Abstract

Heat shock protein (Hsp) 70B′ is a human Hsp70 chaperone that is strictly inducible, having little or no basal expression levels in most cells. Using siRNAs to knockdown Hsp70B′ and Hsp72 in HT-29, SW-480, and CRL-1807 human colon cell lines, we have found that the two are regulated coordinately in response to stress. We also have found that proteasome inhibition is a potent activator of hsp70B′. Flow cytometry was used to assay hsp70B′ promoter activity in HT-29eGFP cells in this study. Knockdown of both Hsp70B′ and Hsp72 sensitized cells to heat stress and increasing concentrations of proteasome inhibitor. These data support the conclusion that Hsp72 is the primary Hsp70 family responder to increasing levels of proteotoxic stress, and Hsp70B′ is a secondary responder. Interestingly ZnSO4 induces Hsp70B′ and not Hsp72 in CRL-1807 cells, suggesting a stressor-specific primary role for Hsp70B′. Both Hsp70B′ and Hsp72 are important for maintaining viability under conditions that increase the accumulation of damaged proteins in HT-29 cells. These findings are likely to be important in pathological conditions in which Hsp70B′ contributes to cell survival.

INTRODUCTION

The highly conserved heat shock protein (Hsp) 70 family of proteins is a group of chaperones involved in protein folding, stabilization, and shuttling functions throughout the cell. Members of this protein family can be induced by various cellular stresses, including sublethal heat stress, radiation, heavy metals, ischemia, nitric oxide radicals, certain chemotherapeutics, and other stimuli that are able to activate heat shock transcription factors. The human Hsp70 gene family has a complex evolutionary history shaped by multiple gene duplications, divergence, and deletion. Analysis of the protein sequences of Hsp70 family members across a wide range of organisms including mammals indicates that over 75% of the sequence has been conserved throughout evolution (Rensing and Maier 1994). Despite this relatively high evolutionary conservation, many Hsp70 isoforms are species or cell/tissue-type specific (Allen et al 1988; White et al 1994; Gutierrez and Guerriero 1995; Norris et al 1995; Tavaria et al 1996; Manzerra et al 1997; Place and Hofmann 2005). Variations in thermal tolerance is most likely the result of species-specific differences in the presence of heat-inducible Hsp70s, as has been noted in vertebrates (Yamashita et al 2004). Within species, Hsp70 isoforms differ in correlation with thermotolerance (Hightower et al 1999).

The human Hsp70 family contains 11 distinct genes located on several chromosomes, including both constitutive and inducible isoforms. The major inducible isoform retains the nomenclature Hsp70/Hsp72 and is the product of the HspA1A gene. In humans, damaged and unfolded proteins generated by heat stress are refolded with the help of Hsp72. Proteasome inhibitors like MG132, which decrease protein degradation, increase levels of Hsp72 both by increasing accumulation of damaged proteins and activating heat shock transcription factor 1 (Hsf-1) mediated transcription. Hsp72 plays a role in inhibition of apoptosis and, through its chaperoning activity and regulation of cell signaling pathways, the Hsp70 protein family plays a critical role in cell survival.

hsp70B′ is another inducible Hsp70 gene at least partially conserved in the mammalian lineage, with homologs identified in Saguinus oedipus (cotton-top tamarin), Sus scrofa (pig), Bos taurus (cow), and Homo sapiens (human). To date, knowledge about Hsp70B′ is limited. Unlike Hsp72, Hsp70B′ is strictly inducible, having no detectable basal level of expression in most cells (Leung et al 1990; Parsian et al 2000). Interestingly, homologs for the Hsp70B′ gene (HSP6A) are not found in rodents (Parsian et al 2000). Studies of the relationship of Hsp70B′ to other members of the human Hsp70 family may reveal the specific functional role of this protein in the identified organisms.

With the availability of new sequence data and immunological reagents, it is also now practical to assay Hsp72 and Hsp70B′ separately. Previously we reported differences in the activation profiles, both temporally and under cell number–dependent conditions, between hsp70B′ and hsp72 in human colon carcinoma cell lines (Noonan et al 2007). In the present study, we used siRNA technology to examine further the specific role of Hsp70B′ in both human colon carcinoma cells and nontransformed colonocytes. We also report that the function of recently evolved Hsp70B′ overlaps with Hsp72 but also has several distinctive features in the cellular stress response.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell culture and treatments

HT-29 and SW-480 human colon carcinoma cell lines as well as CRL-1807 nontransformed human colonocytes were purchased from the American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA, USA). HT-29 and SW-480 cells were cultivated in McCoys Modified 5A media and CRL-1807 cells were cultivated in Dulbecco modified Eagle Media. Culture media for all cells lines were supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 0.1mM nonessential amino acids, 50 U/ml streptomycin, 50 U/ml penicillin, and 1.0 μg/ml amphotericin B. Cultures were maintained at 37°C in a humidified, 5% CO2 atmosphere. Cells were counted using an American Optical Bright-Line Hemacytometer. Cell number was number of cells/9.62 cm2, the surface area of a 35-mm plate. All cultures were standardized under moderately low cell number conditions at 1e5–5e5 cells/9.62 cm2. Cells were treated with 10 μM, 20 μM, 30 μM, and 60 μM MG-132, 0.17μM geldenamycin (GD), 100 μM 5-fluorouracil (5-FU), 10 μM 5-aza-2′-deoxycytidine (5-Aza), 300 μM zinc (ZnSO4), and 4 mM butyrate (BA). Standard heat shock conditions were 42.5°C for 1 hour unless specified.

siRNA transfection

Cultures were harvested with trypsin ethylenediamine-tetraacetic acid (EDTA) solution, resuspended in serum-free media (OptiMEM, Gibco Life Technologies, Gaithersburg, MD, USA) in place of serum-supplemented media, and added to a 24-well plate, followed by incubation at 37°C no longer than 30 minutes before transfection. All siRNA assays included using a protocol in which transfection was performed at the same time as cell passage. Cells were plated at a confluency of 25–30%. To reach a working concentration of 100 nM, 0.05 nmol of siRNA was incubated with 2.1μL DharmaFECT 4 transfection reagent in 100 μL optiMEM at 25°C for 20 minutes and then added directly to cell cultures. Cultures then were incubated for 5–6 hours at 37°C, after which the media was replaced with fresh serum-supplemented media. Subsequent experiments were performed at 36–48 hours following siRNA transfections.

DNA constructs, transfection, clonal cell line isolation

A 690-bp DNA fragment was amplified by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) using HT-29 cell genomic DNA as template. Of the reported Hsp70 family promoter sequences in the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) database, our promoter most closely matches the HspA6 promoter sequence, which regulates expression of the Hsp70B′ protein. The promoter from HT-29 cells includes all the promoter elements found in the NCBI sequence at approximately the same positions and spacing relative to the transcriptional start site (Noonan et al 2007). Following sequence analysis, both hsp70B′ promoter and an hsp70A promoter used for comparison were inserted into luciferase reporter vectors (pGL3-Basic vector catalog E1751, Promega, Madison, WI, USA). The hsp70A promoter was a gift from Dr. Richard Morimoto. The hsp70B′ promoter then was inserted into a promoterless pEGFP expression vector (pEGFP-1, catalog 6086-1, Clontech, Palo Alto, CA, USA) and introduced into HT-29 and SW-480 cells using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). Using a 24-well plate format, 0.8 μg of plasmid DNA was incubated with 3 μL Lipofectamine 2000 in 100 μL of Optimem (Gibco Life Technologies) for 20 minutes at 25°C and added directly to cell cultures. Serum-free media was used in place of serum-supplemented media and exchanged prior to addition of transfection mixture. Cells then were incubated for 4 hours at 37°C, after which the media was replaced with fresh serum-supplemented media. An additional CMV promoter driven pEGFP expression vector was constructed and introduced into cells in the same manner to serve as a control. Stably transformed cell lines were obtained using G418 selection (500 μg/mL for 10 days) until no viable untransfected cultures remained. Clonal populations from these cells lines were obtained by isolated small colony selection using a cloning cylinder.

Control and heat shocked HT-29eGFP cultures analyzed by flow cytometry

Preliminary experiments were conducted to ensure the practicality of measuring hsp70B′ promoter activation using the HT-29eGFP cells by flow cytometry. Control cultures (1.88e5 cells/9.62 cm2) were maintained at 37°C and experimental cultures (1.75e5 cells/9.62 cm2) were heat shocked at 42.5°C for 1 hour and returned to 37°C for about 24 hours. Cells were harvested with trypsin-EDTA solution, resuspended in phosphate-buffered saline, and eGFP fluorescence was measured by flow cytometry using a FACSCalibur flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA).

A “gate” was drawn around the data points in the scatter plot expected to be intact cells to eliminate cell fragments and small particles. The M1 marker range was defined as fluorescence in the nonstressed cell population. Data based on the gated cell population showed that the control cells had most of their fluorescence in the M1 marker range (M1 = 0–10, log scale) and only a very small percentage of cells had fluorescence in the M2 marker range (M2 > 10, log scale) where eGFP fluoresces. In contrast, a high percentage of the cells in heat shocked cultures had M2 fluorescence due to activation of the hsp70B′ promoter and production of eGFP. For subsequent assays, both the % of cells induced in a population and the mean fluorescence of the induced cells were determined. Statistical analysis was performed using a paired Student's t-test.

Cell counting assay for viability

HT-29 and CRL-1807 cells were transfected with siRNAs specific to Hsp70B′, Hsp72, a combination of the two, or a nonspecific control on a 24-well plate format. Cultures were subjected to a standard heat shock or treated with increasing concentrations of MG-132 (as noted above) for 24 hours. Cultures then were passed and allowed to recover for 24 hours at 37°C. Remaining attached cells were considered to be viable because they are proliferative cells, and they were counted using flow cytometry. Cells were harvested with trypsin-EDTA solution and resuspended in equivalent 500-μL volumes of phosphate-buffered saline/10% FBS, the FACSCalibur flow rate was set on high (60 μL/minute), and samples were counted for 6 minutes and resuspended every 2 minutes to minimize settling within the sample tube. A gate was drawn around the data points in the scatter plot of intact cells (based on size) to eliminate cell fragments and small particles. Cells counts from each of the specific RNAi transfections then were compared to the nonspecific control group to determine the relative level of viability. Three independent experiments were performed, and statistical significance was determined using a paired Student's t-test.

Protein extraction

Cytosolic and nuclear extracts were prepared from HT-29 and SW-480 and CRL-1807 cells using the same protocol. Adherent cells growing on 35-mm plates were washed twice with cold PBS. Cells were incubated at 4°C for 10 minutes in 250 μL lysis buffer with 0.1% NP-40 (10 mM HEPES-KOH, pH 7.9 10 mM KCl, 0.1 mM EDTA, 2 mM MgCl2, 0.5 M sucrose, 1 mM DTT, 0.5 mM phenylmethylsulphonylfluoride [PMSF], and 2 μg/mL leupeptin). Cells then were removed by scraping and centrifuged (15 000 × g) at 4°C for 10 minutes. The resulting supernatant was used as cytosolic extract. The remaining pellet was washed with 100 μL of the above buffer without NP-40, resuspended in 30 μL buffer (20 mM HEPES-KOH, pH 7.9, 420 mM NaCl, 0.2 mM EDTA, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 5% glycerol, 1 mM DTT, 0.5 PMSF, and 2 μg/ml leupeptin), and incubated on ice for 40 minutes. The suspension then was centrifuged (15 000 × g) at 4°C for 10 minutes, and the resulting supernatant was used as nuclear extract. Protein concentrations for samples were determined using the Bio-Rad Protein Assay (Bio Rad, Hercules, CA, USA).

Immunoblotting

For Western blot analysis, 10 μg of cytosolic or nuclear extract (quantified using the Bio-Rad protein assay) was denatured under reducing conditions, separated on 7.5– 10% sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gels, and transferred to nitrocellulose by voltage gradient transfer. Blots were blocked with 5% nonfat dry milk and washed twice with 1.0% PBS:0.1% Tween buffer. Antibodies used in detection were anti-Hsp70B′ (1:500), anti-Hsp72 (1: 1000), and anti-Hsp27 (1:1000; SPA-754, SPA-810 and SPA-800, respectively, [Stressgen Bioreagents, Ann Arbor, MI, USA]). The anti-Hsp70B′ monoclonal antibody is specific for the human Hsp70B′ protein, present only under stressed conditions, and does not crossreact with the other known inducible (Hsp72) or the constitutive (Hsc70/ Hsp73) Hsp70 family members. Detection of Actin using anti-Actin goat polyclonal (I-19, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, USA) was used as a protein loading control. Complementary HRP-labeled secondary Abs (Sigma, St Louis, MO, USA) were used for protein detection by enhanced chemiluminescence. Recombinant Hsp70B′ purified protein (SPP-756, Stressgen Bioreagents) was used as a detection control.

RESULTS

Expression of Hsp70B′ following exposure to various chemotherapeutic agents

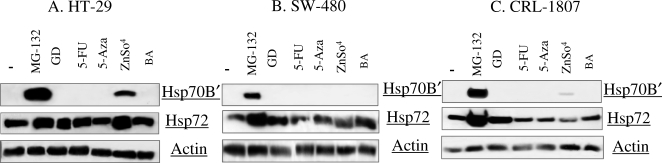

Immunoblots comparing the cytosolic levels of Hsp70B′ in HT-29, SW-480, and CRL-1807 cells following treatment with various cytotoxic agents are shown in Figure 1A–C. Hsp70B′ expression was undetectable in all unstressed cultures (untreated), whereas Hsp72 was abundant in all 3 cell lines. Hsp70B′ was readily detectable in cultures treated with proteasome inhibitor MG-132 for all 3 cell lines. MG-132 also increased levels of Hsp72 in all 3 cell lines. ZnSO4 is a potent inducer of Hsp72 in many cell types and activates expression of Hsp70B′ in the HT-29 and CRL-1807 cell lines (Fig 1A,C), but not in the SW-480 cell line (Fig 1B). Hsp72 levels increase in response to ZnSO4 only in the HT-29 cell line (Fig 1A). GD, BA, 5-FU, and 5-Aza did not promote the expression of Hsp70B′ in these 3 cell lines. GD mildly induced Hsp72 in all 3 cell lines, and 5-FU had a similar mild induction in the HT-29 cell line (Fig 1A). BA induced a small amount of Hsp72 in SW-480 cells only, and 5-Aza did not cause induction of Hsp72 in any of these three cell lines. The accumulation of proteasome substrate proteins therefore is a potent and consistent activator of Hsp70B′ in colon cancer cells.

Fig 1.

Western blot analysis of heat shock protein (Hsp) 70B′ and Hsp72 expression following exposure to various chemotherapeutic agents. Cytosolic extracts were prepared from (A) HT-29 cells, (B) SW-480 cells, and (C) CRL-1807 cells in untreated cultures (−) and cultures treated with 10 μM MG-132 (MG-132), 0.17 μM geldenamycin (GD), 100 μM 5-fluorouracil (5-FU), 10 μM 5-aza-2′-deoxycytidine (5-Aza), 300 μM zinc (ZnSO4), and 4 mM butyrate (BA) for 12 hours. Extracts then were analyzed by immunoblotting using antibodies specific for Hsp70B′, Hsp72, and Actin

Proteasome inhibitor MG-132 is a potent activator of the hsp70B′ promoter

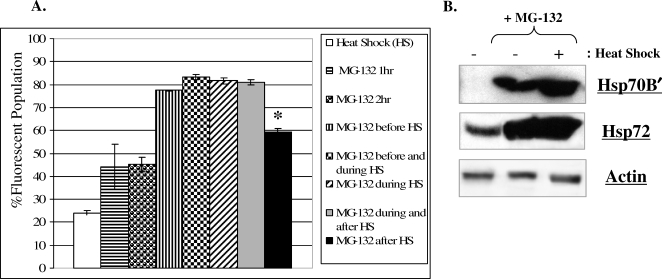

The HT-29 eGFP cell line has been characterized in a previous publication (Noonan et al 2007). This cell line expresses the eGFP protein regulated by the hsp70B′ promoter. To determine if the HT-29 hsp70B′ promoter responds to the proteasome inhibitor MG-132, HT-29 eGFP cells were treated with 10 μM MG-132 (Fig 2A) for 1 hour (horizontal line filled bars) or 2 hours (sphere filled bars) followed by a 24-hour recovery. The hsp70B′ promoter was activated in response to treatment of cells with MG-132. The HT-29 eGFP cells then were induced with both a standard heat shock (HS) and 10 μM MG-132 treatment in various sequences and examined by flow cytometry. Treatment with MG-132 before (vertical line filled and checkered bars) and during (diagonal line filled and gray scale bar) HS showed an additive effect on hsp70B′ promoter activation as compared to a standard HS (open bars) or MG-132 alone. Cells treated with MG-132 immediately following HS (closed bar) showed an increased promoter activation as compared to HS alone (open bar), but it was significantly lower than MG-132 treatment before or during HS (P < 0.001). These results indicate a preceding HS may precondition HT-29 cells to MG-132 treatment, resulting in lower hsp70B′ promoter activation.

Fig 2.

(A) HT-29eGFP cells were subjected to a standard heat shock (HS) of 42.5°C for 1 hour and/or treated with 10 μM MG-132 for 1 or 2 hours in various sequences immediately prior to or following HS. Cultures were given a 24-hour recovery at 37°C and heat shock protein (Hsp) 70B′ promoter activation then was examined by flow cytometry. (B) Western blot analysis of HT-29 cells treated with 10 μM MG-132 for 24 hours in unstressed control (−) and standard heat shock (+) conditions. Cytosolic extracts were prepared 24 hours from the start of heat treatment and analyzed by immunoblotting using antibodies specific to Hsp70B′, Hsp72, and the loading control, Actin

The Hsp70B′ protein levels also increased following treatment with MG-132 and HS (Fig 2B). Cultures that received both HS and MG-132 accumulated higher levels of Hsp70B′ relative to unstressed or MG-132 treatment alone. Hsp72 levels also increased following treatment with MG-132 or HS (Fig 2B). However, Hsp72 did not increase significantly in cultures that received the combined treatment, unlike the additive increases in Hsp70B′ levels.

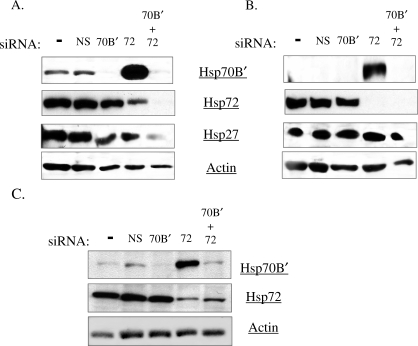

Hsp72 knockdown increases protein levels of Hsp70B′

In order to determine the contribution of Hsp70B′ to the stress response and to increased levels of damaged proteins, we used RNA interference to selectively knock down Hsp70B′ and Hsp72 in HT-29 and SW-480 colon carcinoma cell lines and in a nontransformed colonocyte cell line, CRL-1807 cells. siRNAs specific to human HspA1A/Hsp72 and HspA6/ Hsp70B′ were purchased from Dharmacon RNA technologies (Lafayette, CO, USA). For controls, we performed a mock transfection using the DharmaFECT reagent and no siRNA treatment or transfection with a nontargeting control siRNA. 48-hours posttransfection, cultures received a standard HS, followed by a recovery at 37°C. Cytosolic and nuclear extracts were collected at subsequent time points of 12 and 24 hours relative to the start of heat treatment, and Hsp70B′ and Hsp72 were detected by immunoblotting. Actin was detected as a control for equal protein loading. Knockdown of Hsp72 increased the cellular levels of cytosolic Hsp70B′ at 12 hours (Fig 3A). However, knockdown of Hsp70B′ did not affect Hsp72 expression under these conditions. Although Hsp70B′ normally is expressed transiently in cells after a HS, with Hsp70B′ expression returning to baseline after 24 hours, knockdown of Hsp72 promoted an accumulation of Hsp70B′ at later time points (Fig 3B). Knockdown of Hsp70B′ or Hsp72 did not affect levels of another cytosolic Hsp27 in HT-29 cells (Fig 3B). Hsp27 levels also remained unchanged in SW-480 and CRL-1807 cell lines following an Hsp70B′ knockdown (data not shown). The increase in cytosolic Hsp70B′ levels following knockdown of Hsp72 was also apparent in heat shocked SW-480 cells (Fig 3C). In SW-480 cells, there also was no change in Hsp72 levels in the Hsp70B′ knockdown cultures.

Fig 3.

Heat shock protein (Hsp) 70B′ and Hsp72 are regulated coordinately. HT-29 and SW-480 human colon carcinoma cells were transfected with nonspecific siRNA control (NS), Hsp70B′ siRNA (70B′), Hsp72 siRNA (72), and a combination of Hsp70B′ and Hsp72 siRNAs (70B′ + 72) at 100 nM concentration. A nontransfected control (−) and siRNA-treated cultures then were subjected to a standard heat shock. (A) Western blot analysis comparing cytosolic levels of Hsp70B′, Hsp72, Hsp27, and Actin in siRNA-treated HT-29 cells at 12 hours and (B) 24 hours post–heat shock, (C) and cytosolic levels of Hsp70B′, Hsp72, and Actin in SW-480 cells 12 hours post–heat shock

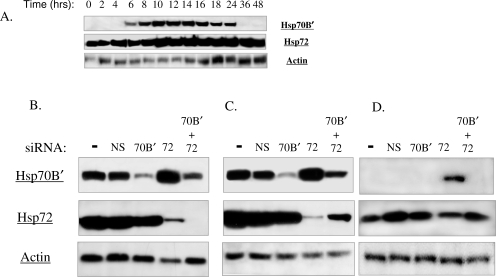

A time course of protein expression was determined for the nontransformed colonocyte cell line CRL-1807 and the kinetics of expression were found to be similar to the HT-29 cell line. The one exception was that Hsp70B′ levels remain stable for a longer time period in CRL-1807 cells; up to 24 hours post heat shock as compared to 18 hours in HT-29 cells (Fig 4A). Hsp72 also was induced rapidly but levels remained stable up to 48 hours following heat stress, as in the HT-29 cell line. To determine if Hsp70B′ and Hsp72 also were regulated coordinately in these nontransformed cells, siRNA transfections were performed (Fig 4B–D). Knockdown of Hsp72 promoted the accumulation of Hsp70B′ at the 12-hour (Fig 4B) and 24-hour time points (Fig 4C) in the CRL-1807 cell line similarly to the HT-29 cell line. At 48 hours, Hsp70B′ was normally depleted in the CRL-1807 cells (Fig 4A), however knockdown of Hsp72 promotes the accumulation of Hsp70B′ even 48 hours post–heat shock (Fig 4D). Again, knockdown of Hsp70B′ did not appear to affect levels of Hsp72 at any of the time points. For each of the siRNA knockdown experiments performed, the kinetics of expression in the nuclear extract was analogous to results obtained from cytosolic extracts (data not shown).

Fig 4.

(A) Western blot analysis of the temporal expression of heat shock protein (Hsp) 70B′ and Hsp72. CRL-1807 cells were grown at 37°C, heat shocked under standard conditions, and returned to 37°C; cytosolic extracts were taken at time points relative to the start of heat treatment. (B–D) CRL-1807 cells were transfected with nonspecific siRNA control (NS), Hsp70B′ siRNA (70B′), Hsp72 siRNA (72), and a combination of Hsp70B′ and Hsp72 siRNAs (70B′ + 72) at 100 nM concentration. A nontransfected control (−) and siRNA-treated cultures then were subjected to a standard heat shock. Western blot analysis comparing cytosolic levels of Hsp70B′, Hsp72, and Actin in siRNA-treated CRL-1807 cells at (B) 12 hours, (C) 24 hours, and (D) 48 hours post–heat shock

Knockdown of Hsp72 increases hsp70B′ promoter activation

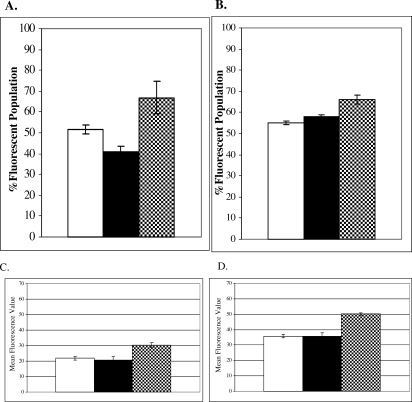

We next examined the effect of Hsp72 knockdown on hsp70B′ promoter activation. HT-29 eGFP cells were transfected with siRNA specific for Hsp70B′, Hsp72, a combination, or a nonspecific control (NS). 48 hours following transfection, the cells were subjected to a standard heat shock (Fig 5A) or MG-132 treatment (Fig 5B). Heat shocked cells were allowed to recover for 24 hours at 37°C and then all samples were analyzed by flow cytometry as described previously (see Control and heat shocked HT-29eGFP cultures analyzed by flow cytometry section). siRNA-treated cells in unstressed conditions showed no detectable activation of the hsp70B′ promoter (data not shown). As shown in Figure 5, following a standard HS or treatment with MG-132, Hsp72 and Hsp70B′ knockdown increased the number of cells with an activated hsp70B′ promoter. These results were statistically significant as compared to the NS control for both HS and MG-132 treatments (P-value = 0.04 and 0.02, respectively). We also examined the mean fluorescence value (a measure of average promoter activity) of the cell populations following heat stress and MG-132 treatment. The mean fluorescence of the HT-29 eGFP cells transfected with siRNA specific to Hsp72 was also higher compared to both NS control and Hsp70B′ knockdown cells following heat shock (Fig 5C) and treatment with MG-132 (Fig 5D). These results were statistically significant as compared to the NS control for both the heat shocked– and MG-132– treated cultures (P < 0.01). Therefore, the Hsp72 knockdown cells have a higher average level of activity of the hsp70B′ promoter following heat stress and treatment with proteasome inhibitor MG-132. These results indicate that depleting levels of Hsp72 under stressed conditions causes an overall increased activation of the hsp70B′ promoter in HT-29 cells. A summary of data collected in Figure 5 is shown in Table 1.

Fig 5.

Flow cytometric analysis of hsp70B′ promoter activation in siRNA treated cells. (A,B) The % fluorescence in the population was analyzed in HT-29eGFP cells transfected with nonspecific (NS) siRNA control (open bars), Hsp70B′ siRNA (closed bars), or Hsp72 siRNA (checkered bars) followed by (A) standard heat shock and (B) 10 μM MG-132 for 24 hours. (C) Mean fluorescence values of HT-29eGFP cell populations following heat shock and (D) 10 μM MG-132 for 24 hours.

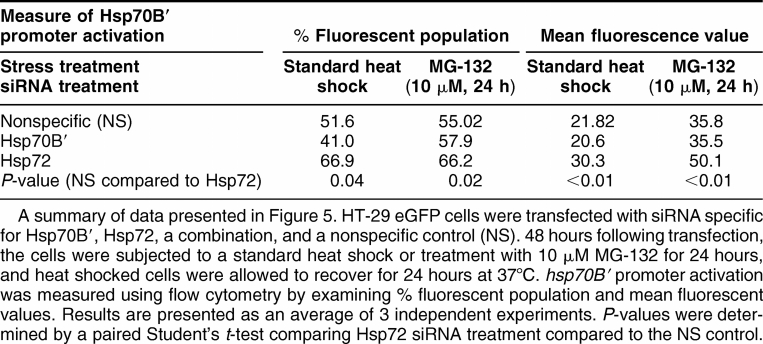

Table 1.

Knockdown of heat shock protein (Hsp) 72 increases hsp70B′ promoter activation

Viability of Hsp70B′ and Hsp72 knockdowns to heat stress and MG-132

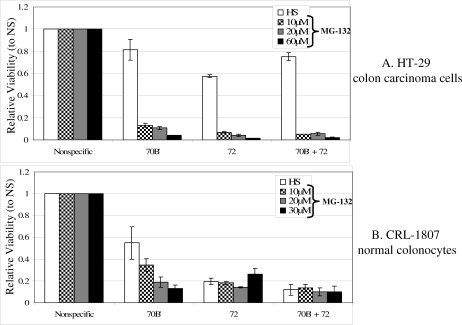

We determined whether Hsp72 or Hsp70B′ knockdown reduced the viability of HT-29 cells and CRL -1807 cells following HS or MG-132 treatment. Cultures were transfected with siRNA specific for Hsp70B′, Hsp72, a combination of the two, and a nonspecific control (NS). Cultures were HS at 42.5°C for 1 hour or treated with MG-132 at concentrations of 10, 20, or 60 μM for HT-29 cells, and 10, 20, or 30 μM for CRL-1807 cells. CRL-1807 cells are more sensitive to MG-132, so a maximum concentration of 30 μM was employed. Cell counts from each of the specific siRNA transfections were collected as described in the methods and were corrected to the nonspecific control group to determine the relative level of viability. Nonspecific control cultures in both cell lines maintained a higher percentage of viable cells in the standard heat stress group as compared to MG-132 treatments (data not shown).

Both HT-29 (Fig 6A) and CRL-1807 cells (Fig 6B) had a lower thermal resistance following Hsp70B′ or Hsp72 siRNA treatments. For both cell lines, the loss of viability was more pronounced when cells were treated with increasing concentrations of proteasome inhibitor MG-132. The decreased viabilities in the Hsp70B′ and Hsp72 siRNA cells following both heat stress and MG-132 treatment were statistically significant (P < 0.01) in all samples.

Fig 6.

Relative level of viability of siRNA-treated cells to heat shock (HS) and increasing concentrations of proteasome inhibitor MG-132. (A) HT-29 cells were transfected with nonspecific siRNA control (NS), heat shock protein (Hsp) 70B′ siRNA (70B′), Hsp72 siRNA (72), and a combination of Hsp70B′ and Hsp72 siRNAs (70B′ + 72) at 100 nM concentration. Cells then were subjected to a standard heat shock (open bars) or treatment with 10 μM (checkered bars), 20 μM (gray bars), and 60 μM (closed bars) MG-132. (B) CRL-1807 underwent the same transfection and treatment course except they were given a maximum treatment of 30 μM MG-132 (closed bars). Viability was determined by cell counting assay for viability (See Methods section for details)

DISCUSSION

Relative to other Hsp70 family members, the Hsp70B′ is characterized by its tight regulation and high inducibility. To obtain insight into the role of Hsp70B′ in cellular physiology, we screened a series of Hsp inducers for their ability to activate hsp70B′. Cytotoxic agents examined in this study included GD, an Hsp90 inhibitor; Zn++, a heavy metal ion; BA, a short chain fatty acid; and 5-FU, a pyrimidine analog (Roigas et al 1998; Winklhofer et al 2001; Qing et al 2004; Arvans et al 2005). 5-Aza, a DNA methyltransferase inhibitor shown to cause effects similar to heat shock under certain conditions, also was tested (Kim et al 1999; Gober et al 2003). We found that the ZnSO4 induction of Hsp70B′ and Hsp72 is cell line specific. In CRL-1807 cells, ZnSO4 induces Hsp70B′ and not Hsp72, suggesting that Hsp70B′ may play a primary role in the ZnSO4 stress response. Although GD and 5-FU induced Hsp72 in at least one of the cell lines tested, these stresses apparently were not significant enough to cause induction of Hsp70B′. Interestingly, the proteasome inhibitor MG-132 is a potent inducer of hsp70B′ in all the cell lines examined. It therefore appears that the accumulation of proteasome substrates (or perhaps the depletion of free ubiquitin) is a particularly potent inducer of Hsp70B′. It has been reported previously that proteasome inhibitors can activate heat shock transcription factor 1 (Hsf1) mediated transcription, and the hsp70B′ promoter contains 4 putative Hsf1 binding sites (Noonan et al 2007). It is not clear whether Hsf1 is solely responsible for this high degree of activation by the proteasome inhibitor or whether other promoter elements also come into play.

We also found that heat shock and proteasome inhibition together have an additive effect on Hsp70B′ expression. The amount of Hsp70B′ in cells subjected to HS and MG-132 treatment correlated with the increased activation of the hsp70B′ promoter. These two stress events likely increase the amount of damaged protein accumulation in cells. Hsp72 is also strongly induced by MG-132 and HS. Because Hsp70B′responds to the more intense stress event, it may be induced to supplement the levels of Hsp72. Interestingly, different organisms have elaborated during evolution different families of Hsps to cope with stress. In plants, the most abundant inducible Hsps are the small Hsps, and there are many isoforms. In certain fishes from stressful environments, such as the Sonoran Desert topminnow Poeciliopsis, many isoforms of both the small Hsp and Hsp70 families have evolved (Hightower et al 1999). In humans, and perhaps other large mammals, multiple isoforms of Hsp70 have evolved with Hsp70B′ utilized under severe proteotoxic circumstances.

Interestingly, we found lower levels of hsp70B′ activation in cells subjected to a HS prior to MG-132 exposure. Heat-conditioned cells have higher levels of stress proteins that participate in acquired thermotolerance or cytoprotection, and the higher levels of these proteins may obviate the need for Hsp70B′.

Because Hsp70B′ and Hsp72 are closely related (unpublished results) and show varying responses to proteotoxic stresses, we decided to examine their contributions to the cellular stress response, both individually and in combination. In all 3 cell lines examined, knockdown of Hsp72 using siRNA technology substantially increased levels of Hsp70B′ following stress, and knockdown of Hsp70B′ did not increase the levels of Hsp72. This finding supports the idea that Hsp72 is a primary responder to proteotoxic stress and that Hsp70B′ may be a secondary responder. In yeast, where the regulatory interactions among eukaryotic Hsp70 family members are best understood, members of a subfamily of Hsp70 proteins (SSA1, SSA2, SSA3, SSA4) are regulated similarly, with Ssa1 and 2 serving as primary responders and Ssa3 and 4 being more tightly regulated (Werner-Washburne et al 1987).

With regard to their role in cell survival to stress, Hsp72 knockdowns were comparatively more sensitive to a standard HS than Hsp70B′ knockdowns, whereas knockdown of either Hsp72 or Hsp70B′ sensitized cells to increasing concentrations of MG-132. This further supports the idea that Hsp70B′ plays a secondary response role in times of severe proteotoxic stress. As both Hsp70B′ and Hsp72 knockdowns show a dramatic loss in viability in response to MG-132 treatment, it is clear that both Hsp70s are essential to survival during intense proteotoxic stress. In addition to removing toxic levels of damaged proteins, Hsp72 also has been shown to inhibit apoptosis by preventing apoptosome formation, preventing translocation of Bax to the mitochondria, and through interactions with the MAPK pathyway (Beere et al 2000; Mosser and Morimoto 2004). It is not known whether Hsp70B′ also can act through similar mechanisms. We have shown herein that Hsp70B′ is essential to survival during intense proteotoxic stress. It is possible that Hsp70B′ may contribute to resistance to cell death in pathological conditions where this cellular state exists. There remains the interesting observation that Hsp70B′ is induced transiently and then rapidly degraded by a proteasome pathway in response to stress. Unlike Hsp72, high levels of Hsp70B′ are either not needed by cells or may be detrimental during prolonged recovery from stress or in the cytoprotected state. Determining whether or not Hsp70B′ also plays a role in cytoprotection and displays specific activation profiles in certain tissues or disease states may give us a clearer understanding of its physiological function(s).

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank C. Norris for expert assistance with flow cytometry. This work was funded by the University of Connecticut Research Foundation (grant 447393 to L.E.H.) and the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (grant ES03828).

Footnotes

ERRATA

The following errors that occurred in Noonan et al. in issue 12.3 have been corrected in 12.4:

- A layout error occurred in which Figure 1 image was attached to figure legend 6, and Figures 2 through 6 images were subsequently mismatched with their legends.

- Abstract: hyphens were removed after Hsp70B′ and Hsp72.

- Introduction: oedipus and taurus have been written with lowercase initial letters. Cotton-top tamarin has been correctly hyphenated.

- Results, first paragraph: (– treatment) was changed to untreated.

- Results, section headed ‘Knockdown of Hsp72 increases hsp70′ promoter activation’, line 13: Figure 6 was changed to Figure 5.

- Table 1 Legend: Figure 4 was changed to Figure 5.

- Discussion, paragraph 3: The phrase ‘we decided to examine their contributions both individually and in combination to the cellular stress response’ was changed to ‘we decided to examine their contributions to the cellular response, both individually and in combination’.

- Discussion, paragraph 4: The phrase ‘Interesting observation remains’ was changed to ‘There remains the interesting observation’.

REFERENCES

- Allen RL, O'Brien DA, Jones CC, Rockett DL, Eddy EM. Expression of heat shock proteins by isolated mouse spermatogenic cells. Mol Cell Biol. 1988;8:3260–3266. doi: 10.1128/mcb.8.8.3260.1098-5549(1988)008[3260:EOHSPB]2.0.CO;2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arvans DL, Vavricka SR, and Ren H. et al. 2005 Luminal bacterial flora determines physiological expression of intestinal epithelial cytoprotective heat shock proteins 25 and 72. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 288:G696–704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beere HM, Wolf BB, and Cain K. et al. 2000 Heat shock protein 70 inhibits apoptosis by preventing recruitment of procaspase-9 to the Apaf-1 apoptosome. Nat Cell Biol. 8:469–475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gober MD, Smith CC, Ueda K, Toretsky JA, Aurelian L. Forced expression of the H11 heat shock protein can be regulated by DNA methylation and trigger apoptosis in human cells. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:37600–37609. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M303834200.0021-9258(2003)278[37600:FEOTHH]2.0.CO;2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutierrez JA, Guerriero V Jr. 1995 Chemical modifications of a recombinant bovine stress-inducible 70 kDa heat shock protein (Hsp70) mimics Hsp70 isoforms from tissues. Biochem J. 305( Pt 1). 197–203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hightower LE, Norris CE, DiIorio PJ, Fielding E. Heat shock responses of closely related species of tropical and desert fish. Am Zool. 1999;39:877–888.0003-1569(1999)039[0877:HSROCR]2.0.CO;2 [Google Scholar]

- Kim HD, Kang HS, Rimbach G, Park YC. Heat shock and 5-azacytidine inhibit nitric oxide synthesis and tumor necrosis factor-alpha secretion in activated macrophages. Antioxid Redox Signal. 1999;1:297–304. doi: 10.1089/ars.1999.1.3-297.1523-0864(1999)001[0297:HSAAIN]2.0.CO;2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leung TK, Rajendran MY, Monfries C, Hall C, Lim L. The human heat-shock protein family. Expression of a novel heat-inducible HSP70 (HSP70B′) and isolation of its cDNA and genomic DNA. Biochem J. 1990;267:125–132. doi: 10.1042/bj2670125.0264-6021(1990)267[0125:THHPFE]2.0.CO;2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manzerra P, Rush SJ, Brown IR. Tissue-specific differences in heat shock protein hsc70 and hsp70 in the control and hyperthermic rabbit. J Cell Physiol. 1997;170:130–137. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4652(199702)170:2<130::AID-JCP4>3.0.CO;2-P.0021-9541(1997)170[0130:TDIHSP]2.0.CO;2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mosser D, Morimoto R. Molecular chaperones and the stress of oncogenesis. Oncogene. 2004;23:2907–2918. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207529.0950-9232(2004)023[2907:MCATSO]2.0.CO;2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noonan EJ, Place RF, Rasoulpour RJ, Giardina C, Hightower LE. Cell number–dependent regulation of Hsp70B′ expression: evidence of an extracellular regulator. J Cell Physiol. 2007;210:201–211. doi: 10.1002/jcp.20875.0021-9541(2007)210[0201:CNROHE]2.0.CO;2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norris CE, diIorio PJ, Schultz RJ, Hightower LE. Variation in heat shock proteins within tropical and desert species of poeciliid fishes. Mol Biol Evol. 1995;12:1048–1062. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a040280.0737-4038(1995)012[1048:VIHSPW]2.0.CO;2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parsian AJ, Sheren JE, Tao TY, Goswami PC, Malyapa R, Van Rheeden R, Watson MS, Hunt CR. The human Hsp70B gene at the HSPA7 locus of chromosome 1 is transcribed but nonfunctional. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2000;1494:201–205. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4781(00)00203-7.0006-3002(2000)1494[0201:THHGAT]2.0.CO;2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Place SP, Hofmann GE. Comparison of Hsc70 orthologs from polar and temperate notothenioid fishes: differences in prevention of aggregation and refolding of denatured proteins. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2005;288:R1195–1202. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00660.2004.1522-1490(2005)288[R1195:COHOFP]2.0.CO;2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qing G, Duan X, and Jiang Y 2004 Induction of heat shock protein 72 in RGCs of rat acute glaucoma model after heat stress or zinc administration. Yan Ke Xue Bao. 20:30–33.51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rensing SA, Maier UG. Phylogenetic analysis of the stress-70 protein family. J Mol Evol. 1994;39:80–86. doi: 10.1007/BF00178252.0022-2844(1994)039[0080:PAOTSP]2.0.CO;2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roigas J, Wallen ES, Loening SA, Moseley PL. Effects of combined treatment of chemotherapeutics and hyperthermia on survival and the regulation of heat shock proteins in Dunning R3327 prostate carcinoma cells. Prostate. 1998;34:195–202. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0045(19980215)34:3<195::aid-pros7>3.0.co;2-h.0270-4137(1998)034[0195:EOCTOC]2.0.CO;2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tavaria M, Gabriele T, Kola I, Anderson RL. A hitchhiker's guide to the human Hsp70 family. Cell Stress Chaperones. 1996;1:23–28. doi: 10.1379/1466-1268(1996)001<0023:ahsgtt>2.3.co;2.1466-1268(1996)001[0023:AHGTTH]2.0.CO;2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Werner-Washburne M, Stone DE, Craig EA. Complex interactions among members of an essential subfamily of hsp70 genes in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Cell Biol. 1987;7:2568–2577. doi: 10.1128/mcb.7.7.2568.1098-5549(1987)007[2568:CIAMOA]2.0.CO;2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White CN, Hightower LE, Schultz RJ. Variation in heat shock proteins among species of desert fishes (Poeciliidae, Poeciliopsis) Mol Biol Evol. 1994;11:106–119. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a040085.0737-4038(1994)011[0106:VIHSPA]2.0.CO;2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winklhofer KF, Reintjes A, Hoener MC, Voellmy R, Tatzelt J. Geldanamycin restores a defective heat shock response in vivo. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:45160–45167. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M104873200.0021-9258(2001)276[45160:GRADHS]2.0.CO;2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamashita M, Hirayoshi K, Nagata K. Characterization of multiple members of the HSP70 family in platyfish culture cells: molecular evolution of stress protein HSP70 in vertebrates. Gene. 2004;336:207–218. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2004.04.023.0378-1119(2004)336[0207:COMMOT]2.0.CO;2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]