Abstract

We report the case of an Epstein-Barr virus (EBV)- and human immunodeficiency virus-serum negative patient suffering from repeatedly relapsing classical Hodgkin’s Lymphoma (cHL) associated with a histological picture of plasma cell-hyaline vascular (PC-HV) form of Castleman’s disease (CD). The CD30- and CD15- positive, Reed-Sternberg/Hodgkin cells, only occasionally expressed the CD20 molecule, but not leukocyte common antigen and latent membrane protein-1. Single-strand polymerase chain reaction failed to detect human herpesvirus 8 or EBV in the involved tissues. At the time of second relapse in July 2005, the clinical picture was characterized by a palpable right hypogastric mass, disclosed at physical exam, in the absence of other enlarged peripheral lymph nodes, subjective symptoms or laboratory profile alterations. Combined hybrid-(18)F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission-computerized tomography (18F-FDG PET/CT) showed increased radionuclide uptake in multiple external iliac lymph nodes [standardized uptake value (SUV) of 7.4] and non-palpable left supraclavicular lymph nodes (SUV of 5.8). Relapsing cHL in the context of mixed PC-HV CD was documented in two of three surgically excised abdominal lymph nodes never previously enlarged or involved by any lymphoproliferative disease. Because of the limited disease extension and failure to induce continuous remission with previous conventional chemoradiotherapy, the patient was treated with six rituximab injections. This immunotherapy induced significant reduction in size of supraclavicular lymph nodes as evident at ultrasound (US) scan (<1 vs. 2.5 cm, post- vs. pretherapy), which was confirmed by the 18F-FDG PET/CT in October 2005, despite no modification in SUV of 4.2. 18F-FDG PET/CT also disclosed no radionuclide uptake by abdominal lymph nodes. Thus, a second course of four additional rituximab injections was given and subsequent 18F-FDG PET/CT indicated persistent, but reduced incorporation of radionuclide compared to the pretherapy value (SUV of 2.7) in the supraclavicular area and confirmed a normal metabolic activity in the iliac external lymph nodes. Because of uncertain persistent disease in the supraclavicular nodal site, involved-field radiotherapy (RT) was delivered in that area as consolidation treatment. After completion of rituximab and RT for 16 and 14 months respectively, US and 18F-FDG PET/CT exams were indicative of complete remission. This case is in concordance with previously published data suggesting that rituximab immunotherapy might be a valid option in the treatment of CD and also have a role in the management of relapsing cHL.

Keywords: Castleman’s disease, Hodgkin’s lymphoma, rituximab, human herpesvirus-8 infection, interleukine-6

Case report

In October 2001, a 27 yr-old woman, in documented complete remission (CR) of classical Hodgkin lymphoma (cHL) diagnosed 16 months before, presented at routine follow-up computerized tomography (CT) scan with five enlarged abdominal lymph nodes also detected when the initial diagnosis of lymphoma was made. The patient was asymptomatic and routine laboratory tests were normal.

In July 2000, at the beginning of clinical history, the patient complained, in an otherwise well being status, a rubbery, swelling, non-tender left supraclavicular enlarged lymph node. Increased levels of erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) (103 mm/h), blood copper [400 μg/dL; upper normal limit (UNL): 152], C-reactive protein (CRP) (4.82 mg/dL; UNL: 0.5), IgG (2100 mg/dL; UNL: 1600), polyclonal γ-globulins (2.01 g/L; UNL: 1.52 g/L) and α2-globulins (1.34 g/L; UNL: 1.08 g/L), as well as microcytic-hypochromic anemia (Hb 10.1 g/dL) due to iron deficiency, were also recorded at that time. CT scan revealed enlarged lymph nodes in the upper- (bilateral laterocervical and supraclavicular, mammary and mediastinal) and in the sub-diaphragmatic (interaorto-caval and hepatic hilar) regions. Histology of left supraclavicular lymph node showed intense follicular hyperplasia, preserved germinal centers and expansion of the interfollicular area containing small lymphocytes, plasma cells, eosinophiles and classical Reed-Sternberg and Hodgkin (RS/H) and ‘lacunar’ variant cells, expressing CD15, CD30, only occasionally CD20, but not leukocyte common antigen (LCA) and latent membrane protein-1.

Lymphoma involvement of the bone marrow was excluded histologically on posterior iliac crest biopsy specimen. Based on these clinico-pathological findings, a diagnosis of nodular sclerosis, stage III A, non-bulky cHL was made. The international prognostic index score was 2. Of note, the patient was Epstein-Barr virus (EBV)- and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-serum negative.

Thus, six courses of adriamycin, bleomicin, vinblastin and dacarbazine (ABVD) chemotherapy were administered from August 2000 to January 2001. Rapid normalization of laboratory abnormalities was observed during treatment and post-therapy CT scan documented complete regression of all pathological lymph nodes. However, persistent post-chemotherapy active disease in the mediastinum was suggested by 67Gallium (Ga) uptake. After radiotherapy (RT) (3000 cGy) delivered from February to March 2001 to the involved mediastinal region and extended to the supraclavicular area bilaterally, no residual lymphoma could be detected by the subsequent 67Ga-Single Photon Emission Computed Tomography (SPECT) exam, while second post-therapy CT scan confirmed complete regression of all adenopathy.

According to patient’s history, relapsing lymphoma was the favored hypothesis in the interpretation of the CT findings noted in October 2001. However, several considerations raised the question of whether those enlarged lymph nodes could reflect ab initio other conditions, such as reactive lymphoma-associated adenopathy or atypical lymphoproliferative disease concomitant with HL. In fact, multiple laboratory abnormalities, some of which not completely typical for HL, such CRP values more than nine times above the UNL, increased IgG, α2 and polyclonal γ-globulin values, were noted at the time of diagnosis. Moreover, initial disease was more extensive in the upper- than in the sub-diaphragmatic region in terms of number and size of the involved lymph nodes.

Thus, a ‘non-operative’ strategy was adopted in the hypothesis that subsequent evolution could eventually clarify the nature of the enlarged nodes, and careful watch-and-wait policy was therefore undertaken. The patient remained asymptomatic, 67Ga-SPECT repeated in January 2002 showed no mediastinal disease, but CT scan performed in April 2002 confirmed the presence of multiple enlarged lymph nodes, unmodified in number and size, in comparison with those revealed 6 months before. Laboratory tests showed slightly increased ESR values (36 mm/h), but not other abnormalities. However, in June 2002 combined hybrid-(18)F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission-computerized tomography (18F-FDG PET/CT) disclosed increased radionuclide uptake with a standardized uptake value (SUV) of 2.9 to 3.7 in the same abdominal lymph nodes previously shown at CT-scan.

Concordance between 18F-FDG PET/CT and CT scan findings strongly suggested the presence of active disease in the abdominal lymph nodes and prompted the execution of a laparoscopic nodal biopsy. However, the histolgical picture was consistent with mixed hyperplastic lymphadenitis (lymphoid follicles with germinal centers formed by CD20-positive, but bcl2-negative cells, and mild hyperplasia of the interfollicular area rich in CD3 expressing cells) and excluded relapsing HL.

Clinical-laboratory-radiological follow-up was therefore continued. From August 2002 to September 2003, the patient referred a well being status and monthly-performed physical examinations were normal. However, a very slowly progressive increase in size of the abdominal enlarged lymph nodes was revealed by the CT exams in October 2002, December 2002 and April 2003 while hepatosplenomegaly, mediastinal, laterocervical or other superficial adenopathies were constantly absent. ESR progressively increased up to 116 mm/h in September 2003 and serum copper values raised over normal (204 mcg/dL). Slowly increasing CRP values (4.40 mg/dL) and a progressively worsening microcytic-hypochromic anemia (Hb = 10 g/dL) were also documented. In late September 2003 the patient complained episodic mild arthralgias and paresthesias. Anti-nuclear antibodies were positive with a granular pattern on human epidermoid larynx carcinoma (HEP)-2 cell (1 : 80), and for the first time, hypoalbuminemia (3.5 g/dL) was documented. Increased values of polyclonal γ-globulins (2.93 g/L) and α2-globulins (1.29 g/L) were also present, while extractable nuclear antigens, Waaler-Rose assay and rheuma test were negative and complement (C3, C4) serum levels, as well as phospho-creatin kinase values, were normal. Similarly, electromyography did not show abnormalities. The CT scan performed in October 2003 confirmed the findings revealed at previous exams and disclosed newly occurring abdominal enlarged lymph nodes.

The observation of progressive worsening of laboratory parameters, increased size and number of lymph nodes and the transient symptoms, not typical for HL, prompted the excision of a further paracaval lymph node in order to clarify the nature of the disease or condition possibly responsible for those events.

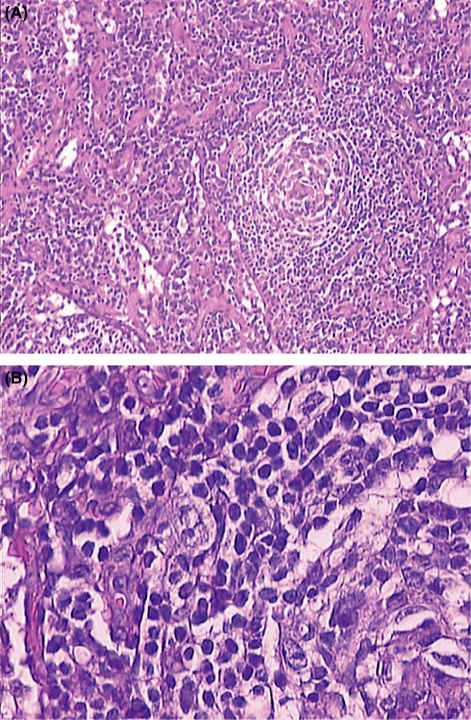

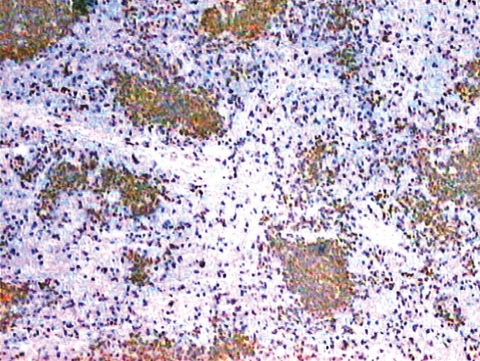

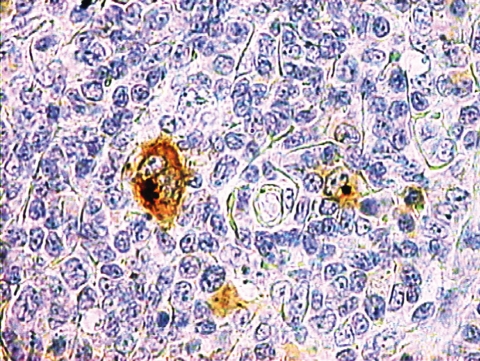

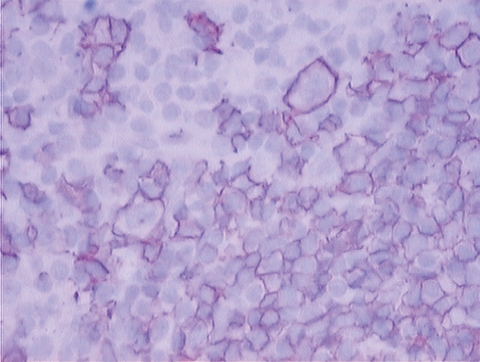

Microscopic examination (Fig. 1A and B) showed numerous lymphoid follicles, some of which with atrophic germinal centers crossed by several vessels (factor VIII-positive and CD31-positive endothelial cells) with hyaline walls and surrounded by concentric layers of lymphocytes (LCA-positive). The germinal centers consisted of CD20-positive cells (Fig. 2) and CD21-/CD35-positive dendritic elements. Sheets of mature polyclonal plasma cells and rare CD15-positive (Fig. 3), CD30-positive, but CD20 −/+ RS/H cells (Fig. 4) in the interfollicular area were detected. Those findings were consistent with mixed plasma cell-hyaline vascular (PC-HV) type Castleman’s disease (CD) or PC-HV-like CD pathological changes and recurrent cHL. Bone marrow examination revealed no RS/H cells, plasmocytosis or other abnormalities. Diagnosis of relapsing stage IIA HL was made. In order to better define the pathogenetic biological background of those histological findings, molecular studies were performed on genomic DNA, extracted from formalin-fixed tissues and tested for polymerase chain reaction (PCR) suitability by amplification of a 450 bp BCL-6 gene fragment. B-cell clonality was determined by PCR analysis of both immunoglobulin (Ig) heavy and light chain variable gene (IGV) rearrangements (1). The PCR protocol, standardized to detect at least ten clonal cells in a background of 104 cells, showed the presence of a polyclonal pattern of rearrangements. This was consistent with the policlonality of Ig light chain found at immunohistochemical examination. Human herpesvirus (HHV)-8 infection was evaluated using single-strand PCR with primers KS330233-F and KS330233-R, which allows the detection of 50–100 viral copies in a background of 15 000 cells (2), but viral DNA was not detected in the tissue specimens analyzed. The same PCR analysis performed for the EBV protein EBNA-1 resulted negative.

Figure 1.

(A) Small abnormal germinal center with concentric arrangement of small lymphocytes and hypervascular interfollicular tissue rich in plasma cells (HES, 10x). (B) Lacunar variant Reed/Sternberg and Hodgkin cell at the periphery of the follicle (HES, 40x).

Figure 2.

Lymphoid follicles with germinal centers in the context of Castleman’s disease. Immunostaining for CD20 (10x).

Figure 3.

CD15-positive Reed/Sternberg and Hodgkin cells.

Figure 4.

Reed/Sternberg and Hodgkin cells immunostained for CD20.

Thus, ABVD chemotherapy was chosen, because of patient’s previous good response to this regimen and because we considered patient’s prognosis as related to the relapsing lymphoma rather than to the CD pathological picture, being the latter either an autonomous lymphoproliferative disease or merely a HL-induced tissue reactive modification.

Because HL relapse was histologically proven 33 months after the completion of first-line chemotherapy, in previously unirradiated lymph nodes, and because of the absence of B symptoms, the indolent clinical course, and the possibly increased incidence of infections in the course of autonomous, multicentric (M)-CD, an autologous bone marrow transplantation was considered, but not judged as the ideal salvage therapy in this case.

During chemotherapy, from December 2003 to May 2004, ESR and Hb values returned to normality (10 mm/h and 14.1 g/dL) and a reduction in size and number, but not disappearance, of the abdominal lymph nodes was observed at CT scan after the second and fourth cycle of therapy. As a total dose of adriamycine of 500 mg/m2 had already been administered, this drug was substituted by liposomal doxorubicine for the last two cycles. Because four residual enlarged lymph nodes of (1–2 cm of diameter) were still documented at CT scan after the completion of the sixth cycle of chemotherapy, another nodal excision was performed in order to discriminate between lymphoma, and autonomous CD involvement of those lymph nodes. The decision was supported by the previous particularly indolent patient clinical history and the need of planning further therapy. Persistence of RS/H cells in the background of mixed PC-HV type CD picture or CD-like histological changes was documented. Thus, peripheral blood stem cell (PBSC) mobilization and subsequent RT to involved abdominal nodes were planned. PBSCs were successfully mobilized in July 2004 (a total number of 201 × 104 CD34+ and 19.4 × 106 of CFU-GM cells, respectively) using 16 μg/kg granulocyte-colony stimulating factor daily for 8 d, including the 3 d of stem cell harvesting. A second CR was achieved after RT (4000 cGy) delivered from August to September to the involved lymph nodes, as displayed by 18F-FDG PET/CT in September 2004.

In July 2005, despite normality of laboratory tests, physical examination revealed an isolated abdominal palpable mass at the right side of the hypogastric region. 18F-FDG PET/CT scan revealed increased radionuclide uptake in the right external iliac and non-palpable right supraclavicular lymph nodes, but no other abnormalities, with SUVs of 7.4 and 4.7 respectively. A new biopsy revealed relapsing cHL in the context of mixed type CD or CD-like changes in two of the three surgically excised hypogastric adenopathies, the third showing a picture of reactive lymphadenopathy.

The short duration of the second remission obtained with conventional chemo- and RT suggested us to adopt an alternative therapeutic approach. Once again, high dose therapy with PBSC rescue was not judged as the best salvage therapy, because of the limited extension of the lymphoma at the time of this second relapse and the increasing suspect of the existence of an autonomous form of M-CD. In fact, it has been hypothesized that M-CD may arise in a context of an immunoregulatory defect and very little is known regarding the immunosuppressive effects of high dose chemotherapy in this disease.

Although no standard of care has been established for patients with CD, rituximab has been used with variable success in the treatment of HHV-8-related or –unrelated CD forms, in either HIV-positive or –negative patients. It also was shown to produce clinical improvement and an overall response rate of 22% in patients with relapsed cHL in a pilot study from Younes et al. (3).

Based on such considerations, in August 2005 rituximab therapy was started at a dose of 375 mg/m2 weekly. Supraclavicular region was utilized to monitor treatment efficacy, being the easiest to evaluate with ultrasound (US) scan and surgical scar hampered US study of the abdominal nodes. US scan, performed after two anti-CD20 injections, showed considerable reduction in size of the supraclavicular lymph node (diameter <1 cm), as compared to the pre-therapy evaluation (diameter 2.5 cm). This lymph node shrinkage was also documented after the fourth and sixth rituximab injection. PET/CT scan confirmed reduced size of supraclavicular adenopathy, but no variation in 18F-FDG incorporation (SUV of 4.2), while showing absence of radionuclide uptake in the abdominal lymph nodes. Because of patient well being, normality of all laboratory tests and at least partial remission of the disease in response to rituximab, four additional anti-CD20 injections were given 1 month later, determining an uncertain CR, as indicated by reduced area of 18F-FDG incorporation, as well as decreased metabolic activity in the supraclavicular area with a SUV of 2.7 and confirmation of the absence of radionuclide uptake in the abdominal lymph nodes, respectively. Involved-field RT (21 Gy, 14 fractions of 150 cGy) was administered to the former area, as consolidation treatment in January 2006. Repeated US and 18F-FDG PET/CT exams were indicative of continuous CR after 16 and 14 months after the completion of rituximab and RT, respectively.

Discussion

CD is a rare, heterogeneous clinico-pathological lymphoproliferative disorder of unknown origin (4, 5). Histological diversity is due to the existence of different variants of the disease including the most common, pathologically-well defined, hyaline vascular (HV) form, the less frequent plasma cell (PC) type, the composite HV-PC type and the plasmablastic (PB) type (4, 5). The anatomo-clinical pattern of CD can vary from a localized mass to a systemic disorder with widespread adenopathy with or without splenomegaly (4, 5).

These histological subtypes correlate with recognized clinical syndromes. The HV type is usually characterized by a single large solitary mass, indolent clinical behavior and absence of constitutional symptoms, while the PC variant, in either localized or multicentric clinical presentation, is often associated with constitutional symptoms, autoimmune manifestations, recurring infections and laboratory abnormalities. The PC-multicentric type can be characterized by a multi-relapsing, chronic non-progressive or rapidly fatal course. Finally, the PB form is characterized by the presence of plasmablasts that express HHV-8 latent nuclear antigen and is found mostly in HIV-positive patients. It consists in all cases, of a systemic and symptomatic, clinically aggressive disease (4, 5). This overall diversity might reflect different etiopathogenetic mechanisms (5, 6).

CD can occur as an autonomous pathologic entity (primary CD). However, CD-like histological picture can be found in association with other nosologically well defined diseases (4, 5). Thus, the term of secondary M-CD utilized by some, but not all, pathologists identifies all the cases in which the clinico-pathologic complex of this disorder is associated with other pathological conditions. In these cases there is a prevalence of the PC form in the florid proliferative phase or in the spent HV-like evolutive state of the involved lymph nodes (4).

The non-specific nature of the pathologic features of PC-CD along with clinico-laboratory manifestations that this variant shares with many other inflammatory and lymphoproliferative disorders makes the occurrence of PC-CD-like changes a frequently described event in the literature (4). HL is described with adjacent CD-like changes or in association with CD or CD-like changes (5, 7–10).

The fact that such an association was observed at first relapse in the case described, might reflect the true coexistence of two autonomous diseases. Overtime repeated observations of only rare RS/H cells in the predominant context of a PC-HV histology and the absence of CD changes at the time of diagnosis support this hypothesis. However, it is not possible to exclude the coexistence of cHL and CD histological picture ab initio in adjacent lymph nodes not sampled. Alternatively, the histological CD changes might be the result of the hyperactivation of benign B-lymphocytes that form cellular background of HL involved tissue along with PCs and T-lymphocytes. In fact, many pathologists believe that the so called secondary forms of CD are merely the final end point of the interleukine (IL)-6-induced environment and not an autonomous disorder.

Overproduction of IL-6, vascular-endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and other cytokines (4, 5, 11, 12) is thought to be responsible for the clinicopathologic complex common to all these conditions. This pathogenetic hypothesis represents the rationale for immunotherapy approaches targeting IL-6 or its receptor. Both murine anti-human IL-6 monoclonal antibody and humanized IL-6 receptor antibody alleviated symptoms, normalized biochemical parameters and reduced lymphoadenopathies associated with M-CD (13, 14). These effects were durable when therapy was extended over a prolonged time period (14). Another immunotherapy approach consists in the use of rituximab (15–22). This treatment produces variably successful control of HHV8-related or unrelated, primary or secondary M-CD forms, irrespective of host’s HIV infection status. Furthermore, the activity of rituximab in patients with HHV8-unrelated form was documented in cases with either elevated or normal levels of this molecule. The therapeutic mechanism of rituximab consists in targeting and depleting CD20-positive B cells which are directly or indirectly responsible for the deregulated production of human IL-6, VEGF and other cytokines (4, 5, 11, 12). This mechanism of rituximab is also advocated to explain its effect in patients with relapsed cHL (3). In fact, some observations indicate that benign B-lymphocytes, in addition to activated T-cells infiltrating cHL lesions may contribute to the survival of RS/H cells in vivo (23, 24).

In favor of this view stands the observation that no HHV8 infection was detected in the cells obtained from the lymph nodes simultaneously involved by histological CD changes and cHL. On the other hand, RS/H cells produce IL-6 (25), which is induced by EBV infection or by non-viral activation of nuclear transcription factor k-B (26). This second pathway is probably operating in the EBV–negative case described above, whose indolent clinical-laboratory features also suggest an IL-6 production mainly limited to the lymph nodal environment, being not a systemic event.

Irrespective of the final interpretation of these pathologic findings, there was evidence of rituximab efficacy in our patient. This monoclonal antibody probably targeted and depleted the CD20-positive lymphocytes infiltrating the lymphoma involved tissue and perhaps shared by HL background and CD. Thus, purging of CD20-positive cells with rituximab might have deprived RS/H cells of a survival factor. This conclusion is reinforced by the immunophenotype of RS/H cells that did not or only rarely expressed the CD20 molecule and therefore were not the primary target of rituximab.

The overall very indolent clinical evolution, along with the lack of spleen and liver involvement and the pattern of relapsing diseases (cHL and CD) remaining confined to few nodal sites even at the time of second relapse, when anatomical areas in both sides of diaphragm were involved, may have favored the response to rituximab.

References

- 1.Capello D, et al. Molecular histogenesis of posttransplantation lymphoproliferative disorders. Blood. 2003;102:3775–85. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-05-1683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gaidano G, et al. Distribution of human herpesvirus-8 sequences throughout the spectrum of AIDS-related neoplasia. AIDS. 1996;10:941–9. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199610090-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Younes A, et al. A pilot study of Rituximab in patients with recurrent classic Hodgkin disease. Cancer. 2003;98:310–4. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Frizzera G. Atypical lymphoproliferative disorders. In: Knowles DM, editor. Neoplastic Hemopathology. 2. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams/Wilkins, Inc; 2001. pp. 595–607. [Google Scholar]

- 5.McClain KL. Atypical cellular disorders. Section III: Castleman’s disease: one disease or several? Haematology (Am Soc Hematol Educ Program). 2004:283–96. doi: 10.1182/asheducation-2004.1.283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pauwels P. A chromosomal abnormality in hyaline vascular Castleman’s disease. Am J Surg Pathol. 2000;24:882–8. doi: 10.1097/00000478-200006000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Drut R. Coexistence of Hodgkin’s disease and Castleman’s disaease. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1996;120:91–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Frank DK. Plasma cell variant of Castleman’s disease occurring concurrently with Hodgkin’s disease in the neck. Head Neck. 2001;23:166–9. doi: 10.1002/1097-0347(200102)23:2<166::aid-hed1012>3.0.co;2-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Caussinus E. Simultaneous occurrence of Epstein-Barr virus associated Hodgkin’s disease and HHV-8 related multicentric Castleman’s disease: a fortuitous event? J Clin Pathol. 2001;54:790–1. doi: 10.1136/jcp.54.10.790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Larroche C. Castleman’s disease and lymphoma: report of eight cases in HIV-negative patients and literature review. Am J Hematol. 2002;69:119–26. doi: 10.1002/ajh.10022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nishi J, et al. Expression of vascular endothelial growth factor in sera and lymph nodes of the plasma cell type of Castleman’s disease. Br J Haematol. 1999;104:482–5. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.1999.01208.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Foss HD. Expression of vascular endothelial growth factor in lymphomas and Castleman’s disease. J Pathol. 1997;183:44–50. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9896(199709)183:1<44::AID-PATH1103>3.0.CO;2-I. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Beck JT. Brief report: alleviation of systemic manifestations of Castleman’s disease by monoclonal anti-interleukin-6 antibody. N Engl J Med. 1994;330:602–5. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199403033300904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nishimoto N, et al. Humanized anti-interleukin-6 receptor antibody treatment of multicentric Castleman’s disease. Blood. 2005;106:2627–32. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-12-4602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Corbellino M, et al. Long-term remission of Kaposi sarcoma-associated herpesvirus-related multicentric Castleman’s disease with anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody therapy. Blood. 2001;98:3473–5. doi: 10.1182/blood.v98.12.3473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ide M. Successful treatment of multicentric Castleman’s disease with bilateral orbital tumor using rituximab. Br J Haematol. 2003;121:815–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.2003.04358.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Marcelin AG. Rituximab therapy for HIV-associated Castleman’s disease. Blood. 2003;102:2786–98. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-03-0951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Marrache F. Prolonged remission of HIV-associated multicentric Castelman’s disease with an anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody as primary therapy. AIDS. 2003;17:1409–10. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200306130-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Newsom-Davis T. Resolution of AIDS-related Castleman’s disease with anti-CD20 monoclonal antibodies is associated with declining IL-6 and TNF-alpha levels. Leuk Lymphoma. 2004;45:1939–41. doi: 10.1080/10428190410001693533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kofteridis DP. Multicentric Castleman’s disease: prolonged remission with anti CD-20 monoclonal antibody in an HIV-infected patient. AIDS. 2004;18:585–6. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200402200-00037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ocio EM. Efficacy of rituximab in an aggressive form of multicentric Castleman disease associated with immune phenomena. Am J Hematol. 2005;78:302–5. doi: 10.1002/ajh.20283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ide M. Long-term remission in HIV-negative patients with multicentric Castleman’s disease using Rituximab. Eur J Haematol. 2006;76:119–23. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0609.2005.00570.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Younes A. CD30 ligand is expressed on resting normal and malignant human B lymphocytes. Br J Haematol. 1996;93:569–71. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.1996.d01-1686.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Clodi K. Expression of CD40 ligand (CD154) in B and T lymphocytes of Hodgkin Disease: potential therapeutic significance. Cancer. 2002;94:1–5. doi: 10.1002/cncr.10164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jucker M, et al. Expression of interleukin-6 and interleukin-6 receptor in Hodgkin’s disease. Blood. 1991;77:2413–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hinz M, et al. Nuclear factor kappaB-dependent gene expression profiling of Hodgkin’s disease tumor cells, pathogenetic significance, and link to constitutive signal transducer and activator of transcription 5a activity. J Exp Med. 2002;196:605–17. doi: 10.1084/jem.20020062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]