Abstract

Cytosine-methylation changes are stable and thought to be among the earliest events in tumorigenesis. Theoretically, DNA carrying tumor-specifying methylation patterns escape the tumors and may be found circulating in the sera from cancer patients, thus providing the basis for development of noninvasive clinical tests for early cancer detection. Indeed, using methylation-specific PCR-based techniques, several groups reported the detection of tumor-associated methylated DNA in the sera from cancer patients with varying clinical success. However, by design, such analytical approaches allow assessment of the presence of molecules with only one methylation pattern, leaving the bigger picture unexplored. The limited knowledge about circulating DNA methylation patterns hinders the efficient development of clinical methylation tests and testing platforms. Here, we report the results of a comprehensive methylation pattern analysis from breast cancer clinical tissues and sera obtained using massively parallel bisulphite pyrosequencing. The four loci studied were recently discovered by our group, and demonstrated to be powerful epigenetic biomarkers of breast cancer. The detailed analysis of more than 700,000 DNA fragments derived from more than 50 individuals (cancer and cancer-free) revealed an unappreciated complexity of genomic cytosine-methylation patterns in both tissue derived and circulating DNAs. Both tumor and cancer-free tissues (as well as sera) contained molecules with nearly every conceivable cytosine-methylation pattern at each locus. Tumor samples displayed more variation in methylation level than normal samples. Importantly, by establishing the methylation landscape within circulating DNA, this study has better defined the development challenges facing DNA methylation-based cancer-detection tests.

Cytosine methylation is a centrally important DNA modification for the maintenance of large genomes. While many proteins and biochemical mechanisms responsible for this modification have been revealed, the regulatory processes specifying the somatic patterns observed remain veiled (Bestor 2000). The central importance of proper DNA methylation maintenance is highlighted in diseases such as cancer, where the normal patterns are lost. DNA that is normally methylated becomes unmethylated, while DNA that is supposed to be methylation free obtains the modification (Herman et al. 1996; Baylin 2005; Feinberg et al. 2006). This apparent redistribution of normal methylation patterning is regionally complex and is thought to be among the earliest molecular alterations during tumorigenesis (Lund and van Lohuizen 2004; Baylin 2005; Laird 2005; Ducasse and Brown 2006; Feinberg et al. 2006); therefore, abnormal methylation marks may be useful as biomarkers for the early detection and diagnosis of different types of cancer (Paluszczak and Baer-Dubowska 2006; J.M. Ordway, M.A. Budiman, Y. Korshunova, R.K. Maloney, J.A. Bedell, R.W. Citek, B. Bacher, S. Peterson, T. Rholfing, J. Hall, et al., in prep.).

Serum is a very attractive medium for the development of cancer detection assays as is obtained through a simple, relatively noninvasive procedure. Several reports have documented the detection of DNA with cancer-associated changes (mutations, methylation, rearrangements) in the serum of patients; however, its precise origin is unclear. That is, the circulating DNA could come from intact tumor-derived cells found in blood and/or from the tumor itself through releases of DNA into the bloodstream via necrotic or apoptotic pathways (Stroun et al. 2000, 2001; Tsang and Lo 2007). Early reports suggesting that the simple presence or absence of circulating DNA itself, or its concentration, was diagnostic (Stroun et al. 1989; Wu et al. 2002; Sozzi et al. 2003) have been called into question since serum of healthy individuals was also shown to contain circulating DNA in the same concentration range as cancer patients (Boddy et al. 2005, 2006). The cellular origin of this apparently normal circulating DNA is not known.

Recently, several groups have reported the detection of tumor-associated methylation patterns in serum (for review, see Fleischhacker and Schmidt 2007). However, the success rate has varied greatly among the different groups, even using the same biomarker and highly similar detection technologies (Goessl et al. 2000; Jeronimo et al. 2002; Bastian et al. 2005; Fujiwara et al. 2005; Reibenwein et al. 2007; Wang et al. 2007). The reasons behind these observations are not presently clear. Interestingly, recent estimations of the concentrations of tumor-derived DNA in serum, based on the detection of a confirmed tumor-specific mutation, demonstrated that the amount of such circulating DNA is very small (<0.2%) early in disease and, probably, dependent upon the stage of disease (Diehl et al. 2005). While no single point mutation is common to every tumor type, aberrant DNA methylation patterns suggest that detecting disease early through observation of altered methylation patterns may be possible. However, little is known about the methylation pattern landscape of serum DNA in healthy individuals, let alone those with cancer. Lack of such knowledge substantially limits any ability to develop robust methylation-based clinical assays supporting the detection of tumor-derived DNA from serum.

Bisulphite sequencing is considered to be the “gold standard” in cytosine-methylation pattern studies. Clone-based strategies afford molecule-by-molecule and cytosine-by-cytosine pattern resolution (Frommer et al. 1992). However, such strategies are both time and labor consuming. As a consequence, typically, only a few clones are sequenced, allowing a global survey but not much detail or accuracy regarding actual concentration of particularly methylated molecules.

The availability of massively parallel pyrosequencing technologies, such as that from 454 LifeSciences/Roche, allows high-throughput nucleotide sequencing of individual molecules (Margulies et al. 2005; Goldberg et al. 2006; Wicker et al. 2006). The use of such technology, for sequencing bisulphite-mutagenized DNA, eliminates the cloning step and yet delivers a detailed picture of the cytosine-methylation landscape with more reduced labor and time than the conventional clone-based strategy. Since pyrosequencing technologies require pooling samples for efficiency, the experimental design and analysis procedure must be modified to accommodate tracking individual molecules back to individual regions within individual patient samples (Binladen et al. 2007).

In this study, we report the results of an analysis of the DNA-methylation landscape present in just over 700,000 patient-derived DNA fragments from cancer-free breast tissue, infiltrating ductal breast carcinomas, and sera obtained from a collection of 50 patients using a massively parallel bisulphite sequencing strategy. The targeted loci in the investigation were four genomic regions that we have recently identified as aberrantly methylated at high frequency in correlation with breast cancer (J.M. Ordway, M.A. Budiman, Y. Korshunova, R.K. Maloney, J.A. Bedell, R.W. Citek, B. Bacher, S. Peterson, T. Rholfing, J. Hall, et al., in prep.). Knowing the precise nature of the biological signals would undoubtedly facilitate assay development and provide a rational basis of matching an assay platform to the signal to be detected. It would also provide valuable information regarding the epigenetic pattern normally observed in DNA from tissues, and that are presumed to be circulating within the bloodstream.

Results

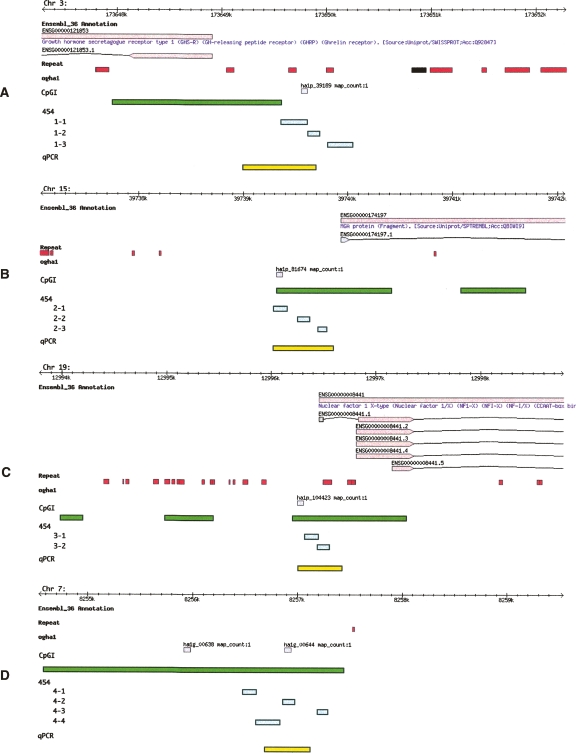

Our group has recently reported the discovery of four DNA methylation biomarkers that can identify cancerous breast-tissue samples with a clinical sensitivity (e.g., true positive rate) up to 90% and a clinical specificity (e.g., true negative rate) of greater than 95% in a study involving more than 230 patient samples (J.M. Ordway, M.A. Budiman, Y. Korshunova, R.K. Maloney, J.A. Bedell, R.W. Citek, B. Bacher, S. Peterson, T. Rholfing, J. Hall, et al., in prep.) and, therefore, were good candidates for development of serum-based tests. The regions of study are denoted in Figure 1, A–D, relative to the NCBIv35/ENSEMBL_36 annotation.

Figure 1.

Location and annotation of genomic loci under study. The figure depicts genomic browser views of four loci: (A) GHSR locus, (B) MGA locus, (C) NF1X locus, and (D) an unannotated region on Chr 7.Within each panel are six data tracks: ENSEMBL_36, Repeat, ogha1, CpGI, 454, and qPCR methylation assay. The black line represents 10 Kb of genomic sequence, tick marks indicate 100-bp intervals. Each chromosome is indicated in the top, left of each panel. Top tan boxes (first data track) show protein-coding genes (according to the ENSEMBL_36) with ENSEMBL GeneIDs, along with recognized gene names (blue text). Arrows point in the direction of transcription. Gene models reflect the exon structure as bottom tan boxes connected by black lines (introns). ENSEMBL transcript IDs are also indicated. Recognized repeats and low-complexity regions are indicated with red boxes (second data track). Gray boxes denote the position of the microarray 60 mer utilized to discover the putative breast cancer biomarkers (Ordway et al. 2007) (third track). Green boxes denote the position of Takai and Jones-predicted CpG Islands in the fourth track. The settings used to map the CpGI were G+C 55, O/E 0.60, and a min length of 200 bp. Within the fifth track, aqua boxes denote the position of the sequencing amplicons used in the 454 experiment. The last track (yellow boxes) indicate the position of the qPCR assay used to establish the methylation status of the biomarkers (Ordway et al. 2007).

Typically, massively parallel pyrosequencing technologies provide the capability to sequence hundreds of thousands of molecules. However, while large numbers of reads are obtained, the read lengths acquired are often much shorter than conventional clone- based technologies (120–250 bp vs. 600–700 bp). In this case, however, these read lengths are ideally suited for the study of serum DNA as it is highly fragmented (Wu et al. 2002). As a consequence of the short read length of pyrosequencing and the DNA fragment size in sera, we subdivided each of our previously characterized genomic loci into a few (two to four) small regions (∼100–200 bp). This locus division allowed us to span the region used in our previously reported limited study of methylation in tissues (Fig. 1; Supplemental Table S1) and provided us with a reference control when sequencing breast tissue-derived molecular libraries. The sole exception was the locus ha1p_39189, where one amplicon was outside of the region used in the previous study (Fig. 1). In large part, this was a consequence of the locally elevated CG-content’s constraint on primer selection.

To allow for sequencing in parallel and mapping the results back to particular patient samples we modified our MethylMapper procedure (Ordway et al. 2005) to incorporate a position-specific BLAST requirement, and assigned sequence tags in association with each sample in a manner similar to that recently published by Binladen et al. (2007). Twenty-three five-base identification tags were synthesized together with the forward locus-specific PCR primers for each amplicon. In this way, we could identify the bisulphate-modified sample from which each particular PCR product was amplified by looking for the sample-specific tag within the first five bases of each processed read.

The locus-specific tag-bearing PCR products were amplified from bisulphate-modified DNA, purified, quantified individually, mixed in equimolar amounts, and sequenced using the 454 pyrosequencing platform. The data were quality controlled by inspecting the reads for balanced representation by patient and by amplicon. The partially modified (i.e., incompletely converted) molecules were identified by incomplete conversion of at least one of cytosine residue outside of CG dinucleotides, and such molecules were removed from further analysis with the MethylMapper data package (Ordway et al. 2005). On average, the representation of a single-patient tag was 4.2% (range 2.69%–6.60%). The expected average was 4.3%. The differences in the observed tag representation were statistically significant, likely, a consequence of technical variation and/or because of tag-based bias. Analysis of the representation of the individual tags in the three independent runs suggested that the differences among the 23 tags could be most easily explained by technical variation across the three runs rather than by a tag-specific bias (data not shown). Bias has been previously described (Binladen et al. 2007). Perhaps this was due to the less-complex nature of the tags used in the previous study (2 bp vs. 5 bp).

Variation in tag representation affects only the number of reads for each sample, lowering the precision of methylation measurements for samples with low numbers of reads. Importantly, such variation should not affect cross-sample comparison so long as the number of reads for each sample is above a certain threshold. For inclusion in this study, the number of reads per sample per amplicon was set to be greater than 100 (Supplemental Table S2), making all occupancy and abundance calculations theoretically precise at or below the 1% level. The sequence quality was controlled by exclusion of reads containing multiple high-scoring BLAST pairs (see Methods section).

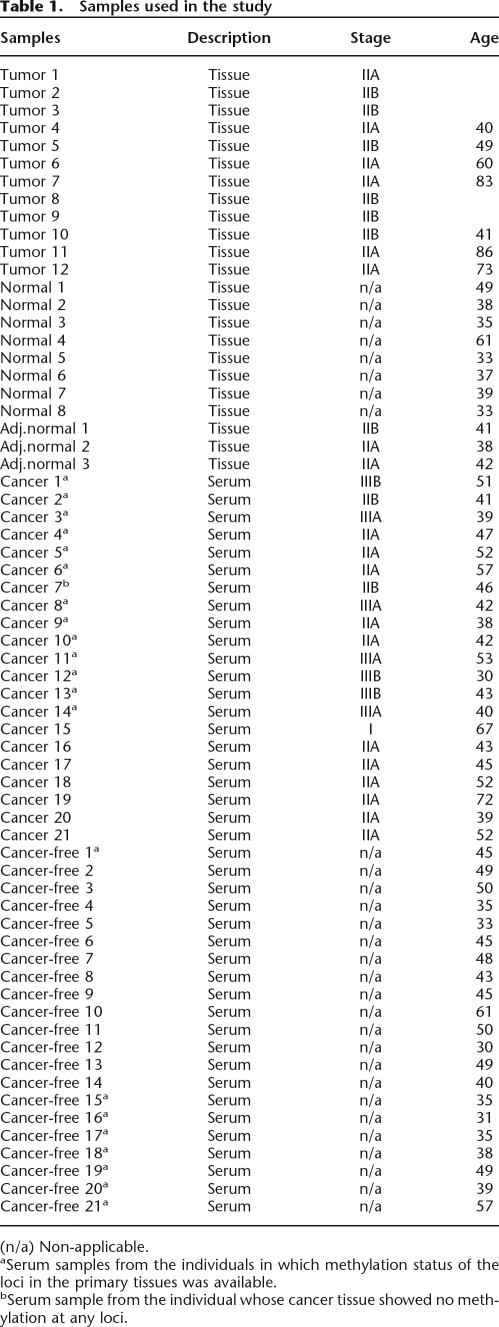

To determine the methylation landscape of DNA derived from diseased and nondiseased breast tissue, we analyzed 12 breast tumors (stage II infiltrating ductal carcinoma) and 11 histologically normal breast tissues including three adjacent normal tissues (Table 1). We also analyzed serum samples from 21 breast-cancer patients (stages I–IIIB) and 21 cancer-free individuals (Table 1). The sera collection contained nine samples, in which the patient’s tumor tissues were confirmed to be positive for at least one of the biomarkers. The age distribution was similar between cancer and cancer-free groups (Table 1) (t = 1.42, P = 0.1637). The methylation status of the loci in the corresponding breast tissues of 21 individuals (nine cancer-free and 12 cancer patients) was determined (Ordway et al. 2007). All nine tissue samples from the cancer-free individuals showed low methylation; however, high methylation in at least two loci was detected in all except one tumor sample from cancer patients. The serum samples were divided into two sets. One set included nine serum samples from cancer-free individuals and 14 serum samples from cancer patients. The second experimental set included seven serum samples from cancer patients and 12 serum samples from cancer-free individuals. Four samples were included in both experimental sets as complete technical replicates (including in vitro bisulphite conversion) to assess the technical reproducibility of the experiment.

Table 1.

Samples used in the study

(n/a) Non-applicable.

aSerum samples from the individuals in which methylation status of the loci in the primary tissues was available.

bSerum sample from the individual whose cancer tissue showed no methylation at any loci.

The quality assessment of the data for each run is presented in Supplemental Tables S3–S5. On average, across the three runs, the depth of coverage per patient amplicon was 880 reads per amplicon per sample. The median depth of coverage was 776 across all three runs. There was no difference in the performance between the serum DNA and tissue DNA as an amplification/sequencing source. The final numbers of reads for each amplicon per patient used in the analysis are in the data in Supplement Table S2.

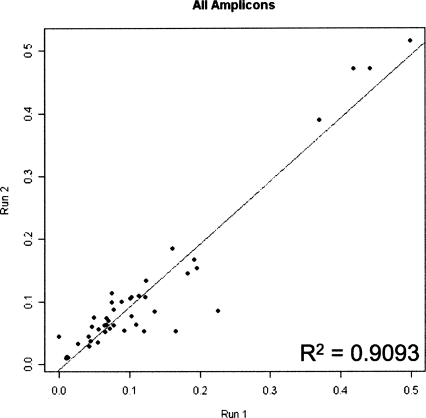

The metric of data quality may be assessed by technical reproducibility. To measure reproducibility, four biological samples (two from cancer patients and two from cancer-free individuals) were bisulphite converted, amplified, and sequenced in two independent experiments. This independently repeated data collection encompassed 44 data points across four samples. A depiction of the analysis is shown in Figure 2 as a scatter plot of average methylation density per sequenced region with the values of each replicate as the axes. The technical reproducibility of the experiment may be qualified as high, since the correlation between the two runs was greater than 95% (R2 = 0.9093). Analysis of each of the four samples individually also showed very high correlation between runs (the range of R2 is 0.86–0.96) with slope close to 1 (0.97–1.08) (data not shown).

Figure 2.

Reproducibility of massively parallel bisulphite-pyrosequencing. A scatter plot depicts 44 data points, representing the average methylation density of the regions in four samples established in two independent experiments. X axis represents the average methylation density determined in experiment 1; Y axis represents the average methylation density determined in experiment 2. The line (y = 1.0071x−0.0096) indicates the linear regression. The fit to the line is displayed by the R2 term. Note that the slope is very close to 1, indicating that data from two experiments are very similar to each other.

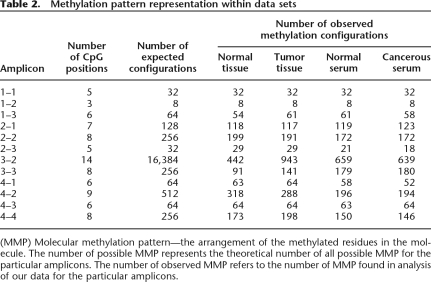

Bisulphite sequence data interpretation may be clouded by bias imposed during sample amplification (Warnecke et al. 1997). Close inspection of the methylation patterns obtained from the replicated samples showed a wide variety of molecular methylation patterns recovered from each run (Table 2). The molecules were analyzed to look for high-frequency recovery of particular methylation patterns. Such events may be the consequence of oversampling (i.e., sequencing the same molecule many times) or amplification bias favoring particular configurations over others. The analysis showed that the frequency of recovery of different configurations was not uniform across samples, but rather sample dependent, with recovery of more methylated configurations including fully methylated molecules to be much more frequent in cancerous samples than in normal. That finding suggests that the low rate of recovery of certain configuration in some samples was a result of the sample’s molecular population rather than an amplification bias. Together, the high technical reproducibility along with the capturing of biological variation suggests that the effect of any amplification-mediated methylation bias in the experiments was minimal.

Table 2.

Methylation pattern representation within data sets

(MMP) Molecular methylation pattern—the arrangement of the methylated residues in the molecule. The number of possible MMP represents the theoretical number of all possible MMP for the particular amplicons. The number of observed MMP refers to the number of MMP found in analysis of our data for the particular amplicons.

The cytosine-methylation topography within the samples was analyzed according to two criteria: the methylation pattern of each molecule and methylation density (or the percent of the methylated residues from the total number of residues sequenced per molecule). The average methylation density of a region is the mean methylation occupancy per CG across a region (i.e., amplicon). Within a region, the average methylation occupancy was calculated for each CG as a percent of the methylated C’s from the total number of molecules sequenced at that position. The average methylation density allows characterization of the methylation level of the molecular population without analyzing prevalence of any molecular configuration. It yields a more general view of the methylation level within samples. On the other hand, a detailed analysis of methylation configurations provides the abundance of particular types of methylation patterns (fully methylated, completely unmethylated, intermediately methylated) within the population. It also allows tracking of changes in abundance of molecules with particular configurations between samples that could be missed if it was the only average methylation density used in the analysis. The goal of the analysis was to identify either a configuration or a regional methylation density where the relative abundance of each may be diagnostic of breast cancer.

The results of the analysis showed a great variety of methylated molecules in all samples, but failed to reveal any special type of methylation pattern that could be found exclusively in cancerous or exclusively in normal tissues. Because no cancer-specific configuration was found in these four loci and to simplify the subsequent analysis, configuration analysis was restricted to fully methylated molecules (FMMs), which were defined as molecules that had all sequenced CG residues within an amplicon methylated. FMMs were chosen for several reasons. First, full methylation includes methylation at all sites that could be biologically relevant as opposed to partially methylated molecules, where one cannot know a priori which methylation sites hold biological importance. Second, tracking full methylation, unlike incomplete methylation, allows the data to be most rapidly translated into a detection test using existing technology like quantitative MSP. Third, the data demonstrated clear differences in the abundance of FMMs between samples. That is, cancer samples tended to have more FMMs than noncancerous samples. Finally, when differences between cancerous and normal samples were considered, usage of FMMs over other configurations afforded the lowest background in the vast majority of normal samples.

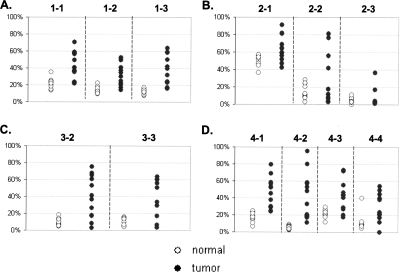

The analysis revealed significant quantitative differences between tumor and normal tissue samples. Within this experimental system, the tumors had significantly higher methylation than normal tissues, as measured both by the average methylation density (Supplemental Table S6; Fig. 3) and by the average frequency of FMMs (Supplemental Table S6; Fig. 4). This finding is significant for two reasons: First, it confirms our previous observations (Ordway et al. 2007), and, second, it demonstrates that this system is capable of detecting methylation differences. Another finding from the tissue study was that in some cases methylation was not evenly distributed across the locus and that neighboring loci/amplicons (not more than 500 bp apart) could exhibit significant differences not only in methylation density, but also in the frequency of observing FMM percent differences between the normal and tumor tissues.

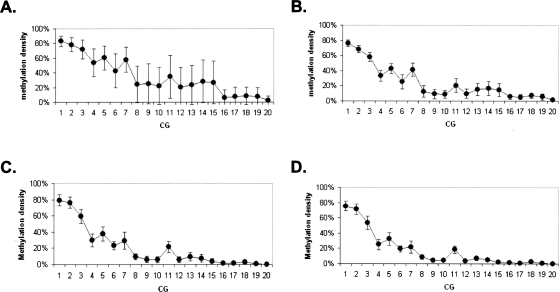

Figure 3.

Methylation density in tissue samples. The plots represent an average methylation density in tissue samples for loci GHSR (A), MGA (B), NFX1 (C), and ha1g_00644 (D). Y axis represents average methylation density. The dashed lines separate data obtained from the different amplicons. The numbers on the top of each plot indicate the amplicons that were used to generate the data beneath. (◦) Normal samples; (●) tumor samples.

Figure 4.

Percent of FMM in tissue samples. The plots represent detection of FMM in tissue samples for loci GHSR (A), MGA (B), NFX1 (C), and ha1g_00644 (D). Y axis represents percent of FMM from total number of sequenced molecules. The dashed lines separate data obtained from the different amplicons. The numbers on the top of each plot indicate the amplicons that were used to generate the data beneath. (◦) Normal samples; (●) tumor samples. Note that scale is 70%.

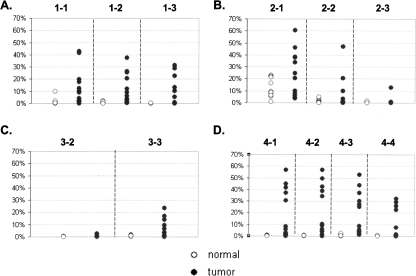

The most illustrative example was that observed within the upstream region of MGA (ha1p_81674, locus 2 amplicons) (Fig. 5). Methylation density of the first subregion (amplicon 2-1) was high; the 49% occupancy was spread across the entire molecular population in normal tissues. However, the density of two neighboring regions (i.e., amplicons 2-2 and 2-3) went down substantially as one moved toward the transcription start site into the adjacent regions (13% and 5% in normal tissues). The FMM frequency of each region within the locus showed a similar trend (Supplemental Table S6). In normal tissues, about 12% of the molecules in region 2-1 were fully methylated, in region 2-2, this number went down to 1.5%, and it was even lower (0.3%) for region 2-3. The same methylation topography was observed in tumors (although average methylation density for each region was higher than normal tissues) as well as in sera of cancer patients and normal individuals (Supplemental Table S7; Figs. 3, 5, 6), suggesting that at this locus the epigenetic topography is largely stable. Structural features of the region, chromatin configurations, or DNA-binding protein interactions could be responsible for the apparent stability of the pattern across patients and DNA sources. Interestingly, the methylation density per site varied much more among tumors than among normal tissues (P < 0.0001), suggesting that the epigenetic pattern of diseased tissues may represent some sort of disruption of the methylation pattern observed in normal tissues as well as in sera of cancer-free individuals and cancer patients (Fig. 7). The absence of substantial variation in the methylation density within sera of cancer patients indicates that this apparent disruption is tissue specific and has no influence on the methylation pattern of sera.

Figure 5.

The stability of methylation pattern of locus MGA in the different samples. The plots show an average methylation density for each CG across the MGA locus in tumor samples (●), normal samples (◦), and serum samples of cancer patients (▴) and of cancer-free individuals (▵). The dashed lines showed the boundary of the amplicons used to generate the data. X axis represents the arbitrary numbers that reflect the sequential positions of particular CG in the locus. Y axis represents an average methylation density.

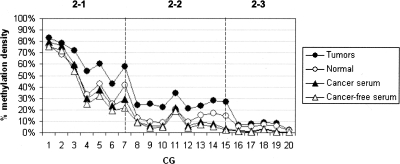

Figure 6.

Methylation density in serum samples The plots represent an average methylation density in tissue samples for loci GHSR (A), MGA (B), NFX1 (C), and ha1g_00644 (D). Y axis represents average methylation density. The dashed lines separate data obtained from the different amplicons. The numbers on the top of each plot indicate the amplicons that were used to generate the data beneath. (◦) Serum samples of cancer-free individuals; (●) serum samples of cancer patients.

Figure 7.

Variation of methylation density among different samples. The plots show an average methylation density for each CG across MGA locus in tumor samples (A), normal samples (B), and serum samples (C) of cancer patients and of cancer-free individuals (D). X axis represents the arbitrary numbers that reflect the sequential positions of particular CG in the locus. Y axis represents an average methylation density. Error bars represent the range of average methylation density among samples.

In general, the level of methylation within an interrogated region could not predict the degree of methylation differences between tumor and normal in these breast tissues. For example, the average methylation density of regions 2-3 and 4-2 was similar in normal tissues (5% and 5.6%, respectively), but although all cancer samples (100%) had higher methylation in the region 4-2 than any normal sample in the set, only two tumor samples (17%) had the higher average methylation in the region 2-3 (Supplemental Table S6). This finding suggests that the arbitrary design and implementation of MSP-based assays, based upon sequence context alone, will be challenging without initially determining where these maximally discriminating subregions are through experimentation.

Of interest was the observation that methylation levels (measured both by percent of FMMs and by average methylation density) varied much more among the tumor samples than among normal samples (Figs. 3, 4). The simplest explanation could be sample heterogeneity (i.e., a varying number of tumor cells in the tumor samples); however, there existed no meaningful correlation between methylation levels and cellularity of the tumor samples as reported by a pathologist (data not shown).

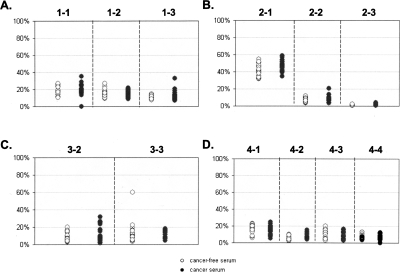

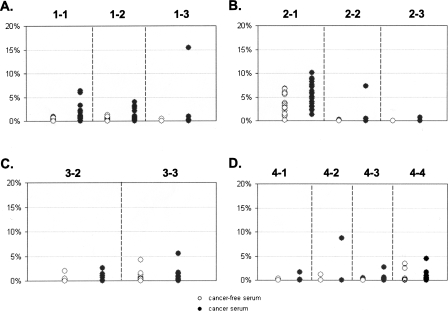

Contrary to the situation that we observed in tissues, the average methylation density was not significantly different between sera of cancer patients and the sera from cancer-free individuals (Supplemental Table S7; Fig. 6). Neither was there an absolute methylation pattern nor levels of FMM that were discriminatory between the two groups (Fig. 8). Both groups were indistinguishable from each other and were most similar to normal tissue. There were quantitative differences in amounts of FMM of some regions, but only subtle ones (Supplemental Table S7; Fig. 8). In general, any (i.e., every possible) methylation pattern could be found in the serum of at least one cancer-free individual. We found only one exception that was the fully methylated region 2-3 (from MGA), which was detected in some tumor samples as well as in the serum of one cancer patient, but not in any serum from the cancer-free individuals. Remarkably, this situation, at the same region, was reversed within the tissue group; that is, the small numbers of FMMs of the same MGA region (2-3) were detected in more than 50% of the normal tissue samples, but in only two of the tumor tissue samples (16%), with only one showing a number of FMMs higher than in any normal tissue sample. The median values of FMM frequency in this region were higher in normal tissues than in tumors, suggesting that merely the presence of such molecules could not be a basis for differentiation of cancer from normal tissues.

Figure 8.

Percent of FMM in serum samples The plots represent detection of FMMs in serum samples for loci GHSR (A), MGA (B), NFX1 (C), and ha1g_00644 (D). Y axis represents percent of FMMs from the total number of sequenced molecules. The dashed lines separate data obtained from the different amplicons. The numbers on the top of each plot indicate the amplicons that were used to generate the data beneath. (◦) Serum samples of cancer-free individuals; (●) represent serum samples of cancer patients. Note that the scale is 20%.

There was no correlation between a region’s ability to distinguish between normal tissues and tumors and its ability to distinguish between the sera of cancer-patients and cancer-free individuals. The most promising amplicon for a tissue test could detect a higher content of FMMs in 92% of tumors; however, the same amplicon detected differences only in 5% of cancer patients’ sera compared with sera from the cancer-free individuals (Supplemental Tables S6, S7). This observation suggests that tumor vs. normal tissue data cannot be broadly extrapolated to serum. Using the average methylation density of a region worked equally well in the separation of tumor from normal tissues, but did not discriminate between the sera of cancer patients and cancer-free individuals. However, using DNA methylation density, univariate analyses on each region did reveal differences between cancer and cancer-free individuals in each experiment. Unfortunately, the differences that were detected were not observed across experiments (data not shown). In addition to the univariate analyses, discriminant analysis was performed. Classification rules derived using a training data set from the first experiment did not validate in a test set of the data from the second experiment (i.e., error rates approaching 50% [data not shown]). Together, these findings suggested that the observed differences were artifacts of the small sample size within each run.

In large part, these observations can be most easily explained by the very small amount of tumor DNA released into the serum, such that neither general methylation density nor FMM abundance could discriminate the patient’s sera. In other words, for these four loci, the small amounts of tumor DNA in the sera of the cancer patients cannot be easily detected as a signal above the complex methylation background of normal cells.

Discussion

Here we have described a high-resolution cytosine-methylation study of tissues and sera from cancer-free individuals and breast-cancer patients using massively parallel bisulphite sequencing. The study afforded a molecule-by-molecule analysis of four genomic loci that have been demonstrated to exhibit breast cancer-associated changes in epigenetic patterns (Ordway et al. 2007).

The ultra-deep sequencing revealed the complex nature of the cytosine-methylation landscape of both serum and tissue DNA by providing a depth of coverage previously unattainable and facilitating views of molecular populations large enough to be substantiated by statistical analyses. At least three main conclusions may be drawn from this study.

First, there are no tumor-specific molecular methylation patterns obtained from any of the four tested loci. Tumors and cancer-free tissues as well as sera of cancer-free individuals contain nearly every conceivable cytosine-methylation pattern. A great variety of methylated molecules were present in all samples, yet no special type of methylation pattern could be found in a statistically meaningful way exclusively in cancerous or exclusively in normal tissues (or serum). At all four tested loci, while there were no tumor-specific molecules, there were tumor-specific loads of methylated molecules. The data may suggest that disease could be associated with the overrepresentation of a normally methylated molecular class, as though disease reflects an inappropriate mixture of cell-types with cell-type appropriate methylation patterns. One of the potential explanations for the presence of FMMs in the sera of cancer-free individuals could be a universal presence of cancer germ cells that are normally destroyed by the immune system of the healthy individuals. Clearly, further study will be required to more formally substantiate any of these hypotheses.

The second important finding of the work is that the levels of methylation vary greatly among tumor samples, but yet, little variation in methylation levels is found in samples considered histologically normal. Finding an increase in methylation-level variation is important mechanistically, because it could suggest that in normal tissues an exclusionary mechanism is surveilling these loci and constraining their variation (i.e., methylation status). Loss of proper DNA-binding elements could passively promote the variance observed in tumors through an increased accessibility of the sequences; such a mechanism might be expected to be somewhat stochastic and promote the variation observed. Equally attractive is the notion that cancer is associated with the loss of an active demethylation activity (glycosylase or otherwise) that could be invoked to support the observation (Szyf et al. 1985; Jost et al. 1995, 2001; Bhattacharya et al. 1999; Penterman et al. 2007). Both would require more study.

The third important observation of this study involves the quantification of the background level of circulating methylated molecules in cancer-free patient sera. According to cancer-specific mutation-based estimations, tumor DNA in serum at early stages of disease is present at a relative abundance of about 12 haploid genomes for every 10,000 somatically normal haploid genomes (0.12%) or less (Diehl et al. 2005). Expected methylation signals from such minute amounts are so close to the level of background (in most cases around several tens of the percent) that robust detection of tumor-shed DNA would seem to be problematic, especially in the case of an epigenetically complex background. The load of fully and densely methylated molecules in the normal serum is comparable to the amount of tumor-derived DNA molecules found to be circulating by the Vogelstein group (Diehl et al. 2005).

Unlike the situation present with circulating mutations, if there are no tumor-specific molecular methylation patterns, disease detection will rely upon an increase of the tumor-derived signal above the normal background. The quantified background is high enough in the case of these loci to obfuscate methylated DNA shed from tumors or circulating tumor cells. The practical implication of this finding suggests that enhancing detection assay sensitivity will not improve the clinical performance of the assays, particularly when one considers that the ability of qPCR to detect is no less than a twofold difference. Our findings suggest that the continued use of PCR-based methods for development of epigenetic serum biomarker assays will remain challenging.

Interestingly, our findings shed some light upon the apparently contradictory results for some biomarkers obtained using MSP serum testing. By examining the methylation pattern of nearly 500,000 patient-sera derived molecules, we observed that, on average, the sera of cancer patients tended to have slightly more fully methylated molecules than the sera of cancer-free patients. Curiously, the median values, however, showed almost no difference, suggesting that differences in the averages are driven by just a few samples rather than by systematic methylation increase in all samples due to cancer. By way of example, in the best-case region, only 33% of sera from cancer patients had more methylated molecules than any of those from cancer-free individuals. This lies in marked contrast to the situation in tissues, where after examining just over 200,000 molecules, we found that in the best-case region (locus ha1g_00644, amplicon 4-2), 90% of tumors had more methylated molecules than any normal tissue. These results are not likely to be explained by low sensitivity of the detection of methylation in serum, but rather by the high background of overall methylation observed in the serum of cancer-free individuals. These observations may explain why in many serum methylation studies, MSP and related techniques typically suffer from specificity issues (i.e., false positives) when using predetermined thresholds. In addition, the complexity of the methylation patterns observed suggests that diagnostic cutoff values for MSP and related assays will likely vary substantially between patient cohorts, making consistent application of the same (or a standardized) cutoff clinically less feasible in serum testing.

Finally, these findings may be broadly applicable to methylation-based assay-development strategy. Because the normal methylation background seems to be an obstacle, one of the approaches could be to find the biomarker(s) that has(ve) no background in normal serum. However, determination of a detailed background for every biomarker will require extensive work; it seems reasonable that rather than attempting to extrapolate the efficacy of tissue markers to serum, it would seem more fruitful to focus future experimental discovery efforts directly upon serum itself. Such efforts would likely allow the identification of the largest possible epigenetic differences between diseased and normal serum and make the subsequent test development effort less burdensome and possibly more effective and efficient by allowing the samples to identify the loci where methylation changes with the largest signal to noise differential.

Methods

Sample collection and DNA preparation

We evaluated 12 breast tumor samples (stages IIA and IIB) and 11 normal breast tissues (see Table 2). DNA from the tissues was purified using the MasterPure DNA Purification kit (Epicentre Technologies). Tissue samples were homogenized using polytron in 1X TC lysis buffer prior to adding proteinase K. DNA was quantified using the NanoDrop ND1000 instrument.

We also evaluated 42 serum samples (see Table 2). DNA from the serum samples was purified with the MasterPure DNA Purification kit according to the manufacturer’s provided protocol. DNA was quantified using the NanoDrop ND3300 instrument.

Preparation of samples for massively parallel bisulphite pyrosequencing

DNA (2 μg of tissue samples and 100 ng of sera samples) was bisulphite converted using the EZ DNA Methylation kit according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Zymo Research). The amplicons were amplified using the nested-primers strategy (sequence of primers and amplification conditions are available upon request). The products were individually purified using PCR plate from QIAGEN, quantified using the NanoDrop ND1000 instrument, and the molecular weight of each amplicon was confirmed using a Bioanalyzer2100. For reactions that demonstrated several DNA amplification products, the product of the correct molecular weight was gel purified.

Effects of DNA input was estimated by performing a clone-based sequencing project, demonstrating that there was no difference in outcome from utilization of 100 ng vs. 2 μg of DNA for bisulphite conversion. The limited clone-based analysis of PCR products of three independent conversions of 100 ng DNA produced similar results among all three conversions (data not shown), suggesting that small amounts of DNA available from serum preps would not skew the results.

After quantification, the PCR products were pooled in three sets (23 samples each): tissue set (12 tumor tissues and 11 normal tissues, including three adjacent normal tissues), serum set 1 (14 samples of cancer patients and nine samples of cancer-free individuals), and serum set 2 (nine samples of cancer patient and 14 samples of cancer-free individuals). In the serum set 2, independent conversions of four samples (two of cancer patients and two of healthy individuals) from serum set 1 were used. The mix of the PCR products was concentrated using a SpeedVac, repurified, and quantified for the emulsion PCR used in 454 technology. Massively parallel pyrosequencing of the pooled amplification products was executed according to the manufacturer’s provided protocol (454 LifeSciences).

MethylMapper data preparation and quality control

The data were analyzed using our previously described method (Ordway et al. 2005) with three main adaptations. First, all reads were analyzed for the presence of the 5-bp patient tag (tag list available upon request) within the first six bases of each read. Reads with indiscernible tags were excluded from further analysis. Second, we seeded our tag identified sequence reads with full-length amplicons as BLAST assembly scaffold subjects, and used the amplicons as the query sequences. Third, the seeded amplicons had their 5′ and 3′ ends modified by a tract of cytosine bases, so that each would not have analytical CG’s fall at position 61 in the m1 BLAST report. The efficacy of the bisulphate mutagenesis was assessed using MethylMapper as described previously (Ordway et al. 2005). Manipulating the E-value cutoff for BLAST participation helped to assess sequence quality and established a cutoff for each run. Finally, a restriction was established that each read must have only one high-scoring BLAST pair to be included in the analysis. The data set was examined to insure that there was balanced representation for each amplicon and each patient within each run.

Statistical analysis of methylation density and configuration

To determine the presence of any particular molecular methylation pattern that may indicate the disease state (cancer/cancer-free) of an individual, logic regression was utilized ((Ruczinski et al. 2003). This entailed using the methylation state at each position of a given amplicon as predictor variables and disease state as the response. Decision rules were formed using logic regression on the data from the first experiment (training set) and were validated with the data from the second experiment (test set).

T-tests were performed on each amplicon (separately for each experiment) to determine whether there were differences in methylation density of cancer and cancer-free individuals. In addition, discriminant analysis (Dudoit et al. 2002) was carried out to reveal combinations of amplicons that might differentiate between cancer and cancer-free individuals. Once again, data from the first experiment was used as a training set and data from the second experiment was used as a test set.

Statistical analyses were carried out using SAS (SAS Institute) and R (R Foundation for Statistical Computing) software.

Competing interests statement

W.R. McCombie, J.D. McPherson, and the authors from Orion Genomics recognize a competing interest in its publication as option and shareholders of Orion Genomics, LLC. This work was entirely privately funded.

Acknowledgments

E. Mardis and colleagues at the Washington University Genome Sequencing Center provided the massively parallel pyrosequencing services. R.K. Wilson and R.A. Martienssen provided critical comments. A. Garrido and C. Tatham provided database, coding, and network support for the analysis. T. Rohlfing provided coordinating logistical and operational support.

Footnotes

[Supplemental material is available online at www.genome.org.]

Article published online before print. Article and publication date are at http://www.genome.org/cgi/doi/10.1101/gr.6883307

References

- Bastian P.J., Palapattu G.S., Lin X., Yegnasubramanian S., Mangold L.A., Trock B., Eisenberger M.A., Partin A.W., Nelson W.G., Palapattu G.S., Lin X., Yegnasubramanian S., Mangold L.A., Trock B., Eisenberger M.A., Partin A.W., Nelson W.G., Lin X., Yegnasubramanian S., Mangold L.A., Trock B., Eisenberger M.A., Partin A.W., Nelson W.G., Yegnasubramanian S., Mangold L.A., Trock B., Eisenberger M.A., Partin A.W., Nelson W.G., Mangold L.A., Trock B., Eisenberger M.A., Partin A.W., Nelson W.G., Trock B., Eisenberger M.A., Partin A.W., Nelson W.G., Eisenberger M.A., Partin A.W., Nelson W.G., Partin A.W., Nelson W.G., Nelson W.G. Preoperative serum DNA GSTP1 CpG island hypermethylation and the risk of early prostate-specific antigen recurrence following radical prostatectomy. Clin. Cancer Res. 2005;11:4037–4043. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-2446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baylin S.B. DNA methylation and gene silencing in cancer. Nat. Clin. Pract. Oncol. 2005;2 Suppl 1:S4–S11. doi: 10.1038/ncponc0354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bestor T.H. The DNA methyltransferases of mammals. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2000;9:2395–2402. doi: 10.1093/hmg/9.16.2395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhattacharya S.K., Ramchandani S., Cervoni N., Szyf M., Ramchandani S., Cervoni N., Szyf M., Cervoni N., Szyf M., Szyf M. A mammalian protein with specific demethylase activity for mCpG DNA. Nature. 1999;397:579–583. doi: 10.1038/17533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Binladen J., Gilbert M.T., Bollback J.P., Panitz F., Bendixen C., Nielsen R., Willerslev E., Gilbert M.T., Bollback J.P., Panitz F., Bendixen C., Nielsen R., Willerslev E., Bollback J.P., Panitz F., Bendixen C., Nielsen R., Willerslev E., Panitz F., Bendixen C., Nielsen R., Willerslev E., Bendixen C., Nielsen R., Willerslev E., Nielsen R., Willerslev E., Willerslev E.2007The use of coded PCR primers enables high-throughput sequencing of multiple homolog amplification products by 454 parallel sequencing PLoS ONE 2e197 . 10.1371/journal.pone.0000197 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boddy J.L., Gal S., Malone P.R., Harris A.L., Wainscoat J.S., Gal S., Malone P.R., Harris A.L., Wainscoat J.S., Malone P.R., Harris A.L., Wainscoat J.S., Harris A.L., Wainscoat J.S., Wainscoat J.S. Prospective study of quantitation of plasma DNA levels in the diagnosis of malignant versus benign prostate disease. Clin. Cancer Res. 2005;11:1394–1399. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-1237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boddy J.L., Gal S., Malone P.R., Shaida N., Wainscoat J.S., Harris A.L., Gal S., Malone P.R., Shaida N., Wainscoat J.S., Harris A.L., Malone P.R., Shaida N., Wainscoat J.S., Harris A.L., Shaida N., Wainscoat J.S., Harris A.L., Wainscoat J.S., Harris A.L., Harris A.L. The role of cell-free DNA size distribution in the management of prostate cancer. Oncol. Res. 2006;16:35–41. doi: 10.3727/000000006783981297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diehl F., Li M., Dressman D., He Y., Shen D., Szabo S., Diaz L.A., Goodman S.N., David K.A., Juhl H., Li M., Dressman D., He Y., Shen D., Szabo S., Diaz L.A., Goodman S.N., David K.A., Juhl H., Dressman D., He Y., Shen D., Szabo S., Diaz L.A., Goodman S.N., David K.A., Juhl H., He Y., Shen D., Szabo S., Diaz L.A., Goodman S.N., David K.A., Juhl H., Shen D., Szabo S., Diaz L.A., Goodman S.N., David K.A., Juhl H., Szabo S., Diaz L.A., Goodman S.N., David K.A., Juhl H., Diaz L.A., Goodman S.N., David K.A., Juhl H., Goodman S.N., David K.A., Juhl H., David K.A., Juhl H., Juhl H., et al. Detection and quantification of mutations in the plasma of patients with colorectal tumors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2005;102:16368–16373. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0507904102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ducasse M., Brown M.A., Brown M.A. Epigenetic aberrations and cancer. Mol. Cancer. 2006;5:60. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-5-60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dudoit S., Fridlyand J., Speed T., Fridlyand J., Speed T., Speed T. Comparison of discrimination methods for the classification of tumors using gene expression data. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 2002;97:77–87. [Google Scholar]

- Feinberg A.P., Ohlsson R., Henikoff S., Ohlsson R., Henikoff S., Henikoff S. The epigenetic progenitor origin of human cancer. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2006;7:21–33. doi: 10.1038/nrg1748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleischhacker M., Schmidt B., Schmidt B. Circulating nucleic acids (CNAs) and cancer–a survey. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2007;1775:181–232. doi: 10.1016/j.bbcan.2006.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frommer M., McDonald L.E., Millar D.S., Collis C.M., Watt F., Grigg G.W., Molloy P.L., Paul C.L., McDonald L.E., Millar D.S., Collis C.M., Watt F., Grigg G.W., Molloy P.L., Paul C.L., Millar D.S., Collis C.M., Watt F., Grigg G.W., Molloy P.L., Paul C.L., Collis C.M., Watt F., Grigg G.W., Molloy P.L., Paul C.L., Watt F., Grigg G.W., Molloy P.L., Paul C.L., Grigg G.W., Molloy P.L., Paul C.L., Molloy P.L., Paul C.L., Paul C.L. A genomic sequencing protocol that yields a positive display of 5-methylcytosine residues in individual DNA strands. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 1992;89:1827–1831. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.5.1827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujiwara K., Fujimoto N., Tabata M., Nishii K., Matsuo K., Hotta K., Kozuki T., Aoe M., Kiura K., Ueoka H., Fujimoto N., Tabata M., Nishii K., Matsuo K., Hotta K., Kozuki T., Aoe M., Kiura K., Ueoka H., Tabata M., Nishii K., Matsuo K., Hotta K., Kozuki T., Aoe M., Kiura K., Ueoka H., Nishii K., Matsuo K., Hotta K., Kozuki T., Aoe M., Kiura K., Ueoka H., Matsuo K., Hotta K., Kozuki T., Aoe M., Kiura K., Ueoka H., Hotta K., Kozuki T., Aoe M., Kiura K., Ueoka H., Kozuki T., Aoe M., Kiura K., Ueoka H., Aoe M., Kiura K., Ueoka H., Kiura K., Ueoka H., Ueoka H., et al. Identification of epigenetic aberrant promoter methylation in serum DNA is useful for early detection of lung cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2005;11:1219–1225. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goessl C., Krause H., Muller M., Heicappell R., Schrader M., Sachsinger J., Miller K., Krause H., Muller M., Heicappell R., Schrader M., Sachsinger J., Miller K., Muller M., Heicappell R., Schrader M., Sachsinger J., Miller K., Heicappell R., Schrader M., Sachsinger J., Miller K., Schrader M., Sachsinger J., Miller K., Sachsinger J., Miller K., Miller K. Fluorescent methylation-specific polymerase chain reaction for DNA-based detection of prostate cancer in bodily fluids. Cancer Res. 2000;60:5941–5945. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg S.M., Johnson J., Busam D., Feldblyum T., Ferriera S., Friedman R., Halpern A., Khouri H., Kravitz S.A., Lauro F.M., Johnson J., Busam D., Feldblyum T., Ferriera S., Friedman R., Halpern A., Khouri H., Kravitz S.A., Lauro F.M., Busam D., Feldblyum T., Ferriera S., Friedman R., Halpern A., Khouri H., Kravitz S.A., Lauro F.M., Feldblyum T., Ferriera S., Friedman R., Halpern A., Khouri H., Kravitz S.A., Lauro F.M., Ferriera S., Friedman R., Halpern A., Khouri H., Kravitz S.A., Lauro F.M., Friedman R., Halpern A., Khouri H., Kravitz S.A., Lauro F.M., Halpern A., Khouri H., Kravitz S.A., Lauro F.M., Khouri H., Kravitz S.A., Lauro F.M., Kravitz S.A., Lauro F.M., Lauro F.M., et al. A Sanger/pyrosequencing hybrid approach for the generation of high-quality draft assemblies of marine microbial genomes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2006;103:11240–11245. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0604351103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herman J.G., Jen J., Merlo A., Baylin S.B., Jen J., Merlo A., Baylin S.B., Merlo A., Baylin S.B., Baylin S.B. Hypermethylation-associated inactivation indicates a tumor suppressor role for p15INK4B. Cancer Res. 1996;56:722–727. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeronimo C., Usadel H., Henrique R., Silva C., Oliveira J., Lopes C., Sidransky D., Usadel H., Henrique R., Silva C., Oliveira J., Lopes C., Sidransky D., Henrique R., Silva C., Oliveira J., Lopes C., Sidransky D., Silva C., Oliveira J., Lopes C., Sidransky D., Oliveira J., Lopes C., Sidransky D., Lopes C., Sidransky D., Sidransky D. Quantitative GSTP1 hypermethylation in bodily fluids of patients with prostate cancer. Urology. 2002;60:1131–1135. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(02)01949-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jost J.P., Siegmann M., Sun L., Leung R., Siegmann M., Sun L., Leung R., Sun L., Leung R., Leung R. Mechanisms of DNA demethylation in chicken embryos. Purification and properties of a 5-methylcytosine-DNA glycosylase. J. Biol. Chem. 1995;270:9734–9739. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.17.9734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jost J.P., Oakeley E.J., Zhu B., Benjamin D., Thiry S., Siegmann M., Jost Y.C., Oakeley E.J., Zhu B., Benjamin D., Thiry S., Siegmann M., Jost Y.C., Zhu B., Benjamin D., Thiry S., Siegmann M., Jost Y.C., Benjamin D., Thiry S., Siegmann M., Jost Y.C., Thiry S., Siegmann M., Jost Y.C., Siegmann M., Jost Y.C., Jost Y.C. 5-Methylcytosine DNA glycosylase participates in the genome-wide loss of DNA methylation occurring during mouse myoblast differentiation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001;29:4452–4461. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.21.4452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laird P.W. Cancer epigenetics. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2005;14 Spec No 1:R65–R76. doi: 10.11093/hmg/ddi113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lund A.H., van Lohuizen M., van Lohuizen M. Epigenetics and cancer. Genes & Dev. 2004;18:2315–2335. doi: 10.1101/gad.1232504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Margulies M., Egholm M., Altman W.E., Attiya S., Bader J.S., Bemben L.A., Berka J., Braverman M.S., Chen Y.J., Chen Z., Egholm M., Altman W.E., Attiya S., Bader J.S., Bemben L.A., Berka J., Braverman M.S., Chen Y.J., Chen Z., Altman W.E., Attiya S., Bader J.S., Bemben L.A., Berka J., Braverman M.S., Chen Y.J., Chen Z., Attiya S., Bader J.S., Bemben L.A., Berka J., Braverman M.S., Chen Y.J., Chen Z., Bader J.S., Bemben L.A., Berka J., Braverman M.S., Chen Y.J., Chen Z., Bemben L.A., Berka J., Braverman M.S., Chen Y.J., Chen Z., Berka J., Braverman M.S., Chen Y.J., Chen Z., Braverman M.S., Chen Y.J., Chen Z., Chen Y.J., Chen Z., Chen Z., et al. Genome sequencing in microfabricated high-density picolitre reactors. Nature. 2005;437:376–380. doi: 10.1038/nature03959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ordway J.M., Bedell J.A., Citek R.W., Nunberg A.N., Jeddeloh J.A., Bedell J.A., Citek R.W., Nunberg A.N., Jeddeloh J.A., Citek R.W., Nunberg A.N., Jeddeloh J.A., Nunberg A.N., Jeddeloh J.A., Jeddeloh J.A. MethylMapper: A method for high-throughput, multilocus bisulfite sequence analysis and reporting. Biotechniques. 2005;39:464–, 466, 468 passim. doi: 10.2144/000112035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ordway J.M., Budiman M.A., Korshunova Y., Maloney R.K., Bedell J.A., Citek R.W., Bacher B., Peterson S., Rholfing T., Hall J., Budiman M.A., Korshunova Y., Maloney R.K., Bedell J.A., Citek R.W., Bacher B., Peterson S., Rholfing T., Hall J., Korshunova Y., Maloney R.K., Bedell J.A., Citek R.W., Bacher B., Peterson S., Rholfing T., Hall J., Maloney R.K., Bedell J.A., Citek R.W., Bacher B., Peterson S., Rholfing T., Hall J., Bedell J.A., Citek R.W., Bacher B., Peterson S., Rholfing T., Hall J., Citek R.W., Bacher B., Peterson S., Rholfing T., Hall J., Bacher B., Peterson S., Rholfing T., Hall J., Peterson S., Rholfing T., Hall J., Rholfing T., Hall J., Hall J., et al. Identification of novel high-frequency DNA methylation changes in breast cancer. PLoS One. 2007 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001314. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paluszczak J., Baer-Dubowska W., Baer-Dubowska W. Epigenetic diagnostics of cancer–the application of DNA methylation markers. J. Appl. Genet. 2006;47:365–375. doi: 10.1007/BF03194647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penterman J., Zilberman D., Huh J.H., Ballinger T., Henikoff S., Fischer R.L., Zilberman D., Huh J.H., Ballinger T., Henikoff S., Fischer R.L., Huh J.H., Ballinger T., Henikoff S., Fischer R.L., Ballinger T., Henikoff S., Fischer R.L., Henikoff S., Fischer R.L., Fischer R.L. DNA demethylation in the Arabidopsis genome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2007;104:6752–6757. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0701861104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reibenwein J., Pils D., Horak P., Tomicek B., Goldner G., Worel N., Elandt K., Krainer M., Pils D., Horak P., Tomicek B., Goldner G., Worel N., Elandt K., Krainer M., Horak P., Tomicek B., Goldner G., Worel N., Elandt K., Krainer M., Tomicek B., Goldner G., Worel N., Elandt K., Krainer M., Goldner G., Worel N., Elandt K., Krainer M., Worel N., Elandt K., Krainer M., Elandt K., Krainer M., Krainer M. Promoter hypermethylation of GSTP1, AR, and 14-3-3σ in serum of prostate cancer patients and its clinical relevance. Prostate. 2007;67:427–432. doi: 10.1002/pros.20533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruczinski I., Kooperberg C., Leblanc M.L., Kooperberg C., Leblanc M.L., Leblanc M.L. Logic regression. J. Comput. Graph. Stat. 2003;12:475–511. [Google Scholar]

- Sozzi G., Conte D., Leon M., Ciricione R., Roz L., Ratcliffe C., Roz E., Cirenei N., Bellomi M., Pelosi G., Conte D., Leon M., Ciricione R., Roz L., Ratcliffe C., Roz E., Cirenei N., Bellomi M., Pelosi G., Leon M., Ciricione R., Roz L., Ratcliffe C., Roz E., Cirenei N., Bellomi M., Pelosi G., Ciricione R., Roz L., Ratcliffe C., Roz E., Cirenei N., Bellomi M., Pelosi G., Roz L., Ratcliffe C., Roz E., Cirenei N., Bellomi M., Pelosi G., Ratcliffe C., Roz E., Cirenei N., Bellomi M., Pelosi G., Roz E., Cirenei N., Bellomi M., Pelosi G., Cirenei N., Bellomi M., Pelosi G., Bellomi M., Pelosi G., Pelosi G., et al. Quantification of free circulating DNA as a diagnostic marker in lung cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2003;21:3902–3908. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stroun M., Anker P., Maurice P., Lyautey J., Lederrey C., Beljanski M., Anker P., Maurice P., Lyautey J., Lederrey C., Beljanski M., Maurice P., Lyautey J., Lederrey C., Beljanski M., Lyautey J., Lederrey C., Beljanski M., Lederrey C., Beljanski M., Beljanski M. Neoplastic characteristics of the DNA found in the plasma of cancer patients. Oncology. 1989;46:318–322. doi: 10.1159/000226740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stroun M., Maurice P., Vasioukhin V., Lyautey J., Lederrey C., Lefort F., Rossier A., Chen X.Q., Anker P., Maurice P., Vasioukhin V., Lyautey J., Lederrey C., Lefort F., Rossier A., Chen X.Q., Anker P., Vasioukhin V., Lyautey J., Lederrey C., Lefort F., Rossier A., Chen X.Q., Anker P., Lyautey J., Lederrey C., Lefort F., Rossier A., Chen X.Q., Anker P., Lederrey C., Lefort F., Rossier A., Chen X.Q., Anker P., Lefort F., Rossier A., Chen X.Q., Anker P., Rossier A., Chen X.Q., Anker P., Chen X.Q., Anker P., Anker P. The origin and mechanism of circulating DNA. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2000;906:161–168. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2000.tb06608.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stroun M., Lyautey J., Lederrey C., Olson-Sand A., Anker P., Lyautey J., Lederrey C., Olson-Sand A., Anker P., Lederrey C., Olson-Sand A., Anker P., Olson-Sand A., Anker P., Anker P. About the possible origin and mechanism of circulating DNA apoptosis and active DNA release. Clin. Chim. Acta. 2001;313:139–142. doi: 10.1016/s0009-8981(01)00665-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szyf M., Eliasson L., Mann V., Klein G., Razin A., Eliasson L., Mann V., Klein G., Razin A., Mann V., Klein G., Razin A., Klein G., Razin A., Razin A. Cellular and viral DNA hypomethylation associated with induction of Epstein-Barr virus lytic cycle. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 1985;82:8090–8094. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.23.8090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsang J.C., Lo Y.M., Lo Y.M. Circulating nucleic acids in plasma/serum. Pathology. 2007;39:197–207. doi: 10.1080/00313020701230831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y., Yu Z., Wang T., Zhang J., Hong L., Chen L., Yu Z., Wang T., Zhang J., Hong L., Chen L., Wang T., Zhang J., Hong L., Chen L., Zhang J., Hong L., Chen L., Hong L., Chen L., Chen L. Identification of epigenetic aberrant promoter methylation of RASSF1A in serum DNA and its clinicopathological significance in lung cancer. Lung Cancer. 2007;56:289–294. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2006.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warnecke P.M., Stirzaker C., Melki J.R., Millar D.S., Paul C.L., Clark S.J., Stirzaker C., Melki J.R., Millar D.S., Paul C.L., Clark S.J., Melki J.R., Millar D.S., Paul C.L., Clark S.J., Millar D.S., Paul C.L., Clark S.J., Paul C.L., Clark S.J., Clark S.J. Detection and measurement of PCR bias in quantitative methylation analysis of bisulphite-treated DNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:4422–4426. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.21.4422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wicker T., Schlagenhauf E., Graner A., Close T.J., Keller B., Stein N., Schlagenhauf E., Graner A., Close T.J., Keller B., Stein N., Graner A., Close T.J., Keller B., Stein N., Close T.J., Keller B., Stein N., Keller B., Stein N., Stein N. 454 sequencing put to the test using the complex genome of barley. BMC Genomics. 2006;7:275. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-7-275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu T.L., Zhang D., Chia J.H., Tsao K.H., Sun C.F., Wu J.T., Zhang D., Chia J.H., Tsao K.H., Sun C.F., Wu J.T., Chia J.H., Tsao K.H., Sun C.F., Wu J.T., Tsao K.H., Sun C.F., Wu J.T., Sun C.F., Wu J.T., Wu J.T. Cell-free DNA: Measurement in various carcinomas and establishment of normal reference range. Clin. Chim. Acta. 2002;321:77–87. doi: 10.1016/s0009-8981(02)00091-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]