Abstract

The Saccharomyces cerevisiae DJP1 gene encodes a cytosolic protein homologous to Escherichia coli DnaJ. DnaJ homologues act in conjunction with molecular chaperones of the Hsp70 protein family in a variety of cellular processes. Cells with a DJP1 gene deletion are viable and exhibit a novel phenotype among cytosolic J-protein mutants in that they have a specific impairment of only one organelle, the peroxisome. The phenotype was also unique among peroxisome assembly mutants: peroxisomal matrix proteins were mislocalized to the cytoplasm to a varying extent, and peroxisomal structures failed to grow to full size and exhibited a broad range of buoyant densities. Import of marker proteins for the endoplasmic reticulum, nucleus, and mitochondria was normal. Furthermore, the metabolic adaptation to a change in carbon source, a complex multistep process, was unaffected in a DJP1 gene deletion mutant. We conclude that Djp1p is specifically required for peroxisomal protein import.

Keywords: molecular chaperone, peroxisome, DnaJ, import, Saccharomyces cerevisiae

Peroxisomes are organelles present in most eukaryotic cells. Proteins destined for the peroxisomal matrix are synthesized on free polyribosomes and are imported posttranslationally (Lazarow and Fujiki, 1985). Two types of peroxisomal targeting signals (PTSs)1 have been identified. The PTS1 consists of a COOH-terminal tripeptide consisting of the amino acids serine, lysine, and leucine (SKL) or a derivative thereof (Gould et al., 1988; Purdue and Lazarow, 1994; Elgersma et al., 1996b ). The PTS2 is an NH2-terminal sequence found in a limited number of peroxisomal matrix proteins (Osumi et al., 1991; Swinkels et al., 1991; Purdue and Lazarow, 1994). In addition, some internal targeting sequences have been reported for matrix proteins (Small et al., 1988; Kragler et al., 1993; Elgersma et al., 1995) and for integral membrane proteins (McCammon et al., 1994; Dyer et al., 1996; Elgersma et al., 1997).

Specific cytosolic receptors have been identified for PTS1- and PTS2-containing proteins. These receptors have been proposed to function as cycling receptors (Dodt and Gould, 1996; Elgersma et al., 1996a , 1998; Gould et al., 1996; Rehling et al., 1996), which (a) bind their ligand in the cytoplasm; (b) dock at the peroxisomal membrane; and (c) dissociate from the ligand and return to the cytoplasm. It is unclear whether these receptors dissociate from their ligand at the cytoplasmic surface of the peroxisomal membrane or whether the complex enters the peroxisomal matrix before dissociation.

The actual translocation of polypeptides across the peroxisomal membrane seems to differ from translocation of (partially) unfolded precursor proteins across the ER and mitochondrial membranes. Some peroxisomal proteins have been shown to oligomerize in the cytoplasm before import (Glover et al., 1994; McNew and Goodman, 1994; Elgersma et al., 1996b ; Leiper et al., 1996). Import studies in semi-intact cells and microinjection experiments have revealed that complete protein unfolding is not required for translocation (Walton et al., 1992; Wendland and Subramani, 1993; Walton et al., 1995). In this respect, the peroxisomal protein import process may resemble the nuclear protein import process, where folded and assembled proteins can enter the organelle (Melchior and Gerace, 1995).

Microinjection of an artificial substrate protein (biotinylated human serum albumin coated with PTS1-containing peptides) into fibroblasts revealed the requirement for a cytosolic Hsp70 for association of this protein with peroxisomes (Walton et al., 1994). The Hsp70 chaperone system is involved in a variety of processes including translation, protein degradation, folding and assembly of newly synthesized proteins, and their transport to particular subcellular compartments (Hartl, 1996; Hayes and Dice, 1996). Hsp70s can also regulate the composition of protein complexes (Frydman and Höhfeld, 1997). In eukaryotic cells, different classes of Hsp70 proteins are present that are not functionally interchangeable (Craig et al., 1994).

Hsp70s function in conjunction with partner proteins, among which are the J-domain–containing proteins. This protein family consists of modular proteins that contain an evolutionarily conserved J-domain (first identified in Escherichia coli DnaJ). The J-domain specifies the interaction with a particular Hsp70 (Schlenstedt et al., 1995). Other domains interact with the substrates for the Hsp70 machinery. By combining the J-domain with other protein modules, a J-domain–containing protein can recruit a particular Hsp70 to a site in the cell where it can perform one of its specific tasks (Rassow et al., 1995). Two cytosolic J-proteins have been well characterized in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Sis1p is an essential protein that is required for initiation of translation (Zhong and Arndt, 1993). Ydj1p, on the other hand, is required for import of ER and mitochondrial proteins in vivo (Atencio and Yaffe, 1992; Becker et al., 1996), for Cdc28p-dependent phosphorylation and degradation of Cln3p and for ubiquitin-dependent degradation of short-lived and abnormal proteins (Lee et al., 1996; Yaglom et al., 1996). Δydj1 cells grow very slowly and display pleiotropic morphological defects (Caplan and Douglas, 1991).

We have identified the DJP1 gene by functional complementation of a previously described peroxisome assembly mutant pas22-1 (Elgersma et al., 1993). The DJP1 gene encodes a cytosolic J-domain–containing protein. In contrast to the cytosolic J-domain proteins Sis1p and Ydj1p, Djp1p function is restricted to peroxisomes: Djp1p was dispensible for growth on a wide variety of fermentable and non-fermentable carbon sources, except when peroxisome functioning was required. In Δdjp1 cells, peroxisomal matrix proteins were partially mislocalized to the cytosol and peroxisomes failed to grow to full size. Besides atypical peroxisomal structures, no additional morphological abnormalities were observed. Furthermore, import of proteins into the ER, mitochondria, and nucleus was unaffected in Δdjp1 cells. Our results provide genetic evidence for the involvement of cytosolic chaperones in peroxisomal protein import.

Materials and Methods

Yeast Strains and Culture Conditions

The yeast strains used in this study were S. cerevisiae BJ1991 (Matα, leu2, trp1, ura3-251, prb1-1122, pep4-3, gal2) (Jones, 1977) and BSL1-2C (Leighton and Schatz, 1995). The pex6 deletion mutant was generated in our laboratory (Voorn-Brouwer et al., 1993). The djp1 deletion mutant is described below. Pas22-1 was isolated by Elgersma et al. (1993). Yeast transformants were selected and grown on minimal medium containing 0.67% yeast nitrogen base without amino acids (YNB-WO; DIFCO Laboratories, Detroit, MI), 2% glucose and amino acids (20–30 μg/ml) as needed. The liquid media used for growing cells for nucleic acid isolation, subcellular fractionation, immunogold electron microscopy, and enzymatic assays contained 0.5% potassium phosphate buffer, pH 6.0, 0.3% yeast extract, 0.5% peptone, and either 2% glucose, 3% glycerol or 0.1% oleate/2% Tween 40. Before shifting to these media, the cells were grown on 0.3% glucose medium for at least 24 h. Oleate plates contained 0.67% yeast nitrogen base without amino acids (YNB-WO; DIFCO Laboratories), 0.1% yeast extract (DIFCO Laboratories), 2% agar, 0.1% oleate (vol/vol), 0.25% Tween 40 (vol/vol), and amino acids as needed. For the galactose-induction experiments, cells were grown on YPD and shifted to YPgal (1% yeast extract, 2% bacto peptone, and either 2% glucose or 2% galactose).

Cloning Procedures

The impaired growth of pas22-1 cells on oleate plates was used for cloning of the DJP1 gene by functional complementation with a S. cerevisiae genomic library constructed in Ycp50. Library transformants were selected on low minimal glucose plates and subsequently replica plated onto oleate plates. Complementing plasmids were rescued in E. coli and retransformed to pas22-1 cells to confirm plasmid-linked complementation. One plasmid was selected for further characterization (p22.1). p22.1 was partially digested with Sau3a, size-fractionated into pools of 0.5–1 kb, 1–2 kb, 2–3 kb, 3–4 kb, etc., and cloned into the BamHI site of Ycplac33KanR (van der Leij et al., 1992). From the different library pools, the 1–2-kb pool was still able to complement the mutant. The smallest complementing plasmid from this pool that rescued the mutant contained an insert of 1,200 bp (p22.2). Both strands were sequenced by the dideoxy chain-termination method. The obtained nucleotide and predicted amino acid sequence was compared with the Saccharomyces cerevisiae Genome Database. p22.2 encoded the COOH-terminal part of YIR004w, starting at nucleotide 184.

The DJP1 gene deletion construct was prepared by insertion of the LEU2 gene between the AseI site 212 bp before the start of the DJP1 open reading frame (ORF) and the internal BglII site. This plasmid was linearized and transformed to BJ1991 and BSL1-2C cells. Deletion mutants were selected on leucine-deficient plates and checked by Southern blot analysis for proper integration.

Green fluorescent protein (GFP)-PTS1 and PTS2-GFP expression plasmids were constructed by cloning either a BamHI–XbaI fragment or a filled-in HindIII–XbaI fragment from pSM102 and pJM205 (Kalish et al., 1996) into pEL44, respectively, thereby creating pEW88 and pFM1. pEL44 is derived from a centromere-containing URA3 plasmid (Gietz and Sugino, 1988) containing the oleate-inducible catalase A promoter and 3′ UTR (Elgersma et al., 1993).

Plasmids encoding preproα-factor and Suc2 (invertase) fusions with GFP-HDEL were prepared as follows. An EagI restriction site upstream of the GFP translation initiation codon and the last nine codons of Kar2p, including the ER retention signal HDEL, were added to GFP ORF by PCR with the following oligonucleotides: EAG1 primer, TTTTCGGCCGAAAAGATGAGTAAAGGAGAAGAACTT; HDEL primer, TTTAAGCTTACAATTCGTCGTGTTCGAAATAATCACCTTTGTATAGTTCATCCATGC. The PCR product was digested with HindIII and EagI and cloned into PSY1 and PSY16 (Harmsen et al., 1993) yielding the plasmids pEW109 and pEW110. Subsequently, SacI–HindIII fragments from pEW109 and pEW110 were cloned into pEW70, a pEL44 derivative containing a TRP1-selectable marker (Hettema et al., 1996) yielding the plasmids pEW111 and pEW112 for oleate-dependent expression of preSuc2-GFP-HDEL and preproα-GFP-HDEL. NLS-GFP was constructed by cloning GFP into pGAD (Shulga et al., 1996). The plasmid encoding NH2-tagged Mdh3p was described before (Elgersma et al., 1996a ).

Production of Djp1p Polyclonal Antiserum

Part of Djp1p was expressed in E. coli by cloning a PstI fragment of the DJP1 gene (encoding the COOH-terminal part starting at amino acid residue 137) in plasmid pQE-10 (QIAGEN Inc., Chatsworth, CA). The six histidine residues fused to the Djp1p fragment allowed rapid purification by nickel-chelating chromatography under denaturing conditions according to the manufacturer's instructions. The protein was further purified by SDS-PAGE, visualized with 0.25 M KCl/1 mM DTT, and subsequently excised and eluted in 50 mM Tris/HCl (pH 8.0)/0.1% SDS/0.1 mM EDTA/ 5 mM DTT/0.15 M NaCl, and then was used to immunize rabbits.

Nycodenz Gradients

A four-step floatation gradient was made. An organellar 17,000 g pellet was resuspended in 400 μl 50% Nycodenz in gradient buffer (5 mM MES (pH 5.5)/1 mM KCl/1 mM EDTA/1 mM PMSF) and transferred to a Beckman tube. This pellet fraction was overlaid with 1.6 ml of 40% Nycodenz, 1.6 ml 30% Nycodenz, and 1.6 ml of 0% Nycodenz in gradient buffer containing 0.65 M sorbitol, and then centrifuged for 18 h at 150,000 g at 4°C, and fractions were analyzed by Western blotting. In the same experiment, an organellar pellet was resuspended in 0.65 M sorbitol in gradient buffer and applied on top of the step gradient and centrifuged in parallel.

Nycodenz gradients presented in Fig. 6 are continuous 16–35% Nycodenz equilibrium density gradient (12 ml), with a cushion of 1 ml 42% Nycodenz dissolved in gradient buffer containing 8.5% sucrose. The sealed tubes were centrifuged during 2.5 h in a vertical rotor (MSE 8×35) at 19,000 rpm (29,000 g) at 4°C. Fractions were analyzed for marker proteins with activity measurements or Western blotting.

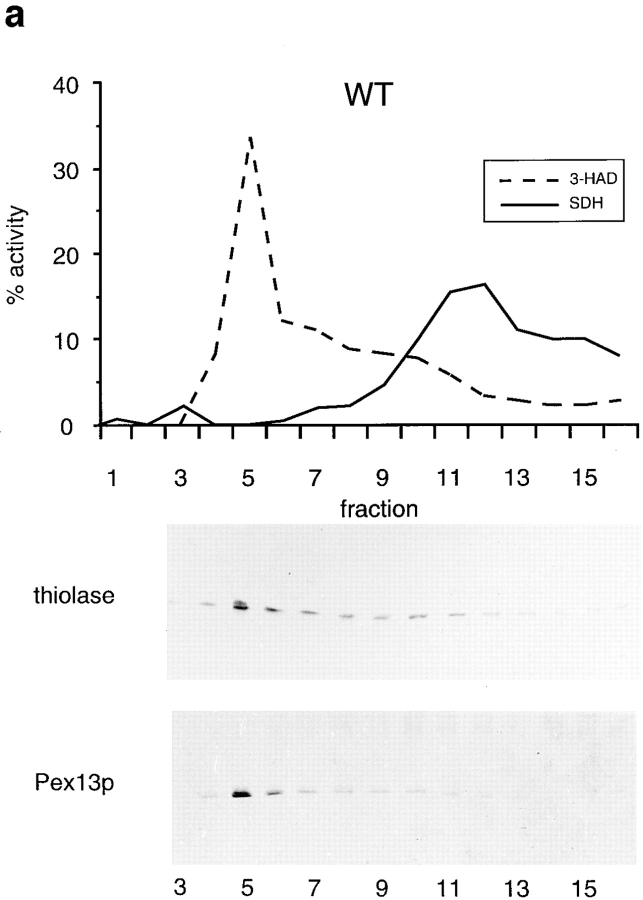

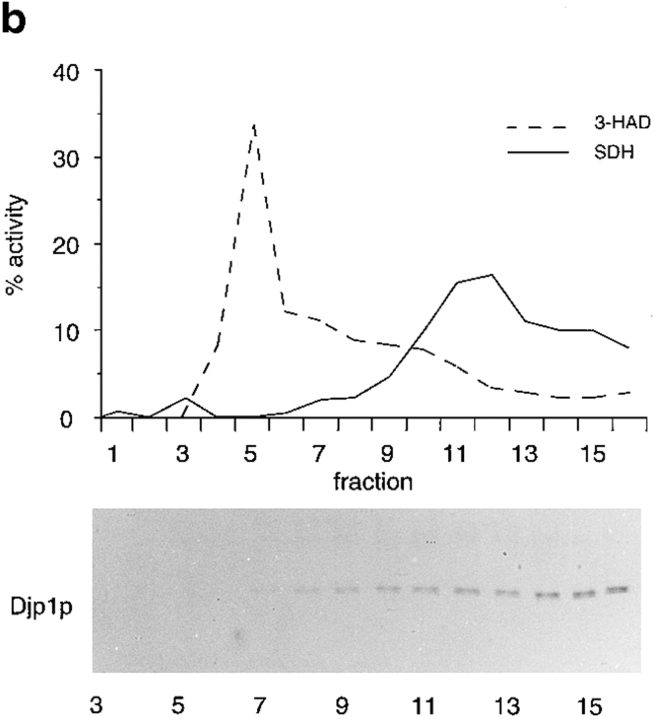

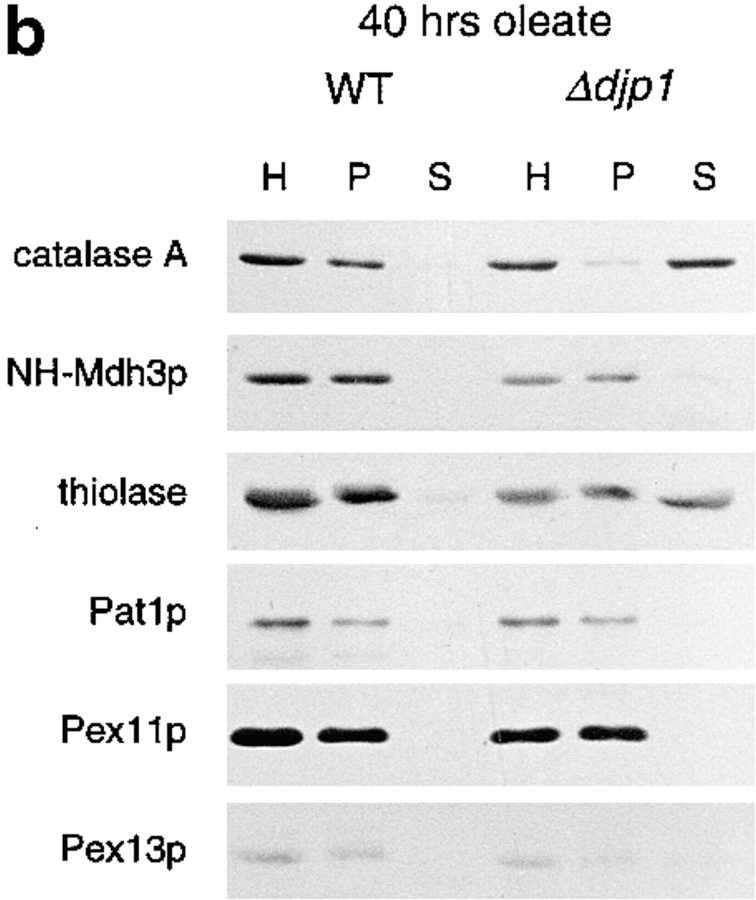

Figure 6.

Δdjp1 cells contain low buoyant density peroxisomes. Nycodenz density equilibrium centrifugation of a 17,000 g pellet prepared from wild-type (a) or Δdjp1 (b) cell homogenates. Cells were grown on oleate for 16 h. Graphs show distribution of the mitochondrial marker succinate dehydrogenase (SDH, solid line) and the peroxisomal marker 3-hydroxyacyl-CoA dehydrogenase activity (3-HAD, dashed line). The distribution of thiolase and Pex13p, determined by Western blot analysis, in a Nycodenz density gradient prepared in parallel is shown for comparison. Δdjp1 peroxisomal structures equilibrated at lower buoyant density and were more heterogeneously distributed over the gradient than wild-type peroxisomal structures.

Protease Protection, SDS-PAGE and Western Blotting

Cells grown overnight on oleate medium were converted to spheroplasts with Zymolyase 100T (1 mg/g cells). The spheroplasts were washed twice in 1.2 M sorbitol in gradient buffer. The washed spheroplasts were lysed by osmotic shock in 0.65 M sorbitol in gradient buffer. Intact cells and nuclei were removed from the homogenate by two centrifugation steps at 600 g for 10 min. For protease protection experiments, 100 μl of homogenate with a protein concentration of 1 mg/ml was added to 100 μl 0.65 M sorbitol in gradient buffer containing proteinase K (100 μg) either in the presence or absence of 0.3% Triton X-100. The samples were incubated at room temperature for 0, 15, or 30 min. The reaction was stopped by the addition of TCA (10%). Samples were analyzed by Western blotting. Western blots were incubated with rabbit polyclonal antisera raised against the various proteins. Antibody complexes were either detected by incubation with goat anti–rabbit Ig-conjugated alkaline phosphatase or peroxidase.

Pulse-Chase Experiments

To study protein import into the ER, exponentially growing cells were harvested and resuspended into 600 μl of fresh 2% minimal glucose medium at OD600 = 20. Cells were preincubated at 37°C for 30 min to inactivate Sec62p in Sec62ts cells. Subsequently, 100 μCi of [35S]methionine/ [35S]cysteine was added and cells were incubated at 28°C for 5 min. The chase was started by the addition of 6 mM each of unlabeled methionine and cysteine to the reaction mixture followed by further incubation at 28°C for 0, 5, or 30 min. Chase reactions were stopped on ice. To prepare glass bead lysates, cells were harvested and resuspended in 250 μl PBS/ 0.5% Triton X-100/20 mM NEM/1 mM PMSF. After addition of 100 μl glass beads, cells were vortexed for 30 min at maximal speed at 4°C. Glass beads and cell debris were removed by centrifugation at 17,000 g for 2 min at 4°C. 100 μl of supernatant was used for immunoprecipitation with 10 μl anti-Kar2p rabbit polyclonal antiserum and 50 μl protein A–Sepharose. Incubations were performed overnight at 4°C. Immunoprecipitates were washed twice with 10 mM Tris/HCl, pH 8.6, containing 300 mM NaCl, 0.05% Triton X-100, and 0.1% SDS, and were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and fluorography.

For protein import studies into mitochondria the same conditions were used as described above, except that cells were not preincubated at 37°C. In addition, 0.02% azide was added after each chase time point before cells were put on ice, 5 μl anti-Hsp60 rabbit polyclonal antiserum was used, and immunoprecipitates were washed twice with 100 mM Tris/HCl, pH 8.6, containing 300 mM NaCl, 0.05% Triton X-100, and 0.05% SDS.

Galactose Induction Experiment

For these experiments, we used the S. cerevisiae strain BSL1-2c and BSL1 djp1::leu2, because our wild-type strain BJ1991 is GAL2− (Jones, 1977). Cells were grown in YPD medium (late log phase) before inoculation (OD600 = 0.25–0.3) in YPgal. After each time point, the OD600 was measured and cells were washed and frozen at −20°C before glass bead lysates (in PBS/0.5% Triton X-100/1 mM PMSF) were prepared. Galactose-1-phosphate uridylyltransferase activity was measured by a spectrophotometric assay (Pesce et al., 1977).

Miscellaneous

3-Hydroxyacyl-CoA dehydrogenase activity was measured on a Cobas-Fara centrifugal analyzer by following the 3-keto-octanoyl-CoA–dependent rate of NADH consumption at 340 nm (Wanders et al., 1990). Succinate dehydrogenase activity was measured according to Munujos et al. (1993). Protein concentrations were determined by the bicinchoninic acid method (Smith et al., 1985). Subcellular fractionations were performed as described (Van der Leij et al., 1992). Organellar pellets (17,000 g pellets) were used for continuous Nycodenz gradients as described (van Roermund et al., 1995). DNA manipulations were performed as described (Sambrook et al., 1989). Immunogold electron microscopy was done as described (Distel et al., 1988). Nuclear import assays were performed as described by Shulga et al. (1996).

Results

Cloning and Expression of the DJP1 Gene

We have identified the DJP1 gene by functional complementation of the peroxisome assembly mutant pas22-1 (see Materials and Methods). DJP1 is identical to YIR004w, a 432–amino acid ORF on chromosome IX, identified during the course of the S. cerevisiae genome sequencing project (Voss et al., 1995). We deleted the YIR004w gene and allowed the disruption mutant to mate with pas22-1 cells. Both the diploid cells and the haploid gene deletion mutant showed the same growth characteristics as pas22-1 cells. Growth on oleic acid–containing medium was retarded, whereas growth on all other carbon sources (glucose, galactose, glycerol, acetate, and ethanol) was normal (not shown). In pas22-1 cells, we found a single base pair deletion (G1129) in the DJP1 gene. This alteration caused a frame shift at codon 376 resulting in premature termination of the ORF. These results identified YIR004w as the DJP1 gene. A polyclonal antiserum raised against the COOH-terminal 294–amino acid residues of Djp1p recognized Djp1p specifically on a Western blot (Fig. 1, lane 1), and this protein band was absent from Δdjp1 cell lysates (Fig. 1, lane 2). As expected, pas22-1 cells expressed a low molecular weight version of the DJP1 gene (Fig. 1, lane 3).

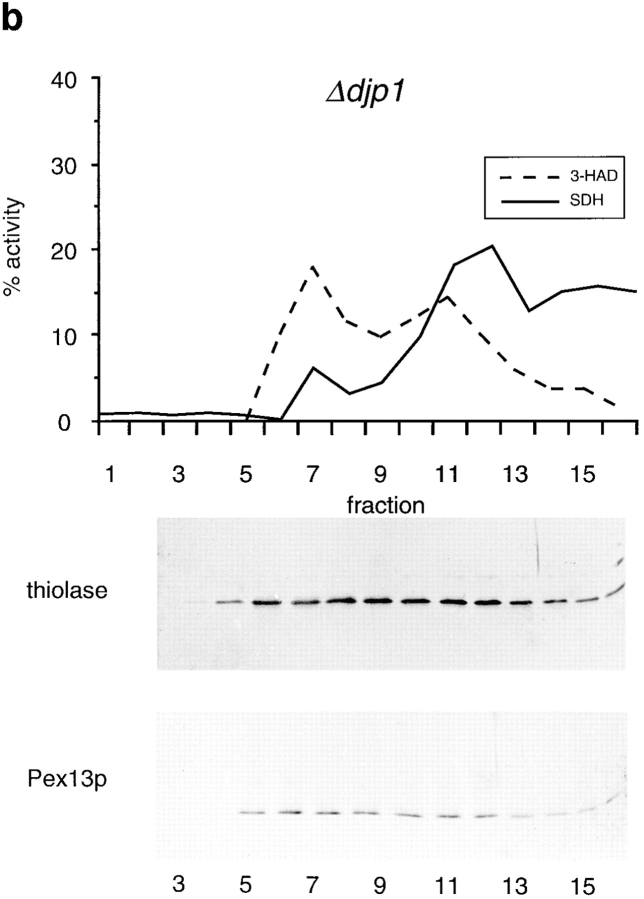

Figure 1.

Western blot analysis of DJP1 gene products. Lysates from wild-type, Δdjp1, and pas22-1 cells grown overnight on oleate-contaning medium were used for Western blot analysis (left panel) or lysates from wild-type cells grown overnight on medium containing glucose, glycerol, or oleate or from cells subjected to heat-shock treatment (right panel). Arrowhead, wild-type Djp1p. Asterisk, truncated Djp1p.

Since growth of Δdjp1 cells was retarded only on oleate media, we anticipated a role for Djp1p in peroxisome biogenesis. Peroxisome number and peroxisomal protein levels are regulated in response to fatty acids (oleate) in the media. The expression level of Djp1p, however, was constitutive; it was unaffected by culture conditions or heat shock (Fig. 1, lanes 4–7).

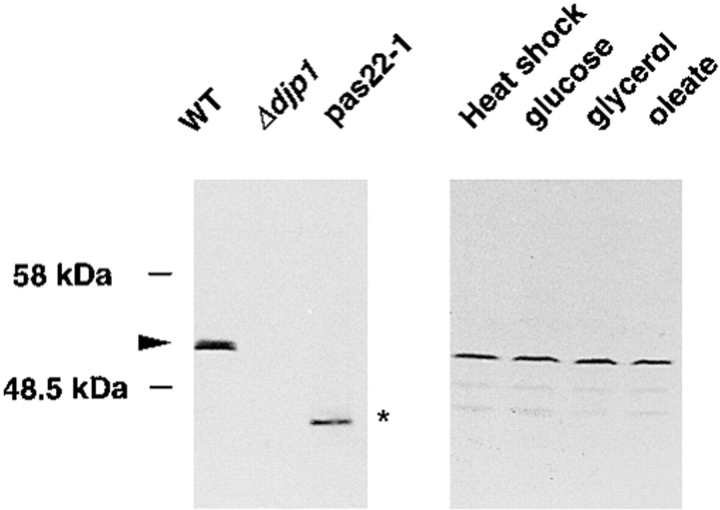

Djp1p contains an NH2-terminal J-domain (Fig. 2, A and B). This 70–amino acid domain is conserved throughout evolution and is named after E. coli DnaJ. EcDnaJ consists of several additional evolutionarily conserved domains, which Djp1p does not have (Fig. 2 A). Instead, Djp1p contains two predicted domains of unknown function.

Figure 2.

Djp1p is a member of a novel subfamily of J-domain– containing proteins. (A) Schematic representation of the modular structure of Djp1p compared with E. coli DnaJ. According to the ProDom database (Gouzy et al., 1996), which makes use of the domainer algorithm (Sonnhammer and Kahn, 1994), Djp1p consists of three conserved domains. It belongs to a subfamily of J-domain–containing proteins with a modular organization different from that of other DnaJ homologues. The typical G domain, cysteine-rich region (CRR) and COOH-terminal domain are absent. Instead, two conserved blocks of amino acids are observed. Block X (Domain ID: 8587, Prodom34) consists of ∼170 amino acid residues and has been found in Djp1p (sw P40564), Caj1p (Mukui et al., 1994; sw P39101), and Yay1p (sw Q10209). Block Y (Domain ID: 7042, Prodom34) has been found in Djp1p, Caj1p, Yay1p, PfRESA1p (sw P13830), and AtDnaJ-like protein (these sequence data are available from GenBank/EMBL/DDBJ under accession number Y11969). (B) Amino acid sequence comparison of the J-domain (Prosite PS00636) of Djp1p with the J-domain of EcDnaJ (sw P08622), and the S. cerevisiae J-domain–containing proteins Scj1p (P25303), Mdj1p (P35191), Sis1p (P25294), Ydj1p (P25491), and Caj1p. Amino acids identical to Djp1p are indicated with black boxes.

Localization of Djp1p in the Cytosol

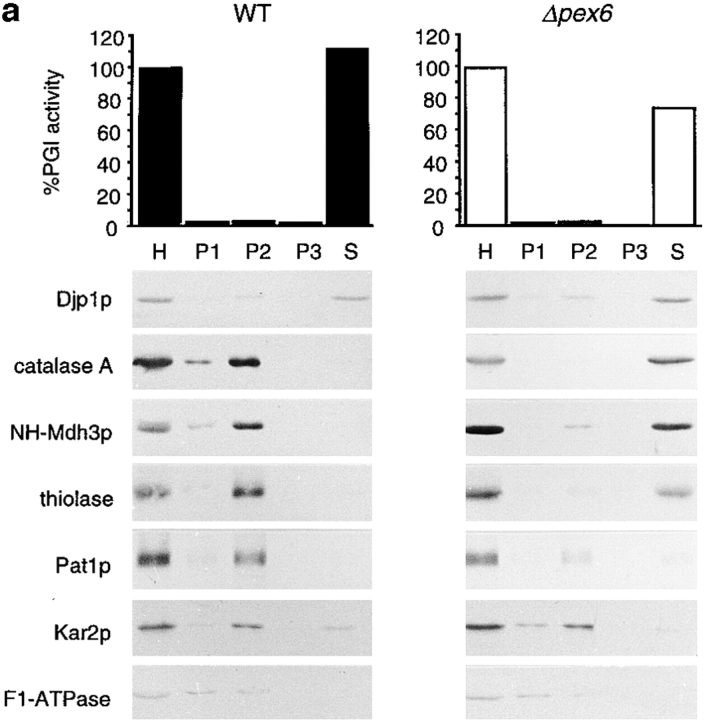

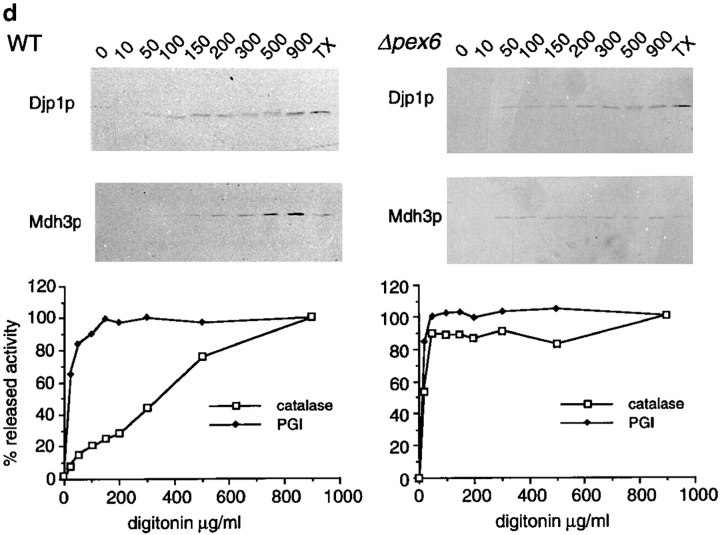

Using subcellular fractionation experiments, we studied the subcellular localization of Djp1p in cells grown overnight on oleic acid medium (Fig. 3 a). A homogenate (H) was prepared from spheroplasts by gentle osmotic lysis and fractionated by successive differential centrifugation into a 2,500 g pellet (P1), a 17,000 g pellet (P2), a 100,000 g pellet (P3) and a supernatant fraction (S) (Fig. 3 a). All four fractions were analyzed for the presence of organellar marker proteins, either by Western blot analyses or by enzymatic activity measurements. F1β-ATPase, Kar2p, and phosphoglucose isomerase (PGI) were used as markers for mitochondria, ER, and cytosol, respectively. We used peroxisomal catalase (catalase A), peroxisomal malate dehydrogenase (Mdh3p) and 3-ketoacyl-CoA thiolase (thiolase) as marker proteins for the peroxisomal matrix and the peroxisomal ABC transporter protein 1 (Pat1p) as marker for the peroxisomal membrane.

Figure 3.

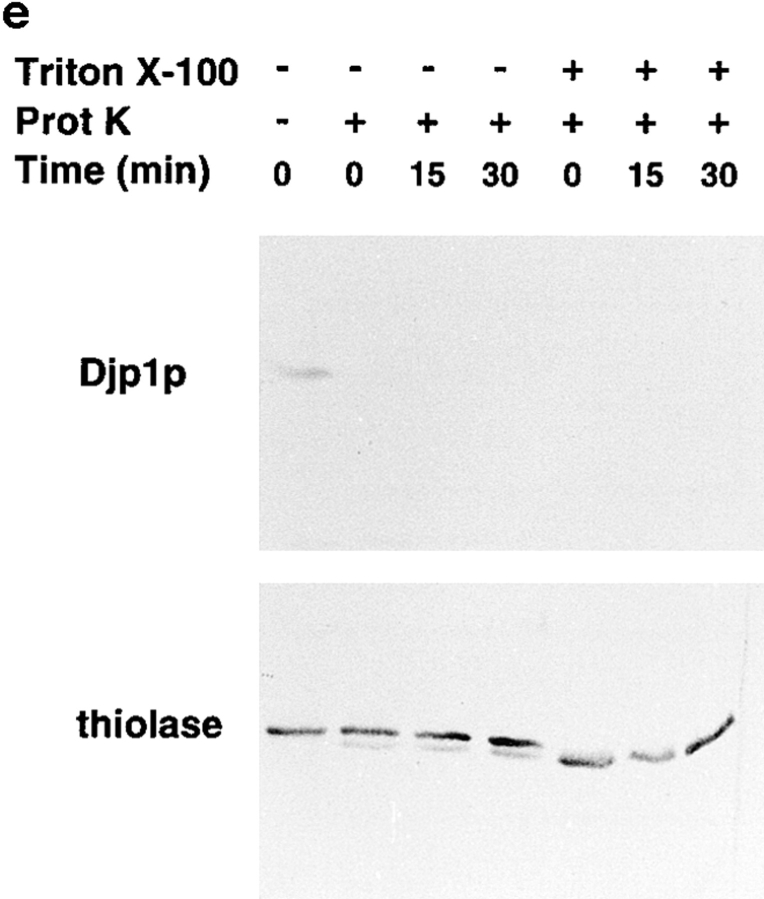

Djp1p is located in the cytosol. (a) Subcellular fractionation experiments showing that Djp1p was localized to the cytosolic fraction of oleate-grown wild-type and Δpex6 cells. A cell-free homogenate (H) was fractionated by successive differential centrifugation into a 2,500 g pellet (P1), a 17,000 g pellet (P2), a 100,000 g pellet (P3) and a 100,000 g supernatant (S). The cytosolic marker, phosphoglucose isomerase activity (PGI) was detected by enzymatic activity. Markers for other compartments were detected by Western blot analysis. ER and mitochondrial markers are Kar2p and F1β-ATPase, respectively. Peroxisomal matrix markers are catalase A, NH2-tagged Mdh3p and thiolase, and the peroxisomal membrane marker is Pat1p. (b) Nycodenz equilibrium density centrifugation of P2 prepared from cells grown on oleate for 16 h. Graph shows distribution of the mitochondrial marker succinate dehydrogenase (SDH, solid line) and the peroxisomal marker 3-hydroxy-acyl-CoA dehydrogenase activity (3-HAD, dashed line). The distribution of Djp1p was determined by Western blot analysis. (c) Particulate Djp1p is partially membrane associated. P2 prepared from wild-type cells was analyzed by Nycodenz floatation gradient centrifugation. Fraction 1 is at the bottom and fraction 10 is at the top of the gradient. B represents precipitated material at the bottom of the gradient. Fractions were analyzed by Western blotting. (d) Digitonin titration experiments showing that most Djp1p was released upon selective permeabilization of the plasma membrane. Wild-type and Δpex6 cells transformed with an NH2-MDH3 expression plasmid were grown on oleate, converted to spheroplasts, and subsequently incubated with increasing digitonin concentrations. Released proteins were analyzed by Western blotting or by activity measurements. Released enzymatic activities from Triton X-100–lysed cells were set at 100%. (e) Djp1p is sensitive to proteinase K in a homogenate prepared from wild-type cells grown on oleate. A homogenate was incubated with proteinase K either in the presence or absence of Triton X-100. Djp1p and thiolase were detected by Western blot analysis.

The fractionation profile of Djp1p was different from that of mitochondrial, peroxisomal and ER proteins. The bulk of Djp1p cofractionated with the cytosolic marker PGI in the 100,000 g supernatant (S) (Fig. 3 a) or even in a 200,000 g supernatant (not shown), indicating that Djp1p is a cytosolic protein. However, a fraction of Djp1p was pelleted at 17,000 g (P2). P2 contained a very low amount of PGI activity suggesting a marginal cytosolic contamination of P2, but this was not sufficient to explain the presence of Djp1p in P2. Djp1p was not necessarily associated with functional peroxisomes as Djp1p was also found in the 17,000 g pellet from cells that lack morphologically distinguishable peroxisomes, the Δpex6 cells (Fig. 3 a) and Δpex13 cells (not shown). The fractionation behavior of Djp1p was identical in glucose-grown cells.

We next aimed to identify the nature of the pelletable Djp1p fraction. The 17,000 g pellet derived from wild-type cells was therefore subjected to Nycodenz equilibrium density gradient centrifugation followed by Western blot analysis. In this gradient, Djp1p did not colocalize with peroxisomes and mitochondria but remained in the low density fractions (Fig. 3 b). The pelletable fraction of Djp1p apparently associated with a large structure, either as part of a protein complex or associated with membranes. To distinguish between these two possibilities, we prepared a 17,000 g organellar pellet from wild-type cells, resuspended it in 50% Nycodenz (wt/vol) and layered the suspension at the bottom of a Nycodenz floatation step gradient (see Materials and Methods). Membranes were floated to light density by overnight centrifugation at 150,000 g as monitored by the distribution of the organellar marker proteins (Fig. 3 c). The majority of Djp1p molecules migrated up into the gradient (Fig. 3 c, peak in fraction 8) implying its association with membranes. The Djp1p equilibration profile was distinct from that of peroxisomes, which peaked in fraction 5 (Fig. 3 c). Mitochondria and microsomes migrated with the bulk of the membranes to fractions 5–8, with a peak in fractions 7 and 8. We concluded that Djp1p was associated with membranes that overlap in density with, but are distinct from, the bulk of peroxisomes, mitochondria, and microsomes.

Since proteins may dissociate from membranes or from protein assemblies during homogenization of cells and subsequent subcellular fractionation, we wanted to confirm our results on the subcellular localization of Djp1p using a milder method. Spheroplasts prepared from oleate-grown cells were incubated with increasing concentrations of digitonin and the release of marker proteins was measured. At low digitonin concentrations, the plasma membrane was permeabilized selectively as monitored by the release of the cytosolic marker protein PGI (Fig. 3 d) with simultaneous retention of organellar markers. At higher digitonin concentrations intracellular membranes were permeabilized, upon which catalase and NH2-Mdh3p were released from the cells. Djp1p started to be released from cells at low digitonin concentrations, initially coeluting with PGI. However, by increasing the digitonin concentration gradually, more Djp1p was released. This illustrates that most of Djp1p behaved as a soluble cytosolic protein, whereas the rest was retained until digitonin concentrations were reached that solubilized intracellular membranes completely. The use of different carbon sources for growth did not affect the retarded release of Djp1p from digitonin-permeabilized cells (not shown). Furthermore, the more digitonin-resistant pool of Djp1p was not necessarily associated with functional peroxisomes, since the retarded release was also observed in digitonin-permeabilized Δpex6 cells (Fig. 3 d).

To firmly establish the cytosolic localization of Djp1p, and to determine whether the membrane-associated pool of Djp1p was located on the cytosolic side of the membranes, we used a third approach. We tested latency of the protein in a cell homogenate using protease digestion (Fig. 3 e). We therefore prepared detergent-free homogenates from wild-type cells, and treated them with proteinase K to degrade proteins that are not protected by a membrane. The control peroxisomal matrix protein thiolase was completely protected from digestion by the protease, whereas upon addition of the detergent Triton X-100 to open up the peroxisomal membranes, thiolase was cleaved (Fig. 3 e). Thiolase contains a single protease-sensitive site that is rapidly cleaved upon exposure to protease, whereas the remaining proteolytic product is protease resistant (Höhfeld et al., 1991). In contrast to thiolase, Djp1p was degraded rapidly and quantitatively by Proteinase K both in the absence and presence of Triton X-100. These experiments confirm and extend our differential centrifugation experiments and digitonin titration experiments that indicate that Djp1p was not incorporated into organelles. It appears mainly as a cytosolic protein, with a fraction associated with the cytosolic side of membranes.

Mislocalization of PTS-containing GFP in Δdjp1 Cells

The growth deficiency of Δdjp1 cells was restricted to media containing fatty acids as sole carbon source, which is suggestive of a defect in peroxisome functioning. To investigate whether peroxisome biogenesis was indeed affected in Δdjp1 cells, we determined whether proteins with a peroxisomal targeting signal can be imported into peroxisomes in these cells. We used both a PTS1- and a PTS2-containing variant of the GFP from the jellyfish Aequorea victoria (Kalish et al., 1995). The cDNAs encoding these proteins were cloned into a yeast expression vector containing the oleate-inducible regulatory sequence of the catalase A (CTA) gene (Elgersma et al., 1993). Cells transformed with the GFP-PTS1 or PTS2-GFP expression plasmids were grown to late logarithmic phase on selective glucose medium, and then transferred to oleate medium and analyzed 24 h later (Fig. 4).

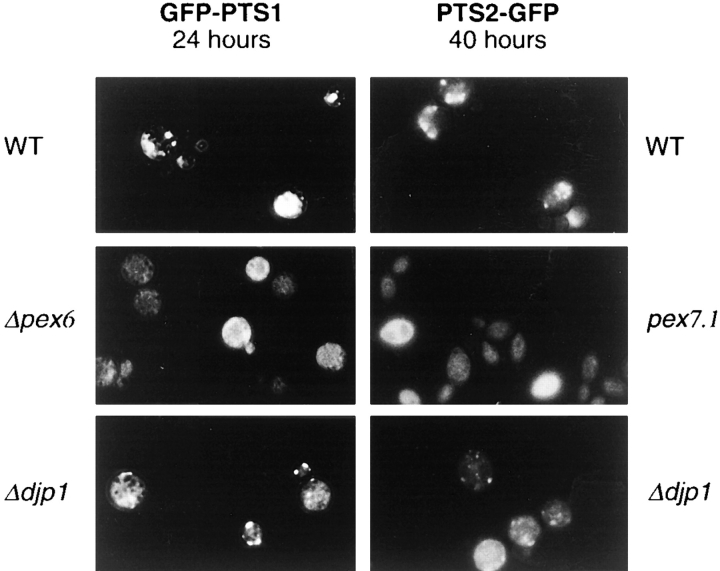

Figure 4.

Ddjp1 cells partially mislocalize GFP-PTS1 and PTS2-GFP and show aberrant morphology of peroxisomal structures after prolonged growth on oleate media. Distribution of GFP containing a PTS1 or PTS2 in wild-type cells, Δdjp1 cells, and either Δpex6 cells or pex7.1 cells grown on oleate-containing medium. Expression of the fusion proteins was under control of the oleate-inducible catalase A promoter. Cells expressing GFP-PTS1 were photographed 24 h after the shift to oleate medium. Cells expressing PTS2-GFP were photographed 40 h after the shift. Results for GFP-PTS1 and PTS2-GFP were indistinguishable.

In wild-type cells transformed with either construct, a few large clusters of fluorescent spots were present, indicating that both proteins efficiently entered peroxisomes (Fig. 4). In Δdjp1 cells, however, a punctate fluorescence pattern reminiscent of peroxisomes was observed against a background of pronounced diffuse labeling for both proteins. Prolonged culturing of wild-type cells on oleate media resulted in the formation of very large fluorescent structures, which were absent from Δdjp1 cells for both GFP-PTS1 (not shown) and PTS2-GFP (Fig. 4). Instead, the diffuse labeling of the cells increased and the peroxisomes remained small. We concluded that in Δdjp1 cells, only a fraction of PTS-containing GFP is associated with peroxisomes whereas the rest is mislocalized to the cytosol. After prolonged culture on oleate medium, atypically small peroxisomal structures are present in Δdjp1 cells.

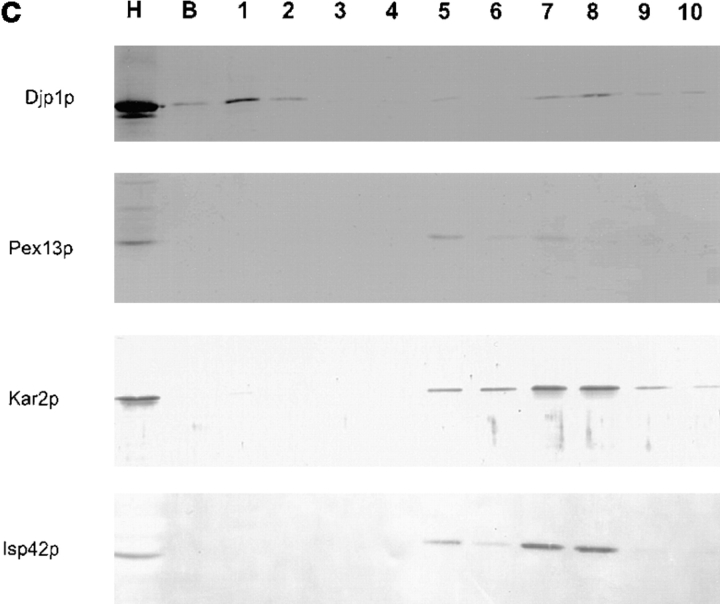

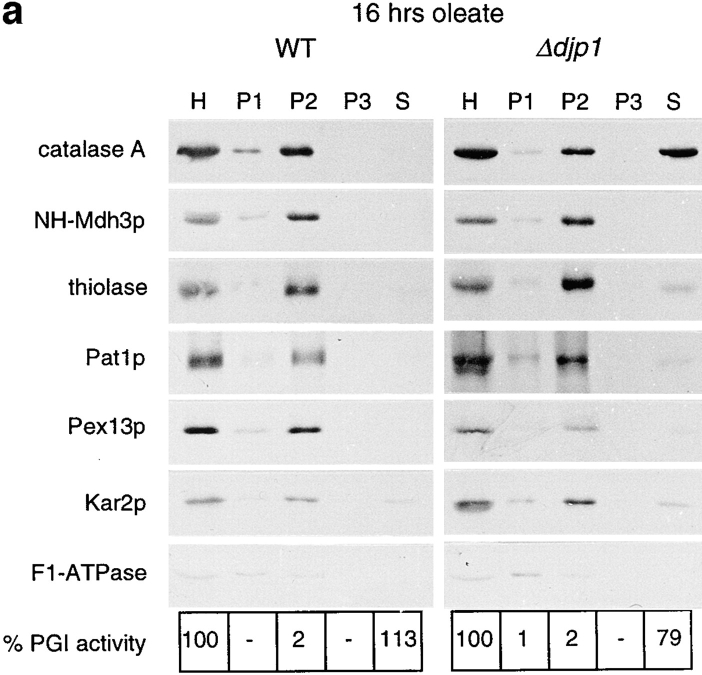

Mislocalization of Peroxisomal Matrix Proteins in Δdjp1 Cells

To extend and confirm the results with GFP for endogenous peroxisomal proteins, and to determine whether the effects of DJP1 deletion are specific for the peroxisome, we examined the subcellular distribution of marker proteins for cytosol (PGI), mitochondria (F1β-ATPase), ER (Kar2p), and peroxisomes (catalase A, NH-Mdh3p as a typical PTS1 marker protein, thiolase as PTS2 marker protein, and Pat1p and Pex13p as markers for the peroxisomal membrane). Cells were grown for 16 h on oleate medium to allow optimal peroxisome induction and then fractionated as shown in Fig. 5. Whereas marker proteins for ER and mitochondria fractionated in Δdjp1 cells as in wild-type cells, the peroxisomal marker protein catalase A behaved clearly differently (Fig. 5 a). In contrast, NH-Mdh3p, thiolase, and the membrane proteins Pat1p (Fig. 5 a) and Pex13p were located mainly in the 17,000 g pellet (P2) of Δdjp1 cells. Hence, after 16 h growth on oleate, the most pronounced defect in Δdjp1 cells was the mislocalization of catalase A to the cytosolic fraction.

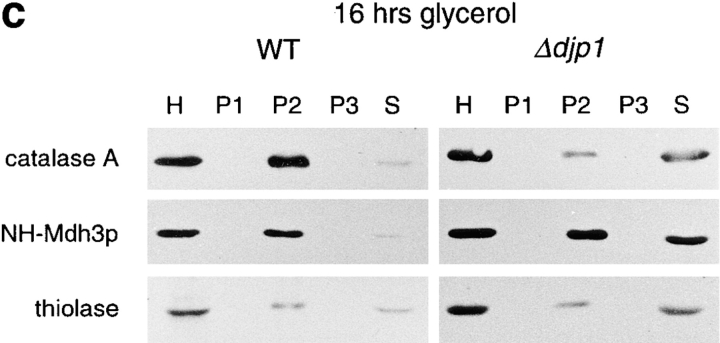

Figure 5.

Mislocalization of peroxisomal matrix proteins in Δdjp1 cells depends on growth conditions. Subcellular distribution of marker proteins of wild-type and Δdjp1 cells grown (a) on oleate for 16 h, (b) on oleate for 40 h, and (c) on glycerol medium for 16 h. (a and c) Subcellular fractionation was performed as in Fig. 3 a. (b) Subcellular fractionation by differential centrifugation of a homogenate (H) into a 17,000 g pellet (P) and 17,000 g supernatant (S). Marker proteins for various cellular compartments were as in Fig. 3 a. In addition to Pat1p, Pex11p and Pex13p were used as peroxisomal membrane markers. The wild-type panel in a, which is the same as in Fig. 3 a, is included for comparison.

Since we had observed that the cytosolic labeling of GFP-PTS1 and PTS2-GFP increased with time after the shift to oleate medium, we wanted to find out whether the mislocalization of endogenous peroxisomal matrix proteins in Δdjp1 cells was dependent on cellular growth conditions as well. We grew Δdjp1 cells on oleate for 40 h and compared the distribution of peroxisomal marker proteins between the 17,000 g organellar pellet and the supernatant fraction (Fig. 5 b). Under these conditions, catalase A was recovered almost completely in a 17,000 g supernatant fraction. Moreover, thiolase was now also present in the supernatant fraction whereas NH-Mdh3p and the peroxisomal membrane proteins remained completely particulate.

The same experiment was performed with cells grown overnight on glycerol-containing medium (Fig. 5 c). These cells showed the most defective phenotype, with extensive mislocalization of NH2-Mdh3p as well as catalase A and thiolase. Our results indicate that the extent to which peroxisomal proteins cofractionated with the cytosolic marker protein varied with growth conditions in Δdjp1 cells. Optimal oleate induction partially restored the Δdjp1 phenotype. The level of Djp1p itself was not regulated in response to oleate in the medium and, inversely, the oleate response was not impaired in Δdjp1 cells as determined by the level of activity of peroxisomal β–oxidation enzymes (not shown). These results suggest that either Djp1p was functionally replaced by an oleate-inducible factor or the function of Djp1p was needed less under conditions of optimal oleate induction. Interestingly, serial analysis of gene expression (SAGE) of wild-type cells grown on oleate for 16 h revealed the induction of several heat-shock proteins that may render Djp1p partially redundant (Kal, A.J., and H.F. Tabak, personal communication).

Under both growth conditions, oleate as well as glycerol, marker proteins for ER, mitochondria and cytosol behaved as in wild-type cells (Fig. 5 a; and results not shown), indicating that the effects of DJP1 gene deletion were limited to peroxisomes (see below).

Low-Density Peroxisomal Structures in Δdjp1 Cells

To further characterize the peroxisomes in Δdjp1 cells, especially considering the punctate pattern shown in Fig. 4, we determined their density in a Nycodenz gradient. Fractionation of a 17,000 g pellet (P2) of either wild-type or Δdjp1 cells by Nycodenz equilibrium density gradient centrifugation revealed that the peroxisomal matrix protein thiolase comigrated with the peroxisomal membrane proteins Pex13p (Fig. 6) and Pat1p (not shown) in Δdjp1 cells. In contrast to peroxisomes in wild-type cells, which equilibrated at high density, the peroxisomes in Δdjp1 cells equilibrated at a broad density range, the bulk of them having a lower density than the peroxisomes in wild-type cells (Fig. 6).

Residual Protein Import into Small Spherical Peroxisomes in Δdjp1 Cells

The biochemical experiments revealed a partial association of matrix proteins with peroxisomes in Δdjp1 cells, and direct immunofluorescence suggested a partial peroxisomal localization for the GFP-PTS proteins. To determine whether these matrix proteins were indeed imported into the organelle, or whether they were just associated with the peroxisomal surface, we performed immunogold electron microscopy studies. The localization of CTA and NH2-Mdh3p in Δdjp1 cells was studied (Fig. 7 a). Antisera directed against NH2-Mdh3p (Fig. 7 a, large gold particles) and catalase A (small gold particles) specifically labeled the peroxisomal matrix in Δdjp1 cells, showing that matrix proteins were indeed imported into the peroxisomes of Δdjp1 cells.

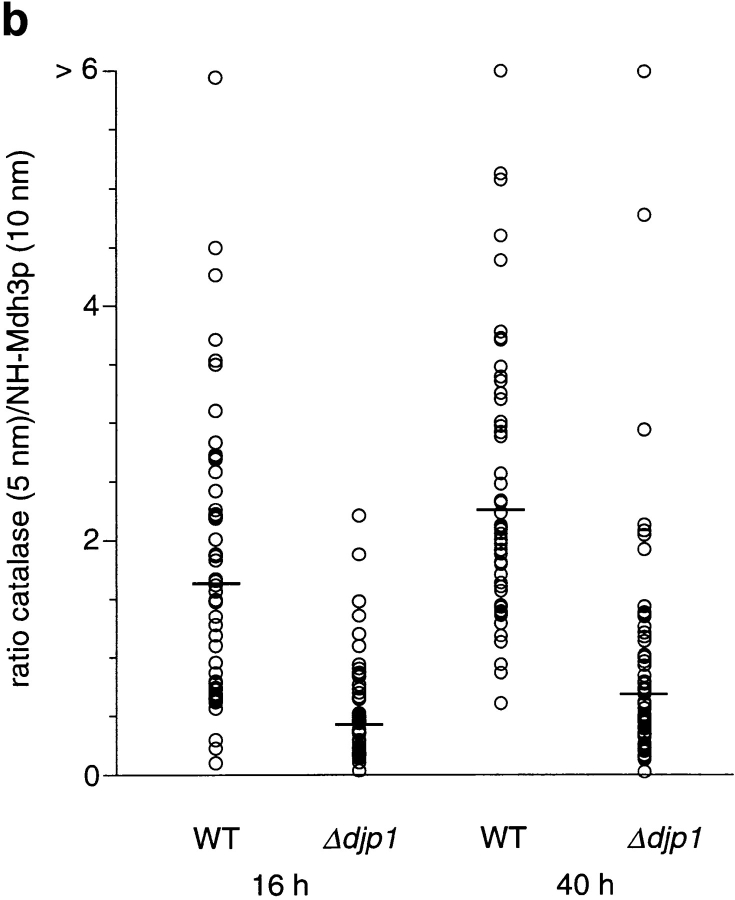

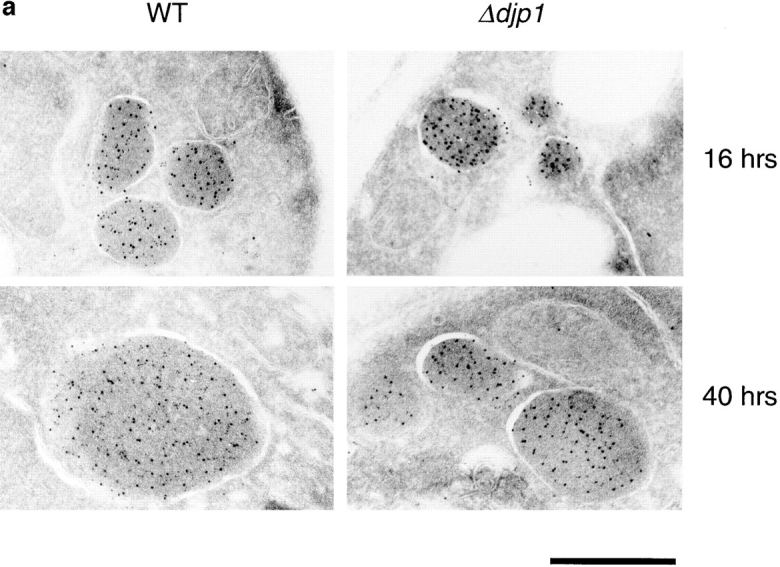

Figure 7.

Peroxisomes of Δdjp1 cells are small and contain relatively little catalase. (a) Immunogold electron micrograph of wild-type (WT) and Δdjp1 cells expressing NH2-Mdh3p grown on oleate for 16 and 40 h. Small gold particles (5 nm) represent catalase A, large gold particles (10 nm) represent NH2-Mdh3p. (b) Ratio of small gold particles/large gold particles per peroxisome. For every condition 60 peroxisomes were analyzed. Bar, 0.5 μm.

In cross-sections of Δdjp1 cells grown on oleate for 40 h, peroxisomal structures were scarce and relatively small. As our subcellular fractionation studies predicted, the ratio of small gold particles (representing CTA) to large gold particles (NH2-Mdh3p) was much higher in wild-type cells than in Δdjp1 cells (Fig. 7, a and b). Hence, the amount of CTA relative to the amount of NH2-Mdh3p was low in peroxisomes of Δdjp1 cells when compared with wild-type cells.

Specificity of Djp1p for Peroxisomal Protein Import

Peroxisomes are indispensable for growth on oleate media but are not necessary for growth on other carbon sources such as glucose, glycerol, acetate, and ethanol. Peroxisomal protein import mutants therefore have been identified based on these growth characteristics. Disturbances of protein import into the endoplasmic reticulum (Novick et al., 1980) or nucleus (Doye and Hurt, 1995) are either lethal or have been shown to affect the growth rate on glucose media. A complete block in mitochondrial protein import is lethal, whereas mutation of import-stimulating factors has been shown to affect growth on non-fermentable carbon sources (Baker and Schatz, 1991). Thus, based on the growth characteristics of Δdjp1 cells, it is not likely that Djp1p is required for import of proteins into nuclei, ER, or mitochondria.

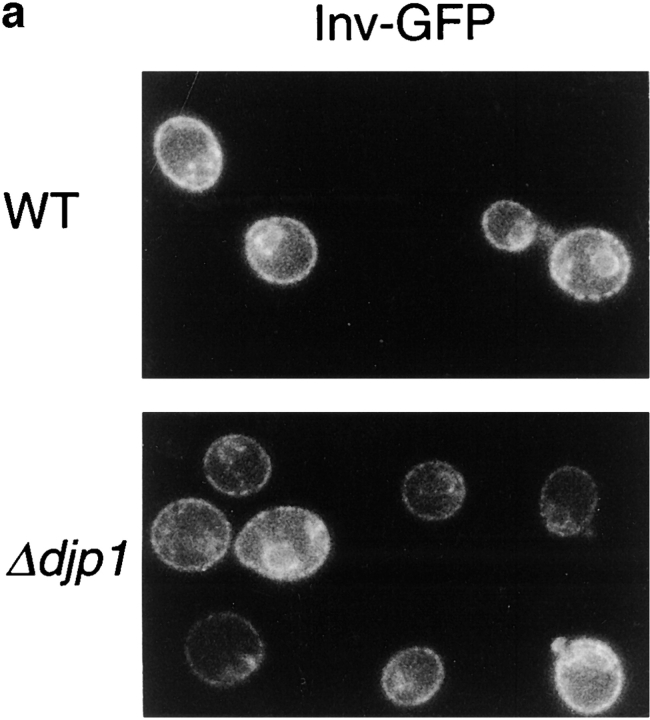

Our fractionation data shown in Fig. 5 a for the resident ER protein Kar2p and mitochondrial F1-ATPase confirm the specificity of Djp1p function for peroxisomes. To further exclude a relation between Djp1p and the ER, we expressed GFP fusion proteins containing an ER retention signal at the COOH terminus and either the presequence of invertase (Suc2p) or that of preproα-factor at the NH2 terminus (see Materials and Methods). Expression of the fusion proteins in wild-type cells resulted in a fluorescent pattern similar to that observed for Kar2p by indirect immunofluorescence microscopy (not shown). After growth on oleate for 24 h (Fig. 8 a) or 40 h (not shown), the GFP fusion proteins displayed the same distribution in Δdjp1 cells as in wild-type cells. This experiment indicated that ER morphology was normal and that import into the ER was not disturbed to such an extent that the steady state distribution of the GFP fusion proteins was affected in Δdjp1 cells.

Figure 8.

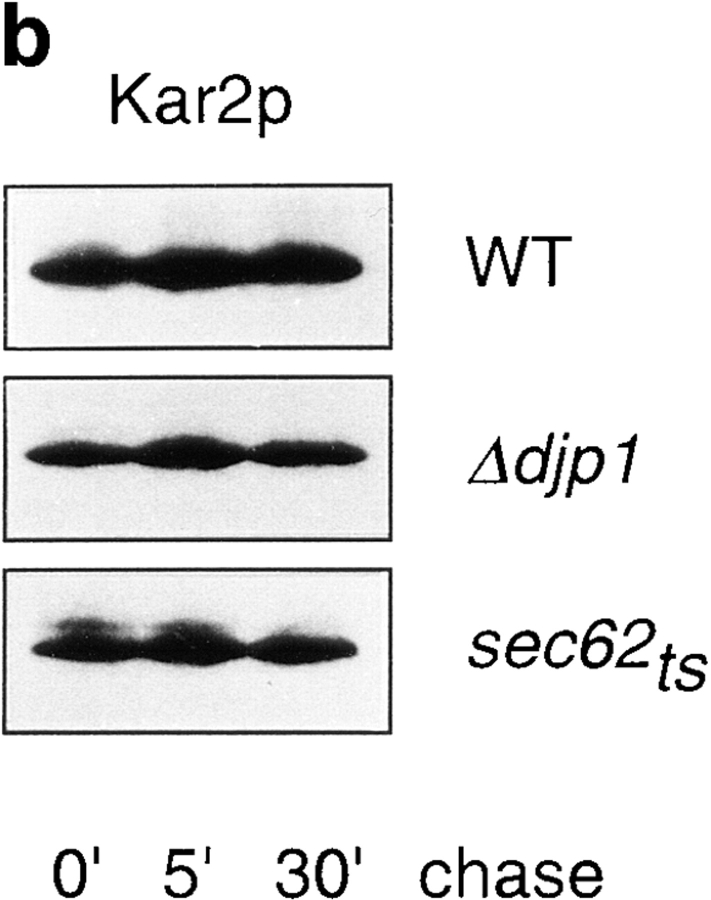

Import of proteins into the ER in Δdjp1 cells. (a) Expression of GFP-HDEL fused to the invertase presequence in wild-type (WT) and Δdjp1 cells grown on oleate medium for 24 h. (b) Pulse-chase experiment studying the processing of pre-Kar2p in wild-type, Δdjp1, and sec62ts cells. Cells were preincubated for 30 min at 37°C, the restrictive temperature, and subsequently pulse-labeled for 5 min with [35S]methionine and [35S]cysteine at 28°C. The pulse was followed by a chase in excess unlabeled methionine for 0, 5, or 30 min at 28°C, before reactions were stopped on ice. Cells were lysed and Kar2p was immunoprecipitated and analyzed by SDS-PAGE and fluorography.

If proteins are long-lived, a decrease in import rate is not necessarily reflected by a change in their steady state distribution. To address this, we studied the import rate of Kar2p in Δdjp1 cells by monitoring the processing of the precursor to the mature form (Fig. 8 b). Therefore, wild-type and Δdjp1cells were incubated with [35S]methionine and [35S]cysteine for 5 min (pulse), and the label was chased with cold methionine and cysteine during 5 and 30 min. We did not detect any accumulation of preKar2p in wild-type or Δdjp1 cells after 5 min of pulse-labeling, indicating rapid import and processing. As a control we used sec62ts cells, which clearly accumulated preKar2p. We concluded that preKar2p was rapidly imported into Δdjp1 cells. We again showed that Djp1p was not involved in the import of proteins into the ER.

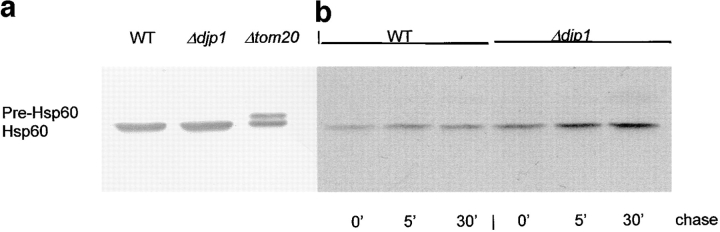

To further exclude a role for Djp1p in protein import into mitochondria we analyzed the import of mitochondrial Hsp60 by following its processing from the precursor form. As a control, we used Δtom20 cells, which accumulate some mitochondrial precursor proteins in the cytosol, including Hsp60 (Ramage et al., 1993; Moczko et al., 1994). Western blot analysis of total lysates showed that in contrast to Δtom20 cells (Fig. 9, lane 3), Δdjp1 cells (Fig. 9, lane 2) did not accumulate precursor Hsp60, implying that protein import into mitochondria was not affected to such an extent that it led to accumulation of precursor Hsp60 in the cytosol. If import of Hsp60 was only slightly retarded, or if mitochondrial Hsp60 is long-lived, accumulation of the precursor may have escaped detection. Therefore, we performed a pulse-chase experiment as described above for Kar2p. All of the labeled Hsp60 was already processed into the mature form at the end of the pulse (Fig. 9, lanes 4 and 7); precursor was not detectable at any time. The results were identical for wild-type and Δdjp1cells, indicating rapid import and processing of mitochondrial proteins in the absence of Djp1p.

Figure 9.

Import of Hsp60 into mitochondria in Δdjp1 cells. (a) Western blot analysis of Hsp60 in lysates from wild-type, Δdjp1, and Δtom20 cells grown overnight on glucose-containing medium at 28°C. (b) Pulse-chase experiment as in Fig. 8 to study the processing of pre-Hsp60 in wild-type and Δdjp1 cells. Cells were pulse-labeled for 5 min with [35S]methionine and [35S]cysteine and chased for 0, 5, or 30 min at 28°C, before reactions were stopped by the addition of azide and transfer to 0°C. Cells were lysed and Hsp60 was immunoprecipitated and analyzed by SDS-PAGE and fluorography.

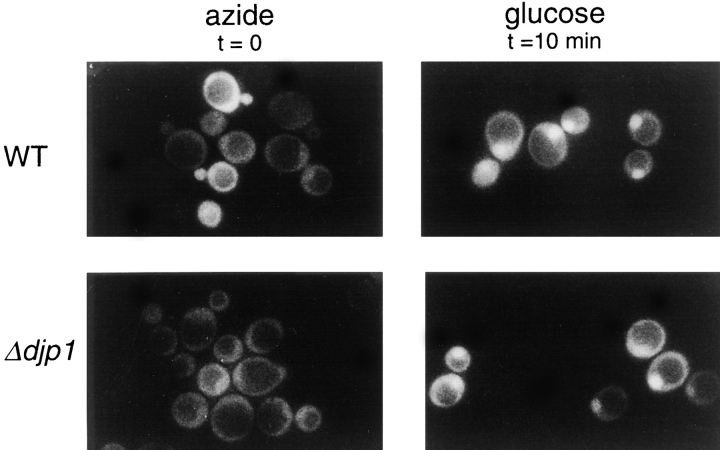

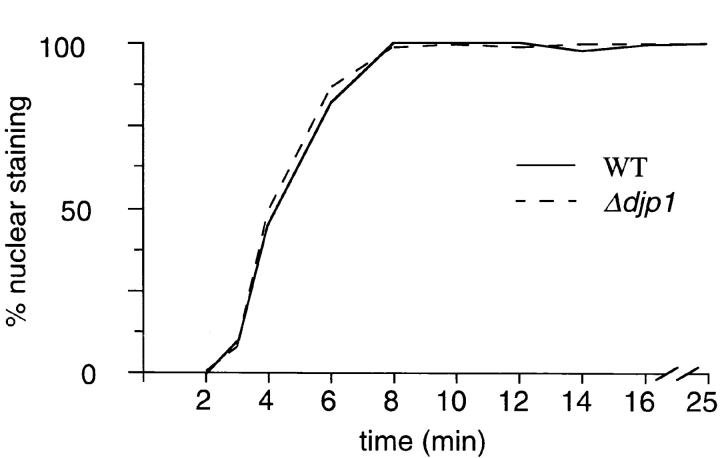

Import into neither the ER nor mitochondria was affected in Δdjp1 cells. A common feature of proteins targeted to the ER and mitochondria is the NH2-terminal location of the organellar targeting sequence (signal sequence). Furthermore, signal-sequence–containing proteins are kept in a (partially) unfolded conformation during the translocation process. Since most peroxisomal matrix proteins contain a COOH-terminal targeting signal sequence, and since for at least two of our reporter proteins (Mdh3p and thiolase) it had been shown that they oligomerize before they are imported into the organelle, we also tested whether import into the nucleus of (folded) GFP fused to a nuclear localization signal was affected in Δdjp1 cells. In wild-type and Δdjp1 cells NLS-GFP accumulated in the nucleus (Fig. 10). No morphological abnormalities of the nucleus were observed. To study nuclear protein import kinetics, we made use of a recently published method (Shulga et al., 1996) which is based on the reversible import of NLS-GFP. Cells were depleted of ATP by incubating them with azide. This resulted in disappearance of the bright nuclear fluorescence and equilibration of NLS-GFP between cytosol and nucleus (Fig. 10). The vacuole remained unlabeled and appeared as a dark hole surrounded by a diffuse fluorescence. Upon restoration of import conditions (washing azide-treated cells and addition of glucose-containing medium), NLS-GFP concentrated into a small bright spot in each cell, reminiscent of the nucleus. Relative import rates were quantified by counting the percentage of cells that showed NLS-GFP nuclear accumulation as a function of time. Δdjp1 cells imported NLS-GFP with the same kinetics as wild-type cells. This experiment illustrated that Djp1p was not required for import of proteins into the nucleus.

Figure 10.

Nuclear import kinetics of NLS-GFP in wild-type and Δdjp1 cells. Cells in the exponential growth phase expressing NLS-GFP were treated with azide. This resulted in equilibration of NLS-GFP between cytoplasm and nucleus. The vacuole remained unlabeled and was visible as a dark hole in the cell. After azide treatment, cells were resuspended in glucose-containing medium and recovery of nuclear staining (small bright spot) was scored by fluorescence microscopy. The same recovery kinetics were observed for wild-type and Δdjp1 cells.

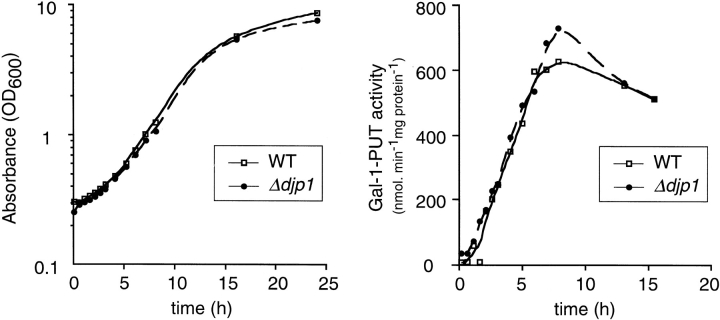

Finally, we studied the rate at which Δdjp1 cells can adapt their metabolism to environmental changes, which depends on the synthesis and maturation of a number of (cytosolic) proteins. For this purpose exponentially growing cells were shifted from glucose medium to galactose medium and growth was measured. Δdjp1 cells grew at the same exponential rate as wild-type cells (Fig. 11), implying that under these conditions Djp1p was not required. Furthermore, Δdjp1 cells rapidly adapted to growth on galactose medium as the lag phase was similar to that of wild-type cells. To follow maturation of one protein in more detail, the induction of one of the enzymes specifically required for growth on galactose (galactose-1-phosphate uridylyltransferase [Gal-1-PUT]) was measured. In Δdjp1 cells this enzyme was induced with the same kinetics as in wild-type cells (Fig. 11). Metabolic adaptation requires the function of many processes, including signal transduction, de novo protein synthesis, folding, and protein sorting. We concluded from our results that Djp1p was specifically required for peroxisomal protein import and was not needed for maturation or import of proteins in any other organelle. Djp1p was therefore dispensible for cell growth under all culture conditions except oleate.

Figure 11.

Galactose induction kinetics in wild-type and Δdjp1 cells. (a) Growth curve of cells in galactose-containing medium and (b) induction curve of the galactose-inducible enzyme galactose-1-phosphate uridylyltransferase (Gal-1-PUT).

Discussion

Transport of proteins across intracellular membranes requires molecular chaperones of the Hsp70 family. Hsp70 activity is regulated by J-domain–containing proteins that recruit Hsp70 to their site of action. The J-domain recruits a specific Hsp70 family member whereas other parts of the J-domain–containing protein are thought to interact with the Hsp70 substrate (Rassow et al., 1995). Cytosolic Hsp70s and J-domain–containing proteins are involved in posttranslational translocation of proteins across the ER and mitochondrial membranes, presumably by keeping precursor proteins in a partially unfolded translocation-competent conformation (for review see Brodsky and Schekman, 1994; Mihara and Omura, 1996; Rassow et al., 1997). Luminal organellar Hsp70s are required for both the translocation process and the folding and assembly of proteins (Hartl, 1996).

Whereas ER and mitochondrial proteins do not acquire their native states until translocation is complete, nuclear and peroxisomal proteins can fold and oligomerize before import. Targeting and translocation of nuclear proteins requires Hsp70. In a semi-intact cell system, import into peroxisomes of microinjected human serum albumin coated with multiple PTS1-containing peptides was shown to require cytosolic Hsp73 (Walton et al., 1994). A prenylated DnaJ homologue has been found on the cytoplasmic side of cucumber glyoxysomes, although the significance of this association remains to be established (Preisig-Mueller et al., 1994). The specific defect of cells lacking the J-domain– containing protein Djp1p provides the first genetic evidence that molecular chaperones are required for efficient peroxisomal protein import in vivo.

Djp1p behaved as a mostly cytosolic protein. It is easy to envisage why J-domain–containing proteins located inside an organelle are involved in the import of proteins specifically into that organelle. It is surprising though that a largely cytosolic protein such as Djp1p is specific for peroxisomal protein import, and is not required for import of proteins into any other organelle. Still, our data clearly indicate that Djp1p functions in an organelle-specific manner. In Δdjp1 cells peroxisomal structures are small and of intermediate buoyant density, resembling the early stages of peroxisome proliferation in S. cerevisiae (Erdmann and Blobel, 1995; our own unpublished observations). This slight organelle maturation defect accompanied the partial mislocalization of peroxisomal matrix proteins to the cytosol, which suggested that the primary defect in Δdjp1 cells is in the import of peroxisomal proteins. Kinetic studies, performed under various growth conditions, revealed a lower import rate of all tested peroxisomal matrix proteins in Δdjp1 cells (Ruigrok, C., manuscript in preparation).

When considering the function of Djp1p and its cognate Hsp70 partner in the import of peroxisomal proteins, several roles come to mind, each analogous to the role of another chaperone. Newly synthesized proteins are guided from ribosomes to their specific subcellular location through a series of interactions with cellular proteins. One of the first is the association with soluble targeting factors. Recognition of mitochondrial and ER presequences occurs at the ribosome (for review see Bukau et al., 1996). On the other hand, most peroxisomal matrix proteins contain a PTS1, which is found at the extreme COOH terminus. Since addition of the PTS1 to GFP was sufficient to direct it to peroxisomes, specific recognition of the targeting signal in GFP-PTS1 could occur only after translation termination. Because GFP-PTS1 was partially mislocalized in Δdjp1 cells, Djp1p must function mainly after completion of translation.

Our experiments indicated that Djp1p has a stimulatory effect on peroxisomal protein import. Its effect is essential, however, for peroxisome biogenesis; it ensures sufficient import to maintain the function of peroxisomes. It is unlikely that Djp1p plays a role in the posttranslational folding and assembly of peroxisomal proteins since mislocalized peroxisomal enzymes are active in the cytosol of Δdjp1 cells. In addition, there is no requirement of a native protein conformation for import into peroxisomes (Walton et al., 1992, 1995), and human alanine:glyoxylate aminotransferase 1 (AGT) can be imported either as a monomer or as a dimer (Leiper et al., 1996).

Djp1p and its putative Hsp70 partner could keep peroxisomal proteins in a translocation-competent conformation. Whereas the subunits in oligomeric proteins have been shown to stay together during peroxisomal import (Glover et al., 1994; McNew and Goodman 1994; Elgersma et al., 1996b ; Leiper et al., 1996), the actual conformation during translocation is unknown. Djp1p may be needed to keep the newly synthesized proteins in a flexible, extended conformation, which nonetheless allows oligomeric contacts. Analogously, the cytosolic Hsp70 chaperone Ssa has been proposed to stimulate posttranslational import of certain newly synthesized ER and mitochondrial preproteins by keeping the precursors in an incompletely folded import-competent conformation (for review see Brodsky and Schekman, 1994; Corsi and Schekman, 1996; Mihara and Omura, 1996). Ssa collaborates in this process with the J-domain–containing protein Ydj1p (Becker et al., 1996). The exact function of Ydj1p has not been described.

As a putative cofactor to a molecular chaperone, Djp1p does not need to be involved in a folding process. DnaJ-like proteins have been reported to assist in modulating protein–protein interactions of already folded proteins as well. It is possible that Djp1p stimulates recognition of peroxisomal proteins by the PTS receptors, thereby increasing targeting fidelity. Djp1p may act on newly synthesized peroxisomal matrix proteins as well as on PTS receptors, modifying their conformation by associating with either protein or both. If Djp1p presents GFP-PTS1 to its receptor (Pex5p), the only way Djp1p could recognize GFP-PTS1 is via its PTS1. Experimental data to support a direct or indirect interaction between the PTS1 and Djp1p do not exist. A precedent for Hsp70-mediated presentation of targeting signals to their cognate receptors, however, has been found in nuclear protein import (Melchior and Gerace, 1995).

Another step in the maturation of peroxisomal proteins is their targeting to and entry into the organelle. In this step, Djp1p and its cognate Hsp70 may regulate the activity of the PTS receptors in a manner similar to the way Hsp70 and Hsp40 regulate, in concert with additional chaperones, the activity of hormone receptors (Bohen et al., 1995). If Djp1p indeed is involved in the regulation of PTS receptor docking onto the peroxisome, its absence would cause permanent shielding or permanent exposure of docking interaction domains in the receptors, the former resulting in a lack of interaction of PTS receptors with the peroxisome, the latter leading to futile docking and release cycles of empty receptor molecules. Both phenotypes correspond well with that of the Δdjp1 cells, in which peroxisomal protein import is impaired. The same phenotype would arise if a Djp1p/Hsp70 complex plays a role in conformational changes required to convert released empty PTS receptor into a form that can bind PTS-containing proteins again. Hsp70 / Hsp40 have indeed been shown to be involved in increasing the availability of ligand-responsive aporeceptor (Frydman and Höhfeld, 1997).

After docking of PTS receptor charged with a cargo PTS protein, a complex series of events is likely to occur during the translocation process. At least three peroxisomal membrane proteins (Pex13p, Pex14p, and Pex17p [formerly Pas9p]) bind the PTS1 receptor, possibly in a cascade of sequential interactions with peroxins at the peroxisomal membrane (Elgersma and Tabak, 1996; Albertini et al., 1997). It is conceivable that Djp1p/Hsp70 functions as a modulator for the various protein–protein interactions, stimulating successive binding and release.

Since Djp1p is required for import of both PTS1- and PTS2-containing proteins, Djp1p most likely acts either at the point of or after convergence of the two pathways. Since the only PTS-specific import factors identified thus far are the PTS receptors, the two pathways might merge soon after recognition of the PTS-containing proteins by their cognate receptors. In S. cerevisiae, the PTS1 receptor and PTS2 receptor interact in vivo, thereby forming a receptor complex that may be responsible for the recognition or targeting of both PTS1- and PTS2-containing proteins simultaneously (Rehling et al., 1996; Albertini et al., 1997; Huhse et al., 1998). Djp1p may stimulate the formation of this complex. Lack of one of the receptors, however, does not abolish the function of the other receptor, indicating that formation of this putative cytoplasmic targeting complex is not a prerequisite for targeting. Since kinetic studies on import of PTS2-containing proteins in PTS1 receptor–deficient yeast cells or vice versa have never been done, we cannot exclude that both receptors are necessary for a high efficiency of peroxisomal matrix protein import. Indeed, PTS2 import in mammalian cells is dependent on the presence of the PTS1 receptor (Dodt et al., 1995; Wiemer et al., 1995; Baes et al., 1997; Otera et al., 1998). Alternatively, Djp1p may modulate the various protein–protein interactions required during the targeting cycle of this dual receptor complex in a way similar to that discussed for the single PTS receptors.

Kinetic studies in mammalian and yeast cells have revealed that some peroxisomal proteins initially associate with low density organellar structures (“pre-peroxisomes”) before reaching the mature peroxisomes of high density (Heinemann and Just, 1992; Luers et al., 1993; Titerenko and Rachubinski, 1998). Intriguingly, we observed that Djp1p is involved in peroxisomal protein import and is associated with low density membrane structures distinct from peroxisomes. Together these results indicate that Djp1p may play a role in the import process of proteins into precursor peroxisomes.

To summarize, we have found the first peroxisome-specific cofactor to a chaperone: Djp1p. Our genetic and biochemical evidence clearly shows that Djp1p is involved in the import of peroxisomal proteins only, and not in processes related to other organelles. Surprisingly, despite its specificity for peroxisomes, Djp1p is located mainly in the cytosol with a minor fraction associated with membranes, which opens up a wealth of possible roles that the protein may play. For every possible scenario outlined above, a precedent exists in the form of a known Hsp70 chaperone complex. Our results are clear but do not yet allow us to distinguish between these different possible functions of Djp1p. A search for the partner protein(s) of Djp1p is in progress, and with the Δdjp1 mutant available, we have started to investigate the precise role of molecular chaperones in the peroxisomal protein import process.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Drs. J. Goodman and M. Meijer for the Pex11p and F1β-ATPase antibodies, respectively; Dr. A. Hartig for the reagents to produce CTA antiserum; and Dr. S. Gould for GFP-PTS constructs. We thank Dr. S. Rospert for the Δtom20 mutant and anti-Hsp60 antiserum. We thank Dr. R. Schekman for the Sec62ts mutant and Dr. M. Rose for reagents to produce Kar2p antiserum. We thank Dr. A. Kal and T. Voorn-Brouwer for production of antisera against Kar2p and thiolase, and Dr. Y. Elgersma for isolation of the pas22-1 mutant. We thank C. van Roermund for assistance with the Nycodenz density gradients; C. Dekker, C. van Roermund, and Dr. R. Wanders for the Gal-1-PUT measurements; and W. de Jonge for technical assistance with the mitochondrial pulse-chase experiment. We thank Dr. A. Motley for critically reading the manuscript.

This work was supported by a grant from the Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research (NWO) to H.F. Tabak and from the Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences to I. Braakman.

Abbreviations used in this paper

- CTA

catalase A

- Djp1p

DnaJ-like protein required for peroxisomal protein import

- Gal-1-PUT

galactose-1-phosphate uridylyltransferase

- GFP

green fluorescent protein

- Hsp

heat-shock protein

- Mdh

malate dehydrogenase

- NH2-tag

NH2-terminal hemagglutinin epitope tag

- NLS

nuclear localization signal

- ORF

open reading frame

- pex

peroxin

- PGI

phosphoglucose isomerase

- PTS

peroxisome targeting signal

Footnotes

E.H. Hettema and C.C.M. Ruigrok contributed equally to this paper.

Address all correspondence to I. Braakman, Department of Biochemistry, Academic Medical Center, 1105 AZ Amsterdam, The Netherlands. Tel.: +31-20-566-3297. Fax +31-20-691-5519. E-mail: i.braakman@amc.uva.nl

References

- Albertini M, Rehling P, Erdmann R, Girzalsky W, Kiel JAKW, Veenhuis M, Kunau W-H. Pex14p, a peroxisomal membrane protein binding both receptors of the PTS-dependent import pathways. Cell. 1997;89:83–92. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80185-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Attencio DP, Yaffe MP. MAS5, a yeast homolog of DnaJ involved in mitochondrial protein import. Mol Cell Biol. 1992;12:283–291. doi: 10.1128/mcb.12.1.283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baes M, Gressens P, Baumgart E, Carmeliet P, Casteels M, Fransen M, Evrard P, Fahimi D, Declercq PE, Collen D, Van Veldhoven PP, Mannaerts GP. A mouse model for Zellweger syndrome. Nat Genet. 1997;17:49–57. doi: 10.1038/ng0997-49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker K, Schatz G. Mitochondrial proteins essential for viability mediate protein import into yeast mitochondria. Nature. 1991;349:205–208. doi: 10.1038/349205a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker J, Walter W, Yan W, Craig EA. Functional interaction of cytosolic hsp70 and a DnaJ-related protein, Ydj1p, in protein translocation in vivo. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:4378–4386. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.8.4378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bohen SP, Kralli A, Yamamoto KR. Hold'em and Fold'em: chaperones and signal transduction. Science. 1995;268:1303–1304. doi: 10.1126/science.7761850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brodsky, J.L., and R. Shekman. 1994. Heat shock cognate proteins and polypeptide translocation across the endoplasmic reticulum membrane. R.I. Morimoto, A. Tissieres, and C. Georgopoulos, editors. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, Cold Spring Harbor, NY. 85–109.

- Bukau B, Hesterkamp T, Luirink J. Growing up in a dangerous environment: a network of multiple targeting and folding pathways for nascent polypeptides in the cytosol. Trends Cell Biol. 1996;6:480–486. doi: 10.1016/0962-8924(96)84946-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caplan AJ, Douglas MG. Characterization of YDJ1: Ayeast homologue of the bacterial dnaJ protein. J Cell Biol. 1991;114:609–621. doi: 10.1083/jcb.114.4.609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corsi AK, Schekman R. Mechanism of polypeptide translocation into the endoplasmic reticulum. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:30299–30302. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.48.30299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craig, E.A., B.K. Baxter, J. Becker, J. Halladay, and T. Ziegelhoffer. 1994. Cytosolic hsp70s of Saccharomyces cerevisiae: Roles in Protein Synthesis, Protein Translocation, Proteolysis and Regulation. R.I. Morimoto, A. Tissieres, and C. Georgopoulos, editors. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, Cold Spring Harbor, NY. 31–52.

- Distel B, Van Der Leij I, Veenhuis M, Tabak HF. Alcohol oxidase expressed under non-methylotrophic conditions is imported, assembled and enzymatically active in peroxisomes of Hansenula polymorpha. . J Cell Biol. 1988;107:1669–1675. doi: 10.1083/jcb.107.5.1669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dodt G, Gould SJ. Multiple PEX genes are required for proper subcellular distribution and stability of Pex5p, the PTS1 receptor: Evidence that PTS1 protein import is mediated by a cycling receptor. J Cell Biol. 1996;135:1763–1774. doi: 10.1083/jcb.135.6.1763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dodt G, Braverman N, Wong C, Moser A, Moser HW, Watkins P, Valle D, Gould SJ. Mutations in the PTS1 receptor gene, PXR1, define complementation group 2 of the peroxisome biogenesis disorders. Nat Genet. 1995;9:115–125. doi: 10.1038/ng0295-115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doye V, Hurt EC. Genetic approaches to nuclear pore structure and function. Trends Genet. 1995;11:235–241. doi: 10.1016/s0168-9525(00)89057-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dyer JM, McNew JA, Goodman JM. The sorting sequence of the peroxisomal integral membrane protein PMP47 is contained within a short hydrophilic loop. J Cell Biol. 1996;133:269–280. doi: 10.1083/jcb.133.2.269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elgersma Y, Tabak HF. Proteins involved in peroxisome biogenesis and functioning. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1996;1286:269–283. doi: 10.1016/s0304-4157(96)00012-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elgersma Y, Van den Berg M, Tabak HF, Distel B. An efficient positive selection procedure for the isolation of peroxisomal import and peroxisomal assembly mutants of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. . Genetics. 1993;135:731–740. doi: 10.1093/genetics/135.3.731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elgersma Y, Van Roermund CWT, Wanders RJA, Tabak HF. Peroxisomal and mitochondrial carnitine acetyltransferases of Saccharomyces cerevisiaeare encoded by a single gene. EMBO (Eur Mol Biol Organ) J. 1995;14:3472–3479. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb07353.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elgersma Y, Kwast L, Klein A, Voorn-Brouwer T, van den Berg M, Metzig B, America T, Tabak HF, Distel B. The SH3 domain of the Saccharomyces cerevisiaeperoxisomal membrane protein Pex13p functions as a docking site for Pex5p, a mobile receptor for the import of PTS1-containing proteins. J Cell Biol. 1996a;135:97–109. doi: 10.1083/jcb.135.1.97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elgersma Y, Vos A, van den Berg M, van Roermund CWT, van der Sluijs P, Distel B, Tabak HF. Analysis of the carboxy-terminal peroxisomal targetting signal 1 in a homologous context in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. . J Biol Chem. 1996b;271:26375–26382. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.42.26375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elgersma Y, Kwast L, van den Berg M, Snyder WB, Distel B, Subramani S, Tabak HF. Overexpression of Pex15p, a phosphorylated peroxisomal integral membrane protein required for peroxisome assembly in S. cerevisiae, causes proliferation of the endoplasmic reticulum membrane. EMBO (Eur Mol Biol Organ) J. 1997;24:7326–7341. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.24.7326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elgersma Y, Elgersma-Hooisma M, Wenzel T, McCaffery JM, Farquhar MG, Subramani S. A mobile PTS2 receptor for peroxisomal protein import in Pichia pastoris. . J Cell Biol. 1998;140:807–820. doi: 10.1083/jcb.140.4.807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erdmann R, Blobel G. Giant peroxisomes in oleic acid-induced Saccharomyces cerevisiaelacking the peroxisomal membrane protein Pmp27p. J Cell Biol. 1995;128:509–523. doi: 10.1083/jcb.128.4.509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frydman J, Höhfeld J. Chaperones get in touch: the Hip-Hop connection. Trends Biochem Sci. 1997;22:87–92. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(97)01005-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gietz RD, Sugino A. New yeast Escherichia coli shuttle vectors constructed with in vitro mutagenized yeast genes lacking six-base pair restriction sites. Gene. 1988;74:527–534. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(88)90185-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glover JR, Andrews DW, Rachubinski RA. Saccharomyces cerevisiaeperoxisomal thiolase is imported as a dimer. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:10541–10545. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.22.10541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gould SJ, Kalish JE, Morrell JC, Bjorkman J, Urquhart AJ, Crane DI. An SH3 protein in the peroxisome membrane is a docking factor for the PTS1 receptor. J Cell Biol. 1996;135:85–95. doi: 10.1083/jcb.135.1.85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gould SJ, Keller G-A, Subramani S. Identification of peroxisomal targeting signals located at the carboxy terminus of four peroxisomal proteins. J Cell Biol. 1988;107:897–905. doi: 10.1083/jcb.107.3.897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gouzy J, Corpet F, Kahn D. Graphical interface for the ProDom domain families. Trends Biochem Sci. 1996;21:493. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(96)30040-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harmsen MM, Langedijk AC, Van Tuinen E, Geerse RH, Raue HA, Maat J. Effect of a pmr1 disruption and different signal sequences on the intracellular processing and secretion of Cyamopsis tetragonoloba α-galactosidase by Saccharomyces cerevisiae. . Gene. 1993;125:115–123. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(93)90318-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartl FU. Molecular chaperones in cellular protein folding. Nature. 1996;381:571–580. doi: 10.1038/381571a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes SA, Dice JF. Roles of molecular chaperones in protein degradation. J Cell Biol. 1996;132:255–258. doi: 10.1083/jcb.132.3.255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinemann P, Just WW. Peroxisomal protein import: in vivoevidence for a novel translocation competent compartment. FEBS (Fed Eur Biochem Soc) Lett. 1992;300:179–182. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(92)80191-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hettema EH, Van Roermund CWT, Distel B, Van den Berg M, Vilela C, Rodrigues-Pousada C, Wanders RJA, Tabak HF. The ABC transporter proteins Pat1 and Pat2 are required for import of long-chain fatty acids into peroxisomes of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. . EMBO (Eur Mol Biol Organ) J. 1996;15:3813–3822. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Höhfeld J, Veenhuis M, Kunau WH. PAS3, a Saccharomyces cerevisiaegene encoding a peroxisomal integral membrane protein essential for peroxisome biogenesis. J Cell Biol. 1991;114:1167–1178. doi: 10.1083/jcb.114.6.1167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huhse B, Rehling P, Albertini M, Blank L, Meller K, Kunau W-H. Pex17p of Saccharomyces cerevisiaeis a novel peroxin and component of the peroxisomal protein pranslocation machinery. J Cell Biol. 1998;140:49–60. doi: 10.1083/jcb.140.1.49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones EW. Proteinase mutants of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. . Genetics. 1977;85:23–33. doi: 10.1093/genetics/85.1.23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalish JE, Theda C, Morrell JC, Berg JM, Gould SJ. Formation of the peroxisome lumen is abolished by loss of Pichia pastorisPas7p, a zinc-binding integral membrane protein of the peroxisome. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15:6406–6419. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.11.6406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalish JE, Keller G-A, Morrell JC, Mihalik SJ, Smith B, Cregg JM, Gould SJ. Characterization of a novel component of the peroxisomal import apparatus using fluorescent peroxisomal proteins. EMBO (Eur Mol Biol Organ) J. 1996;15:3275–3285. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kragler F, Langeder A, Raupachova J, Binder M, Hartig A. Two independent peroxisomal targeting signals in catalase A of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. . J Cell Biol. 1993;120:665–673. doi: 10.1083/jcb.120.3.665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazarow PB, Fujiki Y. Biogenesis of peroxisomes. Annu Rev Cell Biol. 1985;1:489–530. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cb.01.110185.002421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee DH, Sherman MY, Goldberg AL. Involvement of the molecular chaperone Ydj1 in the ubiquitin-dependent degradation of short-lived and abnormal proteins in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. . Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:4773–4781. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.9.4773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leighton J, Schatz G. An ABC transporter in the mitochondrial inner membrane is required for normal growth of yeast. EMBO (Eur Mol Biol Organ) J. 1995;14:188–195. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb06989.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leiper JM, Oatey PB, Danpure CJ. Inhibition of alanine: Glyoxylate aminotransferase I dimerization is a prerequisite for its peroxisome-to-mitochondrion mistargetting in primary hyperoxaluria type I. J Cell Biol. 1996;135:939–951. doi: 10.1083/jcb.135.4.939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lüers G, Hashimoto T, Fahimi HD, Völkl A. Biogenesis of peroxisomes: isolation and characterization of two distinct peroxisomal populations from normal and regenerating rat liver. J Cell Biol. 1993;121:1271–1280. doi: 10.1083/jcb.121.6.1271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCammon MT, McNew JA, Willy PJ, Goodman JM. An internal region of the peroxisomal membrane protein PMP47 is essential for sorting to peroxisomes. J Cell Biol. 1994;124:915–925. doi: 10.1083/jcb.124.6.915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNew JA, Goodman JM. An oligomeric protein is imported into peroxisomes in vivo. J Cell Biol. 1994;127:1245–1257. doi: 10.1083/jcb.127.5.1245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melchior F, Gerace L. Mechanisms of nuclear protein import. Curr Biol. 1995;7:310–318. doi: 10.1016/0955-0674(95)80084-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mihara K, Omura T. Cytoplasmic chaperones in precursor targetting to mitochondria: the role of MSF and hsp70. Trends Cell Biol. 1996;6:104–108. doi: 10.1016/0962-8924(96)81000-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moczko M, Ehmann B, Gärtner F, Hönlinger A, Schäfer E, Pfanner N. Deletion of the receptor MOM19 strongly impairs import of cleavable preproteins into Saccharomyces cerevisiaemitochondria. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:9045–9051. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukui H, Shuntoh H, Chang C-D, Asami M, Ueno M, Suzuki K, Kuno T. Isolation and characterization of CAJ1, a novel yeast homolog of dnaJ. Gene. 1994;145:125–127. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(94)90334-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munujos P, Coll-Canti J, Gonzalez-Sastre F, Gella FJ. Assay of succinate dehydrogenase activity by a colorimetric-continuous method using iodonitrotetrazolium chloride as electron acceptor. Anal Biochem. 1993;212:506–509. doi: 10.1006/abio.1993.1360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novick P, Field C, Schekman R. Identification of 2 complementation groups required for post-translational events in the yeast secretory pathway. Cell. 1980;21:205–215. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(80)90128-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osumi T, Tsukamoto T, Hata S, Yokota S, Miura S, Fujiki Y, Hijikata M, Miyazawa S, Hashimoto T. Amino-terminal presequence of the precursor of peroxisomal 3-ketoacyl-CoA thiolase is a cleavable signal peptide for peroxisomal targeting. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1991;181:947–954. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(91)92028-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otera H, Okumoto K, Tateishi K, Ikoma Y, Matsuda E, Nishimura M, Tsukamoto T, Osumi T, Ohashi K, Higuchi O, Fujiki Y. Peroxisome targeting signal type 1 (PTS1) receptor is involved in import of both PTS1 and PTS2: studies with PEX5-defective CHO cell mutants. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:388–399. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.1.388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pesce MA, Bodourian SH, Harris RC, Nicholson JF. Enzymatic micromethod for measuring galactose-1-phosphate uridylyltransferase activity in human erythrocytes. Clin Chem. 1977;23:1711–1717. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preisig-Mueller R, Munster G, Kindl H. Heat shock enhances the amount of prenylated Dnaj protein at membranes of glyoxysomes. Eur J Biochem. 1994;219:57–63. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1994.tb19914.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Purdue PE, Lazarow PB. Peroxisomal biogenesis: multiple pathways of protein import. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:30065–30068. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramage L, Junne T, Hahne K, Lithgow T, Schatz G. Functional cooperation of mitochondrial protein import receptors in yeast. EMBO (Eur Mol Biol Organ) J. 1993;12:4115–4123. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb06095.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rassow J, Voos W, Pfanner N. Partner proteins determine multiple functions of Hsp70. Trends Cell Biol. 1995;5:207–212. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8924(00)89001-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rassow J, von Ahsen O, Boemer U, Pfanner N. Molecular chaperones: towards a characterization of the heat-shock protein 70 family. Trends Cell Biol. 1997;7:129–133. doi: 10.1016/S0962-8924(96)10056-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rehling P, Marzioch M, Niesen F, Wittke E, Veenhuis M, Kunau W-H. The import receptor for the peroxisomal targeting signal2 (PTS2) in Saccharomyces cerevisiaeis encoded by the PAS7 gene. EMBO (Eur Mol Biol Organ) J. 1996;15:2901–2913. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sambrook, J., E.F. Fritsch, and T. Maniatis. 1989. Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual, Second Ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratories, Cold Spring Harbor, NY. 545 pp.

- Schlenstedt G, Harris S, Risse B, Lill R, Silver PA. A yeast DnaJ homologue, Scj1p, can function in the endoplasmic reticulum with BiP/ Kar2p via a conserved domain that specifies interactions with Hsp70s. J Cell Biol. 1995;129:979–988. doi: 10.1083/jcb.129.4.979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shulga N, Roberts P, Gu Z, Spitz L, Tabb MM, Nomura M, Goldfarb DS. In vivo nuclear transport kinetics in Saccharomyces cerevisiae: A role for Heat shock protein 70 during targetting and translocation. J Cell Biol. 1996;135:329–339. doi: 10.1083/jcb.135.2.329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Small GM, Szabo LJ, Lazarow PB. Acyl-CoA oxidase contains two targetting sequences each of which can mediate protein import into peroxisomes. EMBO (Eur Mol Biol Organ) J. 1988;7:1167–1173. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1988.tb02927.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith PK, Krohn RI, Hermanson GT, Mallia AK, Gartner FH, Provenzano MD, Fujimoto EK, Goeke NM, Olson BJ, Klenk DC. Measurement of protein using bicinchonic acid. Anal Biochem. 1985;150:76–85. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(85)90442-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sonnhammer ELL, Kahn D. Domainer algorithm. Protein Sci. 1994;3:482–492. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560030314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swinkels BW, Gould SJ, Bodnar AG, Rachubinski RA, Subramani S. A novel, cleavable peroxisomal targeting signal at the amino-terminus of the rat 3-ketoacyl-CoA thiolase. EMBO (Eur Mol Biol Organ) J. 1991;10:3255–3262. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1991.tb04889.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Titorenko VI, Rachubinski RA. Mutants of the Yeast Yarrowia lipolyticadefective in protein exit from the endoplasmic reticulum are also defective in peroxisome biogenesis. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:2789–2803. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.5.2789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van der Leij I, Van der Berg M, Boot R, Franse MM, Distel B, Tabak HF. Isolation of peroxisome assembly mutants from Saccharomyces cerevisiaewith different morphologies using a novel positive selection procedure. J Cell Biol. 1992;119:153–162. doi: 10.1083/jcb.119.1.153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Roermund CWT, van den Berg M, Wanders RJA. Localisation of peroxisomal 3-oxoacyl-CoA thiolase in particles of varied density in rat liver: implications for peroxisome biogenesis. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1995;1245:348–358. doi: 10.1016/0304-4165(95)00099-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]