Abstract

Youth substance use disorder treatment programs frequently advocate integration into 12-Step fellowships to help prevent relapse. However, the effects of the predominantly adult composition of 12-step groups on adolescent involvement and substance use outcome remain unstudied. Greater knowledge could enhance the specificity of treatment recommendations for youth. To this end, adolescents (N = 74; M age = 15.9, 62% female) were recruited during inpatient treatment and followed up 3 and 6 months later. Greater age similarity was found to positively influence attendance rates and the perceived importance of attendance, and was marginally related to increased step-work and less substance use. These preliminary findings suggest locating and directing youth to meetings where other youth are present may improve 12-step attendance, involvement, and substance use outcomes.

Keywords: Adolescent, substance use disorders, 12-step, alcohol treatment, drug treatment, addiction, self-help, mutual help, substance abuse

INTRODUCTION

Attendance at 12-step mutual-help groups by adolescents with substance use disorders (SUDs) is often prescribed by treatment providers as a means of maintaining treatment gains, yet remains an understudied phenomenon (Deas & Thomas, 2001). As with adult SUD treatment in the United States, the 12-Step or “Minnesota model” approach predominates among youth treatment providers (Jainchill, 2000). A principal goal and critical proximal outcome of this modality is attendance at and successful integration into 12-Step fellowships in order to prevent relapse.

The “12-Step treatment” modality was originally devised to help adults with substance use disorders. Extrapolation of adult-based interventions for youth treatment is a common initial strategy and some support exists for the utility of 12-step approaches for youth (e.g., Hsieh, Hoffman, & Hollister, 1998; Kelly, Myers, & Brown, 2000). However, criticisms have been raised regarding such extrapolation without sensitivity to developmental differences (e.g., Brown, 1993; Kaminer, 2001). Understanding the clinical ramifications of such differences may help enhance the efficiency and effectiveness of treatment prescriptions for youth.

A principal function of 12-Step group meetings is to provide fellowship support, through identification and a sense of belonging (Twelve Steps & Twelve Traditions, 1953). One important difference between adults and adolescents treated for SUDs is that even if teens are motivated to attend 12-step groups, the predominantly adult composition of most groups may hinder identification and present a barrier to continued attendance and affiliation. Demographic data from AA's latest triennial survey (Alcoholics Anonymous Membership Survey, 2001), revealed the average age of membership to be 46 years old, with only 2% under age 21. Age similarity may be particularly important for youth due to the influence of variables tied to their developmental status (Deas, Riggs, Langenbucher, Goldman & Brown, 2000). Youth who attend meetings may have lower perceived similarity to individual participants (Vik, Grizzle & Brown, 1992) and difficulty identifying with issues central (e.g., severity of substance dependence) and peripheral (e.g, employment concerns, marital relations) to recovery. Consequently, sharing of specific experiences by older members may not be perceived by youth as helpful or relevant in dealing with their own life-stage recovery issues. Such differences may diminish therapeutic gains associated with youth 12-step group attendance.

A number of studies have suggested that 12-Step groups may be helpful in adolescent change efforts (Brown, 1993; Kelly et al., 2000 Latimer, Newcomb, Winters & Stinchfield, 2000). However, despite widespread prescriptions for adolescent involvement in predominantly adult 12-Step organizations no studies to date have examined the impact of the age composition of attended groups on youth 12-Step involvement and substance use outcome. Such knowledge could help qualify and enhance the specificity of treatment recommendations for youth attendance at such groups.

This preliminary study examines the effect of 12-step meeting participants' age on adolescent 12-step attendance and involvement during the first 3 months following inpatient SUD treatment, and examines its' relation to substance use concurrently and in the ensuing 3 months. It is hypothesized that a greater degree of similarity in age of participants at meetings will be associated with more involvement in 12-Step related behaviors and less substance involvement.

METHOD

Setting and Sample

This study is based on a sample of 74 adolescents, recruited during inpatient substance abuse treatment, consecutively admitted at two “Minnesota model” programs in San Diego, California.

Adolescents between the ages of 14 and 18 were recruited into the study if they met DSM-IV criteria for a substance abuse or dependence diagnosis (American Psychiatric Association,1994). Diagnoses were determined by structured interview using the Customary Drinking and Drug Use Record (CDDR; Brown, Myers, Lippke, Tapert, Stewart & Vik, 1998). Other eligibility criteria were: (a) participation of a resource person to provide corroborative information; (b) living within 50 miles of the research facility; and (c) no history of psychotic symptoms, independent of substance use.

The original pool of eligible study participants was 127. Sixty-eight percent (n = 85) completed interviews and all questionnaires at both follow-up time points. Another 11 cases were excluded because of missing data. Univariate analyses between included and excluded cases revealed no significant differences on baseline measures of age, gender, ethnicity, socioeconomic status (SES), motivation for abstinence or number of days abstinent in the past 30 days at treatment intake (all p's > .12).

Participants were on average 16 years old (M = 15.9, SD = 1.19) with over half female (62%). The sample was primarily white (70%), and included Hispanics (18%), African Americans (8%) and Asian/Pacific Islanders (4%). The sample was comprised of polysubstance users, and the most frequently reported substances of choice included marijuana (42%), amphetamines (30%), and alcohol (13%).

Procedure

Following youth and parent informed consent and recruitment into the study, initial interviews were completed during hospitalization by research staff. Baseline and 6 month follow-up adolescent interviews were completed face to face; 3 month interviews were completed by phone. Youth were not paid for the initial interview, but were compensated $10 and $25 for the 3-month, and 6-month interviews respectively. More detailed descriptions can be found in other articles by Kelly and Myers.

Measures

Demographics

Age, ethnicity and gender were recorded using the Structured Clinical Interview for Adolescents (SCI; Brown, 1987).

Substance Involvement

Alcohol and other drug use frequency was measured using the Timeline Follow Back (TLFB) procedure (Sobell & Sobell, 1992) adapted for multiple substances. This procedure has shown to have high test-retest reliability, convergent and discriminant validity (Fals-Stewart, O'Farrell, Freitas, McFarlin, & Rutigliano, 2000).

Twelve-Step Involvement

Frequency of attendance at 12-Step meetings was evaluated using the TLFB technique (Sobell & Sobell, 1992). Other 12-step behaviors measured were: (1) “Do you have a sponsor”; (2) “Which of the 12-Steps have you worked”; (3) “How important is it to you to attend 12-Step meetings?” and, (4) “How often do you engage in 12-Step social activities outside of meetings?” These aspects of 12-Step organizations have been shown to be important (e.g., Humphreys, Kaskutas & Weisner, 1998).

Age Composition of Attended Meetings

This was assessed using a single item: “For the meetings you attended most often, how many of the people are teens?”, with responses ranging from “1” = “all adults” “2” = “mostly adults,” “3” = “even mix,” “4” = “mostly teen,” “5” = “all teen.”

RESULTS

12-Step Attendance

Nearly three quarters (71.6%) of the current sample attended at least one 12-Step meeting during the first three-month follow-up period, with average attendance slightly over twice per week (total M = 26.7, SD = 31.4). Just over half (51.8%) attended at least weekly with over one third (36.5%) attending twice per week or more, on average. During the second three-month follow-up period, just over half (54.1%) of the sample attended at least one 12-step meeting with the average attendance dropping considerably (M = 15.85, SD = 25.9). Less than one third (30.8%) of the sample attended at least once per week during the four through six month follow-up period with 20.3% attending 2 or more times per week (See Table 1). The relation between 12-step attendance during the first 3 months post discharge and substance use outcome measured concurrently and in the ensuing 3 month period, have been reported elsewhere (Kelly, Myers & Brown, 2002; r = .32, p = .003 and r = . 27, p = .01, respectively).

TABLE 1.

Rates of 12-Step Meeting Attendance and Abstinence

| Intake | 1-3m | 4-6m | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Days abstinent | 39% | 89% | 81% |

| Percent of sample completely abstinent* | 7% | 32.4% | 37.0% |

| Attended at least one 12-Step meeting | – | 71.6% | 54.1% |

| Attended 12-Step meetings at least weekly (on average) | – | 51.8% | 30.8% |

| Attended 12-Step Meetings at least twice weekly (on average) |

– | 36.5% | 20.3% |

| Mean (SD) 12-Step Meetings Attended | 0 | 26.7 (31.4) | 15.9 (25.9) |

At treatment intake the value reflects the past 30 days.

Effects of Age Composition of 12-Step Meetings

Since age composition of meetings was the focus of these analyses, those who had attended at least one 12-Step meeting during the first 3 months post treatment (n = 53) was used for these analyses. Examination of variable distributional characteristics revealed significantly non-normal distributions for substance use outcome variables at both follow up time points (1-3 month skew = −2.69; 4-6 month skew = −1.99). Transformations were insufficient to change distributional characteristics to meet assumptions for parametric analyses (Tabachnick & Fidel, 1996). Thus, non-parametric Spearman's rho correlations were computed.

Greater age similarity at meetings was related to more frequent meeting attendance (r = .24, p = .04), a higher rated importance of 12-step attendance (r = .26, p = .03), and was marginally related to greater involvement in working the 12 steps (r = .18, p = .09). In contrast, greater age similarity was not related to an increased likelihood of having a sponsor or engaging in social activities with 12-step members.

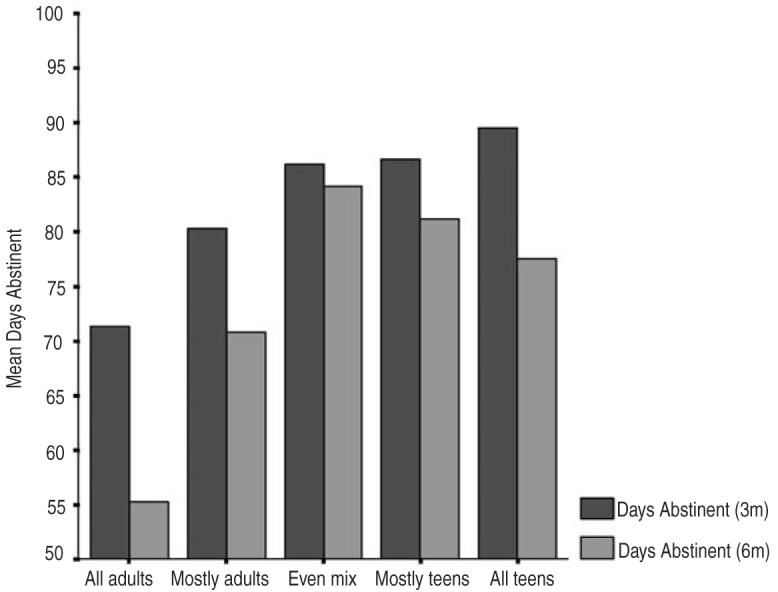

Correlational analyses examining the relation between age composition of attended groups and substance use outcome revealed that greater age similarity at the most frequently attended meetings during the first 3 months post treatment was not associated with lower rates of substance use during the same 3 month period. However, greater age similarity was marginally related to decreased substance use in the ensuing 3-month period (r = .18, p = .09). Figure 1 shows these relationships.

FIGURE 1.

Age composition of most frequently attended 12-step meetings in relation to substance use outcome

DISCUSSION

This preliminary study examined the relationship between the age composition of 12-Step groups and adolescent 12-step attendance and involvement and substance use outcome following inpatient treatment. General clinical recommendations call for initial attendance rates to be high, usually 2-3 per week. However, in the current sample only about one third attended at least twice weekly during the first 3 months and about 20% during the second 3-month follow-up period. The observed positive linear association between the adolescent makeup of attended groups and the frequency of youth 12-step meeting attendance suggests that the predominantly adult composition and content of 12-step groups may act as a barrier to more frequent youth attendance. Other barriers may be purely logistical in nature, such as dependence on parents for transportation to meetings. Thus, attendance may be further moderated by familial factors such as support and resources. Further study is needed to examine the impact of such barriers for youth.

In the larger sample (N = 74) more frequent 12-Step meeting attendance was shown to be associated with an increased likelihood of engaging in 12-step behaviors such as working the steps and having a sponsor (Kelly, Myers & Brown, 2002). These are presumed to be the mechanisms of change in such programs (Alcoholics Anonymous, 2001). Findings here suggest that youth attending 12-step meetings with more similar age peers present are more likely to view 12-Step attendance as important to their recovery efforts and possibly more likely involved in working the steps. Of note, greater age similarity was not associated with having a sponsor. Thus, sponsor acquisition appears to be more a function of frequent attendance and, perhaps, greater commitment, than age similarity at meetings. Also contrary to expectations, greater age similarity at attended meetings was not associated with greater involvement in 12-step social activities. This could reflect a restricted range in that 77% of the current sample did not report any engagement in 12-step social activities, which could be due to a lack of available events to attend. However, it still may be the case that youth are developing social connections at these groups, which are not restricted to more formal 12-step fellowship-organized social activities. Frequency of contact with other 12-step members outside of meetings was not assessed in this study, but should be examined in future research.

As mentioned earlier, prior studies have found that youth involvement in 12-step groups may reduce the frequency and severity of relapse (Hsieh et al., 1998). However, of further clinical significance was the finding that the age-composition of groups attended by youth during the first 3 months post treatment was associated with reductions in substance use in the following 3-month period. Although insufficient statistical power precluded analyses to detect the unique effects of age composition over and above frequency of attendance, the nature of this relationship suggests that age similarity may not only positively influence intended proximal outcomes of 12-step treatment modalities (i.e., greater 12-step attendance and affiliation), but may also positively influence ultimate substance use outcomes of youth. The interrelations between these variables warrant further study with larger samples. It may be that greater similarity in background and experiences that a youth may have with other peers at meetings (e.g., Vik et al., 1992) may prove more influential than other peer groups (e.g., school friends) who may be generally supportive, but unable to provide abstinence-specific support.

For several reasons, the current findings must be interpreted cautiously. The small sample size may have affected the precision of parameter estimates as well as the statistical power to detect true effects; replication with larger samples should be undertaken. Also, the dropout rate and missing data raise generalizability issues. However, these concerns are at least partially ameliorated by a failure to find any systematic differences between dropouts and retained subjects on important baseline variables. In addition, because the early weeks and months following inpatient treatment require the most demanding adjustment, the initial 6 months post-treatment was the focus of the current study. Longer prospective follow-ups could help elucidate the impact of group participants' age on adolescent 12-step involvement, substance use outcomes and broader psychosocial functioning in the transition to adulthood. Given the modest relations detected, other factors (e.g., distance to meetings, transportation resources) may play a role in the level of 12-step affiliation and attendance.

If replicated with other youth, the preliminary findings here suggest age similarity to other 12-Step mutual-help group members may be a factor in meeting the intended adolescent 12-Step treatment outcome goals of ongoing attendance and involvement in 12-step mutual-help groups. For clinicians and healthcare providers encouraging youth to attend fellowships such as AA and NA, determining the location of, and directing youth to meetings where other youth are present may facilitate continued youth attendance and lead to improved substance use outcomes. Future research with larger samples should also examine the unique effects of age similarity on 12-step attendance rates and fellowship involvement (e.g., acquiring and using a sponsor; speaking at meetings) and related effects on the frequency and intensity of post-treatment relapse.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by grants from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (R01AA-07033), the Health Services Research & Development Service of the Department of Veterans Affairs, and the National Institute on Drug Abuse (R29 DA-09181).

REFERENCES

- Alcoholics Anonymous . The story of how many thousands of men and women have recovered from alcoholism. Fourth Edition AA World Services Inc; New York: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Alcoholics Anonymous 2001 Membership Survey . AA Grapevine Inc; New York: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association . Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4th ed. American Psychiatric Press; Washington, D.C.: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Brown SA. Alcohol use and type of life events experienced during adolescence. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 1987;1(2):104–107. [Google Scholar]

- Brown SA. Recovery patterns in adolescent substance abuse. In: Baer JS, Marlatt GA, editors. Addictive behaviors across the life span: Prevention, treatment, and policy issues. Sage Publications, Inc; Thousand Oaks, CA: 1993. pp. 161–183. [Google Scholar]

- Brown S, Myers M, Lippke L, Tapert S, Stewart D, Vik PW. Psychometric evaluation of the Customary Drinking and Drug Use Record (CDDR): A measure of adolescent alcohol and drug involvement. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1998;59(4):427–438. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1998.59.427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deas D, Thomas SE. An overview of controlled studies of adolescent substance abuse treatment. Am J Addict. 2001;10(2):178–189. doi: 10.1080/105504901750227822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deas D, Riggs P, Langenbucher J, Goldman M, Brown S. Adolescents are not adults: Developmental considerations in alcohol users. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2000;24(2):232–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fals-Stewart W, O'Farrell TJ, Freitas TT, McFarlin SK, Rutigliano P. The Timeline Followback reports of psychoactive substance use by drug-abusing patients: Psychometric properties. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2000;68(1) doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.68.1.134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh S, Hoffman NG, Hollister DC. The Relationship between pre-, during-, post-treatment factors, and adolescent substance abuse behaviors. Addictive Behaviors. 1998;23(4):477–488. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(98)00028-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Humphreys K, Kaskutas L, Weisner C. The Alcoholics Anonymous Affiliation Scale: Development, reliability, and norms for diverse treated and untreated populations. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1998;22(5):974–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1998.tb03691.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jainchill N. Substance dependency treatment for adolescents: Practice and research. Substance Use & Misuse. 2000;35(1214):2031–60. doi: 10.3109/10826080009148249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaminer Y. Alcohol & drug abuse: Adolescent substance abuse treatment: where do we go from here? Psychiatr Serv. 2001;52(2):147–149. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.52.2.147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly JF, Myers MG, Brown SA. A multivariate process model of adolescent 12-step attendance and substance use outcome following inpatient treatment. Psychol Addict Behav. 2000;14(4):376–389. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly JF, Myers MG, Brown SA. Do Adolescents Affiliate with 12-Step Groups? A Multivariate Process Model of Effects. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2002;63(3):293–304. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2002.63.293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kingree JB. Measuring affiliation with 12-step groups. Substance Use & Misuse. 1997;32(2) doi: 10.3109/10826089709027306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Latimer W, Newcomb M, Winters K, Stinchfield R. Adolescent substance abuse treatment outcome: The role of substance abuse problem severity, psychosocial, and treatment factors. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2000;68(4):684–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobell L, Sobell M. Timeline follow-back: A technique for assessing self-reported alcohol consumption. In: Litten JR, Allen, editors. Measuring Alcohol Consumption. The Human Press; Totowa, NJ: 1992. pp. 41–72. [Google Scholar]

- Tabachnick BG, Fidell LS. Using Multivariate statistics. 3rd Edition Harper Collins; New York: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Twelve Steps & Twelve Traditions . Alcoholics Anonymous. Grapevine Inc; New York, NY: 1953. [Google Scholar]

- Vik PW, Grizzle KL, Brown SA. Social resource characteristics and adolescent substance abuse relapse. Journal of Adolescent Chemical Dependency. 1992;2:59–74. [Google Scholar]