Abstract

The current study examined the nature and consequences of attributions about unsuccessful thought suppression. Undergraduate students with either high (N=67) or low (N=59) levels of obsessive-compulsive symptoms rated attributions to explain their unsuccessful thought suppression attempts. We expected that self-blaming attributions and attributions ascribing importance to unwanted thoughts would predict more distress and greater recurrence of thoughts during time spent monitoring or suppressing unwanted thoughts. Further, we expected that these attributions would mediate the relationship between obsessive-compulsive symptom levels and the negative thought suppression outcomes (distress and thought recurrence). Structural equation models largely confirmed the hypotheses, suggesting that attributions may be an important factor in explaining the consequences of thought suppression. Implications are discussed for cognitive theories of obsessive-compulsive disorder and thought suppression.

Keywords: thought suppression, obsessive-compulsive disorder, unwanted thoughts, attributions, obsessions

Current cognitive-behavioral theories of obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) suggest that obsessions arise from misinterpretations of the importance and personal significance of unwanted thoughts (Rachman, 1997; Salkovskis, 1998). The majority of the population experiences unwanted thoughts and images occasionally (i.e., thoughts of driving a car off the road or dropping one’s baby), but dismisses these thoughts as being harmless anomalies (Rachman & de Silva, 1978). However, individuals at risk for developing OCD are believed to resist unwanted thoughts strongly, yet paradoxically find getting rid of these thoughts nearly impossible (Rachman & de Silva, 1978). Understandably, this experience can be distressing, and people make different attributions to explain why the thought returned. Some people may make benign attributions (“I’m just tired today”), while others make more negative attributions (“This thought must have special significance since it keeps returning!”). The current study investigated attributions that individuals at risk for OCD make about their unsuccessful attempts to resist unwanted thoughts, based on the hypothesis that certain negative attributions would predict distress and the recurrence of intrusive thoughts.

Among the strategies people employ to resist unwanted thoughts, ‘thought suppression’ has received substantial attention in the literature (Wenzlaff & Wegner, 2000). During thought suppression, persons attempting to suppress thoughts sometimes ironically end up thinking more about those thoughts, particularly when encountering other simultaneous cognitive demands (for a review, see Wenzlaff & Wegner, 2000). Notably, individuals with OCD attempt thought suppression more frequently than non-anxious individuals do (Amir, Cashman & Foa, 1997) and as a result may be more vulnerable to the unintended increases in frequency of unwanted thoughts and accompanying distress. Consistent with these suggestions, cognitive-behavioral theories of OCD have hypothesized that thought suppression is likely to be a frequently used - but maladaptive – approach, which contributes to the etiology and maintenance of the disorder (Rachman, 1997, 1998; Salkovskis, 1985, 1989, 1998).

Recently, several researchers have explored how thought suppression might have maladaptive effects in OCD (Purdon, 2004; Tolin, Abramowitz, Hamlin, Foa & Synodi, 2002). They have proposed that the recurrence of unwanted thoughts despite suppression efforts could serve to enhance negative attributions (i.e., “This thought kept returning despite my suppression attempts; therefore, it must have been important”). This approach contends that the return of a thought is not necessarily a problem by itself, but can become harmful due to the attributions individuals make. Therefore, certain attributions for unsuccessful suppression attempts are believed to enhance distress, obsessive beliefs and suppression effort. This proposal offers a plausible mechanism to explain why the findings for recurrence of thoughts after suppression are so divergent across studies and across suppression attempts by the same individual.

In an innovative series of studies, Purdon and her colleagues examined interpretations1 of thought recurrences after suppression attempts (Markowitz & Purdon, 2004, as cited in Purdon, 2004; Purdon, 2001; Purdon, Rowa & Antony, 2005). They found that for both non-clinical participants (Purdon, 2001) and participants with OCD (Purdon, Rowa & Antony, 2005) interpretations were important predictors of distress. Specifically, participants who endorsed interpretations that thought recurrences demonstrated undesirable personal characteristics or predicted future negative events reported more discomfort than those who did not report such interpretations. Moreover, Belloch, Morillo and Gimenez (2004) and Markowitz and Purdon (2004, as cited in Purdon, 2004) have also found higher discomfort following negative interpretations of thought recurrences after suppression attempts. Taken together, these findings suggest that interpretations about suppression attempts can have serious consequences for distress after thought recurrences.

The current study built on this exciting earlier work by focusing on attributions for unsuccessful thought suppression. Attributions are important to study because the perceived reason why a thought recurred (i.e., the attribution) may have additional consequences beyond those of the meaning given to a recurring thought (i.e. the interpretation). For example, a thought interpreted as signifying personal immorality may be downplayed if a person attributes its return as being due to an external factor (e.g., “My friend was just talking about that topic, no wonder the thought returned.”). We investigated three factors that we believe are important for understanding the attributions individuals make for unsuccessful thought suppression, and the emotional and cognitive consequences that follow these attributions. First, we examined whether the type of attributions made for unsuccessful thought suppression explains differences between individuals high versus low in OCD symptoms in their reactions to unwanted thoughts. Second, we evaluated whether the type of thought that is the target of suppression influences the type of attributions that are made. Finally, we tested whether the thought suppression instructions individuals receive (i.e., either to suppress or monitor their thoughts) affect the attributions they make.

Attributions may help explain why people with high levels of OCD symptoms have difficulties with the return of unwanted thoughts (Purdon, 2004). Purdon and Clark (1999) suggest that people with OCD symptoms may attribute unsuccessful control attempts to undesirable personality characteristics or threatening qualities of the thought, and Tolin et al. (2002) found that individuals with OCD endorsed relatively more internal (but not external) attributions after suppression when compared to non-anxious participants. Further, Purdon and others suggest that these attributions can lead to worsened mood and further preoccupation with thoughts, strengthening OCD symptoms and reinforcing the original attributions. Following these suggestions, the current study tests the role of attributions as a mediator of the relationship between level of OCD symptoms and future reactions to unwanted thoughts. We expected that participants with high levels of OCD symptoms would endorse more internal attributions and attributions ascribing importance to their thoughts, and these attributions would help explain why these participants have increased distress and recurrence of unwanted thoughts.

To enhance the generalizability of the study, we also wanted to pay special attention to the type of thought used with thought suppression. Previous studies have employed different types of thoughts (e.g., thinking of a white bear versus an ‘obsessional’ thought) to investigate how attributions relate to thought suppression. Results from these studies are complicated and suggest that the nature of the thought may influence the attributions that follow suppression attempts and their consequences (see Abramowitz, Tolin & Street, 2001). Given the possibility that type of thought may be relevant to the attributions made following unsuccessful thought suppression, we included four types of thoughts differing in their negative valence, perceived immorality and personal relevance to participants. To adapt existing thought suppression methods for multiple thoughts, we introduced a novel thought recording methodology that would not confine us to examining only one type of thought at a time. This study was the first we are aware of to use a suppression paradigm where multiple thoughts were to be suppressed and recorded simultaneously. Our examination of mean differences in attributions made after the different types of thoughts was somewhat exploratory. However, we hypothesized that the relationship between attributions and distress/recurrence of thoughts would be comparable across the different types of thoughts (e.g., a self-blaming attribution would predict distress regardless of the type of thought).

An additional methodological challenge in the thought suppression literature concerns the comparison of suppression and control instructions. In particular, there tends to be a high degree of spontaneous active suppression in control groups that is nearly impossible to control in a laboratory setting (Purdon & Clark, 2000, 2001); even researchers using explicit ‘do not suppress’ instructions have found that many participants suppress anyway. Therefore, we anticipated that the monitoring group would engage in some suppression attempts, so we compared monitoring instructions with traditional suppression instructions to see whether the type of instruction leads to different types of attributions. Like the hypotheses for thought type outlined above, we expected that the relationship between attributions and distress/recurrence of thoughts would be comparable across instructions. However, it seemed plausible that, at the mean level, individuals given suppression instructions may more easily attribute unsuccessful suppression to external factors (“I wasn’t directing this effort so it was someone else’s fault that the thought came back”). In contrast, people who initiate suppression by their own volition (i.e., the monitoring condition) may be more likely to endorse internal attributions.

The current study tested the nature and consequences of attributions about unsuccessful thought suppression on subsequent distress and thought recurrence. To the best of our knowledge, this was the first study to explore the possible associations between type of attribution and future suppression outcomes, and to explore these associations following different types of unwanted thoughts. Participants high and low in OCD symptoms were randomly assigned to suppress or monitor four types of unwanted thoughts, and then indicate whether or not they had experienced any difficulty controlling the four different thoughts during the period. If they endorsed difficulty, participants then rated various attributions to explain why they were unable to keep that particular thought out of mind. To measure the consequences of these attributions, participants rated distress and recurrence of thoughts following both an initial suppression or monitoring period and again following a subsequent monitoring period.

Our central hypothesis was that individuals who made self-blaming attributions or attributions ascribing importance to their unwanted thoughts would show more distress and greater thought recurrence when compared to individuals who did not endorse these attributions. Further, we expected that these self-blaming and importance attributions would mediate the relationship between OCD symptom level and the distress and thought recurrence outcomes. In contrast, given that previous research has shown that external (“The task was silly”) and normative (“Thoughts aren’t controllable) attributions do not differ between people with OCD and non-anxious participants (Tolin et al., 2002), we did not expect these attributions to predict the distress and thought recurrence outcomes or to act as mediators. Finally, across the different types of to-be-suppressed thoughts and thought suppression instructions, we hypothesized that while attributions might show mean differences, they would consistently predict distress and thought recurrence.

Method

Participants

Undergraduate students (N = 126)2 participated in the study as part of the psychology participant pool at the University of Virginia (mean age: 18.7 years, 58% female). Sixty-nine percent reported race or ethnicity as Caucasian, 10% Asian, 9% African-American, 6% Hispanic, and 6% indicated “other” or chose not to report their ethnicity. As part of the pool, participants completed a preselection questionnaire measuring OCD symptoms (the Obsessive-Compulsive Inventory-Revised; Foa et al., 2002) and were selected based upon scoring in the upper or lower 20% of their preselection group. Participants in the high OCD symptom group (N = 67, 67% female) had an average score well above the recommended clinical cutoff of 21 for college students (M = 32.54, SD = 8.23), while participants in the low OCD symptom group (N = 59, 51% female) reported few symptoms (M = 4.92, SD = 2.07).

Materials

OCD and Mood Measures

The Beck Depression Inventory (BDI; Beck & Steer, 1987) is a widely used 21-item self-report inventory of depressive symptoms that has good reliability and validity (Cronbach’s alpha=.88 in the current sample). Items are rated on a 4-point scale from 0 to 3. Generally, scores of less than 11 are regarded as normal, and scores of greater than 19 are interpreted as reflecting clinical levels of depression.

The Obsessive-Compulsive Inventory-Revised (OCI-R; Foa et al., 2002), used to preselect the OC symptom groups, measures overall severity of OCD symptoms and is appropriate for a nonclinical sample. The 18-item measure provides 3-item subscales for specific symptom domains (i.e., Washing, Checking, Ordering, Obsessing, Hoarding, and Neutralizing), has good test-retest reliability and demonstrates convergent validity with other measures of OCD symptoms (Cronbach’s alpha=.94). Each item assesses how much participants were distressed or bothered by a symptom over the past month, with ratings on a 5-point scale ranging from 0 (not at all) to 4 (extremely).

The Obsessional Beliefs Questionnaire-Short Form (OBQ; Obsessive Compulsive Cognitions Working Group, 2005) is a 44-item measure that assesses three factor-derived general belief domains relevant to OCD: Responsibility/Threat Estimation (e.g., needing to prevent harm from happening, feeling responsible for harm), Perfectionism/Certainty (e.g., adherence to rigid standards, inability to tolerate uncertainty) and Importance/Control of Thoughts (e.g., fears about the significance of intrusive thoughts, the need to control intrusive thoughts). The scale consists of statements that participants are asked to rate on a 7-point scale ranging from 1 (disagree very much) to 7 (agree very much). Cronbach’s alpha was .96 in the current sample.

The fear and guilt subscales of the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule-Expanded Form (PANAS-X; Watson & Clark, 1994) were used to measure participants’ state affect following the thought periods. Fear and guilt were selected to assess typical emotions following unwanted thoughts (Rachman, 1998). The fear and guilt subscales show good reliability in non-clinical samples as well as in outpatient and inpatient groups. The fear and guilt subscales each contain six state affect descriptors (e.g., afraid, nervous, guilty, blameworthy). Participants rate how much they are experiencing each descriptor in the moment, using a 5-point scale that ranges from 1 (very slightly or not at all) to 5 (extremely). The average Cronbach’s alpha was .84 for the fear subscale and .88 for the guilt subscale.

Thought Stimuli and Measures

The Thought Control Attributions Questionnaire (TCAQ; developed by the first author), a 17-item questionnaire, was constructed to measure attributions for unsuccessful thought control attempts on a 5-point Likert scale. Previous measures by Purdon have assessed attributions and interpretations about thought suppression (e.g., “The more I had the thought, the more important it seemed that I try to control it”), but the current study required a measure of attributions that was specific to unsuccessful thought suppression. Further, we wanted to sample a broader range of attributions than those identified by Tolin et al. (2002). The TCAQ asks participants to endorse attributions explaining why a thought returned after a suppression attempt. To create the TCAQ, we generated items by a review of the literature, and by consulting with a team of doctoral students and faculty. Factor analysis3 indicated four factors of attributions (sample items noted):

Importance (“I was not able to keep the thought out of my mind because the thought was overpowering.”), Internal (“I was not able to keep the thought out of my mind because there is something wrong with the way I think.”) Normative (“I was not able to keep the thought out of my mind because that is how minds work.”), and External (“I was not able to keep the thought out of my mind because the experimenter made me think about it.”).

Four thought stimuli were provided to participants to monitor or suppress. We carefully chose the four thoughts according to pilot data rating the thoughts on their unpleasantness, perceived immorality, and relevance to participants’ usual thoughts. The thoughts were selected so that each thought reflected a different combination of the key thought dimensions: 1) a white bear (low unpleasantness, low immorality, low relevance) 2) “I will never succeed in my career” (high unpleasantness, low immorality, low-moderate relevance), 3) “I hope my friend is in a car accident” (high unpleasantness, high immorality, low-moderate relevance), 4) A previously experienced unwanted, intrusive thought chosen from a list provided by the experimenter (expected to be high on all characteristics, although some thoughts on the list were not particularly immoral). The list of common unwanted thoughts used was adapted from Kyrios (2000) and Rachman and de Silva (1978).

Computer Recording of Thought Frequency and Duration

During thought monitoring/suppressing periods, participants recorded thought frequency and duration by pressing assigned keys on the computer keyboard (one for each thought). Whenever participants experienced one of the four experimental thoughts, they pressed and held down its assigned key for the duration of the thought. In addition, participants pressed and held down the space bar whenever they experienced any thought other than the four experimental thoughts (or when they experienced thinking about “nothing”). With this approach we were able to compute the frequency and duration (accuracy to at least a tenth of a second) of every thought as reported by the participant. In addition, inclusion of the space bar meant that participants could avoid associating key presses solely with unwanted thoughts. Piloting indicated that participants could easily learn to use this thought recording system, and inspection of the final data revealed that the majority of participants followed instructions successfully (nearly 95% of key presses were on the correct keys).

Procedure

Participants were told the study was about people’s reactions to certain thoughts, and that they would be asked to identify and reflect on thoughts during the study. After informed consent, participants completed the PANAS-X fear and guilt subscales to assess baseline distress. Next, participants completed four practice thinking periods (order counterbalanced). For each practice period, participants wrote out one of the four thoughts and then focused on that thought for one minute while recording the frequency and duration of each thought occurrence by pressing and holding down the assigned computer key. Participants held down the space bar whenever they thought about anything other than the assigned thought.

Participants were randomly assigned to either the thought suppression or monitoring condition for the five-minute experimental thinking period. During this period, participants monitored all four thoughts at once using the assigned keys, as well as the space bar to indicate any other thought. In the thought suppression condition, participants received the following instructions: “For this period, I would like you to try not to think about any of the four thoughts you just focused on. If you do think about one of the thoughts, please mark that you did because this is very important information for us, but try your best not to think about those thoughts.” Participants in the monitoring condition were told: “For this period, think about whatever you would like-it could be any of the four thoughts you thought about before, or it could be anything else.” The experimenter referenced the four thoughts in the monitoring instructions to control for their priming in the thought suppression instructions.

Upon completion of the experimental five-minute thinking period, the computer prompted participants to rate how much they felt they had failed at keeping each of the four thoughts out of their mind. Unless participants indicated complete success at suppressing a thought, they completed the TCAQ to assess attributions explaining why that particular thought returned. Thus, participants completed the TCAQ up to four times, once for each thought. Participants then completed the PANAS-X again to assess distress after the first thinking period. Next, participants completed a second five-minute thinking period. In this period, all participants received the monitoring instructions described previously. Participants again recorded their thoughts using the keyboard system, and completed the PANAS-X. Finally, the OBQ and BDI were administered in random order. Participants completed these measures at the end of the experiment to avoid priming particular attributions or revealing the purpose of the study.

Results

Sample Characteristics

Means and standard deviations for the measures of OCD symptoms and beliefs, depression and attributions for unsuccessful thought suppression are listed in Table 1. As expected, 2 (OCD group: high, low) X 2 (instructions: suppression, monitoring) analyses of variance (ANOVAs) showed that the group with high OCD symptoms reported significantly more obsessive beliefs on the OBQ (F(1,122) = 57.25, p < .001) and depressive symptoms on the BDI (F(1,122) = 39.06, p < .001) than did the group with low OCD symptoms. The monitoring and suppression instruction groups did not differ on the OBQ (F(1,122) = 1.37, p > .10) or BDI (F(1,122) = 2.34, p > .10), indicating that randomization was successful. Chi-square tests indicated that there were no differences between the OCD symptom groups for gender (χ2(1, N=126)= 3.47, p = .063) or ethnicity (χ2(4, N=120) = 1.62, p > .10), and no differences between the instruction groups for gender (χ2(1, N=126) = 0.03, p > .10) or ethnicity (χ2(4, N=120) = 4.69, p > .10).

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics for OCD Symptoms and Beliefs, Mood and Attribution Categories

| OC Status

|

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| High | Low | |||||||

| Thinking Instructions

|

||||||||

| Suppression

(n = 32) |

Monitoring

(n = 35) |

Suppression

(n = 31) |

Monitoring

(n = 28) |

|||||

| M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | |

| OCI-R | 32.30a | 7.12 | 32.77a | 9.22 | 5.00b | 2.08 | 4.83b | 2.09 |

| OBQ | 167.71a | 39.94 | 165.90a | 35.99 | 123.17b | 40.65 | 109.34 b | 31.86 |

| BDI | 15.27 a | 9.46 | 12.21 a | 6.75 | 6.51 b | 4.99 | 5.86 b | 4.37 |

| Import. | 2.75 a | .93 | 3.04 a | .74 | 2.01 b | .81 | 2.18 b | .81 |

| Internal | 1.67 a | .70 | 1.63 a | .52 | 1.14 b | .19 | 1.15 b | .19 |

| Norm. | 3.37 | .75 | 3.39 | .65 | 3.27 | .97 | 3.14 | .89 |

| Extern. | 2.42 a | .73 | 2.80 b | .76 | 1.97 c | .60 | 2.28 ac | .74 |

Note: Group differences are noted by unique letter superscripts (i.e., ‘a’ versus ‘b’) and are all significant at p < .01. OCI-R refers to Obsessive-Compulsive Inventory – Revised; OBQ refers to the Obsessional Beliefs Questionnaire – Short Form; BDI refers to the Beck Depression Inventory; Import., Internal, Norm. and Extern. refer to Importance, Internal, Normative and External attributions from the Thought Control Attributions Questionnaire.

Modeling Procedure

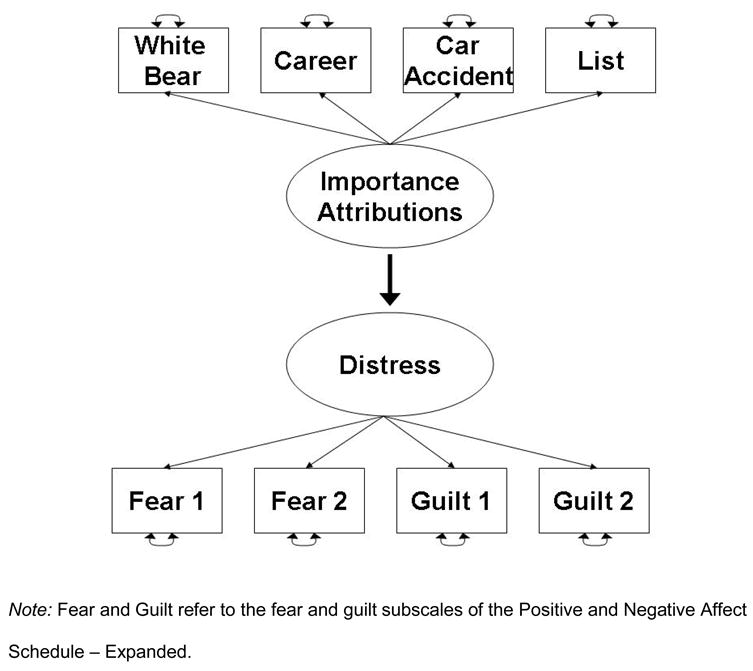

The main purpose of the study was to examine whether attributions predict distress and the recurrence of unwanted thoughts, as well as to test whether attributions explain the relationship between OCD symptom groups and the distress and recurrence of unwanted thoughts. Structural equation modeling (SEM) was used to examine whether attributions following unsuccessful thought suppression predict either distress or the recurrence of unwanted thoughts (see Figure 1 for an example of importance attributions predicting distress). We chose this approach because it allowed for simultaneous consideration of relations between multiple predictors and dependent variables, and allowed for a direct test of our mediation hypotheses. Participants who did not endorse any unsuccessful suppression attempts (only 6 out of 126 participants) were excluded from the models because they did not complete the attribution measure. To represent the ‘attribution,’ ‘distress’ and ‘recurrence of unwanted thought’ constructs, we used four indicators for each. For the attribution constructs (i.e., importance, internal, external, normative), we used responses on the relevant TCAQ subscale after each of the four thoughts (i.e., white bear, career, car accident and list thoughts) as indicators. For example, the latent construct of importance attributions was represented by the TCAQ importance attributions subscale, which was measured up to four times – once for each thought the participant reported failing to suppress. For the distress construct, we included the PANAS-X subscales (fear and guilt) that participants completed after each of the two 5-minute thinking periods. Finally, for the recurrence of unwanted thoughts construct, we created composite frequency and duration scores for each of the two thinking periods by summing across the four unwanted thoughts to reflect total frequency and duration of unwanted thoughts during each thought period. All models were fit using AMOS, and full information maximum likelihood methods were used to treat incomplete data as missing at random (Little & Rubin, 1987). Table 2 shows the descriptive statistics for the recurrence of unwanted thoughts and distress variables after each of the two thinking periods.

Figure 1.

Importance Attributions Predicting Distress Following Thinking about Unwanted Thoughts

Table 2.

Descriptive Statistics for Thought Frequency, Duration and Fear and Guilt

| OC Status

|

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| High | Low | |||||||

| Thinking Instructions

|

||||||||

| Suppression

(n = 32) |

Monitoring

(n = 35) |

Suppression

(n = 31) |

Monitoring

(n = 28) |

|||||

| M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | |

| Period 1 | ||||||||

| Freq. | 12.93a | 10.69 | 18.32b | 12.78 | 10.19a | 7.69 | 13.92ab | 7.64 |

| Duration | 67.32a | 78.41 | 178.77b | 114.11 | 31.00a | 73.05 | 128.18c | 92.35 |

| Fear | 8.19a | 3.28 | 7.94ab | 3.02 | 6.37c | .61 | 6.90bc | 1.69 |

| Guilt | 10.25a | 5.14 | 8.46b | 3.44 | 6.87b | 1.31 | 7.29b | 1.74 |

| Period 2 | ||||||||

| Freq. | 6.85a | 8.96 | 11.30b | 10.38 | 3.44a | 3.63 | 4.67a | 5.61 |

| Duration | 34.11a | 49.56 | 62.36b | 77.24 | 11.46a | 15.27 | 20.00a | 26.04 |

| Fear | 7.78a | 3.26 | 7.29ab | 2.41 | 6.26b | .63 | 6.56b | 1.12 |

| Guilt | 8.69a | 4.15 | 7.88ab | 2.88 | 6.35c | .80 | 6.74bc | 1.43 |

Note: Group differences are noted by unique letter superscripts (i.e., ‘a’ versus ‘b’) and are all significant at p < .05. Freq. refers to the overall frequency of unwanted thoughts in a period. Duration refers to the overall duration of unwanted thoughts in a period. Fear and Guilt refer to the subscales of the same name from the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule-Expanded Form.

Attributions Predicting Distress and Recurrence of Unwanted Thoughts

We hypothesized that importance and internal attributions would predict greater distress and recurrence of unwanted thoughts across thinking periods, while normative and external attributions would be unrelated to the outcomes (because these attributions do not distinguish persons with and without OCD symptoms; Tolin et al., 2002). For each attribution construct, we set up a model in which attributions were a latent factor predicting the latent factors of distress or recurrence of unwanted thoughts (see Figure 1). For these initial models, we collapsed across thought suppression instruction conditions and OCD symptom groups.

As hypothesized, importance attributions predicted distress (standardized regression weight of β = .44, p = .006) and recurrence of unwanted thoughts (β = .46, p = .013). Additionally, internal attributions predicted distress (β = .68, p < .001) and recurrence of unwanted thoughts (β = .22, p = .046). Also as hypothesized, normative attributions did not predict distress (β = .00, p > .10) or recurrence of unwanted thoughts (β = .07, p > .10). Finally, external attributions did not predict distress (β = .10, p > .10) or the recurrence of unwanted thoughts (β = .12, p > .10).

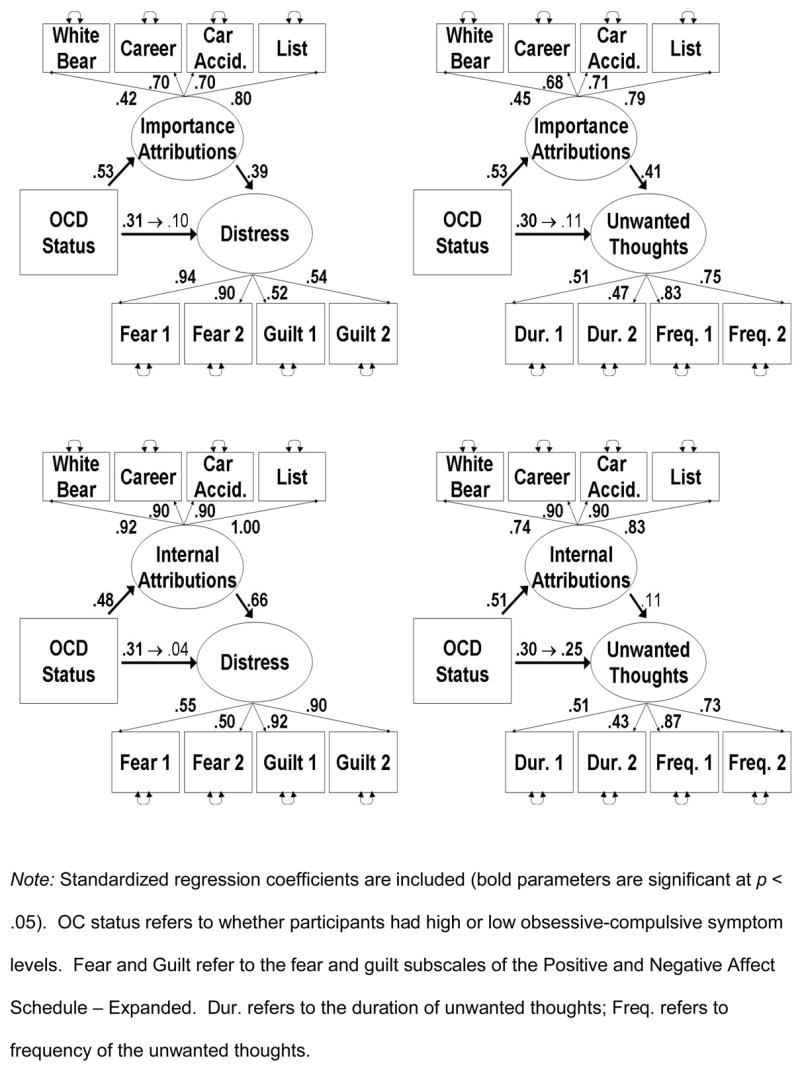

Attributions as a Mediator of OCD Status and Distress/Recurrence of Unwanted Thoughts

Next we tested our hypothesis that importance and internal attributions would mediate the relationship between OC status and distress/recurrence of unwanted thoughts. For each category of attributions, we set up a model in which attributions were entered as a mediator of the relationship between OCD symptoms and the relevant outcome (distress or recurrence of unwanted thoughts; see Figure 2 for examples). According to Baron and Kenney’s (1986) guidelines for mediation, we first tested that high OC status would significantly predict distress and the recurrence of unwanted thoughts. Next, we tested the hypothesis that high OC status would predict importance and internal attributions (but not normative and external attributions), and that importance and internal attributions would in turn significantly predict distress and recurrence of unwanted thoughts. Finally, for full mediation to be found, the significant relationship between OC status and the two outcome variables should become non-significant once importance and internal attributions were included in the model. In the models, OC status was entered as a manifest variable in which the group with high symptoms was coded with a one while the low symptom group was coded with a zero. Therefore, positive standardized coefficients indicate a positive relationship with high OC symptoms.

Figure 2.

Importance and Internal Attributions as Mediators of the Relationship Between OC Status and Distress/Recurrence of Unwanted Thoughts

The first step was to establish that OC status predicted distress and the recurrence of unwanted thoughts. Collapsing across thinking instructions and attribution categories, high OC status significantly predicted distress (β = .31, p < .001) and the recurrence of unwanted thoughts (β = .30, p = .008). In other words, as expected, participants in the group with high (relative to low) OC symptoms showed greater distress and recurrence of unwanted thoughts. Next, we examined each attribution category in a separate model, to see if importance and internal attributions explained the relationship between OC status and the outcomes.

Importance Attributions

As expected, OC status significantly predicted importance attributions (β = .53, p < .001). Further, we found that importance attributions significantly predicted distress (β = .39, p = .015). Finally and most importantly, the relationship between OC status and distress was reduced from β = .31, p < .001 to β = .10, p > .10 once importance attributions were included as a mediator. Using the same approach for recurrence of thoughts, importance attributions predicted recurrence of thoughts (β = .41, p = .028). Further, the relationship between OC status and recurrence of thoughts was meaningfully reduced from β = .30, p < .001 to β = .11, p > .10 once importance attributions were included as a mediator. Thus, importance attributions mediated the relationship between OC status and recurrence of unwanted thoughts as well as distress.

Internal Attributions

OC status significantly predicted internal attributions (β = .48, p < .001). In turn, internal attributions significantly predicted distress (β = .66, p < .001). Further, as expected, the relationship between OC status and distress was reduced from β = .31, p < .001 to β = .04, p > .10, indicating that internal attributions mediated the OC status-distress relationship. However, internal attributions did not significantly predict recurrence of thoughts (β = .11, p > .10). Thus, internal attributions were able to account for the relationship between OC status and distress, but not the relationship between OC status and recurrence of unwanted thoughts.

As a final check of the mediation models, we ran additional models to check that the internal and important attributions predicted distress above and beyond the variance explained by recurrence of thoughts during the first thinking period. This was done to address the possible concern that attributions might simply be a proxy for thought recurrence in these models, stemming from the expected relationship between internal and important attributions and the occurrence of unwanted thoughts during the first time period (i.e., the more thoughts one fails to suppress, the more one may need to explain the failure). In these models, we first allowed the total duration of unwanted thoughts from the first period to predict distress, and then ran the mediation models using the residual variance left in the distress variable as the ‘distress’ outcome. Results indicated no significant changes in the pattern of relationships for either the importance or internal attribution mediation models, indicating that the attributions uniquely predict distress (independent of the recurrence of thoughts during the first thinking period).

Normative Attributions

As expected, OC status did not predict normative attributions (β = .11, p > .10), and normative attributions did not significantly predict distress (β = −.03, p > .10) or recurrence of thoughts (β = .04, p > .10), so there were no grounds to evaluate mediation.

External Attributions

Like normative attributions, we expected that external attributions would not explain the relationships between OC status and the outcomes. Contrary to our hypothesis, external attributions were significantly predicted by high OC status (β = .38, p < .001). However, external attributions did not significantly predict distress (β = −.03, p > .10) or recurrence of thoughts (β = .01, p > .10), leaving no grounds to evaluate mediation. Therefore, while the high OC status group unexpectedly made more external attributions than the low group, external attributions did not explain the relationships among OC status, distress and recurrence of unwanted thoughts.

Generalizing Models Across Different Types of Thoughts and Instructions

Next, we wanted to see whether the attribution models would generalize across the different types of unwanted thoughts (i.e., white bear, career, car accident and list) and thought suppression instructions (i.e., monitoring or suppression). In both cases, we expected that attributions would show the same predictive relationships as in the overall models.

Type of Unwanted Thought

First we examined the models in which attributions predicted distress/recurrence of unwanted thoughts. To examine the consistency of these predictive relationships, we excluded attributions for one thought at a time from the relevant SEM model to determine if removal of a given thought’s attributions changed the significant importance and internal attributions relationships. Specifically, we tested whether the path between the attributions construct and the distress or recurrence outcome was still significant once the coefficient for a given thought’s attributions was constrained to zero (so it no longer contributed to the attributions factor). If the path was no longer significant, this would suggest that attributions about that particular thought were accounting for the overall relationship, indicating that the relationship only held for certain types of to-be-suppressed thoughts. For the most part, it appeared as if no single thought accounted for the significant relationship between attributions and distress/recurrence of thoughts; all paths (except one) remained significant for the importance attribution models, and the internal attributions predicting distress model. Repeating comparable analyses on the mediation models revealed the same pattern - none of the paths were reduced to non-significance for variations of the models that had originally shown mediation.

Thought Suppression Instructions

To test our hypothesis that attributions would predict distress and recurrence of unwanted thoughts regardless of whether participants suppressed by instruction or by their own volition (monitoring instructions), we conducted multi-group comparisons to evaluate invariance across instructions for the importance and internal attributions’ models. Initially, we checked that the percentage of participants endorsing suppression effort and failure for at least one thought was similar for the suppression (94%) and monitoring (97%) groups, so that we could assume that both groups had engaged in suppression but been unsuccessful.

For the multi-group comparisons, we tested whether the path between the attributions and the distress or recurrence of thoughts latent factors would be equivalent across instruction conditions. For the distress models, the importance (ΔX2 = .60 on Δdf = 1, p > .10) and internal attributions (ΔX2 = 2.95 on Δdf = 1, p = .086) paths were invariant across instruction conditions. Similarly, for the recurrence models, both the importance (ΔX2 = 1.20 on Δdf = 1, p > .10) and internal attributions (ΔX2 = .00 on Δdf = 1, p > .10) paths were invariant across instructions. Therefore, the hypothesis that attributions would similarly predict distress and recurrence of unwanted thoughts across suppression and monitor instructions was supported. Similarly, multi-group comparisons for the mediation models showed no instruction group differences in the paths connecting the latent factors for any of the three significant mediation models.

Attribution Mean Levels Across Different Types of Thoughts and Instructions

Type of Unwanted Thought

To examine whether mean levels of attributions differed across the various unwanted thoughts, we conducted a 4 (type of unwanted thought) X 4 (attribution category) repeated-measures ANOVA in which both factors were within-subjects. The interaction was significant (F(9,459) = 40.63, p < .001, η2p = .44), so for each type of unwanted thought we conducted a follow-up one-way repeated-measures ANOVA with Least Squares Difference post-hoc tests to examine differences among the attribution categories. For each type of thought, there was a significant attribution category effect. Table 3 displays the means and standard deviations of attributions for each type of unwanted thought and notes significant differences between the attribution categories. The results suggested several general patterns. First, normative attributions were the most agreed-upon attribution for every type of unwanted thought. Second, for the three negatively valenced thoughts, importance attributions were either endorsed equally as highly as normative attributions, or the second-most. In contrast, for the white bear thought, importance and internal attributions were endorsed the least.

Table 3.

Descriptive Statistics for Attribution Categories by Type of Unwanted Thought

| Attribution Category

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Importance | Internal | External | Normative | |

| White Bear (n = 98) | 1.34a (.57) | 1.24a (.34) | 2.42b (.85) | 3.41c (.88) |

| Career (n = 87) | 3.26a (1.09) | 1.46b (.65) | 2.34c (.87) | 3.28a (.89) |

| Accident (n = 95) | 3.01a (1.17) | 1.43b (.59) | 2.23c (.83) | 3.24a (.90) |

| List (n = 96) | 2.79a (1.11) | 1.59b (.74) | 2.44c (.80) | 3.44d (.86) |

Note: Attribution category differences are noted by unique letter superscripts (i.e., ‘a’ versus ‘b’) and are all significant at p < .01. The sample sizes reflect the number of participants (out of 126) that reported failure suppressing that particular thought.

Thought Suppression Instructions

To assess whether mean levels of attributions differed across suppression instructions, we conducted a 2 (suppression/monitor instructions) X 4 (attribution category) repeated-measures ANOVA in which instructions was a between-subjects factor. The interaction indicated a non-significant trend (F(3,354) = 2.58, p = .054, η2p = .021), so for each attribution category we ran a follow-up one-way ANOVA to examine differences among the instruction groups. The instruction groups did not differ on importance attributions (F(1,118) = 2.41, p > .10, η2p = .020), internal attributions (F(1,118) = .00, p > .10, η2p = .00), or normative attributions (F(1,118) = .10, p > .10, η2p = .001). However, the monitoring group did endorse significantly more external attributions than the suppression group (F(1,118) = 6.94, p = .010, η2p = .056).

Relationships among Attribution Factors

To look at the interrelations among attribution categories, we averaged across the different instances of a given attribution subscale (e.g., internal) for the different unwanted thoughts to compute average attribution category scores. As expected, the importance and internal attribution categories were moderately, positively related (r = .47, p < .001). However, relationships among the other categories were surprising: external attributions were correlated with both the importance (r = .22, p = .016) and internal attributions (r = .35, p < .001), and normative attributions were correlated with internal attributions (r = .21, p = .021). These unexpected relationships were not large, but nonetheless suggest that the maladaptive (importance and internal) attributions are not entirely independent from the alternative, presumably healthier (external and normative) attributions. Normative attributions were not significantly related to external (r = .13, p > .10) or importance (r = .07, p > .10) attributions.

Discussion

The current study draws from cognitive theories of OCD and the literature on thought suppression to examine new ways in which thought suppression might be linked to OCD symptoms. Specifically, we proposed that making maladaptive attributions for unsuccessful attempts to suppress unwanted thoughts would predict negative cognitive and emotional consequences. We expected that attributions endorsing internal, self-blaming explanations for suppression failure or ascribing importance to unwanted thoughts would predict increased distress and recurrence of unwanted thoughts, while attributions dismissing failures as due to normative or external causes would be unrelated to the negative outcomes. Further, we expected that importance and internal attributions would mediate the relationship between individuals’ level of OCD symptoms and distress and recurrence of unwanted thoughts. Results largely supported the hypotheses: importance and internal attributions predicted distress and the recurrence of unwanted thoughts, while normative and external attributions did not. Additionally, importance attributions mediated the relationship between OCD status and both distress and recurrence of unwanted thoughts, while internal attributions mediated the OCD status-distress relationship.

These results are consistent with cognitive theories of OCD, especially the idea that the cognitions tied to experiences with unwanted thoughts are a primary factor in the maintenance of OCD. According to leading cognitive theories of OCD, nearly all people can and do experience the same types of unwanted thoughts, but only a few people misinterpret their unwanted thoughts in ways that promote OCD symptoms (Rachman, 1997, 1998). The current study supports an analogous model in that nearly all participants experienced some degree of failure to suppress unwanted thoughts; yet it was the maladaptive attributions made in response to this common experience that predicted who would experience greater distress and return of unwanted thoughts. The results suggest an addition to cognitive theories of OCD to include misattribution of attempts to control thoughts as a possible route to escalated distress and repetitiveness of unwanted thoughts, in addition to misinterpretation of the unwanted thought itself. The ability of attributions to predict future negative consequences of thought suppression is an especially important supplement to previous research.

The mediation results provide considerable support for attributions as a possible mechanism to explain how OCD symptoms can be connected to difficulties with unwanted thoughts after suppression. However, it is important to note that the current mediation results cannot support causal conclusions, so future tests that directly manipulate attributions are needed. Notwithstanding, the current research extends existing theoretical models of thought suppression by explicitly distinguishing attributions for unsuccessful thought suppression from unsuccessful thought suppression itself. The initial exciting advance in thought suppression theory involved Wegner’s dual-process model, which was often heuristically interpreted by researchers as a simple linear association whereby a suppression attempt leads to increased thought recurrence. While this model has some empirical support (Abramowitz et al., 2001), there have also been many inconsistent findings. The current study suggests that attributions may add a powerful feature to the model, and allow flexibility in predicting variation within an individual from one suppression attempt to another. Not only does this model potentially help explain the negative consequences of thought suppression associated with OCD symptoms, it also may clarify why individuals sometimes try to suppress unwanted thoughts without experiencing the expected negative outcomes – presumably their attributions are healthier.

Our results converge with research by Tolin et al. (2002) by replicating (in an analogue sample) their finding that a group with OCD rated internal attributions for unsuccessful thought suppression higher than did a non-anxious sample. The results also extend the work of Purdon et al. (2005), who found that negative interpretations of recurrences of thoughts predicted distress and suppression effort. This study builds on this previous work by testing mediation models to understand the relationships among OCD symptoms, attributions, and concurrent as well as future distress and recurrence of unwanted thoughts. Our finding that attributions predict the recurrence of unwanted thoughts is especially noteworthy, given that this central characteristic of OCD has not been reliably predicted in previous thought suppression studies.

This study introduced a new approach for the measurement of thoughts during thought suppression by recording the frequency and duration of four thoughts at one time. A challenge in the thought suppression field has been the difficulty of simultaneously measuring more than one thought, yet it is clear that many people experience a flood of unwanted thoughts, not one in isolation. Because of the methodology used in this study, we were able to evaluate whether the findings were specific to one particular type of thought or suppression instruction. We found that the relationships held even when we systematically excluded one thought at a time from the model (e.g., white bear, car accident, etc.). Although there were mean differences in attributions following different thoughts, the findings suggest that the characteristics of unpleasantness, perceived immorality and relevance to one’s usual thoughts (the characteristics distinguishing the four thoughts used in the current study) have little individual influence in determining the relationships between attributions and distress and recurrence of thoughts. Purdon (1999) has previously raised concerns about whether thought suppression findings using personally-irrelevant thoughts would apply to clinical disorders that are typified by self-relevant thoughts. This study suggests that such applications may be reasonable.

Similarly, we found the results to be invariant across different types of suppression instructions. This test was significant because as Abramowitz et al. (2001) and Purdon and Clark (2000) have warned, participants tend to suppress regardless of whatever control instructions they receive (even explicit instructions not to suppress). As a result, it has been uncertain whether the effects of suppressing by one’s own volition differ from being instructed to suppress. The current study speaks to this issue by comparing the effects of explicit instructions to suppress with monitoring instructions, which produced self-initiated suppression (perhaps a more externally valid form of suppression). Results were the same across instruction conditions, suggesting that it is the attributions one makes - rather than how suppression was initiated - that predict negative outcomes.

Although the relationships between attributions and distress and thought recurrence were invariant, we found interesting patterns when examining the mean levels of attributions after different types of unwanted thoughts and suppression instructions. Specifically, type of thought resulted in different mean levels of attributions endorsed, while suppression instructions led to mostly similar attributions. For each of the different thoughts, normative attributions were more common than external attributions, which in turn were more common than internal attributions. However, the relative endorsement of importance attributions compared to these other categories varied according to the thought. Notably, the result suggested that importance attributions are more likely when failing to suppress negative (relative to neutral) thoughts.

Existing cognitive interventions for OCD are efficacious, but have struggled to demonstrate additional clinical utility over standard exposure and response prevention treatments (Clark, 2005). Perhaps interventions specific to modifying attributions for suppression failures may add to existing cognitive approaches (which tend to focus on modifying interpretations about unwanted thoughts). Another testable hypothesis is that changing attributions may help change clients’ focus from an avoidance motivation (“I need to get rid of this thought!”) to more of an approach motivation focusing on the struggle itself (“How am I reacting to this struggle with the thought?”). Some researchers have suggested similar ideas regarding the use of mindfulness techniques with suppression (e.g., Beevers, Wenzlaff, Hayes, & Scott, 1999).

This study also raises some interesting questions about what should count as “healthier” attributions. Curiously, we found that participants with high levels of OCD symptoms endorsed greater levels of external attributions than did non-anxious participants; this did not parallel Tolin and his colleagues’ (2002) findings of equal endorsement among the groups. We also unexpectedly found that external and normative attributions were each positively correlated with at least one of the so-called maladaptive attribution categories (internal and/or importance). While these correlations were fairly small, it is possible that this overlap picked up on a general maladaptive response style that we did not anticipate. Simply being motivated to make attributions for unsuccessful suppression may be important. The finding of positive relationships between the maladaptive and so-called healthier attributions leaves it an open question what types of attributions might predict more positive outcomes. One possibility is that attributions that actively negate the maladaptive attributions will predict better outcomes (i.e., “I was not able to keep the thought out of my mind, but that doesn’t mean there is something wrong with the way I think.”).

Results from the present study must be interpreted carefully as the study employed a young, non-clinical student sample. Additionally, we were unable to tease apart whether the effects were specific to OCD symptoms, or generalizable to negative affect, anxiety or depression more generally. While cognitive theories of OCD provide a compelling fit for the role of attributions in escalating distress and the recurrence of unwanted thoughts, this may be characteristic of psychopathology more broadly.

The current study found that importance and internal attributions predicted distress and recurrence of unwanted thoughts after failed thought suppression attempts. Further, these attributions mediated the relationship between OCD symptoms and negative thought suppression outcomes. Future research examining the development and malleability of attributions for unsuccessful thought suppression as well as what constitutes ‘healthy’ attributions will help to determine the clinical importance of attributions in breaking the vicious cycle of OCD symptoms and recurrent, unwanted thoughts.

Acknowledgments

The authors are thankful for the feedback provided by Gerald Clore, the programming assistance provided by Andrew Magee and research assistance and feedback provided by members of the Teachman Program for Anxiety, Cognition & Treatment Lab. This research was supported in part by an NIMH R03 PA-03-039 grant to Bethany Teachman.

Footnotes

We use “interpretation” to refer to the meaning or significance of a recurring thought, whereas “attribution” is used to ascribe a causal explanation for why the thought recurred.

Out of 156 original participants, 30 participants’ attributions data were lost due to computer error, so these participants were excluded from the analyses.

We conducted an exploratory factor analysis using principle axis factoring (following OCCWG, 2005) with promax rotation. We retained four factors accounting for 54% of the total variance after inspection of a scree plot and the eigenvalues. At the item level, we retained items with loadings of at least .40 that loaded exclusively on one of the four factors. This resulted in retention of 17 of the original 21 items. All items loaded on factors as hypothesized, although items for two originally hypothesized factors (internal and immorality) merged to create one factor (internal).

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Abramowitz JS, Tolin DF, Street GP. Paradoxical effects of thought suppression: A meta-analysis of controlled studies. Clinical Psychology Review. 2001;21:683–703. doi: 10.1016/s0272-7358(00)00057-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amir N, Cashman L, Foa EB. Strategies of thought control in obsessive-compulsive disorder. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 1997;35:775–777. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(97)00030-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babyak MA. What you see may not be what you get: A brief, nontechnical introduction to overfitting in regression-type models. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2004;66:411–421. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000127692.23278.a9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baron RM, Kenny DA. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1986;51:1173–1182. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.51.6.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Steer RA. Manual for the revised Beck Depression Inventory. San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corporation; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Beevers CG, Wenzlaff RM, Hayes AM, Scott WD. Depression and the ironic effects of thought suppression: Therapeutic strategies for improving mental control. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 1999;6:133–148. [Google Scholar]

- Belloch A, Morillo C, Gimenez A. Effects of suppressing neutral and obsession-like thoughts in normal subjects: beyond frequency. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2004;42:841–857. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2003.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark DA. Focus on cognition in “cognitive behavior therapy” for OCD: Is it really necessary? Cognitive Behaviour Therapy. 2005;34:131–139. doi: 10.1080/16506070510041194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foa EB, Huppert JD, Leiberg S, Langner R, Kichic R, Hajcak G, et al. The Obsessive-Compulsive Inventory: Development and validation of a short version. Psychological Assessment. 2002;14:485–496. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kyrios M. A cognitive perspective on the etiology of obsessive-compulsive disorder; 2000, November; Paper presented at the annual meeting of the Association for the Advancement of Behavior Therapy; New Orleans, LA. [Google Scholar]

- Little RJA, Rubin DB. Statistical analysis with missing data. New York: John Wiley; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Obsessive Compulsive Cognitions Working Group. Psychometric validation of the obsessive beliefs questionnaire and interpretation of intrusions inventory – Part 2: Factor analyses and testing of a brief version. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2005;43:1527–1542. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2004.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Purdon C. Appraisal of obsessional thought recurrences: Impact on anxiety and mood states. Behavior Therapy. 2001;32:47–64. [Google Scholar]

- Purdon C. Empirical investigations of thought suppression. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry. 2004;35:121–136. doi: 10.1016/j.jbtep.2004.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Purdon C, Clark DA. Metacognition and obsessions. Clinical Psychology and Psychotherapy. 1999;6:96–101. [Google Scholar]

- Purdon C, Clark DA. White bears and other elusive intrusions: Assessing the relevance of thought suppression for obsessional phenomena. Behavior Modification. 2000;24:425–453. doi: 10.1177/0145445500243008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Purdon, Clark Suppression of obsession-like thoughts in nonclinical individuals: impact on thought frequency, appraisal and mood state. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2001;39:1163–1181. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(00)00092-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Purdon C, Rowa K, Antony MM. Thought suppression and its effects on thought frequency, appraisal and mood state in individuals with obsessive-compulsive disorder. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2005;43:93–108. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2003.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rachman S. A cognitive theory of obsessions. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 1997;35:793–802. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(97)00040-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rachman S. A cognitive theory of obsessions: Elaborations. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 1998;36:385–401. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(97)10041-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rachman S, de Silva P. Abnormal and normal obsessions. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 1978;16:233–248. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(78)90022-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rachman S, Hodgson R. Obsessions and compulsions. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Salkovskis PM. Obsessional-compulsive problems: A cognitive-behavioural analysis. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 1985;23:571–583. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(85)90105-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salkovskis PM. Cognitive-behavioural factors and the persistence of intrusive thoughts in obsessional problems. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 1989;27:677–682. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(89)90152-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salkovskis PM. Psychological approaches to the understanding of obsessional problems. In: Swinson RP, Rachman Antony S, Richter MA, editors. Obsessive-compulsive disorder: Theory, research and treatment. New York: Guilford; 1998. pp. 33–50. [Google Scholar]

- Shafran Thordarson, Rachman Thought-action fusion in obsessive-compulsive disorder. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 1996;10:379–391. [Google Scholar]

- Tolin DF, Abramowitz JS, Hamlin C, Foa EB, Synodi DS. Attributions for thought suppression failure in obsessive-compulsive disorder. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 2002;26:505–517. [Google Scholar]

- Watson D, Clark LA. The PANAS-X: Manual for the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule. Expanded Form; The University of Iowa: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Wegner DM. Ironic processes of mental control. Psychological Review. 1994;101:34–52. doi: 10.1037/0033-295x.101.1.34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wells, Davies The Thought Control Questionnaire: A measure of individual differences in the control of unwanted thoughts. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 1994;32:871–878. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(94)90168-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wenzlaff RM, Wegner DM. Thought suppression. Annual Review of Psychology. 2000;51:59–91. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.51.1.59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]