Abstract

A pattern of male-biased mutation has been found in a wide range of species. The standard explanation for this bias is that there are greater numbers of mitotic cell divisions in the history of the average sperm, compared to the average egg, and that mutations typically result from errors made during replication. However, this fails to provide an ultimate evolutionary explanation for why the male germline would tolerate more mutations that are typically deleterious. One possibility is that if there is a tradeoff between producing large numbers of sperm and expending energetic resources in maintaining a lower mutation rate, sperm competition would select for males that produce larger numbers of sperm despite a higher resulting mutation rate. Here I describe a model that jointly considers the fitness consequences of deleterious mutation and mating success in the face of sperm competition. I show that a moderate level of sperm competition can account for the observation that the male germline tolerates a higher mutation rate than the female germline.

Keywords: sexual selection, sperm competition, male-biased mutation, male-driven evolution

Higher rates of mutation in the male germline, relative to the female germline, have been found in primates (Makova and Li 2002; Shimmin et al. 1993), rodents (Chang et al. 1994), cats (Pecon Slattery and O’Brien 1998), birds (Ellegren and Fridolfsson 1997), fish (Ellegren and Fridolfsson 2003), Arabidopsis (Whittle and Johnston 2003) and gymnosperms (Whittle and Johnston 2002). The primary explanation for the observed male-biased mutation rate is that DNA replication is mutagenic and that the average sperm contributing to each generation will have gone through more cell divisions than the average egg (Miyata et al. 1987). This has led to the observation that the strength of the male mutation bias scales with generation time (Chang et al. 1994). However, while increased generation time can provide an explanation for the magnitude of the male mutation bias, it is unable to provide an explanation for the existence of male biased mutation in the first place. Furthermore, this explanation is not sufficient to explain male-biased mutation for classes of mutation that are likely independent of DNA replication. For example, a male bias has been observed in Arabidopsis for the transmission of mutations that arise from UV irradiation (Whittle and Johnston 2003). Secondly, a weak male-biased mutation rate has also been found at primate CpG sites where mutations typically result from replication independent deamination of methylated cytosines (Taylor et al. 2006). Thirdly, in Drosophila, mutagenic transposons are often transmitted paternally in an active state but maternally in a repressed state (Bingham et al. 1982; Bucheton et al. 1984; Evgenev et al. 1997; Vieira et al. 1998; Yannopoulos et al. 1987). Thus, while replication dependent DNA damage provides an important mechanistic explanation for much of the male mutation bias, it fails to provide a broader evolutionary explanation for why the male germline would tolerate a greater mutation rate since most mutations are deleterious.

It has been posited verbally, and there is some evidence in birds, that sperm competition may select for large numbers of sperm (Bartosch-Harlid et al. 2003; Hurst and Ellegren 1998) despite the consequence of a higher male mutation rate. However, it is not clear to what extent sperm competition could be a general explanation for the male-biased mutation rate. Here I develop a model that explicitly tests this hypothesis. First, is the level of sperm competition required for this to be true consistent with what might be expected in nature? Secondly, to what degree is this result dependent on realistic parameter estimates such as the selection coefficient for deleterious mutations? To answer these questions, one must consider both the effects of natural selection on fecundity and the long-term consequences of modifiers of the mutation rate. Here I develop a model that considers these fitness consequences jointly. Typically, models of sperm competition do not account for the fitness consequences of the mutation rate, despite the fact that sperm function to transmit genetic material. I show that, in fact, only a very moderate level of sperm competition is sufficient to result in a male-biased mutation rate. Furthermore, this result is robust to a very wide range of parameter estimates. While other factors certainly contribute, these results suggest that sperm competition may have important consequences for sexual dimorphism in the mutation rate.

MODEL AND RESULTS

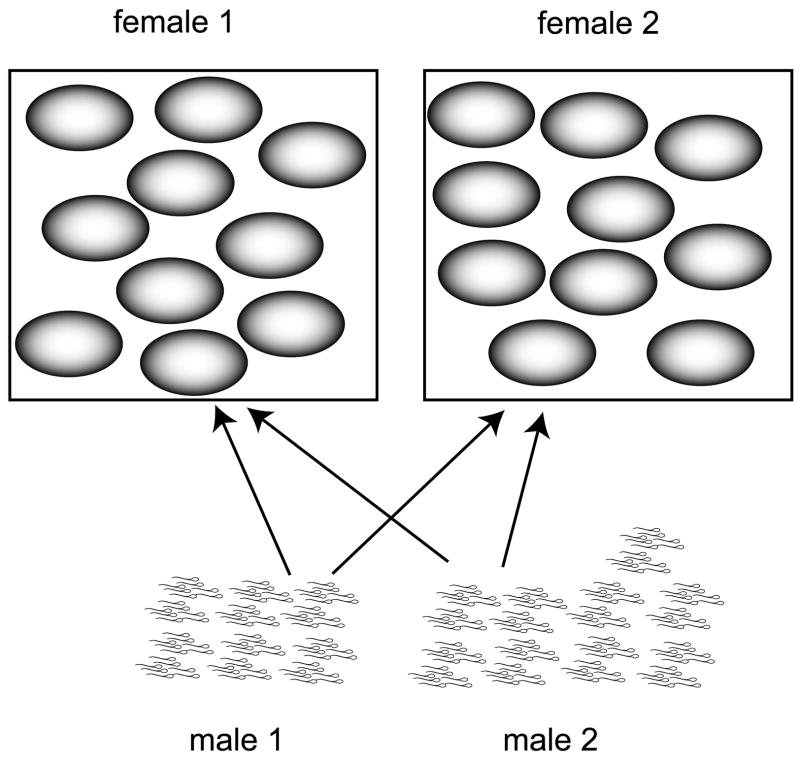

In this model, I jointly consider the effects of selection for reproductive success and against deleterious mutations arising from a modifier of the mutation rate. Considering these two factors, I then determine optimal male and female mutation rates and the ratio of the two. The basic premise of the model is that under sperm competition, eggs are limiting. Thus, while female fitness is in part a function of egg number, male fitness is a function of success in securing eggs under sperm competition. In the model, I also incorporate a tradeoff between the number of gametes produced and the mutation rate. Thus, production of larger gamete number comes at the cost of a higher mutation rate, due to limited energetic resources that can either be allocated to producing more gametes or maintaining a lower mutation rate. For simplicity, I determine male reproductive success only in terms of the number of sperm produced. Thus, other aspects of sexual selection, such as premating competition between males for access to females, are not considered and costs to maintaining a given mutation are specific to gametogenesis. This simplification excludes other aspects of sexual selection such as female choice but it allows one to consider the effects of sperm competition in isolation. In this context, I aim to determine the degree to which sperm competition can drive the production of large numbers of sperm in the face of a higher male mutation rate. The basic scheme of the model is illustrated in Figure 1.

Fig 1.

An example of the model. Here, total energetic resources, E, allocated to gamete production for males and females, equals 100,000. Thus, a female that contributes 9,999 units per egg (I=9,999) and contributes an additional 1 unit (Cuf=1) per egg toward maintaining a given mutation rate produces a total of 10 eggs. In the case of β = 1 and ε = 1, the cost function Cuf = β/uε gives a per gamete female mutation rate of 1. In the case of males, the male on the left may produce 50,000 sperm, each one costing 1 unit of gamete costs and 1 unit of mutational costs. Given the same amount of resources allocated toward maintaining a low mutation rate as the female, such a male will have the same mutation rate as the female. However, another male that produces 75,000 sperm will have a greater chance of securing the female gametes, but will only have enough remaining energetic resources to contribute 1/3 of a unit per gamete to maintaining a lower mutation rate. Given the cost function, the mutation rate per gamete in this male will be 3. In this diagram, z, the number of ejaculates that compete, equals 2. Arrows indicate a single mating. Note, since the number of male and female matings must be the same when the sex ratio is 1:1, each female mates twice and each male mates twice.

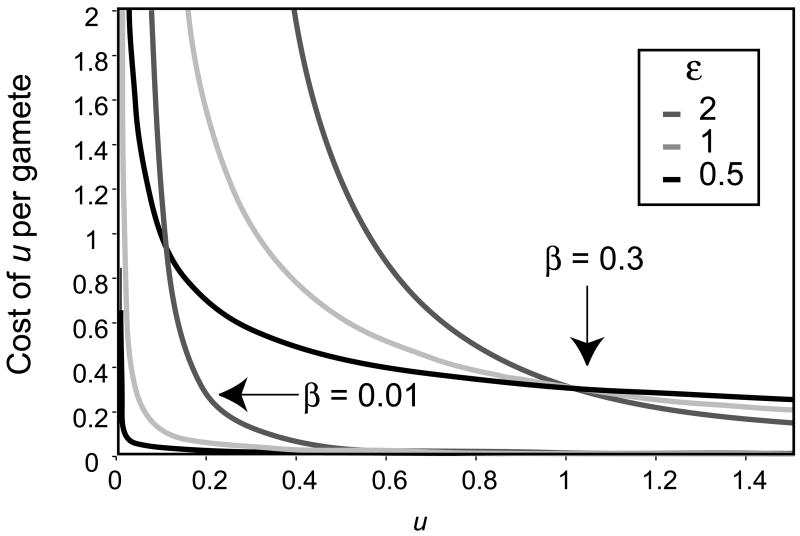

I assume a tradeoff between gamete number and the cost of maintaining a given mutation rate per gamete such that the energetic cost of each gamete increases monotonically and becomes prohibitively expensive as the genome wide deleterious mutation rate approaches zero (Sniegowski et al. 2000). This tradeoff is described with two parameters. Specifically, I assume that the cost per gamete of a certain mutation rate (Cu), in arbitrary energetic units, is given by:

| (1) |

where u is the genome wide rate of deleterious mutation per haploid gamete (Fig. 2). As u approaches zero, the cost of maintaining that mutation rate approaches infinity. The two parameters, ε and β, describe the shape of this curve and are allowed to range between 0 and infinity. The cost of maintaining a given mutation rate will be termed “mutation rate cost”.

Figure 2.

The cost of maintaining a given mutation rate, as given by Cuf = β/uε, for different values of β and ε.

Under this tradeoff, there are two fitness consequences of a given mutation rate - the number of fertilized zygotes produced and the number of deleterious mutations associated with that particular mutation rate. Under sperm competition, sperm are in excess so I assume that all eggs are fertilized. Thus, the number of zygotes produced by a given female is equal to the number of gametes produced. The number of eggs, Gf, is given by the function:

| (2) |

where E is the total amount of energy that can be allocated to gamete production (equal between males and females) and I and Cuf are equal to the amount of energy expended on each gamete in the form of energetic investment and mutation rate cost, respectively. To determine the evolutionary stable strategy, one must consider the evolution of a trait in the context of a population of individuals that assume an alternate strategy. For females, this will be noted as the ‘population female’ strategy and for males this will be noted as the ‘population male’ strategy. Thus, the number of gametes produced by the population female is designated Gpf.

To consider the number of successful zygotes produced by a focal male, one must consider the total number of matings, the total number of gametes allocated per mating and the success these gametes have in fertilizing eggs against a background of sperm competition. To do so, I assume a 1:1 sex ratio and set the number of gametes that a male allocates to one of N lifetime matings (N is the total number of lifetime matings per individual and is the same between males and females when the sex ratio is 1:1) equal to the energetic resources available per mating, in this case (E/N), divided by the cost of each gamete. Here, I set the energetic cost of a male gamete, excluding the mutation rate cost, equal to 1. Thus, the number of sperm allocated by males to a single mating is given by:

| (3) |

Similar to the population female, I assume that the population male produces Gpm gametes. In this framework, E is expressed in units equal to the cost of a single sperm excluding mutation rate costs, I is equal to the ratio of female to male gamete costs excluding mutation rate costs (commonly known as the anisogamy ratio), and the parameter β, within the mutation cost function, acts as a scaling factor that determines the fraction of energy spent on gamete production dedicated to maintaining a particular mutation rate.

Given the number of sperm allocated to a single mating by the focal male, I determine the lifetime quantity of female eggs that are secured under sperm competition. Over the lifetime of a male, I have designated the total number of matings equal to N, and assumed this is fixed. Therefore, that a male expends E/N amount of energy per mating on gametes assumes that males allocate gametes equally between matings. This simplification is violated in cases where males adjust ejaculate size among females, such as has been observed in a variety of species (Engqvist 2007; Linley and Hinds 1975; Pizzari et al. 2003; Svard and Wiklund 1986). I also designate z, the total number of competing ejaculates per mating. The parameter z functions as the index of sperm competition - large values of z indicate that the sperm of a focal male must compete against sperm from a large number of males. If females are considered the choosy sex, the value z will depend in part on the advantage to females of multiple mating. These advantages are not well understood, so I also consider z fixed – by doing so, z has no variance. Thus, the fraction of the total number of gametes that a female allocates per competing sperm pool will be equal to z/N if females evenly allocate gametes among these pools. For example, if a female mates four times in her lifetime (N = 4) and mating occurs in bouts in which the ejaculates from two males compete each time (z = 2), then the female will be participating in two mating bouts and allocates half of her gametes to each mating bout (z/N = 1/2).

If the total number of competing ejaculates equals z, then the number of ejaculates competing with the focal male equals z − 1. In this model, I assume perfect sperm mixing such that the proportion of eggs fertilized by the focal male is equal to the fraction of sperm provided by that male out of the total number of sperm available to the female. Thus, for a given mating, the proportion of eggs secured by a male is equal to: Gm/[(z−1) Gpm + Gm] where Gm is equal to the number of sperm allocated by the focal male and Gpm is the number of sperm allocated by competing population males. Under these assumptions, the total number of female eggs fertilized by the focal male equals the product of 1) the lifetime number of matings (N), 2) the fraction of eggs allocated to each competing pool (z/N), 3) the total number of eggs produced by females (Gpf) and 4) the fraction of eggs secured per mating (Gm/[(z−1) Gpm + Gm]) Thus, male lifetime number of eggs fertilized:

| (4) |

Note that when z = 1, which occurs under complete monogamy, the sperm competition term disappears and equation 4 reduces to Gm(successful) = Gpf. Thus, under a model of sperm competition, z must be greater than one. Non-integer values of z would apply to cases in which females do not mate with males simultaneously and a portion of the ejaculate from a previous male is depleted prior to mating with the focal male. Therefore, while I assume that z has no variance in the population, z is continuous and functions as the index of sperm competition. Also note that when all males in the population have the same reproductive strategy (i.e, the focal and population males produce the same number of gametes and Gpm = Gm.), equation 4 also reduces to Gm(successful) = Gpf.

To determine the component of male and female fitness that is a function of the deleterious mutations associated with a given mutation rate, I resort to the framework developed by Kondrashov (Kondrashov 1995a; Kondrashov 1995b). Selection on the mutation rate depends on the degree to which mutation rate modifiers are associated with their consequences - a strong mutator allele is kept at low frequency in the population through it’s linkage to the deleterious mutations that it is responsible for (in this framework, only deleterious mutations are considered). To determine the relative fitness of a modifier of the mutation rate, Kondrashov considered the case in which the number of mutations per genome within the population prior to selection is sufficiently large as to be approximated by a Gaussian distribution. In this case, for a given modifier genotype and a given mode of selection against deleterious mutations (e.g. exponential), an equilibrium distribution with a defined mean and variance for the number of mutations per genome can be defined. Each modifier genotype yields a unique distribution for the number of deleterious mutations per genome and selection against a given modifier can be determined based on this distribution. I assume U indicates the precise number of new mutations that occur each generation (designated “shift mode”) rather than the mean of a Poisson distribution. I consider here the diploid case in which the life cycle is characterized by selection, followed by mutation, followed by reproduction (meiosis followed by syngamy, see Kondrashov 1995a for details). Finally, I allow male and female mutation rates to evolve independently of one another. Thus, U is the mutation rate per diploid genome and is the sum of the male (um) and female (uf) mutation rates per haploid gamete. Equation 29 of Kondrashov (1995b) gives the relative fitness of a genotype modifying the mutation rate to the value Ui within a population of mutation rate Up,

| (5) |

where α = δ2/(2−ρ). The parameter δ, equal to the standardized selection differential (the difference in the mean number of mutations per genome before and after selection), and parameter ρ, equal to the ratio of variances in the number of mutations per genome before and after selection, determine the mode of selection. In this case, I limit the model to soft exponential selection with no epistasis. Thus, fitness of an individual is determined only relative to the rest of the population and fitness is given by e−sX where s is the selection coefficient for deleterious mutations and X is the number of mutations per genome. In this case, δ is equal to -s and ρ is equal to one (Charlesworth 1990; Kondrashov 1995a; Shnol and Kondrashov 1993). Since I consider the evolution of male and female mutation rates separately, the relative fitness of a modifier of the mutation rate in one sex is evaluated in conjunction with the population mutation rate in the opposite sex. Specifically, where the population diploid genome wide mutation rate, Up, is given by the sum of the population male and female haploid mutation rate (upm + upf), the diploid genome wide mutation rate for an individual male or female modifier, Ui, is given by (um + upf) and (upm + uf), respectively. Thus, substituting these values into equation (5), the relative fitness of a female (wgen.female) or male (wgen.male) with a defined mutation rate is given, respectively, by:

| (6) |

| (7) |

Total female and male fitness is given by the product of the relative fitness attributed to mutation and relative fitness attributed to fecundity, specifically, wgen.female Gf and wgen.male Gm(successful), respectively.

Now, following the framework provided by Kondrashov, consider the female and male fitness functions in terms of uf, um, upf and upm: (wgen.female Gf)(uf, upf, upm) and (wgen.male Gm(successful))(um, upf, upm). To find the optimal female and male mutation rates, I define the functions f(uf, upf, upm) and m(um, upf, upm) as equal to the derivatives of the female and male fitness functions with respect to the mutation rate of the focal individual and set the derivatives equal to zero:

| (8) |

| (9) |

Since the ESS solution for optimal mutation rate is the value taken by both the focal individual and population, we can find the ESS female and male mutation rates by solving the system of equations under the following conditions

| (10) |

| (11) |

After simplification, and assuming z is greater than one, for optimal female fitness I have the polynomial:

| (12) |

and for optimal male fitness, the polynomial:

| (13) |

General solutions to this system of equations for uf and um cannot be expressed as elementary functions since both are polynomials of order (1+ε) and ε is allowed to range between 0 and infinity. However, several features can be seen from closer inspection. Equations 12 and 13 indicate that there is only one positive real solution for u to each equation. Additionally, by holding the last term in each of the polynomials fixed, one can discern how changes in the value of α, I and z influence the optimal male and female mutation rate. For both male and female mutation rates, increases in α lead to decreases in the optimal mutation rate. This is expected in part because α is positively correlated with the selection coefficient against new mutations. By increasing the value of I, the optimal female mutation rate decreases. This is reasonable - greater energetic investment in each female gamete leads to stronger selection to minimize the mutation rate as each gamete becomes more precious. As z approaches 1, the first and second terms of equation 9 approach infinity. In this case, the optimal male mutation rate approaches zero and a condition in which the optimal male mutation rate is always lower than the optimal female mutation rate is satisfied. On the other hand, as z becomes large, the first and second terms of equation 8 approach 1 and (α − ε), respectively. In this case, when I equals one (equal gamete investment between the sexes) by symmetry the optimal mutation rates become equal between sexes. However, when z is very large, and I is greater than one, the optimal female mutation rate decreases and a condition in which the optimal male mutation rate is always higher is approached. This leads to the conclusion that the degree to which sperm competition drives a higher male mutation rate depends on the cost ratio between male and female gametes – sperm competition becomes more likely to drive a male-biased mutation rate as the ratio of female to male gamete costs increases. Furthermore, this result is independent of the actual value taken by E.

To show the behavior of these optimal mutation rates, numerical analysis of this system of equations is employed. While it is likely that the cost of maintaining a given mutation rate is monotonically increasing as the mutation rate approaches zero (Sniegowski et al. 2000), the shape of this curve is not known. Thus, I first consider a wide range of parameter space that covers unrealistically low to unrealistically high mutation rates. From this, I then examine optimal male and female mutation rates as a function of z for a reasonable set of parameters.

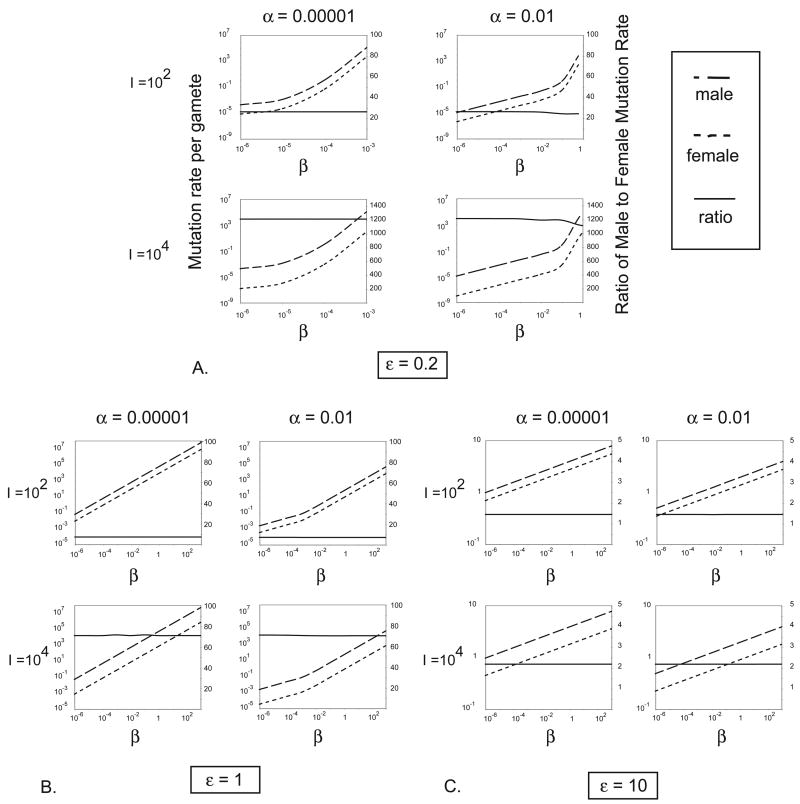

Figure 3 shows optimal male and female mutation rates, and their ratio, as a function of β for different values of ε when z = 2, I is either 102 or 104 and s is either 0.01 or 0.1. Mutation accumulation experiments typically suggest a value of s of about 0.1, though this is likely an overestimate since fitness assays in the lab are not sensitive to mutations of small effect (Garcia-Dorado et al. 2004). Several things are noted in Figure 3. First, even when parameters are allowed to vary widely, resulting in a range that covers even unrealistically high and low optimal mutation rates, the optimal male mutation rate is always higher than the optimal female mutation rate when z = 2. Secondly, increases in I substantially increase the ratio of male to female mutation rates through it’s effect on decreasing the female mutation rate. On the other hand, increases in α decrease both optimal male and female mutation rates to a similar degree and have little effect on the ratio. Finally, increases in the two parameters that define the mutation cost function, ε and β, have differing effects. As expected, since an increase in β leads to an increase in the cost to maintain a particular mutation rate, optimal mutation rates positively vary with β. β functions as a linear scaling factor for the cost of maintaining a given mutation rate in both sexes and influences optimal male and female mutation rates similarly. Thus, β has little effect on the ratio of optimal rates. On the other hand, small values of ε broaden the range over which optimal male and female mutation rates vary as a function of β. Larger values of ε decrease the ratio of male to female mutation rates. However, it is important to point out that as ε becomes very large when z= 2, the coefficients of the second term of equations (12) and (13) approach each other. By symmetry, as ε approaches infinity, the optimal male mutation rate will be larger than the optimal female mutation rate as long as I is greater than z/z−1.

Figure 3.

Numerically determined optimal male and female mutation rates, and their ratio, as a function of β when z = 2. The parts of the figure show the effects of varying ε and within each part I varies from top to bottom and α varies from left to right. The ratio is designated with the solid line and scale bars on the right.

Importantly, when ε is either 0.2 or 1, unrealistic mutation rates and ratios are observed. For example, when I = 104, which is more likely to be the case than I = 102, the male-mutation bias is at least more than 60, whereas the male mutation bias observed in nature is of the order or 2 to 10 ((Ellegren and Fridolfsson 1997; Ellegren and Fridolfsson 2003; Makova and Li 2002)). Thus, I next consider a set of parameter values that yield male and female mutation rates within a reasonable range of parameter space.

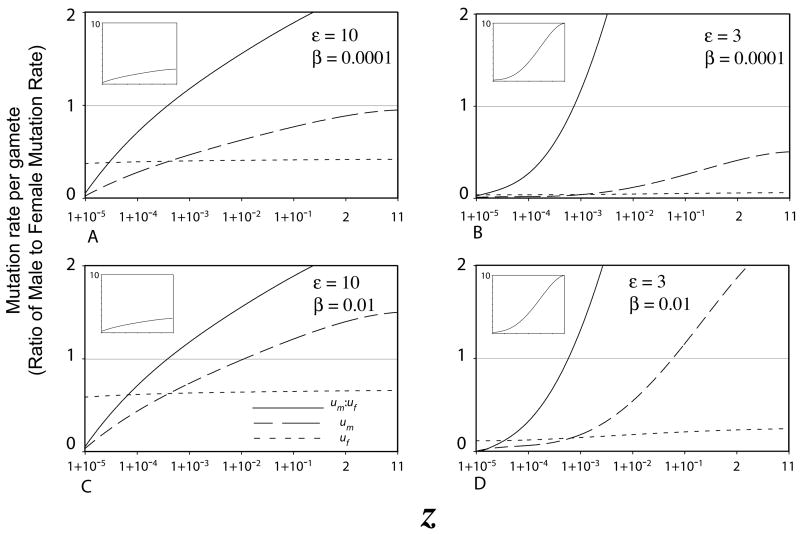

Figure 4 shows optimal male and female mutation rates, as well as the ratio, as a function of z, with parameters set to values that yield mutation rates over a reasonable range. Direct sequencing studies, which are likely to provide a much better estimate for U than mutation accumulation experiments, indicate U being 1.2 in Drosophila melanogaster (Haag-Liautard et al. 2007) and 0.96 (for coding sequences) in Caehnorhabditis elegans (Denver et al. 2004). In vertebrates, using an approach based on divergence in coding sequences (Keightley and Eyre-Walker 2000), the estimates ranged from 0.5 in mice and rats to 3.0 in humans and chimpanzees. Thus, for this exercise, we consider values of U in this range. In Figure 4, when z = 2, U ranges from 0.45 to 2.12.

Figure 4.

Numerically determined optimal male and female mutation rates, and their ratio, as a function of z, over a reasonable parameter range. Here, I set I = 10,000 and s = 0.05, with β and ε varying.. Since I assume no epistasis between deleterious mutations, ρ = 1 and thus α = 0.0025. Optimal mutation rates were calculated using the Gaussian approximation when Meq > 9. Where the Gaussian approximation couldn’t be used, optimal mutation rates were interpolated toward the values determined with the non-Gaussian approximation. Interpolated values are for z between 1+10−4 and 1+10−2 for B. and less than 1+10−4 for D.

Figure 3 indicates that values taken by the parameters β and s have little effect on the ratio of optimal mutaton rates. Nonetheless, since U is estimated to be in the range of 1, β ≥ 1 would indicate the condition that the cost of maintaining the given mutation rate would be near equal to all the other costs of a sperm, independent of the value taken by ε. Since this is unlikely, we consider the cases where β<1. Additionally, since mutation accumulation experiments that overestimate s suggest a value of around 0.1 (Garcia-Dorado et al. 2004), I consider the case of s = 0.05. Finally, when the optimal mutation rate (the sum of male and female mutation rates) is sufficiently low such that the assumption of a Gaussian distribution for the number of deleterious mutations per genome is violated, I resort to the approximation provided by Kondrashov (1995b) where relative fitness for a modifier of the mutation rate is equal to when the mean number of deleterious mutations is much less than 1.

Figure 4 indicates that only a very small amount of sperm competition is sufficient to drive the male mutation rate higher than the female mutation rate. In all parameter combinations, the male mutation rate is higher than the female mutation rate at values of z between 1+10−4 and 1+10−3. While higher values of β do lead to higher mutation rates, it has little effect on the ratio. On the other hand, larger values of ε result in lower ratios. And while this ratio increases as z increases, as z approaches 1 this ratio approaches zero. This is explained by the fact that under complete monogamy, male fertility is entirely determined by the number of eggs and males will maximize their fitness by producing just enough gametes, and no excess, to fertilize all the gametes of their mate. In this model, I assume that the anisogamy ratio is fixed above 1. Thus, since sperm are cheaper, under monogamy males are able to allocate the remainder of their energetic resources to lowering the male mutation rate. In this case, males will always have more energy to allocate to lowering the mutation rate because their gametes (by virtue of the fact they are male) are smaller. This is a result of fixing the anisogamy ratio above 1.

DISCUSSION

This analysis indicates that sperm competition, by forcing males to maintain the production of large numbers of sperm at the cost of a higher mutation rate, will drive a male-biased mutation rate over a very wide range of parameter space. However, I do not suggest that this is the only mechanism. As Parker (Parker 1982) indicated, an alternative explanation for small sperm with minimal resources may be that males must produce a large excess of sperm to meet the basic challenges of fertilization. If many sperm are destroyed before reaching the female gamete, selection may act to produce large numbers of sperm and this could also lead to a higher male mutation rate even under monogamy. Thus, these two forces, both sperm competition and selection to meet the challenge of fertilization, are expected to jointly favor a male-biased mutation rate if there is a tradeoff between the amount of sperm produced and a low mutation rate.

An important simplification of this model is that sperm competition is only a game of numbers and the number of sperm produced solely determines success in fertilization. In reality, a wide variety of competitive strategies have evolved aside from simply producing large numbers of sperm (Snook 2005). Furthermore, in Drosophila melanogaster and other insects the assumption of perfect sperm mixing does not apply. Rather, in D. melanogaster the second male to mate with a given female has greater success in fertilization than the first male (Harshman and Prout 1994; Lefevre and Jonsson 1962; Newport and Gromko 1984). Thus, male reproductive success in Drosophila is not solely a function of sperm number. In fact, D. melanogaster is a likely exception to the rule of a male-biased rate of nucleotide substitution and it is thought that the number of mitotic divisions are similar in the production of sperm and eggs (Bauer and Aquadro 1997). An advantage to competing by means other than solely producing large numbers of sperm is that natural selection, under these alternative strategies, may accommodate the production of fewer sperm with fewer mutations. If most mutations are deleterious and occur during cell division, there may be an advantage to shifting the game of competition outside of the domain of sperm number. If this were so, this may provide an explanation for the fact that female cryptic choice, rather than direct competition among males per se, may select for giant sperm at the cost of sperm numbers (Miller and Pitnick 2002). If females can shift the arena of sperm competition to a game of size, rather than a game of numbers, a female would potentially be able to select for a reduced male mutation rate by selecting for larger sperm that are fewer in number. Since selection on mutation rates is thought to be weak, further work needs to be done to determine if this secondary form of selection on the mutation rate would be a plausible explanation.

Another important point: the model presented here does not explicitly model a process of mutation during cell division. Rather, I simply assume there is a general tradeoff between the number of gametes and the mutation. This assumption is more relevant to mutations that may occur on a one-time basis per gamete, such as mutations that occur during meiosis. Mutations, such as those due to transposable elements (TEs), also may not correlate with the numbers of mitotic divisions in the germline if mobilization occurs at specific points in development. In D. melanogaster, a large number of spontaneous mutations with visible phenotypes are a result of TE insertions (Green 1988). In all known cases of TE induced hybrid dysgenesis in Drosophila, TEs become mobilized in the zygote when inherited paternally but not maternally (Bingham et al. 1982; Bucheton et al. 1984; Evgenev et al. 1997; Vieira et al. 1998; Yannopoulos et al. 1987). Therefore, the mobilization of transposable elements may represent a form of mutation, in addition to nucleotide substitutions, that natural selection tolerates differently in the two sexes. The cost born out by females may include such costs as the biased transmission of small interfering RNA that may be energetically costly but may be important in maintaining the repression of TEs through the generations (Blumenstiel and Hartl 2005). While D. melanogaster does not appear to be an example of a species in which the nucleotide substitution rate is higher in males, it may still represent an example of a species where, due to sperm competition, the interests in maintaining the preservation of genetic information differ between males and females.

Table 1.

Parameters Used.

| E | Energetic resources allocated to gamete production. Equal between males and females. |

| I | Energetic resources allocated to a single female egg, aside from resources allocated to maintaining a given mutation rate. Since the cost of a single sperm, aside from mutation rate costs, is defined as 1, I is the ratio of female to male gamete costs, aside from mutation rate costs. |

| z | Sperm competition index. The number of males whose ejaculates compete for a certain fraction of female eggs. |

| β | A linear scaling factor that determines the cost of maintaining a given mutation rate. |

| ε | An exponential scaling factor that determines the cost of maintaining a given mutation rate. |

| u(f,m.pf.pm) | Number of mutations per gamete for females, males, population females and population males. |

| Cu(f,m,pf,pm) | Cost of maintaining a given mutation rate for females, males, population females and population males. |

| G(f,m,pf,pm) | Number of gametes produced by females, males, population females and population males. |

| N | Number of total lifetime number of matings. |

| δ | The standardized selection differential for the mean number of mutations (Kondrasov, 1995a). |

| ρ | The ratio of variances in the number of mutations per genome before and after selection (Kondrasov, 1995a). |

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

LITERATURE CITED

- Bartosch-Harlid A, Berlin S, Smith NG, Moller AP, Ellegren H. Life history and the male mutation bias. Evolution Int J Org Evolution. 2003;57:2398–406. doi: 10.1554/03-036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauer VL, Aquadro CF. Rates of DNA sequence evolution are not sex-biased in Drosophila melanogaster and D. simulans. Mol Biol Evol. 1997;14:1252–7. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a025734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bingham PM, Kidwell MG, Rubin GM. The Molecular-Basis of P-M Hybrid Dysgenesis - the Role of the P-Element, a P-Strain-Specific Transposon Family. Cell. 1982;29:995–1004. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(82)90463-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blumenstiel JP, Hartl DL. Evidence for maternally transmitted small interfering RNA in the repression of transposition in Drosophila virilis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2005;102:15965–15970. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0508192102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bucheton A, Paro R, Sang HM, Pelisson A, Finnegan DJ. The Molecular-Basis of I-R Hybrid Dysgenesis in Drosophila-Melanogaster - Identification, Cloning, and Properties of the I-Factor. Cell. 1984;38:153–163. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(84)90536-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang BH, Shimmin LC, Shyue SK, Hewett-Emmett D, Li WH. Weak male-driven molecular evolution in rodents. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994;91:827–31. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.2.827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charlesworth B. Mutation-Selection Balance and the Evolutionary Advantage of Sex and Recombination. Genetical Research. 1990;55:199–221. doi: 10.1017/s0016672300025532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denver DR, Morris K, Lynch M, Thomas WK. High mutation rate and predominance of insertions in the Caenorhabditis elegans nuclear genome. Nature. 2004;430:679–682. doi: 10.1038/nature02697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellegren H, Fridolfsson AK. Male-driven evolution of DNA sequences in birds. Nat Genet. 1997;17:182–4. doi: 10.1038/ng1097-182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellegren H, Fridolfsson AK. Sex-specific mutation rates in salmonid fish. J Mol Evol. 2003;56:458–63. doi: 10.1007/s00239-002-2416-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engqvist L. Male scorpionflies assess the amount of rival sperm transferred by females’ previous mates. Evolution. 2007;61:1489–1494. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.2007.00107.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evgenev MB, Zelentsova H, Shostak N, Kozitsina M, Barskyi V, Lankenau DH, Corces VG. Penelope, a new family of transposable elements and its possible role in hybrid dysgenesis in Drosophila virilis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1997;94:196–201. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.1.196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Dorado A, Lopez-Fanjul C, Caballero A. Rates and effects of deleterious mutations and their evolutionary consequences. In: Moya A, Font E, editors. Evolution: From Molecules to Ecosystems. Oxford University Press; Oxford: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Green MM. Mobile DNA Elements and Spontaneous Gene Mutation. In: Lambert ME, McDonald JF, Weinstein IB, editors. Banbury Report. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; Cold Spring Harbor: 1988. pp. 41–50. [Google Scholar]

- Haag-Liautard C, Dorris M, Maside X, Macaskill S, Halligan DL, Charlesworth B, Keightley PD. Direct estimation of per nucleotide and genomic deleterious mutation rates in Drosophila. Nature. 2007;445:82–85. doi: 10.1038/nature05388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harshman LG, Prout T. Sperm Displacement without Sperm Transfer in Drosophila-Melanogaster. Evolution. 1994;48:758–766. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.1994.tb01359.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurst LD, Ellegren H. Sex biases in the mutation rate. Trends Genet. 1998;14:446–52. doi: 10.1016/s0168-9525(98)01577-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keightley PD, Eyre-Walker A. Deleterious mutations and the evolution of sex. Science. 2000;290:331–3. doi: 10.1126/science.290.5490.331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kondrashov AS. Dynamics of Unconditionally Deleterious Mutations - Gaussian Approximation and Soft Selection. Genetical Research. 1995a;65:113–121. doi: 10.1017/s0016672300033139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kondrashov AS. Modifiers of Mutation-Selection Balance - General-Approach and the Evolution of Mutation-Rates. Genetical Research. 1995b;66:53–69. [Google Scholar]

- Lefevre G, Jonsson UB. Sperm Transfer, Storage, Displacement, and Utilization in Drosophila Melanogaster. Genetics. 1962;42:1719. doi: 10.1093/genetics/47.12.1719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linley JR, Hinds MJ. Quantity of Male Ejaculate Influenced by Female Unreceptivity in Fly, Culicoides-Melleus. Journal of Insect Physiology. 1975;21:281–285. doi: 10.1016/0022-1910(75)90023-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makova KD, Li WH. Strong male-driven evolution of DNA sequences in humans and apes. Nature. 2002;416:624–6. doi: 10.1038/416624a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller GT, Pitnick S. Sperm-female coevolution in Drosophila. Science. 2002;298:1230–1233. doi: 10.1126/science.1076968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyata T, Hayashida H, Kuma K, Mitsuyasu K, Yasunaga T. Male-driven molecular evolution: a model and nucleotide sequence analysis. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol. 1987;52:863–7. doi: 10.1101/sqb.1987.052.01.094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newport MEA, Gromko MH. The Effect of Experimental-Design on Female Receptivity to Remating and Its Impact on Reproductive Success in Drosophila-Melanogaster. Evolution. 1984;38:1261–1272. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.1984.tb05648.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker GA. Why Are There So Many Tiny Sperm - Sperm Competition and the Maintenance of 2 Sexes. Journal of Theoretical Biology. 1982;96:281–294. doi: 10.1016/0022-5193(82)90225-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pecon Slattery J, O’Brien SJ. Patterns of Y and X chromosome DNA sequence divergence during the Felidae radiation. Genetics. 1998;148:1245–55. doi: 10.1093/genetics/148.3.1245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pizzari T, Cornwallis CK, Lovlie H, Jakobsson S, Birkhead TR. Sophisticated sperm allocation in male fowl. Nature. 2003;426:70–74. doi: 10.1038/nature02004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimmin LC, Chang BH, Li WH. Male-driven evolution of DNA sequences. Nature. 1993;362:745–7. doi: 10.1038/362745a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shnol EE, Kondrashov AS. The Effect of Selection on the Phenotypic Variance. Genetics. 1993;134:995–996. doi: 10.1093/genetics/134.3.995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sniegowski PD, Gerrish PJ, Johnson T, Shaver A. The evolution of mutation rates: separating causes from consequences. Bioessays. 2000;22:1057–66. doi: 10.1002/1521-1878(200012)22:12<1057::AID-BIES3>3.0.CO;2-W. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snook RR. Sperm in competition: not playing by the numbers. Trends in Ecology & Evolution. 2005;20:46–53. doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2004.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Svard L, Wiklund C. Different Ejaculate Delivery Strategies in 1st Versus Subsequent Matings in the Swallowtail Butterfly Papilio-Machaon L. Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology. 1986;18:325–330. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor F, Tyekucheva S, Zody M, Chiaromonte F, Makova KD. Strong and weak male mutation bias at different sites in the primate genomes: Insights from the human-chimpanzee comparison. Molecular Biology and Evolution. 2006;23:565–573. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msj060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vieira J, Vieira CP, Hartl DL, Lozovskaya ER. Factors contributing to the hybrid dysgenesis syndrome in Drosophila virilis. Genetical Research. 1998;71:109–117. doi: 10.1017/s001667239800322x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whittle CA, Johnston MO. Male-driven evolution of mitochondrial and chloroplastidial DNA sequences in plants. Mol Biol Evol. 2002;19:938–49. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a004151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whittle CA, Johnston MO. Male-biased transmission of deleterious mutations to the progeny in Arabidopsis thaliana. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:4055–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0730639100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yannopoulos G, Stamatis N, Monastirioti M, Hatzopoulos P, Louis C. Hobo Is Responsible for the Induction of Hybrid Dysgenesis by Strains of Drosophila-Melanogaster Bearing the Male Recombination Factor 23.5mrf. Cell. 1987;49:487–495. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(87)90451-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]