Abstract

This paper explores the ethical and conceptual implications of the findings from an empirical study of decision-making capacity in anorexia nervosa. In the study, ten female patients aged 13 to 21 years with a diagnosis of anorexia nervosa, and eight sets of parents, took part in semi-structured interviews. The purpose of the interviews was to identify aspects of thinking that might be relevant to the issue of competence to refuse treatment. All the patient participants were also tested using the MacCAT-T test of competence. This is a formalised, structured interviewer-administered test of competence, which is a widely accepted clinical tool for determining capacity. The young women also completed five brief self-administered questionnaires to assess their levels of psychopathology.

The issues identified from the interviews are described under two headings: difficulties with thought processing, and changes in values. The results suggest that competence to refuse treatment may be compromised in people with anorexia nervosa in ways that are not captured by traditional legal approaches or current standardised tests of competence.

Introduction

Anorexia nervosa is a serious disorder which causes high levels of morbidity and mortality (Harris & Barraclough, 1998; Ratnasuriya et al., 1991) . The diagnostic criteria for anorexia nervosa, as defined by the DSM-IV diagnostic criteria (American Psychiatric Association, 2000), are:

Refusal to maintain body weight at or above a minimally normal weight for age and height (eg, weight loss leading to maintenance of body weight less than 85% of that expected or failure to make expected weight gain during period of growth, leading to body weight less than 85% of that expected).

Intense fear of gaining weight or becoming fat, even though underweight.

Disturbance in the way in which one's body weight or shape is experienced, undue influence of body weight or shape on self-evaluation, or denial of the seriousness of the current low body weight.

In postmenarchal females, amenorrhea i.e., the absence of at least three consecutive cycles. (A woman is considered to have amenorrhea if her periods occur only following hormone, e.g., estrogen administration.)

Weight restoration and psychological treatment are the two main types of treatment methods currently used, with current consensus that each is complementary and essential for recovery.

It is a characteristic of anorexia nervosa that patients frequently refuse to engage with treatment, in spite of danger to health and life. This is so characteristic of the disorder that it is described in the DSM-IV, immediately following the list of criteria given above, as follows: “The individual is often brought to professional attention by family members after marked weight loss (or failure to make expected weight gains) has occurred. If individuals seek help on their own, it is usually because of their subjective distress over the somatic and psychological sequelae of starvation. It is rare for an individual with Anorexia Nervosa to complain of weight loss per se. Individuals with Anorexia Nervosa frequently lack insight into, or have considerable denial of, the problem and may be unreliable historians. It is therefore often necessary to obtain information from parents or other outside sources to evaluate the degree of weight loss and other features of the illness.” (American Psychiatric Association, 2000). Treatment is sometimes given compulsorily, although there is much variation in its use (The Royal College of Psychiatrists, 1992). Competence to make treatment decisions is an important issue to consider when the patient is at risk and compulsory treatment is being contemplated, but there is very little research to help in the understanding of this area in anorexia nervosa.

In this paper, we will describe a research study which was conducted using the MacCAT-T standardised test of competence and qualitative in-depth interviews with 10 young women with anorexia nervosa, and qualitative in-depth interviews with some of their mothers. The results of the MacCAT-T test will be considered, along with the participants’ views on two main themes: difficulties in thinking and values. On the issues of thinking and values alone, the descriptions of the problems in anorexia nervosa present a challenge to the current conception of competence. This current concept is largely based on understanding and reasoning and is well captured in by the MacCAT-T test, the gold standard for assessment of competence in the psychiatric setting. The results of the study show that anorexia nervosa can have complex and variable effects on concentration, beliefs, and thought processing, without affecting their ability to perform well on the MacCAT-T test of competence. At the same time, participants also report alterations of values, devaluation of other aspects of life, unusual values, and integration of anorexia nervosa into personal identity.

All these problems with thinking and values make the consideration of competence a complex task in anorexia nervosa. In the discussion, some different ways of looking at thinking and values will be considered.

Capacity and Competence

One key concept in the ethical and legal analysis relating to compulsory treatment is that of capacity to consent to, and refuse, treatment (Kennedy & Grubb, 2000). According to one approach, an adult patient with such capacity has the right to refuse any, even life saving, treatment 1. On this view, compulsory treatment is only justified if the patient lacks capacity (and the treatment is in the patient’s best interests). The general approach of most mental health statutes internationally, however, is to allow mental health professionals to detain and treat patients with a psychiatric disorder who are at risk to themselves or others, without consideration of whether or not the patients lack capacity (Dolan, 1998; Griffiths & Russell, 1998). There are exceptions to this, for example in New South Wales in Australia, where capacity is a key factor in the compulsory treatment of anorexia nervosa. This is because compulsory treatment for anorexia nervosa is excluded in the state mental health legislation, which has a relatively narrow scope. Treatment of anorexia nervosa without patient consent in New South Wales is therefore achieved using Guardianship orders, obtained by demonstrating to a court that the patient is unable to make his or her own treatment decisions due to the disorder (Carney et al., 2003; Griffiths & Russell, 1998).

When used outside the law courts, the legal concept of capacity is usually subsumed by a wider clinical notion of competence, which involves other psychological factors (Freedman, 1981; Nys et al., 2004; Tan & Jones, 2001). Grisso and Appelbaum (1998a) have distilled the main elements of competence as expressed in the law in most European and North American jurisdictions into the following factors in the clinical setting: Understanding, Appreciation (that it applies to self), Reasoning (which includes comparative and consequential reasoning), and Expressing a choice (Appelbaum, 1998; Grisso & Appelbaum, 1998b). Even in jurisdictions where mental health legislation enables compulsory treatment without consideration of capacity, the concept of capacity and competence remains important (Dolan, 1998). This is because many clinicians are reluctant to impose treatment on a competent patient without consent (Appelbaum & Rumpf, 1998; Beumont & Vandereycken, 1998; Rathner, 1998). Furthermore, many argue that the legal framework that enables patients with capacity to be treated without consent is paternalistic and discriminates against patients with mental disorder (Rathner, 1998; Russell, 1995).

The Dilemmas in Treatment without Consent in Anorexia Nervosa

The use of treatment without consent, and the management of treatment refusal, is particularly contentious in the context of anorexia nervosa (Beumont & Vandereycken, 1998; Dresser, 1984; Hebert & Weingarten, 1991; Tiller et al., 1993). The reasons for this can be broadly divided into arguments of efficacy and ethics. One common argument that relates to efficacy is that it is harder, if not impossible, to engage patients in psychological therapies if their treatment is compulsory (Dresser, 1984; Rathner, 1998). A second argument involving efficacy is that re-feeding unwilling patients may lead to short term weight gain but is ineffective in the long run (Rathner, 1998).

There is a paucity of research into the efficacy of compulsory treatment, and no controlled trials. Outcome studies, however, suggest that the long-term prognosis following compulsory treatment is poor (Ramsay et al., 1999). But even if the efficacy of compulsory treatment is demonstrated, there remains the ethical issue as to whether or in what circumstances it is justifiable to impose compulsory treatment for patients with anorexia nervosa.

The treatment of anorexia nervosa often involves implementing a re-feeding programme that may require the use of strict supervision, enforcement of prescribed dietary plans, prevention of exercising or purging, and naso-gastric or gastrostomy tube feeding. All these measures restrict freedom and can be experienced as intrusive and coercive by the patients, their families, and the clinical staff. Those involved can, for these reasons, feel concern about imposing treatment irrespective of whether they believe them to be effective (Beumont & Vandereycken, 1998).

It is our view that the issue of competence is a crucial factor in determining when it is justified to enforce treatment on patients in general. Determining whether a patient with anorexia nervosa has capacity, however, is by no means straightforward, for theoretical as well as practical reasons. We undertook this empirical study in the belief that data about what people with anorexia nervosa think about the disorder and its consequences, and how they reason about treatment options, will help to clarify the nature of capacity and the theoretical issues relevant to the disorder.

An Empirical Study of Competence to Refuse Treatment in Anorexia Nervosa

Researchers are beginning to examine the question of whether the use of compulsory treatment in anorexia nervosa is effective (Ramsay et al., 1999). There are many empirical studies exploring the beliefs, motivations and emotions of patients with anorexia nervosa (Bourke et al., 1992; Habermas, 1996; Horesh et al., 2000; Kennedy et al., 1994; Kennedy et al., 1995), from the point of view of treatment methods. There has, however, been little analysis relating to how these affect capacity, and literature searches of Medline, PsychInfo and Psychlit have revealed no empirical studies on competence or capacity to consent to treatment in anorexia nervosa.

There have been some empirical studies of capacity and competence in psychiatric patients, but these have not included patients with anorexia nervosa (Billick et al., 1998; Grisso & Appelbaum, 1995; Grisso et al., 1997; Grisso et al., 1995; Moser et al., 2002). These studies have used predetermined definitions of competence, adhering closely to the concept of competence based on elements of Understanding, Appreciation, Reasoning, and Expressing Choice (Appelbaum, 1998; Grisso & Appelbaum, 1998b). There are no studies reported, to our knowledge, in which patients have been asked how they have made treatment decisions, or in which the elements that may be relevant to competence have been explored.

In this article, we will describe an empirical medical ethics study in which we used both the MacCAT-T standardised test of competence and qualitative in-depth interviewing to study the factors relevant to competence in young women suffering from anorexia nervosa, as well as obtaining views of their mothers. There were many themes which emerged which were relevant to competence. In this paper, we will specifically focus in the areas of thinking processes and values, and discuss the outcome of the MacCAT-T as compared to the accounts of the young women and their mothers in these areas.

Aims of the Study

This study was conducted to explore the elements relevant to competence to consent to, or refuse, treatment in anorexia nervosa.

Sample

Ten female patients aged 13 to 21 years were interviewed for this study. This age range was chosen to collect data across the age milestones of rights to consent and legal majority in English law, which occur at 16 years and 18 years respectively 2. Participants were recruited through their mental health treatment teams. The selection criteria required that participants had met DSM-IV criteria for anorexia nervosa, including the diagnosis of atypical anorexia nervosa if below 16 years (American Psychiatric Association, 2000). Most of the participants were in treatment and were at a range of stages of illness severity and recovery when interviewed. The participants’ body mass indices (BMI) ranged from 12.57 (a dangerously severe weight deficit) to 19.62 (just below normal limits), with a median BMI of 17.10. Normal body mass index is defined as 20 to 25.

The mothers of seven of the participants with anorexia nervosa were interviewed separately. The parents of an adolescent patient with anorexia nervosa, who was not a participant, were also interviewed. This is because this young woman declined to be interviewed herself, but gave consent for her parents to be included in the study.

Methods

All the participants were interviewed using a semi-structured interview. Interview schedules for patient and parent interviews were devised to explore issues relevant to decision-making and competence, with room for further exploration depending on the themes raised by individual participants. The patient and parent interview schedules are given in the Appendix.

A qualitative methodology using grounded theory (Glaser & Strauss, 1967), modified to accommodate the use of an ethical analysis of the transcripts, was used to analyse the interviews. The interviews were independently coded for content by J.T. and A.S. Coding was pooled and analysis trees were constructed. Quotations were chosen to illustrate themes arising from the analysis.

All the young women were tested using the MacCAT-T test of competence (Grisso & Appelbaum, 1998a). This is a formalised, structured interviewer-administered test of competence that has been validated in some types of psychiatric disorder. The MacCAT-T test is a widely accepted clinical tool for determining competence and closely reflects the common law criteria for capacity (Appelbaum, 1998), with the addition of a dimension of appreciation of the illness. This is considered the current gold standard for formal assessment of competence in clinical psychiatry (Breden & Vollmann, 2004).

The young women also completed five brief self-administered questionnaires to assess their levels of psychopathology: the Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI) (Beck & Steer, 1993a), Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) (Beck & Steer, 1993b), the Eating Disorder Examination (EDE-Q4) (Fairburn & Beglin, 1994; Fairburn & Cooper, 1993), the Eating Attitudes Test (EAT) (Garner & Garfinkel, 1979; Garner et al., 1982), and the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Questionnaire (Rosenberg, 1965).

Results from Quantitative Data

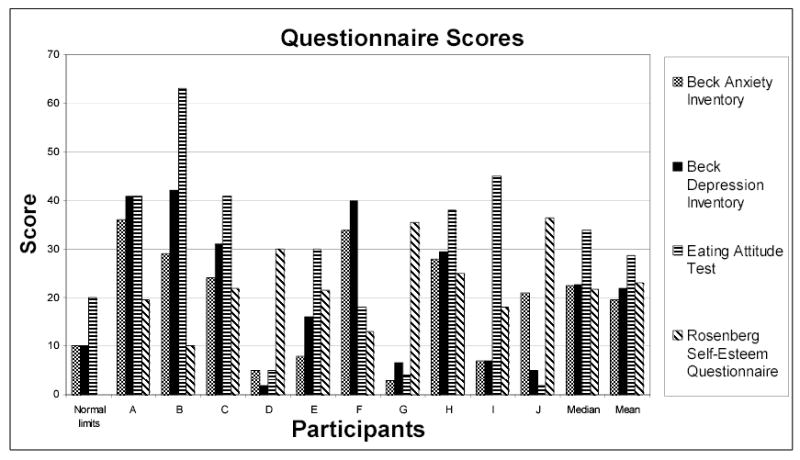

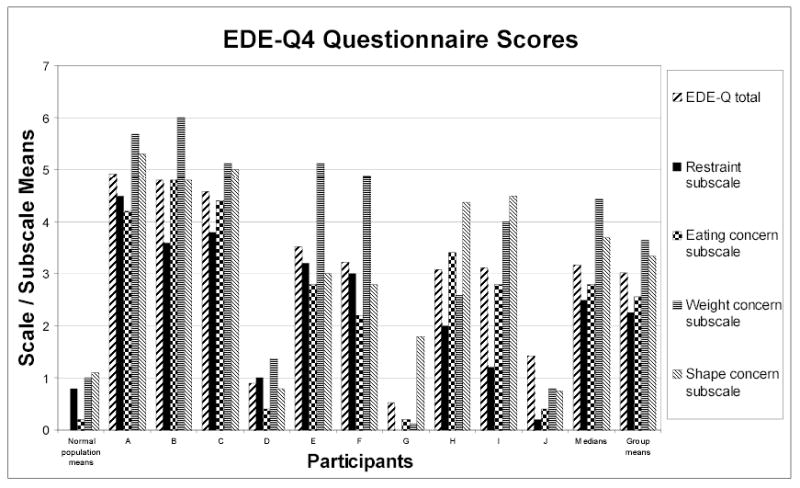

The median scores for the participants as a group were within the clinical range for the Beck Depression and Anxiety Inventories, and within the eating disordered range for the Eating Disorder Examination and Eating Attitudes Test. There was a wide range of scores on the self-esteem questionnaire. The detailed results are shown in Figures 1 and 2.

Figure 1.

Self-administered psychopathology questionnaire scores

Note: The Rosenberg Self-Esteem Questionnaire has no normal limits, the higher the score the higher the self esteem to a maximum of 40 points

Figure 2.

EDE-Q4 scores of patient participants

Note: The EDE-Q4 is a questionnaire which measures eating disorder pathology in four different dimensions, each scored in the respective subscales

The participants with anorexia nervosa scored well on the MacCAT-T test of competence, exhibiting excellent understanding, reasoning and ability to express choice, with generally high scores in each category. Their scores are shown in Table 1. The scores of this participant group were comparable with the normal control groups used by Grisso and Appelbaum in their studies (Grisso & Appelbaum, 1995; Grisso & Appelbaum, 1998a; Grisso et al., 1995). However, two participants did not show full appreciation that they had the disorder. One of these participants agreed with the facts of her condition, but felt ambivalent about whether she had a disorder. The other was more fixed in her rejection of her diagnosis, with firm beliefs that she was too fat, despite the knowledge of her low weight. In accordance with the MacCAT-T, where values are not considered, only the second participant was judged to have questionable global competence, and she was the only person in the group not to unequivocally pass the MacCAT-T.

Table 1.

The MacCAT-T scores of the patient participants

| Participant | Max mark | A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | I | J | Medians | Mean | Standard deviation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Understanding | 6 | 4 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 5.8 | 0.632455 |

| Appreciation | 4 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 3.8 | 0.421637 |

| Reasoning | 8 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 8 | 6 | 8 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6.4 | 1.349897 |

| Expressing choice | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 |

Note: The MacCAT-T instrument of competence requires the use of a structured format in which the health professional gives the patient information about both the disorder and the treatment options being offered, and comprehension is checked immediately by asking the patient to repeat the information in his or her own words. The patient is then probed using set questions to assess the level of appreciation of the information, reasoning with respect to each of the different treatment options, the benefits and risks of each option, and the ability to compare the treatment options and reason about consequences of choosing each option. To conclude, the patient’s ability to express a final choice and provide a reason for this is assessed. There is no pass mark but the tool is used to assist the more subjective clinical judgement of the tester.

There was no relationship apparent between the participants’ scores on the psychopathological scales, their MacCAT-T scores, their body mass indices and the difficulties expressed during interviews, although the small size of this study precludes statistical analysis.

Results from Qualitative Data

The analysis of the interviews of the patient group and their parents revealed a complex interrelation between several different factors relevant to issues of voluntary treatment and competence to refuse treatment in anorexia nervosa. The main emergent themes relevant to competence are described elsewhere (Tan et al., 2003a). In this article, two specific areas will be considered in detail: Difficulties in Thinking; and Changes in Values.

I. Difficulties in Thinking

(a) Muddled thinking and difficulties in concentration

Many participants spoke of difficulties with thought processing. Two distinct ways in which this could occur were having difficulties with concentration and muddled thinking processes.

The most clearly and uniformly described relationship between low weight and cognitions, was its effect on concentration (quotations 1, 3 and 4). This, however, was a variable effect, with participants describing being able to concentrate if the issue was sufficiently serious (quotation 1). Concentration was not, however, just the ability to focus for a long time on one topic. It was also, to some extent, felt to be related to the ability to process thoughts and appreciate the situation (quotations 2, 3 and 4). Muddled thinking processes, where it was difficult to think clearly and logically, were also described as occurring when weight loss progressed (quotations 2, 4 and 5).

-

1

“If you really want to know something and you want to concentrate, you can. If something was very serious for me, then I can concentrate on it. But you tend to –can’t concentrate for long, and [get] very tired, and you don’t want relationships, you just want to hide away.” (Participant I)

-

2

“It’s a mental illness that, I don’t know, it can make you deceive yourself as being fat and it makes you think that you have to be thinner, otherwise people don’t like you. So you stop eating and exercise to try to lose weight, and once you’ve lost a lot of weight, your thought processes are all muddled anyway, so you can’t be clear to think what you are doing isn’t useful, so you actually don’t want to have help.” (Participant J)

-

3

Interviewer: Tell me a bit more about those muddled thoughts. “Well, you can’t concentrate for very long. And your brain function doesn’t seem to work very well. And you see yourself as fat when you really aren’t at all. Things like that.” (Participant J)

-

4

“I don’t know, but – once you’re up to healthy weight again, or, you can actually think better and concentrate longer, so you can see the sense of what’s being done to you.” (Participant J)

-

5

“In my daughter’s case, she’s been Sectioned [under compulsory treatment using the Mental Health Act], and it has taken the pressure off me, as well; but her brain is so starved as well as her body that she’s not thinking straight, she’s not being rational, she cannot see that she’s ill, so far as she can see she’s fine.” (Mother B)

However, the picture is not as straightforward as might first appear. Some participants gave accounts of the preservation of clear thinking and a good capacity to reason and be involved in treatment decisions, even when patients were very low in weight and very unwell. In particular, participants spoke of having a clear understanding of the facts of their disorder and the physical risks associated with this.

-

6

“I knew everything that was going on when I was very ill. I was fully with it… [but] they were treating me like I was about ten and I was a vegetable, because there were the doctors phoning up, coming in and out, discussing things, and I was just sat there waiting for hours, doing nothing. I tried to talk to them, to persuade them, to try to get them to understand. But I don’t think you can talk to someone who hasn’t experienced it, they don’t understand.” (Participant I)

-

7

“I don’t think it takes away their mental capacity at all to decide. I think that, probably, their mental capacity to decide is heightened. They think about what they’re doing for so long. They know, that if they don’t take in a certain amount of calories, what will happen. And I will never, ever be convinced that they don’t.” (Mother G)

-

8

“I only know from H, you hear of the stories of people with anorexia, I know from H’s side, that I think, just talking to her, she’s very focused, she knows the damage she’s doing. She actually knows what the illness does to you.” (Mother H)

(b) Ambiguity of belief

There were difficulties around the area of beliefs concerning the severity of the disorder, the physical risks, and the possibility of death.

(i) Factual disbelief

One participant had total disbelief in the dangers of her disorder (quotation 9). For this participant, the disbelief stemmed in her rejection of the fact that she did not believe that she was too thin. Such total disbelief, however, was not displayed by any of the other participants.

-

9

“Your bones can be weak, your heart slows down, you can be infertile, stuff like that.” Interviewer: Has the risk of death been mentioned? “Yeah.” Do you believe these things you’ve been told? “No.” About the risk of death, do you think it could happen? “Not to me.” That’s the opinion of doctors, and I wonder why you don’t think it can happen to you. “Because you have to be really thin to die, and I’m fat, so it won’t happen to me.” (Participant B)

(ii) Difficulty applying belief to self – salient belief

Disbelief came in more than one form, and the situation was more complex for most of the other participants. For the majority of the participants, their experience with respect to belief of the facts of their disorder was more complicated than mere knowledge. There was a problem of ambiguity of belief, with participants finding a discrepancy between their objective knowledge and understanding (which could be called ‘factual belief’) of their situation, as explained to them by their doctors; and their belief in it in the sense as true of themselves and relevant to their situation (which could be called ‘salient belief’) (quotations 10 to 13). This was often because their perception of themselves and their bodies did not match the seriousness of the factual information, making the factual belief hard to apply to themselves. This difficulty in application of factual belief to the self for most participants was therefore not a pure cognitive deficit or delusional belief, but the result of an interplay of perceptions and intellectual understanding.

-

10

Interviewer: What about death and disability? When you were ill, how did you view death and disability? “I didn’t think it applied to me at all.” Interviewer: How come? “I just could not believe that I could die, I know it’s a silly thing to say, but I felt fine. Talking about me, I had my aches but at that time I did feel a bit ill, but I didn’t take heed, it was straight in one ear and out the other.” (Participant D)

-

11

Interviewer: Why do you think you don’t believe these things could happen to you? “Because although logic tells me I’m underweight, but I don’t feel it. When I’m just going around doing whatever in the day, then I don’t feel that I’ve got a problem. But I know I am underweight because I stand on the scales.” So it sounds like logic tells you you’re underweight. But the way you feel is that you’re normal weight? “Yeah, I just feel that I’m – I don’t feel ill, if you know what I mean. I just feel – I guess I’ve got used to the feeling. But my hands are often cold and so - but I’m used to it so to me it’s normal.” (Participant H)

-

12

“There’s part of me that didn’t believe it [risk of death], but then I did feel very ill. …Because I didn’t get to an incredibly, incredibly low weight, I wasn’t in hospital, so in which case, I thought, “ok, maybe half a stone down the line that would be very, very true but at the moment I don’t think it’s going to happen”. But also at that point it was a very focused and not very happy life so to be honest I also didn’t care.” (Participant C) (Note: 1 stone = 14 lb = 6.4 kg).

-

13

“She says, when she looks in the mirror, she knows she’s desperately thin. But she doesn’t see herself as ill, although she knows the subjects she’s studying, she knows the damage she’s doing. But she said when she looks at the photographs, then she knows how ill she looks.” (Mother F)

(c) External influences on thinking

As seen in the discussion above, low weight was seen as contributing to difficulties with concentration and reasoning. Other factors were also seen as having an impact on decision-making.

Some participants reported that their thought processes were directly affected by their circumstances, in particular the issue of whether they were able to participate in decisions about what was happening to them. Some participants found that being given freedom of choice was essential to allow them to disengage from fighting the professionals and reason out their treatment choices (quotation 14 and 15); whilst others found that being faced with stark facts about the severity of the illness, or being confronted with the need for compulsory treatment, helped them to being able to decide to get better (quotation 16 and 17). This relationship between control and choice is therefore a complex one (Tan et al., 2003b).

-

14

“When I was in a place where, like when I was on a [Mental Health Act] Section and they were getting me to their target weight, everything was theirs, then figures became really important and I hated it, it was everything. But as soon as I was in a place where I was in control and choice and everything then I just wanted was to be healthy and the figures weren’t so relevant, it was how I felt and stuff. I really think that if I’d stayed in a place that was really rigid, I’d have lost it all again and I would not have the attitude I do now. I’m certain of that. But coming to a place where it’s all my choice and in my control then I could really work out what I wanted and it works so much better for me that way.” (Participant D)

-

15

Interviewer: What do you think about being admitted to hospital for treatment against your will? “If I didn’t want to, if I was really, really in my ‘losing weight’ frame of mind, it’s the last thing I would want to be doing; and I don’t think it would be very successful, because I’d be fighting against it. When I haven’t got anyone forcing me to do anything, then I fight against my own thoughts, what my mind is telling me. Whereas when someone is forcing me to do something, then it makes it a hell of a lot easier to fight against them, and then in the end you’re fighting the wrong enemy.” (Participant C)

-

16

“I know - just before I went into hospital, I used to spend my days wandering around and around the house, and then I wasn’t thinking very straight. That must have been about 37 percent weight deficit, 40, something like that.” Interviewer: So that was pretty low weight. So how long was it before you starting thinking right again? “Then I went into hospital, and then I was told if I got any worse I could kill myself in fact. And then that kind of shocked me into thinking I had to get out of this quick.” Right. So even when you were very low in weight, when you got shocked, you did manage to think. “Well, I wasn’t clear about it, I just knew I had to do something. I was willing to give anything a go at it to get there.” (Participant J)

-

17

“I think you're just so confused in your head that you need people to make the right decisions for you. I needed my mum to make most of my decisions for me, even really simple things; I still find that a bit now, it's not as bad. I think by being admitted to hospital or something it does actually make you realise there's a problem; I think in a way if that had happened to me it might make me more accepting that it's actually something wrong with me because quite often I think, oh, it's not that much of a problem, they're just making a big fuss about all this.” (Participant A)

This highlights the need in assessing capacity and competence not only to look at the competence of the person in question, but also take into account the impact of the external circumstances, relationships and context in which the choice is being made. The accounts of the participants suggest that their ability to make decisions, as well as the choices that they make, can be affected by the actions of the professionals treating them, in particular with regard to restriction or freedom of choice. On one hand, for some participants, having freedom of choice was necessary for them to stop fighting against others and to make decisions about fighting the disorder. On the other hand, for others it was necessary to have threats or compulsion in order to realise the seriousness of the situation and to be able to decide to choose to have treatment. This has implications for the way mental health professionals approach engagement with, and delivery of treatment to, these patients, because it is important to support and facilitate competence and competent treatment decisions, rather than impede them. This issue has been explored in greater detail elsewhere (Tan et al., 2003b).

II. Changes in Values

A striking theme that emerged was of values changing when patients developed anorexia nervosa, in ways that are relevant to the issue of competence to consent to, or refuse, treatment. There were several ways in which this appeared to occur.

(a) Values attached to fatness

All the participants described (currently) having, or having had, general value systems in which being fat (or, in some cases, unfit) was perceived as being highly undesirable and having implications for self-worth. There was often a discrepancy in these value systems between the acceptability of fatness for the participants themselves, and for others (quotation 18). Several participants pointed out that people could be large framed or very muscular, and therefore legitimately over the normal weight range. In contrast, ‘fatness’ was generally seen as indicative of laziness, lack of self-care or lack of self-control, and therefore contemptible and disgusting, and likely to lead to unpopularity with peers. Though more extreme, this is a view related to prevailing societal attitudes towards obese people.

‘Fatness’, therefore, attracted value labels in a way that being over the normal weight limits did not, in a way consistent with societal norms. ‘Fatness’ itself also had further personal and private implications that were less congruent with societal values and their own views of other people who might be fat. Some participants viewed themselves being fat as failure, being unlovable, or being an indictment of their entire personalities. The strength and seriousness of the values attached to fatness made fatness in those suffering from anorexia nervosa a state to be avoided at all costs.

-

18

Interviewer: What would it mean to you if you were fat? What would it say about you? “It would just make me feel like people would just think I was greedy, that I was lazy.” (Participant A)

-

19

Interviewer: What would it mean to you if you were fat? What would it say about you? “That I don’t bother to try to change that and it’s disgusting.” (Participant B)

-

20

Interviewer: Do you think it’s ok for them to look tubby or be tubby? “I think it’s ok, I wouldn’t chastise them for it; it makes me incredulous at how people can get like that, I can’t understand how you could kind of get to that point. But if someone is happy with how they look then they should be allowed to look that way.” Interviewer: So it sounds like for you the rules are different, that it isn’t ok for you to be fat. I wonder what it means to you to be fat. “To me in my scale of beliefs, if I was fat then I would be unattractive and a complete failure, and completely not in control of what I do and what I ate, and kind of a horrible person!” (Participant C)

(b) Depressive values

A theme reflected in quotation 12 previously and also in quotation 21 below, was that participants had not felt they cared about the risk of dying, when life was generally very difficult and painful due to the disorder. Their low mood led them to devalue themselves and also life in general. This is explained by the common finding of depressed mood and low self-esteem amongst patients who have anorexia nervosa (Kennedy et al., 1994). These participants did not, however, view losing weight as a method of suicide, and there was little expression of an active wish to die. Suicidal ideas rooted in depressive feelings, therefore, were not generally the driving force of treatment refusal in these participants. However, the value attached to life was less than it might have otherwise been, and this made the risk of death from the disorder less of a motivator for these people to get well than might be hoped by mental health professionals warning them of the risks.

-

21

Interviewer: Were you afraid of dying or not afraid of dying? Was it a risk you were willing to take? “It wasn’t really a risk I was willing to take, it was more that I just felt so awful about everything that sometimes I thought that it wouldn’t matter if I did die, people wouldn’t notice that I wasn’t around.” (Participant A)

(c) The paramount importance of being thin

There were more general and non-depressive ways in which participants described their value systems altering as a result of anorexia nervosa. A major shift in values was that the importance of losing weight increased to the extent of taking precedence over all or many other aspects of their lives, including health, family, friendships and academic achievement (quotations 22 to 24).

From the point of view of treatment refusal, this shift in values due to the central importance of being thin, affected the way participants viewed the risk of death and disability, with a significant loss of the motivation to avoid these outcomes which would normally be expected to be a major consideration when patients are deciding whether to accept a treatment being offered to them (quotations 26 to 29).

The issue of the importance of being thin, however, could be quite complex. Some participants spoke of an ambiguity of values similar to the ambiguity of belief dealt with earlier. They did not necessarily wish to value thinness as highly as they found themselves doing, and felt that other things in life should be more important than they were. Some of them had knowledge that body shape and the pursuit of thinness was not important in general, and also that it was not important in others, but that in spite of this knowledge, it remained disproportionately valued with respect to themselves (quotation 24).

-

22

It’s awful to admit, but in general it’s the most important thing in my life. In comparison with relationships, it’s much more important than that, with university and work it’s a difficult decision, but as it goes I can’t say anything but that I did drop my university and that I was in pursuit of thinness at the time. And even now if I were given the opportunity to go back now [to university] but I’d have to be a lot heavier, I’d say no.” (Participant C)

-

23

Interviewer: What is the importance of your weight and body size to you? “I just want to be thin.” How important is that to you? “Very.” Why? “It just is, it’s all I want.” (Participant B)

-

24

Interviewer: What is the importance of your weight and body size to you? “I don’t know, really, I think. I suppose if I were answering the question for anyone else I would probably say it was of no importance, because all my friends are of different sizes and it doesn’t make any difference, but just for me it’s different, I feel like I suppose because I got so caught up in it that it is really important, but I don’t know why, but it is; I feel really guilty of myself, putting weight on it puts on it makes me feel really different.” So let me see, is it like there’s a split, there’s an intellectual part that knows that it’s not important, that the world doesn’t revolve around your weight, but there’s a feeling side that feels that it’s massively important. “Yeah, definitely.” Do you think that’s changed during treatment, this feeling of weight being as important? “I don’t know, I suppose at the start it was really quite important, and now it seems to be of the same importance, really, because I feel that it does become harder as I putting more weight on, it makes me feel worse; I didn’t think it would be like that, but it is.” (Participant A)

-

25

Interviewer: Why do you think your daughter doesn’t eat normally? “She’s just.. her fear of gaining weight overcomes everything.” (Mother B)

-

26

Interviewer: What do you think she would be willing to do in order to lose weight? How far would she go, what would she do? “Well, if she wasn’t here, if she was still at home, to be quite honest she’d be dead by now, she just so wants to be thin.” Interviewer: So do you think she would be willing to practically kill herself, well, literally kill herself for it? “She doesn’t see death as a possibility. She’s not going to die, she says that, “I won’t die”. She would starve herself to death in order to be thin.” Interviewer: That wouldn’t frighten her. “No!” (Mother B)

-

27

“I wasn’t really bothered about dying, as long as I died thin.” (Participant I)

-

28

“She says that it doesn’t bother her at all if she dies, and she’d rather be dead than put on weight.” (Mother B)

-

29

Interviewer: It sounds like the value they place on life and health is different. “They don’t place any value on life, I don’t think. I think life is what they are at that moment, that their whole life revolves around um, trying to get out of the next meal. ... So their whole life revolves around not eating.” (Mother G)

(d) The functions of anorexia nervosa

Although all the participants spoke of misery and difficulties associated with having an eating disorder, nevertheless there were positive functions that anorexia nervosa played for many participants, which were highly valued. Different positive functions expressed were that it would make them happy (quotation 30), help them feel safe and in control especially in difficult times (quotation 31 and 32), help them be more popular, different from the rest or noticed (quotation 33), and avoid growing up (quotation 34).

-

30

Interviewer: What is the importance of your weight and body size to you? “I just want to be thin, and happy.” Right, how strong is this thing about wanting to be thin? “It’s still very strong. ... I still want to be thin.” You really want to be thin. “Yeah.” Is that connected to being happy, because you mentioned both at the same time? “Yeah, I think, although it wasn’t that true before, I do think that being thinner for me will make me happy.” (Participant I)

-

31

“It takes control of you, but it can also feel very safe. It’s a very confusing illness, because at the moment it’s probably got a lot of control over me, in certain ways, and I just want to get away from it, I’m just sick and tired and I’m exhausted, but then it kinds of protects you as well, I think, from coping with other things… It distracts you so completely about things you don’t want to think about, to lose that is quite scary.” (Participant F)

-

32

“..As far as I can see with B, she’s got control over it, it’s the only thing she can control is her body, because we’ve had a lot of very difficult times. I think that’s the way she’s using it.” (Mother B)

-

33

Interviewer: What does your daughter’s anorexia nervosa mean to her? “I think it means she’s different.” Right. And is that good or bad as far as she’s concerned? “Good. She’s different. She’s the only girl in her school who’s anorexic. She’s the only girl at school who’s not allowed to go out at playtime. She comes home for lunch, no one else is allowed to. It makes her that little bit different. And also, I think it makes her special.” Right. Although they’re not very nice things she’s different for. “No. But it just makes her that little bit different.” (Mother G)

-

34

“And I also think that sometimes they’re frightened of growing up. Their body changes and they don’t like it. I think that’s what it is.” (Mother F)

The many and varied functions of anorexia nervosa made the disorder itself valued by the participants, in spite of their difficulties. It made it difficult to contemplate accepting treatment, as it would mean losses as well as gains. In some cases, these losses were felt to be too great to bear. Therefore, in a weighing up of risks and benefits of accepting treatment for anorexia nervosa, there was a possibility that the participants would arrive at conclusions that might not match the opinions of their families or the professionals treating them, who may not appreciate these functions or their importance and value.

(e) Other values associated with anorexia nervosa

There were some other unusual values attached to having anorexia nervosa. Quotation 35 below illustrates an unusual attitude that running the risks of death and disability were seen as meritorious, which gave these risks a special significance or meaning, and therefore altered the way in which this participant would have viewed warnings of her physical condition. Instead of motivating her to accept treatment to gain weight, it is likely that with this value attached to taking risks in the course of her disorder would have caused her to discount the need for treatment even more. In a similar fashion, another participant described her anorexia nervosa as her talent, in that she was capable of losing weight in a rapid and extreme fashion that was beyond the willpower of the ordinary person. It is evident that these unusual attitudes to death and disability are relevant to how these participants would make treatment decisions, as it would alter the utilities assigned to the risk of death and disability, when these decisions are being made.

-

35

“I remember getting some tests back saying how my liver was really damaged and all this, and I thought it was really rather good! I can’t imagine that I thought it, it felt like really quite an accomplishment!.. It’s sick, isn’t it? It was like somehow I’d achieved! And knowing I almost killed myself; no, I’d say the illness almost killed me, it was like, wow. It was just I’d just done something that I knew hardly anyone else could do. ...I can remember when I had difficulty walking upstairs, or I had such pain bending down, at the back of my legs, and I loved it, I used to bend down as much as I could to feel the pain! And I felt so in control.” Interviewer: I wonder if it was also like risk-taking; like some people, say a sportsman who jumps out of a plane with a parachute, get a real buzz. “You do, you get a real buzz. And I can’t imagine getting that buzz now, but you do, you get a real buzz from it. And I don’t know where it comes from.” Interviewer: Well, sane, so-called normal people do that, they go out and bungee jump. So you think there is an element of the thrill of risking death. “And you do feel like you might not have achieved anything else, but hey, I’ve done this, I’m cool!” (Participant D)

(f) The issue of personal identity

The issue of the effect of anorexia nervosa on personal identity has been explored in depth in a separate article (Tan et al., 2003c). However, as the issue of personal identity is relevant to a person’s set of values, a brief account is included here.

For some participants, anorexia nervosa was experienced as part of their personal identity (quotations 36, 37 and 39), and was seen by some mothers as changing their daughters’ personalities (quotation 38). For this young group of participants, there was often a lack of knowledge of what they would be like if they did not have anorexia nervosa, often because their last experience as a well person was as considerably younger adolescent (quotation 36).

The values typical of anorexia nervosa were relevant to the issue of personal style and personal identity, as the identity of anorexia nervosa was often characterised by a rigid, controlled, high achieving and perfectionistic style (quotations 38 and 39). The issue of personal identity, therefore, also related to the set of values about life in general that the participants held, and not only those about weight and shape or low self esteem.

These factors worked together to make the sense of an identity without the anorexia nervosa hard to imagine or contemplate (quotation 37), which was then a barrier against accepting treatment, which might eradicate the disorder and thereby ‘kill’ the person they felt they were, replacing it with a different person.

-

36

“It’s important to me, because I was fourteen or something when I got it, it was like I didn’t really know myself at that time, I think that was one of the reasons I got it, so it was very big part of me, between fourteen and sixteen.” (Participant I)

-

37

Interviewer: If your anorexia nervosa magically disappeared, what would be different from right now? “Everything. My personality would be different.” Really! “It’s been, I know it’s been such a big part of me, and - I don’t think you can ever get rid of it, or the feelings, you always have a bit - in you. But, it’s like, I can understand other people and their eating problems, and being in a psychiatric unit you sort of learn to understand other disorders like depression and schizophrenia, and so I’ve learned a lot. And I would have [been] more selfish, and that, more gossipy, because that’s what I used to be like.” Let’s say you’ve got to this point, and someone said they could wave a magic wand and there wouldn’t be anorexia any more. “I couldn’t.” You couldn’t. “It’s just a part of me now.” Right. So it feels like you’d be losing a part of you. “Because it was my identity.” (Participant I)

-

38

“I would like to say, while talking about that, that K’s lost her childhood. I feel that really strongly, that now, we don’t have a happy 13 year old, we have, what almost not a child, somebody that’s full of depression and negativity and – just seems to have the world on her shoulders, and I find that really quite scary. I go in to help at the school, and you see the happy children, and they’re carefree, and now K isn’t care free, nothing she does is care free. It’s very careful, and thought about, and controlled.” (Mother K)

-

39

Interviewer: Who is your anorexia nervosa? Or what would it be? “I suppose it would be a person who was really determined, and I suppose really discontented with life.” No one you recognise? “No.” What does your anorexia nervosa mean to you? “As I said before, it’s quite a lot. It feels like my identity now, and it feels like, I suppose I worry that people don’t know, they don’t know the real me.” (Participant A)

Limitations of the Study

This is a small study and therefore no claims can be made about the representativeness of its results with respect to patients with anorexia nervosa in general. However, even in this small sample it has been shown that there is a range of difficulties that such patients can experience, which are relevant to competence to refuse treatment in anorexia nervosa.

Due to the size of this study, there has been no attempt to include males in this study, although they do account for up to ten percent of clinical cases (Royal College of Psychiatrists, 1992). It was also not considered feasible in a small study to selectively recruit patients from ethnic minorities, and as a result the study sample, although not by design, consisted entirely of English speaking, British families of white European ethnic origin.

The nature of the difficulties expressed by the participants of this study will need further investigation, particularly views in hindsight to clarify how participants view their own competence to make treatment decisions, and its relationship to the disorder. A longitudinal study of 6 of the 10 patient participants of this study is currently underway to investigate the changes that occur in attitudes and values over time, as the anorexia nervosa resolves or continues. A larger scale qualitative interview study of patients and their parents is also currently underway.

Discussion

We have presented findings about the impact of anorexia nervosa on various aspects of patients’ thinking processes. These include difficulties with concentration, muddled thinking, ambiguity of belief, and external influences. The data also provide evidence about the impact of anorexia also nervosa on their sense of personal identity and on various types of value systems relevant to decision-making about treatment. Anorexia nervosa can affect thinking in ways that have impact on decision-making about treatment and on competence. Some of these ways suggest that the current legal approach to competence and its assessment may be inadequate.

All the young women participating in this study, some of whom were at very low weights and on Mental Health Act compulsory treatment orders, were able to describe their own difficulties with great insight and clarity. It is apparent that the difficulties with competence associated with anorexia nervosa, while clearly present, do not preclude the affected young women themselves from being able to perceive and discuss many of their difficulties with decision-making.

The legal concept of capacity (competence)

In the United Kingdom, the United States of America and many other legislations, the key concept in answering the question of whether a patient can make valid treatment decisions (and refuse treatment on offer) is that of legal capacity (or in the US, competence). This is largely conceptualised as an intellectual capacity. English case law identifies the components of capacity as: understanding (the key facts relevant to the treatment decision); retention of these facts in order to use them in coming to a decision; the ability to believe the facts (for example, absence of a delusional disorder that interferes with such belief); and the ability to weigh up the facts and come to a decision 3. In statute law, the new Mental Capacity Act received Royal Assent on 7th April 2005 and will be coming into force in the near future in England and Wales. This will provide the first statutory explication of capacity in English law 4. This is based on the common law concept although it adds, as a necessary component, the ability to communicate the decision, and leaves out the issue of ability to believe the relevant information. Capacity plays the key role within English common law (although not within the Mental Health Act) in answering the question of whether beneficial treatment can be imposed on a patient who is refusing it. An adult patient who has the capacity to refuse treatment has the right to refuse it whatever the consequences. A patient who lacks capacity, on the other hand, may have treatment imposed if this is in her best interests.

One important aspect of both English and US law is that a decision, however foolish it appears to others, is not by itself evidence of lack of capacity 5. In order for a person to be judged to lack capacity he must fail in at least one of the components outlined above, and all these components relate not to the final decision itself but to the way in which the decision was reached. In other words, in order to judge that a patient lacks the capacity to make a particular decision (such as refusing beneficial treatment) it is necessary to know something about how he made the decision – what his reasoning process was. It is therefore strange, at least at first sight, that in one important case (Re T 4) the judge said that patients are entitled to refuse treatment even if the decision is neither sensible, rational, nor well-considered, and even if it is made for unknown reasons or for no reason at all. Without knowing the reasons why the patient is refusing beneficial treatment how can doctors judge whether or not the patient has the capacity to refuse? Freedman has argued that the autonomous person is entitled to be foolish in his decisions (Freedman, 1981). The judge in the case of Re T is upholding respect for the autonomy of a competent person by allowing him not only to make his own decisions but also to keep any reasoning to himself. Such a position is tenable as long as there is no doubt about the competence of the patient. But as soon as there is any doubt as to whether the patient who is refusing beneficial treatment is competent to do so then an assessment of competence is needed and this will require an assessment of the reasons why the patient is refusing. Questioning the competence of a person to refuse treatment, therefore, has the consequence that the person may need to be explicit about his reasoning in order for his competence to be assessed. Questioning a person’s competence has a second possible consequence: that the person will be found to fail the test of competence. It is likely that some of those for whom the question of competence is not raised would fail the competence test were they subjected to it. In English law a minor under the age of 16 years is presumed not competent to consent to, or refuse, treatment unless there is convincing evidence to the contrary. Thus for a minor under 16 years old to be considered to be competent an assessment would need to be carried out. The presumption for those over 16 years is that they are competent. No assessment is required unless there is some cause to doubt the person’s competence. This difference in presumption can result in two people who are, in fact, identical with regard to level of competence being treated differently depending on whether they are under or over 16 years. The person under 16 may be assessed for competence (since the presumption is of incompetence) and fail the test; whereas the person over 16 years may not be assessed (since the presumption is competence) and therefore be regarded as competent (Devereux et al., 1993). Those with mental disorder might also be discriminated against for similar reasons.

The extent of this problem depends to a considerable degree on the threshold used for incompetence. There is a serious danger that our growing understanding of the increasing number of factors involved in competence may drive us into developing ever higher standards of competence. Standards should not, in our opinion, be set at a level that would render ordinary adults incompetent. It is only in special, and rather rare, circumstances that adults should be found incompetent, otherwise the concept would be being used in a way that seriously interferes with individual autonomy and freedom.

If we are to develop methods for assessing competence based principally on data from people with mental disorder then we may lose sight of the levels of rationality that are used by ordinary people. Since we believe that the data reported in this study do provide evidence for broadening the range of factors that can compromise competence, this is a danger of which we particularly need to be aware.

Philosophical conceptions of competence

Grisso and Appelbaum, although basing their analysis on legal precedents, go further than English (or US) law in their analysis of competence through introducing the notion of ‘appreciation’ in the MacCAT-T instrument (Grisso & Appelbaum, 1998b).

The key aspect of appreciation is that the patient not only understands the relevant facts but also ‘appreciates’ that those facts apply to her. Thus a patient who understands that she is suffering from gangrene of the foot, and understands further that without surgical removal of the foot such gangrene will, with a high degree of probability, lead to the patient’s death, might nevertheless fail to appreciate that all these facts apply to her, and that therefore she is likely to die without surgery. This concept of appreciation, like the other aspects of the legal concept of capacity, is essentially an intellectual component. It is close to the criterion used in ReC of the ‘ability to believe’ the relevant facts. Grisso and Appelbaum, however, in their further analysis of the concept of appreciation include aspects that go beyond the facts and understanding relevant to the specific decision and include the wider belief systems of the patient. Grisso and Applebaum provide three criteria in judging whether a patient fails the appreciation test, and therefore lacks capacity. First, the patient’s belief must be substantially irrational, unrealistic or a considerable distortion of reality. Second, the belief must be the consequence of impaired cognition or affect. Third, the belief must be relevant to the treatment decision (Grisso & Appelbaum, 1998c).

Consider a person with moderately severe depression who refuses help because of a belief that she is useless and not worth helping. Such a person might pass the Re C test of competence. She might understand the key facts; believe them; and weigh them to come to a decision. Her decision to refuse treatment is based not on any factual error or intellectual failing but on the low value that she puts on herself. It might be argued that she is unable to properly weigh up the relevant facts because of this low self worth which is itself a result of the depression. But we believe that this is somewhat of a distortion of the Re C criteria: the depression does not result in an inability to weigh up the issues and come to a decision. It is rather that the depression affects the values which are being used in weighing up.

Grisso and Appelbaum’s appreciation criterion provides a way of finding this patient incompetent. It could plausibly be argued that she has a belief (that she is worthless) that is a considerable distortion of reality, it is caused by impaired affect (her depression), and this belief results in her decision (to refuse treatment). There is a problem even with this analysis: it is not clear that the belief that one is worthless is a ‘distortion of reality’. Such a belief is essentially a value, not a false view of reality.

Buchanan and Brock use a notion of competence that is broader than that of Grisso and Applebaum. They suggest that, in addition to abilities to understand, communicate, reason, and deliberate, a competent decision-maker also requires a set of values or conceptions of the good which is at least minimally consistent, stable, and affirmed as her own (Buchanan & Brock, 1989). This analysis introduces two important concepts additional to the legal analyses: values, and stability of views.

Charland goes further. He highlights the importance of values in decision making and embraces the possibility that a person lacks competence because his values are unreasonable, even if his decisions are intellectually coherent with his values (Charland, 2001). Charland’s approach derives from his interest in the role of values in rationality. He believes that in understanding whether a person is competent or not we may need to know a great deal about how they come to make their decision including the ‘internal rationality’ of the decisions.

‘Internal rationality’ is achieved when a putative decision (a) coheres with an individual’s enduring aims and values; (b) is justified in the light of these values; and (c) the proposed justification is deemed appropriate by the third party responsible for assessing competence. By asking the question ‘Why?’ with regard to the decision patients are making or would make, Charland suggests that we can uncover the value systems that are underpinning or driving the reasoning that leads to these decisions, and thereby be able to evaluate these value systems for their coherence, justification, and reasonableness, and the way they drive the reasoning leading to the decision. This approach is based on what Freedman calls ‘recognisable reasons’ which are acceptable reasons constituting premises that are strong enough to lead to a conclusion; and that conclusions in turn follow from the premises in a way that satisfactorily explains the treatment decision (Freedman, 1981).

Benaroyo and Widdershoven have taken yet another route by addressing these problems using a hermeneutic approach, and stressing the importance of overall context and meaning of decisions to the decision-maker to the assessment of competence (Benaroyo & Widdershoven, 2004). Both Charland’s and Benaroyo and Widdershoven’s approaches lead inescapably to the consideration of values. Breden and Vollman, in their critique of the MacCAT-T, suggest that the MacCAT-T’s lack of reference to values is problematic, because values are inherent in the decision-making process and the consideration of values, which they call ‘the patient’s normative orientation’, is important in the assessment of competence (Breden & Vollmann, 2004).

Thinking processes and the data from this study

The qualitative analysis of the interviews reported here yielded a more complex picture of the areas of difficulties in thinking and changes in values than the MacCAT-T was able to capture. With respect to difficulties in thinking, there are several conceptually distinct ways in which this was described. First, there were difficulties in concentration, which were described as increasing with weight loss. Concentration, however, was still possible even at low weights, with some effort. Second, there was muddled thinking, with difficulties in reasoning logically, which also appeared to increase with weight loss. Both of these problems fall within the traditional view of competence as expressed in the MacCAT-T, which underscores the point that the MacCAT-T does capture important and essential aspects of competence (Breden & Vollmann, 2004).

Difficulties with thinking, however, were not limited to concentration and reasoning. This study found that the patients who talked about difficulties in thinking also performed very well on the MacCAT-T. This is because the MacCAT-T understands reasoning as an essentially cognitive process, reducing it to ‘logical consistency in rational argumentation’ (Breden & Vollmann, 2004). Problems with logical processing as measured using small blocks of factual information by the MacCAT-T were not described by the participants as a major feature of problems in decision-making associated with having anorexia nervosa, although some participants did describe what they called ‘muddled thinking’. ‘Muddled thinking’ as described by the participants appeared to extend beyond this to encompass a greater than usual difficulty in thinking through the meaning or usefulness of actions. This phenomenon of muddled thinking, however, was not described by every participant. Some participants, including mothers who may be viewed as more objective with respect to their daughters’ limitations, expressed the opinion that there was no impairment in the reasoning of anorexia nervosa sufferers, even at low weights.

One finding in this study that is important in considering the question of competence is the ambiguity with which some beliefs were held. The issue of belief or disbelief is not always a straightforward affair. There is a distinction between what might be called ‘factual belief’ and ‘salient belief’. Factual beliefs are those beliefs about objective (medical) facts, for example the effects on health of severe weight loss. Salient beliefs are beliefs about whether the facts apply to oneself. Thus several people in this sample reported believing that severe weight loss is dangerous but not believing that such danger applied to themselves, even though they accepted that they had lost weight. This idea of salient belief is essentially the same as Grisso and Appelbaum’s concept of appreciation that the facts apply to oneself (Grisso & Appelbaum, 1998b). Where such salient false belief is fixed and firmly held it will be picked up by the traditional legal approaches as grounds for considering someone incompetent. A person who was at great danger of serious harm as a result of her low weight but failed to believe this would fail the criterion of believing a key fact or of being able to weigh up the key facts in coming to a decision. But our data suggest that these ‘salient’ beliefs are often held in a more ambiguous way both in the sense that they may be held to be true but only to a degree and in the sense that there is fluctuation in the degree to which they are held to be true. Thus an individual who is seriously underweight may correctly believe that people at her weight are at high risk of serious harm (factual belief) and accept, at least at times, that she may be at risk, but have difficulty in taking such risk seriously when thinking about the need for treatment.

These ambiguities with ‘salient’ belief are rooted in the experience of anorexia nervosa which appears to normalise the experience and perception of extreme weight loss and its accompanying symptoms. This results in giving the dangers of the weight loss relatively little importance in decision-making despite understanding and believing them.

Patients who believe and understand the risks of being severely underweight but nevertheless refuse treatment because they do not take these risks seriously when making their decision could be found incompetent using the usual legal criteria and those incorporated into the MacCAT-T. That is, they might be assessed as incompetent either on the grounds that they do not believe a key fact (that they themselves are a high risk) or that they are not able to weigh up the key facts in coming to a decision. But these grounds find analogies with normal adolescence. One example is that many adolescents are able to accept the dangers involved in speeding, drink and drugs (factual belief) but lack the salient belief that dangerous outcomes could actually occur to them. As a result they choose to engage in risky behaviour as if, but not really because, they believe they are immortal.

This highlights the problem that we mentioned earlier: that criteria for incompetence are in danger of being set at too high a level: i.e. at a level that would, if applied consistently, find too many people incompetent and provide justification for an excessive interference in people’ freedom to make decisions and to act in ways that they choose.

Does Charland and Freedman’s approach provide a way of finding the person with anorexia nervosa incompetent without opening the way to an excessive interference with freedoms? Consider the patients with anorexia nervosa in this study who acknowledged that they were below the population norms in terms of weight and also acknowledged that they may be placing their health at risk, but who explained that they still felt fat, and therefore could not quite believe that they were at risk and needed to have treatment. These participants might quite understandably choose not to have treatment which would make them put on weight. Such patients are likely to pass the first two criteria of Charland’s internal rationality test but fail the third because the mental health professionals and most people in the general public would feel that it is unreasonable to place so high a value on being thin that health and life are placed at risk.

The normal but risk taking teenagers who, while accepting the risks feel somehow privileged and at less danger themselves, might pass this third criterion because this is understood as normal and thus justified. There is however a major problem in relying on this third, external ‘reasonableness’ criterion. It opens the door to considering the beliefs and values held by people from alternative cultures or sub-cultures as unreasonable (for example Jehovah’s Witnesses who refuse life-saving blood transfusions). It also opens the door to assessing as incompetent those whom we think are making inappropriate decisions, for instance already attractive individuals placing themselves at unnecessary physical risk and pain by undergoing cosmetic surgery in order to correct small physical imperfections. Intuitively what justifies the view that those suffering from anorexia nervosa who are making foolish decisions are incompetent, is not simply that they are making foolish decisions but that their foolish decisions arise from a mental disorder.

Values and that data from this study

There are good reasons why the legal approach to competence focuses on intellectual abilities and eschews a consideration of the patient’s values. If a patient’s particular values can be a reason why they are incompetent (hence justifying overriding their refusal of treatment) then this could lead to discrimination against people who hold values that are different from those of health professionals, or society more generally (Breden & Vollmann, 2004; Nys et al., 2004) 6. Respect for individual autonomy and the ‘negative’ freedom to be able to pursue one’s life according to one’s own values without interference from others are important aspects of a liberal society.

We believe, however, that the data from patients with anorexia nervosa provide grounds for believing that the concept of competence must allow for the possibility that a person can be incompetent, and that overriding treatment refusal is justified, even when she passes those tests of competence that avoid an assessment of the patient’s values (Tan, 2003). The participants in this study reported many instances where problematic decisions were based on values related to the anorexia nervosa. These values included: the paramount importance of being thin even to the extent of preferring to risk death rather than put on weight; a positive value to damaging oneself through starvation as a sign of achievement; a value in being different from other people through extreme thinness; and the sense that the anorexia nervosa is part of one’s identity such that a cure would be tantamount to becoming another person.

One response is to ‘bite the bullet’, maintaining an account of competence that avoids values, and allowing people with anorexia nervosa who are competent on such accounts to refuse treatment even when the result is a high risk of significant harm or death. The alternative response is to develop an account of competence that can include patients’ values whilst avoiding the problems of excessive paternalism and undue interference with individual freedom. An attractive way forward, which has intuitive appeal, is to see those values that are both a result of mental disorder, and that underpin the dangerous decisions (such as refusal of beneficial treatment), as pathological. One implication of their being pathological is that these values do not represent the true or authentic views of the person. In respecting the autonomy of the person it is her ‘authentic’ views that should be respected – that is the views that she would have (or did have) if she did not suffer from the mental disorder. The concept of pathological values, linked to mental disorder, enables such values to be distinguished from the unreasonable, unusual or bizarre values that people are fully entitled to hold, and often do hold, in the course of everyday life.

If we understand him correctly, Charland makes use of the concept of ‘pathological value’ without also relying on the idea of inauthentic value (Charland, 2001). Charland suggests that we should ask, during the assessment of competence, not just about understanding of facts, but also look at reasons and values; as he puts it, ask not just the ‘What?’ questions but also the ‘Why?’ questions. This he feels will elicit an account of values which can then make them available for the consideration with respect to competence. But what would this mean in practice when applied to anorexia nervosa? It may prove difficult for Charland’s proposal to produce responses which enable easy assessment. Unlike psychotic disorders which tend to be associated with apparently bizarre, meaningless or disconnected beliefs, there can be consistency, coherence and organisation within the value and belief systems which underpin the behaviour of patients who suffer from anorexia nervosa. The patient who has anorexia nervosa therefore may be able to give a coherent, consistent answer to the ‘Why?’ question, but still be making decisions based on ‘pathological values’ that arise from the disorder. These pathological values may be organised in a way similar to other, non-pathological value systems that the person may hold. Some of the study participants, for example, explained that they understood the risks that they were running, but that the importance of being thin made the risks relatively unimportant and therefore not sufficiently motivating for them to seek treatment. The broader value systems central to anorexia nervosa are similar to those held by a significant proportion of the general public and therefore do not appear at face value to be unusual or unreasonable. For example many people with anorexia nervosa hold value systems which encompass views such as: ‘body shape is very important’, ‘body shape determines my self-worth’, ‘fatness is bad’, ‘thinness or slimness is good’, ‘fat people are lazy and don’t look after themselves’, ‘it is good to exercise and reduce weight’, and ‘the slimmer I am the more that people will like and admire me’, all of which are prevalent in society and encouraged by the popular media. What is striking in anorexia nervosa is the strength of these values, and the central importance attached to them, often to the severe detriment of other value systems and other aspects of life.

If the judgment that these values are pathological is to be made independently of the concept of mental disorder then it will be very difficult to see how they are different in principle from many other examples in ordinary life, for example a dedicated surgeon who neglects his social life, family life and hobbies in the practice of his career; or the athlete whose diet, daily routine and physical activity are all completely dictated by the need to maximise his performance at his sport? It is important that we should not become too oppressive in our assessment of other people’s values, just because they deviate from the norm.

One possible way in which we may be able to draw a distinction between the values seen in anorexia nervosa and these examples from everyday life is to define ‘pathological values’ as values caused by mental disorder. If a value or value system can be determined to arise from a mental disorder then it is ‘pathological’. If it is pathological and these pathological values are determinative of particular decisions then such decisions are not competent. And if such decisions would lead to significant risk of harm then it is legitimate to override them in the interests of the patient.

This determination may not be possible in many cases, but may be feasible in others. The method of tracking changes of values back to anorexia nervosa is particularly well illustrated by values concerning fatness. Fatness was considered by the study participants to have many specific meanings which rendered it a highly undesirable state. This was in turn associated with thinness being viewed as of paramount importance by many participants. These value systems about fatness and thinness are fully consistent with the intrusive fear or dread of fatness, the core and sole psychological criterion of anorexia nervosa, and are highly familiar to professionals who work with patients suffering from anorexia nervosa. It is quite likely then that these specific sort of values are ‘pathological values’ if they are found in a patient who has anorexia nervosa.