Summary

The tropomodulins are a family of proteins that cap the pointed, slow-growing end of actin filaments and require tropomyosin for optimal function. Earlier studies identified two regions in Tmod1 that bind the N terminus of tropomyosin, though the ability of different isoforms to bind the two sites is controversial. We used model peptides to determine the affinity and define the specificity of the highly-conserved N termini of three short, non-muscle tropomyosins (α, γ, δ-TM) for the two Tmod1 binding sites using circular dichroism spectroscopy, native gel electrophoresis, and chemical crosslinking. All tropomyosin peptides have high affinity to the second Tmod1 binding site (within residues 109–144; α-TM, 2.5 nM; γ-TM, δ-TM, 40–90 nM), but differ >100- fold for the first site (residues 1–38; α-TM, 90 nM; undetectable at 10 µM, γ-TM, δ-TM). Residue 14 (R in α; Q in γ, δ), and to a lesser extent, residue 4 (S in α; T in γ, δ) are primarily responsible for the differences. The functional consequence of the sequence differences is reflected in the more effective inhibition of actin filament elongation by full-length α-TMs than γ-TM in the presence of Tmod1. The binding sites of the two Tmod1 peptides on a model tropomyosin peptide differ, as defined by comparing 15N¹H HSQC spectra of a 15N-labeled model tropomyosin peptide in the absence and presence of Tmod1 peptide. The NMR and circular dichroism studies show that there is an increase in α-helix upon Tmod1-tropomyosin complex formation, indicating that intrinsically disordered regions of the two proteins become ordered when they bind. A proposed model for the binding of Tmod to actin and tropomyosin at the pointed end of the filament shows how the tropomodulin-tropomyosin accentuates the asymmetry of the pointed end and suggests how subtle differences among tropomyosin isoforms may modulate actin filament dynamics.

Keywords: tropomyosin, tropomodulin, actin filament, circular dichroism, nuclear magnetic resonance

Introduction

The reversible polymerization of actin is essential for many cellular functions including determination of shape, directional movement, cytokinesis and intracellular transport 1. Proteins that physically stabilize or regulate the exchange of subunits at the filament ends allow formation of stable cellular structures. Members of two protein families, tropomyosin and tropomodulin, form a complex that binds at the pointed end of sarcomeric actin filaments in striated muscle and filaments in the erythrocyte membrane cytoskeleton 2. The complex forms a tight cap in vitro, but in vivo actin subunits at the pointed end are exchangeable 3.

Both tropomyosin and tropomodulin are multigene families, and expression is cell, tissue, and developmentally regulated. More than 40 tropomyosin isoforms are the products of four genes in vertebrates 4. Their coiled-coil structure and the ability to bind to the sides of the actin filament are held in common, but alternatively-expressed N-terminal and C-terminal, as well as internal exons, contribute to isoform-specific functions and cellular localizations. For example, long tropomyosins expressed in muscle as well as non-muscle cells have a highly-conserved N terminus. In short, non-sarcomeric tropomyosins expressed primarily in non-muscle cells the sequence encoded by the first two exons of the long isoforms is replaced by a single exon. All four genes encode short isoforms, some of which have specific cellular localizations 4.

The tropomodulin gene family also has four members, whose products Tmod1-Tmod4, have specific expression patterns, and isoform-specific affinities for tropomyosin. Of these, Tmod1, found in muscle cells and erythrocytes, is the best studied. It has different binding specificities for tropomyosin than Tmod4, found in skeletal muscle 5. Tmod1 is essential for cardiac myofibril assembly, and a null mutant is lethal in mouse 6; 7. Tmod 3, ubiquitous tropomodulin, unlike other tropomodulins binds monomeric actin 8.

Tmod is an elongated molecule; the functional domains and binding specificity have been most extensively analyzed in Tmod1. The C-terminal half contains alternating α-helices and β-strands that form a LRR (leucine-rich repeat) 9. The N-terminal half is mostly disordered 10; 11, but has three of four known binding sites: two binding sites for the N terminus of tropomyosin (res. 1–38 and 109–144 in Tmod1) and a tropomyosin-dependent capping site 12; 13; 14.

Our goal is to understand the structural basis for capping the tropomyosin-actin filament by Tmod. Using model peptides for α-tropomyosins, we previously reported that Tmod1 cooperatively binds two tropomyosin molecules 14. We proposed a working model for the pointed end of the actin filament in which one Tmod1 molecule uses the two TM-binding sites to bind to the N-termini of the tropomyosins on each side of the actin filament at the pointed end. The model is consistent with our tropomyosin binding and actin polymerization studies with Tmod1 together with both long and short α-tropomyosins. However, previous studies with a non-muscle tropomyosin encoded by the γ-TM gene, TM5NM1, indicated that this isoform binds only to the second binding site on Tmod1 15; 16. Since the N-terminal sequences of the short tropomyosins are highly conserved, a comparative analysis of the tropomyosin-Tmod1 affinities and effect on polymerization offers the opportunity to understand the structural basis for tropomodulin binding and isoform specificity. Our results show that the highly-conserved N-termini of short tropomyosins have high affinity for the second TM-binding site in Tmod1, but the isoforms differ more than 100–fold for the first site, and that the TM structures in the two complexes are different.

Results

Characterization of γTM binding to Tmod1

Tmod1 cooperatively binds two molecules of a short α-tropomyosin N-terminal model peptide that contains the Tmod1 binding site (αTM1bZip). Both tropomyosin binding sites are required for the most effective capping by Tmod1 with a short α-TM (αTM5a) that expresses exon αTM1b, or a long α-TM that expresses the alternative first exon, αTM1a (αstTM) 14. Others have reported that tropomyosin expressing exon γTM1b (γTM5NM1) binds with high affinity only to the second site on Tmod1 15; 16; 17. Isoform-specific binding of tropomyosin to Tmod1 would have consequences for capping the pointed end of filaments and regulation of actin dynamics in cells.

The conservation of the N-terminal sequence encoded by exon 1b among the three vertebrate tropomyosin genes, which encode short tropomyosins (Table 1), allows analysis of the sequence requirements for binding to the two sites on Tmod1. We used synthetic model peptides in which the first 19 residues are exon 1b-encoded tropomyosin sequence, followed by 18 residues of the GCN4 leucine zipper to stabilize coiled coil formation, a model we used in our previous studies and whose structure we determined 18. The binding of the model peptides to Tmod1 and its fragments was analyzed using non-denaturing polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, chemical crosslinking, and circular dichroism spectroscopy (CD).

Table 1. Alignment of TMZip sequences.

Sequences of TM chimeric proteins containing the N-termini of short non-muscle TMs: αTM5a, αTM1bZip; γTM5NM1, γTM1bZip; and δTM4, δTM1bZip, encoded by exon 1b. Residues 20 to 37 of the peptides correspond to the last 18 C-terminal residues (264–281) of the yeast transcription factor GCN4 41. The residues that are coiled coil are labeled with the residue position of the heptad repeats. Bold - residues different between αTM1bZip and two other short TM peptides, underlined – changed residues. αTM1bZip in previous studies was called AcTM1bZip.

| TM peptide [source] | Tropomyosin sequence | GCN4 sequence |

|---|---|---|

| αTM1bZip [αTM5a] | AGSSSLEAVRRKIRSLQEQ | NYHLENEVARLKKLVGER |

| γTM1bZip [γTM5NM1] | AGSTTIEAVKRKIQVLQQQ | NYHLENEVARLKKLVGER |

| δTM1bZip [δTM4] | AGLNSLEAVKRKIQALQQQ | NYHLENEVARLKKLVGER |

| αTM1bZip (S15V/E18Q) | AGSSSLEAVRRKIRVLQQQ | NYHLENEVARLKKLVGER |

| αTM1bZip p(S4T/R14Q) | AGSTSLEAVRRKIQSLQEQ | NYHLENEVARLKKLVGER |

| αTM1bZip (S4T) | AGSTSLEAVRRKIRSLQEQ | NYHLENEVARLKKLVGER |

| αTM1bZip (R14Q) | AGSSSLEAVRRKIQSLQEQ | NYHLENEVARLKKLVGER |

| heptad repeat | a d a d | a d a d a |

To learn if there are one or two binding sites for the short γ-TM, γTM5NM1, on the tropomodulin molecule, we studied complex formation between full-length Tmod1 and the TM peptide, γTM1bZip, using non-denaturing gel-electrophoresis and CD. Figure 1 illustrates the gel-electrophoresis results. Tmod1 forms a complex with γTM1bZip as well as with the α-TM peptide, αTM1bZip, as a control. However, the complexes have different mobilities. The mobility of the Tmod1-γTM1bZip complex is intermediate between Tmod1 and the Tmod1 - αTM1bZip complex. The intermediate mobility was observed for a complex between one Tmod1 molecule and one molecule of αTM1bZip 14. Therefore, in these conditions Tmod1 forms a stable complex with only one molar equivalent of the γTM1bZip peptide.

Figure 1.

Complex formation between Tmod1 and TM peptides monitored by non-denaturing polyacrylamide gel-electrophoresis. Lane 1 and 4, Tmod1; lane 2, Tmod1 and αTM1bZip; lane 3, Tmod1 and γTM1bZip. TM peptides are positively charged and do not enter the gel. Arrowhead indicates Tmod1, arrows indicate complexes.

To characterize the affinity of γTM1bZip for the two tropomyosin binding sites on Tmod1, we synthesized peptides that correspond to the two sites: Tmod11–38 and Tmod1109–144 11; 14. We measured the interaction between γTM1bZip and the two Tmod peptides using CD (Figure 2). At peptide concentrations of 10 µM, there was an increase in helicity and Tm in the γTM1bZip/ Tmod1109–144 mixture (Figure 2A, Table 2), but no change in the γTM1bZip/ Tmod11–38 mixture (Table 2), indicating γTM1bZip binds the second Tmod1 site (with lower affinity than αTM1bZip), but not the first one. However, at 30 µM peptide there were modest increases in helicity and Tm (Figure 2B), showing that γTM1bZip does bind the first Tmod1 site, but that the binding constant is 100-fold weaker than αTM1bZip (~2.3 µM versus 0.0025 µM at 10 µM, Table 2). As calculation of dissociation constants requires the assumption that all peptides in the mixture are tightly bound, the true Kd may be even weaker. Complex formation in mixtures of Tmod11–38 and αTM1bZip or γTM1bZip was also assayed by native gel-electrophoresis and binding only to αTM1bZip was detected (Figure 5, lanes 1–3), supporting our CD data, and the mutagenesis studies from other laboratories 15; 16.

Figure 2.

Binding of Tmod1 fragments to TM peptides measured using circular dichroism spectroscopy. (A): Tmod1109–144 and γTM1bZip, the peptide concentrations were 10 µM in 100 mM NaCl, 10 mM sodium phosphate, pH 7.0. (B): Tmod11–38 and γTM1bZip, and (C): Tmod11–38 and δTM1bZip, the peptide concentrations were 30 µM in 100 mM NaCl, 10 mM sodium phosphate, pH 7.0. (●) Tmod1 peptide; (○)TM peptide; (▽) sum of the folding curves of TM and Tmod1 peptides; (▼) the folding of the mixture of TM and Tmod1 peptides.

Table 2. Binding of tropomodulin peptides to tropomyosin peptides.

The difference in the observed midpoints of the cooperative unfolding transitions (determined from the first derivative of the unfolding curves) of the mixture of the TMZip and Tmod fragments and the additions of the curves for the TMZip and Tmod fragments alone. The Kd values were estimated from the thermodynamics of unfolding of the complexes compared with the Tmod fragments and TMZips alone. All components were 10 µM in 100 mM NaCl, 10 mM sodium phosphate, pH 7. NC – not calculated.

| Tmod11–38 | Tmod1109–144 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ΔTm, °C | Kd 30°C, µM | ΔTm, °C | Kd 30°C, µM | |

| αTM1bZip | 7.1±0.5 | 0.09±0.02 | 13.8±0.6 | 0.0025±0.0011* |

| γTM1bZip | no change | NC | 12.5±2.2 | 0.04±0.03 |

| δTM1bZip | no change | NC | 7.8±2.1 | 0.09±0.02 |

| αTM1bZip (S15V/E18Q) | 6.1±0.4 | 0.21±0.01 | 11.7±0.2 | 0.017±0.003 |

| αTM1bZip (S4T/R14Q) | no change | NC | 7.6 | 0.11 |

| αTM1bZip (S4T) | 4.0±0.3 | 0.39±0.01 | 13.4±0.1 | 0.04±0.02 |

| αTM1bZip (R14Q) | no change | NC | 4.9±0.2 | 0.26±0.21 |

previously reported 14

Figure 5.

Complex formation between Tmod11–38 and TM peptides monitored by non-denaturing polyacrylamide gel-electrophoresis. Lane 1, Tmod11–38; lane 2, Tmod11–38 and αTM1bZip; lane 3, Tmod11–38 and γTM1bZip; lane 4, Tmod11–38 and δTM1bZip; lane 5, Tmod11–38 and αTM1bZip(S4T); lane 6, Tmod11–38 and αTM1bZip(R148Q); lane 7, Tmod11–38 and αTM1bZip (S4T/R148Q); lane 8, Tmod11–38 and αTM1bZip(S15V/E18Q). TM peptides are positively charged and do not enter the gel. The difference in mobility of complexes is due to isoelectric points of TM peptides (pI=10.4 for αTM1bZip(S15V/E18Q) and 9.9 for αTM1bZip and αTM1bZip(S4T). Arrow indicates Tmod11–38, arrowhead indicates complexes.

Tmod1/ γTM1bZip interaction was also assayed using covalent cross-linking, since an unstable complex may not have been detected using non-denaturing gel electrophoresis. Mixtures of N-terminal Tmod fragments that contain the first tropomyosin binding site, Tmod11–38 or Tmod11–92, with γTM1bZip were cross-linked with glutaraldehyde (0.4 nmol each peptide). αTM1bZip was used as a positive control. An additional band appeared when Tmod fragments were mixed with TM1b peptides and treated with glutaraldehyde (Fig. 3A). There was a small amount of crosslinked γTM1bZip-Tmod11–38 compared to αTM1bZip-Tmod11–38 (Figure 3A, lanes 4 and 6), but the complex with Tmod11–92 yielded more crosslinked product (Figure 3A, lane 9). The positions of the crosslinked bands differed from the peptide dimer which migrated as a faint band above the uncrosslinked peptide (Figure 3B, lane 4). As a negative control for non-specific cross-linking, we used a C-terminal fragment of TM that does not have a Tmod binding site, αTM9d252–284. No additional band appeared in the mixture of Tmod11–92 with αTM9d252–284 (Figure 3B, lane 3). We conclude that γTM1bZip can bind to the first binding site in Tmod1, but its affinity is low. If true, Tmod11–92, the N-terminal fragment, which contains the first TM-binding site as well as the TM-dependent actin-capping site, should be able to inhibit actin polymerization in the presence of a full-length γ1b tropomyosin, γTM5NM1.

Figure 3.

The cross-linking of TM model peptides and Tmod1 N-terminal fragments with glutaraldehyde monitored by the SDS-PAGE (15 % polyacrylamide). A: Complex formation: lane 1, Tmod11–38; lane 2, Tmod11–38 treated with glutaraldehyde; lane 3, Tmod11–38/ αTM1bZip; lane 4, Tmod11–38/ αTM1bZip treated with glutaraldehyde; lane 5, Tmod11–38/ γTM1bZip; lane 6, Tmod11–38/ γTM1bZip treated with glutaraldehyde; lane 7, Tmod11–92 treated with glutaraldehyde; lane 8, Tmod11–92/ γTM1bZip; lane 9, Tmod11–92/ γTM1bZip treated with glutaraldehyde; lane 10, Tmod11–92. B: Control for non-specific cross-linking: lane 1, TM9d252–284; lane 2, TM9d252–284 treated with glutaraldehyde; lane 3, Tmod11–92/ TM9d252–284 treated with glutaraldehyde; lane 4, γTM1bZip treated with glutaraldehyde. The arrowheads indicate individual proteins, whereas the arrows indicate complexes.

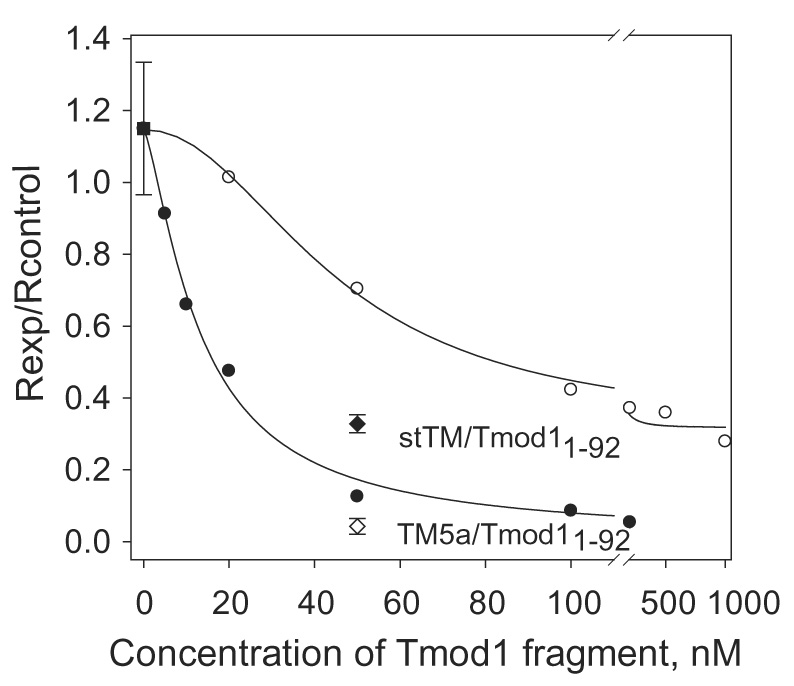

Inhibition of actin filament elongation in the presence of γTM5NM1 and Tmod1 fragments

Actin polymerization on gelsolin-capped seeds was assayed using pyrene-actin fluorescence in the presence of γTM5NM1 and Tmod11–344 or Tmod11–92. We used Tmod11–344 instead of full-length Tmod1 because removal of the C-terminal 15 residues destroys tropomyosin-independent capping without influencing the capping ability in the presence of tropomyosins 19.

Gelsolin-capped actin filaments were combined with saturating concentrations of γTM5NM1 (2.5 µM) and elongation was measured as a function of Tmod1 concentration (see Materials and Methods). The concentration of γTM5NM1 required for saturation is 5-fold higher than for αTM5a and 3-fold higher than for αstTM 13; 19. Both Tmod11–344 and Tmod11–92 inhibited elongation of actin filaments in the presence of γTM5NM1, although Tmod11–92 was less effective, reaching 50% inhibition of maximal Tmod11–344 inhibition at ~65 nM compared to ~15 nM with Tmod11–344. The poor inhibition by γTM5NM1 even at the highest Tmod11–92 concentrations compared to αstTM or αTM5a presumably reflects its lower affinity for the first binding site.

Identification of residues responsible for isoform specific binding of tropomyosin to Tmod1

The differences in affinity of the TM1bZip peptides for the first Tmod1 binding site offer the opportunity to learn how the sequence in this conserved region of tropomyosin encodes information for binding Tmod1. The contrasts between αTM1bZip and γTM1bZip binding to the first Tmod1 site and the ability to block elongation with Tmod11–92 are striking considering 12 of 19 residues are identical, and most of the changes are conservative (Table 1). These sequences are encoded by exon 1b of the α- and γ-TM genes, respectively, and are more similar to each other than either one is to the N-terminus of stTM, encoded by exon 1a of the α-TM gene. In an effort to learn which residues in short tropomyosins define the affinity for Tmod1 we designed several TM1bZip peptides and analyzed their binding to Tmod1. To help solve the puzzle, we also made δ-TM1bZip peptide that has the sequence of another widely-expressed short non-muscle tropomyosin (δTM4) and shares some of the differences of γTM1bZip from αTM1bZip (Table 1).

The interaction of δTM1bZip to Tmod11–38 and Tmod1109–144 was assayed by non-denaturing gel electrophoresis and CD. The binding characteristics of δTM1bZip were similar to those of γTM1bZip. There was no band corresponding to a complex with Tmod11–38 in native gels (Figure 5, lane 4), and there were small increases in helicity and Tm only at 30 µM peptide (Figure 2C, Table 2). Like γTM1bZip, it bound to Tmod1109–144 but with lower affinity than αTM1b (Table 2). The differences are striking considering there are five sequence differences between the δTM1bZip and γTM1bZip and six with αTM1bZip (Table 1).

Based on the sequences of αTM1bZip and γTM1bZip, the differences in Tmod1 binding must be caused by changes in one or more of the following residues: 4, 10, 14, 15, 18. The importance of these residues was tested using an iterative loss-of-function approach by introducing γTM1bZip residues into the αTM1bZip sequence in synthetic peptides. Two peptides were synthesized with changes in the αTM1b sequence: αTM1bZip(S15V/E18Q) and αTM1bZip(S4T/R14Q). The peptide with the S15V/E18Q mutation bound Tmod11–38, but the peptide with the S4T/R14Q mutation lost its binding ability (Figure 5, lanes 7–8). To determine the residue responsible for the loss of binding, two other peptides were synthesized: αTM1bZip(S4T) and αTM1bZip(R14Q). The peptide with the S4T mutation bound to Tmod11–38, but the peptide with the R14Q mutation had greatly reduced binding (Figure 5, lanes 5–6). The changes in affinity of all mutants for both TM-binding sites were assayed using CD. The changes in Tm values and dissociation constants, calculated from the CD curves, are given in Table 2. According to these data, the change of S4 to T decreased the affinity of the αTM1b peptide for Tmod11–38 fourfold, whereas the change of R14 to Q resulted in almost complete loss of binding in these conditions.

NMR studies of the αTM1bZip/Tmod11–38 and αTM1bZip/Tmod1109–144 complexes

In order to define the binding sites of the Tmod1 peptides on the N terminus of tropomyosin, we compared 15N-¹H HSQC spectra of 15N-αTM1bZip in the presence and absence of unlabeled Tmod1 peptides (Figure 6). We previously determined the structure of 15N-αTM1bZip 18. The first five residues are disordered, and starting with L6 the structure is canonical coiled coil until the C-terminal three residues. For the NMR study, the N-acetyl group in the synthetic peptide was substituted with an initial Gly to allow isotopic labeling; its affinity for Tmod11–38 was within experimental error of the N-acetylated peptide (0.13 vs 0.09 µM). The complexes were stoichiometric with 1 Tmod1 peptide (one chain):1 αTM1bZip (two chains), and therefore are, by definition, asymmetric. Both complexes showed more crosspeaks than the unbound peptide, indicating complex formation. Comparison of the 15N-¹H HSQC spectrum of the unbound peptide (in which the crosspeaks have been assigned) with those in the complexes gave information about the extent of the binding site of the Tmod peptide on tropomyosin.

Figure 6.

15N-¹H HSQC spectra of 15N-αTM1bZip in the presence and absence of tropomodulin fragments. Panel A, (red) 15N-αTM1bZip, (cyan) 15N-αTM1bZip + unlabeled Tmod11–38. Panel B, (red) 15N- αTM1bZip, (cyan) 15N-αTM1bZip + unlabeled Tmod1109–144. The peptides were each ~0.5 mM in 100 mM NaCl, 10 mM NaCl, 5% deuterium oxide, pH 6.5. Data were acquired on a Bruker 800 MHz NMR spectrometer. Note in unbound αTM1bZip Q19 overlaps R11 and V27 overlaps N20.

Figure 6A illustrates the 15N-¹H HSQC spectra of the 15N-αTM1bZip, free (red) and in complex with Tmod11–38 (cyan). In the unbound TM peptide there are 43 crosspeaks, 35 from backbone amides (two overlap) and 8 from sidechain amides. In the complex, there were 63 crosspeaks, and the major shifts were in peaks from the tropomyosin region of the peptide (versus the GCN4 region). Of these, it was possible to assign the additional crosspeaks for sidechain amides (Q17 is shifted) and the backbone amide crosspeaks for residues 1–5. All were shifted (greatest in S3, S4, S5) and res. 1, 3–5 became doublets. This means that the first five TM residues that are disordered in the free peptide have a regular structure in the complex. The doublets show that the environments of the chains are different (expected in an asymmetric structure) and that the chains are in slow exchange, evidence for formation of a tight complex. While the binding engaged all 19 residues in the TM region, the GCN4 domain was not involved in a major way.

The first 92 residues of Tmod1 are naturally unfolded, the only ordered structure being the α-helix formed by res. 24–35. Binding of αTM1bZip to 15N-Tmod11–92 shifts residues 1–38, showing they all change upon binding to tropomyosin 11. A Tmod1 peptide containing only the helical region (res. 23–38) was less helical and did not bind αTM1bZip, as assayed by native gel electrophoresis and circular dichroism, giving further support for the designation of res. 1–38 as a tropomyosin binding site (data not shown).

The binding of Tmod1109–144 to αTM1bZip caused more changes in the 15N-¹H HSQC spectrum, indicating a more extensive interface than with Tmod11–38 (Figure 6B). There were 42 additional crosspeaks arising from changes in the tropomyosin, 16 from side chain amides (Q17, Q19, N20, N25) and 26 from backbone amides (19 from tropomyosin, 7 from GCN4). The changes were greatest in the tropomyosin region, but the interface must extend into the GCN4 region. As with Tmod11–38, the crosspeaks assigned to S3, S4, and S5 were doublets, evidence for an ordered, stable structure.

The 15N-¹H HSQC spectra give no specific structural information, but they show that the binding sites on tropomyosin for the two Tmod1 peptides are different. Since a single tropomodulin binds two molecules of tropomyosin at the pointed end of an actin filament, the interactions add to the intrinsic asymmetry of the filament end.

Discussion

In this work we show that all tropomyosins bind to two sites on Tmod1, and that isoform-specific differences in affinity for the two sites contribute to the efficiency in capping the pointed end of the actin filament. Using NMR we defined the regions of tropomyosin involved in both tropomodulin binding sites and show that the tropomyosin structures are different in the two complexes. Together the results illustrate how the tropomyosin-tropomodulin cap enhances the asymmetry of the pointed end. We also show that subtle sequence differences among tropomyosin isoforms can have major effects on the affinity for the first Tmod1 binding site and thereby modulate the dynamics of the actin filament’s pointed end.

The analysis resolves a long-standing debate in the literature concerning the location of tropomyosin binding sites on tropomodulin. Babcock et al. 17 showed that the binding site for γ-TM5NM1 on Tmod1 is within residues 90–184, recently localized to the region including residue 135 15; 16. The suggestion that it is a solitary binding site contradicts our model that one tropomodulin molecule binds two tropomyosin molecules at the pointed end, shown to be true for both short and long α-tropomyosins (α-TM5a and α-stTM) 14. We have now resolved the question by showing that γ-tropomyosin and δ-tropomyosin can bind to both Tmod1 sites, but with much lower affinity than α-tropomyosin to the first site. Further evidence for γTM5NM1 binding the first site is that it inhibits elongation with Tmod11–92, even though the second TM-binding site is absent in this Tmod1 fragment. However, the inhibition is incomplete compared to Tmod11–344, showing that the lower affinity for the first site makes γ-tropomyosin a less effective capper of the pointed end.

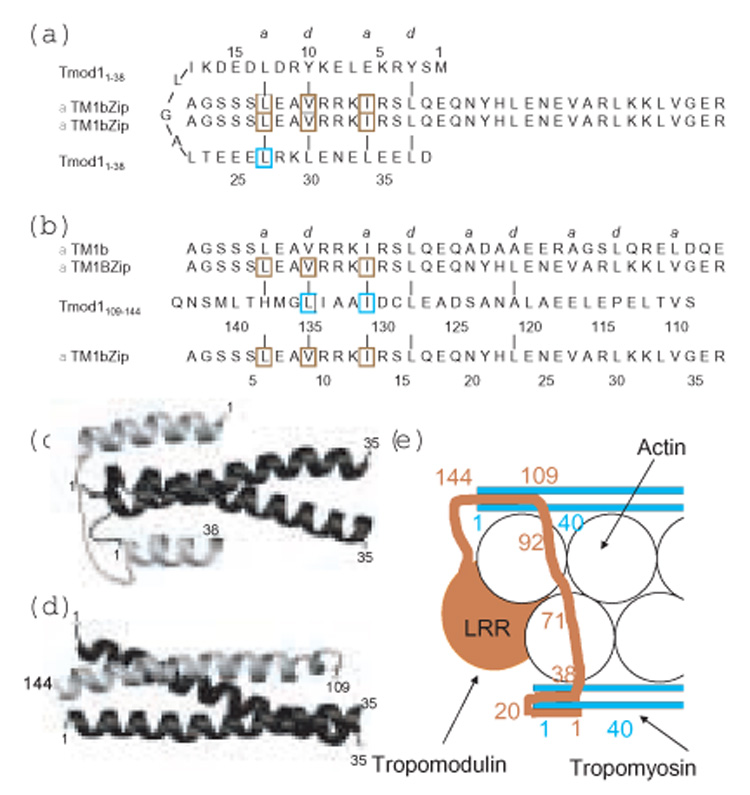

The NMR studies indicate the extent of the two Tmod1 binding sites on αTM1bZip and show that the tropomyosin structures are different in the two complexes. While the structures of Tmod1-TM complexes remains to be solved, we have put forth hypotheses about the secondary structure and orientations of the chains in the complexes. The models shown in Figure 7, which we emphasize are cartoons, are based on circular dichroism spectra of the complexes, the effects of complex formation on the ¹H-15N HSQC spectra of αTM1bZip, and mutagenesis studies 11; 14; 15; 16. The circular dichroism spectra of the complexes of both Tmod peptides with αTM1bZip are >80 % helical, suggesting that upon binding there is formation of a large amphipathic helical or coiled-coil interface.

Figure 7.

Schematic of possible binding modes of Tmod11–38 and Tmod1109–144 to αTM1bZip. (a, b) The sequences and possible coiled-coil interactions at a and d positions of the heptad repeat of the two Tmod binding sites for αTM1bZip. Mutations in Tmod1 that cause loss of binding to TM 11; 13; 14 15; 16 are outlined in cyan, and mutations in TM5NM1 that cause loss of binding to Tmod1 are outlined in brown 20. (c,d) Models of possible structures of the binding interfaces. In the models, the two chains of αTm1bZip are black and the single chains of the two Tmod1 peptides are grey. (a,c) Residues 1–13 of Tmod11–38 bind antiparallel to the αTM1bZip coiled coil on one side of the tropomyosin interface, residues 15 to 26 loop around the N-terminus of TM and residues 24–36 bind parallel to the other side of the tropomyosin coiled coil interface. (b,d) Residues 121–138 of Tmod1109–144 bind antiparallel to residues 6 to 23 of αTm1bZip to form a three helix bundle. (e) Cartoon model of the binding of Tmod (terra cotta) to tropomyosin (cyan) at the pointed end of the actin filament (white) to illustrate how one Tmod1 may interact with the N-termini of two TM molecules on opposite sides of the actin helix to cap the pointed end. The TM-dependent capping site includes residue 71 and is shown binding to actin. The TM-independent capping site at the extreme C-terminus of Tmod1 is not shown.

When Tmod11–38 binds 15N-labeled TM1bZip there are changes in the crosspeaks of the 19 tropomyosin residues in the ¹H-15N HSQC spectrum, with minor perturbations of the GCN4 residues. The only ordered structure in Tmod11–92 is an α-helix in residues 24–35, yet in the HSQC spectrum of 15N-¹H-Tmod11–92 almost all the residues between 1 and 38 are broadened and shifted upon complex formation with αTM1bZip. This observation, together with the large increase in helicity upon complex formation, suggests that the binding site is more extensive than the residue 24–35 helix and that the intrinsically disordered region of Tmod1 becomes ordered upon binding. Mutagenesis of L27 to E greatly reduces the affinity of Tmod11–38 for αTM1bZip suggesting a requirement for an amphipathic helix that may form a coiled coil interface with the tropomyosin coiled coil starting at L6 11. Figure 7a,c illustrates a possible model in which residues 24–38 of Tmod1 are oriented parallel to residues 2–16 of αTM1bZip helix, since in an antiparallel arrangement of the coiled coil interface would extend into the GCN4 portion of the molecule. Since the first 22 residues of Tmod1 are also involved in binding αTM1bZip and must contribute to the increase in helix upon complex formation, they might interact in an antiparallel sense with residues 2–17 on the opposite side of the tropomyosin coiled coil. Possible hydrophobic interactions are consistent with such a model (Figure 7).

The model gives insight into a possible explanation for the importance of R14 in αTM1bZip for binding the first Tmod1 binding site. When the chains are aligned as in Figure 7a, R14 of tropomyosin could form an intermolecular salt bridge with E33 of Tmod1. Mutation of R14 to Q as in γTM1bZip or δTM1bZip would weaken this interaction. Replacing S4 with a bulkier threonine also may explain the observed 4-fold loss in affinity.

The model shown in Figure 7c illustrates only one possible structure. In an alternative model, residues 1–38 could form an antiparallel two helix bundle, with a turn between residues 18 and 21 that could lie on one face of the tropomyosin molecule forming a structure similar to a four helix bundle. Such an interface would have fewer hydrophobic interactions between tropomodulin and tropomyosin, but would allow strong salt bridges between residues R10 and R14 of tropomyosin with E33 and E35 of tropomodulin.

The Tmod1109–144 -αTM1bZip complex is also highly helical suggesting formation of an extensive coiled coil interface upon complex formation. Mutagenesis of γTM5NM1 shows that the a and d interface residues L6, V9 and I13 are critical for binding the second Tmod site 20, consistent with a coiled coil interface. Mutagenesis studies have shown that the Tmod1 residues I131 14 and L135 16 are critical for binding. The Tmod1 sequence has a coiled coil periodicity between residues 121 and 135 suggesting it could form a helix that would be long enough to extend into the GCN4 portion of the αTM1bZip molecule. Together with the NMR study showing that the binding site extends into the GCN4 region of αTM1bZip, we suggest that Tmod1109–144 and αTM1bZip form an antiparallel three-helix coiled coil that is interrupted at P114, near the C-terminal end of the GCN4 region. Residues 30 to 36 of the αTM1bZip are unperturbed when Tmod1109–144 binds, suggesting that the residues 109–114 do not bind the peptide. A possible binding scheme for binding αTM1bZip, as well as native αTM1b, and a hypothetical structure for the Tmod1109–144/αTM1bZip complex are shown in Figure 7b,d. The sequence shows some possible interactions; in the three helix bundle the R14 residue is exposed. We stress that Figure 7 illustrates only hypothetical models; we will learn the arrangement of the helices and understand the significance of specific residues only by solving the structures of the complexes.

The position of a single Tmod molecule at the pointed end of the actin filament that forms fundamentally different complexes with the tropomyosin molecules on the two sides of the filament helix augments the asymmetry of the end. Differences in tropomyosin affinity for the two binding sites in Tmod may regulate its correct positioning at the pointed end. Since small sequence variations in the N terminus of tropomyosin can have major affects on Tmod1 binding and the ability to cap the pointed end, the end becomes a significant regulatory site. Tropomyosins are recognized to be a major regulator of the actin filaments in cells, having the ability to protect filaments against severing and branching 21; 22; 23, to recruit specific myosins 24, alter cell shape, and now to regulate the pointed end. Regulation of the cooperativity as well as the effectiveness of capping by specific tropomyosins may have significant consequences for local filament dynamics in cells.

Materials and methods

Protein Expression and Purification

Full-length Tmod1 and Tmod11–344 were overexpressed in E.coli BL21(DE3)pLysE using the method described in 25 and purified according to 26. Tmod11–38 was synthesized by the Keck Facility at Yale University (New Haven, CT). Other Tmod fragments were synthesized by the Tufts University Core Facility (Boston, MA). Chicken pectoral skeletal muscle actin was purified from acetone powder as described 27. G-actin was purified on a Sephacryl S-300 column 28 and was stored in liquid nitrogen. Actin was labeled with pyrenyl-iodoacetamide and the labeling ratios were calculated according to 29; 30. The degree of the labeling was 80 – 99 %. Before experiments, G-actin (labeled or unlabeled) was defrosted in a 37°C water bath and then centrifuged at 100,000 rpm (TLA-100, Beckman) for 30 min at 4°C. γTM5NM1, a short rat γ-tropomyosin, was purified according to 31. TM peptides, αTM1bZip (previously named AcTM1bZip 18), γTM1bZip and δTM1bZip are designed chimeric proteins that contains 19 residues of short α, γ or δ-tropomyosin correspondingly, encoded by exon 1b and the 18 C-terminal residues of the GCN4 leucine zipper domain. The peptides are N-acetylated. These peptides as well as mutated αTM1bZip peptides were synthesized by the Tufts University Core Facility (Boston, MA). 15N-Gly αTM1bZip, used in the NMR studies was expressed and purified as described previously 18. Recombinant human gelsolin was a generous gift from Dr. John H. Hartwig (Brigham and Women’s Hospital & Hematology Division, Boston, MA).

Protein purity was evaluated using SDS-PAGE 32. Concentrations of proteins were determined by using BCA protein assay kit (Pierce) or by measuring their difference spectra in 6 M guanidine-HCl between pH 12.5 and 7.0 33 using the extinction coefficients of 2357 per tyrosine and 830 per tryptophan 34.

Binding Experiments

Binding was visualized using native polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis in 9 % polyacrylamide gels that were polymerized in the presence of 10% glycerol without SDS were used 11. To prepare complexes for loading onto gels, Tmod fragments were mixed with TM peptides in a 1:2 molar ratio.

Fluorescence measurements

The rates of actin polymerization were measured using the change in pyrene actin fluorescence 29 using a PTI fluorimeter (Lawrenceville, NJ) (excitation, 366 nm, and emission, 387 nm, with a 1 nm slit). To measure polymerization of actin at the pointed end, short filaments capped at the barbed ends with gelsolin were prepared by polymerizing 3 µM G-actin in the presence of 15 nM gelsolin according to 19. Polymerization was monitored by the increase in fluorescence when the filaments were diluted 5-fold with G-actin (10 % pyrenylactin) in F-buffer (100 mM KCl, 2 mM MgCl2, 1 mM EGTA, 0.5 mM DTT, 0.2 mM ATP, 0.2 mM CaCl2, 1 mM NaN3, 10 mM imidazole, pH 7.0) containing TM and Tmod1. The final concentrations of F- and G-actin after dilution were 0.6 µM and 1.1 µM respectively.

Gelsolin-capped filaments were prepared in sets of four and fluorescence measurements were carried out in parallel in a four cuvette holder with actin as a control in each set as previously described 19. Exponential curves were fit to the polymerization data using SigmaPlot, and initial rates (R) were calculated as the first derivatives at time zero. The inhibition of polymerization was calculated as Rexp/Rcontrol, where Rcontrol=1 (in the absence of tropomyosin and tropomodulin). To determine at what concentration Tmod11–344 reaches 50% inhibition, the curves from the graph were normalized (inhibition without Tmod11–344 was 0 and maximal Tmod11–344 inhibition was 100 %).

Circular dichroism measurements

CD measurements were made using an Aviv model 215 spectropolarimeter (Lakewood, NJ) as previously described 35; 36. The dissociation constants of the Tmod1/TM peptide complexes, Kd, were determined using the relationship: Kd= exp(−ΔΔG/RT), where ΔΔG is the difference in free energy of folding of the complex minus that of the TM fragment alone, R is the gas constant and T is the temperature 37. The equations used for determining the dissociation constants and the thermodynamics of folding of the two-chain TM peptide and the three-chain TM/Tmod1 peptide complex from the changes in their circular dichroism as a function of temperature are described in detail in 5; 36.

Crosslinking

fragments of Tmod1 and TM were mixed in 10 mM Na-phosphate buffer, pH 7.0, containing 100 mM NaCl. Glutaraldehyde was added to a final concentration of 0.01 %. After incubation for 30 min at room temperature, 100 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, was added to terminate the reaction. Samples were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and quantified using a Molecular Dynamics model 300A computing densitometer (Sunnyvale, CA).

NMR studies

15N-¹H-heteronuclear single quantum coherence (HSQC) NMR spectra of 15N-labeled Gly αTM1bZip in the absence and presence of unlabeled Tmod11–38 and Tmod1109–144 were collected at 10°C at 800 MHz on a Bruker BioSpin NMR spectrometer.

Molecular modeling

Cartoons of the of complexes of Tmod11–38 and Tmod1109–144 with αTM1bZip were constructed using the programs MolMol 38 and Sybyl version 17.2, Tripos Inc. Saint Louis MO. To construct the cartoon of one possible complex between αTM1bZip and Tmod11–38, a four-helix coiled coil, with one chain running antiparallel and three chains running parallel were constructed by taking chains A and C from the X-ray structure of a mutant of GCN4 that forms an antiparallel three-chained coiled coil 39 (PDB 1RB6) and chains A and C from a structure of a mutant of GCN4, which forms a parallel three coiled coil 40 (PDB 1IJ3). The strands were aligned so that the four strands were equidistant from each other and formed a four-helix coiled coil using the program MolMol. Residues 1–16 of the GCN4 sequence from chain A of each mutant were replaced with residues 5–20 from αTM1bZip. The N-terminus was extended with three helical serines and three non-helical residues, Gly-Ala-Gly, at the extreme N-terminus. Residues 1–15 were removed from chain C of 1RB6 and residues 16–32 were replaced with residues 3–19 from Tmod1. M1 and S2 were added at the N-terminus with a random conformation. Residues 1–13 of chain C from 1IJ3 were replaced with residues 26 to 38 of Tmod1 and LTEE were added at the N-terminus.

To construct the cartoon of one possible structure of the Tmod1109–144/ αTM1bZip complex, the antiparallel three-stranded coiled coil from the 1RB6 file was used as a template. The parallel strands, A and B were mutated to the sequence of αTM1bZip as describe above. Residues 1–3 and 33 of the chain C were deleted and residues 4–32 were replaced with residues 116 to 144 of Tmod1 and residues 109 to 115 were added at the N-terminus without constraining the conformation. The energies of the hypothetical structures were minimized using Sybyl.

Figure 4.

Dependence of inhibition of pointed end elongation of gelsolin-capped actin filaments on Tmod11–344 or Tmod11–92 concentration in the presence of 2.5 µM γTM5NM1. Initial rates (R) were calculated as the first derivatives at time zero after fitting exponential growth curves to the data. The inhibition of polymerization was calculated as Rexp / Rcontrol, where Rcontrol=1 (in the absence of tropomyosin and tropomodulin). (●) with Tmod11–344; (○) with Tmod11–92. (■) the value shown for γTM5NM1 in the absence of tropomodulin is 1.15 ± 0.18 (n=3). For comparison initial rates in the presence of 50 nM Tmod11–92 with 0.75 µM αstTM (◆) or 0.5 µM αTM5a (◇) are shown.

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. John Hartwig for recombinant human gelsolin and Dr. Peter Gunning for plasmid for γTM5NM1 expression. We thank Brian Rapp for γTM5NM1 purification, Lucy Kotlyanskaya for 15N-Gly αTM1bZip preparation and Mikhail Gongadze for technical assistance. Supported by the American Heart Association Grant 0535328N and UMDNJ Foundation Grant to Dr. Alla S. Kostyukova and by National Institutes of Health Grants GM63257 to Dr. Sarah E. Hitchcock-DeGregori and GM36326 to Dr. Sarah E. Hitchcock-DeGregori and Dr. Norma Greenfield.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Pollard TD, Borisy GG. Cellular motility driven by assembly and disassembly of actin filaments. Cell. 2003;112:453–465. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00120-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fowler VM. Regulation of actin filament length in erythrocytes and striated muscle. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1996;8:86–96. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(96)80052-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Littlefield R, Almenar-Queralt A, Fowler VM. Actin dynamics at pointed ends regulates thin filament length in striated muscle. Nat Cell Biol. 2001;3:544–551. doi: 10.1038/35078517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gunning PW, Schevzov G, Kee AJ, Hardeman EC. Tropomyosin isoforms: divining rods for actin cytoskeleton function. Trends Cell Biol. 2005;15:333–341. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2005.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Greenfield NJ, Fowler VM. Tropomyosin requires an intact N-terminal coiled coil to interact with tropomodulin. Biophys J. 2002;82:2580–2591. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(02)75600-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chu X, Chen J, Reedy MC, Vera C, Sung KL, Sung LA. E-Tmod capping of actin filaments at the slow-growing end is required to establish mouse embryonic circulation. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2003;284:H1827–H1838. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00947.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ono Y, Schwach C, Antin PB, Gregorio CC. Disruption in the tropomodulin1 (Tmod1) gene compromises cardiomyocyte development in murine embryonic stem cells by arresting myofibril maturation. Dev Biol. 2005;282:336–348. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2005.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fischer RS, Yarmola EG, Weber KL, Speicher KD, Speicher DW, Bubb MR, Fowler VM. Tropomodulin 3 binds to actin monomers. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:36454–36465. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M606315200. Epub 2006 Oct 1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Krieger I, Kostyukova A, Yamashita A, Nitanai Y, Maeda Y. Crystal structure of tropomodulin C-terminal half and structural basis of actin filament pointed-end capping. Biophysical J. 2002;83:2716–2725. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(02)75281-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kostyukova AS, Tiktopula EI, Maeda Y. Folding properties of functional domains of tropomodulin. Biophys J. 2001;81:345–351. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(01)75704-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Greenfield NJ, Kostyukova AS, Hitchcock-Degregori SE. Structure and tropomyosin binding properties of the N-terminal capping domain of tropomodulin 1. Biophys J. 2005;88:372–383. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.104.051128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fowler VM, Greenfield NJ, Moyer J. Tropomodulin contains two actin filament pointed end-capping domains. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:40000–40009. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M306895200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kostyukova A, Rapp B, Choy A, Greenfield NJ, Hitchcock-DeGregori SE. Structural requirements of tropomodulin for tropomyosin binding and actin filament capping. Biochemistry. 2005;44:4905–4910. doi: 10.1021/bi047468p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kostyukova AS, Choy A, Rapp BA. Tropomodulin binds two tropomyosins: a novel model for actin filament capping. Biochemistry. 2006;45:12068–12075. doi: 10.1021/bi060899i. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vera C, Lao J, Hamelberg D, Sung LA. Mapping the tropomyosin isoform 5 binding site on human erythrocyte tropomodulin: Further insights into E-Tmod/TM5 interaction. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2005;444:130–138. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2005.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kong KY, Kedes L. Leucine-135 of tropomodulin-1 regulates its association with tropomyosin, its cellular localization and the integrity o sarcomeres. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:9589–9599. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M512064200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Babcock GG, Fowler VM. Isoform-specific interaction of tropomodulin with skeletal muscle and erythrocyte tropomyosins. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:27510–27518. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Greenfield NJ, Huang YJ, Palm T, Swapna GV, Monleon D, Montelione GT, Hitchcock-DeGregori SE. Solution NMR structure and folding dynamics of the N terminus of a rat non-muscle alpha-tropomyosin in an engineered chimeric protein. J Mol Biol. 2001;312:833–847. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2001.4982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kostyukova AS, Hitchcock-DeGregori SE. Effect of the structure of the N terminus of tropomyosin on tropomodulin function. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:5066–5071. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M311186200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vera C, Sood A, Gao KM, Yee LJ, Lin JJ, Sung LA. Tropomodulin-binding site mapped to residues 7–14 at the N-terminal heptad repeats of tropomyosin isoform 5. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2000;378:16–24. doi: 10.1006/abbi.2000.1802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bernstein BW, Bamburg JR. Tropomyosin binding to F-actin protects the F-actin from disassembly by brain actin-depolymerizing factor (ADF) Cell Motil. 1982;2:1–8. doi: 10.1002/cm.970020102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.DesMarais V, Ichetovkin I, Condeelis J, Hitchcock-DeGregori SE. Spatial regulation of actin dynamics: a tropomyosin-free, actin-rich compartment at the leading edge. J Cell Sci. 2002;115:4649–4660. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Blanchoin L, Pollard TD, Hitchcock-DeGregori SE, Sampath P. Inhibition of the Arp2/3 complex-nucleated actin polymerization and branch formation by tropomyosin. Curr Biol. 2001;11:1300–1304. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(01)00395-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gupton SL, Anderson KL, Kole TP, Fischer RS, Ponti A, Hitchcock-DeGregori SE, Danuser G, Fowler VM, Wirtz D, Hanein D, Waterman-Storer CM. Cell migration without a lamellipodium: translation of actin dynamics into cell movement mediated by tropomyosin. J Cell Biol. 2005;168:619–631. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200406063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Studier FW. Protein production by auto-induction in high density shaking cultures. Protein Expr Purif. 2005;41:207–234. doi: 10.1016/j.pep.2005.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kostyukova A, Yamauchi E, Maeda K, Krieger I, Maeda Y. Domain structure of tropomodulin: distinct properties of the N-terminal and C-terminal halves. Eur J Biochem. 2000;267:6470–6475. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.2000.01738.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Spudich JA, Watt S. The regulation of rabbit skeletal muscle contraction. I. Biochemical studies of the interaction of the tropomyosin-troponin complex with actin and the proteolytic fragments of myosin. J Biol Chem. 1971;246:4866–4871. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.MacLean-Fletcher S, Pollard TD. Identification of a factor in conventional muscle actin preparations which inhibits actin filament self-association. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1980;96:18–27. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(80)91175-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kouyama T, Mihashi K. Fluorimetry study of N-(1-pyrenyl)iodoacetamide-labelled F-actin. Local structural change of actin protomer both on polymerization and on binding of heavy meromyosin. Eur J Biochem. 1981;114:33–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cooper JA, Walker SB, Pollard TD. Pyrene actin: documentation of the validity of a sensitive assay for actin polymerization. J Muscle Res Cell Motil. 1983;4:253–262. doi: 10.1007/BF00712034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Moraczewska J, Nicholson-Flynn K, Hitchcock-DeGregori SE. The ends of tropomyosin are major determinants of actin affinity and myosin subfragment 1-induced binding to F-actin in the open state. Biochemistry. 1999;38:15885–15892. doi: 10.1021/bi991816j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Laemmli UK. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature. 1970;227:680–685. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Edelhoch H. Spectroscopic determination of tryptophan and tyrosine in proteins. Biochemistry. 1967;6:1948–1954. doi: 10.1021/bi00859a010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fasman GD. Practical handbook of biochemistry and molecular biology. Boca Raton, Florida: CRC Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Greenfield NJ, Hitchcock-DeGregori SE. The stability of tropomyosin, a two-stranded coiled-coil protein, is primarily a function of the hydrophobicity of residues at the helix-helix interface. Biochemistry. 1995;34:16797–16805. doi: 10.1021/bi00051a030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Greenfield NJ, Montelione GT, Farid RS, Hitchcock-DeGregori SE. The structure of the N-terminus of striated muscle alpha-tropomyosin in a chimeric peptide: nuclear magnetic resonance structure and circular dichroism studies. Biochemistry. 1998;37:7834–7843. doi: 10.1021/bi973167m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Greenfield NJ. Circular dichroism analysis for protein-protein interactions. Methods Mol Biol. 2004;261:55–78. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-762-9:055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Koradi R, Billeter M, Wuthrich K. MOLMOL: a program for display and analysis of macromolecular structures. J Mol Graph. 1996;14:51–55. 29–32. doi: 10.1016/0263-7855(96)00009-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Holton J, Alber T. Automated protein crystal structure determination using ELVES. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:1537–1542. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0306241101. Epub 2004 Jan 29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Akey DL, Malashkevich VN, Kim PS. Buried polar residues in coiled-coil interfaces. Biochemistry. 2001;40:6352–6360. doi: 10.1021/bi002829w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Landschulz WH, Johnson PF, McKnight SL. The leucine zipper: a hypothetical structure common to a new class of DNA binding proteins. Science. 1988;240:1759–1764. doi: 10.1126/science.3289117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]