Abstract

The molecular mechanisms underlying the organization of ion channels and signaling molecules at the synaptic junction are largely unknown. Recently, members of the PSD-95/SAP90 family of synaptic MAGUK (membrane-associated guanylate kinase) proteins have been shown to interact, via their NH2-terminal PDZ domains, with certain ion channels (NMDA receptors and K+ channels), thereby promoting the clustering of these proteins. Although the function of the NH2-terminal PDZ domains is relatively well characterized, the function of the Src homology 3 (SH3) domain and the guanylate kinase-like (GK) domain in the COOH-terminal half of PSD-95 has remained obscure. We now report the isolation of a novel synaptic protein, termed GKAP for guanylate kinase-associated protein, that binds directly to the GK domain of the four known members of the mammalian PSD-95 family. GKAP shows a unique domain structure and appears to be a major constituent of the postsynaptic density. GKAP colocalizes and coimmunoprecipitates with PSD-95 in vivo, and coclusters with PSD-95 and K+ channels/ NMDA receptors in heterologous cells. Given their apparent lack of guanylate kinase enzymatic activity, the fact that the GK domain can act as a site for protein– protein interaction has implications for the function of diverse GK-containing proteins (such as p55, ZO-1, and LIN-2/CASK).

In neurons, the proper subcellular distribution of ion channels and receptors is important for electrical signaling. Ion channels are highly concentrated in neuronal membrane specializations such as synaptic junctions and nodes of Ranvier. The high local concentration of ion channels and receptors is thought to be achieved by the interaction of these membrane proteins with anchoring and clustering proteins at the target site (reviewed in Froehner, 1993; Hall and Sanes, 1993).

A family of synaptic ion channel clustering proteins (of which postsynaptic density-95 [PSD-951]/synapse-associated protein 90 [SAP90] is the prototypic member) has recently emerged. With four mammalian members so far identified, this family consists of: PSD-95/SAP90 (Cho et al., 1992; Kistner et al., 1993), SAP97/hdlg (Lue et al., 1994; Müller et al., 1995), chapsyn-110/PSD-93 (Brenman et al., 1996; Kim et al., 1996), and SAP102 (Müller et al., 1996). Since there is no collective name for these proteins, we will for convenience refer to them as either the “PSD95 family” or as “chapsyns” (for channel associated proteins of synapses).

In vitro and in heterologous cells, the PSD-95 family binds directly to, and can mediate the clustering of N-methyld-aspartate (NMDA) receptors and Shaker-type K+ channels (Kim et al., 1995; Kornau et al., 1995; Kim et al., 1996; Müller et al., 1996; Niethammer et al., 1996; reviewed in Sheng, 1996; Sheng and Kim, 1996). This clustering is dependent on a direct interaction between the COOH-terminal -E-T/S-X-V sequence motif of the ion channel subunits and specific PDZ domains in the NH2-terminal region of the chapsyns (Kim et al., 1995; Doyle et al., 1996; Kim et al., 1996; Kim and Sheng, 1996). Discs large (DLG), the Drosophila homologue of the mammalian PSD-95 family (Woods and Bryant, 1991), also binds to Shaker K+ channels (Tejedor et al., 1997). Significantly, in Drosophila dlg mutants, synaptic morphology is poorly developed and the normal synaptic clustering of Shaker protein is disrupted (Lahey et al., 1994; Tejedor et al., 1997). Thus, there is compelling in vitro and in vivo support for the notion that PSD-95 family proteins function as clustering molecules involved in the molecular organization of synaptic junctions.

Integral membrane proteins are not the only proteins that interact with chapsyns. PSD-95 and chapsyn-110/ PSD-93 also interact with the intracellular enzyme, neuronal nitric oxide synthase, apparently via a homotypic PDZ-PDZ domain interaction (Brenman et al., 1996). Direct binding between hdlg/SAP97 and the adenomatous polyposis coli (APC) tumor suppressor protein has also been reported (Matsumine et al., 1996). Thus, PSD-95 family proteins may function as molecular scaffolds for the clustering of receptors/ion channels and their associated downstream signaling molecules.

The identified protein–protein interactions so far all involve the modular PDZ domains found in the NH2-terminal region of the PSD-95 family members. PSD-95 and relatives, however, also contain an SH3 domain and GK domain in their COOH-terminal half, in common with the MAGUK superfamily that includes many members such as the erythrocyte membrane protein p55, and the tight junction protein zona occludens-1 (ZO-1) (reviewed in Anderson, 1996). In contrast to their PDZ domains, the function of the SH3 domain and the GK domain of chapsyns and other MAGUKs is unknown. The GK domain was named because it shares 37% amino acid sequence identity to yeast guanylate kinase, an enzyme that converts GMP to GDP via hydrolysis of ATP. However, the ATP-binding site is not conserved in the GK domain of the PSD-95 family, and these GK domains exhibit no enzymatic activity, though they do bind GMP in a relatively specific manner (Kistner et al., 1995).

In the absence of enzymatic activity, we hypothesized that the GK domain of chapsyns had evolved into a protein binding site. To identify potential proteins that interact with the GK domain, we have performed a yeast twohybrid screen using the GK domain of PSD-95 as bait, and have cloned a novel synaptic protein, GKAP. We now report the primary structure of GKAP and present multiple lines of evidence for its interaction with the GK domain of PSD-95, both in vitro and in vivo. Since the GK domain is characteristic of all MAGUKs, our findings have immediate implications for the functions of the GK domains in other MAGUK proteins.

Materials and Methods

Yeast Two-hybrid Screen and Analysis of GK–GKAP Interaction

Two-hybrid screening was performed using the L40 yeast strain harboring HIS3 and β-gal as reporter genes, as described previously (Bartel et al., 1993; Kim et al., 1995; Niethammer et al., 1996). The GK domain of PSD95 (aa 524-724) or the GKAP clone 2.18 was subcloned into pBHA (lexA fusion vector) and used to screen rat and human brain cDNA libraries constructed in pGAD10 (GAL4 activation domain vector, Clontech, Palo Alto, CA). ∼0.5 × 106 clones of each library were screened with each bait. Deletion variants of the PSD-95 GK domain were created by PCR using specific primers and subcloned in frame into pBHA to generate lexA fusions. GKAP NH2-terminal deletion variants were created by PCR using specific primers and subcloned into pGAD10 to generate GAL4 activation domain fusions. Deletion constructs were tested for interaction in the yeast two-hybrid assay by using HIS3 and β-gal as reporter genes. All DNA constructs were confirmed by DNA sequencing. 5′ RACE was performed by using the Marathon-Ready rat brain cDNAs (Clontech).

Overlay Filter Binding Assay

Overlay binding assay was performed as described (Li et al., 1992). GST fusion constructs containing the GK domains of PSD-95 (aa 524-724), SAP97 (aa 711-911) and chapsyn-110 (aa 658-852), the PDZ1-2 domain of PSD-95 (aa 41-355), and the SH3 domain of PSD-95 (aa 431-500), were amplified by PCR and subcloned in frame into pGEX4T-1 (GST fusion vector, Pharmacia LKB Biotechnology, Piscataway, NJ). GKAP clone 2.1 was subcloned in frame into either pET32a (thioredoxin fusion vector, Novagen, Madison, WI) or pRSETB (hexahistidine (H6)fusion vector, Invitrogen, San Diego, CA). The COOH-terminal region of GKAP clone 2.18 (aa 446-666) was amplified by PCR and subcloned in frame into pRSETB. Fusion proteins were purified by using Glutathione Sepharose 4B (Pharmacia) for GST fusions, or Ni-NTA resin (Invitrogen) for H6 or thioredoxin fusions. In the overlay assays, 200 ng of purified target proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE, transferred to nitrocellulose, and incubated with the probing proteins at a concentration of 1 μg/ml. Fusion proteins were visualized by anti-GST (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA), anti-T7.Tag (Novagen) or anti-thioredoxin (Invitrogen) primary antibodies, HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies, and enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL, Amersham Corp., Arlington Heights, IL).

Antibodies

For GKAP antibodies, H6 fusion proteins of the entire GKAP clone 2.1 or the COOH-terminal region of GKAP (aa 446-666 of clone 2.18) were purified and used for immunization of rabbits. GKAP-specific antibodies were purified using an affinity column (Sulfolink, Pierce, Rockford, IL) coupled with Trx fusion of the same proteins, clone 2.1 or clone 2.18 (aa 446-666). PSD-95 antibody used in immunoprecipitation and immunohistochemistry was generated in guinea pig (Kim et al., 1995), and PSD-95 antibody for immunoblotting was generated in rabbit (Kim et al., 1996). Kv1.4 antibody (Sheng et al., 1992) has been described. Anti-myc (9E10) antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) was used at 1 μg/ml.

Expression Constructs

A GKAP expression construct was made by subcloning the GKAP clone 2.18 into the EcoRI site of GW1 mammalian expression vector (British Biotechnology, Oxford, UK). Expression construct of PSD-95 lacking the GK domain (PSD95ΔGK, deletion of aa 531-711) was made by inverse PCR using GW1-PSD-95 as template with primers flanking the GK domain (oligo 1, CGGGGTACCTTCCATCTGGGTCACCGTC; oligo 2, CGGGGTACCTCAGGCCCCTACATCTGGG). For myc-tagging, an AscI restriction site was introduced at the COOH-terminal end of GKAP in GW1 by inverse PCR, and a cassette encoding the myc epitope (EQKLISEEDL) was inserted into the AscI site. GW1 expression constructs of Kv1.4 and PSD-95 have been described (Kim et al., 1995).

COS Cell Transfection and Coclustering Assay

COS-7 cells were transfected using the lipofectamine method (GIBCOBRL). For coclustering, COS cells on poly-lysine coated coverslips at 40– 60% confluency were incubated in 0.6 ml of OPTI-MEM (GIBCO-BRL) containing 0.6 μg of DNA and 3.6 μl of lipofectamine for 5 h followed by incubation in DMEM medium (GIBCO-BRL). 48 h later, cells were fixed with 2% paraformaldehyde, permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100, and stained with primary antibodies at 1 μg/ml concentration followed by Cy3- or FITC-conjugated secondary antibody incubation (Jackson Immunoresearch, West Grove, PA) at dilutions of 1:1,000 or 1:200, respectively. Immunofluorescence was viewed with a Zeiss Axioskop microscope. For immunoblotting and immunoprecipitation, COS cells on 100-mm tissue culture dishes at 50–70% confluency were incubated in OPTI-MEM containing 4 μg of DNA and 24 μl of lipofectamine. For double or triple transfections, total amount of DNA was kept constant mixing equal amounts of each DNA.

Immunoprecipitation and Immunoblotting

Immunoprecipitations on COS cell lysates and immunoblotting were performed as described (Kim et al., 1996). Coimmunoprecipitation of PSD-95 and GKAP in rat brain was performed on SDS-extracted membrane proteins as described (Müller et al., 1996). Briefly, 250 μg of rat brain membrane proteins were extracted in 60 μl of buffer A (50 mM Tris [pH 7.4], 150 mM NaCl, 2.7 mM of KCl, 5 mM EDTA, 5 mM EGTA, and protease inhibitors) containing 2% SDS at 4°C for 1 h. After centrifugation at 16,000 g for 30 min, the supernatant was diluted with 5× vol of buffer A containing 2% Triton X-100, and used for immunoprecipitation in which PSD-95 antibodies were used at 10 μg/ml final concentration. Immunoblots were incubated with primary antibodies at 1 μg/ml concentration and visualized by peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies (1:1,000 dilution) and chemiluminescent reaction (ECL, Amersham).

Immunohistochemistry on Cultured Hippocampal Neurons

Hippocampal neuronal cultures were prepared from 18-d embryonic rats and maintained in serum-free medium above a glial monolayer as described (Banker and Cowan, 1977). Neurons were fixed and permeabilized 18–35 d after plating, either with cold methanol, or with 4% paraformaldehyde and 0.25% Triton X-100. Cells were visualized by double immunostaining using GKAP2.1 antibody (1 μg/ml) followed by fluorescein-conjugated secondary antibody (2.5 μg/ml), or PSD-95 antibody (1 μg/ml) followed by biotin-conjugated secondary antibody and Texas red–conjugated streptavidin (500 ng/ml; Vector Labs, Burlingame, CA). Fluorescent images of cells were captured on a Photometrics cooled CCD camera mounted on a Zeiss Axioskop microscope.

Results

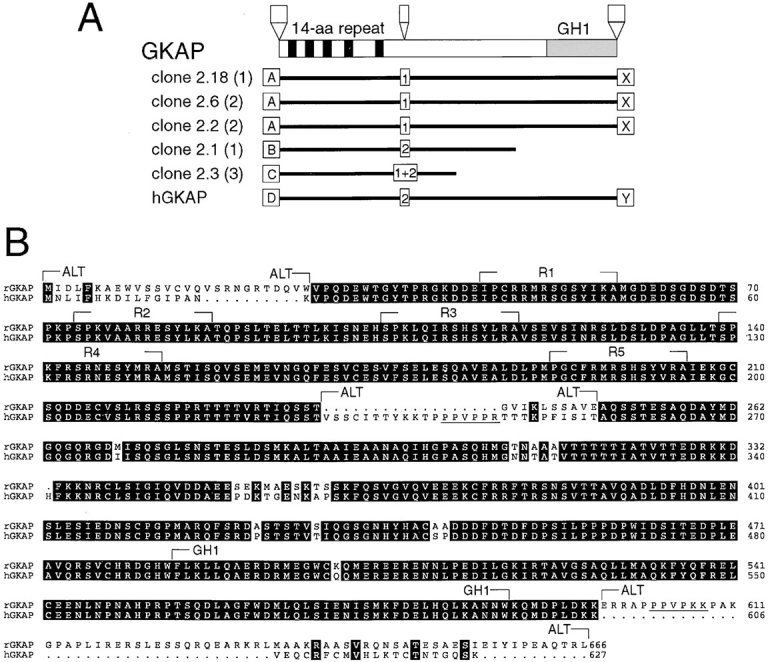

Primary Structure of GKAP

A yeast two-hybrid screen of a rat brain cDNA library using PSD-95 GK domain as bait yielded five independent overlapping cDNA clones of the same gene, which we termed GKAP (Fig. 1 A). A BLAST search of the GenBank database did not reveal homology to any known polypeptides, except for a human EST (expressed sequence tag) clone. The EST clone (accession number Z45015) was obtained, fully sequenced, and identified as a human homologue of GKAP (hGKAP, 98% identity at the amino acid level to rat GKAP; see Fig. 1). The coding sequence of hGKAP predicted a polypeptide of 627 residues and ∼70 kD molecular weight. No significant stretch of hydrophobic residues was found by hydrophobicity analysis suggesting that GKAP is not a transmembrane protein.

Figure 1.

Primary structure of GKAP. (A) Rat brain cDNA clones isolated from the yeast two-hybrid screen using PSD-95 GK domain as bait are shown (black lines) aligned below a schematic of the domain organization of GKAP protein (drawn to scale). Numbers in parentheses refer to the number of times each clone was isolated from the yeast two-hybrid screen. White boxes indicate the presence of alternative inserts at three sites in GKAP, presumably due to alternative splicing (A, B, C, and D; 1, 2; X, Y; indicate different sequences found at these sites). Five 14 aa repeats (black) and the GKAP homology domain 1 (GH1, gray) are represented by boxes. The hGKAP cDNA clone contains a full-length human GKAP coding region and was obtained as an EST (accession No. Z45015, IMAGE consortium). GKAP cDNA clones 2.18, 2.6 and 2.2 contain different lengths of 3′ untranslated region (not shown), but share a common protein coding sequence. (B) Amino acid sequence alignment of rat and human GKAP (Genbank accession numbers U67987 and U67988, respectively). The rat sequence shown is that of GKAP clone 2.18. (R1-R5: 14 aa repeats; GH1: GKAP homology domain 1; ALT, alternative sequence variations or insertions due to presumed alternative splicing). Identical amino acid residues between rat and human sequences are shown in black boxes. Proline-rich motifs that are possible binding sequence for the SH3 domain are underlined.

GKAP clones contained four sequence variations (type A-D) at the NH2-terminal end, presumably due to differential splicing (Fig. 1 A). An in-frame upstream stop codon was present in the 5′ end (type D) of the hGKAP EST clone, and so a putative translation initiation site was assigned to the next methionine, which was in a good Kozak consensus. By 5′-RACE, we were able to isolate the same type D 5′ end with an in-frame upstream stop codon from rat brain cDNA. None of the other 5′ variants of rat GKAP clones (type A, B, and C) isolated by the yeast two-hybrid screen had in-frame upstream stop codons. This is expected from the nature of yeast two- hybrid screening since positive clones are expressed as COOH-terminal fusion proteins. However, expression of the GKAP clone 2.18 (containing the type A insertion) in heterologous cells produced GKAP protein with a size identical to GKAP proteins found in rat brain (see below), allowing us to assign a putative ATG codon in the ‘A' insertion (Fig. 1 B).

In addition to probable splice variation at the NH2-terminus, insertions of a different sequence were found in the middle and at the COOH terminus of GKAP, presumably also due to alternative splicing (Fig. 1 A). Both kinds of middle insertion (1 and 2) and COOH-terminal variants (X and Y) were detected by PCR in both human and rat cDNA libraries. 3′ termination codons were present in both X and Y COOH-terminal variants of GKAP clones, allowing us to designate the COOH terminus of these proteins. The sequence of some of these insertions are of interest. For instance, the type ‘2' middle and the type ‘X' COOH-terminal insertions of the protein (Fig. 1 B) both contain proline-rich potential SH3 domain-binding motifs.

All the cDNAs isolated by the two-hybrid screen overlapped in the NH2-terminal half of GKAP, suggesting that this region mediates the binding to the GK domain of PSD-95 (Fig. 1 A). Five 14–amino acid (14 aa) repeats were noted in the NH2-terminal region. A stretch of ∼100 amino acids near the COOH terminus of GKAP (termed the GH1 domain) showed significant sequence similarity (33–35% identity at the amino acid level) to a region of a C. elegans and a human open reading frame of unknown function (GenBank accession # U00058 and D13633, respectively).

GKAP Interacts Specifically with Members of the PSD-95 Family

In addition to PSD-95, the GK domain is present in SAP97, chapsyn-110/PSD-93, and SAP102 as well as in more distantly related MAGUK proteins (ZO-1, ZO-2, p55, CASK, dlg2, etc.). The binding specificity of GKAP for various different GK domains was tested by yeast twohybrid assay (Fig. 2 A). GKAP interacts strongly with the GK domains of PSD-95, SAP97, and chapsyn-110, but not with that from the tight junction protein, ZO-1 (Willott et al., 1993), indicating that GKAP binding may be specific for members of the PSD-95 subfamily of MAGUKs. Indeed, the amino acid sequence identity between the GK domains of chapsyns is 70–75%, whereas PSD-95 and ZO-1 GK domains share only ∼30% identity.

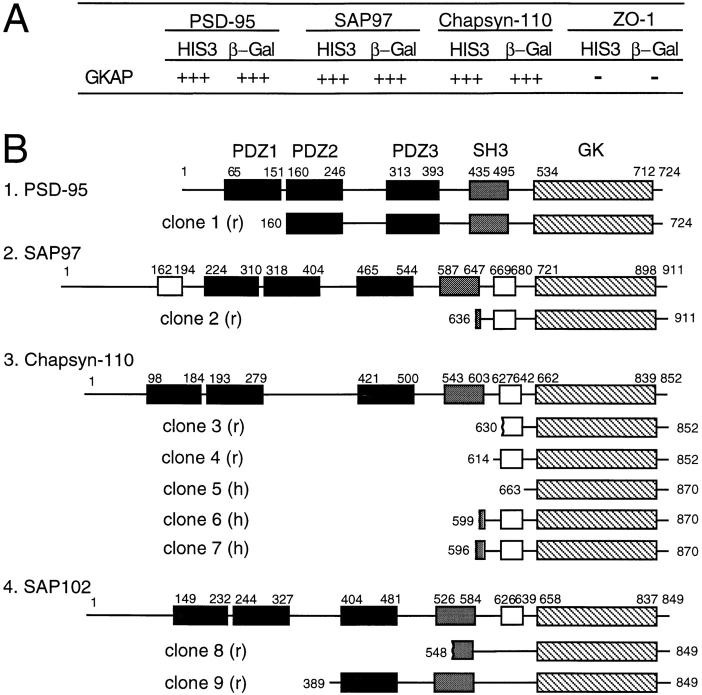

Figure 2.

GKAP interacts specifically with GK domains from members of the PSD-95 family. (A) GK domains from PSD-95, SAP97, chapsyn-110, and ZO-1 were tested for their binding to GKAP in the yeast two-hybrid assay, based on induction of yeast reporter genes HIS3 and β-galactosidase. HIS3 activity (measured by % of colonies growing on histidine-lacking medium): +++ (>60%), ++ (30–60%), + (10–30%), − (no significant growth); β-gal: (time taken for yeast colonies to turn blue in X-gal filter lift assays at room temperature): +++ (<45 min), ++ (45–90 min), + (90–240 min), − (no significant β-gal activity). (B) Results of reverse yeast two-hybrid screening of rat and human brain cDNA libraries using GKAP (clone 2.18) as bait. 9 of 10 GKAP-interacting clones contained the GK domains of one of the four known PSD-95 family members. These interacting clones are shown aligned below the a schematic diagram of the corresponding full-length protein. r, or h, indicates rat or human cDNA. Highlighted are: PDZ domains (black), SH3 domains (gray), GK domains (hatched), alternatively spliced insertions (open box). Numbers refer to amino acid residues at the boundaries of the cDNA clones and highlighted domains.

To further test the specificity of the GK-GKAP interaction, we performed a reverse yeast two-hybrid screen using the entire GKAP clone 2.18 as bait. The screen yielded a total of ten independent GKAP-interacting clones, nine of which were cDNA fragments containing GK domains of one of the four known chapsyns: PSD-95, SAP97, chapsyn-110, and SAP102 (Fig. 2 B).

Domains Mediating Interaction between the GK and GKAP

Minimal sequence requirements for GK-GKAP binding were determined using deletions of the GK domain of PSD-95 (Fig. 3 A), and of the NH2-terminal region of GKAP (Fig. 3 B). Small deletions into either the NH2- or COOH-terminal side of the GK domain resulted in the loss of interaction (Fig. 3 A), suggesting that the entire GK domain is required for binding to GKAP. The last 13 amino acids of PSD-95 COOH-terminal to the GK domain were not required for GKAP binding.

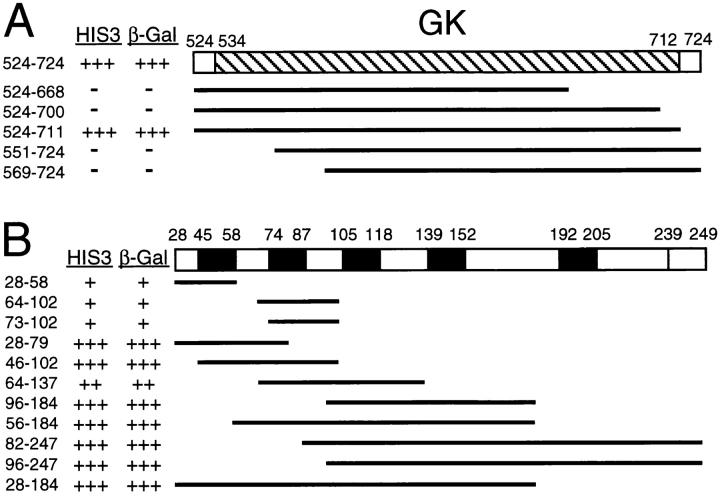

Figure 3.

Minimal domains required for binding between PSD-95 GK domain and GKAP. (A) Various deletion variants of the GK domain of PSD-95 are shown as black lines aligned below the COOH-terminal region of PSD-95 in which the GK domain is represented by hatched box (aa 534-712). Each GK deletion variant was tested for interaction with GKAP clone 2.18 in the yeast two-hybrid system. Numbers refer to the amino acid residues that define the boundaries of each construct. HIS3 and β-gal reporter gene induction was measured as in Fig. 2. (B) Deletion variants of GKAP are shown schematically as black lines aligned below the NH2-terminal region of GKAP. GKAP deletion variants were tested for interaction with PSD-95 GK domain (aa 524-724) as in A.

On the GKAP side, we tested whether the 14 aa repeats found near the NH2 terminus are involved in GK binding (Fig. 3 B). In the yeast two-hybrid assay, fragments of GKAP incorporating the first repeat (aa 28-58) or the second repeat (aa 64-102) showed a weak but significant interaction with the GK domain. Constructs that included two or more of the 14 aa repeats showed much stronger binding. Moreover, essentially non-overlapping constructs containing the first and second repeats (aa 46-102) or containing the third and fourth repeats (aa 96-104), were each able to interact strongly with the PSD-95 GK domain. Since the intervening sequences between the repeats are quite dissimilar, the above results are consistent with the idea that the 14 aa repeats of GKAP may independently contribute to the overall binding affinity for GK. However, a 1,000-fold excess of a peptide (SPKPSPKVAARRESYLKATQ) corresponding to the second 14 aa repeat (underlined) was unable to inhibit GK-GKAP binding in solution binding or in filter binding assays (data not shown). This negative result could mean that these 14 aa repeats are not directly important in GK-GKAP interaction. Alternatively, the structural context of the 14 aa repeats is critical, i.e., the correct “folding” of the 14 aa repeats is dependent on surrounding sequences that were missing in the synthetic peptide. Thirdly, cooperative binding of the 5 repeats of GKAP may result in such a strong avidity that competition with a single 14 aa repeat is inadequate, even at high relative concentrations. Finally, although the 5 repeats are similar, they are not identical in sequence, so their binding specificities may be slightly different; in this case, a single peptide may not be able to compete the overall GKAP binding efficiently. These reasons are not mutually exclusive.

Direct Interaction between the GK Domain and GKAP

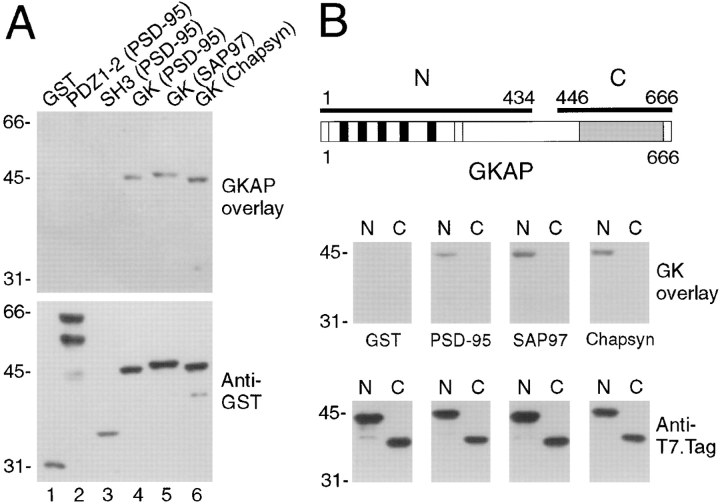

To show direct biochemical association between the GK domain and GKAP, overlay filter binding assays were performed. GKAP fusion protein bound specifically to the GK domains of PSD-95, SAP97, and chapsyn-110 (Fig. 4 A), but not to negative controls including GST alone and the PDZ1-2 and SH3 domains of PSD-95.

Figure 4.

Direct GK-GKAP binding in overlay filter binding assays. (A) GST-fusion proteins containing no insert (GST), or different regions of PSD-95 (PDZ1-2, SH3, or the GK domain), or GK domains of SAP97 and chapsyn-110, were separated by SDSPAGE, transferred to a nitrocellulose and probed with TrxGKAP (thioredoxin fusion protein of GKAP clone 2.1) (upper panel). Bound GKAP was visualized with anti-Trx antibody. After stripping, the same membrane was reprobed with anti-GST antibody to show the relative positions and amounts of the various target GST fusion proteins (lower panel). GKAP binds specifically to GK domains from PSD-95, SAP97, and chapsyn-110, but not to PDZ1-2, SH3 domains of PSD-95 or to GST alone. Positions of size markers are indicated in kD. (B) H6 fusion proteins of NH2- and COOH-terminal regions of GKAP (top diagram) were separated by SDS-PAGE, transferred to nitrocellulose, and probed with GST-GK fusions of PSD-95, SAP97, chapsyn-110, or with GST alone, as indicated (middle panels). Bound GK was visualized with anti-GST antibody, followed by stripping and reprobing with anti-T7-Tag antibody to show the relative positions and amounts of target GKAP fusion proteins on the membrane (bottom panels). The different GK domains, but not GST alone, bind specifically to the NH2-terminal region of GKAP that contains the 14 aa repeats (black boxes).

The filter binding assay was also performed in a reverse orientation as further confirmation of the interaction. The GK domains from PSD-95, SAP97, and chapsyn-110 specifically bound to the NH2-terminal half of GKAP (containing the 14 aa repeats) but not to the COOH-terminal region of GKAP (containing the GH1 domain) (Fig. 4 B). Thus the NH2-terminal region of GKAP binds directly to the GK domains of PSD-95 family proteins, in agreement with two-hybrid analysis.

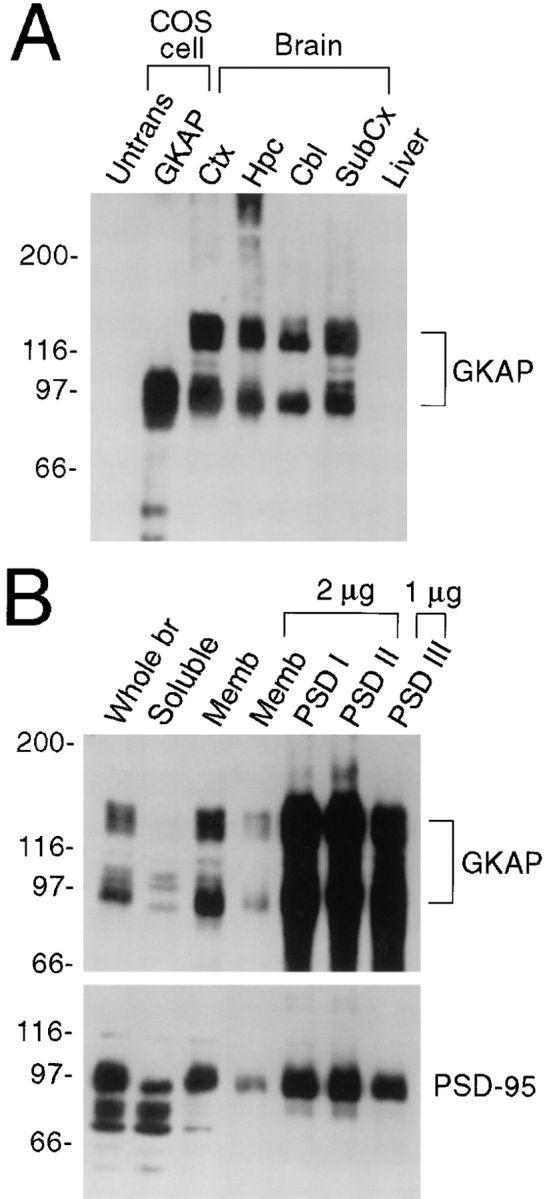

GKAP Is Enriched in the Postsynaptic Density

GKAP antibodies (termed GKAP2.1) were raised against the NH2-terminal two-thirds of GKAP, using as immunogen a H6 fusion protein of GKAP clone 2.1. Affinity-purified GKAP2.1 antibodies specifically recognized two prominent bands of ∼95 kD and ∼130 kD on immunoblots of rat brain membranes (Fig. 5 A). The 95-kD brain band comigrated exactly with GKAP expressed in COS-7 cells transfected with presumptive full-length GKAP cDNA (clone 2.18; Fig. 5 A). The nature of the ∼130-kD band is less clear, but both the 95-kD and the 130-kD bands almost certainly represent GKAP proteins because the identical bands were also recognized by an independent antibody raised against a non-overlapping COOH-terminal part of GKAP (aa 446-666 of clone 2.18) (data not shown). The 130-kD immunoreactive polypeptide in rat brain may be the result of GKAP variants that have a longer NH2-terminal extension than represented in our cDNA clones. As noted above, some of the GKAP cDNAs do not have upstream stop codons, so they may be incomplete open reading frames. Alternatively, the 130-kD band might reflect posttranslational modifications of GKAP that do not occur in COS-7 cells. Whatever the case, the 95-kD and 130kD bands codistribute and cofractionate very similarly (Fig. 5), and coimmunoprecipitate with PSD-95 in rat brain (see below), providing further evidence that they both represent GKAP proteins.

Figure 5.

Expression pattern of GKAP protein in rat brain. (A) Specificity of GKAP antibodies and differential regional expression of GKAP in rat brain. Whole cell extracts of untransfected COS-7 cells (Untrans.), or of COS cells transfected with GKAP cDNA, were analyzed by immunoblotting with GKAP2.1 antibodies, along with membrane fractions (10 μg protein) from different regions of brain or liver, as indicated. Ctx (cortex), Hpc (hippocampus), Cbl (cerebellum), Subcx (subcortical regions). Positions of molecular size markers are shown in kD. (B) Immunoblot analysis of subcellular fractionation of GKAP. Lanes were loaded with rat brain fractions, as follows: Whole br (total brain homogenate, 20 μg protein), Soluble (S100 supernatant fraction of brain homogenate, 30 μg). Memb (crude synaptosomal membrane fraction, 10 μg or 2 μg, as indicated); PSDI, PSDII, and PSDIII (purified PSD fractions after extraction with Triton X-100 once [I], twice [II], or with Triton X-100 followed by sarkosyl [III]). Filters were probed with GKAP and PSD-95 antibodies, as indicated. (Equal percentages [rather than equal mass] of membrane and soluble fractions were loaded—the soluble fraction contained three times higher concentration of total protein than the membrane fraction. To show relative purification in the PSD fractions, only 2 μg of PSDI, PSDII, and 1 μg of PSDIII were immunoblotted and compared with 2 μg of synaptosomal membrane fraction.)

In the rat brain, GKAP is widely distributed in membrane preparations from different regions of the brain but shows no detectable expression in liver (Fig. 5 A). GKAP proteins are predominantly associated with the membrane rather than the soluble fractions of rat brain (Fig. 5 B). And like PSD-95, an abundant postsynaptic density (PSD) protein, GKAP is highly enriched in PSD fractions, where it is resistant to Triton and sarkosyl detergent extraction (Fig. 5 B). The biochemical cofractionation of PSD-95 and GKAP is consistent with these proteins being associated at postsynaptic sites in rat brain.

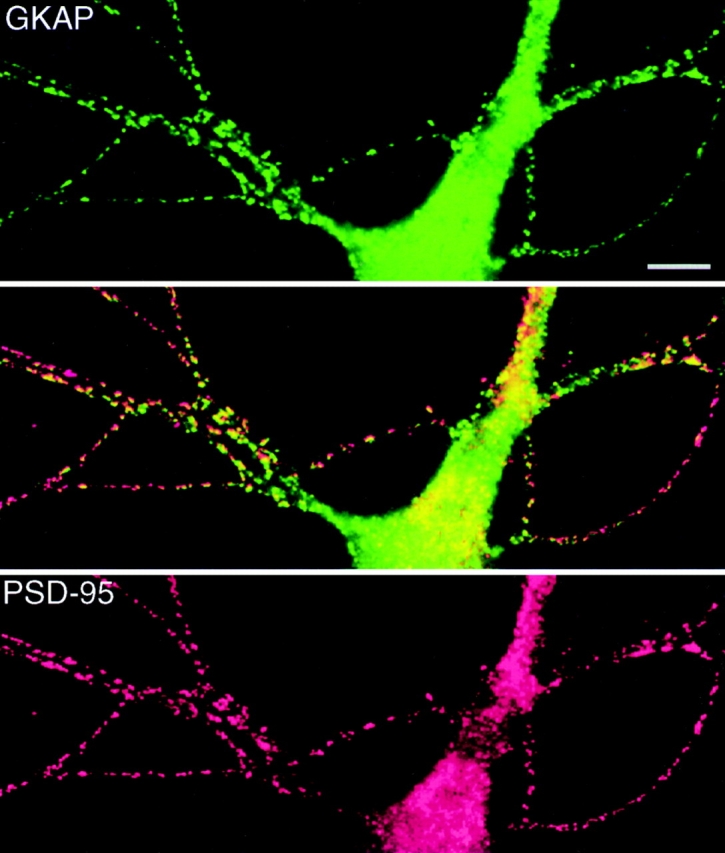

In Vivo Association between PSD-95 and GKAP

Colocalization of GKAP and PSD-95 in neurons is a prerequisite for association in vivo. In double immunofluorescence studies, we found GKAP immunoreactivity to colocalize strikingly with PSD-95 in discrete puncta along the dendrites of cultured hippocampal neurons (Fig. 6). The punctate localizations of PSD-95 and GKAP are at presumptive synaptic sites, since they are apposed to presynaptic markers such as SV2 and synaptophysin (data not shown). The colocalization of PSD-95 and GKAP indicates they are both synaptic proteins but does not prove that they interact directly in vivo.

Figure 6.

Colocalization of GKAP and PSD-95 in cultured hippocampal neurons. Double immunofluorescence labeling of neurons with rabbit anti-GKAP (GKAP2.1) antibodies (green, top panel), and with guinea pig anti-PSD-95 antibodies (red, bottom panel). Middle panel shows superposition of the two images. GKAP and PSD-95 immunoreactivities are colocalized (yellow) in a punctate pattern along dendrites. Bar, 10 μm.

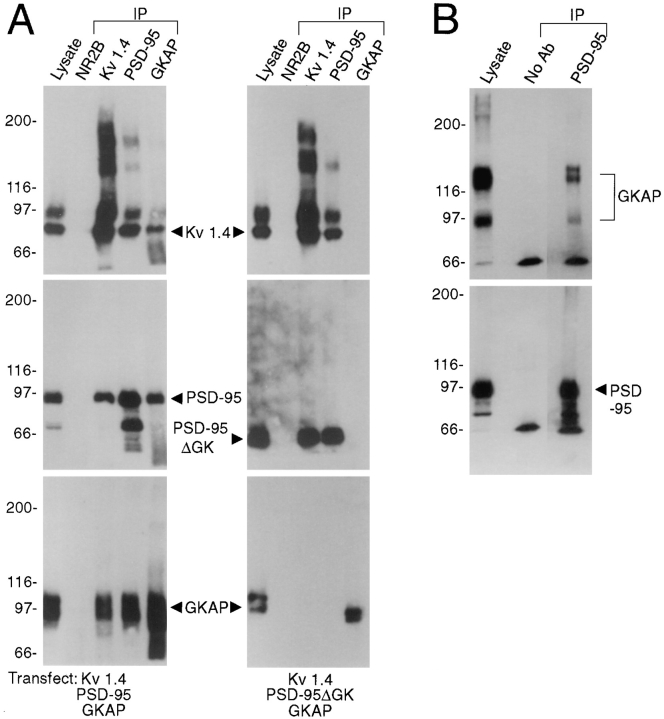

To demonstrate biochemical association of PSD-95 and GKAP in a cellular context, we have performed coimmunoprecipitation of PSD-95 and GKAP from transfected heterologous cells as well as from rat brain. Since PSD-95 can also interact with Shaker-type K+ channels via its PDZ domains (Kim et al., 1995), we tried coimmunoprecipitation of PSD-95, GKAP, and Shaker-type subunit Kv1.4 from COS cells triply transfected with all three genes (Fig. 7 A, left). Antibodies specific for each of the three proteins were able to immunoprecipitate the other two proteins in addition to their cognate antigen, while none of these proteins were immunoprecipitated by control NR2B antibodies. The finding that anti-Kv1.4 antibodies can precipitate GKAP, and that GKAP antibodies can bring down Kv1.4, is of special significance, since it implies the formation of a ternary complex containing the K+ channel and GKAP linked together by PSD-95. In confirmation of this, when the wild-type PSD-95 was replaced by a mutant lacking only the GK domain (PSD-95ΔGK) in the triple transfection, GKAP could no longer be coimmunoprecipitated by Kv1.4 or PSD-95 antibodies, while the interaction between PSD-95ΔGK and Kv1.4 was maintained (Fig. 7 A, right). Thus, there is no direct association of Kv1.4 and GKAP. These results are consistent with the formation of a ternary complex in which PSD-95 binds to the K+ channel via its PDZ domains and to GKAP via its GK domain.

Figure 7.

Coimmunoprecipitation of PSD95 and GKAP from cotransfected COS cells and from rat brain. (A) Extracts from COS-7 cells triply transfected with either Kv1.4 + PSD-95 + GKAP (left), or with Kv1.4 + PSD-95ΔGK + GKAP (right), were immunoprecipitated with Kv1.4, PSD-95, GKAP, or negative control NR2B antibodies, as indicated. Immunoprecipitates were then immunoblotted for Kv1.4, PSD-95, and GKAP, as indicated. First lane (lysate) was loaded directly with the transfected cell lysate (5% of input). (B) Extracts of rat cerebral cortex synaptosomal membranes were immunoprecipitated with PSD-95 antibodies, or with no primary antibodies. Immunoprecipitates were then immunoblotted with GKAP and PSD-95 antibodies as indicated. First lane (lysate) was loaded with detergent extract of rat cerebral cortex used for the immunoprecipitation (5% of input).

To demonstrate existence of a protein complex containing PSD-95 and GKAP in the rat brain, coimmunoprecipitation was performed from solubilized brain membranes. As noted above (Fig. 5), neither PSD-95 nor GKAP are extracted by mild detergents. Nevertheless, following a SDS/Triton extraction protocol recently developed by Huganir and colleagues (Müller et al., 1996) for coimmunoprecipitation of postsynaptic density proteins, GKAP was efficiently solubilized and could be coimmunoprecipitated with PSD-95 by PSD-95 antibodies (Fig. 7 B).

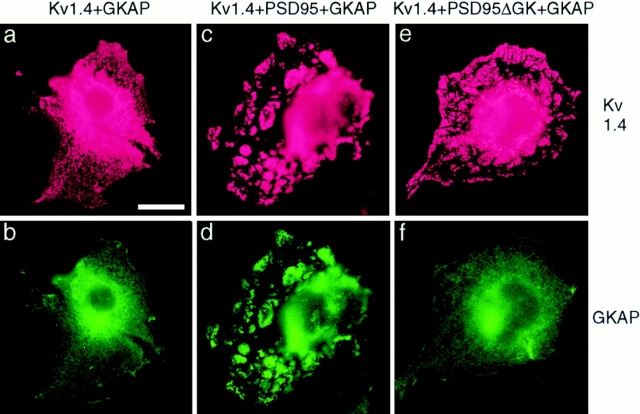

GKAP Is Recruited into Ion Channel/PSD-95 Clusters

We have previously shown that PSD-95 and its relatives have the remarkable property of clustering Shaker K+ channels and NMDA receptors in heterologous cells. To test whether GKAP is recruited into ion channel/PSD-95 clusters, we coexpressed GKAP with Kv1.4 and PSD-95 in COS-7 cells (Fig. 8). When Kv1.4 and GKAP are cotransfected in the absence of PSD-95, both Kv1.4 and GKAP proteins are diffusely distributed in a reticular pattern in the cell (Fig. 8, a and b). In triply (Kv1.4 + PSD-95 + GKAP) transfected cells, plaque-like clusters of Kv1.4 are formed, and GKAP immunoreactivity colocalized exactly with Kv1.4 in these clusters (Fig. 8, c and d). In separate experiments, PSD-95 also coclusters with Kv1.4 in these triply transfected cells (data not shown) in agreement with earlier findings (Kim et al., 1995). Thus, GKAP recruitment to Kv1.4/PSD-95 coclusters presumably reflects binding of GKAP to PSD-95. In support of this conclusion, when PSD-95 is replaced with mutant PSD-95ΔGK in the same triple transfection, the colocalization of GKAP in Kv1.4 clusters is lost. GKAP is now diffusely distributed in the cell, while the clustering of KV1.4 is maintained (Fig. 8, e and f). These results indicate that GKAP recruitment to Kv1.4/PSD-95 clusters depends on the GK domain of PSD-95. Interestingly, clustering of Kv1.4 by PSD-95 does not require the GK domain (Fig. 8 e). Similarly, GKAP was also recruited to clusters formed by PSD-95 and NMDA receptor subunit NR2B suggesting that PSD-95 can bring GKAP in close proximity to NMDA receptor channels (data not shown). Taken together with the coimmunoprecipitation data (Fig. 7 A), these results indicate that by virtue of its multimodular protein binding domains, PSD-95 can nucleate a macroscopic protein cluster containing both ion channels and GKAP.

Figure 8.

Recruitment of GKAP into Kv1.4/PSD-95 coclusters in COS cells, studied by double immunofluorescence labeling. In cells cotransfected with Kv1.4 and GKAP, (a and b), both Kv1.4 (a, red) and GKAP (b, green) are mainly distributed in a diffuse intracellular reticular pattern with perinuclear accumulation, with no evidence of interaction. In cells triply transfected with Kv1.4 + PSD-95 + GKAP (c and d), GKAP (d) now colocalized in clusters with Kv1.4 (c) and PSD-95 (data not shown). However, in cells triply transfected with Kv1.4 + PSD-95ΔGK + GKAP (e and f), Kv1.4 is still found in clusters (e) but GKAP no longer colocalizes with Kv1.4 and is instead diffusely distributed in the cell (f). The Kv1.4 clusters shown here are identical in nature to those formed with coexpression of Kv1.4 + PSD-95 in the absence of GKAP. Kv1.4 was visualized by rabbit anti-Kv1.4 antibodies and Cy3-conjugated anti–rabbit secondary antibodies. A myc-epitope tagged GKAP construct was used in these experiments to allow visualization of GKAP using mouse anti-myc monoclonal antibodies (9E10) and FITC-conjugated anti–mouse secondary antibodies. Bar, 5 μm.

Discussion

Functions of the GK Domain

In this paper, we have presented several lines of evidence that GKAP is a synaptic protein in rat brain and that it associates directly with PSD-95 and with its close relatives by binding to their COOH-terminal GK domains. These findings imply that the GK domain of PSD-95 and other MAGUKs may have a novel function as a site for protein– protein interaction. This implication is especially interesting given that the GK domain of the PSD-95 family are predicted to be inactive as guanylate kinase enzymes.

What is currently known about the functions of the GK domain? There is a Drosophila dlg mutant allele (dlgv59) in which most of the GK domain is deleted (Woods and Bryant, 1991), and this mutant displays two facets of the dlg null phenotype. First, the mutation results in neoplastic overgrowth of epithelial cells of imaginal discs (Woods and Bryant, 1991). Second, the morphology of the postsynaptic specialization of the larval neuromuscular junction is poorly developed (Lahey et al., 1994; Guan et al., 1996). Notably, however, the GK-specific mutation dlgv59 does not affect Shaker channel clustering at the NMJ, which is disrupted in dlg null mutants (Tejedor et al., 1997). Although there have been speculations on the possible signaling functions of the GK domain based on its resemblance to guanylate kinases, the molecular basis for these dlg mutant phenotypes is unknown. The interaction of GKAP with the GK domain provides the first indication that the GK domain (presumable originating from a metabolic guanylate kinase), may have evolved a new function for protein–protein interaction. This raises the possibility that the requirement for the GK domain in tumor suppression and in postsynaptic organization by dlg reflects GK domain interactions with downstream GKAP or GKAPlike proteins.

The specific interaction of GKAP with GK domains of the PSD-95 family, but not with ZO-1, raises an interesting question: Do the GK domains of more distantly related MAGUKs specifically interact with their own GKAP-like proteins? The GK domains of the PSD-95 family share 70–75% amino acid sequence identity among themselves and with Drosophila DLG, but they share only 30% identity with ZO-1 or ZO-2's GK domain (Willott et al., 1993; Jesaitis and Goodenough, 1994). This could account for the differential specificity of GKAP binding shown by these two groups of MAGUKs. There are also other GKcontaining proteins such as LIN-2/CASK (Hata et al., 1996; Hoskins et al., 1996), p55 (Ruff et al., 1991), and dlg2 (Mazoyer et al., 1995). The GK domains of this group of MAGUKs are 45–60% identical to each other but share only ∼30% sequence identity with either the PSD-95 family or with ZO-1. We suggest the possibility that different subgroups of the MAGUK superfamily interact with distinct GKAP-like proteins via their divergent GK domains.

Functional Significance of GKAP Interaction

PSD-95 can mediate the coimmunoprecipitation of GKAP with Shaker K+ channels (Fig. 7 A) and recruits GKAP into ion channel/PSD-95 coclusters (Fig. 8). Since PSD-95 binds to the ion channel subunits via its NH2-terminal PDZ domains, and to GKAP via its COOH-terminal GK domain, PSD-95 can in essence function as a bridging molecule between ion channel proteins and GKAP. Given that PSD-95 also binds to neuronal nitric oxide synthase via its PDZ2 domain (Brenman et al., 1996), the GKGKAP interaction further emphasizes the importance of PSD-95 as a multi-modular scaffold that links ion channels to several different intracellular proteins. In this context, it is interesting that although the GK domain is required for formation of the triple complex of Kv1.4/PSD-95/GKAP, it is not needed for binding and clustering of the K+ channel by PSD-95 in heterologous cells. In neurons, however, a reasonable speculation is that GKAP-GK binding is involved in the anchoring of channel/PSD-95 clusters to the postsynaptic density. Consistent with a structural role is the relative abundance of GKAP, which we estimate to be ∼0.01–0.1% by mass of total brain membrane protein, and ∼1% of postsynaptic density fractions.

By interacting with other proteins, GKAP may function as an adapter protein linking ion channel/PSD-95 clusters to the subsynaptic cytoskeleton or to downstream signaling molecules. One potential protein binding site is offered by the COOH-terminal GH1 domain of GKAP, which is highly conserved in two other proteins of unknown function. In addition, GKAP incorporates alternatively spliced insertions at three different points of the gene. Some of these insertions contain proline-rich motifs, (PXXPXR/K) that may be recognized by SH3 domains of other proteins (Cohen et al., 1995).

Although the GK domain is not required for channel clustering by PSD-95 in heterologous cells, it is conceivable that GKAP may cross-link PSD-95 molecules in vivo by binding to their GK domains, thereby strengthening the cluster scaffold. The NH2-terminal region of GKAP contains five 14 aa repeats, each of which seems capable of binding to GK domains. Certainly, a segment of this region containing the first two 14 aa repeats binds to PSD95's GK domain as strongly as an independent segment containing the third and fourth repeats. This finding suggests that the region containing the 14 aa repeats is at least divalent with respect to binding GK, and raises the possibility that GKAP can bridge between different molecules of PSD-95. Since GKAP can bind to all members of the PSD-95 family, such cross-linking could contribute to heteromultimerization of different chapsyns and the assembly of heterogeneous clusters (Kim et al., 1996). It is also noteworthy that three out of the five 14 aa repeats contain at their NH2-terminal ends a consensus protein kinase C phosphorylation site (S/TXK/R) raising the possibility that the GK-GKAP interaction is modulated by protein kinase C. And given the known ability of the GK domain to bind GMP, it will be interesting to determine if nucleotides can regulate GK-GKAP binding. Many interesting questions are raised by the isolation and characterization of GKAP. Ultimately, however, the function of GKAP will be defined only when we know what other proteins it interacts with, and when we can delete its function by genetic knockout or dominant negative approaches.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Alan Fanning and James Anderson for the gift of ZO-1 DNA, Fu-Chia Yang for excellent experimental support, and Elaine Aidonidis for helping with the manuscript.

This work was supported by the Lucille P. Markey Charitable Trust (A.M. Craig) and National Institutes of Health grants NS33184 (A.M. Craig). M. Sheng is Assistant Investigator of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

Abbreviations used in this paper

- GKAP

guanylate kinase-associated protein

- PSD-95

postsynaptic density-95

- SAP90

synapse-associated protein 90

- NMDA

N-methyl-d-aspartate

- ZO-1

zona occludens-1

Footnotes

Please address all correspondence to M. Sheng, HHMI, (Wellman 423), Massachusetts General Hospital, 50 Blossom Street, Boston, MA 02114. Tel.: (617) 724-2800. Fax: (617) 724-2805. E-Mail: sheng@helix.mgh.harvard.edu

References

- Anderson JM. Cell signalling-MAGUK magic. Curr Biol. 1996;6:382–384. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(02)00501-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banker GA, Cowan WM. Rat hippocampal neurons in dispersed cell culture. Brain Res. 1977;126:397–425. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(77)90594-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartel, P.L., C.-T. Chien, R. Sternglanz, and S. Fields. 1993. Using the 2-hybrid system to detect protein-protein interactions. In Cellular Interactions in Development: A Practical Approach, Oxford University Press, Oxford. 153– 179.

- Brenman JE, Chao DS, Gee SH, McGee AW, Craven SE, Santillano DR, Wu Z, Huang F, Xia H, Peters MF, et al. Interaction of nitric oxide synthase with the postsynaptic density protein PSD-95 and α1-syntrophin mediated by PDZ domains. Cell. 1996;84:757–767. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81053-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho K-O, Hunt CA, Kennedy MB. The rat brain postsynaptic density fraction contains a homolog of the drosophila discs-large tumor suppressor protein. Neuron. 1992;9:929–942. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(92)90245-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen GB, Ren R, Baltimore D. Modular binding domains in signal transduction proteins. Cell. 1995;80:237–248. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90406-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doyle DA, Lee A, Lewis J, Kim E, Sheng M, MacKinnon R. Crystal structures of a complexed and peptide-free membrane protein-binding domain: molecular basis of peptide recognition by PDZ. Cell. 1996;85:1067–1076. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81307-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Froehner SC. Regulation of ion channel distribution at synapses. Ann Rev Neurosci. 1993;16:347–368. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ne.16.030193.002023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guan B, Hartmann B, Kho Y-H, Gorczyca M, Budnik V. The Drosophila tumor suppressor gene, dlg, is involved in structural plasticity at a glutamatergic synapse. Curr Biol. 1996;6:695–706. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(09)00451-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall Z, Sanes JR. Synaptic structure and development: the neuromuscular junction. Neuron. 1993;10:99–122. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(05)80031-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hata Y, Butz S, Südhof TC. CASK: a novel dlg/PSD95 homolog with an N-terminal calmodulin-dependent protein kinase domain identified by interaction with neurexins. J Neurosci. 1996;16:2488–2494. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-08-02488.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoskins R, Hajnal AF, Harp SA, Kim SK. The C. elegansvulval induction gene lin-2 encodes a member of the MAGUK family of cell junction proteins. Development. 1996;122:97–111. doi: 10.1242/dev.122.1.97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jesaitis LA, Goodenough DA. Molecular characterization and tissue distribution of ZO-2, a tight junction protein homologous to ZO-1 and the Drosophiladiscs-large tumor suppressor protein. J Cell Biol. 1994;124:949–961. doi: 10.1083/jcb.124.6.949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim E, Sheng M. Differential K+channel clustering activity of PSD-95 and SAP97, two related membrane-associated putative guanylate kinases. Neuropharmacol. 1996;35:993–1000. doi: 10.1016/0028-3908(96)00093-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim E, Niethammer M, Rothschild A, Jan YN, Sheng M. Clustering of shaker-type K+channels by interaction with a family of membraneassociated guanylate kinases. Nature (Lond) 1995;378:85–88. doi: 10.1038/378085a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim E, Cho K-O, Rothschild A, Sheng M. Heteromultimerization and NMDA receptor-clustering activity of chapsyn-110, a member of the PSD-95 family of proteins. Neuron. 1996;17:103–113. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80284-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kistner U, Garner CC, Linial M. Nucleotide binding by the synapse associated protein SAP90, . FEBS Lett. 1995;359:159–163. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(95)00030-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kistner U, Wenzel BM, Veh RW, Cases-Langhoff C, Garner AM, Apeltauer U, Voss B, Gundelfinger ED, Garner CC. SAP90, a rat presynaptic protein related to the product of the Drosophila tumor suppressor gene dlg-A. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:4580–4583. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kornau H-C, Schenker LT, Kennedy MB, Seeburg PH. Domain interaction between NMDA receptor subunits and the postsynaptic density protein PSD-95. Science (Wash DC) 1995;269:1737–1740. doi: 10.1126/science.7569905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lahey T, Gorczyca M, Jia X-X, Budnik V. The Drosophila tumor suppressor gene dlgis required for normal synaptic bouton structure. Neuron. 1994;13:823–835. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(94)90249-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li M, Jan YN, Jan LY. Specification of subunit assembly by the hydrophilic amino-terminal domain of the shaker potassium channel. Science (Wash DC) 1992;257:1225–1230. doi: 10.1126/science.1519059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lue RA, Marfatia SM, Branton D, Chishti AH. Cloning and characterization of hdlg: the human homologue of the Drosophiladiscs large tumor suppressor binds to protein 4.1. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:9818–9822. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.21.9818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsumine A, Ogai A, Senda T, Okumura N, Satoh K, Baeg G-H, Kawahara T, Kobayashi S, Okada M, Toyoshima K, et al. Binding of APC to the human homolog of the Drosophiladiscs large tumor suppressor protein. Science (Wash DC) 1996;272:1020–1023. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5264.1020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazoyer S, Gayther SA, Nagai MA, Smith SA, Dunning A, van Rensburg EJ, Albertsen H, White R, Ponder BA. A gene (dlg2) located at 17q12-q21 encodes a new homologue of the Drosophilatumor suppressor dlg-A. Genomics. 1995;28:25–31. doi: 10.1006/geno.1995.1101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Müller BM, Kistner U, Kindler S, Chung WJ, Kuhlendahl S, Lau L-F, Veh RW, Huganir RL, Gundelfinger ED, Garner CC. SAP102, a novel postsynaptic protein that interacts with the cytoplasmic tail of the NMDA receptor subunit NR2B. Neuron. 1996;17:255–265. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80157-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Müller BM, Kistner U, Veh RW, Cases-Langhoff C, Becker B, Gundelfinger ED, Garner CC. Molecular characterization and spatial distribution of SAP97, a novel presynaptic protein homologous to SAP90 and the Drosophiladiscs-large tumor suppressor protein. J Neurosci. 1995;15:2354–2366. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-03-02354.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niethammer M, Kim E, Sheng M. Interaction between the C terminus of NMDA receptor subunits and multiple members of the PSD-95 family of membrane-associated guanylate kinases. J Neurosci. 1996;16:2157–2163. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-07-02157.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruff P, Speicher DW, Husain-Chishti A. Molecular identification of a major palmitoylated erythrocyte membrane protein containing the srchomology 3 motif. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:6595–6599. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.15.6595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheng M. PDZs and receptor/channel clustering: rounding up the latest suspects. Neuron. 1996;17:575–578. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80190-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheng M, Kim E. Ion channel associated proteins. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 1996;6:602–608. doi: 10.1016/s0959-4388(96)80091-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheng M, Tsaur M-L, Jan YN, Jan LY. Subcellular segregation of two A-type K+channel proteins in rat central neurons. Neuron. 1992;9:271–284. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(92)90166-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tejedor FJ, Bokhari A, Rogero O, Gorczyca M, Kim E, Sheng M, Bhandari P, Singh S, Budnik V. Essential role for dlg in synaptic clustering of Shaker K+channels in vivo. J Neurosci. 1997;17:152–159. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-01-00152.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willott E, Balda MS, Fanning AS, Jameson B, Van Itallie C, Anderson JM. The tight junction protein ZO-1 is homologous to the Drosophiladiscs-large tumor suppressor protein of septate junctions. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:7834–7838. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.16.7834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woods DF, Bryant PJ. The discs-large tumor suppressor gene of drosophila encodes a guanylate kinase homolog localized at septate junctions. Cell. 1991;66:451–464. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(81)90009-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]