Abstract

Ultraviolet light is a potent DNA damaging agent that induces bulky lesions in DNA which block the replicative polymerases. In order to ensure continued DNA replication and cell viability, specialized translesion polymerases bypass these lesions at the expense of introducing mutations in the nascent DNA strand. A recent study has shown that the N-terminal sequences of the nuclear translesion polymerases Rev1p and Pol ζ can direct GFP to the mitochondrial compartment of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. We have investigated the role of these polymerases in mitochondrial mutagenesis. Our analysis of mitochondrial DNA point mutations, microsatellite instability, and the spectra of mitochondrial mutations indicate that these translesion polymerases function in a less mutagenic pathway in the mitochondrial compartment than they do in the nucleus. Mitochondrial phenotypes resulting from the loss of Rev1p and Pol ζ suggest that although these polymerases are responsible for the majority of mitochondrial frameshift mutations, they do not greatly contribute to mitochondrial DNA point mutations. Analysis of spontaneous mitochondrial DNA point mutations suggests that Pol ζ may play a role in general mitochondrial DNA maintenance. In addition, we observe a 20-fold increase in UV-induced mitochondrial DNA point mutations in rev deficient strains. Our data provides evidence for an alternative damage tolerance pathway that is specific to the mitochondrial compartment.

Keywords: mtDNA repair, mutagenesis, translesion synthesis, UV damage, Rev1p, Pol ζ

1. Introduction

DNA is constantly damaged by a variety of endogenous and exogenous sources. Lesions in DNA are converted into mutations via error-prone mechanisms of damage tolerance [1]. Translesion polymerases are specialized enzymes that are required for DNA synthesis across from unrepaired damage. These polymerases are minimally processive and frequently have a specific insertion preference, which may lead to mutations in the newly replicated strand. Since replicative polymerases have stringent requirements for their substrates and cannot accommodate bulky DNA lesions in their active sites, translesion synthesis (TLS) is imperative for lesion bypass. These highly conserved polymerases have been identified in organisms from bacteria to humans. The consequence of error-prone TLS is demonstrated by mutations in error-free pathways that lead to human diseases, including skin cancers and a variant form of xeroderma pigmentosum (XP-V) caused by the absence of a functional non-mutagenic translesion polymerase Pol η [2,3].

Here we focus on the yeast translesion polymerases Rev1p and Pol ζ, comprised of Rev3p and Rev7p. Genes encoding these proteins were identified in genetic screens for mutants deficient in reversions of specific nuclear mutations (REVersionless) [4,5]. These genes are in the RAD6 epistasis group and mutations in any of these three genes lead to a dramatic decrease in UV-induced mutagenesis in the nuclear genome [4–8]. The sequence of REV3 revealed homology with DNA polymerase catalytic domains suggesting that it may contain polymerase activity [9]. In 1996, polymerase activity was demonstrated with the addition of the accessory protein Rev7p [10], and the resulting complex was named Pol ζ. This polymerase is able to replicate past UV-induced DNA lesions, although the synthesis is usually mutagenic [11].

Rev1p is a Y-family polymerase that exhibits deoxycytidyl transferase activity, preferentially inserting dCTP across from abasic sites [12]. The pyrimidine dimer bypass activity of Pol ζ is further enhanced by the addition of Rev1p [12]. However, since the deoxycytidyl transferase activity of Rev1p is not essential for UV mutagenesis, the mechanism for its role in Pol ζ-dependent translesion synthesis remains unclear [13].

In 1987, it was shown that a rev3 mutant strain resulted in a decreased frequency of EMS-induced reversions of a specific mitochondrial mutation [14]. A subsequent study indicated that there was a reduction in the frequency of both spontaneous and UV-induced mitochondrial frameshifts in rev mutant strains [15]. However, in spite of the reduction in frameshift mutations in the rev mutant strains as compared to wild-type, there was still an induction of mitochondrial frameshifts in response to UV light in the rev deficient strains. In addition, the N-termini of Rev1p, Rev3p, and Rev7p could target GFP to the mitochondrial compartment [15].

In this study we analyze the role of Rev1p and Pol ζ in mitochondrial mutagenesis. If these proteins perform a similar function in the mitochondria, as they do in the nucleus, we would expect a decrease in UV-induced mitochondrial DNA mutations in strains lacking the components of this pathway. Here we analyze the effects of deleting the rev genes on spontaneous and UV-induced mitochondrial DNA stability and maintenance.

2. Material and methods

2.1. Growth Media

All growth media used in this study are as follows. YPD and YPG medium contained 1% Bacto™ yeast extract (Becton, Dickson and Company), 2% Bacto™ peptone (Becton, Dickson and Company), and 2% dextrose or 2% glycerol, respectively. YPG + 0.1% is YPG medium supplemented with 0.1% dextrose. Synthetic dextrose and synthetic glycerol growth medium contained 0.17% Difco™ yeast nitrogen base (Becton, Dickson and Company), 0.5% ammonium sulfate, the appropriate amino acids as described [16], and 2% dextrose or 2% glycerol, respectively. The final pH of the synthetic growth medium was adjusted to 5.6. The expression of the kanMX gene was selected for on media containing 200 mg/L Gibco™ geneticin (Invitrogen). Erythromycin resistant mutants were selected on YG plates containing 50mM sodium phosphate buffer (pH 6.5) and 4 g/L erythromycin (MP Biomedicals, LLC) [17]. Canavanine resistant mutants were selected on synthetic medium lacking arginine and supplemented with 60 μg/mL L-canavanine sulfate (Sigma).

2.2. Strains

All S. cerevisiae strains used in this study (Table 1) are isogenic with DFS188 (MATa ura3-52 leu2-3, 112 lys2 his3 arg8::hisG; ρ+) a derivative of D273-10B, except EAS738 and EAS736, which are derived from DFS160 [18]. The rev1-Δ, rev3-Δ, and rev7-Δ strains were constructed by one-step gene transplacement of the wild-type gene with the kanMX marker using standard methods [19]. The GT+2 respiring microsatellite reporter (EAS736) was constructed as described previously except that the frameshift mutation results in translation in the +2 frame [20]. To introduce the mitochondrial reporter constructs by cytoduction, the rev1-Δ, rev3-Δ, and rev7-Δ strains were first made ρ0 by treatment with ethidium bromide as described previously [21]. These strains were then mated to the DFS160 reporter constructs EAS738 (arg8m::(GT)16+1) and EAS736 (arg8m::(GT)16+2). Haploid cytoductants with the DFS188 nuclear background and the mitochondrial reporter were selected on the synthetic glycerol media lacking adenine and screened for a Lys− phenotype on synthetic dextrose lacking lysine.

Table 1.

Strains used in this study

| Strain | Relevant Nuclear Genotype | Relevant Mitochondrial Genotype | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| DFS188 | MATa ura3-52 leu2-3, 112 lys2 his3 arg8::hisG | ρ+ | [23] |

| DFS160 | MATα ade2-101 leu2Δ ura3-52 arg8-Δ::URA3 kar1-1 | ρ0 | [18] |

| TF236 | ino1::HIS3 arg8::hisG pet9 (op1) ura3-52 lys2 cox3::arg8m-1 | ρ+ | [37] |

| EAS738 | MATα ade2-101 leu2Δ ura3-52 arg8-Δ::URA3 kar1-1 | ρ+ arg8m::(GT)16+1 | [20] |

| EAS744 | MATa ura3-52 leu2-3, 112 lys2 his3 arg8::hisG | ρ+ arg8m::(GT)16+1 | [20] |

| EAS736 | MATα ade2-101 leu2Δ ura3-52 arg8-Δ::URA3 kar1-1 | ρ+ arg8m::(GT)16+2 | This Study |

| EAS741 | MATa ura3-52 leu2-3, 112 lys2 his3 arg8::hisG | ρ+ arg8m::(GT)16+2 | This Study |

| NPY054 | MATa ura3-52 leu2-3, 112 lys2 his3 arg8::hisG ARG8 | ρ+ | [38] |

| LKY118 | DFS188 rev1-Δ::kanMX | ρ+ | This Study |

| LKY185 | DFS188 rev1-Δ::kanMX ARG8 | ρ+ | This Study |

| LKY132 | DFS188 rev1-Δ::kanMX | ρ+ arg8m::(GT)16+1 | This Study |

| LKY131 | DFS188 rev1-Δ::kanMX | ρ+ arg8m::(GT)16+2 | This Study |

| EAS798 | DFS188 rev3-Δ::kanMX | ρ+ | This Study |

| LKY125 | DFS188 rev3-Δ::kanMX ARG8 | ρ+ | This Study |

| LKY151 | DFS188 rev3-Δ::kanMX | ρ+ arg8m::(GT)16+1 | This Study |

| LKY150 | DFS188 rev3-Δ::kanMX | ρ+ arg8m::(GT)16+2 | This Study |

| LKY119 | DFS188 rev7-Δ::kanMX | ρ+ | This Study |

| LKY186 | DFS188 rev7-Δ::kanMX ARG8 | ρ+ | This Study |

| LKY133 | DFS188 rev7-Δ::kanMX | ρ+ arg8m::(GT)16+1 | This Study |

| LKY149 | DFS188 rev7-Δ::kanMX | ρ+ arg8m::(GT)16+2 | This Study |

2.3. Survival after UV exposure

Average percent survival was determined for each experiment by calculating the number of viable cells after UV exposure. The percent survival within each strain was comparable for the different experiments, therefore the average percent survival is only shown in Table 2. The survival of the rev deficient strains at 50 J/m2 (Mineralight lamp shortwave UV 254nm, UVP) is similar to previously published results [4,5].

Table 2.

UV-Induced Respiration Loss

| Strains | Survival | Spontaneous Respiration Loss | UV-Induced Respiration Loss |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wild-Type | 70.5 | 0.7 | 6.0 |

| rev1-Δ | 1.0 | 1.3 | 1.2 |

| rev3-Δ | 1.6 | 0.5 | < 0.1 |

| rev7-Δ | 1.1 | 1.3 | < 0.1 |

Values for survival and respiration loss are indicated as percents.

Decreases in UV-induced respiration loss of the rev deficient strains are significant as determined by unpaired t-tests (p < 0.00005).

2.4. UV-induced frequency of respiration loss

Determination of UV-induced frequency of respiration loss was performed as described previously [22]. Briefly, independent colonies were isolated on YPG and inoculated into YPG liquid medium. They were grown to saturation at 30°C and dilutions were plated on YPG + 0.1% dextrose media. These plates were exposed to a fluence of 50 J/m2 UV-C and incubated in the dark at 30°C for 3 days. In all UV experiments, non-irradiated control plates were also incubated in the dark at 30°C for the same length of time. All plates were scored for the percent respiration loss. For each experiment five or more independent cultures were used and each experiment was performed two or more times.

2.5. Determination of UV-induced mutation frequencies

To determine UV-induced mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) point mutations, independent colonies were isolated on YPG, inoculated into YPG liquid medium, and grown to saturation at 30°C. Appropriate dilutions were plated on YPG and YG + 4 g/L erythromycin. These plates were exposed to a fluence of 50 J/m2 UV-C and incubated in the dark at 30°C for 7 days. To examine the UV sensitivity of the erythromycin resistant colonies, 15 independent colonies were inoculated into YPG liquid medium and grown to saturation at 30°C. Appropriate dilutions were plated on YPG and exposed to a fluence of 50 J/m2 UV-C and incubated in the dark at 30°C for 3 days.

To determine the frequency of frameshifts in microsatellite tracts using the GT+1 and GT+2 reporters described above, independent colonies were isolated on YPD, inoculated into YPD liquid medium, and grown to saturation at 30°C. Appropriate dilutions were plated on YPD and synthetic dextrose media lacking arginine (SD-Arg). These plates were exposed to a fluence of 50 J/m2 UV-C and incubated in the dark at 30°C for 7 days.

To determine the frequency of UV-induced nuclear mutations, independent colonies were isolated on synthetic dextrose media lacking arginine (SD-Arg) and inoculated into SD-Arg liquid medium. Cultures were grown to saturation at 30°C and dilutions were plated on SD-Arg and SD-Arg containing 60 μg/ml canavanine. The plates were exposed to a fluence of 50 J/m2 UV-C and incubated in the dark at 30°C for 3 days.

The experiments were performed three or more times and each experiment consisted of five or more replicates. The number of new mutations per 107 survivors was calculated by determining the frequency of mutations per 107 cells from both UV-exposed and non-irradiated control cultures. The preexisting mutations, as determined by the unirradiated control, were subtracted from the experimental values.

2.6. Fluctuation analysis to determine spontaneous mutation rates

The rates of spontaneous mtDNA point mutations were measured by erythromycin resistance (ER) as described previously [23]. Briefly, independent colonies were isolated on YPG and inoculated into YPG liquid medium. Cultures were grown to saturation at 30°C and dilutions were plated on YPG and YG + 4 g/L erythromycin. The plates were incubated for 7 days at 30°C. The rates of ER were determined using the method of the median [24].

For the determination of nuclear mutation rates, independent colonies were isolated on synthetic dextrose medium lacking arginine (SD-Arg) and inoculated into SD-Arg liquid medium. Cultures were grown to saturation at 30°C and dilutions were plated on SD-Arg and SD-Arg containing 60 μg/ml canavanine. The plates were incubated at 30°C for 3 days. The rates of nuclear point mutations as measured by canavanine resistance (CanR) were determined using the method of the median [24]. Each experiment consisted of 20 independent cultures and the rates are given as an average of two or more independent experiments.

2.7. Sequencing of erythromycin resistant colonies

The spectrum of mtDNA point mutations was analyzed by sequencing a 200 bp region of the 21S rRNA gene within the mitochondrial genome. PCR was performed on ER colonies derived from independent cultures using primers 5′-GGTAAATAGCAGCCTTATTATG-3′ and 5′-CGATCTATCTAATTACAGTAAAGC-3′ to amplify the region from 1797 to 1995 and primers 5′-CTATGTTTGCCACCTCGATGTC-3′ and 5′-CAATAGATACACCATGGGTTGATTC-3′ to amplify the region from 3895 to 4107. The amplified fragments were sequenced using primer: 5′-GAGGTCCCGCATGAATGACG-3′ for region 1797 to 1995 and 5′-CTATGTTTGCCACCTCGATGTC-3′ for region 3895 to 4107.

2.8. Statistical analyses

All statistical analysis was performed with InStat 3 for Macintosh (GraphPad Software, Inc., San Diego, CA). Unpaired t-tests were used to calculate a two-tailed p value in the comparison of average rates or frequencies. Comparison of the mutational spectra was performed using chi-square analysis.

3. Results

3.1. Deletion of rev1, rev3, or rev7 reduces UV-induced respiration loss

Yeast cells in which mitochondrial function has been compromised are respiratory deficient. Such strains can be identified by their failure to utilize a non-fermentable carbon source for growth. Mutations in mtDNA, including point mutations, large-scale rearrangements or deletions, and the complete loss of mtDNA, have been demonstrated to result in respiratory-deficient yeast strains. To determine whether rev1, rev3, or rev7 mutants affected respiration capacity, we measured the frequency of respiration loss after exposure to UV light. Consistent with a role for these proteins in error-prone recovery, deletion of rev1, rev3, or rev7 significantly reduced the respiration loss phenotype seen in the wild-type (Table 2). These results suggest that Rev1p and Pol ζ contribute to general mitochondrial genome instability, however, the nature of the mutations that confer respiration loss in individual cells is not known, and is unlikely to simply reflect an accumulation of point mutations [20]. We therefore, examined the effect of loss of Rev1p, Rev3p and Rev7p on specific types of mitochondrial mutations.

3.2. Deletion of rev1, rev3, or rev7 suppresses spontaneous and UV-induced mitochondrial microsatellite instability

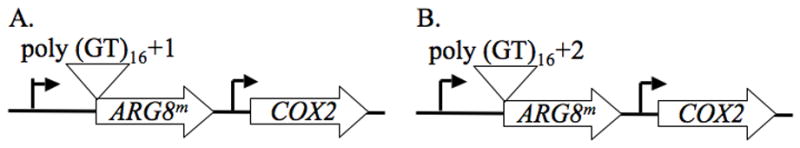

Rev1p and Pol ζ are responsible for the majority of UV-induced nuclear frameshift mutations [25]. Pol ζ is also responsible for essentially all the spontaneous nuclear frameshift mutations [25]. Therefore, we analyzed the effect of deleting Pol ζ and Rev1p on mitochondrial frameshifts in microsatellite tracts. In these reporters, the ARG8m gene containing a poly GT tract 9 base pairs down stream of its start is inserted upstream of the intact COX2 gene, with its expression driven by the COX2 promoter (Fig. 1). Insertions or deletions within this microsatellite that shift the ARG8m gene into the correct reading frame will result in cells that are phenotypically Arg+. Two different microsatellite reporters were used, since reversion to wildtype will require different types of mutations in each reporter [23]. It is important to note that the poly GT tracts in these reporters are flanked by 4 pyrimidine base pairs; therefore TLS of pyrimidine dimers upstream of the repetitive tract may cause frameshifts within the tract.

Fig. 1.

Effect of deleting REV1, REV3, and REV7 on mitochondrial microsatellite instability in respiring yeast. The reporters for measuring mitochondrial microsatellite instability are shown. ARG8m is a derivative of the nuclear ARG8 gene, altered to display the codon usage of a mitochondrial gene. This gene is expressed using the COX2 transcriptional and translational signals, and has been inserted 5′ of the intact COX2 gene in the mitochondrial genome. The polyGT sequences have been inserted 9 bp after the translational start. The GT repeats are 32 bp in each reporter but the flanking sequences have been altered to generate a (A) +1 or (B) +2 frameshift.

Using these reporters, we have determined that deletion of the rev genes causes a reduction of both spontaneous and UV-induced microsatellite instability (Table 3). However, UV induction of these frameshifts is still observed in these strains, indicating that another pathway can generate these types of mutations.

Table 3.

Mitochondrial Microsatellite Instability

| GT + 1

|

GT + 2

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spontaneous

|

UV-Induced

|

Spontaneous

|

UV-Induced

|

|||||

| Strains | Average Frequency of Arg+ Frameshifts per 107 Cells | Fold Decrease | Average Frequency of Arg+ Frameshifts per 107 Survivors | Fold Decrease | Average Frequency of Arg+ Frameshifts per 107 Cells | Fold Decrease | Average Frequency of Arg+ Frameshifts per 107 Survivors | Fold Decrease |

| Wild-Type | 48.6 | - | 1026.9 | - | 68.8 | - | 1254.4 | - |

| rev1-Δ | 0.1 | 486.0 | 2.9 | 354.1 | 5.5 | 12.5 | 44.7 | 28.1 |

| rev3-Δ | 3.9 | 12.5 | 45.9 | 22.4 | 24.1 | 2.9 | 54.1 | 23.2 |

| rev7-Δ | 5.9 | 8.2 | 50.3 | 20.4 | 1.3 | 52.9 | 15.1 | 83.1 |

All decreases relative to wildtype are statistically significant as determined by unpaired t-tests (p < 0.05).

3.3. Loss of Pol ζ results in an increase in spontaneous mitochondrial DNA point mutations

Erythromycin is an inhibitor of mitochondrial, but not cytoplasmic, translation. A mutation in either of two specific regions within the mitochondrially-encoded 21S rRNA gene has been shown to confer erythromycin resistance (ER) [26–28]. There are no reported nuclear mutations in yeast that result in ER; therefore, the frequency of ER is often used to estimate the frequency of mitochondrial point mutation.

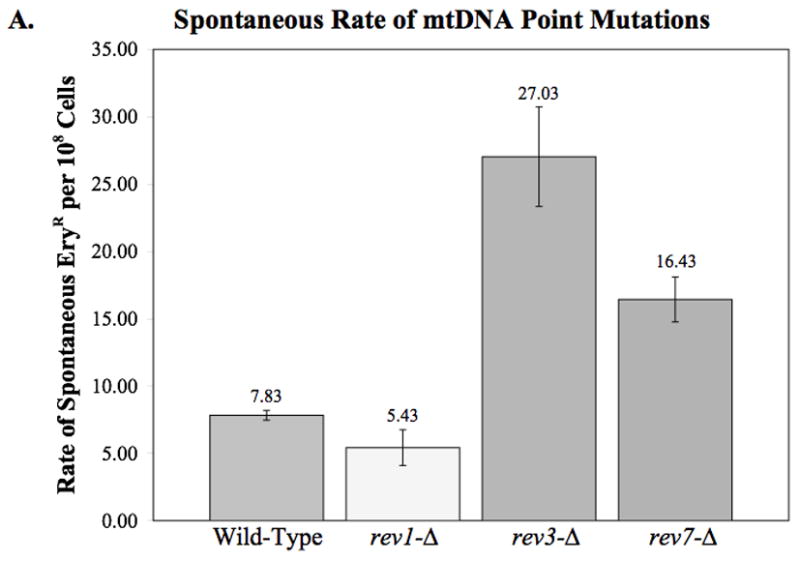

To determine whether deletion of rev1, rev3, or rev7 had an effect on spontaneous mtDNA point mutations, we performed fluctuation analysis to measure the rate of spontaneous ER. This assay revealed that the rev3-Δ and rev7-Δ strains had a significantly greater rate of spontaneous mtDNA point mutations than the wild-type strain (p = 0.035 and 0.029, respectively), while the rev1-Δ strain showed no significant difference from wildtype (Fig. 2A).

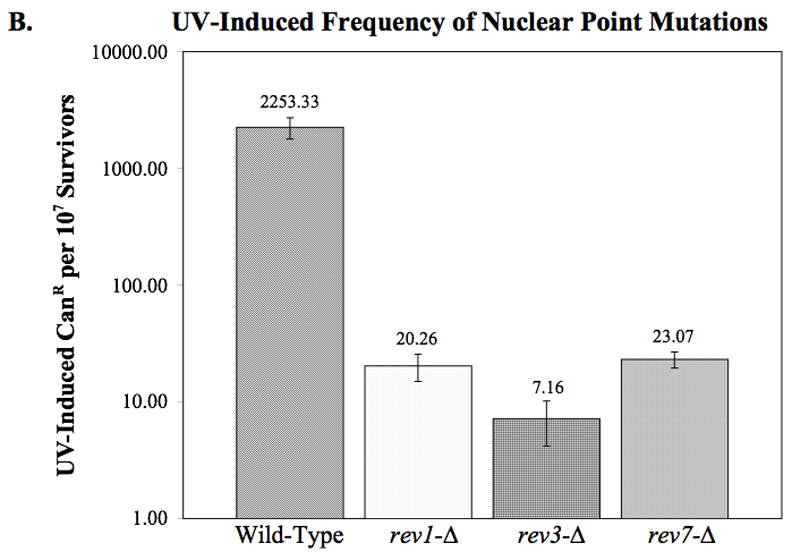

Fig. 2.

Effect of deleting REV1, REV3, and REV7 on mitochondrial DNA point mutations as measured by erythromycin resistance. (A) The spontaneous rate of mtDNA point mutations was determined by fluctuation analysis as described in Materials and Methods. The average rates from two or more independent experiments are plotted. Error bars indicate the SEM. Statistical analysis using unpaired two-tailed t-tests indicate that rev3-Δ and rev7-Δ have a significantly higher rate of mtDNA point mutations than wildtype (p = 0.035 and 0.029, respectively). (B) The UV-induced frequency of mtDNA point mutations as measured by erythromycin resistance. Deletion of REV1, REV3, or REV7 results in a significantly higher frequency of erythromycin resistant colonies per survivor following exposure to 50 J/m2 UV-C (p < 0.001 in all cases). The average frequencies from three independent experiments are plotted. Error bars indicate the SEM.

3.4. Loss of Rev1p or Pol ζ results in increased frequencies of UV-induced mitochondrial erythromycin resistance

The increased spontaneous mutagenesis in the rev3-Δ and rev7-Δ strains was unexpected, as the strains are reported to display a decrease in spontaneous nuclear mutations. To determine whether such mutations are induced by UV exposure, we measured the frequency in which UV-induced ER arose in rev1, rev3, and rev7 deletion strains. Surprisingly, the frequency of mtDNA point mutations per survivor increased 20-fold over the wild-type, to approximately 1000 new mutations per 107 survivors (Fig. 2B). This result argues against a role for these proteins in the generation of UV-induced point mutations. Instead it suggests that these proteins maybe responsible for error-free bypass across these lesions. Furthermore, this provides evidence for a more error-prone mechanism that exists to cope with this damage when Rev1p and Pol ζ are not present. We considered the possibility that ER cells were more resistant to UV light and preferentially survived the treatment. Therefore, independently isolated ER mutants derived from the wild-type strain were tested for their sensitivity to killing by UV light exposure. These strains displayed an average of 60.6% viability in response to UV light, as compared to 70.5% for the original wild-type strain when exposed to the same fluence. We conclude that the ER mutants are not more resistant to UV light, in contrast, our results demonstrate that they are significantly more sensitive (p = 0.038).

3.5. Identification of mutations giving rise to erythromycin resistance and analysis of mutations in the rev1, rev3, and rev7 deletion strains

It was previously reported that a mutation at either of two locations within the 21S rRNA gene leads to ER [26–28]. To determine the spectrum of mutations in spontaneous and UV-induced ER mutants, we amplified the sequences flanking the locations of the previously published ER mutations and sequenced across their length. The spontaneous ER mutations identified in the wild-type strain include base substitutions at positions 1950, 1951, 1952, and a 1 base G insertion in the sequence of Gs at 1949 and 1950, which is similar to that previously reported by Vanderstraeten et al. [29].

Comparison of the spontaneous and UV-induced spectra of mutations within the wild-type, rev1-Δ, rev3-Δ, and rev7-Δ strains indicates that there is a significant increase in the proportion of substitutions at A residues after UV exposure (p = 0.039) (Table 4). Ninety-five percent of the UV-induced ER mutations arise at position 1951, consistent with misinsertions opposite the 3′ most T of a possible UV-induced pyrimidine dimer. Furthermore, comparison of the spectra of spontaneous and UV-induced mutations in the rev1-Δ, rev3-Δ, and rev7-Δ strains relative to the wildtype indicates that there is a significant difference only in the rev1-Δ strain. The spectrum of spontaneous mitochondrial point mutations in the rev1-Δ strain consists of 35% A → T transversions at position 1951, which is similar to the 33% observed in the wild-type strain. However following UV exposure, A → T transversions significantly increase to 76% in the rev1-Δ strain (p = 0.012) while there is no significant increase in the wild-type strain. These data indicate that in the mitochondrial compartment, the mechanism of UV recovery in the absence of Rev1p causes a shift in the mutational spectra that results primarily in A → T tranversions.

Table 4.

The Spectra of Erythromycin Resistant Mutations

| % with nucleotide substitutions (no.)

|

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1950

|

1951

|

1952

|

1949–1950

|

3993

|

|||||

| Strains | G→T | G→A | A→T | A→G | A→C | A→T | A→G | G ins | C→G |

| Spontaneous | |||||||||

| Wild-type | 5.6 (2) | 11.1 (4) | 33.3 (12) | 27.8 (10) | 2.7 (1) | 5.6 (2) | 5.6 (2) | 8.3 (3) | 0 |

| rev1-Δ | 0 | 5.0 (2) | 35.0 (14) | 32.5 (13) | 10.0 (4) | 0 | 10.0 (4) | 2.5 (1) | 5.0 (2) |

| rev3-Δ | 0 | 20.8 (5) | 37.5 (9) | 33.3 (8) | 0 | 4.2 (1) | 0 | 4.2 (1) | 0 |

| rev7-Δ | 0 | 0 | 28.6 (4) | 50.0 (7) | 7.1 (1) | 7.1 (1) | 7.1 (1) | 0 | 0 |

| UV-Induced | |||||||||

| Wild-type | 0 | 0 | 35.0 (7) | 55.0 (11) | 5.0 (1) | 0 | 5.0 (1) | 0 | 0 |

| rev1-Δ | 0 | 0 | 75.9 (22) | 13.8 (4) | 6.9 (2) | 3.4 (1) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| rev3-Δ | 0 | 0 | 53.8 (14) | 26.9 (7) | 7.7 (2) | 0 | 7.7 (2) | 3.8 (1) | 0 |

| rev7-Δ | 0 | 0 | 20.0 (1) | 60.0 (3) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 20.0 (1) | 0 |

A total of 194 independent erythromycin resistant colonies were sequenced. Only two mutations were found at position 3993. These were: rev1-Δ C → G (2).

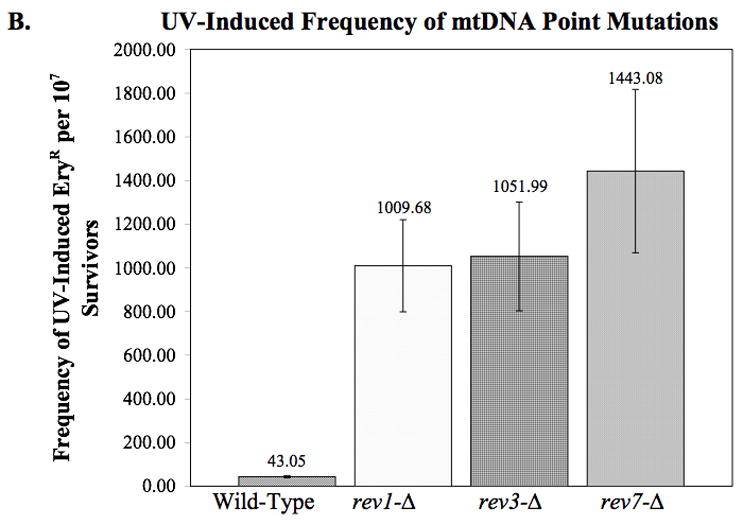

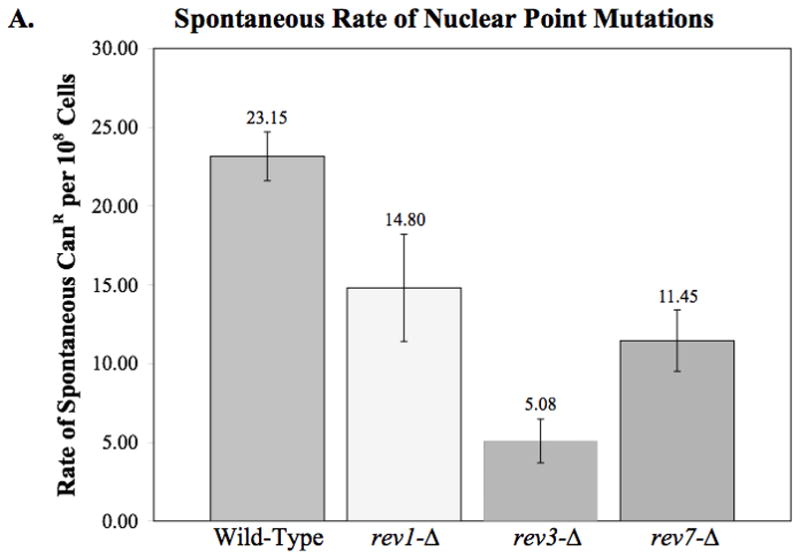

3.6. Verification of reduced nuclear mutagenesis in the rev1, rev3, and rev7 deletion strains

In order to ensure that the increased point mutation accumulation in the rev mutant strains is mitochondrial specific, we investigated the nuclear point mutation as measured by canavanine resistance (CanR). Canavanine is a lethal arginine analog that is taken up by the arginine permease, encoded by the CAN1 gene. Cells that have the ability to produce their own arginine and acquire a mutation in CAN1 gene can grow on medium lacking arginine and containing canavanine.

Using this drug, we can estimate spontaneous nuclear point mutation accumulation in the rev deletion strains. This assay indicates that while the rev1-Δ strain has a nuclear point mutation rate that is not significantly different from the wild-type strain, deletion of rev3 or rev7 results in a small, but significant decrease in spontaneous nuclear point mutations (p = 0.013 and 0.042, respectively) (Fig. 3A).

Fig. 3.

Nuclear point mutations as measured by canavanine resistance. (A) The spontaneous rate of canavanine resistance was determined by fluctuation analysis as described in Materials and Methods. The average rates from two or more independent experiments are plotted. Error bars indicated the SEM. Statistical analysis indicates that although rev1-Δ displays no significant difference from wildtype, rev3-Δ and rev7-Δ show a slight but significant decrease in nuclear point mutations (p = 0.013 and 0.042, respectively). (B) The frequency of nuclear point mutations per survivor after exposure to 50 J/m2 UV-C. The average frequency of 2–3 independent experiments is plotted. Error bars indicate the SEM. Statistical analysis reveals that the frequency of canavanine resistance in the rev1-Δ, rev3-Δ, and rev7-Δ strains is significantly lower than that of the wild-type strain (p = < 0.001 in all cases).

Additionally, we observed a significant decrease in UV-induced nuclear DNA point mutations in all three rev mutant strains as compared to the wild-type strain (Fig. 3B). Since the strains used for the these studies were derived from those used to measure mtDNA point mutations, this important control demonstrates that the strains we are examining behave as expected with respect to nuclear point mutations.

4. Discussion

The significance of mitochondrial mutagenesis is underscored by the accumulation of mtDNA mutations, rearrangements, and deletions associated with aging and aging-related disorders [30,31]. Evidence for UV-induced mtDNA point mutations was first published in 1979 [32], however, the protein components and pathways responsible for this mutagenesis was unknown. We now know that translesion polymerases are responsible for nuclear UV-induced mutagenesis, however, the mechanisms by which mitochondrial mutations are generated remain unknown.

Pol ζ and Rev1p are responsible for error-prone translesion synthesis in the nucleus [1]. Together these enzymes are responsible for both UV-induced and spontaneous mutagenesis [1]. Recently fusions of the N-termini of Rev1p and the proteins that comprise Pol ζ (Rev3p and Rev7p) with GFP suggested localization to the mitochondrial compartment of S. cerevisiae [15].

We have completed a comprehensive analysis of the different types of mitochondrial mutations associated with the deletion of rev1, rev3, and rev7. Consistent with a previous report, analysis of mitochondrial microsatellite instability in rev mutant strains demonstrates that Rev1p and Pol ζ are responsible for the majority of spontaneous and UV-induced mitochondrial frameshifts [15]. Furthermore, our data also indicates that these proteins play a role in the generation of UV-induced respiration loss. In contrast, we have determined that Pol ζ is responsible for preventing spontaneous mitochondrial erythromycin resistant mutations. In addition, although deleting the translesion polymerases Pol ζ and Rev1p results in a decrease of some types of mutations, their loss causes a dramatic increase in UV-induced mtDNA point mutations as measured by erythromycin resistance. Since there are limited tools available to measure mtDNA point mutations, we are only able to observe the spectra of mutations at one locus. However, the range of substitutions which give rise to ER in the 21S rRNA suggests that the observed increases are not limited to specific base substitutions. Regardless of its generality, this observation reveals the existence of an alternative mutagenic process. Furthermore, the spectra of mutations resulting in erythromycin resistance suggest that Rev1p is responsible for the spectrum produced in the wild-type strain. Although the increase in point mutations in the rev deficient strains may appear to be at odds with the decrease in respiration loss, we have previously observed that the rates of these types of mutations do not correlate well [20], suggesting that the mechanism by which they arise is different. Consistent with our previous results, we believe the non-respiring cells are unlikely to result primarily from an accumulation of point mutations.

Since converting DNA lesions into mutations is an active process, resulting from mechanisms of damage tolerance, our data indicate that there is another pathway that is more mutagenic than Rev1p and Pol ζ, which is responsible for generating mitochondrial mutations in their absence. Since these phenotypes are only observed for mtDNA and there is no apparent increase in nuclear mutations, we hypothesize that this alternative pathway is mitochondrial specific. The only other known polymerase in the mitochondrial compartment is Pol γ, which is responsible for replication of the mitochondrial genome. Therefore, we speculate that in the absence of TLS by Rev1p and Pol ζ, a modification of Pol γ may be responsible for creating some of these mutations in efforts to bypass lesions that block the replication fork. The Pol32 subunit of the yeast nuclear replicative polymerase, Pol δ, is involved in mutagenesis [33–35]. Therefore, we are interested in investigating whether Pol32 or another protein may associate with Pol γ to allow bypass of UV-induced lesions in the absence of Rev1p and Pol ζ.

The mechanism involved in UV-induced mtDNA damage tolerance in yeast and higher eukaryotes may be conserved considering the conservation of these polymerases among species. Recently therapeutic inhibition of Pol ζ has been proposed for the reduction of mutagenesis in cancer cells [36]. Our results suggest that such inhibition may adversely impact mtDNA.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Peter Gibbs and Dr. David C. Hinkle for critical reading of the manuscript. This work was sponsored by US National Institutes of Health grant GM63626 (E.A.S.) and US National Science Foundation grant MCB0543084 (E.A.S and L.K.).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Kunz BA, Straffon AFL, Vonarx EJ. DNA damage-induced mutation: tolerance via translesion synthesis. Mutation Research. 2000;451:169–185. doi: 10.1016/s0027-5107(00)00048-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Masutani C, Kusumoto R, Yamada A, Dohmae N, Yokoi M, Yuasa M, Araki M, Iwai S, Takio K, Hanaoka F. The XPV (xeroderma pigmentosum variant) gene encodes human DNA polymerase Eta. Nature. 1999;399:700–704. doi: 10.1038/21447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Johnson RE, Kondratick CM, Prakash S, Prakash L. hRAD30 Mutations in the Varient Form of Xeroderma Pigmentosum. Science. 1999;285:263–265. doi: 10.1126/science.285.5425.263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lemontt JF. Mutants of Yeast Defective in Mutation Induced by Ultraviolet Light. Genetics. 1971;68:21–33. doi: 10.1093/genetics/68.1.21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lawrence CW, Das G, Christensen RB. REV7, a new gene concerned with UV mutagenesis in Yeast. Molecular and General Genetics. 1985;200:80–85. doi: 10.1007/BF00383316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lawrence CW, O’Brien T, Bond J. UV-induced reversion of his4 frameshift mutations in rad6, rev1, and rev3 mutants of yeast. Molecular and General Genetics. 1984;195:487–490. doi: 10.1007/BF00341451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lawrence CW, Christensen RB. UV MUTAGENESIS IN RADIATION-SENSITIVE STRAINS OF YEAST. Genetics. 1976;82:207–232. doi: 10.1093/genetics/82.2.207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lawrence CW, Christensen RB. ULTRAVIOLET-INDUCED REVERSION OF cyc1 ALLELES IN RADIATION-SENSITIVE STRAINS OF YEAST. III. rev3 MUTANT STRAINS. Genetics. 1979;92:397–408. doi: 10.1093/genetics/92.2.397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Morrison A, Christensen RB, Alley J, Beck AK, Bernstine EG, Lemontt JF, Lawrence CW. REV3, a Saccharomyces cerevisiae Gene Whose Function Is Required for Induced Mutagenesis, Is Predicted To Encode a Nonessential DNA Polymerase. Journal of Bacteriology. 1989;171:5659–5667. doi: 10.1128/jb.171.10.5659-5667.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nelson JR, Lawrence CW, Hinkle DC. Thymine-Thymine Dimer Bypass by Yeast DNA Polymerase Zeta. Science. 1996;272:1646–1649. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5268.1646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lawrence CW. Cellular roles of DNA polymerase Zeta and Rev1 protein. DNA Repair. 2002;1:425–435. doi: 10.1016/s1568-7864(02)00038-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nelson JR, Lawrence CW, Hinkle DC. Deoxycytidyl transerase activity of yeast REV1 protein. Nature. 1996;382:729–731. doi: 10.1038/382729a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nelson JR, Gibbs PEM, Nowicka AM, Hinkle DC, Lawrence CW. Evidence for a second function for Saccharomyces cerevisiae Rev1p. Molecular Microbiology. 2000;37:549–554. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2000.01997.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Smolinska U. Mitochondrial mutagenesis in yeast: mutagenic specificity of EMS and the effects of RAD9 and REV3 gene products. Mutation Research. 1987;179:167–174. doi: 10.1016/0027-5107(87)90307-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhang H, Chatterjee A, Singh KK. Saccharomyces cerevisiae Polymerase Zeta Functions in Mitochondria. Genetics. 2006;172:2683–2688. doi: 10.1534/genetics.105.051029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sherman F. Methods in Enzymology. Academic Press, Inc; San Diego: 1991. Getting started with yeast; pp. 3–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Foury F, Vanderstraeten S. Yeast mitochondrial DNA mutators with deficient proofreading exonucleolytic activity. Embo J. 1992;11:2717–2726. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1992.tb05337.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Steele DF, Butler CA, Fox TD. Expression of a recoded nuclear gene inserted into yeast mitochondrial DNA is limited by mRNA-specific translational activation. PNAS. 1996;93:5253–5257. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.11.5253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.METHODS IN YEAST GENETICS. Cold Spring harbor Laboratory Press; Cold Spring Harbor: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mookerjee SA, Sia EA. Overlapping contributions of Msh1p and putative recombination proteins Cce1p, Din7p, and Mhr1p in large-scale recombination and genome sorting events in the mitochondrial genome of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mutation Research. 2006;595:91–106. doi: 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2005.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fox TD, Folley LS, Mulero JJ, McMullin TW, Thorsness PE, Hedin LO, Costanzo MC. Analysis and Manipulation of Yeast Mitochondrial Genes. In: Guthrie C, Fink GR, editors. Methods in Enzymology. Academic Press, Inc; San Diego: 1991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Phadnis N, Mehta R, Meednu N, Sia EA. Ntg1p, the base excision repair protein, generates mutagenic intermediates in yeast mitochondrial DNA. DNA Repair. 2006;5:829–839. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2006.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sia EA, Butler CA, Dominska M, Greenwell P, Fox TD, Petes TD. Analysis of microsatellite mutations in the mitochondrial DNA of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. PNAS. 2000;97:250–255. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.1.250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lea DE, Coulson CA. The distribution of the number of mutants in bacterial populations. Journal of Genetics. 1949;49:264–284. doi: 10.1007/BF02986080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lawrence CW, Maher VM. Mutagenesis in eukaryotes dependent on DNA polymerase zeta and Rev1p. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 2001;356:41–46. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2000.0746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sor F, Fukuhara H. Erythromycin and spiramycin resistance mutations of yeast mitochondria: nature of the rib2 locus in the large ribosomal RNA gene. Nucleic Acids Research. 1984;12:8313–8318. doi: 10.1093/nar/12.22.8313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cui Z, Mason TL. A single nucleotide substitution at the rib2 locus of the yeast mitochondrial gene for 21S rRNA confers resistance to erythromycin and cold-sensitive ribosome assembly. Current Genetics. 1989;16:273–279. doi: 10.1007/BF00422114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sor F, Fukuhara H. Identification of two erythromycin resistance mutations in the mitochondrial gene coding for the large ribosomal RNA in yeast. Nucleic Acids Research. 1982;10:6571–6577. doi: 10.1093/nar/10.21.6571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vanderstraeten S, Van den Brule S, Hu J, Foury F. The Role of 3′-5′ Exonucleolytic Proofreading and Mismatch Repair in Yeast Mitochondrial DNA Error Avoidance. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1998;273:23690–23697. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.37.23690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Orth M, Schapira AHV. Mitochondria and Degenerative Disorders. American Journal of Medical Genetics. 2001;106:27–36. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.1425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dahl HHM, Thorburn DR. Mitochondrial Diseases: Beyond the Magic Circle. American Journal of Medical Genetics. 2001;106:1–3. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.1427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ejchart A, Putrament A. Mitochondrial mutagenesis in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. I. Ultraviolet radiation. Mutation Research. 1979;60:173–180. doi: 10.1016/0027-5107(79)90181-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gibbs PEM, McDonald J, Woodgate R, Lawrence CW. The Relative Roles in Vivo of Saccharomyces cerevisiae Pol Eta, Pol Zeta, Rev1 Protein and Pol32 in the Bypass and Mutation Induction of an Abasic Site, T-T (6–4) Photoadduct and T–T cis-syn Cyclobutane Dimer. Genetics. 2005;169:575–582. doi: 10.1534/genetics.104.034611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Huang ME, de Calignon A, Nicolas A, Galibert F. POL32, a subunit of the Saccaromyces cerevisiae DNA polymerase delta, defines a link between DNA replication and the mutagenic bypass repair pathway. Current Genetics. 2000;38:178–187. doi: 10.1007/s002940000149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Huang ME, Rio AG, Galibert MD, Galibert F. Pol32, a Subunit of Saccharomyces cerevisiae DNA Polymerase δ, Suppresses Genomic Deletions and Is Involved in the Mutagenic Bypass Pathway. Genetics. 2002;160:1409–1422. doi: 10.1093/genetics/160.4.1409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lin X, Trang J, Okuda T, Howell SB. DNA polymerase zeta accounts for the reduced cytotoxicity and enhanced mutagenicity of cisplatin in human colon carcinoma cells that have lost DNA mismatch repair. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12:563–568. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-1380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bonnefoy N, Fox TD. In vivo analysis of mutated initiation codons in the mitochondrial COX2 gene of Saccharomyces cerevisiae fused to the reporter gene ARG8m reveals lack of downstream reinitiation. Molecular Genetics and Genomics. 2000;262:1036–1046. doi: 10.1007/pl00008646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Phadnis N, Sia EA. Role of the Putative Structural Protein Sed1p in Mitochondrial Genome Maintenance. Journal of Molecular Biology. 2004;342:1115–1129. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.07.096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]