Abstract

Chlorella virus DNA ligase is the smallest eukaryotic ATP-dependent DNA ligase known; it suffices for yeast cell growth in lieu of the essential yeast DNA ligase Cdc9. The Chlorella virus ligase–adenylate intermediate has an intrinsic nick sensing function and its DNA footprint extends 8–9 nt on the 3′-hydroxyl (3′-OH) side of the nick and 11–12 nt on the 5′-phosphate (5′-PO4) side. Here we establish the minimal length requirements for ligatable 3′-OH and 5′-PO4 strands at the nick (6 nt) and describe a new crystal structure of the ligase–adenylate in a state construed to reflect the configuration of the active site prior to nick recognition. Comparison with a previous structure of the ligase–adenylate bound to sulfate (a mimetic of the nick 5′-PO4) suggests how the positions and contacts of the active site components and the bound adenylate are remodeled by DNA binding. We find that the minimal Chlorella virus ligase is capable of catalyzing non-homologous end-joining reactions in vivo in yeast, a process normally executed by the structurally more complex cellular Lig4 enzyme. Our results suggest a model of ligase evolution in which: (i) a small ‘pluripotent’ ligase is the progenitor of the much larger ligases found presently in eukaryotic cells and (ii) gene duplications, variations within the core ligase structure and the fusion of new domains to the core structure (affording new protein–protein interactions) led to the compartmentalization of eukaryotic ligase function, i.e. by enhancing some components of the functional repertoire of the ancestral ligase while disabling others.

INTRODUCTION

DNA ligases repair DNA nicks containing 5′-phosphate (5′-PO4) and 3′-hydroxyl (3′-OH) termini (1). Nick joining depends on a high-energy cofactor, which can be either ATP or NAD+, depending on the ligase. Ligation entails three sequential reactions. In the first step, ligase reacts with the nucleotide cofactor to form a covalent ligase–adenylate intermediate in which AMP is linked via a phosphoamide bond to lysine (2–6). In the second step, the AMP is transferred to the 5′-PO4 at the nick to form DNA–adenylate (AppDNA) (7,8). In the third step, ligase catalyzes attack of the 3′-OH of the nick on DNA–adenylate to join the two polynucleotides and release AMP. The ATP-dependent ligases are exemplified by the bacteriophage T7 and Chlorella virus enzymes, for which atomic structures have been determined by X-ray crystallography (9,10). The Chlorella virus enzyme consists of a 188 amino acid N-terminal domain (domain 1) and a 110 amino acid C-terminal domain (domain 2). Within the N-terminal domain is an adenylate-binding pocket composed of five motifs (I, III, IIIa, IV and V) that define the polynucleotide ligase/mRNA capping enzyme superfamily of covalent nucleotidyl transferases (9–16). Motif I (27KxD GxR32) contains the lysine nucleophile to which AMP becomes covalently linked in the first step of the ligase reaction (5,10). Motifs III, IIIa, IV and V contain conserved side chains that contact AMP and play essential roles in one or more steps of the ligation pathway (6,9,10,17–19). The C-terminal domain comprises an oligomer-binding fold (OB-fold) consisting of a five-stranded antiparallel β barrel and an α helix. The OB-fold domain includes nucleotidyl transferase motif VI, which is uniquely required for step 1 of the ligase reaction (20).

The 298 amino acid Chlorella virus ligase is the smallest eukaryotic ATP-dependent ligase that has been characterized (21). It consists only of the catalytic core, without the large N- or C-terminal flanking domains found in eukaryotic cellular DNA ligases (22). Nonetheless, Chlorella virus DNA ligase sustains mitotic growth and DNA repair in budding yeast when the two known yeast DNA ligases (Cdc9 and Lig4) are deleted and the viral protein is the only source of ligase in the cell (23). The Chlorella virus ligase has an intrinsic nick sensing function, whereby it binds avidly to singly nicked duplex DNA containing a 5′-PO4 at the nick, but not to nicked DNA containing a 5′-OH, to intact duplex DNA (the ligase reaction product), or to gapped DNA (17,21). Nick recognition by Chlorella virus DNA ligase also depends on occupancy of the AMP-binding pocket on the enzyme, i.e. mutations of the ligase active site that abolish the capacity to form the ligase–adenylate intermediate also eliminate nick recognition, whereas a mutation that preserves ligase–adenylate formation, but inactivates downstream steps of the strand-joining reaction, has no effect on binding to nicked DNA (17,24). Although there is no structure available for any DNA ligase bound to nicked DNA, the crystal structure of the Chlorella virus ligase–AMP intermediate provides a plausible explanation for why nick sensing is restricted to adenylated ligase and why the 5′-PO4 is required for DNA binding (10). The structure reveals a sulfate ion on the enzyme surface at a site adjacent to the phosphate of the bound AMP. The sulfate is proposed to mimic the 5′-PO4 of the nick. Consistent with this idea, the amino acid side chains of the ligase that bind the sulfate are essential for nick recognition and catalysis (10). The instructive point for nick sensing is that the ribose 3′-OH of the covalently bound AMP comprises part of the sulfate (5′-PO4) binding site (10).

To understand the structural basis for the chemical and conformational steps of ligation and DNA recognition, an extensive mutational analysis of the Chlorella virus ligase has been conducted, focusing on constituents of the nucleotidyl transferase motifs and other residues located near the putative DNA-binding site (17–20,24). The results, in concert with available crystallographic data, suggest that the active site of DNA ligase is remodeled during the three steps of the pathway and that some of the catalytic side chains play distinct roles at different stages. To fully understand the functional data and aid in the design of new mechanistic studies, further progress needs to be made on three fronts: (i) obtaining new crystallographic snapshots of ligase as it proceeds through the reaction pathway; (ii) delineating at higher biochemical resolution the DNA side of the ligase–DNA interface (which will in turn facilitate efforts to crystallize ligase bound to DNA); and (iii) examining the functional repertoire of a ‘minimal’ DNA ligase in vivo.

Here, we present experiments in which we establish the minimal length requirements for the 3′-OH and 5′-PO4 strands, crystallize Chlorella virus ligase–adenylate in a state construed to reflect the configuration of the active site prior to nick recognition, and show that the minimal Chlorella virus ligase is capable of catalyzing non-homologous end-joining (NHEJ) reactions in vivo in yeast, a process normally executed by the structurally more complex cellular Lig4 protein.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Assay of nick joining

Reaction mixtures (10 µl) containing 50 mM Tris–HCl (pH 8.0), 5 mM DTT, 10 mM MgCl2, 1 mM ATP, 0.25 pmol of 5′ 32P-labeled DNA substrate as specified and 2 pmol of Chlorella virus DNA ligase were incubated at 22°C for 10 min. The reactions were initiated by adding ligase and quenched by adding an equal volume of 100 mM EDTA and 95% formamide. The products were resolved by electrophoresis through a 20% polyacrylamide gel containing 7 M urea in TBE buffer (90 mM Tris-borate, 2.5 mM EDTA). Radio labeled DNAs were visualized by autoradiography. The extent of ligation was determined by scanning the gel using a FUJIX BAS2000 phosphorimager.

Adenylyltransferase assay

Reaction mixtures (20 µl) containing 50 mM Tris–HCl (pH 8.0), 5 mM DTT, 10 mM MgCl2, 40 µM [α-32P]ATP and 4 pmol of ligase were incubated for 5 min at 37°C. The reaction products were resolved by SDS–PAGE. Label transfer to the ligase polypeptide was visualized by autoradiography of the dried gel.

Plasmid-based assay of non-homologous end-joining in vivo

Yeast cells were transformed by the lithium acetate method with 100 ng of pRS413 plasmid DNA containing the HIS3 gene (parallel transformations were performed with uncut circular plasmid and linear plasmids generated by digestion with EcoRI, SacI or SmaI). Three different his3 haploid strains were transformed with each DNA: (i) a ‘wild-type’ ligase strain (CDC9 lig4Δ pLIG4 [CEN LIG4 TRP1]); (ii) a lig4Δ strain (cdc9Δ lig4Δ pCDC9 [CEN CDC9 TRP1]); and (iii) a strain deleted for both yeast ligases and containing Chlorella virus DNA ligase (cdc9Δ lig4Δ pChV-LIG [CEN ChV-LIG TRP1]). [Refer to Sriskanda et al. (23) for detailed descriptions of the strains and ligase plasmids.] His+ transformants were identified by plating on SD agar medium lacking histidine (and tryptophan). The efficiency of NHEJ was quantitated as the ratio of the number of His+ colonies arising in cells transformed with linear HIS3 DNA to the number of His+ colonies obtained from cells transformed with uncut circular plasmid DNA. Each datum is the average of three independent transformation experiments.

Crystallization of Chlorella virus DNA ligase

Crystals of wild-type ligase were grown at 4°C using the hanging drop vapor diffusion technique. The recombinant enzyme used for crystallization was purified from Escherichia coli as described previously (10). A 2 µl aliquot of protein (10 mg/ml) in 50 mM Tris–HCl (pH 8.0), 5 mM DTT and 0.1 M NaCl was mixed with an equal volume of reservoir buffer containing 4–6% polyethylene glycol 4000, 50 mM HEPES (pH 7.5) and 50 mM sodium acetate. The drops were equilibrated against 0.6 ml of reservoir buffer. Crystals of size 0.02 × 0.1 × 0.2 mm grew over 1 week.

Diffraction data collection and processing

Crystals were flash frozen in reservoir buffer supplemented with 30% glycerol. Diffraction data were collected at 100 K at a laboratory Cu Kα source (Rigaku RU-H3R) equipped with a RAXIS-IV++ imaging plate detector. Data were integrated and merged in the DENZO/SCALEPACK program suite (25).

Structure determination and refinement

The structure was determined by molecular replacement with the AMoRe program (26). The two individual domains of Chlorella virus D29A ligase–adenylate structure (PDB entry 1FVI) were used for the molecular replacement. The solution for the N-terminal nucleotidyl transferase domain was found first, followed by the C-terminal OB-fold domain. The model with both domains was refined using the ‘TLS & restrained refinement’ option in REFMAC (27,28). Residues 87–90, 206, 215–217, 279–283 and 294–297, absent in the initial model, were added using 2Fo – Fc and Fo – Fc maps, whereas residues 225–229 were removed and the Asp29 side chain was added. The results are summarized in Table 1. The atomic coordinates and structure factors have been deposited with the RCSB Protein Data Bank (accession code: 1P8L).

Table 1. Crystallographic data and refinement statistics.

| Space group | P21212 |

| Unit cell dimensions | a = 91.06 Å, b = 60.57 Å, c = 70.27 Å |

| α = β = γ = 90° | |

| Asymmetric unit contents | 277 amino acid residues |

| 1AMP | |

| 2H2O | |

| Total: 2252 non-H atoms | |

| Refinement resolution range (Å) | 15–2.95 |

| No. of unique reflections | 8265 |

| Redundancy factor | 3.5 |

| 〈I〉/〈σI〉 (last shell) | 8.5 (2.1) |

| Data completeness (last shell) (%) | 96.9 (95.3) |

| R-merge (last shell) | 0.092 (0.64) |

| Test data set size (%) | 8.2 |

| Work/test reflections | 7585/680 |

| R-work/R-free (%) | 26.30/30.35 |

| RMS deviations [bonds (Å), angles (°)] | 0.013, 1.575 |

| B-factors (Å2) | 26.2 |

Ligase mutants

Missense mutations were introduced into the pET-ChVLig expression plasmid as described (17). The entire ligase gene was sequenced in every case to confirm the desired mutation and exclude the acquisition of unwanted changes during PCR amplification and cloning. The expression plasmids were transformed into E.coli BL21(DE3). Mutant and wild-type ligases were purified from the soluble lysates of IPTG-induced BL21(DE3) cells by Ni-agarose and phosphocellulose chromatography as described (17). The protein concentrations of the phosphocellulose enzyme preparations were determined using the Bio Rad dye reagent with bovine serum albumin as a standard.

RESULTS

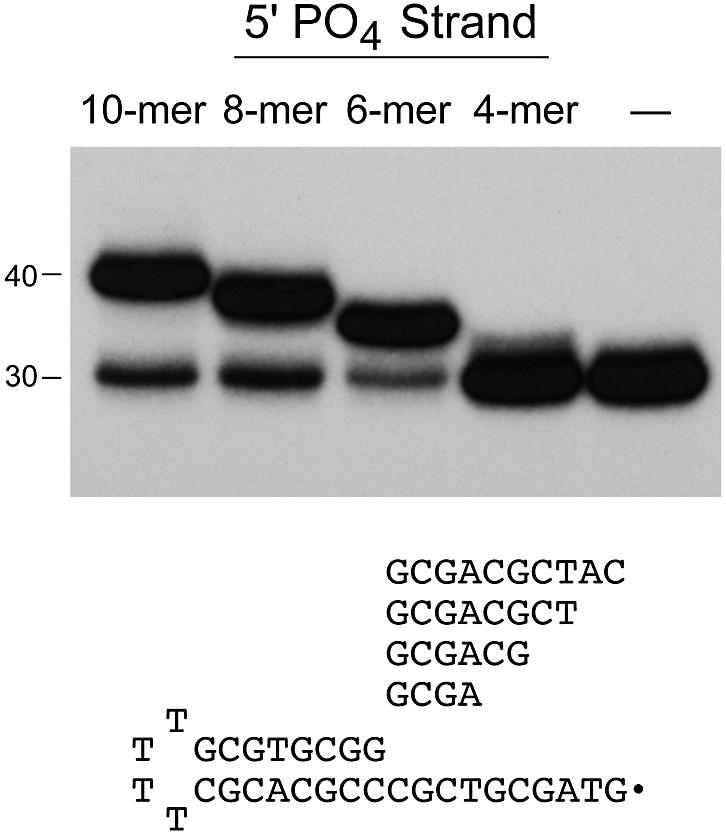

DNA length requirements on the 5′-PO4 and 3′-OH sides of the nick

We showed previously that the size of the exonuclease III footprint of ligase bound a single nick in duplex DNA was 19–21 nt (24). The footprint was asymmetric, extending 8–9 nt on the 3′-OH side of the nick and 11–12 nt on the 5′-PO4 side. Nuclease footprinting inherently overestimates the size of the ligase–DNA interface and does not address whether ligation activity depends on DNA occupancy of the entire footprint surface. In order to gauge the functional length requirements for strand sealing by Chlorella virus DNA ligase, we tested activity with substrates containing serially truncated 5′-PO4 strands. A 32P-labeled 30mer hairpin strand with a 10 nt 5′ single-strand tail was annealed to a 6-fold molar excess of unlabeled 5′-PO4 oligonucleotide complementary to the tail to form a set of nicked substrates containing an 8 bp duplex segment on the 3′-OH side of the nick and either 10, 8, 6 or 4 bp duplex segments on the 5′-PO4 side of the nick (Fig. 1). These substrates were reacted with an 8-fold excess of DNA ligase in the presence of 1 mM ATP. The 10mer, 8mer and 6mer 5′-PO4 strands were efficiently joined to the labeled 30mer to yield the expected 40mer, 38mer and 36mer 32P-labeled products (Fig. 1). In contrast, ligation of the 4mer strand was relatively feeble. A control reaction confirmed that there was no change in the mobility of the 30mer hairpin strand when a complementary oligonucleotide was omitted from the reaction (Fig. 1, lane –).

Figure 1.

DNA length requirements on the 5′-PO4 side of the nick. Unlabeled 5′-phosphorylated oligonucleotides (10mer, 8mer, 6mer and 4mer) were annealed in 6-fold molar excess to a 5′ 32P-labeled 30mer tailed-hairpin strand to form the series of nicked substrates illustrated in the figure. Ligation reaction mixtures containing 25 nM radiolabeled DNA substrate as specified and 200 nM ligase were incubated for 10 min at 22°C. The radiolabeled products were resolved by denaturing gel electrophoresis and visualized by autoradiography. The positions of the input 30mer strand and the 40mer product of sealing the 10mer 5′-PO4 strand are indicated on the left.

A kinetic analysis of the sealing of substrates containing a 5′-PO4 strand of varying length was performed (data not shown). The rates and extents of sealing of the 10mer, 8mer, and 6mer substrates were virtually identical. In each case, ∼75–80% of the labeled hairpin strand was ligated and the reaction was complete within 5–10 s. The kinetic profiles were similar to that seen for ligation of a nicked substrate containing an 18mer 5′-PO4 strand at the nick (data not shown). Thus, we conclude that a 6 nt 5′-PO4 strand sufficed for efficient ligation.

A possible explanation for the lower efficiency of ligation of the 4mer pGCGA strand was that it was too short to form a stable hybrid with the tail of the 30mer. We reasoned that the efficiency of ligation of the 4mer might be enhanced by increasing its concentration to drive the annealing reaction. Indeed, we found that the extent of ligation of the labeled 30mer to the unlabeled 4mer increased as the molar ratio of the 4mer to 30mer was increased from 5:1 to 30:1 and saturated thereafter with 75–80% ligation (data not shown). We infer that duplex stability, not ligation chemistry, is the limiting factor in utilization of the 4 nt 5′-PO4 strand by Chlorella virus ligase.

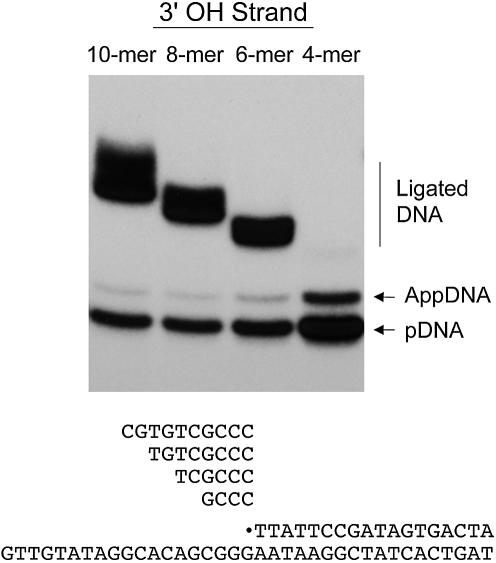

The length requirements for strand sealing on the 3′ side of the nick were tested using nicked substrates containing serially shortened 3′-OH strands. The substrates consisted of a 32P-labeled 18mer strand and an unlabeled 3′-OH strand (either 10, 8, 6 or 4 nt) annealed to an unlabeled template strand (Fig. 2). When reacted with an 8-fold excess of DNA ligase, the 10mer, 8mer and 6mer 3′-OH strands were efficiently joined to the 5′ 32P-labeled 18mer to yield the expected ladder of 32P-labeled products (Fig. 2). Only trace amounts of the DNA–adenylate intermediate (AppDNA) were observed in these reactions. A kinetic analysis of the sealing of the 10mer, 8mer and 6mer 3′-OH strands was performed (data not shown). Between 75 and 80% of the input 5′-PO4 strand was ligated in each case and the reactions attained their endpoints within 5–10 s. The kinetic profiles were similar to that seen for ligation of a nicked substrate containing an 18mer 3′-OH strand at the nick (data not shown). Thus, we conclude that a 6 nt 3′-OH strand sufficed for efficient and rapid ligation.

Figure 2.

DNA length requirements on the 3′-OH side of the nick. Unlabeled 3′-OH oligonucleotides (10mer, 8mer, 6mer and 4mer) were annealed in 6-fold molar excess to an unlabeled complementary template strand and a 5′ 32P-labeled 18mer strand to form the series of nicked substrates illustrated in the figure. Ligation reaction mixtures containing 25 nM radiolabeled DNA substrate as specified and 200 nM ligase were incubated for 10 min at 22°C. The radiolabeled products were resolved by denaturing gel electrophoresis and visualized by autoradiography. The positions of the input 5′ 32P-labeled 18mer (pDNA), the ligated DNA products and the DNA–adenylate intermediate (AppDNA) are indicated on the right.

The 4mer 3′-OH strand was not efficiently ligated, although the DNA–adenylate was formed and accumulated to a level higher than that seen in the other reactions (Fig. 2). A trace amount of the anticipated 22mer ligation product could be detected after prolonged autoradiographic exposure of the gel (data not shown). A control reaction confirmed that no DNA–adenylate was formed when a complementary 3′-OH oligonucleotide was omitted from the reaction (data not shown). Previous studies had shown that the 3′-OH of the nick is essential for transfer of AMP from ligase–adenylate to the 5′-PO4 strand to form the DNA–adenylate intermediate (24). We infer that even transient hybridization of the GCCCOH strand to the template strand permitted the DNA-adenylation step, but that either the short 3′-OH duplex segment of the nicked DNA–adenylate or the complex of ligase with the nicked DNA–adenylate was too unstable for efficient phosphodiester formation.

Chlorella virus DNA ligase can catalyze non-homologous end-joining reactions in vivo

We reported previously that Chlorella virus DNA ligase, which consists of the minimal catalytic domain of an ATP-dependent ligase, is fully capable of sustaining mitotic growth of budding yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae when the viral enzyme is the only ligase present in vivo (23). We also found that yeast cells containing only the Chlorella virus DNA ligase are relatively proficient in the repair of DNA damage induced by UV irradiation or treatment with MMS (23). Saccharomyces cerevisiae encodes two different DNA ligases, Cdc9 and Lig4, that play distinct roles in DNA replication, repair and recombination (29–34). Cdc9 catalyzes the joining of Okazaki fragments during DNA replication and it functions in the base excision and nucleotide excision repair pathways. Lig4 plays a specialized role in the repair of double-strand DNA breaks via the NHEJ pathway. Cdc9 is essential for mitotic growth; Lig4 is not essential. Cdc9 and Lig4 consist of the core catalytic domains found in Chlorella virus ligase, plus additional isozyme-specific domains located at their N- or C-termini. It is thought that these flanking segments may target cellular DNA ligases to sites where their action is required, via the binding of ligases to other proteins involved in DNA replication, repair or recombination. The fact that the Chlorella virus ligase can function in lieu of the essential cellular ligase Cdc9 in supporting the growth of S.cerevisiae suggested that a nick-joining activity suffices for yeast cell growth.

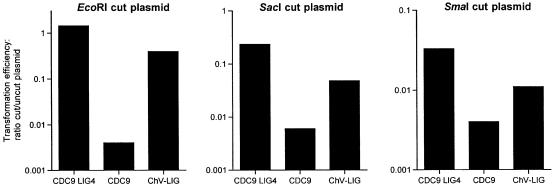

Here we pose the question: can Chlorella virus DNA ligase function in the NHEJ pathway in lieu of yeast Lig4? NHEJ is conveniently assayed by transformation of yeast cells with a linearized plasmid containing a selectable marker (32–34). In this study we used a CEN plasmid containing the HIS3 gene conferring histidine prototrophy. The plasmid contains single restriction sites for EcoRI, SacI and SmaI endonucleases, which will linearize the DNA and generate ends with either a 4 nt 5′ single-strand overhang (EcoR1), a 4 nt 3′ overhang (SacI) or a blunt duplex (SmaI). Successful transformation by the linear plasmid depends on sealing of the ends to produce a circular DNA molecule. The efficiency of NHEJ was quantitated as the ratio of the number of His+ colonies arising in cells transformed with a linearized plasmid to the number of His+ colonies obtained from cells transformed with an equivalent amount of uncut plasmid DNA. NHEJ was assayed in three yeast strains that differed in their content of DNA ligases: (i) a ‘wild-type’ yeast ligase strain expressing both Cdc9 and Lig4; (ii) a lig4Δ strain expressing only Cdc9; and (iii) a cdc9Δ lig4Δ strain expressing only Chlorella virus ligase (ChV-Lig). The results are shown in Figure 3, with transformation efficiency plotted on a logarithmic scale on the y-axis.

Figure 3.

Chlorella virus ligase catalyzes NHEJ reactions in vivo in yeast. NHEJ efficiency was determined using a linear plasmid transformation assay as described in Materials and Methods. The HIS3 plasmid was linearized by digestion with either EcoRI (left), SacI (middle) or SmaI (right). NHEJ efficiency was plotted on a log scale for the three yeast strains tested, which contained either the wild-type complement of yeast ligase genes (CDC9 and LIG4), CDC9 only (lig4Δ) or the Chlorella virus ligase gene only (cdc9Δ lig4Δ ChV-LIG).

In agreement with earlier studies (32–34), we found that the efficiency of NHEJ in wild-type cells was acutely dependent on the configuration of the ends of the linear plasmid substrate. DNAs containing 5′ cohesive ends formed by EcoR1 were just as effective as uncut plasmid in transforming yeast to histidine prototrophy (Fig. 3, left). The efficiency of linear transformation by EcoRI-cut DNA was reduced by a factor of 350 in lig4Δ cells, confirming the critical role of Lig4 in NHEJ with short cohesive ends. The instructive finding was that transformation efficiency was stimulated 100-fold over the lig4Δ background value in yeast cells expressing Chlorella virus DNA ligase only (Fig. 3, left). We conclude that the viral DNA ligase can substitute for yeast Lig4 in the NHEJ pathway for sealing double-strand breaks with 5′ cohesive ends.

The efficiency of NHEJ in wild-type yeast cells was reduced drastically when the linear DNA plasmid contained blunt duplex ends formed by SmaI (Fig. 3, right). The transformation efficiency with blunt-end DNA was 2.3% of the efficiency of NHEJ with EcoR1-cut plasmid. Deletion of Lig4 elicited only an 8-fold decrement in transformation efficiency with blunt-end DNA, which was restored partially in ChV-LIG cells (Fig. 3, right).

Plasmids containing 3′ cohesive SacI overhangs transformed wild-type yeast cells fairly efficiently (cut/uncut = 0.24), albeit slight less so than the plasmid with 5′ cohesive EcoRI ends. The modest difference between transformation efficiencies of linear DNAs with 5′ versus 3′ overhangs was also noted by Teo and Jackson (33). NHEJ efficiency with SacI-cut DNA was reduced by a factor of 40 in lig4Δ yeast cells, and was stimulated 8-fold over the lig4Δ background value in cells expressing only the Chlorella virus DNA ligase (Fig. 3, middle).

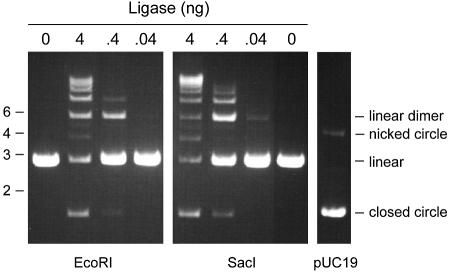

Ligation in vitro of linear plasmid DNAs with 5′ and 3′ overhangs and blunt duplex ends

The experiments presented above underscored the ability of a ‘minimal’ DNA ligase to catalyze NHEJ reactions in vivo. The viral ligase, like cellular Lig4, is best able to join plasmid DNA ends containing cohesive single-strand extensions. However, the in vivo transformation experiments do not reveal whether the effects of end configuration on NHEJ reflect: (i) the intrinsic specificity of the DNA ligase, (ii) the modulation of ligase activity at certain end configurations by accessory proteins or (iii) different alternative processing pathways for different DNA ends that render them more or less reactive (e.g., nuclease decay). Therefore, we assessed the intrinsic preference of Chlorella virus ligase for sealing linear plasmid ends in vitro using pUC19 DNA that had been linearized with EcoR1, SacI or SmaI.

EcoR1-cut linear DNA containing a 4-base 5′ overhang was efficiently sealed by Chlorella virus DNA ligase (Fig. 4). Linear dimers were generated preferentially at limiting enzyme concentrations, whereas at near-stoichiometric levels of enzyme (4 ng per reaction mixture) the products were heterogeneous and included covalently closed monomer circle, linear dimer and higher order linear arrays. The extent of ligation and the product distribution as a function of input enzyme was similar when the substrate was SacI-cut linear DNA containing a 4-base 3′ overhang (Fig. 4). In contrast, the viral ligase was unreactive with blunt-ended SmaI-cut pUC19 at enzyme levels as high as 100 ng per reaction mixture (data not shown). Thus, the inherent end preference of the viral ligase plausibly explains the finding that ChV-LIG yeast cells are relatively efficient in NHEJ of cohesive ends and very inefficient at NHEJ of blunt ends.

Figure 4.

Ligation of linear pUC19 DNA with cohesive overhangs. Reaction mixtures (10 µl) containing 50 mM Tris–HCl (pH 8.0), 5 mM DTT, 1 mM ATP, 0.2 µg (120 fmol) of pUC19 linearized with EcoR1 or SacI, and 0, 0.04, 0.4 or 4 ng of Chlorella virus DNA ligase (corresponding to ∼1, ∼10 or ∼100 fmol of enzyme) were incubated for 10 min at 22°C. The reaction products were analyzed by agarose gel electrophoresis in the presence of ethidium bromide. Uncut supercoiled pUC19 DNA was analyzed in parallel. A photograph of the stained gel under UV transillumination is shown. All lanes are from the same gel; the image was cropped to delete intervening lanes containing marker DNAs. The positions and sizes (in kilobase pairs) of linear DNA markers are indicated on the left. The species corresponding to linear dimer, nicked monomer circle, linear monomer and covalently closed monomer circle are indicated on the right.

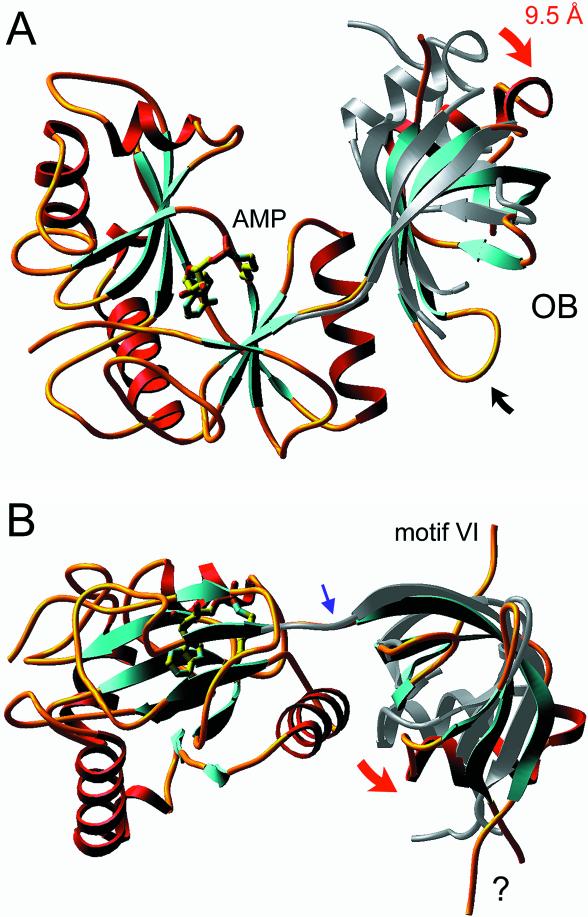

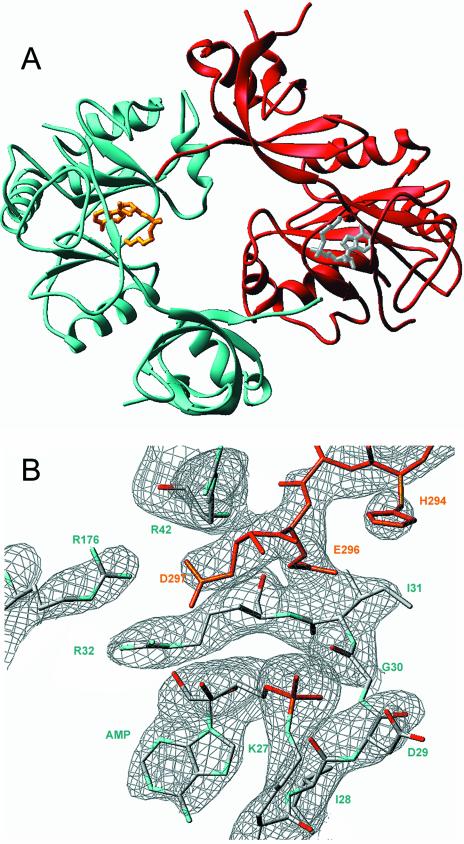

A new crystal structure of Chlorella virus ligase–adenylate highlights mobility of the OB-fold domain

We previously crystallized Chlorella virus DNA ligase using ammonium sulfate as the precipitant (10). The crystals were of space group P212121. The refined structure revealed that the active site was occupied by AMP covalently linked to Lys27 Nζ. A single well-ordered sulfate ion was seen on the protein surface ∼5 Å from the α phosphorus of AMP. It was proposed that this sulfate occupies the position of the 5′-PO4 of the DNA nick. Our efforts above to delineate the minimal 3′-OH and 5′-PO4 strands for efficient nick sealing by Chlorella virus ligase were undertaken in conjunction with efforts to crystallize the ligase–adenylate intermediate bound at a nick in a ‘minimized’ DNA ligand. We initiated DNA co-crystallization trails focusing on non-ionic precipitants that would be less likely to destabilize the protein–DNA interaction. We were able to grow crystals of the viral ligase in polyethylene glycol 4000, but said crystals did not contain DNA. The crystals grown in PEG-4000 were orthorhombic, with a different space group (P21212) and unit cell dimensions than the crystals grown previously in ammonium sulfate. The structure at 2.95 Å resolution was determined by molecular replacement using the individual nucleotidyl transferase and OB-fold domains of the earlier structure as search models.

A ribbon diagram of the new ligase structure is shown in Figure 5A. As in the structure reported previously, AMP is covalently linked to Lys27 at the active site (see the electron density map in Fig. 6B), even though the ligase preparation was not intentionally exposed to ATP during purification and crystal growth. We had shown previously that ∼15–25% of the recombinant ligase obtained from E.coli consists of the ligase–AMP intermediate. The new crystal structure reveals several features of the ligase not appreciated previously, most of which pertain to the C-terminal OB-fold domain. The images in Figure 5A and B show the positions of the OB domains of the current structure (the colored ribbon diagram) and the previous structure (the gray ribbon diagram) after superimposing the respective nucleotidyl transferase domains. (Note that only the nucleotidyl transferase domain of the new structure is shown in the figure.) It can be appreciated that the OB domain in the new structure has undergone a movement entailing retroflexion about a point within the interdomain linker (indicated by the blue arrow in Fig. 5B), which results in a 9.5 Å displacement of the OB domain at the distal end of the α helix located between the third and fourth β strands that make up the OB-fold (this movement is denoted by the red arrow in Fig. 5A). The view in Figure 5B highlights the downward and lateral displacement of the OB domain in the new versus old ligase structures (red arrow), which results in a more ‘open’ conformation of the enzyme.

Figure 5.

New crystal structure of Chlorella virus ligase–adenylate. The ligase fold is shown with α helices in red and β strands in cyan. AMP is bound covalently to Lys27 in a pocket within the N-terminal nucleotidyl transferase domain. The C-terminal OB domain is connected to the nucleotidyl transferase domain by a flexible linker within motif V [denoted by the blue arrow in (B)]. The images in (A) and (B) show the positions of the OB domains of the current structure (the colored ribbon diagram) and the previous structure (the gray ribbon diagram) after superimposing the respective nucleotidyl transferase domains. Only the nucleotidyl transferase domain of the new structure is shown. The view in (A) is looking down onto the active site and putative DNA binding surface; this surface is located at the top of the ligase molecule in the view shown in (B). Movements of the OB domain are indicated by red arrows. A disordered surface loop of the OB domain is indicated by ‘?’ in (B).

Figure 6.

Motif VI insinuates into the active site of a neighboring protomer. (A) Two symmetry-related ligase protomers are shown in cyan and red, respectively. The C-terminal peptide segments corresponding to motif VI project toward the active site of the neighboring protomer. (B) 2Fo – Fc electron density map of the active site region contoured at the 1σ level. The map highlights the covalent lysyl–AMP adduct and the proximity to the adenylate of the C-terminal Asp297 side chain coming from motif VI of the neighboring protomer (colored in red).

The new crystal structure allowed visualization of several surface elements that were disordered in the earlier structure: (i) the 279GSKDC283 loop connecting the fourth and fifth β strands of the OB-fold (indicated by the black arrow in Fig. 5A) and (ii) the distal segment 294HEED297 of nucleotidyl transferase motif VI (indicated in Fig. 5B). Deletion of this segment of motif VI blocks the ligase adenylation step of the nick-joining pathway, but spares the step of phosphodiester bond formation at an adenylated nick (20). This portion of motif VI was not seen in either the prior structure of Chlorella virus DNA ligase or the structure of T7 DNA ligase (9,10). In the present structure, motif VI projects up from the surface of the OB domain and it makes a lattice contact via the C-terminal Asp297 side chain with the active site of a symmetry-related ligase molecule in the unit cell (Fig. 6A; note the location of the C-terminus of the red protomer next to the AMP of the cyan protomer and the C-terminus of the cyan protomer near the AMP of the red ligase molecule).

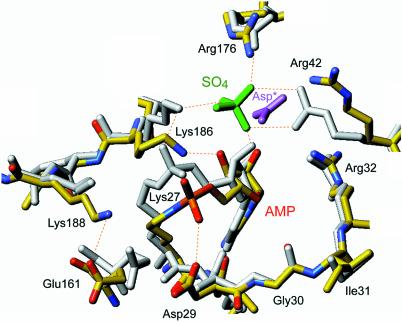

Different crystal structures of DNA ligase reveal plasticity of the active site

The AMP-binding pocket of DNA ligase is composed of the nucleotidyl transferase motifs (I, III, IIIa, IV and V) characteristic of the ligase/capping enzyme superfamily that act via lysyl-NMP intermediates. The electron density of the active site pocket in the new ligase crystal shows the covalent bond between Lys27 in motif I (27KIDGIR32) and the AMP phosphorus (Fig. 6B). The essential Arg32 side chain of motif I is located near the ribose 2′-O of AMP. Insinuated into the active site is the C-terminal Asp297 side chain of the symmetry-related protomer (colored red in Fig. 6B). The negatively charged carboxylate occupies a site on the enzyme surface similar to the sulfate-binding site in the earlier crystal structure, which is formed on the enzyme surface by the side chains of essential residues Arg42 and Arg176 (Figs 6B and 7). We surmise that in the absence of high concentrations of sulfate in the crystallization solution, the surface oxyanion-binding site is free to accept a lattice contact with the motif VI Asp from the other protomer. Note that the Asp is not bound at exactly the same position as the sulfate in the earlier structure and that the position of the Arg42 side chain is adjusted accordingly (Fig. 7).

Figure 7.

Differences in the active sites of the two crystal structures of ligase–adenylate. The active sites of the old and new ligase crystal structures are shown in a superposition of the nucleotidyl transferase domains, with the old protein structure colored uniformly gray (except for the green sulfate ion) and the new structure colored according to atom identity (carbon in yellow, nitrogen in blue, oxygen in red, phosphorus in orange). The Asp297 carboxylate coming from the neighboring ligase protomer is shown in lavender (Asp*).

The active sites of the old and new ligase crystal structures are superimposed in Figure 7 with the old protein structure colored uniformly gray (except for the green sulfate ion) and the new structure colored according to atom identity (carbon in yellow, nitrogen in blue, oxygen in red, phosphorus in orange). Although the polypeptide backbones of the elements comprising the adenylate-binding pocket are nearly identically disposed in the two structures (e.g., motif I 27KIDGIR32 and motif V 185IKMK188 segments shown in Fig. 7), there are subtle and mechanistically instructive differences in the position of the lysyl–AMP adduct and the atomic contacts made by some of the active site residues. The active site configuration in the previous sulfate-bound ligase structure was suggested to reflect the state of the ligase–adenylate intermediate just prior to catalysis of AMP transfer to the nicked DNA to form the DNA–adenylate. Lys186 bridges the AMP phosphate and the sulfate (i.e., the 5′-PO4), which correspond to the two reactive species in the second step of the ligase pathway. A ribose hydroxyl of the adenosine nucleoside directly coordinates the sulfate on the enzyme surface; this feature of the previous structure provided an explanation for the fact that nick sensing by Chlorella virus DNA ligase depends on ligase adenylation.

Figure 7 illustrates how the active site undergoes remodeling during the transition between the two crystal structures. The positions and contacts of the ribose sugar and the lysyl-phosphate are altered. The ribose has rotated about the glycosidic bond in the new structure so that the 3′-O (which coordinated the sulfate in the old structure) is engaged in a hydrogen bond with the Lys186 side chain, which has shifted position accordingly. The lysyl-phosphate has been retracted away from motif V and closer to motif I, thereby losing its contact with Lys186 (seen in the sulfate-bound structure) and gaining a contact with Asp29. The new structure also reveals an ion-pair between essential residues Glu161 (in motif IV) and Lys188 (in motif V); these side chains were not in contact with each other in the earlier structure (Fig. 7). Glu161 was implicated previously in co-ordinating the essential divalent cation cofactor for the DNA adenylation step (10). Because the new ligase structure lacks sulfate as a nick mimetic, we propose that its active site configuration reflects the state of the ligase–AMP intermediate prior to nick recognition.

Mutational analysis of a loop in the OB domain of Chlorella virus ligase

There was no interpretable electron density in the new ligase structure for a surface loop in the OB domain from residues 207 to 229 (indicated by ‘?’ in Fig. 5B). This loop was also disordered in the earlier ligase structure (10). Structure probing of Chlorella virus ligase in solution showed that sites of accessibility to chymotrypsin and trypsin (denoted by ↓) are clustered within this region: 204FKNTNTKTK↓DNFGY↓SK↓R↓STH↓K↓SGKVEED231. We reported previously that this segment is protected from proteolysis when ligase binds to nicked DNA (24). Such findings suggest either that the protected segment interacts with the DNA or undergoes a conformational change triggered by DNA binding. The position of the loop at the bottom end of the OB domain (Fig. 5B) is seemingly far away from the proposed DNA binding surface above the AMP-binding pocket. However, we cannot rule out that the position of the OB domain may change in the true DNA-bound state. In the absence of a defining structure, we sought to evaluate whether any of the positively charged side chains in the disordered loop were functionally relevant, the rationale being that basic residues were the most likely candidates to contact DNA via the phosphodiester backbone. Thus, we introduced single alanine substitutions in lieu of Lys205, Lys210, Lys212, Lys219, Arg220, Lys224 and Lys227 (mutated positions are underlined in the loop peptide sequence above.).

The Ala-substituted proteins were expressed in bacteria as His-tagged derivatives and purified from soluble bacterial lysates by Ni-agarose and phosphocellulose column chromatography as described (18,19). Each protein was assayed by its ability to form the ligase–adenylate intermediate and to ligate nicked DNA in the presence of ATP. All mutants were comparable with wild-type ligase in adenylyltransferase activity, which was evinced by the formation of a covalent ligase–32P-AMP adduct during a reaction of ligase with [α-32P]ATP (data not shown). The specific activities of the mutants in nick joining were determined by enzyme titration and the values were then normalized to the WT specific activity (defined as 100%). The normalized values were as follows: K205A (79%); K210A (63%); K212A (46%); K219A (80%); R220A (66%); K224A (81%); K227A (66%). None of the alanine mutations elicited a significant decrement in ligase activity. (Here, as in previous studies, we regard a 4-fold decrement in specific activity as the threshold of significance.) Thus, we surmise that none of the basic residues in the protease-sensitive loop is important per se for DNA ligation.

DISCUSSION

Functional repertoire of Chlorella virus DNA ligase

The present study extends our understanding of the strand-joining repertoire of Chlorella virus DNA ligase in vitro and in vivo. The minimal length requirements for a 6 nt 3′-OH strand and a 6 nt 5′-PO4 strand for efficient sealing in vitro were determined by truncating the reactive strands in 2 nt increments. The poor reactivity of 4 nt strands is surmised to reflect the instability of the 4 bp hybrid when there is no duplex segment distal to the annealed 4mer strand at the nick. The inefficient ligation of a 4mer annealed to a single-stranded template (Fig. 1) contrasts with the efficient sealing of linear duplex DNAs containing 4 nt cohesive ends, whether they be 5′ tails or 3′ tails (Fig. 4). Although the stability of the 4 bp hybrid is, in principle, similar in both instances, the plasmid cohesive ends may actually be more stable by virtue of base-pair stacking interactions across the nicks (35). Alternatively, the key difference between the two types of substrates may be that the ligase itself stabilizes the cohesive plasmid DNA ends by virtue of contacts with the DNA duplex at points more than 4 bp away from the 3′-OH/5′-PO4 nick. The existence of such contacts is consistent with the dimensions of the ligase footprint at a nick (24).

Our findings concerning the length requirements for ligation by Chlorella virus DNA ligase agree with the recent report of Nakatani et al. (36) that the ATP-dependent DNA ligase of Thermococcus kodakaraensis was able to seal 6 nt 3′-OH or 6 nt 5′-PO4 strands at 40°C, but was unable to ligate 5mer strands on either side of the nick. Pritchard and Southern (37) reported that T7 DNA ligase is also able to join a 6 nt strand on the 3′-OH side of a nick, but that Thermus thermophilus ligase requires at least an 8mer 3′-OH strand for efficient sealing.

We show here for the first time that a heterologous ATP-dependent DNA ligase can function in vivo to catalyze NHEJ reactions normally executed by cellular DNA ligase 4. NHEJ in S.cerevisaie is the province of an evolutionarily conserved set of interacting proteins that includes Lig4 and its binding partner Lif1 (corresponding to ligase IV and Xrcc4 in mammals) plus Hdf1 and Hdf2 (the yeast equivalents of the subunits of the mammalian DNA end-binding protein Ku) (32–34,38,39). Lig4 binds tightly to Lif1; this interaction serves to stabilize Lig4 in vivo, stimulate Lig4 catalytic activity and target Lig4 to DNA double-strand breaks (38,39). The interaction of Lig4 with Lif1 is mediated by a C-terminal domain that is not present in Chlorella virus DNA ligase. The fact that Chlorella virus ligase restores NHEJ activity on linear plasmid substrates in lig4Δ cells can be rationalized by the inherent damage-sensing function of the viral enzyme and its stability/activity in the absence of any protein partner. Yet, it is not simply the case that any ligase can substitute for Lig4 in vivo, insofar as neither over-expression of the yeast Cdc9 ligase nor engineering Cdc9 to interact with Lif1 in vivo was sufficient to permit Cdc9 to function in NHEJ in yeast (39). The prevailing view has been that the accessory domains of Cdc9 and Lig4 are essential for their specialized functions in vivo. Our results suggest that Chlorella virus ligase represents a stripped-down ‘pluripotent’ ligase that is able to perform most (if not all) of the functions imputed to Cdc9 and Lig4 in yeast. This includes the essential function of Cdc9 in maintenance of the mitochondrial genome (40,41) (V.Sriskanda and S.Shuman, unpublished results). We invoke an alternative view of ligase evolution in which: (i) a small pluripotent ligase is the progenitor of the large ligases found presently in eukaryotic cells and (ii) the fusion of new domains to the core ligase structure (with concomitant acquisition of new protein–protein interactions) along with variations within the core domains served to enhance some of the functional repertoire of the ancestral ligase while disabling other components of that repertoire.

The panfunctionality of a minimal Chlorella virus DNA ligase in vivo in yeast echoes the findings that DNA polymerase β, a minimal eukaryotic DNA polymerase, can complement the chromosomal and plasmid DNA replication functions and the DNA repair functions normally performed in E.coli by the much larger DNA polymerase I enzyme (42–44).

New structural insights to ligase mechanism

A previous comparison of the available crystal structures of ATP-dependent DNA ligases suggested that the nucleotide binding interactions are altered after the ligase–adenylate intermediate is formed (10). For example, the adenosine nucleoside of the Chlorella virus ligase–AMP adduct is in the anti conformation. This is in contrast to the syn conformation of adenosine in the crystal of T7 ligase bound to ATP (9). In addition to a shift of the nucleoside from syn to anti, the previous structure of Chlorella virus ligase–AMP reveals a remodeling of the contacts between the enzyme and the ribose oxygens compared with what was seen in the T7 ligase structure. The nucleoside conformation and the specific sugar contacts seen in the earlier crystal structure of the Chlorella virus ligase–AMP intermediate are proposed to reflect the state immediately prior to step 2 catalysis. Recent mutational studies focusing on the isolated step 3 reaction (phosphodiester formation at a preadenylated nick) suggest that the active site is remodeled again after completion of step 2 (18).

Although mechanistic points can be inferred by comparing the structures of different DNA ligase enzymes, it would be more helpful to capture crystal structures of the same ligase in different functional states. As discussed above, we propose that the new structure of Chlorella virus ligase–adenylate crystallized in the absence of sulfate reflects the state of the adenylated enzyme prior to nick recognition. The new structure highlights conformation flexibility of the OB domain relative to the nucleotidyl transferase domain. Major domain movements have been seen in crystallographic snapshots of Chlorella virus and Candida albicans mRNA capping enzymes (12,15). Formation of the capping enzyme–NMP intermediate requires the adoption of a closed conformation, in which the OB domain sits over the NTP-bound nucleotidyl transferase domain so that motif VI can contact the PPi leaving group and orient it properly for in-line reaction chemistry (12). A similar closed conformation is posited for DNA ligases (10), though not yet captured crystallographically. In the open conformations seen in the old and new Chlorella virus ligase crystal structures, the OB domain has moved well away from the AMP-binding site, thereby exposing an electrostatically positive surface that is predicted to bind nicked DNA. We surmise from the superposition of the old and new ligase structures that the position of the OB domain is flexible even in the open conformation (Fig. 7).

Remodeling of the positions and contacts of the active site components and the bound adenylate can be inferred from a comparison of the old and new ligase crystal structures. A key difference in the two states is the absence or presence of a sulfate ion. Because the sulfate contacts plausibly mimic those of the 5′-PO4, we envision that DNA binding triggers the changes in the active site seen in Figure 7. Obviously, it will be necessary to crystallize the ligase apoenzyme bound to ATP, ligase–adenylate bound to nicked DNA and ligase bound to nicked DNA–adenylate, in order to fully understand the conformational choreography of the DNA ligation reaction.

Acknowledgments

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We are grateful to Alexei Teplov and Valentina Tereshko for help in X-ray data collection. L.M. and M.T. are in the laboratory of Dinshaw Patel, who provided support (via NIH grant CA46778) and encouragement for the crystallographic component of this project. This work was supported by NIH grant GM63611 (to S.S.).

PDB ID 1P8L

REFERENCES

- 1.Doherty A.J. and Suh,S.W. (2000) Structural and mechanistic conservation in DNA ligases. Nucleic Acids Res., 28, 4051–4058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Little J.W., Zimmerman,S.B., Oshinsky,C.K. and Gellert,M. (1967) Enzymatic joining of DNA strands: an enzyme–adenylate intermediate in the DPN-dependent DNA ligase reaction. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 59, 2004–2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Weiss B., Thompson,A. and Richardson,C.C. (1968) Enzymatic breakage and rejoining of deoxyribonucleic acid: properties of the enzyme–adenylate intermediate in the polynucleotide ligase reaction. J. Biol. Chem., 246, 4523–4530. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gumport R.I. and Lehman,I.R. (1971) Structure of the DNA ligase–adenylate intermediate: lysine (epsilon-amino)-linked adenosine monophosphoramidate. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 68, 2559–2563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tomkinson A.E., Totty,N.F., Ginsburg,M. and Lindahl,T. (1991) Location of the active site for enzyme–adenylate formation in DNA ligases. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 88, 400–404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kodama K., Barnes,D.E. and Lindahl,T. (1991) In vitro mutagenesis and functional expression in Escherichia coli of a cDNA encoding the catalytic domain of human DNA ligase I. Nucleic Acids Res., 19, 6093–6099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Olivera B.M., Hall,Z.W. and Lehman,I.R. (1968) Enzymatic joining of polynucleotides: a DNA–adenylate intermediate in the polynucleotide joining reaction. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 61, 237–244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Harvey C.L., Gabriel,T.F., Wilt,E.M. and Richardson,C.C. (1971) Enzymatic breakage and rejoining of deoxyribonucleic acid: synthesis and properties of the deoxyribonucleic acid adenylate in the phage T4 ligase reaction. J. Biol. Chem., 246, 4523–4530. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Subramanya H.S., Doherty,A.J., Ashford,S.R. and Wigley,D.B. (1996) Crystal structure of an ATP-dependent DNA ligase from bacteriophage T7. Cell, 85, 607–615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Odell M., Sriskanda,V., Shuman,S. and Nikolov,D.B. (2000) Crystal structure of eukaryotic DNA ligase–adenylate illuminates the mechanism of nick sensing and strand joining. Mol. Cell, 6, 1183–1193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shuman S. and Schwer,B. (1995) RNA capping enzyme and DNA ligase—a superfamily of covalent nucleotidyl transferases. Mol. Microbiol., 17, 405–410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Håkansson K., Doherty,A.J., Shuman,S. and Wigley,D.B. (1997). X-ray crystallography reveals a large conformational change during guanyl transfer by mRNA capping enzymes. Cell, 89, 545–553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shuman S. (2001) The mRNA capping apparatus as drug target and guide to eukaryotic phylogeny. Cold Spring Harbor Symp. Quant. Biol., 66, 301–312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee J.Y., Chang,C., Song,H.K., Moon,J., Yang,J., Kim,H.K., Kwon,S.T. and Suh,S.W. (2000) Crystal structure of NAD+-dependent DNA ligase: modular architecture and functional implications. EMBO J., 19, 1119–1129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fabrega C., Shen,V., Shuman,S. and Lima,C.D. (2003) Structure of an mRNA capping enzyme bound to the phosphorylated carboxyl-terminal domain of RNA polymerase II. Mol. Cell, 11, 1549–1561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yin S., Ho,C.K. and Shuman,S. (2003) Structure-function analysis of T4 RNA ligase 2. J. Biol. Chem., 278, 17601–17608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sriskanda V. and Shuman,S. (1998) Chlorella virus DNA ligase: nick recognition and mutational analysis. Nucleic Acids Res., 26, 525–531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sriskanda V. and Shuman,S. (2002) Role of nucleotidyl transferase motifs I, III and IV in the catalysis of phosphodiester bond formation by Chlorella virus DNA ligase. Nucleic Acids Res., 30, 903–911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sriskanda V. and Shuman,S. (2002) Role of nucleotidyl transferase motif V in strand joining by Chlorella virus DNA ligase. J. Biol. Chem., 277, 9661–9667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sriskanda V. and Shuman,S. (1998) Mutational analysis of Chlorella virus DNA ligase: catalytic roles of domain I and motif VI. Nucleic Acids Res., 26, 4618–4625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ho C.K., Van Etten,J.L. and Shuman,S. (1997) Characterization of an ATP-dependent DNA ligase encoded by Chlorella virus PBCV-1. J. Virol., 71, 1931–1937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tomkinson A.E. and Mackey,Z.B. (1998) Structure and function of mammalian DNA ligases. Mutat. Res., 407, 1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sriskanda V., Schwer,B., Ho,C.K. and Shuman,S. (1999) Mutational analysis of Escherichia coli DNA ligase identifies amino acids required for nick-ligation in vitro and for in vivo complementation of the growth of yeast cells deleted for CDC9 and LIG4.Nucleic Acids Res., 27, 3953–3963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Odell M. and Shuman,S. (1999) Footprinting of Chlorella virus DNA ligase bound at a nick in duplex DNA. J. Biol. Chem., 274, 14032–14039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Otwinowsky Z. and Minor,W. (1997) Processing of X-ray diffraction data collected in oscillation mode. Methods Enzymol., 276, 307–326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Navaza J. (1994) AMoRe: an automated package for molecular replacement. Acta Crystallogr. A, 50, 157–163. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Murshudov G.N., Vagin,A.A. and Dodson,E.J. (1977) Refinement of macromolecular structures by the maximum-likelihood method. Acta Crystallogr. D, 53, 240–255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Winn M.D., Isupov,M.N. and Murshudov,G.N. (2001) Use of TLS parameters to model anisotropic displacements in macromolecular refinement. Acta Crystallogr. D, 57, 122–133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Johnston L.H. (1983) The cdc9 ligase joins completed replicons in baker’s yeast. Mol. Gen. Genet., 190, 315–317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tomkinson A.E., Tappe,N.J. and Friedberg,E.C. (1992) DNA ligase I from Saccharomyces cerevisiae: physical and biochemical characterization of the CDC9 gene product. Biochemistry, 31, 11762–11771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wu X., Braithwaite,E. and Wang,Z. (1999) DNA ligation during excision repair in yeast cell-free extracts is specifically catalyzed by the CDC9 gene product. Biochemistry, 38, 2628–2635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wilson T.E., Grawunder,U. and Lieber,M.R. (1997) Yeast DNA ligase IV mediates non-homologous DNA end joining. Nature, 388, 495–498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Teo S.H. and Jackson,S.P. (1997) Identification of Saccharomyces cerevisiae DNA ligase IV: involvement in DNA double-strand break repair. EMBO J., 16, 4788–4795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schär P., Herrmann,G., Daly,G. and Lindahl,T. (1997) A newly identified DNA ligase of Saccharomyces cerevisiae involved in RAD52-independent repair of DNA double strand breaks. Genes Dev., 11, 1912–1924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lane M.J., Paner,T., Kishin,I., Faldasz,B.D., Li,B., Gallo,F.J. and Benight,A.S. (1997) The thermodynamic advantage of DNA oligonucleotide ‘stacking hybridization’ reactions: energetic of a DNA nick. Nucleic Acids Res., 25, 611–616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nakatani M., Ezaki,S., Atomi,H. and Imanaka,T. (2002) Substrate recognition and fidelity of strand joining by an archaeal DNA ligase. Eur. J. Biochem., 269, 650–656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pritchard C.E. and Southern,E.M. (1997) Effects of base mismatches on joining of short oligodeoxynucleotides by DNA ligases. Nucleic Acids Res., 25, 3403–3407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hermann G., Lindahl,T. and Schär,P. (1998) Saccharomyces cerevisiae LIF1: a function involved in DNA double-strand break repair related to mammalian XRCC4. EMBO J., 17, 4188–4198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Teo S.H. and Jackson,S.P. (2000) Lif1p targets the DNA ligase Lig4p to sites of DNA double-strand breaks. Curr. Biol., 10, 165–168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Willer M., Rainey,M., Pullen,T. and Stirling,C.J. (1999) The yeast CDC9 gene encodes both a nuclear and a mitochondrial form of DNA ligase I. Curr. Biol., 9, 1085–1094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Donahue S.L., Corner,B.E., Bordone,L. and Campbell,C. (2001) Mitochondrial DNA ligase function in Saccharomyces cerevisiae.Nucleic Acids Res., 29, 1582–1589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sweasy J.B. and Loeb,L.A. (1992) Mammalian DNA polymerase β can substitute for DNA polymerase I during DNA replication in Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem., 267, 1407–1410. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sweasy J.B. and Loeb,L.A. (1993) Detection and characterization of mammalian DNA polymerase β mutants by functional complementation in Escherichia coli. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 90, 4626–4630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sweasy J.B., Chen,M. and Loeb,L.A. (1995) DNA polymerase β can substitute for DNA polymerase I in the initiation of plasmid DNA replication. J. Bacteriol., 177, 2923–2925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]