Abstract

BACKGROUND

Dihydrotestosterone (DHT) is believed to play an important role in prostate carcinogenesis. Five alpha reductase type II (SRD5A2) and 3 beta-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type II (HSD3B2) are responsible for the biosynthesis and degradation of DHT in the prostate. Two polymorphisms, a valine (V) for leucine (L) substitution at the 89 codon of the SRD5A2 gene and a (TG)n,(TA)n,(CA)n repeat polymorphism within the third intron of the HSD3B2 gene were evaluated with regard to prostate cancer risk.

METHODS

Blood samples were collected for 637 prostate cancer cases and 244 age and race frequency matched controls. In analysis, the SRD5A2 VL and LL genotypes were combined into one group and the HSD3B2 repeat polymorphism was dichotomized into short (<283) and long (≥283) alleles.

RESULTS

The SRD5A2 V89L polymorphism was not independently associated with prostate cancer risk. Carriage of at least one HSD3B2 intron 3 intron 3 short allele was associated with a significant increased risk for prostate cancer among all subjects (OR = 2.07, 95% CI =1.08–3.95, P = 0.03) and Caucasians (OR = 2.80, CI = 2.80–7.43, P = 0.04), but not in African Americans (OR = 1.50, CI =0.62–3.60, P =0.37). Stratified analyses revealed that most of the prostate cancer risk associated with the intron 3 HSD3B2 short allele was confined to the SRD5A2 89L variant subgroup and indicated that in combination these polymorphisms may be associated with increased risk of aggressive (Gleason >7) disease (Gleason >7).

CONCLUSIONS

In Caucasians, the HSD3B2 (TG)n,(TA)n,(CA)n intron 3 length polymorphism is associated with both prostate cancer risk and aggressiveness and the SRD5A2 V89L polymorphism may modify the risk conferred by this polymorphism.

Keywords: SRD5A2 V89L, HSD3B2, prostate cancer, African American

INTRODUCTION

Prostate cancer incidence in African-American men is on average 60% higher than the incidence observed in Caucasian men and mortality from the disease is approximately 2.4 times higher in African-American men [1]. The androgen biosynthesis pathway has been implicated in prostate carcinogens is and frequency differences in gene polymorphisms within this pathway may explain observed race disparities in prostate cancer [2,3]. Androgens are primarily produced in the testes and adrenal glands, but are also synthesized in the prostate and skin. Within the prostate, dihydrotestosterone (DHT) is the primary and most potent nuclear androgen. DHT promotes DNA synthesis and cell replication by binding to the intracellular androgen receptor and forming a complex which activates gene transcription and cell proliferation. Increased cell division is presumed to heighten the potential for somatic mutations, leading to a higher likelihood of carcinogenesis [4]. Two enzymes involved in the regulation of DHT are 5-alpha reductase type II (SRD5A2) and 3 beta-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type II (HSD3B2). These enzymes are responsible for the biosynthesis and degradation of DHT.

The 5 α-reductase gene (SRD5A2), located on chromosome 2p23 [5], is involved in the conversion of testosterone to DHT in the prostate. SRD5A2 is perhaps best known as the target for finasteride, a drug used to treat benign prostatic hypertrophy and which has shown potential for prostate cancer prevention [6,7]. Several polymorphisms within SRD5A2 have been identified, including a leucine for valine substitution at codon 89 (V89L) [7]. Findings overall have been equivocal in regard to this polymorphism in terms of prostate cancer risk. A meta-analysis of the SRD5A2 V89L polymorphism concluded that there was no increased risk associated with prostate cancer (Odds ratio (OR) for L vs. V: 1.03, 95% CI: 0.84–1.26) [8]. However, in vivo and in vitro studies have consistently shown reduced 5 α-reductase activity with the substitution of leucine [9-11] and studies published since the meta-analysis in 2003 have found that the SRD5A2 V89L is associated with prostate volume [12] and prostate cancer risk and aggressiveness [13]. Race/ethnicity differences in the frequency of the L variant have also been reported [14].

HSD3B2 functions upstream as well as downstream of SRD5A2 in the androgen pathway and the coding region for the HSD3B2 gene is located on chromosome 1p13 [15], a region that has shown evidence for linkage to prostate cancer [16-19]. HSD3B2 is one of two enzymes responsible for the degradation of DHT to 3 β-androstanediol [20]. In addition, HSD3B2 is involved in the production of testosterone (T) via its role in converting DHEA to androstenedione, a precursor to testosterone. A complex (TG)n(TA)n(CA)n repeat polymorphism within the third intron of the HSD3B2 gene has been identified [21], and allelic frequency differences have been observed between African Americans and Caucasians [22]. It has been suggested that the repeat complex may influence the formation of hairpin-like structures that could modify the rate of HSD3B2 transcription [23] or may promote alternative spliced forms of mRNA resulting in truncated or unstable proteins [24]. Altering intracellular levels of HSD3B2 enzyme could potentially change the rate at which testosterone is produced and/or DHT is degraded. Higher ratios of serum testosterone to DHT have been associated more consistently with prostate cancer risk than either steroid alone [25-27]. To the best of our knowledge no previous reports have assessed the intron 3 repeat HSD3B2 polymorphism in regard to prostate cancer risk or aggressiveness.

Therefore, in this study, we evaluated the potential associations between the SRD5A2 V89L and HSD3B2 (TG)n(TA)n(CA)n repeat polymorphisms on prostate cancer risk and aggressiveness by race/ethnicity. We also evaluated these polymorphisms in combination since altered activity or expression of both may ultimately have a stronger impact on the availability of DHT and/or testosterone in the prostate potentially leading to increased cell division and prostate carcinogenesis.

METHODS

Study Population and Data Collection

The study population included men that received their primary health care at the Henry Ford Health System (HFHS), a large, vertically integrated, health system. HFHS provides care for an ethnically diverse population that is representative of the geographic region it serves. All study procedures and processes were approved by the HFHS institutional review board. Cases were identified through the centralized Department of Pathology and had histological confirmation of adenocarcinoma of the prostate between January 1999 and December 2004 with no prior history of prostate cancer. The primary objective of the study was to evaluate gene-environment interactions using a case-only analytic approach [28], therefore, the study sampling frame was focused on cases, but controls were also sampled in a stratified random manner from the health system’s electronic data stores based on 5-year age group and race, such that the final enrolled sample would include approximately 3 cases per 1 control. Cases and controls were also required to be 75 years of age or younger at diagnosis/enrolment and have at least one primary care contact in the preceding 5 years. The younger age criterion was used in this gene-environment study to enrich the potential genetic contribution to disease among our subjects.

A study introduction letter was sent to all potential subjects and trained study interviewers made initial contact with patients via telephone. Between July 2001 and December 2004, 77% of potential cases and 68% of potential controls enrolled in the study (total N = 881) and provided a blood sample for DNA analysis. Blood samples for controls were also used for prostate specific antigen testing (PSA) at the time of enrolment. Family history of prostate cancer was assessed as part of the patient interview and was considered positive if either a brother or father had been diagnosed with prostate cancer. Cases’ cancer stage and Gleason grade were abstracted from the medical record and were verified using the institutions certified tumor registry.

Genotyping

Genotyping of the SRD5A2 V89L polymorphism was performed using the Invader assay (biplex format). Each plate contained the following controls: valine/valine homozygous, valine/leucine heterozygous, leucine/leucine homozygous and a no target blank. All components of the assay were provided by Third Wave Technologies, Inc. Ten microliters of genomic DNA samples were aliquoted into individual wells of a 96-well microtitre plate and denatured at 95°C for 5 min. Ten microliters of a reaction mix containing the appropriate probes/Invader oligo/MgCl2 mix were added, and reactions were overlaid with 20 μl of mineral oil. Each 20 μl reaction contained 40 ng of Cleavase enzyme, 3.5% PEG 8000, 2% glycerol, 0.06% NP40, 0.06% Tween-20, 12 μg/ml BSA, 0.25 μmol/L each of F (FAM) dye and R (Redmond Red) dye FRET cassettes, 8 mmol/L MgCl2, 0.5 μmol/L of each allele-specific probe, and 0.05 μmol/L Invader oligo. The sequences of the oligos and probes are available upon request. The plates were incubated at 63°C for 4 hr in a PE 9700 thermal cycler. Fluorescence was measured using a CytoFluor 4000 fluorescence plate reader (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). The settings used were: 485/20 nm excitation/bandwidth and 530/25 nm emission/bandwidth for F dye detection, and 560/20 nm excitation/bandwidth and 620/40 nm emission/bandwidth for R dye detection. Any sample that yielded inconclusive results using the Invader assay was re-quantified and repeated. If the second attempt did not yield acceptable results, the sample was genotyped using a PCR-RFLP assay previously described [29].

The HSD3B2 intron 3 dinucleotide repeat was genotyped by first amplifying genomic DNA using a primer pair previously described [30]. The forward primer was fluorescent tagged with 6-carboxyfluorescerin (FAM). Amplification was performed in a 20 μl final volume containing 200 μM of dCTP, dATP, dGTP, and dTTP, 2 mM MgCl2, 20 pmol each primer, 2.5 U Taq Gold DNA polymerase (Perkin–Elmer), and 1 × Taq Gold buffer. After an initial denaturation step at 95°C for 10 min, 30 cycles of 92°C 2 min, 65°C 1 min and 72°C 2 min were followed by a 45 min final extension at 72°C.

The final products were analyzed by electrophoresis on a 3100 Genetic Analyzer (Applied Biosystems) using GeneScan and Genotyper software. The size of the PCR products for each specimen was determined by the size of the predominant PCR product(s) according to peak area, in relation to the GeneScan-500 ROX size standard (Applied Biosystems). GeneScan results for a sample of homozygous subjects were checked against the actual size of the PCR product as determined through sequence analysis and were determined to be similar.

Statistical Analyses

Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium of genotypic frequencies for both polymorphisms was verified in controls using chi-squared tests. For the multi-allele HSD3B2 polymorphism, an empirical P value was estimated using a simplified Monte Carlo significance test [31]. Case-control differences in categorical variables were assessed using chi-squared tests as well. SRD5A2 89 valine/leucine (VL) and leucine/leucine (LL) genotypes were combined for stratified analyses due to low frequencies of the LL genotype. Polynomial regression was used to test the linear association of the HSD3B2 (TG)n(TA)n(CA)n allele lengths with prostate cancer risk. Family history and benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) were coded as present or absent and were included in multivariable regression models as potential confounders because of previous reports indicating potential associations with the SRD5A2 V89L polymorphism [12,13,32,33]. Body mass index (continuous) and smoking status (ever/never) were also included in models as potential confounders since each has been shown to influence circulating androgen levels [34]. Age (continuous) was also included in each model and race was adjusted for in analyses of all subjects combined. Aggressive prostate cancer was defined as having Gleason grade of 7–10. Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS (version 11.5). Logistic regression was used to estimate odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for the association between genotypes and prostate cancer risk and aggressiveness, respectively. An alpha level of P <0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

Demographics and Clinical Characterization

A total of 637 cases and 244 controls met all criteria and were enrolled in the study (Table I). By design, cases and controls did not differ significantly by race or age. African-American (AA) men represented 43.2% of all participants and were slightly younger than Caucasian (W) subjects (61.8 vs. 62.6 years, P = 0.06). Family history of prostate cancer (21.0% vs. 13.1%, P = 0.01) and BPH (32.3% vs. 19.7%, P <0.0001) were more prevalent in cases than in controls but did not differ by race (family history: AA 19.4% vs. W 18.6%, P = 0.76; BPH: AA 26.8% vs. W 30.6%, P = 0.34). Among cases, 55% had a Gleason grade of seven or greater and one in five cases undergoing definitive surgical treatment had a pathological tumor stage of T3 or higher. Gleason grade (AA 57.1% vs. W 53.5%, P = 0.37) and pathological tumor stage (AA 18.1% vs. W 20.1%, P = 0.61) were not significantly different between African-American and Caucasian cases.

TABLE I.

Patient Characteristics

| Characteristic | Controls N =244 n (%) | Cases N =637 n (%) | P-value* |

|---|---|---|---|

| Race | |||

| African American | 104 (42.7) | 274 (43.0) | 0.92 |

| White | 140 (57.4) | 363 (57.0) | |

| Age | |||

| <60 | 76 (31.2) | 228 (35.8) | 0.39 |

| 60–69 | 130 (53.3) | 323 (50.7) | |

| 70+ | 38 (15.6) | 86 (13.5) | |

| Smoking | |||

| Never | 82 (33.6) | 219 (34.4) | 0.83 |

| Ever | 162 (66.4) | 418 (65.6) | |

| BMI | |||

| <25 | 45 (18.4) | 127 (19.9) | 0.43 |

| 25–29 | 108 (44.3) | 302 (47.4) | |

| ≥30 | 91 (37.3) | 208 (32.7) | |

| Family history | |||

| Positive | 32 (13.1) | 134 (21.0) | 0.01 |

| Negative | 212 (86.9) | 503 (79.0) | |

| BPH history | |||

| Positive | 48 (19.7) | 206 (32.3) | <0.0001 |

| Negative | 193 (79.1) | 430 (67.5) | |

| Unknown | 3 (1.2) | 1 (0.2) | |

| PSA level | |||

| <4 | 223 (91.4) | 108 (17.0) | <0.0001 |

| 4–10 | 17 (7.0) | 424 (66.6) | |

| >10 | 4 (1.6) | 105 (16.5) | |

| Path tumor stagea | |||

| <T3 | 339 (79.8) | ||

| ≥T3 | 86 (20.2) | ||

| Gleason 4–6 | — | 279 (43.9) | |

| 7 | 254 (39.9) | ||

| 8–10 | 97 (15.3) |

Surgical cases only.

P-value significant at <0.05.

SRD5A2.V 89 LPolymorphism

Among all study subjects, the SRD5A2 VV genotype was most common (48.4%), followed by the VL (42.2%), and LL (9.4%) genotypes. The overall difference in the frequency of the L allele by race approached significance (AA 48.3% vs. W 54.3%, P = 0.08) and African-American men were significantly less likely to carry the LL genotype as compared to Caucasian men (6.8% vs. 11.5%, P = 0.02). Among controls, the SRD5A2 V89L polymorphism was in Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium. Overall and by race, as Table II indicates, there were no statistically important differences in risk of prostate cancer between cases and controls for the SRD5A2 V89L genotype alone.

TABLE II.

Association Between SRD5A2 and HSD3B2 Genotype Frequencies and Risk of Prostate Cancer

| SRD5A2 genotype | Controls n (%) | Cases n (%) | OR (CI)a | P-value* |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| African Americans | ||||

| VV | 54 (50.9) | 143 (52.0) | Reference | |

| VL | 45 (42.5) | 113 (41.1) | 0.89 (0.55–1.44) | 0.64 |

| LL | 7 (6.6) | 19 (6.9) | 0.99 (0.62–1.59) | 0.97 |

| Total | 106 (100.0) | 275 (100.0) | ||

| Caucasians | ||||

| VV | 66 (48.5) | 160 (44.7) | Reference | |

| VL | 53 (39.0) | 158 (44.1) | 1.33 (0.86–2.06) | 0.20 |

| LL | 17 (12.5) | 40 (11.2) | 1.01 (0.73–1.40) | 0.96 |

| Total | 136 (100.0) | 358 (100.0) | ||

| All subjects | ||||

| VV | 120 (49.6) | 303 (47.9) | Reference | |

| VL | 98 (40.5) | 271 (42.8) | 1.11 (0.81–1.53) | 0.51 |

| LL | 24 (9.9) | 59 (9.3) | 0.98 (0.76–1.28) | 0.92 |

| Total | 242 (100.0) | 633 (100.0) | ||

|

| ||||

| HSD3B2 genotype | Controls n (%) | Cases n (%) | OR (CI)a | P-value* |

|

| ||||

| African Americans | ||||

| Long/long | 98 (93.3) | 247 (90.1) | Reference | |

| Long/short or short/short | 7 (6.7) | 27 (9.9) | 1.50 (0.62–3.6) | 0.37 |

| Totalb | 105 (100.0) | 274 (100.0) | ||

| Caucasians | ||||

| Long/long | 131 (96.3) | 325 (90.8) | Reference | |

| Long/short or short/short | 5 (3.7) | 33 (9.2) | 2.80 (1.05–7.43) | 0.04 |

| Total | 136 (100.0) | 358 (100.0) | ||

| All subjects | ||||

| Long/long | 229 (95.0) | 572 (90.5) | Reference | |

| Long/short or short/short | 12 (5.0) | 60 (9.5) | 2.07 (1.08–3.95) | 0.03 |

| Total | 241 (100%) | 632 (100%) | ||

Odds Ratios adjusted for race (all subjects), age, family history, BPH, BMI and smoking history, CI 95%.

After multiple attempts, two African Americans could not be genotyped for the HSD3B2 polymorphism.

P value significant at <0.05.

HSD3B2 Length Polymorphism

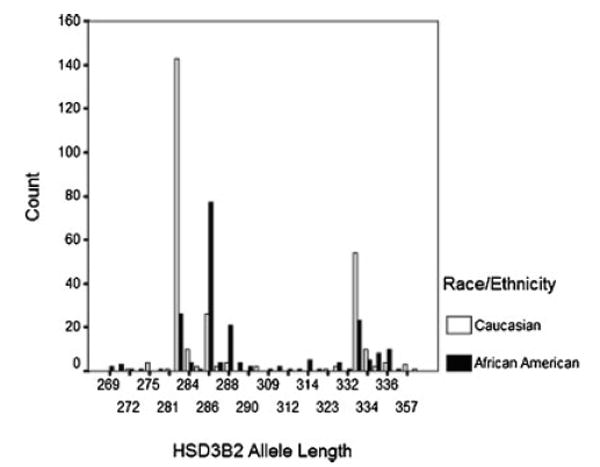

A total of 48 HSD3B2 alleles ranging in length from 213 to 375 were genotyped in our study subjects. Genotype frequencies in controls were in Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium. The 283 bp length allele accounted for 35.3% of all alleles typed. Alleles 286 bp (20.8%) and 333 bp (16.0%) were the next most common alleles with all other alleles occurring at frequencies of less than 10%. Stratification by race showed that in African American and Caucasian controls, the most common alleles occurred at very different frequencies (HSD3B2 283 bp: African American 12.4% vs. Caucasian 52.6%; HSD3B2 286 bp: African American 36.7% vs. Caucasian 9.6%, HSD3B2 333 bp: 11.0% vs. Caucasian 19.9%; Fig. 1). Polynomial regression in African Americans and Caucasians as well as in combined analyses indicated that the relationship between this polymorphism and outcome was not linear. A sensitivity analysis at various binary cut points showed that dichotomizing HSD3B2 allele lengths into long and short risk alleles at the 283 bp cut point resulted in the formation of risk groups that best differentiated cases from controls. Therefore, we chose to simplify the analysis of this polymorphism by subdividing alleles into two groups of “short” (<283 bp) and “long” (≥283 bp) alleles.

Fig. 1.

HSD3B2 repeat polymorphism allele distribution among controls by race.

Race-stratified and overall results for the HSD3B2 polymorphism are shown in Table II. Using the long/long genotype as the referent, the genotypes including short alleles (long/short and short/short) were associated with an elevated risk for prostate cancer in Caucasians (OR 2.80, CI 1.05–7.43, P = 0.04) and among all subjects (OR 2.07, CI 1.08–3.95, P = 0.03). Risk was also elevated but not significant in African Americans carrying at least one HSD3B2 (TG)n,(TA)n,(CA)n short allele (OR 1.50, CI .62–3.6, P = 0.37).

SRD5A2 and HSD3B2:Prostate Cancer Risk and Aggressiveness

Table III shows the risk of prostate cancer associated with the HSD3B2 polymorphism after stratification by SRD5A2 V89L status. Elevated risk for prostate cancer associated with the long/short or short/short HSD3B2 genotype were observed for both SRD5A2 genotypic strata, but within the stratum defined by individuals with either the SRD5A2 VL or LL genotypes prostate cancer risk associated with the long/short or short/short HSD3B2 genotype in Caucasians was elevated (Table II). Risk estimates for Caucasians associated with the HSD3B2 polymorphism were greater than African Americans even after adjusting for age, family history of prostate cancer, BPH, BMI, and smoking.

TABLE III.

Association Between SRD5A2 and HSD3B2 Haplotype and Prostate Cancer and Aggressiveness

| SRD5A2 genotype | HSD3B2 genotype | Controls n (%) | All cases n(%) | OR (CI)a | P-value** | Case Gleason 4–6a OR (CI) | P-value** | Case Gleason 8–10a OR (CI) | P-value** |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VV | African Americans | ||||||||

| Long/long | 49 (92.5) | 129 (90.8) | Reference | Reference | Reference | ||||

| Long/short or short/short | 4 (7.5) | 13 (9.2) | 1.62 (0.48–5.48) | 0.43 | 1.99 (0.46–8.65) | 0.36 | 1.50 (0.41–5.44) | 0.54 | |

| Caucasians | |||||||||

| Long/long | 62 (93.9) | 146 (91.3) | Reference | Reference | Reference | ||||

| Long/short or short/short | 4 (6.1) | 14 (8.8) | 1.66 (0.50–5.44) | 0.40 | 1.49 (0.38–5.74) | 0.56 | 1.86 (0.49–7.02) | 0.36 | |

| All subjects | |||||||||

| Long/long | 111 (93.3) | 275 (91.1) | Reference | Reference | Reference | ||||

| Long/short or short/short | 8 (6.7) | 27 (8.9) | 1.62 (0.70–3.76) | 0.26 | 1.62 (0.62–4.27) | 0.33 | 1.65 (0.66–4.15) | 0.29 | |

| VL or LL | African Americans | ||||||||

| Long/long | 49 (94.2) | 118 (89.4) | Reference | Reference | Reference | ||||

| Long/short or short/short | 3 (5.8) | 14 (10.6) | 1.64 (0.42–6.33) | 0.48 | 2.05 (0.43–9.71) | 0.37 | 1.57 (0.36–6.77) | 0.55 | |

| Caucasians | |||||||||

| Long/long | 69 (98.6) | 179 (90.4) | Reference | Reference | Reference | ||||

| Long/short or short/short | 1 (1.4) | 19 (9.6) | 7.42 (0.96–57.4) | 0.06 | 4.37 (0.48–39.7) | 0.19 | 10.18 (1.29–80.48) | 0.03 | |

| All subjects | |||||||||

| Long/long | 118 (96.7) | 297 (90.0) | Reference | Reference | Reference | ||||

| Long/short or short/short | 4 (3.3) | 33 (10.0) | 3.16 (1.08–9.25) | 0.04 | 2.60 (0.78–8.69) | 0.12 | 3.82 (1.27–11.50) | 0.02 |

Odds ratios adjusted for race (all subjects), age, family history, BPH, BMI, smoking, 95% CI.

P-value significant at <0.05.

We also dichotomized cases based on aggressive disease (Gleason sum ≥7) to assess whether clinical heterogeneity among cases revealed any additional genetic risk (Table III). ORs were significantly increased for aggressive disease within the subset of Caucasians with the SRD5A2 89L allele (OR 10.2, CI 1.29–80.5, P = 0.03) and among all subjects (OR 3.82, CI 1.27–11.50, P = 0.02) even after adjustment for covariates. Overall, stratifying by either the SRD5A2 V89L polymorphism or aggressive disease did not appear to affect prostate cancer risk estimates for the HSD3B2 intron 3 short allele in African Americans.

DISCUSSION

This study sought to elucidate potential independent and joint effects of two polymorphisms in the androgen metabolism pathway, SRD5A2 V89L and a (TG)n,(TA)n,(CA)n repeat polymorphism in the third intron of the HSD3B2 gene, with regard to prostate cancer risk and aggressiveness. Our findings suggest that both of these polymorphisms differ in genotype frequency by race, and that the HSD3B2 length polymorphism independently and in conjunction with the SRD5A2 V89L polymorphism is associated with elevated prostate cancer risk and potentially prostate cancer aggressiveness in all subjects and among Caucasians. The latter result, in particular, must be viewed cautiously since this HSD3B2 polymorphism has not been previously reported in terms of prostate cancer risk and subject numbers upon which this result was based were very small.

Lachance et al. [21] first reported the HSD3B2 intron 3 (TG)n,(TA)n,(CA)n repeat and noted hairpin-like structures associated with the polymorphism. These secondary structures have the potential to vary or terminate the rate of transcription of the enzyme [23] or potentially cause alternative spliced forms of mRNA resulting in truncated or unstable proteins [24]. In fact, three alternative spliced forms of the transcribed pre-mRNA of HSD3B2 are known to exist (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/asd/), with intron 3 excluded from the two shorter transcribed mRNAs that also contain different coding sequences that might alter HSD3B2 activity and therefore may degrade DHT at varying rates. In terms of which alleles are more likely to form hairpins, previous studies have shown that longer allele length is associated with hairpin structures that are more stable, but this stability is achieved at a certain maximum length such that alleles longer than this threshold offer no further increased stability for the hairpin structure [35,36]. This would support the conservative decision we made to divide the HSD3B2 length polymorphism into “long” and “short” categories. In addition alternative splicing of pre-mRNA increases genetic diversity [37] and therefore it follows that an allele length that is both long enough to promote alternative spliced forms of the HSD3B2 protein while at the same time short enough to ensure sufficient copies of the full functional version of the protein are made may be highly selected for.

In our subjects, we found that the short allele (<283 bp) of the HSD3B2 intron 3 polymorphism was associated with increased risk of prostate cancer and potentially aggressiveness of disease. Carriage of HSD3B2 short alleles may predispose toward having more copies of the full length HSD3B2 protein that is more active, indirectly producing larger quantities of testosterone and degrading DHT more rapidly resulting in an imbalance of serum testosterone to DHT. Higher serum testosterone to DHT ratios have been associated with increased risk of prostate cancer in some studies [25-27]. But in primary prostate cancer cells DHT levels have been reported to be higher in tumor than adjacent normal cells [38]. If the HSD3B2 (TG)n,(TA)n,(CA)n polymorphism does have an impact on gene expression, the resulting impact on testosterone and DHT levels may or may not be equivalent. First, DHT is metabolized through multiple pathways most of which are reversible reactions, including the conversion of DHT to 3 β-androstanediol by HSD3B2. It is possible that over expression of HSD3B2 could have a greater effect on the rate of anabolism of DHT than the rate of catabolism of DHT. Secondly, Ji et al. [38] have reported on two proteins also involved in the metabolism of DHT, AKR1C1 and AKR1C2. Although AKR1C1, which is associated with the HSD3B pathway of DHT metabolism, is expressed at higher levels than AKR1C2, AKR1C2 had more influence on DHT-dependent androgen receptor reporter activity. In prostate cancer, the HSD3B2 metabolic pathway of DHT, therefore, may be out competed by other metabolic pathways. The higher expression yet lower affect of the AK1C1 protein would suggest this.

In vivo and in vitro studies of the SRD5A2 V89L polymorphism have indicated reduced activity of the SRD5A2 enzyme with the leucine substitution [9-11] indicating a slower conversion rate of testosterone to DHT. In terms of prostate cancer risk, this polymorphism has shown mixed results. A meta analysis that included the review of 12 studies was conducted by Ntais et al. [8] and indicated no overall change in risk with the L variant. Since this analysis Forrest et al. [39] in a case-control analysis using controls from the EPIC study reported increased risk for prostate cancer associated with the LL genotype and Cicek et al. [13] found increased risk was primarily driven by men diagnosed at younger age or with more aggressive disease. This polymorphism has also been associated with progression of disease [40]. Stanbrough et al. [41] found increased levels of HSD3B2 activity and decreased levels of SRD5A2 (approximately 50%) in metastatic androgen-independent prostate cancer tumors. Others have also shown lower levels of SRD5A2 in prostate tissue [42-44]. The increased prostate cancer risk we found associated with Caucasian carriers of the HSD3B2 intron 3 short allele and SRD5A2 89L allele that may predispose to higher levels of HSD3B2 but less active SRD5A2 enzyme are in line with these findings. Among African Americans, risk associated with the HSD3B2 intron 3 short allele was elevated but not significant and stratification by the SRD5A2 V89L polymorphism appeared not to impact risk. Interestingly, the most common HSD3B2 intron 3 repeat allele length was different in Caucasians (283 bp) and African Americans (286 bp) suggesting that some evolutionary advantage selecting for the longer allele length in African populations may exist. In addition, the frequency of the LL genotype in our African-American sample was at the lower end of previously reported ranges [13,14,45] limiting the statistical power for testing associations of this polymorphism. The V89L polymorphism in exon 1 of the SRD5A2 gene lies at the far 3′ end of the gene and therefore is in linkage equilibrium with several other polymorphisms within the SRD5A2 gene that have been described by Reichardt et al. [46] and others [47,48]. In terms of prostate cancer risk, Loukola et al. [47] interrogated the entire SRD5A2 gene and found 25 SNPs, but only the V89L variant and another SNP in an untranslated region of the gene in strong linkage disequilibrium with the V89L variant were associated with prostate cancer. Polymorphism in HSD3B2 may be limited, with a recent sequencing study [49] finding only six SNPs. The few coding SNPs in HSD3B2 that have been reported are not polymorphic enough to be of any practical utility for testing associations with disease risk in moderately sized samples. Interestingly, while the HSD3B2 intron 3 repeat polymorphism was reported to vary significantly with race 10 years ago [22], until the current study it has never been investigated in the context of prostate cancer risk.

Although our study sample size was relatively large and included a large proportion of African-American subjects, the original study design included only one age-race frequency matched control to every three cases limiting statistical power for stratified case-control comparisons. The controls were representative of the population from which the cases were sampled and controlling for family history and BPH, two factors which differed by case-control status, showed no important difference from crude odds ratios. We also compared mean rank PSA levels for all genotypes and haplotypes (Tables II and III) using the Kruskal–Wallace test, as genetic variations in genes that control androgens may affect PSA levels and detection of disease. We found no significant differences in PSA levels between groups, reducing the possibility that detection bias lead to our observations. In addition, the frequency of high Gleason scores in our subjects may have contributed to our findings on aggressive disease, as nearly 65% of our case subjects underwent prostatectomy. Gleason scores have been shown to increase from biopsy in prostatectomy cases [50] and the higher use of radical prostatectomy at our institution may have provided higher than expected frequencies of aggressive cases. None of the gene–gene interactions we tested were statistically significant, nonetheless interaction odds ratios in Caucasians were greatly elevated suggesting a possible synergy of effect between HSD3B2 and SRD5A2 in the prostate carcinogens is pathway.

To our knowledge, our study represents the first report of an association between the HSD3B2 (TG)n,(TA)n,(CA)n polymorphism with risk of prostate cancer. Risk and aggressiveness of disease among all subjects and in Caucasians was associated with short allele genotypes of the HSD3B2 (TG)n,(TA)n,(CA)n and the SRD5A2 V89L polymorphism may modify this risk. Further study of this repeat polymorphism, independently and in conjunction with other genetic polymorphism within the androgen pathway is clearly warranted.

Acknowledgments

Grant sponsor: National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences; Grant number: R01 ES11126.

References

- 1.American Cancer Society. Cancer facts and figures 2006. Atlanta: American Cancer Society; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Platz EA, Giovannucci E. The epidemiology of sex steroid hormones and their signaling and metabolic pathways in the etiology of prostate cancer. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2004:237–253. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2004.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hsing AW, Reichardt JKV, Stanczyk FZ. Hormones and prostate cancer: Current perspectives and future directions. Prostate. 2002;52:213–235. doi: 10.1002/pros.10108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bosland MC. Chapter 2: The role of steroid hormones in prostate carcinogenesis. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 2000:39–66. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jncimonographs.a024244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Labrie F, Sugimoto Y, Luu-The V, Simard J, Lachance Y, Bachvarov D, Leblanc G, Durocher F, Paquet N. Structure of human type II 5 alpha-reductase gene. Endocrinology. 1992;131:1571–1573. doi: 10.1210/endo.131.3.1505484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Andriole G, Brushovsky N, Chung LWK, Matsumoto AM, Rittmaster R, Roehrborn C, Russell D, Tindall D. Dihydrotestosterone and the prostate: The scientific rationale for 5αareductase inhibitors in the treatment of benign prostatic hyperplasia. J Urol. 2004;172:1399–1403. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000139539.94828.29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Andriole G, Bostwick D, Civantos F, Epstein J, Lucia MS, McConnell J, Roehnborn CG. The effects of a 5a-reductase inhibitors on the natural history, detection and grading of prostate cancer’ current state of knowledge. J Urol. 2005;174:2098–2104. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000181216.71605.38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ntais C, Polycarpou A, Ioanndis JPA. SRD5A2 gene polymorphisms and the risk of prostate cancer: A meta analysis. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2003;12:618–624. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Makridakis N, Ross RK, Pike MC, Chang L, Stanczyk FZ, Kolonel LN, Shi CY, Yu MC, Henderson BE, Reichardt JK. A prevalent missense substitution that modulates activity of prostatic steroid 5alpha-reductase. Cancer Res. 1997;57:1020–1022. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Febbo PG, Kantoff PW, Platz EA, Casey D, Batter S, Giovannucci E, Hennekens CH, Stampfer MJ. The V89L polymorphism in the 5{{alpha}}-reductase type 2 gene and risk of prostate cancer. Cancer Res. 1999;59:5878–5881. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Allen NE, Forrest MS, Key TJ. The association between polymorphisms in the CYP17 and 5{{alpha}}-reductase (SRD5A2) genes and serum androgen concentrations in men. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2001;10:185–189. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Roberts RO, Bergstralh EJ, Farmer SA, Jacobson DJ, McGree ME, Hebbring SJ, Cunningham JM, Anderson SA, Thibodeau SN, Lieber MM, Jacobsen SJ. Polymorphisms in the 5a reductase type 2 gene and urologica measures of BPH. Prostate. 2005;62:380–387. doi: 10.1002/pros.20142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cicek MS, Conti DV, Curran A, Neville PJ, Paris PL, Casey G, Witte JS. Association of prostate cancer risk and aggressiveness to androgen pathway genes: SRD5A2, CYP17, and the AR. Prostate. 2004;59:69–76. doi: 10.1002/pros.10358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zeigler-Johnson CM, Walker AH, Mancke B, Spangler E, Jalloh M, McBride S, Deitz A, Malkowicz SB, Ofori-Adjei D, Gueye SM, Rebbeck TR. Ethnic differences in the frequency of prostate cancer susceptibility alleles at SRD5A2 and CYP3A4. Hum Hered. 2002;54:13–21. doi: 10.1159/000066695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Berube D, Luu TV, Lachance Y, Gagne R, Labrie F. Assignment of the human 3 beta-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase gene (HSDB3) to the p13 band of chromosome 1. Cytogenet Cell Genet. 1989;52:199–200. doi: 10.1159/000132878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ozen M, Hopwood VL, Balbay MD, Johnston DA, Babaian RJ, Logothetis CJ, von Eschenbach AC, Pathak S. Correlation of non-random chromosomal aberrations in lymphocytes of prostate cancer patients with specific clinical parameters. Int J Oncol. 2000;17:113–117. doi: 10.3892/ijo.17.1.113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Xu J, Zheng SL, Chang B, Smith JR, Carpten JD, Stine OC, Isaacs SD, Wiley KE, Henning L, Ewing C, Bujnovszky P, Bleeker ER, Walsh PC, Trent JM, Meyers DA, Isaacs WB. Linkage of prostate cancer susceptibility loci to chromosome 1. Hum Genet. 2001;108:335–345. doi: 10.1007/s004390100488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chang B, Zheng SL, Hawkins GA, Isaacs SD, Wiley KE, Turner A, Carpten JD, Bleecker ER, Walsh PC, Trent JM, Meyers DA, Isaacs WB, Xu J. Joint effect of HSD3B1 and HSD3B2 genes is associated with heredity and sporadic prostate cancer suseptibility. Cancer Res. 2002:1784–1789. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Slager SL, Zarfas KE, Brown WM, Lange EM, McDonnell SK, Wojno KJ, Cooney KA. Genome-wide linkage scan for prostate cancer aggressiveness loci using families from the University of Michigan Prostate Cancer Genetics Project. Prostate. 2006;66:173–179. doi: 10.1002/pros.20332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lachance Y, Luu-The V, Labrie C, Simard J, Dumont M, de LY, Guerin S, Leblanc G, Labrie F. Characterization of human 3 beta-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase/delta 5-delta 4-isomerase gene and its expression in mammalian cells. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:3551. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lachance Y, Luu-The V, Verreault H, Dumont M, Rheaume E, Leblanc G, Labrie F. Structure of the human type II 3 beta-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase/delta 5-delta 4 isomerase (3 beta-HSD) gene: Adrenal and gonadal specificity. DNA Cell Biol. 1991;10:701–711. doi: 10.1089/dna.1991.10.701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Devgan SA, Henderson BE, Yu MC, Sui CY, Pike MC, Ross RK, Reichardt JKV. Genetic variation of 3β hyroxysteroid dehydrogenase type II in three racial/ethnic groups: Implications for prostate cancer risk. Prostate. 1997;33:9–12. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0045(19970915)33:1<9::aid-pros2>3.0.co;2-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ryan T, Chamberlin MJ. Transcription analyses with heteroduplex trp attenuator templates indicate that the transcript stem and loop structure serves as the termination signal. J Biol Chem. 1983;258:4690–4693. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lian Y, Garner HR. Evidence for the regulation of alternative splicing via complementary DNA sequence repeats. Bioinformatics. 2005;21:1358–1364. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Comstock GW, Gordon GB, Hsing AW. The relationship of serum dehydroepiandrosterone and its sulfate to subsequent cancer of the prostate. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 1993;2:219–221. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dorgan JF, Albanes D, Virtamo J, Heinonen OP, Chandler DW, Galmarini M, McShane LM, Barrett MJ, Tangrea J, Taylor PR. Relationships of serum androgens and estrogens to prostate cancer risk: Results from a prospective study in Finland. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 1998;7:1069–1074. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gann PH, Hennekens CH, Ma J, Longcope C, Stampfer MJ. Prospective study of sex hormone levels and risk of prostate cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1996;88:1118–1126. doi: 10.1093/jnci/88.16.1118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Umbach DM, Weinberg CR. Designing and analysing case-control studies to exploit independence of genotype and exposure. Stat Med. 1997;16:1731–1743. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0258(19970815)16:15<1731::aid-sim595>3.0.co;2-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Thigpen AE, Davis DL, Milatovich A, Mendonca BB, Imperato-McGinley J, Griffin JE, Francke U, Wilson JD, Russell DW. Molecular genetics of steroid 5 alpha-reductase 2 deficiency. J Clin Invest. 1992;90:799–809. doi: 10.1172/JCI115954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Verreault H, Dufort I, Simard J, Labrie F, Luu-The V. Dinuleotice repeat polymorphisms in the HSD3B2 gene. Hum Mol Genet. 1994;3 doi: 10.1093/hmg/3.2.384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hope A. A simplified monte carlo significance test procedure. J Roy Stat Soc Ser B. 1968;30:582–598. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Salam MT, Ursin G, Skinner EC, Dessissa T, Reichardt JK. Associations between polymorphisms in the steroid 5-alpha reductase type II (SRD5A2) gene and benign prostatic hyperplasia and prostate cancer. Urol Oncol. 2005;23:246–253. doi: 10.1016/j.urolonc.2004.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Li Z, Habuchi T, Mitsumori K, Kamoto T, Kinoshitu H, Segawa T, Ogawa O, Kato T. Association of V89L SRD5A2 polymorphism with prostate cancer development in a Japanese population. J Urol. 2003;169:2378–2381. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000056152.57018.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Field AE, Colditz GA, Willett WC, Longcope C, McKinlay JB. The relation of smoking, age, relative weight, and dietary intake to serum adrenal steroids, sex hormones, and sex hormone-binding globulin in middle-aged men. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1994;79:1310–1316. doi: 10.1210/jcem.79.5.7962322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Paiva AM, Sheardy RD. The influence of sequence context and length on the kinetics of DNA duplex formation from complementary hairpins possessing (CNG) repeats. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:5581–5585. doi: 10.1021/ja043783n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Paiva AM, Sheardy RD. Influence of sequence context and length on the structure and stability of triplet repeat DNA oligomers. Biochemistry. 2004;43:14218–14227. doi: 10.1021/bi0494368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Black DL. Mechanisms of alternative pre-messenger RNA splicing. Annu Rev Biochem. 2003;72:291–336. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.72.121801.161720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ji Q, Chang L, Stanczyk FZ, Ookhtens M, Sherrod A, Stolz A. Impaired dihydrotestosterone catabolism in human prostate cancer: Critical role of AKR1C2 as a pre-receptor regulator of androgen receptor signaling. Cancer Res. 2007;67:1361–1369. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-1593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Forrest MS, Edwards SM, Houlston R, Kote-Jarai Z, Key T, Allen N, Knowles MA, Turner F, Ardern-Jones A, Murkin A, Williams S, Oram R, Bishop DT, Eeles RA. Association between hormonal genetic polymorphisms and early-onset prostate cancer. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2005;8:95–102. doi: 10.1038/sj.pcan.4500785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shibata A, Garcia MI, Cheng I, Stamey TA, McNeal JE, Brooks JD, Henderson S, Yemoto CE, Peehl DM. Polymorphisms in the androgen receptor and type II 5 alpha-reductase genes and prostate cancer prognosis. Prostate. 2002;52:269–278. doi: 10.1002/pros.10119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Stanbrough M, Bubley GJ, Ross K, Golub TR, Rubin MA, Penning TM, Febbo PG, Balk SP. Increased expression of genes converting adrenal androgens to testosterone in androgen-independent prostate cancer. Cancer Res. 2006;5:2815–2825. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-4000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Luo J, Dunn TA, Ewing CM, Walsh PC, Isaacs WB. Decreased gene expression of steroid 5 alpha-reductase 2 in human prostate cancer: Implications for finasteride therapy of prostate carcinoma. Prostate. 2003;57:134–139. doi: 10.1002/pros.10284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Thomas LN, Lazier CB, Gupta R, Norman RW, Troyer DA, O’Brien SP, Rittmaster RS. Differential alterations in 5alpha-reductase type 1 and type 2 levels during development and progression of prostate cancer. Prostate. 2005;63:231–239. doi: 10.1002/pros.20188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Titus MA, Gregory CW, Ford OH, III, Schell MJ, Maygarden SJ, Mohler JL. Steroid 5alpha-reductase isozymes I and II in recurrent prostate cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11:4365–4371. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-0738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pearce CL, Makridakis NM, Ross RK, Pike MC, Kolonel LN, Henderson BE, Reichardt JK. Steroid 5-alpha reductase type II V89L substitution is not associated with risk of prostate cancer in a multiethnic population study. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2002;11:417–418. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Reichardt JK, Makridakis N, Henderson BE, Yu MC, Pike MC, Ross RK. Genetic variability of the human SRD5A2 gene: Implications for prostate cancer risk. Cancer Res. 1995;55:3973–3975. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Loukola A, Chadha M, Penn SG, Rank D, Conti DV, Thompson D, Cicek M, Love B, Bivolarevic V, Yang Q, Jiang Y, Hanzel DK, Dains K, Paris PL, Casey G, Witte JS. Comprehensive evaluation of the association between prostate cancer and genotypes/haplotypes in CYP17A1, CYP3A4, and SRD5A2. Eur J Hum Genet. 2004;12:321–332. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejhg.5201101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wang Y, Li Q, Xu J, Liu Q, Wang W, Lin Y, Ma F, Chen T, Li S, Shen Y. Mutation analysis of five candidate genes in Chinese patients with hypospadias. Eur J Hum Genet. 2004;12:706–712. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejhg.5201232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Chang BL, Zheng SL, Hawkins GA, Isaacs SD, Wiley KE, Turner A, Carpten JD, Bleecker ER, Walsh PC, Trent JM, Meyers DA, Isaacs WB, Xu J. Joint effect of HSD3B1 and HSD3B2 genes is associated with hereditary and sporadic prostate cancer susceptibility. Cancer Res. 2002;62:1784–1789. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Freedland SJ, Kane CJ, Amling CL, Aronson WJ, Terris MK, Presti JC., Jr Upgrading and downgrading of prostate needle biopsy specimens: Risk factors and clinical implications. Urology. 2007;69:495–499. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2006.10.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]