Abstract

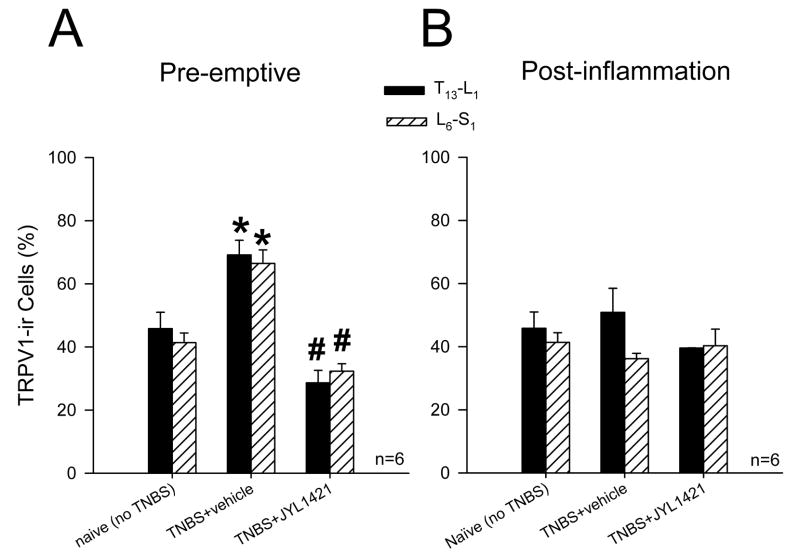

The transient receptor potential vanilloid 1 receptor (TRPV1) is an important nociceptor involved in neurogenic inflammation. We aimed to examine the role of TRPV1 in experimental colitis and in the development of visceral hypersensitivity to mechanical and chemical stimulation. Male Sprague-Dawley rats received a single dose of trinitrobenzenesulfonic acid (TNBS) in the distal colon. In the pre-emptive group, rats received the TRPV1 receptor antagonist JYL1421 (10μmol/kg, iv) or vehicle 15 minutes prior to TNBS followed by daily doses for 7days. In the post-inflammation group, rats received JYL1421 daily for 7 days starting on day 7 following TNBS. The visceromotor response (VMR) to colorectal distension (CRD), intraluminal capsaicin, capsaicin vehicle (pH6.7) or acidic saline (pH5.0) was assessed in all groups and compared to controls and naïve rats. Colon inflammation was evaluated with H&E staining and myeloperoxidase (MPO) activity. TRPV1 immunoreactivity was assessed in the thoraco-lumbar (TL) and lumbo-sacral (LS) DRGs neurons. In the pre-emptive vehicle group, TNBS resulted in a significant increase in the VMR to CRD, intraluminal capsaicin and acidic saline compared the JYL1421 treated group (p<0.05). Absence of microscopic colitis and significantly reduced MPO activity was also evident compared to vehicle treated rats (p<0.05). TRPV1 immunoreactivity in the TL (69.1± 4.6%) and LS (66.4± 4.2%) DRG in vehicle treated rats was increased following TNBS but significantly lower in the pre-emptive JYL treated group (28.6±3.9 and 32.3±2.3 respectively, p<0.05). JYL1421 in the post-inflammation group improved microscopic colitis and significantly decreased the VMR to CRD compared to vehicle (p<0.05, ≥30mmHg) but had no effect on the VMR to chemical stimulation. TRPV1 immunoreactivity in the TL and LS DRG was no different from vehicle or naïve controls. These results suggest an important role for TRPV1 channel in the development of inflammation and subsequent mechanical and chemical visceral hyperalgesia.

Keywords: TRPV1, TNBS, visceral hyperalgesia, colorectal distension, capsaicin

Introduction

Changes in visceral sensitivity through peripheral sensory pathways following inflammation play a critical role in the pathogenesis of chronic abdominal pain. Interestingly, patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) have a high prevalence of abdominal pain during periods of remission (Simren et al., 2002). Since patients with functional abdominal pain have been shown to have a decreased sensory threshold to colorectal balloon distension (Ritchie et al., 1972), it has been suggested that sensitization of peripheral sensory pathways contributes to the mechanical hypersensitivity (Lembo et al., 1994). Proposed mechanisms that could account for the sensitization of primary sensory afferents include increased expression of receptor molecules involved in nociceptive pathways or alteration of ionic channel properties (Kirkup et al., 2001). Recently, the TRPV1 receptor has received much attention as a putative mechanosensor involved in integrating painful stimuli and in the generation of neurogenic inflammation and hyperalgesia.

The TRPV1 receptor is a ligand-gated non-selective cation channel that is well recognized as a polymodal channel. TRPV1 receptors integrate a variety of pain stimuli such as capsaicin (the pungent ingredient in chilli peppers), endogenous inflammatory derivative (endovanilloids), heat and low pH(< 6.0) (Caterina et al., 1999; Caterina and Julius, 2001; Olah et al., 2001). TRPV1 expression has been reported in intrinsic and extrinsic neurons innervating the gastrointestinal tract as well as in many somatic nociceptive pathways (Anavi-Goffer et al., 2002; Patterson et al., 2003). Inflammation of the rat hind paw results in increased expression of TRPV1 receptors in the dorsal root ganglia with a corresponding decrease in hot plate latency (Luo et al., 2004). The responses of primary sensory afferent fibers as well as behavioral sensitivity to mechanical distension of the colon are significantly reduced in TRPV1 knock out mice which suggests an important role for the TRPV1 channel in colonic, mechanical sensitivity (Jones et al., 2005). In regards to intestinal inflammation, it has been shown that pre-emptive treatment with capsazepine (TRPV1 antagonist) inhibits Clostridium difficile toxin A-induced substance P (SP) release and subsequent intestinal inflammation in rats (McVey and Vigna, 2001). This suggests that TRPV1 channel activation leads to the release of SP with subsequent plasma extravasation and tissue inflammation.

Intraluminal administration of trinitrobenzene sulfonic acid (TNBS) results in ulcerative damage and transmural inflammation and has been widely used to investigate the pathogenesis of bowel inflammation and to explore potential treatments (Wallace, 1988; Vilaseca et al., 1990; Wallace et al., 1992; Hoshino et al., 1992; McCafferty et al., 1994). Similar to post-infectious IBS, colonic inflammation in experimental animal models has been shown to result in visceral hyperalgesia that persists for up to 6 weeks in spite of resolved inflammation (Adam et al., 2006). The exact pathways leading to inflammation and persistent visceral hypersensitivity are not clearly understood.

We hypothesized that experimental colitis is mediated by TRPV1 receptors in primary sensory neurons innervating the colon, resulting in visceral hyperalgesia to colorectal distension and that this process can be prevented by pre-emptive administration of the selective TRPV1 receptor antagonist JYL1421. The present study was designed to investigate the role of the TRPV1 receptor in experimental colitis and in the development of visceral hyperalgesia. Assessment of visceral sensitivity to intraluminal chemicals known to activate the TRPV1 channel was also performed to further specify the role of TRPV1 in visceral hyperalgesia.

Methods

The study was carried out on adult male Sprague-Dawley rats (Harlan, Indianapolis, IN) with an average weight of 300–400g. Rats were kept under controlled conditions with a cycling 12-hour light/dark schedule and housed individually in plastic cages containing wood chip bedding. Prior to surgery, food but not water was suspended for 12 hours. During experiments, all rats were awake and un-anaesthetized. The Animal Care and Use Committee at the Medical College of Wisconsin with agreement of the International Association of Pain policies on use of laboratory animals approved all experimental protocols.

Surgical Preparation

All surgical procedures were performed after deep anesthesia with sodium pentobarbital (50 mg·kg−1 i.p.). Penicillin G (30,000 U, i.m.) was given preoperatively in all animals to prevent infection. Teflon coated electrodes (Cooner wire, Part#: A5631) were implanted in the external oblique muscle for EMG recordings. The pair of electrodes was externalized subcutaneously and protected using a silastic tube sutured to the dorsal aspect of the neck. Postoperatively, animals were given subcutaneous buprenorphine hydrochloride (0.1mg/kg) to relieve pain. Rats exhibiting motor deficits after surgery were euthanized and excluded from experimental procedures. Rats were housed separately following surgery and allowed to recuperate for at least 5 days prior to further interventions.

Experimental Colitis

Colonic inflammation was achieved by instilling TNBS (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) into the colon. Prior to administration of TNBS, rats were fasted for 24hours. Rats were deeply anesthetized with an i.p. injection of pentobarbital (50mg/kg) and TNBS (0.6ml of 30mg/ml TNBS in 50% ethanol) was instilled into the colon using a 7cm long oral gavage needle that was inserted into the descending colon. Rats were placed in the supine position with the lower portion of the body elevated in order to prevent leakage of TNBS from the colon. Following this procedure, the rats were individually housed.

Visceromotor Response to Colonic Distension

The visceromotor response (VMR) to colorectal distension (CRD) was used as an objective measure of visceral sensation in all groups given its reliability and reproducibility (20,21). EMG recordings from the external oblique muscles quantified contraction of the abdominal wall musculature in response to graded CRD. The individual rats were kept in a Bollman cage while a distensible latex balloon (5 cm in length) was inserted into the descending colon and rectum. The balloon was attached to a distension device by polyethylene tubing and was kept in place by taping the catheter to the tail. The balloon was connected to an isobaric distension system activated by the Spike 3 software (CED, Cambridge England). A pressure transducer monitored the intraluminal pressure during the stimulus response function (SRF). Distention pressures (5, 10, 20, 30, 40, 50 60, and 80 mmHg) were held constant during the 30second stimulus with a 180 sec, inter-stimulus interval. The EMG signal from the external oblique muscle was amplified through a low noise AC differential amplifier (model-3000: A-M Systems, Inc.) and recorded on-line using the Spike 3/CED 1401 data acquisition program. (CED 1401; Cambridge Electronic Design, Cambridge, England).

Visceromotor Response to Intraluminal Capsaicin

The VMR using EMG from the external oblique muscle was used to evaluate the sensitivity to intraluminal chemicals following TNBS. EMG recordings from the external oblique muscles quantified contraction of the abdominal wall musculature in response to intracolonic administration of capsaicin, capsaicin vehicle (ethanol and Tween 80, pH 6.7), or acidic saline (pH 5.0). The rats were kept in a Bollman cage with polyethylene tubing (PE-10) inserted into the distal colon and rectum. The tube was kept in place by taping the catheter to the tail with the opposite end attached to a 1.0ml syringe. The tip of the catheter was positioned approximately 3 cm from the anal verge. The EMG signal from the external oblique muscle was recorded as described in the previous section. Capsaicin, vehicle or acidic saline was injected into the descending colon via PE-10 catheters. The volume of injection was restricted to 100μl and injected over a 10 second period to avoid mechanical stimulation. A baseline EMG was recorded over 45 seconds prior to intraluminal injections followed by another 45 second recording after administration of intraluminal chemicals. In all cases, acidic saline trials preceded capsaicin.

Drugs

Solutions were made fresh before all experiments. A working solution (1mg/ml) of capsaicin (Tocris, Inc.) was made by dissolving 5 mg of the drug in 100μl of ethanol, 100μl of Tween 80 and 4.8μl of saline. JYL1421 (10mg/ml) was prepared in a similar fashion by dissolving 10 mg in 100μl of ethanol and 100μl of Tween 80 and 0.8ml of saline.

Histology

Rats were euthanized at 7 days and 14 days after induction of colitis in the pre-emptive and post-inflammation groups respectively. The distal colon was removed and cleaned in saline. The tissues were fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin and then embedded in paraffin. Sections were made every 5 micrometers, stained with haematoxylin-eosin and examined under light microscopy. Tissue inflammation was assessed in all samples in a blinded fashion. Tissue was evaluated for necrosis, neutrophilic infiltrates in the lamina propria and the degree of mucosal and submucosal edema.

Myeloperoxidase Detection in Colonic Tissue

Myeloperoxidase (MPO) was used as a surrogate marker for neutrophilic infiltration in the colonic tissue. Tissues from rats in the pre-emptive and post-inflammation groups (n=5 in each group) were assayed for MPO contents and compared with their respective vehicle controls (n=5 in each group). Tissue samples were homogenized in HTAB (0.5% in distilled water) and the homogenates were centrifuged at 10,000g for 20 minutes at 4°C and the clear supernatant was used for the assay. The substrate O-dianisidine (16.7 mg) was dissolved in 90 ml of distilled water followed by 10 ml of potassium phosphate buffer (pH 6.0) and 50 μl of freshly prepared H2O2 (1%). An aliquot of 14 μl of each sample was used for the micro-titer plate assay and 200 μl of O-dianisidine solution was added to each well immediately prior to reading the plate. The resultant oxygen radical (O−) from the interaction of myeloperoxidase in the sample with hydrogen peroxide, combined with O-dianisidine dihydrochloride, the hydrogen donor (AH2), converted it into a colored compound. The color development was measured as an absorbance at 460 nm over a period of five minutes. MPO activity of the tissue samples were calculated based on the change in absorbance/minute. The change in absorbance for 1 μmole H2O2 split was 1.13×10−2 and the MPO content of the samples were calculated based on the formula; 1 Unit of MPO=1μmole H2O2 split.

Immunohistochemistry

Rats were deeply anesthetized with sodium pentobarbital (50 mg/Kg, i.p.) and the chest was opened by mid-sternal incision. Animals were perfused transcardially with ice cold phosphate buffer solution followed by 4% paraformaldehyde in 0.1 M PBS, pH 7.4. Bilateral thoracic T13-L1 and L6-S1 DRG were collected and incubated in 4% paraformaldehyde overnight at 4°C. Tissue samples were cleaned of connective tissues and cryoprotected in 20% sucrose in 0.1 M PBS for 24 hrs. For immunostaining, sections (15 μm) were rehydrated in PBS and non-specific sites were blocked by incubating the sections in PBS containing 10% normal goat serum (NGS), 0.5% Triton X–100 and 0.1% sodium azide for 60 min at room temperature. For TRPV1 staining, sections were incubated with guinea pig anti-VR1 antibody (1:500; AB5566; Chemicon International Inc. Temecula, CA) overnight at 4°C. The antibody dilution was carried out in PBS containing 3% NGS, 0.3% Triton X-100 and 0.1% azide (antibody diluent). After four washes with antibody diluent, sections were incubated at room temperature for 2 hours with fluorescence-labeled secondary antibodies. Secondary antibody used was Alexa 488-conjugated goat anti-guinea pig antibody (1:500, Jackson Immunoresearch, West Grove, PA). Specificity of the primary antibodies was assessed by pre-incubating overnight at 4°C with the immunizing peptides (50 μM) prior to the application to the sections.

Image analysis

Slides were examined under a fluorescence microscope (Nikon Eclipse 50i) using narrow band cubes for Alexa 488: (DM505, excitation filter 470–490, barrier filter 515–550 nm). Images were captured with a Spot II high resolution digital camera (Diagnostic Instruments Inc., USA) and processed with Adobe Photoshop program. The background was adjusted high enough to allow identification of unlabeled profiles. A total of 4 sections were randomly selected from each DRG in the T13-L1 and the L6-S1 segment from three rats in each group (pre-emptive JYL1421. pre-emptive vehicle, post-inflammation JYL1421 and post-inflammation vehicle). Four sections from each segment of three naïve rats were also used for comparison. The ratio of TRPV1-positive cells in the total profile was calculated in both the pre-emptive and post-inflammation groups 7 days and 14 days, respectively. Only cells containing a darker nucleus were selected for count. Quantitative estimation of positively stained neurons was carried out using ImageJ program (NIH, MD) and all cell profiles in an image (100–200) were counted. To avoid counting the same profile twice, profiles were marked with a color-coded number using the plugins cell counter in ImageJ. Experimenters were blinded to all experimental protocols.

Experimental Protocol

In the first set of experiments, the pre-emptive effects of JYL1421 (prior to TNBS) on visceral sensitivity and inflammation were examined. All animals underwent surgery for implantation of electrodes and femoral vein catheters followed by a baseline VMR to CRD 5–7 days later. Rats receive either JYL1421 (10μmol/kg, iv) or vehicle (0.6 ml, i.v.). The drug or vehicle was given 15 minutes prior to instillation of TNBS and then daily for a total of seven days. A repeat VMR was performed at the end of the treatment period and compared to baseline responses. In another group with the same protocol but without CRD, the distal colon was removed for histological evaluation and MPO measurements. A different group of rats that receive either pre-emptive JYL1421 or vehicle prior to TNBS, was used for assessment of sensitivity to intracolonic capsaicin (0.015mg), capsaicin vehicle (pH6.7) or acidic saline (pH 5.0) (n=6 in each group). Similar trials were performed in naïve, (non-TNBS, non-JYL1421) treated rats (n=6). In order to evaluate the acute effects of the TRPV1 receptor antagonist on mechanical and chemical stimulation, JYL1421 (10μmol/kg, i.v.) was given 15 minutes prior to CRD (n=9) or intraluminal capsaicin (0.03mg) (n= 5) in a group of pre-emptive vehicle treated rats 7 days following TNBS.

The second set of experiments examined the effects of JYL1421 on visceral sensitivity and colitis post-inflammation with TNBS. Following baseline VMR to CRD recordings, rats received TNBS and were allowed to recover for seven days. The rats then received daily dosing with either JYL1421 (10μmol/kg, i.v.) or vehicle (1ml, i.v.) for seven days. At the end of the dosing schedule (total 14 days following TNBS) both groups underwent VMR to CRD testing and histological evaluation of the distal colon. A different group of rats that received JYL1421 or vehicle post-inflammation on the same schedule as above underwent assessment of the VMR to intracolonic capsaicin (0.015mg), capsaicin vehicle or acidic saline (pH5.0) at the end of treatment period (n=6 in each group).

The third set of experiments involved immunohistochemical staining for TRPV1 in the dorsal root ganglia (DRG) to precisely determine the involvement of peripheral TRPV1 receptors in the altered visceral sensitivity and inflammation. As in the previous protocol, rats received either JYL-1421 or vehicle pre-emptively or post-inflammation. Following the treatment period, the thoracolumbar (T13-L1) and lumbosacral (L6-S1) DRGs were removed bilaterally and TRPV1 expression was assessed in all groups. Similar studies were performed in naïve rats. None of the rats in the immunohistochemical studies received intraluminal chemicals or CRD.

Data Analysis

For colonic distension, the area under the curve was measured for the EMG recordings and taken as a percent of the maximum response to 80mmHg of CRD for each individual rat at baseline prior to TNBS. Therefore, each rat served as its own control. The average for each distension pressure response was calculated and plotted. A comparison was made between the groups before and at different time intervals after TNBS in the pre-emptive and post-inflammation groups. Because no baseline data existed for the intraluminal capsaicin or acidic saline, the raw EMG data measured was recorded during a 45 sec period following the stimulus and the area under the curve was calculated. Data were analyzed with two way repeated measures (ANOVA) and by Student-Newman-Keuls for multiple comparisons. One-Way ANOVA was used to calculate the significance of the differences in myeloperoxidase activity and immunoreactivity binding among the groups with Tukey post-hoc tests for multiple comparisons. Results are expressed as mean ± SEM. Values with p<0.05 were considered to be significant.

Results

Pre-emptive JYL1421 Treatment

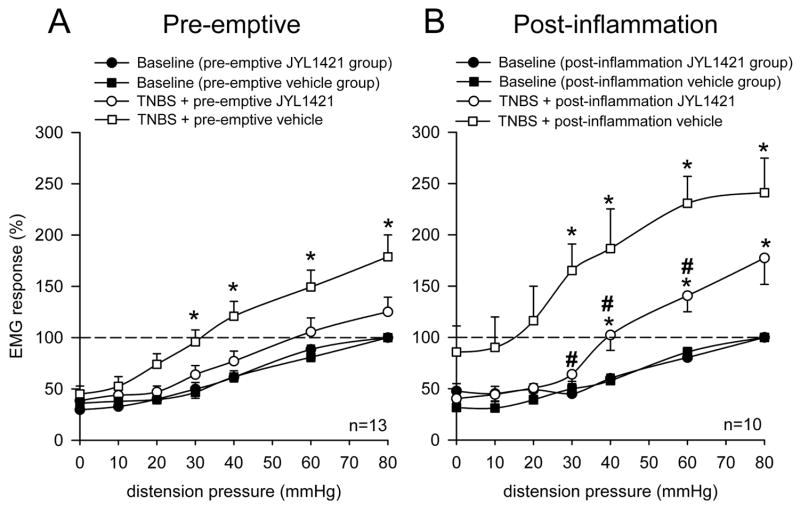

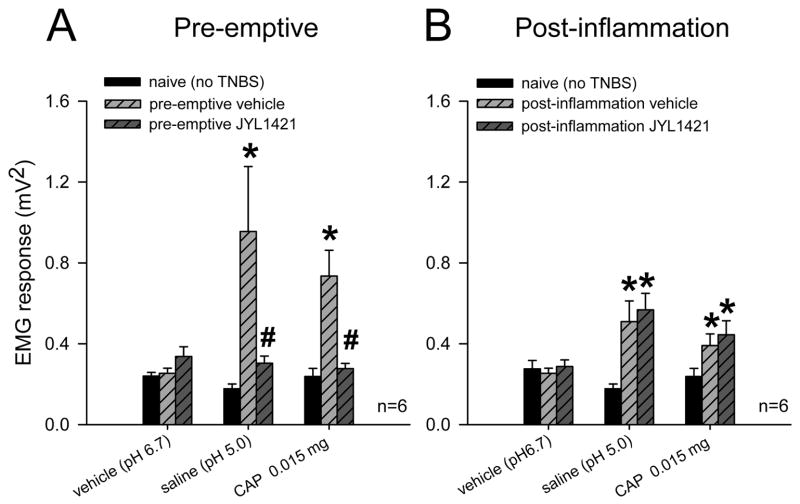

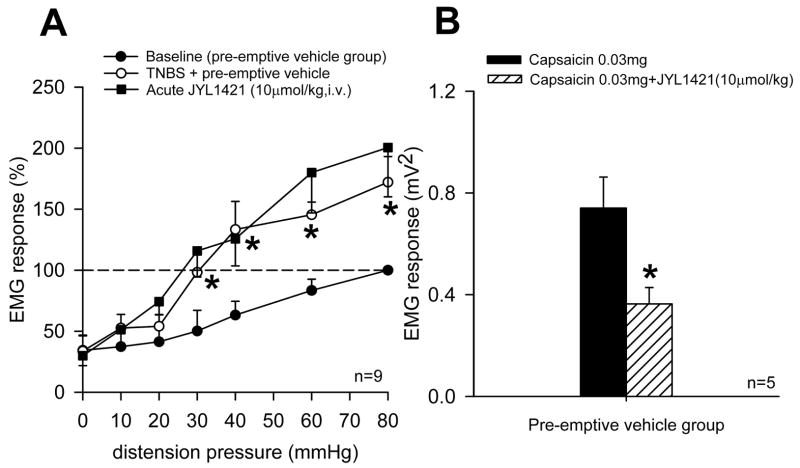

Seven days following TNBS, control rats that received daily intravenous vehicle developed a significant increase in the VMR to CRD at distensions pressure ≥ 30mmHg compared to baseline responses (n=13, p<0.05). However, animals in the pre-emptive JYL1421 failed to develop any alteration in the VMR when compared to its baseline (pre-TNBS) response throughout all distension pressures (Fig. 1A). TNBS-treated vehicle control rats also demonstrated a significant increase in VMR to intraluminal pH 5.0 saline (0.9554±0.32 mV2) compared to naïve (non-TNBS) rats (0.17±0.02) (p<0.05). However, rats that received pre-emptive JYL1421 did not develop any alteration in the VMR to intraluminal acidic saline (0.30±0.03) when compared to naïve rats (Fig. 2A). Similar results were obtained with intraluminal capsaicin. The VMR of the pre-emptive vehicle rats to capsaicin was significantly enhanced (0.73±0.12) compared to naïve rats (0.23±0.04, p<0.05) (Fig 2A). The increase in the VMR following TNBS was not evident in rats pre-emptively treated with JYL1421 since the response was no different from naïve rats (Fig 2A). There was no difference in the response to intraluminal capsaicin vehicle when compared within groups (p>0.05, Fig 2A). This result suggests that preemptive treatment with the TRPV1 receptor antagonist prevented the development of visceral hyperalgesia to intraluminal acidic saline and capsaicin as well as to mechanical distension. In the pre-emptive vehicle treated rats that developed hyperalgesia to mechanical distension, JYL1421 had no effect on the VMR when given acutely (15 minutes prior to the VMR) (Fig 3A). Conversely, the increased response to intraluminal capsaicin was significantly attenuated by acute, intravenous administration JYL1421 (Fig 3B).

Figure 1.

Summary data of the mean VMR to CRD following TNBS in rats treated with pre-emptive vehicle or JYL1421 and post-inflammation vehicle or JYL1421. A. The VMR significantly increased at distension pressures ≥ 30mmHg one week following intracolonic TNBS in the vehicle treated group (*p<0.05 vs. baseline) indicating the development of visceral hyperalgesia. There was no difference in the VMR in the rats that received pre-emptive JYL1421 (10μmol/kg, i.v.) when compared to baseline. B. The VMR significantly increased at distension pressures ≥ 30mmHg two week following TNBS in the vehicle control group (*p<0.05 vs. baseline). The VMR in the post-inflammation JYL1421 group remained significantly higher than baseline at CRD pressures > 30mmHg (*p<0.05 vs baseline VMR), but the response was significantly less than the vehicle treated group at CRD pressures of 30, 40 and 60mmHg (#p<0.05 vs post-inflammation vehicle).

Figure 2.

Summary data of mean VMR to acute intraluminal capsaicin vehicle (pH 6.7), acidic saline (pH 5.0) or capsaicin following TNBS in rats treated with pre-emptive vehicle or JYL1421 and post-inflammation vehicle or JYL1421. A. There was no difference in the response to intraluminal capsaicin vehicle in rats in the pre-emptive groups when compared to naïve rats. Rats that received intracolonic TNBS with preemptive vehicle (i.v.) exhibited a significantly greater response to intraluminal acidic saline and capsaicin (0.015mg) compared to naïve rats and pH 6.7 vehicle. However, animals treated with pre-emptive JYL1421 did not exhibit any significant increase in VMR to intraluminal acidic saline or capsaicin compared to naïve and were significantly lower than JYL1421 vehicle treated (* p<0.05 vs naïve and pH 6.7 vehicle, # p<0.05 vs JYL1421 vehicle). B. There was no difference in the response to intraluminal capsaicin vehicle in rats in the post-inflammation groups when compared to naïve rats. (p>0.05). Rats that received JYL1421 vehicle post-inflammation exhibited a significantly greater response to intraluminal acidic saline and capsaicin (0.015mg) compared to naïve rats. Similarly, animals treated with JYL1421 post-inflammation continued to exhibited a significantly higher response to intraluminal acidic saline and capsaicin compared to naïve (*p<0.05).

Figure 3.

Acute effects of JYL1421 on mechanical distension and intraluminal capsaicin in pre-emptive vehicle rats. A. The VMR significantly increased at distension pressures ≥ 30mmHg one week following TNBS in the pre-emptive vehicle group (*p<0.05 vs. baseline). There was no difference in the VMR in the rats that received JYL-1421 (10μmol/kg, iv) 15 minutes prior the second VMR. B. The increased response to intraluminal capsaicin (0.03mg) in rats that received TNBS with pre-emptive vehicle was significantly attenuated by acute dosing of JYL1421 (10μmol/kg, iv) given 15 minutes prior to intraluminal capsaicin (* p<0.05).

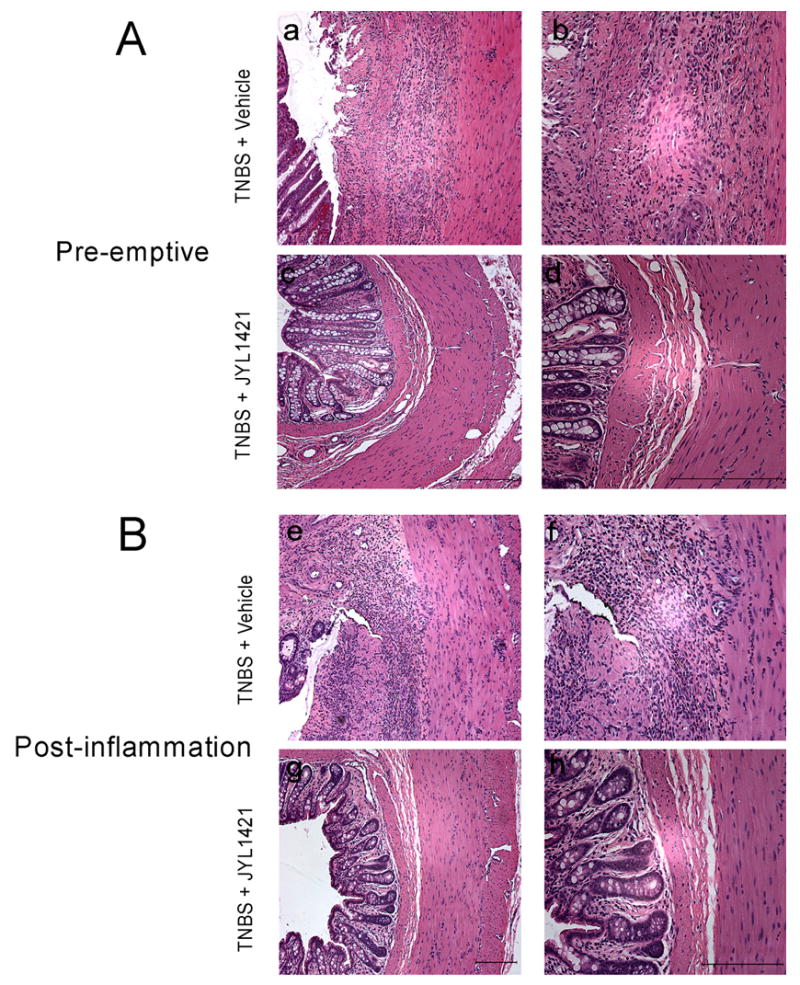

Histology of Pre-emptive JYL1421 Treated Rats

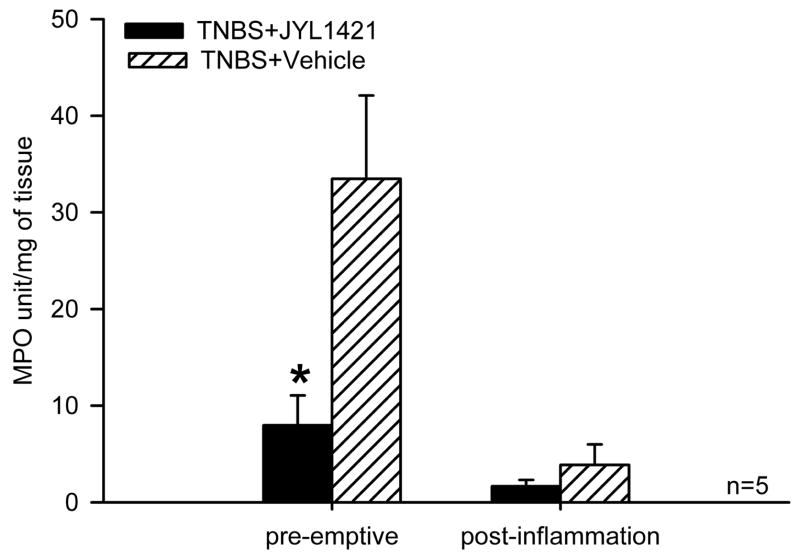

Seven days following intracolonic TNBS, segments from the distal colon of pre-emptive vehicle treated animals demonstrated multifocal areas of necrosis, diffuse inflammatory infiltrates and loss of epithelium (Fig 4A and 4B). Rats in the pre-emptive JYL1421 group appeared to have minimal inflammatory infiltrates and preserved epithelium 7 days following TNBS administration (n=5) (Fig 4C and 4D). The degree of acute inflammation in both groups was assessed by measuring myeloperoxidase activity. In accordance with the microscopic findings, there was a significantly lower myeloperoxidase activity in rats pre-emptively treated with JYL1421 (7.9 ± 3.0 OD/gm) compared to vehicle treated (33.4±8.6 OD/gm wet wt, p<0.05) (Fig. 5).

Figure 4.

A. Hematoxylin and eosin staining of distal colon one week following TNBS administration. TNBS-treated rats demonstrated destruction of the epithelium with prominent neutrophilic infiltrates in the JYL1421 vehicle treated rats (a) 10X and (b) 20X. Pretreatment with JYL1421 prevented the epithelial damage in the distal colon and decreased the inflammatory infiltrates (c) 10X and (d) 20X. B. Staining of the distal colon in the post inflammation groups (two weeks following intracolonic TNBS). Rats continued to demonstrate destruction of the epithelium with prominent mixed inflammatory infiltrates in the JYL1421 vehicle treated rats (e) 10X and (f) 20X. Post-inflammation treatment with JYL1421 improved the epithelial damage in the distal colon and decreased the inflammatory infiltrates (g) 10X and (h) 20X. Scale bar, 100μm.

Figure 5.

Bar graph represents the MPO activity in the distal colon following intracolonic TNBS. The MPO activity was significantly lower in rats with pre-emptive administration of JYL1421 compared to vehicle controls (*p<0.05). There was no difference in the MPO activity in the post-inflammation JYL1421 group compared to vehicle control.

Post-inflammation JYL1421 Treatment

In the post-inflammation experiments, rats that received JYL1421 vehicle, demonstrated a persistent increase in the VMR to CRD compared to baseline at distension pressures ≥ 30mmHg (n=10, p<0.05). Rats that received JYL1421 also demonstrated an increase in the VMR above baseline that was significant at distension pressures 40mmHg (n=10, p<0.05). However, this response was significantly less compared to the vehicle treated animals at CRD pressures of 30, 40 and 60mmHg (p<0.05, Fig 1B). This suggests that JYL1421 attenuated the visceral hyperalgesia to mechanical distension following TNBS colitis. While there was no difference in the response to intraluminal capsaicin vehicle when compared between naïve, post-inflammation vehicle and post-inflammation JYL1421 (p>0.05), there was a significant increase in the VMR to intracolonic acidic saline (pH 5.0) and to capsaicin (0.015mg) in rats that received post-inflammation JYL1421 vehicle compared to naïve rats (p<0.05, Fig 2B). The VMR to intracolonic acidic saline and capsaicin in the post-inflammation JYL1421 treated group was also significantly higher than naïve rats (p<0.05, Fig. 2B).

Histology in Post-inflammation Treatments

The colonic tissue of post-inflammation JYL1421 vehicle treated rats (n=3) demonstrated persistent mixed inflammatory infiltrate in the lamina propria with intestinal edema (Fig 4E and 4F). In contrast, there was no evidence of inflammatory infiltrates, edema or necrosis in colonic sections of rats in the post-inflammation JYL1421 treated group (n=3, Fig 4G and 4H). The MPO activity was overall much lower when measured at two weeks following TNBS compared with the measurements at 1 week suggesting the resolution of acute inflammation with a progressive decrease in neutrophilic infiltration. Although there appeared to be no difference in the MPO activity between the vehicle and JYL1421 treated rats, the significant reduction in MPO activity in all animals after two weeks does not allow interpretable results as far as the effects of JYL141 treatment and overall inflammation in the chronic state (Fig. 5).

Immunohistochemistry

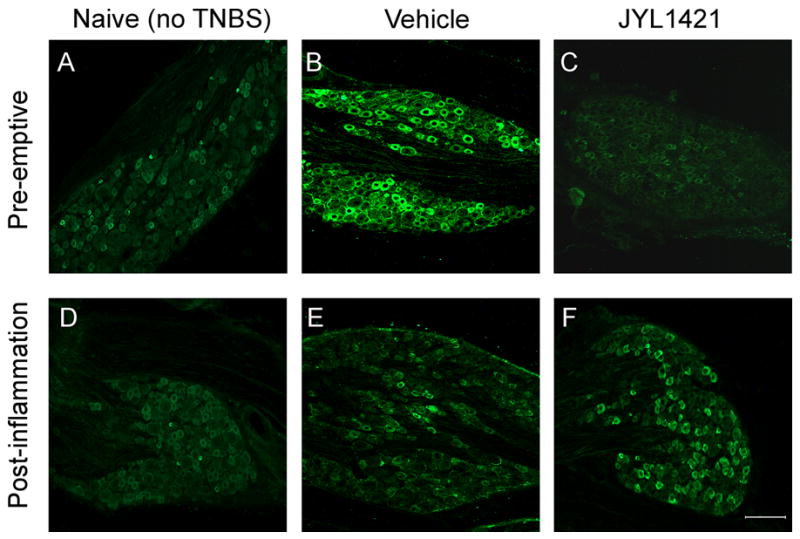

DRG in the T13-L1 spinal segments of vehicle control rats that received TNBS revealed intense staining for TRPV1 with a significantly higher immunoreactive profile (69.1±4.6%) compared to naïve (non-TNBS) rats (45.8±5.1%, p<0.05). Only 28.6±3.9 % of total DRG neuron profiles were immunoreactive for TRPV1 in rats treated with preemptive JYL1421. This was significantly lower than the vehicle control group (p<0.05, Fig. 6A and 7A–C). A similar distribution was seen in the L6-S1 DRG with a significant increase in the TRPV1 immunoreactive profile following TNBS in the vehicle control (66.4±4.2%) compared to naïve (41.3±3.0%). The percentage of TRPV1-positive neurons in the L6-S1 segments of the rats with pre-emptive JYL1421 was also significantly lower than the corresponding vehicle group (32.3±2.3%, p<0.05) (Fig. 6A).

Figure 6.

Percentage of TRPV1–immunoreactive neurons per total DRG neuronal profile in the thoracolumbar (T13-L1) and lumbosacral (L6-S1) spinal segments in naïve and TNBS treated rats. A. Following TNBS there was a significant increase in the TRPV1 immunoreactivity in the vehicle treated groups (*p<0.05 vs naive). Pre-emptive administration of JYL1421 significantly decreased the TRPV1 expression when compared to naïve and vehicle treated rats (#p<0.05). B. There was no difference in the TRPV1 immunoreactivity in the post-inflammation JYL1421 and vehicle treated group when compared to naïve (p>0.05 vs naive).

Figure 7.

TRPV1 expression in the T13- L1 DRG in naïve rats (A and D) and following intracolonic TNBS. The proportion of TRPV1-immunoreactive neurons (green) is increased following inflammation with TNBS in the JYL1421 vehicle treated rats (B) and is prevented by pre-emptive administration of JYL1421(C). TRPV1 expression returned to baseline in the post-inflammation vehicle control (E) and was no different than JYL1421 treated rats (F). Scale bar, 100μm.

In the post-inflammation groups, the TRPV1 immmunoreactivity following TNBS in the vehicle group appeared to return to baseline and did not differ from the naïve rats in both the T13-L1 and L6-S1 spinal segments. Similarly, post-inflammation treatment with JYL1421 did not alter the immunoreactive profiles when compared to vehicle or naïve (Figure 6B and 7D–F).

Discussion

Our results demonstrate that:

One week following intracolonic TNBS there is severe colonic inflammation with an increase in MPO as well as a significant increase in visceral sensitivity to mechanical distension, intraluminal capsaicin and acidic saline (pH 5.0).

The TRPV1 immunoreactivity in the thoraco-lumbar and lumbo-sacral DRGs in vehicle treated rats significantly increases one week following TNBS.

Pre-treatment with the TRPV1 receptor antagonist JYL1421 (10μmol/kg) prevents the visceral hypersensitivity to intraluminal mechanical and chemical stimulation, as well as the colonic inflammation and the increase in TRPV1 immunoreactivity in DRG.

Administration of JYL1421 (10μmol/kg) seven days after TNBS improves microscopic colonic inflammation and significantly decreases the visceral hypersensitivity to mechanical distension of the colon compared to vehicle controls, but does not fully attenuate the VMR to mechanical or chemical stimuli to its pre-TNBS response.

Two weeks following TNBS, TRPV1 immunoreactivity in the thoraco-lumbar and lumbo-sacral DRG in the post-inflammation JYL1421 treated rats is no different from that of vehicle or naïve control.

The main observation of this study is that the colonic inflammation with TNBS induces up-regulation of the TRPV1 receptors in the DRG with subsequent visceral hyperalgesia to mechanical and chemical stimuli and that these changes are prevented by the TRPV1 receptor antagonist JYL1421. This selective TRPV1 receptor antagonist has been previously shown to be effective in vivo in the rat (Jakab et al., 2005). The current study is in accordance with previous reports of TRPV1 antagonists and inflammation. For example, the TRPV1 competitive antagonist capsazepine, given systemically, reduces macroscopic and microscopic changes in a mouse model of DSS-induced colitis (Kimball et al., 2004). In a model of TNBS colitis, a single enema of capsazepine given one hour following TNBS attenuates the severity of colitis in Sprague-Dawley rats (Fujino et al., 2004). The same group previously demonstrated that capsazepine enemas in adult rats exposed to DSS prevents the expected colitis while neonatal denervation with capsaicin prevents DSS colitis (Kihara et al., 2003). However, capsazepine used in theses previous studies is a relatively weak antagonist with limited selectivity since it also inhibits acetylcholine receptors, voltage-gated Ca2+ channels, and hyperpolarization-activated cyclic nucleotide gated channels (McIntyre et al., 2001; Liu and Simon, 1997; Docherty et al., 1997; Gill et al., 2004). Nevertheless, these results, along with the current study, suggest that TRPV1 receptors in primary sensory afferents may be required for the development of experimental colitis. What is not clear, however, is the effects of a selective TRPV1 receptor antagonist on the development and maintenance of mechanical and chemical hyperalgesia following transmural colonic inflammation.

Multiple studies have investigated the visceral hypersensitivity to mechanical distension that results from experimental colitis with TNBS and other chemicals, but few have investigated the sensitivity to intraluminal chemicals (Gschossmann et al., 2004; Gschossmann et al., 2002; Liebregts et al., 2005; Miampamba et al., 1998). The duration of colitis and mechanical hyperalgesia has been inconsistent and appears to be dependent on the model and the strain of animals used or the type of chemicals. Similar to previously published reports, we found multifocal areas of necrosis, diffuse inflammatory infiltrates and loss of epithelium seven days following intracolonic TNBS in the distal colon of vehicle treated animals (Menozzi et al., 2006; Adam et al., 2006). The colitis and visceral hyperalgesia persisted for at least two weeks following TNBS in the control rats. This is also consistent with a previous study in Sprague-Dawley rats that demonstrated persistent colitis and visceral hyperalgesia for up to 4 weeks following intracolonic TNBS (Zhou et al., 2006).

The TRPV1 receptor is known to be a key mediator involved in the development of neurogenic inflammation (Davis et al., 2000). In response to stimulation, the TRPV1 channel depolarizes sensory neurons and either directly or indirectly initiates neuropeptide release from the afferent terminals (Szallasi and Blumberg, 1999). TRPV1 positive nerve fibers that co-express tachykinins (substance P and neurokinins) and calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) are not only seen in primary sensory neurons but also in intrinsic gastrointestinal neurons (Funakoshi et al., 2006). In rats TNBS in the distal colon results in a significant increase in CGRP immunoreactivity in bladder afferent neurons in lumbosacral DRG (Qiao and Grider, 2007). The release of neuropeptides such as CGRP (involved in vascular dilatation) or substance P (increases vascular permeability and plasma extravasation) could be mediated by the activation of TRPV1 in the same sensory nerve fibers (Geppetti and Trevisani, 2004). In fact, daily administration of the NK2 receptor antagonist SR 48968 also reduces colonic inflammation following TNBS (Mazelin et al., 1998). Since the activation of TRPV1 receptors contributes to the inflammatory cascade, pre-emptive dosing of JYL1421 in the current study likely prevented activation and up-regulation of TRPV1 and the subsequent neurogenic inflammation (Landau et al., 2007).

Increased expression of the TRPV1 receptor has been previously shown in rat DRG following peripheral inflammation as well as with noxious acid challenge in the stomach (Ji et al., 2002; Amaya et al., 2003; Schicho et al., 2004). This up-regulation involves increased translation and transport of TRPV1 to the peripheral nociceptor terminal where it contributes to the maintenance of inflammatory hyperalgesia and appears to be regulated by nerve growth factor (NGF) and p38MAP kinase (Ji et al., 2002). Interestingly, intra-peritoneal injection of anti-NGF prevents the development of visceral hyperalgesia following TNBS in Wistar rats (Delafoy et al., 2003). In humans, increased expression of TRPV1 in the mucosa and intrinsic neurons can be seen in patients with esophageal pain, rectal pain and intestinal inflammation (Mattthews et al., 2004; Chan et al., 2003; Domotor et al., 2005; Yiangou et al., 2001). Whether this increase in receptor expression is solely responsible for the chronic hyperalgesia remains unclear. In the current study, prevention of the inflammatory cascade with pre-emptive JYL1421 as well as absence of TRPV1 up-regulation in primary sensory neurons likely accounts for the absence of visceral hypersensitivity.

We were interested not only in the effects of the selective TRPV1 antagonist JYL1421 in preventing inflammation, receptor expression, and in the development of visceral hyperalgesia, but also on its effects once the colitis had been established. There is convincing evidence that the TRPV1 receptors contribute to noxious mechanical stimuli in the colon. Neonatal capsaicin treatment damages small-diameter SP and CGRP containing primary sensory neurons and prevents hypersensitivity following TNBS (Delafoy et al., 2003). Also, the sensitivity of colon afferent fibers to circumferential stretch is significantly reduced in TRPV1 knockout mice (Jones et al., 2005). In the present study, colonic inflammation significantly improved with daily dosing of JYL1421 in the post-inflammation group. While the response to mechanical distension was significantly attenuated in the post-inflammation JYL1421 treated rats when compared to vehicle control, these rats also demonstrated a persistent visceral hyperalgesia compared to their baseline responses. This finding is supported by a previous study showing that inflammation of the colon with TNBS sensitizes primary visceral afferents to CRD (Coutinho et al., 2000). The visceral hyperalgesia to intraluminal capsaicin and pH 5.0 saline was also significant in the post-inflammation groups when compared to naïve rats. Interestingly, at the end of treatment (two weeks), the TRPV1 expression in the T13-L1 and L6-S1 DRG returned to baseline in all groups and was no different from naïve rats. A persistent increase in TRPV1 immunoreactivity and protein expression in the thoracolumbar and lumbosacral DRG has been previously suggested to be responsible for visceral hyperalgesia in adult rats treated with intracolonic acetic acid during the neonatal period (Winston et al., 2007). The present data, however, suggests that persistent up-regulation of the TRPV1 receptors in primary sensory neurons, at least in adult rats, may not be solely responsible for the chronic hypersensitivity following inflammation. Several possibilities exist to explain these findings. First, sensitization of the channels could have occurred during the inflammatory process. Phoshorylation of the TRPV1 receptors is a mechanism of sensitization that affects receptor function and can occur through PKA or PKC pathways (Lopshire and Nicol, 1998; De Petrocellis et al., 2001; Bhave et al., 2002; Vellani et al., 2001). Thus, phosphorylation of the TRPV1 receptor in either intrinsic or extrinsic pathways following inflammation can result in tonic activation and an exaggerated VMR to intraluminal capsaicin and pH 5.0saline compared to naïve non-sensitized rats. Second, since expression of TRPV1 was examined only in the primary sensory neurons in the current study, it is possible that either sensitization or up-regulation of the TRPV1 receptors could have occurred at the spinal cord or in mucosal and myenteric TRPV1 receptors and that could account for the observed colonic hyperalgesia. In humans, TRPV1 immunoreactivity is increased in colonic nerve fibers of patients with active IBD (Yiangou et al., 2001). The increased response to not only CRD, but also capsaicin and acidic saline, chemicals known to selectively activate the TRPV1 receptors, further supports the involvement of these receptors in hyperalgesia following colitis. Further, the hypersensitivity to intraluminal capsaicin in sensitized animals was attenuated by acute dosing of JYL1421 and demonstrates that the hypersensitivity to intraluminal capsaicin occurs selectively through the TRPV1 channels in the primary sensory neurons or possibly in the myenteric plexus. Third, the TRPV1 receptors may play a role in the initial inflammation and hypersensitivity but other putative receptors such as glutamate (NMDA) or tachykinin (NK1 and NK2) receptors, may play a more significant role in maintaining the visceral hypersensitivity in chronic state. This is also supported by ineffectiveness of acute JYL1421 in attenuating the mechanical hyperalgesia to CRD. In fact, there is known up-regulation of the NMDA-NR1 receptor gene expression in the colonic myenteric neurons following TNBS colitis in rats (Zhou et al., 2006a; Zhou et al., 2006b). Further, the activity of NMDA receptors in DRG neurons that innervate the inflamed colon following TNBS is increased threefold (Li et al., 2006). Because the terminals of TRPV1-positive primary afferents are glutaminergic and contact spinal neurons co-expressing NK1 and ionotropic glutamate receptors, potentiation of these receptors, known to mediate visceral nociception, could occur following chronic inflammation (Hwang et al., 2004). Peripheral tachykinin (NK2) receptors also contribute to the sensitization of colonic afferents following inflammation (Laird et al., 2001). This is further supported by evidence showing that following TNBS colitis, the NK2 receptor antagonist MEN 11420 given immediately prior to CRD, attenuates the hypersensitivity to mechanical distension without sufficient time to affect inflammation (Toulouse et al., 2000). This complex process involving multiple neurotransmitter systems along pain pathways is still not well understood. Our current results do not enable us to affirm a precise mechanism or all the receptors involved, but do suggest an important role of the TRPV1 receptors in primary sensory neurons in the inflammatory cascade and subsequent hypersensitivity, at least in the acute phase. Finally, in the present study, we must also consider that since the hypersensitivity to mechanical distension in the post-inflammation group was lower in JYL1421 treated rats at 30–60mmHg compared to vehicle treated rats, that perhaps more prolonged or higher dosing of JYL1421 may in fact be required to attenuate the hypersensitivity that was observed two weeks following TNBS.

The present findings provide new information regarding the role of a potent TRPV1 antagonist in preventing and attenuating colonic inflammation and subsequent visceral hypersensitivity to mechanical and chemical stimuli in the colon. Further studies are clearly needed to investigate the precise role of altered function of TRPV1 and TRPV1-expressing sensory neurons following inflammation. It appears, however, that these receptors may indeed be important in developing useful therapeutic targets for the treatment of IBD and post-infectious IBS.

Acknowledgments

Grant Support: The work was supported by Children’s Research Institute grant awarded to Dr. Adrian Miranda and NIH RO1 (DK062312-01As) awarded to Dr. Jyoti N. Sengupta.

List of abbreviations

- TRPV1

transient receptor potential vanilloid 1

- EMG

electromyographic

- CRD

colorectal distension

- TNBS

trinitrobenzenesulfonic acid

- VMR

visceromotor response

- DRG

dorsal root ganglia

- IBS

irritable bowel syndrome

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Adam B, Liebregts T, Gschossmann JM, Krippner C, Scholl F, Ruwe M, Holtmann G. Severity of mucosal inflammation as a predictor for alterations of visceral sensory function in a rat model. Pain. 2006;123:179–186. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2006.02.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amaya F, Oh-hashi K, Naruse Y, Iijima N, Ueda M, Shimosato G, Tominaga M, Tanaka Y, Tanaka M. Local inflammation increases vanilloid receptor 1 expression within distinct subgroups of DRG neurons. Brain Res. 2003;963:190–196. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(02)03972-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anavi-Goffer S, McKay NG, Ashford ML, Coutts AA. Vanilloid receptor type 1-immunoreactivity is expressed by intrinsic afferent neurones in the guinea-pig myenteric plexus. Neurosci Lett. 2002;319:53–57. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(01)02480-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhave G, Zhu W, Wang H, Brasier DJ, Oxford GS, Gereau RW., 4th cAMP-dependent protein kinase regulates desensitization of the capsaicin receptor (VR1) by direct phosphorylation. Neuron. 2002;35:721–731. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00802-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caterina MJ, Julius D. The vanilloid receptor: a molecular gateway to the pain pathway. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2001;24:487–517. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.24.1.487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caterina MJ, Rosen TA, Tominaga M, Brake AJ, Julius D. A capsaicin-receptor homologue with a high threshold for noxious heat. Nature. 1999;398:436–441. doi: 10.1038/18906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan CL, Facer P, Davis JB, Smith GD, Egerton J, Bountra C, Williams NS, Anand P. Sensory fibres expressing capsaicin receptor TRPV1 in patients with rectal hypersensitivity and faecal urgency. Lancet. 2003;361:385–391. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(03)12392-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coutinho SV, Su X, Sengupta JN, Gebhart GF. Role of sensitized pelvic nerve afferents from the inflamed rat colon in the maintenance of visceral hyperalgesia. Prog Brain Res. 2000;129:375–387. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6123(00)29029-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis JB, Gray J, Gunthorpe MJ, Hatcher JP, Davey PT, Overend P, Harries MH, Latcham J, Clapham C, Atkinson K, Hughes SA, Rance K, Grau E, Harper AJ, Pugh PL, Rogers DC, Bingham S, Randall A, Sheardown SA. Vanilloid receptor-1 is essential for inflammatory thermal hyperalgesia. Nature. 2000;405:183–187. doi: 10.1038/35012076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Petrocellis L, Harrison S, Bisogno T, Tognetto M, Brandi I, Smith GD, Creminon C, Davis JB, Geppetti P, Di Marzo V. The vanilloid receptor (VR1)-mediated effects of anandamide are potently enhanced by the cAMP-dependent protein kinase. J Neurochem. 2001;77:1660–1663. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2001.00406.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delafoy L, Raymond F, Doherty AM, Eschalier A, Diop L. Role of nerve growth factor in the trinitrobenzene sulfonic acid-induced colonic hypersensitivity. Pain. 2003;105:489–497. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(03)00266-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Docherty RJ, Yeats JC, Piper AS. Capsazepine block of voltage-activated calcium channels in adult rat dorsal root ganglion neurones in culture. Br J Pharmacol. 1997;121:1461–1467. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0701272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Domotor A, Peidl Z, Vincze A, Hunyady B, Szolcsanyi J, Kereskay L, Szekeres G, Mozsik G. Immunohistochemical distribution of vanilloid receptor, calcitonin-gene related peptide and substance P in gastrointestinal mucosa of patients with different gastrointestinal disorders. Inflammopharmacology. 2005;13:161–177. doi: 10.1163/156856005774423737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujino K, Takami Y, de la Fuente SG, Ludwig KA, Mantyh CR. Inhibition of the vanilloid receptor subtype-1 attenuates TNBS-colitis. J Gastrointest Surg. 2004;8:842–847. doi: 10.1016/j.gassur.2004.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Funakoshi K, Nakano M, Atobe Y, Goris RC, Kadota T, Yazama F. Differential development of TRPV1-expressing sensory nerves in peripheral organs. Cell Tissue Res. 2006;323:27–41. doi: 10.1007/s00441-005-0013-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geppetti P, Trevisani M. Activation and sensitisation of the vanilloid receptor: role in gastrointestinal inflammation and function. Br J Pharmacol. 2004;141:1313–1320. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0705768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gill CH, Randall A, Bates SA, Hill K, Owen D, Larkman PM, Cairns W, Yusaf SP, Murdock PR, Strijbos PJ, Powell AJ, Benham CD, Davies CH. Characterization of the human HCN1 channel and its inhibition by capsazepine. Br J Pharmacol. 2004;143:411–421. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0705945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gschossmann JM, Adam B, Liebregts T, Buenger L, Ruwe M, Gerken G, Mayer EA, Holtmann G. Effect of transient chemically induced colitis on the visceromotor response to mechanical colorectal distension. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2002;14:1067–1072. doi: 10.1097/00042737-200210000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gschossmann JM, Liebregts T, Adam B, Buenger L, Ruwe M, Gerken G, Holtmann G. Long-term effects of transient chemically induced colitis on the visceromotor response to mechanical colorectal distension. Dig Dis Sci. 2004;49:96–101. doi: 10.1023/b:ddas.0000011609.68882.3a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoshino H, Sugiyama S, Ohara A, Goto H, Tsukamoto Y, Ozawa T. Mechanism and prevention of chronic colonic inflammation with trinitrobenzene sulfonic acid in rats. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 1992;19:717–722. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1681.1992.tb00409.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang SJ, Burette A, Rustioni A, Valtschanoff JG. Vanilloid receptor VR1-positive primary afferents are glutamatergic and contact spinal neurons that co-express neurokinin receptor NK1 and glutamate receptors. J Neurocytol. 2004;33:321–329. doi: 10.1023/B:NEUR.0000044193.31523.a1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jakab B, Helyes Z, Varga A, Bolcskei K, Szabo A, Sandor K, Elekes K, Borzsei R, Keszthelyi D, Pinter E, Petho G, Nemeth J, Szolcsanyi J. Pharmacological characterization of the TRPV1 receptor antagonist JYL1421 (SC0030) in vitro and in vivo in the rat. Eur J Pharmacol. 2005;517:35–44. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2005.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ji RR, Samad TA, Jin SX, Schmoll R, Woolf CJ. p38 MAPK activation by NGF in primary sensory neurons after inflammation increases TRPV1 levels and maintains heat hyperalgesia. Neuron. 2002;36:57–68. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00908-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones RC, 3rd, Xu L, Gebhart GF. The mechanosensitivity of mouse colon afferent fibers and their sensitization by inflammatory mediators require transient receptor potential vanilloid 1 and acid-sensing ion channel 3. J Neurosci. 2005;25:10981–10989. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0703-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kihara N, de la Fuente SG, Fujino K, Takahashi T, Pappas TN, Mantyh CR. Vanilloid receptor-1 containing primary sensory neurones mediate dextran sulphate sodium induced colitis in rats. Gut. 2003;52:713–719. doi: 10.1136/gut.52.5.713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimball ES, Wallace NH, Schneider CR, D’Andrea MR, Hornby PJ. Vanilloid receptor 1 antagonists attenuate disease severity in dextran sulphate sodium-induced colitis in mice. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2004;16:811–818. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2004.00549.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirkup AJ, Brunsden AM, Grundy D. Receptors and transmission in the brain-gut axis: potential for novel therapies. I. Receptors on visceral afferents. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2001;280:G787–794. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.2001.280.5.G787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laird JM, Olivar T, Lopez-Garcia JA, Maggi CA, Cervero F. Responses of rat spinal neurons to distension of inflamed colon: role of tachykinin NK2 receptors. Neuropharmacology. 2001;40:696–701. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(00)00205-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landau AM, Yashpal K, Cahill CM, St Louis M, Ribeiro-da-Silva A, Henry JL. Sensory neuron and substance P involvement in symptoms of a zymosan-induced rat model of acute bowel inflammation. Neuroscience. 2007;145:699–707. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2006.11.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lembo T, Munakata J, Mertz H, Niazi N, Kodner A, Nikas V, Mayer EA. Evidence for the hypersensitivity of lumbar splanchnic afferents in irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology. 1994;107:1686–1696. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(94)90809-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J, McRoberts JA, Ennes HS, Trevisani M, Nicoletti P, Mittal Y, Mayer EA. Experimental colitis modulates the functional properties of NMDA receptors in dorsal root ganglia neurons. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2006;291:G219–228. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00097.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liebregts T, Adam B, Bertel A, Jones S, Schulze J, Enders C, Sonnenborn U, Lackner K, Holtmann G. Effect of E. coli Nissle 1917 on post-inflammatory visceral sensory function in a rat model. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2005;17:410–414. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2005.00638.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu L, Simon SA. Capsazepine, a vanilloid receptor antagonist, inhibits nicotinic acetylcholine receptors in rat trigeminal ganglia. Neurosci Lett. 1997;228:29–32. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(97)00358-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopshire JC, Nicol GD. The cAMP transduction cascade mediates the prostaglandin E2 enhancement of the capsaicin-elicited current in rat sensory neurons: whole-cell and single-channel studies. J Neurosci. 1998;18:6081–6092. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-16-06081.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo H, Cheng J, Han JS, Wan Y. Change of vanilloid receptor 1 expression in dorsal root ganglion and spinal dorsal horn during inflammatory nociception induced by complete Freund’s adjuvant in rats. Neuroreport. 2004;15:655–658. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200403220-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthews PJ, Aziz Q, Facer P, Davis JB, Thompson DG, Anand P. Increased capsaicin receptor TRPV1 nerve fibres in the inflamed human oesophagus. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;16:897–902. doi: 10.1097/00042737-200409000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazelin L, Theodorou V, More J, Emonds-Alt X, Fioramonti J, Bueno L. Comparative effects of nonpeptide tachykinin receptor antagonists on experimental gut inflammation in rats and guinea-pigs. Life Sci. 1998;63:293–304. doi: 10.1016/s0024-3205(98)00271-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCafferty D-M, Sharkey KA, Wallace JL. Beneficial effects of local or systemic lidocaine in experimental colitis. Am J Physiol. 1994;266:G560–567. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1994.266.4.G560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McIntyre P, McLatchie LM, Chambers A, Phillips E, Clarke M, Savidge J, Toms C, Peacock M, Shah K, Winter J, Weerasakera N, Webb M, Rang HP, Bevan S, James IF. Pharmacological differences between the human and rat vanilloid receptor 1 (VR1) Br J Pharmacol. 2001;132:1084–1094. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0703918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McVey DC, Vigna SR. The capsaicin VR1 receptor mediates substance P release in toxin A-induced enteritis in rats. Peptides. 2001;22:1439–1446. doi: 10.1016/s0196-9781(01)00463-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menozzi A, Pozzoli C, Poli E, Lazzaretti M, Grandi D, Coruzzi G. Long-term study of TNBS-induced colitis in rats: Focus on mast cells. Inflamm Res. 2006;55:416–422. doi: 10.1007/s00011-006-6017-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miampamba M, Parr EJ, McCafferty DM, Wallace JL, Sharkey KA. Effect of intracolonic benzalkonium chloride on trinitrobenzene sulphonic acid-induced colitis in the rat. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1998;12:219–228. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.1998.00311.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ness TJ, Gebhart GF. Colorectal distension as a noxious visceral stimulus: physiologic and pharmacologic characterization of pseudaffective reflexes in the rat. Brain Res. 1988;450:153–169. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(88)91555-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ness TJ, Randich A, Gebhart GF. Further behavioral evidence that colorectal distension is a ‘noxious’ visceral stimulus in rats. Neurosci Lett. 1991;131:13–116. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(91)90349-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olah Z, Karai L, Iadarola MJ. Anandamide activates vanilloid receptor 1 (VR1) at acidic pH in dorsal root ganglia neurons and cells ectopically expressing VR1. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:31163–31170. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M101607200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patterson LM, Zheng H, Ward SM, Berthoud HR. Vanilloid receptor (VR1) expression in vagal afferent neurons innervating the gastrointestinal tract. Cell Tissue Res. 2003;311:277–287. doi: 10.1007/s00441-002-0682-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiao LY, Grider JR. Up-regulation of calcitonin gene-related peptide and receptor tyrosine kinase TrkB in rat bladder afferent neurons following TNBS colitis. Exp eurol. 2007;204:667–679. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2006.12.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ritchie JA, Ardran GM, Truelove SC. Observations on experimentally induced colonic pain. Gut. 1972;13:841. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schicho R, Florian W, Liebmann I, Holzer P, Lippe IT. Increased expression of TRPV1 receptor in dorsal root ganglia by acid insult of the rat gastric mucosa. Eur J Neurosci. 2004;19:1811–1818. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2004.03290.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simren M, Axelsson J, Gillberg R, Abrahamsson H, Svedlund J, Bjornsson ES. Quality of life in inflammatory bowel disease in remission: the impact of IBS-like symptoms and associated psychological factors. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:389–396. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2002.05475.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szallasi A, Blumberg PM. Vanilloid (Capsaicin) receptors and mechanisms. Pharmacol Rev. 1999;51:159–212. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toulouse M, Coelho AM, Fioramonti J, Lecci A, Maggi C, Bueno L. Role of tachykinin NK2 receptors in normal and altered rectal sensitivity in rats. Br J Pharmacol. 2000;129:193–199. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0703040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vellani V, Mapplebeck S, Moriondo A, Davis JB, McNaughton PA. Protein kinase C activation potentiates gating of the vanilloid receptor VR1 by capsaicin, protons, heat and anandamide. J Physiol. 2001;534:813–825. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2001.00813.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vilaseca J, Salas A, Guarner F, Rodriguez R, Malagelada J-R. Participation of thromboxane and other eicosanoid synthesis in the course of experimental inflammatory colitis. Gastroenterology. 1990;98:269–277. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(90)90814-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallace JL, Keenan CM, Gale D, Shoupe TS. Exacerbation of experimental colitis by nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs is not related to elevated leukotriene B4 synthesis. Gastroenterology. 1992;102:18–27. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(92)91779-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallace JL. Release of platelet-activating factor (PAF) and accelerated healing induced by a PAF antagonist in an animal model of chronic colitis. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 1988;66:422–425. doi: 10.1139/y88-071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winston J, Shenoy M, Medley D, Naniwadekar A, Pasricha PJ. The vanilloid receptor initiates and maintains colonic hypersensitivity induced by neonatal colon irritation in rats. Gastroenterology. 2007;132:615–627. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yiangou Y, Facer P, Dyer NH, Chan CL, Knowles C, Williams NS, Anand P. Vanilloid receptor 1 immunoreactivity in inflamed human bowel. Lancet. 2001;357:1338–1339. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(00)04503-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Q, Caudle RM, Moshiree B, Price DD, Verne GN. Phosphorylation of NMDA NR1 subunits in the myenteric plexus during TNBS induced colitis. Neurosci Lett. 2006a;406:250–255. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2006.07.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Q, Caudle RM, Price DD, Del Valle-Pinero AY, Verne GN. Selective up-regulation of NMDA-NR1 receptor expression in myenteric plexus after TNBS induced colitis in rats. Mol Pain. 2006b;2:3–13. doi: 10.1186/1744-8069-2-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]