Abstract

HIV/AIDS and chemical dependency, both of which are complicated by and intertwined with mental illness, are complex, overlapping spheres that adversely influence each other and the overall clinical outcomes of the affected individual [1]. Each disorder individually impacts tens of millions of people, with explosive epidemics described worldwide. Drug users have increased age matched morbidity and mortality for a number of medical and psychiatric conditions. HIV/AIDS, with its immunosuppressed states and direct virologic effects, exacerbate morbidity and mortality further among HIV-infected drug users. This article addresses the adverse consequences of HIV/AIDS, drug injection, the secondary comorbidities of both, and the impact of immunosuppression on presentation of disease as well as approaches to managing the HIV-infected drug user.

Epidemiology

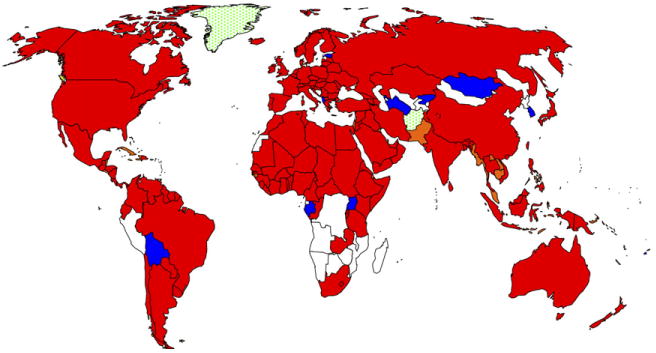

Both substance use disorders and HIV/AIDS individually impact tens of millions of people adversely, with explosive epidemics of both described worldwide (Fig. 1). Management of HIV infection among chemically dependent individuals requires considerable knowledge about multiple disciplines, including expertise in addiction medicine and psychiatry because of the overlapping epidemics of HIV, substance abuse, and mental illness [2,3,4]. Indeed, the capability of managing these conditions varies considerably between resource-rich and resource-limited regions of the world [2]. Injection drug use, largely of opiates, has been reported in 136 countries, and 114 of these countries have reported HIV among this population [3]. The link between drug use, particularly injection drug use, and HIV has been well described since the beginning of the HIV pandemic in North America [5,6], Europe [7,8], and Australia [9]. The world's most volatile and emerging epidemics are in areas that are fueled by illicit drug use, particularly heroin. Such places include the former states of the Soviet Union [10], other Eastern European countries [11], Southeast Asia [12], South America [13], and China [14]. Particularly troubling is that many of these epidemics are among individuals younger than 30 years and within the most densely populated regions of the world.

Fig. 1.

Worldwide distribution of HIV and IDU. White, no IDU reported; blue, IDU reported only, and red HIV and IDU reported. (Adapted from WHO Programme on Substance Abuse, and from Refs. [31,46,101]).

Prevalence rates of psychiatric disorders among HIV-infected patients approach 50% [15]. Although these conditions commonly manifest around the time of diagnosis [16], many patients develop symptoms later in the course of their illness [15]. Axis I disorders, including anxiety and depression, are particularly likely to occur at times of stress. Anxiety and depression are among the most commonly diagnosed psychiatric conditions affecting HIV-infected patients [17,18]. These disorders can complicate the treatment of HIV, presenting numerous diagnostic and interventional challenges for the clinician.

Substantial advances in the treatment of chemical dependency made in recent years can impact favorably the clinical and public health outcomes of both chemical dependence and HIV/AIDS; however, as is the case with highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART), their availability has been limited. The treatment of opioid dependence with evidence-based therapies is an example of this favorable health outcome. Opioid substitution therapy with methadone or buprenorphine is evidence-based therapy that has proven effective for both primary and secondary HIV prevention [19] and is cost effective for society [20]. Evidence is so extensive that the World Health Organization, the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, and the Joint United Nations Program on HIV/AIDS have supported the expansion of opiate substitution therapies worldwide [21,22].

In light of the increasingly central role of injection drug use in the global HIV/AIDS epidemic, issues of HIV clinical care and therapeutics in this population are of great importance. Of particular relevance are the special clinical features of HIV disease in chemically dependent patients, the treatment of HIV disease itself in this population, problems with diagnosing and treating mental illness, and the special difficulties in providing clinical care to drug users.

Infectious complications among HIV-infected drug users

Bacterial infections

The natural history of HIV disease among chemically dependent individuals is similar to that in patients in other transmission-risk categories [23]. Depending on the specific modes of substance use, however, chemically dependent persons are at a greater risk for a number of other infections than persons in other risk categories. Although most of these infections and complications were common among drug users before the HIV epidemic, their incidence, severity, and clinical presentation have been accentuated by HIV infection. In both inpatient and outpatient settings, these infections often are more common than specific HIV-related complications and often confound both diagnosis and treatment.

Multiple features of substance use, especially injection drug use, contribute to the increased risk of infection. The key elements resulting in these complications are

Increased rates of skin, mucous membrane, and nasopharyngeal carriage of pathogenic organisms

Unsterile injection techniques

Contamination of injection equipment or drugs with micro-organisms, which may be present in residual blood in shared injection equipment

Humoral, cell-mediated, and phagocyte defects induced by HIV infection and/or drug use

Poor dental hygiene

Impairment of gag and cough reflexes resulting in increased risk for aspiration and pneumonia

Alteration of the normal microbial flora by self-administered antibiotic use

Increased prevalence of exposure to certain pathogens (notably Mycobacterium tuberculosis)

Concomitant behaviors such as cigarette smoking, alcohol use, or exchange of sex for drugs or money

Decreased access to and/or lack of appropriate use of preventive and primary health care services

The following more detailed discussion of complications seen in chemically dependent HIV-infected individuals is summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

A summary of drug use related complications in HIV-infected injection drug users

| Location | Disease | Organisms | Treatment | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Skin and soft tissue | Cellulitis | Group A and other streptococci, S aureus | Antistaphylococcal agents | Consider hospitalization; consider MRSA |

| Abscess | Same as for cellulitis | Same as for cellulitis | Incision and drainage | |

| Necrotizing fasciitis | Polymicrobial | Parenteral antibiotics to cover both gram-positive and gram-negative organisms | If crepitus is noted, immediate surgical consultation is required | |

| Septic throm-bophlebitis | S aureus | Antistaphylococcal agents | Surgical exploration and vein ligation | |

| Cardio-vascular | Endocarditis | S aureus, streptococci, enteric gram-negative rods | Antistaphylococcal agents until cultures grow; treat for 4–6 weeks | Consider if regurgitant murmur; presence of peripheral or pulmonary emboli; positive blood culture; echocardiogram |

| Pulmonary | Airborne pulmonary infections | S pneumonia, H influenza, atypical organisms | PCN, cephalosporin, macrolide | |

| PCP | TMP/SMZ | Consider even with normal chest radiograph | ||

| Tuberculosis | Isoniazid

Rifampin Pyrazinamide Ethambutol |

Consider rifabutin because of PI interactions; rifampin has strong methadone interaction | ||

| Septic emboli | S aureus, streptococci, enteric gram-negative rods | Antistaphylococcal agents until cultures grow | Common complication, consider with pleuritic chest pain | |

| Liver | Hepatitis | Hepatitis B | Interferon

Lamivudine Adefovir Entecavir |

HBsAg positive |

| Hepatitis C | Pegylated interferon + ribavirin | HCV antibody positive with detectable RNA | ||

| Neurologic | Altered mental status | Substance-induced dementia, head trauma, hepatic encephalopathy | ||

| Neuropathy | ||||

| Cerebrovascular accident | Substance induced (cocaine or amphetamines) | |||

| Brain abscess | Same as for endocarditis | |||

| Hemorrhage caused by emboli | ||||

| Renal | Heroin or HIV nephropathy | Both present with nephrotic syndrome | Renal biopsy to establish diagnosis; electron microscopy distinguishes diagnosis | Focal and segmental glomerular sclerosis with progression to renal failure in weeks to months |

Abbreviations: HbsAg, hepatitis B surface antigen; MRSA, methicillin-resistant S aureus; PCP, Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia; PCN, penicillin; PI, protease inhibitor; RTV, ritonavir

The high frequency of skin and soft tissue infections results from unsterile intravenous, intramuscular (“muscling”), and subcutaneous (“skin popping”) injection combined with increased skin carriage of pathogenic organisms and/or exposure to adulterants that can cause tissue necrosis. The clinical spectrum ranges from simple cellulitis and abscesses to life-threatening, necrotizing fasciitis and septic thrombophlebitis. The clinical appearance of infection often is atypical because of long-standing damage to the skin and the venous and lymphatic systems, resulting in underlying lymphedema, hyperpigmentation, scarring, and regional lymphadenopathy. Nevertheless, careful examination often reveals characteristic redness, warmth, and tenderness. The presence of fever is variable. Bacteremia is infrequent, but when present, endovascular infection or empyema should be suspected. Although the precise microbial etiology is difficult to determine, uncomplicated cellulitis is caused most frequently by group A streptococci, other streptococci, or Staphyloccus aureus. Methicillin-resistant staphylococcus infections are becoming increasingly common, changing the treatment paradigm among patients in outpatient and inpatient settings [26,27]. Mild infections can be treated with oral antistaphylococcal agents on an outpatient basis when adherence to therapy is anticipated and patients will follow-up with future appointments to evaluate resolution. If applicable, patients should be warned about the decreased effectiveness of oral contraception and increased anticoagulant effect while taking these agents. In other instances, treatment should consist of hospitalization and administration of intravenous anti-staphylococcal agents (β-lactam antibiotics such as oxacillin or nafcillin). Abscess formation requires incision and drainage. Many experienced clinicians treat such infections with clindamycin. In areas with prevalent methicillin-resistant S aureus, vancomycin should be considered empirically among hospitalized patients while oral antibiotics should be used depending on the local susceptibility patterns. The total treatment duration should be 7 to 10 days at a minimum. More serious, indeed life-threatening, skin and soft tissue infections include necrotizing fasciitis, myositis, and septic thrombophlebitis. Although infrequent, they always should be considered. Crepitus may be noted, and soft tissue radiographs or other imaging studies may reveal gas in tissues. Immediate surgical exploration is critical, and extensive drainage and débridement of infected and nonviable tissue is essential. These infections often are polymicrobial in etiology. Parenteral antibiotic therapy targeting gram-positive and gram-negative aerobic and anaerobic organisms is essential. In rare instances, septic thrombophlebitis may result from an unsterile skin injection, requiring surgical exploration and vein ligation.

More benign indolent skin ulcers are common, particularly in female injection drug users. These ulcers result from “skin-popping” (subcutaneous injection) and consist of low-grade, foreign-body, granulomatous inflammation and necrosis. These shallow lesions may become superinfected. They usually respond to local wound care and oral or topical antibiotics. Occasionally, the ulcers are quite extensive and require skin grafting. Hyperpigmented, depressed scars often remain at the site of healed infections.

Other rare complications of injection drug use that result from unsterile injection include wound botulism [28,29], tetanus [24], and disseminated candidiasis [31,32]. Dermatologic examination also may reveal bruising on the forearms, chest, or face, which may reflect physical abuse. Understanding that chemically dependent individuals, especially women, experience a disproportionately higher degree of physical and sexual abuse than the general population, health care providers should have a high level of vigilance in evaluating for violence [25].

Bacterial endocarditis among injection drug users has received the greatest attention by clinicians and researchers; suspicion of its presence is among the more frequent reasons for hospitalization of drug users. Longer duration and increased frequency of intravenous drug use are associated with a cumulative increase in the risk of endocarditis. There is evidence that the incidence, rate of recurrence, and morbidity from endocarditis is greater among drug users who are HIV infected and severely immunocompromised [26]. Mortality from endocarditis, however, seems to be related more to the valve affected and to the organism causing the infection than to HIV serostatus. The use of alcohol swabs before injection has been associated with a reduction in bacterial complications from injection [27].

Among patients who have HIV disease, the differential diagnosis of endocarditis is broader and even more difficult. Febrile injection drug users with and without HIV disease should receive a detailed history and physical examination. Special attention should be directed to the presence of cutaneous and pulmonary septic emboli and to the presence of regurgitant murmurs. The absence of these signs does not exclude a diagnosis of endocarditis, resulting in the requirement of hospitalization of all febrile injection drug users in whom no other cause for the fever can be found [28]. Among injection drug users, most endocarditis is right sided; thus, there may not be systemic manifestations. Chest radiography should be performed to detect characteristic septic pulmonary emboli, and blood cultures and cardiac imaging studies should be obtained when possible.

S aureus is the most common responsible organism; streptococci and enteric gram-negative rods are seen less frequently. After blood cultures are obtained, empiric antibiotic therapy directed toward S aureus and dictated by local epidemiology should be initiated if the patient is acutely ill; if there is a high level of suspicion of left-sided endocarditis; and/or if septic pulmonary emboli are seen on radiograph.

The presence of fever only among injection drugs users is not sufficient cause to begin empiric treatment for endocarditis. Most drug users who present with fever do not have endocarditis. It is often reasonable to withhold antibiotics and observe the patient carefully until the blood culture results are known. Some patients may have only a minor transient illness or a pyrogenic or hypersensitivity reaction to injected drugs (“cotton fever”); in these cases, fever will abate within 24 hours after discontinuation of injection. In others instances, an alternative diagnosis will become apparent. The prognosis of right-sided staphylococcal endocarditis in this population is excellent. Generally, there is a good response to therapy, and mortality is low.

Endocarditis caused by other organisms and left-sided involvement carries a more serious prognosis, with higher complication and fatality rates. Outcome is determined largely by the extent of valve destruction, with resultant congestive heart failure, and the site and severity of peripheral arterial emboli. The duration of antibiotic therapy is controversial. Many experts prefer a full 4 weeks, but there are data to suggest that a shorter course is possible in uncomplicated right-sided endocarditis. Although often used, aminoglycoside antibiotics should be used with caution because of the high prevalence of underlying renal disease in this population [37–39].

HIV infection has increased dramatically the already high incidence of bacterial pneumonia among drug users. Prospective studies demonstrated that even when HIV-infected drug users were not actively injecting drugs, they had a four- to fivefold greater risk of bacterial pneumonia and sepsis than HIV-seronegative counterparts. The increase in frequency of bacterial pneumonia begins at CD4 counts above 350 cells/mm3 and, as with other HIV complications, increases further as the CD4 cell count falls. The organisms involved in HIV-related pneumonia among drug injectors are predominantly those reported in the earlier literature for community-acquired pneumonia.

Among other infectious entities to be considered in the differential diagnosis of pulmonary disease in this population of patients are Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia (also known as “PCP” or Pneumocystis jirovecii), tuberculosis, and septic pulmonary emboli. Often the diagnosis is sufficiently unclear so that both PCP and bacterial pneumonia are treated empirically until bronchoscopy and/or microbiologic data provide a precise diagnosis. Intravenous trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole cover both entities adequately, although it usually is possible to treat specifically for bacterial pneumonia, if strongly suspected, with a penicillin, cephalosporin, or macrolide antibiotic.

In developed countries, there are higher levels of latent infection with M tuberculosis among injection drug users than in other HIV-infected populations, resulting in a secondary global epidemic of resurgent tuberculosis. Worldwide, dual infection with HIV/tuberculosis is a leading cause of morbidity and mortality. Pulmonary tuberculosis should be suspected and included in the differential diagnosis among injection drug users who have pneumonia. Initial airborne isolation is recommended if the etiology of pneumonia is unclear or if clinical features raise the suspicion of tuberculosis. The diagnosis can be particularly difficult because chest radiographs often are atypical or absent of abnormalities, and extrapulmonary tuberculosis is more frequent. Initial therapy with four drugs (isoniazid, rifampin, pyrazinamide, and ethambutol) is recommended and is highly effective, but special efforts, including directly observed therapy, must be made to ensure long-term adherence to the regimen. The duration of therapy in HIV-infected patients who have tuberculosis is the same as in patients who are not HIV-infected. A special problem in treating this population is the interaction between rifampin and methadone and protease inhibitors. Rifampin decreases methadone levels; therefore, methadone doses must be raised to avoid precipitating opioid withdrawal. Rifabutin can be substituted for rifampin, and antiretroviral and methadone therapy can be continued under careful observation for antiviral effect and methadone withdrawal.

Both substance use and imprisonment are important risk factors for the spread of HIV and tuberculosis. Prisons provide an extremely efficient environment for the spread of tuberculosis. Because of poor therapy adherence and completion rates in these environments, multidrug-resistant tuberculosis has developed; further complicating the therapeutic options for HIV-infected substance users [29]. Increasingly resistant tuberculosis is being identified and an extensively resistant form (XDR) has recently been described in South Africa among HIV-infected individuals [40].

Viral hepatitis

The behaviors that put injection drug users at risk for HIV also put them at risk for viral infections. Both hepatitis B and C are acquired early after the initiation of injecting drugs. Hepatitis B and C are several-fold more prevalent than HIV infection among injection drug users [42,43]. Hepatitis B and C virus infections commonly lead to chronic hepatitis with persistent hepatic transaminase abnormalities, and ultimately, cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatitis A also has been associated with injection drug use [30]. This high prevalence has fueled efforts to increase vaccination against hepatitis A and B in this population [31]. As discussed in more detail later, alcohol abuse is common among injection drug users and can contribute to alterations in hepatic enzyme function and to the progression of existing hepatic disease [46–48]. A high prevalence of hepatic disease often complicates HIV therapeutics among injection drug users.

Renal disease

Severe renal disease is a frequent and characteristic complication of both injection drug use and HIV disease among injection drug users [37–39,49–51]. Many HIV-infected patients experience acute renal failure and electrolyte disorders because of volume depletion (caused by vomiting, diarrhea, or poor nutritional intake); recurrent AIDS-related opportunistic infections; or the use of nephrotoxic antiretroviral agents and other drugs (eg, aminoglycosides foscarnet, acyclovir, and amphotericin). In most cases, acute renal failure is reversible.

A more serious renal problem, HIV-associated nephropathy (HIVAN), is more prevalent among African Americans and those who have lower CD4 cell counts [52,53]. Clinical features of HIVAN include nephrotic-range proteinuria and reduced renal function, often requiring hemodialysis. Patients who present with this clinical scenario often require a biopsy to rule out potentially treatable causes of nephrotic syndrome (eg, minimal change disease). Histologically, the most consistent finding on biopsy includes focal segmental glomerulosclerosis and can be distinguished from heroin nephropathy only through the use of electron microscopy. Electron microscopy, combined with microcystic distortion and an absence of immunofluorescence findings, helps establish the diagnosis. HIV-associated nephropathy is usually progressive, may improve with HAART, and can progress rapidly to end-stage renal disease.

In short, special therapeutic issues in renal disease include the need for caution in the use of aminoglycoside antibiotics and other nephrotoxic agents in HIV-infected drug users, given the absence of data on the pharmacokinetics of antiretroviral medications in renal failure and dialysis.

Neurologic disorders

The differential diagnosis of neurologic disease is broader and often more difficult in drug users than in others who have HIV disease. Entering into the differential diagnosis of neurologic problems are drug-induced altered mental status, comorbid psychiatric disease, head trauma, intracerebral hemorrhage and other stroke syndromes (especially in cocaine and amphetamine users), and septic and particulate emboli to the brain and spinal cord. In addition, HIV-related opportunistic infections (eg, toxoplasmosis, cryptococcosis, tuberculosis, and other infections) and malignancies (eg, CNS lymphoma) can affect the central nervous system, and HIV itself can affect neurocognitive functioning [54–56]. Hepatitis C, a common infection in injection drug users, recently has been demonstrated to infiltrate the central nervous system and can independently cause neurocognitive deficits [57–59]. Injection drug users also commonly have neuropathic pain syndromes involving peripheral nerves and muscles. Additionally, HCV and HIV, as well as, HIV therapy can cause peripheral neuropathy. Diagnosis and treatment is often complicated by difficulties in pain management and has been reviewed elsewhere [60].

Treatment of HIV infection in drug users

HAART has resulted in impressive benefit for people living with HIV/AIDS, including decreasing morbidity [32], morality [33], and hospitalization [34], and has been demonstrated to be cost effective [35]. Despite the widespread availability of antiretroviral medications in resource-rich settings, injection drug users have derived less benefit than other populations [36]. This disparity in benefit is and probably will continue to be experienced in resource-limited settings even as antiretroviral medications become increasingly available for adults and children who have HIV disease. The reasons for the disparity are multifactorial.

In many societies worldwide, both HIV and illicit drug use are stigmatized so that either or both conditions often are cloaked in secrecy and may result in a lack of detection and treatment [66,67]. Drug users are among the most socially marginalized populations and often are hidden from mainstream medical care by circumstances and/or choice. Even when available, health care services often are constructed in ways that are difficult for many drug users to access, either by their absence in communities with high prevalence of drug use or by their organization that does not accommodate the chaotic and sometimes unpredictable use of services characteristic of drug-using populations. In addition, clinical care for drug users who have HIV disease is often challenging and stressful for clinicians and other health care workers because of the complex array of medical, psychologic, and social problems related to chemical dependency. The frequent comorbid underlying psychiatric disease often contributes to these difficulties. The chemically dependent patient may have increased difficulties with adherence to medications [37], and injection drug users, when prescribed antiretroviral therapy, are less likely to achieve a nondetectable viral load than their non–drug-using counterparts [38]. This nonadherence among chemically dependent patients may be compounded by underlying comorbid diseases, increased side effects, and drug interactions.

There is often mutual suspicion between drug users and health care providers. Clinicians tend to have stereotypic views of drug users and may harbor negative feelings about their social worth. As with other “difficult” patients, physicians may come to view drug users as manipulative, unmotivated, and undeserving of care [39]. The chronic, relapsing nature of chemical dependence as a medical disease often is not appreciated by clinicians, nor is the fact that drug users may be quite diverse and heterogeneous. Many physicians assume that drug users' antisocial behavior and drug use indicate a lifelong lack of concern for others and indifference to their own well-being, rather than a consequence of chemical dependence. Conversely, drug users are often mistrustful of the health care system and harbor expectations that they will be treated punitively. Drug users often conceal their continuing drug use from health care professionals out of fear of rejection prompted by previous difficult encounters with the health care system. In turn, clinicians sometimes are reluctant to confront patients with their suspicions about ongoing drug use, fearing that the confrontation will compromise their relationship. The failure to acknowledge ongoing drug use itself, however, can compromise the clinician–patient relationship because one of the most important aspects of the patient's health is off limits for discussion. Hence, it is imperative to be able to have an open dialogue about ongoing drug use, because the development of trust is critical for the acceptance and adherence to antiretroviral therapy [41].

Because the lives of chemically dependent patients often are chaotically organized around their substance use needs, successful programs for this population have developed some or all of the following characteristics:

Pharmacologic (eg, methadone program, buprenorphine treatment program) [42] and/or nonpharmacologic treatment (eg, Twelve Steps programs) for substance use [43]

Flexible outpatient and community care settings (eg, walk-in clinics, mobile health care programs) [44]

Low-threshold sites to engage active users (eg, syringe-exchange sites) [45]

Directly administered antiretroviral therapy (DAART) programs [46]

Intensive outreach and case management services [47]

Treatment during incarceration [48]

Clinicians involved in the care of drug users who have HIV should follow several key principles:

Become educated about substance abuse and its wide array of treatment options.

Establish a multidisciplinary team of individuals with expertise in managing HIV, substance abuse, and mental illness and broadened to include social work, nursing, case management, and community outreach. Identify a single provider to maximize consistency.

Obtain a thorough history of the patient's chemical dependency history, practices, needle and syringe source, medical complications of chemical dependency, and treatment history. Nonjudgmental clinical assessment of this information is essential. Nonjudgmental discussion of the adverse health and social consequences of drug use and the benefits of abstinence may increase the patient's understanding of his or her disease and interest in change.

Be aware of pharmacologic drug interactions between HIV and therapies for chemical dependency and provide simplified, low-pill-burden regimens to improve treatment adherence.

Link goals for treatment of HIV and chemical dependency so that success in one arena is linked to improved outcomes in the other.

Establish a relationship of mutual respect. Avoid moral condemnation or attribution of addiction to moral or behavioral weakness. Acknowledge that addiction is a medical disease, compounded by psychologic and social circumstances. As such, it should be treated using evidence-based guidelines with a combination of pharmacologic and behavioral interventions. Reducing or stopping drug use is difficult, as is sustaining abstinence. Success may require several attempts, and relapse is common. Complete abstinence may not be a realistic goal for many substance-misusing patients. Rather, increasing the proportion of days, weeks, and months free from mind-altering substances is an acceptable goal.

Work closely with a drug treatment program.

Define and agree on the roles and responsibilities of both the health care team and the patient. Establish a formal treatment contract that specifies the services to be provided to the patient, the caregiver's expectations about the patient's behavior, and the consequences of behavior that violates the contract. Such a contract should be agreeable to both parties and not simply a contract of the physician's expectations.

Set appropriate limits and respond consistently to behavior that violates those limits. These limits should be imposed in a professional manner that reflects the aim of enhancing patients' well-being, not in an atmosphere of blame or judgment.

Carefully evaluate pain syndromes and provide sufficient analgesia as medically indicated.

Always consider acute substance ingestion when evaluating behavior change and neurologic disease. Use urine toxicology testing to evaluate behavioral changes and to discourage illicit drug use by HIV-infected injection-drug users during hospital stay.

Work consistently as a team. Do not make agreements about treatment decisions until the entire team has become involved. This precaution will avoid “splitting” behaviors that often unravel the fabric of a multi-disciplinary team.

Consider integrating drug treatment into the HIV clinical care settings. Although there are no specific recommendations for accomplishing this goal, a number of key approaches have been described. These approaches include complete integration, in which all clinicians are stakeholders in the treatment of both conditions, the integration of a specialized addiction specialist team, or a hybrid model in which both approaches are implemented [49].

Longitudinal cohort studies conducted during the HAART era have demonstrated that adherence to therapy is the key determinant in HIV disease progression [50–53]. Active drug use has been linked to nonadherence [56,57], and, despite similar rates of HIV disease progression during the pre-HAART era, progression has been reported to be higher among injection drug users than among persons who do not use mind-altering substances in the HAART era [58–61].

HIV-infected injection drug users often are medically and socially marginalized and outside traditional systems of care. They also have high rates of psychiatric comorbidity [54] that can pose problems with adherence to HAART [55].

Directly observed therapy for the treatment of tuberculosis has been remarkably successful in overcoming obstacles commonly encountered in HIV management: maximizing adherence, improving health outcomes, and minimizing the development of resistance [62–64]. The noncurative nature of HIV and the complexity of the regimens have called into question the applicability of directly observed therapy for the treatment of HIV [65,66]. DAART has been demonstrated to be successful in a number of clinical settings, including methadone maintenance treatment programs [67], community outreach programs [68], and mobile health clinics [46]. DAART, however, appears to be more effective when combined with access to and utilization of medical and case management services [69].

Commonly used illicit drugs

Ingestion of any mind-altering substance can be associated with increased HIV risk behaviors. The illicit drugs most closely associated with HIV infection globally are alcohol, heroin and cocaine, but methamphetamine use is an evolving problem. Each of these drugs, with the exception of alcohol, can be administered by a variety of routes. Injection with shared contaminated needles and syringes or other injection paraphernalia carries the greatest risk for HIV transmission and other complications. Noninjection use of cocaine among women [70] and methamphetamine use among men [71], however, increasingly facilitates HIV transmission through risky sexual practices (eg, the exchange of drugs for sex or money). It is important to be aware of local patterns of drug availability and routes of use.

Heroin

There are a number of opioid drugs and medications with abuse potential. Heroin is a short-acting, semisynthetic opioid produced from opium. It may be smoked, inhaled, or injected; peak heroin euphoria begins shortly after injection and lasts approximately 1 hour, followed by 1 to 4 hours of sedation. Withdrawal symptoms commence several hours later. As a consequence, most heroin-dependent individuals inject two to four times per day, though a subset may inject many more times daily. Many heroin users mediate the sedating effects of heroin by injecting a small amount of cocaine with heroin, a mixture known as a “speedball.” The unsterile method of use, unpredictable concentrations in street samples, adulterants in the injection mixture, and the lifestyle necessary to procure drugs are responsible for most heroin-associated medical complications.

Cocaine

Cocaine is available as a water-soluble hydrochloride salt that is injected or taken by nasal inhalation (“snorted”). Although cocaine hydrochloride is destroyed by heat, it may be converted chemically to a free-base (“crack”) cocaine, which can be smoked. Pulmonary absorption of “crack” is as rapid as intravenous injection. Cocaine's half-life is short, resulting in the need for frequent administration. Active cocaine users may inject or inhale cocaine as many as 20 times a day. Cocaine induces feelings of elation, omnipotence, and invincibility, and psychologic dependence develops rapidly. The multiple psychologic and physical effects of cocaine can disrupt clinical care markedly. Programs that are nonjudgmental are essential to continue to engage these patients in care rather than risking losing them to follow-up and diminishing the likelihood of risk reduction intervention.

Methamphetamine

Methamphetamine is a psychostimulant that is similar to amphetamine in chemical structure but has more profound effects on the central nervous system. It can be smoked, snorted, injected, or administered rectally. Like cocaine, methamphetamine ingestion produces stimulation and similar feelings of euphoria; however, methamphetamine has a longer duration of action (6 to 8 hours after a single dose). Tolerance develops rapidly, and escalation of dose and frequency is required. As is the case with cocaine, methamphetamine use is associated with high-risk sexual behavior.

Alcohol

Alcohol is as a central nervous system depressant acutely, and at higher blood levels it functions as a sedative-hypnotic. Alcohol is consumed orally. Tolerance develops with alcohol requiring dose escalation and changes in frequency. Alcohol dependence has been associated with high risk sexual behaviors and alcohol use can diminish or eliminate the effectiveness of many HIV prevention efforts such as condom use and cause significant morbidity and mortality. Unlike the opioids and stimulants, withdrawal from alcohol can lead to seizure and death [72,73,74].

Treatment of chemical dependence

Chemical dependence is a chronic, relapsing, and treatable disease, characterized by compulsive drug-seeking and drug use. Although exposure to addictive substances is widespread in society, high vulnerability to addiction is more limited and is the product of biologic, psychologic, and environmental influences. Thus, identification of addictive disease and referral to or provision of appropriate treatment services is an essential part of the clinical care of HIV-infected patients. Indeed, successful treatment of HIV disease in drug users often requires attention to and treatment of chemical dependence. Although there are a wide variety of treatment modalities, effective treatment has two main components: (1) behavioral therapy (eg, cognitive behavioral therapy, motivational enhancement techniques, etc.) and (2) pharmacologic therapy (eg, opioid substitution therapy). Selection of the appropriate specific treatment plan is an individual decision based in part on the drug used, the length and pattern of the patient's drug use, personal psychosocial characteristics, and local availability and expertise in treatment. Resources are limited in many communities, substantially limiting options for referral.

Treatment of opioid dependence

The most effective treatment for long-term opioid-dependent patients, particularly injection drug users, is opioid substitution therapy [100,101]. The treatment of choice for the patient who is opioid dependent and has HIV disease is long term treatment with an opioid agonist such as methadone or a partial opioid agonist such as buprenorphine [75]. In addition to receiving pharmacological therapy, the patient should be engaged in comprehensive drug treatment services that include evidence-based counseling and social support services such as case management. Agonist treatment of opioid dependence is particularly important for the patient with comorbid HIV infection because effective treatment of opioid dependence enhances HIV treatment, improving health outcomes, and may decrease other risk-taking behaviors [76].

Methadone maintenance has been shown to be effective in decreasing psychosocial and medical morbidity associated with opioid dependence. Furthermore, it improves overall health status and is associated with improved social functioning (eg, decreased criminal activity) in addition to its benefit in decreasing the spread of HIV among injection drug users. Methadone, a semisynthetic, long-acting opioid analgesic, is particularly valuable for its oral bioavailability, long half-life of 24 to 36 hours, and the consistent plasma levels that are obtained with regular administration. A single daily dose is given to maintain stable plasma levels. As a result, tolerance develops, and regular methadone users do not experience the euphoria of the heroin cycle. Drug-seeking behavior decreases, creating the possibility for the development of more constructive behaviors and relationships. In the first 6 months of treatment some patients may experience side effects common to other opiates, but tolerance to the majority of these effects develops rapidly. Persistent side effects include diaphoresis, constipation, and amenorrhea (the majority of women experience the return of menses after 12–18 months of therapy).

There is no optimal dose of methadone for treatment of opioid-dependent patients, who must be assessed individually for treatment response. Generally, doses of 30 to 60 mg daily will block opioid withdrawal symptoms, but higher daily doses in the 80 mg to 120 mg range are needed to reduce opioid craving and decrease illicit drug use. These higher doses also are associated with greater retention in treatment [77].

Buprenorphine, unlike methadone, which is a full agonist, is a partial mu-receptor agonist. As a partial agonist, there is a plateau of its agonist effects at higher doses, improving its safety profile compared with methadone and possibly reducing its likelihood for medication diversion [78]. The plateau includes an upper limit on the severity of side effects associated with overdose, such as respiratory depression [79]. Buprenorphine has a higher binding affinity for the mu-receptor than heroin or methadone, as evidenced by the risk of precipitated withdrawal upon administering buprenorphine [106,107]. Because buprenorphine dissociates slowly from the mu-receptor, alternate-day dosing is possible [80]. Buprenorphine has been prescribed in France since 1996 and has resulted in dramatic improvements in the treatment of opioid dependence there. Buprenorphine was approved for use in the United States in 2002, and population outcome data are still being collected. Worldwide, it is becoming increasingly more available. Unlike methadone, which is delivered in a highly structured setting and with limited slots in a minority of communities, buprenorphine can be prescribed by any physician who has completed 8 hours of specified training and is an option for integrating opioid substitution into HIV clinical care settings [22].

Naltrexone, a long-acting, pure opiate antagonist that competitively inhibits the euphoric effects of opiates, has been in use for the treatment of opioid dependence for decades [81]. A typical naltrexone regimen is 100 mg Monday and Wednesday and 150 mg on Friday, although 50 mg daily and 100/150 mg twice weekly have been studied also [82]. Treatment initiation generally requires an effective supervised medical withdrawal from opioids for at least 5 to 7 days before treatment initiation to prevent the precipitation of severe withdrawal. The efficacy and safety of naltrexone for the treatment of opiate dependence has been demonstrated in several randomized, controlled clinical trials [83].

The major strength of this medication is that there are no opiate-related side effects, no overdose risk, no negative consequences on cessation (eg, withdrawal), and no possibility for diversion. Additionally, naltrexone has some beneficial effects in the treatment of moderate alcoholism [84,85], a common comorbid condition among opiate users. Naltrexone's effectiveness has been disappointing and hampered by decreased adherence because, unlike methadone, there is no negative reinforcement for discontinuation (ie, opioid withdrawal). Hence, the effectiveness of naltrexone depends heavily on the motivation and social support system of the patient [86]. The development of a monthly depo-formulation of naltrexone may improve adherence, and studies to re-evaluate naltrexone as a treatment of opioid dependence should be conducted in populations with differing levels of adherence.

Regardless of the specific treatment, HIV-infected chemically dependent patients must have as part of their treatment plan evidence-based approaches to both behavioral and pharmacologic therapies so that appropriate and adequate treatment for addiction can result in improvements in the psychologic and physiologic disruptions that perpetuate the often unstable life of a chemically dependent person.

Treatment for cocaine and methamphetamine dependence

Unlike the case for treatment of opioid dependence, no medications have been approved by the Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of stimulant dependence. Extensive investigation, however, has examined various behavioral and pharmacologic treatments for cocaine dependence [87]. Several studies have pointed to disulfiram as a potential pharmacologic agent [108–112]. Although evidence is encouraging, the use of this medication is still investigational. Other medications actively being investigated include tiagabine [113–116], topiramate [117,118], modafinil [119–122], and several other agents. Although these pharmacological agents appear promising, HIV clinical providers should seek the assistance of addiction medicine experts before starting any pharmacological therapy for the treatment of cocaine dependence. The lack of successful, standardized treatment strategies for stimulant users is a significant problem as the epidemics of cocaine and methamphetamine use grow. In the absence of effective programs to treat stimulant use, HIV care providers may feel helpless and frustrated. Counseling is the only treatment modality widely accepted based on the evidence to decrease use of cocaine and methamphetamine [88]. As a result, referral to a substance abuse treatment program, if available, is essential.

Treatment for alcohol dependence

Compared to opiate dependence, the neurobiology of alcohol dependence does not lend itself well to a substitution strategy. As such, treatment for alcohol dependence centers on reducing problematic drinking and relapse prevention through the pharmacological attenuation of relapse in the case of acamprosate or naltrexone, and the aversive response with relapse in the case of disulfiram. In the few well controlled studies of disulfiram, it appears to be of similar benefit to placebo [123]. In clinical trials, naltrexone has demonstrated superiority over acamprosate [124]. A new depot formulation of naltrexone may assist in improving adherence to treatment and, consequently, clinical outcomes. Its use, however, in the setting of patients with HCV infection, hepatic dysfunction and hepatic transaminase elevations has not been thoroughly investigated.

Mental illness and illicit drug use

The prevalence of mental illness among HIV-infected patients approaches 50% [125]. Among users of heroin, cocaine and alcohol, the prevalence of co-occurring mental illness is several-fold higher than the general population. It is therefore no surprise that co-occurring psychiatric illness among HIV-infected drug users is highly prevalent and complicates treatment for many conditions. Psychiatric conditions commonly manifest around the time of HIV diagnosis [125], but many patients develop symptoms later in their course of illness [126]. Anxiety and depression are particularly likely to become clinically evident at times of stress—including an illness episode, a psychosocial stressor such as divorce or loss of a loved one, and when facing a new disability. Anxiety and depression are among the most commonly diagnosed psychiatric conditions affecting HIV-infected patients [127,128]. These can complicate the treatment of HIV, presenting numerous diagnostic and interventional challenges for the clinician [129].

Adherence to highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) and to effective drug treatment can be markedly reduced by the presence of co-occurring psychiatric disorders, but proper treatment of the psychiatric disorder can reverse this effect [88,130]. The appropriate evaluation and treatment of psychiatric symptoms can significantly affect a patient's quality-of-life, as well as the risk of relapse into injection drug use and willingness to return for medical care [131]. Undiagnosed and untreated mental illness may lead to increased HIV risk behaviors and therefore contribute to the acquisition and transmission of HIV [132,133]. Therefore, routine and standardized screening for mental illness should be part of the clinical standard for managing HIV-infected drug users.

A small, but critical minority of patients experience HIV/AIDS, chemical dependency and mental illness. These three complex, overlapping spheres of illness adversely influence each other and the overall clinical outcomes of the affected individual [1]. The challenge to treating these “triple diagnosis” patients is the current non-integrated healthcare system approach where it is often required that one condition be addressed independently from the other [3,4].

A thorough discussion of mental illness as it relates to substance misuse and HIV is outside the scope of this review. It must be noted, however, that substance misuse and mental illness are closely interrelated with HIV. Individuals with all three diagnoses are likely to engage in high-risk behaviors [89], and when untreated, continue to fuel the HIV epidemic resulting in continuing transmission of HIV. These three diagnoses should be viewed as overlapping spheres of influence, with each diagnosis affecting the other. Conceptually this is important because successful therapy requires screening, diagnosis and treatment of all three spheres of influence rather than ignoring any one single area [1]. For this reason, it is essential to ensure a comprehensive and integrated approach to managing these three co-morbid conditions. Several recent reviews have addressed the management of mental health issues of these complex patients [2,3].

Drug interactions with HIV therapies

Clinicians who care for HIV-infected chemically dependent patients must be familiar with the significant interactions between pharmacological therapies for chemical dependence and HIV therapies (summarized in Table 2) [103]. This understanding is critical as opioid substitution therapy may alter metabolism of antiretroviral medications resulting in increased toxicity or reduced efficacy. Alternatively, antiretroviral medications may alter the levels of opioid substitution therapy resulting in clinical opiate withdrawal or overdose. The pharmacological and pharmacodynamic interactions of methadone and buprenorphine with HIV therapies have been reviewed extensively elsewhere [96,105]. The key interactions applicable to clinicians are summarized here.

Table 2.

Interactions between antiretroviral agents and methadone and buprenorphine

| Medication | Effect on methadonea | Effect on buprenorphinea | Antiretroviral (ARV) | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors | ||||

| Abacavir (ABC) | ↑clearance | Not studied | ↓Cmax | Unclear if ↑ in methadone clearance is caused by ABC; ↓ Cmax not clinically relevant |

| Didanosine (ddI) | No effect | Not studied | ↓ ddI AUC by 57% for buffered tablet partially corrected by enteric-coated capsule to within range in historical controls | Enteric-coated capsule recommended for methadone patients |

| Emtriva (FTC) | Not studied | Not studied | Not studied | |

| Lamivudine (3TC) | No effect | Not studied | Not studied | Only AZT/ lamivudine coformulation studied |

| Stavudine (d4T) | No effect | Not studied | ↓ d4T AUC12 h by 23% and Cmax by 44% | Changes unlikely to be clinically significant |

| Tenofovir (TDF) | No effect | Not studied | Not studied | |

| Zalcitabine (ddC) | Not studied | Not studied | Not studied | |

| Zidovudine (AZT) | No effect | No effect | Methadone ↑ AZT AUC by 40% | Watch for AZT-related toxicity in methadone-maintained patients (symptoms and laboratory) |

| Non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors | ||||

| Delavirdine (DLV) | ↑ AUC by 19%;

↑ Cmax by 10% |

> fourfold ↑ in buprenorphine AUC, but without clinical effect | No effect by either buprenorphine or methadone | Probably not clinically relevant but should be used with caution because long-term effects (> 7 days) unknown |

| Efavirenz (EFV) | Significant effect: mean ↓ in methadone AUC by 57% | ↓ in AUC of buprenorphine by 50%, but no clinical effect | No effect by either buprenorphine or methadone | Opiate withdrawal common; methadone dose ↑ necessary |

| Nevirapine (NVP) | Significant effect: mean ↓ in methadone AUC by 46% | Not studied | No effect from methadone | Opiate withdrawal common; methadone dose ↑ necessary |

| Protease inhibitors | ||||

| Amprenavir (AMP) | ↓ AUC of R-methadone by 13% | Not studied | ↓ AUC by 30% | Decreases in AUC do not seem to be clinically significant |

| Atazanavir (ATV) | No effect | Questionable oversedation | No effect | No dose adjustments necessary for methadone; consider slower titration in buprenorphine |

| Fosamprenavir (fAMP) | Not studied | Not studied | Not studied | As a prodrug of amprenavir, will likely have the same interactions for amprenavir |

| Indinavir (IND) | No effect | Not studied | ↓ Cmax 16%–28% and ↑ Cmin 50%–100% | Differences do not seem to be clinically significant |

| Lopinavir/ritonavir (LPV/r) | ↓ AUC by 26%–36% | No clinical effect | Buprenorphine increased lopinavir AUC by 16% | ↓ AUC of methadone caused by lopinavir; one study reported opioid withdrawal symptoms in 27% of patients; methadone dose ↑ may be necessary in some patients |

| Nelfinavir | ↓ AUC by 40% | No significant clinical effect | ↓ AUC of active M8 metabolite by 48% in methadone; no changes in NFV of M8 were observed | Despite ↓ methadone AUC, clinical withdrawal is usually absent and a priori dosage adjustments are not needed; decrease in AUC of M8 unlikely to be clinically significant; TDM may be useful in patients with good adherence and virologic failure |

| Ritonavir (RTV) | ↓ AUC by 37% in one study and no effect in another (see text) | ↑ AUC by 57% without clinical effect of oversedation | Buprenorphine had no effect on RTV pharmacokinetics | No dosage adjustment |

| Saquinavir (SQV) | ↓ AUC by 20%–32% | Not studied | Not studied | Saquinavir boosted with ritonavir studied; despite ↓ methadone AUC, clinical withdrawal was not reported |

| Tipranavir (TPV) | ↓ methadone by 50%b | Not studied | Not reported | Methadone may need to be increased |

Abbreviations: AUC, area under curve; Cmax, maximal clearance; TDM, therapeutic drug monitoring; ↓, decrease;↑, increase.

See text for references.

Decrease in methadone not specified as AUC or Cmax.

Adapted from Bruce RD, Altice FL, Gourevitch MN, et al. Pharmacokinetic drug interactions between opioid agonist therapy and antiretroviral medications: implications and management for clinical practice. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2006;41(5):563–72.

The currently approved nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NRTIs) do not affect methadone levels in a clinically significant manner and therefore do not precipitate opioid withdrawal. Methadone, however, affects the pharmacokinetics of two NRTIs. Methadone increases zidovudine drug levels by approximately 40% [90]. As a result, patients may experience symptoms associated with excessive zidovudine dosing that may be confused with symptoms of opiate withdrawal such as headache, abdominal pain, myalgias, fatigue, and irritability. In addition, increased zidovudine levels may result in laboratory abnormalities, such as anemia and hepatitis. Buprenorphine does not alter the pharmacokinetics of zidovudine in a clinically meaningful manner, however. Methadone decreases the levels of the buffered table formulation of didanosine by 66%; this level of decrease is of clinical concern, and the two drugs should not be coadministered. The newer, enteric-coated formulation seems to have corrected this problem and is the preferred formulation when methadone and didanosine are coadministered [91]. The decrease in didanosine is postulated to be the result of a slowing of gastric motility. Because the decrese in gastric motility is a nonspecific opioid effect, patients taking buprenorphine should avoid taking buffered didanosine and should take the enteric-coated capsule.

Nevirapine, a non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor (NNRTI), was the first antiretroviral medication described that precipitated opiate withdrawal [92]. Another NNRTI, efavirenz, also markedly reduces methadone levels and precipitates clinical opiate withdrawal [93]. Both NNRTIs seem to exert their effect through marked induction of cytochrome P450 isoenzymes. Although efavirenz significantly reduces buprenorphine levels, preliminary studies indicate that this reduction is not associated with symptoms of opioid withdrawal [94].

Most protease inhibitors do not seem to have clinically meaningful effects on methadone levels. The package insert for tipranavir reports that standard dosing of tipranavir/ritonavir (500/200 mg twice daily) may result in a decrease in methadone levels, requiring an increase in methadone dose; however, no adverse events have been reported in the literature [95]. To date nelfinavir, lopinavir/ritonavir, and ritonavir alone have been studied with buprenorphine without evidence of a clinically meaningful interaction [96]. One case report in the literature suggested the possibility that atazanavir and buprenorphine may result in oversedation in some patients [97].

Several medications used to treat or prevent opportunistic infections in HIV-infected individuals deserve brief comment. Rifampin, a potent inducer of cytochrome P450, produces rapid and profound reductions in methadone levels and development of opioid withdrawal; as such, rifampin should be changed to rifabutin or methadone doses should be increased rapidly and dramatically to avoid opioid withdrawal and discontinuation of all medications [98]. Fluconazole, a known inhibitor of cytochrome P450 metabolism, increases methadone exposure, and methadone dosage may need to be reduced [99].

Special issues in prevention

Risk reduction

The relapsing pattern of drug use and the wide array of serious infectious and other medical consequences require the development of preventive risk-reduction strategies. Risk reduction does not promote injection drug use but seeks to decrease the frequency of adverse events that are related to this practice. Risk reduction is based on the underlying principle that injection drug use is a chronic and relapsing disease which may not be cured in the individual or eliminated from society but can be conducted in a way that minimizes harm to the user and others. Although complete cessation of drug use remains a laudable goal, reduction in drug use frequency and safer injection practices are more realistic for many drug users until abstinence can be achieved. Risk-reduction strategies have been incorporated effectively into some drug treatment programs, syringe-exchange programs, and safe injection rooms [100,101]. There are several practical components inherent to risk-reduction strategies. Education about and provision of drug use paraphernalia (eg, needles and syringes) for more hygienic injection practices are essential for the prevention of infectious complications of injection. In addition to the distribution or exchange of injection equipment, these programs typically include HIV/AIDS education, condom distribution, and referral to or enrollment in a variety of drug treatment, medical, and social services [102]. Specifically, some programs provide on-site medical and drug treatment, reducing emergency department use by injection drug users [45].

Provision of primary medical care services linked to drug-abuse treatment is a way to promote preventive therapies to enhance harm reduction. In this and all other clinical settings, in addition to the treatment of HIV disease and prevention of complications, injection drug users should be routinely screened for hepatitis B and C, latent M tuberculosis infection, syphilis, and other sexually transmitted disease. They should be offered pneumococcal, influenza, tetanus, and hepatitis A and B immunization and (when appropriate) prophylaxis for tuberculosis.

The ultimate goal of risk-reduction strategies should be the reduction or prevention of illicit drug use itself, the development of strategies that will minimize the serious medical consequences of drug misuse, and the development of strategies that will eliminate drug misuse and its root causes. Without success in this arena, there is little chance of limiting the spread and consequences of HIV disease in this and related populations.

Physicians and other clinical providers also may play a role in secondary HIV prevention. Brief interventions, of 5 minutes or less and delivered by the clinician at the HIV clinical appointment, have been associated with a reduction in HIV risk behaviors compared with a control group [95]. This intervention is predicated on the information, motivation, and behavioral skills model of behavior change and employs elements of motivational interviewing. Delivering such interventions, however, requires that clinicians receive adequate training in the implementation of the intervention. Other interventions targeting HIV-infected drug users have been implemented successfully in methadone and other drug treatment settings and have reduced both sexually and injection-related risks of contracting HIV.

Last, clinicians play an additional important role in prevention among injection drug users [104]. For active drug users, they can legally prescribe syringes for the prevention of HIV/AIDS so that their patients have adequate sterile injection equipment to avoid transmitting HIV to others or becoming infected with other blood-borne infections. They also can prescribe male and female condoms to prevent HIV transmission and acquisition of sexually transmitted infections. Prescription of syringes and condoms does not promote risky behavior. Instead, it reflects concern by the clinician for the patient without condemning the behavior. In the case of prescribed syringes, it signals to the patient that the clinician, although advocating drug treatment to improve the health of the patient, supports the patient in remaining healthy until such help can be obtained. This message is particularly important where extensive waiting lists for treatment exist or where resources are not readily available.

Acknowledgments

The authors' clinical and research efforts have been funded by the National Institute on Drug Abuse (RDB–K23 DA 022143; FLA-K24 DA 017072) and the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Agency (H79 TI 15767)

References

- 1.Bruce RD, Altice FL. Why treat three conditions when it is one patient? AIDS Read. 2003;13(8):378–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Altice F, Friedland GH. Epidemiology of HIV infection and AIDS: past, present, and future. Disease Management and Health Outcomes. 1997;1(6):304–22. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Douaihy AB, Jou RJ, Gorske T, et al. Triple diagnosis: dual diagnosis and HIV disease, part 2. AIDS Reader. 2003;13(8):375–82. see comment. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Douaihy AB, Jou RJ, Gorske T, et al. Triple diagnosis: dual diagnosis and HIV disease, Part 1. AIDS Reader. 2003;13(7):331–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Risk behaviors for HIV transmission among intravenous-drug users not in drug treatment–United States, 1987–1989. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1990;39(16):273–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Battjes RJ, Pickens RW, Amsel Z. HIV infection and AIDS risk behaviors among intravenous drug users entering methadone treatment in selected U.S. cities. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 1991;4(11):1148–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stark K, Muller R, Guggenmoos-Holzmann I, et al. HIV infection in intravenous drug abusers in Berlin: risk factors and time trends. Klin Wochenschr. 1990;68(8):415–20. doi: 10.1007/BF01648583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Loimer N, Werner E, Presslich O. Sharing spoons: a risk factor for HIV-1 infection in Vienna. Br J Addict. 1991;86(6):775–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1991.tb03103.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hall W, Darke S, Ross M, et al. Patterns of drug use and risk-taking among injecting amphetamine and opioid drug users in Sydney, Australia. Addiction. 1993;88(4):509–16. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1993.tb02057.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Abdala N, Carney JM, Durante AJ, et al. Estimating the prevalence of syringe-borne and sexually transmitted diseases among injection drug users in St Petersburg, Russia. Int J STD & AIDS. 2003;14(10):697–703. doi: 10.1258/095646203322387965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kelly JA, Amirkhanian YA. The newest epidemic: a review of HIV/AIDS in Central and Eastern Europe. Int J STD & AIDS. 2003;14(6):361–71. doi: 10.1258/095646203765371231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Saelim A, Geater A, Chongsuvivatwong V, et al. Needle sharing and high-risk sexual behaviors among IV drug users in Southern Thailand. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 1998;12(9):707–13. doi: 10.1089/apc.1998.12.707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Caiaffa WT, Proietti FA, Carneiro-Proietti AB, et al. The dynamics of the human immunodeficiency virus epidemics in the south of Brazil: increasing role of injection drug users. Clin Infect Dis. 2003;37 5:S376–81. doi: 10.1086/377555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhang C, Yang R, Xia X, et al. High prevalence of HIV-1 and hepatitis C virus coinfection among injection drug users in the southeastern region of Yunnan, China. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2002;29(2):191–6. doi: 10.1097/00042560-200202010-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bing EG, Burnam MA, Longshore D, et al. Psychiatric disorders and drug use among human immunodeficiency virus-infected adults in the United States. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2001;58(8):721–8. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.58.8.721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fulk LJ, Kane BE, Phillips KD, et al. Depression in HIV-infected patients: allopathic, complementary, and alternative treatments. J Psychosom Res. 2004;57(4):339–51. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2004.02.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Maj M, Satz P, Janssen R, et al. WHO neuropsychiatric AIDS study, cross-sectional phase II. Neuropsychological and neurological findings. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1994;51(1):51. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1994.03950010051007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Elliott A. Anxiety and HIV infection. STEP perspect. 1998;98(1):11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kerr T, Wodak A, Elliott R, et al. Opioid substitution and HIV/AIDS treatment and prevention. Lancet. 2004;364(9449):1918–9. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17490-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Doran CM, Shanahan M, Mattick RP, et al. Buprenorphine versus methadone maintenance: a cost-effectiveness analysis. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2003;71(3):295–302. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(03)00169-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Substitution maintenance therapy in the management of opioid dependence and HIV/AIDS prevention: position paper. WHO, UNODC, UNAIDS; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Altice FL, Sullivan LE, Smith-Rohrberg D, et al. The potential role of buprenorphine in the treatment of opioid dependence in HIV-infected individuals and in HIV infection prevention. Clin Infect Dis. 2006 Dec 15;43 4:S178–83. doi: 10.1086/508181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Alcabes P, Friedland GH. Injection drug use and human immunodeficiency virus infection. Clin Infect Dis. 1995;20(6):1467–79. doi: 10.1093/clinids/20.6.1467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pascual FB, McGinley EL, Zanardi LR, et al. Tetanus surveillance–United States, 1998–2000. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep Surveill Summ. 2003;52(3):1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gielen AC, McDonnell KA, Wu AW, et al. Quality of life among women living with HIV: the importance violence, social support, and self care behaviors. Soc Sci Med. 2001;52(2):315–22. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(00)00135-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bratu S, Landman D, Gupta J, et al. A population-based study examining the emergence of community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus USA300 in New York City. Annals of Clinical Microbiology & Antimicrobials. 2006;5:29. doi: 10.1186/1476-0711-5-29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Crum NF, Lee RU, Thornton SA, et al. Fifteen-year study of the changing epidemiology of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. American Journal of Medicine. 2006;119(11):943–51. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2006.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Wound botulism among black tar heroin users–Washington, 2003. MMWR - Morbidity & Mortality Weekly Report. 2003;52(37):885–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Anderson MW, Sharma K, Feeney CW. Wound botulism associated with black tar heroin. Academic Emergency Medicine. 1997;4(8):805–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.1997.tb03790.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wells R, Fisher D, Fenaughty A, et al. Hepatitis A prevalence among injection drug users. Clin Lab Sci. 2006;19(1):12–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Trpin S, Gracner T, Pahor D. Phacoemulsification in isolated endogenous Candida albicans anterior uveitis with lens abscess in an intravenous methadone user. Journal of Cataract & Refractive Surgery. 2006;32(9):1581–3. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrs.2006.03.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Miller DJ, Mejicano GC. Vertebral osteomyelitis due to Candida species: case report and literature review. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2001;33(4):523–30. doi: 10.1086/322634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mocroft A, Ledergerber B, Katlama C, et al. Decline in the AIDS and death rates in the EuroSIDA study: an observational study. Lancet. 2003;362(9377):22–9. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(03)13802-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gebo KA, Diener-West M, Moore RD. Hospitalization rates in an urban cohort after the introduction of highly active antiretroviral therapy. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2001;27(2):143–52. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200106010-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Anis AH, Guh D, Hogg RS, et al. The cost effectiveness of antiretroviral regimens for the treatment of HIV/AIDS. Pharmacoeconomics. 2000;18(4):393–404. doi: 10.2165/00019053-200018040-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.van Asten LC, Boufassa F, Schiffer V, et al. Limited effect of highly active antiretroviral therapy among HIV-positive injecting drug users on the population level. Eur J Public Health. 2003;13(4):347–9. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/13.4.347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bakir AA, Dunea G, et al. Renal disease in the inner city. Seminars in Nephrology. 2001;21(4):334–45. doi: 10.1053/snep.2001.23690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Perneger TV, Klag MJ, Whelton PK. Recreational drug use: a neglected risk factor for end-stage renal disease. American Journal of Kidney Diseases. 2001;38(1):49–56. doi: 10.1053/ajkd.2001.25181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Crowe AV, Howse M, Bell GM, et al. Substance abuse and the kidney. Qjm. 2000;93(3):147–52. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/93.3.147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gandhi NR, Moll A, Sturm AW, et al. Extensively drug-resistant tuberculosis as a cause of death in patients co-infected with tuberculosis and HIV in a rural area of South Africa. Lancet. 2006;368(9547):1575–80. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69573-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Altice FL, Mostashari F, Friedland GH. Trust and the acceptance of and adherence to antiretroviral therapy. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2001;28(1):47–58. doi: 10.1097/00042560-200109010-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jittiwutikarn J, Thongsawat S, Suriyanon V, et al. Hepatitis C infection among drug users in northern Thailand. American Journal of Tropical Medicine & Hygiene. 2006;74(6):1111–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Prevalence and correlates of hepatitis C infection among users of North America's first medically supervised safer injection facility. Public Health. 2005;119(12):1111–5. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2005.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Altice FL, Springer S, Buitrago M, et al. Pilot study to enhance HIV care using needle exchange-based health services for out-of-treatment injecting drug users. J Urban Health. 2003;80(3):416–27. doi: 10.1093/jurban/jtg053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pollack HA, Khoshnood K, Blankenship KM, et al. The impact of needle exchange-based health services on emergency department use. J Gen Intern Med. 2002;17(5):341–8. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2002.10663.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Jamal MM, Saadi Z, Morgan TR. Alcohol and hepatitis C. Digestive Diseases. 2005;23(3–4):285–96. doi: 10.1159/000090176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.de Torres M, Poynard T. Risk factors for liver fibrosis progression in patients with chronic hepatitis C. Annals of Hepatology. 2003;2(1):5–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jamal MM, Morgan TR. Liver disease in alcohol and hepatitis C. Best Practice & Research in Clinical Gastroenterology. 2003;17(4):649–62. doi: 10.1016/s1521-6918(03)00018-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Dettmeyer RB, Preuss J, Wollersen H, et al. Heroin-associated nephropathy. Expert Opinion on Drug Safety. 2005;4(1):19–28. doi: 10.1517/14740338.4.1.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.do Sameiro Faria M, Sampaio S, Faria V, et al. Nephropathy associated with heroin abuse in Caucasian patients. Nephrology Dialysis Transplantation. 2003;18(11):2308–13. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfg369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bakir AA, Dunea G. Drugs of abuse and renal disease. Current Opinion in Nephrology & Hypertension. 1996;5(2):122–6. doi: 10.1097/00041552-199603000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Naicker S, Han TM, Fabian J. HIV/AIDS–dominant player in chronic kidney disease. Ethnicity & Disease. 2006;16(2) 2:S2-56–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ross MJ, Klotman PE, Winston JA. HIV-associated nephropathy: case study and review of the literature. AIDS Patient Care & Stds. 2000;14(12):637–45. doi: 10.1089/10872910050206559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Dunfee R, Thomas ER, Gorry PR, et al. Mechanisms of HIV-1 neurotropism. Current HIV Research. 2006;4(3):267–78. doi: 10.2174/157016206777709500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Letendre S, Ellis RJ. Neurologic complications of HIV disease and their treatments. Topics in HIV Medicine. 2006;14(1):21–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Waldrop-Valverde D, Ownby RL, Wilkie FL, et al. Neurocognitive aspects of medication adherence in HIV-positive injecting drug users. AIDS & Behavior. 2006;10(3):287–97. doi: 10.1007/s10461-005-9062-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Gonzalez R, Jacobus J, Martin EM. Investigating neurocognitive features of hepatitis C virus infection in drug users: potential challenges and lessons learned from the HIV literature. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2005;41 1:S45–9. doi: 10.1086/429495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Libman H, Saitz R, Nunes D, et al. Hepatitis C infection is associated with depressive symptoms in HIV-infected adults with alcohol problems. American Journal of Gastroenterology. 2006;101(8):1804–10. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2006.00616.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Soogoor M, Lynn HS, Donfield SM, et al. Hepatitis C virus infection and neurocognitive function. Neurology. 2006;67(8):1482–5. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000240255.42608.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Basu S, Bruce RD, Barry DT, et al. Pharmacological Pain Control for HIV-Infected Adults With a History of Drug Dependence. J Substance Abuse Treatment. 2007 doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2006.10.005. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Poundstone KE, Chaisson RE, Moore RD. Differences in HIV disease progression by injection drug use and by sex in the era of highly active antiretroviral therapy. AIDS. 2001;15(9):1115–23. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200106150-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Chaulk CP, Kazandjian VA. Directly observed therapy for treatment completion of pulmonary tuberculosis: consensus statement of the Public Health Tuberculosis Guidelines Panel. JAMA. 1998;279(12):943–8. doi: 10.1001/jama.279.12.943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Chaulk CP, Moore-Rice K, Rizzo R, et al. Eleven years of community-based directly observed therapy for tuberculosis. JAMA. 1995;274(12):945–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Weis SE, Slocum PC, Blais FX, et al. The effect of directly observed therapy on the rates of drug resistance and relapse in tuberculosis. N Engl J Med. 1994;330(17):1179–84. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199404283301702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Mitty JA, Stone VE, Sands M, et al. Directly observed therapy for the treatment of people with human immunodeficiency virus infection: a work in progress. Clin Infect Dis. 2002;34(7):984–90. doi: 10.1086/339447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Mateu-Gelabert P, Maslow C, Flom PL, Sandoval M, Bolyard M, Friedman SR. Keeping it together: stigma, response, and perception of risk in relationships between drug injectors and crack smokers, and other community residents. AIDS Care. 2005;17(7):802–13. doi: 10.1080/09540120500100486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kaplan AH, Scheyett A, Golin CE. HIV and stigma: analysis and research program. Current HIV/AIDS Reports. 2005;2(4):184–8. doi: 10.1007/s11904-005-0014-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Mitty J, Macalino GE, Bazeman LB, et al. The use of community-based modified directly observed therapy for the treatment of HIV-infected persons. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2005;39(5):545–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Smith-Rohrberg D, Mezger J, Walton M, et al. Impact of enhanced services on virologic outcomes in a directly administered antiretroviral therapy trial for HIV-infected drug users. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes: JAIDS. 2006;43 1:S48–53. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000248338.74943.85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Feist-Price S, Logan TK, Leukefeld C, et al. Targeting HIV prevention on African American crack and injecting drug users. Subst Use Misuse. 2003;38(9):1259–84. doi: 10.1081/ja-120018483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Urbina A, Jones K. Crystal methamphetamine, its analogues, and HIV infection: medical and psychiatric aspects of a new epidemic. Clin Infect Dis. 2004;38(6):890–4. doi: 10.1086/381975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Malow RM, Devieux JG, Rosenberg R, et al. Alcohol use severity and HIV sexual risk among juvenile offenders. Substance Use & Misuse. 2006;41(13):1769–88. doi: 10.1080/10826080601006474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]