Abstract

To follow the dynamics of nuclear pore distribution in living yeast cells, we have generated fusion proteins between the green fluorescent protein (GFP) and the yeast nucleoporins Nup49p and Nup133p. In nup133− dividing cells that display a constitutive nuclear pore clustering, in vivo analysis of GFP-Nup49p localization revealed changes in the distribution of nuclear pore complex (NPC) clusters. Furthermore, upon induction of Nup133p expression in a GAL-nup133 strain, a progressive fragmentation of the NPC aggregates was observed that in turn led to a wild-type nuclear pore distribution. To try to uncouple Nup133p- induced NPC redistribution from successive nuclear divisions and nuclear pore biogenesis, we devised an assay based on the formation of heterokaryons between nup133− mutants and cells either expressing or overexpressing Nup133p. Under these conditions, the use of GFP-Nup133p and GFP-Nup49p fusion proteins revealed that Nup133p can be rapidly targeted to the clustered nuclear pores, where its amino-terminal domain is required to promote the redistribution of preexisting NPCs.

Bidirectional exchange of molecules between the cytoplasm and the nucleus in eukaryotic cells is accomplished through nuclear pore complexes (NPCs)1 (Forbes, 1992; Fabre and Hurt, 1994). Anchored in the nuclear envelope, the NPCs of higher eukaryotes are macromolecular structures with an estimated molecular mass of 125 megadaltons (MD) (Reichelt et al., 1990). Their basic architecture, including a characteristic eightfold symmetry, is shared by the smaller 66 MD yeast NPC (Allen and Douglas, 1989; Rout and Blobel, 1993).

Several approaches, including immunological screens, genetic screens, and improved purification procedures of NPCs, have led to the identification of ∼20 nuclear pore proteins (called nucleoporins) from amongst the 50–100 nucleoporins that are believed to exist in Saccharomyces cerevisiae (for reviews see Rout and Wente, 1994; Doye and Hurt, 1995). Their implication in various NPC functions has been suggested by phenotypic analysis of conditional lethal mutants. In particular, several yeast nucleoporin mutants display an intranuclear accumulation of poly(A)+ RNA at 37°C (Wente and Blobel, 1993; Bogerd et al., 1994; Doye et al., 1994; Fabre et al., 1994; Aitchison et al., 1995a ; Gorsch et al., 1995; Grandi et al., 1995; Heath et al., 1995; Hurwitz and Blobel, 1995; Li et al., 1995; Goldstein et al., 1996; Siniossoglou et al., 1996). Similarly, overexpression of the human nucleoporin Nup153 was recently shown to inhibit mRNA trafficking (Bastos et al., 1996). Among the yeast nucleoporin mutants defective for mRNA export, nup84, nup85, nup120, nup133, nup145, and nup159 mutants all display a constitutive NPC clustering that is sometimes associated with alterations in the structure of the nuclear envelope (Doye et al., 1994; Wente and Blobel, 1994; Aitchison et al., 1995a ; Gorsch et al., 1995; Heath et al., 1995; Li et al., 1995; Pemberton et al., 1995; Goldstein et al., 1996; Siniossoglou et al., 1996). However, in contrast to the phenotype observed in the nup116 null mutant in which a nuclear envelope seal over the NPC was suggested to directly inhibit nucleocytoplasmic traffic (Wente and Blobel, 1993), NPC clustering and mRNA export defects can be dissociated; in these nucleoporin mutants, the clustered pores are competent for poly(A)+ RNA export at the permissive temperature. Moreover, rat7-1/nup159-1 mutant cells recover a nearly normal NPC distribution within 1 h at 37°C, although cessation of mRNA export occurs at this restrictive temperature (Gorsch et al., 1995). Finally, a truncation of the amino-terminal domain of Nup133p that restores normal RNA export at 37°C does not correct the nuclear pore distribution defect (Doye et al., 1994).

Spatial heterogeneity in NPC distribution, including extreme situations consisting of large NPC-devoid regions of the nuclear envelope together with densely packed NPC clusters, have been described since the late 60s (for review see Franke and Scheer, 1974). In particular, changes in pore distribution within a given cell type have been reported both in yeast and higher eukaryotes. For example, pore clusters were observed in stationary yeast cultures, but not in exponentially growing cells (Moor and Mühlethaler, 1963). Similarly, the definite pore clustering observed in early G1 HeLa cells or G0 human lymphocytes disappears when cells enter S phase (Markovics et al., 1974). Besides, Severs et al. (1976) reported that the progressive fragmentation of a large vacuole during G0 and the beginning of S phase is associated with changes in the size and position of pore-free areas within the yeast nuclear envelope. Dramatic changes in NPC distribution have also been associated with the nuclear shaping and chromatin condensation processes during spermiogenesis (Rattner and Brinkley, 1971) and during the active phase of apoptosis (Falcieri et al., 1994).

So far, two mechanisms that may induce changes in nuclear pore distribution have been proposed. Firstly, nuclear pores and/or nuclear membranes could be preferentially synthesized and degraded in specific areas of the nuclear envelope. Alternatively, changes in nuclear pore arrangements may result from the lateral mobility of preexisting nuclear pore complexes in the nuclear envelope (discussed in Markovics et al., 1974; Severs et al., 1976). Until recently, it was not possible to distinguish between these two hypotheses because the dynamic distribution of pores could not be directly observed. However, the recent advent of green fluorescent protein (GFP) technology now enables in vivo analysis of protein distribution. GFP and brighter GFP variants engineered by mutational analysis have been successfully used as reporters of gene expression, tracers of cell lineage, and as fusion tags to monitor protein localization in various organisms (for reviews see Cubitt et al., 1995; Prasher, 1995). In addition, GFPchimeras have been used to monitor subcellular events in living cells such as separation of the spindle pole bodies or movements of actin patches in yeast (Kahana et al., 1995; Doyle and Botstein, 1996; Waddle et al., 1996).

In this report, we used nucleoporins fused with GFP to monitor NPC distribution in vivo. The NUP133-disrupted (nup133−) strain that displays a constitutive NPC clustering (Doye et al., 1994; Li et al., 1995) enabled us to follow two aspects of NPC dynamics: the movements of NPC clusters in dividing nup133− cells and the redistribution of the clustered NPCs upon induction of Nup133p expression in a GAL-nup133 strain. To further characterize Nup133pinduced NPC redistribution, we developed an assay based on the formation of heterokaryons between nup133− mutants and cells expressing or overexpressing Nup133p. Our results show that Nup133p can be targeted to the clustered NPC and thereby promotes their rapid redistribution.

Materials and Methods

Plasmid and Strain Construction

DNA manipulations, including restriction analysis, fill-in reactions with Klenow fragment, and ligations, were performed essentially as described by Maniatis et al. (1982). Strains used in this study are listed in Table I. Yeast strains were grown in rich media (1% yeast extract, 2% bactopeptone, 30 mg/ml adenine) with either 2% dextrose (YPDA) or 2% galactose (YPGalA), or in synthetic complete media (SDC and SGalC) lacking specific amino acids (CSM medium; Bio 101, La Jolla, CA). Plasmid transformation, gene disruption, sporulation of diploid cells, and tetrad analysis were performed as described by Wimmer et al. (1992). To minimize autofluorescence, all ade2− ADE3 strains were transformed with plasmid pASZ11 containing ADE2 marker (Stotz and Linder, 1990).

Table I.

Yeast Strains

| Strain | Genotype | |

|---|---|---|

| RS453a | Mata ade2 his3 leu2 trp1 ura3. | |

| VD1R | Matα ade2 ade3 his3 leu2 lys2 ura3 nup49::TRP1 | |

| (pCH1122-ADE3-URA3-NUP49) | ||

| nup 133− α | Matα ade2 his3 leu2 trp1 ura3 nup133::HIS3 | |

| nup 133− a | Mata ade2 his3 leu2 trp1 ura3 nup133::HIS3 | |

| nup85− a | Mata ade2 his3 leu2 trp1 ura3 nup85::HIS3 | |

| BMA411 | Mata/Matα ade2/ade2 his3/his3 leu2/leu2 | |

| ura3/ura3 Δtrp1/Δtrp1. | ||

| GAL-nup133 | Matα ade2 his3 leu2 ura3 Δtrp1 | |

| TRP1-GAL10::nup133 | ||

| kar1-1 (049 EY93) | Mata his4-34 leu2-3112 ura3-53 kar1-1 | |

| nup133− kar1-1 | Mata his4-34 leu2-3112 ura3-53 kar1-1 | |

| nup133::URA3 |

To localize nucleoporins in vivo, a GFP S65T/V163A variant (Kahana and Silver, 1996) was used to tag Nup49p and Nup133p. Since the wildtype allele of GFP has not been used in this study, this GFP variant will be referred to as GFP in the manuscript.

The GFP-NUP49 fusion gene was constructed as previously described for ProtA-NUP49 (Wimmer et al., 1992). Briefly, an NheI/XbaI fragment encoding GFP was obtained by PCR and fused in frame to the coding sequence of NUP49 at the unique NheI site, thereby keeping the authentic NUP49 promotor. The fusion gene was inserted into a pUN100-LEU2 plasmid (Elledge and Davis, 1988).

To construct the GFP-NUP133 fusion gene, a BglII blunt-ended/EcoRI fragment encoding GFP and including a modified ATG start codon was generated by PCR. This fragment was inserted downstream of the bluntended NdeI site located at the ATG of NUP133, thereby keeping the authentic NUP133 promotor, and fused in frame to the coding sequence of NUP133 at an EcoRI site previously generated at the ATG of NUP133 (Doye et al., 1994). The GFP-nup133ΔN fusion gene was generated by removing a 600-bp NcoI fragment encoding residues 44–236 of Nup133p as previously described (Doye et al., 1994). The resulting fusion genes were inserted either in the single copy plasmid pUN100-LEU2, or in the high copy number plasmid pRS424-TRP1 (Christianson et al., 1992).

To construct the GAL-nup133 strain, a 1.7-kb fragment encoding TRP1pGAL10-HA from plasmid pTIF (generous gift from C. Cullin, CGM, CNRS, Gif-sur-Yvette, France) was amplified by PCR using the following primers: NUP133F: 5′ CACCATTTAGGAATAAGGTTTAGAGGAGCTCGAGCATACTGTTACATCCAGGCCAAGAGGGAGGGC3′ and NUP133R: 5′ ATGGGTACGCTAAGTTCCTTCCGCAAACGAAGATGTACT T T - TTTTTCACTAGCGTAGTCTGGGACGTC 3′. Underlined sequences are homologous to NUP133. The PCR product was used to transform the diploid strain BMA411 by selection on SDC-trp plates as described (BaudinBaillieu et al., 1997). TRP+ transformants were characterized for correct integration of TRP1-pGAL10-HA at the NUP133 gene locus by Southern analysis (Sherman, 1990). BMA411 diploids heterozygous for NUP133 were sporulated and tetrad analysis was performed.

For disruption of the NUP133 gene in the kar1-1 strain EY93, the URA3 gene isolated as a blunt-ended BamHI fragment from plasmid yDpU (Berben et al., 1991) was used to replace a 1.9-kb NcoI fragment of NUP133 open reading frame from plasmid pUN100-NUP133, as previously described (Doye et al., 1994). A linear nup133::URA3 fragment was excised from the recombinant plasmid and used to transform the haploid strain EY93 by selection on SDC-ura. URA+ transformants were tested for thermosensitivity, clustering of the NPCs, and lack of Nup133p on Western blots.

Microbiological Techniques

To synchronize cells, the haploid strains RS453a and nup133− a containing the pUN100-GFP-NUP49 and pASZ11 plasmids were grown at 25°C in SDC-leu -ade medium to early-log phase (0.5 OD600). 20 ng/ml of α-factor (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, MO) was added to the medium, and cells were further incubated for 2 h at 25°C. G1-arrested cells were collected by centrifugation and washed twice with SDC-leu -ade medium. Cells were further grown for 30 min in SDC-leu -ade medium at 25°C before being observed by confocal microscopy.

For mating and cytoduction experiments, ∼3 × 106 exponentially growing cells of each parent were mixed together and concentrated onto 25-mm nitrocellulose filters (type HA, 0.45 μm; Millipore Corp., Bedford, MA) using a syringe and a swinnex filter unit (Millipore Corp.). Filters were incubated on YPDA plates for 30 min to 1 h at 30°C. Cells were then resuspended by vortexing the filter in a sterile tube containing 1.5 ml of media and analyzed by fluorescence microscopy.

Fluorescence Microscopy

Indirect immunofluorescence microscopy on formaldehyde-fixed cells was performed according to Schimmang et al. (1989) with the following modifications: Yeast cells were fixed for 30 min in 3.7% formaldehyde and converted into spheroplasts using 0.2 mg/ml Zymolyase 100 T (Seikagaku Corp., Tokyo, Japan). The spheroplasts were spotted on polylysine-coated slides and left to air dry for 5 min. Slides were immersed in methanol at −20°C for 6 min and then in acetone at −20°C for 30 s. After rinsing with PBS, the slides were incubated in mAb414 antibody (Aris and Blobel, 1989) (BAbCO, Richmond, CA) diluted 1:20 in PBS containing 1% BSA, followed by Rhodamine-conjugated goat anti–mouse IgG (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, Inc., West Grove, PA) at a dilution of 1:100. For DNA staining, 1 μg/ml 4′,6′-diamindino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) was used. Fixed cells were visualized on a microscope (model DMR; Leica, Inc., Deerfield, IL) equipped with an HBO100 mercury lamp (Osram, Germany) and ×100/1.4 objective lens.

For confocal analysis, growing yeast cells were put in a Sykes Moore Chamber (Bellco, Vineland, NJ) filled with 1.2 ml SDC medium and centrifuged for 3 min at 1,500 g. Living cells were imaged at room temperature, 24–27°C, on an inverted microscope (Leica, Inc.) equipped with a ×100/1.4 objective lens, and scanning was performed with a True Confocal Scanner LEICA TCS 4D, GFP fluorescence signal being detected with the fluorescein channel. To compensate photobleaching during long-term experiments, laser power was progressively increased to yield images with similar intensities. Acquisition of eight focal planes, 0.3 to 0.8 μm apart, was routinely made. As indicated in figure legends, either individual sections or two-dimensional projection of images collected at all relevant z-axes is presented. Cells left in the chamber after an experiment proceeded to divide many times, which indicates that they were not damaged by the illumination. For kinetic analysis of heterokaryons, ∼10 independent heterokaryons were followed at various (10–25 min) intervals.

For random analysis of heterokaryons, 0.05% agarose was added to the medium, and 10 ml of cells was placed on a microscope slide and covered with a coverslip (24 × 60 μm). The cells were observed by fluorescence with a chilled CCD camera (Hamamatsu Phototonics, Hamamatsu City, Japan) on a microscope (Leica, Inc.) equipped with the following filter set: excitation, 450–490, dichroic, 510; emission, 515–560 (Filter L4; Leica, Inc.), a 100-W mercury arc lamp, and a ×100/1.4 objective lens. For these experiments, images of ∼100 individual heterokaryons were recorded.

Polyclonal Antisera, Affinity Purification of Antibodies, and Immunoblotting

Rabbit polyclonal antibodies were generated against the MS2pol-C-Nup49p and His6-N-Nup133p fusion proteins expressed in Escherichia coli. The MS2pol-C-Nup49p fusion protein contained 99 amino acids from the phage MS2 polymerase (Klinkert et al., 1988) plus the 225 COOH-terminal amino acids from the Nup49p protein. This recombinant protein was recovered from the inclusion bodies and purified by electroelution from polyacrylamide gels. The histidine-tagged amino-terminal domain of Nup133p (amino acids 14–164) expressed from the pET-HIS6 vector in E. coli BL21 strain was purified by passing the bacterial lysate over a nickel column (QIAGEN Inc., Chatsworth, CA). The MS2pol-C-Nup49p and His6-N-Nup133p fusion proteins were used for rabbit immunization as described (Hurt et al., 1988). From the obtained sera, antibodies were affinity purified against the recombinant proteins immobilized on nitrocellulose (Hurt et al., 1988).

Whole cell extracts from yeast strains were prepared by resuspending freshly harvested cells from a 40-ml culture (0.5 OD600) in 0.4 ml of 2× Laemmli buffer. 0.4 g of glass beads were added, and the samples were incubated at 100°C for 6 min with vigourous vortexing in between. The extracts were centrifuged, aliquots corresponding to 1 OD (OD600) were applied on 8 or 10% SDS-polyacrylamide gels, and separated proteins were blotted onto nitrocellulose (Schleicher and Schuell, Keene, NH). Membranes were blocked in 5% milk powder in PBS + 0.1% Tween 20, and immune sera were used at dilutions 1:500 for affinity-purified antiNup49p, 1:250 for affinity-purified anti-Nup133p, 1:2,000 for polyclonal anti-GFP (Clontech, Palo Alto, CA), and 1:5,000 for polyclonal antiNop1p. Immune detection was carried out with anti–rabbit IgGs coupled to horseradish peroxidase followed by enhanced chemiluminescence detection (Amersham International Inc., Buckinghamshire, England) according to the company's instructions.

Results

GFP-Nup49p Is Functional and Localizes to the Nuclear Pore Complexes

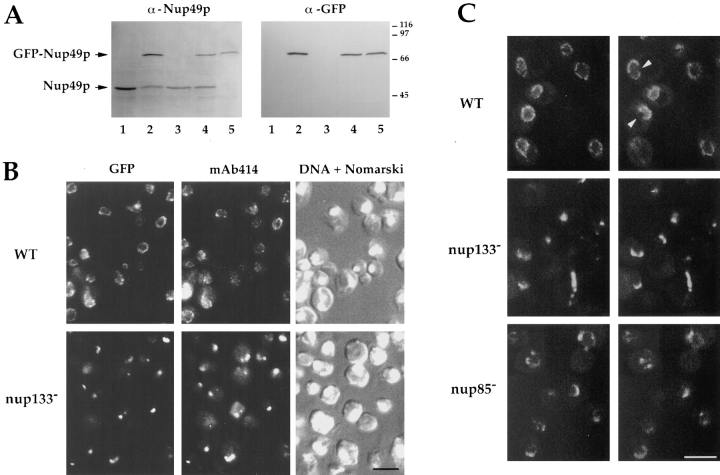

To examine in vivo the distribution of NPCs in wild-type and nucleoporin mutant cells, the yeast nuclear pore protein Nup49p was tagged with GFP. The single copy number plasmid, pUN100-GFP-NUP49, in which the GFP-NUP49 fusion gene is expressed under the authentic NUP49 promotor, was transformed into the VDIR shuffling strain disrupted for the essential NUP49 gene and complemented with a wild-type NUP49 allele carried by plasmid pCH1122-NUP49. After selection on SDC-leu plates, transformants displayed a typical red–white sectoring phenotype because of the loss of the ADE3-carrying pCH1122-NUP49 plasmid (data not shown), indicating that GFP-Nup49p rescues the disruption of NUP49. The expression of GFPNup49p was also analyzed by SDS-PAGE and Western blotting using anti-Nup49p and anti-GFP antibodies. As shown in Fig. 1 A, an anti-Nup49p antibody recognized a single band corresponding to wild-type Nup49p in the VD1R strain (lane 3). Upon transformation with plasmid pUN100-GFP-NUP49, an additional band migrating at the expected size for the GFP-Nup49p fusion protein was detected by both anti-Nup49p and anti-GFP antibodies (lane 4). In white colonies, derived from the VD1R strain expressing GFP-Nup49p, wild-type Nup49p was no longer detected (lane 5), thereby confirming that GFP-Nup49p is able to rescue the otherwise lethal phenotype of a nup49 null mutant. As judged by the intensity of the signals obtained with anti-Nup49p, GFP-Nup49p displayed a similar expression level as compared to endogenous Nup49p when expressed either in wild-type (lanes 4 and 5) or in NUP133disrupted cells (nup133−; lane 2).

Figure 1.

Expression and localization of Nup49p tagged with GFP. (A) Immunoblotting analysis. Whole cell extracts were prepared from yeast strains either containing or not containing the pUN100-GFP-NUP49 plasmid: nup133− (lane 1), nup133− + pUN100-GFPNUP49 (lane 2), VD1R (lane 3), VD1R + pUN100-GFP-NUP49 (lane 4), and VD1R + pUN100-GFP-NUP49 and lacking pCH1122NUP49 (lane 5). Equivalent amounts of extracts from each strain were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting using an antiNup49p and an anti-GFP antibody. The positions of Nup49p and GFP-Nup49p and the molecular masses (kD) of a protein standard are indicated. (B) Colocalization of GFP-Nup49p and nuclear pore complex antigens. Wild-type (WT) and nup133− cells expressing GFPNup49p, which is detected in the fluorescein channel (GFP), were fixed and processed for indirect immunofluorescence using the monoclonal antibody mAb414 followed by rhodamine-labeled goat–anti mouse IgG. DNA staining and the Nomarski optics view are shown. (C) In vivo localization of GFP-Nup49p using confocal microscopy. Two successive sections (0.5 μm apart) are presented. A ringlike staining of the nuclear periphery, typical for nucleoporins, is observed in wild-type cells (WT). Arrows show absence of nuclear pore complexes in areas of close association between the nucleus and the vacuole. In nup133− and to a lesser extent nup85− strains, nuclear pores are clustered. Bars, 5 μm.

The subcellular localization of GFP-Nup49p was analyzed in both wild-type and nup133− cells that display a constitutive NPC clustering phenotype (Doye et al., 1994; Li et al., 1995; Pemberton et al., 1995). Cells were fixed and immunofluorescence was performed using the monoclonal antibody mAb414 that recognizes nuclear pore antigens (Aris and Blobel, 1989) (Fig. 1 B). In wild-type cells, a similar punctate staining around the nuclear envelope was detected with both GFP-Nup49p and the monoclonal antibody mAb414. The localization of GFP-Nup49p at the NPC was further confirmed by its colocalization with the mAb414 epitopes at the NPC clusters present in nup133− cells (Fig. 1 B).

Similar results were obtained when GFP-Nup49p localization was examined in living cells using confocal microscopy (Fig. 1 C). The preservation of the cell morphology further enabled the visualization of specific features of NPC distribution within wild-type cells, such as the lack of labeling in areas of close association between the nucleus and the vacuole (Severs et al., 1976). In agreement with the NPC-clustering phenotypes previously observed in nup133− and NUP85-disrupted (nup85−) cells (Doye et al., 1994; Li et al., 1995; Pemberton et al., 1995; Goldstein et al., 1996), GFP-Nup49p was localized within one or few clusters in nup133− cells (Fig. 1 C), whereas an intermediate phenotype with small aggregates, crescent-shaped and faint ringlike structures, could be observed in nup85− cells. In conclusion, these results indicate that GFP-Nup49p is functionally targeted to the NPC. Similarly, it has been recently reported that GFP-tagged Nup85p is functional and localized to the NPC (Goldstein et al., 1996).

The ability to follow GFP-Nup49p–expressing cells in vivo was essential to analyze the successive changes in nuclear envelope shape during cell division. In wild-type cells followed at 10-min intervals, insertion of the nucleus into the neck, nuclear elongation and migration into the bud, and the final bilobed shape of the nucleus during karyokinesis could be readily assessed (Fig. 2 A). Therefore, in cells displaying such a homogeneous NPC distribution, GFP-Nup49p provides an alternative tool to previously described fluorescent lipophilic dyes such as DiOC6 (Koning et al., 1993) to monitor in vivo changes in nuclear shape and position.

Figure 2.

Nuclear pore distribution in wild-type and nup133− cells at 10-min intervals. Cells expressing GFP-Nup49p were examined by confocal microscopy as described in Materials and Methods. Each image is a two-dimensional projection of images collected at all relevant z-axes. (A) In wild-type RS453a cells, elongation of the nucleus towards the daughter cell can be observed. (B) In synchronized nup133− a cells, a dynamic distribution of the clusters of NPCs is observed (left). Soon after cell division (right), both mother and daughter nuclei move towards the future buds; note the position of clustered NPCs close to each novel budneck. During karyokinesis (bottom), elongated clusters that span the two nuclei can also be seen.

In nup133− cells, changes in the distribution of the NPC clusters were observed within 10 min (Fig. 2 B, left). Just after cell division, as the nuclei moved towards the site of the future buds, the rotation of the nuclei and/or the modified distribution of NPC clusters within the nuclear envelope frequently led to aggregated NPCs that were positioned close to the budnecks (Fig. 2 B, right). In other cells, an elongated cluster of pores that spanned the two nuclei was seen during karyokinesis (Fig. 2 B, bottom). These results indicate a dynamic distribution of the NPC clusters within the nuclear envelope and further suggest that the localization of the NPC aggregates is, in general, not random, but rather permits the distribution of clustered NPCs to the daughter nucleus.

Induction of Nup133p Expression in nup133−Cells Restores a Homogeneous Distribution of Nuclear Pore Complexes

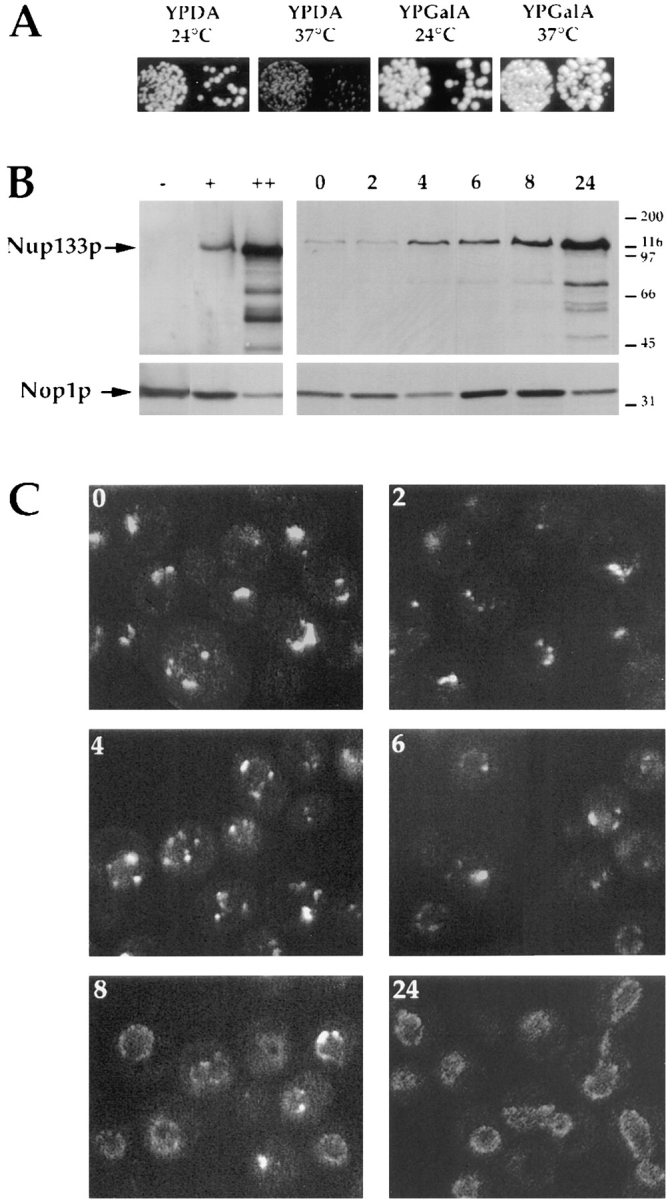

To investigate further the role of Nup133p in NPC distribution, a GAL-nup133 strain was constructed, in which Nup133p expressed under the control of the inducible GAL10 promotor was integrated at the NUP133 locus by homologous recombination. On galactose-containing medium (YPGalA), the GAL10 promotor is induced, and GAL-nup133 cells showed normal growth properties both at 24 and 37°C (Fig. 3 A). In agreement with the temperature-sensitive phenotype of NUP133-disrupted cells (Doye et al., 1994), GAL-nup133 cells displayed a growth defect at 37°C upon repression of the GAL10 promotor on glucose-containing plates (YPDA). However, a residual growth could be observed at 37°C, which correlated with the low level of Nup133p detected by Western blotting (Fig. 3 B), and probably reflected a leak of the GAL10 promoter. During galactose induction, Nup133p level increased after 4 h and was similar to wild-type Nup133p after about 8 h. GAL-nup133 cells grown overnight in galactose-containing medium reached a Nup133p-expression level similar to Nup133p when the protein was overexpressed from a high copy number plasmid.

Figure 3.

Induction of Nup133p expression in GAL-nup133 cells. (A) Growth properties of GAL-nup133 cells. Two equivalent dilutions of GAL-nup133 cells were spotted on glucose (YPDA)– or galactose (YPGalA)–containing plates and incubated for 3 d at 24°C or 2 d at 37°C. (B) Analysis of Nup133p expression levels by immunoblotting. Whole cell extracts were prepared from the following strains: nup133− (−), wild-type RS453 (+), nup133− carrying the high copy number plasmid pRS424-NUP133 (++), and GAL-nup133 grown overnight in YPDA medium (0) or shifted for 2, 4, 6, 8, and 24 h to YPGalA medium. Total protein corresponding to similar amounts of cells were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting using an anti-Nup133p antibody. AntiNop1p antibody was used to control the amounts of protein loaded. The molecular masses (kD) of a protein standard are indicated. (C) Analysis of NPC distribution during Nup133p induction. Cells from strain GAL-nup133 carrying plasmid pUN100GFP-NUP49 were grown in SDC-leu medium (0) or shifted to SGalC-leu medium for 2, 4, 6, 8, or 24 h as indicated and analyzed by confocal microscopy. Each image is a two-dimensional projection of images collected at all relevant z-axes using the fluorescein channel. The fluorescent staining patterns reflect the intracellular distribution of NPCs.

NPC distribution was visualized in GAL-nup133 cells expressing GFP-Nup49p at various stages during galactose induction. When the GAL10 promoter was repressed, clusters of NPCs along the nuclear envelope were revealed by the GFP-Nup49p fluorescence (Fig. 3 C); however, the overall number of aggregates was higher when compared to nup133− cells (see Fig. 1 C). A further increase in the number of nuclear pore clusters was observed after 4 h growth in galactose-containing medium. Finally, a ringlike staining reflecting a homogeneous distribution of the NPCs appeared in some cells after 6 h, and was detected in most cells after growth for 8 h in galactose-containing medium. Since the intensity of the GFP signal directly reflects the amount of the fusion protein, the brighter fluorescence intensity of the NPC clusters when compared to the ringlike staining suggests that Nup133p induction finally leads to a homogeneous distribution of the NPCs within the nuclear envelope but does not alter their overall number. The correlation between the expression level of Nup133p (Fig. 3 B) and the number of NPC clusters (Fig. 3 C) suggests that induction of Nup133p expression induces a progressive fragmentation of the NPC aggregates that finally leads to a wild-type nuclear pore distribution. However, because of the delay (8 h) required to reach a wild-type NPC distribution, this final phenotype could reflect either the insertion in the nuclear envelope of de novo synthesized pores during successive cell divisions or the redistribution of preexisting nuclear pore complexes.

Analysis of GFP-Nup133p Targeting to nup133− Nuclei

To analyze whether Nup133p-induced NPC redistribution could be uncoupled from successive nuclear divisions, we devised an in vivo assay based on the use of heterokaryons. kar1 mutants that display nuclear fusion defects thus leading to the formation of heterokaryons have been previously used in S. cerevisiae for assaying the shuttling of proteins from one nucleus to another (Flach et al., 1994) or the targeting of Tub4p to the spindle pole body (Marschall et al., 1996). The basic design of our experiment was therefore to construct heterokaryons between nup133− cells and cells either expressing or overexpressing Nup133p, the kar1-1 mutation being carried by either of the two mating partners. We expected that Nup133p synthesized by the wild-type cell should be targeted to the nup133− nucleus upon zygote formation, thereby complementing the NPC clustering phenotype.

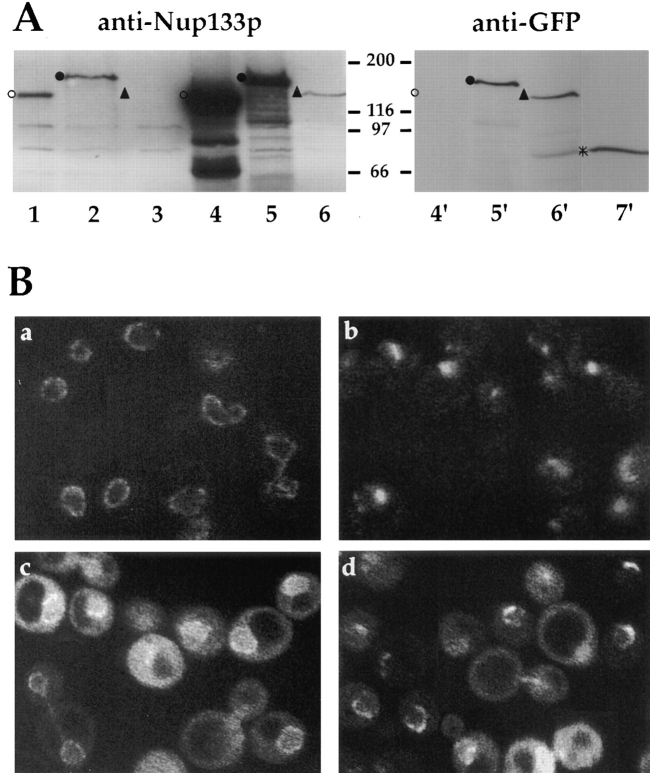

To follow the targeting of Nup133p during this mating process, a GFP-NUP133 fusion gene, expressed under the authentic NUP133 promotor, was inserted both in the single copy number pUN100 plasmid or the high copy number plasmid pRS424. As a further control, we tagged with GFP the previously characterized nup133ΔN mutant that is targeted to the NPCs but does not complement the clustering phenotypes of nup133− cells (Doye et al., 1994). Both GFP-Nup133p and GFP-nup133ΔNp fusion proteins were able to rescue the temperature-sensitive phenotype of nup133− cells (data not shown). On Western blots, the expression level of wild-type Nup133p and GFP-Nup133p detected with the anti-Nup133p antibody were equivalent (Fig. 4 A, lanes 1 and 2). Since the antigen used to raise the anti-Nup133p antibody has a limited overlap with the GFP-nup133ΔNp mutant, a faint signal could only be detected with anti-Nup133p in yeast cells overexpressing this fusion protein (lane 6). While GFP-Nup133p and GFPnup133ΔNp expressed on a single-copy number plasmid were hardly detectable with the anti-GFP antibody (data not shown), a comparable staining intensity was obtained with this antibody for the overexpressed GFP-Nup133p and GFP-nup133ΔNp proteins (Fig. 4 A, lanes 5′ and 6′). It should be noted that the anti-GFP antibody gave similar staining intensities for GFP-Nup49p expressed on a centromeric plasmid and for overexpressed GFP-Nup133p or GFP-nup133ΔNp (Fig. 4 A, compare lane 7′ to lanes 5′ and 6′). Although variations in the transfer efficiency of the two proteins on nitrocellulose cannot be excluded, this result suggests that in yeast, the Nup49p nucleoporin is more abundant than Nup133p.

Figure 4.

Expression and localization of GFP-Nup133p and GFP-nup133ΔNp. (A) Immunoblotting analysis. To follow the expression of wild-type and GFP-tagged Nup133p, whole cell extracts were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting using either an antibody directed against the amino-terminal domain of Nup133p or an anti-GFP antibody. The following strains were analyzed: kar1-1 (lane 1), nup133− + pUN100-GFP-NUP133 (lane 2), nup133− + pUN100-GFP-nup133ΔN (lane 3), nup133− + pRS424-NUP133 (lanes 4 and 4′), nup133− + pRS424-GFPNUP133 (lanes 5 and 5′), and nup133− + pRS424-GFPnup133ΔN (lanes 6 and 6′). As reference, a whole cell extract from strain VD1R + pUN100-GFP-NUP49 was loaded on the same gel (7′). The positions of Nup133p (○), GFP-Nup133p (•), GFP-nup133ΔNp (Δ), and GFP-Nup49p (*) are indicated. (B) Confocal analysis of nup133− cells expressing GFP-Nup133p and GFP-nup133ΔNp chimeras. (a) Expression of GFP-Nup133p carried by plasmid pUN100 gives rise to a faint, ringlike staining. (b) GFP-nup133ΔNp expressed on the pUN100 centromeric plasmid localizes within NPC clusters. (c and d) When carried by the high copy number plasmid pRS424, GFP-Nup133p (c) and GFPnup133ΔNp (d) present a heterogeneous expression level; some cells display an additional cytoplasmic and nuclear staining. Images correspond to individual sections recorded by confocal microscopy. To enable quantitative comparison, the power intensity of the laser was set to the same value in each case.

Confocal analysis of nup133− cells expressing GFPNup133p revealed a ringlike staining around the nuclear envelope, indicating that this fusion protein is targeted to the NPCs and complements the clustering phenotype of the nup133− mutant (Fig. 4 B, a). In agreement with Western blotting data, the fluorescent signal was, however, weaker as compared to the one obtained in GFP-Nup49p– expressing cells. As previously reported for the protein A–tagged mutant (Doye et al., 1994), GFP-nup133ΔNp expressed on a centromeric plasmid localized within NPC clusters (Fig. 4 B, b). Upon overexpression of either fusion, a heterogeneous signal was obtained that probably reflected the variable amount of copies of the 2μ plasmid present in each cell (Fig. 4 B, c and d). Cells that highly overexpressed GFP-Nup133p displayed not only a typical ringlike staining but also a very strong nuclear and cytoplasmic staining, whereas the vacuoles were not labeled (Fig. 4 B, c).

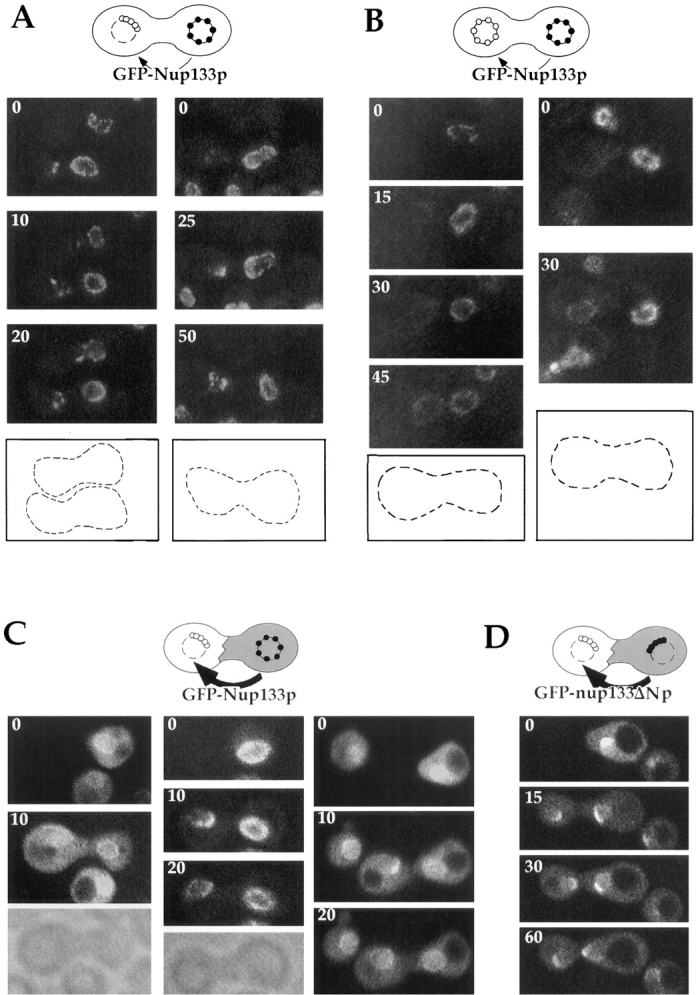

These various constructs were used to analyze the targeting of GFP-Nup133p to the nucleus of nup133− cells in heterokaryon assays. Fusions were first made between nup133− cells and nup133−kar1-1 cells expressing GFPNup133p on a centromeric plasmid (Fig. 5 A). Before fusion, the nup133− nucleus was not labeled, whereas GFPNup133p expression in the nup133−kar1-1 cell gave rise to a ringlike staining. Because of the low expression level of GFP-Nup133p, no more than three successive images could be recorded for each zygote. After heterokaryon formation, GFP-Nup133p labeling was initially restricted to one or two aggregates along the nuclear envelope of the nup133− nucleus. Within 10 to 20 min, the number of labeled aggregates increased (Fig. 5 A). At later stages, a homogeneous ringlike staining was observed (data not shown). As control, we also analyzed the targeting of GFP-Nup133p to wild-type nuclei by mating nup133−kar1-1 cells expressing GFP-Nup133p with wild-type cells. Under those conditions, a progressive and homogeneous labeling around the nuclear envelope of the wild-type nucleus was observed (Fig. 5 B). This result indicates that upon mating, GFPNup133p can be targeted to the clustered NPCs present in nup133− cells as well as to the randomly distributed NPC present in wild-type cells.

Figure 5.

Analysis of GFPNup133p targeting to nup133− and wild-type cells upon mating. (A and B) nup133−α (A) or wild-type (B) cells were mated with nup133−kar1-1a cells carrying the pUN100-GFPNUP133 plasmid as described in Materials and Methods. Heterokaryons defective for nuclear fusion were followed by confocal microscopy. Schematics of the heterokaryon boundaries are shown for reference. (C and D) nup133−kar1-1α cells were mated with nup133− a cells carrying the pRS424-GFP-NUP133 (C) or the pRS424-GFP-nup133ΔN plasmid (D). Heterokaryons were followed by confocal microscopy. Time 0 corresponds to the last image recorded before cytoduction, i.e., when no cytoplasmic staining is detectable in the left (nup133−kar1-1) cells. A transmission image of the first two heterokaryons is shown for reference.

Using a similar procedure, targeting of overexpressed GFP-Nup133p was analyzed upon mating between nup133− kar1-1 and nup133− cells overexpressing GFP-Nup133p (Fig. 5 C). Because of the cytoplasmic staining associated with overexpression of GFP-Nup133p, early stages of cytoplasmic fusion could be visualized. Under these conditions, GFP-Nup133p, which was probably provided by the cytoplasmic pool, was rapidly targeted to a restricted area of the nuclear envelope. Within 10–20 min, a homogeneous labeling around the nup133− nucleus was observed. We examined the specificity of this targeting by mating nup133− kar1-1 cells with cells overexpressing GFP-nup133ΔNp. As shown in Fig. 5 D, GFP-nup133ΔNp was also rapidly targeted to a defined area of the nuclear envelope, but unlike in the case of GFP-Nup133p, this labeling did not further spread along the nuclear envelope, even 60 min after cytoduction. Taken together, these results indicate that both fusions are efficiently targeted to both randomly distributed and clustered NPCs in which the binding sites for Nup133p are thus accessible. Furthermore, the appearance of a homogeneous labeling around the nuclear envelope of nup133− nuclei correlates with the amount of incorporated GFP-Nup133p and requires the presence of its amino-terminal domain.

Analysis of NPC Redistribution upon Mating between nup133− and Wild-Type Cells

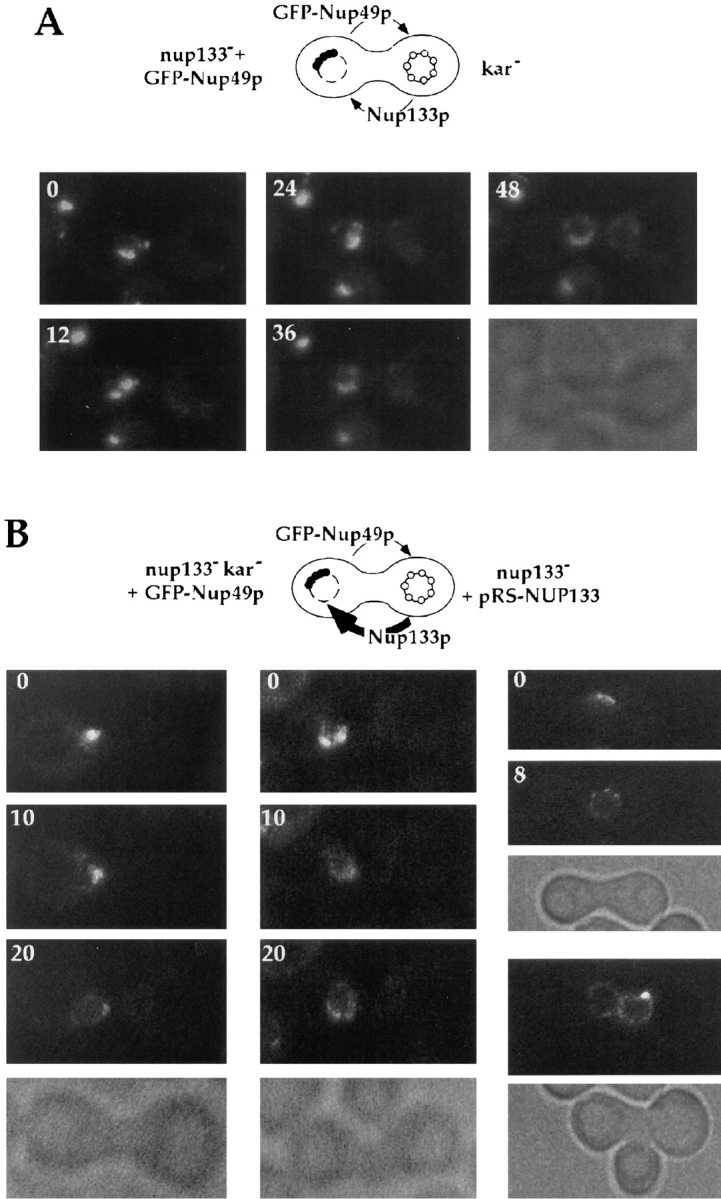

The previous experiments suggested that Nup133p is able to induce the redistribution of the nup133− clustered NPCs. To further demonstrate that the homogeneous distribution of GFP-Nup133p around the nuclear envelope correlates with the redistribution of the nuclear pore complexes themselves, similar cytoduction experiments were performed, in which GFP-Nup49p expressed in the nup133− cells was used to follow NPC distribution.

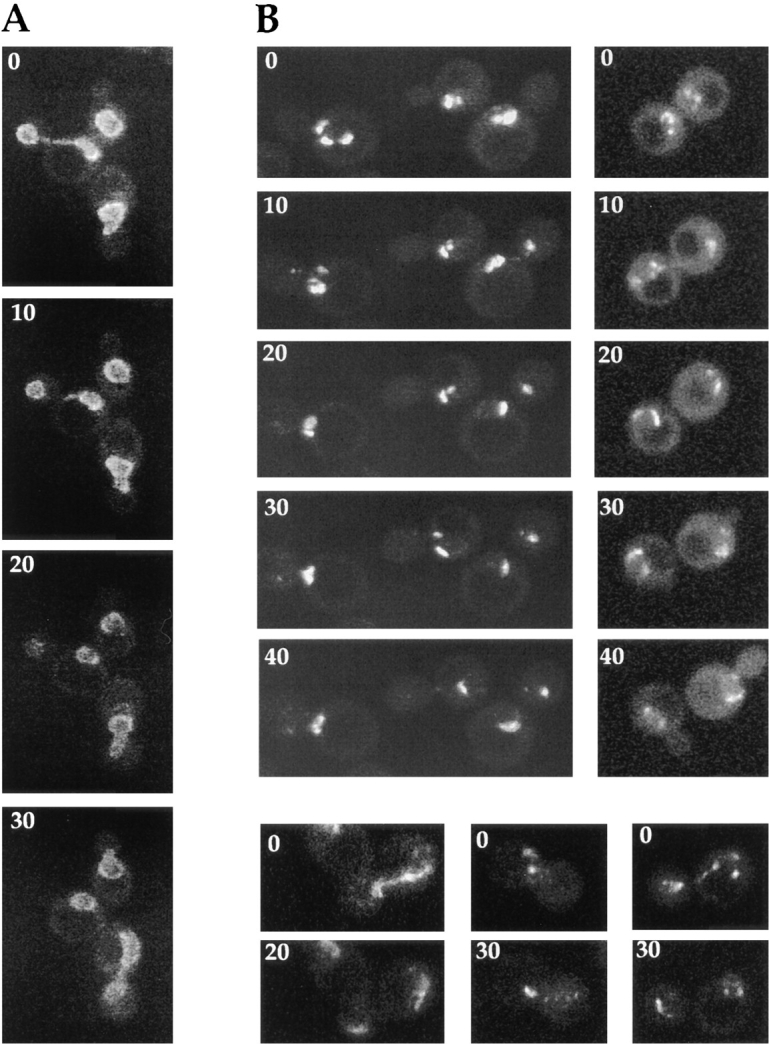

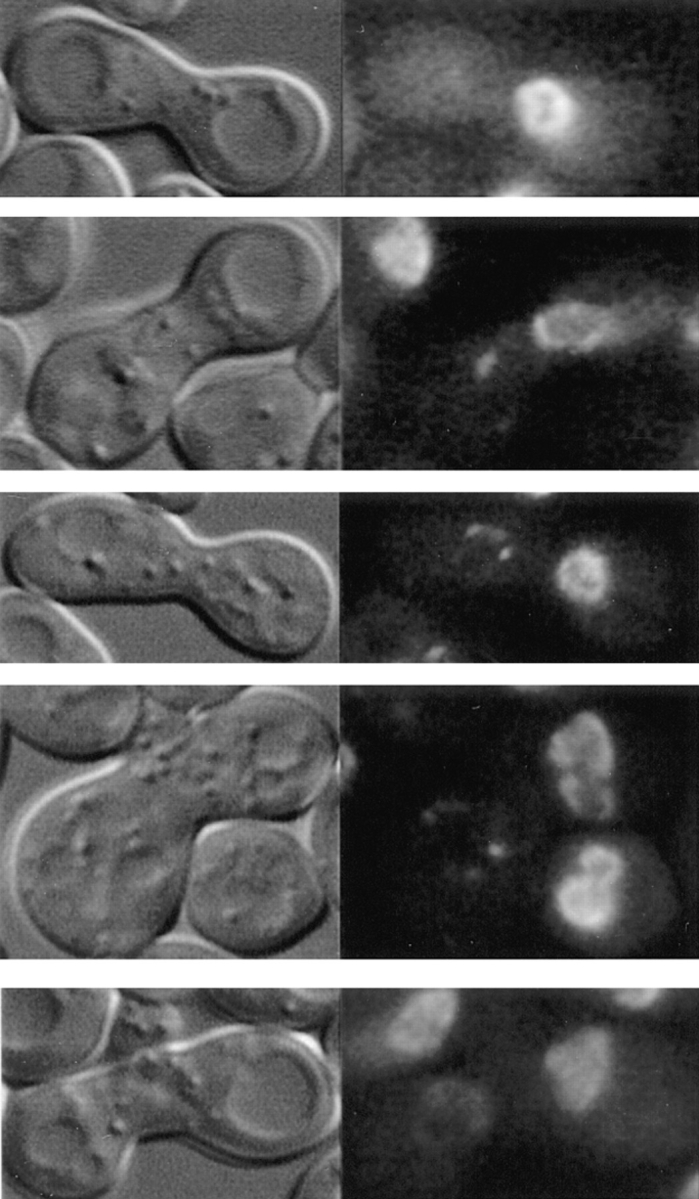

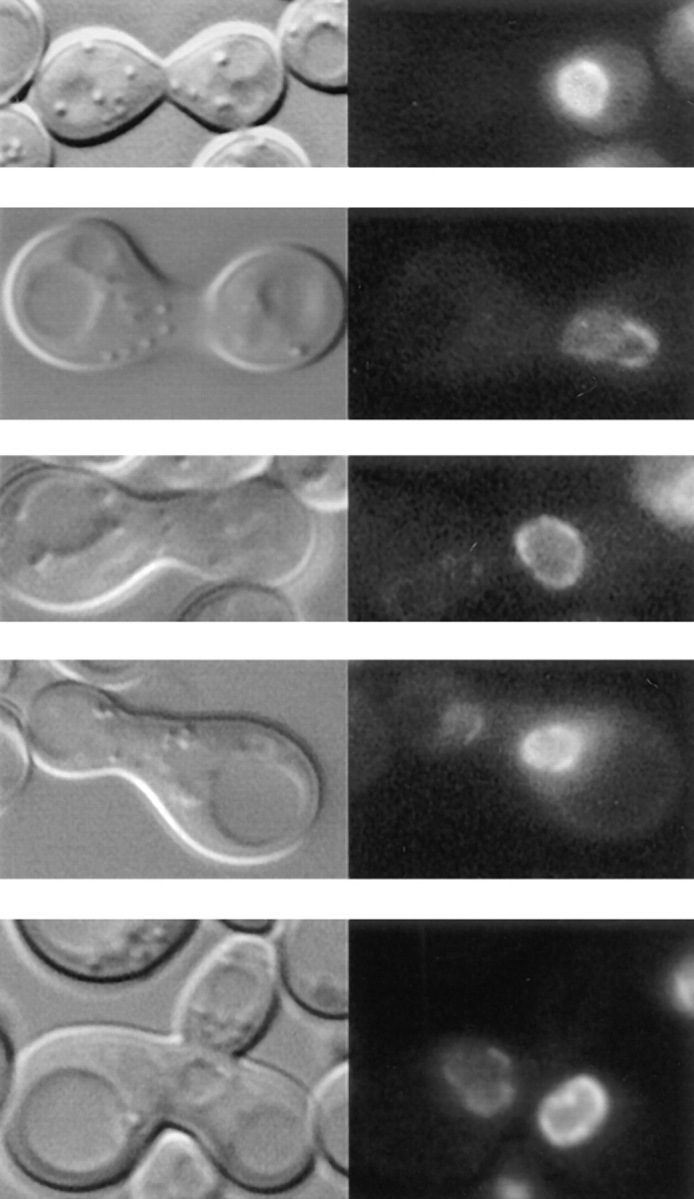

In the first set of experiments, nup133− cells expressing GFP-Nup49p were mixed with kar1-1 cells and analyzed by confocal microscopy. Fig. 6 A illustrates the GFPNup49p localization pattern of a typical heterokaryon at various stages after cell fusion. At early stages (0–12 min), NPC clusters on the nup133− nuclear envelope were brightly labeled with GFP-Nup49p, whereas the wild-type nucleus was not labeled. Subsequently, a decreased intensity of the GFP-Nup49p signal within the NPC clusters was found, coincident with the appearance of additional aggregates and the spreading of the fluorescent labeling along the nuclear envelope. Finally, nearly wild-type nuclear pore distribution was generally observed within 40 to 60 min. At this late stage, zygotes usually displayed a typical trilobed shape. In the mean time, a homogeneous albeit fainter labeling of the wild-type nucleus progressively appeared, indicating that GFP-Nup49p expressed by the nup133− cell can be targeted to the other nucleus.

Figure 6.

Overexpression of Nup133p increases the rate of NPC redistribution during the mating process. (A) nup133− α cells carrying the pUN100-GFP-NUP49 plasmid were mixed with kar1-1a cells. An example of such a heterokaryon, followed at 12-min intervals using confocal microscopy, is presented. The transmission image (bottom) shows the morphology of the zygote at the end of the experiment (48 min). (B) nup133−kar1-1a cells expressing GFP-Nup49p were mixed with nup133− α cells expressing Nup133p carried by the high copy number plasmid pRS424-NUP133. Heterokaryons were followed at 10-min intervals. At time 0 (when the septum between the mating cells was still detectable), the clustered nuclear pores from the nup133−kar1-1 nuclei are stained with GFP-Nup49p. After cytoduction, the redistribution of nuclear pores labeled with GFP-Nup49p occurs within 10–20 min. A faint labeling of the other nuclei can be detectable after 20 min. In the upper heterokaryon, redistribution of the GFP-Nup49p labeling had occurred within 8 min (right). Small aggregates randomly distributed around the nuclear envelope are detectable. The other heterokaryon had already reached a later stage in the mating process (as revealed by its trilobed morphology on the corresponding transmission image) and presents a staining of both nuclei.

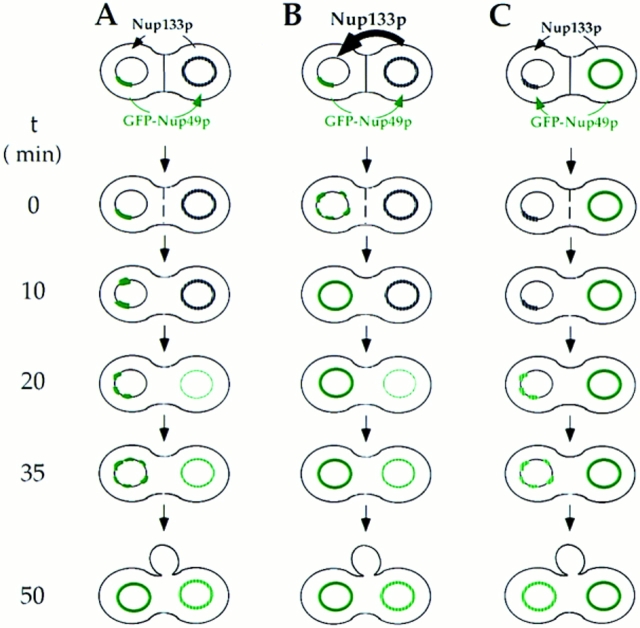

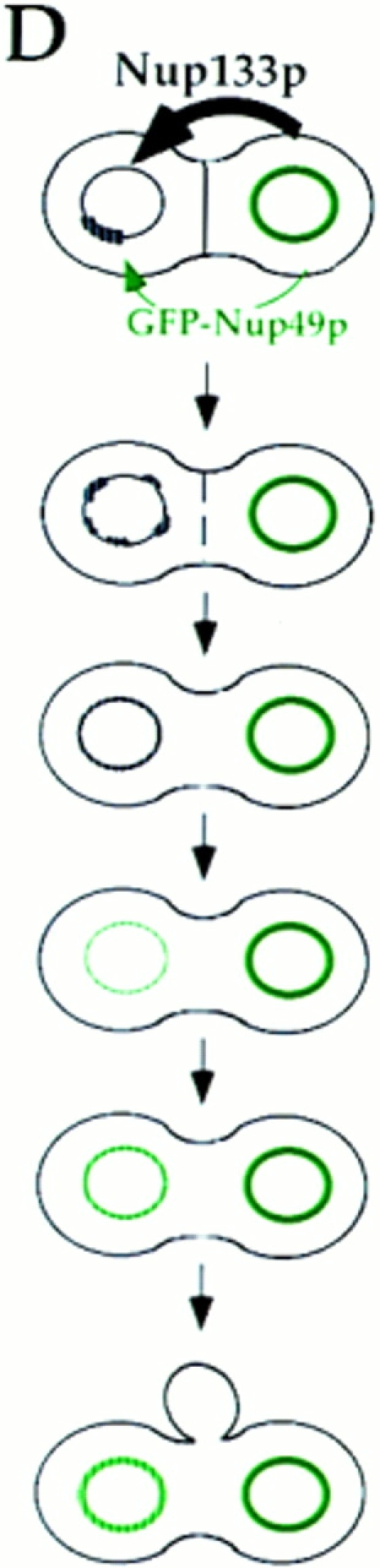

Strikingly, when nup133− kar1-1 cells expressing GFPNup49p were mixed with yeast cells overexpressing Nup133p, the redistribution of the clustered NPCs could then be achieved within 10 min (Fig. 6 B). Intermediate stages could sometimes be recorded, in which small NPC aggregates were homogeneously distributed around the nuclear envelope (Fig. 6 B, right). The increased rate of NPC redistribution upon mating with cells overexpressing Nup133p was also revealed by the shape of the zygote in which no bud formation was yet detectable. In contrast, the progressive labeling of the wild-type nucleus occurred independently of the expression level of Nup133p (compare Fig. 6, A and B). These results were further confirmed by random analysis of ∼100 individual heterokaryons recorded at various stages during the mating process. Schematic representation of the successive steps occurring during either mating process are summarized in Fig. 7, A and B. The fast rate of NPC redistribution observed when overexpressed Nup133p is provided to the nup133− nucleus suggests that, under such conditions, the homogeneous GFP-Nup49p labeling reflects the redistribution of preexisting NPCs.

Figure 7.

Schematic representation of GFP-Nup49p localization (green) and NPC distribution during the mating process. (A and B) mating between nup133− cells expressing GFP-Nup49p and cells expressing or overexpressing Nup133p (see also Fig. 6). (C and D) Analysis of GFP-Nup49p targeting to the nup133− nucleus upon mating between nup133− cells and cells expressing GFP-Nup49p together with wild-type Nup133p (C) or overexpressed Nup133p (D). The localization of GFP-Nup49p and the shape of heterokaryons recorded on the CCD camera at various stages during the mating process are presented. The delay required for these processes, as estimated through kinetic analysis of individual heterokaryons, is indicated on the left.

To try to demonstrate that NPC redistribution can effectively be uncoupled from de novo NPC biogenesis, a final set of experiments were performed, in which GFP-Nup49 was provided by the wild-type nucleus together with wildtype or overexpressed Nup133p. The rationale of this experiment was that if NPC redistribution requires de novo NPC biogenesis, this process should be stimulated by the overexpressed Nup133p. Accordingly, the rate of incorporation of GFP-Nup49p in the nup133− nuclei should be increased and intermediate stages with brightly labeled aggregates should be observed. For these experiments, random analysis of ∼100 individual heterokaryons, recorded at various stages during the mating process, was performed. Similar results were also obtained by kinetic analysis of heterokaryons (data not shown). Heterokaryons representative of either mating experiment are respectively presented in Fig. 7, C and D. Upon mating between nup133− cells and kar1-1 cells expressing GFP-Nup49p, the GFP-Nup49p labeling initially appears within one or few NPC clusters. At later time points, an increased number of GFP-Nup49p–labeled aggregates can be seen, which finally leads to a smooth ringlike staining (Fig. 7 C). In contrast, when a strain overexpressing Nup133p was used, >90% of the analyzed heterokaryons follow the kinetics summarized in Fig. 7 D: a homogeneous and very faint staining of the entire nuclear envelope can be initially detected within 20 min after cytoduction. At later time points, the intensity of the labeling progressively increases. Furthermore, the rate of GFP-Nup49p incorporation within the nup133− nucleus is similar to the one observed upon targeting of GFP-Nup49p to wild-type nuclei (compare Fig. 6, A and B, to Fig. 7 D). As summarized in Fig. 7, these results indicate that under such mating conditions, NPC redistribution occurs before the incorporation of GFP-Nup49p in the nup133− nucleus.

Discussion

In this paper, we have demonstrated that it is possible to GFP-tag Nup49p and Nup133p to produce functional fusions that rescue lethal or temperature-sensitive phenotypes of strains that contain deletion of the corresponding genes. In both wild-type and nup133− cells, GFP-Nup49p colocalizes with antigens recognized by the antinucleoporin mAb414. In addition, in nup133− and nup85− cells the fluorescent signal was concentrated within a restricted area of the nuclear envelope corresponding to the clustered NPCs; similar results were also obtained when GFPNup133p is expressed in nup85− cells (data not shown). This labeling is in agreement with the clustering phenotype observed in nup133− and nup85− cells fixed and processed for electron microscopy (Doye et al., 1994; Li et al., 1995; Pemberton et al., 1995; Goldstein et al., 1996). Furthermore, when cells were not processed for immunostaining, specific features of NPC distribution, such as the absence of NPCs from areas in close association between the nucleus and the vacuoles, could be observed by confocal microscopy. This staining is consistent with previous reports using freeze-fracture electron microscopy, which showed the absence of nuclear pores in nuclear envelope areas adjacent to the vacuole (Severs et al., 1976). Taken together, these results clearly demonstrate that the in vivo localization of the GFP-nucleoporin fusions faithfully reflects NPC distribution in both wild-type and nucleoporin mutant yeast cells.

Recently, a light microscopy method in which single NPCs can be visualized and their three-dimensional arrangement assessed in permeabilized 3T3 cells has been described (Kubitscheck et al., 1996). However, because of the higher density of NPCs in wild-type yeast cells (11–15 pores/μm2) as compared to 5 pores/μm2 in 3T3 cells (Severs et al., 1976; Maul and Deaven, 1977; Kubitscheck et al., 1996), single yeast nuclear pores labeled with GFP-Nup49p cannot be visualized by this method (Kubitscheck, U., personal communication). Therefore, to analyze the dynamics of nuclear pore distribution in yeast, we have used the properties of NUP133-disrupted (nup133−) cells that display a constitutive NPC clustering that is not associated with drastic alterations in the structure of the nuclear envelope (Doye et al., 1994; Li et al., 1995). This strain enabled us to follow two aspects of NPC dymanics: the movements of NPC clusters in dividing nup133− cells and the redistribution of the clustered NPCs once Nup133p is provided to nup133− cells.

In dividing nup133− cells expressing GFP-Nup49p, apparent movements of NPC clusters could be visualized, whereas no major changes in their distribution were detected in cells in stationary phase (data not shown). In dividing cells, the dynamic distribution of the NPC clusters could thus be related to modifications in the nuclear shape and/or to the nuclear rotation that is required for correct positioning of the spindle pole bodies. It has also been reported that in S. cerevisiae, both nuclear surface area and nuclear pore number rapidly increase during nuclear division up until cell division (Jordan et al., 1977). The progressive spreading of NPC clusters along the nuclear envelope could therefore be induced by membrane formation if localized in between NPC clusters. Alternatively, lateral movements of NPC clusters within the nuclear envelope, possibly driven by interactions with as yet unidentified structures, may also be involved in this process (see below).

To induce the redistribution of the clustered NPCs present in nup133− cells, Nup133p was either expressed under the control of the inducible GAL10 promoter or provided to nup133− cells upon mating and subsequent cytoduction. Using both approaches, a correlation could be made between the expression level of Nup133p and the degree of nuclear pore clustering: an intermediate clustering phenotype could be observed in cells that expressed low levels of Nup133p, whereas random NPC distribution was only achieved once wild-type levels of Nup133p were reached. This result suggests that a threshold level of Nup133p is required for homogeneous NPC distribution in wild-type cells. The correlation between the amount of Nup133p provided to the nup133− nucleus upon cytoduction and the rate of NPC redistribution further demonstrates that Nup133p is directly involved in this process.

A major question raised in this study was to determine how Nup133p establishes an even NPC distribution, and whether this redistribution could be uncoupled from de novo NPC biogenesis and turnover. Indeed, upon mating between nup133− cells expressing GFP-Nup49p and wildtype cells, whereas a progressive redistribution of the clustered NPC was observed, a homogeneous labeling of the wild-type nucleus could be detected within 20 to 30 min. Similarly, when GFP-Nup49p was provided by the wildtype cell, its targeting to the nup133−-clustered NPCs could be observed. Similar results were also obtained upon analysis of GFP-Nup133p targeting to either wild-type or nup133− nuclei. This progressive labeling of the nucleus might correspond to the targeting of additional GFPtagged nucleoporin subunits to the preexisting nuclear pores, to the exchange between GFP-fusion proteins and preexisting nucleoporins, or to the incorporation of GFPNup49p upon de novo synthesis of NPCs. Since nothing is known so far concerning the rate of NPC biogenesis in yeast heterokaryons, we cannot discriminate between the incorporation of GFP-tagged nucleoporins in either preexisting or newly assembled NPCs. Since the precise subcellular localization of Nup49p and Nup133p has not been analyzed so far, these two nucleoporins might thus be peripheral and accordingly easily exchangeable components of the NPC. In contrast, a set of abundant nucleoporins including Pom152p, Nic96p, Nup157p, Nup170p, and Nup188p have been proposed to form the octagonal core structure of the NPC (Aitchison et al., 1995b ; Nehrbass et al., 1996) and accordingly might only be incorporated during NPC assembly. Similar cytoduction assays, if extended to the analysis of such nucleoporins, may thus allow discrimination between exchange of subunits within preexisting NPCs and de novo NPC assembly. Therefore, we cannot exclude that the apparent nuclear pore redistribution occurring within the nup133− nucleus upon mating with wild-type cells may, at least in part, involve NPC biogenesis. Under these standard conditions, NPC redistribution can therefore not be uncoupled from a putative de novo assembly of nuclear pores.

In contrast, the use of yeast cells overexpressing Nup133p in such cytoduction experiments enables us to dissociate NPC redistribution from this putative de novo NPC biogenesis. Under these mating conditions, the amount of available Nup133p is no longer limiting. The rapid targeting of overexpressed Nup133p to the clustered NPCs, as visualized when Nup133p is tagged with GFP, correlates with the increased rate of NPC redistribution, which can occur within 10 min. This could imply that simultaneous degradation of the clustered NPCs and de novo biogenesis of randomly distributed nuclear pores could take place. However, since no detectable labeling of the wild-type nuclei could be observed within this short period, both processes should be specifically stimulated in the nup133− nuclei. In addition, since the rate of NPC redistribution correlates with the amount of Nup133p provided to the nup133− nucleus, these two processes should be directly induced by Nup133p. One would then expect Nup133p to play a key role in both NPC biogenesis and degradation. Yet, unlike Nsp1p and Nic96p, whose depletion/mutation induces a decrease in nuclear pore density (Mutvei et al., 1992; Zabel et al., 1996), NUP133 disruption does not significantly alter the overall number of nuclear pores (Doye et al., 1994; Li et al., 1995; Pemberton et al., 1995). Furthermore, upon mating between nup133−cells and cells overexpressing Nup133p, analysis of GFP-Nup49p targeting revealed that the incorporation of GFP-Nup49p is not stimulated in the nup133− nuclei. In contrast, we could demonstrate that NPC redistribution occurs before the incorporation of GFP-Nup49p in the nup133− nucleus. These results therefore indicate that NPC redistribution does not require de novo NPC biogenesis but rather corresponds to the redistribution of preexisting clustered NPCs. This rapid redistribution is most likely achieved through lateral movements of preexisting NPCs within the nuclear envelope.

The finding that NPCs can rapidly move within the nuclear envelope was rather unexpected. Although rapid movements of transmembrane proteins that may result from membrane fluidity have been frequently reported, NPCs are elaborate structures embedded in two membranes, the inner and the outer nuclear membrane. NPC in higher eukaryotes were also shown to be physically anchored in the nuclear lamina (Aaronson and Blobel, 1974). In addition, filamentous structures associated with the baskets and projecting deeply inside the nucleus (Franke and Scheer, 1970; Scheer et al., 1976; Ris and Malecki, 1993) and a nuclear lattice that is thought to connect the distal rings of NPC baskets (Goldberg and Allen, 1992) have been observed in amphibian oocytes. Filaments protruding from the cytoplasmic side of the NPCs may also anchor the nuclear pores within the cytoskeleton (Scheer et al., 1976; for review see Goldberg and Allen, 1995). Similarly, both cytoplasmic and nuclear filaments associated with the nuclear pore complexes have been observed in S. cerevisiae (Allen and Douglas, 1989; Rout and Blobel, 1993). Although not demonstrated in higher eukaryotes, lateral movements of NPCs within the nuclear envelope may therefore require specific modifications of these NPC-anchoring structures. For example, drastic changes in NPC distribution are found during apoptosis (Falcieri et al., 1994). This may be related to nuclear lamina disassembly which has also been observed to occur during the active phase of apoptosis (Lazebnik et al., 1993). However, since no lamins have yet been identified in yeast, lateral mobility may be a specific characteristic of yeast NPCs. Finally, the rapid redistribution of preexisting NPCs, so far only demonstrated in our cytoduction assays, may reflect a specific feature of nup133− cells in which interactions between NPCs and putative anchoring structures would be impaired.

Various factors have been previously suggested to influence nuclear pore distribution in eukaryotic cells (discussed in Markovics et al., 1974; Severs et al., 1976). One factor is the presence of condensed chromatin in close proximity to the inner nuclear membrane. In addition, the vacuolar membrane was proposed to constitute one constraint on nuclear pore distribution in yeast (Severs et al., 1976). Unlike in these various models, changes in NPC distribution that occur in nucleoporin mutants have not been found associated with major changes in vacuolar or chromatin organization: in these mutants, pore-free areas are not associated with vacuolar membranes. In addition, immunolocalization of Rap1p, a telomere binding protein (Klein et al., 1992), revealed a normal telomere distribution in nup133− cells (Gotta et al., 1996). As an alternative explanation, the orientation of the clustered NPCs may reflect a higher order structure within the nucleus since NPC clusters in nup120-disrupted cells were generally found opposite to the nucleolus (Aitchison et al., 1995a ).

Among the nucleoporins that affect NPC distribution, Nup84p, Nup85p, and Nup120p are tightly associated within a nuclear pore subcomplex (Siniossoglou et al., 1996). NPC clustering may thus correspond to a specific defect shared by a subset of proteins associated within one or a few NPC substructures. A weak homology has been previously reported between the amino-terminal domain of Nup133p that encompasses our nup133-ΔN deletion and a central domain within Nup120p (Aitchison et al., 1995a ). In addition, nup133− and nup120− cells display a similar constitutive clustering phenotype that is not associated with major alteration of the nuclear envelope at permissive temperature (Doye et al., 1994; Aitchison et al., 1995a ; Heath et al., 1995; Li et al., 1995). Although phenotypical analysis of the corresponding nup120 deletion mutant would be necessary to test this hypothesis, the interaction of Nup133p and Nup120p with a common partner may be required for inducing or maintaining the homogeneous distribution of NPCs in the nuclear envelope. Our future goal will be to identify such component(s) interacting with the amino-terminal domain of Nup133p and required for homogeneous NPC distribution.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Michel Bornens for his constant support and Franck Perez (University of Geneva, Switzerland), for helpful suggestions throughout the course of this work. We are also indebted to Vincent Galy for his help in the mating experiments. We also thank Franck McKeon (Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA) for providing the S65T/V163A GFP mutant, Elmar Schiebel (Max-Planck-Institute, Martinsried, Germany), Christophe Cullin and Agnès Baudin (CGM, CNRS, Gif-sur-Yvette, France), Patrick Linder (Biozentrum, Bazel, Switzerland), and Ed Hurt (University of Heidelberg, Germany) for sharing plasmids, strains, and antibodies. The critical reading of the manuscript by C. Dargemont, E. Fabre (Institut Pasteur, Paris, France), G. Almouzni, S. Holmes, R. Golsteyn, T. Ruiz, and E. Bailly is gratefully acknowledged.

This work was supported by CNRS (UMR144), by the Institut Curie and from a grant from the “Fondation pour la Recherche Medicale.” N. Belgareh received a fellowship from the “Ministère de l'Enseignement et de la Recherche Supérieure.”

Abbreviations used in this paper

- DAPI

4′,6′-diamindino-2-phenylindole

- GFP

green fluorescent protein

- MD

megadaltons

- NPC

nuclear pore complex

- SDC or SGalC

synthetic dextrose or galactose complete media

- YPDA or YPGalA

yeast extract, bactopeptone, dextrose or galactose, and adenine

Footnotes

Address all correspondence to Valérie Doye, CNRS UMR144, Institut Curie, 26, rue d'Ulm, 75231 Paris Cedex 05, France. Tel.: (33) 1 42 34 64 13. Fax: (33) 1 42 34 64 21. E-mail: Valerie.Doye@curie.fr

References

- Aaronson RP, Blobel G. On the attachment of the nuclear pore complex. J Cell Biol. 1974;62:746–754. doi: 10.1083/jcb.62.3.746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aitchison JD, Blobel G, Rout MP. Nup120: a yeast nucleoporin required for NPC distribution and mRNA export. J Cell Biol. 1995a;131:1659–1675. doi: 10.1083/jcb.131.6.1659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aitchison JD, Rout MP, Marelli M, Blobel G, Wozniak RW. Two novel related yeast nucleoporins Nup170p and Nup157p: complementation with the vertebrate homologue Nup155p and functional interactions with the yeast nuclear pore-membrane protein Pom152p. J Cell Biol. 1995b;131:1133–1148. doi: 10.1083/jcb.131.5.1133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen JL, Douglas MG. Organization of the nuclear pore complex in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. . J Ultrastruct Mol Struct Res. 1989;102:95–108. doi: 10.1016/0889-1605(89)90047-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aris JP, Blobel G. Yeast nuclear envelope proteins cross-react with an antibody against mammalian pore complex proteins. J Cell Biol. 1989;108:2059–2067. doi: 10.1083/jcb.108.6.2059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bastos R, Lin A, Enarson M, Burke B. Targeting and function in mRNA export of nuclear pore complex protein Nup153. J Cell Biol. 1996;134:1141–1156. doi: 10.1083/jcb.134.5.1141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baudin-Baillieu, A., E. Guillemet, C. Cullin, and F. Lacroute. 1997. Construction of a yeast strain deleted for the TRP1 promotor and coding region that enhances the efficiency of the PCR-disruption method. Yeast. In press. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Berben G, Dumont J, Gilliquet V, Bolle P-A, Hilger F. The YDp plasmids: a uniform set of vectors bearing versatile gene disruption casettes for Saccharomyces cerevisiae. . Yeast. 1991;7:475–477. doi: 10.1002/yea.320070506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bogerd AM, Hoffman JA, Amberg DC, Fink GR, Davis LI. nup1 mutants exhibit pleiotropic defects in nuclear pore complex function. J Cell Biol. 1994;127:319–332. doi: 10.1083/jcb.127.2.319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christianson TW, Sikorski RS, Dante M, Shero JH, Hieter P. Multifunctional yeast high-copy-number shuttle vectors. Gene. 1992;110:119–122. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(92)90454-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cubitt AB, Heim R, Adams SR, Boyd AE, Gross LA, Tsien RY. Understanding, improving and using green fluorescent proteins. Trends Biochem Sci. 1995;20:448–455. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(00)89099-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doye V, Hurt EC. Genetic approaches to nuclear pore structure and function. Trends Genet. 1995;11:235–241. doi: 10.1016/s0168-9525(00)89057-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doye V, Wepf R, Hurt EC. A novel nuclear pore protein Nup133p with distinct roles in poly(A)+RNA transport and nuclear pore distribution. EMBO (Eur Mol Biol Organ) J. 1994;13:6062–6075. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06953.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doyle T, Botstein D. Movement of yeast cortical actin cytoskeleton visualized in vivo. . Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:3886–3891. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.9.3886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elledge SJ, Davis RW. A family of versatile centromeric vectors designed for use in the sectoring-shuffle mutagenesis assay in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. . Gene. 1988;70:303–312. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(88)90202-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fabre E, Hurt EC. Nuclear transport. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1994;6:335–342. doi: 10.1016/0955-0674(94)90023-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fabre E, Boelens WC, Wimmer C, Mattaj IW, Hurt EC. Nup145p is required for nuclear export of mRNA and binds homopolymeric RNA in vitro via a novel conserved motif. Cell. 1994;78:275–289. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90297-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falcieri E, Gobbi P, Cataldi A, Zamai L, Faenza I, Vitale M. Nuclear pores in the apoptotic cell. Histochem J. 1994;26:754–763. doi: 10.1007/BF00158206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flach J, Bossie M, Vogel J, Corbett A, Jinks T, Willins DA, Silver PA. A yeast RNA-binding protein shuttles between the nucleus and the cytoplasm. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14:8399–8407. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.12.8399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forbes DJ. Structure and function of the nuclear pore complex. Annu Rev Cell Biol. 1992;8:495–527. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cb.08.110192.002431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franke WW, Scheer U. The ultrastructure of the nuclear envelope of amphibian oocytes: a reinvestigation. 1. The mature oocyte. J Ultrastruct Res. 1970;30:288–316. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5320(70)80064-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franke, W.W., and U. Scheer. 1974. Structures and functions of the nuclear envelope. In The Cell Nucleus. H. Busch, editor. Academic Press, New York. 219–347.

- Goldberg MW, Allen TD. High resolution scanning electron microscopy of the nuclear envelope: demonstration of a new, regular, fibrous lattice attached to the baskets of the nucleoplasmic face of the nuclear pores. J Cell Biol. 1992;119:1429–1440. doi: 10.1083/jcb.119.6.1429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg MW, Allen TD. Structural and functional organization of the nuclear envelope. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1995;7:301–309. doi: 10.1016/0955-0674(95)80083-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein AL, Snay CA, Heath CV, Cole CN. Pleiotropic nuclear defects associated with a conditional allele of the novel nucleoporin Rat9p/Nup85p. Mol Biol Cell. 1996;7:917–934. doi: 10.1091/mbc.7.6.917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorsch LC, Dockendorff TC, Cole CN. A conditional allele of the novel repeat-containing yeast nucleoporin RAT7/NUP159 causes both rapid cessation of mRNA export and reversible clustering of nuclear pore complexes. J Cell Biol. 1995;129:939–955. doi: 10.1083/jcb.129.4.939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gotta M, Laroche T, Formenton A, Maillet L, Scherthan H, Gasser SM. The clustering of telomeres and colocalization with Rap1, Sir3, and Sir4 proteins in wild-type Saccharomyces cerevisiae. . J Cell Biol. 1996;134:1349–1363. doi: 10.1083/jcb.134.6.1349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grandi P, Emig S, Weise C, Hucho F, Pohl T, Hurt EC. A novel nuclear pore protein Nup82p which specifically binds to a fraction of Nsp1p. J Cell Biol. 1995;130:1263–1273. doi: 10.1083/jcb.130.6.1263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heath CV, Copeland CS, Amberg DC, Del Priore V, Snyder M, Cole CN. Nuclear pore complex clustering and nuclear accumulation of poly(A)+ RNA associated with mutation of the Saccharomyces cerevisiaeRAT2/NUP120 gene. J Cell Biol. 1995;131:1677–1697. doi: 10.1083/jcb.131.6.1677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurt EC, McDowall A, Schimmang T. Nucleolar and nuclear envelope proteins of the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. . Eur J Cell Biol. 1988;46:554–563. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurwitz ME, Blobel G. NUP82 is an essential yeast nucleoporin required for poly(A)(+) RNA export. J Cell Biol. 1995;130:1275–1281. doi: 10.1083/jcb.130.6.1275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jordan EG, Severs NJ, Williamson DH. Nuclear pore formation and the cell cycle in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. . Exp Cell Res. 1977;104:446–449. doi: 10.1016/0014-4827(77)90114-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahana, J., and P. Silver. 1996. Use of the A. victoria green fluorescent protein to study protein dynamics in vivo. In Current Protocols in Molecular Biology. F.M. Ausubel, R. Brent, R.E. Kingston, D.D. Moore, J.G. Seidman, J.A. Smith, and K. Struhl, editors. Greene Publishing Associates/Wiley- Interscience, Brooklyn, NY. 34(Suppl.) 9.7.22–9.7.2228.

- Kahana JA, Schnapp BJ, Silver PA. Kinetics of spindle pole body separation in budding yeast. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:9702–9711. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.21.9707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein F, Laroche T, Cardenas ME, Hofmann JF-X, Schweizer D, Gasser SM. Localization of RAP1 and topoisomerase II in nuclei and meiotic chromosomes of yeast. J Cell Biol. 1992;117:935–948. doi: 10.1083/jcb.117.5.935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klinkert MQ, Ruppel A, Felleisen R, Link G, Beck G. Expression of diagnostic 31/32 kilodalton proteins of Schistosoma mansonias fusions with bacteriophage MS2 polymerase. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1988;27:233–239. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(88)90042-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koning AJ, Lum PY, Williams JM, Wright R. DiOC6 staining reveals organelle structure and dynamics in living yeast cells. Cell Motil Cytoskel. 1993;25:111–128. doi: 10.1002/cm.970250202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubitscheck U, Wedekind P, Zeidler O, Grote M, Peters R. Single nuclear pores visualized by confocal microscopy and image processing. Biophys J. 1996;70:2067–2077. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(96)79811-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazebnik YA, Cole S, Cooke CA, Nelson WG, Earnshaw WC. Nuclear events of apoptosis in vitroin cell-free mitotic extracts: a model system for analysis of the active phase of apoptosis. J Cell Biol. 1993;123:7–22. doi: 10.1083/jcb.123.1.7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li O, Heath CV, Amberg DC, Dockendorff TC, Copeland CS, Snyder M, Cole CN. Mutation or deletion of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae RAT3/NUP133 gene causes temperature-dependent nuclear accumulation of poly(A)+RNA and constitutive clustering of nuclear pore complexes. Mol Biol Cell. 1995;6:401–417. doi: 10.1091/mbc.6.4.401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markovics J, Glass L, Maul GG. Pore patterns on nuclear membranes. Exp Cell Res. 1974;85:443–451. doi: 10.1016/0014-4827(74)90148-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marschall LG, Jeng RL, Mulholland J, Stearns T. Analysis of Tub4p, a yeast g-tubulin-like protein: implications for microtubule-organizing center function. J Cell Biol. 1996;134:443–454. doi: 10.1083/jcb.134.2.443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maniatis, T., E.T. Fritsch, and J., Sambrook. 1982. Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, New York.

- Maul GG, Deaven L. Quantitative determination of nuclear pore complexes in cycling cells with different DNA content. J Cell Biol. 1977;73:748–760. doi: 10.1083/jcb.73.3.748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moor H, Mühlethaler K. Fine structure in frozen-etched yeast cells. J Cell Biol. 1963;17:609–627. doi: 10.1083/jcb.17.3.609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mutvei A, Dihlmann S, Herth W, Hurt EC. NSP1 depletion in yeast affects nuclear pore formation and nuclear accumulation. Eur J Cell Biol. 1992;59:280–295. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nehrbass U, Rout MP, Maguire S, Blobel G, Wozniak RW. The yeast nucleoporin Nup188p interacts genetically and physically with the core structures of the nuclear pore complex. J Cell Biol. 1996;133:1153–1162. doi: 10.1083/jcb.133.6.1153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pemberton LF, Rout MP, Blobel G. Disruption of the nucleoporin gene NUP133 results in clustering of nuclear pore complexes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:1187–1191. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.4.1187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prasher DC. Using GFP to see the light. Trends Genet. 1995;11:320–323. doi: 10.1016/s0168-9525(00)89090-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rattner JB, Brinkley BR. Ultrastructure of mammalian spermiogenesis. II. Elimination of the nuclear membrane. J Ultrastruct Res. 1971;36:1–7. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5320(71)80084-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reichelt R, Holzenburg EL, Buhle EL, Jarnik M, Engel A, Aebi U. Correlation between structure and mass distribution of nuclear pore complex components. J Cell Biol. 1990;110:883–894. doi: 10.1083/jcb.110.4.883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ris H, Malecki M. High-resolution field emission scanning electron microscope imaging of internal cell structures after epon extraction from sections: a new approach to correlative ultrastructural and immunocytochemical studies. J Struct Biol. 1993;111:148–157. doi: 10.1006/jsbi.1993.1045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rout MP, Blobel G. Isolation of the yeast nuclear pore complex. J Cell Biol. 1993;123:771–783. doi: 10.1083/jcb.123.4.771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rout MP, Wente SR. Pore for thought: nuclear pore complex proteins. Trends Biochem Sci. 1994;4:357–363. doi: 10.1016/0962-8924(94)90085-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheer U, Kartenbeck J, Trendelen-Burg MF, Franke WW. Experimental disintegration of the nuclear envelope. J Cell Biol. 1976;69:1–18. doi: 10.1083/jcb.69.1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schimmang T, Tollervey D, Kern H, Frank R, Hurt EC. A yeast nucleolar protein related to mammalian fibrillarin is associated with small nucleolar RNA and is essential for viability. EMBO (Eur Mol Biol Organ) J. 1989;8:4015–4024. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1989.tb08584.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Severs NJ, Jordan EG, Williamson DH. Nuclear pore absence from areas of close association between nucleus and vacuole in synchronous yeast cultures. J Ultrastruct Res. 1976;54:374–387. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5320(76)80023-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherman F. Guide to yeast genetics and molecular biology. Getting started with yeast. Methods Enzymol. 1990;194:3–20. [Google Scholar]

- Siniossoglou S, Wimmer C, Rieger M, Doye V, Tekotte H, Weise C, Emig S, Segref A, Hurt EC. A novel complex of nucleoporins, which includes Sec13p and a Sec13p homolog, is essential for normal nuclear pores. Cell. 1996;84:265–675. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80981-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stotz A, Linder P. The ADE2 gene from Saccharomyces cerevisiae: sequence and new vectors. Gene. 1990;95:91–98. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(90)90418-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waddle JA, Karpova TS, Waterston RH, Cooper JA. Movement of cortical actin patches in yeast. J Cell Biol. 1996;132:861–870. doi: 10.1083/jcb.132.5.861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wente SR, Blobel G. A temperature-sensitive NUP116 null mutant forms a nuclear envelope seal over the yeast nuclear pore complex thereby blocking nucleocytoplasmic traffic. J Cell Biol. 1993;123:275–284. doi: 10.1083/jcb.123.2.275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wente SR, Blobel G. NUP145 encodes a novel yeast glycine-leucine-phenylalanine-glycine (GLFG) nucleoporin required for nuclear envelope structure. J Cell Biol. 1994;125:955–969. doi: 10.1083/jcb.125.5.955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wimmer C, Doye V, Grandi P, Nehrbass U, Hurt E. A new subclass of nucleoporins that functionally interacts with nuclear pore protein NSP1. EMBO (Eur Mol Biol Organ) J. 1992;11:5051–5061. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1992.tb05612.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zabel U, Doye V, Tekotte H, Wepf R, Grandi P, Hurt EC. Nic96p is required for nuclear pore formation and functionally interacts with a novel nucleoporin, Nup188p. J Cell Biol. 1996;133:1141–1152. doi: 10.1083/jcb.133.6.1141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]