Abstract

Histone lysine methylation plays an important role in the regulation of gene expression and impacts many fundamental biological processes, such as cellular identity. Despite great efforts, the mechanisms behind the downstream consequences of histone methyl-recognition remains poorly understood. Here, we describe various methods to investigate specific histone lysine-methyl recognition, including the use of short peptides, histone octamers, and the more physiological nucleosomal arrays. We also discuss techniques that are well suited to assess functional aspects of binding as it relates to transcriptional regulation.

Keywords: histone, methylation, nucleosome, octamer, peptide, transcription, compaction, modification

1. Introduction

Histones, the most abundant nuclear proteins in eukaryotic cells, were regarded as merely structural components to package more than 1 meter of DNA into the cell‘s nucleus. The complex assemblage of histones and DNA is termed chromatin; the fundamental unit of chromatin, the nucleosome, is composed of two copies each of the core histones H2A, H2B, H3 and H4, around which 147 base pairs of DNA is wrapped in 1.75 helical turns. Recently, a number of chromatin modifying enzymes have been identified that play an important role in altering chromatin structure, thereby maintaining genomic regions with a highly compacted (heterochromatin) or open (euchromatin) architecture. Chromatin is now viewed as a highly dynamic entity and its modulation provides the basis for a multitude of nuclear processes including the regulation of transcription.

The amino termini of histones (histone tails) are accessible domains that protrude out of the nucleosome. Residues from the amino and carboxy termini of histones H3, H4, H2A, and H2B, as well as the linker histone H1, are susceptible to a variety of post-translational modifications. One type of modification, histone lysine methylation, is catalyzed by histone lysine methyltransferases (HKMTs) and six lysine residues of histones H3 and H4 and one lysine residue of histone H1 have been identified to be target sites of methylation: lysines 4, 9, 27, 36, 79 of histone H3, lysine 20 of histone H4 and lysine 26 of histone H1b (1, 2). In contrast to other histone modifications, histone lysine methylation can exist in a mono-, di- or tri-methylated state. Interestingly, histone lysine methylation impacts both transcriptional activation and repression, dependent on the particular site and degree of methylation (1, 2).

Histone lysine methylation does not change the overall charge density between nucleosomal DNA and histones, as does histone acetylation; accordingly, histone methylation marks cannot directly alter chromatin structure. A model was proposed that histone methylation marks provide a recognition surface for highly specific chromatin binding modules, which in turn mediate changes to chromatin structure and perform biological functions downstream of binding (3, 4). Therefore, current research has focused on identifying novel chromatin binding proteins specific for a particular histone methylation mark. Despite our increased knowledge of histone methyl binding/release events, surprisingly little is known about the actual functional consequences of binding. Here we describe a variety of methods that determines if a protein of interest specifically binds to histones in a histone lysine methylation dependent manner. In addition, we discuss various methods to analyze for functions downstream of histone methyl lysine binding for a given protein.

2. Material and methods

2.1. Preparation of histone substrates

Recombinant Xenopus histone octamers were prepared as described previously (5) and in a previous issue of Methods (5). Native histone octamers were purified as described previously in Methods (5).

2.2. Production of recombinant proteins

The pGEX6P1 plasmid was used for the generation of expression constructs and the production of recombinant GST-fusion proteins. The full-length coding sequence of the longest L3MBTL1 isoform (Acc. U89358), and fragments comprising nucleotides 1–615 (L1N), 589–1675 (3MBT) and 1734–2046 (L1C) were amplified, inserted into pGEX6P1 using the restriction sites BamH1 and Xho1 and the final expression constructs transformed into E.coli BL21 DE3. Two liters of LB medium were inoculated with transformed bacterial colonies and the expression of GST protein and GST-fusion proteins were induced by the addition of 1 mM isopropylthiogalactoside (IPTG). After IPTG-induction bacteria were grown for 3 hours, cells pelleted by centrifugation (5000 rpm, 10 minutes, 4°C, GSA rotor, Sorvall) and the cell pellet resuspended in 20 ml of phosphate buffered saline (PBS). Cell suspension was sonicated three times with 45% amplitude for 30 seconds on ice (Branson Digital Sonifier). Sonicated suspension was centrifuged (13000 rpm, 20 minutes, 4°C, SA-600 rotor, Sorvall) and the supernatant (containing soluble GST-fusion proteins) used for affinity purification. Glutathione sepharose 4FF (1 ml; GE Healthcare) resin was equilibrated with three times 10 volumes of PBS and incubated in batch with the soluble bacterial protein fraction for 4 hours at 4°C on a rotating wheel. The suspension with the resin was poured into an empty Bio-Spin 30 column (Biorad) and the resin was washed on column for three times with 5 volumes of PBS using gravity flow. Elution of bound GST or GST-fusion proteins was performed by adding 4 times 1 volume of elution buffer (50 mM Tris, pH 8.0, 10 mM glutathione reduced). Fractions were analyzed by SDS-polyacrylamide-gel-electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE, 10%) with subsequent Coomassie Blue staining. Fractions containing GST and GST-fusion proteins were pooled, dialyzed against HE buffer (10 mM Hepes pH 7.6, 0.2 mM EDTA, 25 mM KCl) and used for various histone binding experiments.

2.3 Preparation of nucleosomal substrates

Nucleosomal arrays were prepared using the histone chaperone RSF essentially as described previously in Methods (5). Alternatively, plasmid pG5E4 (containing 10 5S rDNA nucleosome positioning sequences; (6)) is first linearized by Xba I and then combined with recombinant or native octamers in equimolar amounts in TEN2 buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.6, 0.2 mM EDTA, 2 M NaCl). Nucleosome arrays are assembled by step-wise salt dialysis in TEN1.6, TEN1.2, TEN1.0, TEN0.8 and TEN0.5 at 4 °C for 2 hours each step. Finally, the nucleosomal arrays are dialyzed against HE buffer (10 mM Hepes pH 7.6, 0.2 mM EDTA, 25 mM KCl) at 4 °C overnight. To examine the incorporation of histone octamers, the nucleosomal arrays are digested with MNase and resolved by agarose electrophoresis as previously described in Methods (5).

2.4 Histone methyltransferase (HMT) assay

HMT assays were carried out as previously described in Methods (7). HMT assays on nucleosomal substrates for subsequent binding assays or in vitro transcription assays are performed as follows: In a final reaction volume of 25 μl, 50–100 ng of recombinant HKMT protein is incubated at 30°C for 120 minutes in a reaction buffer containing 50 mM Tris–HCl, pH 8.5, 5 mM MgCl2, 4 mM DTT, 100 μM S-adenosyl-L-methionine (SAM; Sigma) and 2 μg of oligonucleosomal substrate. Nucleosomes were dialyzed against HE buffer and subsequently used for nucleosome binding experiments.

3. Results and discussion

3.1 Histone pull-down experiments

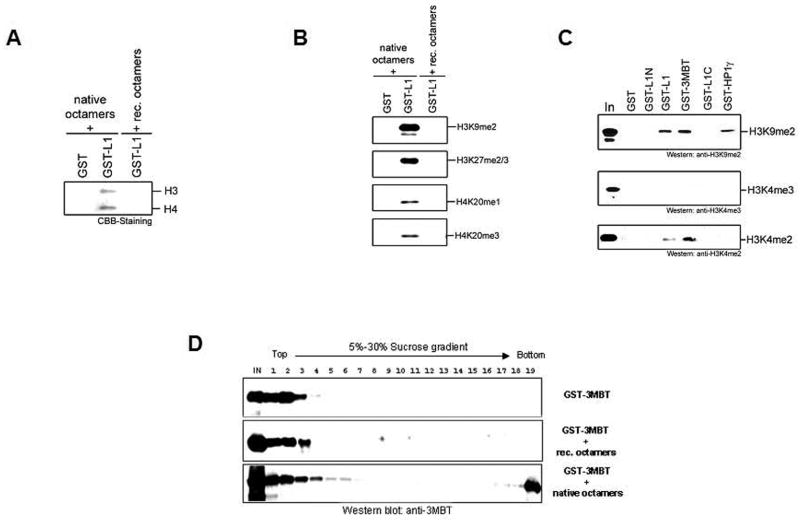

Before studies with histone peptides were popularised, interactions with full-length histones have been used extensively. This method requires a recombinant affinity-tagged protein of interest, which is analyzed for binding to reconstituted recombinant octamers or native purified octamers. Below we describe this technique in the context of a protein that was recently proposed to bind methylated lysine residues within histones H3 and H4, L3MBTL1 (20). To explore if the MBT-family member L3MBTL binds histones in a strictly histone modification dependent manner, a recombinant GST-fusion protein of L3MBTL1 (GST-L1) was produced. The purified GST-fusion protein (2–4 μg) was incubated with equimolar amounts of recombinant or native octamers in a total volume of 250 μl for 2 hours at 4°C on a rotating wheel. In parallel, the GST-moiety alone was purified similarly and also incubated with octamers. Glutathione-sepharose 4FF beads (40 μl; equilibrated with PBS) were added and the reactions were further incubated for 2 hours. Beads were centrifuged (1000 g; 2 min) washed three times with 500 μl of PBS, and bound proteins eluted with elution buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl pH8.0, 10 mM glutathione). Elution fractions were analyzed by SDS-PAGE (12%) with subsequent Coomassie Blue staining or Western blotting. GST-L1 specifically bound to native but not to recombinant octamers (Fig. 1A). Of note, octamers are stable in a buffer containing 2M NaCl, but the pull-down experiment is carried out in lower salt concentrations. During the incubation, histone octamers disaggregate into H3/H4 tetramers and H2A/H2B dimers. Based on the above results, we conclude that L3MBTL1 interacts with histones in a histone modification dependent manner and the binding seems to be limited to the H3/H4 tetramer. Since it was shown previously that the MBT-domains interact with methylated histone lysines (20, 22), the GST-L1 precipitated histones were analyzed for the enrichment of various histone methylation marks on histones H3 and H4. A variety of histone methylation marks were detected by Western blotting (Fig. 1B), but no enrichment for one particular methylated site was observed. However, we noticed that all of the detected methylation marks correlate with transcriptional repression. For instance, H3K4me3, a hallmark of transcriptionally active chromatin, was absent in the GST-L1 precipitated histone fraction (Fig. 1C and data not shown).

Figure 1. Histone pulldown assay.

A. Recombinant GST and GST-L3MBTL1 (GST-L1) proteins were incubated with native histone octamers, precipitated with glutathione sepharose 4FF, and resolved by SDS PAGE. Precipitated histones were visualized by Coomassie Blue staining. As a negative control GST-L1 was also incubated with recombinant octamers (lane 3). B. Native histones precipitated by GST-L1 (see A) were analyzed by Western blot for the presence of various histone methylation marks. Anti-H3K9me2 (Upstate), anti-H3K27/me2/3 (Reinberg Lab), anti-H4K20me1 (Upstate) and anti-H4K20me3 (Upstate) have been used for the analysis. C. Recombinant GST, fragments of L3MBTL1 (GST-L1N, GST-3MBT, GST-L1C; see Materials and Methods) and GST-HP1γ proteins were incubated with native histone octamers, precipitated with glutathione sepharose 4FF and resolved by SDS-PAGE. Precipitated histones were analyzed by Western blot using anti-H3K9me2 (Upstate), anti-H3K4me3 (ABCAM) and anti-H3K4me2 (Upstate) antibodies. D. Recombinant GST-3MBT protein was fractionated either alone or in the presence of recombinant or native histone octamers by sucrose gradient sedimentation (see Materials and Methods). Fractions were collected and analyzed by Western Blot using anti-3MBT antibodies (27). Notably, GST-3MBT migrated on the top of the gradient, but shifted towards the bottom of the gradient upon binding to native histones.

The histone pull-down technique is also suitable in determining the region of a protein that mediates the histone interaction. We generated GST-fusion proteins comprising the N-terminus (GST-L1N), the C-terminus (GST-L1C) or the central region (containing the three MBT-domains; GST-3MBT) of L3MBTL1. We repeated the histone pull-down experiments with native histones as described above and analyzed the precipitated fractions by Western blotting. As expected, we detected histones only in the GST-3MBT precipitated sample, confirming that the MBT-domain mediates the interaction to histones. GST-HP1γ was produced similarly to GST-L1 and served as a positive control for H3K9me binding. Interestingly, H3K4me2 a modification present on transcriptionally active and inactive chromatin (17) was absent in the GST-HP1γ but present in the GST-3MBT precipitated material (Fig. 1C).

Although we determined that GST-L1 has a preference for binding to post-translationally modified (native) octamers, the basis of this interaction was not clear. Therefore, we analyzed histones/GST-3MBT protein complexes by sucrose gradient fractionation (5–30 % sucrose gradient in HE buffer (10 mM Hepes pH 7.6, 0.2 mM EDTA, 25 mM KCl) for 6.5–15 hours at 30000 RPM; Beckman SW41 rotor). Gradient fractions were analyzed by Western blotting using anti-3MBT antibodies. Fractions from the top of the gradient correlate with less dense species, whereas fractions from the bottom correlate with those of higher molecular weight. Recombinant GST-3MBT protein alone migrated at the top of the gradient and addition of recombinant octamers did not affect the migration of GST-3MBT protein. However, GST-3MBT shifted towards the bottom of the gradient upon addition of native octamers (Fig. 1D). Interestingly, a substantial amount of GST-3MBT was recovered from the bottom of the gradient (fraction 19), which represents aggregated material. Aggregation of GST-3MBT protein was only observed upon addition of native octamers (compare Fig. 1D bottom panel with top and middle panel). The reason for this effect remains unresolved.

Overall, the histone pull-down experiment is a simple but valuable method to initially screen for histone binding properties of a given protein. As a minimal criterion for the validity of this technique it needs to be ruled out that neither the recombinant protein, nor the protein-histone complexes form protein aggregates. However, while useful, this method is in most cases insufficient to identify the modified histone residue that serves as a recognition site for the protein of interest.

3.2 Peptide Affinity Precipitation

Peptides encompassing various lengths of the different histone amino termini have proved to be a valuable resource in deciphering the basis for histone modification readout. These peptides have been used to identify novel binders, elucidate histone tail participation in enzymatic processes, and study the structural and physical aspects of histone tail recognition, among other findings. We begin our discussion with the most commonly used method for studies of histone tail binding, peptide affinity precipitation.

The first published studies that demonstrated proteins indeed directly and selectively recognize methylated lysines within histone tails used peptide affinity precipitation. These studies, which indicated that the chromodomain of HP1 directly recognizes the H3K9me mark, gave the first indication that histone tails can serve as a recruitment platform for effector proteins. The method used was quite simple, utilizing peptides that included the amino terminus of histone H3 covalently cross-linked to agarose (8, 9). After incubation with recombinant HP1, the agarose-peptide beads were washed and resolved by SDS-PAGE electrophoresis. This assay closely mimics co-immunoprecipitation, replacing specific antibodies with histone tail peptides. Due to its straightforward protocol and simple manipulations, many groups have used this assay to study similar interactions. In addition, peptides are commercially available in a wide array of modified states, increasing the popularity of this assay. Peptide affinity chromatography has served as a suitable method to screen for novel proteins that specifically recognize modified histone tails. Among the proteins identified include, HP1, PC, CHD1, BPTF, and the ING family (ING1-5) (8–15). However, this approach should never be used as the sole indicator of specific physical interactions, as it has yielded inaccurate and/or confusing results on multiple occasions. Moreover, it is necessary to use full-length proteins to confirm the results obtained with isolated protein domains by themselves. Instances have arisen wherein protein fragments appear to bind specifically to methylated lysines, but the full-length protein has differing specificity or does not bind at all (yeast CHD1 binding to H3K4me2, (16); CHD3 binding to H3K36me, (15)). Both cellular extracts and recombinant proteins can be used successfully as input material.

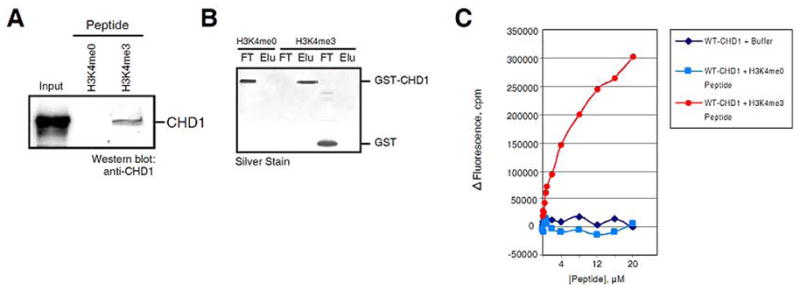

In order to characterize novel factors that recognize histone H3 tri-methylated on lysine 4 (H3K4me3), a mark tightly correlated with active transcription (17, 18), we generated an affinity resin using a peptide encompassing the first 8 amino acids of histone H3 tri-methylated on lysine 4. A carboxy-terminal cysteine was synthesized as the last amino acid on the H3 tail peptide for covalent attachment to the agarose resin. Global Peptide Services generated the synthesized peptides. Sulfolink Coupling Gel from Pierce was used according to the manufacturer’s instructions and in order to covalently immobilize sulfhydryl-containing peptides. The resin is designed with a 12-atom spacer to reduce steric hindrance. Anywhere from 0.5–1 mg/ml peptide per ml of dry resin can be used, depending on the peptide to be cross-linked. When comparing binding between two different peptides, the molar amounts of the peptides to be immobilized must be equalized to one another. For the binding reactions, 200 ul of peptide-conjugated resin was used in a 2 ml disposable column from BioRad (Bio-Spin). 1 mg of nuclear extract was used in a final reaction volume of 500 ul in low IPB buffer (25 mM Tris, pH 8, 150 mM NaCl, 2 mM EDTA, and 0.5% NP40) containing the protease inhibitor PMSF (0.2 mM). Nuclear extracts from HeLa cells were generated from standard protocols (19). Nuclear extract plus conjugated resin was incubated overnight at 4º C with rotation and then were washed with 12 ml low IPB buffer plus PMSF (60 column volumes). Resin elution was performed with the same peptides conjugated to the Sulfolink agarose at a concentration of 0.5 mg/ml (1 column volume; 2 elutions). When eluting with peptides (with rotation at 4º C), the incubation time with peptide can also be varied from immediate to 15 minutes, depending on the degree of specificity. Using a combination a mass spectrometry and western blotting, we identified the ATP-dependent chromatin remodeling protein CHD1 as a specific H3K4me3-binding factor (13)(Fig. 2A). Factors to consider when using this approach are the amount of peptide and resin volume, input amount, binding and wash buffer composition, wash volumes, binding duration, and elution method (peptide or low pH buffer: 100 mM glycine, pH 2.7). Given these variables, it is highly advisable to start with known interactions to establish specific binding conditions before performing studies with uncharacterized histone tail-protein associations.

Figure 2. Human CHD1 binds specifically to H3K4me3.

A. Western analyses (anti-CHD1 antibodies) of the elution fraction from either the H3K4me0 or H3K4me3 peptide columns derived from HeLa nuclear extracts. B. Silver stain of either GST or GST-CHD1 (tandem chromodomains only) binding to H3K4me0 or H3K4me3 peptide columns. C. Graphic representation of the change in CHD1 intrinsic fluorescence upon peptide titrations, indicated as counts/min (cpm). The peptide concentration is indicated. Figure and legend taken from (13).

After identifiying potential histone lysine methyl-binding proteins from extracts, it is necessary to determine if the protein of interest binds directly to the affinity resin. In the case of CHD1, an expression vector was used to generate a GST fusion protein containing the tandem chromodomains of human CHD1. Recombinant GST-fusion proteins were prepared as described in the Methods section. For binding reactions using recombinant proteins, 150 ul of peptide-conjugated resin was used in a 2 ml disposable column from BioRad (Bio-Spin). 10 ug of highly purified protein was typically used in a final reaction volume of 300 ul low IPB plus PMSF and incubated for 2 hours at 4º C with rotation. Recombinant proteins bound to the peptide affinity resin were washed with 12 ml low IPB buffer plus PMSF (60+ column volumes) and eluted with low pH buffer (100 mM glycine, pH 2.7; 1 column volume; 2–3 elutions; neutralized with 1/10 volume 1M Tris-Cl, pH 8.0). As shown in Fig. 2B, GST-CHD1 bound specifically to H3K4me3 peptides, but not to unmodified H3K4. It is recommended to use a variety of control peptides to confirm the specificity of interaction. More sophisticated approaches utilizing peptides have also been used to identify novel binders of modified histone tails. In particular, one method used glass slides that adhered numerous protein domains implicated in modified histone tail binding (20). These protein “chips” were then incubated with fluorescently labeled peptides, washed, and visualized to detect protein-peptide interactions. The domains present on these chips were from proteins containing the chromo, tudor, PWWP, SANT, MBT, and PhD domains. A number of known histone tail interactions were used as standards for determining the accuracy of the interactions. Using this assay, a number of new binders were identified, including novel MBT and tudor-domain containing proteins. While useful, this approach failed to identify a number of proteins that have since been discovered to directly bind methylated lysine residues. This underscores the disadvantages of using only one biochemical technique in studies of histone tail-binding proteins.

3.3 Quantitative Analyses using Peptides

Quantitative studies of histone tail interactions provide valuable supportive information regarding the biophysical nature of these associations. Most importantly, they supply corroborating evidence that the detected interactions are indeed specific. A variety of different quantitative assays for measuring protein-peptide interactions have been used to study the role of histone tail modifications. The most commonly used techniques include Fluorescence Spectroscopy, Isothermal Titration Calorimerty, and NMR Spectroscopy. For detailed and complete analyses of these approaches, a recently published article nicely covers this topic (21). Fluorescence Spectroscopy is widely used to determine dissociation constants of various protein-peptide interactions. The simplest method monitors changes in the intrinsic tryptophan fluorescence of the protein upon peptide binding. This approach is favorable to other assays because no modifications or alterations are made to the protein or peptide and multiple binding events are easily determined. However, this method is limited in that some protein-peptide interactions may not result in fluorescence changes. Fig. 2C provides an example of this technique to monitor CHD1-H3K4me3 interactions. Fluorimetric peptide titration experiments presented in Fig. 2C were performed using a FluoroMax-2 spectrofluorimeter (Spex Instruments) using 25 mM NaCl, and 25 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0. A constant amount of protein was used during peptide titrations (100 nM). Excitation was performed at 295-nm and the emission was detected at 340-nm. Fluorescence values were corrected for sample dilution and resulting data were fit to Equation 1.

Where Fc is observed fluorescence, fE is the fluorescence change, fb is the background fluorescence, [P] is peptide concentration, and Kd is the equilibrium dissociation constant of the peptide-protein complex. The equilibrium dissociation constant of CHD1 binding to H3K4me3 was determined to be ~5 μM. Binding between the protein and peptide was allowed to proceed for 60 seconds before quantitiative measurements were determined.

In addition to using the intrinsic tryptophan fluorescence of the protein “reader“, fluorescence anisotropy is frequently used to study similar interactions. This approach utilizes an extrinsic fluorescent probe that is covalently attached to either the protein or, more commonly, the peptide. This approach has limitations as well. Given that most interactions with histone tails have low affinities (1–20 uM), very high concentrations of protein samples are needed since a range of 0.1 uM to 1 mM protein is recommended for these types of studies (21). A number of practical considerations come into play when using proteins at these concentrations, including solubility and viscosity, as fluorescent anisotropy measurements are directly effected by viscosity. Additionally, most fluorescent spectroscopy is performed in very low salt (~25 mM), so the dissociation constants derived from this method has legitimate, although limited value. Considering these limitations, it is recommended that several techniques be used to determine a complete picture. It is therefore ideal to also use methods that do not rely solely on peptide fragments, but rather the entire histone octamer or nucleosome.

3.4 Nucleosome binding assay

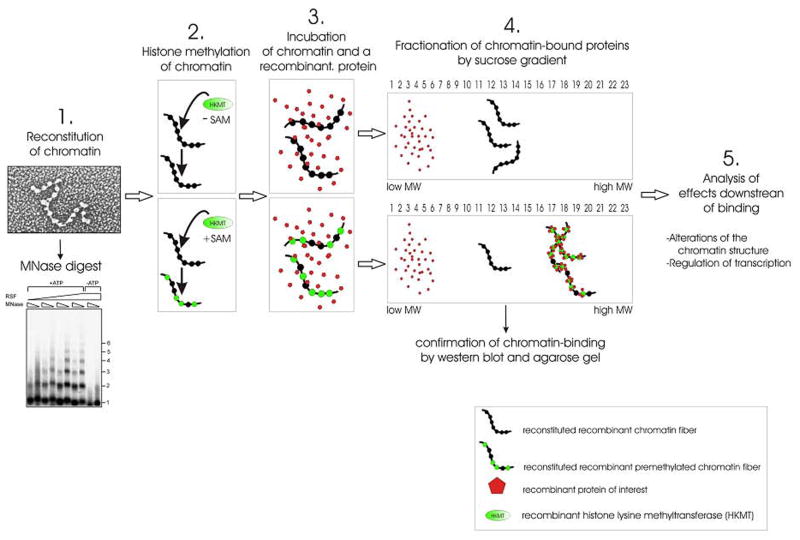

To extend beyond simple peptides and histone octamers, it is useful to utilize nucleosomal substrates in order to study histone-binding in a more natural context. Nucleosomal arrays can be reconstituted with bacterially expressed histones (recombinant chromatin) or histones purified from HeLa cells (native chromatin) using a histone chaperone like RSF or stepwise salt dialysis (see Materials and Methods). To analyze binding to nucleosomes, nucleosomal arrays (2 μg) should be incubated with recombinant proteins in HE buffer (10 mM Hepes pH 7.6, 0.2 mM EDTA, 25 mM KCl) at a molar ratio of 1:4, respectively, at RT for 60 minutes in a total volume of 100 μl. The resultant protein-nucleosome complexes can then be loaded onto a 5–30 % sucrose gradient (total volume 4 ml) in HE buffer and run for 6.5–15 hours at 30000 rpm (Beckman, SW41 rotor). Fractions from the gradient are prepared by removing 130 μl from the top of the gradient in a step-wise fashion. Gradient fractions can then be analyzed by Western blotting and agarose gel electrophoresis to visualize nucleosomal DNA (Fig. 3). Recombinant proteins that do not interact with chromatin migrate at the top of the gradient, whereas factors that specifically interact with nucleosomal arrays should shift towards the bottom of the gradient (Fig. 3).

Figure 3. Representative description of the nucleosome binding assay.

(1) Recombinant chromatin was reconstituted as described in Materials and Methods, and the quality of reconstituted chromatin template analyzed by micrococcal nuclease (MNase) digest and electron microscopy. (2) Reconstituted nucleosomal arrays are incubated with a histone lysine methyltransferase (HKMT) of interest either in the presence or absence of S-adenosylmethionine (SAM) (see Materials and Methods for HMT assay). (3) Methylated and non-methylated nucleosomal arrays are incubated with a recombinant protein of interest. (4) Protein-nucleosome complexes are fractionated by sucrose gradient sedimentation. Proteins that bind nucleosomes in a histone lysine methylation dependent fashion bind to the methylated but not to the unmethylated nucleosomal array and shift to a higher molecular weight. (5) Fractions of the sucrose gradient that contain the proteins bound to chromatin can be further analyzed to explore potential changes to the chromatin structure, e.g. compaction. Moreover, these fractions can be also studied functionally if for instance subjected to in vitro transcription assays.

This method is useful to examine if a protein preferentially binds to post-translationally modified histones in the context of nucleosomal arrays. Moreover, this technique can also be used to recapitulate binding to a specific, single histone methyl mark. Towards this end, recombinant nucleosomal arrays (devoid of any histone methylation mark) are incubated with a recombinant HKMT either in the absence or presence of SAM (for details regarding the HMT assay, see Materials and Methods). Subsequently, methylated and non-methylated nucleosomal arrays are incubated with the recombinant protein of interest and the binding assay is carried out as described above. If specific binding occurs, the protein-nucleosome complex should only be observed in the presence of SAM (i.e. methylation).

Histone binding assays using nucleosomes are more physiologically relevant when compared to histone pull-down and peptide affinity techniques. Recombinant and native reconstituted nucleosomal arrays display a typical “beads on a string” configuration. In addition, the peak fractions from the sucrose gradient can be further analyzed by electron microscopy to explore any visible changes to the chromatin template upon interaction with chromatin-binding proteins. For instance, compaction of nucleosomal arrays occurs in vitro upon incubation with histone H1 (23), the Polycomb complex PRC1 (24) or PARP-1 (25). Besides compaction, the functional outcome of binding to nucleosomes can be monitored using an in vitro transcription system (see below). As such, it is important to determine if chromatin compaction functionally impacts the regulatory events that result in active transcription.

3.5 Concluding remarks: the need for functional-based analyses

In order to fully understand the molecular mechanisms behind histone modifications as it relates to gene regulation, functional biochemical studies that extend beyond simple protein-protein interactions must be utilized. These approaches were mentioned in the previous section and include monitoring the compaction of chromatin by electron microscopy and the functional consequences during in vitro transcription reactions. Aside from studies of factors that compact chromatin and repress gene expression, cell-free transcription assays using chromatinized templates are well suited for deciphering the mechanisms of histone modifications in transcriptional activation. Moreover, it is important to use a fully reconstituted transcription system, in order to minimize the indirect effects that could occur when using nuclear extracts. This approach was recently utilized to demonstrate that H2B monoubiquitination facilitates the functional activities of FACT, a heterodimer that allows RNA polymerase II (RNAPII) to traverse nucleosomes (26). Specifically, H2B monoubiquitination was observed to increase the elongation rates of RNAPII in a FACT-dependent manner. This study provides the first clear evidence that a histone modification directly affects functional processes linked to gene expression. This approach will likely serve to elucidate the functions of other histone modifications. Moreover, additional function-based assays are desperately needed to complement many in vivo studies that are limited in their ability to discern molecular mechanisms. Cell-free systems that utilize fully reconstituted factors, perhaps those that recapitulate DNA replication or DNA repair, would provide the necessary assays required to discern the mechanisms of histone methylation in these processes. Such advancements should prove invaluable in our efforts to achieve a complete understanding of chromatin biology.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. L. Vales for helpful comments on the manuscript. DR and RJS are supported by the HHMI (DR) and grants from NIH (GM-37120 to DR, GM-71166 to RJS).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Margueron R, Trojer P, Reinberg D. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2005;15:163–76. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2005.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sims RJ, 3rd, Nishioka K, Reinberg D. Trends Genet. 2003;19:629–39. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2003.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Strahl BD, Allis CD. Nature. 2000;403:41–5. doi: 10.1038/47412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Turner BM. Bioessays. 2000;22:836–45. doi: 10.1002/1521-1878(200009)22:9<836::AID-BIES9>3.0.CO;2-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Loyola A, Reinberg D. Methods. 2003;31:96–103. doi: 10.1016/s1046-2023(03)00093-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Simpson RT, Stafford DW. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1983;80:51–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.80.1.51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nishioka K, Reinberg D. Methods. 2003;31:49–58. doi: 10.1016/s1046-2023(03)00087-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bannister AJ, Zegerman P, Partridge JF, Miska EA, Thomas JO, Allshire RC, Kouzarides T. Nature. 2001;410:120–4. doi: 10.1038/35065138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lachner M, O’Carroll D, Rea S, Mechtler K, Jenuwein T. Nature. 2001;410:116–20. doi: 10.1038/35065132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cao R, Wang L, Wang H, Xia L, Erdjument-Bromage H, Tempst P, Jones RS, Zhang Y. Science. 2002;298:1039–43. doi: 10.1126/science.1076997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Czermin B, Melfi R, McCabe D, Seitz V, Imhof A, Pirrotta V. Cell. 2002;111:185–96. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00975-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kuzmichev A, Nishioka K, Erdjument-Bromage H, Tempst P, Reinberg D. Genes Dev. 2002;16:2893–905. doi: 10.1101/gad.1035902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sims RJ, 3rd, Chen CF, Santos-Rosa H, Kouzarides T, Patel SS, Reinberg D. J Biol Chem. 2005 doi: 10.1074/jbc.C500395200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wysocka J, Swigut T, Xiao H, Milne TA, Kwon SY, Landry J, Kauer M, Tackett AJ, Chait BT, Badenhorst P, Wu C, Allis CD. Nature. 2006 doi: 10.1038/nature04815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shi X, Hong T, Walter KL, Ewalt M, Michishita E, Hung T, Carney D, Pena P, Lan F, Kaadige MR, Lacoste N, Cayrou C, Davrazou F, Saha A, Cairns BR, Ayer DE, Kutateladze TG, Shi Y, Cote J, Chua KF, Gozani O. Nature. 2006 doi: 10.1038/nature04835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pray-Grant MG, Daniel JA, Schieltz D, Yates JR, 3rd, Grant PA. Nature. 2005;433:434–8. doi: 10.1038/nature03242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bernstein BE, Kamal M, Lindblad-Toh K, Bekiranov S, Bailey DK, Huebert DJ, McMahon S, Karlsson EK, Kulbokas EJ, 3rd, Gingeras TR, Schreiber SL, Lander ES. Cell. 2005;120:169–81. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schneider R, Bannister AJ, Myers FA, Thorne AW, Crane-Robinson C, Kouzarides T. Nat Cell Biol. 2004;6:73–7. doi: 10.1038/ncb1076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dignam JD, Lebovitz RM, Roeder RG. Nucleic Acids Res. 1983;11:1475–89. doi: 10.1093/nar/11.5.1475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kim J, Daniel J, Espejo A, Lake A, Krishna M, Xia L, Zhang Y, Bedford MT. EMBO Rep. 2006;7:397–403. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7400625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jacobs SA, Fischle W, Khorasanizadeh S. Methods Enzymol. 2004;376:131–48. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(03)76009-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Klymenko T, Papp B, Fischle W, Kocher T, Schelder M, Fritsch C, Wild B, Wilm M, Muller J. Genes Dev. 2006;20:1110–22. doi: 10.1101/gad.377406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bednar J, Horowitz RA, Grigoryev SA, Carruthers LM, Hansen JC, Koster AJ, Woodcock CL. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:14173–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.24.14173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Francis NJ, Kingston RE, Woodcock CL. Science. 2004;306:1574–7. doi: 10.1126/science.1100576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kim MY, Mauro S, Gevry N, Lis JT, Kraus WL. Cell. 2004;119:803–14. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Reinberg D, Sims RJ., 3rd J Biol Chem. 2006 doi: 10.1074/jbc.R600007200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Boccuni P, MacGrogan D, Scandura JM, Nimer SD. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:15412–20. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M300592200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]