Abstract

Parathyroid hormone-related protein (PTHrP) increases the growth and metastatic potential of prostate cancer cells, making it important to control PTHrP expression in these cells. 1,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D3 [1,25(OH)2D3] suppresses PTHrP expression and exerts an anti-proliferative effect in prostate carcinoma cells. We used the human prostate cancer cell line C4-2 as a model system to ask whether down-regulation of PTHrP expression by 1,25(OH)2D3 plays a role in the anti-proliferative effects of 1,25(OH)2D3. Since PTHrP increases the expression of the pro-invasive integrin α6β4, we also asked whether 1,25(OH)2D3 decreases integrin α6β4 expression in C4-2 cells, and whether modulation of PTHrP expression by 1,25(OH)2D3 plays a role in the effects of 1,25(OH)2D3 on integrin α6β4 expression. Two strategies were utilized to modulate PTHrP levels: overexpression of PTHrP (−36 to +139) and suppression of endogenous PTHrP expression using siRNAs. We report a direct correlation between PTHrP expression, C4-2 cell proliferation, and integrin α6β4 expression at the mRNA and cell surface protein level. Treatment of parental C4-2 cells with 1,25(OH)2D3 decreased cell proliferation and integrin α6 and β4 expression. These 1,25(OH)2D3 effects were significantly attenuated in cells with suppressed PTHrP expression. 1,25(OH)2D3 regulates PTHrP expression via a negative vitamin D response element (nVDRE) within the noncoding region of the PTHrP gene. The effects of 1,25(OH)2D3 on cell proliferation and integrin α6β4 expression were significantly attenuated in cells overexpressing PTHrP (−36 to +139), which lacks the nVDRE. These findings suggest that one of the pathways via which 1,25(OH)2D3 exerts its anti-proliferative effects is through down-regulation of PTHrP expression.

Keywords: Steroids; PTHrP; 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D; integrin α6β4; prostate cancer

Introduction

Prostate cancer is the most common solid tumor in American men and the second leading cause of cancer death. The incidence of prostate cancer is rising annually (1). Nearly 70% of prostate cancer patients develop bone lesions, and skeletal metastasis is a major cause of morbidity (2). The prostate is highly dependent on androgens for normal developmental and physiological functions. However, additional factors, including growth factors, neuroendocrine peptides, and cytokines also play important roles in this organ (3); one of these factors is parathyroid hormone-related protein (PTHrP). PTHrP was initially identified through its role in humoral hypercalcemia of malignancy, one of the most frequent paraneoplastic syndromes (4). Subsequently, PTHrP was found to be widely distributed in most fetal and adult tissues, including the prostate. PTHrP has been localized to normal neuroendocrine cells and the glandular epithelium of normal and benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) tissues (5, 6). Cultured epithelial cells derived from normal and BPH tissues, and immortalized prostate cancer cell lines secrete PTHrP (7, 8). The progression of normal prostate epithelium to BPH and then to carcinoma is accompanied by an increase in PTHrP expression (9, 10). Several studies have demonstrated that PTHrP contributes to the pathogenesis and progression of prostate carcinoma and its preference to metastasize to bone (11,12). It is therefore clinically relevant to develop agents that control PTHrP production by these cells.

Vitamin D deficiency has been linked with increased prostate cancer incidence (reviewed in 13). 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 (1,25(OH)2D3), the hormonally active form of vitamin D, inhibits cell proliferation in many cancer cell types, including prostate carcinoma cells (14–16). We and others have shown that PTHrP increases prostate cancer cell proliferation (17, 18). Here we asked whether down-regulation of PTHrP expression by 1,25(OH)2D3 plays a role in the observed effects of 1,25(OH)2D3 on cell proliferation. The C4-2 cell line, an androgen independent, second generation LNCaP subline which metastasizes to lymph nodes and bone when injected into nude mice (19), was used as a model system. C4-2 cells produce mixed lytic/blastic lesions (20), thereby mimicking the in vivo situation.

PTHrP increases the expression of the pro-invasive integrin α6β4 in multiple cell lines (21–23). Integrin α6β4 is an adhesion receptor for most of the known laminins, and contributes to the malignant functions of carcinoma cells (24, 25). 1,25(OH)2D3 decreases integrin α6 and β4 expression in prostate cancer cells (26). Therefore, we also asked whether down-regulation of PTHrP expression by 1,25(OH)2D3 plays a role in the observed effects of 1,25(OH)2D3 on integrin α6 and β4 levels.

Experimental

Materials

1,25(OH)2D3 was provided by Dr. M. Uskokovic (Hoffmann La-Roche, Nutley, New Jersey, USA), and was dissolved in ethanol at 10−4 M. Fetal bovine serum (FBS) and dialyzed FBS were obtained from Atlanta Biologicals (Norcross, GA). The phycoerythrin-conjugated anti-integrin α 6 and β4 antibodies, and their isotype controls were obtained from BD PharMingen (San Diego, CA). The unconjugated anti-integrin α6 and β4 antibodies and the GAPDH antibody were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA). The siRNAs targeting PTHrP and the corresponding non-specific siRNAs were purchased from Dharmacon (Lafayette, CO).

Plasmid constructs

A cDNA encoding human PTHrP (Genentech, South San Francisco, CA, USA) was cloned into pEGFP-N1 (Clontech, Mountain View, CA). Two independent PTHrP siRNA sequences (GAGCUGUGUCUGAACAUCAUU and GAUCGCAGAAAUCCACAC AUU) targeting the open reading frame of the human PTHrP gene were each cloned into pSilencer 2.1 U6 neo (Ambion, Austin, TX). Similarly cloned scrambled siRNA sequences served as controls. All constructs were transfected into C4-2 cells by electroporation.

Cell culture and transfection

C4-2 cells were purchased from UroCor (Oklahoma City, OK) and were grown at 37 °C in humidified 95% air/5% CO2 in RPMI 1640 medium containing 10% FBS and L-glutamine. In some experiments conventional FBS was replaced with dialyzed FBS to minimize cell exposure to endogenous steroids present in serum. After transfection, individual clones were isolated as described (23).

Treatment with 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3

To measure the effects of 1,25(OH)2D3 on cell proliferation and on PTHrP and integrin expression, cells were maintained in medium containing 10% dialyzed FBS for 4 days. The cells were then treated with the indicated concentrations of 1,25(OH)2D3 for the indicated time intervals. Control cells received an equivalent volume of vehicle (ethanol; 0.01% final concentration).

Analysis of PTHrP and integrin expression

PTHrP secretion was measured using an immunoradiometric assay (IRMA; DSL, Webster, TX) (18). Expressed mRNAs were measured by reverse transcription/real-time PCR analysis, and cell surface integrin α6 and β4 protein levels in PTHrP siRNA transfectants were measured by Fluorescence-Activated Cell Sorting (FACS) analysis. Since the presence of Green Fluorescent Protein (GFP) interfered with FACS analysis, integrin levels in PTHrP-overexpressing cells were analyzed by Western blot analysis.

Real-time Polymerase Chain Reaction Analysis of PTHrP, Integrin α6, and Integrin β4 Gene Expression

Total RNA from C4-2 cells was extracted using the RNAqueous® isolation kit (Ambion Inc.), per the manufacturer’s protocol. RNA concentrations were determined by spectrophotometry.

Relative quantification of gene expression

Separate tube (singleplex) real-time PCR was performed using 0.5 μg of RNA as template to detect PTHrP, integrin α6 and integrin β4 mRNA transcripts and 18S rRNA (endogenous control for normalization purposes). PTHrP primers (Assays-on-Demand™, P/N 4331182, 20X assay mix of primers), the PTHrP TaqMan MGB probe (FAM™ dye-labeled, PTHLH (parathyroid hormone-like hormone), NM 002820, Hs00174969 m1: CGCCGCCTCAAAAGAGCTGTGTCTG), integrin α6 primers (ITGA6, NM 000210, X59512, X53586, BC007002 Hs00173952_m1 AAGCGGCTGTTGCTCGTGGGGGCCC), integrin β4 primers (ITGB4, NM_001005619, NM_001005731, NM_000213, X51841, X52186, AF011375, Hs00173995_m1 GGTTCCTCTGCAATGACCGAGGACG) and the pre-developed 18S rRNA primers (VIC™-dye labeled probe, TaqMan® assay reagent, P/N 4319413E) were obtained from Applied Biosystems, as was the universal PCR master mix reagent kit (P/N 4304437). The cycling parameters for real-time PCR were: UNG activation at 50 °C for 2 min, AmpliTaq activation at 95 °C for 10 min, then denaturation at 95 °C for 15 sec and annealing/extension at 60 °C for 1 min (repeated 40 times) on an ABI7000 real-time PCR machine. Duplicate CT values were analyzed in Microsoft Excel using the comparative CT (ΔΔCT) method as described by the manufacturer (Applied Biosystems). The amount of target (2−ΔΔCT) was obtained by normalization to the endogenous reference (18S). Real-time PCR was performed using the facilities of UTMB’s Sealy Center for Cancer Cell Biology’s Real-Time PCR core facility; http://www.utmb.edu/scccb/pcr/index.htm. As negative controls, we carried out PCR reactions without RNA.

FACS analysis

The cell surface expression of the integrin α6 and β4 subunits was measured by staining cells with the phycoerythrin-labeled antibodies to these subunits. As control, cells were stained with the respective isotype control antibodies. For these experiments, 2 × 105 cells were trypsinized, washed with PBS, and incubated on ice with the specific antibody for 20 min. The cells were then washed twice with PBS containing 2% newborn calf serum (NCS) and 0.02% sodium azide, and the mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) was measured with a FACS Scan flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson and Co., Franklin Lakes, NJ). Viable cells were electronically gated using forward and side scatter parameters. Relative integrin expression was calculated after subtracting the log MFI of the corresponding isotype control antibody-stained cells. Flow cytometry data were analyzed using the CellQuest program (Becton Dickinson and Co.).

Western blot analysis

Cells were grown to 70–80% confluence in 100 mm dishes. For whole cell extracts, cells were washed twice with cold PBS on ice and lysed in RIPA buffer containing a Protease Inhibitor cocktail (Santa Cruz Biotechnology). To enrich for cytosol and membrane fractions, cells were washed and lyzed as described for whole cells extracts. The cell lysates were centrifuged twice at 1000 × g for 5 min at 4 °C. The supernatants from each step were pooled and centrifuged at 13,000 × g for 30 min at 4 °C. The supernatant (cytosol fraction) was collected, and the membrane material in the pellet was resuspended in 1:1 RIPA buffer and MB-EGTA (210 mM mannitol, 70 mM sucrose, 0.5 mM EGTA, 10 mM HEPES) (27). Total protein was estimated using the Bio-Rad protein assay.

For Western analysis, 60 μg of protein were resolved on 8% SDS polyacrylamide gels and subsequently transferred to nitrocellulose membranes (Schleicher & Schuell BioScience, Sanford, ME). The membranes were incubated with the anti-integrin α6 or β4 antibodies(Santa Cruz Biotechnology) diluted in blocking buffer [5% non-fat dry milk in TBST]. After three washes in TBST, the membranes were incubated with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies (Santa Cruz Biotechnology). The signals were detected using the SuperSignal West Pico Substrate kit (Pierce Biotechnology, Rockford, IL). The membranes were then stripped with Restore Western Blot Stripping buffer (Pierce), washed 4 times with TBST buffer, and re-probed with an anti-GAPDH monoclonal antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology).

Cell Proliferation

Cell proliferation was measured using the Quick Cell Proliferation Assay kit (Biovision Inc., Mountain View, CA). Cells (1 × 104) were plated in 96-well dishes in a final volume of 100 μl/well of medium containing 10% FBS. At various time points (24 to 96 h), WST-1/ECS solution (20 μl), prepared by dissolving the WST-1 reagent with Electro-Coupling solution (ECS), was added to each well. After incubating at 37 °C in a humidified 95% O2-5% CO2 atmosphere for 1 h, the plates were shaken thoroughly for 1 min, and absorbance was measured using a SpectraMax M2 microplate reader (Molecular Devices Corporation, Sunnyvale, CA) at 450 nm. Culture medium plus WST-1/ECS solution was used as the empty blank control.

Statistics

Numerical data are presented as the mean ± SEM. Data were analyzed by ANOVA, followed by a Bonferroni post-test to determine the statistical significance of differences. All statistical analyses were performed using Instat Software (GraphPad Software, Inc., San Diego, CA).

Results

PTHrP up-regulates integrin α6 and β4 expression

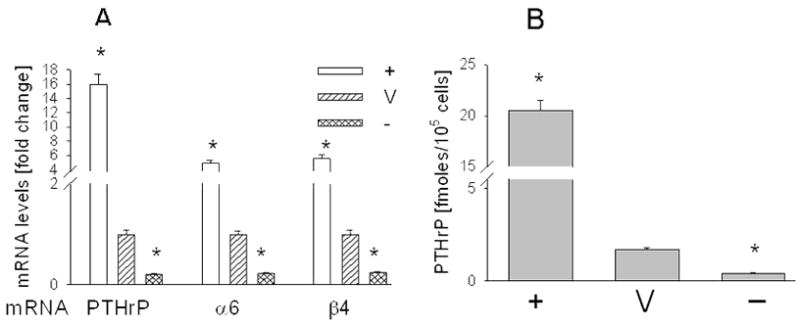

To measure the effects of PTHrP on integrin α6 and β4 expression, we modulated PTHrP expression in C4-2 cells using two strategies: PTHrP-overexpressing cells were established by stable transfection with a PTHrP (−36 to +139) expression vector, and suppression of PTHrP expression was achieved by stable transfection with a construct expressing an siRNA targeting the open reading frame of the human PTHrP gene. For PTHrP-overexpressing cells, the data presented were obtained using three independent clones. In these cells, PTHrP was expressed as a PTHrP-GFP fusion protein, to allow visualization of the subcellular localization of PTHrP. To eliminate site-specific effects of the PTHrP siRNA, two siRNA sequences targeting different regions of the PTHrP gene were used to generate two independent cell lines with suppressed PTHrP expression. Transfection with these constructs produced the expected changes in PTHrP mRNA and secreted protein levels (Fig. 1, A and B). In PTHrP-overexpressing cells, PTHrP was localized in both cytosolic and nuclear compartments (data not shown). As control, cells were transfected with the empty vector or with constructs expressing the scrambled siRNA sequences.

Figure 1. Characterization of C4-2 cells overexpressing PTHrP (−36 to +139) or with suppressed PTHrP expression.

(A) PTHrP and integrin α6 and β4 mRNA levels were measured by reverse transcription-real-time PCR, as described in Materials and Methods. Values are expressed relative to the corresponding V value, set arbitrarily at 1.0. (B) Secreted PTHrP levels, measured using an immunoradiometric assay. + = PTHrP-overexpressing cells; V = empty vector or scrambled siRNA transfectants; − = PTHrP siRNA transfectants. Each bar is the mean ± SEM of three independent experiments for each of three individual PTHrP-overexpressing clones (+), or each of two C4-2 cell lines transfected with PTHrP siRNA-expressing constructs (−). The V bar is the mean ± SEM of three independent experiments with pEGFP-N1 (empty vector) or the pSilencer 2.1 U6 neo/scrambled siRNA constructs. * = Significantly different from V (P < 0.001).

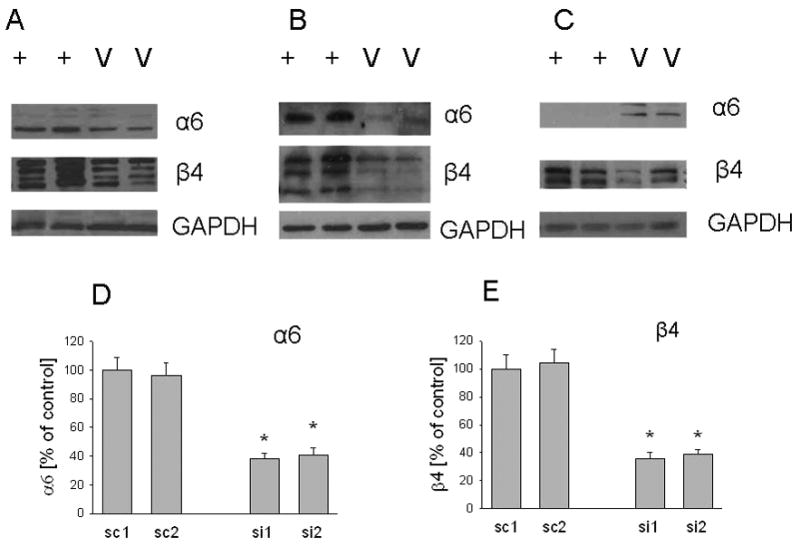

We observed that increasing PTHrP expression results in elevated integrin α6 and β4 mRNA levels. Conversely, decreasing PTHrP expression results in decreased integrin α6 and β4 mRNA levels (Fig. 1A). Integrins exert their biological effects at the cell surface membrane. Integrin α6 and β4 protein levels in PTHrP-overexpressing cells co-expressing GFP were measured by Western blot analysis, since the GFP fluorescence interferes with FACS. Overexpressing PTHrP in C4-2 cells produced a significant increase in the total cellular and membrane protein levels of these integrins when compared to control cells (Fig. 2, A and B). Since the integrin β4 subunit undergoes proteolytic processing (28, 29), multiple bands are evident (Fig. 2, A and B). The cytosol fraction contains fewer post-translational products (Fig. 2C). Interestingly, in extracts enriched in the cytosolic fraction, integrin β4 levels are still elevated in PTHrP-overexpressing vs. control cells. However, integrin α6 levels are lower (Fig. 2C). Transfection with the PTHrP siRNA-expressing construct significantly decreased integrin α6 and β4 cell surface protein levels to ~ 40% of control (Fig. 2, D and E), as measured by FACS. In all FACS analysis data, there was no significant difference in the MFI of the siRNA and scrambled RNA transfectants stained with the isotype control antibodies (data not shown).

Figure 2. Integrin α6 and β4 protein levels in C4-2 cells overexpressing PTHrP (−36 to +139) or with suppressed PTHrP expression.

Levels of the integrin α6 and β4 subunits in whole cell (A), membrane (B), and cytosol (C) fractions from PTHrP-overexpressing and control cells. Data for two individual PTHrP-overexpressing (+) and empty vector-transfected (V) clones are presented. Each figure is representative of three independent experiments. (D and E). Cell surface protein expression of integrins α6 and β4 in cells transfected with one of two independent PTHrP siRNA expression vectors (si1 and si2). Control cells were transfected with a construct expressing the relative scrambled siRNA sequence (sc1 and sc2). Cells were incubated with phycoerythrin-conjugated anti-integrin α 6 or anti-integrin β antibodies, and analyzed by4 FACS as described in Materials and Methods. Each value is expressed relative to the sc value, set at 100%, after subtracting the isotype control background value. Each bar is the mean ± SEM of three independent experiments. * = Significantly different from sc (P < 0.001).

PTHrP expression is required for the 1,25(OH)2D3 –mediated down-regulation of integrin α6 and β4 expression

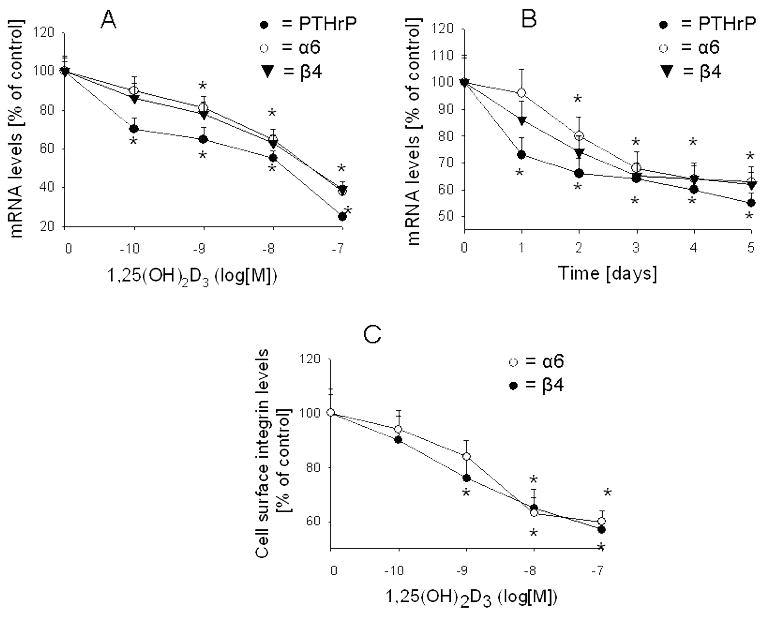

Fig. 3, A and B shows that treatment with 1,25(OH)2D3 produces a concentration- and time-dependent decrease in integrin α6 and β4 mRNA levels. The decrease in integrin mRNA levels lags behind that of PTHrP; while PTHrP mRNA levels were significantly decreased after a 24 h treatment with 10−8 M 1,25(OH)2D3, no significant effect on integrin α6 and β4 levels was observed until 48 h of treatment (Fig. 3B). Down-regulation of integrin α6 and β4 mRNA levels is accompanied by a decrease in the cell surface protein expression (Fig. 3C).

Figure 3. Effect of 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 on PTHrP, integrin α6, and integrin β4 expression in C4-2 cells.

(A) Cells cultured in medium containing 10% dialyzed FBS were treated with the indicated concentrations of 1,25(OH)2D3 for 4 days. (B) Cells cultured in 10% dialyzed FBS were treated with 10−8 M 1,25(OH)2D3 for the indicated time intervals (days). In (A and B), PTHrP, integrin α6 and integrin β4 mRNA levels were measured by reverse transcription/real-time PCR as described in Materials and Methods. (C) Cell surface protein expression of the integrin α6 and β4 subunits in cells cultured in 10% dialyzed FBS and treated with 10−8 M 1,25(OH)2D3 for 4 days. Cells were stained with phycoerythrin-conjugated antibodies against the α6 or β4 integrins, and analyzed by FACS as described in Materials and Methods. Each value is expressed as a percentage of the corresponding value in cells treated with ethanol (vehicle control; set at 100%). Each point is the mean ± SEM of three independent experiments. * = Significantly different from the corresponding vehicle control value (P < 0.001).

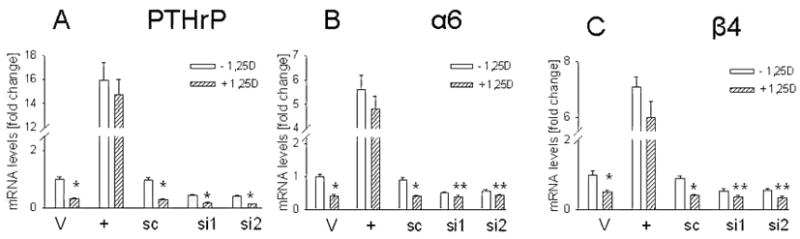

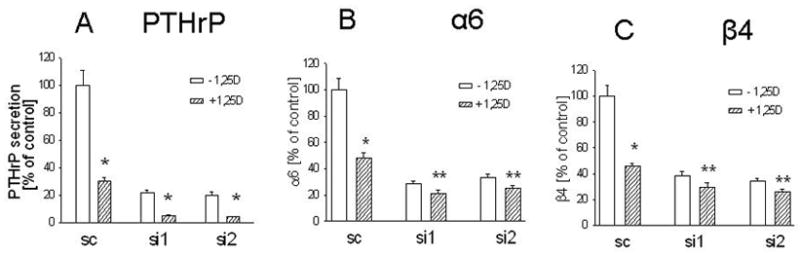

Since 1,25(OH)2D3 down-regulates PTHrP expression, and PTHrP up-regulates integrin α6 and β4 expression, we asked whether down-regulating PTHrP expression by 1,25(OH)2D3 plays a role in the observed effects of this compound on integrin expression. 1,25(OH)2D3 (10−8 M) produced a significant and comparable decrease in PTHrP mRNA levels (Fig. 4A) and secretion (Fig. 5A) in cells with suppressed PTHrP expression and in control cells (~ 65% decrease), indicating that this steroid produces comparable decreases in target protein levels when these proteins are expressed at differing levels in the cell, as is the case in PTHrP siRNA and scrambled siRNA transfectants. However, the 1,25(OH)2D3 - mediated decrease in integrin mRNA levels was significantly lower in PTHrP siRNA transfectants (~ 25% decrease) than in control cells (~ 65% decrease) (Fig. 4, B and C). Similarly, treatment with 1,25(OH)2D3 produced a significantly greater decrease in cell surface integrin α6 and β4 expression in control cells (~ 65% decrease) than in PTHrP siRNA transfectants (~ 20% decrease) (Fig. 5, B and C). Differences in the response of PTHrP siRNA transfected and control cells to 1,25(OH)2D3 were also observed at concentrations of 10−10 M and 10−9 M (data not shown).

Figure 4. Effect of 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 on PTHrP (A), integrin α6 (B), and integrin β4 (C) mRNA levels in C4-2 cells with enhanced or suppressed PTHrP expression.

Cells cultured in medium containing 10% dialyzed FBS were treated with 10−8 M 1,25(OH)2D3 for 4 days. + = overexpressing PTHrP; V = empty vector transfectants; si1 and si2 = transfected with each of two independent PTHrP siRNA expression vectors; sc = transfected with a scrambled siRNA expression vector. Treated with: + 1,25D = 1,25(OH)2D3, − = ethanol (vehicle control). Each value is expressed relative to the V value (empty vector transfectants treated with ethanol), set at 1.0. Each bar is the mean ± SEM of three independent experiments. Significantly different from the corresponding control (−1,25D) value at: * = P < 0.001, and ** = P < 0.05.

Figure 5. Effect of 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 on secreted PTHrP levels (A) and on integrin α6 (B) and integrin β4 (C) cell surface protein expression in C4-2 cells with suppressed PTHrP expression.

Cells cultured in medium containing 10% dialyzed FBS were treated with 10−8 M 1,25(OH)2D3 for 4 days. (A) Secreted PTHrP was measured by an immunoradiometric assay. (B and C) Cells were stained with phycoerythrin-conjugated antibodies against the α6 or β 4 integrins, and analyzed by FACS, as described in Materials and Methods. Transfected with: si1 and si2 = PTHrP siRNA-expressing constructs; sc = scrambled siRNA expression vector. 1,25D = 1,25(OH)2D3. Each value is expressed as a percentage of the corresponding level in cells treated with ethanol (set at 100%). Each bar is the mean ± SEM of three independent experiments. Significantly different from the corresponding control (−1,25D) value at: * = P < 0.001, and ** = P < 0.05.

To further address the role of PTHrP in the 1,25(OH)2D3 -mediated down-regulation of integrin α6 and β4 expression, C4-2 cells overexpressing PTHrP (−36 to +139) were treated with 1,25(OH)2D3. Down-regulation of PTHrP expression by 1,25(OH)2D3 is mediated via a negative vitamin D response element (nVDRE) at position −546 to −517 relative to the transcriptional start site of the PTHrP gene (30,31). Since this and other promoter elements are not present within the transfected PTHrP sequence, PTHrP expression is not regulated by 1,25(OH)2D3 in cells overexpressing this PTHrP isoform (Fig. 4A). In control (vehicle-treated) cells, 1,25(OH)2D3 produced a concentration-dependent decrease of 60% to 70% in PTHrP mRNA levels (Fig. 4A, data not shown). This was accompanied by an ~ 60% decrease in integrin α6 and β4 mRNA levels (Fig. 4, B and C). However, under the same conditions, the effect of 1,25(OH)2D3 on integrin α6 and β4 expression in PTHrP-overexpressing cells was significantly attenuated (~10% to 15% decrease, Fig. 4, B and C). Therefore, these data re-enforce those obtained with the PTHrP siRNA transfectants, and show that regulation of PTHrP expression by 1,25(OH)2D3 plays a major role in the regulation of integrin α6 and β4 expression by 1,25(OH)2D3.

PTHrP plays a role in the anti-proliferative effects of 1,25(OH)2D3

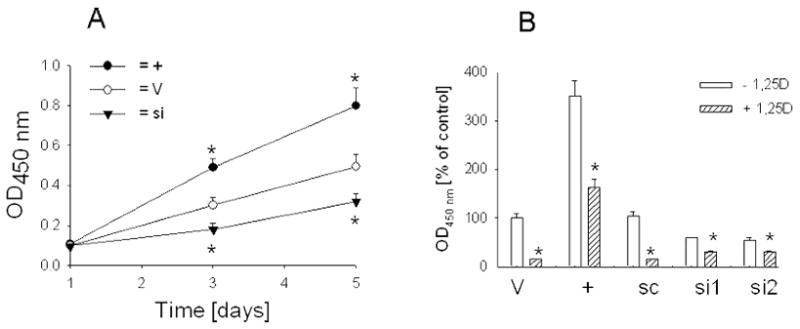

We observed a direct correlation between PTHrP expression and C4-2 cell proliferation, measured over a 5-day period (Fig. 6A). Conversely, 1,25(OH)2D3 decreases C4-2 cell proliferation [Fig. 6B; (32)]. However, this compound exerts a significantly smaller effect on the proliferation of C4-2 cells transfected with the PTHrP siRNA (Fig. 6B). Thus, a 5-day treatment with 10−8 M 1,25(OH)2D3 decreased the proliferation of scrambled siRNA-transfected cells to 15% of control (Fig. 6B). The proliferation rate of cells transfected with the PTHrP siRNA was decreased to only 60% of control (Fig. 6B).

Figure 6.

(A) Proliferation of C4-2 cells with enhanced or suppressed PTHrP expression. Cells (1 × 104) were plated in 96-well dishes in medium containing 10% FBS. Cell proliferation was measured at the indicated time intervals [in days] as described in Materials and Methods, and is expressed as Absorbance450 nm. + = PTHrP-overexpressing cells; V = cells transfected with the empty vector or the scrambled siRNA expression vector; si = PTHrP siRNA-transfected cells. Where no error bar is shown, the SEM is smaller than the symbol. (B) Effect of 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 on the proliferation of C4-2 cells with increased or suppressed PTHrP expression. Cells cultured in medium containing 10% dialyzed FBS were treated for 72 h with 10−8 M 1,25(OH)2D3. Cells (1 × 104) were then plated in 96-well dishes in the presence of 10−8 M 1,25(OH)2D3 for a further 48 h. Cell proliferation was measured as in (A), and is expressed as a percentage of the proliferation of empty vector transfectants. + = overexpressing PTHrP; V = empty vector transfectants; si1 and si2 = PTHrP siRNA transfected; sc = transfected with a scrambled siRNA expression vector. + 1,25D = treated with 1,25(OH)2D3, − = treated with ethanol (vehicle control). (A and B). For PTHrP-overexpressing cells, each point or bar is the mean ± SEM of three independent experiments for each of three independent clones. For PTHrP siRNA transfectants, each point or bar is the mean ± SEM of three independent transfections for each of two individual PTHrP siRNA-expressing constructs. * = Significantly different from the corresponding vehicle control value (P < 0.001).

As presented in Fig. 4A, 1,25(OH)2D3 does not down-regulate transfected PTHrP (−36 to +139) expression in C4-2 cells. Here we also investigated the effect of 1,25(OH)2D3 on the proliferation of cells overexpressing PTHrP (−36 to +139). Treatment of control cells with 10−8 M 1,25(OH)2D3 for 5 days decreased cell proliferation to ~ 15% of control (Fig. 6B). Under the same conditions, the proliferation of PTHrP-overexpressing cells by 1,25(OH)2D3 was only decreased to ~ 60% of control (Fig. 6B).

Discussion

There is considerable evidence supporting a link between vitamin D deficiency and an increased incidence of prostate cancer (reviewed in 13). 1,25(OH)2D3, the hormonally active form of vitamin D, regulates cell growth and differentiation (33). Pathways which contribute to the anti-proliferative effects include the induction of cell cycle arrest through increased p21 and p27 expression, and regulation of growth factors such as insulin-like growth factor binding protein-3, transforming growth factor-β and cyclooxygenase-2 (34–37). 1,25(OH)2D3 also inhibits tumor cell migration, metastasis, and angiogenesis (34, 35).

We and others have shown that PTHrP increases the proliferation of cell lines derived from various tissues, including prostate cancer (17, 18, 22, 38). Conversely, 1,25(OH)2D3 inhibits cell proliferation (14–16) and decreases PTHrP expression at both the mRNA and secreted protein level (16, 32). Our study demonstrates that one of the pathways via which 1,25(OH)2D3 exerts its anti-proliferative effects is through down-regulation of PTHrP expression, since the anti-proliferative effects of 1,25(OH)2D3 are significantly attenuated in cells with suppressed PTHrP expression and in cells where the transfected PTHrP is not under 1,25(OH)2D3 regulation. PTHrP may act as an intermediate in the observed effects of 1,25(OH)2D3 on cell cycle control, and may exert its effects either directly and/or indirectly by regulating proteins that are known to affect cell proliferation, such as p21, p27, and transforming growth factor-β (35, 37).

In this and previous studies (21–23), we show a direct correlation between PTHrP, and integrin α6 and β4 expression at both the mRNA and cell surface protein level. Integrins are comprised of αβ heterodimers that function as transmembrane receptors. They play a major role in cancer cell behavior, and activate intracellular signaling pathways that regulate cell proliferation, differentiation, apoptosis, motility, and gene expression (39, 40). Integrin α6β4 expression has been linked to the progression of breast, thyroid, bladder, colorectal, and gastric tumors, among others (41). Relatively less is known about the role of integrin α6β4 role in prostate cancer, although it has been shown that decreased expression of this integrin is associated with reduced adhesion to laminin, and suppressed Matrigel invasion (42). Since integrin α6β4 exerts a positive effect on cell proliferation (43, 44), the PTHrP-mediated up-regulation of integrin expression by PTHrP may play an important role in the observed proliferative effects of PTHrP. In support of this, it has been shown that β4 signaling promotes ErbB2-mediated mammary tumor cell proliferation (45), and that ErbB2 is required for C4-2 cell growth (46). In addition, 1,25(OH)2D3 decreases ErbB2 activity in C4-2 cells (47).

We observed that the increase in membrane-associated integrin α6 expression in PTHrP-overexpressing cells is accompanied by a decrease in cytosolic levels. Integrin β4 expression is elevated at both the membrane and cytosol level. The PTHrP-mediated increase in integrin α6β4 cell surface protein expression may thus primarily result from up-regulation by PTHrP of the β4 subunit. The increased cell surface α6 levels in PTHrP-overexpressing cells may be dependent on α6 mobilization through heterodimerization with β4. However, PTHrP also up-regulates integrin α6 and β4 mRNA levels, indicating a direct and/or indirect effect of PTHrP at the transcriptional and/or post-transcriptional level for both subunits.

We also report a direct link between 1,25(OH)2D3, PTHrP and integrin α6β4 expression. 1,25(OH)2D3 significantly decreases integrin α6β4 expression in parental C4-2 cells. This effect is significantly attenuated in cells with suppressed PTHrP expression, indicating that down-regulation of PTHrP expression by 1,25(OH)2D3 plays a major role in the observed effects of 1,25(OH)2D3 on integrin α6 and β4 expression. In support of this, the 1,25(OH)2D3 -mediated down-regulation of integrin α6 and β4 mRNA levels in DU145 and PC-3 cells shows a delayed time-course profile, implying an indirect mechanism of action (26). These data indicate that inhibition of integrin α6 and β4 expression by 1,25(OH)2D3 occurs downstream of PTHrP inhibition - PTHrP is first down-regulated by 1,25(OH)2D3, leading to a decrease in integrin α6 and β4 levels. These observations do not preclude a direct role for 1,25(OH)2D3 in the regulation of one or both of these integrins. In support, we observe that 1,25(OH)2D3 does decrease integrin α6 and β4 expression in PTHrP siRNA transfectants.

Prostate cancer has a high propensity to metastasize to bone and PTHrP expression by prostate cancer cells facilitates this process (11, 12). Prostate cancer metastasis to the bone is comprised of an initial osteolytic phase, followed by a transition phase and an osteoblastic phase (20, 48, 49). Since PTHrP plays a positive role in both processes (20, 49), down-regulating PTHrP expression effectively inhibits both the lytic and blastic phases of prostate cancer metastasis to the bone. During the osteolytic phase, PTHrP also mediates the release from the bone matrix of growth factors, which in turn provide a major stimulus for cancer cell proliferation (50). Integrin α6β4 also enhances cancer cell migration, invasion and metastasis in vitro and in vivo (42, 51). Since these integrins are regulated downstream of PTHrP, they likely also contribute to the PTHrP-mediated pathogenesis and progression of prostate and other cancers. These studies therefore stress the potential clinical significance of the observed attenuation of PTHrP expression by 1,25(OH)2D3.

In conclusion, in this study we show that one of the pathways via which 1,25(OH)2D3 exerts its anti-proliferative effects is through down-regulation of the expression of PTHrP, which is known to increase the proliferation of cells derived from prostate and other tissues. We also show that inhibition of pro-invasive integrin α6β4 expression by 1,25(OH)2D3 occurs downstream of PTHrP inhibition. Since PTHrP plays a major role in prostate cancer growth and metastasis, and most prostate cancers show slow growth initially, these studies underlie the chemopreventive potential of vitamin D to decrease PTHrP expression and its ensuing proliferative effects. Moreover, noncalcemic vitamin D analogues may also be useful in the prevention and treatment of prostate cancer.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Milan Uskokovic, Hoffman La-Roche, for supplying 1,25-dihydroxy-vitamin D3. This work was supported by NIH grant CA83940.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Penson DF, Chan JM the Urological Diseases in America Project. Prostate Cancer J. Urology. 2007;177:2020–2029. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2007.01.121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bubendorf L, Schopfer A, Wagner U, Sauter G, Moch H, Willi N, Gasser TS, Mihatsch MJ. Metastatic patterns of prostate cancer: an autopsy study of 1,589 patients. Human Pathology. 2000;31:578–83. doi: 10.1053/hp.2000.6698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Steiner MS. Review of peptide growth factors in benign prostatic hyperplasia and urological malignancy. J Urology. 1995;153:1085–1096. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Strewler GI. Mechanisms of disease: the physiology of parathyroid hormone-related protein. New Engl J Med. 2000;342:177–185. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200001203420306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Iwamura M, Wu R, Abrahamsson PA, di Sant’Agnese PA, Cockett AT, Deftos LJ. Parathyroid hormone-related protein is expressed by prostatic neuroendocrine cells. Urology. 1994;43:667–674. doi: 10.1016/0090-4295(94)90182-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kramer S, Reynolds FJ, Jr, Castillo M, Valenzuela DM, Thorikay M, Sorvillo JM. Immunological identification and distribution of parathyroid hormone-like protein polypeptides in normal and malignant tissues. Endocrinology. 1991;128:1927–1937. doi: 10.1210/endo-128-4-1927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cramer SD, Peehl DM, Edgar MG, Wong ST, Deftos LJ, Feldman D. Parathyroid hormone-related protein (PTHrP) is an epidermal growth factor-regulated product of human prostate epithelial cells. Prostate. 1996;29:20–29. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0045(199607)29:1<20::AID-PROS3>3.0.CO;2-M. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wu G, Iwamura M, di Sant’Agnese PA, Deftos LJ, Cockett ATK, Gershagen S. characterization of the cell-specific expression of parathyroid hormone-related protein in normal and neoplastic prostate tissue. Urology. 1995;51:110–120. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(98)00077-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Iwamura M, Gershagen S, Lapets O, Moynes R, Abrahamsson PA, Cockett AT, Deftos LJ, di Sant’Agnese PA. Immunohostochemical localization of parathyroid hormone-related protein in prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia. Human Pathology. 1995;26:797–801. doi: 10.1016/0046-8177(95)90230-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Asadi F, Farraj M, Sharifi R, Malakouti S, Antar S, Kukreja S. Enhanced expression of parathyroid hormone-related protein in prostate cancer as compared with benign prostatic hyperplasia. Human Pathology. 1996;27:1319–1323. doi: 10.1016/s0046-8177(96)90344-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rabbani SA, Gladu J, Harakidas P, Jamison B, Goltzman D. Over-production of parathyroid hormone-related peptide results in increased osteolytic skeletal metastasis by prostate cancer cells in vivo. Int J Cancer. 1999;80:257–64. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0215(19990118)80:2<257::aid-ijc15>3.0.co;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Deftos LJ. Prostate carcinoma: production of bioactive factors. Cancer. 2000;88:3002–8. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(20000615)88:12+<3002::aid-cncr16>3.3.co;2-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Feldman D, Skowronski RJ, Peehl DM. Vitamin D and prostate cancer. Adv Exp Med Biol. 1995;375:53–63. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4899-0949-7_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Blutt SE, Allegretto EA, Pike JW, Weigel NL. 1,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D3 and 9-cis-retinoic acid act synergistically to inhibit the growth of LNCaP prostate cells and cause accumulation of cells in G1. Endocrinology. 1997;138:1491–7. doi: 10.1210/endo.138.4.5063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhuang SH, Burnstein KL. Antiproliferative effect of 1α,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 in the human prostate cancer cell line LNCaP involves reduction of cyclin-dependent kinase 2 activity and persistent G1 accumulation. Endocrinology. 1998;139:1197–1207. doi: 10.1210/endo.139.3.5770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tovar VA, Falzon M. Regulation of PTH-related protein gene expression by vitamin D in PC-3 prostate cancer cells. Mol Cell Endo. 2002;190:115–24. doi: 10.1016/s0303-7207(02)00003-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Iwamura M, Abrahamsson PA, Foss KA, Wu G, Cockett AT, Deftos LJ. Parathyroid hormone-related protein: a potential autocrine growth regulator in human prostate cancer cell lines. Urology. 1994;43:675–9. doi: 10.1016/0090-4295(94)90183-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tovar VA, Falzon M. Parathyroid hormone-related protein enhances PC-3 prostate cancer cell growth via both autocrine/paracrine and intracrine pathways. Reg Peptides. 2002;105:109–120. doi: 10.1016/s0167-0115(02)00007-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Thalmann GN, Anezinis PE, Chang SM, Zhau HE, Kim EE, Hopwood VL, Pathak S, von Eschenbach AC, Chung LW. Androgen-independent cancer progression and bone metastasis in the LNCaP model of human prostate cancer. Cancer Res. 1994;54:2577–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hall CL, Bafico A, Dia J, Aaronson SA, Keller ET. Prostate cancer cells promote osteoblastic bone metastases through Wnts. Cancer Research. 2005;65:7554–60. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-1317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shen X, Falzon M. PTH-related protein modulates PC-3 prostate cancer cell adhesion and integrin subunit profile. Mol Cell Endo. 2003;199:165–77. doi: 10.1016/s0303-7207(02)00287-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shen X, Falzon M. PTH-related protein enhances LoVo colon cancer cell proliferation, adhesion, and integrin expression. Reg Peptides. 2005;125:17–27. doi: 10.1016/j.regpep.2004.07.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shen X, Falzon M. PTH-related protein upregulates integrin α6β4 expression and activates Akt in breast cancer cells. Exp Cell Res. 2006;312:3822–34. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2006.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rabinovitz I, Mercurio AM. The integrin alpha6beta4 functions in carcinoma cell migration on laminin-1 by mediating the formation and stabilization of actin-containing motility structures. J Cell Biol. 1997;139:1873–84. doi: 10.1083/jcb.139.7.1873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chung J, Bachelder RE, Lipscomb EA, Shaw LM, Mercurio AM. Integrin alpha6beta4 regulation of eIF-4E activity and VEGF translation: a survival mechanism for carcinoma cells. J Cell Biol. 2002;158:165–74. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200112015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sung V, Feldman D. 1,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D3 decreases human prostate cancer cell adhesion and migration. Mol Cell Endo. 2000;164:133–43. doi: 10.1016/s0303-7207(00)00226-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Eskes R, Desagher S, Antonsson B, Martinou J-C. Bid induces the oligomerization and insertion of Bax into the outer mitochondrial membrane. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:929–35. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.3.929-935.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Potts AJ, Croall DE, Hemler ME. Proteolytic cleavage of the integrin β4 subunit. Exp Cell Res. 1994;212:9. doi: 10.1006/excr.1994.1111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Strunck E, Vollmer G. Variants of integrin β4 subunit in human endometrial adenocarcinoma cells: mediators of ECM-induced differentiation. Biochem Cell Biol. 1996;74:867–73. doi: 10.1139/o96-092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nishishita T, Okazaki T, Ishikawa T, Igarashi T, Hata K, Ogata E, Fujita T. A negative vitamin D response DNA element in the human parathyroid hormone-related peptide gene binds to vitamin D receptor along with Ku antigen to mediate negative gene regulation by vitamin D. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:10901–7. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.18.10901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tovar VA, Falzon M. Prostate cancer cell type-specific regulation of the human PTHrP gene via a negative VDRE. Mol Cell Endo. 2003;204:51–64. doi: 10.1016/s0303-7207(03)00148-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tovar VA, Weigel NL, Falzon M. Prostate cancer cell type-specific involvement of the VDR and RXR in regulation of the human PTHrP gene via a negative VDRE. Steroids. 2006;71:102–15. doi: 10.1016/j.steroids.2005.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sutton AL, MacDonald PN. Vitamin D: more than a ‘bone-a-fide’ hormone. Mol Endocrinol. 2003;17:777–791. doi: 10.1210/me.2002-0363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Krishnan AV, Peehl DM, Feldman D. Inhibition of prostate cancer growth by vitamin D: regulation of target gene expression. J Cell Biochem. 2003;88:363–71. doi: 10.1002/jcb.10334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stewart LV, Weigel NL. Vitamin D and prostate cancer. Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 2004;229:277–84. doi: 10.1177/153537020422900401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Moreno J, Krishnan AV, Peehl DM, Feldman D. Mechanisms of vitamin D-mediated growth inhibition in prostate cancer cells: inhibition of the prostaglandin pathway. Anticancer Research. 2006;26:2525–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhang Y, Zhang J, Studzinski GP. Vitamin D inhibits G1 to S progression in LNCaP prostate cancer cells through p27Kip1 stabilization and Cdk2 mislocalization to the cytoplasm. Cell Cycle. 2006;5:447–51. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M306340200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Falzon M, Du P. Enhanced growth of MCF-7 breast cancer cells overexpressing parathyroid hormone-related peptide. Endocrinology. 2000;141:1882–92. doi: 10.1210/endo.141.5.7470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ruoslahti E, Noble NA, Kagami S, Border WA. Integrins Kidney Int. 1994;45(Suppl 44):S17–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lipscomb EA, Mercurio AM. Mobilization and activation of a signaling component α6β4 integrin underlies its contribution to carcinoma progression. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2005;24:413–23. doi: 10.1007/s10555-005-5133-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mercurio AM, Rabinovitz I. Towards a mechanistic understanding of tumor-invasion – lessons from the alpha6beta4 integrin. Seminars Cancer Biol. 2001;11:129–41. doi: 10.1006/scbi.2000.0364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bonaccorsi L, Carloni V, Muratori M, Salvadori A, Giannini A, Carini M, Serio M, Forti G, Balde E. Androgen receptor expression in prostate carcinoma cells suppresses α6β4 integrin-mediated invasive phenotype. Endocrinology. 2000;141:3172–82. doi: 10.1210/endo.141.9.7640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Maniero F, Murgia C, Wary KK, Curatola AM, Pepe A, Blumemberg M, Westwick JK, Der CJ, Giancotti FG. The coupling of α6β4 integrin to Ras-MAP kinase pathways mediated by Shc controls keratinocyte proliferation. EMBO J. 1997;16:2365–2375. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.9.2365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Maniero F, Pepe A, Wary KK, Spinardi L, Mohammadi M, Schlessinger J, Giancotti FG. Signal transduction of the α6β4 integrin: distinct β4 subunit sites mediate recruitment of the Shc/Grb2 and association with the cytoskeleton of hemidesmosomes. EMBO J. 1995;14 :4470–4481. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb00126.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Guo W, Pylayeva Y, Pepe A, Yoshioka T, Muller WJ, Inghirami G, Giancotti FG. β4 integrin amplifies ErbB2 signaling to promote mammary tumorigenesis. Cell. 2006;126:489–502. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.05.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Murillo H, Schmidt LJ, Tindall DJ. Tyrphostin AG825 triggers p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase-dependent apoptosis in androgen-independent prostate cancer cells C4 and C4-2. Cancer Res. 2001;61:7408–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Stewart LV, Lyles B, Lin M-F, Weigel NL. Vitamin D receptor agonists induce prostatic acid phosphatase to reduce cell growth and HER-2 signaling in LNCaP-derived human prostate cancer cells. Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2005;97:37–46. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2005.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Roudier MP, Corey E, True LD, Hiagno CS, Ott SM, Vessell RL. Histological, immunophenotypic and histomorphometric characterization of prostate cancer bone metastases. Cancer Treat Res. 2004;18:311–39. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4419-9129-4_13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hall CL, Kang S, MacDougals OA, Keller ET. Role of Wnts in prostate cancer bone metastases. J Cell Biochem. 2006;97:661–72. doi: 10.1002/jcb.20735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Guise TA. Molecular mechanisms of osteolytic bone metastases. Cancer. 2000;88 (suppl):2892–8. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(20000615)88:12+<2892::aid-cncr2>3.0.co;2-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Shaw LM, Rabinovitz I, Wang HH-F, Toker A, Mercurio AM. Activation of phosphoinositide 3-OH kinase by the α6β4 integrin promotes carcinoma invasion. Cell. 1997;91:949–960. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80486-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]