Abstract

In addition to classic Smad signaling pathways, the pleiotropic immunoregulatory cytokine TGF-β1 can activate MAP kinases, but a role for TGF-β1-MAP kinase pathways in T cells has not been defined heretofore. We have shown previously that TGF-β1 inhibits Th1 development by inhibiting IFN-γ’s induction of T-bet and other Th1 differentiation genes, and that TGF-β1 inhibits receptor-proximal IFN-γ-Jak-Stat signaling responses. We now show that these effects of TGF-β1 are independent of the canonical TGF-β1 signaling module Smad3, but involve a specific MAP kinase pathway. In primary T cells, TGF-β1 activated the MEK/ERK and p38 MAP kinase pathways, but not the JNK pathway. Inhibition of the MEK/ERK pathway completely eliminated the inhibitory effects of TGF-β1 on IFN-γ responses in T cells, whereas inhibition of the p38 pathway had no effect. Thus, TGF-β1’s inhibition of IFN-γ signaling in T cells is mediated through a highly specific Smad3-independent, MEK/ERK-dependent signaling pathway.

1. Introduction

IFN-γ is an important cytokine involved in the induction and regulation of a variety of immune responses including the establishment of Th1 differentiation (Grogan and Locksley, 2002). IFN-γ promotes the development of the Th1 phenotype through the enhanced expression in T cells of several genes encoding proteins critical for Th1 differentiation. These include T-bet, important for chromatin remodeling at the IFNG gene locus and establishment of high cellular IFN-γ expression (Szabo et al., 2000), interferon regulatory factor-1 (IRF-1), critical for cross-suppression of the Th2 effector phenotype (Elser et al., 2002), and the β2 subunit of the IL-12 receptor (IL-12Rβ2), ensuring the maintenance of T cell responsiveness to IL-12 (Szabo et al., 1997). IFN-γ’s enhancement of expression of these genes depends upon JAK-STAT signaling, specifically the tyrosine phosphorylations of JAK1, JAK2, and STAT1. Tyrosine phosphorylated STAT1 homodimers translocate to the nucleus, where they positively regulate the transcriptional expression of target genes (Schindler and Darnell, 1995) such as those encoding T-bet, IRF-1, and IL-12Rβ2. Fully differentiated Th1 effector cells are important for cell-mediated immune responses against a variety of pathogens and tumors. Appropriate regulation of Th1 differentiation is critical, however, and unrestrained Th1 responses contribute to autoimmune pathology.

TGF-β1 is a pleiotropic cytokine that is essential as an immunosuppressant factor, as mice deficient in TGF-β1 spontaneously develop a lethal multifocal Th1 inflammatory disorder (Shull et al., 1992). Target organs in TGF-β1−/− mice accumulate activated Th1 cells (Gorham et al., 2001), and end organ damage is dependent both upon the CD4+ T cell subset (Letterio et al., 1996; Rudner et al., 2003), and the Th1 cytokine IFN-γ (Gorham et al., 2001). Tissues from TGF-β1−/− mice show evidence of constitutive IFN-γ signaling (McCartney-Francis and Wahl, 2002), indicating that TGF-β1 normally acts to inhibit IFN-γ signaling. IFN-γ and TGF-β1 are antagonistic cytokines that regulate Th1 development in opposite directions. Unraveling the molecular mechanisms that form the basis for the antagonistic relationship between these two cytokines is important for understanding the delicate balance between tolerance and autoimmunity. IFN-γ interferes with TGF-β1 responses through several mechanisms, including induced expression of Smad7, and inhibitor of TGF-β1 signaling, and Stat1-mediated nuclear sequestration of the co-activator molecule CBP/p300, interfering with Smad-mediated transcription (Ghosh et al., 2001; Ulloa et al., 1999).

By contrast, little is known about how TGF-β1 interferes with cellular responses to IFN-γ. Recently, we showed that TGF-β1 inhibits IFN-γ signaling and the induction of IRF-1 and T-bet mRNA in primary murine CD4+ T cells (Park et al., 2005). Understanding the interaction between these two cytokines in CD4+ T cells at initial TCR priming is important. TGF-β1 and IFN-γ exert much of their potent immunomodulatory effects by influencing T cell responses, including T helper cell subset differentiation, early in the course of the generation of the adaptive immune response. Our previous studies identified the SH2 domain-containing protein tyrosine phosphatase (PTP) -1 (SHP-1) as an essential intermediate in the inhibitory effects of TGF-β1 on IFN-γ-responses in T cells. Specifically, TGF-β1 is unable to inhibit IFN-γ signaling and gene induction in CD4+ T cells isolated from SHP-1-deficient moth-eaten-viable mice (Park et al., 2005).

The binding of TGF-β1 to its receptor initiates several signaling pathways. The classical TGF-β1 signaling pathway proceeds via the activation of Smad proteins. Upon binding of TGF-β1 to its cell surface receptor complex, the type II TGF-β receptor phosphorylates the type I TGF-β receptor and activates its kinase function. The activated type I TGF-β receptor then serine phosphorylates the intracellular Smad family proteins Smad2 and Smad3. Phosphorylated Smad2 and Smad3 form complexes with Smad4, and Smad heterocomplexes then translocate to the nucleus where they function as transcription factors regulating gene expression (Derynck et al., 1998). Smad3 is responsible for many TGF-β1-induced responses in T cells (McKarns et al., 2004; Yang et al., 1999). Although the Smad pathway is considered the principal signaling pathway for TGF-β1, TGF-β1 also engages other pathways. The MAPK pathways (MEK/ERK, p38, and JNK) are among the signaling pathways activated by TGF-β1 in a variety of cell types (Derynck and Zhang, 2003).

In the present study, we examine which TGF-β1-induced pathways are important for the inhibitory effects of TGF-β1 on IFN-γ responses in T cells. This question is particularly important as TGF-β1’s inhibition of proximal IFN-γ signaling occurs rapidly (within 15 minutes) and does not require new protein synthesis (Park et al., 2005). We have addressed the role of Smad3 and of the MAP kinase pathways. We demonstrate here that inhibition of IFN-γ responses and Th1 gene induction by TGF-β1 in CD4+ T cells is independent of Smad3, but dependent upon the MEK/ERK MAP kinase pathway.

2. Materials and methods

2.1 Reagents

PD98059, SB202190, and UO126 (Calbiochem, Germany) were dissolved in DMSO and used at a final concentration of 20.0 μM. Recombinant IFN-γ and TGF-β1 proteins were obtained from Peprotech (Rocky Hill, NJ) and R&D systems (Minneapolis, MN), respectively.

2.2 Mice

BALB/c mice were purchased from the National Cancer Institute (Frederick, MD) and maintained in accredited Dartmouth Medical School animal care facility. BALB/c-background mice with a targeted deletion in the SMAD3 gene (Smad3−/−) and littermate control mice (Smad3+/+) were raised at the National Cancer Institute. Mice were genotyped for SMAD3 at the NIH by one of the authors (JJL) as described in Yang et al., 1999.

2.3 Cell culture and CD4+ T cell isolation

Mouse spleens and lymph nodes were dissected and collected cells were resuspended in RPMI 1640 (Mediatech, Herndon, VA). Mononuclear cells were isolated using Ficoll (Histopaque 1119, Sigma). CD4+ T cells were isolated by positive selection via magnetic beads as described in Park et al., 2005. CD4+ T cells (5 × 105 to 106 cells) were plated for 24 hours on immobilized anti-CD3 antibody (145-2C11, BD Pharmingen, San Diego, CA) (2 μg/ml) with soluble anti-CD28 antibody (37.51, BD Pharmingen) (1 μg/ml). Cells were washed, rested for 2 hours without anti-CD3/anti-CD28, and treated with IFN-γ (50 ng/ml) and/or TGF-β1 (5 ng/ml) for various times, as indicated in the figure legends.

2.4 Retroviral transfection and T cell expression of a dominant negative MEK1 mutant

Retroviral plasmid vectors encoding a dominant negative form of MEK1 (S217A) and a control vector (eGFP only) were kindly provided by Dr. Christopher J. Marshall (Institute of Cancer Research, UK) (Mavria et al., 2006). CD4+ T cells were isolated and stimulated with anti-CD3/anti-CD28 mAbs for 24 h and then infected with retroviral supernatants prepared from transfected Phoenix cells, as described (Lin et al., 2005). After an additional two days of incubation, cells were harvested and resuspended with serum-free medium, and replated. After an additional 2 h, IFN-γ and/or TGF-β1 were added to the cells and cells lysed after 10–40 minutes for Western Blot analysis. Epifluorescence analysis of eGFP-RV-infected cells indicated that the large majority of cells were fluorescent, indicating successful retroviral infection. (I-K Park, not shown).

2.5 Western blot analyses

Treated CD4+ T cells were lysed using sample buffer containing SDS and 2-ME. After boiling, samples were electrophoresed on a 10% polyacrylamide gel, transferred to nitrocellulose membrane, and then probed with antibodies. Antibodies against STAT1 (p84/p91) and JAK1 were from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA). Antibodies recognizing phosphotyrosine-STAT1 (Y701) and phosphotyrosine-JAK1 (Y1022/Y1023) were from Upstate (Charlottesville, VA) and Cell Signaling (Beverly, MA), respectively. HRP-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG secondary antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) was followed by detection using ECL (Amersham, UK).

2.6 RT-PCR

Cells were harvested and total RNA was isolated using the RNeasy kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). cDNA was generated from 1 μg of total RNA using the Omniscript kit (Qiagen) and subject to real-time PCR using the SYBR Green system (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). All values are shown after normalization to a β-actin control. Primer sequences and amplification conditions are as published (Park et al., 2005). Statistical analyses used Student’s t-test.

3. Results

3.1 TGF-β1’s suppression of IFN-γ responses in T helper cells is Smad3-independent

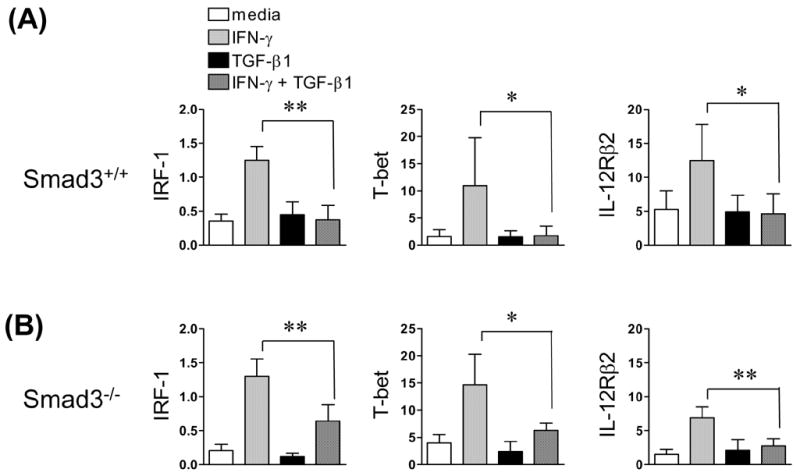

Smad3 mediates a number of TGF-β-induced transcriptional responses, and is required for the TGF-β1-mediated inhibition of TCR-induced CD4+ T cell proliferation (Datto et al., 1999; Derynck and Zhang, 2003; Yang et al., 1999). To test whether Smad3 is required for TGF-β1’s inhibition of IFN-γ responses in CD4+ T cells, we examined the effects of IFN-γ and TGF-β1, separately and together, on gene expression in CD4+ T cells isolated from Smad3−/− mice or from littermate control wild-type (Smad3+/+) mice. In wild-type CD4+ T cells, addition of IFN-γ to the culture media rapidly induced the expression of mRNAs encoding IRF-1, T-bet, and IL-12Rβ2. When added alone, TGF-β1 had no discernible effect on baseline expression, but when combined with IFN-γ, TGF-β1 significantly inhibited IFN-γ’s induction of the three genes (Fig. 1A). In Smad3−/− CD4+ T cells, the effects of IFN-γ and TGF-β1 were similar to their effects in control cells. That is, IFN-γ induced expression of the three genes, and, despite the absence of Smad3, TGF-β1 suppressed IFN-γ’s induction of these genes (Fig. 1B). Thus, in CD4+ T cells, IFN-γ induces expression of genes important for Th1 differentiation, and TGF-β1 suppresses these effects of IFN-γ through a pathway that does not require the canonical TGF-β1 signaling factor Smad3.

Fig. 1. TGF-β1 suppresses IFN-γ induced Th1 gene expression through a Smad3-independent pathway.

Splenic CD4+ T cells from BALB/c littermate wild-type (Smad3+/+) and Smad3−/− mice were isolated and stimulated for 24 hours with anti-CD3/anti-CD28. Cells were washed, rested for 2 h, and treated with IFN-γ and/or TGF-β1 for 3 h (Smad3+/+) or 6 h (Smad3−/−), respectively. Relative IRF-1, T-bet, and IL-12Rβ2 levels were measured by real-time RT-PCR, normalized to β-actin. Data show the mean + S.D derived from individually isolated, treated, and analyzed T cells from (A) Smad3+/+ mice (n = 6) and (B) Smad3−/− mice (n = 4). * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01. This experiment was repeated with similar results.

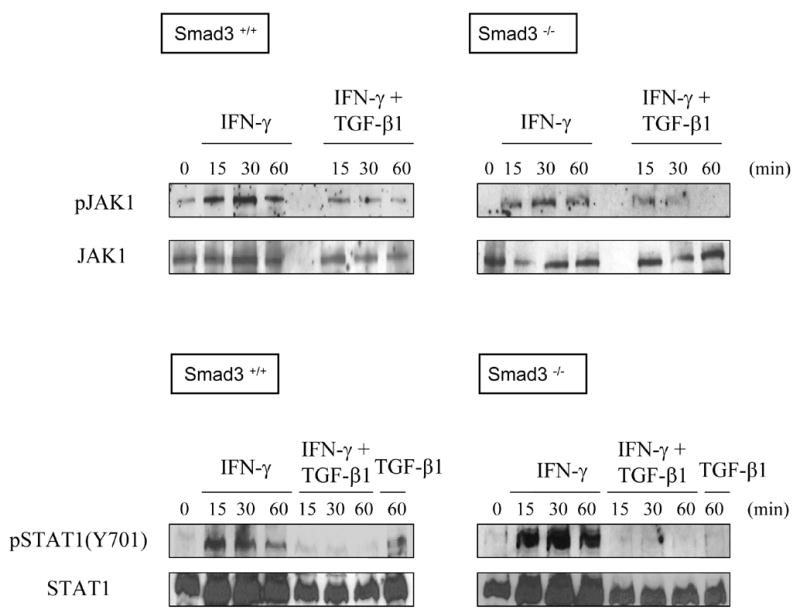

TGF-β1 inhibits IFN-γ-induced tyrosine phosphorylation of JAK1 and STAT1 (Park et al., 2005). To determine the requirement for Smad3 in these effects of TGF-β1, we analyzed receptor proximal signaling events. In wild-type CD4+ T cells, IFN-γ rapidly induced the tyrosine phosphorylation of JAK1 and of STAT1, as shown by Western Blot analysis using antibodies specific for the phosphorylated forms of the proteins (Fig 2). As expected (Park et al., 2005), TGF-β1 inhibited these IFN-γ-induced phosphorylation events. For Smad3−/− CD4+ T cells, results were similar to wild type; that is, IFN-γ induced the tyrosine phosphorylation of both JAK1 and STAT1, and TGF-β1 inhibited these phosphorylation events. We conclude, therefore, that TGF-β1 inhibits IFN-γ-inducible gene expression and the receptor proximal JAK/STAT pathway through pathway(s) that do not require Smad3.

Fig. 2. TGF-β1 suppresses receptor-proximal IFN-γ signaling in T helper cells through a Smad3-independent pathway.

Splenic CD4+ T cells from littermate Smad3+/+ or Smad3−/− mice were prepared as in the legend to Fig. 1 and treated with IFN-γ and/or TGF-β1 for the indicated times. Cell lysates were prepared and analyzed by western blot to detect phosphotyrosine-JAK1, total JAK1, phosphotyrosine-STAT1 (Y701), and total STAT1, respectively. This experiment was repeated with similar results.

3.2 TGF-β1 activates MAP kinase pathways in T helper cells

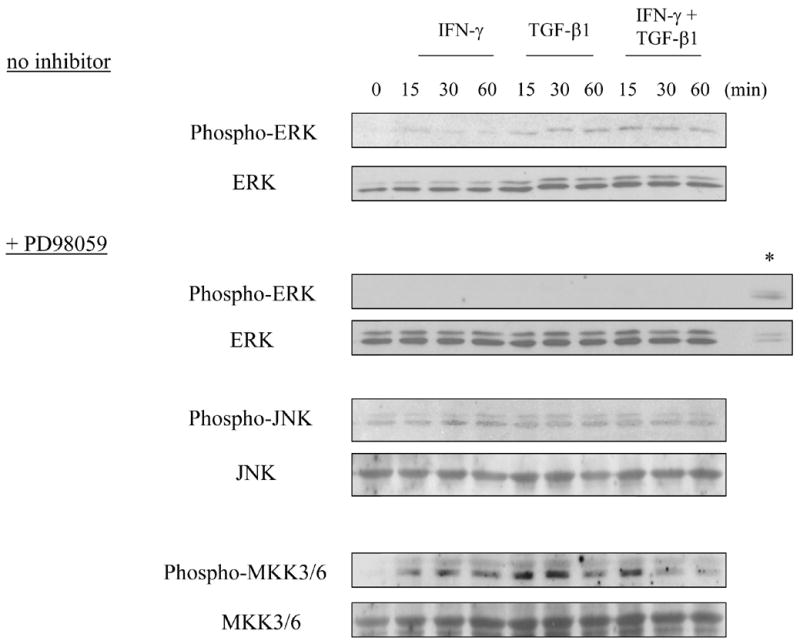

In several cell types, TGF-β1 can activate downstream signaling mechanisms that do not involve Smads (Derynck and Zhang, 2003), including the three main MAPK pathways, ERK, p38, and JNK. We considered the possibility that TGF-β1 utilizes one or more MAP kinase pathways to inhibit IFN-γ responses in CD4+ T cells. To our knowledge, the activation of MAP kinase pathways by TGF-β1 in CD4+ T cells has not been reported. To assess this, we treated primary CD4+ T cells with TGF-β1 (and/or IFN-γ) for 15–60 minutes, and tested cell lysates for evidence of MAP kinase activation. TGF-β1 (but not IFN-γ) rapidly induced the activation of the ERK pathway, as seen by the increase in phosphorylated ERK within 15 minutes of TGF-β1 treatment (Fig. 3). When T cells were pre-incubated with the compound PD98059, a specific inhibitor of the upstream ERK kinase MEK (Bommhardt et al., 2000; Hoffmeyer et al., 1999), the phosphorylation of ERK by TGF-β1 was completely inhibited, confirming the specificity of the effect of TGF-β1. TGF-β1 also activated the p38 pathway; as evidenced by the induced phosphorylation of MKK3/6, upstream kinases for p38 (notably, this pathway was unaffected by the presence of PD98059). Of note, the MKK3/6 phosphorylation was induced by IFN-γ as well, but the two cytokines did not appear to be additive or synergistic in this activity. As for the JNK pathway, this was not activated by TGF-β1. The phosphorylated form of JNK was detected even without added cytokine. Neither TGF-β1 nor IFN-γ enhanced JNK phosphorylation, at least in the time frame of this assay (within one hour). Thus, in murine CD4+ T cells, TGF-β1 activates the MEK/ERK and p38 MAP kinase pathways, but not the JNK pathway, whereas IFN-γ activates only the p38 pathway, but not the MEK/ERK or JNK pathways.

Fig. 3. TGF-β1 activates ERK and p38 MAP kinase pathways in T helper cells.

Splenic and LN CD4+ T cells were prepared as in Fig. 1, and treated with IFN-γ and/or TGF-β1 for 0 – 60 min before lysis. In some wells, cells were incubated for 30 min with PD98059 prior to cytokine addition, as indicated. Cell lysates were subject to western blot to detect phospho-ERK1/2, ERK1/2, phospho-JNK, JNK, phospho-MKK3/6, and MKK3/6, respectively. The asterisk (*) indicates a cell lysate from HeLa cells treated with CoCl2, as a positive control for phospho-ERK.

3.3 TGF-β1’s suppression of IFN-γ responses in T helper cells is MEK/ERK-dependent

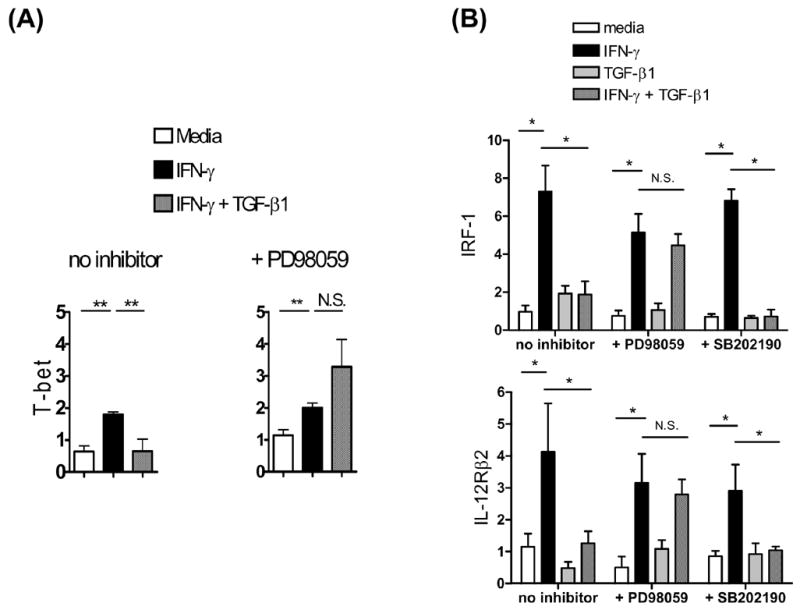

To determine whether the MEK/ERK or p38 pathways are responsible for TGF-β1’s effects here, we tested the effects of specific pharmacologic inhibitors to these two pathways. In control conditions, IFN-γ induced, and TGF-β1 suppressed, the expression of T-bet (Fig. 4A), IRF-1 and IL-12Rβ2 (Fig. 4B), as before. In the presence of the MEK/ERK pathway specific inhibitor PD98059, IFN-γ induced expression of these genes, but TGF-β1 did not inhibit their induction (Fig. 4A, 4B). The effect of PD98059 cannot be attributed to cross-inhibition of the other MAPK pathways, as the phosphorylation of JNK and of MKK3/6 remained intact in the presence of PD98059 (Fig. 3). In the presence of the p38-pathway-specific inhibitor SB202190, TGF-β1’s ability to inhibit IFN-γ induced gene expression was unaffected (Fig. 4B). These results indicate that TGF-β1 suppresses IFN-γ-induced gene expression in CD4+ T cells through the MEK/ERK pathway, but not through the p38 pathway. An additional observation from this experiment is that although IFN-γ activates the p38 pathway, this pathway appears to be irrelevant for IFN-γ’s induction of IRF-1 and IL-12Rβ2, which were induced even in the presence of the p38 inhibitor SB202190.

Fig. 4. TGF-β1 suppresses IFN-γ induced Th1 gene expression through a MEK/ERK-dependent pathway.

Splenic and LN CD4+ T cells from BALB/c mice were prepared and stimulated as in Fig. 1. In some wells, cells were incubated with PD98059 (20 μM) or SB202190 (20 μM) for 30 min prior to cytokine addition. After 3 hr of cytokine stimulation, RNA was isolated and analyzed by real-time RT-PCR for (A) T-bet or (B) IRF-1, and IL-12Rβ2. Bars indicated the mean + SD of triplicate cell culture wells. * p < 0.05. ** p < 0.01. This experiment was repeated twice more with similar results.

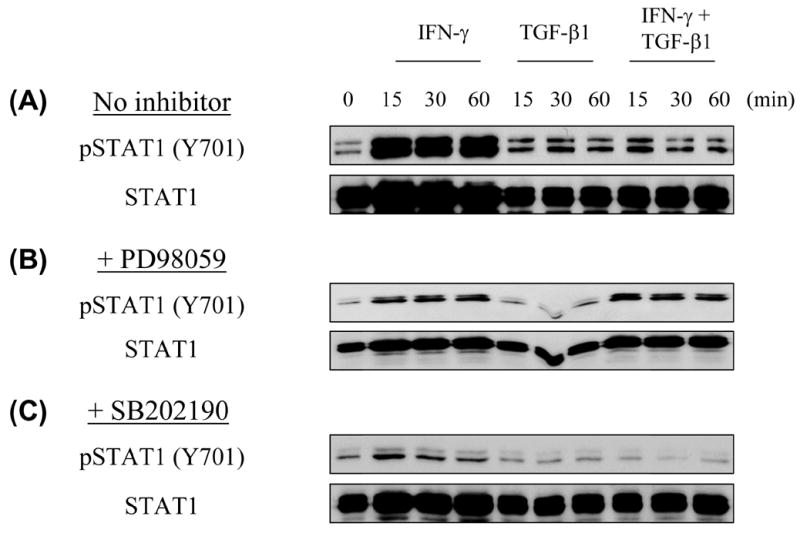

We next tested whether inhibition of MEK/ERK could abrogate the inhibitory effect of TGF-β1 on IFN-γ-induced STAT1 phosphorylation. In control conditions, IFN-γ induced the tyrosine phosphorylation of STAT1, and TGF-β1 inhibited the IFN-γ-induced phosphorylation of STAT1, as before (Fig. 5A). When cells were pre-treated with PD98059 to suppress MEK/ERK signaling, IFN-γ still induced STAT1 phosphorylation but now the addition of TGF-β1 no longer inhibited IFN-γ’s induction of STAT1 phosphorylation. As expected, TGF-β1 + PD98059 alone had no effect on STAT1 phosphorylation, indicating that the STAT1 phosphorylation observed in the presence of IFN-γ + TGF-β1 + PD98059 is specific to the presence of IFN-γ (Fig. 5B). By contrast to the effects of PD98059, pre-treatment of cells with the p38 MAP kinase inhibitor SB202190 did not influence the effects of either IFN-γ or TGF-β1 on STAT1 phosphorylation (Fig. 5C).

Fig. 5. TGF-β1 suppresses receptor-proximal IFN-γ signaling in T helper cells through a MEK/ERK-dependent pathway.

BALB/c CD4+ T cells were prepared and stimulated as in Fig. 1. In some wells, cells were incubated with PD98059 (20 μM) or SB202190 (20 μM) for 30 min prior to cytokine addition. After 0 – 60 minutes of cytokine stimulation, cell lysates were subject to Western Blot analysis for phosphotyrosine-STAT1 (Y701) or total STAT1. This experiment was repeated with similar results.

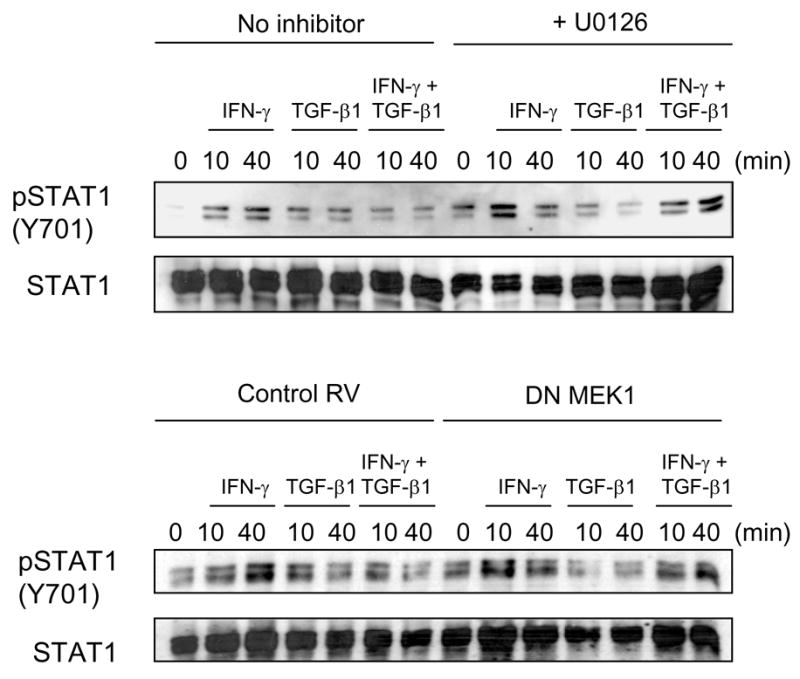

To confirm that TGF-β1 inhibits IFN-γ signaling through the MEK/ERK pathway, we took two additional experimental approaches. First, we used U0126, a specific pharmacologic inhibitor of MEK that is structurally unrelated to PD98059. Second, T cells were transfected with a retrovirus expressing a dominant negative form of MEK1. In both of these experimental conditions, TGF-β1 did not inhibit IFN-γ induced STAT1 phosphorylation; by contrast, in control vehicle-treated T cells, or control-retrovirus infected T cells, TGF-β1 inhibited IFN-γ induced STAT1 phosphorylation as before (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6. Additional experimental approaches confirm that TGF-β1’s effects are MEK/ERK-dependent.

BALB/c CD4+ T cells were prepared and stimulated as in Fig. 1. (Top) In some wells, cells were incubated with the MEK inhibitor UO126 (20 μM) for 30 min prior to cytokine addition. After 0 – 60 minutes of cytokine stimulation, cell lysates were prepared. (Bottom) BALB/c CD4+ T cells were stimulated overnight with anti-CD3/anti-CD28 then infected with a retrovirus expressing a dominant negative form of MEK1, or with a control retrovirus. After two additional days of incubation, cells were washed, replated, and treated with cytokines for the times indicated and cell lysates prepared. Cell lysates were subject to Western Blot analysis for phosphotyrosine-STAT1 (Y701) or total STAT1.

4. Discussion

In murine CD4+ T cells, TGF-β 1 inhibits IFN-γ-activated JAK/STAT signaling and Th1-specific gene induction through a pathway that does not require the classic TGF-β1 signaling protein Smad3. The lack of requirement for Smad3 in TGF-β1’s inhibition of IFN-γ effects is reminiscent of a recent report showing that Smad3 is dispensable for TGF-β1’s inhibition of effects of IL-2 (McKarns et al., 2004). Interestingly, both IFN-γ and IL-2 signal through JAK/STAT pathways, although each utilizes distinct STAT family members (Johnston et al., 1995). Whether Smad3 is generally dispensable for TGF-β1’s modulation of JAK-STAT signaling elicited by members of the hematopoietic cytokine family is an important issue that will need to be further evaluated. Likewise, the finding that the MEK/ERK pathway mediates TGF-β1’s inhibition of IFN-γ signaling should provide impetus to study the role of the MEK/ERK pathway in TGF-β1’s modulation of JAK-STAT signaling cascades induced by IL-2 or other cytokines. While Smad3 is dispensable for TGF-β1’s inhibition of IFN-γ and IL-2 responses, it clearly is important for many of the T cell immunomodulatory activities of TGF-β1. Smad3-deficient T cells exhibit an activated phenotype in vivo (Yang et al., 1999). Whereas Smad3 is dispensable in the inhibition of IL-2-mediated effects, Smad3 is nevertheless essential for TGF-β1’s inhibition of TCR-induced T lymphocyte proliferation and IL-2 production (McKarns et al., 2004). Our studies do not rule out a role for other Smad proteins (e.g. Smad2 or Smad4). As mice with targeted disruption of either the SMAD2 or SMAD4 genes do not survive to birth (Dunker and Krieglstein, 2000; Heyer et al., 1999), the mouse reagents to test their roles in mediating effects of TGF-β1 in primary T cells are not readily available. The development of mice with T cell specific conditional deletions of these genes should provide a way to experimentally circumvent this problem (Kim et al., 2006).

Since Smad3 was dispensable for the effects of TGF-β1 on IFN-γ responses in CD4+ T cells, we examined additional signaling pathways that could mediate TGF-β1’s effects. TGF-β1 has been known to activate the MAP kinase pathways in other (non-immune cells). Assessing these pathways in primary T cells, we found that TGF-β1 activates the MEK/ERK and p38 pathways but not the JNK pathway. As far as we are aware, this constitutes the first report of TGF-β1’s activation of MAP kinase pathways in lymphocytes. Through the use of pharmacologic inhibitors as well as a dominant negative MEK1 construct, we showed that the MEK/ERK pathway, but not the p38 pathway, is essential for TGF-β1’s inhibition of IFN-γ signaling. In CD4+ T cells, therefore, Smad3 is required for TGF-β1’s inhibition of TCR mediated events (15), whereas MEK/ERK (but not Smad3) is required for TGF-β1’s inhibition of IFN-γ signaling. Thus, distinct intracellular signaling pathways activated by TGF-β1 subserve specific functions in the regulation of T cells. This raises the intriguing possibility of targeted molecular intervention using pathway specific inhibitors to enhance or interfere with some immunoregulatory activities of TGF-β1 while preserving others.

We have reported a requirement for SHP-1 in TGF-β1’s suppression of IFN-γ signaling (Park et al., 2005). This may reflect a role for the SHP1 PTP in the rapid dephosphorylation of IFN-γ-activated, phosphorylated JAK1 and/or STAT1. Consistent with this model, pre-incubation of T cells with pervanadate, an inhibitor of protein tyrosine phosphatases (PTPs), abrogates TGF-β1’s ability to inhibit IFN-γ signaling (Park et al., 2005). Thus, both SHP1 (and its associated PTP activity) and the MEK/ERK pathway are necessary for TGF-β1 to inhibit the IFN-γ signaling pathway in T cells. The functional relationship between the SHP1 and MEK/ERK pathways in T cells is currently unknown. One possibility is that TGF-β1 activates SHP1 protein via a phosphorylation event mediated directly or indirectly by MEK/ERK. While it has been reported that SHP1 becomes phosphorylated in T cells in response to TGF-β1 (Choudhry et al., 2001), we have been unable to detect TGF-β1-induced phosphorylation of SHP1 (I–K Park, unpublished). Alternatively, SHP1 may be important for MEK/ERK activation. ERK activation by colony-stimulating factor-1 (CSF-1) is diminished in SHP1 deficient macrophages, indicating that SHP1 may link upstream Ras activation to downstream ERK activation (Krautwald et al., 1996). Also, the ERK and Smad pathways can intersect. In human epithelial cells, ERK mediates the phosphorylation of Smad family members in response to TGF-β, thereby regulating Smad subcellular localization, a key determinant in TGF-β-dependent transcriptional activation (Mulder, 2000).

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank R.J. Noelle, W.R. Green, and S.A. Brooks (all at Dartmouth Medical School) for helpful discussions. We thank C. Marshall (Institute of Cancer Research, U.K.) for generously sharing the retroviral vector encoding the dominant negative MEK1. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grants AI053056 (J.D.G.), DK073904 (J.D.G.), and P20RR16437 from the COBRE Program of the National Center for Research Resources (W.R. Green, Principal Investigator).

Abbreviations

- IRF-1

interferon regulatory factor-1

- IL-12Rβ2

β2 subunit of the IL-12 receptor

- SHP-1

SH2 domain-containing protein tyrosine phosphatase -1

- PTP

protein tyrosine phosphatase

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Bommhardt U, Scheuring Y, Bickel C, Zamoyska R, Hunig T. MEK activity regulates negative selection of immature CD4+CD8+ thymocytes. J Immunol. 2000;164:2326–37. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.5.2326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choudhry MA, Sir O, Sayeed MM. TGF-beta abrogates TCR-mediated signaling by upregulating tyrosine phosphatases in T cells. Shock. 2001;15:193–199. doi: 10.1097/00024382-200115030-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Datto MB, Frederick JP, Pan L, Borton AJ, Zhuang Y, Wang XF. Targeted disruption of Smad3 reveals an essential role in transforming growth factor beta-mediated signal transduction. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:2495–2504. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.4.2495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derynck R, Zhang Y, Feng XH. Smads: transcriptional activators of TGF-beta responses. Cell. 1998;95:737–40. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81696-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derynck R, Zhang YE. Smad-dependent and Smad-independent pathways in TGF-beta family signalling. Nature. 2003;425:577–584. doi: 10.1038/nature02006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunker N, Krieglstein K. Targeted mutations of transforming growth factor-beta genes reveal important roles in mouse development and adult homeostasis. Eur J Biochem. 2000;267:6982–8. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.2000.01825.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elser B, Lohoff M, Kock S, Giaisi M, Kirchhoff S, Krammer PH, Li-Weber M. IFN-gamma represses IL-4 expression via IRF-1 and IRF-2. Immunity. 2002;17:703–712. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(02)00471-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh AK, Yuan W, Mori Y, Chen S, Varga J. Antagonistic regulation of type I collagen gene expression by interferon-gamma and transforming growth factor-beta. Integration at the level of p300/CBP transcriptional coactivators. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:11041–11048. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M004709200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorham JD, Lin JT, Sung JL, Rudner LA, French MA. Genetic regulation of autoimmune disease: BALB/c background TGF-beta 1- deficient mice develop necroinflammatory IFN-gamma-dependent hepatitis. J Immunol. 2001;166:6413–6422. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.10.6413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grogan JL, Locksley RM. T helper cell differentiation: on again, off again. Curr Opin Immunol. 2002;14:366–72. doi: 10.1016/s0952-7915(02)00340-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heyer J, Escalante-Alcalde D, Lia M, Boettinger E, Edelmann W, Stewart CL, Kucherlapati R. Postgastrulation Smad2-deficient embryos show defects in embryo turning and anterior morphogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:12595–600. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.22.12595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmeyer A, Grosse-Wilde A, Flory E, Neufeld B, Kunz M, Rapp UR, Ludwig S. Different mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling pathways cooperate to regulate tumor necrosis factor alpha gene expression in T lymphocytes. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:4319–27. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.7.4319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston JA, Bacon CM, Finbloom DS, Rees RC, Kaplan D, Shibuya K, Ortaldo JR, Gupta S, Chen YQ, Giri JD, et al. Tyrosine phosphorylation and activation of STAT5, STAT3, and Janus kinases by interleukins 2 and 15. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92:8705–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.19.8705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim BG, Li C, Qiao W, Mamura M, Kasperczak B, Anver M, Wolfraim L, Hong S, Mushinski E, Potter M, Kim SJ, Fu XY, Deng C, Letterio JJ. Smad4 signalling in T cells is required for suppression of gastrointestinal cancer. Nature. 2006;441:1015–9. doi: 10.1038/nature04846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krautwald S, Buscher D, Kummer V, Buder S, Baccarini M. Involvement of the protein tyrosine phosphatase SHP-1 in Ras-mediated activation of the mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:5955–63. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.11.5955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Letterio JJ, Geiser AG, Kulkarni AB, Dang H, Kong L, Nakabayashi T, Mackall CL, Gress RE, Roberts AB. Autoimmunity associated with TGF-beta1-deficiency in mice is dependent on MHC class II antigen expression. J Clin Invest. 1996;98:2109–2119. doi: 10.1172/JCI119017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin JT, Martin SL, Xia L, Gorham JD. TGF-beta 1 uses distinct mechanisms to inhibit IFN-gamma expression in CD4+ T cells at priming and at recall: differential involvement of Stat4 and T-bet. J Immunol. 2005;174:5950–8. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.10.5950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mavria G, Vercoulen Y, Yeo M, Paterson H, Karasarides M, Marais R, Bird D, Marshall CJ. ERK-MAPK signaling opposes Rho-kinase to promote endothelial cell survival and sprouting during angiogenesis. Cancer Cell. 2006;9:33–44. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2005.12.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCartney-Francis NL, Wahl SM. Dysregulation of IFN-gamma signaling pathways in the absence of TGF-beta 1. J Immunol. 2002;169:5941–5947. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.10.5941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKarns SC, Schwartz RH, Kaminski NE. Smad3 is essential for TGF-beta 1 to suppress IL-2 production and TCR-induced proliferation, but not IL-2-induced proliferation. J Immunol. 2004;172:4275–4284. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.7.4275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulder KM. Role of Ras and Mapks in TGFbeta signaling. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2000;11:23–35. doi: 10.1016/s1359-6101(99)00026-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park IK, Shultz LD, Letterio JJ, Gorham JD. TGF-beta1 inhibits T-bet induction by IFN-gamma in murine CD4+ T cells through the protein tyrosine phosphatase Src homology region 2 domain-containing phosphatase-1. J Immunol. 2005;175:5666–74. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.9.5666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudner LA, Lin JT, Park IK, Cates JM, Dyer DA, Franz DM, French MA, Duncan EM, White HD, Gorham JD. Necroinflammatory liver disease in BALB/c background, TGF-beta 1-deficient mice requires CD4+ T cells. J Immunol. 2003;170:4785–92. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.9.4785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schindler C, Darnell JE., Jr Transcriptional responses to polypeptide ligands: the JAK-STAT pathway. Annu Rev Biochem. 1995;64:621–51. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.64.070195.003201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shull MM, Ormsby I, Kier AB, Pawlowski S, Diebold RJ, Yin M, Allen R, Sidman C, Proetzel G, Calvin D, Annunziata N, Doetschman T. Targeted disruption of the mouse transforming growth factor-beta 1 gene results in multifocal inflammatory disease. Nature. 1992;359:693–699. doi: 10.1038/359693a0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szabo SJ, Dighe AS, Gubler U, Murphy KM. Regulation of the interleukin (IL)-12R beta 2 subunit expression in developing T helper 1 (Th1) and Th2 cells. J Exp Med. 1997;185:817–824. doi: 10.1084/jem.185.5.817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szabo SJ, Kim ST, Costa GL, Zhang X, Fathman CG, Glimcher LH. A novel transcription factor, T-bet, directs Th1 lineage commitment. Cell. 2000;100:655–669. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80702-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ulloa L, Doody J, Massague J. Inhibition of transforming growth factor-beta/SMAD signalling by the interferon-gamma/STAT pathway. Nature. 1999;397:710–713. doi: 10.1038/17826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang X, Letterio JJ, Lechleider RJ, Chen L, Hayman R, Gu H, Roberts AB, Deng C. Targeted disruption of SMAD3 results in impaired mucosal immunity and diminished T cell responsiveness to TGF-beta. EMBO J. 1999;18:1280–1291. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.5.1280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]