Abstract

STAT transcription factors are induced by a number of growth factors and cytokines. Within minutes of induction, the STAT proteins are phosphorylated on tyrosine and serine residues and translocated to the nucleus, where they bind to their DNA targets. The leukemia inhibitory factor (LIF) mediates pleiotropic and sometimes opposite effects both in vivo and in cultured cells. It is known, for example, to prevent differentiation of embryonic stem (ES) cells in vitro. To get insights into LIF-regulated signaling in ES cells, we have analyzed protein-binding and transcriptional properties of STAT recognition sites in ES cells cultivated in the presence and in the absence of LIF. We have detected a specific LIF-regulated DNA-binding activity implicating the STAT3 protein. We show that STAT3 phosphorylation is essential for this LIF-dependent DNA-binding activity. The possibility that ERK2 or a closely related protein kinase, whose activity is modulated in a LIF-dependent manner, contributes to this phosphorylation is discussed. Finally, we show that the multimerized STAT3-binding DNA element confers LIF responsiveness to a minimal thymidine kinase promoter. This, together with our observation that overexpression of STAT3 dominant-negative mutants abrogates this LIF responsiveness, clearly indicates that STAT3 is involved in LIF-regulated transcriptional events in ES cells. Finally, stable expression of such a dominant negative mutant of STAT3 induces morphological differentiation of ES cells despite continuous LIF supply. Our results suggest that STAT3 is a critical target of the LIF signaling pathway, which maintains pluripotent cell proliferation.

The IL-6 cytokine family, including IL-6, leukemia inhibitory factor (LIF)1, ciliary neurotrophic factor, oncostatin M, and cardiotrophin-1, has wide pleiotropic effects on cell growth and differentiation. Signaling by these cytokines is transduced by activation of composite receptors that share the common gp130 subunit (26, 28, 40, 56). The structural diversity of these receptors and the cell type–dependent variability of expression of their subunits account, at least in part, for the specific and redundant functions of this class of hormones (11, 34, 52) . Characterization of the effectors of these cell signaling molecules is an essential step towards the elucidation of the mechanisms underlying the pleiotropic effects they mediate.

The gp130 protein and the LIF receptor β (LIFRβ) constitutively interact with the Jak1 and Jak2 tyrosine kinases. Activation of these kinases occurs as a result of LIF- induced dimerization of the receptor components (gp130-LIFRβ) and leads to their phosphorylation (22, 31, 34, 52, 53). Transcription factors from the STAT family can also be phosphorylated and recruited by the receptor, as shown in HepG2 cells treated with IL-6 (34). Different combinations of Jak kinases and STAT transcription factors are activated, depending on both the ligand and cell line (52). The members of the STAT family of transcription factors have first been described as effectors in the IFN-α/β and IFN-γ signaling pathways (25, 50). These dual-function factors, which contain SH2 and SH3 domains as well as a DNA-binding domain, are activated by growth factors (such as EGF and PDGF) and by cytokines (20, 50, 51). The STAT proteins are regulated by tyrosine and serine phosphorylation, a necessary step for dimerization, nuclear translocation, DNA-binding, and transcriptional activation (27, 59, 60). Tyrosine kinases of the Jak and of the Src families, as well as serine/threonine kinases of the mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinase family, have been involved in STAT regulation (7, 13, 14, 62, 64). The STAT3 transcription factor, originally cloned as an EGF- and IL-6–induced transcription factor, is activated in many cell types by a broad range of cytokines (1, 5, 12, 65). A natural truncated form of STAT3, named STAT3β, behaves as a constitutive transcription factor whose activity is synergized by association with Jun (48).

LIF plays a crucial role in vivo during preimplantation of mammalian embryos and is essential for the maintenance of the pool of hematopoietic stem cells (16, 54). Antagonistic effects of LIF on cultured cell lines are also well established: LIF inhibits differentiation of embryonic stem (ES) cells and, on the contrary, induces differentiation of other cell lines, such as the M1 myeloid cell line, the MAH sympathoadrenal progenitor cells, and the NBFL neuroblastoma cell line (6, 21, 29). LIF is also a potent activator of myoblast proliferation (36). Ciliary neurotrophic factor and oncostatin M also have the property to maintain the pluripotentiality of ES cells in vitro (9, 41, 43).

Characterization of the effectors of LIF in ES cells may provide insights into the mechanisms leading to early differentiation events in vitro. Thus, it would be of interest to determine whether similar proteins can be activated by LIF in cell lines in which this cytokine has opposite effects. The STAT3 transcription factor, which is phosphorylated on tyrosine upon LIF treatment in M1 myeloid cells, is also activated in ES cells maintained in the presence of LIF, but its specific effect on cell differentiation in ES cells has not been addressed (1, 23). It has been shown recently, however, that STAT3 is a critical factor involved in IL-6– and LIF-dependent differentiation of the M1 myeloid cell line (37, 38). Activation of MAP kinases by LIF has been reported, but its biological significance is yet unknown (15, 49, 61). Also, it has been shown that the low affinity LIF receptor subunit can be phosphorylated in vitro by the ERK2 serine/threonine kinase in the preadipocyte 3T3-L1 cell line. Phosphorylation of the LIF receptor, however, is not crucial for LIF signaling in these cells (49).

In this study, we demonstrate that the SIE DNA-binding site of the c-fos promoter, which is a target for STAT1/ STAT3 in EGF-treated cells (17, 65), is specifically bound by a STAT3-containing protein in ES cells maintained in the presence of LIF. We examine the expression and phosphorylation of the STAT3 protein in these cells in response to LIF treatment or withdrawal. We show that the c-fos promoter is LIF responsive in ES cells, and that the multimerized SIE element confers LIF-dependent transcription to the minimal TK promoter. We demonstrate that STAT3 mutants, which behave as dominant negative factors in the IL-6 pathway (38), can repress LIF-dependent transcription. We also show that stable expression of one of these mutants (STAT3F) leads to morphological differentiation of the ES cells. Finally, we present evidence that the ERK2 serine/threonine kinase is involved in the primary LIF response in ES cells.

Materials and Methods

Cells and Extracts

Embryonic cell lines were derived from the inner cell mass of mouse blastocysts as described (42). The cells were grown at 37°C, under 7% CO2, on gelatinized plates in DME supplemented with 15% FCS, 0.1 mM β-mercaptoethanol, and 1 mM sodium pyruvate. Recombinant murine LIF (∼1,000 U/ml) was added when appropriate. Where indicated, the cells were treated with 100 nM Staurosporine (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, MO), 27 μg/ml Genistein, or 1 μg/ml Herbimycin A (BIOMOL Research Laboratories, Plymouth Meeting, PA) for 20 h. Cytosolic and nuclear extracts were prepared as described (44).

Electrophoretic Band-Shift Assay

Gel retardation experiments were carried out in 20 μl final volume as described (44): 3 μg of nuclear extract was incubated with 1 μg of poly dI/dC for 10 min at 4°C; competitor oligonucleotides (100-fold molar excess with respect to probe) were added and further incubated for 10 min at 4°C. The 32P 5′ end-labeled probe (∼10,000 cpm, 5 fmol per reaction) was then added, and the mixture was incubated at 25°C for 15 min. The reactions were loaded on nondenaturing 4.5% polyacrylamide gels. After electrophoresis, the gels were dried and exposed for autoradiography.

For supershift experiments, nuclear lysates were preincubated with specific antibodies (see above): 1 μg of polyclonal anti-STAT1, 3, or 5, or 0.5 μg of monoclonal anti-STAT6, or antiphosphoserine, antiphosphothreonine, and antiphosphotyrosine. After 30 min at 4°C, the reactions were further processed as described above.

The synthetic, double-stranded oligonucleotides used as probes or competitors in the band-shift reactions were as follows (only one strand is represented, with the binding region italicized and mutations underlined):

SIE, high affinity binding site of the c-fos promoter element (SIE67; [58]): 5′ AGCTTCATTTCCCGTAAATCCCTA 3′.

mutated SIEm (SIE25; [58]): 5′ AGCTTCAGATCCCGTCATTCCCTA 3′.

ISRE, IFN-α–stimulated response element from the ISG54 gene promoter (11): 5′ AGCTAGTTTCACTTTCCC 3′.

GAS, IFN-γ activation site from the guanylate binding protein gene (11): 5′ AGCTTTACTCTAATTTCCC 3′.

APRE, STAT3 high affinity binding site repeated twice (1): 5′ ATCCTTCCGGGAATTCTGATCCTTCCGGGAATTCTG 3′.

ATF, ATF-binding site of the adenovirus-2 E2aE promoter (position −65/−84) (63): 5′ TCGGGAAAACTACGTCATCTCCAGC 3′.

Antibodies and Immunoreactions

The polyclonal anti-STAT1 (directed against residues 688–710), anti-STAT3 (against residues 750–769), anti-STAT5 (against residues 5–24), and anti-ERK2 (against residues 345–358) antibodies were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA); the monoclonal anti-STAT3 (against residues 1–172) and anti-STAT6 antibodies (against residues 1–272) were provided by Transduction Laboratories (Lexington, KY); the antiphosphoserine, antiphosphothreonine, and antiphosphotyrosine antibodies used in the band-shift assays were from Sigma Chemical Co. The antiphosphotyrosine antibody used in immunoprecipitation experiments (supernatant of the 4G10 hybridoma) was a gift from D. Morrison. D.K. Morrison (National Cancer Institute, Frederick Cancer Research and Development Center, Frederick, MD).

Total cell extracts (100 μg) were immunoprecipitated with 100 μl of the 4G10 antiphosphotyrosine antibody in the presence of protein A–Sepharose beads (Pharmacia Fine Chemicals, Piscataway, NJ) for 2 h at 4°C. The beads were washed twice in TBStg buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 125 mM NaCl, 1% Tween 20, 10% glycerol) and were resuspended in protein gel loading buffer.

About 20 μg of nuclear or cytosolic extracts from ES cells were electrophoresed on 10% acrylamide/SDS gels. Proteins were transferred onto nitrocellulose membranes and incubated with specific antibodies as recommended by the manufacturers. Protein–antibody complexes were visualized by an enhanced chemiluminescence detection system (Amersham Corp., Arlington Heights, IL).

In Vitro Kinase Assay

About 150 μg of nuclear or cytosolic extracts were immunoprecipitated with 0.8 μg of the anti-ERK2 antibody in the presence of protein A-Sepharose beads (Pharmacia Fine Chemicals) for 2 h at 4°C. The beads were washed twice in TBStg buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 127 mM NaCl, 1% Tween 20, 10% glycerol), once in kinase buffer (20 mM Hepes, pH 7.4, 5 mM EGTA, 10 mM MgCl2, 10 mM β-glycerol-phosphate, 10% glycerol), and finally resuspended in 20 μl of kinase buffer supplemented with 20 μM ATP, 1 μCi[32P]γ-ATP, and 20 μg myelin basic protein (Sigma Chemical Co.). After incubation for 30 min at 30°C, the reactions were stopped in SDS sample buffer, and electrophoresed on a 10% acrylamide/ SDS gel, and processed for autoradiography.

Expression Vectors

Synthetic oligonucleotides corresponding to the high affinity wild-type (SIE67) or mutated (SIE25) SIF-binding sites (58) were trimerized and inserted into the SalI site of the pBLCAT5 vector (3), upstream of the minimal thymidine kinase (TK) promoter, generating the (SIE)3-TK and (SIEm)3-TK CAT reporter vectors, respectively.

The c-Fos CAT vector bearing the human c-fos promoter sequences between positions −711 and +42 has been described previously (FC3 recombinant [46]).

The pEF-BOS and pCAGGS-Neo series of STAT3 recombinants have been described previously (38): pEF-BOS HA-STAT3 and pCAGGS-Neo-HA-STAT3 encode the hemagglutinin (HA)-tagged wild-type murine STAT3 protein; pEF-BOS HA-STAT3F and pCAGGS-Neo-HA-STAT3F encode a mutant version of STAT3 in which residue Y705 has been replaced by a phenylalanine (F); pEF-BOS HA-STAT3D encodes a STAT3 mutant in which residues E434 and E435 of the DNA-binding domain have been changed to aspartates (D).

Transfection Assay

ES cells, plated the day before in the presence or absence of LIF, were transfected by calcium phosphate coprecipitation (8) with 2 or 5 μg of recombinant DNA vectors adjusted to 20 μg/9-cm petri plate, with the promoterless pBLCAT6 plasmid (3) used as carrier. 20 h after transfection, the cells were washed once with PBS, and fresh medium, with or without LIF, was added. The day after, the cells were harvested and extracts prepared in buffer A (15 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8, 60 mM KCl, 15 mM NaCl, 2 mM EDTA, 0.15 mM spermine, 1 mM DTT, and 1 mM Pefabloc). Aliquots, normalized by protein concentration, were assayed for CAT activity as described (19). The percentage of chloramphenicol acetylation was determined from at least three independent experiments and was quantitated with a Bioimaging analyzer (Fuji Photo Film Co., Tokyo, Japan).

Selection of Stably Transformed Cells

To establish stable ES cell clones that produce the wild-type STAT3 or mutated STAT3F proteins, ES cells, maintained on feeder cells in LIF-containing medium, were transfected with the pCAGGS-Neo-HA-STAT3 and pCAGGS-Neo-HA-STAT3F vectors (38). After 10 d of selection, in the presence of 400 μg/ml of G418, individual clones were recovered and plated on fresh feeder cells in LIF-containing medium. The medium was changed every other day, and cells were divided every 4 d. Morphological differentiation of the clones overexpressing STAT3F becomes apparent after the third passage of the clones (i.e., ∼4 wk after transfection).

Results

A LIF-dependent DNA-binding Activity is Present in ES Cells

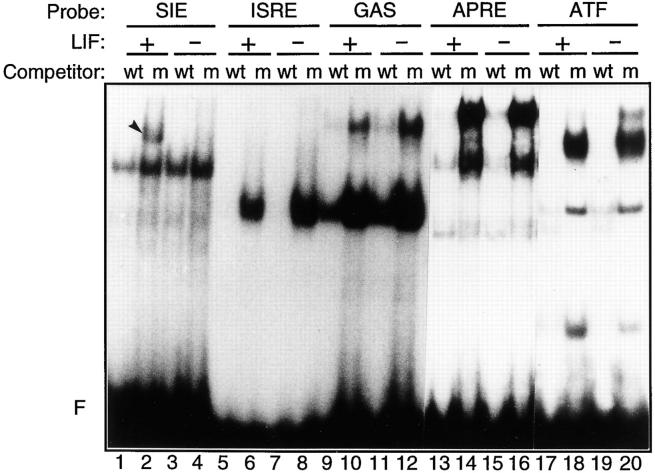

To identify LIF-regulated DNA-binding activities, nuclear lysates prepared from ES cell cultures that were constantly maintained in the presence of LIF or from which LIF was withdrawn for 12 h were used in band-shift experiments on selected protein-binding sites (Fig. 1). Among the five probes chosen, four corresponded to STAT-binding sites (SIE, ISRE, GAS, and APRE), and one (ATF) was unrelated (11, 63). A major LIF-dependent DNA-binding activity was detected on the SIE probe, as revealed by specific complex formation in LIF-treated ES cell extracts (Fig. 1, lane 2) compared to extracts from LIF-withdrawn cells (Fig. 1, lane 4). By contrast, the specific complexes detected with the other probes were not affected by the LIF treatment. This result indicates that LIF mediates the binding of specific proteins to the SIE element in ES cells.

Figure 1.

A LIF-dependent DNA-binding activity is detected in ES cells. Nuclear extracts from ES cells constantly maintained in the presence of LIF (+) or grown in the absence of LIF for 12 h (−) were used in standard band-shift assays with the 5′ end- labeled SIE, ISRE, GAS, APRE, or ATF probes as indicated (see Materials and Methods). A 100-fold molar excess of each corresponding unlabeled wild-type oligonucleotide (wt) or of the mutated SIE oligonucleotide (m) was added as competitor to the binding reactions. F, the unbound probe. The arrowhead in lane 2 points to the LIF-regulated complex.

The DNA-binding Activity of the LIF-regulated Complex May Be Involved in the Control of Cell Proliferation

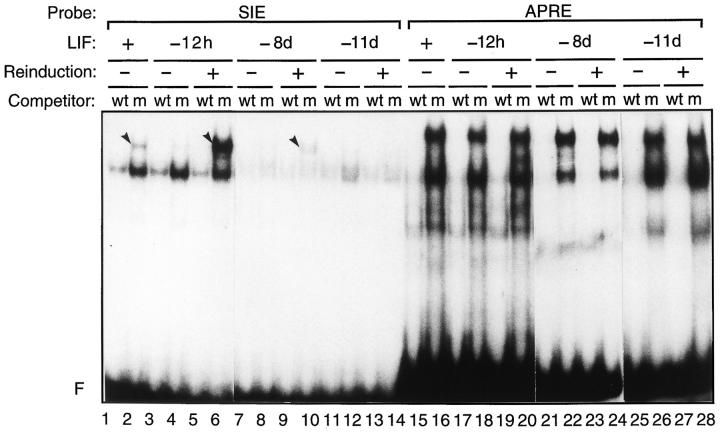

LIF plays a key role in the maintenance of the pluripotential phenotype and active proliferation of ES cells (6, 21). We wondered whether induction of the LIF-dependent DNA-binding activity is linked to the proliferative function mediated by LIF in these cells. If the DNA-binding activity drops as a result of early differentiation commitment after a 2–3 d LIF withdrawal, no recovery of specific complex formation would occur after LIF reinduction. By contrast, if this binding activity is involved in cell growth control, it should be reinduced by short treatments with LIF in cells that can still proliferate. To test this possibility, we used the LIF-regulated SIE- and nonregulated APRE-binding sites as probes in band-shift experiments with nuclear extracts from ES cells that had been grown in the absence of LIF for increasing time periods and treated by LIF for 10 min before cell harvesting. As shown in Fig. 2, specific DNA-binding activity on the SIE was recovered after a 10-min LIF reinduction, following a 12-h LIF deprivation (Fig. 2, lane 6). As reflected by the intensity of the retarded complex, the binding activity is much stronger after LIF reinduction than in cells that had been grown in the continuous presence of LIF (Fig. 2, compare lanes 2 and 6). Efficient complex reinduction also occurred 4 d after LIF withdrawal (not shown). Reinduction was much weaker after 8 d of LIF deprivation (Fig. 2, lane 10), and became undetectable after 11 d (Fig. 2, lane 14), a stage at which the cell growth rate was reduced dramatically. By contrast, no major modulation of the DNA-binding activities was detected on the APRE probe (Fig. 2, lanes 15–28). Altogether, these results suggest that the DNA-binding activity detected on the SIE probe is part of the proliferative signal mediated by LIF, and that modulators of this activity are still present in ES cells during the first week after differentiation commitment.

Figure 2.

The LIF-dependent DNA-binding complex is reinducible by LIF up to 8 d without LIF. Nuclear extracts were prepared from ES cells that were maintained with LIF or without LIF for 12 h and 8 or 11 d (−12h, −8d, or −11d, respectively) and reinduced with LIF for 10 min where indicated. Standard band-shift assays were run with the 5′ end-labeled SIE or APRE probes in the presence of wild-type (wt) or mutant (m) SIE competitors, as indicated. The arrowheads refer to the LIF-regulated complexes.

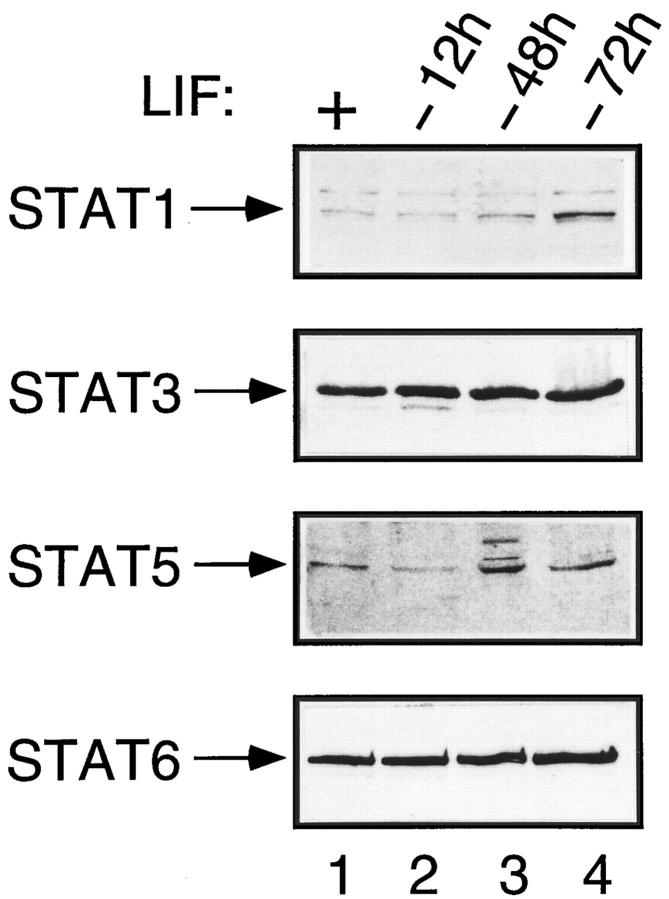

The Steady-state Level of STAT Proteins in ES Cells Is Not Dependent on LIF Treatment

We next examined the presence of STAT proteins in ES cells and determined their overall levels as a function of LIF treatment. To this end, nuclear lysates from cells that had been maintained in the presence of LIF or cultivated in its absence for increasing time periods were analyzed by immunoblotting with specific STAT antibodies. As seen in Fig. 3, STAT1, 3, 5, and 6 were readily detected in ES cells, and their respective amounts were not affected significantly by LIF withdrawal: the level of each of these proteins remained unchanged, even after growing the ES cells in the absence of LIF for 3 d, a time at which morphological differentiation of ES cells became apparent.

Figure 3.

STAT protein expression remains constant in the presence and absence of LIF. Nuclear extracts were prepared from ES cell cultures that were maintained in the presence of LIF (+) or those from which LIF was removed for 12, 48, or 72 h, as indicated. Immunoblot analyses were performed with specific anti-STAT antibodies, as described in Materials and Methods.

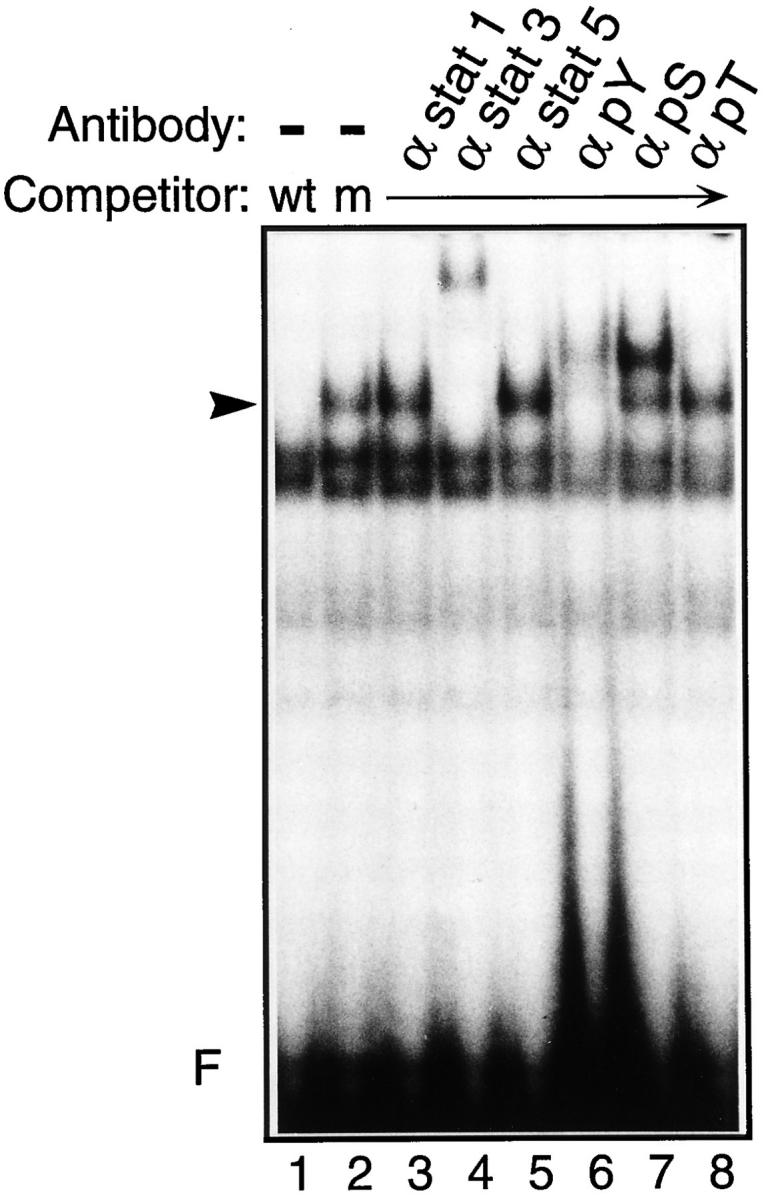

The LIF-regulated Complex Comprises a Phosphoprotein Immunologically Related to STAT3

To determine which member of the STAT family generates the LIF-regulated complex detected in ES cells, we examined the effect of antibodies specifically directed against different STAT proteins. As shown in Fig. 4, only the STAT3 antibody produced a clear supershift of the LIF-dependent complex with the SIE probe (Fig. 4, lane 4), whereas antibodies to STAT1 (Fig. 4, lane 3), STAT5 (Fig. 4, lane 5), or STAT6 (not shown) had no effect on this complex. Interestingly, the LIF-regulated complex was supershifted only by an antibody directed against the COOH-terminal part (residues 750–769) of STAT3α (Fig. 4, lane 4), but not by an antibody directed against residues 628–640 (not shown) that recognizes both STAT3α and STAT3β (48). It is possible therefore that this latter epitope is hidden within the folded molecule or by association with yet unknown proteins. Similar experiments with the APRE probe revealed that none of these antibodies could supershift any of the specific retarded complexes (not shown), further stressing the specificity of the LIF- dependent complex assembled on the SIE site.

Figure 4.

The LIF-dependent complex contains a STAT3-related protein and is phosphorylated both on tyrosine and serine residues. Nuclear extracts from ES cells maintained in the presence of LIF were preincubated for 30 min with 1 μg of anti-STAT1, anti-STAT3, or anti-STAT5 (α stat 1, α stat 3, or α stat 5, respectively), or with 0.5 μg of the antiphosphotyrosine, antiphosphoserine, or antiphosphothreonine (α pY, α pS, or α pT, respectively), as indicated. Standard band-shift assays were then performed with the 5′ end-labeled SIE probe and wild-type (wt) or mutant (m) SIE competitors, as indicated. The arrowhead points to the position of the LIF-dependent complex.

When nuclear lysates were prepared in the absence of phosphatase inhibitors (like sodium vanadate or sodium fluoride), formation of the LIF-dependent complex was impaired (not shown), suggesting that phosphorylation of this complex was important for its DNA-binding activity. To examine this possibility in further detail, we tested the effect of antibodies directed against phosphorylated amino acids on specific complex formation. Antibodies against phosphotyrosine (Fig. 4, lane 6) and phosphoserine (Fig. 4, lane 7) supershifted the LIF-specific complex, whereas antiphosphothreonine antibodies had no effect (Fig. 4, lane 8). In agreement with the earlier finding that STAT proteins are rapidly phosphorylated on serine and tyrosine residues after cytokine or growth factor treatment (50, 60, 64), this result strongly suggests that the STAT3-containing complex is phosphorylated on these residues within the LIF-regulated complex.

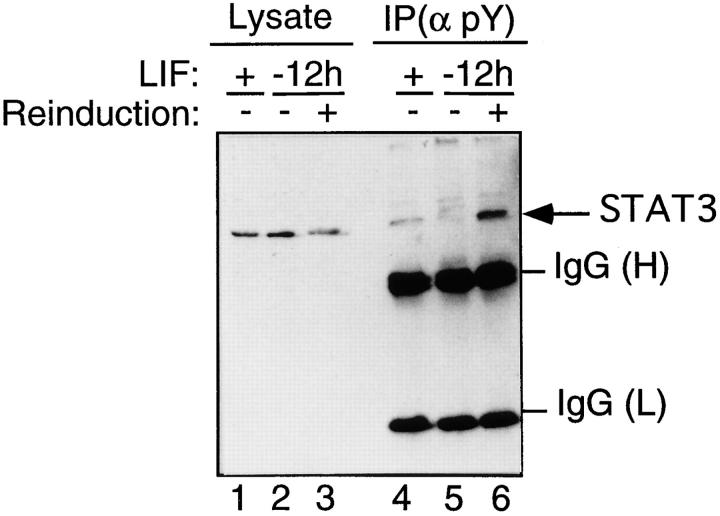

STAT3 Is Present in Tyrosine-phosphorylated Complexes Only upon LIF Treatment

To determine if STAT3 is present in a tyrosine-phosphorylated complex in LIF-treated ES cells, we have performed immunoprecipitation experiments with the 4G10 antiphosphotyrosine antibody. Western blot analysis of the tyrosine-phosphorylated immune complexes is shown in Fig. 5. STAT3 protein is detected in tyrosine-phosphorylated complexes only in LIF-treated cells, with a higher pool of STAT3 protein in LIF-reinduced cells, compared to cells continuously maintained in the presence of LIF (Fig. 5, compare lanes 4 and 6). Phosphorylation of the STAT3 complex correlates with its DNA-binding activity (Fig. 2, compare lanes 2, 4, and 6).

Figure 5.

STAT3 is present in tyrosine-phosphorylated complexes only upon LIF treatment. Whole-cell extracts were prepared from ES cells that were maintained with LIF (+) or without LIF for 12 h (−12h) and reinduced or not with LIF for 10 min, as indicated. The extracts (20 μg) were loaded, either directly (Lysate) or after immunoprecipitation with the antiphosphotyrosine antibody [IP(α pY)], on SDS-polyacrylamide gels, and were analyzed with the anti-STAT3 antibody. Arrows point to bands corresponding to STAT3. The heavy (H) and light (L) chains of the anti-pY Igs are also revealed.

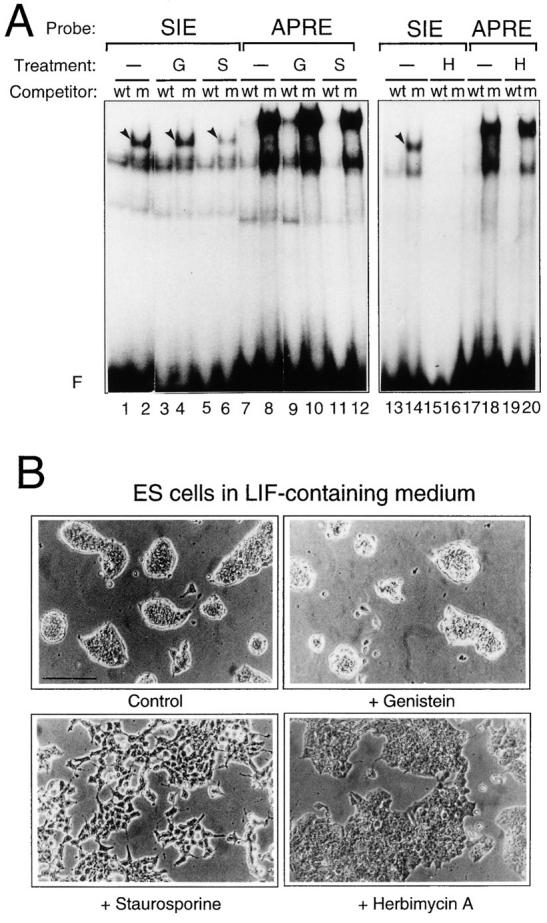

Protein Kinase Inhibitors Impair the DNA-binding of the LIF-dependent STAT3 Complex and Alter Cell Morphology

We next examined the dependence of the LIF-induced complex on protein phosphorylation. ES cells, maintained in the presence of LIF, were treated for 20 h with specific tyrosine kinase inhibitors (Genistein and Herbimycin A) or with a more general protein kinase inhibitor (Staurosporine; 2, 32, 47 and references therein). As shown in Fig. 6 A, Genistein treatment did not prevent specific complex formation (Fig. 6 A, compare lanes 2 and 4). Control experiments have been performed in the epidermoid A 431 cell line treated with EGF, in which the formation of the STAT1/STAT3 heterodimeric complex is completely abolished by Genistein, as expected from earlier studies (17, 45; data not shown). By contrast, treatment of the cells with Herbymicin A completely abolished formation of the STAT3-containing complex (Fig. 6 A, compare lanes 14 and 16). In the presence of Staurosporine, formation of the LIF-dependent complex was also severely impaired (Fig. 6 A, lane 6). No detectable effect was observed on the APRE-specific complexes in the presence of either inhibitor (Fig. 6 A, lanes 7–12 and 17–20). Together with the effect of the antibodies against specific phosphorylated amino acids, these results indicate that phosphorylation of the STAT3-containing complex on serine and tyrosine residues is essential for its competence to bind DNA.

Figure 6.

LIF-dependent complex is sensitive to Staurosporine and Herbimycin A. (A) The 5′ end-labeled SIE or APRE probes were used in the presence of wild-type (wt) or mutant (m) SIE competitors in standard band-shift assays with nuclear extracts derived from ES cells maintained with LIF and treated for 20 h with 27 μg/ml of Genistein (G), 100 nM Staurosporine (S), or 1 μg/ml Herbimycin A (H) when indicated. Arrowheads point to the LIF-regulated complexes. (B) Phase contrast micrographs of ES cells treated or not (control) with the different kinase inhibitors. Bar, 40 μm.

We have also observed that ES cells treated with Staurosporine and Herbimycin A undergo striking changes in their morphology reminiscent of alterations that occur during cell differentiation (see Fig. 6 B). In the presence of these inhibitors, cells no longer grow as clumps characteristic of undifferentiated cells, but become flattened in the presence of Herbimycin A and are completely individualized in the presence of Staurosporine. This result suggests that impairment of the formation of the STAT3-dependent complex may lead to morphological cell differentiation.

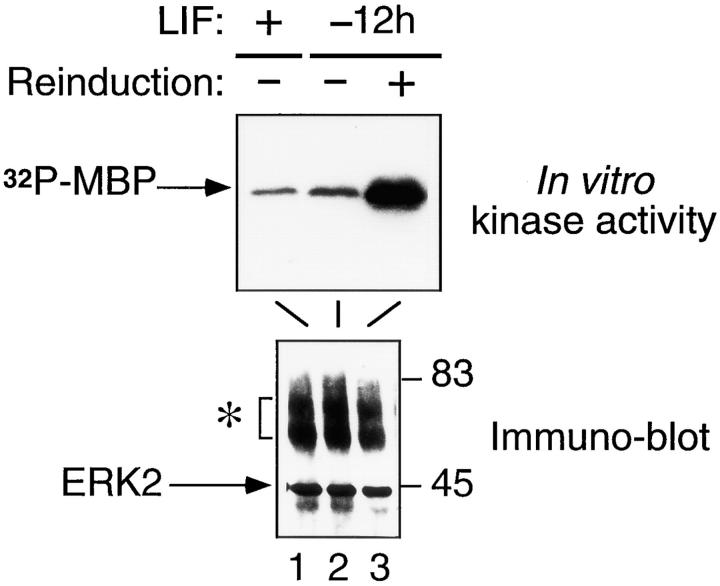

The ERK2 Serine/Threonine Kinase Activity Is Induced by LIF

The ERK2 serine/threonine kinase has recently been shown to interact with STAT1 in IFN-α/β–induced cells (13). Similarly, serine/threonine kinases of this family play critical roles during the differentiation of PC12 cells (35). In addition, it has been shown that LIF stimulates ERK2 activity in 3T3 fibroblasts (49, 61). We tested the possibility that ERK2 is associated with STAT3 in ES cells, and determined the activity of this particular kinase as a function of LIF treatment. Nuclear and cytoplasmic extracts from ES cells cultivated in the presence or absence of LIF for 12 h and reinduced by LIF for 10 min were immunoprecipitated with an anti-ERK2 antibody. As revealed by immunoblot analysis (Fig. 7), the level of ERK2 remained constant in ES cells whether they were treated or not with LIF. Under our immunoprecipitation conditions, neither STAT1 nor STAT3 were found to be associated with the ERK2 kinase in the different cell lysates (not shown). Similarly, ERK2 could not be detected in STAT3 immunoprecipitates (not shown), indicating that no stable interactions exist between these proteins in ES cells and, if they do exist, that such interactions occur only transiently. The in vitro kinase activity, as measured by phosphorylation of the exogenous MBP substrate, was not significantly affected by LIF withdrawal (Fig. 7, lanes 1 and 2). When these cells were reinduced by LIF for 10 min before extract preparation, however, a strong increase in ERK2 kinase activity was reproducibly observed. Very similar results were obtained whether ERK2 was analyzed in nuclear (Fig. 7) or in cytoplasmic (not shown) extracts. These results indicate that ERK2 is modulated in a LIF-dependent manner in ES cells without altering its subcellular distribution. In agreement with the more efficient complex formation after LIF reinduction after 12 h (see Fig. 2, lane 6) they also suggest that ERK2 or a closely related serine/threonine kinase may be part of the primary signal mediated by LIF in these cells.

Figure 7.

An ERK2-related MAP kinase is activated in ES cells reinduced by LIF. Nuclear extracts from ES cells maintained with LIF or without LIF for 12 h (−12h) and reinduced by LIF for 10 min, as indicated, were immunoprecipitated with the anti-ERK2 antibody, as described in Materials and Methods. Two thirds of the reaction were assayed in an in vitro kinase assay using MBP as an exogenous substrate (top). The remaining third of the reaction was analyzed by immunoblot with the anti-ERK2 antibody (bottom). The asterisk refers to the heavy chains of the Igs. Numbers on the right-hand side indicate the position of protein size markers (kD).

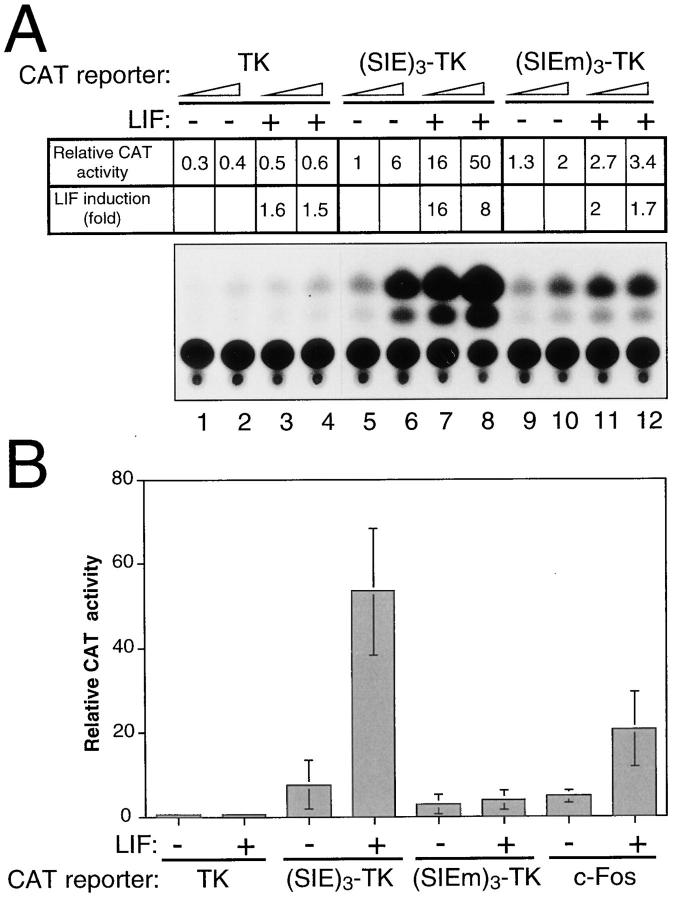

Multimerized SIE Elements Confer LIF Responsive Transcriptional Activity to Chimeric Promoters in ES Cells

Multimerized STAT-binding elements have previously been shown to behave as cytokine-inducible elements when inserted upstream of a minimal promoter (33). We examined whether formation of the LIF-dependent complex on the SIE element could be correlated, in the context of ES cells, with the transcriptional activation of a reporter gene harboring this element.

To this end, ES cells cultivated in the absence or presence of LIF were transfected with chloramphenicol acetyl transferase (CAT) reporter plasmids differing in their promoter elements. The results of a typical CAT analysis is shown in Fig. 8 A, along with the mean values of similar independent experiments (Fig. 8 B). It clearly appears that the high-affinity SIE element, when linked as a trimer to the minimal TK promoter [(SIE)3-TK], confers LIF responsiveness to the CAT reporter. The specificity of these results was further substantiated by the observation that, under the same conditions, the TK promoter, whether alone or fused to a mutated SIE element [(SIEm)3-TK], showed no or very low LIF-responsiveness. Interestingly, insertion of a single SIE element in front of the TK promoter did not generate a LIF-responsive construct (not shown, [33]), while in the context of the natural c-fos promoter, a single low-affinity SIE element (present at position −346), was sufficient to confer LIF responsiveness to a c-Fos CAT reporter (Fig. 8 B). This observation stresses the importance of the relative position of the SIE element with respect to the start site or to the surrounding promoter elements. It is possible, therefore, that trimerization of the SIE element, as in the (SIE)3-TK CAT construct, somehow compensates for the artificial structure of this synthetic promoter.

Figure 8.

The SIE element confers LIF responsiveness to a heterologous promoter in ES cells. (A) ES cells maintained with (+) or without (−) LIF were transfected with 2 (odd lanes) or 5 μg (even lanes) of the CAT reporters: pBLCAT5 (referred to as TK), (SIE)3-TK, and (SIEm)3-TK, as indicated. The results of a typical CAT assay with corresponding quantification are presented. (B) Transfection experiments were performed as described above, but using 5 μg of each of the indicated CAT reporters and including the c-Fos CAT reporter. The mean (±SD) of four independent experiments performed with different plasmid preparations is plotted.

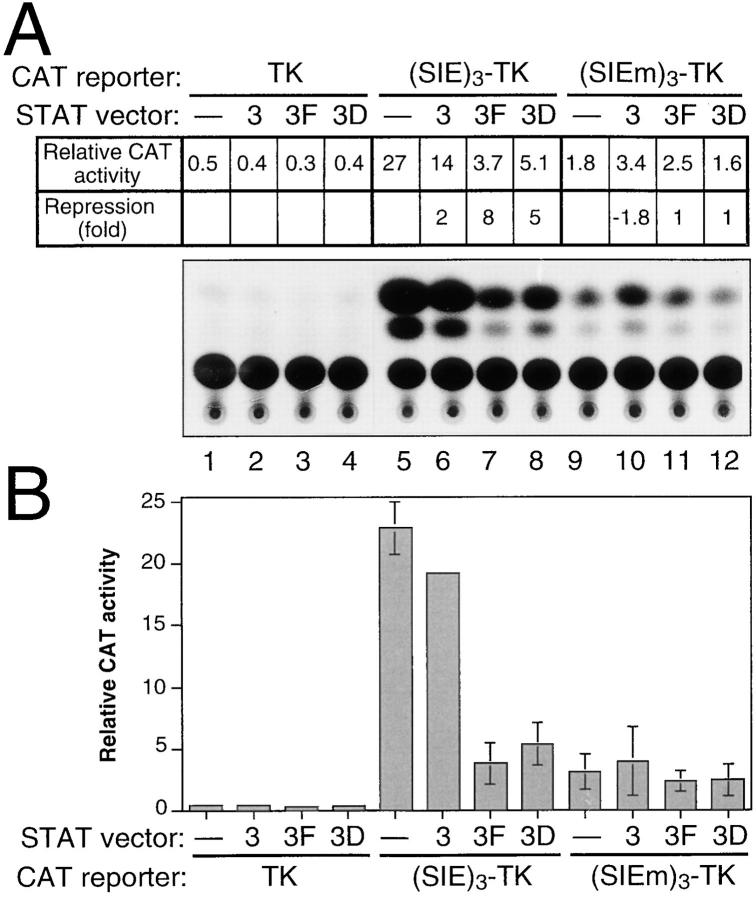

STAT3 Is a Key Mediator of the LIF-regulated Transcription in ES Cells

To further investigate the contribution of STAT3 to LIF responsiveness, we attempted to compete for the endogenous protein by overexpressing STAT3 dominant negative mutants in ES cells. We used STAT3 vectors (STAT3F, in which residue Y705 has been mutated to phenylalanine, and STAT3D, in which two critical residues in the DNA-binding domain, E434 and E435, have been changed to alanine [24]) whose expression had previously been shown to impair IL-6–dependent transcription and cell differentiation (38). These vectors were transfected into ES cells maintained in the presence of LIF, together with the LIF-responsive or nonresponsive CAT reporters. The results of a typical CAT analysis are shown in Fig. 9 A, along with the compiling of the results of similar independent experiments (Fig. 9 B). As expected from Fig. 8, the LIF-responsive (SIE)3-TK promoter exhibited the highest reporter activity when transfected with the empty STAT vector (Fig. 9, lane 5 and corresponding column). Coexpression of the wild-type STAT3 protein (“3”) had no significant effect on this reporter activity (Fig. 9, compare lanes 5 and 6 and corresponding columns), although slight variations were observed from one experiment to the other, probably reflecting fluctuations of the pool of active STAT3 in the transfected cells. Under conditions where nearly identical amounts of recombinant STAT3 proteins were produced (as monitored by Western blot analysis, not shown), coexpression of the mutant STAT3 proteins severely repressed the LIF-dependent reporter activity (Fig. 9, lanes 7 and 8 and corresponding columns), whereas it had virtually no effect on basal reporter activity (Fig. 9, compare lanes 1–4 and 9–12 and corresponding columns). These results clearly support the conclusion that STAT3 mediates LIF-dependent transcriptional activation in ES cells.

Figure 9.

Dominant negative mutants of STAT3 negatively interfere with LIF-dependent promoter activity. (A) ES cells maintained with LIF were cotransfected with 5 μg of the CAT reporters [pBLCAT5 (referred to as TK), (SIE)3-TK, and (SIEm)3-TK], together with 3 μg of the empty pEF-BOS vector (lanes 1, 5, and 9), the pEF-BOS HA-STAT3 (lanes 2, 6, and 10), the pEF-BOS HA-STAT3F (lanes 3, 7, and 11), or the pEF-BOS HA-STAT3D (lanes 4, 8, and 12), as indicated. The results of a typical CAT assay with corresponding quantification are presented. (B) The mean (±SD) of three independent experiments performed as described above, with different plasmid preparations, is plotted. Depending on the experiment, cotransfection of the (SIE)3-TK CAT reporter with the pEF-BOS HA-STAT3 vector resulted either in a slight stimulation or slight repression of CAT activity compared to cotransfection with the empty pEF-BOS vector. This variation, probably reflecting differences in recipient cell conditions, generated artificially elevated SD values: the misleading error bar was therefore omitted on the corresponding column.

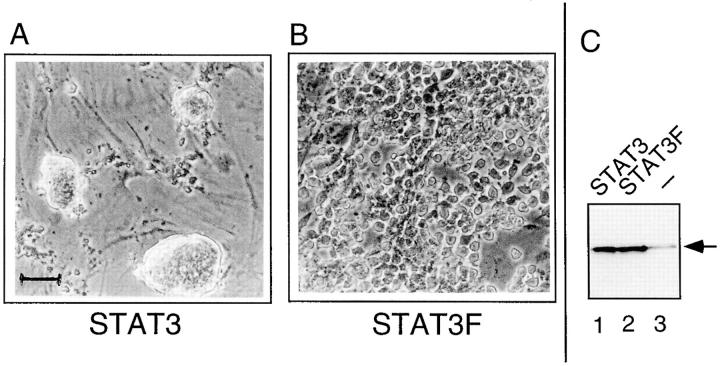

Stable Expression of a Dominant-Negative STAT3 Mutant Induces ES Cell Differentiation in the Presence of LIF

If, as suggested by the experiments described above, STAT3 is an essential intermediate in LIF signaling in ES cells, the expression of a dominant-negative allele that blocks the effect of the endogenous STAT3 should impair the action of LIF and thereby allow the cells to differentiate. To examine this possibility, we established ES cell lines that were stably transformed with vectors expressing either the wild-type STAT3 sequence or the dominant-negative mutant STAT3F. Both constructs generated neomycin-resistant clones with similar efficiencies. 10 clones of each type were picked, and STAT3 and STAT3F expression levels were examined by Western blot analysis: all clones overexpressed the STAT3 proteins compared to untransfected cells. The cells overexpressing STAT3F, however, had a much greater propensity to differentiate than the STAT3 transformants, although they were grown under identical conditions, on feeder cells and in the presence of LIF. Specifically, 1 mo after the transfection and selection procedure, all STAT3F-transformed ES cells had undergone morphological differentiation, whereas <5% of the STAT3-transformed cells exhibited an altered morphology. As expected, the clones exhibiting the highest levels of STAT3F expression were the first to differentiate. A typical analysis with two clones, one of each type, is shown in Fig. 10. These results clearly indicate that the STAT3 protein is chiefly involved in the keeping of ES cell pluripotentiality.

Figure 10.

Stable expression of STAT3F dominant negative mutant induces ES cell differentiation. Phase contrast micrographs of Neomycin-resistant ES cell clones stably expressing the wild-type STAT3 (A) or the dominant negative STAT3F mutant (B). The selected clones were grown on feeder layers of mouse embryo fibroblasts (visible in A between the clumps of undifferentiated ES cells) and continuously maintained in the presence of LIF. (C) Western blot analysis of equivalent amounts of whole-cell extracts of STAT3- (lane 1) or STAT3F-transformed cells (lane 2), or untransformed ES cells (lane 3). The arrow points to the specific signal obtained with the monoclonal anti-STAT3 antibody. Bar, 100 μm.

Discussion

The LIF cytokine plays a key role in the maintenance of the pluripotential phenotype and proliferation of ES cells in vitro. We have investigated how the LIF regulates the specific binding and transcriptional properties of a STAT3-based complex in ES cells. We present evidence suggesting that phosphorylation of this complex is the primary response of LIF-induced cell proliferation, and we demonstrate that STAT3 is a critical component of LIF-dependent transcription in ES cells.

In an earlier study, Hocke et al. (23) detected a LIF- inducible DNA-binding activity on the IL-6 response element of the rat α2-macroglobulin (α2 M) gene and showed that STAT3 is part of this complex. These authors also demonstrated that the downregulation of the LIF receptor in LIF-deprived cells correlates with the loss of the LIF-dependent complex. Similarly, we show that the DNA-binding activity detected on the SIE probe dropped rapidly after LIF deprivation. We further extend this observation by showing that regulators which activate STAT3 DNA-binding capacity remain reinducible by the LIF within the first week of LIF deprivation. The extent of reinduction decreases progressively, however, together with the slackening of cell growth.

Inhibition of STAT3 Phosphorylation Correlates with the Loss of DNA-binding Activity and with Morphological Alterations of ES Cells

We have shown that the level of the STAT3 protein remains constant in ES cells whether or not they were treated with LIF, but that tyrosine-phosphorylated complexes containing STAT3 are detected only in the presence of LIF. Our data demonstrate that DNA-binding activity correlates with phosphorylation on tyrosine and with the activation of the ERK2 serine/threonine kinase, whose activity is dependent on tyrosine phosphorylation (39, 57). Two lines of evidence suggest that ERK kinases may phosphorylate STAT3 despite the fact that we could not visualize any interaction between STAT3 and ERK2 (not shown): (a) the sensitivity of the STAT3-containing complex to Herbimycin A, a potent inhibitor of tyrosine kinases that alters MAP kinase function in vivo; and (b) the finding that Ras, a known MAP kinase inducer, is involved in LIF signaling in ES cells (15, 47, 61). We did not detect any significant alteration in the relative nuclear and cytoplasmic distribution of ERK2 after LIF treatment. This is in contrast to PC12 cells, in which sustained MAP kinase activation by NGF leads to the nuclear translocation of the kinase and to cell differentiation, whereas upon short-lived activation by EGF, which triggers cell proliferation, the kinase remains essentially cytosolic (35). The differentiation program, which settles in ES cells in the absence of LIF, may therefore not require relocation of ERK2 in different cell compartments. On the other hand, the possibility that a distinct but related protein kinase(s) is implicated in ES cells cannot be formally excluded.

The tyrosine kinases of the Jak and Src families involved in gp130-dependent signaling are also potential candidates for STAT3 phosphorylation (14, 34, 52). In fact, members of these families of tyrosine kinases play essential roles in ES cells: clones of ES cells that overexpress the oncogenic form of the v-Src protein exhibit LIF-independent growth (4); the Hck tyrosine kinase is activated upon LIF signaling in ES cells, and LIF requirement decreases in cells that constitutively express an activated form of Hck (14); the activity of JAK1 and JAK2 tyrosine kinases is induced upon LIF treatment in ES cells, and it has been suggested that Hck and Jak kinases induce two alternative LIF- dependent pathways (15). Our experiments suggest that STAT3 is probably a common target of both pathways, with MAP kinases playing an essential role during the LIF reinduction process.

Interestingly, in cells treated with Staurosporine, a general kinase inhibitor known to block cells in both G1 and G2-M phases (32), formation of the STAT3-dependent complex is impaired, and the cells undergo morphological changes that mimic cell differentiation. Similarly, in cells treated with Herbimycin A, a drug that blocks mainly the activity of cytoplasmic tyrosine kinases (47), there is also a correlation between the disappearance of the STAT3-containing complex and an alteration in cell morphology. These results suggest that LIF-dependent STAT3 activation is linked to the maintenance of ES cell pluripotentiality, a conclusion that is further substantiated by the observation that overexpression of the STAT3F dominant negative mutant in ES cells triggers their morphological differentiation in the presence of LIF.

The STAT3 Transcription Factor Is a Key LIF-signaling Intermediate

STAT3 is induced by IL-6 and LIF during myeloid cell differentiation. The impairment of STAT3 signaling by expression of dominant-negative mutants of STAT3 (STAT3F and STAT3D) leads to transcriptional repression and affects the differentiation program in these cells (37, 38). These mutants prevent proper tyrosine phosphorylation of the endogenous STAT3 protein, probably by blocking the wild-type protein's access to the gp130 receptor (37, 38). Repression of IL-6–dependent transcription has also been reported in HepG2 cells expressing the STAT3F mutant (30). We show that STAT3F and, to a lesser extent, STAT3D repress LIF-dependent transcription in ES cells. These data, together with results obtained with the kinase inhibitors, clearly emphasize the critical contribution of the tyrosine Y705 residue of STAT3 (a residue that is phosphorylated upon STAT3 activation) to STAT3 transcriptional efficiency.

Differential Behavior of STAT3 Recognition Sites

The APRE-binding site is a STAT3 recognition element that has originally been used to purify STAT3α from the rat liver (1). In our study, the APRE-specific complexes are not modulated by LIF, and their formation is not altered in lysates derived from cells treated with kinase inhibitors. In addition, as opposed to the (SIE)3-TK-CAT and of the c-fos–CAT reporter activities, the APRE-TK-CAT reporter activity was not responsive to LIF treatment (not shown). Interestingly, these APRE-specific complexes were not supershifted by an anti-STAT3 antibody directed against the COOH-terminal part of STAT3α (our unpublished observation). It is therefore possible that in ES cell extracts, these complexes contain STAT3β, a natural truncated form of STAT3 lacking the COOH-terminal part of STAT3α. In IL-6–treated cells, this particular form of STAT3 behaves as a constitutive transcription factor (48). It is therefore tempting to speculate that, in ES cells, a constitutive STAT3β-containing complex interacts with the APRE site, while a LIF-inducible STAT3α activity binds to the SIE site.

In conclusion, together with earlier findings (23, 37, 38), this report demonstrates that STAT3 is a LIF-dependent transcription factor that exerts opposite effects in ES cells and in the M1 myeloid cells. It is tempting to speculate that STAT3 is a common component of larger complexes that may mediate variable responses. The characterization of the partners of this common effector will ultimately help us to better understand the control mechanisms that are involved in each of these specific responses.

Together with the essential contribution of STAT3 in liver regeneration (10) and in antiapoptotis (18), the recent observation that STAT3 genetic disruption leads to embryonic lethality (55) stresses the essential function of STAT3 in early cell differentiation programs. The establishment of stable ES cell lines in which the expression of STAT3 dominant negative mutants is inducible should help us to further analyze the contribution of STAT3 to the maintenance of ES cell pluripotentiality.

Acknowledgments

We thank A. Dierich, M. Digelmann, and D. Queuche for ES cells and expert advice, and B. Chatton and M. Vigneron for helpful discussions and gifts of different materials. We are grateful to the following people for their generous gifts: T. Hirano and K. Nakajima for the pEF-BOS and pCAGGS-NEO STAT3 derivatives, P. Sassone-Corsi for the c-fos-CAT reporter construct, and B. Groner for the anti-STAT5 antibody. We also thank I. Lotz for the initial characterization of anti-STAT antibodies. We are grateful to the staffs of the cell culture, chemistry, and artwork facilities for providing help and materials.

This work was supported by funds from the Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique, the Institut National de la Santé et de la Recherche Médicale, the Centre Hospitalier Universitaire Régional, the Human Frontier Science Program, the Association pour la Recherche sur le Cancer, the Ligue Nationale contre le Cancer, and the Université Louis Pasteur de Strasbourg.

Abbreviations used in this paper

- CAT

chloramphenicol acetyl transferase

- ES

embryonic stem (cells)

- HA

hemagglutinin

- LIF

leukemia inhibitory factor

- MAP

mitogen-activated protein

- TK

thymidine kinase

Footnotes

References

- 1.Akira S, Nishio Y, Inoue M, Wang XJ, Wei S, Matsusaka T, Yoshida K, Sudo T, Naruto M, Kishimoto T. Molecular cloning of APRF, a novel IFN-stimulated gene factor 3 p91-related transcription factor involved in the gp130-mediated signaling pathway. Cell. 1994;77:63–71. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90235-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Akiyama T, Ishida J, Nakagawa S, Ogawara H, Watanabe S, Itoh N, Shibuya M, Fukami Y. Genistein, a specific inhibitor of tyrosine-specific protein kinases. J Biol Chem. 1987;262:5592–5595. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boschart M, Kluppel M, Schmidt A, Schutz G, Luckow B. Reporter constructs with low background activity utilizing the CATgene. Gene (Amst) 1992;110:129–130. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(92)90456-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boulter CA, Agguzi A, Williams RL, Wagner EF, Evans MJ, Beddington R. Expression of v-src induces aberrant development and twinning in chimaeric mice. Development (Camb) 1991;111:357–366. doi: 10.1242/dev.111.2.357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boulton TG, Zhong Z, Wen Z, Darnell JE, Jr, Stahl N. STAT3 activation by cytokines utilizing gp130 and related transducers involves a secondary modification requiring an H7-sensitive kinase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:6915–6919. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.15.6915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bradley A. Embryonic stem cells: proliferation and differentiation. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1990;2:1013–1017. doi: 10.1016/0955-0674(90)90150-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cao X, Tay A, Graeme RG, Tan YH. Activation and association of STAT3 with Src in V-src-transformed cell lines. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:1595–1603. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.4.1595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen C, Okayama H. High-efficiency transformation of mammalian cells by plasmid DNA. Mol Cell Biol. 1987;7:2745–2752. doi: 10.1128/mcb.7.8.2745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Conover, J.C., N.Y. Ip, W.T. Poueymirou, B. Bates, M.P. Goldfarb, T.M. De Chiara, and G.D. Yancopoulos. 1993. Ciliary neurotrophic factor maintains the pluripotentiality of embryonic stem cells. Development (Camb.). 1|:559–565. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Cressman DE, Greenbaum LE, De Angelis RA, Ciliberto G, Furth EE, Poli V, Taub R. Liver failure and defective hepatocyte regeneration in interleukin-6-deficient mice. Science (Wash DC) 1996;274:1379–1383. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5291.1379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Darnell JE, Jr, Kerr IM, Stark GR. Jak-STAT pathways and transcriptional activation in response to IFNs and other extracellular signaling proteins. Science (Wash DC) 1994;264:1415–1421. doi: 10.1126/science.8197455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Darnell JE., Jr Reflections on STAT3, STAT5, and STAT6 as fat STATs. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:6221–6224. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.13.6221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.David M, Petricoin E, Benjamin C, Pine R, Weber MJ, Larner AC. Requirement for MAP kinase (ERK2) activity in interferon alpha- and interferon beta-stimulated gene expression through STAT proteins. Science (Wash DC) 1995;269:1721–1723. doi: 10.1126/science.7569900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ernst M, Gearing DP, Dunn AR. Functional and biochemical association of Hck with the LIF/IL-6 receptor signal transducing subunit gp130 in embryonic stem cells. EMBO J. 1994;13:1574–1584. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06420.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ernst M, Oates A, Dunn AR. Gp130-mediated signal transduction in embryonic stem cells involves activation of Jak and Ras/mitogen-activated protein kinase pathways. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:30136–30143. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.47.30136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Escary JL, Perreau J, Dumenil D, Ezine S, Brulet P. Leukaemia inhibitory factor is necessary for maintenance of haematopoietic stem cells and thymocyte stimulation. Nature (Lond) 1993;363:361–364. doi: 10.1038/363361a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fu XY, Zhang JJ. Transcription factor p91 interacts with the epidermal growth factor receptor and mediates activation of the c-fos promoter. Cell. 1993;74:1135–1145. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90734-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fukada T, Hibi M, Yamanaka Y, Takahashi-Tezuka M, Fujitani Y, Yamaguchi T, Nakajima K, Hirano T. Two signals are necessary for cell proliferation induced by a cytokine receptor gp130: involvement of STAT3 in anti-apoptosis. Immunity. 1996;5:449–460. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80501-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gorman CM, Moffat LF, Howard BH. Recombinant genomes which express chloramphenicol acetyl transferase in mammalian cells. Mol Cell Biol. 1982;2:1044–1051. doi: 10.1128/mcb.2.9.1044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gouilleux F, Pallard C, Dusanter-Four I, Wakao H, Haldosen LA, Norstedt G, Levy D, Groner B. Prolactin, growth hormone, erythropoietin and granulocyte-macrophage colony stimulating factor induce MGF-STAT5 DNA binding activity. EMBO J. 1995;14:2005–2013. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb07192.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hilton DJ. LIF: a lot of interesting functions. Trends Biochem Sci. 1992;17:72–76. doi: 10.1016/0968-0004(92)90505-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hirano T, Matsuda T, Nakajima K. Signal transduction through gp130 that is shared among the receptors for the interleukin-6 related cytokine subfamily. Stem Cells. 1994;12:262–277. doi: 10.1002/stem.5530120303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hocke GM, Cui MZ, Fey GH. The LIF response element of the α2 macroglobulin gene confers LIF-induced transcriptional activation in embryonal stem cells. Cytokine. 1995;7:491–502. doi: 10.1006/cyto.1995.0067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Horvath CM, Wen Z, Darnell JE., Jr A STAT protein domain that determines DNA sequence recognition suggests a novel DNA-binding domain. Genes Dev. 1995;9:984–994. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.8.984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Horvath CM, Darnell JE., Jr The state of the STATs: recent developments in the study of signal transduction to the nucleus. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1997;9:233–239. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(97)80067-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ihle JN. Cytokine receptor signaling. Nature (Lond) 1995;377:591–594. doi: 10.1038/377591a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ihle JN. STATs and MAPKs: obligate or opportunistic partners in signaling. BioEssays. 1996;18:95–98. doi: 10.1002/bies.950180204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ihle JN, Witthuhn BA, Quelle FW, Yamamoto K, Thierfelder WE, Kreider B, Silvennoinen O. Signaling by the cytokine receptor superfamily: JAKs and STATs. Trends Biochem Sci. 1994;19:222–227. doi: 10.1016/0968-0004(94)90026-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ip NY, Nye SH, Boulton TG, Davis S, Taga T, Li Y, Birren SJ, Yasukawa K, Kishimoto T, Anderson DJ, et al. CNTF and LIF act on neuronal cells via shared signaling pathways that involve the IL-6 signal transducing receptor component gp130. Cell. 1992;69:1121–1132. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90634-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kaptein A, Paillard V, Saunders M. Dominant negative stat3 mutant inhibits interleukin-6-induced Jak-STAT signal transduction. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:5961–5964. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.11.5961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kishimoto T, Taga T, Akira S. Cytokine signal transduction. Cell. 1994;76:253–262. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90333-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kwon Kyu, T., M.A. Buchholz, F.J. Chrest, and A.A. Nordin. Staurosporine-induced G1 arrest is associated with the induction and accumulation of cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitors. Cell Growth Differ. 1996;7:1305–1313. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lamb P, Seidel HM, Haslam J, Milocco L, Kessler LV, Stein RB, Rosen J. STAT protein complexes activated by interferon-gamma and gp130 signaling molecules differ in their sequence preferences and transcriptional induction properties. Nucleic Acids Res. 1995;23:3283–3289. doi: 10.1093/nar/23.16.3283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lutticken C, Wegenka UM, Yuan J, Buschmann J, Schindler C, Ziemiecki A, Harpur AG, Wilks AF, Yasukawa K, Taga T, et al. Association of transcription factor APRF and protein kinase Jak1 with the interleukin-6 signal transducer gp130. Science (Wash DC) 1994;263:89–92. doi: 10.1126/science.8272872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Marshall CJ. Specificity of receptor tyrosine kinase signaling: transient versus sustained extracellular signal-regulated kinase activation. Cell. 1995;80:179–185. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90401-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Megeney LA, Perry RLS, Lecouter JE, Rudnicki MA. bFGF and LIF signaling activates STAT3 in proliferating myoblasts. Dev Genet. 1996;19:139–145. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1520-6408(1996)19:2<139::AID-DVG5>3.0.CO;2-A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Minami M, Inoue M, Wei S, Takeda K, Matsumoto M, Kishimoto T, Akira S. STAT3 activation is a critical step in gp130-mediated terminal differentiation and growth arrest of a myeloid cell line. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:3963–3966. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.9.3963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nakajima K, Yamanaka Y, Nakae K, Kojima H, Ichiba M, Kiuchi N, Kitaoka T, Fukada T, Hibi M, Hirano T. A central role for Stat3 in IL-6-induced regulation of growth and differentiation in M1 leukemia cells. EMBO J. 1996;15:3651–3658. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nishida E, Gotoh Y. The MAP kinase cascade is essential for diverse signal transduction pathways. Trends Biochem Sci. 1993;18:128–131. doi: 10.1016/0968-0004(93)90019-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pennica D, Wood WI, Chien KR. Cardiotrophin-1: a multifunctional cytokine that signals via LIF receptor-gp 130 dependent pathways. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 1996;7:81–91. doi: 10.1016/1359-6101(96)00007-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Piquet-Pellorce C, Grey L, Mereau A, Heath JK. Are LIF and related cytokines functionally equivalent? . Exp Cell Res. 1994;213:340–347. doi: 10.1006/excr.1994.1208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Robertson, E.J. 1987. Embryo-derived stem cell lines. In Teratocarcinomas and Embryonic Stem Cells: A Practical Approach. E.J. Robertson, editor. IRL Press, Oxford. 71 pp.

- 43.Rose TM, Weiford DM, Gunderson NL, Bruce AG. Oncostatin M (OSM) inhibits the differentiation of pluripotent embryonic stem cells in vitro. Cytokine. 1994;6:48–54. doi: 10.1016/1043-4666(94)90007-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sadowski HB, Gilman MZ. Cell-free activation of a DNA-binding protein by epidermal growth factor. Nature (Lond) 1993;362:79–83. doi: 10.1038/362079a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sadowski HB, Shuai K, Darnell JE, Jr, Gilman MZ. A common nuclear signal transduction pathway activated by growth factor and cytokine receptors. Science (Wash DC) 1993;261:1739–1744. doi: 10.1126/science.8397445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sassone-Corsi P, Sisson JC, Verma IM. Transcriptional autoregulation of the proto-oncogene fos. Nature (Lond) 1988;334:314–319. doi: 10.1038/334314a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Satoh T, Uehara Y, Kaziro Y. Inhibition of interleukin 3 and granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor stimulated increase of active Ras-GTP by Herbimycin A, a specific inhibitor of tyrosine kinases. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:2537–2541. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Schaefer TS, Sanders LK, Nathans D. Cooperative transcriptional activity of Jun and Stat3b, a short form of STAT3. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:9097–9101. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.20.9097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Schiemann WP, Graves LM, Baumann H, Morella KK, Gearing DP, Nielsen MD, Krebs EG, Nathanson NM. Phosphorylation of the human leukemia inhibitory factor (LIF) receptor by mitogen-activated protein kinase and the regulation of LIF receptor function by heterologous receptor activation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:5361–5365. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.12.5361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Schindler C, Darnell JE., Jr Transcriptional responses to polypeptide ligands: the JAK/STAT pathway. Annu Rev Biochem. 1995;64:621–651. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.64.070195.003201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Shuai K, Horvath CM, Huang LH, Qureshi SA, Cowburn D, Darnell JE., Jr Interferon activation of the transcription factor Stat91 involves dimerization through SH2-phosphotyrosyl peptide interactions. Cell. 1994;76:821–828. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90357-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Stahl N, Boulton TG, Farruggela T, Ip NY, Davis S, Witthuhn BA, Quelle FW, Silvennoinen O, Barbieri G, Pellegrini S, Ihle J, Yancopoulos GD. Association and activation of Jak-Tyk kinases by CNTF-LIF-OSM-IL6b receptor components. Science (Wash DC) 1994;263:92–95. doi: 10.1126/science.8272873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Stahl N, Farruggella TJ, Boulton TG, Zhong Z, Darnell JE, Jr, Yancopoulos GD. Choice of STATs and other substrates specified by modular tyrosine-based motifs in cytokine receptors. Science (Wash DC) 1995;267:1349–1353. doi: 10.1126/science.7871433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Stewart CL, Kaspar P, Brunet LJ, Bhatt H, Gadi I, Köntgen F, Abbondanzo SJ. Blastocyst implantation depends on maternal expression of leukaemia inhibitory factor. Nature (Lond) 1992;359:76–79. doi: 10.1038/359076a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Takeda K, Noguchi K, Shi W, Tanaka T, Matsumoto M, Yoshida N, Kishimoto T, Akira S. Targeted disruption of the mouse Stat3 gene leads to early embryonic lethality. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:3801–3804. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.8.3801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Taniguchi T. Cytokine signaling through nonreceptor protein tyrosine kinases. Science (Wash DC) 1995;268:251–255. doi: 10.1126/science.7716517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Treisman R. Regulation of transcription by MAP kinase cascades. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1996;8:205–215. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(96)80067-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wagner BJ, Hayes TE, Hoban CJ, Cochran BH. The SIF binding element confers sis-PDGF inducibility onto the c-fos promoter. EMBO J. 1990;9:4477–4484. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1990.tb07898.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Watanabe S, Arai K. Roles of the JAK-STAT system in signal transduction via cytokine receptors. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 1996;6:587–596. doi: 10.1016/s0959-437x(96)80088-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wen Z, Zhong Z, Darnell JE., Jr Maximal activation by STAT1 and STAT3 requires both tyrosine and serine phosphorylation. Cell. 1995;82:241–250. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90311-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Yin T, Yang YC. Mitogen-activated protein kinases and ribosomal S6 protein kinases are involved in signaling pathways shared by interleukin-11, interleukin-6, leukemia inhibitory factor, and oncostatin M in mouse 3T3-L1 cells. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:3731–3738. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Yu CL, Meyer DJ, Campbell GS, Larner AC, Carter-Su C, Schwartz J, Jove R. Enhanced DNA-binding activity of a STAT-3 related protein in cells transformed by the Src oncoprotein. Science (Wash DC) 1995;269:81–83. doi: 10.1126/science.7541555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Zajchowski DA, Boeuf H, Kedinger C. The adenovirus-2 early EIIa transcription unit possesses two overlapping promoters with different sequence requirements for EIa-dependent stimulation. EMBO J. 1985;5:1293–1300. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1985.tb03775.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Zhang XK, Blenis J, Li HC, Schindler C, Chenkiang S. Requirement of serine phosphorylation for formation of STAT-promoter complexes. Science (Wash DC) 1995;267:1990–1994. doi: 10.1126/science.7701321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Zhong Z, Wen Z, Darnell JE., Jr Stat3: a STAT family member activated by tyrosine phosphorylation in response to epidermal growth factor and interleukin-6. Science (Wash DC) 1994;264:95–98. doi: 10.1126/science.8140422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]