Abstract

In non-excitable cells, receptor-activated Ca2+ signalling comprises initial transient responses followed by a Ca2+ entry-dependent sustained and/or oscillatory phase. Here, we describe the molecular mechanism underlying the second phase linked to signal amplification. An in vivo inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate (IP3) sensor revealed that in B lymphocytes, receptor-activated and store-operated Ca2+ entry greatly enhanced IP3 production, which terminated in phospholipase Cγ2 (PLCγ2)-deficient cells. Association between receptor-activated TRPC3 Ca2+ channels and PLCγ2, which cooperate in potentiating Ca2+ responses, was demonstrated by co-immunoprecipitation. PLCγ2-deficient cells displayed diminished Ca2+ entry-induced Ca2+ responses. However, this defect was canceled by suppressing IP3-induced Ca2+ release, implying that IP3 and IP3 receptors mediate the second Ca2+ phase. Furthermore, confocal visualization of PLCγ2 mutants demonstrated that Ca2+ entry evoked a C2 domain-mediated PLCγ2 translocation towards the plasma membrane in a lipase-independent manner to activate PLCγ2. Strikingly, Ca2+ entry-activated PLCγ2 maintained Ca2+ oscillation and extracellular signal-regulated kinase activation downstream of protein kinase C. We suggest that coupling of Ca2+ entry with PLCγ2 translocation and activation controls the amplification and co-ordination of receptor signalling.

Keywords: Ca2+ influx/C2 domain/PLCγ2/signal amplification/TRPC

Introduction

In non-excitable cells, stimulation of surface membrane receptors induces Ca2+ signals via activation of phospholipase C (PLC), which hydrolyses phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate (PIP2) into inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate (IP3) and diacylglycerol (DG) (Berridge, 1993; Clapham, 1995). IP3 triggers rapid Ca2+ release from internal Ca2+ stores of the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) by activating IP3 receptors (IP3R) and a consequent transient increase in cytosolic Ca2+ concentration ([Ca2+]i). The initial phase of receptor-activated Ca2+ signalling is followed by sustained and/or oscillatory [Ca2+]i changes. The molecular mechanism underlying the second phase is still elusive (Feske et al., 2001; Mori et al., 2002), despite the vital role played by this phase in various biological responses (Miyazaki et al., 1992; Thorn et al., 1993; Dolmetsch et al., 1998; Li et al., 1998).

The second phase of Ca2+ signalling is critically controlled by receptor-activated Ca2+ entry processes such as capacitative Ca2+ entry (CCE) mediated by store-operated Ca2+ channels (SOCs) coupled to IP3-induced Ca2+ release or consequent depletion of Ca2+ stores (Putney and Bird, 1993). In electrophysiological measurement, SOCs and other Ca2+ channels activated by DG in a membrane-delimited and protein kinase C (PKC)-independent manner have been identified (Hofmann et al., 1999; Okada et al., 1999; Inoue et al., 2001; Gamberucci et al., 2002). In [Ca2+]i measurement, it has been postulated that CCE is distinguished as an ‘off’ response elicited by readministration of extracellular Ca2+ to cells after pretreatment with store-depleting agents such as thapsigargin (TG) in the absence of Ca2+ (Parekh et al., 1997). Importantly, there is a large body of evidence that the properties of IP3R Ca2+ release channels affect the temporal patterns of Ca2+ signals/oscillations (Tsien and Tsien, 1990; Miyazaki et al., 1992; Miyakawa et al., 1999). Thus, together with direct elevation of [Ca2+]i by the Ca2+ entered through SOCs, the ‘capacitative’ function of CCE, which refills Ca2+ stores to maintain Ca2+ release, is a major role played by Ca2+ entry in eliciting the second phase.

In receptor-induced Ca2+ signalling, activation of PLC isoforms is controlled through distinct coupling mechanisms (Rhee, 2001). It has been commonly understood that receptor and non-receptor tyrosine kinases are responsible for activation of PLCγs. Recent evidence has added the novel view that PLCγs have multifunctional properties, and directly interact with numerous target proteins (Smith et al., 1994; Kim et al., 2000; Rebecchi and Pentyala, 2000; Rhee, 2001; Patterson et al., 2002; Putney, 2002; Runnels et al., 2002; Ye et al., 2002; Trebak et al., 2003). Here, we reveal that PLCγ2, beyond its role in initiating the Ca2+ response upon stimulation of tyrosine kinase-coupled receptors, mediates the second phase of Ca2+ signals in B lymphocytes. B cell receptor (BCR)-induced and store-operated Ca2+ entry elicited the translocation of PLCγ2 towards the plasma membrane in a lipase-independent manner, and enhanced PLCγ2 activation to maintain IP3 production and IP3-induced Ca2+ release. We suggest that Ca2+ entry is coupled with PLCγ2 translocation and activation to control physiological co-ordination and amplification of receptor-mediated signals.

Results

Activation of PLCγ2 by BCR-induced Ca2+ entry

In chicken DT40 B lymphocytes, ligation of BCR with anti-IgM antibody (anti-IgM) induced rapid rises in [Ca2+]i followed by sustained elevation of [Ca2+]i in the presence of extracellular Ca2+ (Figure 1A). Since the sustained phase was eliminated by omitting extracellular Ca2+, the sustained phase must derive from Ca2+ entry. Real time changes in [IP3]i were assessed in individual cells, using a new IP3-selective sensor R9-PHIP3-D106 constructed based on the pleckstrin homology (PH) domain of PLCδ1 (Morii et al., 2002). Stimulation of BCR triggered a rapid decrease in R9-PHIP3-D106 fluorescence, indicative of an initial [IP3]i increase in the wild-type (WT) cells (Figure 1B). The increase in [IP3]i was sustained or slowly enhanced for >5 min in the presence of extracellular Ca2+, but was transient when Ca2+ was removed. Population IP3 measurement confirmed the observation (Supplementary figure 1C, available at The EMBO Journal Online). Since PLCγ2 mediates BCR-induced Ca2+ signalling (Takata et al., 1995), the PLCγ2-deficient (PLCγ2–) DT40 cell line was employed to examine whether the observed IP3 production is in fact due to PLCγ2 activation. The BCR-induced [IP3]i and [Ca2+]i rises terminated in the PLCγ2– cells (Figure 1C and D). The defects were resolved by heterologous expression of rat PLCγ2 in the PLCγ2– cells, but not by a lipase-dead PLCγ2 mutant (LD; see also Figure 4A).

Fig. 1. Extracellular Ca2+ elicits sustained PLCγ2 activation and receptor-evoked [Ca2+]i mobilization. (A) Left, representative time courses of Ca2+ responses in DT40 cells upon BCR stimulation with anti-IgM (1 µg/ml) in 2 mM Ca2+-containing external (n = 32 cells) or EGTA-containing, Ca2+-free (n = 32) solution. Right, peak BCR-induced [Ca2+]i rises and [Ca2+]i increases sustained after 5 min stimulation. (B) Left, representative time courses of BCR-induced changes in florescence intensities of IP3 indicator R9-PHIP3-D106 (n = 12–15). F is the fluorescence intensity and F0 is the initial F. Right, BCR-induced [IP3]i changes at peak and sustained after 5 min. (C and D) BCR-induced [Ca2+]i rises (C) and [IP3]i rises (D) at peak and sustained after 6 min stimulation in WT cells expressing GFP (GFP/WT), and in PLCγ2– cells expressing GFP (GFP/PLCγ2–), PLCγ2 (PLCγ2/PLCγ2–) or LD mutant (LD/PLCγ2–) (n = 22–60). Ca2+ is present in external solution. (E) PLCγ2 enhances Ca2+ responses induced by Ca2+ entry upon M1R stimulation. Ca2+ release was first evoked in Ca2+-free solution, and Ca2+ entry-induced Ca2+ responses were induced by readministration of 2 mM Ca2+ in WT cells expressing GFP and in PLCγ2– cells expressing GFP, PLCγ2, LD or ΔSH3 (n = 5–13). Left, average time courses. Right, peak [Ca2+]i rises in Ca2+-free solution and after Ca2+ readministration. Significance difference from control: *P < 0.05.

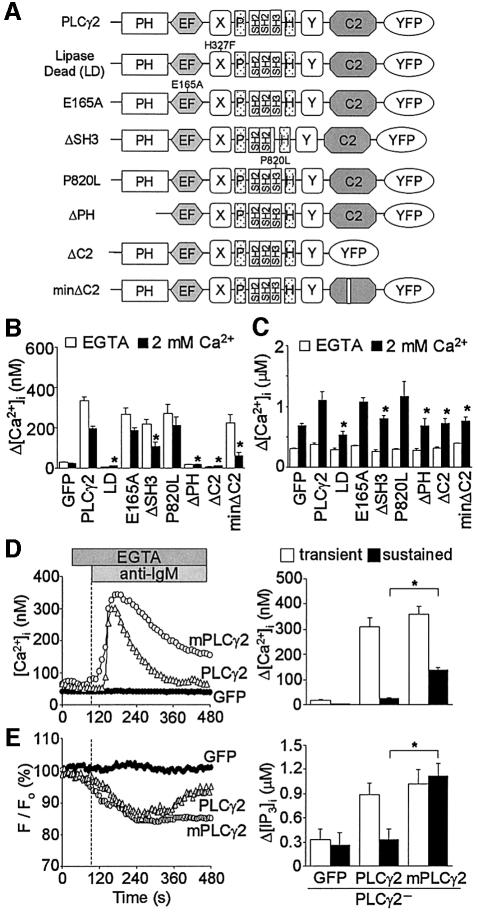

Fig. 4. The C2 domain mediates Ca2+ entry-induced activation of PLCγ2. (A) Schematic diagram for various mutant constructs of PLCγ2. (B) Peak BCR-induced [Ca2+]i rises during 5 min incubation in Ca2+-free solution and after subsequent readmission of Ca2+ in PLCγ2– cells expressing respective PLCγ2 mutants (n = 11–36). (C) Peak TG-induced [Ca2+]i rises in Ca2+-free solution and after readmission of Ca2+ in PLCγ2– cells expressing respective PLCγ2 mutants (n = 12–37). Protocol is the same as in Figure 2E. (D) Left, average time courses of BCR-induced Ca2+ responses in PLCγ2– cells expressing PLCγ2, membrane-bound PLCγ2 chimera (mPLCγ2) or GFP (n = 8–14). mPLCγ2 is composed of the human CD16 extracellular domain, the human TCR ζ-chain transmembrane domain and the complete rat PLCγ2 as a cytoplasmic domain (Ishiai et al., 1999). Right, BCR- induced [Ca2+]i rises at peak and sustained after 5 min. (E) Left, average time courses of BCR-induced F/F0 changes of R9-PHIP3-D106. Right, maximal [IP3]i elevation and sustained [IP3]i rises after 5 min upon BCR stimulation.

Ca2+ entry induced by G protein-coupled receptor stimulation activates PLCγ2

To characterize the extracellular Ca2+-dependent sustained phase separately from the initial BCR-evoked phase in PLCγ2 activation, heterologously expressed M1 muscarinic acetylcholine receptor (M1R) (Sugawara et al., 1997) was stimulated with carbachol (CCh). This is because the different isoform PLCβ mediates PIP2 hydrolysis to trigger Ca2+ release upon M1R and Gq protein activation (Parekh et al., 1997). In the WT and PLCγ2– cells, stimulation of M5R triggers Ca2+ mobilization via Gq and PLCβ (Patterson et al., 2002). Stimulation of M1R induced smaller [Ca2+]i increases in the PLCγ2– cells compared with those in the WT cells (Supplementary figure 2). However, omission of extracellular Ca2+ abolished the difference between the WT and PLCγ2– cells in M1R-activated Ca2+ responses (Figure 1E). The data support the view that PLCγ2 is responsible for external Ca2+-dependent enhancement of Ca2+ responses, and that Ca2+ entry induced by PLCβ-coupled receptor leads to late sustained PLCγ2 activation. Furthermore, the defect in Ca2+ entry-induced Ca2+ response in PLCγ2– cells was partially restored by the LD mutant in the PLCγ2– cells (Figure 1E), suggesting the lipase-independent (Patterson et al., 2002) and lipase-dependent roles of PLCγ2 in receptor-activated Ca2+ response.

Activation of PLCγ2 by store-operated Ca2+ influx

To analyse further the Ca2+ entry-induced mechanism in BCR-induced PLCγ2 activation, we used SERCA Ca2+-ATPase inhibitor TG, which activates SOCs via passive depletion of Ca2+ stores. In the presence of extracellular Ca2+, TG produced dramatic [Ca2+]i increases in the WT cells, but only moderate [Ca2+]i increases in the PLCγ2– cells (Figure 2A and B). In the absence of Ca2+, TG caused indistinguishable transient Ca2+ rises in the WT and PLCγ2– cells, indicating that TG-sensitive Ca2+ stores are not affected by the loss of PLCγ2. As shown in Figure 2C, treating the WT cells with TG induced marked [IP3]i rises in the presence of extracellular Ca2+, but elicited small [IP3]i rises in the absence of Ca2+. The [IP3]i increase induced by TG (1.43 ± 0.1 µM) was about half that induced by BCR (2.70 ± 0.3 µM) (Figure 2D). However, in the PLCγ2– cells, TG produced small [IP3]i increases, regardless of extracellular Ca2+ (Figure 2C and D). These results suggest that Ca2+ entry activated by TG-induced store depletion leads to IP3 production by PLCγ2.

Fig. 2. Store-operated Ca2+ entry induced by passive depletion of Ca2+ stores activates PLCγ2. (A) Average time courses of Ca2+-responses induced by TG (2 µM) in WT (left) and PLCγ2– (right) cells in Ca2+-free or Ca2+-containing external solution (n = 18–33). (B) Peak [Ca2+]i rises induced by TG in WT and PLCγ2– cells. (C) Typical time courses of TG-induced changes in F/F0 of R9-PHIP3-D106 in WT (left) and PLCγ2– cells (right) in the presence (top) or absence (bottom) of extracellular Ca2+ (n = 7–15). (D) Peak TG-induced [IP3]i rises. (E) Dependence of TG-induced ‘off’ Ca2+ responses on extracellular Ca2+ concentrations in WT and PLCγ2– cells. The ‘off’ responses were induced after 12.5 min exposure to TG in Ca2+-free solution (n = 34–53). Right, peak [Ca2+]i rises plotted against extracellular Ca2+ concentration.

In Figure 2E, the Ca2+ entry-evoked ‘off’ Ca2+ response was induced separately from the preceding passive Ca2+ release/depletion by TG (Parekh et al., 1997). In the physiological range of extracellular Ca2+ concentrations (1–10 mM), the Ca2+ entry-induced ‘off’ responses were significantly higher in the WT cells than those in the PLCγ2– cells. Replacing Ca2+ with Ba2+ failed to discriminate the ‘off’ responses between the WT and the PLCγ2– cells (Supplementary figure 3A), suggesting a specific positive role of Ca2+ in PLCγ2 activation or a lack of Ba2+ permeability of the Ca2+ entry channel. We also tested the possibility that the suppressed ‘off’ response in the PLCγ2– cells derives from a decrease in the electrical driving force for Ca2+ by membrane depolarization through cation channels such as TRPM7, which associates with PLCβ via the C2 domain (Runnels et al., 2002). In the solution containing K+ ionophore valinomycin, which maintains cell membrane potential at about –75 mV (Mori et al., 2002), and in the membrane-depolarizing high K+ (30 mM) solution, the ‘off’ [Ca2+]i increase remained significantly smaller in the PLCγ2– cells than in the WT cells (Supplementary figure 3B). Thus, the reduced ‘off’ response in the PLCγ2– cells was not due to membrane depolarization.

IP3-mediated Ca2+ release is involved inTG-induced ‘off’ Ca2+ responses

We next examined whether IP3R-mediated Ca2+ release is involved in TG-induced ‘off’ Ca2+ responses in DT40 B cells. Importantly, larger ‘off’ Ca2+ responses in the WT cells compared with those in the PLCγ2– cells were not observed after pretreatment with the IP3R antagonists, Xestospongin C (Xest C) (Figure 3A and B) and 2-aminoethoxydiphenyl borate (2-APB) (Supplementary figure 3C). The involvement of IP3-mediated Ca2+ release in the ‘off’ responses was confirmed by using ionomycin (IM), which depletes internal Ca2+ stores more indiscriminatingly and efficiently than TG, which selectively targets SERCA-containing stores (Supplementary figure 3D) (Parekh et al., 1997). The WT cells treated with IM showed greater Ca2+ release, but a smaller ‘off’ Ca2+ response compared with the WT cells treated with TG (Figure 3C). IM elicited nearly identical ‘off’ Ca2+ responses in the WT and the PLCγ2– cells, suggesting that thorough store depletion by IM nullified the contribution of IP3-induced Ca2+ release to the ‘off’ responses in the WT cells. Interestingly, IM elicited significant PLCγ2 translocation (Table I) and [IP3]i increase (1.55 ± 0.1 µM). In the cells deficient in three IP3R subtypes (IP3R-KO) (Sugawara et al., 1997), TG and IM induced nearly identical ‘off’ Ca2+ responses (Figure 3D). The data support the view that ‘off’ responses are promoted by IP3-induced Ca2+ release from Ca2+ stores, when Ca2+ stores are partially depleted (Supplementary figure 3D).

Fig. 3. Critical involvement of IP3-induced Ca2+ release in ‘off’ Ca2+ responses. (A and B) The IP3R blocker Xest C significantly suppresses TG-induced ‘off’ Ca2+ responses in WT (A) but not in PLCγ2– (B) cells (n = 23–48). Xest C (50 µM) was loaded with fura-2/AM using 0.1% Pluronic F-127 (Molecular Probes) for 30 min prior to [Ca2+]i measurements. During measurements, Xest C (50 µM) was added to perfusion solution for 20 min, and was omitted from Ca2+ readministration solution. Left, average time courses. Right, peak [Ca2+]i rises in Ca2+-free or Ca2+-containing external solution. (C) Left, average time courses of Ca2+ responses induced by TG and IM (1 µM) in WT and PLCγ2– cells (n = 16–33). Right, comparison between peak IM- and TG-induced [Ca2+]i rises in Ca2+-free or Ca2+-containing external solution. (D) Left, average time courses of Ca2+ responses induced by TG or IM in IP3R knockout cells. Right, peak IM- and TG-induced [Ca2+]i rises in Ca2+-free or Ca2+-containing solution.

Table I. Changes of PLCγ2 localization by BCR stimulation (% of total fluorescence).

| PLCγ2 mutant | Before BCR stimulation (membrane area) | 5 min after BCR stimulation (membrane area) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| WT | WT (2 mM Ca2+) | 37.0 ± 3.9 (n = 5) | 57.9 ± 2.3* |

| LD | 32.7 ± 2.7 (n = 3) | 53.4 ± 2.8* | |

| LD + U73122 | 30.1 ± 2.9 (n = 3) | 31.0 ± 5.0 | |

| LD (EGTA) | 35.0 ± 3.3 (n = 3) | 37.6 ± 4.6 | |

| ΔC2 | 26.9 ± 8.4 (n = 3) | 22.4 ± 5.1 | |

| minΔC2 | 33.3 ± 6.4 (n = 3) | 42.1 ± 5.9 | |

| ΔPH | 25.5 ± 4.2 (n = 3) | 24.5 ± 3.5 | |

| E165A | 31.8 ± 4.7 (n = 3) | 56.5 ± 2.9* | |

| P820L | 28.8 ± 3.1 (n = 3) | 46.5 ± 2.2* | |

| PLCγ2– | WT (2 mM Ca2+) | 33.8 ± 4.2 (n = 4) | 60.2 ± 9.3* |

| WT (EGTA) | 39.4 ± 5.7 (n = 5) | 37.3 ± 7.5 | |

| WT (2 mM Ba2+) | 35.7 ± 6.1 (n = 3) | 39.1 ± 2.3 | |

| WT + U73122 | 29.3 ± 7.9 (n = 3) | 35.0 ± 8.1 | |

| WT + U73343 | 31.2 ± 4.0 (n = 5) | 56.8 ± 3.5* | |

| LD | 31.7 ± 2.1 (n = 4) | 34.2 ± 1.9 | |

| ΔC2 | 34.7 ± 8.3 (n = 3) | 44.2 ± 3.8 | |

| minΔC2 | 36.7 ± 5.3 (n = 3) | 47.6 ± 7.7 | |

| ΔPH | 27.5 ± 4.8 (n = 3) | 30.2 ± 8.8 | |

| E165A | 29.4 ± 3.6 (n = 3) | 50.0 ± 5.3* | |

| P820L | 31.3 ± 5.4 (n = 3) | 60.4 ± 3.7* | |

| WT (ionomycin) | 38.4 ± 2.0 (n = 4) | 44.9 ± 2.1* |

Membrane regions of fluorescent areas in DT40 cells were as described in Figure 5A.

n, number of experiment. *P < 0.05, significantly different from cells before BCR stimulation.

Contrary to the above notion, the IP3R-KO cells showed TG-induced ‘off’ Ca2+ responses indistinguishable from those in the WT cells (Supplementary figure 4A). This discrepancy seems partly due to a compensatory enhancement in DG-sensitive Ca2+ channel expression; notable La3+-sensitive ‘off’ [Ca2+]i increases due to the DG analogue 1-oleoyl-2-acetyl-sn-glycerol (OAG, 30 µM) were observed in about half of the IP3R-KO cells (18/41) (Supplementary figure 4B), while fewer WT cells (15/50) showed small, transient OAG-induced ‘off’ responses. As reported previously (Venkatachalam et al., 2001), extracellular application of Ba2+ for Ca2+ elicited a tiny increase in the fluorescence ratio (data not shown), suggesting the importance of extracellular Ca2+ in differentiating WT cells from IP3R-KO cells in the OAG-induced ‘off’ response. Thus, TG-induced ‘off’ Ca2+ responses in IP3R-KO cells may result from store-operated Ca2+ entry and Ca2+ entry activated by DG via PLCγ2 activation, while the contribution of the latter pathway may be minor in WT cells.

C2 domain is responsible for Ca2+ influx-dependent activation of PLCγ2

The domains critical for Ca2+ entry-dependent activation were determined in PLCγ2. Three potential Ca2+-binding domains (EF-hand, catalytic domain and C2 domain), and the PH and SH3 domains are distinguished in PLCγ2 (Bairoch et al., 1990; Essen et al., 1996; Rhee, 2001; Ananthanarayanan et al., 2002). In PLCγ1, PH mediates membrane-targeting through phosphatidylinositol 3,4,5-trisphosphate (PIP3) binding, while SH3 acts as a physiological guanine nucleotide exchange factor (GEF) for the nuclear GTPase PIKE, an activator of nuclear phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K) (Ye et al., 2002) that produces the PIP3 required for BCR-induced [Ca2+]i elevation (Falasca et al., 1998). Mutations were introduced in the PLCγ2 domains tagged with yellow fluorescent protein (YFP) (Figure 4A). As expected, expression of the LD mutant in PLCγ2– cells failed to restore either the BCR-induced [Ca2+]i increase or to potentiate a TG-induced ‘off’ Ca2+ response (Figure 4B and C). Strikingly, deletion of C2 domain (ΔC2), which is involved in the formation of the Ca2+-phospholipid ternary complex in PLCδs (Ananthanarayanan et al., 2002), ablated the PLCγ2 function to restore the BCR- and TG-induced Ca2+ responses. Deleting one of the expected Ca2+ binding regions (Δ1138E-1140D) (Essen et al., 1996) in C2 (minΔC2) similarly blocked the restoration of the ‘off’ responses but not that of the BCR-induced Ca2+ release, strikingly differentiating Ca2+ entry-mediated responses from Ca2+ release. The PH deletion mutant (ΔPH) also failed to restore the PLCγ2– deficiency, as reported in PLCγ1 activation (Falasca et al., 1998). In contrast, the SH3 deletion (ΔSH3) mutant elicited partially impaired the Ca2+ responses, and the point SH3 mutant with leucine at proline 820 (P820L) that corresponds to P842 essential for GEF activity in PLCγ1 (Ye et al., 2002), or the EF-hand mutant (E165A), behaved like WT. Thus, the C2 domain is critical for Ca2+ entry-dependent activation of PLCγ2.

C2 domain mediates Ca2+ influx-dependent translocation of PLCγ2

The above data and the requirement for C2 when various proteins target the plasma membrane (Sutton et al., 1995; Ananthanarayanan et al., 2002; Delmas et al., 2002) motivated us to visualize the localization of YFP-tagged PLCγ2 (Figure 5). Transfected PLCγ2 was diffusively distributed in the cytosol from the perinuclear area to the plasma membrane of the WT and the PLCγ2– cells. Within 4 min, but not within 2 min, stimulation of BCR efficiently concentrated PLCγ2 near the plasma membrane in the presence of extracellular Ca2+ (Figure 5A). This PLCγ2 translocation was abolished by removing Ca2+, using Ba2+ for Ca2+, using ΔC2 and minΔC2 in the WT and the PLCγ2– cells (Figure 5A and B; Table I). ΔPH also suppressed translocation. The EF and SH3 mutants showed significant translocation (Table I). Importantly, even in the absence of extracellular Ca2+, expression of membrane-bound PLCγ2 (mPLCγ2) (Ishiai et al., 1999) in the PLCγ2– cells promoted sustained [IP3]i and [Ca2+]i increases (Figure 4D and E). Thus, C2 mediates the Ca2+ entry-induced transportation of PLCγ2 for subsequent activation. Furthermore, in the WT cells, but not in the PLCγ2– cells, the LD mutant of PLCγ2 showed significant BCR-induced plasma membrane localization inhibited by the PLC blocker, U73122 (Figure 5C). This suggests that transfected PLCγ2 does not require its own lipase activity for Ca2+ entry-induced translocation to the plasma membrane when endogenous lipase-active PLCγ2 is present.

Fig. 5. Ca2+ influx induces translocation of PLCγ2 via the C2 domain. (A) Confocal fluorescence images indicating BCR-induced changes of subcellular localization of YFP-tagged PLCγ2 in PLCγ2– cells in Ca2+-containing or Ca2+-free solution (n = 5). Right, representative fluorescent changes of PLCγ2–EYFP distributed in 1 µm widths peripheral regions (Mem.) and in the rest the cytosolic areas (Cyt.). (B) Confocal images indicating changes of localization of PLCγ2 constructs (WT, LD, ΔC2 or ΔPH) in WT and PLCγ2– cells by 5 min BCR stimulation (n = 5). (C) PLC inhibitor U73122 blocks BCR-induced localization changes of LD in WT cells. Treatment with U73122 (3 µM) or its inactive analogue U73343 was started 20 min prior to BCR stimulation. Lower left, average time courses of BCR-induced F/F0 changes of R9-PHIP3-D106 in WT cells expressing GFP or LD, or pretreated with U73122 or U73343. Lower right, maximal [IP3]i elevation upon BCR stimulation.

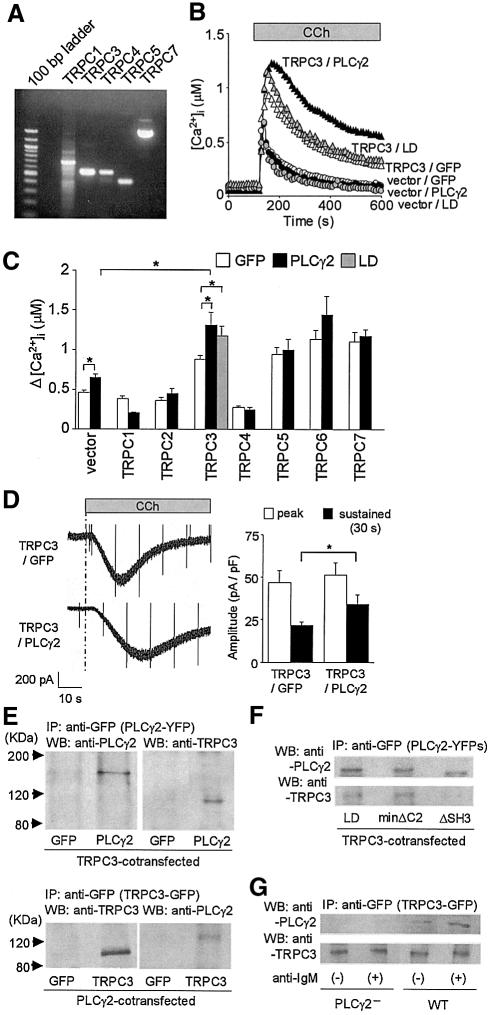

Functional and physical association of PLCγ2 with TRPC3

Among the TRPC channels responsible for receptor-activated Ca2+ entry (Montell et al., 2002), expression of TRPC1, C3, C4, C5 and C7 was identified in DT40 cells (Figure 6A). The respective TRPC channels were tested for functional coupling with PLCγ2 by co-expressing PLCγ2 in HEK cells. Upon stimulation of the endogenous muscarinic acetylcholine receptors (MRs) with CCh, TRPC3, C5, C6 and C7 alone promoted increased [Ca2+]i (Figure 6C), while co-expression of PLCγ2 exerted further potentiation only in the TRPC3-expressing cells (Figure 6B and C). LD elicited the intact potentiation of peak Ca2+ responses but failed to sustain Ca2+ response. In the patch-clamp recording, PLCγ2 significantly sustained CCh-activated TRPC3 currents (Figure 6D). Upon MR stimulation, PLCγ2–YFP fluorescence near the plasma membrane showed increases that indicate translocation in TRPC3-expressing cells (47.8 ± 0.7 to 52.3 ± 0.3%, P < 0.05). Furthermore, immumoprecipitation analysis revealed a physical association between PLCγ2 and TRPC3 (Figure 6E), which was impaired by ΔSH3, but not by LD or minΔC2 (Figure 6F), in the HEK cells. In the DT40 cells, co-immunoprecipitation of TRPC3 with PLCγ2 enhanced by BCR stimulation was observed (Figure 6G). These results suggest that receptor-activated TRPC3 channels functionally and physically interact with PLCγ2 via SH3 to enhance Ca2+ response and to maintain their own channel activity.

Fig. 6. Functional and physical association of PLCγ2 with the TRPC3 Ca2+ channel promotes receptor-evoked TRPC3 currents and Ca2+ responses. (A) RT–PCR analysis of RNA expression of TRPC homologues in DT40 cells. (B) Average time courses of Ca2+ responses upon stimulation of MRs in HEK cells expressing TRPC3 and/or PLCγ2 (WT or LD) (n = 32–38). (C) Peak MR-activated [Ca2+]i rises in HEK cells expressing respective TRPC1–C7 channels alone or along with PLCγ2. (D) Left, representative traces of ionic currents recorded from cells expressing TRPC3 alone or plus PLCγ2 at a holding potential of –60 mV. Right, peak and sustained (30 s after reaching peak) amplitudes of the MR-activated TRPC3 currents (n = 9–10). (E) Co-immunoprecipitation of TRPC3 and PLCγ2 via SH3. Immunoprecipitates (IP) with anti-GFP polyclonal antibody from TRPC3/GFP- and TRPC3/PLCγ2–YFP-expressing HEK cells (upper) or GFP/PLCγ2- and TRPC3–GFP/PLCγ2-expressing HEK cells (lower) were separated on 8% SDS-PAGE, and blotted with anti-PLCγ2 or anti-TRPC3 antibody, respectively, in western blot analysis (WB). (F) IP with the anti-GFP antibody from LD/TRPC3-, minΔC2/TRPC3- and ΔSH3/TRPC3-expressing HEK cells. Anti-TRPC3 antibody was used to assess co-immunoprecipitation in WB. All the PLCγ2 constructs were tagged with YFP. (G) IP with the anti-GFP antibody from TRPC3-GFP-expressing WT and TRPC3–GFP-expressing PLCγ2– cells with (+) or without (–) 5 min BCR stimulation (anti-IgM). Co-immunoprecipitation was assessed using anti-PLCγ2 antibody in WB.

Critical involvement of Ca2+ entry-dependent PLCγ2 activation in receptor-evoked Ca2+ oscillation

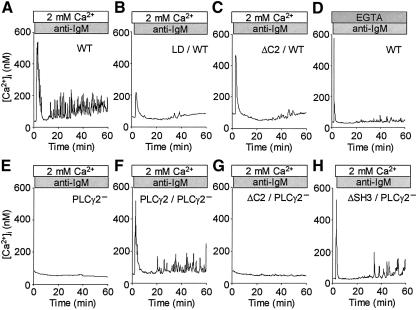

Periodic increases in [Ca2+]i (Ca2+ oscillation) are important for the efficiency and specificity of gene expression in lymphocytes (Dolmetsch et al., 1998) and other biological responses (Miyazaki et al., 1992; Thorn et al., 1993). Figure 7A depicts a typical Ca2+ oscillation induced by stimulation of BCR in DT40 cells. LD and ΔC2 expression almost eliminated the late oscillatory phase of the BCR-induced Ca2+ response in the WT cells, while they only elicited partial suppression of the initial transient Ca2+ response (Figure 7B and C). Considering the translocation of LD to the plasma membrane in the WT cells (Figure 5B), this evidence supports the view that lipase activity is essential for the translocated PLCγ2 in maintaining downstream Ca2+ oscillation. The expression of PLCγ2 restored Ca2+ oscillation in the PLCγ2– cells (Figure 7F). However, ΔSH3 incompletely restored Ca2+ oscillation, and ΔC2 failed to elicit a detectable Ca2+ response in the PLCγ2– cells (Figure 7G and H). The results demonstrate the physiological significance of Ca2+ influx-dependent PLCγ2 activation in BCR-induced Ca2+ oscillation.

Fig. 7. PLCγ2 requires its lipase activity and C2 domain to elicit BCR-evoked Ca2+ oscillation. (A–D) Representative time courses of BCR-induced Ca2+ responses in WT and PLCγ2– cells in Ca2+-containing (A–C and E–H) (n = 16–72) or Ca2+-free (D) (n = 50) solution (long time course, 60 min). PLCγ2 constructs were the same as those in Figure 4.

Amplification of DG signalling promotes ERK activation

The PLCγ2-mediated signal amplification should have a significant impact on the responses downstream of DG, since DG production is also enhanced by Ca2+ entry-induced PLCγ2 activation and PIP2 hydrolysis. Activation of PKC by DG promotes activation of extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) through phosphorylation in DT40 cells (Kurosaki, 2002). Figure 8A depicts sustained BCR-induced ERK activation in an extracellular Ca2+-dependent manner. The ERK activation was inhibited by a PKC inhibitor, bisindolylmaleimide (BIM, 10 µM), and more prominently by PLCγ2 deficiency, which was partially reversed by a PKC activator phorbol-12-myristrate-13-acetate (PMA) (Figure 8B). Hence, signal cascades other than PKC activation may be evoked by PLCγ2 to activate ERK. Furthermore, TG gradually increased the phosphorylated levels of ERK in an extracellular Ca2+- and PLCγ2-dependent manner (Figure 8C and D). Thus, Ca2+ entry-dependent PLCγ2 activation is important in DG-induced activation via PKC of ERK in mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathways.

Fig. 8. Requirement of Ca2+ influx-dependent PLCγ2 activation for sustained BCR-induced activation of ERK in DT40. (A) WT or (B) PLCγ2– cells were stimulated with anti-IgM (1 µg/ml) for indicated time in the presence or absence of extracellular Ca2+. Treatment with BIM (10 µM) was started 10 min before BCR stimulation. PMA (50 nM) was applied to anti-IgM in PLCγ2– cells (B). (C and D) Average time courses of ERK activation evoked by TG (2 µM) in WT (C) and PLCγ2– (D) cells. The ERK activities were assessed by the quantification of its phosphorylation using phospho-specific antibody.

Discussion

Ca2+ entry amplifies BCR-induced Ca2+ signalling via PLCγ2 translocation and activation

This study reveals a novel molecular mechanism that amplifies cellular signals in the second phase of the Ca2+ response in B lymphocytes. The amplification mechanism is a positive feedback cycle, in which a key event is the Ca2+ entry-evoked translocation towards the plasma membrane and the subsequent PLCγ2 activation/IP3 production then leads to Ca2+ release and entry (Figure 9). The C2 domain mediates the translocation of PLCγ2 (Figure 5B). Importantly, C2 is also found in PLCδ (Ananthanarayanan et al., 2002), phospholipase A2 (PLA2) (Clark et al., 1991), synaptotagmin I (Sutton et al., 1995) and PKC isoforms (Schaefer et al., 2001; Delmas et al., 2002), among which PLA2 and PKCs are translocated by Ca2+ entry (Clark et al., 1991; Schaefer et al., 2001). For targeting membrane microdomains and activating PLCγ2, its PH domain is essential (Figure 5B). PIP3 by PI3K is required for receptor-stimulated Ca2+ mobilization (Bae et al., 1998), and PIP3 binds to the PH with the highest affinity among the phosphoinositides to activate PLCγ1 through membrane targeting (Falasca et al., 1998). In fact, our data demonstrate that the ΔPH mutant failed to restore the Ca2+ responses (Figure 4B and C), and that wortmannin (1 µM), which suppresses PIP2 and PIP3 synthesis by inhibiting PI3K and PI4K, significantly suppressed BCR-stimulated Ca2+ oscillation, and attenuated the TG-induced [Ca2+]i increase in the WT cells, but not in the PLCγ2– cells (Supplementary figure 5).

Fig. 9. Model for amplification of Ca2+ signalling by PLCγ2 in B lymphocytes. BCR stimulation induces activation of PLCγ2 via phosphorylation by Syk tyrosine kinase, and the activated PLCγ2 hydrolyses PIP2 to produce IP3. IP3 leads to Ca2+ release from ER and Ca2+ influx via TRPC3-containing receptor-activated Ca2+ channels (RACCs), which may correspond to SOCs activated through interaction with IP3R or to DG-activated Ca2+ channels. Ca2+ influx via RACC promotes lipase-independent PLCγ2 translocation from the cytosol to the plasma membrane (PM) by acting on the C2 domain. The targeted PLCγ2 is activated to hydrolyse PIP2 and produce IP3 and DG, which in turn induces Ca2+ release from ER and Ca2+ influx via Ca2+ entry channels such as TRPC3. PLCγ2 may also positively regulate TRPC3 channels via direct interaction.

The second key process in the amplification mechanism is successive Ca2+ release. We observed a striking difference in the ‘off’ response between the WT and the PLCγ2– cells (Figure 3C) when TG was used to selectively deplete SERCA-containing stores, but not when IM was employed for more indiscriminate and thorough store depletion. This suggests that IP3-induced Ca2+ release from partially depleted stores significantly contributes to the TG-induced ‘off’ response, being consistent with the previous report in which TG frequently failed to induce Ca2+ release-activated Ca2+ currents in patch-clamp recording despite its efficiency in inducing ‘off’ responses in [Ca2+]i measurement (Parekh et al., 1997). Efficient activation of Ca2+ entry channels via IP3-induced store depletion (Zhu et al., 1996) following PLCγ2 activation is the third key process. This process may be elicited from the physical association of TRPC3 with PLCγ2 and IP3Rs (Boulay et al., 1999; Kiselyov et al., 1999) (Figure 6E). Activation of type 3 IP3R in the plasma membrane (Vazquez et al., 2002) and direct DG action on Ca2+ channels (Hofmann et al., 1999; Trebak et al., 2003) are also important processes to be considered. Ultimately, determinating the composition of the signalplex that contains PLCγ2, TRPC3 and other proteins such as BLNK (Ishiai et al., 1999) is essential for fundamental understanding of the amplification mechanism.

The transfected LD PLCγ2 mutant was translocated to the plasma membrane area in the WT cells, but not in the PLCγ2– cells (Figure 5B). This result suggests that Ca2+ influx is mediated by endogenous PLCγ2 to elicit subsequent translocation of LD in WT cells, and that PLCγ2 does not require its own lipase activity in the translocation process. Independent of the hydrolysis of PIP2, the translocated PLCγ2 may exert positive regulatory action on TRPC3 Ca2+ channel activity at the plasma membrane through physical interaction via SH3 (Figure 6) (Patterson et al., 2002). It is also possible that PLCγ2 translocation is accompanied by associated TRPC3 targeting the plasma membrane (Figure 9). In fact, on M1R stimulation, we observed partial but significant restoration of Ca2+ entry-induced [Ca2+]i elevation by the ΔSH3 mutant in the PLCγ2– cells (Figure 1E). Thus, the enzyme activity-independent translocation and consequent interaction of PLCγ2 with TRPC3 at the plasma membrane may underlie a non-enzymatic role of PLCγ2 (Patterson et al., 2002; Putney, 2002), cooperating with the second lipase activation in enhancing Ca2+ entry to fully restore the Ca2+ deficiency in mutant cells. This view is consistent with a recent report by Patterson et al. (2002) in which LD restored Ca2+ entry-induced [Ca2+]i increases in M5R-stimulated PLCγ2– cells, although the restoration was comparable to that by WT. The difference in peak responses between our data using M1R and the data of Patterson et al. (2002) using M5R is attributable to different activation and/or desensitization speeds of receptor-activated Ca2+ entry and subsequent lipase activity-dependent PLCγ2 signalling, considering smaller Ca2+ release but larger Ca2+ entry-induced Ca2+ response upon M1R stimulation (Figure 1E) compared with that upon M5R stimulation. The slower signal transduction through PLCγ2 may result in the Ca2+ entry and lipase activity-dependent response that persisted throughout the protocol (Figure 1E), in contrast to the almost complete suppression of Ca2+ entry and absence of lipase activity-dependent response in the M5R-expressing PLCγ2-deficient cells (Figure 6 of Patterson et al., 2002). Since deleting SH3 also terminated the enhancing effect of PLCγ1 on the Ca2+ entry-induced Ca2+ responses in the PC12 cells and the TRPC3-expressing HEK cells (Patterson et al., 2002), PLCγ1 and PLCγ2 may share an enzyme-independent function in receptor-induced Ca2+ responses.

Physiological impact of Ca2+ entry-induced PLCγ2 activation in BCR signalling

Our finding is contrary to the prevailing view that receptor-activated Ca2+ entry channels amplify Ca2+ responses predominantly through the direct effect of Ca2+ permeation and replenishing Ca2+ stores. The PLCγ2-mediated amplification of the Ca2+ signal would therefore dramatically change the view of the physiological roles played by receptor-activated Ca2+ entry. The PLCγ2-mediated signal amplification should have a significant eventual impact on downstream Ca2+-dependent responses, including regulation of gene expression via transcription factors such as NF-AT (Dolmetsch et al., 1998), cell proliferation and apoptosis (Verkhratsky and Petersen, 2002; Irvine, 2002). Importantly, PIP2 hydrolysis and DG production are also enhanced in the amplification mechanism. Activation of PKC by DG promotes ERK activity in the MAPK pathway to induce phosphorylation of the transcription factor CREB, which interacts with an enhancer cAMP-response element (Kurosaki, 2002). Our results provide direct evidence that ERK activation is promoted by Ca2+ entry via PLCγ2 and PKC. DG is also known to activate the TRPC3, C6 and C7 channels in a PKC-independent manner (Hofmann et al., 1999; Okada et al., 1999; Trebak et al., 2003), while PIP2 is linked to the pathway composed of PI3K, Bruton’s tyrosine kinase and the serine threonine kinase Akt/PKB (Kurosaki, 2002). Hence, the model predicts extensive regulatory roles of Ca2+ entry-induced PLCγ2 activation in the amplification and/or co-ordination of multiple BCR-induced signalling pathways.

PLCγ2 is also expressed in the anterior pituitary and cerebellar Purkinje and granule cells (Rebecchi and Pentyala, 2000). Previously, regarding Ca2+ oscillation in REF52 fibroblasts, Harootunian et al. (1991) proposed that a dominant feedback mechanism is the stimulation of PLC by the [Ca2+]i increase through population IP3 measurement, while pathways that evoke the [Ca2+]i increase remained unidentified. Recent research has also demonstrated production of IP3 induced by voltage-dependent Ca2+ influx (Okubo et al., 2001) and regulation of metabotropic glutamate receptor-mediated neuronal signalling by extracellular Ca2+ in Purkinje neurons (Tabata et al., 2002). When eggs are fertilized by sperm, the Ca2+ oscillations essential for embryo development are mediated by PLCγ (Sato et al., 2000) or homologous PLCζ (Saunders et al., 2002). Furthermore, the activation of recombinantly overexpressed PLCδ1 by Ca2+ entry that follows the PLCβ activation upon bradykinin stimulation has been reported in PC12 cells (Kim et al., 1999). Since the ubiquitous PLCγ1 and PLCδ also contain C2 domains (Rebecchi and Pentyala, 2000), the signal amplification mediated by Ca2+ entry-induced PLC translocation and activation may be universal among various cell types.

Materials and methods

Cell cultures and cDNA expression

The PLCγ2 mutants were constructed using PCR techniques. The WT PLCγ2 (Takata et al., 1995), LD (H327F) (Patterson et al., 2002) and other mutated constructs were fused at the C-terminus with YFP using an EYFP-N1 vector (Clontech). In the ΔC2, ΔPH and ΔSH3 mutants, residues 1043M-1237V, 20R-131Q and 810D-829A were deleted, respectively. Cell cultures and cDNA expression in the DT40 cells using the vesicular somatitis virus and in the HEK293 cells were performed as described previously (Hara et al., 2002; Mori et al., 2002).

Measurement of changes in [Ca2+]i

The cells on coverslips were loaded with 1 µM fura-2/AM in a physiological salt solution (PSS) containing (in mM): 150 NaCl, 8 KCl, 2 CaCl2, 1 MgCl2, 5 HEPES, and 5.6 glucose, adjusted to pH 7.4 with NaOH. Fluorescence images of the cells were recorded and analysed with a video image analysis system (ARGUS CA-20; Hamamatsu Photonics) as described previously (Mori et al., 2002). All ratio data were calculated to [Ca2+]i using an in vivo calibration method.

Fluorometric measurement of changes in [IP3]i

The basic strategy in designing the optical direct IP3 sensors is described in Morii et al. (2002). Conjugation with fluorophore 6-bromoacetyl-2-dimetyl-aminonaphtalene (DAN) at Cys106 introduced near the mouth of the IP3-binding site prevents semi-specific ligand binding (Morii et al., 2002), conferring an IP3-selective sensitivity to the PH protein. The dissociation constant was only slightly affected by Ca2+ and ranged from 2.2 to 3.3 µM in 0–1 mM Ca2+. The protein was further fused to arginine (Arg) nonapeptide for improved cellular incorporation. The modified sensor, R9-PHIP3-D106 [Arg (R)9-PH IP3 sensor conjugated with DAN at residue 106), showed an efficient in vivo IP3-sensing ability. In in vivo measurements, cells were plated onto poly-l-lysine-coated glass coverslips. After a 2 h incubation for cell adhesion, the cells were transferred to Hank’s balanced salt (HBS) solution containing 1 µM of IP3 sensor and 0.1% F-127 (Molecular Probes) for 10 min at 37°C. After the cells were washed, changes in the fluorescence images of the cells were observed using a video image analysis system at an emission wavelength of 510 nm (bandwidth 20 nm) at room temperature by excitation at 380 nm (bandwidth 11 nm) in PSS. [IP3]i increases were detected as fluorescence quenching of R9-PHIP3-D106 due to IP3 binding. All traces were displayed after subtracting the averaged time courses of fluorescence reduction due to photobleaching or photodegradation.

For the in vivo calibration of [IP3]i, synthesized IP3 (Dojindo) was applied to R9-PHIP3-D106-preloaded DT40 cells after treatment with β-escin (1 µM; Sigma) (Supplementary figure 1). The initial decrease in fluorescence was fitted to a binding isotherm:

ΔF = ΔFmax {[IP3]/(Kd + [IP3])} (1)

where ΔF is the change in fluorescence intensity. ΔFmax is ΔF at saturation, Kd is the dissociation constant, and [IP3] is the concentration of IP3. [IP3]i was calculated based on Equation 1, where the Kd value is 1.24 µM.

Electrophysiology

The whole-cell patch–clamp technique was performed as described previously (Mori et al., 2002). The cells on coverslips were perfused in an external solution containing in (mM): 140 NaCl, 5 KCl, 2 CaCl2, 1 MgCl2, 10 HEPES, and 10 glucose, adjusted to pH 7.4 with NaOH (300 mOsm). The pipette solution contained in (mM): 75 CsOH, 75 asparate, 40 CsCl, 4 MgCl2, 10 BAPTA, 2 ATP Na2, 5 HEPES, and 8 phosphocreatine, adjusted to pH 7.4 with CsOH. mTRPC3-pCIneo (Okada et al., 1999) was co-transfected with pIRES2-EGFP (Clontech) or pIRES2-EGFP that contained PLCγ2 cDNA in the HEK cells, and GFP-positive cells were selected for recording.

Confocal visualization of PLCγ2–YFP fusion constructs

PLCγ2–YFP-expressing cells were plated onto poly-l-lysine coated glass coverslips after 72 h of retroviral infection. Fluorescence images were acquired with a confocal laser-scanning microscope (FV500; Olympus) using the 488 nm line of an argon laser for excitation and a 505 nm long-pass filter for emission. The specimens were viewed at high magnification using plan oil objectives (60×, 1, 40 NA; Olympus).

Expression analysis

The PCR protocol used for the expression analysis is as described previously (Inoue et al., 2001). The PCR primers used are listed in Table II.

Table II. Sequences of antisense and sense oligonucleotides used.

| Gene | Orientation | Pair of primers for first PCR (5′ to 3′) | Pair of primers for nested PCR (5′ to 3′) |

|---|---|---|---|

| TRPC1 | Sense | TGGATTATTGGGATGATTTGGTCAGAC | |

| Antisense | TCGGGCGAATTTCCATTCCTTATCTTC | ||

| TRPC3 | Sense | GTCTGAAGTAACCTCTGTGTCCTG | GAGAACATGGATATGTTCTCTATGGC |

| Antisense | CACATCTCAACATATTGGGATTGAG | ATGGCTAACTCTTCTGTCGCCTGGGAC | |

| TRPC4 | Sense | GAGCTGGGACATGTGGCATCCAACGC | GAGGCACTGTTTGCAATTGCAAACATC |

| Antisense | GCACAAGGTGTCTCCATTATCCACC | GCTTGGTATGACATTGAAAGGAGTGGGC | |

| TRPC5 | Sense | TTGAGGTCTTCTGAAGGACCACGCAG | CTGCAAGTGGATTCACAATCAGCTGTGC |

| Antisense | GGCTTCTCTTCCGCCATGTCAATCCCAG | GTTTTAATTAGCGCAGACACATTGAAGTC | |

| TRPC7 | Sense | ACGCCTGATTAAGCGGTATGTGCTGAAG | CTCAGGTGGACCGAGAAAATGATGAA |

| Antisense | GCCAAAAGAGAGGCTCGGTGTGTTG | GCAAAGAGGAAGTTTTTGGCTTGGAATC |

Immunoprecipitation and western blot analysis

TRPC3–GFP was first established in the EGFP-N1 vector (Clontech), and transferred into pMXΔ. HEK or DT40 Cells (∼3 × 106) were lysed in 1 ml of RIPA buffer (pH 8.0) containing 150 mM NaCl, 0.5% NP-40, 0.1% sodium deoxycholate, 0.1% SDS, 50 mM Tris, 2 mM EGTA, 1 mM PMSF and 10 µg/ml leupeptin. GFP-tagged mTRPC3 or YFP-tagged PLCγ2 protein was immunoprecipitated in an RIPA buffer with 3 µl of anti-GFP polyclonal antibody (Clontech) in the presence of a 25 µl bed volume of Sepharose G–agarose beads (Amersham Pharmacia) rocking overnight at 4°C (Patterson et al., 2002). The immune complexes were washed three times with the RIPA buffer for 5 min at room temperature, and resuspended in 50 µl of the SDS sample buffer. The protein samples (5 µl) were fractionated by 8% SDS–PAGE and electrotransferred onto a nitrocellulose membrane (Inoue et al., 2001). The blots were incubated with an anti-PLCγ2 (Ishiai et al., 1999) or an anti-mouse TRPC3 antiserum, and stained using the ECL system (Amersham Pharmacia). The anti-mouse TRPC3 rabbit antiserum was directed against the C-terminus (EELAILHKLSEKLNPSVLRCE).

Analysis of ERK activity

Activation of ERK was determined by western blot with anti-phosphospecific ERK antibody (Cell Signaling). A total of ∼5 × 105 cells were stimulated in serum-free PSS, and then lysed in 50 µl of lysis buffer (50 mM Tris–HCl pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 5 mM EDTA, 1% Triton X-100, 100 µM Na3VO4, 2 mM dithiothreitol, 2 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 10 µg/ml leupeptin and 5 µg/ml aprotinin) for 10 min on ice. After centrifugation at 22 000 g for 10 min, 10 µl of supernatants were subjected to 10% SDS–PAGE and electrotransferred onto a nitrocellulose membrane. The total amount of ERK was detected by using anti-ERK polyclonal antibody (Santa Cruz Biotech). The bands were scanned and the density of each band was determined by NIH image software.

Statistical analysis

All data are expressed as means ± SEM The data were accumulated under each condition from at least three independent experiments. The P values are the results of Student’s t-tests.

Supplementary data

Supplementary data are available at The EMBO Journal Online.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

We thank Y.Okamura, H.Iwasaki and Y.Itsukaichi for comments. This work was supported by research grants from the Ministry of Education, Science, Sports, and Culture, Japan.

References

- Ananthanarayanan B., Das,S., Rhee,S.G., Murray,D. and Cho,W. (2002) Membrane targeting of C2 domains of phospholipase C-δ isoforms. J. Biol. Chem., 277, 3568–3575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bae Y.S., Cantley,L.G., Chen,C.S., Kim,S.R., Kwon,K.S. and Rhee,S.G. (1998) Activation of phospholipase C-γ by phosphatidylinositol 3,4,5-trisphosphate. J. Biol. Chem., 273, 4465–4469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bairoch A. and Cox,J.A. (1990) EF-hand motifs in inositol phospholipid-specific phospholipase C. FEBS Lett., 269, 454–456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berridge M.J. (1993) Inositol trisphosphate and calcium signalling. Nature, 361, 315–325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boulay G. et al. (1999) Modulation of Ca2+ entry by polypeptides of the inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor (IP3R) that bind transient receptor potential (TRP): evidence for roles of TRP and IP3R in store depletion-activated Ca2+ entry. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 96, 14955–14960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clapham D.E. (1995) Calcium signaling. Cell, 80, 259–268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark J.D., Lin,L.L., Kriz,R.W., Ramesha,C.S., Sultzman,L.A., Lin,A.Y., Milona,N. and Knopf,J.L. (1991) A novel arachidonic acid-selective cytosolic PLA2 contains a Ca2+-dependent translocation domain with homology to PKC and GAP. Cell, 65, 1043–1051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delmas P., Wanaverbecq,N., Abogadie,F.C., Mistry,M. and Brown,D.A. (2002) Signaling microdomains define the specificity of receptor-mediated InsP3 pathways in neurons. Neuron, 34, 209–220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dolmetsch R.E., Xu,K. and Lewis,R.S. (1998) Calcium oscillations increase the efficiency and specificity of gene expression. Nature, 392, 933–936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Essen L.O., Perisic,O., Cheung,R., Katan,M. and Williams,R.L. (1996) Crystal structure of a mammalian phosphoinositide-specific phospholipase C δ. Nature, 380, 595–602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falasca M., Logan,S.K., Lehto,V.P., Baccante,G., Lemmon,M.A. and Schlessinger,J. (1998) Activation of phospholipase C γ by PI 3-kinase-induced PH domain-mediated membrane targeting. EMBO J., 17, 414–422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feske S., Giltnane,J., Dolmetsch,R., Staudt,L.M. and Rao,A. (2001) Gene regulation mediated by calcium signals in T lymphocytes. Nat. Immunol., 2, 316–324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gamberucci A., Giurisato,E., Pizzo,P., Tassi,M., Giunti,R., McIntosh,D.P. and Benedetti,A. (2002) Diacylglycerol activates the influx of extracellular cations in T-lymphocytes independently of intracellular calcium-store depletion and possibly involving endogenous TRP6 gene products. Biochem. J., 364, 245–254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hara Y. et al. (2002) LTRPC2 Ca2+-permeable channel activated by changes in redox status confers susceptibility to cell death. Mol. Cell, 9, 163–173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harootunian A.T., Kao,J.P., Paranjape,S. and Tsien,R.Y. (1991) Generation of calcium oscillations in fibroblasts by positive feedback between calcium and IP3. Science, 251, 75–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofmann T., Obukhov,A.G., Schaefer,M., Harteneck,C., Gudermann,T. and Schultz,G. (1999) Direct activation of human TRPC6 and TRPC3 channels by diacylglycerol. Nature, 397, 259–263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inoue R., Okada,T., Onoue,H., Hara,Y., Shimizu,S., Naitoh,S., Ito,Y. and Mori,Y. (2001) The transient receptor potential protein homologue TRP6 is the essential component of vascular α1-adrenoceptor-activated Ca2+-permeable cation channel. Circ. Res., 88, 325–332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irvine R.F. (2002) Nuclear lipid signaling. Sci. STKE, 2002, RE13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishiai M. et al. (1999) BLNK required for coupling Syk to PLCγ2 and Rac1-JNK in B cells. Immunity, 10, 117–125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim M.J., Chang,J.S., Park,S.K., Hwang,J.I., Ryu,S.H. and Suh,P.G. (2000) Direct interaction of SOS1 Ras exchange protein with the SH3 domain of phospholipase C-γ1. Biochemistry, 39, 8674–8682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim Y.H., Park,T.J., Lee,Y.H., Baek,K.J., Suh,P.G., Ryu,S.H. and Kim,K.T. (1999) Phospholipase C-δ1 is activated by capacitative calcium entry that follows phospholipase C-β activation upon bradykinin stimulation. J. Biol. Chem., 274, 26127–26134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiselyov K., Mignery,G.A., Zhu,M.X. and Muallem,S. (1999) The N-terminal domain of the IP3 receptor gates store-operated hTrp3 channels. Mol. Cell, 4, 423–429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurosaki T. (2002) Regulation of B cell fates by BCR signaling components. Curr. Opin. Immunol., 14, 341–347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li W., Llopis,J., Whitney,M., Zlokarnik,G. and Tsien,R.Y. (1998) Cell-permeant caged InsP3 ester shows that Ca2+ spike frequency can optimize gene expression. Nature, 392, 936–941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyakawa T., Maeda,A., Yamazawa,T., Hirose,K., Kurosaki,T. and Iino,M. (1999) Encoding of Ca2+ signals by differential expression of IP3 receptor subtypes. EMBO J., 18, 1303–1308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyazaki S., Yuzaki,M., Nakada,K., Shirakawa,H., Nakanishi,S., Nakade,S. and Mikoshiba,K. (1992) Block of Ca2+ wave and Ca2+ oscillation by antibody to the inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor in fertilized hamster eggs. Science, 257, 251–255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montell C., Birnbaumer,L. and Flockerzi,V. (2002) The TRP channels, a remarkably functional family. Cell, 108, 595–598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mori Y. et al. (2002) Transient receptor potential 1 regulates capacitative Ca2+ entry and Ca2+ release from endoplasmic reticulum in B lymphocytes. J. Exp. Med., 195, 673–681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morii T., Sugimoto,K., Makino,K., Otsuka,M., Imoto,K. and Mori,Y. (2002) A new fluorescent biosensor for inositol trisphosphate. J. Am. Chem. Soc., 124, 1138–1139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okada T. et al. (1999) Molecular and functional characterization of a novel mouse transient receptor potential protein homologue TRP7. Ca2+-permeable cation channel that is constitutively activated and enhanced by stimulation of G protein-coupled receptor. J. Biol. Chem., 274, 27359–27370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okubo Y., Kakizawa,S., Hirose,K. and Iino,M. (2001) Visualization of IP3 dynamics reveals a novel AMPA receptor-triggered IP3 production pathway mediated by voltage-dependent Ca2+ influx in Purkinje cells. Neuron, 32, 113–122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parekh A.B., Fleig,A. and Penner,R. (1997) The store-operated calcium current ICRAC: nonlinear activation by InsP3 and dissociation from calcium release. Cell, 89, 973–980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patterson R.L., van Rossum,D.B., Ford,D.L., Hurt,K.J., Bae,S.S., Suh,P.G., Kurosaki,T., Snyder,S.H. and Gill,D.L. (2002) Phospholipase C-γ is required for agonist-induced Ca2+ entry. Cell, 111, 529–541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Putney J.W. (2002) PLC-γ: an old player has a new role. Nat. Cell Biol., 4, E280–E281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Putney J.W. Jr and Bird,G.S. (1993) The signal for capacitative calcium entry. Cell, 75, 199–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rebecchi M.J. and Pentyala,S.N. (2000) Structure, function and control of phosphoinositide-specific phospholipase C. Physiol. Rev., 80, 1291–1335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhee S.G. (2001) Regulation of phosphoinositide-specific phospholipase C. Annu. Rev. Biochem., 70, 281–312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Runnels L.W., Yue,L. and Clapham,D.E. (2002) The TRPM7 channel is inactivated by PIP2 hydrolysis. Nat. Cell Biol., 4, 329–336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato K., Tokmakov,A.A., Iwasaki,T. and Fukami,Y. (2000) Tyrosine kinase-dependent activation of phospholipase Cγ is required for calcium transient in Xenopus egg fertilization. Dev. Biol., 224, 453–469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saunders C.M., Larman,M.G., Parrington,J., Cox,L.J., Royse,J., Blayney,L.M., Swann,K. and Lai,F.A. (2002) PLC ζ: a sperm-specific trigger of Ca2+ oscillations in eggs and embryo development. Development, 129, 3533–3544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaefer M., Albrecht,N., Hofmann,T., Gudermann,T. and Schultz,G. (2001) Diffusion-limited translocation mechanism of protein kinase C isotypes. FASEB J., 15, 1634–1636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith M.R., Liu,Y.L., Matthews,N.T., Rhee,S.G., Sung,W.K. and Kung,H.F. (1994) Phospholipase C-γ 1 can induce DNA synthesis by a mechanism independent of its lipase activity. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 91, 6554–6558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugawara H., Kurosaki,M., Takata,M. and Kurosaki,T. (1997) Genetic evidence for involvement of type 1, type 2 and type 3 inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptors in signal transduction through the B-cell antigen receptor. EMBO J., 16, 3078–3088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutton R.B., Davletov,B.A., Berghuis,A.M., Sudhof,T.C. and Sprang,S.R. (1995) Structure of the first C2 domain of synaptotagmin I: a novel Ca2+/phospholipid-binding fold. Cell, 80, 929–938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tabata T., Aiba,A. and Kano,M. (2002) Extracellular calcium controls the dynamic range of neuronal metabotropic glutamate receptor responses. Mol. Cell. Neurosci., 20, 56–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takata M., Homma,Y. and Kurosaki,T. (1995) Requirement of phospholipase C-γ2 activation in surface immunoglobulin M-induced B cell apoptosis. J. Exp. Med., 182, 907–914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thorn P., Lawrie,A.M., Smith,P.M., Gallacher,D.V. and Petersen,O.H. (1993) Local and global cytosolic Ca2+ oscillations in exocrine cells evoked by agonists and inositol trisphosphate. Cell, 74, 661–668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trebak M., St J. Bird,G., McKay,R.R., Birnbaumer,L. and Putney,J.W.,Jr (2003) Signaling mechanism for receptor-activated canonical transient receptor potential 3 (TRPC3) channels. J. Biol. Chem., 278, 16244–16252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsien R.W. and Tsien,R.Y. (1990) Calcium channels, stores and oscillations. Annu. Rev. Cell. Biol., 6, 715–760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vazquez G., Wedel,B.J., Bird,G.S., Joseph,S.K. and Putney,J.W. (2002) An inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor-dependent cation entry pathway in DT40 B lymphocytes. EMBO J., 21, 4531–4538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venkatachalam K., Ma,H.T., Ford,D.L. and Gill,D.L. (2001) Expression of functional receptor-coupled TRPC3 channels in DT40 triple receptor InsP3 knockout cells. J. Biol. Chem., 276, 33980–33985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verkhratsky A. and Petersen,O.H. (2002) The endoplasmic reticulum as an integrating signalling organelle: from neuronal signalling to neuronal death. Eur. J. Pharmacol., 447, 141–154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye K. et al. (2002) Phospholipase C γ1 is a physiological guanine nucleotide exchange factor for the nuclear GTPase PIKE. Nature, 415, 541–544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu X., Jiang,M., Peyton,M., Boulay,G., Hurst,R., Stefani,E. and Birnbaumer,L. (1996) trp, a novel mammalian gene family essential for agonist-activated capacitative Ca2+ entry. Cell, 85, 661–671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]