Abstract

Background

Tamoxifen is widely prescribed for the treatment of breast cancer. Its success has been attributed to the modulation of the estrogen receptor. I have previously proposed that the release of arachidonic acid from cells may also mediate cancer prevention.

Methods

Rat liver cells were radiolabelled with arachidonic acid. The release of [3H] arachidonic acid after various times of incubation of the cells with tamoxifen was measured.

Results

Tamoxifen, at micromolar concentrations, stimulates arachidonic acid release. The stimulation is rapid and is not affected by pre-incubation of the cells with actinomycin or the estrogen antagonist ICI-182,780.

Conclusions

The stimulation of AA release by tamoxifen is not mediated by estrogen receptor occupancy and is non-genomic.

Background

Clinically, breast cancer chemoprevention by tamoxifen has been attributed to its antiestrogenic properties [1-3]. Tamoxifen also has been shown to prevent cancer in animal studies by a mechanism of action that is based, in part, on its antiestrogenic activity [1,4]. However, at μM levels, tamoxifen releases arachidonic acid (AA) from rat liver cells [5]. This ability to release AA, a molecule whose multiple bioactivities [6] include induction of apoptosis [7], suggests a mechanism for cancer prevention that does not require metabolism by cyclooxygenase [8]. I suggest that AA release from cells may be a part of a mechanism by which tamoxifen prevents cancer.

Tamoxifen has several biological effects, some of which may be beneficial. It also has unfavorable effects, especially its estrogenic activity on the uterus [1,2]. One of the many activities associated with perturbation of the plasma membrane and/or release of AA may mediate some of these biological effects.

Materials and Methods

The C-9 rat liver cell line was purchased from the American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA, USA). The cells were maintained in Eagle's minimum essential medium (MEM) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum. [3H] AA (91.8 Ci/mmol) was obtained from NEN Life Science Products, Inc. (Boston, MA, USA). ICI-182,780 was purchased from Tocris Cookson, Inc. (Ballwin, MO, USA). All other reagents were from Sigma Chemical Co. (St. Louis, MO, USA).

Two days prior to experiments, the rat liver cells were treated with 0.25% trypsin-EDTA and, after addition of minimal essential media (MEM) containing 10% fetal calf serum, the floating cells were seeded onto 35 mm culture dishes. The plating densities varied from 0.1 to 0.5 × 105 cells/35 mm dish. The freshly seeded cultures were incubated for 24-h to allow for cell attachment. After decantation of MEM containing the fetal bovine serum, 1.0 ml fresh MEM containing 10% fetal bovine serum and [3H] AA (0.2 μCi/ml) were added and the cells incubated for another 24-h. The cells were washed 4 times with MEM and incubated for various periods of time with 1.0 ml of MEM containing 1.0 mg BSA/ml and different concentrations of each compound. The culture fluids were then decanted, centrifuged at 2000 × g for 10 min, and 200 μl of the supernate counted for radioactivity. Radioactivity recovered in the washes before the 6-h incubation was compared to input radioactivity to calculate the % radioactivity incorporated into the cells [9]. For PGI2 production, 1.0 ml of MEM supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, void of [3H]AA, was added after the first 24-h incubation. The cells were incubated for another 24-h, washed three times with MEM, then incubated with lactacystin plus TPA and the compounds in MEM/BSA for various periods of time. The culture fluids were decanted and analyzed for 6-keto-PGF1α,the stable hydrolytic product of PGI2, by radioimmunoassay [10].

The [3H] AA release is presented as a percentage of the radioactivity incorporated by the cells. Except for the time-course experiments which used duplicate dishes. (Fig. 2), three to six culture dishes were used for each experimental point. The data are expressed as mean values ± SEM (number of dishes). The data were evaluated statistically by the unpaired Student's t-test. A P value < 0.05 was considered significant.

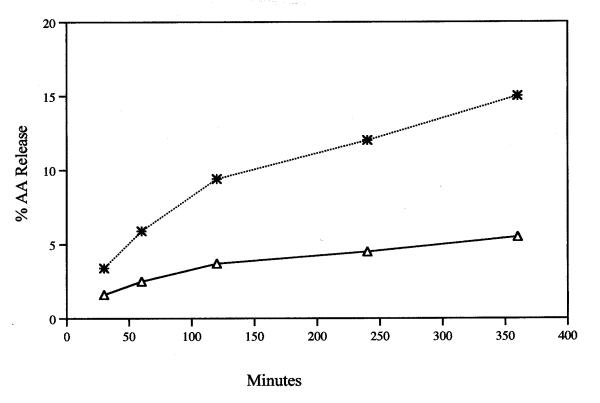

Figure 2.

Time course of release of AA during incubation with 12 μM tamoxifen (*) and MEM/BSA control (△). Analyses were performed on duplicate or triplicate dishes. The average value is recorded.

Results

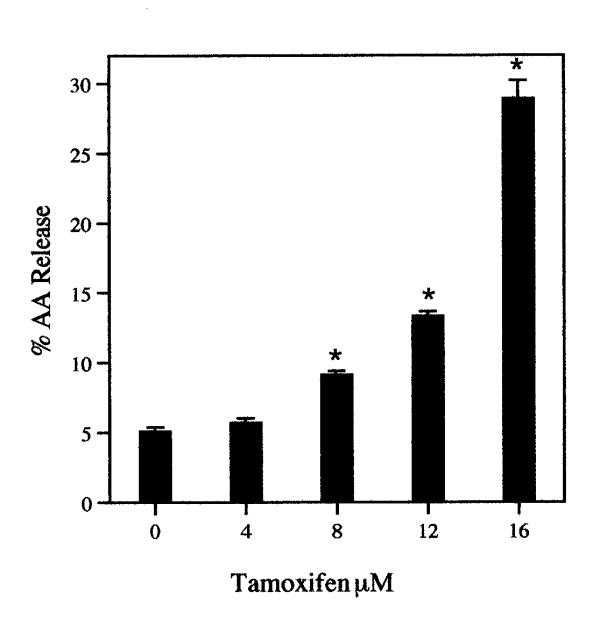

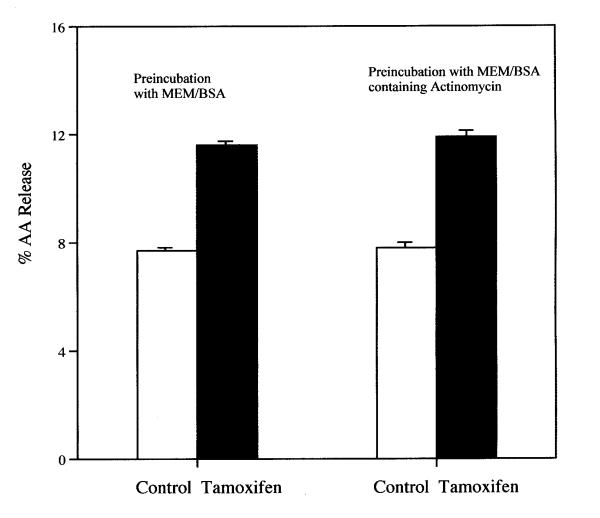

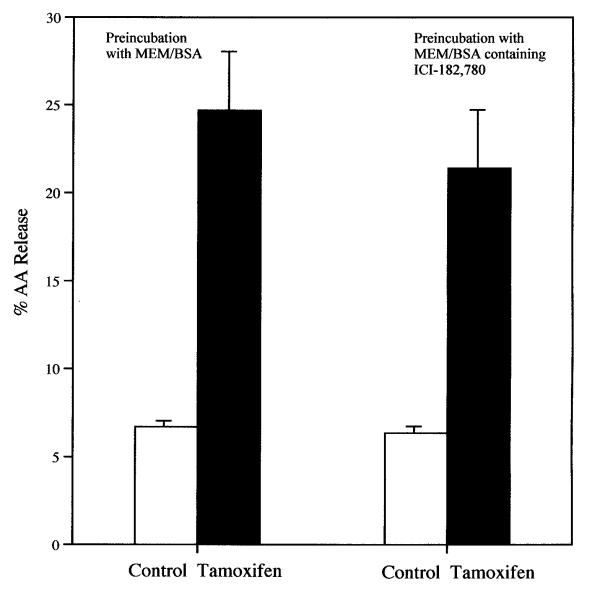

The release of AA from rat liver cells after a 6-h incubation with tamoxifen is dependent on the concentration of the drug (Fig. 1). Even at 8 μM, the stimulation of AA release is significant statistically. Tamoxifen (8 μM) also stimulates significantly AA release from rat glial cells (data not shown). After 30 min. incubation with 12 μM tamoxifen, AA release from rat liver cells is stimulated (Fig. 2). Even after a 5 min incubation, the AA release by 16 μM tamoxifen is stimulated significantly, 1.4 ± 0.06 (7) vs 1.6 ± 0.06 (7) % released in MEM/BSA and in the MEM/BSA containing the 16 μM tamoxifen respectively (P < 0.02). Tamoxifen (16 μM) also stimulates prostacyclin production. After a 6-h incubation, the stimulation of 6-keto-PGF1∝ production by 16 μM tamoxifen was 3.1 ± 0.18 fold when tested with cells ranging from the 19th to the 50th passage. The AA release by 8 μM tamoxifen after a 6-h incubation is not affected by pre-incubation of the cells for 2-h with 1 μM actinomycin (Fig. 3). Under these conditions, AA release and prostaglandin production induced by treatment of cells with lactacystin plus 12-0-tetradecanoyl-13-acetate or 15-deoxy-Δ12,14-PGJ2 are inhibited [11]. Pre-incubation of the cells with the estrogen antagonist ICI-182,780 (50 μM) [12]for 2-h does not significantly affect the stimulation of AA release by 16 μM tamoxifen (Fig. 4). ICI-182,780 (50 μM), however, did affect AA release stimulated by 17β-estradiol, 22(R)cholesterol, indomethacin, all-trans-retinoic acid and the tyrosine analog of thiazolidinedione, GW7845 [11].

Figure 1.

The dependence of AA release on tamoxifen concentration. The cells were incubated for 6-h. The analyses were performed with triplicate dishes. Each bar gives the mean value and the brackets give the SEM. * = statistically different vs control. These data are representative of several independent experiments with the same results.

Figure 3.

Effect of pre-incubation of cells with 1 μM actinomycin on the stimulation of AA release by tamoxifen. The cells were pre-incubated for 2-h in the presence of 1 μM actinomycin. During the 2-h pre-incubation, the % AA released by incubation with the control MEM/BSA and MEM/BSA containing actinomycin was 4.2 ± 0.21(4) and 4.3 ± 0.11(4) respectively. Each bar gives the mean value and the brackets give the SEM. (□) = MEM/BSA; (■) = MEM/BSA containing 8 μM tamoxifen. The data recorded are the sum of the AA released during the 2-h pre-incubation plus the average of the subsequent 6-h incubation. They are representative of three separate experiments with similar results.

Figure 4.

Effect of pre-incubation of cells with 50 μM of estrogen antagonist ICI-182,780 for 2-h on the stimulation of AA release by tamoxifen. The cells were pre-incubated for 2-h with 50 μM ICI-182,780. The data recorded are the sum of the AA released during the 2-h pre-incubation plus the average of the subsequent 6-h incubation. During the 2-h pre-incubation, 3.1 ± 0.02(4) and 2.6 ± 0.26(4) % AA was released by the control MEM/BSA and MEM/BSA containing ICI-182,780 respectively. (□) = MEM/BSA; (■) = MEM/BSA containing 16 μM tamoxifen. Each bar gives the mean value and the brackets give the SEM.

Discussion

Tamoxifen, in addition to its actions mediated by the estrogen receptor (ER), inhibits protein kinase C [13] and induces apoptosis in normal human mammary epithelial cells [14]. Submicromolar concentrations of tamoxifen or 4-hydroxytamoxifen induce apoptosis in ER-positive HeLa cells. However, both of these compounds, as well as estrogen, at concentrations of 10–20 μM, induce apoptosis in ER-negative HeLa cells [15]. The induction of apoptosis probably contributes to the effectiveness of tamoxifen in cancer prevention. AA, also induces apoptosis [8]. It has been suggested that cancer prevention by nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) is mediated by release of AA [8]. Several agents that prevent cancer, including retinoids, NSAIDs, vitamin D3 and some anti-oxidants, release AA from rat liver cells [5].

The AA release by tamoxifen and other reagents studied in my laboratory occurs with μM concentrations [5,9,11]. These experiments were carried out in the presence of BSA (1.0 mg/ml), and therefore do not differentiate between the protein-bound and free reagent. Thus, they are likely overestimated values. Nevertheless, the possibility that general necrotic cell death may cause AA release, must be considered. Lactacystin, (5.4 μM) phenylmethylsulphonyl flouride, (1 mM) carbobenzoxyleucylleucyleucinal, (1.0 μM) and carbobenzoxyleucylleucylnorvalinal (0.5 μM) were tested for rat liver cell viability by a tetrazolium-based assay. They were not toxic at these concentrations [16]. Proteosome inhibitors are not toxic to several other cells in culture [16]. No toxicity of tamoxifen, at concentrations of 10 to 20 μM for A549 human lung adenocarcinoma (ER-negative) cells was reported [17]; nor was 10 μM tamoxifen toxic when tested on rat glial cells and breast cancer MCF-7 cells [18]. Even when cell viability of three different breast cell lines (ER-positive MCF-7; ER-negative MDA-MB-239 and ER-negative BT-20 cells) was measured after incubation with 25 μM tamoxifen for 24-h, the loss in viability was due to apoptosis [19] and was not the result of necrotic cell death. Concentrations of tamoxifen used in this report are comparable to those found to induce apoptosis, not necrotic cell death. The median concentration of tamoxifen and its metabolites for clinical effectiveness in the treatment of breast cancer varies from 0.8 μM to 2.4 μM, depending on the age of the woman [20].

The stimulation of AA release by tamoxifen is non-transcriptional as indicated by the lack of inhibition by actinomycin (Fig. 3). The stimulation of AA release by tamoxifen also is not ER mediated as indicated by the lack of inhibition by the estrogen antagonist ICI-182,780 (Fig. 4). Tamoxifen at micromolar concentration may be intercalating into the lipid bilayer of the plasma membranes and affecting the fluidity and biochemical properties of the cell [21]. Another possibility is that tamoxifen is acting via G protein-coupled receptors [22,23].

Conclusions

Tamoxifen stimulates AA release from rat liver cells by a non-genomic, ER-independent pathway. In view of induction of apoptosis by AA, its release per se could, in addition to its effects on the ER, mediate cancer prevention.

Competing interests

None declared.

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

I thank Dr. Armen Tashjian Jr., Department of Cancer Cell Biology, Harvard School of Public Health, for the continued interest in these studies and Hilda B. Gjika for preparation of the manuscript.

References

- Jordan VC, Morrow M. Tamoxifen, raloxifene, and the prevention of breast cancer. Endocrin Rev. 1999;20:253–278. doi: 10.1210/er.20.3.253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacGregor JI, Jordan VC. Basic guide to the mechanisms of antiestrogen action. Pharmacol Rev. 1998;50:151–196. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katzenellenbogen BS, Katzenellenbogen JA. Defining the "S" in SERMs. Science. 2002;295:2380–2381. doi: 10.1126/science.1070442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gottardis MM, Jordan VC. Antitumor actions of keoxifene and tamoxifen in the N-nitrosomethylurea-induced rat mammary carcinoma model. Cancer Res. 1987;47:4020–4024. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levine L. Does the release of arachidonic acid from cells play a role in cancer chemoprevention? FASEB Journal. 2003;17:800–802. doi: 10.1096/fj.02-0906hyp. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brash AR. Arachidonic acid as a bioactive molecule. J Clin Invest. 2001;107:1339–1345. doi: 10.1172/JCI13210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Surette ME, Fonteh AN, Bernatchez C, Chilton FH. Perturbations in the control of cellular arachidonic acid levels block cell growth and induce apoptosis in HL-60 cells. Carcinogenesis. 1999;20:757–763. doi: 10.1093/carcin/20.5.757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan TA, Morin PJ, Vogelstein B, Kinzler KW. Mechanisms underlying nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drug-mediated apoptosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:681–686. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.2.681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levine L. Stimulated release of arachidonic acid from rat liver cells by celecoxib and indomethacin. Prostaglandins Leukot Essen Fatty Acids. 2001;65:31–35. doi: 10.1054/plef.2001.0284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levine L. Measurement of arachidonic acid metabolites by radioimmunoassay. In: Rose NR, Friedman H, Fahey JL, editor. Manual of Clinical Laboratory Immunology. 3. Washington DC: American Society for Microbiology; 1986. pp. 685–691. [Google Scholar]

- Levine L. Nuclear receptor agonists stimulate release of arachidonic acid from rat liver cells. Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids. 2002;67:453–459. doi: 10.1054/plef.2002.0456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wakeling AE. Use of pure antioestrogens to elucidate the mode of action of oestrogens. Biochem Pharmacol. 1995;49:1545–1549. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(94)00528-T. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Couldwell WT, Hinton DR, He S, Chen TC, Sebat I, Weiss MH, Law RE. Protein kinase C inhibitors induce apoptosis in human malignant glioma cell lines. FEBS Lett. 1994;345:43–46. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(94)00415-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dietze EC, Caldwell LE, Grupin SL, Mancini M, Seewaldt VL. Tamoxifen but not 4-hydroxytamoxifen initiate apoptosis in p53(-) normal human mammary epithelial cells by inducing mitochondrial depolarization. J Biol Chem. 2000;276:5384–5394. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M007915200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Obrero M, Yu DV, Shapiro DJ. Estrogen receptor-dependent and estrogen receptor-independent pathways for tamoxifen and 4-hydroxytamoxifen-induced programmed cell death. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:45695–45703. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M208092200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levine L. Proteolysis negatively regulates agonist-stimulated arachidonic acid metabolism. Cell Signal. 1998;10:653–659. doi: 10.1016/S0898-6568(98)00008-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Croxtall JD, Choudhury Q, White JO, Flower RJ. Tamoxifen inhibits the release of arachidonic acid stimulated by thapsigargin in estrogen receptor-negative A549 cells. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1997;1349:275–284. doi: 10.1016/S0005-2760(97)00143-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang W, Couldwell WT, Song H, Takano T, Lin JH, Nedergaard M. Tamoxifen-induced enhancement of calcium signaling in glioma and MCF-7 breast cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2000;60:5395–5400. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandlekar S, Yu R, Tan TH, Kong AN. Activation of caspase-3 and c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase-1 signaling pathways in tamoxifen-induced apoptosis of human breast cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2000;60:5995–6000. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peyrade F, Frenay M, Etienne MC, Ruch F, Guillemare C, Francois E, Namer M, Ferrero JM, Milano G. Age-related difference in tamoxifen disposition. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1996;59:401–410. doi: 10.1016/S0009-9236(96)90108-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whiting KP, Restall CJ, Brain PF. Steroid hormone-induced effects on membrane fluidity and their roles in non-genomic mechanisms. Life Sciences. 2000;67:743–757. doi: 10.1016/S0024-3205(00)00669-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cato ACB, Nestl A, Mink S. Rapid actions of steroid receptors in cellular signaling pathways. Sci STKE. 2002. Reg. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Hammes SR. The further redefining of steroid-mediated signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:2168–2170. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0530224100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]