Abstract

Non-human primates (NHPs) are considered to be among the most relevant animal models for pre-clinical testing of human therapies, on the basis of their close evolutionary relatedness to humans in terms of organ cell biology and physiology. In this study, we sought to investigate whether NHP models accurately reflect the effectiveness of recombinant adeno-associated virus (rAAV)-mediated gene delivery to the airway in humans. In order to do this, we utilized an identical model system of differentiated airway epithelia from Indian Rhesus monkeys and from humans, cultured at an air–liquid interface (ALI). In addition to assessing the biology of rAAV-mediated transduction for three serotypes, we characterized the bioelectric properties as a reference for biological similarities and differences between the cell cultures from the two species. Our results demonstrate that airway epithelia from NHPs and humans have very similar Na+ and Cl− transport properties. In contrast, rAAV transduction of airway epithelia of NHPs demonstrated significant differences to those in humans with regard to the efficiency of apical and/or basal transduction with three rAAV serotypes (AAV1, AAV2, AAV5). These findings suggest that the Indian Rhesus monkey may not be the best model for preclinical testing of rAAV-mediated gene therapy to the airway in humans.

INTRODUCTION

Non-human primates (NHPs) are genetically and evolutionarily much closer to humans than are other mammalian species. They have therefore been used extensively as pre-clinical models both for understanding organ physiology and for testing therapies. In the context of gene therapies, NHPs have been invaluable models for both pre-clinical testing and for obtaining Food and Drug Administration approval for new gene delivery agents to multiple organs.1,2 The development of gene therapies for cystic fibrosis (CF) lung disease is one example of an area of research that has been heavily dependent on NHP studies for predicting the efficacy and toxicity of gene transfer vectors before they are tested in humans. The high level of conservation between NHPs and humans at the genomic level is also reflected in more closely conserved cell biology.3,4 In the context of the lung, NHPs have a strikingly similar repertoire of cells types that line the airways.5,6 Similarities of this kind have suggested that NHPs are the best models for testing pre-clinical therapies including gene transfer.

CF is a disease caused by defects in the gene encoding the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR), resulting in the abnormal regulation of chloride transport in the lung and other organs.7 Recombinant adeno-associated virus (rAAV) has attracted considerable interest as a vector for treating CF lung disease. Indeed, rAAV-based vectors have been used successfully to functionally correct CFTR in human CF airway epithelia in vitro,8–10 and both pre-clinical studies and clinical trials have evaluated such vectors in CF gene therapy.11–14 To date, a variety of rAAV vector serotypes have been tested as gene transfer vectors.15 However, these have been shown to have species and tissue tropisms in lung, muscle and central nervous system. This makes it difficult to reliably predict the efficacy of these vectors in humans.15–18 rAAV-mediated gene transfer to NHPs has been investigated in a number of tissue types, including muscle,19 brain,20 lung,12 and liver.21,22 Pre-clinical studies in NHP lung using rAAV2-CFTR virus have clearly demonstrated the efficacy of the virus in inducing prolonged transgene expression.12 However, clinical trials with this same vector have failed to detect transgene-derived messenger RNA in human CF lungs, despite the detection of vector-derived DNA.23 This has raised questions about the manner in which clinical rAAV vectors are tested and chosen for human trials. Faced with an increasing number of rAAV serotypes,15 it is unclear which models may provide the best clinical efficacy.

Rhesus monkeys are the most commonly used NHP species in biomedical research. In part, this is because of their ability to reproduce in captivity. Furthermore, the physiology, immunology, genetics, and anatomy of the Rhesus monkey have been well characterized. In order to get a better understanding of whether the Rhesus airway epithelium is capable of accurately predicting rAAV vector biology, we have compared several biological characteristics of air–liquid interface (ALI) epithelial cultures from Indian Rhesus monkeys with those from humans. Using a similar model system for this analysis afforded a more accurate direct comparison of bioelectric properties and susceptibility to rAAV infection with rAAV1, rAAV2, and rAAV5 serotype vectors. Although airway epithelia derived from monkeys and humans behaved in strikingly similar ways from an electrophysiologic standpoint, major differences were observed in the biology and serotype specificity of transduction with these three rAAV serotypes. These findings suggest that when Old World NHPs are used in pre-clinical testing of rAAV gene transfer to the lung, the results of the studies should be interpreted with caution.

RESULTS

In vitro culture and differentiation of airway epithelial cells from Indian Rhesus monkeys

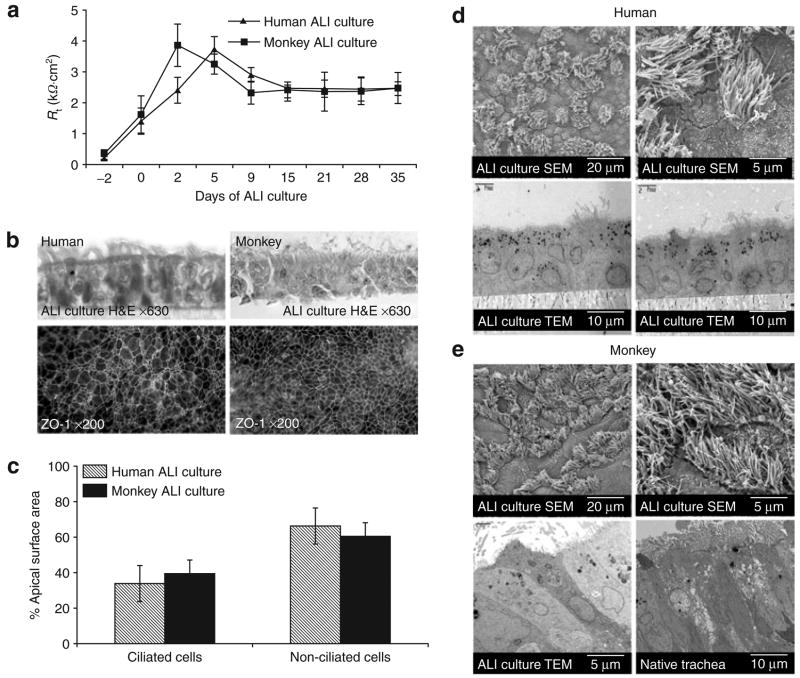

Before comparing rAAV gene transfer between airway epithelia in humans and monkeys, it was important to demonstrate that both species establish well-differentiated and polarized airway epithelia in vitro. The formation of a trans-epithelial resistance (Rt) and tight junctions are indications of polarization. As previously reported for human and murine airway epithelial cultures,16,24 we found that Rt of tracheal-derived epithelia both from humans and from monkeys stabilized within 2 weeks after the establishment of ALI (Figure 1a). ZO-1 immunostaining demonstrated formation of epithelial tight junctions coinciding with increased resistance (Figure 1b). The relative percentages of ciliated and non-ciliated cells in ALI cultures from these two species were also very similar when evaluated by scanning electron microscopy (Figure 1c–e). However, as routinely observed in ALI cultures, the quantity of ciliated cells was less than that seen in the native tracheal epithelium.

Figure 1. In vitro differentiation of airway epithelial cultures from human and from Indian Rhesus monkey.

(a) Transmembrane resistance (Rt) of air–liquid interface (ALI)-cultured tracheal epithelial cells from humans and monkeys was evaluated from the day of seeding to 5 weeks after ALI was established. Values represent the mean ± SEM (n = 6 samples/day) from three different tracheas. (b) Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) stained sections show the formation of an intact pseudostratified epithelium in ALI culture (top panels) of human (left) and monkey (right). En face ZO-1 immunostaining (bottom panels) demonstrates the formation of tight junctions in 2 week-old ALI cultures of human (left) and monkey (right) at the given magnification. (c) Quantification of the relative fractions of ciliated and non-ciliated cells in airway epithelia cultures of humans and monkeys using the relative fractional area of the apical surface covered by cilia (N = 6). (d, e) Electron microscopic evaluation of differentiated primary epithelia from human (d) and monkey (e) in ALI cultures. Scanning electron microscopy of 4-week ALI epithelial cultures (top panels) at the given magnification demonstrating abundant cilia. Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) demonstrating multiple epithelial cell types in the ALI cultures from (d) human and (e) monkey, and native monkey tracheal epithelia (right bottom panel in e).

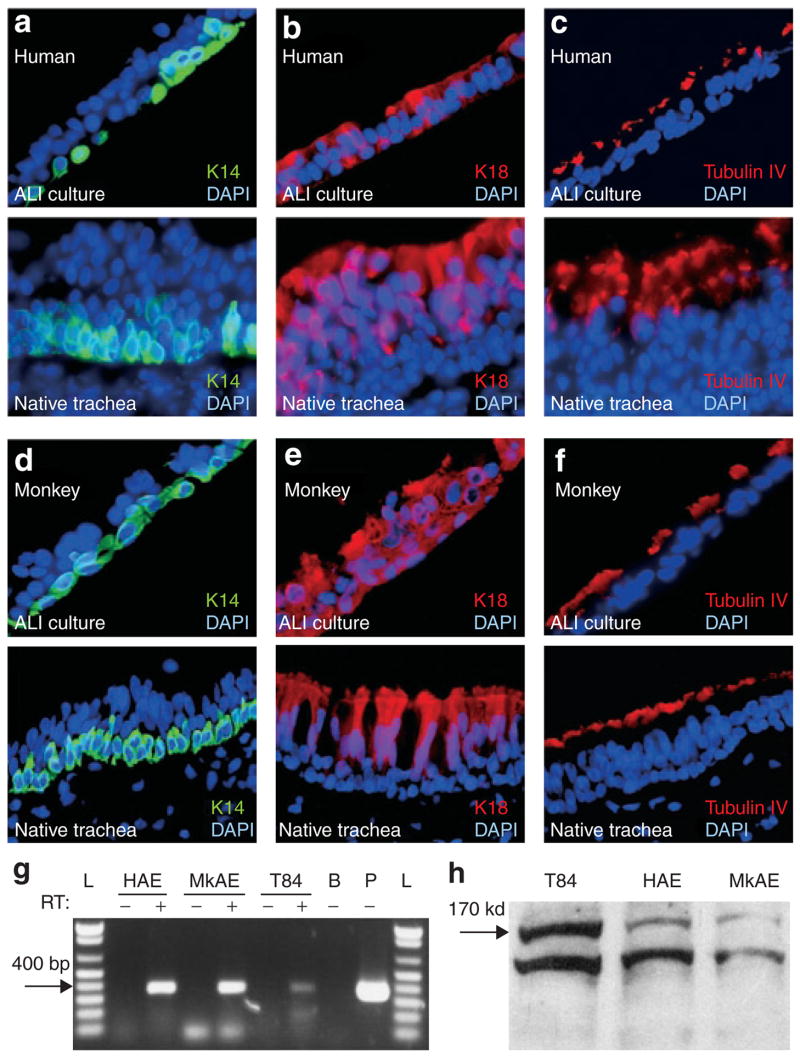

In order to further characterize the differentiated state of monkey tracheal epithelia grown at the ALI, we used several known differentiation markers. As with native human and adult monkey tracheal epithelia, the ALI cultures exhibited keratin 14 expression only in the basal cell layer (Figure 2a and d) and β-tubulin-IV in ciliary axonemes (a feature characteristic of ciliated cells) (Figure 2c and f). However, as previously seen in pig and ferret ALI cultures,24 keratin 18 expression was seen throughout the epithelial layers of monkey and human polarized epithelia (Figure 2b and e), whereas it was limited to columnar cells in native monkey and human tracheal epithelia. We hypothesize that this difference is induced by the substrata on which the ALI cultures are established. CFTR expression is also a critical indicator of the fidelity of in vitro differentiated airway epithelial model systems.16,24 In order to investigate this further, we compared CFTR expression in ALI cultures from monkeys and humans using reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction, and observed CFTR messenger RNA in both epithelia (Figure 2g). Western blotting of ALI cultures also demonstrated that fully processed CFTR protein was also present in similar abundance in airway epithelia of both species (Figure 2h). Consistent with previous reports for primary airway epithelial cultures from other species,16,24 the above analyses suggested that similar differentiated states of airway epithelia can be established with monkey and human tissues.

Figure 2. Expression of cell-specific epithelial markers and cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) in primary air–liquid interface (ALI) cultures from monkeys.

Immunostaining for the epithelial cell markers (a, d) keratin 14, (b, e) keratin 18, and (c, f) tubulin-IV (which marks cilia) in ALI-cultured epithelia from human (a–c) and monkey (d–f) (top panels) and native tracheal epithelia (bottom panels). CFTR expression was compared between T84 cells, ALI-cultured human airway epithelia (HAE), and ALI-cultured monkey airway epithelia (MkAE) using both (g) reverse transcriptase (RT) polymerase chain reaction and (h) Western blotting using an anti-CFTR antibody. L: DNA molecular weight ladder; B: no RNA blank control; P: pBQ-CFTR complementary DNA plasmid positive control. The addition or omission of RT is indicated as a ±. DAPI, 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole.

Bioelectric properties of primary airway epithelial cultures from Indian Rhesus monkey

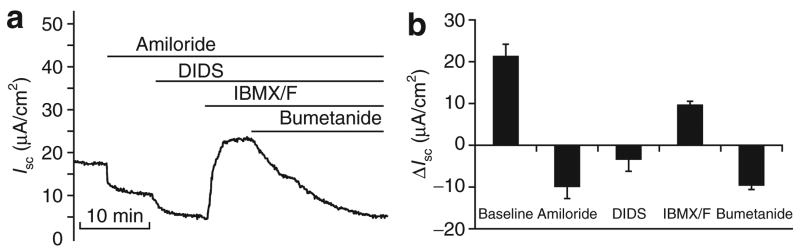

The electrophysiologic characteristics of ALI epithelial cultures provide useful functional information on the differentiated state of the epithelium. This information is also useful in functionally assessing the relatedness of airway biology of a particular species to that of humans. In order to characterize trans-epithelial ion transport in the ALI epithelial cultures from monkeys, we recorded changes of short-circuit current (Isc) following the addition of several channel antagonists and agonists as described in Materials and Methods. As shown in Figure 3, baseline Isc of the monkey ALI cultures was 21.3 ± 2.9 μA/cm2, which was lower than that of human ALI cultures (42.6 ± 3.7 μA/cm2).16,24 The addition of amiloride (to inhibit the epithelial sodium conductance) and 4,4′-diisothiocyanato-stilbene-2,2′-disulfonic acid (to block other non-CFTR Cl− channels) significantly reduced Isc to similar extents as previously observed in ALI cultures of human epithelia.16,24 Trans-epithelial current was also greatly stimulated by the addition of a mixture of cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) agonists (10 μmol/l forskolin and 100 μmol/l 3-isobutyl-l-methylxanthine (IBMX)), both of which are known to induce CFTR-mediated Cl− current. The change in Isc (ΔIsc) for ALI cultures of monkey epithelia (9.87 ± 1.2 μA/cm2) was very similar to that previously reported for ALI cultures of human epithelia (13.38 ± 1.5 μA/cm2).16,24 The addition of bumetanide (to block transepithelial Cl− secretion) to the basolateral solution completely inhibited the forskolin/IBMX-induced Isc, thereby indicating that the Isc was cAMP-inducible Cl− current. These findings demonstrate the presence of an epithelial sodium conductance, non-CFTR Cl− channel(s) and CFTR in monkey airway epithelium.

Figure 3. Short-circuit current (Isc) profiles of air–liquid interface (ALI) cultures of monkey epithelia.

Isc tracings of Indian Rhesus monkey air-way epithelial cultures were assessed under secretory conditions following the sequential addition of amiloride, 4,4′-diisothiocyanato-stilbene-2,2′-disulfonic acid (DIDS), cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) agonists (IBMX/forskolin) and bumetanide (as described in the Materials and Methods). (a) Representative recording of Isc from an ALI culture of monkey airway epithelia following the addition of amiloride, DIDS, IBMX/forskolin and bumetanide. (b) Mean delta Isc(ΔIsc) in response to the addition of amiloride, DIDS, cAMP agonists IBMX/forskolin, and bumetanide to ALI cultures of monkey tracheal epithelia. ΔIsc was calculated as the steady phase current following stimulation, minus the current immediately before chemical addition. Values depict the mean ± SEM for eight independent epithelia, measured in eight different experiments. IBMX, 3-isobutyl-1-methylxanthine.

Pharmacology of Cl− secretion in primary epithelial cultures from Indian Rhesus monkey

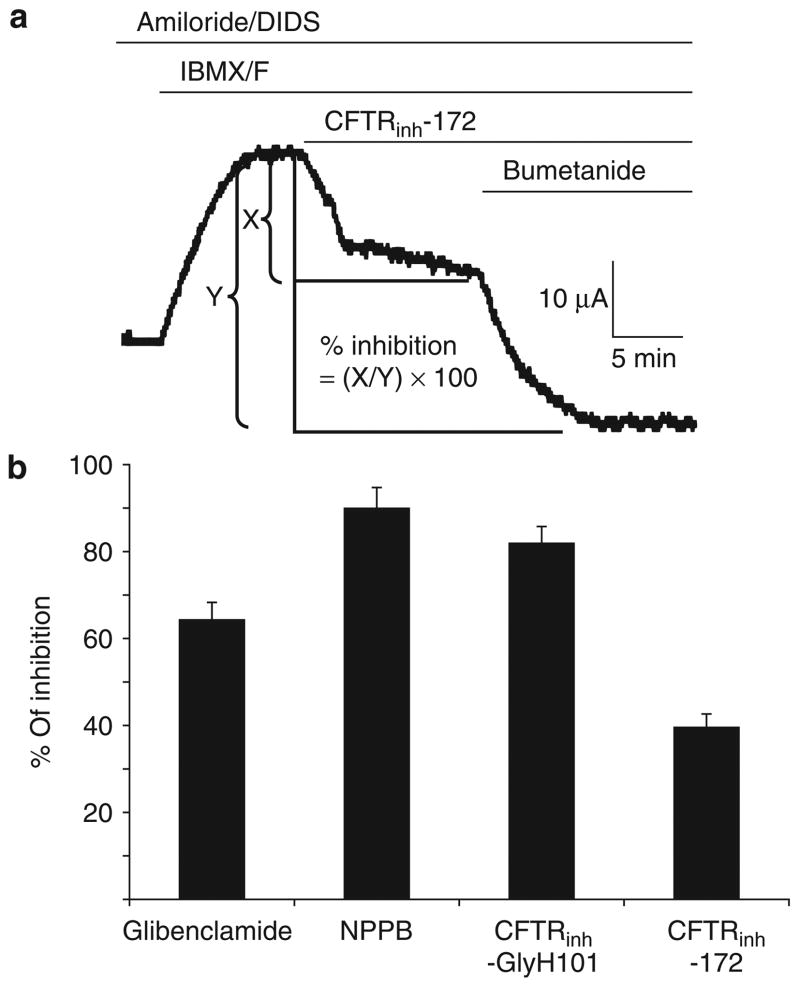

In order to functionally characterize the relatedness of chloride transport properties of monkey and human airway epithelia, we tested the effects of two general anion channel blockers (5-nitro-2-(3-phenylpropylamino)benzoic acid (NPPB) and glibenclamide) and two human CFTR-specific inhibitors (CFTRinh-172 and CFTRinh-GlyH101) for their ability to inhibit IBMX/forskolin-stimulated Cl− current (Figure 4). Both glibenclamide and NPPB have been shown to functionally inhibit a number of different anion channels, including CFTR, in airway epithelia,25,26 whereas CFTRinh-172 and CFTRinh-GlyH101 have high affinity for CFTR, and specifically inhibit the channel in human epithelia.27–29 In human epithelia, each of these four channel blockers have been shown to inhibit CFTR-mediated Cl− secretion in ALI cultures at >75% efficiency at the doses we used in our studies.24 We found significant inhibition of the cAMP-stimulated Cl− current in response to the addition of glibenclamide, NPPB and CFTRinh-GlyH101, with similar levels to that previously seen in ALI cultures of human epithelia.24 However, only a modest reduction in cAMP-stimulated Cl− current was seen in response to CFTRinh-172 (approximately 40%) (Figure 4), as compared to an approximately 75% inhibition in ALI cultures of human epithelia.24 At the tested concentrations, the percentages of inhibition by glibenclamide, NPPB, CFTRinh-GlyH101, and CFTRinh-172 were 64.4 ± 4.7, 90.1 ± 3.8, 82.1 ± 2.9, 39.9 ± 3.4, respectively (Figure 4b). The reduced response to CFTRinh-172 in the monkey airway epithelium, as compared to that of human, may reflect subtle functional/structural differences in CFTR between these two species. Overall, however, the bioelectric characteristics of Cl− currents ALI cultures in both species were strikingly similar, thereby suggesting that their biology is highly conserved.

Figure 4. Effects of chloride channel blockers on the IBMX/forskolin-stimulated Cl− conductance in air–liquid interface (ALI) cultures of monkey epithelia.

Short-circuit current (Isc) from monkey airway epithelia were evaluated, starting in the presence of amiloride/DIDS, and followed by the sequential addition of IBMX/forskolin, one of the following chloride channel blockers (glibenclamide, NPPB, CFTRinh-GlyH101, or CFTRinh-172), and finally bumetanide to determine the remaining cAMP-inducible chloride current. (a) Example of analysis used for calculating the percentage of inhibition by each chloride channel blocker using a representative tracing for evaluating CFTRinh-172. The fraction of IBMX/forskolin-inhibited Isc in response to each inhibitor (X), relative to the total level of inhibition achieved following sequential addition of bumetanide (Y), was used for calculating the percentage of inhibition by each inhibitory compound. (b) Summary of percentage of inhibition of the cAMP-mediated chloride secretory response by each of the indicated chloride channel blockers. Values depict the mean ± SEM % of inhibition for at least eight independent epithelia from three independent donors. cAMP, cyclic adenosine monophosphate; CFTR, cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator; DIDS, 4,4′-diisothiocyanato-stilbene-2,2′-disulfonic acid; IBMX, 3-isobutyl-l-methylxanthine; NPPB, 5-nitro-2-(3-phenylpropylamino)benzoic acid.

rAAV-mediated gene transfer to airway epithelial cultures from Indian Rhesus monkey

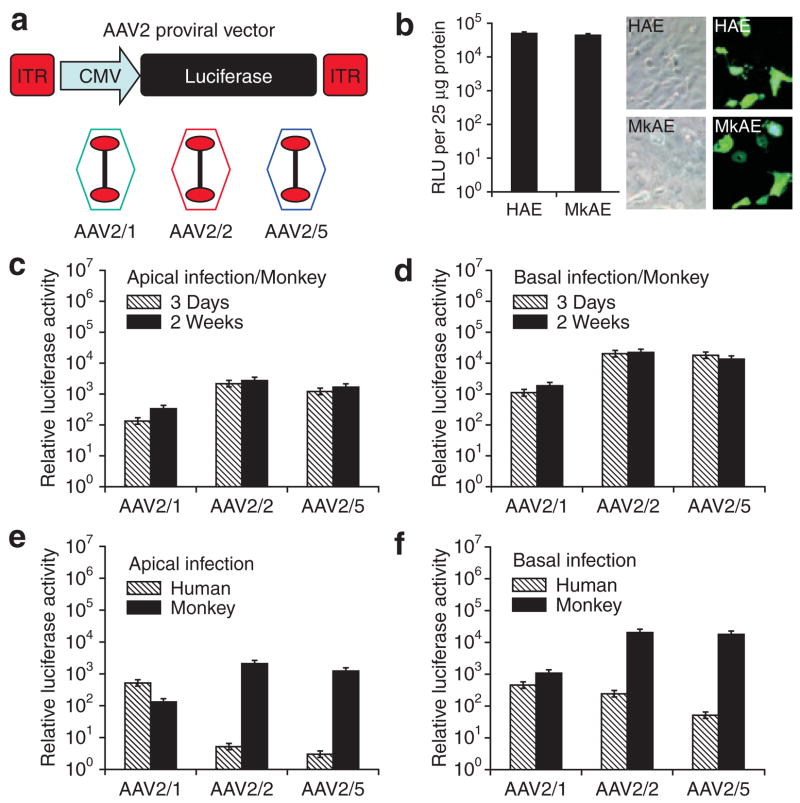

rAAV1, 2, and 5 are among the most commonly studied serotypes for gene transfer to the lung. Studies have shown that gene transfer utilizing these rAAV serotypes shows species-specific tropisms in ALI cultures of murine and human airways.16,18,30 In order to determine whether non-human primate airway epithelia closely reflects the rAAV serotype preference previously determined in human ALI cultures,30 we evaluated rAAV transduction in ALI cultures from Indian Rhesus monkeys, using cytomegalovirus (CMV) promoter-driven luciferase vectors based on rAAV serotypes 1, 2, and 5 (Figure 5a).16,30

Figure 5. Comparison of adeno-associated virus (AAV) transduction in air–liquid interface (ALI) cultures of airway epithelia from monkeys and humans.

(a) Illustration of the proviral vector used to pseudo-type package into rAAV1, rAAV2, or rAAV5 capsids to generate rAAV2/1, rAAV2/2, or rAAV2/5 recombinant virus, respectively. (b) Expression of the cytomegalovirus (CMV) promoter in human and monkey airway epithelia. Human and monkey airway epithelial monolayer cultures were co-transfected with proviral plasmids pAV2.CMV-Luciferase and pAV2. CMV-EGFP together with pRSV-Renilla luciferase expression plasmid. The ratio of relative lights units (RLU) (CMV-Firefly luciferase/RSV-Renilla luciferase) was determined using a dual luciferase reporter assay and is an index of CMV promoter activity (right panel). The results depict the mean ± SEM (N = 3). Fluorescent photomicrographs and Nomarksi images for enhanced green fluorescent protein (EGFP)-expressing cells (left panel). (c, d) Three weeks after the establishment of ALI, the monkey airway epithelial cultures were infected with 50 μl of virus (serotype 1, 2, or 5)-containing medium applied to the (c) apical or (d) basolateral surface of the epithelium, at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 2.0 × 103 particles/cell. Relative luciferase activity was measured on day 3 and at 2 weeks after the infection. (e, f) Comparison of recombinant adeno-associated virus (rAAV) transduction in polarized airway epithelia from humans and monkeys. Airway epithelial ALI cultures from monkey or human were infected at an MOI of 2.0 × 103 particles/cell from either the (e) apical surface or (f) basolateral surface and luciferase activity was assessed at 3 days after infection. Data represent the means (±SEM) of the relative luciferase activity (per well) from three independent experiments. ITR, inverted terminal repeat.

Before assessing differences in rAAV transduction efficiency between these two species (using gene expression as an endpoint), it was important to demonstrate that the CMV promoter used for driving luciferase expression is equally active in the airway cells of both humans and monkeys. To this end, we co-transfected three plasmids containing various promoters and reporters (pAV2. CMV-Luciferase, pAV2.CMV-EGFP, and pRSV-Renilla luciferase) into primary monolayer cultures of airway epithelial cells from humans and monkeys. The CMV-EGFP reporter was used for determining the percentage of cells transfected, while the ratio of activity levels of CMV-Firefly luciferase/RSV-Renilla luciferase was used for assessing the relative activity of the CMV promoter. Forty-eight hours following liposome-mediated transfection, a similar percentage of cells expressed the enhanced green fluorescent protein (EGFP) transgene in the primary airway cells of both the species (Figure 5b). Additionally, the ratio of the activity levels of CMV-Firefly luciferase/RSV-Renilla luciferase was also similar in the airway cell cultures from both species (Figure 5b). These findings demonstrate that expression from the CMV promoter is very similar in the airway cells of both humans and monkeys. Therefore, differences in rAAV transduction efficiency between these two species can be evaluated using CMV-driven reporter gene expression.

We next sought to evaluate rAAV serotype 1, 2, and 5 transduction efficiencies in ALI cultures of the two species using the rAAV CMV-Luciferase viruses (Figure 5a). Our results demonstrate that rAAV serotype 2 (rAAV2/2) vector transduced ALI cultures of monkey epithelia with an efficiency similar to that of serotype 5 (rAAV2/5) vector (Figure 5c); however, basolateral infection was approximately tenfold greater than apical infection for both serotypes (Figure 5d). Notably, when rAAV2/2 and rAAV2/5 serotypes were used, apical transduction of human airway epithelia was approximately 400-fold lower than that seen in monkey epithelia (Figure 5e). Similar results were also seen following basal transduction (Figure 5f). However, cultures from both species shared polarity of transduction with both of these serotypes (basal > apical), although this was more pronounced in cultures of human epithelia. Interestingly, when using the rAAV2/1 serotype virus, both apical and basolateral gene transfer to ALI cultures of monkey epithelia was approximately 10-fold to 30-fold lower than that achieved with rAAV2/2 and AAV2/5 (Figure 5c and d). This finding is in stark contrast to the approximately 100-fold higher levels of apical gene transfer seen with rAAV2/1-based vectors in ALI cultures of human epithelia, relative to levels produced by rAAV2/2 and AAV2/5 (Figure 5e).30 Furthermore, rAAV2/1 infection of ALI cultures of monkey epithelia demonstrated a tenfold preference for transduction of the basolateral surface, whereas human airway epithelia demonstrated a lack of polarity bias of transduction with this serotype (Figure 5e and f).30 With these three rAAV serotypes, similar results were seen with regard to both the tropism and the polarity of infection in ALI cultures generated from tracheas of Cynomolgus monkey, which is also an Old World monkey (data not shown). These findings demonstrate that proximal airway epithelia from Old World monkeys have a biology that is divergent from that of humans, and that this influences rAAV transduction with these three serotypes.

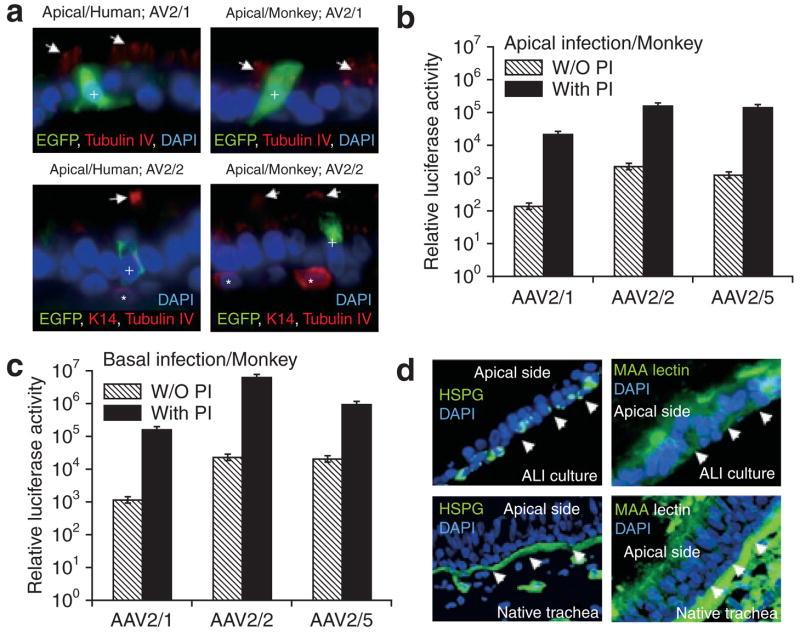

We hypothesized that the differences in transduction effected by various rAAV serotypes in the monkey and human airway epithelia may be reflected in cell-type-specific biases of transduction. In order to investigate this hypothesis, ALI cultures from airway epithelia from both species were apically infected with rAAV2/1, rAAV2/2, and rAAV2/5 vectors expressing a CMV-EGFP transgene (multiplicity of infection = 2,000 particles/cell). At 7 days after infection, immunostaining for EGFP and two cell-specific markers was performed in frozen section. The co-localization of EGFP with the K14 basal cell marker, or tubulin-IV ciliated cell marker, was used for determining the fraction of transgene-expressing cells in three categories: EGFP expressing basal cells (K14 positive), ciliated cells (tubulin-IV positive), and non-ciliated column cells (K14 and tubulin-IV negative). The results from these studies demonstrated that EGFP expression was observed only in non-ciliated cells for all tested rAAV serotypes in ALI cultures of both the species (Figure 6a and data not shown). That is, the differences between the two species with regard to transduction efficiencies produced by the various serotypes, were not reflected by any difference in the cell types transduced. It is currently unclear whether ciliated and/or non-ciliated cells are essential targets for gene therapy of the CF airway.31 Should ciliated cells be essential targets, the serotypes tested may require concurrent application of proteasome inhibitors, which have been shown to enhance transduction of human ciliated cells with rAAV2.32

Figure 6. Cell types transduced by recombinant adeno-associated virus (rAAV) and the effect of proteasome-modulating agents on rAAV transduction.

(a) Examples of immunostaining for enhanced green fluorescent protein (EGFP), K14, and/or tubulin-IV in the airway cultures infected with the indicated CMV-EGFP expressing rAAV viruses. Primary airway epithelial cultures from humans and monkeys were infected with 2.0 × 103 particles/cell of AV2.CMV-EGFP (Serotype 1, 2, or 5) virus from the apical surface. EGFP-expressing cells were detected by immunofluoresence for EGFP, K14, and/or tubulin-IV on frozen section of the membranes at 7 days after infection. EGFP staining was observed only in non-ciliated (K14/tubulin-IV negative) cells. Arrows indicate tubulin-IV staining for ciliated cells while asterisks indicate basal cells (K14 positive). (b, c) Airway epithelial air–liquid interface (ALI) cultures from monkeys were infected at an multiplicity of infection of 2.0 × 103 particles/cell from either the (b) apical surface or (c) basolateral surface in the presence or absence of proteasome inhibitors (PIs) Dox and LLnL, and luciferase activity was assessed at 3 days after infection. Data represent the means (±SEM) of the relative luciferase activity (per well) from three independent experiments (N = 12 transwells for each experimental point). (d) Immunostaining for heparan sulfate proteoglycan and 2,3-linked sialic acid using the Maackia amurensis (MAA) lectin on sections from ALI cultures of monkey airway epithelia, and native monkey trachea. Arrowheads mark the basal side of the epithelia. CMV, cytomegalovirus; DAPI, 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole; HSPG, heparan sulfate proteoglycan.

Responsiveness of rAAV transduction to proteasome inhibitors in monkey airway epithelial cultures

Previous studies have demonstrated that rAAV intracellular processing is a major rate-limiting step in transduction.32–35 This is especially true in the airway.32 Proteasome inhibitors have been shown to enhance rAAV transduction by promoting nuclear accumulation of virus.18,32 Apical transduction of polarized human airway epithelia with rAAV2 and rAAV5 can be significantly augmented by the presence of proteasome-modulating agents.18 Interestingly, the efficiency of transduction from the apical surface with a given serotype appears to correlate indirectly with the extent of proteasome blockage.30 In order to investigate whether such rate-limiting features of rAAV transduction are at work in the monkey airway epithelium, we evaluated rAAV transduction in the presence of the proteasome-modulating agents LLnL and doxorubicin. These studies demonstrated that all three serotypes were induced to a similar extent (approximately 100-fold) by the addition of proteasome inhibitors following both apical and basolateral infection of monkey epithelia (Figure 6b and c). There were notable differences between ALI cultures of the two species with regard to the extent of induction by proteasome inhibitors when the rAAV2/1 vector was used. In human airway epithelium, the rAAV2/1 serotype is the most efficient at apical transduction and the least induced by proteasome inhibitors, when compared with rAAV2/2 and rAAV2/5.30 In contrast, in ALI cultures of monkey epithelia, rAAV2/1 was the least effective at apical transduction, and induction with proteasome inhibitors was similar to that seen with rAAV2/2 and with rAAV2/5 (approximately 100-fold). These findings suggest that intracellular trafficking remains a major rate-limiting step in rAAV2/1 transduction to monkey airway epithelia, but not human airway epithelium.

N-linked sialic acid involvement in rAAV binding and transduction of airway epithelia

In addition to the presence of intracellular barriers, the abundance of viral receptors and co-receptors on the cell surface of the airway will also influence the extent of transduction with various rAAV serotypes. Two potential AAV1 binding receptors include both α2,3 and α2,6 N-linked sialic acid on cell surfaces.36 AAV2 has been suggested to utilize several binding receptors including heparan sulfate proteoglycan (HSPG), αVβ5 integrin, hepatocyte growth factor receptor, and human fibroblast growth factor receptor 1.37–40 In contrast, AAV5 appears to utilize 2,3-linked sialic acid and platelet-derived growth factor as binding receptors.41,42 In order to determine the localization of known rAAV receptors in monkey airway epithelia, we compared staining patterns for HSPG and 2,3-linked sialic acid (using Maackia amurensis (MAA) lectin binding) between ALI cultures of monkey epithelia and native trachea (Figure 6d). Consistent with the localization patterns in human airway epithelia,43 HSPG localized predominantly to the basal membrane of ALI cultures of monkey epithelia. As in ALI cultures of human epithelia,41 MAA lectin binding was seen predominantly on the apical, and to a lesser extent on the basal, surface of monkey epithelia. These patterns generally held true in the native monkey trachea, although in this case the lectin staining in the basal membrane was much more pronounced than in the apical membrane (Figure 6d).

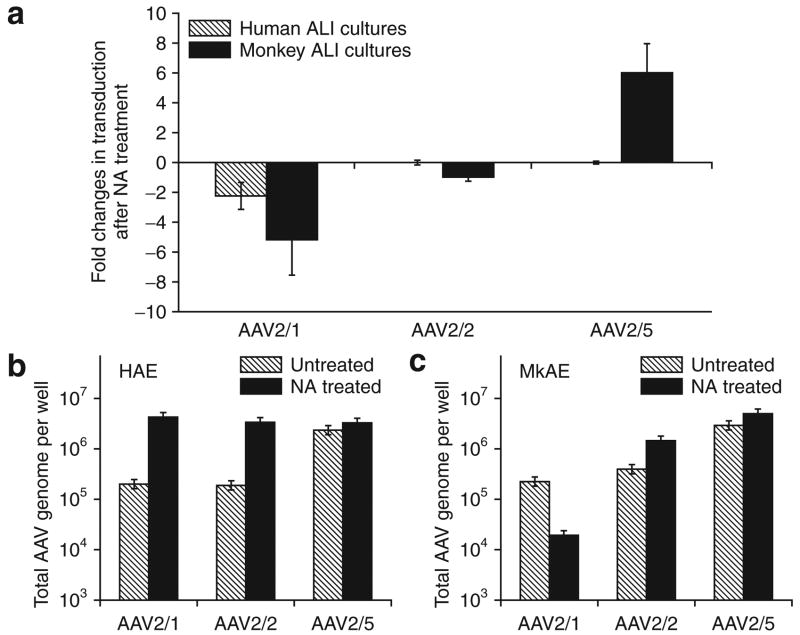

The finding of α2,3 N-linked sialic acid (a known receptor for both AAV1 and AAV5) on the apical surface of monkey airway epithelia did not correlate with the divergent levels of transduction with these two serotypes. In order to test whether the α2,3 and α2,6 N-linked sialic acid are receptors for AAV1 binding in airway epithelia from humans and monkeys, we evaluated the efficiencies of rAAV binding and transduction in ALI cultures of the two species following neuraminidase (NA) removal of N-linked sialic acid from the apical surface.36,44 Results from these studies demonstrated that rAAV2/1 transduction from the apical surfaces was significantly decreased in ALI cultures in both the species by NA treatment (Figure 7a). These results are consistent with previous reports suggesting that N-linked sialic acid is a receptor for AAV1.36 It is interesting, however, that rAAV2/1 transduction of monkey epithelia was more significantly inhibited by NA treatment, despite the fact that this serotype transduced human epithelia more effectively. By contrast, NA treatment did not affect apical transduction in the epithelia of either species with the rAAV2/2 serotype (Figure 7a), thereby supporting reports from previous studies that N-linked sialic acids are not receptors for AAV2 binding. Surprisingly, pretreatment of ALI cultures of monkey epithelia with NA significantly enhanced rAAV2/5 transduction (approximately sixfold), whereas such pretreatment did not alter transduction of ALI cultures of human epithelia, when this serotype was used (Figure 7a). These finding suggested that N-linked sialic acids inhibit type 5 serotype apical transduction of monkey airway epithelia in a species-specific manner.

Figure 7. Differences in recombinant adeno-associated virus (rAAV) binding and transduction between airway epithelia of humans and monkeys.

Airway epithelial air–liquid interface (ALI) cultures from humans and monkeys were treated with neuraminidase (NA) or Ultroser G control medium (Untreated) before binding of rAAV Luciferase virus (multiplicity of infection of 2.0 × 103 particles/cell) to the apical surface at 4 °C for 1 hour. The infected cultures were either directly used for analysis of viral binding by quantitative polymerase chain reaction (PCR) for viral genomes, or for evaluating transduction by measuring relative luciferase activity at 3 days after infection. (a) The multiple of change in viral transduction, as determined by luciferase expression, following NA treatment. (b, c) Quantification of rAAV binding to airway epithelia from (b) human and (c) monkey by detection of viral genomes using Taqman PCR. Data represent the means (±SEM) of the relative luciferase activity and numbers of rAAV viral genome (per well) from three independent experiments. HAE, human airway epithelia; MkAE, monkey airway epithelia.

In order to get a better understanding of how N-linked sialic acids may alter transduction with the various serotypes in a species-specific manner, we next analyzed how NA treatment influences rAAV binding to the apical surface of epithelia (Figure 7b and c). Results from this analysis demonstrated that indeed NA treatment significantly alters binding of certain serotypes to the apical membrane; however, these alterations do not always correlate with changes in transduction. For example, NA treatment increased binding of rAAV2/1 to human airway epithelia more than 50-fold (Figure 7b), but inhibited transduction. On the other hand, NA treatment significantly decreased both apical binding of rAAV2/1 and transduction in monkey airway epithelia (Figure 7a and c). In the context of rAAV2/5, NA treatment did not alter binding of this serotype to the apical surface of airway epithelia in either species. This finding is consistent with the observation that this serotype, with NA treatment, produces no change in transduction of ALI cultures of human epithelia; however, it is in stark contrast to the sixfold enhancement in transduction in monkey epithelia following NA treatment. These findings demonstrate that sialic acid residues on the surface of airway epithelia in the two species differentially affect transduction and binding of the AAV serotypes studied. We hypothesize that N-linked sialic acid co-receptor interactions with species-specific AAV receptors may differentially direct viruses to endosomal compartments having different capacities to facilitate productive transduction. This interpretation is consistent with previous findings that implicate intracellular trafficking of rAAV as a critical step in productive transduction.18,30,32,34,45

DISCUSSION

On the basis of their close genetic relationship with humans, NHPs have been considered the “gold standard” for testing in vivo gene transfer before clinical trials. The assumption that NHPs will closely mirror vector biology of the human lung stems from the close similarities in the lung cell biology of the two species.5,6,46 In this study, we sought to evaluate whether rAAV vector biology in airway epithelia of NHPs is truly reflective of that in humans. Such studies are relevant to the use of NHPs as surrogate models for testing the efficiency of gene transfer to the airways of humans in diseases such as CF.

Before initiating experiments to compare aspects of AAV vector biology, it was important to demonstrate that the ALI epithelia generated from monkey and human airway tissues were of similar quality, as reflected by their differentiated status. In this context, molecular and bioelectric analyses of ALI cultures from monkeys demonstrated similarities with the abundance of differentiated cell types and types of channels seen in ALI cultures of human epithelia.24 Chloride channel pharmacology was also extremely similar to that seen in human airway epithelia.24 These similarities between airway epithelia in NHPs and humans are consistent with their highly conserved cell biology.

Given the highly conserved cell biology and bioelectric properties of the airway epithelia of these two species, one would anticipate that rAAV vector biology would also be closely similar between them. However, our studies demonstrated striking differences in the profiles of transduction in human and NHP airway epithelia with the three rAAV serotypes tested. Both rAAV2/2 and rAAV2/5 transduced monkey or human airway epithelia with equal preference following apical infection. However, the efficiency of transduction of ALI cultures from monkey airway epithelia with these two serotypes was much higher (400-fold) than that seen in human airway epithelia. The implication of these findings is that the high levels of gene transfer achieved with these serotypes in preclinical trials involving Old World NHPs might grossly overestimate what is possible to achieve in human clinical trials. Indeed, preclinical studies in Old World NHPs (Rhesus macaques) with rAAV2-CFTR vector have demonstrated persistence of transgene-derived CFTR messenger RNA expression up to 180 days,12 whereas clinical trials with this same vector have failed to detect transgene-derived messenger RNA in human CF lungs.23 Such findings support the theory that NHPs may not fully predict the efficacy of rAAV gene transfer in humans.

rAAV2/1 also demonstrated disparate results in its efficiency of transduction of ALI cultures of the two species from the apical surface, although these differences were much less pronounced than for the other serotypes. This could be seen not only in the absolute efficiency of transduction, which was approximately fourfold greater in airway epithelia from humans than from monkeys, but also in the relative levels of transduction among the three serotypes tested. In the context of ALI cultures of human epithelia, the efficiency of transduction with the three serotypes tested was rAAV2/1≫rAAV2/2≅rAAV2/5.30 However, in monkey airway epithelia the ordered efficiency of transduction was reversed, rAAV2/2≅rAAV2/5>rAAV2/1. Additionally, rAAV2/1 demonstrated unique biologic properties in human airway epithelia that were not mirrored in NHP cultures. For example, rAAV2/1 lacks a bias in polarity of transduction (apical = basolateral) with rAAV2/2 and rAAV2/5 vectors,30 whereas, in monkey airway epithelia, rAAV2/1 transduced the basolateral membrane tenfold more effectively than the apical membrane. In view of the difference in proteasome responsiveness of rAAV2/1 between human and monkey epithelia, these findings suggest that AAV1 apical transduction of monkey airway epithelia is associated with a greater proteasome-dependent post-entry block, that is significantly less pronounced in human airway epithelia. The lack of a clear correlation between binding and transduction of the various serotypes to the apical membrane of epithelia also supports post-entry barriers as predominant effectors of species-specific transduction. Furthermore, the removal of N-linked sialic acid promoted reductions or enhancements in transduction that also did not directly correlate with changes in viral binding. These findings support the notion that viral interactions at the surface of airway epithelial cells (with co-receptors and receptors) influence intracellular processing of AAV virions that can alter the efficiency of productive transduction.

Collectively, the results from these studies demonstrate that although Indian Rhesus monkey airway epithelia have bioelectric properties that are very similar to those of human airway epithelia, the use of this species of NHP to study rAAV-mediated gene transfer to the airway may be hindered by species-specific differences in vector biology. These differences appear to hold true for Cynomolgus monkey airway epithelia (data not shown). Old World monkeys (both Rhesus and Cynomolgus) are among the NHPs that are most commonly used for preclinical testing, because they are easily obtained. Our findings may have significant implications for the validity of these models in predicting efficiency of gene transfer in humans. It is presently unclear whether differences in AAV serotype vector biology will be seen in other tissue targets currently being investigated for gene therapy in NHPs. However, it is an issue that warrants further investigation. Of the NHPs, Old World monkeys are considerably more distantly related to humans than New World monkeys (such as Chimpanzees). Although performing preclinical testing on Chimpanzees is considerably more costly and difficult, the use of this model for prioritizing various rAAV serotypes for human clinical trials may be worth serious consideration. Alternatively, expanding the comparison of airway ALI cultures from other NHP species in order to determine which, if any, mirror the serotype profiles seen in human airway epithelia, may also uncover generally useful Old World NHPs that better model preclinical efficacy in humans.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Tracheal epithelial cell isolations and generation of in vitro polarized tracheal epithelia

Tracheas from Indian Rhesus monkey (Macaca mulatta of Indian origin, age range from 1.5 to 8.5 years) were harvested at Tulane National Primate Research Center and shipped on ice to University of Iowa in epithelial cell dissociation buffer (Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium containing 1% penicillin–streptomycin, 1.0 μg/ml Fungizone, 1.5 mg/ml pronase, and 10 μg/ml DNase I). Tracheal tissue remained in dissociation buffer at 4 °C for approximately 48 hours, after which primary airway epithelial cells were harvested and cultured on collagen-coated plates as previously described.24,47 Human tracheal epithelial cells were generated using the same protocol. These primary cultures were harvested following a single passage after they reached 70–90% confluence and used for generating polarized epithelia on supported polycarbonate and polyester porous (0.4 μm pores) membranes as previously described.24 In brief, a 0.6 cm2 Millicell insert membrane was seeded with 2.5 × 105 cells and incubated at 37 °C 5% CO2 for at least 18 hours, with 5% fetal bovine serum modified bronchial epithelial cell culture medium on both sides of the inserts of the 24-well plate. After 3 days of culture, medium from the apical chamber was removed and the outside chamber was fed with 2% Ultroser G to establish an ALI. Thereafter, the medium was changed twice a week. The liquid inside the chamber was removed once daily until the top of the membrane culture remained visibly dry. The transmembrane resistance (Rt) was monitored using an epithelial Ohm–voltmeter. A polarized and highly differentiated airway epithelial cell layer was achieved about 2–3 weeks after ALI culture.

Promoter activities in primary airway epithelial cells

In order to assess whether species-specific differences existed in the activity of the CMV promoter used in AAV vectors, we performed an analysis of promoter activities in transfected primary airway epithelial cells from monkeys and humans. These studies involved co-transfection of three plasmids (pAV. CMV-EGFP, pAV.CMV-Luciferease, and pRSV-Renilla luciferase) into airway epithelial monolayer cultures on collagen-coated 24-well plates using Lipofectamine Plus using methods recommended by the manufacturer (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Expression from the CMV-EGFP transgene was used an an internal control to assess the percentage of transfected cells. The CMV-Firefly luciferease/RSV-Renilla luciferase ratio was determined using a Dual-luciferase assay kit (Promega, Madison, WI). The ratio of luciferase expression in airway epithelial cells from humans to that in monkeys was used as an index for CMV promoter activity.

Electron microscopy and quantification of the relative fraction of ciliated and non-ciliated cells

For electronic microscopy, the ALI culture membranes were fixed with 2.5% glutaraldehyde, stained with 1.25% osmium tetroxide in phosphate-buffered saline, dehydrated, and sputter coated. For scanning electron microscopy, samples were visualized on a Hitachi S-450 microscope (Hitachi, Tokyo, Japan). The area of the apical surface covered by cilia was used to calculate the relative proportions of ciliated and non-ciliated cells in six independent cultures from both human and monkey. Quantification was performed using the polygon selection tool in NIH Image J software on ×1,000 magnification scanning electron microscopy images (total of five images from each culture). For transmission electron microscopy, membranes were fixed as for scanning electron microscopy, infiltrated with Spurr resin after dehydration, and then cut into 80 nm serial sections. These samples were then viewed on a JEOL JEM-1230 Electron Microscope (JEOL, Tokyo, Japan).

Immunofluorescent staining analysis

ZO-1 staining was used for evaluating the formation of tight junctions using whole-mount staining of intact epithelia as previously described.24 Immunofluorescent staining for keratin 14, keratin 18, tubulin-IV, HSPG, α2,3 N-linked sialic acid, were performed on 10 μm frozen sections with the following antibodies or lectins: rabbit anti-human keratin 14 (1:200 dilution; NeoMarkers, Fremont, CA), mouse anti-keratin 18 (1:200 dilution; Clone IB4, Lab Vision, Fremont, CA), mouse anti-tubulin-IV (1:200 dilution; BioGenex, San Ramon, CA), rat anti-HSPG monoclonal antibody (1:100 dilution, Chemicon International, Temecula, CA), and fluorescein isothiocyanate-labeled M. amurensis (MAA) lectin (1:200 dilution, Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA), goat anti-EGFP polyclonal antibody (1:2,000 dilution, Abcam, Cambridge, MA), and the appropriate fluorescently-labeled secondary antibodies when applicable. Specimens were mounted for fluorescence in Vectashield Mounting Medium with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (H-1200, Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA). Images were acquired using a Leica FDC-300F digital camera attached to a fluorescence microscope.

Electrophysiologic characterization of airway epithelia

Three to five weeks after ALI cultures were established, trans-epithelial Isc were measured using an epithelial voltage clamp (Model EC-825) and a self-contained Using chamber system (both were purchased from Warner Instruments, Hamden, CT) as previously described.8,16 The basolateral side of the chamber was filled with buffered Ringer’s solution containing 135 mmol/l NaCl, 1.2 mmol/l CaCl2, 1.2 mmol/l MgCl2, 2.4 mmol/l KH2PO4, 0.2 mmol/l K2HPO4, and 5 mmol/l HEPES, pH 7.4. The apical side of the chamber was filled with a low chloride Ringer’s containing 135 mmol/l Na-gluconate, 1.2 mmol/l CaCl2, 1.2 mmol/l MgCl2, 2.4 mmol/l KH2PO4, 0.2 mmol/l K2HPO4, and 5 mmol/l HEPES, pH 7.4. The following chemicals (all purchased from Sigma) were sequentially added to the apical chamber: (i) amiloride (100 μmol/l) for inhibition of epithelial sodium conductance, (ii) 4,4′-diisothiocyanato-stilbene-2,2′-disulfonic acid (100 μmol/l) to inhibit non-CFTR chloride channels, and (iii) a mixture of the cAMP agonists forskolin (10 μmol/l) and phos-phodiesterase inhibitor IBMX (100 μmol/l) to activate the CFTR channels. Bumetanide (100 μmol/l) was added to the basolateral chamber at the end of each experiment to block transepithelial Cl− secretion. cAMP-inducible changes in Cl− currents were calculated as the bumetanide-inhibitable current in the presence of forskolin and IBMX. Additional experiments were performed to assess the ability of four Cl− channel blockers to inhibit forskolin (10 μmol/l)/IBMX (100 μmol/l) induced chloride currents in the presence of 100 μmol/l amiloride and 100 μmol/l 4,4′-diisothiocyanato-stilbene-2,2′-disulfonic acid. In these studies, the apical chamber was treated with one of the following chemicals before bumetanide was added to the basolateral side: 400 μmol/l glybenclamide, 100 μmol/l NPPB,26 20 μmol/l CFTRinh-172 (2-thioxo-4-thiazolidinone analog) 27,28, or 10 μmol/l CFTRinh-GlyH101 (N-(2-naphthalenyl)-[(3,5-dibromo-2,4-dihydroxyphenyl) methylene] glycine hydrazide).29 Trans-epithelial voltage was clamped at zero, and the resulting Isc was recorded using a Quick DataAcq DT9800 series real-time Data Acquisition USB board and analyzed in Excel files (Data Translation, Marlboro, MA).

CFTR expression in differentiated primary monkey tracheal epithelia

As an index of epithelial differentiation, CFTR expression was evaluated using reverse transcriptase-PCR and Western blotting with rabbit anti-human CFTR antibody. To isolate total RNA, cells were lysed within the Millicell apparatus (5 weeks of ALI culture) by the addition of lysis buffer (Qiagen Total RNA Isolation kit) (Valencia, CA). Cell lysates were collected and pooled, and total RNA was isolated using a Qiagen Total RNA isolation kit according to the manufacturer’s instructions. cDNA synthesis was performed using the Qiagen Omniscript Reverse Transcript Kit. Briefly, 2 μg of total RNA from each sample was mixed with reaction reagents according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Two microliter aliquots of the reverse transcribed products were used for PCR analysis, in a 50 μl reaction volume and with species-conserved primers designed to detect CFTR NBD1 domain (forward primer 5′-CTCTTGGAGCAATAAACAAAATAC-3′, and reverse primer 5′-GAATGAAATTCTTCCACTGTGCTT-3′).24 The PCR products were resolved by electrophoresis on 1% agarose gels, with the expected bands for the CFTR PCR product being 398 base pairs in length. The same amount of total RNA (not reverse transcribed) was used as the PCR-specific cDNA control. For detection of the CFTR protein, epithelial cells from ALI cultures were lysed using radio immunoprecipitation assay buffer, and a 50 μg sample of total protein was resolved by 8% sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis for transfer to a nylon membrane. The resulting blot was probed with anti-CFTR antibody (H-172, Santa Cruz, Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA).

Recombinant AAV luciferase and EGFP reporter vectors, and infection of polarized airway epithelium

rAAVs were generated from the proviral plasmid pAV2.CMV-Luc and pAV2.CMV-EGFP harboring rAAV2 ITRs by packaging into serotype 1 (rAAV2/1), 2 (rAAV2/2), or 5 (rAAV2/5) capsids using triple plasmid transfection of 293 cells as previously described.30 Helper-free virus stocks were treated with nuclease and purified by high performance liquid chromatography. Physical titers of rAAV were determined by slot-blot hybridization, and peak fractions were combined for experimental use.30 After 3 weeks of ALI culture, the epithelial cultures were infected with 50 μl of rAAV-containing medium applied to either the apical or basolateral surface of the epithelia for 16 hours at 37 °C with a multiplicity of infection of 2.0 × 103 particles/cell, with or without the addition of 40 μmol/l LLnL and 5 μmol/l doxorubicin.18,30 Following infection, the virus load was removed and the cultures were fed with fresh media in the absence of virus and/or proteasome inhibitors. The luciferase activity was evaluated at 3 days and 2 weeks after infection as previously described.18,30 Cultures were also infected with rAV.CMV-EGFP virus and evaluated for EGFP expression with cell-specific markers (K14 and tubulin-IV) by co-immunostaining on frozen sections as previously described.

Binding and transduction of rAAV vectors following NA treatment

Sialic acid was removed from the apical surfaces of airway epithelial cultures by applying 200 μl of Ultroser G medium containing 50-mU/ml of type III NA from Vibrio cholerae (Sigma, Santa Louis, MO) for 2 hours at 37 °C. In these studies, treatment with Ultroser G medium alone served as the untreated control. After removal of the NA and three washes with phosphate-buffered saline, the cultures were placed at 4 °C for 10 minutes before the addition of rAAV to the apical surface (multiplicity of infection = 2.0 × 103 particles/cell) in 50 μl of Ultroser G medium. Cultures were then incubated at 4 °C for 1 hour to allow for the virus to bind. The apical surfaces of the cultures were then washed with pre-cold phosphate-buffered saline three times before the cell-associated viral DNA was extracted, or cultures were returned to the incubator for an additional 72 hours so as to evaluate transduction efficiency as described earlier.18,32 Analysis of viral binding was performed using TaqMan PCR on extracted DNA from the cultures. Primers and probe were designed by Primer Express software (PE Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) as follows: the forward primer, 5′-TTTTTGAAGCGAAGGTTGTGG-3′, and the reverse primer, 5′-CACACACAGTTCGCCTCTTTG-3′ were designed to amplify a 32-base pair fragment in the luciferase coding region of the rAAV Luciferase vector. The TaqMan probe, 5′-ATCTGGATACCGGGAAAACGCTGGGCG TTAAT-3′ was tagged with 6-carboxyfluorescein dye at 5′-end as the reporter and tetramethyl-6-carboxyrhodamine dye at 3′-end as the quencher.45 The real-time-PCR was performed in Bio-Rad MyiQ real-time-PCR Detection System (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). Series dilution of the proviral plasmid was used for generating the standard curve, and copy number was determined using previous established criteria.45

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health RO1 HL58340 (J.F.E.), the Center for Gene Therapy (DK54759) and Targeted Genetics Corporation. We also gratefully acknowledge the Roy J Carver Chair in Molecular Medicine (J.F.E.) and Christine Blaumueller for editorial assistance.

References

- 1.Sullivan DE, Dash S, Du H, Hiramatsu N, Aydin F, Kolls J, et al. Liver-directed gene transfer in non-human primates. Hum Gene Ther. 1997;8:1195–1206. doi: 10.1089/hum.1997.8.10-1195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Allocca M, Tessitore A, Cotugno G, Auricchio A. AAV-mediated gene transfer for retinal diseases. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2006;6:1279–1294. doi: 10.1517/14712598.6.12.1279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Preuss TM, Caceres M, Oldham MC, Geschwind DH. Human brain evolution: insights from microarrays. Nat Rev Genet. 2004;5:850–860. doi: 10.1038/nrg1469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Puente XS, Velasco G, Gutierrez-Fernandez A, Bertranpetit J, King MC, Lopez-Otin C. Comparative analysis of cancer genes in the human and chimpanzee genomes. BMC Genomics. 2006;7:15. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-7-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Plopper CG, Heidsiek JG, Weir AJ, George JA, Hyde DM. Tracheobronchial epithelium in the adult rhesus monkey: a quantitative histochemical and ultrastructural study. Am J Anat. 1989;184:31–40. doi: 10.1002/aja.1001840104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.St George JA, Nishio SJ, Plopper CG. Carbohydrate cytochemistry of rhesus monkey tracheal epithelium. Anat Rec. 1984;210:293–302. doi: 10.1002/ar.1092100204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boucher RC. New concepts of the pathogenesis of cystic fibrosis lung disease. Eur Respir J. 2004;23:146–158. doi: 10.1183/09031936.03.00057003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liu X, Luo M, Zhang LN, Yan Z, Zak R, Ding W, et al. Spliceosome-mediated RNA trans-splicing with recombinant adeno-associated virus partially restores cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator function to polarized human cystic fibrosis airway epithelial cells. Hum Gene Ther. 2005;16:1116–1123. doi: 10.1089/hum.2005.16.1116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhang LN, Karp P, Gerard CJ, Pastor E, Laux D, Munson K, et al. Dual therapeutic utility of proteasome modulating agents for pharmaco-gene therapy of the cystic fibrosis airway. Mol Ther. 2004;10:990–1002. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2004.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sirninger J, Muller C, Braag S, Tang Q, Yue H, Detrisac C, et al. Functional characterization of a recombinant adeno-associated virus 5-pseudotyped cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator vector. Hum Gene Ther. 2004;15:832–841. doi: 10.1089/hum.2004.15.832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Flotte T, Carter B, Conrad C, Guggino W, Reynolds T, Rosenstein B, et al. A phase I study of an adeno-associated virus-CFTR gene vector in adult CF patients with mild lung disease. Hum Gene Ther. 1996;7:1145–1159. doi: 10.1089/hum.1996.7.9-1145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Conrad CK, Allen SS, Afione SA, Reynolds TC, Beck SE, Fee-Maki M, et al. Safety of single-dose administration of an adeno-associated virus (AAV)-CFTR vector in the primate lung. Gene Ther. 1996;3:658–668. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Flotte TR, Zeitlin PL, Reynolds TC, Heald AE, Pedersen P, Beck S, et al. Phase I trial of intranasal and endobronchial administration of a recombinant adeno-associated virus serotype 2 (rAAV2)-CFTR vector in adult cystic fibrosis patients: a two-part clinical study. Hum Gene Ther. 2003;14:1079–1088. doi: 10.1089/104303403322124792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wagner JA, Nepomuceno IB, Messner AH, Moran ML, Batson EP, Dimiceli S, et al. A phase II, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trial of tgAAVCF using maxillary sinus delivery in patients with cystic fibrosis with antrostomies. Hum Gene Ther. 2002;13:1349–1359. doi: 10.1089/104303402760128577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gao G, Vandenberghe LH, Wilson JM. New recombinant serotypes of AAV vectors. Curr Gene Ther. 2005;5:285–297. doi: 10.2174/1566523054065057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liu X, Yan Z, Luo M, Engelhardt JF. Species-specific differences in mouse and human airway epithelial biology of recombinant adeno-associated virus transduction. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2006;34:56–64. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2005-0189OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Duan D, Yan Z, Yue Y, Ding W, Engelhardt JF. Enhancement of muscle gene delivery with pseudotyped adeno-associated virus type 5 correlates with myoblast differentiation. J Virol. 2001;75:7662–7671. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.16.7662-7671.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yan Z, Zak R, Zhang Y, Ding W, Godwin S, Munson K, et al. Distinct classes of proteasome-modulating agents cooperatively augment recombinant adeno-associated virus type 2 and type 5-mediated transduction from the apical surfaces of human airway epithelia. J Virol. 2004;78:2863–2874. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.6.2863-2874.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Song S, Scott-Jorgensen M, Wang J, Poirier A, Crawford J, Campbell-Thompson M, et al. Intramuscular administration of recombinant adeno-associated virus 2 alpha-1 antitrypsin (rAAV-SERPINA1) vectors in a nonhuman primate model: safety and immunologic aspects. Mol Ther. 2002;6:329–335. doi: 10.1006/mthe.2002.0673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hadaczek P, Kohutnicka M, Krauze MT, Bringas J, Pivirotto P, Cunningham J, et al. Convection-enhanced delivery of adeno-associated virus type 2 (AAV2) into the striatum and transport of AAV2 within monkey brain. Hum Gene Ther. 2006;17:291–302. doi: 10.1089/hum.2006.17.291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Davidoff AM, Gray JT, Ng CY, Zhang Y, Zhou J, Spence Y, et al. Comparison of the ability of adeno-associated viral vectors pseudotyped with serotype 2, 5, and 8 capsid proteins to mediate efficient transduction of the liver in murine and nonhuman primate models. Mol Ther. 2005;11:875–888. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2004.12.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gao G, Lu Y, Calcedo R, Grant RL, Bell P, Wang L, et al. Biology of AAV serotype vectors in liver-directed gene transfer to nonhuman primates. Mol Ther. 2006;13:77–87. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2005.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Moss RB, Rodman D, Spencer LT, Aitken ML, Zeitlin PL, Waltz D, et al. Repeated adeno-associated virus serotype 2 aerosol-mediated cystic fibrosis transmembrane regulator gene transfer to the lungs of patients with cystic fibrosis: a multicenter, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Chest. 2004;125:509–521. doi: 10.1378/chest.125.2.509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liu X, Luo M, Zhang L, Ding W, Yan Z, Engelhardt JF. Bioelectric properties of chloride channels in human, pig, ferret, and mouse airway epithelia. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2007;36:313–323. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2006-0286OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ballard ST, Trout L, Garrison J, Inglis SK. Ionic mechanism of forskolin-induced liquid secretion by porcine bronchi. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2006;290:L97–L104. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00159.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhang AL, Roomans GM. Multiple intracellular pathways for regulation of chloride secretion in cultured pig tracheal submucosal gland cells. Eur Respir J. 1999;13:571–576. doi: 10.1183/09031936.99.13357199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Thiagarajah JR, Song Y, Haggie PM, Verkman AS. A small molecule CFTR inhibitor produces cystic fibrosis-like submucosal gland fluid secretions in normal airways. FASEB J. 2004;18:875–877. doi: 10.1096/fj.03-1248fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ma T, Thiagarajah JR, Yang H, Sonawane ND, Folli C, Galietta LJ, et al. Thiazolidinone CFTR inhibitor identified by high-throughput screening blocks cholera toxin-induced intestinal fluid secretion. J Clin Invest. 2002;110:1651–1658. doi: 10.1172/JCI16112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Muanprasat C, Sonawane ND, Salinas D, Taddei A, Galietta LJ, Verkman AS. Discovery of glycine hydrazide pore-occluding CFTR inhibitors: mechanism, structure-activity analysis, and in vivo efficacy. J Gen Physiol. 2004;124:125–137. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200409059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yan Z, Lei-Butters DC, Liu X, Zhang Y, Zhang L, Luo M, et al. Unique biologic properties of recombinant AAV1 transduction in polarized human airway epithelia. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:29684–29692. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M604099200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jiang Q, Engelhardt JF. Cellular heterogeneity of CFTR expression and function in the lung: implications for gene therapy of cystic fibrosis. Eur J Hum Genet. 1998;6:12–31. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejhg.5200158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Duan D, Yue Y, Yan Z, Yang J, Engelhardt JF. Endosomal processing limits gene transfer to polarized airway epithelia by adeno-associated virus. J Clin Invest. 2000;105:1573–1587. doi: 10.1172/JCI8317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hansen J, Qing K, Srivastava A. Adeno-associated virus type 2-mediated gene transfer: altered endocytic processing enhances transduction efficiency in murine fibroblasts. J Virol. 2001;75:4080–4090. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.9.4080-4090.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ding W, Yan Z, Zak R, Saavedra M, Rodman DM, Engelhardt JF. Second-strand genome conversion of adeno-associated virus type 2 (AAV-2) and AAV-5 is not rate limiting following apical infection of polarized human airway epithelia. J Virol. 2003;77:7361–7366. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.13.7361-7366.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhao W, Zhong L, Wu J, Chen L, Qing K, Weigel-Kelley KA, et al. Role of cellular FKBP52 protein in intracellular trafficking of recombinant adeno-associated virus 2 vectors. Virology. 2006;353:283–293. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2006.04.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wu Z, Miller E, Agbandje-McKenna M, Samulski RJ. Alpha2,3 and alpha2,6 N-linked sialic acids facilitate efficient binding and transduction by adeno-associated virus types 1 and 6. J Virol. 2006;80:9093–9103. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00895-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Summerford C, Samulski RJ. Membrane-associated heparan sulfate proteoglycan is a receptor for adeno-associated virus type 2 virions. J Virol. 1998;72:1438–1445. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.2.1438-1445.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Summerford C, Bartlett JS, Samulski RJ. AlphaVbeta5 integrin: a co-receptor for adeno-associated virus type 2 infection. Nat Med. 1999;5:78–82. doi: 10.1038/4768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Qing K, Mah C, Hansen J, Zhou S, Dwarki V, Srivastava A. Human fibroblast growth factor receptor 1 is a co-receptor for infection by adeno-associated virus 2. Nat Med. 1999;5:71–77. doi: 10.1038/4758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kashiwakura Y, Tamayose K, Iwabuchi K, Hirai Y, Shimada T, Matsumoto K, et al. Hepatocyte growth factor receptor is a coreceptor for adeno-associated virus type 2 infection. J Virol. 2005;79:609–614. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.1.609-614.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Walters RW, Yi SM, Keshavjee S, Brown KE, Welsh MJ, Chiorini JA, et al. Binding of adeno-associated virus type 5 to 2,3-linked sialic acid is required for gene transfer. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:20610–20616. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M101559200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Di Pasquale G, Davidson BL, Stein CS, Martins I, Scudiero D, Monks A, et al. Identification of PDGFR as a receptor for AAV-5 transduction. Nat Med. 2003;9:1306–1312. doi: 10.1038/nm929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Duan D, Yue Y, Engelhardt JF. Response to “polarity influences the efficiency of recombinant adeno-associated virus infection in differentiated airway epithelia. Hum Gene Ther. 1999;10:1553–1557. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Seiler MP, Miller AD, Zabner J, Halbert CL. Adeno-associated virus types 5 and 6 use distinct receptors for cell entry. Hum Gene Ther. 2006;17:10–19. doi: 10.1089/hum.2006.17.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ding W, Zhang LN, Yeaman C, Engelhardt JF. rAAV2 traffics through both the late and the recycling endosomes in a dose-dependent fashion. Mol Ther. 2006;13:671–682. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2005.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Liu X, Driskell RR, Engelhardt JF. Stem cells in the lung. Methods Enzymol. 2006;419:285–321. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(06)19012-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Karp PH, Moninger TO, Weber SP, Nesselhauf TS, Launspach JL, Zabner J, et al. An in vitro model of differentiated human airway epithelia. Methods for establishing primary cultures. Methods Mol Biol. 2002;188:115–137. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-185-X:115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]