Abstract

Objective To compare the functional results after displaced fractures of the femoral neck treated with internal fixation or hemiarthroplasty.

Design Randomised trial with blinding of assessments of functional results.

Setting University hospital.

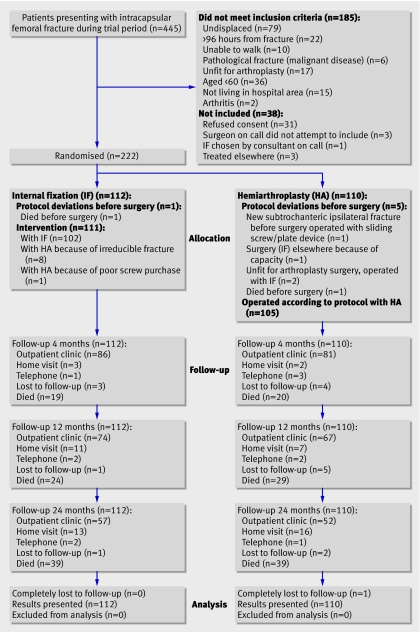

Participants 222 patients; 165 (74%) women, mean age 83 years. Inclusion criteria were age above 60, ability to walk before the fracture, and no major hip pathology, regardless of cognitive function.

Interventions Closed reduction and two parallel screws (112 patients) and bipolar cemented hemiarthroplasty (110 patients). Follow-up at 4, 12, and 24 months.

Main outcome measures Hip function (Harris hip score), health related quality of life (Eq-5d), activities of daily living (Barthel index). In all cases high scores indicate better function.

Results Mean Harris hip score in the hemiarthroplasty group was 8.2 points higher (95% confidence interval 2.8 to 13.5 points, P=0.003) at four months and 6.7 points (1.5 to 11.9 points, P=0.01) higher at 12 months. Mean Eq-5d index score at 24 months was 0.13 higher in the hemiarthroplasty group (0.01 to 0.25, P=0.03). The Eq-5d visual analogue scale was 8.7 points higher in the hemiarthroplasty group after 4 months (1.9 to 15.6, P=0.01). After 12 and 24 months the percentage scoring 95 or 100 on the Barthel index was higher in the hemiarthroplasty group (relative risk 0.67, 0.47 to 0.95, P=0.02. and 0.63, 0.42 to 0.94, P=0.02, respectively). Complications occurred in 56 (50%) patients in the internal fixation group and 16 (15%) in the hemiarthroplasty group (3.44, 2.11 to 5.60, P<0.001). In each group 39 patients (35%) died within 24 months (0.98, 0.69 to 1.40, P=0.92)

Conclusions Hemiarthroplasty is associated with better functional outcome than internal fixation in treatment of displaced fractures of the femoral neck in elderly patients.

Trial registration NCT00464230.

Introduction

An estimated 1.6 million people sustain a hip fracture every year. Each year hip fractures are responsible for the loss of at least 2.35 million disability adjusted life years and more than 5 million people in the world experience disability from a hip fracture.1 2 A hip fracture is a life changing event for any patient, and the risk of disability, increased dependence, and death is substantial.3 4 About half of the hip fractures are intracapsular femoral neck fractures,5 and, while internal fixation is considered a reliable method for extracapsular fractures (that is, trochanteric and subtrochanteric fractures), the surgical treatment for displaced intracapsular femoral neck fractures has been controversial for at least 50 years.6 7 More surgical complications and reoperations occur after internal fixation than after arthroplasty, but there is no consensus as to which treatment gives the best functional results. Three meta-analyses including mainly the same randomised controlled studies of the treatment of displaced femoral neck fractures found reoperation rates after arthroplasty of 7%,8 11%,9 and 11%10 compared with 40%, 35%, and 33% for internal fixation. Two of the meta-analyses contained analyses of postoperative pain, function, and quality of life, without showing any difference between the treatment groups.9 10

We examined treatment with two parallel screws compared with a bipolar cemented hemiarthroplasty with regard to functional outcome and quality of life in the treatment of displaced intracapsular fractures of the femoral neck.

Methods

Patients

Patients aged 60 years or older who presented with an intracapsular femoral neck fracture with angular displacement in either radiographic plane and who were previously ambulant were eligible for inclusion. Exclusion criteria were being unfit for arthroplasty according to anaesthesiologist, previous symptomatic hip pathology (such as arthritis), pathological fracture, delay of more than 96 hours from injury to treatment, or living outside the hospital’s designated area. All patients who were able to give an informed consent did so. Patients who could not give informed consent because of temporary or permanent cognitive impairment were included if it was considered to be in their best interest and after consultation with their family. The follow-up period was 24 months, with scheduled follow-up visits at 4, 12, and 24 months. The surgeon on call performed the randomisation. We randomly placed 115 pieces of paper with the word “hemi” and 115 with the word “screws” in opaque envelopes. The envelopes were sealed and mixed before they were numbered. The envelopes were kept in the emergency admissions area, and, after recruiting the patient, the surgeon opened the envelope with the lowest number. Recruitment was from September 2002 to March 2004.

Intervention

Patients underwent a Charnley-Hastings bipolar cemented hemiarthroplasty (DePuy/Johnson and Johnson, United Kingdom) or closed reduction and internal fixation with two parallel cannulated screws (Olmed, DePuy/Johnson and Johnson, Sweden).11 Arthroplasty was performed through a direct lateral approach12 with the patient in a lateral decubitus position with a third generation cementing technique.13 The surgeons on call carried out all the operations, with no specific changes in departmental routines for the study. Spinal anaesthesia was used for both procedures. The hemiarthroplasty patients were given preoperative intravenous cefalotin 2 g and a further three doses the first 24 hours after the operation. Patients in both groups were given 5000 IU low molecular weight heparin subcutaneously daily until they could move relatively well. Early mobilisation was encouraged, with weight bearing as tolerated. The patients in the hemiarthroplasty group were given instructions to avoid movements that could increase the risk of joint dislocation. Both interventions were standard operations in the department before the study.

Objectives and outcomes

Hip function was rated with Harris hip score.14,15,16 The score has a maximum of 100 points (no disability), covering pain (0-44 points), function (0-47 points), and range of motion and absence of deformity (0-9 points). Our primary outcome was the score after 12 months. Health related quality of life was rated by Eq-5d (Euroqol).17 This is a generic instrument in which the respondents are asked to rate their current state of health on five dimensions (mobility, personal hygiene, usual activities, pain/discomfort, and anxiety/depression) with three possible responses for each item (no problem, some problem, unable/large problem). We used the Eq-5d index scores generated from a time trade-off study in the UK.18 We also used the Eq-5d visual analogue scale, ranging from 0 (worst possible health) to 100 (best possible health). The Barthel index was used to rate ability to perform activities of daily living.19 20 This is a 10 item scale with a highest possible score of 5 to 15 points on each item. This gives a total score from 0 (full dependence) to 100 (independence). Complications and reoperations were noted.

The surgeon recruiting the patient noted the Harris hip score before the fracture. At the follow-up points a physiotherapist noted the Harris hip score and a research assistant registered the Eq-5d, Barthel index, and a 12 item abbreviated mini-mental state examination21; both were blinded to the intervention. When necessary we used information from nursing home staff and family members for the Harris hip score and the Barthel index.

Statistical methods

We assumed that a difference in the Harris hip score of 5-10 points was clinically relevant and calculated the sample size from 7.5 points with an expected standard deviation (SD) of 15. To obtain a statistical power of 90% with P<0.05 we needed 170 patients. To allow for some mortality and loss to follow-up we decided to recruit 220 patients. We used Pearson’s χ2 for dichotomous variables and t tests for Harris hip score, Eq-5d index score, and analyses of continuous variables. All analyses were based on intention to treat—that is, all participants were analysed according to their allocation at randomisation. SPSS version 14 (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL) was used for statistical analyses.

Results

Follow-up

Of the 445 patients presenting with fracture, 260 were eligible for inclusion and we recruited 222 (figure). One patient (hemiarthroplasty group) was completely lost to follow-up, and one patient (internal fixation group) was followed up by telephone only. Patients who were unable or unwilling to come to the outpatient clinic were visited in their home or interviewed by phone. Phone interviews were supplemented with information from health personnel or family members, or both. Eq-5d and mini-mental state interviews were not performed by phone. One patient was included with both hips, 34 days apart, with one hip in either group. We excluded her results from the analysis of the functional assessment scales.

Recruitment and flow of patients with intracapsular femoral neck fractures during study

Demographics and perioperative results

At baseline the groups were similar (table 1). Twenty eight surgeons performed a median of five operations each (range 1-26). Twenty patients (18%) in the internal fixation group experienced intraoperative problems; nine were changed to hemiarthroplasty because of irreducible fractures (eight) or poor screw purchase (one). In the hemiarthroplasty group there were 15 (14%) reports of intraoperative problems. Duration of surgery, amount of blood loss, and need for blood transfusion were higher in the hemiarthroplasty group (table 2). There was no association between time from admission to surgery or surgeon’s experience and complications.

Table 1.

Baseline and demographic characteristics of included patients with hip fracture according to allocated treatment. Figures are numbers (percentages) unless stated otherwise

| Internal fixation (n=112) | Hemiarthroplasty (n=110) | |

|---|---|---|

| Not able to give informed consent | 24 (21) | 27 (25) |

| Mean (SD) age at fracture (years) | 83.2 (7.65) | 82.5 (7.32) |

| Women | 87 (78) | 78 (71) |

| ASA* group I or II | 59 (53) | 52 (47) |

| Living in own home | 80 (71) | 83 (76) |

| Mean (SD) retrospective Harris hip score (total) (n=109 and 100†) | 84.3 (14.72) | 83.6 (13. 59) |

| Previously recognised cognitive failure | 40 (36) | 29 (26) |

| Concurrent symptomatic medical disease | 52 (46) | 64 (58) |

| Concurrent condition or impairment likely to affect rehabilitation | 74 (66) | 73 (66) |

| Ability to walk without any aid | 67 (60) | 60/107† (56) |

| Fall from standing height or lower | 109 (97) | 109 (99) |

| Injured left hip | 63 (56) | 59 (54) |

| Mean (SD) time from injury to admission (hours) (n=94 and 83†) | 8.0 (14.3) | 5.5 (15.2) |

| Where did injury occur: | ||

| Own home | 55 (49) | 49 (45) |

| Nursing home | 26 (23) | 18 (16) |

| Outside | 24 (21) | 21 (19) |

| Indoors except own home | 6 (5) | 16 (15) |

| Hospital | 1 (1) | 6 (6) |

*American Society of Anesthesiologists.

†Data missing for some patients.

Table 2.

Characteristics during and after surgery for patients with hip fracture according to type of treatment. Figures are numbers* (percentages) of patients unless stated otherwise

| Internal fixation | Hemiarthroplasty | Mean difference or relative risk (95% CI) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Perioperative details | ||||

| Mean (SD) time from admission to surgery (hours) | 25.3 (15.34) (n=111) | 31.4 (22.32) (n=107) | 6.10† (0.96 to 11.23) | 0.02 |

| Mean (SD) time in operation theatre (minutes) | 107 (44.90) (n=109) | 167 (34.06) (n=102) | 60.4† (49.5 to 71.3) | <0.001 |

| Mean (SD) time of surgery (minutes) | 26 (20.18) (n=110) | 76 (19.01) (n=107) | 49.3† (44.1 to 54.6) | <0.001 |

| Mean (SD) intraoperative blood loss (ml) | 35 (86.67) (n=110) | 348 (203.64) (n=107) | 313.1† (271.4 to 354.8) | <0.001 |

| Main surgeons >3 years experience with procedure | 77 (69) (n=111) | 67 (62) (n=109) | 1.13 (0.93 to 1.37) | 0.22 |

| Spinal anaesthesia | 106 (96) (n=111) | 103 (95) (n=108) | 1.00 (0.95 to 1.06) | 0.97 |

| Hospital stay | ||||

| Received blood transfusion while admitted | 15 (14) (n=111) | 35 (32) (n=109) | 0.42 (0.24 to 0.73) | 0.001 |

| Any medical complication | 28 (25) (n=111) | 30 (28) (n=109) | 0.92 (0.59 to 1.43) | 0.70 |

| Postoperative confusion | 17 (15) (n=111) | 20 (18) (n=109) | 0.84 (0.46 to 1.51) | 0.55 |

| Mean (SD) hospital stay (days) | 8.2 (7.35) (n=111) | 10.2 (11.95) (n=109) | 1.98 (−0.66 to 4.61) | 0.14 |

| Cognitive function | ||||

| Cognitive failure at 4 months (MMSE-12 score <10) | 44 (49) (n=89) | 42 (50) (n=84) | 0.99 (0.73 to 1.33) | 0.94 |

| Mortality | ||||

| Within 30 days | 7 (6) (n=112) | 10 (9) (n=110) | 0.68 (0.27 to 1.73) | 0.42 |

| Within 90 days | 16 (14) (n=112) | 20 (18) (n=110) | 0.77 (0.43 to 1.44) | 0.43 |

| Within 12 months | 24 (21) (n=112) | 29 (26) (n=110) | 0.81 (0.51 to 1.30) | 0.39 |

| Within 2 years | 39 (35) (n=112) | 39 (35) (n=110) | 0.98 (0.69 to 1.40) | 0.92 |

*Number varies because some information was missing for some patients.

†Mean difference.

Functional outcomes

The functional results for all three scales—Harris hip score, Eq-5d, and Barthel index—favoured the hemiarthroplasty group, although this was not significant at all time points for all scales (table 3). In the hemiarthroplasty group the Harris hip score was significantly higher at 4 and 12 months; the Eq-5d index score was higher at 24 months; and the visual analogue scale score was significantly higher at 4 months. The number of responses on Eq-5d, especially on the visual analogue scale, was lower than for the other scales, mainly because patients with mini-mental state examination scores of 8 or lower often did not respond. The proportion scoring 95 or 100 points on the Barthel index was higher in the hemiarthroplasty group at both 12 and 24 months.

Table 3.

Functional outcomes in patients* after hip fracture according to allocated treatment

| Internal fixation | Hemiarthroplasty | Mean difference or relative risk (95% CI) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) Harris hip score | ||||

| At 4 months | 59.6 (19.5) (n=89) | 67.7 (15.8) (n=84) | 8.2 (2.8 to 13.5) | 0.003 |

| At 12 months | 65.8 (15.9) (n=87) | 72.6 (17.5) (n=74) | 6.7 (1.5 to 11.9) | 0.01 |

| At 24 months | 67.3 (15.5) (n=71) | 70.6 (19.1) (n=68) | 3.3 (−2.5 to 9.2) | 0.26 |

| Mean (SD) Eq-5d index score and visual analogue scale | ||||

| Index score: | ||||

| At 4 months | 0.53 (0.29) (n=79) | 0.61 (0.30) (n=70) | 0.10 (−0.003 to 0.20) | 0.06 |

| At 12 months | 0.56 (0.33) (n=70) | 0.65 (0.30) (n=62) | 0.10 (−0.008 to 0.22) | 0.07 |

| At 24 months | 0.61 (0.31) (n=52) | 0.72 (0.23) (n=52) | 0.13 (0.01 to 0.25) | 0.03 |

| Visual analogue scale: | ||||

| At 4 months | 53 (18.5) (n=69) | 62 (21.0) (n=60) | 8.7 (1.9 to 15.6) | 0.01 |

| At 12 months | 57 (21.6) (n=59) | 63 (24.3) (n=54) | 6.2 (−2.4 to 14.7) | 0.16 |

| At 24 months | 60 (18.0) (n=45) | 60.0 (21.0) (n=43) | −0.8 (−9.1 to 7.5) | 0.84 |

| No (%) of patients with Barthel index score of 95 or 100 | ||||

| At 4 months | 41 (47) (n=88) | 40 (50) (n=80) | 0.93† (0.68 to 1.27) | 0.66 |

| At 12 months | 31 (36) (n=87) | 39 (53) (n=73) | 0.67† (0.47 to 0.95) | 0.02 |

| At 24 months | 24 (35) (n=69) | 36 (53) (n=68) | 0.63† (0.42 to 0.94) | 0.02 |

*Number varies because not all information could be obtained for all patients.

†Relative risk.

A subgroup analysis of the patients in the internal fixation group whose fracture healed without complications (n=53) compared with the patients randomised to hemiarthroplasty showed scores in favour of the hemiarthroplasty group at 12 and 24 months (table 4). The parallel subgroup comparison of patients from the internal fixation group who underwent reoperation with hemiarthroplasty (n=39) and the entire hemiarthroplasty group showed scores favouring hemiarthroplasty at 4 months (table 5).

Table 4.

Patient in internal fixation group who healed uneventfully (n=53) compared with those in hemiarthroplasty group

| Healed internal fixation | Hemiarthroplasty | Mean difference or relative risk (95% CI) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) Harris hip score | ||||

| At 4 months | 63.4 (14.8) (n=37) | 67.7 (15.8) (n=84) | 4.4 (−1.7 to 10.4) | 0.16 |

| At 12 months | 63.7 (16.7) (n=37) | 72.6 (17.5) (n=74) | 8.8 (1.9 to 15.7) | 0.01 |

| At 24 months | 63.9 (12.0) (n=29) | 70.6 (19.1) (n=68) | 6.7 (0.3 to 13.1) | 0.04 |

| Mean (SD) Eq-5d index score and visual analogue scale | ||||

| Index score: | ||||

| At 4 months | 0.58 (0.22) (n=29) | 0.61 (0.30) (n=70) | 0.03 (−0.10 to 0.15) | 0.67 |

| At 12 months | 0.57 (0.32) (n=27) | 0.65 (0.30) (n=62) | 0.08 (−0.06 to 0.22) | 0.26 |

| At 24 months | 0.48 (0.41) (n=17) | 0.72 (0.23) (n=52) | 0.24 (0.02 to 0.46) | 0.03 |

| Visual analogue scale: | ||||

| At 4 months | 56 (15.2) (n=26) | 62 (21.0) (n=60) | 5.6 (−3.5 to 14.7) | 0.22 |

| At 12 months | 51 (15.6) (n=22) | 63 (24.3) (n=54) | 12.1 (2.7 to 21.4) | 0.01 |

| At 24 months | 55 (11.2) (n=14) | 60 (21.0) (n=43) | 4.4 (−4.4 to 13.2) | 0.32 |

| No (%) with Barthel index score of 95 or 100 | ||||

| At 4 months | 16 (44) (n=36) | 40 (50) (n=80) | 0.89* (0.58 to1.36) | 0.58 |

| At 12 months | 10 (27) (n=37) | 39 (53) (n=73) | 0.51* (0.29 to 0.90) | 0.01 |

| At 24 months | 6 (21) (n=28) | 36 (53) (n=68) | 0.41* (0.19 to 0.85) | 0.01 |

*Relative risk.

Table 5.

Patients in internal fixation group who underwent further operation with hemiarthroplasty (n=39) compared with those in hemiarthroplasty group

| Reoperated internal fixation | Hemiarthroplasty | Mean difference or relative risk (95% CI) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) Harris hip score | ||||

| At 4 months | 53.6 (21.7) (n=37) | 67.7 (15.8) (n=84) | 14.1 (6.1 to 22.0) | <0.001 |

| At 12 months | 66.2 (14.3) (n=37) | 72.6 (17.5) (n=74) | 6.4 (−0.2 to 13.0) | 0.06 |

| At 24 months | 66.9 (15.9) (n=31) | 70.6 (19.1) (n=68) | 3.7 (−4.1 to 11.5) | 0.35 |

| Mean (SD) Eq-5d index score and visual analogue scale | ||||

| Index score: | ||||

| At 4 months | 0.40 (0.38) (n=37) | 0.61 (0.30) (n=70) | 0.21 (0.06 to 0.35) | 0.005 |

| At 12 months | 0.50 (0.40) (n=32) | 0.65 (0.30) (n=62) | 0.15 (−0.01 to 0.31) | 0.07 |

| At 24 months | 0.58 (0.34) (n=27) | 0.72 (0.23) (n=52) | 0.14 (−0.01 to 0.29) | 0.07 |

| Visual analogue scale: | ||||

| At 4 months | 49 (20.2) (n=33) | 62 (21.0) (n=60) | 12.9 (3.9 to 21.8) | 0.005 |

| At 12 months | 59 (23.8) (n=27) | 63 (24.3) (n=54) | 4.1 (−7.2 to 15.4) | 0.47 |

| At 24 months | 60 (19.3) (n=23) | 60 (19.3) (n=43) | −0.6 (−10.9 to 9.9) | 0.91 |

| No (%) with Barthel index score of 95 or 100 | ||||

| At 4 months | 16 (43) (n=37) | 40 (50) (n=80) | 0.87* (0.56 to 1.33) | 0.50 |

| At 12 months | 15 (41) (n=37) | 39 (53) (n=73) | 0.76* (0.49 to 1.18) | 0.20 |

| At 24 months | 11 (37) (n=30) | 36 (53) (n=68) | 0.69* (0.41 to 1.17) | 0.14 |

*Relative risk.

Complications and reoperations

The risks of complications and reoperations were 3.4 to 4.2 times higher in the internal fixation group (tables 6 and 7). Median time to complication was 137.5 days in the internal fixation group (range 8-730) and 18 days (range 6-730) in the hemiarthroplasty group (P=0.01). Sixteen patients had to have more than one further operation (two to six); 14 of them were in the internal fixation group (relative risk 6.88, 95% confidence interval 1.60 to 29.55, P=0.002).

Table 6.

Complications up to 24 months in patients with hip fracture according to type of treatment. All complications are counted so more than one may apply for each hip. Figures are numbers (percentages) of patients unless stated otherwise*

| Internal fixation (n=111) | Hemiarthroplasty (n=108) | |

|---|---|---|

| Wound dehiscence >1 week | 0 (0) | 2 (2) |

| Painful protruding screws | 3 (3) | 0 (0) |

| Painful heterotopic ossification | 1 (1) | 1 (1) |

| Deep venous thrombosis | 1 (1) | 0 (0) |

| Pulmonary embolism | 2 (2) | 0 (0) |

| Pressure sore | 3 (3) | 1 (1) |

| Ipsilateral above knee amputation | 1 (1) | 0 (0) |

| Radiographic loosening of hemiarthroplasty† | 0 (0) | 1 (1) |

| Dislocation of hemiarthroplasty† | 6 (5) | 1 (1) |

| Deep infection†‡ | 7 (6) | 7 (7) |

| Mechanical failure of internal fixation/non-union†§ | 40 (36) | 3 (3) |

| Avascular necrosis† | 6 (5) | 0 (0) |

| Total No of complications¶ | 70 | 16 |

| No of hips with any complication** | 56 (50) | 16 (15) |

| No of hips with major complication related to method†† | 47 (42) | 11 (10) |

*Excludes two patients who died preoperatively, one in each group, and one patient in hemiarthroplasty group lost to follow-up.

†Registered as major complication related to method when there was attributable pain or reduced function.

‡ Six of the seven deep infections in patients in internal fixation group were in those who had hemiarthroplasty, either as primary procedure because of intraoperative problems (n=3) or after failure of internal fixation (n=3).

§Three patients in hemiarthroplasty group with mechanical failure primarily underwent internal fixation (fig 1).

¶P<0.001

**Relative risk (95% CI) 3.44 (2.11 to 5.60), P<0.001.

††Relative risk (95% CO) 4.16 (2.28 to 7.58), P<0.001.

Table 7.

Reoperation up to 24 months in patients with hip fracture according to type of treatment. Figures are numbers (percentages) of patients unless stated otherwise*

| Internal fixation (n=111) | Hemiarthroplasty (n=108) | |

|---|---|---|

| Adjustment of screw position | 1 (1) | 0 (0) |

| Screw removal | 8 (7) | 1 (1) |

| Hemiarthroplasty as tertiaryprocedure after screw removal† | 4 (4) | 1 (1) |

| Screw removal and hemiarthroplasty† | 35 (32) | 1 (1) |

| Revision from hemiarthroplasty to total hip arthroplasty†‡ | 4 (4) | 0 (0) |

| Soft tissue debridement of hemiarthroplasty† | 7 (6) | 6 (6) |

| Open reduction of dislocated hemiarthroplasty† | 2 (2) | 0 (0) |

| Closed reduction of dislocated hemiarthroplasty† | 5 (5) | 1 (1) |

| Excision arthroplasty† | 4 (4) | 3 (3) |

| Total No of reoperations§ | 70 | 13 |

| No of hips with any reoperation¶ | 47 (42) | 11 (10) |

| No of hips with major reoperation** †† | 44 (40) | 11 (10) |

*Excludes two patients who died preoperatively, one in each group, and one patient in hemiarthroplasty group lost to follow-up.

†Registered as major reoperation.

‡In one case stem was exchanged and revised to conventional total hip arthroplasty. In the other three hips stem retained and semiconstrained acetabular component inserted.

§P<0.001.

¶Relative risk (95% CI) 4.20 (2.30 to 7.65), P<0.001

**Two patients with failure of internal fixation did not have further operation because of poor medical condition. Three patients with avascular necrosis were diagnosed at 24 month follow-up and thus did not have further operation within follow-up time of 24 months. One had no pain and no reoperation was planned.

††Relative risk (95% CI) 3.89 (2.13 to 7.13), P<0.001.

Discussion

In patient with displaced intracapsular femoral neck fractures, hemiarthroplasty results in better hip function, higher health related quality of life, and more independence than internal fixation. The primary outcome measure, the Harris hip score at 12 months, was a mean of 6.7 (95% confidence interval 1.5 to 11.9) points higher in the hemiarthroplasty group.

Strengths and weaknesses

Some care should be taken, in interpreting the secondary outcomes. Firstly, we made multiple comparisons, and this increases the risk of false positive results. Secondly, in some cases where we found significant differences, the confidence intervals are wide and nearly include zero. The trend in favour of hemiarthroplasty as treatment for displaced femoral neck fractures, however, is clear in all the outcome measures, and the Eq-5d visual analogue scale at 24 months was the only score with a non-significant difference in favour of the internal fixation group.

Both interventions were familiar to the surgeons before the study, and both methods are modern and well defined. We achieved a high follow-up rate, and evaluation was performed blinded with recognised assessment scales. The Harris hip score is a widely used functional score and has been validated for patients with osteoarthritis.15 16 22,23,24 The Eq-5d and Barthel index have been recommended for patients with hip fracture and have also been found useful in those with cognitive failure, with a possible exception of the visual analogue scale of Eq-5d.20 25,26,27,28,29,30 We chose a cut-off point of 90/95 on the Barthel index because it has a good predictive value of the ability to live independently.31 32 It may be perceived as a weakness in our study that a large number of surgeons with varying experience participated. Our rates of complications and reoperations are high but comparable with those seen in previous studies.8,9,10 30 33,34 Two studies in which only one or two expert surgeons performed the operations showed fewer healing complications after internal fixation but still had rates of revision to arthroplasty of 34%29 and 36%.33

Surprising lack of differences

Other studies have not had as unequivocal results. The lack of differences found previously between these two quite different treatments may seem surprising. Some studies may have used types of hemiarthroplasty that work less well in more active patients.8 24 33 35 Several studies show better results for arthroplasty at the early follow-ups but with less or no difference at later time points.23 29 30 34 36 This might be because rehabilitation after arthroplasty is faster, but eventually internal fixation patients get to the same level of function. Time to recovery is important enough in itself for these patients, but another explanation might be that the effect of femoral neck fracture is diluted by other diseases and conditions over time. A crossover-like effect, caused by the large number of revisions from internal fixation to arthroplasty combined with loss of statistical power because of mortality, might also weaken the treatment effects at later follow-ups.

Even though the outcome of our study seems convincing, in light of the results of the meta-analyses,9 10 it is still possible that hemiarthroplasty and internal fixation produce the same functional results. It seems at least highly unlikely, however, that the results are better after internal fixation.

Subgroup analyses

In our study even patients with internal fixations who healed uneventfully had poorer functional results at 12 and 24 months than patients in the hemiarthroplasty group. Patients with internal fixations who underwent further hemiarthroplasty had poorer functional results than those with primary hemiarthroplasties after four months, which is around the time most of the failures occurred, whereas at the later follow-up points we found only a non-significant tendency towards better results in the primary hemiarthroplasty group. Care must be taken in interpreting these results as they are the result of post hoc subgroup analyses and include multiple comparisons and some of them display wide confidence intervals. We have found no previous research comparing internal fixation without complications and hemiarthroplasty, but a previous retrospective study from our institution found more reoperations after secondary hemiarthroplasty.37 Also, in a prospective study Roberts and Parker reported more reoperations and more pain in the group undergoing secondary hemiarthroplasty.38 Neither the view that a failure after internal fixation has no consequence because revision to arthroplasty is uncomplicated nor the belief that there is an advantage to keep the native hip joint after a displaced femoral neck fracture can thus be supported.

Mortality

One argument left in favour of internal fixation may be mortality. A common clinical concern is that a hemiarthroplasty is too extensive an operation for these patients, especially in the acute setting. The available meta-analyses8,9,10 39 and our results show a non-significant tendency towards lower mortality in the internal fixation group, but only one previous randomised study found significantly higher mortality in the hemiarthroplasty group.22 A study powered to detect a difference in mortality would have to be large, probably requiring several thousand patients.8 9 If the tendency of an increased early mortality of 3-4% of patients after arthroplasty is a true incidence, however, it would be a finding of considerable importance.

It seems clear that most patients with displaced femoral neck fractures should be treated with arthroplasty, and further research should focus on what kind of arthroplasty to use. There is little evidence to suggest that one internal fixation device or one type of arthroplasty is superior to any other.40 41 In the absence of documentation in femoral neck fractures, arthroplasties that perform well in osteoarthritis should be used. We have shown that a bipolar hemiarthroplasty with a well documented cemented femoral stem gives superior results compared with fixation with two parallel screws.

What is already known on this topic

In patients with displaced femoral neck fractures 30-40% of those treated with internal fixation need a further operation, whereas hemiarthroplasty has a reoperation rate of 5-10%

Meta-analyses have failed to show a difference in functional results

What this study adds

Hemiarthroplasty gave better functional results, higher health related quality of life, and more independence than internal fixation

Better results were found for hemiarthroplasty even when compared with patients with internal fixation that healed without complications

Kenneth Nilsen, Wender Figved, Evind Kaare Osnes, Bjørn Robstad, Marte T Magnusson, Willimijn Vervaat, Åsa Axelsson, Vibeke Lambert-Grave, and Helene Søberg participated in the collection of data.

Contributors: The protocol was written by all the authors. FF analysed the data and drafted the manuscript, which was revised by LN and JEM. All authors approved the final version. FF is guarantor.

Funding: Norwegian Foundation for Health and Rehabilitation through the Norwegian Osteoporosis Society and the Norwegian Research Council, Nycomed, Smith and Nephew, and OrtoMedic.

Competing interests: FF has received lecture fees from OrtoMedic, who market orthopaedic implants; LN has received consulting and lecture fees from DePuy, Biomet, OrtoMedic, and SCP, who all manufacture and market orthopaedic implants.

Ethical approval: Regional ethics committee.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Johnell O, Kanis JA. An estimate of the worldwide prevalence and disability associated with osteoporotic fractures. Osteoporos Int 2006;17:1726-33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Johnell O, Kanis JA. An estimate of the worldwide prevalence, mortality and disability associated with hip fracture. Osteoporos Int 2004;15:897-902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Van Balen R, Steyerberg EW, Polder JJ, Ribbers TL, Habbema JD, Cools HJ. Hip fracture in elderly patients: outcomes for function, quality of life, and type of residence. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2001;390:232-43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Osnes EK, Lofthus CM, Meyer HE, Falch JA, Nordsletten L, Cappelen I, et al. Consequences of hip fracture on activities of daily life and residential needs. Osteoporos Int 2004;15:567-74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lofthus CM, Osnes EK, Falch JA, Kaastad TS, Kristiansen IS, Nordsletten L, et al. Epidemiology of hip fractures in Oslo, Norway. Bone 2001;29:413-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Parker M, Johansen A. Hip fracture. BMJ 2006;333:27-30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Garden RS. Low-angle fixation in fractures of the femoral neck. J Bone Joint Surg Br 1961;43:647-63. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rogmark C, Johnell O. Primary arthroplasty is better than internal fixation of displaced femoral neck fractures: a meta-analysis of 14 randomized studies with 2,289 patients. Acta Orthop 2006;77:359-67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bhandari M, Devereaux PJ, Swiontkowski MF, Tornetta P 3rd, Obremskey W, Koval KJ, et al. Internal fixation compared with arthroplasty for displaced fractures of the femoral neck. A meta-analysis. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2003;85-A(9):1673-81. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Masson M, Parker MJ, Fleischer S. Internal fixation versus arthroplasty for intracapsular proximal femoral fractures in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2003;(2):CD001708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Robinson CM, Saran D, Annan IH. Intracapsular hip fractures. Results of management adopting a treatment protocol. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1994;302:83-91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hardinge K. The direct lateral approach to the hip. J Bone Joint Surg Br 1982;64:17-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Oishi CS, Walker RH, Colwell CW Jr. The femoral component in total hip arthroplasty. Six to eight-year follow-up of one hundred consecutive patients after use of a third-generation cementing technique. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1994;76:1130-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Harris WH. Traumatic arthritis of the hip after dislocation and acetabular fractures: treatment by mold arthroplasty. An end-result study using a new method of result evaluation. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1969;51:737-55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hoeksma HL, van den Ende CH, Ronday HK, Heering A, Breedveld FC. Comparison of the responsiveness of the Harris hip score with generic measures for hip function in osteoarthritis of the hip. Ann Rheum Dis 2003;62:935-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Soderman P, Malchau H. Is the Harris hip score system useful to study the outcome of total hip replacement? Clin Orthop Relat Res 2001;384:189-97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.EuroQol Group. EuroQol—a new facility for the measurement of health-related quality of life. Health Policy 1990;16:199-208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dolan P, Gudex C, Kind P, Williams A. The time trade-off method: results from a general population study. Health Econ 1996;5:141-54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mahoney FI, Barthel DW. Functional evaluation: the Barthel index. Md State Med J 1965;14:61-5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shepherd SM, Prescott RJ. Use of standardised assessment scales in elderly hip fracture patients. J R Coll Physicians Lond 1996;30:335-43. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Braekhus A, Laake K, Engedal K. The mini-mental state examination: identifying the most efficient variables for detecting cognitive impairment in the elderly. J Am Geriatr Soc 1992;40:1139-45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Davison JN, Calder SJ, Anderson GH, Ward G, Jagger C, Harper WM, et al. Treatment for displaced intracapsular fracture of the proximal femur. A prospective, randomised trial in patients aged 65 to 79 years. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2001;83:206-12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Johansson T, Jacobsson SA, Ivarsson I, Knutsson A, Wahlstrom O. Internal fixation versus total hip arthroplasty in the treatment of displaced femoral neck fractures: a prospective randomized study of 100 hips. Acta Orthop Scand 2000;71:597-602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ravikumar KJ, Marsh G. Internal fixation versus hemiarthroplasty versus total hip arthroplasty for displaced subcapital fractures of femur—13 year results of a prospective randomised study. Injury 2000;31:793-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tidermark J, Bergstrom G. Responsiveness of the EuroQol (EQ-5D) and the Nottingham health profile (NHP) in elderly patients with femoral neck fractures. Qual Life Res 2007;16:321-330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jonsson L, Andreasen N, Kilander L, Soininen H, Waldemar G, Nygaard H, et al. Patient- and proxy-reported utility in Alzheimer disease using the EuroQoL. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord 2006;20:49-55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ankri J, Beaufils B, Novella JL, Morrone I, Guillemin F, Jolly D, et al. Use of the EQ-5D among patients suffering from dementia. J Clin Epidemiol 2003;56:1055-63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Naglie G, Tomlinson G, Tansey C, Irvine J, Ritvo P, Black SE, et al. Utility-based quality of life measures in Alzheimer’s disease. Qual Life Res 2006;15:631-43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Blomfeldt R, Tornkvist H, Ponzer S, Soderqvist A, Tidermark J. Comparison of internal fixation with total hip replacement for displaced femoral neck fractures. Randomized, controlled trial performed at four years. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2005;87:1680-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Keating JF, Grant A, Masson M, Scott NW, Forbes JF. Randomized comparison of reduction and fixation, bipolar hemiarthroplasty, and total hip arthroplasty. Treatment of displaced intracapsular hip fractures in healthy older patients. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2006;88:249-60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke rt-PA Stroke Study Group. Tissue plasminogen activator for acute ischemic stroke. N Engl J Med 1995;333:1581-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Uyttenboogaart M, Stewart RE, Vroomen PC, De KJ, Luijckx GJ. Optimizing cutoff scores for the Barthel index and the modified Rankin scale for defining outcome in acute stroke trials. Stroke 2005;36:1984-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Parker MJ, Khan RJ, Crawford J, Pryor GA. Hemiarthroplasty versus internal fixation for displaced intracapsular hip fractures in the elderly. A randomised trial of 455 patients. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2002;84:1150-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rogmark C, Carlsson A, Johnell O, Sernbo I. A prospective randomised trial of internal fixation versus arthroplasty for displaced fractures of the neck of the femur. Functional outcome for 450 patients at two years. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2002;84:183-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Blomfeldt R, Tornkvist H, Ponzer S, Soderqvist A, Tidermark J. Internal fixation versus hemiarthroplasty for displaced fractures of the femoral neck in elderly patients with severe cognitive impairment. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2005;87:523-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Roden M, Schon M, Fredin H. Treatment of displaced femoral neck fractures: a randomized minimum 5-year follow-up study of screws and bipolar hemiprostheses in 100 patients. Acta Orthop Scand 2003;74:42-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Frihagen F, Madsen JE, Aksnes E, Bakken HN, Maehlum T, Walloe A, et al. Comparison of re-operation rates following primary and secondary hemiarthroplasty of the hip. Injury 2007;38:815-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Roberts C, Parker MJ. Austin-Moore hemiarthroplasty for failed osteosynthesis of intracapsular proximal femoral fractures. Injury 2002;33:423-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lu-Yao GL, Keller RB, Littenberg B, Wennberg JE. Outcomes after displaced fractures of the femoral neck. A meta-analysis of one hundred and six published reports. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1994;76:15-25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Parker MJ, Stockton G. Internal fixation implants for intracapsular proximal femoral fractures in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2001;(4):CD001467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Parker MJ, Gurusamy K. Arthroplasties (with and without bone cement) for proximal femoral fractures in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2006;(3):CD001706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]