Abstract

Mitochondrial dysfunction is a key pathologic event in cardiac ischemia-reperfusion (IR) injury, and protection of mitochondrial function is a potential mechanism underlying ischemic preconditioning (IPC). Acknowledging the role of nitric oxide (NO•) in IPC, it was hypothesized that mitochondrial protein S-nitrosation may be a cardioprotective mechanism. The reagent S-nitroso-2-mercaptopropionyl-glycine (SNO-MPG) was therefore developed to enhance mitochondrial S-nitrosation and elicit cardioprotection. Within cardiomyocytes, mitochondrial proteins were effectively S-nitrosated by SNO-MPG. Consistent with the recent discovery of mitochondrial complex I as an S-nitrosation target, SNO-MPG inhibited complex I activity and cardiomyocyte respiration. The latter effect was insensitive to the NO• scavenger c-PTIO, indicating no role for NO•-mediated complex IV inhibition. A cardioprotective role for reversible complex I inhibition has been proposed, and consistent with this SNO-MPG protected cardiomyocytes from simulated IR injury. Further supporting a cardioprotective role for endogenous mitochondrial S-nitrosothiols, patterns of protein S-nitrosation were similar in mitochondria isolated from Langendorff perfused hearts subjected to IPC, and mitochondria or cells treated with SNO-MPG. The functional recovery of perfused hearts from IR injury was also improved under conditions which stabilized endogenous S-nitrosothiols (i.e. dark), or by pre-ischemic administration of SNO-MPG. Mitochondria isolated from SNO-MPG-treated hearts at the end of ischemia exhibited improved Ca2+ handling and lower ROS generation. Overall these data suggest that mitochondrial S-nitrosation and complex I inhibition constitute a protective signaling pathway that is amenable to pharmacologic augmentation.

Keywords: Experimental Therapeutics, NO donor, S-nitrosothiol, Complex I, Preconditioning, MPG

Introduction

Ischemia-reperfusion (IR) injury is detrimental to cardiac energy metabolism and contractility. Much of the cellular damage observed in IR injury is the result of events at the mitochondrial level, such as Ca2+ overload and the over production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) [1]. These events lead to opening of the mitochondrial permeability transition (PT) pore, cytochrome c release, and subsequent apoptosis or necrosis [2–4]. The extent of cellular damage in IR is dependent on the length of ischemia, and interestingly brief periods of ischemia are known to trigger signaling pathways that protect against longer ischemic insults; a phenomenon known as ischemic preconditioning (IPC) [5]. Despite numerous studies the precise mechanisms of IPC are still under debate, but the preservation of mitochondrial function is believed to be an important end-point in IPC signaling. Several protective IPC mechanisms are intrinsic to mitochondria, including opening of K+ATP channels [6–8], activation of uncoupling proteins (UCPs) [9–11], modulation of ROS generation [12], or regulation of signaling pathways that impact on the PT pore [13, 14]. The complex interplay between these mitochondrial IPC end-points and the upstream cytosolic signals that control them is an area of acute interest.

Nitric oxide (NO•) is a signaling molecule soundly implicated in the mechanism of IPC [15–17]. Potential sources of cardioprotective NO• include endogenous production by NO• synthases (NOSs) [15, 18], or exogenous administration of various NO• precursors including S-nitrosoglutathione (GSNO) [19], nitroglycerine [20], or nitrite [21]. Notably, NO• can control a number of mitochondrial functions such as Ca2+ accumulation and PT pore opening [1, 22]. However as with many other IPC signals, the molecular mechanisms by which NO• acts at the mitochondrial level in IPC are poorly understood.

S-nitros(yl)ation is the reversible NO•-mediated modification of thiols resulting in generation of S-nitrosothiols (SNOs), and is proposed to be a mechanism of NO•-mediated cellular regulation [23–26]. Recently, we suggested that mitochondrial S-nitrosation is a potential mechanism of NO• signaling in IPC [27], with one particular example being the S-nitrosation and reversible inhibition of mitochondrial respiratory complex I [27, 28]. Notably, it has been demonstrated that reversible complex I inhibition by amobarbital is cardioprotective [29, 30], and this led us to hypothesize that mitochondrial S-nitrosation and subsequent reversible inhibition of the respiratory chain could be a therapeutic avenue for cardioprotection.

Low molecular weight SNOs such as GSNO and S-nitroso-cysteine (SNOC) have previously been used as S-nitrosating agents [23, 25], and are known to elicit cardioprotection [31], but are pleiotropic in their actions. Therefore, it was hypothesized that administration of a low molecular weight SNO that accumulates preferentially in mitochondria would deliver cardioprotection at low doses. The parent thiol used in this study was 2-mercaptopropionyl glycine (MPG), which has previously been shown by radiolabeling to accumulate in mitochondria [32], and is known to be both mitochondria- and cardio-protective in IR injury [33, 34]. MPG was S-nitrosated to yield the S-nitrosothiol SNO-MPG (Figure 1), which is herein shown to S-nitrosate mitochondria, inhibit complex I, and protect cardiomyocytes and perfused hearts from IR injury.

Figure 1. Chemical structure of SNO-MPG.

Materials & Methods

Animals, chemicals and reagents

Male Sprague-Dawley rats (200–250g) were from Harlan (Indianapolis, IN) and were maintained under the recommendations of the NIH Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. Crude type II collagenase was from Worthington Biochemical (Lakewood, NJ) and was stripped of endotoxin by chromatography on AffinityPak™ Detoxi-Gel™ columns (Pierce, Rockford, IL). All other chemicals were analytical grade from Sigma (St. Louis, MO) unless otherwise stated.

SNO preparation and quantification

Synthesis of GSNO was performed as previously described [27]. Synthesis of SNO-MPG was performed by combining MPG (150 mM) with NaNO2 (150 mM) and HCl (0.5 M). Prior to each experiment, SNO concentration was determined spectrophotometrically at 334nm (ε=855M−1), and SNO-MPG solutions below 95% purity were discarded.

Heart perfusions

Isolated rat hearts were retrograde perfused in Langendorff mode under constant flow, essentially as described [10]. Hearts were subjected to one of the following protocols: (i) IR consisting of 25 min. ischemia plus 30 min. reperfusion; (ii) IR in the dark (laboratory lights switched off); (iii) IR in the dark with SNO-MPG (10μM) infused into the perfusion cannula just above the aorta for 20 min. prior to ischemia; (iv) IPC plus ischemia, consisting of 3 cycles of 5 min. occlusion followed by 5 min. of reperfusion each, followed by the 25 min. global ischemia, without reperfusion; (v) Ischemia alone without reperfusion, in the dark; (vi) SNO-MPG plus ischemia alone without reperfusion, in the dark.

Cardiomyocyte isolation and incubations

Ca2+ tolerant adult rat ventricular cardiomyocytes were isolated as described previously [35], except for the use of endotoxin-stripped collagenase (see above). The protocol yielded ∼4×106 cells per heart, with ∼85% of cells rod-shaped and excluding Trypan blue. Cell count was adjusted to 106/ml and cells were kept in Krebs Henseleit (KH) buffer with 2% (w/v) bovine serum albumin (BSA, Fraction V, Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh PA), in a shaking water bath (80 cycles/min.) prior to incubations. Cells were divided into the following treatment groups: (i) normoxia, 95%O2/5%CO2 at pH 7.4; (ii) hypoxia-reoxygenation (HR) comprising 1 hr. of hypoxia (95%N2/5%CO2, glucose-free KH buffer, pH 6.5), followed by 30 min. of reoxygenation (95%O2/5%CO2, glucose-replete KH buffer, pH 7.4); (iii) HR plus IPC, comprising 1 × 20 min. hypoxia plus 20 min. reoxygenation, followed by HR as above; (iv) HR plus GSNO, comprising treatment with 10, 20 or 100 μM GSNO for 20 min. prior to HR; (v) HR plus SNO-MPG, comprising treatment with 10 or 20 μM SNO-MPG for 20 min. prior to HR; (vi) HR plus MPG, comprising treatment with 20 μM MPG for 20 min. prior to HR; (vii) HR plus SNO-MPG plus ODQ, comprising treatment with 20 μM SNO-MPG as in (v) above, plus addition of 10μM of the soluble guanylate cyclase (sGC) inhibitor 1H-[1,2,4]Oxadiazole[4,3-a]quinoxalin-1-one (ODQ), 5 min. prior to SNO-MPG addition; (viii) HR plus SNO-MPG plus light, in which cells treated with 20 μM SNO-MPG as in (v) above, were exposed to 2 min. illumination by a cold fiber-optic white light source, immediately prior to HR. All incubations utilized 5 × 105 cells in a 5 ml buffer volume, and were performed in 50 ml round-bottomed tubes in a 37°C shaking water bath (80 cycles/min). To switch conditions, cells were centrifuged at 31 × g for 2 min. and the pellet resuspended in the same volume of the appropriate buffer. However, for IPC itself the media was not changed, merely the superfusing O2 level. All incubations were in the dark (apart from light exposure in group (viii)). Following incubations, cells were analyzed for viability and Δψm. In addition, aliquots were taken at various time points for assay of complex I and IV activities.

In a separate series of incubations aimed at tracing the intracellular fate of SNO-MPG, cardiomyocytes (5 × 105 cells / 5 ml) treated with SNO-MPG (20 μM, 20 min.) were sub-fractionated (see below) and the homogenate, mitochondria and cytosolic fractions were analyzed by ozone chemiluminescence for SNO content. Mitochondria were traced through this fractionation protocol by monitoring the matrix marker enzyme citrate synthase [36]. Furthermore, S-nitrosation of complex I in these mitochondria was monitored by separating the respiratory complexes using blue-native electrophoresis, followed by ozone chemiluminescence analysis of the complex I bands, as previously described [27].

SNO stability studies

The breakdown of S-nitrosothiols and subsequent NO• release was monitored using a polarographic NO• electrode (ISO-NO, World Precision Instruments, Sarasota FL). The electrode was fitted into a cardiomyocyte incubation tube, and to a normoxic suspension of cardiomyocytes (5 × 105 cells in 5 ml) was added a bolus of either 20 μM SNO-MPG or GSNO. The NO• level was monitored for 20 min., followed by addition of authentic NO• (from a 2mM stock solution of NO• gas in argon-purged water) to calibrate the electrode. Fifty μM of the NO• scavenger 2-(4-carboxyphenyl)-4,5-dihydro-4,4,5,5-tetramethyl-1H-imidazolyl-1-oxy-3-oxide (c-PTIO, Axxora, San Diego CA) was then added to bring the electrode signal to zero and compensate for drift.

Measurement of membrane potential (ΔΨm) and respiration in cardiomyocytes

For ΔΨm determination, cells (105/ml.) were loaded with 20nM TMRE (tetramethylrhodamine ethyl ester) in non-quench mode, for 20 min. at 37°C, in KH buffer plus 2% BSA. TMRE fluorescence was measured (555nmex, 577nmem) in a Cary Eclipse fluorimeter (Varian, Australia). The mitochondrial uncoupler carbonylcyanide-p-trifluoromethoxyphenylhydrazone (FCCP, 5 μM) was added to dissipate ΔΨm, and the Δ fluoresence recorded.

To measure respiration rate, cells (105/ml.) were incubated at 37°C in KH buffer plus 2% BSA, for 20 min. with either GSNO (20 μM), SNO-MPG (20 μM), or w/o treatment (control). Respiration was then measured using a Clark-type O2 electrode (YSI, Yellow Springs OH) in a 1.5 ml chamber. Following establishment of a stable O2 consumption rate, the NO• scavenger c-PTIO was added to the chamber (50 μM), to reverse any respiratory inhibition caused by NO• binding at cytochrome c oxidase (complex IV). At the end of each run, KCN (1 mM) was added, and any residual non-mitochondrial O2 consumption accounted for.

Mitochondrial isolation from hearts or cells

Mitochondria were isolated from hearts as previously described [10]. Protein was determined by the Lowry method [37] against a standard curve constructed using BSA. To isolate mitochondria from cardiomyocytes the cell pellet (3×105 cells) was resuspended in 100μl of buffer containing sucrose (440 mM), MOPS (20 mM), EGTA (1 mM), DTPA (100 μM), iodoacetic acid (100 μM), pH 7.2 at 4°C. Cells were homogenized in a micro glass Dounce homogenizer (60 passes), and diluted 3-fold with buffer, then centrifuged at 500 × g for 3 min. to pellet debris. The supernatant was centrifuged at 14000 × g for 5 min. to pellet mitochondria. The supernatant from this spin was then centrifuged at 100,000 × g for 15 min. to obtain the nominal cytosolic fraction. Integrity pf mitochondria was checked by measurement of their respiratory properties with a Clark O2 electrode [36], with mitochondria from cells exhibiting respiratory control ratios of 8.8 ± 0.5 respiring on glutamate plus malate, and 5.3 ± 0.3 respiring on succinate.

Isolated mitochondrial incubations

Heart mitochondria were suspended (1 mg protein/ml) in mitochondrial respiration buffer comprising KCl (120 mM), sucrose (25 mM), MgCl2 (5 mM), KH2PO4 (5 mM), EGTA (1 mM), HEPES (10 mM) pH 7.35 at 37°C, in the presence of succinate (10 mM), glutamate (10 mM) and malate (5 mM). Incubations also included GSNO or SNO-MPG (0, 10, 20 or 100 μM). Samples were incubated at 37°C for 30 min. then centrifuged at 14,000 × g for 5 min. at 4°C. Supernatant was removed and retained, fresh buffer containing DTPA (100 μM) was added to wash the pellet, and samples were centrifuged again. The supernatant was removed and discarded, and the pellet plus first supernatant were used for chemiluminescence analysis of NO2-, SNO, and Fe-NO content (results in Table 1). Pellets were also assayed for SNO content by the biotin switch analysis (see below, Figure 4B). Complex I activity of pellets was measured spectrophotometrically (340 nm) as the rotenone-sensitive rate of NADH oxidation in the presence of coenzyme-Q1 (Eisai Pharmaceutical, Japan) as previously described [27, 36].

Table 1. Metabolism of S-nitrosothiols in mitochondria.

Mitochondria (0.5 mg) were incubated in 0.5 ml respiration buffer in the presence of respiratory substrates and GSNO or SNO-MPG (10, 20, 100 μM) for 30 min. Samples were centrifuged, pellets washed, and the pellets and supernatants analyzed by chemiluminescence (see methods) for SNO, NO2- and Iron-nitrosyl (Fe-NO). Data are means ± SEM of at least 3 independent experiments.

| SNO added (nmols) | Supernatant (nmols)

|

Pellet (nmols)

|

Total (nmols) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SNO | NO2- | Fe-NO | SNO | NO2- | Fe-NO | |||

| 0 | - | 0.3±0.3 | - | - | - | - | 0.29 | |

| GSNO | 5 | 4.0±1.2 | 0.9±0.1 | - | 0.5±0.1 | 0.3±0.1 | - | 5.71 |

| 10 | 8.6±2.3 | 1.0±0.3 | - | 1.0±0.1 | 0.2±0.1 | - | 10.87 | |

| 50 | 45.6±10.0 | 5.6±2.0 | - | 2.0±0.1 | 0.4±0.1 | - | 53.51 | |

| SNO-MPG | 5 | 3.4±0.8 | 2.0±0.5* | - | 1.2±0.1* | 0.5±0.1 | - | 7.08 |

| 10 | 6.3±1.2 | 4.4±0.9* | - | 1.6±0.1* | 0.1±0.1 | - | 11.99 | |

| 50 | 27.2±4.4* | 18.9±5.2* | - | 2.8±0.1* | 0.6±0.1 | - | 49.76 | |

p<0.05 between GNSO and SNO-MPG groups.

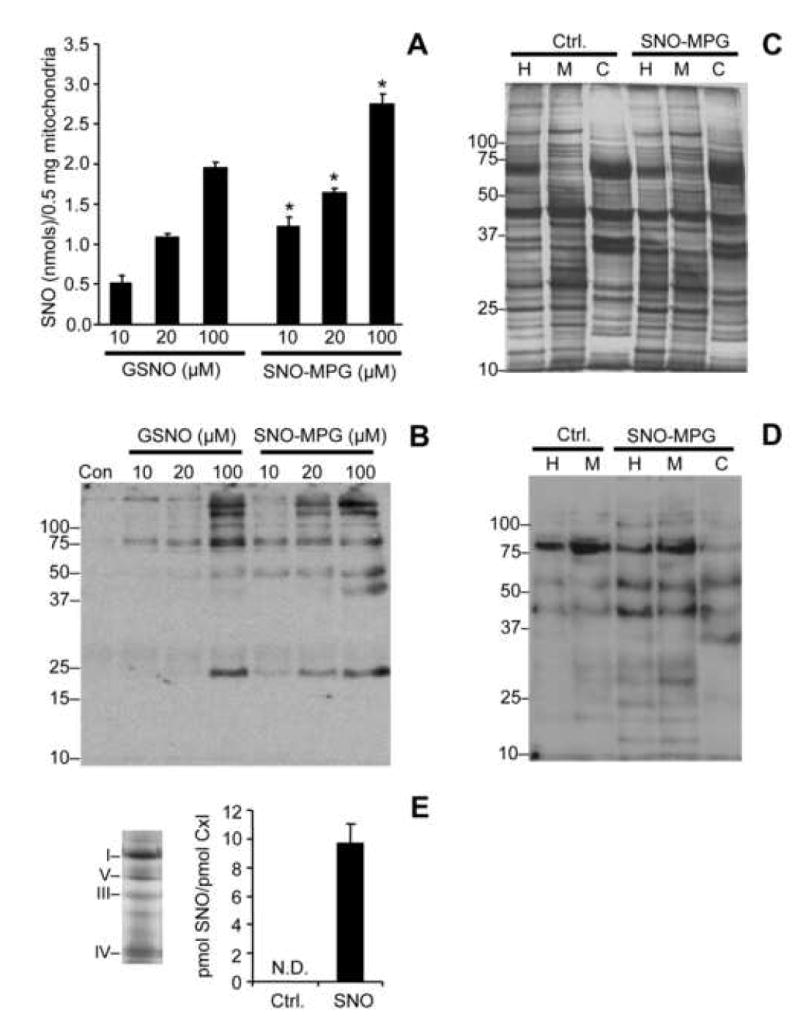

Figure 4. S-nitrosation of isolated mitochondria and mitochondria inside cells by SNO-MPG.

(A): Mitochondria were treated with GSNO or SNO-MPG at the concentrations given on the x-axis, as detailed in the methods. SNO content of mitochondrial pellets was determined by chemiluminescence analysis as described in the methods. Data are means ± SEM of at least 4 independent experiments. *p<0.01 between GSNO and SNO-MPG at the same concentration. No SNO was detected in un-treated controls (Cf. Table 1). See also Table 1 for other SNO metabolites. (B): Mitochondrial S-nitrosation was analyzed using the biotin-switch method (see methods). Bands in the control lane of the western blot (Con) are indicative of endogenous mitochondrial biotin-containing proteins (e.g. decarboxylases). Other bands represent peptides that were S-nitrosated by GSNO or SNO-MPG treatment. Blot is representative of at least 3 independent experiments, and numbers to the left are molecular weight markers (kDa). (C/D): Cardiomyocytes were incubated as detailed in the methods, in the absence (Ctrl.) or presence (SNO) of 20 μM SNO-MPG for 20 min. Mitochondria were then isolated from the cells (see methods) and the total cell homogenate (H), isolated mitochondria (M), and cytosol (C) were analyzed by the biotin-switch method. Panel C shows a typical Coomassie-stained gel following separation of peptides by SDS-PAGE. Panel D shows a biotin-switch western blot. Both blot and gel are representative of at least 3 independent experiments, and numbers to the left are molecular weight markers (kDa). (E): S-nitrosation of complex I inside cardiomyocytes. Mitochondria were isolated from cells treated with SNO-MPG as above, and respiratory complexes separated by blue-native gel [27]. Left panel shows a representative gel, with positions of complexes indicated by Roman numerals. Right panel shows the SNO content (ozone chemiluminescence) of complex I excised from the gels. Data are means ± standard deviation of 2 independent experiments. N.D. = not detectable (i.e. below limit of detection of apparatus).

Chemiluminescent SNO detection

Mitochondrial pellets (0.5mg protein) were extracted in 100μl of extraction buffer comprising phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), DTPA (100 μM), laurylmaltoside (1% w/v), pH 7.4. For cell fractions (homogenate, mitochondria, cytosol) samples (30μl, 5μl, and 30μl respectively) were all diluted up to 100μl in the same extraction buffer. All samples were then divided into 3 × 33 μl aliquots which were then treated with either sulfanilamide (5% w/v), sulfanilamide (5% w/v) plus HgCl2 (5 mM), or extraction buffer alone. Samples (39 μl) were reacted on ice for 2 min., then 15 μl injections made into an argon-fed purge vessel containing triiodide reagent, connected to a Sievers NOA-280 chemiluminescent ozone NO• analyzer (Ionics Instruments, Boulder, CO). Each sample was injected twice, and NO• was quantified using a standard curve created with known concentrations of NaNO2 [27, 38]. All incubations and detections were performed in the dark.

Biotin switch analysis

Mitochondrial pellets (1 mg protein) or cardiomyocyte mitochondria (0.5 mg protein) were analyzed by biotin switch analysis as previously described [27]. The blocking step used methyl-methanethiosulfonate (20 mM), and the labeling step used ascorbate (1 mM) plus biotin-HPDP (50 mM) (Molecular Probes, Eugene OR). Samples were loaded onto non-reducing SDS-PAGE gels, and nitrocellulose blots were probed with streptavidin-peroxidase and enhanced chemiluminescence detection (GE Biosciences, Piscataway, NJ). Due to interference of some cellular components (e.g. lipids) with the protein assay, which was different between various cell fractions (e.g. homogenate, cytosol, mitochondria), protein loading on gels was independently controlled. A primary gel was run and stained with Coomassie blue, and densitometry performed on whole lanes (“Scion-Image” software, Scion Corporation, Frederick MD). Based on these densitometric data, equal protein was loaded on a second gel, which was then used for western blotting analysis. Protein loading was also verified by staining blot membranes with Ponceau S.

Mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake & ROS generation

Mitochondria were isolated at the end of perfused heart protocols (v) and (vi), i.e. ischemia without reperfusion, in the presence or absence of SNO-MPG. Mitochondrial content in subsequent experiments was normalized to citrate synthase activity, determined as previously described [36]. Mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake was measured spectrophotometrically using Arsenazo III as previously described [39], with glutamate plus malate as respiratory substrates. Mitochondrial ROS generation was monitored spectrofluorimetrically using Amplex red (Molecular Probes, Eugene OR), as previously described [36].

MPG uptake

Mitochondria (0.25 mg protein) were incubated in 250 μl of respiration buffer plus glutamate (10 mM), malate (5 mM), succinate (10 mM), and MPG (20 μM), at 37°C for 30 min. After centrifugation at 14,000 × g for 5 min., supernatants were saved. Mitochondrial pellets were washed and then resuspended in 250 μl of the same buffer containing Triton X-100 (0.1% v/v). Samples (150 μl) were added to cuvets containing 5,5′-Dithio-bis-2-nitrobenzoic acid (DTNB, 1 mM) in PBS to a final volume of 0.5 ml. Absorbance at 412 nm was used to calculate free thiol concentration, using ε=13600 M−1. Incubation conditions were: (i) buffer alone, (ii) MPG alone, (iii) control mitochondria without MPG, (iv) mitochondria plus MPG. The contribution of endogenous mitochondrial thiols to the DTNB reaction signal was subtracted, to determine the MPG-dependent signal.

Statistics

In cell experiments, each “N” was an independent cardiomyocyte isolation. Student's t-test or analyses of variance (ANOVA) were applied to the data. Appropriate numbers of experiments were performed (N = 4−6) to ensure adequate statistical power. Differences were considered significant if p<0.05.

Results

Mitochondrial uptake of MPG & SNO-MPG

It has been shown that MPG accumulates in mitochondria when administered to whole animals [32], but for this investigation it is important to confirm that cardiac mitochondria also take up MPG. In this regard we found that incubation of 1 mg (protein) isolated rat heart mitochondria in 1 ml buffer, with 20 nmols of MPG (i.e. 20 μM) for 20 min. at 37°C resulted in 4.8 ± 1.2 nmols of MPG accumulating inside the mitochondria (mean ± SEM, N=4). Assuming an internal volume for heart mitochondria of 0.65 μl/mg protein [40] this equates to an internal concentration of 7.4 mM MPG. Thus, the gradient of MPG accumulation into energized mitochondria (7.4mM [MPG]in / 15.2μM [MPG]out) is approximately 500-fold. In separate experiments, incubation of 1 mg mitochondria with 20 μM SNO-MPG in 1 ml for 20 min. at 37°C, followed by extensive washing of mitochondrial pellets resulted in 3.2 nmols of SNO detectable inside mitochondria, which equates to an internal concentration of approximately 5 mM SNO, or ∼300-fold accumulation (not including losses of SNO during sample preparation and processing, see Table 1 below). Having determined that both MPG and SNO-MPG are actively accumulated by mitochondria, SNO-MPG was used in subsequent studies on isolated mitochondria, cardiomyocytes and perfused hearts, to determine if it enhanced mitochondrial S-nitrosation and elicited cardioprotection during IR.

Protection of cardiomyocytes against HR injury by GSNO and SNO-MPG

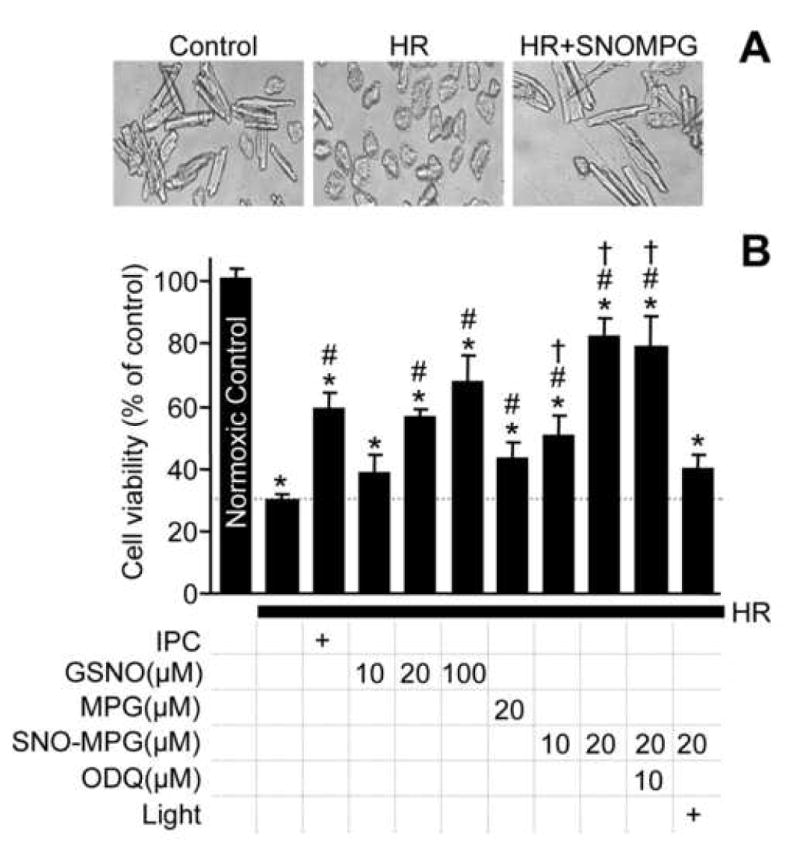

The aim of these experiments was to determine the protective efficacy of SNO-MPG in a cardiomyocyte model of IR injury, with the well-known S-nitrosating agent GSNO serving as a control. Figure 2A shows typical morphologic features of cells from the control, HR and HR plus 20 μM SNO-MPG groups. The effects of various concentrations of GSNO and SNO-MPG on cell viability after HR are quantified in Figure 2B. As expected, IPC protected cells from HR injury-induced cell death. For GSNO, slight protection was seen at 10 μM, and maximal protection occurred at 100 μM. Higher doses of GSNO (1 mM) were cytotoxic (not shown), consistent with previous studies [41]. In contrast to GSNO, 10 μM of SNO-MPG significantly preserved cell viability, and 20 μM SNO-MPG restored viability almost to control levels (Figure 2B). Notably, the protection elicited by SNO-MPG was not abrogated by inclusion of the sGC inhibitor ODQ in the incubations (Figure 2B), indicating no role for classical NO•/cGMP signaling in the mechanism of protection. This result contrasts with previous studies showing that the cardioprotective effect of GSNO was cGMP dependent [31, 42]. At 20 μM, the parent thiol of SNO-MPG (i.e. MPG) elicited a small amount of protection, which could account for less than 20% of the overall protective effect of 20μM SNO-MPG.

Figure 2. Effect of SNO-MPG on cardiomyocyte viability, in simulated IR injury.

Cardiomyocyte isolation and incubations were performed as detailed in the methods. Isolated cardiomyocytes were subjected to preconditioning (IPC) or pharmacological treatment with GSNO or SNO-MPG, prior to hypoxia-reoxygenation (HR) injury. (A): Representative photomicrographs showing typical morphological changes in cardiomyocytes subjected to HR, compared to control and SNO-MPG (20 μM) treated cells. (B): Cell viability (Trypan blue exclusion) measured at the end of reoxygenation. Experimental conditions are listed below the x-axis. ODQ = soluble guanylate cyclase inhibitor. Data are means ± SEM of at least 5 independent experiments. *p<0.05 vs. control, #p<0.05 vs. HR, †p<0.05 between matching concentrations of SNO-MPG and GSNO.

A notable property of S-nitrosothiols is their sensitivity to degradation by light. In suggestion of a role for protein S-nitrosation in the protective effects of SNO-MPG, it was observed that exposure of SNO-MPG treated cells to 2 min. of illumination abrogated the protective effects of SNO-MPG, effectively bringing the level of protection down to that seen with MPG alone (Figure 2B). This occurred at a time point (>20 min.) at which all low molecular weight SNO had disappeared (see Figure 5C).

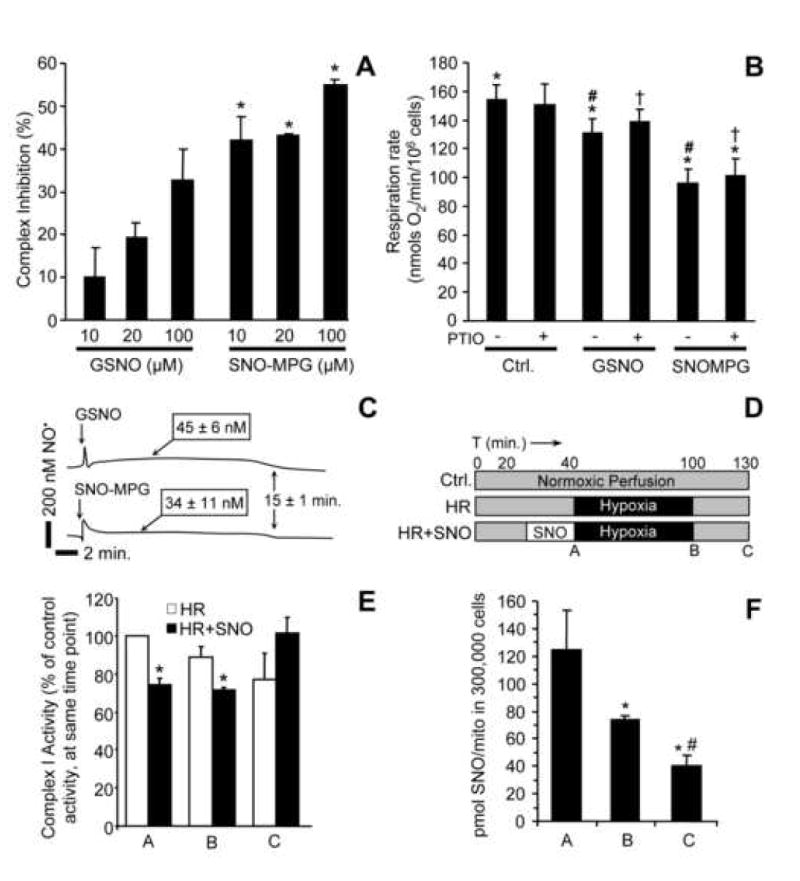

Figure 5. Inhibition of complex I and respiration by S-nitrosothiols.

(A): Isolated mitochondria (0.5 mg) were incubated with GSNO or SNO-MPG (10, 20 or 100 μM) for 20 min. Complex I activity was then measured as detailed in the methods. Data are means ± SEM of at least 3 independent experiments *p<0.02 between GSNO and SNO-MPG groups. (B): Cardiomyocytes were treated with SNO-MPG or GSNO, and their respiration rates determined as detailed in the methods. In certain incubations, the NO• scavenger PTIO was added to reverse NO• mediated inhibition of respiratory complex IV (cytochrome c oxidase). Significant differences (p<0.05) exist between groups with the same symbols (*, #, †). (C): NO• release by SNOs was monitored using a polarographic NO• electrode in a typical cardiomyocyte incubation (5 × 105 cells / 5 ml). SNO-MPG or GSNO were added at 20 μM, and [NO•] followed for 20 min. Steady-state NO levels (means ± SEM, N>3) are indicated above the traces. (D): Protocol for cell HR experiments, indicating times (ABC) of mitochondrial isolation for complex I assays and SNO measurement. (E): Complex I activity at time points A, B, C during HR protocol. Rates from the HR and HR + SNO groups are expressed as percentages of the rate in normoxic controls. (F): SNO levels in mitochondria from the HR + SNO treatment group, as in panels D and E. Under no conditions was SNO detectable in the HR alone or normoxic samples (not shown). Data in panels E and F are means ± SEM of at least 3 independent experiments.

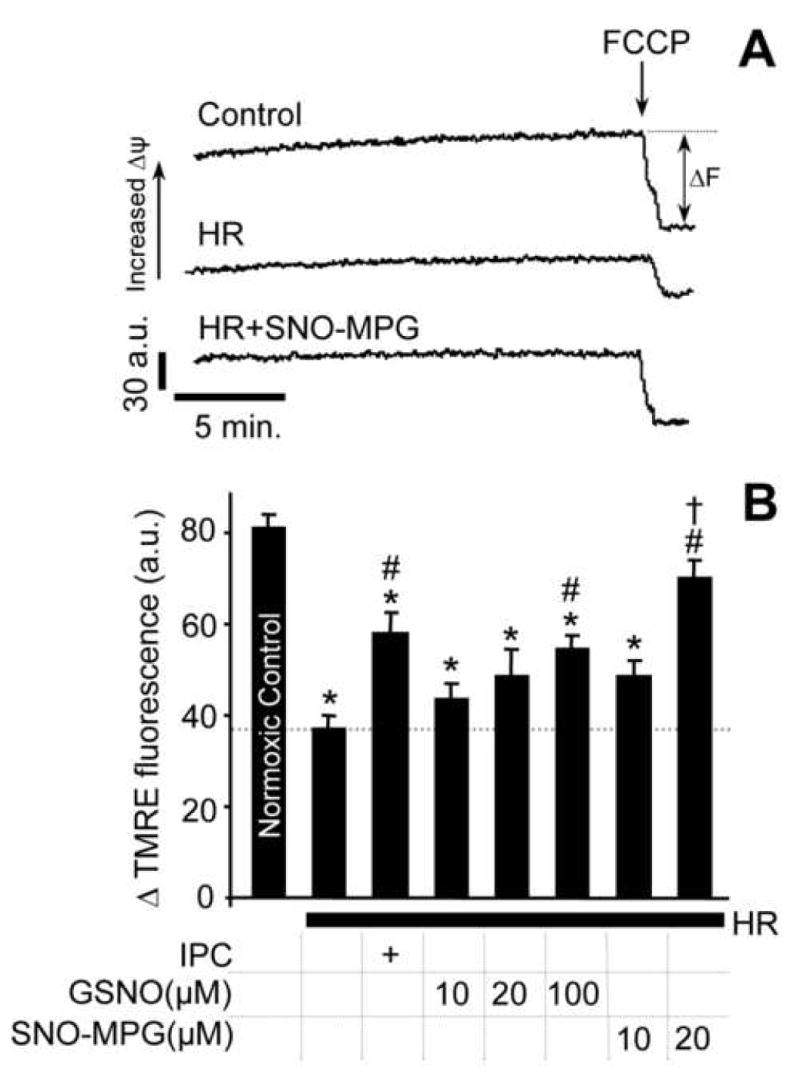

Since it is known that live cells can take up Trypan blue [43], it is possible that when using this assay mitochondria may be viable inside nominally “dead” cells, and thus Trypan blue exclusion alone may not be a sufficient indicator of the effect of SNOs on preservation of mitochondrial function. Assessing mitochondrial function in this system is important, because it correlates closely with cardiac contractility after IR injury [44]; whereas it is not immediately apparent that cardiomyocyte viability necessarily translates to changes in contractility at the whole heart level. Therefore Δψm, a commonly used mitochondrial functional parameter, was measured and the results (Figure 3) show that HR injury significantly depleted Δψm. The IPC-, GSNO- or SNO-MPG-treated samples all exhibited preservation of Δψm, and the effect of SNO-MPG was greater than that of GSNO. In separate experiments (not shown) it was found that treatment with 20 μM MPG (the parent thiol of SNO-MPG) did not confer significant protection of cell viability or Δψm in HR injury. This is in agreement with previous studies which required up to 400 μM MPG to elicit protection in cell systems [45]. Together, Figures 2 and 3 show that 10–20 μM of SNO-MPG prevents both cell death and mitochondrial dysfunction in HR injury; these effects are largely independent of the antioxidant properties of MPG.

Figure 3. Effect of SNO-MPG on cardiomyocyte mitochondrial function, in simulated IR injury.

Cardiomyocyte isolation and incubations were performed as detailed in the methods. Isolated cardiomyocytes were subjected to preconditioning (IPC) or pharmacological treatment with GSNO or SNO-MPG, prior to hypoxia-reoxygenation (HR) injury. (A): Representative TMRE fluoresence traces for determination of mitochondrial membrane potential (Δψm) in cardiomyocytes from the control, HR, and HR plus SNO-MPG (20 μM) groups. ΔF represents difference before and after FCCP (5 μM) addition. (B): Average ΔTMRE fluorescence (a.u. = arbitrary units). Experimental conditions are listed below the x-axis. In panels B and D, all data are means ± SEM of at least 5 independent experiments. *p<0.05 vs. control, #p<0.05 vs. HR, †p<0.05 between matching concentrations of SNO-MPG and GSNO.

Mitochondrial S-nitrosation by GSNO and SNO-MPG

Low molecular weight SNOs can modify protein thiols by trans-S-nitrosation [23, 25]. However, it was not known whether SNO-MPG could enhance mitochondrial protein S-nitrosation. The degree of S-nitrosation in mitochondria treated with GSNO or SNO-MPG (10, 20, 100 μM) was compared, and was found to be approximately 2 fold greater in the SNO-MPG group at all doses (Figure 4A). Biotin switch analysis [46] was also performed to examine S-nitrosation patterns following SNO treatment (Figure 4B), and it was found that at similar treatment concentrations SNO-MPG led to more protein S-nitrosation of certain bands than GSNO. Densitometric analysis of entire lanes from several such blots revealed that SNO content was approximately 40% higher in SNO-MPG treated samples, although such quantitative data is to be interpreted with caution, owing to limited dynamic range of the western blot method. Notably, inclusion of the pyruvate transport inhibitor α-hydroxycinnaminate (5 μM) in SNO-MPG incubations elicited a different pattern of S-nitrosation to that seen in Figure 4B (data not shown). While this result suggests a role for the pyruvate transporter in the regulation of SNO-MPG uptake, it does not prove that this channel is the actual mechanism for uptake of the compound.

To investigate the metabolism of S-nitrosothiols in isolated mitochondrial incubations, chemiluminescence analysis [38] was used to measure the levels of NO2-, SNO and Fe-NO in mitochondrial pellets and supernatants (Table 1). All SNO added to the system was accounted for after adding together the nmols SNO and NO2- detected in both the pellets and supernatants. One notable aspect of these results is that the level of NO2- in mitochondrial pellets was similar in GSNO and SNO-MPG treated samples. This finding suggests that the lower level of mitochondrial S-nitrosation in GSNO treated samples was not due to initial formation of protein SNO, followed by degradation to NO2- during the preparation procedure. In contrast, the NO2- content of supernatants was higher in the SNO-MPG treatment group at all concentrations. This may suggest a greater rate of breakdown and release of NO• from SNO-MPG, although experiments measuring NO• release by SNO-MPG (see below, Figure 5C) suggest this is not the case. Alternatively, since SNO-MPG led to enhanced S-nitrosation of proteins (see Figure 4 and below), the breakdown and metabolism of these protein S-nitrosothiols to yield nitrite and other products during sample preparation, may also have been enhanced.

SNO-MPG S-nitrosates mitochondria in cells

Although the data in Figures 4A and 4B indicate that addition of SNO-MPG to isolated mitochondria results in enhanced S-nitrosation, it is also important to test whether SNO-MPG can S-nitrosate mitochondria inside cells. To address this issue, isolated adult rat ventricular cardiomyocytes were treated with SNO-MPG (20 μM, 20 min.), mitochondria were isolated, and the SNO content of various cell fractions was analyzed both by biotin switch (Figure 4D), and chemiluminescence (Table 2). As shown in Figure 4D, the majority of proteins S-nitrosated in the whole cell homogenate were accounted for by the mitochondrial fraction, with several bands being enriched in the mitochondrial lane. The matching stained gel (Figure 4C) indicates differences in the protein composition of the homogenate, mitochondria and cytosol, showing enrichment in some bands and depletion in others (e.g. residual BSA from the cardiomyocyte isolation is present at 68 kDa in homogenate, but almost completely absent from mitochondria). The appearance of many protein bands in both homogenate and mitochondria is likely because mitochondria account for approximately 35% of cardiomyocyte volume.

Table 2. Tracking of SNO and citrate synthase activity through cellular sub-fractionation, in SNO-MPG treated cardiomyocytes.

Cells were treated with SNO-MPG (20μM, 20 min.), and fractionated as detailed in the methods. The content of SNO (chemiluminescence) and the activity of the mitochondrial matrix marker enzyme citrate synthase (CS) were measured in aliquots of each fraction, and the total amount present in each fraction was calculated based on the total volume of each fraction. Data are expressed as percentages of the total amount present in the initial cell homogenate, and are means ± SEM of at least 3 independent experiments.

| Fraction | % SNO | % CS |

|---|---|---|

| Homogenate | 100 | 100 |

| 1st supernatant (cytosol & organelles) | 43.1±0.9 | 36.6±1.0 |

| 1st pellet (nuclei, cell debris) | 21.9±1.8 | 39.1±5.9 |

| 2nd supernatant (cytosol, light membranes) | 32.7±8.9 | 9.5±2.1 |

| 2nd pellet (mitochondria) | 17.8±1.7 | 16.1±0.8 |

| 3rd supernatant (cytosol) | 12.4±1.6 | 5.0±0.0 |

Tracing SNO through the cellular sub-fractionation protocol (Table 2) reveals that the SNO content of various fractions tracked well with the mitochondrial content of these fractions (indicated by their citrate synthase activity). For example, the nominal “mitochondrial fraction” contained 16% of the total citrate synthase activity and 18% of the total SNO activity. A strong correlation was observed between the SNO and mitochondrial content of all cell fractions (r2 = 0.861) and therefore the case can be made that if the nominal mitochondrial fraction contained 100% of the mitochondria, it would contain 100% of the SNO. Notably, comparing the SNO blots in Figures 4B and 4D indicates that addition of SNO-MPG to either purified mitochondria (B) or whole cells (D) resulted in similar patterns of S-nitrosation, with prominent bands at molecular weights of approximately 25, 40, 55, and 77 kDa.

We previously identified respiratory complex I as an important target for S-nitrosation in cardiac mitochondria [27]. In this investigation, the same methods (blue-native gels to separate respiratory complexes, and ozone chemiluminescence) were used to identify complex I S-nitrosation in mitochondria isolated from SNO-MPG treated cells. The results in Figure 4E indicate that complex I of mitochondria isolated from SNO-MPG treated cells is indeed S-nitrosated. S-nitrosothiol was not detectable (N.D.) in complex I of mitochondria from control cells. The amount of S-nitrosothiol in complex I was similar to that previously reported [27]. Thus, overall the data in Figure 4 suggest that SNO-MPG can effectively S-nitrosate mitochondrial proteins inside cardiomyocytes, and that one of these proteins is complex I.

Inhibition of complex I and cellular respiration by SNO-MPG

Previous studies have shown that administration of SNOs to isolated mitochondria results in reversible complex I inhibition via S-nitrosation [27, 28, 47, 48]. Therefore it was hypothesized that mitochondrial S-nitrosation by SNO-MPG would inhibit complex I. Figure 5A shows that complex I inhibition in mitochondria treated with SNO-MPG (10–100 μM) was 2–4 fold greater than seen with GSNO.

Since NO• not only inhibits complex I, but can also inhibit respiration by reversible binding at cytochrome c oxidase (complex IV) [49], it was important to determine which mode of inhibition occurred in cells treated with SNO-MPG. Equilibrium binding of NO• at cytochrome c oxidase can be reversed by providing an external sink for NO• such as oxyhemoglobin, high [O2], or the NO• scavenger c-PTIO [49]. Conversely, S-nitrosation at complex I is a covalent modification that is not reversible by such NO• sinks. Figure 5B shows that treatment of cardiomyocytes with 20μM SNO-MPG inhibited whole cell respiration rate significantly more than treatment with 20μM GSNO. Addition of c-PTIO had no significant effect on respiratory inhibition by either SNO, indicating that the inhibition was not at complex IV. In addition, direct assay of complex IV activity [36] in SNO-MPG treated cells, indicated no significant inhibition (activity = 102.2 ± 8.5%, vs. control).

In further support for no inhibition at complex IV by SNO-MPG derived NO•, Figure 5C shows the liberation of NO• from SNO-MPG and GSNO in cardiomyocyte suspensions, measured using an NO• electrode. Both SNOs elicited steady-state levels of approximately 40 nM NO•, sustained over 15 min. Thus, at the time of respiration measurements in Fig. 5B (>20 min.) the free [NO•] was effectively zero. These data demonstrate that the reason underlying greater cardioprotective efficacy of SNO-MPG was not simply that it released more NO•. In addition these data have an important implication for those in Figure 2B; all low molecular weight SNO had degraded within 20 min., and yet the effect of SNO-MPG was still light sensitive at this time point. This suggests secondary protein S-nitrosation may underlie the effects of SNO-MPG.

Complex I inhibition by SNO-MPG during IR

Many of the pathologic mitochondrial events in IR injury (e.g. Ca2+ overload, ROS generation, PT pore opening) occur at the end of ischemia / beginning of reperfusion. It was thus hypothesized that in order to elicit protection, SNO-MPG must inhibit complex I during this critical time window. Figure 5D shows complex I activity in cardiomyocytes at various time points during a SNO-MPG treatment / HR protocol, and these data indicate that complex I is inhibited at the end of 1 hr. ischemia to the same extent as immediately after SNO-MPG delivery, prior to ischemia (time point A vs. B). Notably at the end of 30 min. reperfusion complex I activity was completely recovered to control levels. Thus, SNO-MPG delivered prior to ischemia can inhibit complex I during the critical late-ischemia / early-reperfusion time window. Furthermore, Figure 5F shows that mitochondrial SNO content was maximal immediately after SNO-MPG delivery, and was sustained throughout ischemia, decaying during reperfusion. Under no conditions was SNO detectable in mitochondria isolated from control cells subjected to HR injury (not shown).

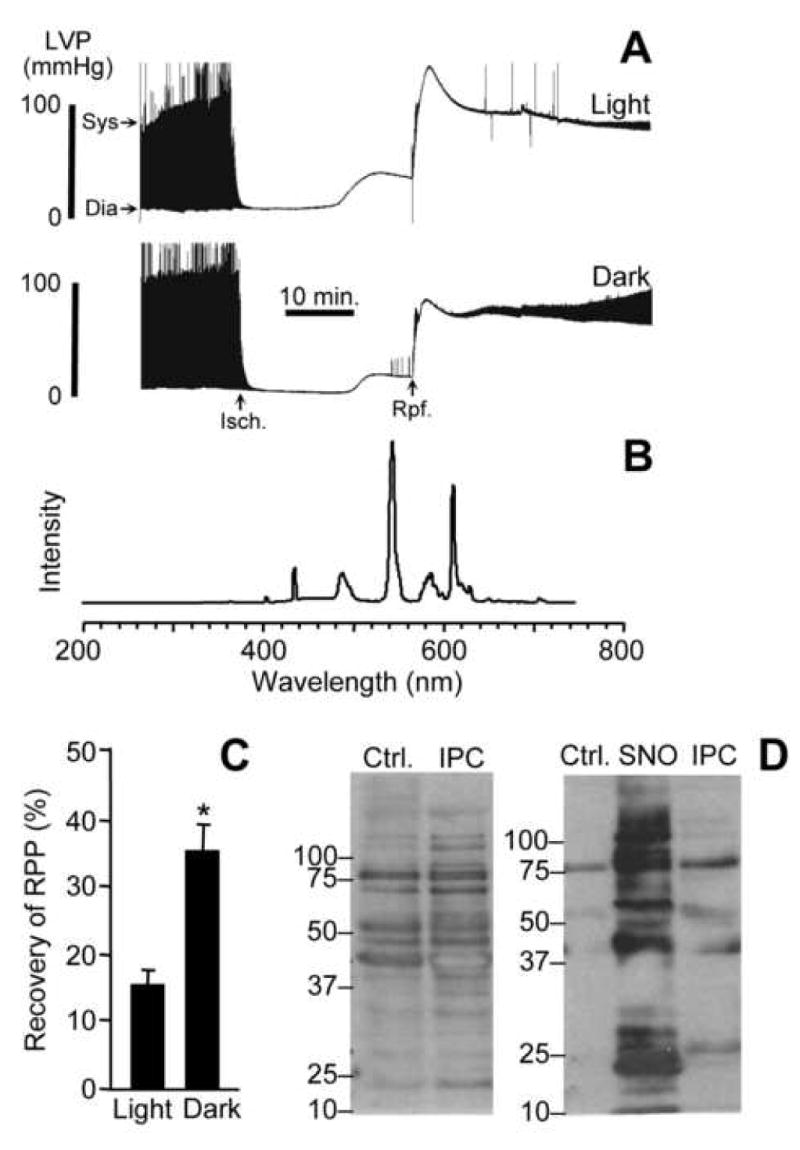

Preservation of endogenous SNO correlates with cardioprotection

Considering several reports of reversible complex I inhibition by S-nitrosation [27, 28, 47, 48], with the recent finding that complex I inhibition is cardioprotective [29, 30], and the known importance of NO• in IPC [16], we hypothesized that complex I S-nitrosation may be an endogenous cardioprotective mechanism [27]. While ischemic conditions (acidic pH) can favor SNO formation from nitrite [21, 50], and hypoxia has been proposed to enhance complex I S-nitrosation [51], it is known that typical laboratory lighting conditions can degrade SNOs. Therefore, we examined the effects of light vs. dark on the recovery of Langendorff perfused rat hearts subjected to IR injury (laboratory light spectrum shown in Figure 6B). Figure 6A shows typical recordings of cardiac function during IR, with the quantitative results in Figure 6C indicating that post-IR recovery of rate pressure product (RPP) was significantly enhanced in the dark, i.e. a condition which preserves SNO. This effect is probably mediated via endothelial NO• synthase (eNOS) -derived NO•, since blood vessels are transparent in colloid-perfused rat hearts, and visible light cannot penetrate the myocardium. Further work is required to fully characterize the endogenous light-sensitive species responsible for cardioprotection, but nevertheless these data are useful because they demonstrate the importance of proper experimental control over light levels when working with S-nitrosothiols.

Figure 6. Endogenous S-nitrosothiols, cardioprotection, & effects of light.

(A): Langendorff perfused hearts were subject to 25 min. ischemia and 30 min. reperfusion as described in the methods. Typical recordings of left ventricular pressure (LVP) are shown, with the time axis compressed, such that the upper and lower boundaries of the black shaded areas represent the boundaries of systolic (Sys) and diastolic (Dia) pressures, as indicated by the arrows. The times of onset of ischemia and reperfusion are indicated by “Isch” and “Rpf” arrows respectively. (B): Ambient laboratory light spectrum at the site of the heart in the Langendorff perfusion apparatus. (C): Post-IR recovery of rate pressure product (RPP, heart rate multiplied by LV developed pressure (systolic minus diastolic)), for hearts subjected to IR in light vs. dark conditions. Values were calculated from traces of the type shown in panel A, and are expressed as percentage of the pre-ischemic RPP value. Data are means ± SEM of at least 5 independent experiments. *p<0.05 between groups. (D): Biotin switch analysis. Left panel: mitochondria isolated from hearts that underwent normoxic perfusion (Ctrl), or IPC followed by ischemia only (no reperfusion). Right panel: as in left panel, with inclusion of a sample of mitochondria treated with SNO-MPG (cf. Fig. 4). All procedures including mitochondrial isolation were performed in the dark, as detailed in the methods. Blots are representative of at least 3 independent experiments, and numbers to the left are molecular weight markers (kDa).

Production of NO• by eNOS is elevated during IPC [15, 16], leading us to hypothesize that IPC could enhance endogenous mitochondrial S-nitrosation during ischemia. Indeed, we previously showed that mitochondria isolated from hearts subjected to IPC followed by ischemia (all in the dark) contained 17 ± 3 pmol SNO per mg protein [27], whereas mitochondria isolated from hearts that underwent ischemia alone contained only 8 ± 1 pmol of SNO per mg protein (current study). Consistent with results in mitochondria isolated from cells (Figure 5F), mitochondrial SNO was not detectable in normoxic perfused hearts or those subjected to IPC or ischemia under ambient laboratory lighting.

Since chemiluminescent SNO analysis on whole mitochondrial pellets does not illustrate the distribution of specific SNO peptides, a biotin switch analysis was performed to examine the targets of mitochondrial S-nitrosation in IPC. The data in Figure 6D (left panel) indicate that similar patterns of S-nitrosation were seen in mitochondria isolated from IPC hearts, compared to isolated mitochondria or cells treated with SNO-MPG (cf. Figures 4B and 4D), with prominent bands at 25, 40, 55, and 77 kDa. The right panel shows control and SNO-MPG treated mitochondria, plus mitochondria from an IPC heart all on the same gel, allowing comparison of S-nitrosated bands between the different conditions, and indicating several common bands in the IPC and SNO treated samples. Together these data suggest that agents such as SNO-MPG may augment an endogenous S-nitrosation pathway triggered in IPC. Consistent with the reversal of complex I inhibition seen upon reperfusion (Figure 5D), mitochondrial S-nitrosation in IPC was also reversible; SNO was not detectable in mitochondria from hearts subjected to 30 min. reperfusion following IPC and ischemia (not shown).

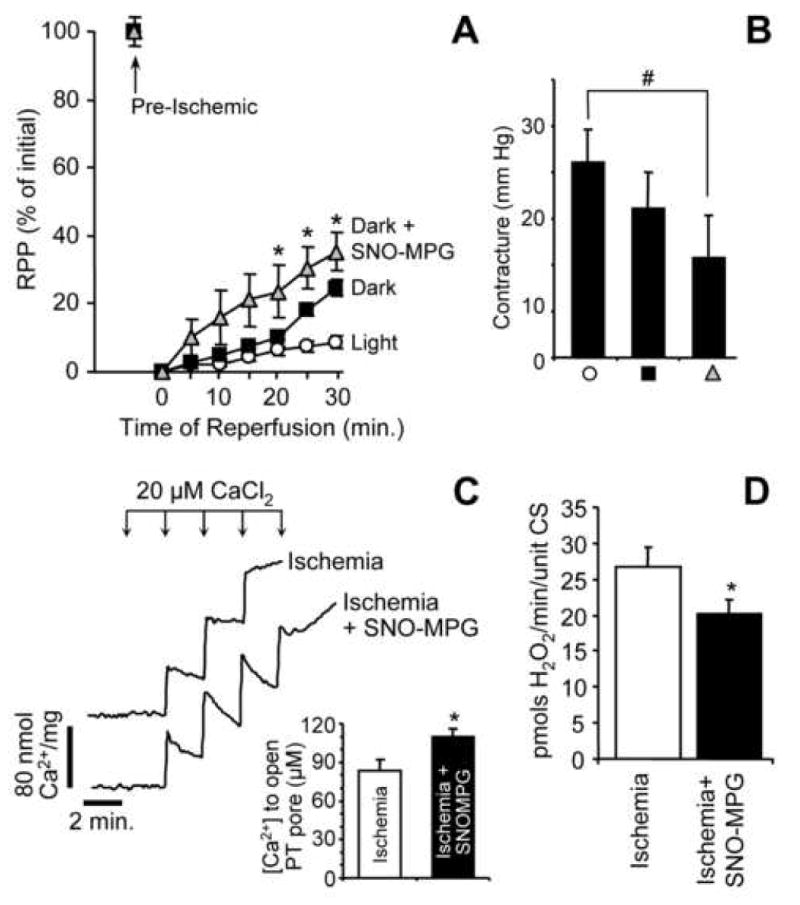

SNO-MPG protects the heart from IR

To see whether exogenous SNO administration by SNO-MPG could elicit cardioprotection at the whole organ level, perfused rat hearts were exposed to IR injury in the dark, with a sub-set of hearts treated with 10 μM SNO-MPG for 20 min. prior to ischemia. Both improved recovery of RPP (Figure 7A) and a decrease in ischemic hypercontracture (Figure 7B) were seen in the SNO-MPG pretreated hearts. These data support the hypothesis that enhancing mitochondrial S-nitrosation is protective in IR injury. Notably, the protective dose of SNO-MPG (10μM) was significantly lower than doses of the parent thiol (MPG) previously required for cardioprotection in perfused hearts (0.3 – 1 mM) [33].

Figure 7. Effect of SNO-MPG on cardiac recovery from IR injury, and on mitochondrial pathologic parameters at the end of ischemia.

(A): Heart perfusions were performed as described in the methods, and post-IR recovery of RPP is expressed as a percentage of the pre-ischemic level within each group. Experimental treatments were: control in the light (open circles), control in the dark (black squares), SNO-MPG in the dark (gray triangles). SNO-MPG was perfused at 10 μM for 20 min. prior to ischemia. Data are means ± SEM for at least 5 independent experiments. *p<0.05 between dark, and dark plus SNO-MPG groups. (B): Magnitude of hypercontracture sustained during ischemia, in each of the 3 groups shown in Panel A (same symbols). Hypercontracture was defined as the mean diastolic pressure during the final 5 min. of ischemia, minus the mean diastolic pressure during the first 10 min. of ischemia (see panel 6A). #p<0.05 between groups indicated. (C): Effect of SNO-MPG treatment prior to ischemia on Ca2+ handling properties of mitochondria isolated at the end of ischemia. Typical Arsenazo III traces for mitochondria from control vs. SNO-MPG treated hearts are shown. Inset shows the amount of added Ca2+ required for PT pore opening to occur (indicated in the traces by a failure of mitochondria to take up and hold Ca2+, resulting in its release and an upwards deflection in the trace). Data in inset are means ± SEM of 4 independent experiments. (D): Effect of SNO-MPG treatment prior to ischemia on ROS generation by mitochondria isolated at the end of ischemia. ROS generation was measured in the presence of complex I linked substrates (glutamate plus malate), using the Amplex red reagent as detailed in the methods. Data are means ± SEM of 4 independent experiments.

To probe the potential mechanisms by which SNO-MPG may elicit cardioprotection, mitochondria were isolated from hearts subject to ischemia (no reperfusion) with or without SNO-MPG pre-treatment, and their Ca2+ uptake and ROS generation characteristics were measured. Figure 7C shows the Ca2+ uptake of post-ischemic mitochondria determined using Arsenazo III, which measures external Ca2+. A rapid rise in [Ca2+]out was observed following Ca2+ addition to the cuvet, followed by a decrease in signal due to mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake. Surprisingly, mitochondria from the SNO-MPG treated hearts took up Ca2+ at a faster rate than controls, but they were able to tolerate a higher Ca2+ load before opening of the PT pore (indicated by an upwards deflection in the trace due to Ca2+ release). In addition Figure 7D shows that post-ischemic mitochondria from SNO-MPG treated hearts generated less ROS than controls, when respiring on complex I-linked substrates. No significant difference in ROS generation from complex III was observed (i.e. with succinate plus rotenone, data not shown). These results contrast with a previous finding of increased ROS generation upon mitochondrial S-nitrosation [52]. However, the doses of SNO used in that study (1 mM) were far higher (vs. 10 μM herein), and the model systems are different (adding SNO to isolated mitochondria vs. administering SNO to perfused hearts then isolating mitochondria after ischemia).

Overall, consistent with the data in Figure 5D showing that SNO-MPG inhibits complex I during the critical late-ischemia / early-reperfusion time window, the data in Figure 7 suggest that improvement of Ca2+ handling and inhibition of ROS generation at this time may be important downstream effects, linking complex I inhibition to cardioprotection.

Discussion

The main findings of this study are that SNO-MPG enhances mitochondrial S-nitrosation, inhibits complex I, and protects both cardiomyocytes and perfused hearts from IR injury. In addition the finding that mitochondrial proteins are endogenously S-nitrosated in IPC suggests that reversible S-nitrosation and inhibition of complex I may be an innate cardioprotective mechanism, amenable to pharmacologic augmentation.

Currently a consensus exists that low levels of NO• are cardioprotective [16, 53–55]. However, NO• signaling is pleiotropic, such that for example NO• mediated coronary vasodilatation would be beneficial in IR, but concurrent systemic vasodilatation would decrease pre-load and after-load, thereby impeding cardiac output. In an attempt to overcome such side-effects, the present study focused on enhancing mitochondrial S-nitrosation as a cardioprotective mechanism, using the reagent SNO-MPG. Due to its antioxidant properties, the free thiol MPG has previously been used as a cardioprotective agent in isolated myocytes and perfused hearts, although high doses (0.4–1 mM) were required to elicit protection [33, 34, 45, 56–59]. In the current study SNO-MPG (but not MPG) protected myocytes and hearts from IR injury at 10–20 μM, and it is proposed that this protection originated from enhanced delivery of SNO to the mitochondrion.

Several pieces of evidence support a primary mitochondrial effect of SNO-MPG, including: (i) ∼500 fold accumulation of MPG and ∼300-fold accumulation of SNO-MPG into isolated mitochondria. (ii) Preferential localization of SNO in mitochondria following treatment of cells with SNO-MPG (Figure 4 and Table 2). (iii) Direct evidence for S-nitrosation of complex I in mitochondria isolated from SNO-MPG treated cells (Figure 4E). (iv) Inhibition of complex I activity and respiration by SNO-MPG in intact cells (Figure 5). (v) The lack of effect of ODQ indicating no role for cGMP signaling in SNO-MPG-mediated cardioprotection (Figure 2). (vi) The observation that the parent thiol MPG accumulates in mitochondria when administered systemically [32]. (vii) Suggestion of a role for the pyruvate transporter in mitochondrial SNO-MPG accumulation. (viii) The effects of SNO-MPG on post-ischemic mitochondrial Ca2+ handling and ROS generation in perfused hearts (Figure 7). (ix) The observation that SNO-MPG cardioprotection is sensitive to light, at a time when low molecular weight SNO is depleted (Figures 2B and 5C). Together, these observations support the preliminary classification of SNO-MPG as a mitochondrial S-nitrosating agent. The remainder of this discussion will focus on the possible mechanisms of SNO-MPG action at the mitochondrial level in IR injury, and the implications of this study for endogenous cardioprotective mechanisms.

We recently observed that complex I can be reversibly inhibited via S-nitrosation of its 75kDa subunit, and that mitochondria from hearts subject to IPC contained S-nitrosothiols [27]. Coupling these observations with the proposed critical role of NO• in IPC [16, 55], and the demonstration that manipulation of experimental variables to enhance SNO stability (i.e. turning off the lights) improves recovery of perfused hearts from IR injury (Figure 6), we hypothesized that reversible S-nitrosation and inhibition of complex I may be an endogenous cardioprotective mechanism [27]. Herein we extend these findings to show that patterns of endogenous S-nitrosation in IPC are similar to those seen with SNO-MPG treatment (Figure 6D)., and that SNO-MPG resulted in complex I inhibition (Figure 5A), complex I S-nitrosation (Figure 4E), and respiratory inhibition (Figure 5B), with the latter being insensitive to the NO• scavenger cPTIO, meaning it was not due to inhibition by NO• binding at complex IV. Overall these data suggest that complex I is a target for S-nitrosation and inhibition in both endogenous IPC and SNO-MPG mediated cardioprotection.

Given the critical role of mitochondria in cardiac energetics, respiratory inhibition may appear paradoxical as a mechanism of cell protection. However, it has recently been shown that complex I inhibition may underlie the cardioprotective effects of agents such as amobarbital [29, 30], volatile anesthetics [60], and ranolazine [61]. Complex II inhibitors such as diazoxide [60] and 3-nitropropionic acid [62, 63] are also cardioprotective, as are complex IV inhibitors such as hydrogen sulfide [64, 65] and carbon monoxide [66]. In addition it is reported that glycolysis is inhibited in IPC [67], and it is known that a key regulator of glycolysis, GAPDH, is a target for S-nitrosation [68]. Together, these observations support an emerging paradigm that reversible metabolic inhibition may be a common pathway leading to cardioprotection. Such a pathway would result in slow re-introduction of electrons to the respiratory chain at the onset of reperfusion. A similar mechanism may underlie the cardioprotective benefits of slow-reperfusion or postconditioning [69].

The link between respiratory inhibition, slow electron re-introduction, and cardioprotection is elusive, but likely involves inhibition of pathologic events such as mitochondrial Ca2+ overload, ROS generation and PT pore opening, which occur at the end of ischemia/onset of reperfusion [1, 70, 71]. Although the effects of SNO-mediated complex I inhibition on Δψm were not determined, it is to be expected that complex I inhibition would decrease Δψm, which would inhibit Ca2+ overload and ROS generation. The notion of decreased Δψm in SNO-MPG treatment may at first appear contradictory to the data in Figure 3, showing an increased Δψm at the end of reperfusion in SNO-MPG treated cells. However, careful attention should be paid to the issue of timing; a small decrease in Δψm during ischemia is proposed to be protective, whereas a greater Δψm at the end of reperfusion (Figure 3) is indicative of enhanced recovery of mitochondrial function.

Inhibition of these events is proposed to underlie the cardioprotective effects of mitochondrial K+ATP channel opening [7], uncoupling protein activation [10, 11], Na+/H+ exchange inhibitors [72], Na+/Ca2+ exchange inhibitors [73], mitochondrial Ca2+ uniporter inhibitors [74], and mitochondrially targeted ROS scavengers [75, 76]. In support of such a mechanism, SNO-MPG delivered prior to ischemia significantly improved mitochondrial Ca2+ handling, inhibited ROS generation, and inhibited complex I, at the end of ischemia (Figures 5E & 7). The exact mechanism linking complex I inhibition to improved Ca2+ tolerance is not known, although it is expected that the former would elicit build-up of NADH in the mitochondrial matrix, possibly shifting mitochondria redox to a more reduced state (e.g. greater GSH/GSSG ratio), which would inhibit PT pore opening [1].

Despite the mitochondrial effects of SNO-MPG observed herein, it cannot be precluded that this agent may also elicit protection via S-nitrosation of other cellular targets. Indeed, several proteins involved in Ca2+ and redox signaling are known to be modified by S-nitrosation, including L-type Ca2+ channels [77], ryanodine receptors [78], thioredoxin [79] hemoglobin [80], mitochondrial K+ATP channels [81, 82], TRP channels [83], and caspases [26]. The relative importance of complex I as a mediator of the cardioprotective effects of NO• remains to be determined.

The effectiveness of SNO-MPG as a cardioprotective agent in-vivo is not known, although the expected metabolites of SNO-MPG are NO• and MPG. The latter is FDA approved for human clinical use [84], and therefore the in-vivo toxicology of SNO-MPG is expected to be similar to that of MPG. We consider it unlikely that the beneficial effects of SNO-MPG are mediated by MPG, since the concentrations of the latter required for cardioprotection are in the mM range [33, 34, 45, 56–59]. In addition, mM levels of MPG have been shown to be detrimental to IPC signaling, by scavenging ROS [12, 59], but it is unlikely that 10 μM SNO-MPG would release sufficient MPG to elicit such effects.

A limitation of the current study is the lack of mechanistic proof that complex I S-nitrosation is responsible for cardioprotection by IPC or SNO-MPG. In this regard, we know that: (i) complex I inhibitors are cardioprotective, (ii) SNO-MPG is cardioprotective, (iii) SNO-MPG S-nitrosates and inhibits complex I inside cardiomyocytes, (iv) SNO-MPG inhibits ROS generation and improves mitochondrial Ca2+ handling at the end of ischemia (v) IPC leads to mitochondrial S-nitrosation, and (vi) recovery from IR injury is enhanced in SNO preserving conditions. Despite the synergy between these events, a cause-and-effect link between them is missing. Current obstacles to such a mechanistic link include the low sensitivity of S-nitrosothiol proteomic methods, the significant decomposition of S-nitrosothiols during mitochondrial isolation, and the lack of genetic tools for manipulation of mitochondrial complex I in mammals. Future technical advances may resolve such issues.

In summary, the current study provides support for the hypothesis that mitochondrial protein S-nitrosation, particularly at the level of complex I, is an endogenous mechanism of cardioprotection during IPC. Such a mechanism may underlie the cardioprotective effects of diverse agents such as SNO-MPG, NO• donors [16], and nitrite [21, 50, 85–87].

Acknowledgments

We thank David Hoffman, Sarah Young, Dhananjaya Nauduri, and Leif Olson (Rochester) for technical assistance. This work was funded by a grant to PSB from the National Institutes of Health (HL71158).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Literature Cited

- 1.Brookes PS, Yoon Y, Robotham JL, Anders MW, Sheu SS. Calcium, ATP, and ROS: a mitochondrial love-hate triangle. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2004;287:C817–C833. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00139.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hausenloy DJ, Yellon DM. The mitochondrial permeability transition pore: its fundamental role in mediating cell death during ischaemia and reperfusion. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2003;35:339–41. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2828(03)00043-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Crompton M. The mitochondrial permeability transition pore and its role in cell death. Biochem J. 1999;341:233–49. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Di Lisa F, Bernardi P. Mitochondria and ischemia-reperfusion injury of the heart: Fixing a hole. Cardiovasc Res. 2006;70:191–9. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2006.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Murry CE, Jennings RB, Reimer KA. Preconditioning with ischemia: a delay of lethal cell injury in ischemic myocardium. Circulation. 1986;74:1124–36. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.74.5.1124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gross GJ, Fryer RM. Sarcolemmal versus mitochondrial ATP-sensitive K+ channels and myocardial preconditioning. Circ Res. 1999;84:973–9. doi: 10.1161/01.res.84.9.973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liu Y, Sato T, Seharaseyon J, Szewczyk A, O'Rourke B, Marban E. Mitochondrial ATP-dependent potassium channels. Viable candidate effectors of ischemic preconditioning. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1999;874:27–37. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1999.tb09222.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Costa AD, Quinlan CL, Andrukhiv A, West IC, Jaburek M, Garlid KD. The direct physiological effects of mitoKATP opening on heart mitochondria. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2006;290:H406–H415. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00794.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brookes PS. Mitochondrial H+ leak and ROS generation: an odd couple. Free Radic Biol Med. 2005;38:12–23. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2004.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nadtochiy SM, Tompkins AJ, Brookes PS. Different mechanisms of mitochondrial proton leak in ischemia-reperfusion injury and preconditioning: implications for pathology and cardioprotection. Biochem J. 2006;395:611–8. doi: 10.1042/BJ20051927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McLeod CJ, Aziz A, Hoyt RF, Jr, McCoy JP, Jr, Sack MN. Uncoupling proteins 2 and 3 function in concert to augment tolerance to cardiac ischemia. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:33470–6. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M505258200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lebuffe G, Schumacker PT, Shao ZH, Anderson T, Iwase H, Vanden Hoek TL. ROS and NO trigger early preconditioning: relationship to mitochondrial KATP channel. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2003;284:H299–H308. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00706.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Javadov SA, Clarke S, Das M, Griffiths EJ, Lim KH, Halestrap AP. Ischaemic preconditioning inhibits opening of mitochondrial permeability transition pores in the reperfused rat heart. J Physiol. 2003;549:513–24. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2003.034231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hausenloy D, Wynne A, Duchen M, Yellon D. Transient mitochondrial permeability transition pore opening mediates preconditioning-induced protection. Circulation. 2004;109:1714–7. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000126294.81407.7D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bell RM, Yellon DM. The contribution of endothelial nitric oxide synthase to early ischaemic preconditioning: the lowering of the preconditioning threshold. An investigation in eNOS knockout mice. Cardiovasc Res. 2001;52:274–80. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(01)00394-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jones SP, Bolli R. The ubiquitous role of nitric oxide in cardioprotection. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2006;40:16–23. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2005.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Laude K, Favre J, Thuillez C, Richard V. NO produced by endothelial NO synthase is a mediator of delayed preconditioning-induced endothelial protection. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2003;284:H2053–H2060. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00627.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bolli R. Cardioprotective function of inducible nitric oxide synthase and role of nitric oxide in myocardial ischemia and preconditioning: an overview of a decade of research. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2001;33:1897–918. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.2001.1462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ma XL, Gao F, Liu GL, Lopez BL, Christopher TA, Fukuto JM, et al. Opposite effects of nitric oxide and nitroxyl on postischemic myocardial injury. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:14617–22. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.25.14617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jneid H, Leessar M, Bolli R. Cardiac preconditioning during percutaneous coronary interventions. Cardiovasc Drugs Ther. 2005;19:211–7. doi: 10.1007/s10557-005-2466-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Duranski MR, Greer JJ, Dejam A, Jaganmohan S, Hogg N, Langston W, et al. Cytoprotective effects of nitrite during in vivo ischemia-reperfusion of the heart and liver 55. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:1232–40. doi: 10.1172/JCI22493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang G, Liem DA, Vondriska TM, Honda HM, Korge P, Pantaleon DM, et al. Nitric oxide donors protect murine myocardium against infarction via modulation of mitochondrial permeability transition. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2005;288:H1290–H1295. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00796.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Carver J, Doctor A, Zaman K, Gaston B. S-nitrosothiol formation. Methods Enzymol. 2005;396:95–105. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(05)96010-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hess DT, Matsumoto A, Kim SO, Marshall HE, Stamler JS. Protein S-nitrosylation: purview and parameters. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2005;6:150–66. doi: 10.1038/nrm1569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hogg N. The biochemistry and physiology of S-nitrosothiols. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2002;42:585–600. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.42.092501.104328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mannick JB, Schonhoff C, Papeta N, Ghafourifar P, Szibor M, Fang K, et al. S-Nitrosylation of mitochondrial caspases. J Cell Biol. 2001;154:1111–6. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200104008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Burwell LS, Nadtochiy SM, Tompkins AJ, Young S, Brookes PS. Direct evidence for S-nitrosation of mitochondrial complex I. Biochem J. 2006;394:627–34. doi: 10.1042/BJ20051435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Clementi E, Brown GC, Feelisch M, Moncada S. Persistent inhibition of cell respiration by nitric oxide: crucial role of S-nitrosylation of mitochondrial complex I and protective action of glutathione. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:7631–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.13.7631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chen Q, Hoppel CL, Lesnefsky EJ. Blockade of Electron Transport before Cardiac Ischemia with the Reversible Inhibitor Amobarbital Protects Rat Heart Mitochondria. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2006;316:200–7. doi: 10.1124/jpet.105.091702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chen Q, Camara A, Stowe DF, Hoppel CL, Lesnefsky EJ. Modulation of electron transport protects cardiac mitochondria and decreases myocardial injury during ischemia and reperfusion. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2006 doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00270.2006. In Press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Konorev EA, Joseph J, Tarpey MM, Kalyanaraman B. The mechanism of cardioprotection by S-nitrosoglutathione monoethyl ester in rat isolated heart during cardioplegic ischaemic arrest. Br J Pharmacol. 1996;119:511–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1996.tb15701.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chiba T, Kitoo H, Toshioka N. Studies on thiol and disulfide compounds. I. Absorption distribution metabolism and excretion of 35S-2-mercaptopropionylglycine. Yakugaku Zasshi. 1973;93:112–8. doi: 10.1248/yakushi1947.93.1_112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tanonaka K, Iwai T, Motegi K, Takeo S. Effects of N-(2-mercaptopropionyl)-glycine on mitochondrial function in ischemic-reperfused heart. Cardiovasc Res. 2003;57:416–25. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(02)00698-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tripathi Y, Hegde BM, Rai YS, Raghuveer CV. Effect of N-2-mercaptopropionylglycine in limiting myocardial reperfusion injury following 90 minutes of ischemia in dogs. Indian J Physiol Pharmacol. 2000;44:290–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dai L, Brookes PS, Darley-Usmar VM, Anderson PG. Bioenergetics in cardiac hypertrophy: mitochondrial respiration as a pathological target of NO•. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2001;281:H2261–H2269. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2001.281.6.H2261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tompkins AJ, Burwell LS, Digerness SB, Zaragoza C, Holman WL, Brookes PS. Mitochondrial dysfunction in cardiac ischemia-reperfusion injury: ROS from complex I, without inhibition. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2006;1762:223–31. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2005.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lowry OH, Rosebrough NJ, Farr AL, Randall RJ. Protein measurement with the Folin phenol reagent. J Biol Chem. 1951;193:265–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gladwin MT, Wang X, Reiter CD, Yang BK, Vivas EX, Bonaventura C, et al. S-Nitrosohemoglobin is unstable in the reductive erythrocyte environment and lacks O2/NO-linked allosteric function. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:27818–28. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M203236200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Brookes PS, Salinas EP, Darley-Usmar K, Eiserich JP, Freeman BA, Darley-Usmar VM, et al. Concentration-dependent effects of nitric oxide on mitochondrial permeability transition and cytochrome c release. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:20474–9. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M001077200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Borutaite V, Mildaziene V, Brown GC, Brand MD. Control and kinetic analysis of ischemia-damaged heart mitochondria: which parts of the oxidative phosphorylation system are affected by ischemia? Biochim Biophys Acta. 1995;1272:154–8. doi: 10.1016/0925-4439(95)00080-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jekabsone A, Dapkunas Z, Brown GC, Borutaite V. S-nitrosothiol-induced rapid cytochrome c release, caspase activation and mitochondrial permeability transition in perfused heart. Biochem Pharmacol. 2003;66:1513–9. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(03)00506-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Konorev EA, Tarpey MM, Joseph J, Baker JE, Kalyanaraman B. S-nitrosoglutathione improves functional recovery in the isolated rat heart after cardioplegic ischemic arrest-evidence for a cardioprotective effect of nitric oxide. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1995;274:200–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Claycomb WC, Palazzo MC. Culture of the terminally differentiated adult cardiac muscle cell: a light and scanning electron microscope study. Dev Biol. 1980;80:466–82. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(80)90419-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Brookes PS, Digerness SB, Parks DA, Darley-Usmar V. Mitochondrial function in response to cardiac ischemia-reperfusion after oral treatment with quercetin. Free Radic Biol Med. 2002;32:1220–8. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(02)00839-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Becker LB, Vanden Hoek TL, Shao ZH, Li CQ, Schumacker PT. Generation of superoxide in cardiomyocytes during ischemia before reperfusion. Am J Physiol. 1999;277:H2240–H2246. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1999.277.6.H2240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Jaffrey SR. Detection and characterization of protein nitrosothiols. Methods Enzymol. 2005;396:105–18. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(05)96011-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Borutaite V, Morkuniene R, Brown GC. Nitric oxide donors, nitrosothiols and mitochondrial respiration inhibitors induce caspase activation by different mechanisms. FEBS Lett. 2000;467:155–9. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(00)01140-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Brown GC, Borutaite V. Inhibition of mitochondrial respiratory complex I by nitric oxide, peroxynitrite and S-nitrosothiols. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2004;1658:44–9. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2004.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Brookes PS, Shiva S, Patel RP, Darley-Usmar VM. Measurement of mitochondrial respiratory thresholds and the control of respiration by nitric oxide. Methods Enzymol. 359:305–19. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(02)59194-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ng ES, Jourd'heuil D, McCord JM, Hernandez D, Yasui M, Knight D, et al. Enhanced S-nitroso-albumin formation from inhaled NO during ischemia/reperfusion. Circ Res. 2004;94:559–65. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000117771.63140.D6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Frost MT, Wang Q, Moncada S, Singer M. Hypoxia accelerates nitric oxide-dependent inhibition of mitochondrial complex I in activated macrophages. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2005;288:R394–R400. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00504.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Borutaite V, Brown GC. S-nitrosothiol inhibition of mitochondrial complex I causes a reversible increase in mitochondrial hydrogen peroxide production. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2006;1757:562–6. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2006.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Schulz R, Kelm M, Heusch G. Nitric oxide in myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury. Cardiovasc Res. 2004;61:402–13. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2003.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Jugdutt BI. Nitric oxide and cardioprotection during ischemia-reperfusion. Heart Fail Rev. 2002;7:391–405. doi: 10.1023/a:1020718619155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Cohen MV, Yang XM, Downey JM. Nitric oxide is a preconditioning mimetic and cardioprotectant and is the basis of many available infarct-sparing strategies. Cardiovasc Res. 2006;70:231–9. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2005.10.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Horwitz LD, Fennessey PV, Shikes RH, Kong Y. Marked reduction in myocardial infarct size due to prolonged infusion of an antioxidant during reperfusion. Circulation. 1994;89:1792–801. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.89.4.1792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Fuchs J, Veit P, Zimmer G. Uncoupler- and hypoxia-induced damage in the working rat heart and its treatment. II. Hypoxic reduction of aortic flow and its reversal. Basic Res Cardiol. 1985;80:231–40. doi: 10.1007/BF01907899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Vanden-Hoek T, Becker LB, Shao ZH, Li CQ, Schumacker PT. Preconditioning in cardiomyocytes protects by attenuating oxidant stress at reperfusion. Circ Res. 2000;86:541–8. doi: 10.1161/01.res.86.5.541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Tanaka M, Fujiwara H, Yamasaki K, Sasayama S. Superoxide dismutase and N-2-mercaptopropionyl glycine attenuate infarct size limitation effect of ischaemic preconditioning in the rabbit. Cardiovasc Res. 1994;28:980–6. doi: 10.1093/cvr/28.7.980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hanley PJ, Mickel M, Loffler M, Brandt U, Daut J. KATP channel-independent targets of diazoxide and 5-hydroxydecanoate in the heart. J Physiol. 2002;542:735–41. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2002.023960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wyatt KM, Skene C, Veitch K, Hue L, McCormack JG. The antianginal agent ranolazine is a weak inhibitor of the respiratory complex I, but with greater potency in broken or uncoupled than in coupled mitochondria. Biochem Pharmacol. 1995;50:1599–606. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(95)02042-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ockaili RA, Bhargava P, Kukreja RC. Chemical preconditioning with 3-nitropropionic acid in hearts: role of mitochondrial KATP channel. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2001;280:H2406–H2411. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2001.280.5.H2406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Turan N, Csonka C, Csont T, Giricz Z, Fodor G, Bencsik P, et al. The role of peroxynitrite in chemical preconditioning with 3-nitropropionic acid in rat hearts. Cardiovasc Res. 2006;70:384–90. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2005.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Pan TT, Feng ZN, Lee SW, Moore PK, Bian JS. Endogenous hydrogen sulfide contributes to the cardioprotection by metabolic inhibition preconditioning in the rat ventricular myocytes. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2006;40:119–30. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2005.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Khan AA, Schuler MM, Prior MG, Yong S, Coppock RW, Florence LZ, et al. Effects of hydrogen sulfide exposure on lung mitochondrial respiratory chain enzymes in rats. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 1990;103:482–90. doi: 10.1016/0041-008x(90)90321-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Stein AB, Guo Y, Tan W, Wu WJ, Zhu X, Li Q, et al. Administration of a CO-releasing molecule induces late preconditioning against myocardial infarction. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2005;38:127–34. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2004.10.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Vogt AM, Poolman M, Ackermann C, Yildiz M, Schoels W, Fell DA, et al. Regulation of glycolytic flux in ischemic preconditioning. A study employing metabolic control analysis. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:24411–9. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M201138200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Vedia L, McDonald B, Reep B, Brune B, Di SM, Billiar TR, et al. Nitric oxide-induced S-nitrosylation of glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase inhibits enzymatic activity and increases endogenous ADP-ribosylation. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:24929–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Sun HY, Wang NP, Kerendi F, Halkos M, Kin H, Guyton RA, et al. Hypoxic postconditioning reduces cardiomyocyte loss by inhibiting ROS generation and intracellular Ca2+ overload. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2005;288:H1900–H1908. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01244.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kim JS, Jin Y, Lemasters JJ. Reactive oxygen species, but not Ca2+ overloading, trigger pH-and mitochondrial permeability transition-dependent death of adult rat myocytes after ischemia-reperfusion. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2006;290:H2024–H2034. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00683.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Griffiths EJ, Halestrap AP. Mitochondrial non-specific pores remain closed during cardiac ischaemia, but open upon reperfusion. Biochem J. 1995;307:93–8. doi: 10.1042/bj3070093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Digerness SB, Brookes PS, Goldberg SP, Katholi CR, Holman WL. Modulation of mitochondrial adenosine triphosphate-sensitive potassium channels and sodium-hydrogen exchange provide additive protection from severe ischemia-reperfusion injury. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2003;125:863–71. doi: 10.1067/mtc.2003.110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Wang J, Zhang Z, Hu Y, Hou X, Cui Q, Zang Y, et al. SEA0400, a novel Na+/Ca2+ exchanger inhibitor, reduces calcium overload induced by ischemia and reperfusion in mouse ventricular myocytes. Physiol Res. 2006 doi: 10.33549/physiolres.930894. In Press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Hardy L, Clark JB, Darley-Usmar VM, Smith DR, Stone D. Reoxygenation-dependent decrease in mitochondrial NADH:CoQ reductase (Complex I) activity in the hypoxic/reoxygenated rat heart. Biochem J. 1991;274:133–7. doi: 10.1042/bj2740133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Zhao K, Zhao GM, Wu D, Soong Y, Birk AV, Schiller PW, et al. Cell-permeable peptide antioxidants targeted to inner mitochondrial membrane inhibit mitochondrial swelling, oxidative cell death, and reperfusion injury. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:34682–90. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M402999200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Adlam VJ, Harrison JC, Porteous CM, James AM, Smith RA, Murphy MP, et al. Targeting an antioxidant to mitochondria decreases cardiac ischemia-reperfusion injury. FASEB J. 2005;19:1088–95. doi: 10.1096/fj.05-3718com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Sun J, Picht E, Ginsburg KS, Bers DM, Steenbergen C, Murphy E. Hypercontractile female hearts exhibit increased S-nitrosylation of the L-type Ca2+ channel α1 subunit and reduced ischemia/reperfusion injury. Circ Res. 2006;98:403–11. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000202707.79018.0a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Eu JP, Sun J, Xu L, Stamler JS, Meissner G. The skeletal muscle calcium release channel: coupled O2 sensor and NO signaling functions. Cell. 2000;102:499–509. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00054-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Haendeler J, Hoffmann J, Tischler V, Berk BC, Zeiher AM, Dimmeler S. Redox regulatory and anti-apoptotic functions of thioredoxin depend on S-nitrosylation at cysteine 69. Nat Cell Biol. 2002;4:743–9. doi: 10.1038/ncb851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]