI Animal Care and Use Committee.

Measurements of cytotoxic activity.

P14 TCR T cells were activated by mitomycin C–treated H-2b splenocytes pulsed with LCMV gp 33 (KAVYNFATC) and transduced with either cKrox or control retrovirus. 3 d after transduction, effector cells were sorted for GFP expression and rested overnight in the presence of 50 U/ml IL-2. EL-4 targets were loaded with 10−7 M gp33, labeled with DiD Vybrant dye (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's instructions, and cocultured with rested effectors at various effector/target ratios. Cell death was assessed by flow cytometry after the addition of 1 mg/l 7-AAD and is expressed as a percentage of 7-AAD+ events among DiD+ GFP− cells (Fig. S3). Assessments of CD107a externalization are described in the legend to Fig. S2.

Gene and protein expression analyses.

Cells were stained 3 d after retroviral transduction using published procedures (11). Cytokine staining was performed after a 4-h PMA-ionomycin restimulation using the Cytofix/Cytoperm kit (Becton Dickinson). Cell fluorescence was measured on either a two-laser FACSCalibur or an LSRII (both from BD Biosciences). Antibodies were from Caltag or BD Biosciences.

For RT-PCR analyses, cells were sorted with a FACSVantage (BD Biosciences), and RNA was extracted with Trizol (Invitrogen) and reverse-transcribed with random hexamers. An ABI PRISM 7900HT sequence detection system (Applied Biosystems) was used for quantitative real-time PCR according to the manufacturer's instructions using previously published primer and probe sets (18). Gene expression values are normalized to HPRT in the same sample. Analyses of cKrox protein expression in transduced cells were performed as described previously (11).

Retrovirus construction and transduction.

A pMRX-based bicistronic retrovirus (28) expressing cKrox upstream of an IRES and GFP was constructed and transfected into packaging cells (29) to produce retroviral supernatants (detailed procedures available on request). 1 d after activation, cells were resuspended in 1 ml of retroviral supernatant containing 20 μg polybrene (Chemicon International), centrifuged at 6,000 g for 90 min at 25°C, and placed into fresh media containing the same cytokines as used in the initial stimulation.

Online supplemental material.

Fig. S1 shows a schematic of the control and cKrox retroviruses and expression levels of cKrox in retrovirus-transduced cells as analyzed by immunoprecipitation and immunoblotting. Fig. S2 shows the reduced externalization of the cytotoxic granule membrane protein CD107a in cKrox-transduced CD8 T cells compared with control-transduced cells. Fig. S3 depicts the gating strategy used for flow cytometry–based cytotoxicity assays shown in Fig. 2 C. Fig. S4 A shows the flow cytometric gating and sorting of cells cotransduced with the cKrox (GFP) and Eomes (NGFR) retroviruses analyzed in Fig. 3 (C and D). Fig. S4 B compares the expression of endogenous Eomes mRNA in uninfected CD8 T cells and in CD8 T cells expressing retrovirally transduced Eomes, cKrox, or both. Figs. S1–S4 are available at http://www.jem.org/cgi/content/full/jem.20061982/DC1.

Supplemental Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Wilfried Ellmeier and Dan Littman for the E8(I) transgenic vector, Barbara Taylor for cell sorting, and Jon Ashwell, Pam Schwartzberg, Al Singer, and S. Murty Srinivasula for reading the manuscript.

This work was supported by the intramural program of the NCI, Center for Cancer Research, and by extramural NIH support grant AI053827.

The authors have no conflicting financial interests.

G. Sun's present address is Dept. of Immunology, CD&I, Walter Reed Army Institute of Research, Silver Spring, MD 20910.

References

- 1.Wilson, C.B., K.W. Makar, M. Shnyreva, and D.R. Fitzpatrick. 2005. DNA methylation and the expanding epigenetics of T cell lineage commitment. Semin. Immunol. 17:105–119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Taniuchi, I., W. Ellmeier, and D.R. Littman. 2004. The CD4/CD8 lineage choice: new insights into epigenetic regulation during T cell development. Adv. Immunol. 83:55–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zou, Y.R., M.J. Sunshine, I. Taniuchi, F. Hatam, N. Killeen, and D.R. Littman. 2001. Epigenetic silencing of CD4 in T cells committed to the cytotoxic lineage. Nat. Genet. 29:332–336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Grueter, B., M. Petter, T. Egawa, K. Laule-Kilian, C.J. Aldrian, A. Wuerch, Y. Ludwig, H. Fukuyama, H. Wardemann, R. Waldschuetz, et al. 2005. Runx3 regulates integrin{alpha}E/CD103 and CD4 expression during development of CD4−/CD8+ T cells. J. Immunol. 175:1694–1705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Telfer, J.C., E.E. Hedblom, M.K. Anderson, M.N. Laurent, and E.V. Rothenberg. 2004. Localization of the domains in runx transcription factors required for the repression of CD4 in thymocytes. J. Immunol. 172:4359–4370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jenkins, M. 2003. Peripheral T-lymphocyte responses and function. In Fundamental Immunology. W.E. Paul, editor. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia. 310–315.

- 7.Delaire, S., Y.H. Huang, S.W. Chan, and E.A. Robey. 2004. Dynamic repositioning of CD4 and CD8 genes during T cell development. J. Exp. Med. 200:1427–1435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Merkenschlager, M., S. Amoils, E. Roldan, A. Rahemtulla, E. O'Connor, A.G. Fisher, and K.E. Brown. 2004. Centromeric repositioning of coreceptor loci predicts their stable silencing and the CD4/CD8 lineage choice. J. Exp. Med. 200:1437–1444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kioussis, D., and W. Ellmeier. 2002. Chromatin and CD4, CD8A and CD8B gene expression during thymic differentiation. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2:909–919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.He, X., X. He, V.P. Dave, Y. Zhang, X. Hua, E. Nicolas, W. Xu, B.A. Roe, and D.J. Kappes. 2005. The zinc finger transcription factor Th-POK regulates CD4 versus CD8 T-cell lineage commitment. Nature. 433:826–833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sun, G., X. Liu, P. Mercado, S.R. Jenkinson, M. Kypriotou, L. Feigenbaum, P. Galera, and R. Bosselut. 2005. The zinc finger protein cKrox directs CD4 lineage differentiation during intrathymic T cell positive selection. Nat. Immunol. 6:373–381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hostert, A., M. Tolaini, K. Roderick, N. Harker, T. Norton, and D. Kioussis. 1997. A region in the CD8 gene locus that directs expression to the mature CD8 T cell subset in transgenic mice. Immunity. 7:525–536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ellmeier, W., M.J. Sunshine, K. Losos, F. Hatam, and D.R. Littman. 1997. An enhancer that directs lineage-specific expression of CD8 in positively selected thymocytes and mature T cells. Immunity. 7:537–547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Glimcher, L.H., M.J. Townsend, B.M. Sullivan, and G.M. Lord. 2004. Recent developments in the transcriptional regulation of cytolytic effector cells. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 4:900–911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pearce, E.L., A.C. Mullen, G.A. Martins, C.M. Krawczyk, A.S. Hutchins, V.P. Zediak, M. Banica, C.B. DiCioccio, D.A. Gross, C.A. Mao, et al. 2003. Control of effector CD8+ T cell function by the transcription factor Eomesodermin. Science. 302:1041–1043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sullivan, B.M., A. Juedes, S.J. Szabo, H.M. Von, and L.H. Glimcher. 2003. Antigen-driven effector CD8 T cell function regulated by T-bet. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 100:15818–15823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Szabo, S.J., B.M. Sullivan, C. Stemmann, A.R. Satoskar, B.P. Sleckman, and L.H. Glimcher. 2002. Distinct effects of T-bet in TH1 lineage commitment and IFN-gamma production in CD4 and CD8 T cells. Science. 295:338–342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Intlekofer, A.M., N. Takemoto, E.J. Wherry, S.A. Longworth, J.T. Northrup, V.R. Palanivel, A.C. Mullen, C.R. Gasink, S.M. Kaech, J.D. Miller, et al. 2005. Effector and memory CD8+ T cell fate coupled by T-bet and eomesodermin. Nat. Immunol. 6:1236–1244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Izon, D.J., J.A. Punt, L. Xu, F.G. Karnell, D. Allman, P.S. Myung, N.J. Boerth, J.C. Pui, G.A. Koretzky, and W.S. Pear. 2001. Notch1 regulates maturation of CD4+ and CD8+ thymocytes by modulating TCR signal strength. Immunity. 14:253–264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhu, J., B. Min, J. Hu-Li, C.J. Watson, A. Grinberg, Q. Wang, N. Killeen, J.F.J. Urban, L. Guo, and W.E. Paul. 2004. Conditional deletion of Gata3 shows its essential function in T(H)1-T(H)2 responses. Nat. Immunol. 5:1157–1165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pai, S.Y., M.L. Truitt, and I.C. Ho. 2004. GATA-3 deficiency abrogates the development and maintenance of T helper type 2 cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 101:1993–1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rothenberg, E.V., and T. Taghon. 2005. Molecular genetics of T cell development. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 23:601–649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Makar, K.W., and C.B. Wilson. 2004. DNA methylation is a nonredundant repressor of the Th2 effector program. J. Immunol. 173:4402–4406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Makar, K.W., M. Perez-Melgosa, M. Shnyreva, W.M. Weaver, D.R. Fitzpatrick, and C.B. Wilson. 2003. Active recruitment of DNA methyltransferases regulates interleukin 4 in thymocytes and T cells. Nat. Immunol. 12:1183–1190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lu, Q., A. Wu, D. Ray, C. Deng, J. Attwood, S. Hanash, M. Pipkin, M. Lichtenheld, and B. Richardson. 2003. DNA methylation and chromatin structure regulate T cell perforin gene expression. J. Immunol. 170:5124–5132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Busslinger, M. 2004. Transcriptional control of early B cell development. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 22:55–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bosselut, R., S. Kubo, T. Guinter, J.L. Kopacz, J.D. Altman, L. Feigenbaum, and A. Singer. 2000. Role of CD8beta domains in CD8 coreceptor function: importance for MHC I binding, signaling, and positive selection of CD8+ T cells in the thymus. Immunity. 12:409–418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Saitoh, T., H. Nakano, N. Yamamoto, and S. Yamaoka. 2002. Lymphotoxin-beta receptor mediates NEMO-independent NF-kappaB activation. FEBS Lett. 532:45–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Morita, S., T. Kojima, and T. Kitamura. 2000. Plat-E: an efficient and stable system for transient packaging of retroviruses. Gene Ther. 7:1063–1066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.