Abstract

Interactions between P-selectin, expressed on endothelial cells and activated platelets, and its leukocyte ligand, a homodimer termed P-selectin glycoprotein ligand-1 (PSGL-1), mediate the earliest adhesive events during an inflammatory response. To investigate whether dimerization of PSGL-1 is essential for functional interactions with P-selectin, a mutant form of PSGL-1 was generated in which the conserved membrane proximal cysteine was mutated to alanine (designated C320A). Western blotting under both denaturing and native conditions of the C320A PSGL-1 mutant isolated from stably transfected cells revealed expression of only a monomeric form of PSGL-1. In contrast to cells cotransfected with α1-3 fucosyltransferase-VII (FucT-VII) plus PSGL-1, K562 cells expressing FucT-VII plus C320A failed to bind COS cells transfected with P-selectin in a low shear adhesion assay, or to roll on CHO cells transfected with P-selectin under conditions of physiologic flow. In addition, C320A transfectants failed to bind chimeric P-selectin fusion proteins. Both PSGL-1 and C320A were uniformly distributed on the surface of transfected K562 cells. Thus, dimerization of PSGL-1 through the single, conserved, extracellular cysteine is essential for functional recognition of P-selectin.

Keywords: selectin, adhesion, endothelium, dimerization, inflammation

Selectins are a family of carbohydrate-binding adhesion molecules that mediate the initial interactions between blood cells and endothelium at inflammatory sites (8). P-selectin is stored in storage granules of both platelets and endothelial cells and is rapidly transported to the surface upon cellular activation, where it can interact with its leukocyte ligand, P-selectin glycoprotein ligand-1 (PSGL-1; references 17, 22).1 E-selectin is expressed by activated endothelial cells and interacts with ligands on myeloid cells and some circulating lymphocyte subsets. L-selectin is constitutively expressed by circulating leukocytes and interacts with both endothelial cell ligands and counterreceptors expressed by other leukocytes. Thus, interactions between selectins and their ligands mediate leukocyte–endothelial, leukocyte–platelet, and leukocyte–leukocyte interactions during an inflammatory response.

PSGL-1 is the best characterized selectin ligand to date. PSGL-1 is required for recognition of P-selectin by all classes of leukocytes (16, 19, 26). The NH2terminus of the molecule contains a consensus tyrosine sulfation motif, and sulfation of at least one tyrosine is essential for interactions with both P-selectin (21, 23, 31) and L-selectin (25). In addition to sulfation, PSGL-1 requires several other posttranslation modifications to recognize P-selectin, including addition of fucose in an α1-3 linkage by FucT-VII (10a, 14), and modification of O-glycans by core-2 β1,6 N-acetyglucosaminyltransferase (C2GnT; references 11, 13). PSGL-1 must also be modified with α2,3-linked sialic acids, but the identity of the sialyltransferase(s) that mediate these modifications in leukocytes is currently unknown.

PSGL-1 is expressed on leukocytes as a homodimer composed of two identical 120-kD subunits (17, 22), a feature unique among selectin glycoprotein ligands. PSGL-1 has three cysteine residues, each of which is found at identical corresponding positions in the murine homologue (32). Of these conserved cysteines, one is predicted to be located at the putative junction of the extracellular and transmembrane portions of the molecule, one is in the transmembrane region, and one is in the cytoplasmic tail. Which of these cysteines, if any, is responsible for dimerization, and whether dimerization of PSGL-1 is required for recognition of P-selectin, is unknown.

We have constructed and analyzed a PSGL-1 mutant in which the cysteine located at the junction of the extracellular and transmembrane regions was mutated to an alanine (designated C320A). The PSGL-1 C320A mutant was expressed exclusively as a monomer, and K562 cells stably transfected with both FucT-VII plus PSGL-1 C320A failed to bind P-selectin. Both PSGL-1 and C320A were uniformly distributed over the surface of transfected K562 cells. These studies show that dimerization of PSGL-1 via cys320 is essential for physiologic interactions with P-selectin.

Materials and Methods

Generation of a PSGL-1 Dimerization Mutant

Introduction of a point mutation at position 969 of the hPSGL-1 cDNA (16) was carried out by PCR-based site-directed mutagenesis. Amplification used an antisense oligonucleotide 5′ GAT GGC CAG CAG GGC CTG CTT CAC AGA 3′ and a sense oligonucleotide 5′ TCT GTG AAG CAG GCC CTG CTG GCC ATC 3′. This mutation, designated C320A, substitutes an alanine for a cysteine at amino acid position 320. The PCR product was gel purified, ligated into full-length PSGL-1, subcloned into a modified SRα vector containing a neoR cassette, and then sequenced by the dideoxy chain termination method (Perkin Elmer AmpliCycle, Branchburg, NJ), confirming the fidelity of the mutagenesis.

Production of Stable Transfectants

cDNA for C320A, PSGL-1, and FucT-VII were subcloned into a modified SRα vector containing either a neoR or hygroR cassette, and used to transfect human K562 cells by electroporation. Transfectants were selected in medium containing either 0.5 mg/ml Hygromycin B (Calbiochem Novabiochem, La Jolla, CA) or 1.0 mg/ml G418 (geneticin; GIBCO BRL, Gaithersburg, MD). Transfected cells expressing PSGL-1 or C320A were identified by flow cytometry with KPL1 (25), which identifies a sulfate-dependent epitope within the tyrosine sulfate motif of human PSGL-1. Cells expressing FucT-VII were identified by positive staining for HECA-452 (20); which recognizes FucT-VII–dependent epitopes (10, 29). Expression of FucT-VII was confirmed by reverse transcription (RT)-PCR. Positive transfectants were cloned by limiting dilution, and clones were tested as described for the parent population. Only clones that were 100% positive as compared with the untransfected parent cells were used. Cloned K562 transfectants were maintained in RPMI-1640 containing 10% FCS, 1% penicillin/streptomycin, and 2 mM l-glutamine. It should be noted that, unlike the K562 cells examined by Bierhuizen and Fukuda (2), the K562 cells used in these studies endogenously express significant amounts of core-2 β1,6 N-acetyglucosaminyltransferase (C2GnT; reference 2), which is also required for binding of PSGL-1 to P-selectin (11, 13; see below).

Biochemical Analysis of the C320A Mutant

K562/FucT-VII/PSGL-1 or K562/FucT-VII/C320A cells were washed twice in RPMI. Cells were surface biotinylated by incubation of cells at 107/ml in PBS containing freshly prepared NHS-biotin at a final concentration of 0.55 mg/ml for 30 min at room temperature. Cells (labeled or unlabeled) were then washed three times in PBS, and resuspended at 1.5 × 107 cells/ml in lysis buffer (1% Triton X-100, 150 mM NaCl, 10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.6, 1 mM CaCl2, 1 mM MgCl2, 1 mM aprotinin, 1 mM PMSF, 1 mM leupeptin, and 1 mM pepstatin A) and incubated on ice for 30 min. Samples were clarified by centrifugation at 14,000 g for 30 min at 4°C, and supernatants were transferred to fresh tubes. Immunoprecipitations were performed where indicated using KPL1 coupled to Affigel-10 at 2 mg/ml and lysates of cells surface labeled with biotin, as described above. Immunoprecipitates or whole cell lysates were boiled for 5 min in SDS-PAGE sample buffer, electrophoresed on 5 or 6% polyacrylamide gels under nonreducing conditions, and transferred to nitrocellulose for Western blotting.

For native, nondenaturing gels, “native blue” gels were performed exactly as described (24). Lysates were prepared as described above, adjusted to 5% glycerol and 2.5 mg/ml Brilliant blue G (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, MO), electrophoresed on a 5% polyacrylamide gel under nonreducing conditions, and then transferred to nitrocellulose for Western blotting.

Cross-linking studies were performed using graded amounts of BS3 (Pierce Chemicals Co., Rockford, IL) as indicated in the Fig. 1 legend. Cells were incubated on ice with from 3–100 μM BS3, freshly dissolved in PBS for 1.5 h, quenched once in PBS and 20 mM glycine, washed three times in PBS, lysed in lysis buffer, run under reducing conditions on a 6% gel, and then transferred to nitrocellulose.

Figure 1.

Dimerization of PSGL-1 is mediated by cysteine 320. (A) SDS-PAGE analysis of KPL1 immunoprecipitates made from cell surface biotinylated K562 cells stably transfected with either wild-type PSGL-1 (lane 1) or C320A (lane 2). KPL1 immunoprecipitates were electrophoresed under nonreducing conditions, transferred to nitrocellulose and probed with avidin-HRPO. (B) Native gel electrophoresis of wild-type PSGL-1 (lane 1) or C320A (lane 2). Cell lysates were analyzed by native PAGE on 5% polyacrylamide gels, transferred to nitrocellulose and probed with KPL1. Under both denaturing and native conditions, K562 cells transfected with PSGL-1 express primarily the 240-kD form of the molecule, whereas cells transfected with C320A express only the monomeric form of PSGL-1. (C) Cross-linking analysis of PSGL-1 and C320A dimerization. Cells were incubated with 3-100 μM BS3 cross-linker and analyzed under reducing conditions by SDS-PAGE followed by Western blotting with KPL1.

For Western blotting, the nitrocellulose was blocked with 2% gelatin (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA) in TBS-Tween (TBS-T; 20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.6, 137 mM NaCl, 0.1% Tween-20) for 2 h at room temperature. Blots were probed either with KPL1 in TBS-T plus 2% gelatin for 30 min, washed five times in TBS-T and then incubated with goat anti– mouse IgG conjugated to horseradish peroxidase (BioSource International, Camarillo, CA) for 30 min (for whole cell lysates), or with avidin-HRPO (for KPL1 immunoprecipitates). After five washes in TBS-T, blots were visualized by chemiluminescence generated after the addition of enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL; Amersham Pharmacia Biotechnology Inc., Piscataway, NJ) and exposed to Hyperfilm (Amersham Pharmacia Biotechnology Inc.).

Flow Cytometry

Expression of PSGL-1 or C320A was evaluated by immunofluorescence staining with FITC-conjugated KPL1. Expression of FucT-VII was evaluated by staining with HECA-452, which recognizes reporter epitopes associated with FucT-VII enzyme activity (10, 29). HL60, K562, and transfected K562 cells were harvested, washed, and then 0.5 × 106 of each cell type was incubated in 100 μl of PBS, 1% FCS, and 0.1% NaN3 containing pretitered amounts of the primary antibody. Cells incubated with HECA-452 were washed and incubated with goat anti–mouse IgM-FITC (Biosource International). In some experiments, transfected K562 cells were incubated with fusion proteins consisting of recombinant mouse P-selectin fused to human IgM (14), washed, and incubated with goat anti–human IgM conjugated to phycoerythrin (PE; Sigma Chemical Co.). Samples were analyzed on a Becton Dickinson FACScan® and data were collected on a total of 10,000 light scatter gated events. Data was analyzed with CELLQuest software and fluorescence histograms are displayed on a four decade logarithmic scale.

RT-PCR and Southern Blot Analysis

Total cellular RNA was isolated from 107 cells, using TRIzol (GIBCO BRL) according to the manufacture's instructions. RT of 1 μg of DNase-treated total cellular RNA was carried as previously described (26, 29). PCR reactions containing 5 μl of the appropriate RT reaction in a final reaction volume of 100 μl containing 1.5 mM MgCl2, 0.2 mM each dNTP, 0.5 μM specific sense and antisense primers, and 2.5 U Taq polymerase (Perkin-Elmer Corp., Norwalk, CT) were carried out with cycle parameters described below. Sense and antisense primers for FucT-VII and pgk1 have been described elsewhere (26, 29). For FucT-VII mRNA detection, the PCR protocol was: 1 min at 94°C, 1 min at 65°C, 1 min at 72°C, for 35 cycles. For pgk1 detection, the PCR protocol was: 1 min at 94°C, 1 min at 65°C, 1 min at 72°C, for 25 cycles. For detection of C2GnT mRNA, the PCR protocol was: 1 min at 94°C, 1 min at 65°C, 1 min at 72°C, for 30 cycles, using the sense primer 5′ TTT TCW GGC AGT GCC TAC TTC GTG GTC 3′ in which W indicates an equal ratio of A and T, and the antisense primer 5′ ATG CTC ATC CAA ACA CTG GAT GGC AAA 3′. FucT-VII primers amplified a product of 500 bp, pgk1 a product 374 bp long, and C2GnT a 372-bp product. Presence of PCR products was assayed by gel electrophoresis in 1.4% agarose, DNA was transferred onto nitrocellulose in 10× SSC, and Southern blotting of the RT-PCR products was carried out as previously described (26, 29).

Low Shear COS Cell Adhesion Assay

Binding of leukocytes to COS cells transiently transfected with cDNA encoding P-selectin was as described (9, 26, 29). In brief, COS cells were transfected by the DEAE-dextran method in 100-mm tissue culture grade petri dishes, replated on 35-mm dishes (assay plates), and allowed to readhere overnight. The next day, HL60 cells or transfectants were washed twice in RPMI-1640 and resuspended at 3.3 × 106 cells/ml and placed on ice. Each petri dish was washed three times with unsupplemented RPMI-1640, followed by the addition of 2 × 106 cells in a total volume of 0.6 ml. Cell were incubated on a constantly rocking platform for 15 min at 4°C, and the plates were washed five times with RPMI-1640 followed by fixation with cold 0.37% formaldehyde and RPMI-1640. Mean number of cells bound per COS cell was determined by counting the number of cells bound/COS cell on ∼100 COS cells in multiple 40× fields using a standard inverted light microscope.

Parallel Plate Flow Assay

The parallel plate flow chamber and flow assay protocol were as described (10). Rolling of cell lines and transfectants at 1.0 dynes/cm2 on monolayers of stably transfected CHO expressing P-selectin was analyzed. Levels of P-selectin on stably transfected CHO cells were similar to those of E-selectin expressed by TNF-α stimulated human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVEC). Data was analyzed with Celltrak software developed with Compix, Inc. (Mars, PA) for use on their C-Imaging 1280 Computerized Morphometry System. Celltrak tracks leukocytes in real time as they flow over transfected CHO cells. Sequential images of the tracked cells were digitized and matched on the basis of their trajectories and morphology. Velocities were calculated using the time delay between captured images and statistics were compiled for the prescribed number of fields. Interactive “events”, which correspond to rolling cells, were collected from 60– 100 sequential fields during 2–6 min of observation.

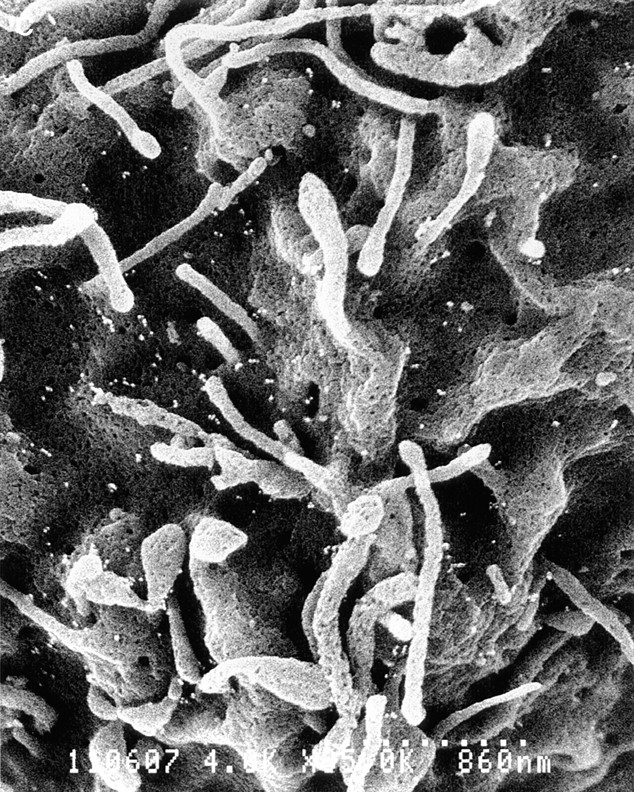

Scanning Immunoelectron Microscopy

106 K562/FucT-VII/PSGL-1 or K562/FucT-VII/C320A cells were resuspended in 100 μl PBS plus 5% goat serum containing KPL1, incubated on ice for 15 min and rinsed twice with PBS. Cells were resuspended in 100 μl PBS plus 5% goat serum containing goat anti–mouse IgG conjugated to 12 nm gold (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratory, West Grove, PA), incubated on ice for 15 min, rinsed twice in PBS plus 0.2% bovine serum albumin (BSA Fraction V; Sigma Chemical Co.), and resuspended in 100 μl PBS plus 0.2% BSA. Approximately 50 μl of the cell suspension was applied to degreased glass chips precoated with 0.1% poly-l-lysine (Sigma Chemical Co.), the cells were allowed to settle on the chips for 10 min at room temperature, and the entire chip was transferred to a petri dish containing 3% EM grade glutaraldehyde (Electron Microscopy Services, Fort Washington, PA) in 0.1 M sodium cacodylate (Sigma Chemical Co.) buffer containing 7.5% sucrose for overnight fixation. Samples were assigned a code number and prepared for analysis of either PSGL-1 or C320A distribution using a Hitachi S-900 LVSEM equipped with a stereoviewer for enhanced spatial resolution, as described (5, 7).

Results

Dimerization of PSGL-1 Is Mediated by Cysteine 320

Cell lysates prepared from K562 cells stably transfected with either wild-type PSGL-1 or C320A were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and Western blot analysis (Fig. 1 A). Under these denaturing conditions, only a single band of ∼120 kD was detected in cells transfected with C320A, whereas K562 cells transfected with wild-type PSGL-1 expressed the dimeric form of the molecule. Therefore, cysteine 320 is solely responsible for covalent dimerization. To determine whether significant noncovalent dimerization of the C320A occurred, the mutant and wild-type PSGL-1 were analyzed by native PAGE (Fig. 1 B). Under these nondenaturing conditions, the C320A mutant retained the mobility of a monomeric form of PSGL-1. To examine this issue further, cross-linking studies were performed (Fig. 1 C). Significant cross-linking of wild-type PSGL-1 was observed at BS3 concentrations as low as 10 μM, whereas cross-linking of the C320A mutant was not detectable until cross-linker concentrations of 100 μM were used. Taken together, these observations establish that the conserved cysteine residue located just external to the transmembrane region of PSGL-1 is responsible for dimerization of the surface expressed molecule.

Expression of PSGL-1, C320A, FucT-VII, and C2GnT by Stably Transfected K562 Cells

We have previously shown that cotransfection of K562 cells with PSGL-1 and FucT-VII is necessary and sufficient for adhesion to P-selectin, whereas transfection with FucT-VII alone is sufficient for adhesion to E-selectin (26). To determine whether C320A was capable of recognizing P-selectin, K562 cells were stably transfected with both FucT-VII and either wild-type PSGL-1 or C320A. One-color flow cytometry was used to select clones that expressed equivalent surface levels of either PSGL-1 or C320A as measured by staining with the anti–PSGL-1 monoclonal antibody KPL1 (25), and comparable levels of epitopes defined by HECA-452, an anti-carbohydrate antibody that recognizes fucosylated structures associated with FucT-VII activity (10, 29; Fig. 2). The flow cytometric profiles of HL60 cells are included as a positive control, as HL60 cells express both PSGL-1 and FucT-VII and bind well to P-selectin.

Figure 2.

Expression of PSGL-1, C320A, and FucT-VII–dependent epitopes on stably transfected K562 cells. Expression of either wild-type PSGL-1 or C320A was determined by staining with KPL1, and FucT-VII enzyme activity was determined by HECA-452 staining. Note that equal or higher levels of C320A and FucT-VII are found on K562/FucT-VII/C320A transfectants compared with K562/FucT-VII/PSGL-1 cells. HL60 cells are included as controls.

These PSGL-1 or C320A double transfectants were also screened by Southern blotting of RT-PCR products to ensure that the selected clones had equivalent levels of mRNA for both C2GnT and FucT-VII (Fig. 3). Expression of FucT-VII mRNA correlates with surface expression of HECA-452 (10, 29; Fig 2), and slightly higher levels were seen in K562/FucT-VII/C320A cells compared with K562/FucT-VII/PSGL-1 cells. These K562 cells endogenously express C2GnT, and the K562/FucT-VII/C320A and K562/FucT-VII/PSGL-1 cells expressed equivalent levels of C2GnT mRNA (Fig. 3). Therefore, the K562/ FucT-VII/C320A cells expressed equal or higher levels of PSGL-1 or C320A, FucT-VII, and C2GnT as did K562/ FucT-VII/PSGL-1 cells.

Figure 3.

RT-PCR analysis of FucT-VII and C2GnT mRNA expression in K562 transfectants. RNA was isolated, and RT-PCR was performed as described in Materials & Methods. “+” and “−” refer to the presence or absence, respectively, of RT in the RT reaction. Pgk1 is a housekeeping enzyme included as an internal control. Indistinguishable levels of C2GnT mRNA are seen in K562/FucT-VII/PSGL-1 and K562/FucT-VII/C320A cells, whereas slightly higher levels of FucT-VII mRNA are seen in K562/FucT-VII/C320A cells, consistent with higher staining by HECA-452 (Fig. 2).

Binding of Soluble P-Selectin Chimeras to K562 Cells Transfected with Either PSGL-1 or C320A

To determine if dimerization mediated by cysteine 320 affects the avidity of PSGL-1 for P-selectin, K562 transfectants were incubated with soluble recombinant P-selectin and analyzed by flow cytometry. P-selectin chimeric proteins bound well to K562/FucT-VII/PSGL-1 cells, but bound at very low levels to K562/FucT-VII/C320A cells (Fig. 4). P-selectin chimeras did not bind to parent K562 cells or to K562 cells transfected with FucT-VII only (data not shown). These results indicate that the avidity of PSGL-1 for P-selectin was sharply reduced or eliminated by the C320A mutation.

Figure 4.

Binding of soluble P-selectin to K562 transfectants. Binding of soluble recombinant P-selectin fusion proteins was assessed by flow cytometry. Data are given as the mean channel fluorescence of ∼10,000 light scatter gated events. K562/FucT-VII/ C320A cells bound P-selectin poorly in comparison to K562/ FucT-VII/PSGL-1.

Adhesion of K562/FucT-VII/PSGL-1 or K562/FucT-VII/C320A to P-Selectin Under Low Shear Conditions

To determine if K562/FucT-VII/C320A cells could interact with cell surface expressed P-selectin, COS cells were transfected with cDNA encoding P-selectin, and K562 transfectants were assayed for their ability to interact with these transfected COS cells. K562 cells expressing both FucT-VII and wild-type PSGL-1 bound well to COS cells transiently transfected with P-selectin (Fig. 5). In contrast, K562/FucT-VII/C320A did not bind appreciably to COS cells expressing P-selectin (Fig. 5). The inability of the C320A mutant to recognize P-selectin under these relatively nonstringent conditions indicates that this mutant is extremely impaired in adhesion to P-selectin.

Figure 5.

Binding of K562/FucT-VII/PSGL-1 and K562/FucT-VII/C320A to COS cells transfected with P-selectin. Binding of cells to COS cells expressing high levels of P-selectin was assessed under low shear conditions as described in Materials and Methods. Untransfected K562 cells, which express neither PSGL-1 nor FucT-VII, and HL60 cells are included as negative and positive controls, respectively.

Adhesion of Stably Transfected K562 Cells to P-Selectin Under Physiologic Levels of Defined Shear Stress

The results from the low shear COS cell adhesion assay were extended to an analysis of rolling under a constant shear stress of 1.0 dynes/cm2. Transfectants were incubated on CHO monolayers expressing P-selectin (CHO/ P), and the number of interactions and rolling velocities were determined for the different cell types. U937 cells, like HL60 cells, express PSGL-1, C2GnT, and FucT-VII, and bind strongly to P-selectin, with high numbers of interactions (2,890 events; Fig 6) and low rolling velocities (10.8 μm/s). Similarly, K562/FucT-VII/PSGL-1 cells exhibited high levels of interactions (2265 ± 17 events) and low rolling velocities (10.4 ± 0.1 μm/s) with CHO/P cells. In contrast, K562/FucT-VII/C320A cells exhibited sharply reduced interactions (143 ± 5 events, ∼6% of control). Importantly, this level of interactions was virtually identical to that seen with K562 cells transfected with FucT-VII cDNA only (∼40 ± 7 events; data not shown), and inspection of the tapes revealed that these interactions consisted only of brief attachment and release, with no sustained rolling. The ability of PSGL-1 to mediate rolling on P-selectin under these conditions was therefore essentially abolished by the C320A mutation.

Figure 6.

Rolling of K562/FucT-VII/PSGL-1 or K562/FucT-VII/ C320A cells on P-selectin under defined shear stress. The number of adhesive interactions of cells rolling on CHO cells expressing P-selectin were quantitated at a shear stress of 1.0 dynes/cm2. U937 cells are included for comparison and as a positive control. The number of events for the C320A cells was virtually identical to that of cells transfected with FucT-VII cDNA alone (data not shown).

Cell Surface Localization of PSGL-1 and C320A

PSGL-1 is localized to the microvilli of normal neutrophils (3, 16). To determine if the C320A mutation affected this pattern of localization, K562/FucT-VII/PSGL-1 and K562/ FucT-VII/C320A cells were examined by immunogold scanning electron microscopy. K562 cells displayed considerable heterogeneity of surface architecture, with numerous prominent microvilli of variable length (Fig. 7 A). In addition, unlike normal leukocytes, PSGL-1 expressed on K562 cells exhibited a uniform surface distribution, with significant expression on both microvilli and the cell body (Fig. 7 B). K562 cells transfected with C320A also demonstrated this uniform distribution on both microvilli and the cell body (Fig. 7 C). Thus, in stably transfected K562 cells, no specific localization of PSGL-1 to microvilli was observed, and this pattern was unaltered with the C320A mutant.

Figure 7.

Cell surface distribution of PSGL-1 and C320A on transfected K562 cells. (A) Low power photomicrograph (3,000×) of K562/FucT-VII/PSGL-1 cells. Note the prominent and varied microvilli and ruffles on these cells. (B) High power (8,000×) of K562/FucT-VII/PSGL-1 cells. (C) High power (8,000×) of K562/FucT-VII/C320A cells. Both cell types exhibited a uniform distribution of PSGL-1 on both microvilli and the cell body.

Discussion

Several groups have characterized structural features of PSGL-1 required for recognition of P-selectin. A number of posttranslational modifications are important, including tyrosine O-sulfation, sialylation, fucosylation, and branching of O-linked carbohydrates, and some of the specific enzymes that mediate these modifications of PSGL-1 on leukocytes have been identified (see Introduction). In addition to these requirements, we show here that dimerization of PSGL-1 is required for effective recognition of P-selectin.

Under both denaturing (SDS) and native conditions, the C320A mutation resulted in expression of only a 120-kD, monomeric form of PSGL-1. Furthermore, cross-linking studies showed that the C320A mutant required concentrations >10-fold higher to achieve significant cross-linking, compared with native PSGL-1. These data demonstrate clearly that the single extracellular cysteine located at position 320 mediates dimerization of PSGL-1, at least in this cell type. These results collectively make it quite unlikely that low affinity, noncovalent association of monomeric PSGL-1 molecules occur. If so, these associations are undetectable under the conditions employed, and are insufficient for cell adhesion to P-selectin.

Three independent assays demonstrated a crucial role for dimerization of PSGL-1 in binding to P-selectin. Stably transfected K562 cells expressing C320A, a PSGL-1 mutant in which the single extracellular cysteine was changed to alanine, bound soluble recombinant P-selectin chimeric proteins at extremely low levels, indistinguishable from untransfected K562 cells. Transfected COS cells used in the low-shear adhesion assay express levels of P- and E-selectin considerably higher than those found in normal endothelium, making this a sensitive assay for detecting leukocyte interactions with P- or E-selectin. Even in this low stringency assay, K562/FucT-VII/C320A transfectants failed to bind to P-selectin. These results were confirmed in a higher stringency parallel plate flow assay performed under physiologic levels of defined shear flow. K562/FucT-VII/C320A cells exhibited only very few and quite transient interactions, whereas K562/FucT-VII/PSGL-1 cells exhibited high numbers of interactions and typical low rolling velocities on P-selectin. In contrast to these results, both transfectants interacted well with E-selectin (data not shown), consistent with recognition of E-selectin by K562 cells as a function of FucT-VII expression independent of PSGL-1 (26). Taken together, our findings demonstrate that dimerization of PSGL-1 through cys320 is required for effective recognition of P-selectin.

Our findings are apparently at odds with work by Pouyani et al. (21), who reported that dimerization of PSGL-1 was not required for P-selectin binding. In that study, the transmembrane and cytoplasmic regions of PSGL-1 were replaced by the corresponding regions of CD43, which have no cysteines and hence cannot covalently dimerize. No compromise in binding was observed in an adhesion assay that measured the binding of transfected COS cells overexpressing PSGL-1 mutants to immobilized P-selectin immunoglobulin fusion proteins. In contrast, our studies analyzed the binding of cells expressing approximately normal levels of either wild-type PSGL-1 or C320A to P-selectin expressing monolayers in a relatively physiologic setting. The findings by Pouyani et al. (21) were likely due to high overexpression of ectopically expressed proteins in transfected COS cells, as we have been able to detect some binding of lymphoid P-selectin transfectants to COS cells overexpressing C320A (data not shown). These observations emphasize the importance of studying selectin/ligand interactions using cells expressing normal levels of relevant gene products in physiologically relevant settings.

PSGL-1 localizes to the tips of microvilli on all leukocyte subsets examined (3, 16). It has been proposed that this pattern of localization to microvilli is essential for functional interactions with P-selectin, and is an important property of “rolling receptors” generally (4, 28). However, PSGL-1 displayed a random pattern of distribution on K562 cells, being found on both the planar cell body and on microvilli, a pattern that was not altered by the C320A mutation. Since PSGL-1 expressed by K562 cells clearly mediates functional interactions with P-selectin, these results imply that either localization to microvilli is not essential, or a sufficient amount of PSGL-1 is expressed on the microvilli for significant attachment and rolling. In contrast to PSGL-1, ectopically expressed integrin α4 chains are localized to microvilli in transfected K562 cells (1). Therefore, our data suggest that at least some elements of the cellular sorting mechanism(s) responsible for localization of PSGL-1 to microvilli are absent from K562 cells, and further that at least some of this cellular machinery is distinct from that which sorts other molecules, e.g. VLA-4, to microvilli. Thus, at least in K562 cells, elements required for localization to microvilli are most likely independent of those required for functional interactions with P-selectin.

The three-dimensional structure of PSGL-1 binding to P-selectin has not been determined. It is therefore not known if dimerization of PSGL-1 merely provides two identical binding sites, one on each chain of a single homodimer. Cooperative binding of P-selectin to dual binding sites might be required for effective recognition and cell adhesion. Consistent with this, soluble dimeric P-selectin binds with considerably higher avidity to HL60 cells than monomeric P-selectin (27). A more interesting possibility, which we favor, is that dimerization could position the two chains of PSGL-1 so as to allow a tyrosine sulfate attached to one chain to be properly oriented with an O-glycan on the other chain, thereby creating a binding site in trans. Thus, dimeric PSGL-1 would express two binding sites, whereas monomeric PSGL-1 would express none. This model is consistent with the essentially complete absence of binding to P-selectin of the C320A mutant. Alternatively, or in addition, dimerization of PSGL-1 might be essential for proper recognition and interaction with cytoplasmic proteins. Interactions of a dimeric cytoplasmic tail with cytoplasmic elements, particularly cytoskeletal proteins, may be responsible for proper orientation of the extracellular portion of PSGL-1, and may also stabilize interactions with P-selectin. An important function for the cytoplasmic tail of PSGL-1 is suggested by the comparatively high degree of conservation of this region compared with the extracellular portion. These various possibilities are under active investigation.

Dimerization or higher order multimerization may be a physiologically relevant feature of cell adhesion molecules generally. Intercellular adhesion molecule 1 (ICAM-1) exists as a dimer on the surface of several cell types, and binds Limas flavus agglutinin 1 (LFA-1) at higher levels than monomeric ICAM-1 (15). Similarly, recent work has suggested that clustering or multimerization of L-selectin, which also binds PSGL-1 (6, 30) through the NH2-terminal tyrosine sulfate motif (25), significantly enhances binding to soluble GlyCAM-1 (18), a component of L-selectin ligands expressed by HEV (12). These observations, in concert with the present report, suggest that multimerization may be important for the activity of cell adhesion molecules via several distinct mechanisms.

In summary, using cells stably transfected with physiologic levels of either PSGL-1 or C320A, and using both low and high shear adhesion assays, we have shown that dimerization of PSGL-1 is essential for effective cell adhesion to P-selectin. Future work will focus on the molecular basis for this unique feature of PSGL-1.

Acknowledgments

Supported by grant CB-204 from the American Cancer Society (G.S. Kansas) and AI33189 and HL31963 from the National Institutes of Health (L.M. Stoolman). G.S. Kansas is an Established Investigator of the American Heart Association.

Abbreviations used in this paper

- ECL

enhanced chemiluminescence

- HUVEC

human umbilical vein endothelial cells

- ICAM-1

intercellular adhesion molecule 1

- LFA-1

Limas flavus agglutinin 1

- PSGL-1

P-selectin glycoprotein ligand-1

- RT

reverse transcription

- TBS-T

TBS-Tween

Footnotes

Address all correspondence to Geoffrey S. Kansas, Department of Microbiology/Immunology, Northwestern University Medical School; 303 E. Chicago Ave., Chicago, IL 60611. Tel.: (312) 908-3237. Fax: (312) 503-1339. E-mail: gsk@nwu.edu

References

- 1.Abitorabi MA, Pachynski RK, Ferrando RE, Tidswell M, Erle DJ. Presentation of integrins on leukocyte microvilli: a role for the extracellular domain in determining membrane localization. J Cell Biol. 1997;139:563–571. doi: 10.1083/jcb.139.2.563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bierhuizen MF, Fukuda M. Expression cloning of a cDNA encoding UDP-GlcNAc:Gal beta 1-3-GalNAc-R (GlcNAc to GalNAc) beta 1-6GlcNAc transferase by gene transfer into CHO cells expressing polyoma large tumor antigen. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:9326–330. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.19.9326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Breuhl RE, Moore KL, Lorant DE, Borregard N, Zimmerman GA, McEver RP, Bainton DF. Leukocyte activation induces surface redistribution of P-selectin glycoprotein ligand-1. J Leuk Biol. 1997;61:489–499. doi: 10.1002/jlb.61.4.489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Butcher EC, Picker LJ. Lymphocyte homing and homeostasis. Science. 1996;272:60–66. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5258.60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Erlandsen SL, Hasslen SR, Nelson RD. Detection and spatial distribution of the β2 integrin (Mac-1) and L-selectin (LECAM-1) adherence receptors on human neutrophils by high resolution field emission SEM. J Histochem Cytochem. 1993;41:327–333. doi: 10.1177/41.3.7679125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Guyer GA, Moore KL, Lynam EB, Schammel CMG, Rogelj S, McEver RP, Sklar LA. P-selectin glycoprotein ligand-1 (PSGL-1) is a ligand for L-selectin in neutrophil aggregation. Blood. 1996;88:2415–2421. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hasslen SR, von Andrian UH, Butcher EC, Nelson RD, Erlandsen SL. Spatial distribution of L-selectin (CD62L) on human lymphocytes and transfected murine L1-2 cells. Histochem J. 1995;27:547–554. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kansas GS. Selectins and their ligands: current concepts and controversies. Blood. 1996;88:3259–3286. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kansas GS, Saunders KB, Ley K, Zakrzewicz A, Gibson RM, Furie BC, Furie B, Tedder TF. A role for the epidermal growth factor-like domain of P-selectin in ligand recognition and cell adhesion. J Cell Biol. 1994;124:609–618. doi: 10.1083/jcb.124.4.609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Knibbs RN, Craig RA, Natsuka S, Chang A, Cameron M, Lowe JB, Stoolman LM. The fucosyltransferase FucT-VII regulates E-selectin ligand synthesis in human T cells. J Cell Biol. 1996;133:911–920. doi: 10.1083/jcb.133.4.911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10a.Knibbs, R.N., R.A. Craig, Petr Mály, P.L. Smith, F.M. Wolber, N.E. Faulkner, J.B. Lowe, and L.M. Stoolman. 1998. α(1,3)Fucosyltransferase-VII dependent synthesis of P- and E-selectin ligands on cultured T-lymphoblasts. J. Immunol. In press. [PubMed]

- 11.Kumar R, Camphausen RT, Sullivan FX, Cumming DA. Core 2 β-1,6-N-acetylglucosaminyltransferase enzyme activity is critical for P-selectin glycoprotein ligand-1 binding to P-selectin. Blood. 1996;88:3872–3879. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lasky LA, Singer MS, Dowbenko D, Imai Y, Henzel WJ, Grimley C, Fennie C, Gillett N, Watson SR, Rosen SD. An endothelial ligand for L-selectin is a novel mucin-like molecule. Cell. 1992;69:927–938. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90612-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Li F, Wilkins PP, Crawley S, Weinstein J, Cummings RD, McEver RP. Post-translational modifications of recombinant P-selectin glycoprotein ligand-1 required for binding to P- and E-selectin. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:3255–3264. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Maly P, Thall AD, Petryniak B, Rogers CE, Smith PL, Marks RM, Kelly RJ, Gersten KM, Cheng G, Saunders TL, et al. The α(1,3) fucosyltransferase FucT-VII controls leukocyte trafficking through an essential role in L-, E-, and P-selectin ligand biosynthesis. Cell. 1996;86:643–653. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80137-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Miller J, Knorr R, Ferrone M, Houdei R, Carron CR, Dustin ML. Intercellular adhesion molecule-1 dimerization and its consequences for adhesion mediated by lymphocyte function associated-1. J Exp Med. 1995;182:1231–1241. doi: 10.1084/jem.182.5.1231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Moore KL, Patel KD, Breuhl RE, Fugang L, Johnson DL, Lichenstein HS, Cummings RD, Bainton DF, McEver RP. P-selectin glycoprotein ligand-1 mediates rolling of human neutrophils on P-selectin. J Cell Biol. 1995;128:661–671. doi: 10.1083/jcb.128.4.661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Moore KL, Stults NL, Diaz S, Smith DF, Cummings RD, Varki A, McEver RP. Identification of a specific glycoprotein ligand for P-selectin (CD62) on myeloid cells. J Cell Biol. 1992;118:445–456. doi: 10.1083/jcb.118.2.445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nicholson MW, Barclay AN, Singer MS, Rosen SD, van der Merwe PA. Affinity and kinetic analysis of L-selectin (CD62L) binding to glycosylation-dependent cell adhesion molecule-1. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:763–770. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.2.763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Norman KE, Moore KL, McEver RP, Ley K. Leukocyte rolling in vivo is mediated by P-selectin glycoprotein ligand-1. Blood. 1995;86:4417–4423. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Picker LJ, Michie SA, Rott LS, Butcher EC. A unique phenotype of skin-associated lymphocytes in humans. Am J Path. 1990;136:1053–1060. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pouyani T, Seed B. PSGL-1 recognition of P-selectin is controlled by a tyrosine sulfation consensus at the PSGL-1 amino terminus. Cell. 1995;83:333–343. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90174-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sako D, Chang X-J, Barone KM, Vachino G, White HM, Shaw G, Veldman GM, Bean KB, Ahern TJ, Furie B, et al. Expression cloning of a functional glycoprotein ligand for P-selectin. Cell. 1993;75:1179–1186. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90327-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sako D, Comess KM, Barone KM, Camphausen RT, Cumming DA, Shaw GD. A sulfated peptide segment at the amino terminus of PSGL-1 is critical for P-selectin binding. Cell. 1995;83:323–331. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90173-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schagger H, von Jagow G. Blue native electrophoresis for isolation of membrane protein complexes in enzymatically active form. Anal Biochem. 1991;199:223–231. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(91)90094-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Snapp KR, Ding H, Atkins K, Warnke R, Luscinskas FW, Kansas GS. A novel P-selectin glycoprotein ligand-1 (PSGL-1) monoclonal antibody recognizes an epitope within the tyrosine sulfate motif of human PSGL-1 and blocks recognition of both P- and L-selectin. Blood. 1998;91:154–164. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Snapp KR, Wagers AJ, Craig R, Stoolman LM, Kansas GS. P-selectin glycoprotein ligand-1 (PSGL-1) is essential for adhesion to P-selectin but not E-selectin in stably transfected hematopoietic cell lines. Blood. 1996;89:896–901. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ushiyama S, Laue TM, Moore KL, Erickson HP, McEver RP. Structural and functional characterization of monomeric soluble P-selectin and comparison with membrane P-selectin. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:15229–15237. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.von Andrian UH, Hasslen SR, Nelson RD, Erlandsen SL, Butcher EC. A central role for microvillous receptor presentation in leukocyte adhesion under flow. Cell. 1995;82:989–999. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90278-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wagers AJ, Stoolman LM, Kannagi R, Craig R, Kansas GS. Expression of leukocyte fucosyltransferases regulates binding to E-selectin. Relationship to previously implicated carbohydrate epitopes. J Immunol. 1997;159:1917–1929. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Walchek B, Moore KL, McEver RP, Kishimoto TK. Neutrophil-neutrophil interactions under hydrodynamic shear stress involve L-selectin and PSGL-1. J Clin Invest. 1996;98:1081–1087. doi: 10.1172/JCI118888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wilkins PP, Moore KL, McEver RP, Cummings RD. Tyrosine sulfation of P-selectin glycoprotein ligand-1 is required for high affinity binding to P-selectin. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:22677–22680. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.39.22677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yang J, Galipeau J, Kozak CA, Furie BC, Furie B. Mouse P-selectin glycoprotein ligand-1: molecular cloning, chromosomal localization and expression of a functional P-selectin receptor. Blood. 1996;87:4176–4186. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]