Abstract

The health professions need to spearhead a concerted intersectoral response to obesity, say Sharon Friel, Mickey Chopra, and David Satcher

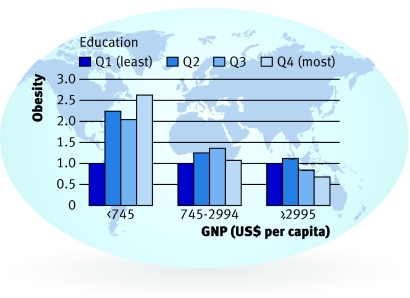

Obesity is a global problem, unequally distributed between and within countries. In affluent societies excess weight is more common among socially disadvantaged groups,1 but the inverse is true in low income countries (fig 1).2

Fig 1 Age standardised prevalence ratio for obesity in women in low, lower-middle, and upper-middle income economies, 1992-2000 (Source: Montiero et al)

Summary points

The global obesity epidemic is unequally distributed within and between countries

It is being fuelled by economic and psychosocial factors as well as increased availability of energy dense food and reduced physical activity

Tackling it requires concerted action at national and international level to promote a more equal distribution of affordable nutritious food, and improved, more equitable, living and working conditions

Obesity and its unequal distribution is a consequence of the complex system operating at global, national, and local levels, shaping how we trade, live, learn, and work. Focusing only on direct action to make people eat more healthily and be more physically active misses the heart of the problem: the underlying unequal distribution of factors that support the opportunity to be a healthy weight. Unless this oversight is addressed the obesity epidemic and its inequities will persist and possibly increase.

A change in diet towards highly refined foods and meat and dairy products containing high levels of saturated fats has been occurring globally since the middle of the 20th century. This, together with marked reductions in energy expenditure, is believed to have contributed to the rise in levels of obesity.3 Of concern in this paper are the causes of, and solutions to, these large scale changes in diet and physical activity and their unequal social distribution.

Who cares?

Dealing with inequalities in obesity requires a different policy agenda from the one currently being promoted. Action is needed that is grounded in principles of health equity. Not infrequently the medical community operates as a vanguard for progressive changes in health and social policy—for example, the US surgeon general’s call in 2001 to prevent and decrease overweight and obesity was driven by physicians.4 Similarly, key ingredients for success of the Framework Convention on Tobacco Control included leadership from clinicians, the World Health Organization, and the British Medical Association.5

What’s causing the energy imbalance between and among societies?

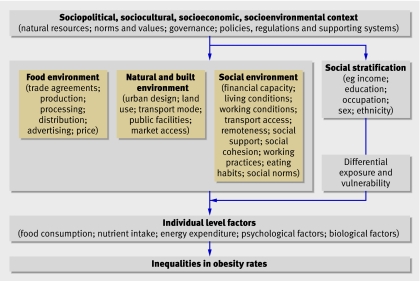

The conditions within which people trade, live, and work affect health,6 partly through their influence on behaviour and weight. The epidemiological pattern of obesity implies that the structures in society affect the unequal distribution of weight (fig 2).

Fig 2 Conceptual framework of the social determinants of inequalities in obesity

Food systems and behaviour

The increased availability of dietary energy, globally, is due to many factors. Liberalised trade opened many more countries to the international market.7 Food subsidies have arguably distorted the food supply in favour of less healthy foodstuffs such as those high in saturated fat,8 and transnational food companies have flooded the global market with cheap to produce, energy dense, nutrient empty foods.7 Supermarkets and food service chains have displaced small, family run stores or stalls, encouraging bulk purchases, convenience foods, and supersized portions.9 Energy density and fat intake have increased in both high income and “transitioning” countries.10 Although global food prices have dropped, on average,8 in rich countries the foods recommended in healthy eating guidelines are often more expensive than the less healthy options.11 Targeting community and personal norms and preferences, food advertising through television, which is omnipresent in rich countries and ever increasing in developing economies, aims to persuade individuals—particularly children—that they desire foods high in saturated fats, sugars, and salt.3

Built environment and behaviour

Research, mainly in high income countries, indicates that local urban planning and design can influence weight in several ways. The density of residences and the mix of land uses, together with connected streets and the ability to walk from place to place, are directly related to increased physical activity.12 Provision of and access to local public facilities and spaces for recreation and play are directly correlated with individuals’ levels of physical activity.13 The increasing reliance on cars is an important influence on shifts towards physical inactivity in both developed and developing countries.14 Low income groups are thought to be affected more by their built environments because their activity spaces are smaller, they are more constrained by lack of transportation, and opportunities to buy healthy food are lacking in lower income neighbourhoods.15

Social conditions and behaviour

Working and living conditions, such as having enough money for a healthy standard of living, underpin compliance with national health guidelines.16 Employment conditions can affect weight, although the evidence remains sparse. Current precarious employment conditions are related to sedentary work, disinclination to use active transport, and ready access to energy dense foods.17 18 More fundamentally, these labour market conditions mean increasingly less job control, security, flexibility of working hours, and access to paid family leave19—thereby undermining the material and psychosocial resources necessary for empowering individuals and communities to make healthy living choices.

Unequal society, unhealthy weight

A person or group’s place in the social hierarchy influences behavioural choices, which are governed by the material and psychosocial resources provided by the complex system consisting of the food, built, and social environments.20 Unequal exposure to health protecting or health damaging aspects of these environments adds health disadvantage to disadvantages of wealth, power, and prestige. These underlying structural inequities are likely to be responsible for the unequal distribution of obesity.

Addressing the global epidemic: the approach so far

Traditionally, interventions to prevent obesity took a direct approach, focusing on behaviour change through developing personal skills and enhancing the local environment.21 They were relatively effective in the short term, but most of these interventions focused on individuals have limited evidence for sustainability and transferability to other settings.22 Their uptake is generally greater in higher social status groups, arguably helping perpetuate the social gradient in obesity.23

More recently, wider policy action on the social determinants of the obesity epidemic has been called for. WHO’s global strategy on diet, physical activity, and health focuses on developing national food and agricultural policies that are consistent with promoting public health and multisectoral policies that promote physical activity, and providing information.24 In the recent European charter on obesity, ministers have committed to balancing responsibility between individuals and society.25 The recent UK Foresight Report makes clear the complexity of drivers that produce obesity; it highlights that most are societal issues and therefore require societal responses.26

A new policy agenda: obesity prevention through an equity lens

Despite these efforts the global obesity epidemic continues and its social gradient persists. Missing in most obesity prevention strategies is the recognition that obesity—and its unequal distribution—is the consequence of a complex system that is shaped by how society organises its affairs. Action must tackle the inequities in this system, aiming to ensure an equitable distribution of ample and nutritious global and national food supplies; built environments that lend themselves to easy access and uptake of healthier options by all; and living and working conditions that produce more equal material and psychosocial resources between and within social groups. This will require action at global, national, and local levels.

Global response

At the global level, international trade agreements offer opportunity for many people to benefit. However the nature of these agreements and the effect on health inequities between and within countries provoke concern. The experience of the Codex Alimentarius Commission (www.codexalimentarius.net) highlights the challenges. Codex is designed to help governments protect the health of consumers and ensure fair trade practices in the food trade. However, currently industry representatives hugely outnumber representatives from public interest groups, resulting in an imbalance between the goals of trade and consumer protection. This imbalance must be redressed.

Another concern is that international agreements restrict the policy space of national governments. This can be good for health, as in the case of the Framework Convention for Tobacco Control, where the global treaty is designed to narrow the policy space of governments, guiding them in a direction that is positive for health. However, WHO and other international agencies need to ensure that they have sufficient capacity and expertise, including legal expertise, to ensure that countries can implement international policy prescriptions, as well as provide technical guidance and support with respect to ensuring health concerns are represented at the international level. Building on the WHO global strategy of diet, physical activity and health, further collaboration with other UN agencies is needed to create a more extensive evidence base for understanding issues related to governance and healthy behaviours.

Ensuring that global food marketing does not target vulnerable societies requires binding international codes of practice related to production and marketing of healthy food, supported at the national level by policy and regulation. Regulating television advertising of foods high in fat or sugar to children is a highly cost effective upstream intervention.27 However, reliance on voluntary guidelines may result in differential uptake by better-off individuals or institutions and provides little opportunity for public and private sector accountability. Such global or national regulations must be developed by a consortium of public-private institutions and adhere to criteria for good governance.28

National responses

It is possible to intervene at the national level in the structural determinants of healthy food, including matters such as domestic subsidies for healthy food production. For example, Norway successfully reversed the population shift towards high fat, energy dense diets by using a combination of food subsidies, price manipulation, retail regulations, clear nutrition labelling, and public education focused on individuals.29 Few developing countries have interventions that have been evaluated, but Mauritius provides an example of a relatively successful programme that includes price policy, agricultural policy, and widespread educational activity in various settings.30 Both the Norwegian and Mauritian programmes produced positive dietary changes in the population at large, but relatively little is documented about the effect on health equity.

Much can be achieved through good governance at the national level, particularly when basic public goods such as transport infrastructure, clean water, and electricity remain elusive.31 At the heart of good governance lies the challenge of ensuring coherence between different ministries and levels within governments and between different agencies to enable the necessary intersectoral action. One of the few evaluated examples of such an approach is Healthy Food for All (www.healthyfoodforall.com), an all Ireland multi-agency, equity oriented initiative seeking to promote access, availability, and affordability of healthy food for low income groups.

Examples of structural and community intervention in the social determinants of obesity

Norway

Between 1975 and 1995 Norway successfully reversed the population shift towards high fat, energy dense diets. Consumption of saturated fat fell by 18% and blood cholesterol by 10%, and mortality from coronary heart disease was halved among middle aged men.29 Food subsidies, price manipulation, retail regulations, clear nutrition labelling, and education focused on individuals were used:

Setting consumer and producer price and income subsidies jointly in nutritionally justifiable ways

Adjusting absolute and relative consumer food price subsidies

Encouraging low prices for food grain, skimmed and low fat milk, vegetables, and potatoes and higher prices for sugar, butter, and margarine

Developing regulations to promote provision of healthy foods by retail stores, street vendors and institutions

Regulating food processing and labelling

Public and professional education and information

Mauritius

In Mauritius a comprehensive programme achieved declines in cholesterol, hypertension, smoking, and heavy alcohol use.30 This demonstration project of WHO’s “Interhealth” initiative used mass media; price policy; agricultural policy; widespread educational activity in the community, workplace, and schools; and other legislative and fiscal measures as key planks in the prevention strategy.

Prevalence of hypertension fell from 15% in men to 12%, and from 12% in women to 11%

Cigarette smoking fell from 58% in men to 47%, and from 7% in women to 4%

Heavy alcohol consumption fell from 38% in men to 14%, and from 3% in women to 1%

Mean population serum cholesterol fell from 5.5 mmol/l to 4.7 mmol/l

Ireland

Healthy Food for All (www.healthyfoodforall.com) is a multi-agency initiative seeking to promote access, availability, and affordability of healthy food for low-income groups in the Republic of Ireland and Northern Ireland. It is an intersectoral partnership that sets out to demonstrate and tackle the relation between food poverty and other policy concerns such as health inequalities, welfare adequacy, educational disadvantage, food production and distribution, retail planning and food safety. To achieve its central aim of ensuring that healthy food for all is a priority issue on the political agenda and that policies are coordinated across all departments it is engaging with government departments and making relevant policy submissions. Community food initiatives have been set up, working with NGOs and public private partnerships (such as the fruit and vegetables producers in Ireland).

Local responses

National and regional action is needed immediately to increase the opportunity for exercise within the environment and reduce the time spend in cars. The Brazilian population-wide Agita Sao Paulo physical activity programme successfully reduced the level of physical inactivity in the general population by using a multi-strategy approach of building pathways; widening paths and removing obstacles; building walking or running tracks with shadow and hydration points; maintaining green areas and leisure spaces; having bicycle storage close to public transport stations and at entrances of schools and workplaces; and implementing private and public incentive policies for mass active transport.32

Local, community based initiatives can promote equitable access to healthy food. The city of Sam Chuk in Thailand restored its major food and small goods market with the help of local intersectoral action including architects. The London Development Agency plans to establish a sustainable food distribution hub to supply independent food retailers and restaurants.9 The lack of systematic evaluation of initiatives, particularly with an equity focus, makes it difficult to generalise policy solutions in this field. In general, urban design and planning would be greatly aided by routine assessment of the impact on health equity of where food retail outlets are placed and how easy it is to get to them. Schools are another setting where inequities are reinforced. Schools can make money through placing soft drink vending machines on school property and by subcontracting lunch programmes, which encourage the sale of high profit, low quality foods, including fast food. If schools offer physical education, large class size and lack of equipment present barriers to participation.33 Effective interventions in schools are those that make healthy options available while also restricting the availability of competitive foods and options for inactivity.34

Conclusion

Many drivers of the obesity epidemic are shaped at the international level, but how the food system interacts with the built and social environment to affect obesity often depends on context—hence we see differing directions in the obesity gradient in low and high income countries. This must be considered in policy development and implementation, from global to local level.

The interconnected nature of the determinants of obesity implies the need for an integrated response comprising community level action and political will and investment. This requires joined-up action at global, national, and local levels, bringing together the capacity of multiple sectors. The key to that dynamic relationship is stewardship by the health sector.

Contributors and sources: SF planned the paper. SF and MC wrote the first draft of the paper and all authors contributed to the final version of the paper. SF is guarantor.

Funding: None.

Competing interests: SF is an employee of the Commission on Social Determinants of Health. MC is co-chair of the globalisation knowledge network of the Commission on Social Determinants of Health. DS is a commissioner of the Commission on Social Determinants of Health.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Friel S, Broom D. Unequal society, unhealthy weight: the social distribution of obesity. In: Dixon J, Broom D, eds. The 7 deadly sins of obesity Sydney: University of New South Wales Press, 2007:148-72.

- 2.Monteiro C, Conde W, Lu B, Popkin BM. Obesity and inequities in health in the developing world. Int J Obesity 2004:1-6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Popkin BM. Global nutrition dynamics: the world is shifting rapidly toward a diet linked with noncommunicable diseases. Am J Clin Nutr 2006;84:289-98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Office of the Surgeon General. The surgeon general’s call to action to prevent and decrease overweight and obesity. Rockville: US Dept of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, Office of the Surgeon General, 2001 [PubMed]

- 5.Yach D, McKee M, Lopez AD, Novotny T. Improving diet and physical activity: 12 lessons from controlling tobacco smoking. BMJ 2005;330:898-900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Marmot M, Wilkinson R. Social determinants of health 2nd ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005

- 7.Hawkes C. Uneven dietary development: linking the policies and processes of globalization with the nutrition transition, obesity and diet-related chronic diseases 2006www.globalizationandhealth.com/content/2/1/4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8.Elinder LS. Obesity, hunger, and agriculture: the damaging role of subsidies. BMJ 2005;331:1333-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dixon J, Omwega AM, Friel S, Burns C, Donati K, Carlisle R, et al. The health equity dimensions of urban food systems. J Urban Health 2007;84(suppl 1):S86-97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Prentice AM, Jebb SA. Fast foods, energy density and obesity: a possible mechanistic link. Obesity Rev 2003;4:187-94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Drewnowski A, Specter S. Poverty and obesity: the role of energy density and energy costs. Am J Clin Nutr 2004;79:6-16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Duncan MJ, Spence JC, Mummery WK. Perceived environment and physical activity: a meta-analysis of selected environmental characteristics. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Activity 2005;2:11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gordon-Larsen P, Nelson MC, Page P, Popkin BM. Inequality in the built environment underlies key health disparities in physical activity and obesity. Pediatrics 2006;117:417-24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Popkin BM. Technology, transport, globalization and the nutrition transition food policy. Food Policy 2006;31:554-69. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Papas MA, Alberg AJ, Ewing R, Helzlsouer KJ, Gary TL, Klassen AC. The built environment and obesity. Epidemiol Rev 2007;29:129-43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Friel S, Walsh O, McCarthy D. The irony of a rich country: issues of access and availability of healthy food in the Republic of Ireland. J Epidemiol Community Health 2006;60:1013-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Broom D, Strazdins L. The harried environment: is time pressure making us fat? In: Dixon J, Broom D, eds. The 7 deadly sins of obesity Sydney: University of New South Wales Press, 2007:35-45.

- 18.Roos E, Sarlio-Lahteenkorva S, T L, Lahelma E. Associations of work-family conflicts with food habits and physical activity. Public Health Nutrition 2007;10:222-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Benach J, Muntaner C. Precarious employment and health: developing a research agenda. J Epidemiol Community Health 2007;61:276-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Caplan P, Keane A, Willetts A, Williams J. Studying food choice in its social and cultural contexts: approaches from a social anthropological perspective. In: Murcott A, ed. The nation’s diet: the social science of food choice Harlow: Addison Wesley Longman, 1998

- 21.Flynn MAT, McNeil DA, Maloff B, Mutasingwa D, Wu M, Ford C, et al. Reducing obesity and related chronic disease risk in children and youth: a synthesis of evidence with “best practice” recommendations. Obesity Reviews 2006;7(suppl):S7-66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mulvihill C, Quigley R. The management of obesity and overweight, an analysis of reviews of diet, physical activity and behavioural approaches London: Health Development Agency, 2003

- 23.Lahelma E. Health inequalities—the need for explanation and intervention. Eur J Public Health 2006;16:339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.World Health Organization. Global strategy on diet, physical activity and health Geneva: WHO, 2004

- 25.World Health Organization. European Charter on counteracting obesity Copenhagen: WHO Regional Office for Europe, 2006

- 26.Haby MM, Vos T, Carter R, Moodie M, Markwick A, Magnus A, et al. A new approach to assessing the health benefit from obesity interventions in children and adolescents: the assessing cost-effectiveness in obesity project. Int J Obes 2006;30:1463-75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Government Office For Science. Tackling obesities: future choices—project report London: Foresight Programme Government Office for Science, 2007

- 28.Lee K, Koivusalo M, Ollila E, Labonte R, Schrecker T, Schuftan C, et al. Globalization, global governance and the social determinants of health: a review of the linkages and agenda for action WHO Commission on the Social Determinants of Health Globalisation Knowledge Network, 2007

- 29.Norum KR. Some aspects of Norwegian nutrition and food policy In: Shetty P, McPherson K, eds. Diet, nutrition and chronic disease: lessons from contrasting worlds London: Wiley, 1997

- 30.Dowse GK, Gareeboo H, Alberti KG, Zimmet P, Tuomilehto J, Purran A, et al. Changes in population cholesterol concentrations and other cardiovascular risk factor levels after five years of the non-communicable disease intervention programme in Mauritius. BMJ 1995;311:1255-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Paarlberg R. Governance and food security in an age of globalization Washington: International Food Policy Research Institute, 2002

- 32.Matsudo SM, Matsudo VR, Araujo TL, Andrade DR, Andrade EL, De Oliveira LC, et al. The Agita São Paulo Program as a model for using physical activity to promote health. Rev Panam de Salud Pública 2006;14:265-72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ebbeling CB, Pawlak DB, Ludwig DS. Childhood obesity: public-health crisis, common sense cure. Lancet 2002;360:473-82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Brownson RC, Haire-Joshu D, Luke DA. Shaping the context of health: a review of environmental and policy approaches in the prevention of chronic diseases. Annu Rev Public Health 2006;27:341-70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]