Abstract

Mice deficient in early B cell factor (EBF) are blocked at the progenitor B cell stage prior to immunoglobulin gene rearrangement. The EBF-dependent block in B cell development occurs near the onset of B-lineage commitment, which raises the possibility that EBF may act instructively to specify the B cell fate from uncommitted, multipotential progenitor cells. To test this hypothesis, we transduced enriched hematopoietic progenitor cells with a retroviral vector that coexpressed EBF and the green fluorescent protein (GFP). Mice reconstituted with EBF-expressing cells showed a near complete absence of T lymphocytes. Spleen and peripheral blood samples were >95 and 90% GFP+EBF+ mature B cells, respectively. Both NK and lymphoid-derived dendritic cells were also significantly reduced compared with control-transplanted mice. These data suggest that EBF can restrict lymphopoiesis to the B cell lineage by blocking development of other lymphoid-derived cell pathways.

Keywords: B cell development/EBF/hematopoietic stem cell/T cell development/transcription factor

Introduction

The generation of hematopoietic cells occurs throughout life in adult mammals in a process that is initiated from long-term self-renewing hematopoietic stem cells (LT-HSC). LT-HSC divide to produce cells that remain multipotential but have more limited self-renewing capability (Morrison and Weissman, 1994). These transiently self-renewing stem cells continue to differentiate into cells that display increasingly restricted developmental potential. The earliest developmental intermediates that exhibit a restricted or lineage ‘committed’ phenotype include recently defined common lymphoid progenitor (CLP) cells in both mouse and man (Galy et al., 1995; Kondo et al., 1997) as well as common myeloid progenitor cells that give rise to all of the myelo-erythroid lineages found in the mouse (Akashi et al., 2000a). Other developmental intermediates have been characterized that display bi-potential phenotypes including a macrophage/B cell progenitor in mouse fetal liver and adult bone marrow (Cumano et al., 1992; Montecino-Rodriguez et al., 2001), and B/myeloid- and T/myeloid-restricted fetal liver progenitors defined by in vitro clonal assays (reviewed in Katsura and Kawamoto, 2001). In the thymus, thymic progenitors that are phenotypically defined as c-kit+CD44+ CD25–CD3–CD4–CD8– retain B, T, natural killer (NK) and dendritic cell (DC) potential (Shortman and Wu, 1996). These triple-negative (TN1) cells differentiate into bipotential, T- and thymic DC-restricted progenitors that are c-kit+CD44+CD25+CD3–CD4–CD8– (TN2). TN2 cells further develop into unipotential, T-cell committed progeny that are characterized by rearrangement events at the T cell receptor loci (CD44–CD25+CD3–CD4–CD8– cells, TN3 cells; Godfrey et al., 1993).

Early stages of B lymphocyte commitment and development in the mouse have been defined phenotypically by differential cell-surface expression of B220, CD19, CD43, BP-1 and IgM (Hardy et al., 1991; Li et al., 1996). Cells that are phenotypically B220+CD43+CD19– (Fraction A) represent a heterogenous population of cells that retain some ability to differentiate into other hematopoietic lineages (Li et al., 1993, 1996; Rolink et al., 1996; Tudor et al., 2000 and reviewed in Hardy and Hayakawa, 2001). Fraction A cells differentiate into cells that are restricted to the B cell lineage (Fraction B, B220+CD43+CD19+BP-1–IgM–; Hardy et al., 1991; Li et al., 1996). These cells further develop into cells that express cytoplasmic IgM and the pre-B cell receptor (Fraction C, B220+CD43+ CD19+BP-1+IgM–). A specific block in B-lineage development prior to Fraction B was found in mice that lacked either the E2A or early B cell factor (EBF) transcription factors, showing the absolute requirement for both factors in activating the B cell developmental program (Bain et al., 1994; Zhuang et al., 1994; Lin and Grosschedl, 1995).

EBF was first identified as a factor that regulated expression of the mb-1 gene, which comprises the Igα component of the B cell antigen receptor complex (Hagman et al., 1991). EBF expression is restricted to B-lineage cells from the earliest B-lineage progenitors to the mature B cell stage (Hagman et al., 1993). Binding sites for EBF can be found in a large number of B cell-specific genes including Pax5, mb-1, B29, λ5, VpreB, RAG-1 and the Ig light chain loci (Sigvardsson et al., 1997; Akerblad and Sigvardsson, 1999; Akerblad et al., 1999; Gisler et al., 1999; O‘Riordan and Grosschedl, 1999). As observed in E2A knockout animals, mice deficient in EBF lack detectable D–J gene rearrangement at the IgH locus but do express IgH sterile transcripts (Lin and Grosschedl, 1995). EBF-deficient mice also express transcripts for the IL-7 receptor α chain, PU.1, TdT and E2A, indicating that E2A factors are not sufficient to activate B-lineage commitment in the absence of EBF.

Additional data suggests that early B cell development is under the coordinate regulation of both E2A and EBF. This was shown in compound heterozygous mice that lacked one copy of both E2A and EBF (O‘Riordan and Grosschedl, 1999). Whereas single heterozygous mice displayed fairly mild developmental phenotypes among e17.5 fetal liver pro-B cells, E2A+/–EBF+/– animals exhibited a profound developmental block at the transition between Fraction B and Fraction C cells. There were also significantly reduced numbers of CD19+ Fraction B cells and a nine-fold reduction in the numbers of B220+CD43+ progenitor cells in the animals, which indicates that EBF and E2A proteins may act in the same genetic pathway to regulate downstream target genes. This was further established in transient transfection assays into the immature hematopoietic cell line, BaF/3, where E2A and EBF could synergistically activate transcription of the endogenous λ5 and VpreB genes (Sigvardsson et al., 1997). Additional studies have shown that EBF, λ5, Pax5 and RAG-1 can all be activated by expressing E12 (an E2A splice variant) in the 70Z/3 macrophage cell line, which suggests that EBF may normally be activated downstream of E2A (Kee and Murre, 1998). Pax5 expression is required for maintenance of the committed B cell state as indicated by acquisition of developmental multipotency in Pax5-deficient pro-B cells (Nutt et al., 2001). EBF can directly bind and activate the Pax5 promoter (O’Riordan and Grosschedl, 1999) so the activation of EBF may help to establish a B-committed phenotype through regulation of Pax5 activity in Fraction B cells.

The role of EBF in early B-lineage development raises the question of whether enforced expression of EBF in multipotential HSCs would restrict the developmental potential of HSC to the B cell lineage. To address this question, we used a murine retroviral vector to coexpress EBF and the green fluorescent protein (GFP) in an enriched population of hematopoietic progenitor cells. Transduced cells were transplanted into lethally irradiated recipient mice and then analyzed for their contribution to the various blood cell lineages. Analysis of peripheral blood in reconstituted animals showed that >90% of EBF+GFP+ cells were B-lineage cells. EBF+GFP+ cells in the spleens of reconstituted animals were >95% B cells that could respond to both T-dependent and polyclonal antigen stimulation. Normal ratios of κ and λ light chain-bearing B cells indicated that there was no clonal expansion of B-lineage cells due to EBF expression and no evidence of lymphoma or leukemia. Analysis of the thymus showed that EBF expression led to a near complete block in T cell development at the TN2 stage, with <0.5% of total thymocytes being EBF+GFP+. B cell development in the bone marrow was apparently normal with the exception that there was a significant increase in cells committed to the B-lineage (Fraction B cells). We also noted a reduction in other cell types derived from CLP cells in bone marrow, including NK and lymphoid-derived DCs. Taken together with the EBF knockout results, these data suggest that EBF functions to both promote B lymphopoiesis and to repress development of other lymphoid-derived cell lineages.

Results

Retroviral expression of EBF in hematopoietic cells

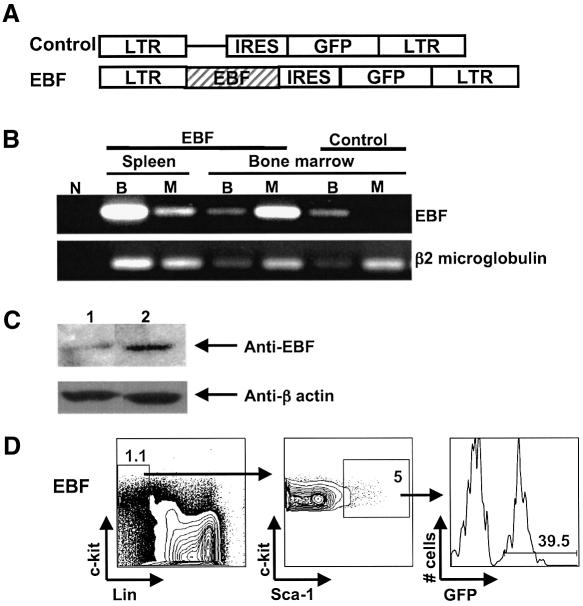

In order to determine whether enforced expression of EBF in uncommitted HSCs is sufficient to activate the B-lineage developmental program in vivo, we engineered a retroviral vector that coexpressed EBF and a GFP reporter gene (Figure 1A). EBF was cloned upstream of an internal ribosome entry site (IRES) and GFP in the parental murine stem cell virus (MSCV) retroviral vector (Hawley et al., 1994). The use of an IRES element allows for co-translation of both EBF and GFP from the same retroviral transcript. For the sake of clarity, we will refer to ‘EBF-expressing cells’ instead of ‘GFP-expressing cells’ when indicating cells transduced by EBF, even though the actual readout is for GFP expression.

Fig. 1. Retroviral expression of EBF in reconstituted animals. (A) Murine stem cell retroviral (MSCV) constructs. LTR, long terminal repeat; IRES, internal ribosomal entry site; GFP, green fluorescent protein; EBF, early B cell factor. (B) RT–PCR analysis demonstrates coexpression of EBF with GFP in transplanted cells. GFP+ myeloid (M: Mac-1+Gr-1+) or B-lineage (B: B220+) cells were sorted from transplanted GFP (control) and EBF- reconstituted mice. The lane designated ‘N’ has all RT–PCR reagents but no template as a control. (C) Western blot analysis of FACS-sorted, splenic B cells from control and EBF-reconstituted mice using an EBF polyclonal and a β-actin monoclonal antibody. (D) Analysis of the c-kit+Lin–Sca-1+ stem cell compartment in an animal reconstituted 12 weeks previously with EBF-expressing cells.

To characterize expression from the MSCV retroviral vector in primary cells, we sorted GFP+ cells by fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) from transplanted EBF and GFP control mice and extracted RNA for reverse transcriptase PCR analysis (RT–PCR). EBF is a B cell-specific gene and is not expressed in myeloid lineage cells in the hematopoietic system (Hagman et al., 1993). By RT–PCR analysis, EBF was coordinately expressed with GFP in all analyzed samples including myeloid lineage cells from bone marrow and spleen (Figure 1B). Expression of EBF was not detected in myeloid lineage cells (Mac-1+Gr-1+ cells) that expressed the control GFP vector or in control RT–PCRs that lacked RNA. Notably, the level of EBF expression from the retroviral vector was not higher than EBF expression from the endogenous locus (compare bone marrow B cells from GFP control with bone marrow B cells that express both endogenous and retroviral EBF in the EBF-reconstituted animals). This was confirmed by western blot analysis of FACS-purified B cells, where EBF protein levels were 2.6-fold higher in splenic B-lineage cells that coexpressed EBF from the retroviral vector (Figure 1C).

Expression of EBF in multipotential progenitor cells restricts development to the B cell lineage

To generate animals that expressed EBF at the HSC level, we harvested bone marrow from C57BL/6-Ly5.2 mice that had been treated with 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) four days previously (see Materials and methods). 5-FU treatment results in an 8–10-fold enrichment in primitive HSC due to killing of more mature cycling cells in bone marrow (Hodgson and Bradley, 1979). Harvested cells were co-cultured with retrovirus-producing cells for 48 h and then injected intravenously into congenic, lethally irradiated C57BL/6-Ly5.1 animals at a dose of ∼1–4 × 106 cells per transplant recipient. Confirmation of EBF expression within the primitive multipotent progenitor compartment of reconstituted animals was achieved by FACS analysis of c-kit+Lin–Sca-1+ cells in animals reconstituted for >12 weeks (Figure 1D). The stem cell surface phenotype in primary transplant recipients is the same as that found in unmanipulated bone marrow (Morrison et al., 1997). Additional support for the maintenance of EBF-expressing HSC was evidenced by no change in the level of GFP chimerism within short-lived, myeloid-lineage cells up to one year post-transplant, which strongly suggests that EBF does not influence HSC self-renewal. Loss of HSC potential would have readily been manifest as a significant reduction in the percentages of EBF+GFP+ myeloid-lineage cells over time, which was not the case.

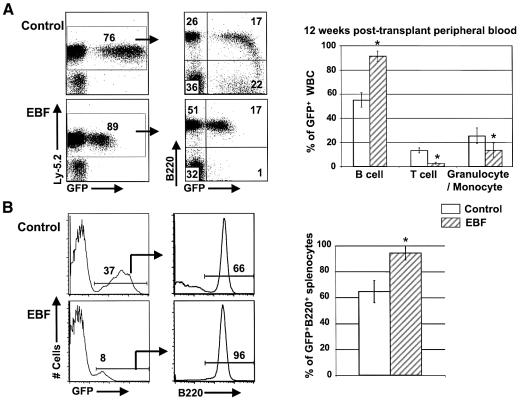

Reconstitution of transplant recipient animals was assessed by monitoring peripheral blood beginning at 4 weeks post-transplant. Analysis of peripheral blood in transplant recipients showed that EBF-expressing cells were almost entirely B-lineage cells based on expression of either the B220 or CD19 cell-surface markers at all time points examined (Figure 2A and data not shown). This was in contrast to animals reconstituted with cells expressing the control GFP vector, where the percentage of B-lineage (B220+) cells was in the range of 50–60% (n = 15 for both control and EBF-expressing animals). The mean percentage of B220+ cells in EBF-expressing animals at 12 weeks post-transplant was 92 ± 3.5% (n = 15, Figure 2A), which was similar to the percentage of B-lineage cells seen at both earlier (4 weeks) and later (out to 6 months) analysis times. We have maintained six EBF-reconstituted animals from three independent transplant experiments beyond one year without any signs of GFP+ B cell expansion or ill health, indicating that the high percentages of B lymphocytes are not reflective of B cell lymphoma or leukemia. Peripheral cells of the T cell lineage, characterized by CD3, CD4 and CD8 expression, were markedly reduced in all EBF-expressing animals and represented <3% of peripheral blood cells at 12 weeks post-transplant in all animals. The significant reduction in T lymphopoiesis was evident at all analysis points out to 24 weeks, indicating that there was not merely a delay in the development of mature T cells that expressed EBF. A statistically significant reduction in the frequency of myeloid lineage cells that expressed either the Mac-1 or Gr-1 cell-surface antigens was also evident in all animals reconstituted with EBF-expressing cells (P < 0.01, Figure 2A).

Fig. 2. EBF-expressing cells in the periphery are predominantly B cells. (A) Flow cytometric analysis of peripheral blood at 8 weeks post-transplant. GFP versus B220+ dot plots of representative GFP (control) and EBF-reconstituted animals were gated on donor Ly-5.2 cells. Bar graphs indicating the percentages of various blood cell lineages among the GFP+ cells are shown for 15 GFP (control) and 15 EBF mice at 12 weeks post-transplant. Error bars represent one standard deviation (P < 0.01). Samples containing an asterisk indicate statistically significant differences between control GFP and EBF-expressing populations. (B) Flow cytometric analysis of spleen cells from representative GFP control- and EBF-reconstituted animals. The B220 histograms were first gated on GFP+ cells in the spleen. The bar graph indicates the percentage of B220+GFP+ cells among the total GFP+ cells in the spleens from nine GFP control and 12 EBF-reconstituted animals at 12 weeks post-transplant (P < 0.01).

Analysis of the spleen in reconstituted animals showed that 95% of all EBF-expressing (GFP+) cells were B220+ (Figure 2B). Spleens from animals reconstituted with control GFP cells were 63% B220+. The remaining 5% of the GFP+ cells in the spleens of EBF-reconstituted animals primarily represented cells of the myeloid lineages. The percentage of T-lineage cells (CD3+) was always <2% for EBF-expressing animals (n = 12), whereas GFP control animals had 24.6% CD3+ T cells in spleen (n = 6, data not shown). The absolute numbers of splenocytes were not increased in EBF-transplanted mice and the spleens were morphologically normal compared with GFP control-transplanted animals.

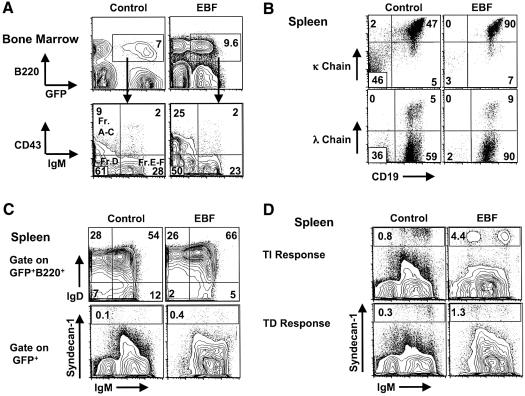

Maturation of EBF-expressing B cells proceeds through normal developmental intermediates

To assess whether B cell development proceeded through well-characterized developmental stages during maturation in the bone marrow and spleen, we stained bone marrow samples from 13 EBF-transplanted mice and nine GFP control mice between 8–16 weeks post-transplant with antibodies that delineate B cell developmental intermediates (Figure 3A). As shown in representative FACS analyses, we noted a 2–3-fold increase in the most immature Fraction A–C cells in EBF-expressing animals (n = 13, Figure 3A). The frequency of EBF+GFP+ Fraction A cells among the total GFP+ nucleated bone marrow cells increased 1.5-fold (P < 0.05), Fraction B increased six-fold (P < 0.01) and Fraction C cells increased three-fold compared with control GFP samples (P < 0.01) (data not shown). More mature developmental intermediates in the B cell pathway (Fractions E and F) were represented at comparable frequencies to control GFP samples. In addition, the absolute numbers of nucleated cells in bone marrow did not differ between EBF and control GFP mice.

Fig. 3. B cell development in bone marrow and spleen. (A) Bone marrow GFP+B220+ cells from representative animals were first gated and then analyzed for expression of CD43 and IgM. Fraction A–C cells are B220+CD43+IgM–, Fraction D cells are B220+CD43–IgM–, Fraction E–F cells are B220+CD43–IgM+. The results are representative of nine GFP (control) mice and 13 EBF mice generated from three independent transplant experiments. (B) Immunoglobulin light chain expression was analyzed on cells gated for GFP expression. κ chain versus CD19 and λ chain versus CD19 dot plots were from representative GFP control (n = 9) and EBF (n = 13) spleen samples. The normal κ:λ ratio in C57B/6 animals is 10:1. (C) B cell development and maturation in spleen of 12 week post-transplant animals: GFP control (n = 9) and EBF (n = 13). Cells gated as GFP+B220+ were analyzed for IgD versus IgM expression. Splenocytes gated as GFP+ were analyzed for syndecan-1 versus IgM expression by FACS. Gates on the syndecan-1 plots represent percentages of terminally differentiated plasma cells. (D) EBF-expressing B cells respond to T-dependent (TD) and polyclonal (LPS) antigen stimulation and become plasma cells. The response to LPS injection was representative of four GFP- and four EBF-reconstituted mice in two independent experiments. The TD response to sheep red blood cell injection was representative of two GFP and four EBF mice in two independent experiments. Cells gated for GFP expression were analyzed for syndecan-1 versus IgM expression. Gating on syndecanhi plasma cells is indicated.

Given that EBF has been shown to positively regulate expression of the Ig light chain loci (Romanow et al., 2000; Goebel et al., 2001), we stained for Igκ and Igλ expression on B lymphocytes in the bone marrow (data not shown) and spleen (Figure 3B). The normal ratio of κ+ B cells to λ+ B cells is ∼10:1 in C57BL/6 mice (Woloschak and Krco, 1987). We noted no significant difference in Ig light chain expression between EBF- and GFP-expressing B cells and observed the expected 10:1 ratio of κ- to λ-bearing B cells. These data indicate that EBF expression does not lead to a biased representation or selection of κ- or λ-bearing B cells or to an abnormal clonal expansion of a specific subset of B-lineage cells. We further analyzed B cell development and maturation in the spleen by surface IgD staining and by syndecan-1 staining for plasma cells (Figure 3C). We found normal frequencies of EBF-expressing IgD+ B cells versus control GFP+ B cells in the spleen (Figure 3C, n = 13 for EBF and n = 9 for GFP control stainings). In addition, the frequency of syndecan-1hi plasma cells among the total GFP+ cells was increased 3–5-fold among EBF-expressing B cells in either the spleen or in recirculating plasma cells in bone marrow (data not shown). We then tested EBF- and GFP control-expressing B cells from the spleen for responses to both T-dependent (TD) and polyclonal antigen stimulation in vivo (Figure 3D). We found that EBF-expressing B lymphocytes generated four-fold more plasma cells in response to the TD antigen stimulus (injection of sheep red blood cells 7 days prior to sacrifice of the animals, n = 4 for EBF and n = 2 for GFP control animals in two independent experiments) and five-fold more plasma cells in response to polyclonal stimulation [injection of bacterial lipopolysaccharide (LPS) 7 days prior to sacrifice, n = 4 for EBF and n = 4 for GFP control animals in two experiments] than control GFP-stimulated B cells. EBF expression did not influence class switching in response to antigen stimulation as evidenced by increases in IgM–syndecan-1hi B cells. In addition, EBF+ cells could become both follicular and marginal zone B cells (data not shown). Thus, sustained EBF expression during the terminal stage of B cell development does not inhibit plasma cell formation in response to either sheep red blood cell or LPS stimulation.

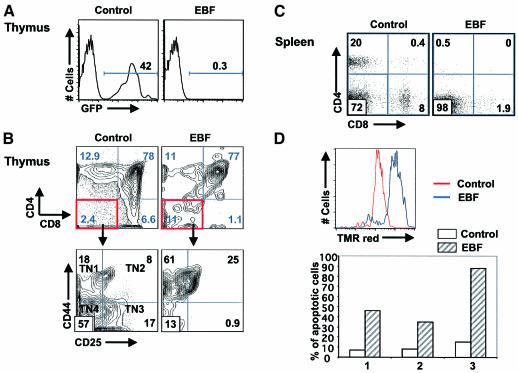

EBF expression blocks T cell development in the thymus

The severe reduction in T lymphocytes in both the peripheral blood and spleen of animals reconstituted with EBF-expressing cells suggested that T cell development in the thymus was being adversely affected by enforced expression of EBF. During adult thymocyte development, progenitors derived from bone marrow seed the thymus on a continual basis (reviewed in Fowlkes and Pardoll, 1989). EBF mRNA is normally expressed at the earliest CD44+CD25–CD3–CD4–CD8– stage (TN1 stage) and is then downregulated as cells differentiate to the CD44+CD25+CD3–CD4–CD8– stage (TN2 stage, Z.Zhang and C.Klug, unpublished observation). T cell commitment is thought to occur between the TN2 and TN3 stages, when rearrangement initiates at the TCRβ and γ loci (Godfrey and Zlotnik, 1993; Capone et al., 1998). We analyzed thymi from 10 GFP control and 15 EBF-reconstituted animals that were at least 12 weeks post-transplant from three independent transplant experiments and found that 0.3 ± 0.1% of the cells were EBF+GFP+ (Figure 4A). This level of GFP fluorescence was ten-fold higher than seen in analyses of autofluorescent cells in non-reconstituted thymi. Control GFP-reconstituted animals had between 20–70% GFP+ thymocytes that represented normal percentages of cells at different stages of T cell maturation (Figure 4A and data not shown). Even though the percentage of EBF+GFP+ cells in the total thymus was extremely low, we addressed whether EBF might be causing a developmental block at the earliest stages of thymocyte development, which represent populations that are quite rare. We found that thymocytes from EBF-reconstituted animals were partially blocked at the TN2 stage, with a very low percentage of cells that progressed to the CD4/CD8 double-positive and CD4 and CD8 single-positive stages (Figure 4B). Among the EBF-expressing TN subsets, the frequency of TN1 was increased three-fold and TN2 was increased 19.3-fold compared with GFP control-reconstituted animals, which showed normal percentages of the TN1, TN2 and TN3 subsets. These data suggest that thymic T cell development is blocked at the level of T cell commitment in the presence of EBF. The 2–3% CD3+ cells in the peripheral blood (Figure 2A) and the spleen (Figure 4C) would best be accounted for by the severe, but incomplete, block in early T cell development imposed by continued EBF expression. To assess whether EBF expression is compatible with T cell viability, we transduced the murine T cell line, EL4, with GFP control or EBF retroviruses and monitored the induction of apoptosis by TUNEL assay (Figure 4D). We found that EBF induced rapid apoptosis in a high percentage of EL4 cells within 48 h of transduction. Essentially all EBF+GFP+ cells were absent after one week of culture, which indicates that EBF expression is not compatible with T cell viability in a transformed T cell line. We observed no difference in the viability of a transformed B cell line, WEHI 231, which expressed either the EBF or GFP control retrovirus (data not shown).

Fig. 4. EBF-expressing T cells are severely reduced in thymus. (A) FACS analysis of GFP+ cells in the thymi of animals reconstituted with GFP control (n = 10) or EBF-expressing (n = 15) cells at 12 weeks post-transplant. (B) T cell development in the thymus is blocked at the TN2 stage in cells that express EBF. Cells were first gated as GFP+CD3–CD4–CD8– and then were analyzed for CD44 versus CD25 expression in animals transplanted with GFP control- or EBF-expressing cells. The various TN subsets are indicated. Results are representative of six GFP and six EBF mice. (C) Severe reduction of EBF+ T-lineage cells in the spleen at 12–16 weeks post-transplant. Splenocytes were gated for GFP expression and then analyzed for CD4 versus CD8 expression (n = 10 each). (D) EBF induces apoptosis in transduced EL4 cells. The percentage of GFP+TUNEL+ cells from control or EBF-transduced EL4 cells grown for 48 h is indicated for three independent experiments (red line, GFP control; blue line, EBF-expressing EL4 cells).

EBF expression inhibits NK and lymphoid-derived DC development

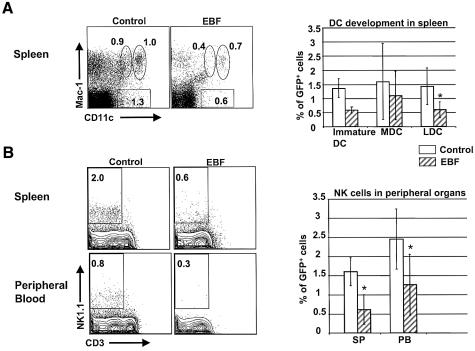

Both NK cells and DC subsets develop from progenitor cells found in both the bone marrow and thymus (Manz et al., 2001; Rosmaraki et al., 2001; Shortman and Liu, 2002). Mouse DC express both MHC class II and CD11c, and can be further classified into ‘lymphoid’ (LDC) or ‘myeloid’ DC (MDC) subsets by Mac-1 expression (Kamath et al., 2000; Shortman and Liu, 2002). MDC are CD11c+Mac-1+ whereas LDC are CD11c+Mac-1–. Recent work has shown that LDC can also be generated by progenitor cells restricted to the myeloid lineage (Traver et al., 2000; Manz et al., 2001), indicating that the development of certain DC subsets may occur through multiple developmental intermediates. Immature DCs in the spleen express intermediate levels of CD11c (Shortman and Liu, 2002). In the spleens of EBF-expressing animals, there was a statistically significant reduction of LDC (approximately three-fold) among EBF-expressing cells compared with GFP controls (P < 0.01, Figure 5A). Immature DC and MDC were not significantly reduced, indicating that EBF expression causes a specific reduction in LDC. NK cell development was analyzed by staining for expression of the NK1.1 cell-surface antigen along with co-staining for CD3 (Lanier et al., 1992; Lanier, 2000). Mature NK cells in the spleen and circulating NK cells in peripheral blood were significantly reduced in EBF-expressing animals (n = 10) compared with GFP controls (n = 10) at 12–16 weeks post-transplant (P < 0.01 for spleen and P < 0.05 for peripheral blood, Figure 5B). Conventional NK cells were reduced approximately three-fold in spleen and two-fold in peripheral blood.

Fig. 5. EBF expression leads to a partial block in dendritic and NK cell development. (A) Splenocytes were gated for GFP expression and then analyzed for Mac-1 and CD11c expression from animals transplanted with GFP control- and EBF-expressing cells. Immature DCs are gated as Mac-1+CD11cint, myeloid dendritic cells (MDC) are gated as Mac-1+CD11c+, and lymphoid dendritic cells (LDC) are Mac-1–CD11c+. The results represented by the bar graph are from seven GFP control and eight EBF-transplanted mice (standard deviation = 1). Asterisks indicate statistically significant differences between control GFP and EBF-expressing populations. (B) EBF expression partially blocks NK cell development. Spleen (SP) and peripheral blood (PB) cells from animals transplanted with GFP control- (n = 10) and EBF-expressing cells (n = 10) 12–16 weeks previously were first gated for GFP+ cells and then for mature NK cells (NK1.1+CD3–).

EBF acts downstream of HSC in the specification of B-lineage cells

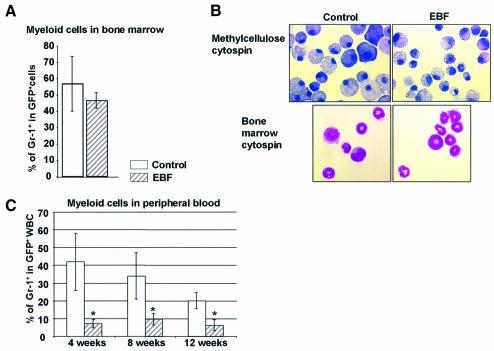

Although expression of EBF in bone marrow progenitor cells blocked T cell development and greatly reduced LDC and NK cells, myeloid lineage development in bone marrow was unaffected by EBF expression at the stem cell level (Figure 6A). FACS analysis of Gr-1+Mac-1+ cells in both GFP control- and EBF-expressing bone marrow cells (n = 6, GFP control mice; n = 12, EBF mice) showed no statistical difference in more differentiated myeloid-lineage cells bearing these surface markers at 10 weeks post-transplant (Figure 6A). Characterization of myeloid colony-forming progenitor cells that give rise to colony-forming unit (CFU)-granulocyte/macrophage (CFU-GM), CFU-E and CFU-GEMM showed that the both the number and size of specific colony types observed in methylcellulose cultures was not statistically different in platings of 20 000 GFP+ cells sorted from GFP control- or EBF-expressing bone marrow (n = 5 each for two independent experiments, data not shown). Cytospin preparations of methylcellulose colonies showed large numbers of macrophage and some granulocytic cells in both samples (Figure 6B). Morphologic examination of bone marrow cytospins from FACS-sorted GFP+Mac-1+Gr-1+ myeloid scatter-gated cells also revealed no difference in the development of myeloid cells in bone marrow in the presence or absence of EBF (Figure 6B). Curiously, we did observe greatly reduced percentages of granulocytic cells (as measured by Gr-1 and Mac-1 expression) in the peripheral hematopoietic organs of animals reconstituted with EBF-expressing cells (Figures 2A and 6C), suggesting some defect in the terminal maturation of EBF-expressing granulocytic cells in bone marrow or to more rapid turnover of EBF-expressing myeloid-lineage cells in the periphery. Since EBF is not normally expressed in myeloid-lineage cells, this terminal myeloid phenotype was not further characterized. Importantly, these results indicate that EBF expression at the stem cell level does not influence commitment between common lymphoid or common myeloid progenitor cells in bone marrow.

Fig. 6. Expression of EBF in the myeloid lineage results in a reduction of myeloid cells in the periphery. (A) The percentage of GFP+ granulocytes among the total GFP+ white blood cells is indicated for peripheral blood at 4, 8 and 12 weeks post-transplant. Data are representative of 12 GFP control and 12 EBF animals (standard deviation = 1). (B) Wright–Giemsa stain of cells isolated from either methylcellulose colonies or bone marrow cells sorted as GFP+Gr-1+Mac-1+ from animals reconstituted with GFP control- and EBF-expressing cells. Magnification is 1000×. (C) The bar graph indicates the percentage of GFP+Gr-1+ cells in bone marrow of animals 10 weeks post-transplant. Data are from six GFP control and ten EBF animals.

EBF expression in normal bone marrow and thymic progenitor subsets

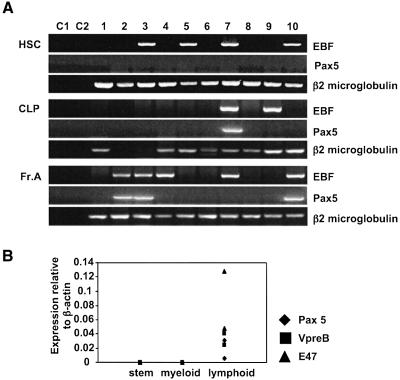

Since EBF expression was sufficient to restrict development to the B cell lineage at the expense of other lymphoid-derived lineages including T, NK and LDC cells, we wished to determine when endogenous EBF was expressed in hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells in bone marrow. Previous studies have shown that EBF is expressed beginning at Fraction A through the mature B cell stage, when it is then downregulated in terminally differentiated plasma cells. RT–PCR analysis of EBF mRNA expression was achieved by FACS-sorting five cells representing individual subsets directly into a well for the reverse transcriptase reaction that contained RT primers specific for EBF, Pax5 and β2 microglobulin, which served as a positive control for all reactions (See Materials and methods; Klug et al., 1998). All cells from each subset were sorted once and then resorted to ensure >98% purity of the sorted populations. After two rounds of nested PCR using primers that spanned at least one large intron, we found that almost half of the reactions containing sorted long-term self-renewing stem cells (LT-HSC, c-kit+Thy-1.1loLin–Sca-1+ cells; Morrison and Weissman, 1994) were positive for EBF expression (Figure 7). None of the same samples were positive for Pax5, indicating the specificity for EBF in each positive sample. Only ∼25% of the samples sorted for the CLP phenotype (Lin–IL-7R+c-KitloSca-1loThy-1.1–) expressed EBF while 55% of the samples representing Fraction A cells were EBF positive. As expected, all Fraction B cells, which represent B-lineage-committed progenitor cells, expressed EBF (data not shown). We also noted heterogeneity with respect to the coexpression of EBF and Pax5. A number of individual wells for CLP and Fr. A were positive for both factors whereas HSC only expressed EBF.

Fig. 7. Endogenous EBF expression in hematopoietic progenitor cells. (A) Bone marrow cells were double sorted for long-term self-renewing HSC as Lin–c-kit+Sca-1+Thy-1.1lo; common lymphoid progenitors (CLP) as Lin–c-kitintSca-1intThy-1.1loIL-7R+; Fraction A as B220+CD19–NK1.1–. Five cells per well were sorted directly into lysis buffer for the RT reaction followed by two rounds of nested PCR using primers for EBF, Pax5 and β2 microglobulin. C1 represents a control reaction without sorted cells while C2 represents a control reaction that contains five sorted cells without the addition of RT. (B) Real-time PCR was used to evaluate the relative expression of VpreB, Pax5 and E47 in sorted bone marrow populations from EBF- transduced cells. Each data point represents an average of 2–5 separate reactions containing 1000 cells each that were first normalized to an internal actin control in all reactions. Two independent experiments were performed for each sorted subset.

To determine whether EBF expression caused premature activation of the B cell program in non-B-lineage cells in bone marrow, we performed real-time PCR to analyze for expression of Pax5, E47 and VpreB in 1000 FACS-sorted c-kit+Sca-1+Lin– progenitors (five independent wells), in Gr-1+Mac-1+ myeloid cells (three independent wells) and in B220+CD19+ committed B cells (two independent wells) from two animals reconstituted with EBF-expressing cells (Figure 7B). All samples were normalized to an actin internal control for each well. We readily detected expression of Pax5, E47 and VpreB in the lymphoid wells from two independent experiments using two wells each. Expression of all three factors was below the level of detection in all progenitor and myeloid-lineage wells. Based on the lower limit of detection in the assay, there was at least a 50-fold lower level of each factor in non-B-lineage cells. This indicates that EBF was not sufficient to activate expression of three genes that are normally activated at the earliest stage of B cell development.

Discussion

Hematopoietic lineage specification from multipotential stem cells is a complex process that depends on the activities of multiple transcriptional regulatory proteins and the cell intrinsic and extrinsic signals that influence the balance of these activities. In the ‘multilineage priming hypothesis’ (Hu et al., 1997), multipotential stem cells express a number of ‘lineage-specific’ genes that are either repressed or sustained in their expression during subsequent development into more lineage-restricted progenitor cells. Expression of endogenous EBF in cells of the LT-HSC phenotype may represent such a primed state for a B-lineage-specific factor or, alternatively, may reflect functional heterogeneity within cells of the c-kit+Thy-1.1loLin–Sca-1+ phenotype. When EBF is expressed in LT-HSC using a retroviral vector, we noted no alteration in the self-renewal of EBF-expressing LT-HSC versus control GFP-expressing LT-HSC. This was measured by phenotypic enumeration of the HSC compartment in long-term reconstituted animals where we noted no difference in the number of EBF- or GFP control-expressing HSC in transplant-age matched animals (Figure 1C and data not shown). Animals reconstituted with EBF-expressing cells also sustained EBF+GFP+ myelopoiesis for over one year without any apparent changes in the ratio of GFP+ to GFP– myeloid cells in the animals. These observations support the idea that EBF does not alter the balance of self-renewal versus differentiation decisions occurring at the HSC level. Constitutive expression of EBF in HSC was also not sufficient to influence a lineage commitment decision between the lymphoid and myeloid cell pathways, since we observed no inhibition of myelopoiesis either at the myeloid progenitor cell level or in more differentiated myeloid cells in the bone marrow (Figure 6A and B).

Expression of EBF at the level of lymphoid progenitor cells did cause an apparent skew in development toward the B cell lineage in that all other lymphoid-associated lineages including T, NK and LDC were reduced in cells that expressed EBF (Figures 2, 4 and 5). However, repression of non-B-lineages may not have been at the level of lineage commitment in multipotent progenitor cells or CLP since we observed increased frequencies of both TN1 and TN2 thymocyte populations that expressed EBF (Figure 4). The severe reduction in T-lineage cells was most likely due to induction of apoptosis resulting from a failure to downregulate EBF during T cell commitment in the thymus. This is consistent with our observations that EBF is normally expressed in TN1 cells and is downregulated in TN2. As a population, TN1 cells retain T, B, NK and DC developmental potential so it would be instructive to know if TN1 cells that express EBF are more likely to develop into the small number of B-lineage cells that normally develop in the thymus (Akashi et al., 2000b). The block in thymocyte maturation we observe in EBF-expressing thymocytes at the TN2 stage occurs just prior to the block seen in Rag-1 or Rag-2 knockout animals, where T cell development is arrested at the TN2–TN3 stage (Godfrey and Zlotnik, 1993). Loss-of-function mutations in the basic-helix–loop–helix factors E2A or HEB lead to partial developmental blocks at the TN1 and the immature single positive stages, respectively (Bain et al., 1997; Barndt et al., 1999). TN2 cells initiate recombination events at the TCRβ and γ loci and have also lost B cell differentiation potential upon acquisition of CD25 expression. Interestingly, constitutive expression of EBF at the TN1 and TN2 stage did not promote thymic B cell development (as determined by B220 staining of thymocytes) but rather led to a developmental block in EBF-expressing TN2 cells. This indicates that EBF is not sufficient to activate the B cell developmental program within the thymus and that EBF can interfere with factors that stimulate T cell development at the onset of T-lineage commitment.

In the bone marrow, we observed an increase in early Fraction A–C cells that expressed EBF, with the major increase occurring at the Fraction B stage. The six-fold increase in EBF-expressing Fraction B cells (P < 0.01) could reflect an increase in the rate or frequency that Fraction A cells become Fraction B cells or could represent increased proliferation, reduced cell death, and/or an alteration in the kinetics of further B cell differentiation in the presence of EBF. Since not all Fraction A cells are committed to the B cell lineage or express endogenous EBF (Figure 7), expression of EBF in all Fraction A cells might increase the proportion of cells that differentiate along the B cell pathway.

The observation that mice deficient in EBF are blocked at Fraction A points out the requirement for EBF at a developmental stage coincident with B cell commitment (Lin and Grosschedl, 1995). Our data indicate that enforced expression of EBF in multipotential cells is not sufficient to drive all EBF-expressing cells to differentiate along the B cell pathway. Instead, the profound skewing of EBF+GFP+ cells to the B cell lineage in the peripheral blood (>90% B220+ cells) and spleen (>95% B220+ cells) is most likely due to both the promotion of B cell development by EBF expression in CLP cells as well as repression in the development of other lineages due to a failure in downregulating EBF during development. The observation that HSC function is not altered in the presence of EBF indicates that programs regulating processes like self-renewal or differentiation to the myelo-erythroid lineages cannot be overridden by the activity of one critical regulatory factor for B cell development.

Materials and methods

Construction of retroviral vector

A cDNA encoding EBF1 (kindly provided by Dr Rudolf Grosschedl) was cloned into the EcoRI site of the parental MSCV–IRES–GFP retroviral vector (Hawley et al., 1994). Orientation of the insert was confirmed by restriction digest and DNA sequencing.

Retroviral transduction of 5-FU-enriched bone marrow progenitor cells and transplantation

Retroviral transduction and transplantation was performed exactly as described in Cotta et al. (2003).

Antibodies and flow cytometry

The following antibodies were used: Thy1.1FITC, Gr-1PE, CD43PE, Ter-119PE, CD3PE, CD4PE, B220PE, NK1.1PE, IgDPE, syndecan-1PE, StreptavidinPE, c-kitAPC, Mac-1APC, B220APC, StreptavidinAPC, CD25bio, CD8bio, IL-7Rbio, Sca-1TexasRed, CD44PECy5, B220PECy5, IgMCy5 (Jackson Immuno Research), Igκbio, IgλPE (Southern Biotechnology Inc.). All antibodies were from Pharmingen unless indicated. Flow cytometric analysis was performed using either a FACS Calibur™ (Becton Dickinson) or by MoFlo (Cytomation).

Histology and myeloid colony-forming assay

For cytospins of bone marrow cells, 2 × 104 GFP+ cells stained with Gr-1PEMac-1PE were sorted into PBS with10% FCS. Cells were centrifuged onto glass slides and stained with Wright–Giemsa (Sigma). For methylcellulose assays, 20 000 EBF or GFP control bone marrow myeloid cells were sorted based on GFP expression into Iscove’s IMDM media supplemented with 10% FCS and then plated into MethCult™ 3434 media (StemCell Technologies). Colonies of >50 cells were phenotyped and counted prior to cytospin after 10 days.

T-dependent and polyclonal antigen stimulation

Mice reconstituted 12 weeks previously with EBF- or control GFP-expressing cells were injected intra-peritoneally with 250 µl of a 10% solution of sheep red blood cells (Colorado Serum, Denver, CO) or injected i.v. in the lateral tail vein with 40 µg LPS at 1 µg/ml concentration (Sigma Chemical Co.). Mice were sacrificed 7 days after injection for analysis.

TUNEL assay

The murine EL4 T cell line was transduced with GFP control or EBF retrovirus and then cultured at 37°C in 5% CO2. After 48 h, sorted viable GFP+ cells from both transductions were assayed for apoptotic cells by staining for TUNEL+ cells according to the manufacturer’s protocol (Roche, DNA apoptosis detection kit, Cat. 2 156 792).

RT–PCR

RT–PCR was performed on double-sorted cell populations isolated from bone marrow or spleen as previously described (Klug et al., 1998). Reverse transcriptase was performed using gene-specific primers for EBF, Pax5 and β2 microglobulin. EBF-RT primer: 5′-atgttatcagagactgccag-3′; EBF internal primer 1: 5′-ctcactttgagaagcagccgc-3′; EBF internal primer 2: 5′-catgtcacgtgggtttcctgc-3′; EBF external primer 3: 5′-ccaacacagcggcgcagagc-3′; EBF external primer 4: 5′-acatggccatccacgttgac-3′; Pax5-RT primer: 5′-catccctgtcagcgtcgg-3′; Pax5 internal primer 1: 5′-ctacaggctccgtgacgcag-3′; Pax5 internal primer 2: 5′-tcgccaagtctcggcctgtg-3′; Pax5 external primer 3: 5′-gcagagtagctgccctgtcc-3′; Pax5 external primer 4: 5′-ttccagtcacagca tagtgt-3′ β2-microglobulin RT primer: 5′-cgatcccagtagacggtcttg-3′; β2-microglobulin internal primer 1: 5′-ttcagtcgtcagcatggctc-3′; β2-microglobulin internal primer 2: 5′-catgcttaactctgcaggcg-3′; β2-microglobulin external primer 3: 5′-ttcagtggctgctactcggc-3′ and β2-microglobulin external primer 4: 5′-gctcggccatactgtcatgc-3′. PCRs were performed using two rounds of nested PCR of 30 cycles each round using external and then internal primer sets. Cycle conditions were 94°C for 30 s, 55°C for 20 s and 72°C for 20 s. Ten percent of the RT reaction was used for first round PCR, 5% of the first round PCR was used as template for second round PCR. β2-microglobulin was used as an internal control for all reactions.

Real-time PCR

cDNA was produced from 1000 cell aliquots using poly(dT) and random hexamer primers as described above. The PCRs were set up with 2× SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) using 1/20 of the cDNA reaction and run on an ABI Prism 7900HT sequence detection system (Applied Biosystems) per manufacturer’s instructions. The following primers were used in the PCRs, β-actin: 5′-gctctggctcctagcaccat-3′, 5′-gccaccgatccacacagagt-3′; VpreB: 5′-gctcatgctgctggcctatc-3′, 5′-tccaagggaagaagatgctaatg-3′; Pax5: 5′-gctggacagggcagctactc-3′, 5′-tgtagggacttccagaaaattcact-3′; E47: 5′-ggctctgacaaggaac tgagtga-3′, 5′-ccggctcttcccattgg-3′.

Western analysis

Five million splenic B cells (B220+) were FACS-sorted and run on a 10% SDS–PAGE gel, transferred to PVDF membrane, and then probed with an anti-EBF polyclonal antibody (C-20, Santa Cruz Biotech) and an anti-β-actin monoclonal antibody (Sigma cat A5441) to normalize for protein loading. Quantitation of bands was done by densitometry.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Dr Rudolf Grosschedl for the EBF cDNA and for helpful discussions. We also thank Dr John Kearney for help with i.v. injections and the fluorescent microscope; Colleen Witt, Sheetal Purohit, Rose Ko and Drs John Kearney, C.Scott Swindle, Mercedesz Balazs, Flavius Martin, Larry Gartland and Woong-Jai Won for valuable discussions and support. This work was supported by a Howard Hughes faculty development award to C.A.K. (53000281) and a Molecular and Viral Oncology Predoctoral Fellowship grant (5T32CA09467) to C.G.de G. Z.Z. and C.V.C. were supported by NIH grant RO1DK55650.

References

- Akashi K., Traver,D., Miyamoto,T. and Weissman,I.L. (2000a) A clonogenic common myeloid progenitor that gives rise to all myeloid lineages. Nature, 404, 193–197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akashi K., Richie,L.I., Miyamoto,T., Carr,W.H. and Weissman,I.L. (2000b) B lymphopoiesis in the thymus. J. Immunol., 164, 5221–5226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akerblad P. and Sigvardsson,M. (1999) Early B cell factor is an activator of the B lymphoid kinase promoter in early B cell development. J. Immunol., 163, 5453–5461. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akerblad P., Rosberg,M., Leanderson,T. and Sigvardsson,M. (1999) The B29 (immunoglobulin β-chain) gene is a genetic target for early B-cell factor. Mol. Cell. Biol., 19, 392–401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bain G. et al. (1994) E2A proteins are required for proper B cell development and initiation of immunoglobulin gene rearrangements. Cell, 79, 885–892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bain G. et al. (1997) E2A deficiency leads to abnormalities in αβ T-cell development and to rapid development of T-cell lymphomas. Mol. Cell. Biol., 17, 4782–4791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barndt R., Dai,M.F. and Zhuang,Y. (1999) A novel role for HEB downstream or parallel to the pre-TCR signaling pathway during αβ thymopoiesis. J. Immunol., 163, 3331–3343. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capone M., Hockett,R.D. and Zlotnik,A. (1998) Kinetics of T cell receptor β, γ, and δ rearrangements during adult thymic development: T cell receptor rearrangements are present in CD44(+)CD25(+) Pro-T thymocytes. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 95, 12522–12527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cotta C.V., Zhang,Z., Kim,H-G. and Klug,C.A. (2003) Pax5 determines B- versus T-cell fate and does not block early myeloid-lineage development. Blood, 101, 4342–4346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cumano A., Paige,C.J., Iscove,N.N. and Brady,G. (1992) Bipotential precursors of B cells and macrophages in murine fetal liver. Nature, 356, 612–615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fowlkes B.J. and Pardoll,D.M. (1989) Molecular and cellular events of T cell development. Adv. Immunol., 44, 207–264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galy A., Travis,M., Cen,D. and Chen,B. (1995) Human T, B, natural killer, and dendritic cells arise from a common bone marrow progenitor cell subset. Immunity, 3, 459–473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gisler R., Akerblad,P. and Sigvardsson,M. (1999) A human early B-cell factor-like protein participates in the regulation of the human CD19 promoter. Mol. Immunol., 36, 1067–1077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godfrey D.I. and Zlotnik,A. (1993) Control points in early T-cell development. Immunol. Today, 14, 547–553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godfrey D.I., Kennedy,J., Suda,T. and Zlotnik,A. (1993) A develop mental pathway involving four phenotypically and functionally distinct subsets of CD3– CD4– CD8– triple-negative adult mouse thymocytes defined by CD44 and CD25 expression. J. Immunol., 150, 4244–4252. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goebel P., Janney,N., Valenzuela,J.R., Romanow,W.J., Murre,C. and Feeney,A.J. (2001) Localized gene-specific induction of accessibility to V(D)J recombination induced by E2A and early B cell factor in nonlymphoid cells. J. Exp. Med., 194, 645–656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagman J., Travis,A. and Grosschedl,R. (1991) A novel lineage-specific nuclear factor regulates mb-1 gene transcription at the early stages of B cell differentiation. EMBO J., 10, 3409–3417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagman J., Belanger,C., Travis,A., Turck,C.W. and Grosschedl,R. (1993) Cloning and functional characterization of early B-cell factor, a regulator of lymphocyte-specific gene expression. Genes Dev., 7, 760–773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardy R.R. and Hayakawa,K. (2001) B cell development pathways. Annu. Rev. Immunol., 19, 595–621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardy R.R., Carmack,C.E., Shinton,S.A., Kemp,J.D. and Hayakawa,K. (1991) Resolution and characterization of pro-B and pre-pro-B cell stages in normal mouse bone marrow. J. Exp. Med., 173, 1213–1225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawley R.G., Lieu,F.H., Fong,A.Z. and Hawley,T.S. (1994) Versatile retroviral vectors for potential use in gene therapy. Gene Ther., 1, 136–138. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodgson G.S. and Bradley,T.R. (1979) Properties of haematopoietic stem cells surviving 5-fluorouracil treatment: evidence for a pre-CFU-S cell? Nature, 281, 381–382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu M., Krause,D., Greaves,M., Sharkis,S., Dexter,M., Heyworth,C. and Enver,T. (1997) Multilineage gene expression precedes commitment in the hemopoietic system. Genes Dev., 11, 774–785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamath A.T., Pooley,J., O‘Keeffe,M.A., Vremec,D., Zhan,Y., Lew,A.M., D‘Amico,A., Wu,L., Tough,D.F. and Shortman,K. (2000) The development, maturation, and turnover rate of mouse spleen dendritic cell populations. J. Immunol., 165, 6762–6770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katsura Y. and Kawamoto,H. (2001) Stepwise lineage restriction of progenitors in lympho-myelopoiesis. Int. Rev. Immunol., 20, 1–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kee B.L. and Murre,C. (1998) Induction of early B cell factor (EBF) and multiple B lineage genes by the basic helix–loop–helix transcription factor E12. J. Exp. Med., 188, 699–713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klug C.A., Morrison,S.J., Masek,M., Hahm,K., Smale,S.T. and Weissman,I.L. (1998) Hematopoietic stem cells and lymphoid progenitors express different Ikaros isoforms, and Ikaros is localized to heterochromatin in immature lymphocytes. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 95, 657–662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kondo M., Weissman,I.L. and Akashi,K. (1997) Identification of clonogenic common lymphoid progenitors in mouse bone marrow. Cell, 91, 661–672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanier L.L. (2000) Turning on natural killer cells. J. Exp. Med., 191, 1259–1262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanier L.L., Spits,H. and Phillips,J.H. (1992) The developmental relationship between NK cells and T cells. Immunol. Today, 13, 392–395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y.-S., Hayakawa,K. and Hardy,R.R. (1993) The regulated expression of B lineage associated genes during B cell differentiation in bone marrow and fetal liver. J. Exp. Med., 178, 951–960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y.-S., Wasserman,R., Hayakawa,K. and Hardy,R.R. (1996) Identification of the earliest B lineage stage in mouse bone marrow. Immunity, 5, 527–535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin H. and Grosschedl,R. (1995) Failure of B-cell differentiation in mice lacking the transcription factor EBF. Nature, 376, 263–267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manz M.G., Traver,D., Miyamoto,T., Weissman,I.L. and Akashi,K. (2001) Dendritic cell potentials of early lymphoid and myeloid progenitors. Blood, 97, 3333–3341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montecino-Rodriguez E., Leathers,H. and Dorshkind,K. (2001) Bipotential B-macrophage progenitors are present in adult bone marrow. Nat. Immunol., 2, 84–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrison S.J. and Weissman,I.L. (1994) The long-term repopulating subset of hematopoietic stem cells is deterministic and isolatable by phenotype. Immunity, 1, 661–673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrison S.J., Wandycz,A.M., Hemmati,H.D., Wright,D.E. and Weissman,I.L. (1997) Identification of a lineage of multipotent hematopoietic progenitors. Development, 124, 1929–1939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nutt S.L., Eberhard,D., Horcher,M., Rolink,A.G. and Busslinger,M. (2001) Pax5 determines the identity of B cells from the beginning to the end of B-lymphopoiesis. Int. Rev. Immunol.. 20, 65–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Riordan M. and Grosschedl,R. (1999) Coordinate regulation of B cell differentiation by the transcription factors EBF and E2A. Immunity, 11, 21–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rolink A., ten Boekel,E., Melchers,F., Fearon,D.T., Krop,I. and Andersson,J. (1996) A subpopulation of B220+ cells in murine bone marrow does not express CD19 and contains natural killer cell progenitors. J. Exp. Med., 183, 187–194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romanow W.J., Langerak,A.W., Goebel,P., Wolvers-Tettero,I.L., van Dongen,J.J., Feeney,A.J. and Murre,C. (2000) E2A and EBF act in synergy with the V(D)J recombinase to generate a diverse immunoglobulin repertoire in nonlymphoid cells. Mol. Cell, 5, 343–353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosmaraki E.E., Douagi,I., Roth,C., Colucci,F., Cumano,A. and Di Santo,J.P. (2001) Identification of committed NK cell progenitors in adult murine bone marrow. Eur. J. Immunol., 31, 1900–1909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shortman K. and Wu,L. (1996) Early T lymphocyte progenitors. Annu. Rev. Immunol., 14, 29–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shortman K. and Liu,Y.J. (2002) Mouse and human dendritic cell subtypes. Nat. Rev. Immunol., 2, 151–161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sigvardsson M., O‘Riordan,M. and Grosschedl,R. (1997) EBF and E47 collaborate to induce expression of the endogenous immunoglobulin surrogate light chain genes. Immunity, 7, 25–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Traver D., Akashi,K., Manz,M., Merad,M., Miyamoto,T., Engleman,E.G. and Weissman,I.L. (2000) Development of CD8α-positive dendritic cells from a common myeloid progenitor. Science, 290, 2152–2154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tudor K.S., Payne,K.J., Yamashita,Y. and Kincade,P.W. (2000) Functional assessment of precursors from murine bone marrow suggests a sequence of early B lineage differentiation events. Immunity, 12, 335–345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woloschak G.E. and Krco,C.J. (1987) Regulation of kappa/lambda immunoglobulin light chain expression in normal murine lymphocytes. Mol. Immunol., 24, 751–757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhuang Y., Soriano,P. and Weintraub,H. (1994) The helix–loop–helix gene E2A is required for B cell formation. Cell, 79, 875–884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]