Abstract

RNA can act as a template for DNA synthesis in the reverse transcription of retroviruses and retrotransposons1 and in the elongation of telomeres2. Despite its abundance in the nucleus, there has been no evidence for a direct role of RNA as a template in the repair of any chromosomal DNA lesions, including DNA double-strand breaks (DSBs), which are repaired in most organisms by homologous recombination or by non-homologous end joining3. An indirect role for RNA in DNA repair, following reverse transcription and formation of a complementary DNA, has been observed in the non-homologous joining of DSB ends4,5. In the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae, in which homologous recombination is efficient3, RNA was shown to mediate recombination, but only indirectly through a cDNA intermediate6,7 generated by the reverse transcriptase function of Ty retrotransposons in Ty particles in the cytoplasm8. Although pairing between duplex DNA and single-strand (ss)RNA can occur in vitro9,10 and in vivo11, direct homologous exchange of genetic information between RNA and DNA molecules has not been observed. We show here that RNA can serve as a template for DNA synthesis during repair of a chromosomal DSB in yeast. The repair was accomplished with RNA oligonucleotides complementary to the broken ends. This and the observation that even yeast replicative DNA polymerases such as α and δ can copy short RNA template tracts in vitro demonstrate that RNA can transfer genetic information in vivo through direct homologous interaction with chromosomal DNA.

We predicted that if RNA could participate directly in the repair of a chromosomal DSB, this would require DNA synthesis on the RNA template. Such activity might be mediated by a reverse transcriptase able to function in the nucleus on the chromosome or possibly by a DNA polymerase. In RNA–protein complexes from LINE1 retrotransposons, retrotranscription can be primed in the nucleus by the 3′ end of a chromosomal break12. However, break repair using LINE1 elements does not require RNA/DNA complementarity and is, therefore, mutagenic. On the other hand, it is unclear if DNA polymerases actually possess RNA-templated DNA synthesis activity in vivo, despite the ability of Escherichia coli Pol I (ref. 13), mammalian Pol γ (ref. 14), and human DNA pol-η-ι and -κ (ref. 15) to synthesize DNA on RNA templates in vitro. Here we explore the possibility that a DSB can be repaired by homologous RNA and that chromosomal DNA synthesis can occur on RNA templates in the yeast S. cerevisiae.

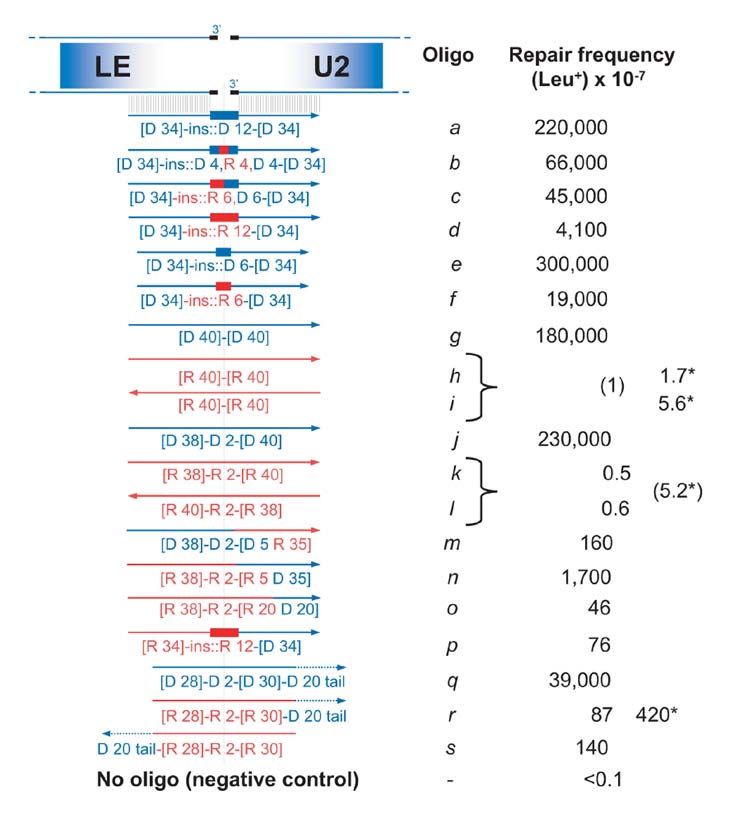

We first investigated DNA synthesis across a short RNA tract during the repair of a chromosomal DSB, using the capacity of ssDNA oligonucleotides to serve as a template for efficient DSB repair16,17. A site-specific DSB was induced within the LEU2 gene by overexpression of HO endonuclease18. Following DSB induction, cells were transformed with ssDNA oligonucleotides that were designed (see Fig. 1) to join LEU2 ends and introduce a unique, in-frame 12-base insert containing 0, 4, 6 or 12 RNA bases (a, b, c and d, respectively), or a 6-base insert with 0 or 6 RNA bases (e and f). To accomplish DSB repair and restore a functional LEU2 gene, the insert sequence must be used as a template. Remarkably, repair by b (containing 4 ribonucleotides) was only a factor of 3 lower than repair by the DNA-only control (a). The frequencies decreased with increasing RNA-tract length (b, c, d, Fig. 1). The appearance of the oligonucleotide sequence in the Leu+ transformants (see ‘Verification’ in Supplementary Table 2a) suggests that the RNA-containing molecules participate directly in the repair. This contrasts with the observation that two ribonucleotides at the mating type locus of Schizosaccharomyces pombe seem to block DNA replication and lead to a site-specific DSB19. However, the reduced transformation frequency with increased size of RNA might be due to a higher likelihood of replication arrest. If so, it is unlikely that cDNA generated by Ty reverse transcriptase of the RNA-containing oligonucleotides would be the source of DSB repair.

Figure 1. Repair of a DSB by RNA-containing oligonucleotides.

The diagram shows the broken LEU2 chromosomal DNA along with the oligonucleotides containing DNA (D; blue) or RNA (R; red) sequences that were used to repair the DSB, and corresponding frequencies of LEU2 repair. The HO cutting site (124 bp) is split in two halves shown as thicker short black lines (not to scale). Oligonucleotides are shown as lines with arrows at the 3′ end; nucleotide inserts are shown as thick lines; dotted lines indicate non-homologous tails. Potential for homologous pairing is presented as short, thin parallel vertical lines. Numbers of nucleotides homologous to the LEU2 sequence are indicated in square brackets. Insertions are indicated by ‘ins::’; a comma separates DNA from RNA bases within the insertions; a hyphen separates the different parts of the oligonucleotides. Oligonucleotide sequences are given in Supplementary Table 1. Presented are numbers of Leu+ transformants per 107 viable cells resulting from targeting by 1 or 5* (adjacent column) nmoles of oligonucleotides a to s. Targeting frequencies with a pair of oligonucleotides (connected by braces) are shown in parentheses. Confidence intervals, as well as results of sequence verification are provided in Supplementary Table 2a.

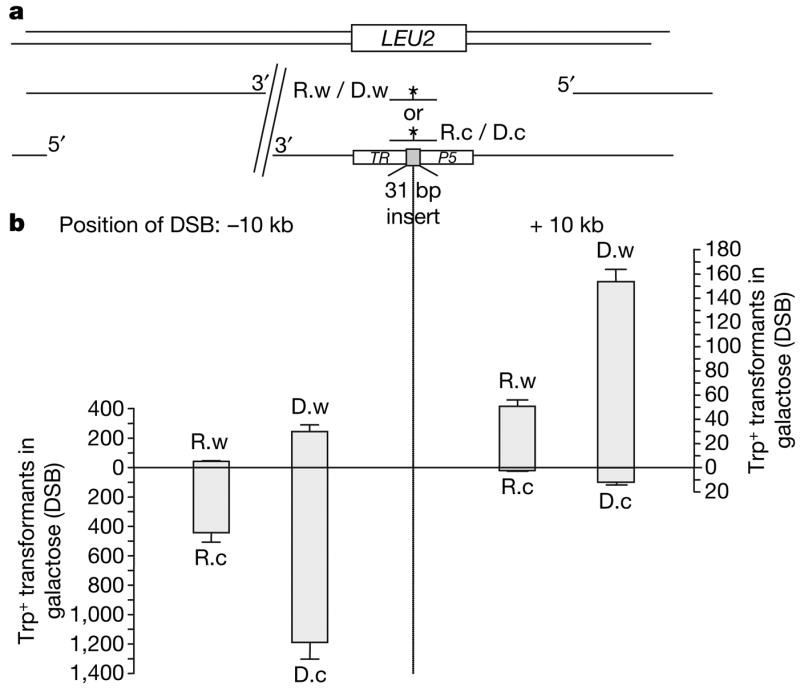

To exclude this possibility, that RNA-containing oligonucleotides were copied into cDNA before interacting with the DSB ends, we used our recent finding that a DSB can activate strand-biased targeting by ssDNA oligonucleotides with homology to a distant site17. Because many kilobases (kb) of the 5′ strand can be degraded before repair3, there is a bias for the oligonucleotide complementary to the 3′ strand. If a cDNA intermediate were formed from ssRNA-containing oligonucleotides, the observed bias should be opposite to that with the corresponding ssDNA oligonucleotides, and there would be no bias if dsDNA were formed. As shown in Fig. 2, targeting with RNA-containing oligonucleotides was biased in favour of the oligonucleotide complementary to the 3′ end of the break, similar to DNA-only oligonucleotides. No bias was detected without DSB induction (Supplementary Table 3). Transfer of the BamHI site contained in R.w and R.c (Fig. 2a) was confirmed in 28/30 transformants. We conclude that yeast cells have the ability to use RNA embedded in DNA as a template within the chromosome.

Figure 2. Strand bias of oligonucleotide targeting to sites distant from the DSB.

a, System to detect oligonucleotide strand bias in yeast diploid strains. One copy of chromosome VII with the TRP5 locus inactivated by a 31 bp frameshift insertion plus an I-SceI-induced DSB either 10 kb upstream or downstream17. The Trp+ phenotype can be restored by the oligonucleotides R.w or R.c (corresponding to the ‘Watson’ or ‘Crick’ strand in the TRP5 coding sequence), containing six central bases of RNA, or only DNA (D.w and D.c), while the intact copy of chromosome VII, in which TRP5 is replaced by LEU2, provides a template for repair of the DSB. A restriction site created by the oligonucleotides is indicated by an asterisk b, Number of Trp+ transformants per 107 viable cells resulting from targeting 1 nmole of R.w, R.c, D.w or D.c following DSB induction. Presented are mean + s.d. from six independent experiments.

We then examined repair by RNA-only molecules that were homologous to both sides of a DSB. As shown in Fig. 1, the Leu+ transformation frequency with five nmoles of oligonucleotides h or i reached 5 × 10−7, and restoration of LEU2 sequence was precise (in 26/27 clones tested). In the absence of oligonucleotides, the frequency of Leu+ colonies was ~1 × 10−8 and in all tested isolates (16/16) the Leu+ phenotype was due to imprecise non-homologous end joining causing small insertions or deletions (Supplementary Table 2a). Thus, ssRNA oligonucleotides are estimated to increase the precise repair of a DSB in LEU2 by over 500-fold. Similar RNA oligonucleotides containing 2-base substitutions in the centre (k and l) gave comparable Leu+ transformation frequencies (Fig. 1). The mutations were precisely transferred (Supplementary Table 2a), indicating DNA synthesis across the RNA templates.

Several oligonucleotides were used to better understand DSB repair by RNA. The minimum size for repair by RNA-only molecules was greater than 45 bases (k.45 and l.45 in Supplementary Table 2a). The repair was enhanced by the presence of DNA at one end of the RNA oligonucleotides, regardless of whether the DNA was homologous (m, n, o and p) or non-homologous (r and s) to the DSB ends. Repair frequencies by oligonucleotides that required DNA synthesis through long RNA tracts were much lower than those of corresponding oligonucleotides requiring less synthesis on RNA (Fig. 1, compare n with p; also compare b, c, d and f). RNA oligonucleotides containing DNA homologous to a DSB end at their 5′ (m) or 3′ end (n) were over 100 and 1,000-fold more efficient, respectively, than the RNA-only molecules (Fig. 1). One possible explanation is that rather than simply enhancing annealing, the homologous DNA can provide a DNA duplex region close to the 3′ end of the break that could facilitate polymerase binding (compare n with m and with o). It is also possible that the DNA end could prevent end-degradation, especially from the 3′ end (compare m with n, and o with r and s) (Fig. 1). In agreement with the protection idea, the presence of a 20-base non-homologous DNA tail at the 3′ end of an oligonucleotide containing 60 nucleotides of homologous RNA (r and s), but not a 3-nucleotide tail (r3), increased repair by a factor of 100 when compared with the RNA-only oligonucleotides (k and l) containing an even longer RNA stretch of homology (Fig. 1 and Supplementary Table 2a). The transformation differences associated with the longer DNA tail could be due to protection from 3′ → 5′ exoRNases, which have a major role in RNA surveillance20. Deletion of the non-essential 3′ → 5′ exoRNase RRP6 did not increase transformation with an RNA-only oligonucleotide (k) (Supplementary Table 4). However, because most 3′ → 5′ exoRNases are coded by essential genes in yeast, further genetic studies are required to examine the potential involvement of these enzymes. Because RNA-templated repair must involve RNA–DNA duplex intermediates, we also examined the possible role of RNases H1 (RNH1) and H2 (RNH35), which can efficiently degrade messenger RNA paired with DNA11. There was no increase in RNA oligonucleotide-mediated repair for the single or the double mutants (Supplementary Table 4).

Targeting of RNA oligonucleotides was stimulated by the DSB by at least 100-fold (compare n or r added to cells in galactose medium to induce the HO-endonculease versus no galactose, Supplementary Tables 2a and b) and occurred independently from the strand invasion function of Rad51 (Supplementary Table 4). The targeting was also independent of chromosomal locus because a DSB induced within TRP5 was also precisely repaired by RNA oligonucleotides (T2 and T4 in Supplementary Table 2c).

Except for telomerase genes, the only genes in yeast known to code for reverse transcriptases are those contained in Ty elements. Deletion of the SPT3 gene, which is essential for transposition and transcription of Ty1 and Ty2 elements4,21, did not affect RNA-templated repair (Supplementary Table 5). We conclude that Ty reverse transcription has at most a minor role in DSB repair events mediated by a homologous RNA template. Deletion of telomerase genes EST2 or EST1 (ref. 22) also did not affect transformation by the RNA-containing oligonucleotides (Supplementary Table 5). This contrasts with the strong stimulation of Ty cDNA synthesis and transposition in an est2-null mutant8.

It is also possible that DNA synthesis during RNA-templated repair is accomplished by DNA polymerases. However, deletion of individual nonessential yeast DNA polymerase genes (POL4, REV1, REV3, RAD30 or MIP1)23, as well as double and triple deletion mutants of translesion DNA polymerase REV1, REV3 and RAD30 genes, did not alter transformation by RNA-containing oligonucleotides (Supplementary Table 5). We conclude that the ability to synthesize DNA on an RNA tract during repair could be a redundant function among polymerases and/or a function of one or more essential replicative DNA polymerases.

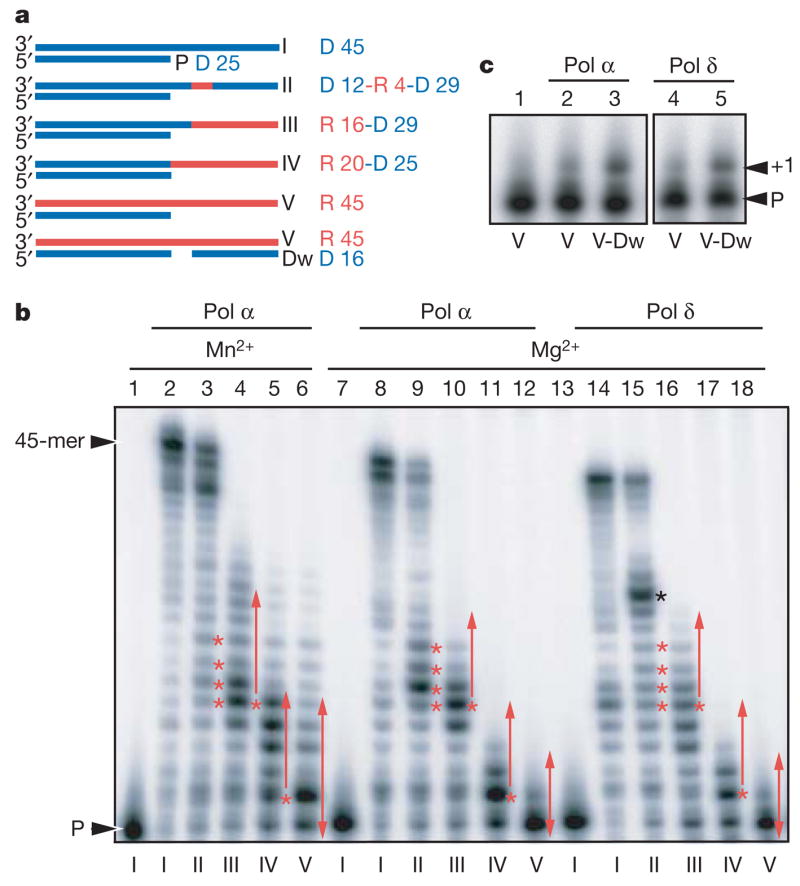

We therefore examined the ability of yeast DNA polymerases α and δ to copy templates with sequences corresponding to oligonucleotides a and b containing 0 or 4 RNA bases (Fig. 3a and Supplementary Table 1). Both polymerases copied all 4 ribonucleotides and generated full-length products (Fig. 3b; compare lanes 8 and 9, and 14 and 15). Synthesis by Pol α, but not by Pol δ (not shown), was stimulated by Mn2+ (Fig. 3b, lanes 2–3 versus 8–9). These polymerases also partially copied a template (IV) in which the RNA tract starts at the first single-strand template position (Fig. 3b, lanes 11 and 17). Greater extension occurred when synthesis started from a DNA tract (for example, substrate III, lanes 10 and 16, and substrate II containing a 4 ribonucleotide tract (R 4), lanes 9 and 15). Although not tested, the DNA polymerase co-factor proliferating cell nuclear antigen might enhance synthesis further, because PCNA enhances Pol δ processivity when copying DNA. On an RNA-only template (V), Pol α incorporated up to 12 bases in the presence of Mn2+ (lane 6), and both polymerases added a nucleotide with or without the presence of a downstream oligonucleotide (Dw), which created a gap, if Mg2+ was present (Fig. 3b, lanes 12 and 18, and Fig. 3c). When the efficiency of copying the 4-nucleotide template tract was determined (as described in Section 3.1 in ref. 24), Pol δ extended 80% of the products beyond R 4 and 76% of the products beyond the equivalent D 4 tract. Thus, the RNA tract was copied by Pol δ as efficiently as the corresponding DNA tract. Interestingly, once the R4 tract was copied by Pol δ, further elongation was impeded by the presence of the RNA–DNA duplex upstream of the Pol δ active site (for example, see band highlighted with a black asterisk in Fig. 3b, lane 15). Pol α also copied the R4 tract, but less efficiently (27% of products beyond R4 compared with 92% of products beyond D4). Moreover, Pol α required 20-fold more binding–synthesis-dissociation cycles (determined as described24) than Pol δ to completely bypass R4. Thus, Pol δ may be the more likely candidate for reverse transcriptional repair of a DSB in vivo. It will be interesting to assess the effects of specific replicative DNA polymerase mutants on DSB repair by RNA-containing molecules.

Figure 3. Synthesis by Pol α and Pol δ across RNA templates.

a, Substrates consist of DNA (D; blue) and/or RNA (R; red) and include primer P (same in all substrates). b, Lanes 1, 7, 13, template I, no enzyme; lanes 2–6 and 8–12, Pol α products; lanes 14–18, Pol δ products. Reactions use templates: I in lanes 2, 8, 14; II in lanes 3, 9, 15; III in lanes 4, 10 and 16; IV in lanes 5, 11, and 17; and V in lanes 6, 12, and 18. Red asterisks, ribonucleotide positions in template II and first ribonucleotide position in templates III and IV. Red arrows, RNA tracts in templates III, IV and V. The black asterisk in lane 15 marks where Pol δ was impeded when the RNA–DNA duplex is upstream of the polymerase active site. c, Synthesis on a gapped substrate. Lane 1, template with no enzyme V; lanes 2 and 4, products with template V and indicated enzyme; lanes 3 and 5, products with gapped substrate (V-Dw). Extension of the primer by one nucleotide is shown as +1.

The finding of in vivo and in vitro DNA synthesis on RNA-containing oligonucleotides is relevant to situations where RNA might appear within DNA in vivo, as shown for the mammalian mitochondrial genome25. The inclusion of RNA bases could occur during normal DNA metabolic reactions, as indicated by the ability of several DNA polymerases to incorporate ribonucleotides in vitro25,26 and the ability of DNA ligase I to ligate RNA bases into DNA during Okazaki fragment maturation in vitro27.

The RNA-templated DSB repair presented here is clearly distinct from previously described RNA/cDNA-mediated DSB repair processes4–7,12. We show that there is no barrier to the direct transfer of information from RNA templates to chromosomal DNA. On the basis of this newly discovered RNA capability, we suggest that endogenous RNA could have a direct role in repairing lesions during or after transcription, especially given its high local concentration. Our results set the stage for understanding how direct, homology-driven transfer of endogenous RNA information to DNA may occur.

The ability of RNA to transfer genetic information to homologous chromosomal DNA could lead to new directions in gene targeting, given that RNA can be amplified at will within cells. Moreover, RNA as a homologous template in DNA repair may contribute to both genome integrity and evolution.

METHODS

DSB induction and targeting with oligonucleotides

The RNA-containing oligonucleotides and the DNA oligonucleotides used to repair the HO or the I-SceI induced DSB, or to target a sequence distant from an induced I-SceI break, are described in Supplementary Table 1. DSB induction (Supplementary Methods) and targeting with oligonucleotides (1 or 5 nmoles), using a lithium acetate transformation protocol, were done as previously described16,17,28, with the only difference being that cells to be transformed with RNA-containing oligonucleotides were washed five times with RNase-free water to dilute potential traces of RNases. All solutions and equipment used for the transformation were RNase free. Cells from each oligonucleotide transformation were plated to either selective Leu− or Trp− media and to synthetic complete media to determine culture viability. We excluded the possibility that DNA contamination in our RNA-containing oligonucleotides was responsible for the transfer of genetic information (Supplementary Fig. 1). Details about yeast strains are presented in the Supplementary Methods section and genetic standard methods are as described16,28.

DNA synthesis reactions

Reactions (20 μl) with 5 nM S. cerevisiae Pol α (catalytic subunit), purified as described29, contained 20 mM Tris-HCl (pH8), 10 mM MgCl2 or 0.5 mM MnCl2, 2 mM DTT, 0.2 mg ml−1 BSA, 50 nM dNTPs and 200 nM oligonucleotide substrates prepared as described in Supplementary Table 1. Reactions with the 3-subunit S. cerevisiae Pol δ (gift from P. M. J. Burgers) were the same except for the use of 40 mM Tris (pH 8), 5 mM MgCl2, 0.1 mg ml−1 BSA and 75 mM NaCl. After a 6 min incubation at 30 °C, reaction mixtures were quenched by adding 20 μl of 99% formamide, 5 mM EDTA, 0.1% xylene cyanole, 0.1% bromophenol blue, resolved by electrophoresis in a 12% denaturing polyacrylamide gel and visualized using a Molecular Dynamics PhosphorImager.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Information is linked to the online version of the paper at www.nature.com/nature.

Acknowledgments

We thank J. E. Haber for yeast strain YFP17 and P. M. J. Burgers for yeast DNA polymerase δ. We thank C. Halweg and W. C. Copeland for suggestions; K. L. Adelman, J. W. Drake and A. Sugino for critical reading of the manuscript; and J. R. Snipe and G. K. Chan for technical assistance. Research support was from National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (NIH) intramural research funds.

Footnotes

Author Information Reprints and permissions information is available at www.nature.com/reprints. The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.Baltimore D. Retroviruses and retrotransposons: the role of reverse transcription in shaping the eukaryotic genome. Cell. 1985;40:481–482. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(85)90190-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Autexier C, Lue NF. The structure and function of telomerase reverse transcriptase. Annu Rev Biochem. 2006;75:493–517. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.75.103004.142412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Paques F, Haber JE. Multiple pathways of recombination induced by double-strand breaks in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 1999;63:349–404. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.63.2.349-404.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Teng SC, Kim B, Gabriel A. Retrotransposon reverse-transcriptase-mediated repair of chromosomal breaks. Nature. 1996;383:641–644. doi: 10.1038/383641a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Moore JK, Haber JE. Capture of retrotransposon DNA at the sites of chromosomal double-strand breaks. Nature. 1996;383:644–646. doi: 10.1038/383644a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Derr LK, Strathern JN. A role for reverse transcripts in gene conversion. Nature. 1993;361:170–173. doi: 10.1038/361170a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nevo-Caspi Y, Kupiec M. cDNA-mediated Ty recombination can take place in the absence of plus-strand cDNA synthesis, but not in the absence of the integrase protein. Curr Genet. 1997;32:32–40. doi: 10.1007/s002940050245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lesage P, Todeschini AL. Happy together: the life and times of Ty retrotransposons and their hosts. Cytogenet Genome Res. 2005;110:70–90. doi: 10.1159/000084940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kasahara M, Clikeman JA, Bates DB, Kogoma T. RecA protein-dependent R-loop formation in vitro. Genes Dev. 2000;14:360–365. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zaitsev EN, Kowalczykowski SC. A novel pairing process promoted by Escherichia coli RecA protein: inverse DNA and RNA strand exchange. Genes Dev. 2000;14:740–749. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Huertas P, Aguilera A. Cotranscriptionally formed DNA:RNA hybrids mediate transcription elongation impairment and transcription-associated recombination. Mol Cell. 2003;12:711–721. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2003.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Morrish TA, et al. DNA repair mediated by endonuclease-independent LINE-1 retrotransposition. Nature Genet. 2002;31:159–165. doi: 10.1038/ng898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ricchetti M, Buc H. E coli DNA polymerase I as a reverse transcriptase. EMBO J. 1993;12:387–396. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb05670.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Murakami E, et al. Characterization of novel reverse transcriptase and other RNA-associated catalytic activities by human DNA polymerase γ: importance in mitochondrial DNA replication. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:36403–36409. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M306236200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Franklin A, Milburn PJ, Blanden RV, Steele EJ. Human DNA polymerase-η, an A-T mutator in somatic hypermutation of rearranged immunoglobulin genes, is a reverse transcriptase. Immunol Cell Biol. 2004;82:219–225. doi: 10.1046/j.0818-9641.2004.01221.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Storici F, Durham CL, Gordenin DA, Resnick MA. Chromosomal site-specific double-strand breaks are efficiently targeted for repair by oligonucleotides in yeast. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:14994–14999. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2036296100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Storici F, Snipe RJ, Chan GK, Gordenin DA, Resnick MA. Conservative repair of a chromosomal double-strand break by single-strand DNA through two steps of annealing. Mol Cell Biol. 2006;26:7645–7657. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00672-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Paques F, Leung WY, Haber JE. Expansions and contractions in a tandem repeat induced by double-strand break repair. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:2045–2054. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.4.2045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vengrova S, Dalgaard JZ. The wild-type Schizosaccharomyces pombe mat1 imprint consists of two ribonucleotides. EMBO Rep. 2006;7:59–65. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7400576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Houseley J, LaCava J, Tollervey D. RNA-quality control by the exosome. Nature Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2006;7:529–539. doi: 10.1038/nrm1964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Boeke JD, Styles CA, Fink G. R Saccharomyces cerevisiae SPT3 gene is required for transposition and transpositional recombination of chromosomal Ty elements. Mol Cell Biol. 1986;6:3575–3581. doi: 10.1128/mcb.6.11.3575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Smogorzewska A, de Lange T. Regulation of telomerase by telomeric proteins. Annu Rev Biochem. 2004;73:177–208. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.73.071403.160049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shcherbakova PV, Kunkel TA. DNA. In: DePamphilis ML, editor. Replication in Eukaryotic Cells and its Relevance to Human Disease. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; Cold Spring Harbor, New York: 2006. pp. 391–410. [Google Scholar]

- 24.McCulloch SD, Kunkel TA. Multiple solutions to inefficient lesion bypass by T7 DNA polymerase. DNA Repair. 2006;5:1373–1383. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2006.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yang MY, et al. Biased incorporation of ribonucleotides on the mitochondrial L-strand accounts for apparent strand-asymmetric DNA replication. Cell. 2002;111:495–505. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)01075-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nick McElhinny SA, Ramsden DA. Polymerase mu is a DNA-directed DNA/RNA polymerase. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23:2309–2315. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.7.2309-2315.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rumbaugh JA, Murante RS, Shi S, Bambara RA. Creation and removal of embedded ribonucleotides in chromosomal DNA during mammalian Okazaki fragment processing. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:22591–22599. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.36.22591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Storici F, Resnick MA. The delitto perfetto approach to in vivo site-directed mutagenesis and chromosome rearrangements with synthetic oligonucleotides in yeast. Methods Enzymol. 2006;409:329–345. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(05)09019-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Niimi A, et al. Palm mutants in DNA polymerases α and η alter DNA replication fidelity and translesion activity. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:2734–2746. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.7.2734-2746.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Information is linked to the online version of the paper at www.nature.com/nature.