Abstract

In three cross-over experiments, we examined the effect on energy intake of changing the size of the plate used at a meal. On separate days, adults were served the same lunch menu but were given a different-sized plate. In the first study, 45 participants used each of three plate sizes (17, 22, or 26 cm) and served the main course from a large dish. In the second study, 30 participants received an equal amount of food presented on each of the two larger plates. In the third study, 44 participants used each of the three plates and selected from a buffet of five foods matched for energy density. Results showed that plate size had no significant effect on energy intake. The mean differences in intake using the smallest and largest plates in the three studies were 21±13 g, 11±13 g, and 4±18 g, respectively, equivalent to < 142 kJ (34 kcal) and not significantly different from zero. Participants in the third study made significantly more trips to the buffet when they were given the smallest plate. These findings show that using a smaller plate did not lead to a reduction in food intake at meals eaten in the laboratory.

Keywords: eating behavior, plate size, portion size, energy intake, food intake, adults, weight status

Introduction

Observational data indicate that an increase in the average size of plates used at meals has paralleled the rise in obesity rates in the United States (Young & Nestle, 2003). The diameter of a typical dinner plate has increased from 25 cm (10 in) in the early 1980s to 30 cm (12 in) in the early 2000s (Klara, 2004), equivalent to an increase in surface area of 44%. A number of experimental studies have shown that an increase in the portion size of foods is associated with increased energy intake (Ledikwe, Ello-Martin, & Rolls, 2005; Rolls, Morris, & Roe, 2002). Several organizations currently recommend the use of smaller plates as a strategy for reducing the size of the portions that are served, with the goal of decreasing energy intake (National Institutes of Health, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, 1999; U.S. Department of Agriculture, Center for Nutrition Policy and Promotion, 2002). There is, however, little evidence demonstrating the efficacy of this recommendation in reducing energy intake. Before a relationship between larger plate size and the incidence of obesity can be determined, it is important to examine whether plate size has an effect on energy intake.

Although there is little research relating plate size to energy intake, several studies suggest that the size of a plate or container can influence the estimation of food portion size. For example, it has been found to be particularly difficult to judge the portion size of amorphous foods served in large containers (Yuhas, Bolland, & Bolland, 1989). Wansink (2004) suggests that a size-contrast illusion leads individuals to perceive that a given portion is smaller when served on a large plate. In one study, (Wansink & Cheney, 2005) it was found that the size of the bowl in which snacks were presented at a party affected the amount that participants served themselves. In another study conducted at a social occasion (Wansink, van Ittersum, & Painter, 2006), it was reported that people who were randomly given 1 L (34 fl. oz.) bowls served themselves 31% more ice cream than those given 500 mL (17 fl. oz.) bowls, and those given serving spoons that were 50% larger served themselves 14% more. While intake was not measured in this study, the researchers observed that all but three participants consumed all of their ice cream.

While previous research suggests that the size of plate or bowl that food is eaten from could have an effect on the amount of food that is served, an effect of plate size on energy intake has not been clearly shown. Examining this relationship requires a controlled environment in which plate size is the only factor that is varied and food intake is measured precisely. We conducted a series of three such studies to test the effect on energy intake of changing the size of the plate used at a meal. The studies differed in whether the foods were served by the participants or by the researchers, in the number of foods that were offered, and in the effort involved in obtaining the food.

General Methods

Experimental Design

All three experiments that were conducted to examine the effect of plate size on energy intake utilized a cross-over design with repeated measures within subjects; thus, participants served as their own controls. Subjects came to the laboratory to eat lunch once a week for either two or three weeks, depending on the study. Across the weeks the same foods were served at each meal; only the size of the plate was changed. The order in which participants were given the different plate sizes was randomly assigned. In Studies 1 and 2, a single food was provided to participants. In Study 3, participants selected from personal buffets of five different foods that were matched in energy density.

Participants

Different participants were enrolled in each of the three experiments. Adults aged 20 to 45 years were recruited from the university community by flyers, newspaper advertisements, and announcements sent to e-mail lists. Prospective participants were interviewed by telephone to determine whether they met the following criteria for inclusion in the studies: were not dieting to lose or gain weight, were not in athletic training, were not pregnant or breastfeeding, were not taking medications known to affect appetite or food intake, had no food allergies or restrictions, regularly ate 3 meals daily, and did not smoke. Potential participants came to the laboratory to have their height and weight measured and to complete the following questionnaires: the Eating Inventory (Stunkard & Messick, 1985), which evaluates dietary restraint, disinhibition, and tendency towards hunger; the short form of the Eating Attitudes Test (Garner, Olsted, Bohr, & Garfinkel, 1982), which assesses indicators of disordered eating; and the Zung Self-rating Scale (Zung, 1986), which evaluates symptoms of depression.

Individuals were not included in the study if they had a body mass index < 18 or > 40 kg/m2, if they scored > 40 on the Zung Self-rating Scale or ≥ 20 on the Eating Attitudes Test, or if they reported disliking the main course to be served in Studies 1 and 2 or more than one of the five foods to be served in Study 3. All procedures were approved by the Office for Research Protections of The Pennsylvania State University. Participants provided written consent and were paid for their participation. In the consent form, participants were informed that a video camera would be used in experimental sessions to record information for data analysis.

Experimental Plates

At each meal, participants were provided with one of three sizes of plain white glass plates of the same pattern (Corelle®, World Kitchen LLC, Greencastle, PA, USA). The plates had diameters of 17, 22, and 26 cm (6.75, 8.50, and 10.25 in) with surface areas of 231, 366, and 532 cm2 (46, 72, and 105 in2), respectively (Figure 1). Thus, compared to the medium plate, the small plate had 37% less surface area and the large plate had 45% more surface area. The large plate was more than double the size of the small plate, with 130% greater surface area.

Figure 1.

Three sizes of plates used in the series of studies of the effect of plate size on energy intake at a meal. Plate A was 17 cm (6.75 in) in diameter, Plate B was 22 cm (8.50 in) in diameter, and Plate C was 26 cm (10.25 in) in diameter. The three plates are shown side by side for comparison, but study participants never saw them displayed together.

Daily Procedures and Data Collection

Participants were instructed to keep their food and activity level similar and to refrain from consuming alcohol on the day before each study day. In order to encourage compliance with this protocol, participants completed a brief record of food intake and physical activity. Experimental meals were scheduled at the same time of day for a given individual, and a standard breakfast was provided on each study day. All meals were eaten in individual cubicles. Participants were instructed not to consume any foods or beverages other than water between breakfast and lunch, and not to consume water for one hour before lunch. Before lunch, participants completed a short questionnaire that evaluated whether they were feeling well and whether they had taken any medication or consumed any food or beverages outside the laboratory since breakfast.

Immediately before and after each experimental meal, participants rated their hunger, fullness, and prospective consumption (how much they thought they could eat) using visual analog scales (Hetherington & Rolls, 1987). For example, participants answered the question “How hungry are you right now?” by marking a 100-mm line that was anchored on the left by “Not at all hungry” and on the right by “Extremely hungry”. In Studies 1 and 2, after observing the food and taking one bite, participants also used visual analog scales to rate the main course for appearance, taste, and amount of fat, as well as the size compared to their usual portion. In Study 3, the characteristics of the foods were not rated because participants would not necessarily eat all five of the foods.

All foods were weighed before and after meals to determine the amount consumed to the nearest 0.1 g. Food weights were converted to nutrient intakes using food composition data from food manufacturers and a standard reference (U.S. Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Research Service, 2006). At the end of each study, participants completed a discharge questionnaire, which asked them to report any differences they noticed between the meals and their conjecture about the purpose of the experiment.

Statistical Analyses

For Studies 1 and 2, a power analysis was conducted using data from a previous cross-over study in which a similar food with the same energy density was served to a comparable population. We defined a clinically significant difference in mean food intake between experimental conditions to be 50 g (335 kJ; 80 kcal), which was approximately 12% of the expected mean intake. It was estimated that a sample of 30 subjects would allow the detection of a difference of this magnitude with a power of 80% at a significance level of 0.05. For Study 3, we assumed there would be greater variability in intake due to the increased variety of foods available. For this study, it was estimated that a sample of 40 subjects would allow the detection of a difference of the given magnitude with a power of 80% at a significance level of 0.05.

Data were analyzed using a mixed linear model with repeated measures (SAS 9.1, SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA). The fixed factors in the model were plate size and subject sex; subjects were treated as a random effect. The main outcomes analyzed were food intake (g), total lunch energy intake, ratings of hunger and satiety, and ratings of food characteristics. Participants who consumed ≥ 95% of any of the foods provided at a meal were identified; outcomes were analyzed both with and without these participants in order to investigate their influence on the results. Analysis of covariance was used to examine the influence of participant characteristics on the relationship between plate size and intake. Regression analysis was used to identify which of the experimental and participant variables significantly predicted energy intake at lunch. Differences between characteristics of men and women were examined using t-tests. Results were considered significant at p < 0.05.

Study 1: Effect of plate size on energy intake when participants served themselves a main course

In a previous study, when participants served a main course (macaroni and cheese) onto a standard-sized plate from a serving dish containing different amounts (500, 625, 750, or 1000 g), they consumed 30% more energy when offered the largest portion than when offered the smallest portion (Rolls et al., 2002). This suggests that the availability of bigger portions affected the amount of food thought to be appropriate to eat. It has also been suggested that the size of the plate or bowl from which a person eats provides cues about appropriate amounts to consume (Wansink et al., 2006). Study 1 tested the hypothesis that when participants serve their food onto a larger plate, they will increase their intake of that food.

Methods

In Study 1, participants ate lunch in the laboratory once a week for three weeks. Each week participants were seated in cubicles and given one of three plates (17, 22, or 26 cm in diameter) and a serving dish containing 800 g (5.4 MJ; 1280 kcal) of a main course of macaroni and cheese (Table 1). Participants were instructed to serve the food from the dish onto the plate as often as they wanted, and to eat as much as they wanted from the plate. The amount of food that was provided was chosen to be in excess of participant intakes based on previous experiments. The beverage served at the experimental lunch was water (1 L). In addition to the main course and beverage, participants were served 35 g of carrots and 17 g of chocolate, which were required to be fully consumed and provided a total of 464 kJ (111 kcal).

Table 1.

Nutrient composition of foods served at experimental meals in the three studies

| Food | Study number | Energy density (kJ/g) | Energy density (kcal/g) | % Energy as protein | % Energy as fat | % Energy as carbohydrate |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Macaroni and cheesea | 1, 2, 3 | 6.69 | 1.60 | 16.1 | 19.1 | 64.8 |

| Chicken and noodlesb | 3 | 7.11 | 1.70 | 18.0 | 45.9 | 36.0 |

| Green bean casserolec | 3 | 6.86 | 1.64 | 9.0 | 70.3 | 20.7 |

| Broccoli saladc | 3 | 7.15 | 1.71 | 6.3 | 68.5 | 25.2 |

| Sweet potato casserolec | 3 | 6.69 | 1.60 | 3.4 | 20.9 | 75.6 |

Prepared from package, light version (Kraft Foods, Inc., Glenview, IL, USA)

Prepared from frozen (Stouffer’s brand, Nestlé USA, Inc., Solon, OH, USA)

Recipe available from the authors upon request

Results

Forty-seven participants were enrolled, but two participants withdrew from the study after attending one meal. The characteristics of the 45 participants who completed the experiment are shown in Table 2. Nine (20%) of the participants were overweight (body mass index ≥ 25 kg/m2).

Table 2.

Characteristics of participants in the three experiments (mean ± SEM)

| Study 1 | Study 2 | Study 3 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | Women(n = 22) | Men(n = 23) | Women(n = 15) | Men(n = 15) | Women(n = 22) | Men(n = 22) |

| Age (y) | 22.5 ± 1.0 | 21.7 ± 0.4 | 28.4 ± 2.1 | 25.9 ± 1.5 | 22.1 ± 0.3 | 23.2 ± 0.7 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 22.0 ± 0.6 | 23.5 ± 0.5 | 24.4 ± 1.1 | 23.2 ± 0.6 | 22.2 ± 0.3 | 23.0 ± 0.6 |

| Estimated energy expenditure(MJ/d [kcal/d]) | 9.12 ± 0.14 [2180 ± 34] | 12.13 ± 0.15* [2898 ± 37*] | 9.38 ± 0.17 [2243 ± 41] | 11.58 ± 0.18* [2767 ± 43*] | 8.97 ± 0.10 [2143 ± 24] | 11.71 ± 0.16* [2799 ± 39*] |

| Dietary restraint scorea | 7.0 ± 0.7 | 4.5 ± 0.8* | 10.3 ± 1.2 | 7.0 ± 1.1 | 7.0 ± 0.7 | 6.0 ± 0.9 |

| Disinhibition scorea | 5.0 ± 0.8 | 3.7 ± 0.5 | 5.7 ± 0.9 | 4.5 ± 0.6 | 5.0 ± 0.6 | 4.3 ± 0.4 |

| Tendency to hunger scorea | 5.7 ± 0.6 | 5.2 ± 0.6 | 5.4 ± 0.8 | 4.8 ± 0.6 | 4.5 ± 0.6 | 5.9 ± 0.6 |

Within each study, means between sexes are significantly different by t-test (p < 0.0001)

Scores from the Eating Inventory (Stunkard & Messick, 1985)

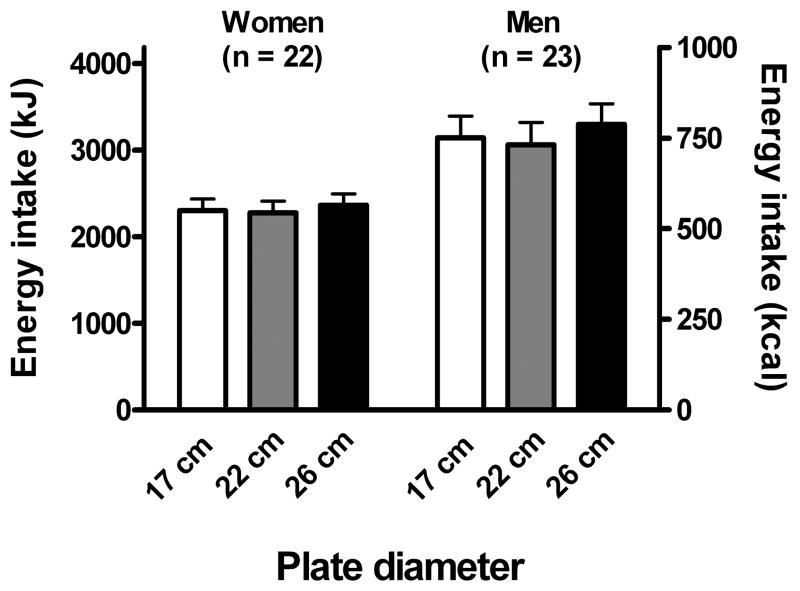

Analysis showed that the size of the plate had no significant effect on energy intake at the meal (p = 0.29; Figure 2). Although women consumed less energy than men, the relationship between plate size and intake did not differ for women and men. Mean intake of the main course for both sexes was 337 ± 23 g when the small plate was used, 330 ± 23 g when the medium plate was used, and 357 ± 23 g when the large plate was used. The mean difference in food intake between the conditions with the small and large plates was 20.7 ± 13.3 g (95% confidence limits: −7 to 46 g), equivalent to 6% of mean intake of the main course. Intake of water as a beverage did not vary across experimental conditions (p = 0.10; mean across all conditions 402 ± 17 g).

Figure 2.

Meal energy intake (mean ± SE) in women and men provided with the same food on different days but one of three different plate sizes (Study 1). The main course was provided in a serving dish and participants served it onto the plate as often as they desired. There was no significant effect of plate size on meal energy intake.

Intakes were examined after excluding data from 3 men who consumed ≥ 95% of the main course provided at one or more meals. After excluding this data, plate size still had no significant effect on intake. Analysis of covariance showed that the relationship between plate size and intake was not influenced by any of the measured participant characteristics (age, height, weight, body mass index, estimated energy expenditure, or scores for depression, eating attitudes, dietary restraint, disinhibition, or tendency towards hunger).

In the regression analysis, neither plate diameter nor plate surface area significantly predicted lunch energy intake; the only significant predictors of energy intake were subject characteristics. These predictors were estimated daily energy expenditure and the score for tendency toward hunger; together these factors accounted for 26% of the variability in energy intake.

There were no significant differences in ratings of hunger and satiety across conditions of plate size either before or after lunch. There were also no differences across conditions in participant ratings of the amount of food compared to their usual portion. There were differences in this rating, however, between women and men. Women rated the amount of food as being larger compared to their usual portion than did men (mean 86 ± 2 for women and 75 ± 2 for men; p = .025). Additionally, there were no significant differences across conditions in participant ratings of the appearance, taste, or fat content of the main course.

At discharge, 11 participants (24%) reported that the plate size changed across the meals. Only one participant correctly determined that the purpose of the experiment was to test the influence of plate size on intake. Neither awareness of the change in plate size nor knowledge of the study purpose had a significant influence on lunch energy intake.

Discussion

Even with large differences in the size of the available plate (up to a 130% increase in surface area), participants did not eat significantly different amounts of the main course. Although 24% of the participants noticed the change in plate size, this awareness did not affect the results. Thus, the participants did not appear to use the size of the plate as a guide to the appropriate amount to eat. It is possible that instead they used cues related to the amount of food present or remaining in the serving dish to guide intake. It is also feasible that the act of serving the food from the dish to the plate focused attention on the amount that participants were taking, and thus provided cues that could be used to guide consumption.

Study 2: Effect on energy intake of different-sized plates containing a fixed amount of a main course

In the second study, cues related to the act of serving food from a dish were eliminated by presenting a fixed amount of food on each of two different-sized plates. It has been suggested that the size of items in the food environment, such as plates and spoons, provides a visual bias that affects the perception of appropriate amounts to eat (Wansink et al., 2006). Study 2 tested the hypotheses that the size of the plate and eating utensil influence both the perception of the amount of food on the plate and intake of that food.

Methods

Participants ate lunch in the laboratory once a week for two weeks. Each week, participants were seated in cubicles and provided with 700 g (4.7 MJ; 1120 kcal) of macaroni and cheese (Table 1) that had been placed on a plate by the researchers. Because the entire amount of food was presented on the plate, only the two larger plates (22 and 26 cm) were used, and the amount of food served was less than the portion in Study 1 so that it would fit on the plates. In addition to the difference in plate size, the size of the eating utensil was also varied; a standard spoon was provided with the medium plate, and a soup spoon (50% larger) was provided with the large plate. Participants were instructed to consume as much of the food as they wanted using the provided eating utensil. Participants were also served 1 L of water, which they could consume freely, and 35 g of carrots and 17 g of chocolate, which they were required to consume and provided 464 kJ (111 kcal). At discharge, participants were shown examples of both plates of food at the same time, and asked to state which had a larger amount of food.

Results

Thirty participants began and completed Study 2 (Table 2); six participants (20%) were overweight. Analysis showed that the size of the plate had no significant effect on energy intake at the meal (p = 0.41; Figure 3). Women consumed less energy than men, but the effect of plate size on intake did not differ for women and men. Mean intake of the main course for both sexes was 369 ± 28 g for the medium plate and 380 ± 29 g for the large plate. The mean difference between the conditions was 11.0 ± 13.1 g (95% confidence limits: −16 to 38 g), equivalent to 3% of mean intake of the main course. After excluding data from 3 men who consumed ≥ 95% of the main course provided at either meal, plate size still had no significant effect on intake. Water intake did not vary between experimental conditions (p = 0.66; mean for both conditions 412 ± 23 g).

Figure 3.

Meal energy intake (mean ± SE) in women and men provided with the same food on different days but one of two different plate sizes and a proportionally-sized eating utensil (Study 2). The entire amount of the main course was presented on the plate. There was no significant effect of plate size on meal energy intake.

Analysis of covariance showed that the relationship between plate size and intake was not influenced by any of the measured participant characteristics (age, height, weight, body mass index, estimated energy expenditure, or scores for depression, eating attitudes, dietary restraint, disinhibition, or tendency towards hunger). In the regression analysis, neither plate diameter nor plate surface area significantly predicted lunch energy intake. The only significant predictors of energy intake were estimated daily energy expenditure, the score for tendency toward hunger, and the inverse of the scores for disinhibition and eating attitudes. Together these factors accounted for 41% of the variability in energy intake.

There were no significant differences in ratings of hunger and satiety between conditions of plate size either before or after lunch. There were also no differences between conditions in participant ratings of appropriateness of the portion size. There were, however, differences in this rating between women and men. Women rated the portion size as larger in comparison to their usual portion than did men (mean 85 ± 2 versus 73 ± 2; p = .006). There were no differences between conditions in participant ratings of the appearance, taste, or fat content of the main course.

At discharge, 5 participants (17%) reported that the plate size changed between the meals; 2 of these participants also noted the change in spoon size. None of the participants correctly determined the purpose of the experiment. An awareness of the change in plate size did not have a significant effect on lunch energy intake. When participants were asked to compare the amount of food on the two plates presented together, 24 participants (80%) stated correctly that the amount on the two plates was the same, 3 (10%) stated that the amount on the medium plate was greater, and 3 (10%) stated that the amount on the large plate was greater.

Discussion

In a side-by-side comparison, a 45% increase in plate surface area did not affect perception of the amount of food on the plate in most of the participants. It is possible that using plates with a greater difference in size, or dishes that also varied in height (such as bowls) might lead to a difference in perceived quantities (Wansink, 2004). However, the plates used in this study are typical of those a consumer might encounter. Since there was little difference in the perception of the amount of food on the plate, it is not surprising that plate size, even when paired with variation in the size of the spoon used for consumption, did not significantly affect food intake. This result contrasts with the robust effect of portion size on intake seen in a previous study, in which participants were served different portions of macaroni and cheese on a standard-sized plate (Rolls et al., 2002).

Study 3: Effect of plate size on energy intake when participants served themselves from a buffet

In Studies 1 and 2, the availability of a single food may have made it relatively easy for participants to ignore plate size and to eat a consistent amount of food. Using a smaller plate may more effectively limit intake in a situation such as a buffet, where a variety of different foods are available in large quantities and more effort is required to obtain food. Study 3 tested the hypothesis that when participants serve themselves from a buffet, plate size will provide a cue about an appropriate amount of food to consume, so that using a smaller plate will lead to reduced intake.

Methods

Participants ate lunch in the laboratory once a week for three weeks. Each week, participants were provided with one of the three plates (17, 22, or 26 cm) and were shown a personal buffet that was located 6 m away from the dining cubicle. The buffet comprised large quantities of five foods (chicken and noodles, macaroni and cheese, green bean casserole, broccoli salad, and sweet potato casserole) that were kept hot in a steam table unit (except for the salad). The five foods differed in macronutrient composition (Table 1) and sensory properties but were matched in energy density (6.9 kJ/g; 1.65 kcal/g) so that energy intake would be independent of the type of food selected. Participants were instructed to walk to their personal buffet, serve their chosen foods onto the plate, and return to their dining cubicle to eat. Participants could return to their buffet as often as they wanted, and eat as much as they wanted. The beverage served with the meal was water (1 L). The number of trips that participants made to the buffet was observed using an unobtrusive video monitoring system.

At the end of the study, participants used a seven-point scale to rate eight factors for their effect on the amount of food eaten from the buffet (rating of 1 = “none at all” and 7 = “very much”). The eight factors were variety of food, taste of food, effort in getting food, size of plate, recent physical activity, appearance of food, extent of hunger, and temperature of food.

Results

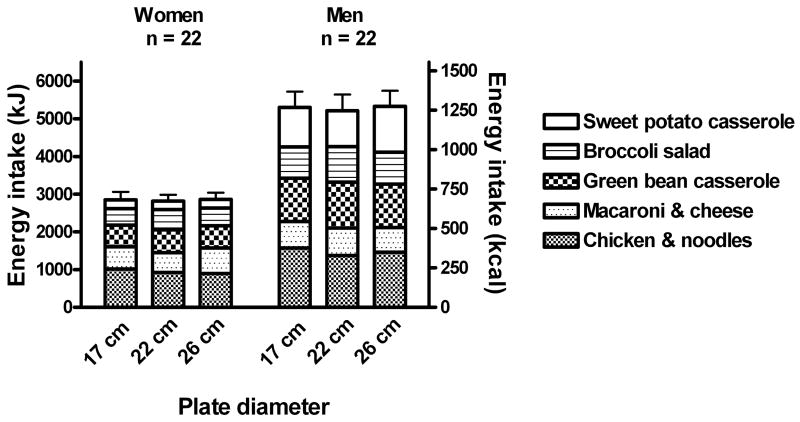

Forty-four participants began and completed Study 3 (Table 2); six of the participants (14%) were overweight. Analysis showed that plate size had no significant effect on meal energy intake (p = 0.61; Figure 4). Although women consumed less energy than men, the effect of plate size on intake from the buffet did not differ for women and men. Mean food intake for both sexes was 590 ± 43 g when the small plate was used, 581 ± 42 g when the medium plate was used, and 594 ± 42 g when the large plate was used. The mean difference in food intake between the conditions with the small and large plates was 4.1 ± 18.0 g (95% confidence limits −32 to 40 g), equivalent to 1% of mean meal intake. Water intake did not vary across experimental conditions (p = 0.43; mean across conditions 469 ± 17 g).

Figure 4.

Meal energy intake (mean ± SE) in women and men provided with the same foods on different days but one of three different plate sizes (Study 3). Five different foods were provided at a personal buffet located 6 m from the dining cubicle. Participants walked to the buffet and served their selections onto the plate as often as they desired. There was no significant effect of plate size on meal energy intake.

There was a significant effect of plate size on the number of trips made to the buffets (p < 0.0001). When the smallest plate was provided, participants made significantly more trips (mean 2.7 ± 0.1) than when either of the two larger plates was provided (mean 2.1 ± 0.1 for the 22 cm plate and 2.0 ± 0.1 for the 26 cm plate). The duration of the meal (including time traveling to the buffet) did not differ by plate size, but did differ by participant sex (mean 13.6 ± 0.5 min for women and 17.5 ± 0.5 min for men; p = 0.01).

Analysis of covariance showed that the relationship between plate size and intake was not influenced by any of the measured participant characteristics (age, height, weight, body mass index, estimated energy expenditure, or scores for depression, eating attitudes, dietary restraint, disinhibition, or tendency towards hunger). In the regression analysis, neither plate diameter nor plate surface area significantly predicted lunch energy intake. The predictors of energy intake were estimated daily energy expenditure and the inverse of the Zung score for depression; together these factors accounted for 52% of the variability in energy intake. There were no significant differences in ratings of hunger and satiety across conditions of plate size either before or after lunch. Ratings of food characteristics were not assessed in Study 3.

At discharge, 38 (86%) of the participants reported noticing a difference in plate size, and 24 of these participants (55%) guessed the purpose of the study. Neither awareness of the change in plate size nor knowledge of the study purpose had a significant influence on lunch energy intake. When participants were asked to rate the influence of eight factors on the amount of food eaten from the buffet, the factors of hunger and food taste were rated significantly higher than the others (p < 0.0001; mean ratings 5.8 ± 0.2 and 5.5 ± 0.2, respectively). The factors of food variety, food appearance, food temperature, plate size, and recent physical activity received intermediate ratings (means ranged from 2.8 to 4.4), and the factor of effort in getting the food received a lower rating than the others (p < 0.004; mean rating 1.9 ± 0.2).

Discussion

Both women and men ate a remarkably consistent amount of food when using different-sized plates to select from the variety of foods available at the buffet. They adjusted for the limited amount of food that could be put on the smaller plate by making more trips to the buffet. Participants did not perceive the effort of walking 6 m from their seats to obtain the food as having an important influence on the amount they ate. In contrast to the previous two experiments, a majority of participants in this study noticed the difference in plate size. It is likely that awareness of the change in plate size was heightened by the greater number of trips that were made to the buffet when the smaller plate was used. This awareness, however, did not influence the results of the study. It is possible that plate size may affect intake at a buffet in a restaurant setting, where customers may have to wait in line to refill their plates or there may be social pressure against returning for more food.

Participants rated hunger and the taste of the available foods as having the most important influence on their intake. The energy density of foods can affect the taste or palatability; foods that are higher in energy density may be more palatable than low-energy-dense foods (Drewnowski, 1998). In this study, however, the five foods at the buffet were similar in energy density. When palatability and energy density both vary, plate size may affect the proportions of foods eaten from a buffet, and this could affect energy intake. Future studies should explore how variations in plate size affect intake when both the taste and the energy density of foods vary.

General Discussion

In three separate experiments, no significant relationship was found between plate size and the amount of food consumed at a meal. Regardless of whether participants served themselves one or more foods on different-sized plates, or whether a food was presented already served on different-sized plates, they ate a consistent amount of food. The difference in mean intake between the extreme conditions of plate size ranged from a non-significant 1% to 6% of total meal intake, although the surface area of the plates varied as much as two-fold. While the influence of plate size has not been studied previously under controlled laboratory conditions, studies have found that bowl size affected the amount people served themselves in social situations (Wansink et al., 2006). The authors suggest that decisions about the amount of food to serve oneself are driven in part by environmental or contextual cues such as bowl size. These cues can affect perception both of the size of the portion and its appropriateness for consumption.

Since environmental food cues can be modified, it is important to understand which of these have the most robust effects on intake. One such cue is the portion size of foods. A number of studies have shown a significant effect of portion size, such that the bigger the available portion, the greater the intake (Ledikwe et al., 2005). The effect is seen both in the laboratory (Rolls, Roe, & Meengs, in press; Rolls, Roe, & Meengs, 2006, Levitsky & Youn, 2004) and in a restaurant setting (Diliberti, Bordi, Conklin, Roe, & Rolls, 2004), and when consumers serve themselves as well as when foods are served to them (Rolls et al., 2002). The portion size of many foods served inside and outside the home has increased in the past 30 years (Young & Nestle, 2003). While the reasons for this increase are complex and relate in part to providing perceived value to customers, it is possible that the availability of larger plates, cups, and baking pans has played a role (Young & Nestle, 2003). In a recent survey of 300 practicing chefs in the United States, 77% reported that plate size had an influence on the size of the portions served in their restaurants (Condrasky, Ledikwe, Flood, & Rolls, in press). The effect of plate size on the actual amounts that chefs serve, however, is not known. If the use of larger plates in restaurants or homes leads to increased portion sizes, then a recommendation to use smaller plates is warranted, since there are clear findings that portion size affects energy intake.

It is not clear that plate size in itself, apart from a change in portion size, affects energy intake. The present results indicate that plate size did not affect food intake in a controlled laboratory setting; instead, participants ate a remarkably consistent amount of food from meal to meal despite the change in plate size. A number of other studies have shown that when the same amount of a food is served on different occasions, the weight of food consumed is consistent (Rolls, 2000). It is likely that through experience people learn the amount of particular foods to consume in order to satisfy hunger. However, this tendency to eat a consistent weight of food can be influenced by some food-related cues in the environment. In particular, when larger portions are served, a greater weight of food is consumed, and this effect has been shown to persist for up to 11 days (Rolls et al., in press).

Any effect that plate size might have on consumption appears to be less robust than that of portion size. Contrary to the suggestion that plate size may drive ingestion, the subjects in Study 3 rated hunger and food taste as the primary influences on their intake. Noticing a difference in plate size or guessing the purpose of the study did not affect the results of the experiments. Even though plate size varied by as much as twofold, many subjects did not notice this difference, and ratings of the appropriateness of the amount of food on the plates did not vary with plate size. Furthermore, in Study 2, when participants were asked to compare the portions on two different-sized plates, 80% correctly stated that the amounts were the same. Thus, in these studies, plate size did not influence perception of the appropriate amount to eat or of the portion served.

In these laboratory-based studies, participants ate alone in a cubicle where there were few distractions. In more natural eating situations such as a family dinner or a party, social interactions and various distractions are likely to take attention away from food cues that might guide consumption. The study showing that bowl size affected the amount people served themselves was conducted at a social event (Wansink et al., 2006). Other studies show that people tend to overeat when they are distracted or eating with friends (Brunstrom & Mitchell, 2006; Herman & Polivy, 2005; Hetherington, Anderson, Norton, & Newson, 2006). In situations where people are not paying attention to feelings of hunger or amounts they are eating, cues such as plate or bowl size that suggest an appropriate portion may play a more important role in determining intake.

It is reasonable to hypothesize that individual characteristics such as dietary restraint or disinhibition might affect the response to environmental cues related to food consumption. In this series of within-subject experiments, we found that none of the measured subject characteristics (including dietary restraint, disinhibition, and body size) influenced the effect of plate size on intake. In addition, men and women showed a similar response to plate size. In all three studies, estimated energy expenditure was an important predictor of intake, but plate size was not. Thus, in these studies there was no evidence that responsiveness to plate size was influenced by individual characteristics, although with a larger number of subjects with a wide range of characteristics, these might be found to have an influence.

Although plate size did not significantly influence intake in these controlled studies, it is possible that with other foods, or in other situations, an effect might be seen. In the study that found an effect of bowl size on the amount of food participants served themselves, the food offered (ice cream) was highly palatable and high in energy density. Plate size may have more influence on intake of such foods than on the main courses and vegetable dishes used in the present studies. It is also possible that plate size is more likely to influence consumption when it is purposely used as a guide to appropriate portions as part of a behavioral weight management program; future studies should test the efficacy of this approach. Current data indicate that, whereas portion size has robust effects on energy intake, the size of the plate from which a meal is consumed is not a clear determinant of intake. Until further data are available, strategies to reduce energy intake should emphasize consumption of appropriate portions rather than the use of smaller plates.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by grants from the National Institute of Diabetes & Digestive and Kidney Diseases of the National Institutes of Health (R01-DK039177 and R37-DK059853).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Brunstrom JM, Mitchell GL. Effects of distraction on the development of satiety. British Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2006;96:761–769. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Condrasky M, Ledikwe JH, Flood J, Rolls BJ. Chefs' opinions of restaurant portion sizes. Obesity. doi: 10.1038/oby.2007.248. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diliberti N, Bordi P, Conklin MT, Roe LS, Rolls BJ. Increased portion size leads to increased energy intake in a restaurant meal. Obesity Research. 2004;12:562–568. doi: 10.1038/oby.2004.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drewnowski A. Energy density, palatability, and satiety: implications for weight control. Nutrition Reviews. 1998;56:347–353. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-4887.1998.tb01677.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garner DM, Olsted MP, Bohr Y, Garfinkel PE. The Eating Attitudes Test: psychometric features and clinical correlates. Psychological Medicine. 1982;12:871–878. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700049163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herman CP, Polivy J. Normative influences on food intake. Physiology and Behavior. 2005;86:762–772. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2005.08.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hetherington MM, Anderson AS, Norton GNM, Newson L. Situational effects on meal intake: a comparison of eating alone and eating with others. Physiology & Behavior. 2006;88:498–505. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2006.04.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hetherington MM, Rolls BJ. Methods of investigating human eating behavior. In: Toates F, Rowland N, editors. Feeding and Drinking. Amsterdam: Elsevier Science Publishers B V; 1987. pp. 77–109. [Google Scholar]

- Klara R. Table the issue. Restaurant Business. 2004;103(18):14–15. [Google Scholar]

- Ledikwe JH, Ello-Martin JA, Rolls BJ. Portion sizes and the obesity epidemic. Journal of Nutrition. 2005;135:905–909. doi: 10.1093/jn/135.4.905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levitsky DA, Youn T. The more food young adults are served, the more they overeat. Journal of Nutrition. 2004;134:2546–2549. doi: 10.1093/jn/134.10.2546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Institutes of Health, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Clinical Guidelines on the Identification, Evaluation, and Treatment of Overweight and Obesity in Adults - Highlights for Patients. Bethesda, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 1999. Publication #55–909. [Google Scholar]

- Rolls BJ. The role of energy density in the overconsumption of fat. Journal of Nutrition. 2000;130:268S–271S. doi: 10.1093/jn/130.2.268S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rolls BJ, Morris EL, Roe LS. Portion size of food affects energy intake in normal-weight and overweight men and women. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2002;76:1207–1213. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/76.6.1207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rolls BJ, Roe LS, Meengs JS. The effect of large portion sizes on energy intake is sustained for 11 days. Obesity. doi: 10.1038/oby.2007.182. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rolls BJ, Roe LS, Meengs JS. Larger portion sizes lead to sustained increase in energy intake over two days. Journal of the American Dietetic Association. 2006;106:543–549. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2006.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stunkard AJ, Messick S. The three-factor eating questionnaire to measure dietary restraint, disinhibition, and hunger. Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 1985;29:71–83. doi: 10.1016/0022-3999(85)90010-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Research Service. USDA Nutrient Database for Standard Reference, Release 19. Nutrient Data Laboratory Home Page. 2006 http://www.ars.usda.gov/nutrientdata.

- U.S. Department of Agriculture, Center for Nutrition Policy and Promotion. How much are you eating? Putting the Guidelines into Practice. Home and Garden Bulletin No. 267–1 2002 [Google Scholar]

- Wansink B. Environmental factors that increase the food intake and consumption volume of unknowing consumers. Annual Review of Nutrition. 2004;24:455–479. doi: 10.1146/annurev.nutr.24.012003.132140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wansink B, Cheney MM. Super Bowls: serving bowl size and food consumption. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2005;293:1727–1728. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.14.1727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wansink B, van Ittersum K, Painter JE. Ice cream illusions bowls, spoons, and self-served portion sizes. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2006;31(3):340–343. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2006.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young LR, Nestle M. Expanding portion sizes in the US marketplace: implications for nutrition counseling. Journal of the American Dietetic Association. 2003;103:231–234. doi: 10.1053/jada.2003.50027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuhas JA, Bolland JE, Bolland TW. The impact of training, food type, gender, and container size on the estimation of food portion sizes. Journal of the American Dietetic Association. 1989;89:1473–1477. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zung WWK. Zung self-rating depression scale and depression status inventory. In: Sartorius N, Ban TA, editors. Assessment of Depression. Berlin: Springer-Verlag; 1986. pp. 221–231. [Google Scholar]