Abstract

Fibronectin (FN) has a complex pattern of alternative splicing at the mRNA level. One of the alternatively spliced segments, EDA, is prominently expressed during biological processes involving substantial cell migration and proliferation, such as embryonic development, malignant transformation, and wound healing. To examine the function of the EDA segment, we overexpressed recombinant FN isoforms with or without EDA in CHO cells and compared their cell-adhesive activities using purified proteins. EDA+ FN was significantly more potent than EDA− FN in promoting cell spreading and cell migration, irrespective of the presence or absence of a second alternatively spliced segment, EDB. The cell spreading activity of EDA+ FN was not affected by antibodies recognizing the EDA segment but was abolished by antibodies against integrin α5 and β1 subunits and by Gly-Arg-Gly-Asp-Ser-Pro peptide, indicating that the EDA segment enhanced the cell-adhesive activity of FN by potentiating the interaction of FN with integrin α5β1. In support of this conclusion, purified integrin α5β1 bound more avidly to EDA+ FN than to EDA− FN. Augmentation of integrin binding by the EDA segment was, however, observed only in the context of the intact FN molecule, since the difference in integrin-binding activity between EDA+ FN and EDA− FN was abolished after limited proteolysis with thermolysin. Consistent with this observation, binding of integrin α5β1 to a recombinant FN fragment, consisting of the central cell-binding domain and the adjacent heparin-binding domain Hep2, was not affected by insertion of the EDA segment. Since the insertion of an extra type III module such as EDA into an array of repeated type III modules is expected to rotate the polypeptide up to 180° at the position of the insertion, the conformation of the FN molecule may be globally altered upon insertion of the EDA segment, resulting in an increased exposure of the RGD motif in III10 module and/or local unfolding of the module. Our results suggest that alternative splicing at the EDA exon is a novel mechanism for up-regulating integrin-binding affinity of FN operating when enhanced migration and proliferation of cells are required.

Fibronectins (FNs)1 are multifunctional adhesive glycoproteins present in the extracellular matrix and various body fluids. They provide excellent substrates for cell adhesion and spreading, thereby promoting cell migration during embryonic development, wound healing, and tumor progression (for review see Hynes, 1990). FNs are disulfide-bonded dimers of two closely related subunits, each consisting of three types of homologous repeating modules termed types I, II, and III (Petersen et al., 1983). These repeats are organized into a series of functional domains that bind to integrins, collagens, heparin and heparan sulfate, fibrin, and FNs themselves.

FNs can interact with cells at three distinct regions: the central cell-binding domain (CCBD), the COOH-terminal heparin-binding domain (Hep2), and the type III-connecting segment (IIICS) including the CS1 region (Yamada, 1991). CCBD is the major cell-adhesive domain of FN and contains the Arg-Gly-Asp (RGD) motif that is recognized by members of the integrin family of cell adhesion receptors, including α5β1, αvβ1, αvβ3, αvβ5, αvβ6, αIIbβ3, and α8β1 (Ruoslahti and Pierschbacher, 1987; Hynes, 1992; Müller et al., 1995; Chen et al., 1996). α5β1 is the primary FN receptor in many cell types and differs from the αv- and αIIb-containing integrins in that it requires not only the III10 module containing the RGD motif, but also the III9 module for binding to FN (Aota et al., 1991). Recently, a short sequence Pro-His-Ser-Arg-Asn (PHSRN) has been identified as a synergistic motif in FN for binding to integrins α5β1 (Aota et al., 1994) and αIIbβ3 (Bowditch et al., 1994). Interaction of α5β1 with CCBD has been shown to transduce signals that regulate cell proliferation, differentiation, and apoptosis (Giancotti and Ruoslahti, 1990; Meredith et al., 1993), although the molecular basis for integrin-mediated signaling is not well understood. The importance of the FN-integrin α5β1 interaction has been demonstrated in mice by the embryonic lethality of deficiencies in either FN or α5β1 expression (George et al., 1993; Yang et al., 1993).

FNs purified from different sources appear to be slightly different with respect to subunit sizes (Yamada and Kennedy, 1979). The heterogeneity of FN subunits arises mainly from alternative splicing of a primary transcript at three distinct regions termed EDA, EDB, and IIICS (Schwarzbauer et al., 1983, 1987; Kornblihtt et al., 1984; Zardi et al., 1987). The EDA and EDB segments are each encoded by a single exon and can each comprise an intact type III repeat (Schwarzbauer et al., 1987). The IIICS segment, on the other hand, consists of five distinct variants due to exon subdivision (Kornblihtt et al., 1985; Sekiguchi et al., 1986). Up to 20 different FN subunits may result from alternative splicing involving these three segments. Many lines of evidence indicate that alternative splicing at these regions is regulated in a tissue-specific and oncodevelopmental manner. For example, plasma FN produced by adult hepatocytes contains neither EDA nor EDB segments in both subunits and lacks the entire IIICS in one of the subunits, although cultured fibroblasts typically produce some FNs containing the EDA and/or EDB segments (Kornblihtt et al., 1984; Sekiguchi et al., 1986; Zardi et al., 1987). FNs expressed in fetal and tumor tissues contain a greater percentage of EDA and EDB segments than those expressed in normal adult tissues (Oyama et al., 1989a ,b; 1993; Carnemolla et al., 1989; ffrench-Constant and Hynes, 1989). Increased expression of FNs containing the EDA and/or EDB segments has also been observed during wound healing (ffrench-Constant et al., 1989).

Despite accumulated evidence for regulated expression of EDA- and/or EDB-containing FNs in vivo, the biological functions of these isoforms are only poorly understood. Many efforts have been made to detect functional differences between plasma FN and FNs purified from conditioned medium of cultured fibroblasts, collectively referred to as “cellular FN,” and to elucidate the function of alternatively spliced coding regions. No clear differences have been reported, however, between plasma and cellular FNs in their abilities to promote cell adhesion and spreading, except that these two forms differ in their solubilities (for review see ffrench-Constant, 1995). Since cellular FN is a mixture of heterodimers of several different subunits differing with respect to the presence or absence of the EDA and/or EDB segments, failure to detect functional differences could be due to heterogeneity of cellular FN. To overcome this problem, Guan et al. (1990) expressed, in mouse lymphoid cells, various recombinant isoforms of rat FNs, each containing a different combination of the three alternatively spliced regions, and compared the biological activities of the homogeneous recombinant proteins. No clear differences were, however, observed among the abilities of FN isoforms to promote cell adhesion, spreading, and migration, except for minor differences in the ability to assemble into the preexisting extracellular matrix.

Recently, we constructed an expression vector encoding full length human plasma FN that lacks both the EDA and EDB segments but includes IIICS and overexpressed this recombinant isoform in human tumor cells to restore the pericellular FN matrix around the tumor cells (Akamatsu et al., 1996). In the present study, we constructed two additional expression vectors encoding human FNs containing either both the EDA and EDB segments or the EDA segment alone and overexpressed these FN isoforms in CHO cells to compare the biological activities of three distinct forms of recombinant FNs (i.e., EDA−/EDB−, EDA+/ EDB−, and EDA+/EDB+ FNs) using purified homodimeric proteins. Our results showed that the EDA+ isoform was more than twice as effective as the EDA− isoform in promoting cell spreading and cell migration, irrespective of the presence or absence of the EDB segment. Increased cell adhesion and migration on the EDA+ FN substrate was apparently due to an increase in the binding affinity of integrin α5β1. We discuss molecular mechanisms and implications of the EDA-dependent enhanced integrin binding on the basis of conformational modulation of the FN molecule by insertion of the EDA segment.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

cDNA Construction

cDNA expression vectors for the full length human FN isoforms differing in the presence or absence of the EDA and/or EDB segments were constructed by modifying pAIPFN that encodes a full length FN lacking both extra type III repeats (Akamatsu et al., 1996). pAIPFN was first modified to delete the BamHI site located 5′ to the ATG initiation codon as follows: pAIPFN was cleaved with BamHI and EcoRV and the resulting 2411-bp cDNA fragment encoding the signal sequence of human protein C inhibitor and NH2-terminal FN sequence was filled in using the Klenow fragment of DNA polymerase I and subcloned into the EcoRV site of pBluescript II (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA). The insert was excised as 1703-bp HindIII–SalI fragment and ligated into HindIII–SalI-cleaved pAIPFN, yielding the expression vector (pAIFNC) for the FN isoform lacking both the EDA and EDB segments. pAIFNC is identical to pAIPFN except for the absence of the 5′ BamHI site.

For construction of the expression vector encoding the FN isoform containing EDA but not EDB, a BamHI–XbaI fragment of pHCF5 (provided by Dr. K. Ichihara-Tanaka, Fujita Health University, Toyoake, Japan) that encodes the EDA segment and its flanking region (Arg1449–Ser2308) was cloned into the BamHI site of pUC119 in tandem with a XbaI– BamHI fragment of pAIFNC that comprises the sequence encoding Ser2308–Glu2446 and the 3′ untranslated sequence including a polyadenylation signal. Amino acids are numbered from the NH2-terminal pyroglutamic acid in the mature protein (Petersen et al., 1989). The whole insert was then excised with BamHI and inserted into BamHI-cleaved pAIFNC. The resulting cDNA expression vector for the EDA+/EDB− FN was designated pAIFNAC.

For construction of the expression vector encoding the FN isoform containing both EDA and EDB segments, a KpnI–SpeI fragment encoding Val527–Arg1449 without the EDB segment was excised from pHCF93 (provided by Dr. K. Ichihara-Tanaka), filled in with the Klenow fragment of DNA polymerase I, and subcloned into the HincII site of pUC119 from which the SacI site had been deleted. A 1.6-kbp fragment encoding Val527– Ser1059 was excised from the pUC119 derivative (designated pHCFN93) with EcoRI and SacI and ligated into EcoRI–AccI-cleaved pHCFN93 in tandem with the PCR-amplified SacI–AccI fragment that encodes Ser1200–Val1401 including the EDB segment. The resulting plasmid was linearized with SacI and ligated with the SacI fragment of pHCFN93 encoding Ser1059–Ser1200, yielding pHCFN93B+. The whole insert of pHCFN93B+ was excised with SalI and BamHI, and ligated to SalI–BamHI-cleaved pAIFNC. The plasmid was then recut with BamHI and ligated with the BamHI fragment excised from pAIFNAC (encoding Arg1449 through the SV40 polyadenylation signal). The resulting cDNA expression vector for EDA+/EDB+ FN was designated pAIFNBAC.

Cell Culture

Human HT1080 fibrosarcoma cells, human WI-38 fibroblasts, rat NRK cells, and hamster CHO-K1 cells were obtained from the Japanese Cancer Research Resources Bank (Tokyo, Japan). Mouse L cells were provided by Dr. Masahiro Ishiura (National Institute for Basic Biology, Okazaki, Japan). The heparan sulfate-deficient CHO cell line 803, which expresses 5–10% of the wild-type level of heparan sulfate (Esko et al., 1988) was provided by Dr. Shigeki Higashiyama (Osaka University Medical School, Osaka, Japan). The dihydrofolate reductase-deficient CHO cell line, CHO DG44, was provided by Dr. Lawrence Chasin (Columbia University, New York) and used for the production of recombinant FNs. HT1080, WI-38, NRK, and L cells were grown in DME supplemented with 10% FBS. CHO cell lines were maintained in α-minimal essential medium containing ribonucleosides and deoxyribonucleosides (GIBCO BRL, Gaithersburg, MD) plus 10% FBS.

DNA Transfection and Selection of Stable Transfectants

cDNA expression vectors were cotransfected into CHO DG44 cells with pGEMSVdhfr encoding a dehydrofolate reductase minigene (provided by Dr. Hiroshi Teraoka, Shionogi Research Laboratory, Shionogi and Co., Ltd., Osaka, Japan) by the calcium-phosphate precipitation method (Chen and Okayama, 1987). Selection of stable transfectants and subsequent amplification of the introduced cDNA were carried out as described (Kaufman, 1989). Levels of recombinant FN expression were routinely monitored by dot immunoassay of the culture supernatants with the anti– human FN mAb FN8-12 (Matsuyama et al., 1994). Levels of recombinant FN expression in clones thus selected were >40 times higher than that of endogenous FN expression in untransfected CHO DG44 cells.

Purification of FNs

CHO transfectants overexpressing recombinant human FNs were cultured in α-minimal essential medium with 1% FN-depleted FBS. FN-depleted FBS was prepared by passing through a gelatin-affinity column twice. The culture supernatants were subjected to affinity chromatography using gelatin-Sepharose (Pharmacia Biotech, Uppsala, Sweden). Plasma and cellular FNs were purified as described previously (Sekiguchi et al., 1985). Typical yields of recombinant FNs were 4–6 mg/liter of conditioned media. In some experiments, gelatin affinity-purified FNs were further purified by ion exchange chromatography on a HiTrap-Q column (Pharmacia Biotech).

Antibodies and Peptides

mAbs against integrin α5 and β1 subunits, 8F1 and 4G2, were established in our laboratory by fusion of SP2/0 myeloma cells with the spleen cells of BALB/c mice immunized with integrin α5β1 purified from human placenta. 8F1 and 4G2 inhibit binding of integrin α5β1 to FN as well as attachment and spreading of HT1080 cells on FN-coated substrata. mAbs against human FN, 15E, and 17C were also established in our laboratory using human plasma FN as immunogen. 15E and 17C recognize epitopes on CCBD and the Hep2 domain, respectively. mAbs against the human integrin α4 subunit (SG/73; Miyake et al., 1992) and heparan sulfate (HepSS-1) were obtained from Seikagaku Corp. (Tokyo, Japan); mAb against human integrin αvβ3 (LM609) was from Chemicon International, Inc. (Temecula, CA); mAbs against human FN (FN8-12 and FN30-8) were from Takara Shuzo (Kyoto, Japan); HRP-conjugated mAb against human FN (OAL115) from Hisanobu Hirano (Otsuka Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Tokushima, Japan); mAbs against EDA (IST-9; Borsi et al., 1987) and against FN containing the EDB segment (BC-1) from Dr. Luciano Zardi (Instituto Nazionale per la Ricerca sul Cancro, Genova, Italy); another mAb against EDA (HHS01; Hirano et al., 1992) from Eiji Sakashita (Otsuka Pharmaceutical Factory, Inc., Tokushima, Japan). Polyclonal antibody against human FN was raised in rabbits by repeated immunization with purified human plasma FN emulsified in complete Freund's adjuvant. The polyclonal antibody was purified on a Sepharose affinity column conjugated with a recombinant CCBD fragment (Chen et al., 1996). Control IgG, goat anti–mouse IgG, HRP-conjugated goat anti–rabbit IgG, and FITC-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgM were from Cappel Worthington Biochemicals (Malvern, PA). The synthetic peptides Gly-Arg-Gly-Asp-Ser-Pro (GRGDSP) and Gly-Arg-Gly-Glu-Ser-Pro (GRGESP) were obtained from Iwaki Glass Co. (Chiba, Japan).

MBP- and GST-Fusion Proteins

Two cDNAs encoding the III11 and III12 modules of human FN with or without the inserted EDA segment were amplified by reverse transcription PCR from mRNA extracted from WI-38 human fibroblasts using forward and reverse primers tagged with BamHI and SalI sites, respectively. The primers used were: 5′-AAAGTCGGATCCGAAATTGACAAACCATCC-3′ (forward) and 5′-AAAGTCGAC CTACTCCAGAGTGGTGACAAC-3′ (reverse), where restriction sites and the stop codon are indicated with bold and italic characters, respectively. PCR-amplified fragments were cloned between the BamHI and SalI sites of pMAL-cRI (New England Biolabs, Beverly, MA) to engineer expression in Escherichia coli as fusion proteins with maltose-binding protein (MBP). The resulting fusion proteins, designated MBP11-12 and MBP11-A-12 (see Fig. 1), were purified from the bacterial lysate using amylose resin columns.

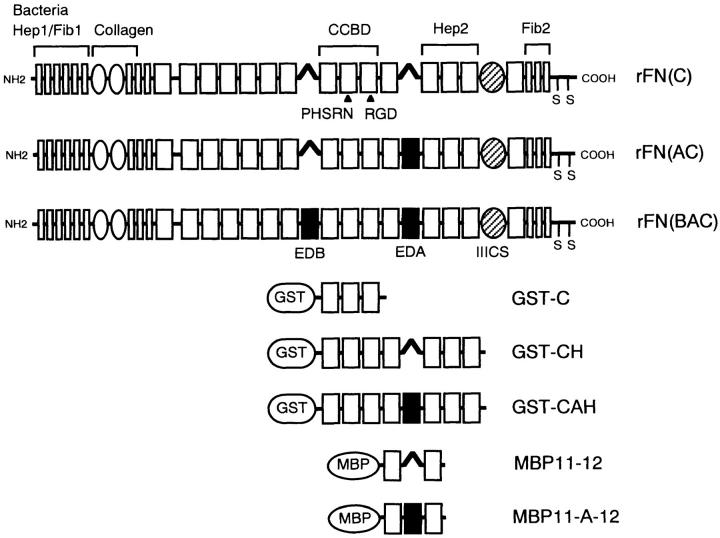

Figure 1.

The structure of recombinant FNs and bacterially expressed fusion fragments. Modular structures of recombinant FNs are shown schematically on the basis of internally homologous modules termed types I, II, and III. The EDA and EDB segments are shown with filled rectangles, while the IIICS segment is shown by a hatched oval. All recombinant FNs contain the complete IIICS sequence of 120 amino acids. Functional domains that interact with heparin (Hep1, Hep2), fibrin (Fib1, Fib2), bacteria, collagen, and cell surface integrins (CCBD) are indicated above the schemes. Recombinant FN fragments encompassing different intervals of type III modules were produced as fusion proteins with either GST or MBP.

Recombinant fragments encompassing CCBD-Hep2 interval were prepared as fusion proteins with glutathione-S-transferase (GST). cDNA fragments encoding the III8–III14 modules with or without the EDA segment were amplified by PCR from pAIFNBAC and pAIFNC, respectively, using the following primers: 5′-ACACCCGGGTGCTGTTCCTCCTCCCACTGAC-3′ (forward) and 5′-ACGCGTCGAC CTA ATAGTCTACATCTTCCCTGGGAATGTGACCAATTTGGATTTCCTCTGTC - TTTTTCCTCCCAATC-3′ (reverse), where the bold and italic characters indicate the restriction sites (SmaI and SalI) and stop codon, respectively, and the underline denotes a tag sequence derived from the Δ2 region of human FN (Sekiguchi and Titani, 1989). cDNA fragments were cleaved with SmaI and SalI and cloned into pGEX4T-1 (Pharmacia Biotech). The plasmids were expressed in the E. coli strain BL21, and the resulting GST fusion proteins (designated GST-CAH and GST-CH; see Fig. 1) were purified on glutathione Sepharose columns (Pharmacia Biotech) as suggested by the manufacturer, followed by ion exchange chromatography using a HiTrapQ column. The GST fusion protein containing only CCBD, designated GST-C, was prepared in the same manner except that the cDNA fragment encoding CCBD was amplified by PCR using 5′-TTTCCCGGG TCATGTTCGGTAATTAATGGAAATTG-3′ as the reverse primer.

Fragmentation of Recombinant FNs

Limited proteolysis of recombinant FNs with thermolysin was performed as described previously (Sekiguchi et al., 1985). Briefly, recombinant FNs (100 μg/ml) were digested with thermolysin (2.5 μg/ml) in 20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.6, containing 1.9 mM CAPS, 50 mM NaCl, 0.5 mM EDTA, and 2.5 mM CaCl2 at 22°C for 10 min. The digestion was terminated by addition of phosphoramidon (Peptide Institute, Minoh, Japan) to a final concentration of 4 μg/ml. Under these conditions, the central region of recombinant FNs consisting of III2–III14 modules remained mostly intact and was obtained as 150–120-kD fragments from rFN(C) and as 160–130-kD fragments from rFN(AC) (Sekiguchi et al., 1985). Contiguity of CCBD and the adjacent Hep2 domain was confirmed by immunoblotting analysis of the digests with mAbs directed to CCBD (15E) and the Hep2 domain (17C).

SDS-PAGE and Immunoblot Analysis

SDS-PAGE was performed as described by Laemmli (1970). Purified FNs were separated on 6% polyacrylamide gels and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes. The membranes were stained with mAbs against human FN using ECL reagents (Amersham Corp., Arlington Heights, IL).

Cell Spreading Assay

Cell spreading assays were performed using 96-well microtiter plates (Maxisorp; Nunc, Roskilde, Denmark) coated with various concentrations of recombinant FNs and blocked with 1% BSA. Amounts of recombinant FNs immobilized on plates were determined by ELISA using anti–human FN antiserum or anti-FN mAbs. HT1080 cells were plated at a density of 2–3 × 104 cells/well in DME and incubated at 37°C for 30 min. For inhibition assays with anti-integrin antibodies and peptides, HT1080 cells were preincubated at 37°C for 15 min in DME containing 0.2% BSA and mAbs (10 μg/ml), synthetic peptides (1 mg/ml), or MBP fusion proteins (100 μM). The pretreated cells were dispersed by pipetting before plating. For inhibition assays using anti-FN mAbs, the 96-well plates coated with recombinant FNs were incubated with mAbs (20 μg/ml) containing 0.1% BSA at 37°C for 30 min before plating of cells. After incubation for specified periods of time at 37°C, nonadherent cells were removed by washing with DME, and attached cells were fixed with 3.7% formaldehyde and then stained with Giemsa. Cells adopting a well spread morphology (i.e., cells that had become flattened with the long axis more than twice the diameter of the nucleus) were counted per square millimeter.

In some experiments, recombinant FNs were immobilized onto 96-well plates via the anti–human FN mAb FN8-12 which had been precoated on the plates. Amounts of the recombinant FNs captured on plates were determined by ELISA using the anti-FN mAb OAL115.

Treatment of Cells with Glycosidases

HT1080 cells were resuspended in DME containing 0.1% BSA at 3 × 105 cells/ml in the presence or absence of 0.1 U/ml of heparitinase I, heparinase, or chondroitinase ABC (Seikagaku Corp.). Cell suspensions were incubated for 30 min at 37°C before the cell spreading assay.

Flow Cytometry

HT1080 cells were stained with the anti-heparan sulfate mAb HepSS-1 (isotype, IgM), followed by incubation with FITC-conjugated goat anti– mouse IgM, and then analyzed using a FACScan® flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson Immunocytometry Systems, San Jose, CA).

Purification of α5β1 and αvβ3 Integrins

Purification of integrin receptors and reconstitution of purified integrins into liposomes were carried out according to Pytela et al. (1987). Briefly, fresh human placental tissue was extracted with TBS(+) (25 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 0.13 M NaCl, 1 mM CaCl2, and 1 mM MgCl2) containing 100 mM octylglucoside and 1 mM PMSF. The extract was applied on a series of Sepharose affinity columns conjugated with either GRGDSPK peptide (for purification of αvβ3) or the 155-kD/145-kD thermolysin fragments of human plasma FN (for purification of α5β1). Integrins bound to these affinity columns were eluted with TBS(+) containing GRGDSP peptide (250 μg/ml). Eluted integrins were further purified on a column of wheat germ lectin Sepharose (Pharmacia Biotech). Purified integrins (50 μg) were mixed with egg yolk phosphatidylcholine (50 μg) containing [3H]dipalmitoyl phosphatidylcholine (New England Nuclear, Boston, MA) in TBS(+) containing 50 mM octylglucoside and then dialyzed against >4,000 vol of TBS(+) at 4°C overnight. The reconstituted integrin liposomes were size fractionated on a Sepharose CL-4B column (Pharmacia Biotech) and used in the integrin liposome binding assay.

Integrin Liposome Binding Assay

Integrin liposomes in TBS(+) containing 0.2% BSA were added to microtiter wells precoated with recombinant FNs (20 μg/ml) or GST fusion fragments (20 or 80 μg/ml) and incubated for 6 h at room temperature. Amounts of recombinant FNs immobilized on wells were verified by ELISA using polyclonal antibody against CCBD. For inhibition assays, the integrin liposomes were preincubated with anti-integrin mAbs (10 μg/ ml unless otherwise specified), control IgG (20 μg/ml), or synthetic peptides (1 mg/ml) for 30 min at room temperature before addition to FN- or fusion fragment-coated wells. The wells were washed with TBS(+), and bound liposomes were recovered in 1 N NaOH. The radioactivity of bound liposomes was quantitated using an Aloka LSC-3500 scintillation counter (Aloka Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan). In the binding assays using thermolysin-cleaved FNs as ligands, phosphoramidon (4 μg/ml) was included in the assay medium to inactivate thermolysin.

Cell Migration Assay

Thin plastic discs (φ 6 mm) were cut in half and coated with 0.01% poly- l-lysine (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, MO) followed by blocking with 1% BSA. Plastic discs were placed in wells of 96-well microtiter plates that had been precoated with 5 μg/ml of recombinant FNs or 0.01% poly- l-lysine and then blocked with 1% BSA. HT1080 cells suspended in DME were seeded onto the plates at a density of 1 × 104 cells/well. After incubation at 37°C for 1.5 h, plastic discs were removed carefully, and the wells were gently washed with DME and photographed. Cells attached to the 96-well plates were further incubated for 12 h in DME to allow them to migrate into the open space left after removal of the discs. The cells were then fixed with 3.7% formaldehyde and stained with Giemsa. Cell motility was assessed by the distance of the outward migration, i.e., the distance between the positions of the cell front before and after cell migration. The assay was also performed in the presence of the anti-integrin α5 mAb 8F1 (20 μg/ml) or control IgG (20 μg/ml).

RESULTS

Construction of Expression Vectors Encoding FN Isoforms Differing in the Inclusion of EDA and/or EDB Segments

Three human FN isoforms used in this study are illustrated in Fig. 1. These isoforms are identical except for the presence or absence of the EDA and/or EDB segments. All three include the complete IIICS sequence of 120 amino acids. FN isoforms were expressed as chimeric proteins with the signal sequence of human protein C inhibitor as described previously (Ichihara-Tanaka et al., 1990). The expression vectors for these isoforms were constructed by modifying the human FN expression vector pAIPFN (Akamatsu et al., 1996) as described in Materials and Methods. The resulting FN isoforms are designated as follows: rFN(C), the isoform lacking both EDA and EDB segments; rFN(AC), the isoform containing EDA but lacking EDB; and rFN(BAC), the isoform containing both EDA and EDB segments.

Expression and Purification of Recombinant FNs

Expression vectors were cotransfected into CHO DG44 cells with a dihydrofolate reductase minigene, and the resulting stable transfectants were treated with increasing concentrations of methotrexate to amplify the introduced recombinant genes. Recombinant FN isoforms were purified from the conditioned media of methotrexate-resistant transfectants by gelatin affinity chromatography. Typical yields of recombinant FNs were 4–6 mg/liter of conditioned medium. Since the concentration of hamster FN in the conditioned medium of untransfected CHO cells was 0.1–0.15 mg/liter, the fraction of contaminating hamster FN in the purified recombinant FNs should not exceed 4% of total protein.

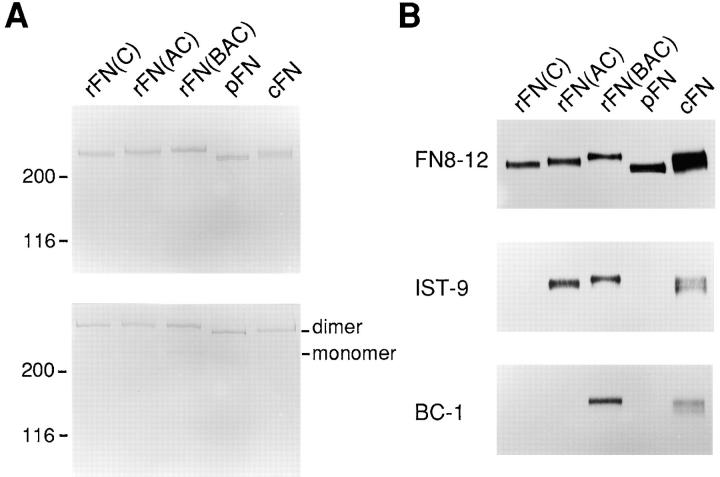

Purified FNs gave single bands with apparent molecular masses of 220–250 kD upon SDS-PAGE under reducing conditions (Fig. 2 A). The relative molecular masses of the recombinant FNs were in the order of rFN(BAC) > rFN(AC) > rFN(C), consistent size differences expected due to the presence or absence of the EDA and/or EDB segments. The recombinant FNs gave sharper bands in SDS-PAGE compared to native FNs purified from plasma (plasma FN) and from conditioned medium of cultured fibroblasts (cellular FN), confirming the homogeneity of the recombinant FNs. SDS-PAGE under nonreducing conditions showed that almost all of the recombinant FNs exist as dimers, as observed for plasma and cellular FNs (Fig. 2 A). Presence or absence of the EDA and EDB segments were confirmed by immunoblot analysis (Fig. 2 B).

Figure 2.

SDS-PAGE and immunoblot analyses of recombinant FNs. (A) Recombinant FNs as well as plasma and cellular FNs (abbreviated pFN and cFN, respectively), both purified by gelatin-affinity chromatography and subsequent ion exchange chromatography on a HiTrap Q column (see Materials and Methods), were subjected to SDS-PAGE under reducing (top gel) or nonreducing (bottom gel) conditions and visualized by Coomassie staining. 2 μg of protein was applied to each lane. Positions of the dimeric and monomeric forms of FNs are indicated in the right margin. Shown in the left are the positions of molecular size markers. (B) Purified FNs (0.6 μg/lane) were subjected to SDS-PAGE under reducing conditions followed by immunoblotting with the following anti-FN mAbs: FN8-12 recognizing Fib2 domain (top panel); IST-9 recognizing the EDA segment (middle panel); BC-1 recognizing the EDB+ FNs (bottom panel).

Cell Adhesive Activity of Recombinant FNs

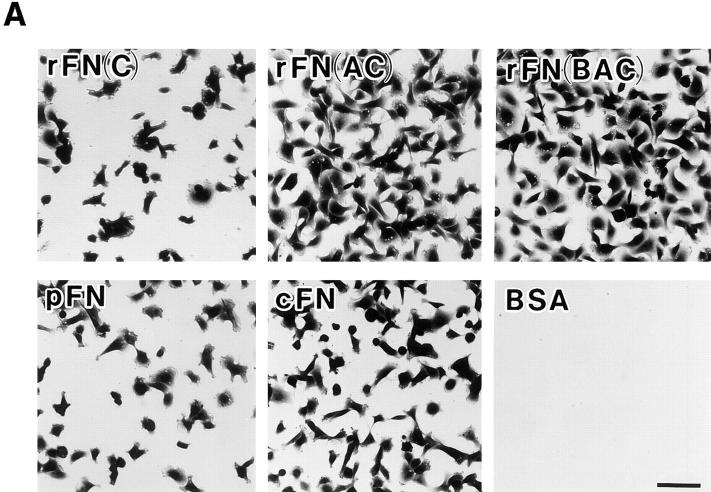

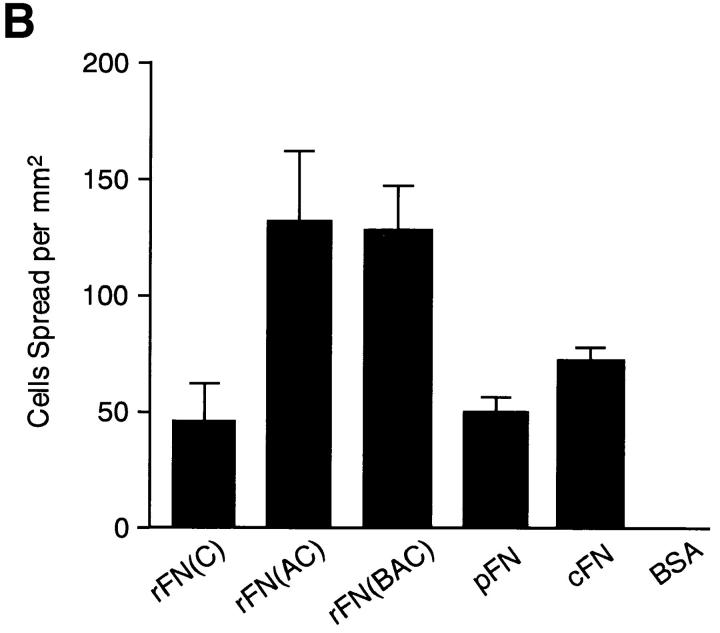

EDA+ FN isoforms have been shown to be expressed prominently in tissues where cells actively proliferate and migrate, such as those in embryos, tumors, and healing wounds. To explore the physiological functions of the EDA segment, we first compared the cell-adhesive activity of recombinant FNs with or without EDA. When HT1080 cells were incubated on substrates coated with recombinant FNs or with plasma or cellular FN, significant differences were seen in the numbers of cells attached to different forms of FNs (Fig. 3 A). HT1080 cells attached in greater numbers to substrates coated with rFN(AC) or rFN(BAC) than to the substrate coated with rFN(C). A similar but less pronounced difference was observed between the substrates coated with plasma or cellular FNs. In addition to promoting more cell attachment, rFN(AC) and rFN(BAC) were more potent in inducing cell spreading than rFN(C) (Fig. 3 B). Similarly, cellular FN was more active than plasma FN in inducing cell spreading, although the difference between cellular and plasma FNs was less evident than between rFN(AC) and rFN(C). No significant difference was found, however, between rFN(AC) and rFN(BAC), indicating that the insertion of the EDB segment did not affect the cell spreading activity of EDA+ FN isoforms. Enhanced cell spreading onto EDA+ FN-coated substrates was also observed with other cell lines including rat NRK cells, mouse L cells, and hamster CHO-K1 cells (data not shown).

Figure 3.

Attachment and spreading of HT1080 cells on FN-coated substratum. (A) HT1080 cells (2 × 104) were seeded on 96-well microtiter plates coated with 5 μg/ml of different FN isoforms and incubated for 30 min at 37°C. The cells were rinsed, fixed, and stained with Giemsa. Bar, 100 μm. (B) Spreading of HT1080 cells was quantified as described in Materials and Methods. The standard deviations of multiple determinations (n = 3) are indicated at the top of bars.

The greater cell-adhesive activity of the EDA-containing isoforms was not an artifact because of variation in quantities of FNs adsorbed onto the substrata, since equal adsorption of FNs onto plastic surfaces was confirmed by: (a) ELISA using different mAbs directed to conserved FN epitopes, and (b) extraction of the substrate-bound FNs with heated SDS-PAGE sample treatment buffer containing 5% 2-mercaptoethanol and subsequent SDS-PAGE (data not shown). Furthermore, essentially identical results were obtained when FNs were indirectly immobilized on the substratum via several different anti-FN mAbs, each recognizing different epitopes present in all FN isoforms tested (data not shown).

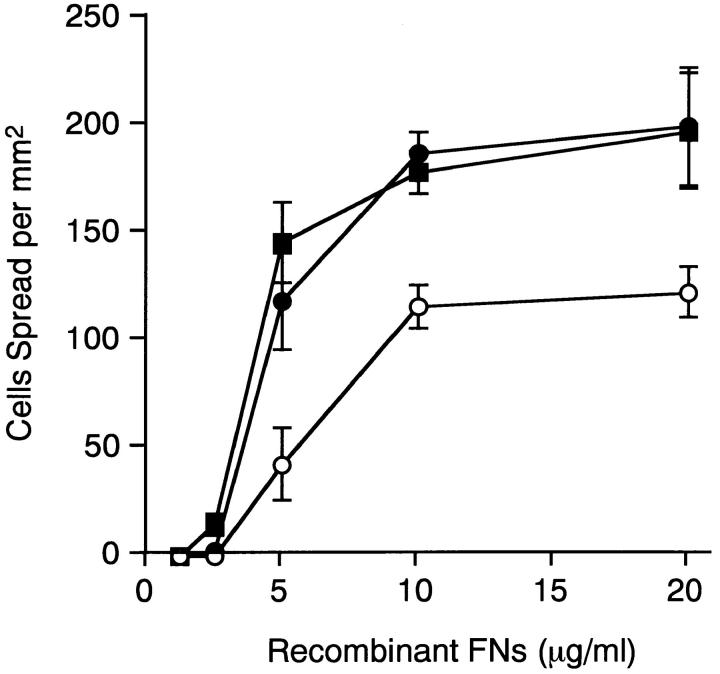

Fig. 4 shows the dose dependence of the spreading of HT1080 cells on different FN isoforms. The number of spread cells reached a plateau at >10 μg/ml of recombinant FNs irrespective of the presence or absence of the alternatively spliced segments. rFN(AC) and rFN(BAC) were more potent than rFN(C) in promoting cell spreading throughout the range of FN concentrations examined. A maximal difference between EDA+ and EDA− isoforms was observed at 5 μg/ml recombinant protein.

Figure 4.

Dose dependence of the spreading of HT1080 cells on recombinant FNs. HT1080 cells were seeded on plates coated with various concentrations of rFN(C) (open circles), rFN(AC) (closed circles), or rFN(BAC) (closed squares) and incubated for 30 min at 37°C. Spreading of HT1080 cells was quantified as described in Materials and Methods and expressed as the number of cells adopting a well spread morphology per square millimeter. Each bar represents the mean ± SD (n = 3).

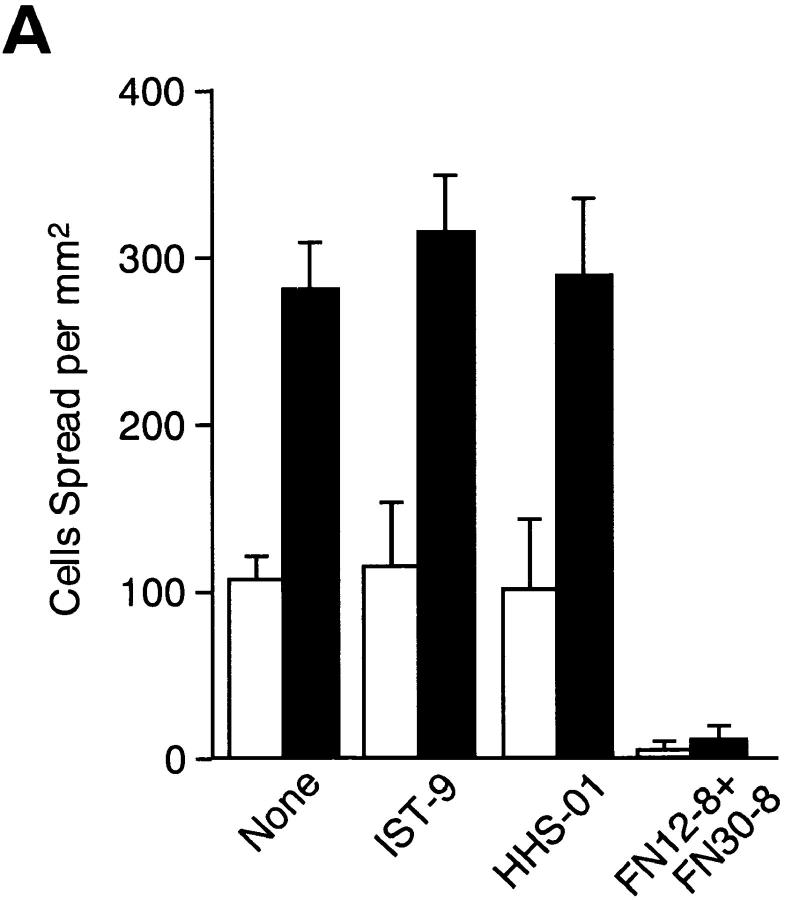

EDA Segment Does Not Contain an Additional Site that Promotes Cell Spreading

One possibility to explain enhanced cell speading on the EDA+ FN isoforms is that the EDA segment may contain an additional cell-interactive site that cooperates additively or synergistically with the RGD motif in CCBD. To explore this possibility, two types of EDA antagonists, i.e., mAbs directed against the EDA segment and recombinant peptide containing the EDA segment, were tested for their abilities to inhibit rFN(AC)-mediated cell spreading. Pretreatment with two distinct anti-EDA mAbs (IST-9 and HHS01) did not inhibit cell spreading on rFN(AC) or rFN(C), whereas the function-blocking mAbs directed against CCBD inhibited cell spreading almost completely on both types of FN isoforms (Fig. 5 A). Furthermore, recombinant peptide MBP11-A-12 containing the EDA segment failed to inhibit cell spreading onto the rFN(AC)- coated substrates, as was the case with the control MBP fusion protein lacking the EDA segment (Fig. 5 B). The inability of the EDA segment to directly interact with HT1080 cells was also supported by the observation that neither MBP11-A-12 nor MBP11-12 could mediate adhesion of HT1080 cells (data not shown). These results, taken together, indicate that the EDA segment is unlikely to be directly involved in enhanced cell adhesion onto the EDA+ FN-coated substrates as an independent cell-interactive site.

Figure 5.

Effects of anti-EDA mAbs and recombinant EDA fragments on cell spreading mediated by recombinant FNs. (A) Microtiter plates precoated with 5 μg/ml of rFN(C) (open bars) or rFN(AC) (closed bars) were treated with the following mAbs (20 μg/ml) at 37°C for 30 min before the addition of HT1080 cells: None, no addition of mAbs; IST-9 and HHS-01, two different anti-EDA mAbs; FN12-8+FN30-8, a mixture of two function-blocking mAbs directed to CCBD. The cells were incubated at 37°C for 30 min and the number of cells adopting a well spread morphology was determined. (B) In separate experiments, HT1080 cells were seeded onto microtiter plates precoated with 5 μg/ml of rFN(C) (open bars) or rFN(AC) (closed bars) and incubated for 30 min at 37°C in the presence or absence of MBP fusion fragments with (MBP11-A-12) and without (MBP-11-12) the EDA segment. Each bar represents the mean ± SD (n = 6).

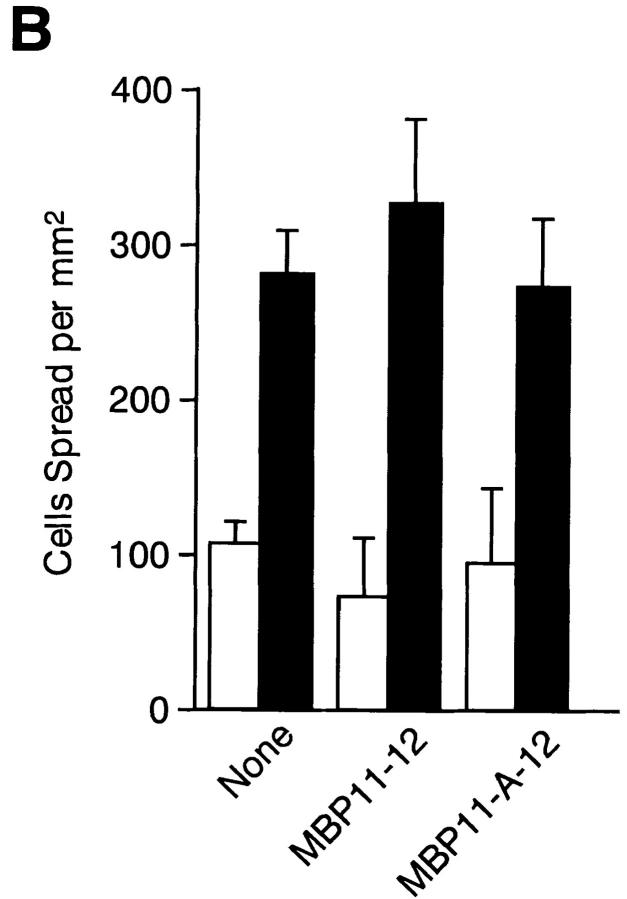

In support of this conclusion, function-blocking mAbs directed against the integrin α5 or β1 subunits inhibited spreading of HT1080 cells onto the rFN(AC)-coated substrates almost completely, whereas the mAbs directed against other types of FN-binding integrins, i.e., anti-α4 and anti-αvβ3 mAbs, were barely inhibitory (Fig. 6). These results indicated that spreading of HT1080 cells onto rFN(AC)-coated substrates was predominantly mediated by interaction of integrin α5β1 with CCBD, as was the case with spreading onto plasma FN-coated substrates (Aota et al., 1991). This conclusion was further supported by the observation that GRGDSP peptide, but not GRGESP, inhibited almost completely rFN(AC)-mediated spreading of HT1080 cells (Fig. 6). These results, together with the failure of EDA antagonists to inhibit rFN(AC)-mediated cell spreading, indicated that the EDA segment augments the cell-adhesive activity of FNs by promoting the interaction of integrin α5β1 with the RGD-containing CCBD and not by providing an additional cell-interactive site.

Figure 6.

Inhibition by anti-integrin mAbs and synthetic peptides of cell spreading mediated by recombinant FNs. HT1080 cells were seeded on microtiter plates precoated with 5 μg/ml of rFN(C) (open bars) or rFN(AC) (closed bars) in the presence or absence of 10 μg/ml of the following anti-integrin mAbs or 1 mg/ ml of synthetic peptides (GRGDSP and GRGESP), and incubated for 30 min at 37°C: None, no mAb added; 8F1, anti-α5 mAb; 4G2, anti-β1 mAb; ST/73, anti-α4 mAb; LM609, anti-αvβ3 mAb. The cell spreading was quantified as described in Materials and Methods. Each bar represents the mean ± SD (n = 6).

Enhanced Cell Adhesive Activity of EDA+ FN Is Independent of Cell Surface Heparan Sulfate

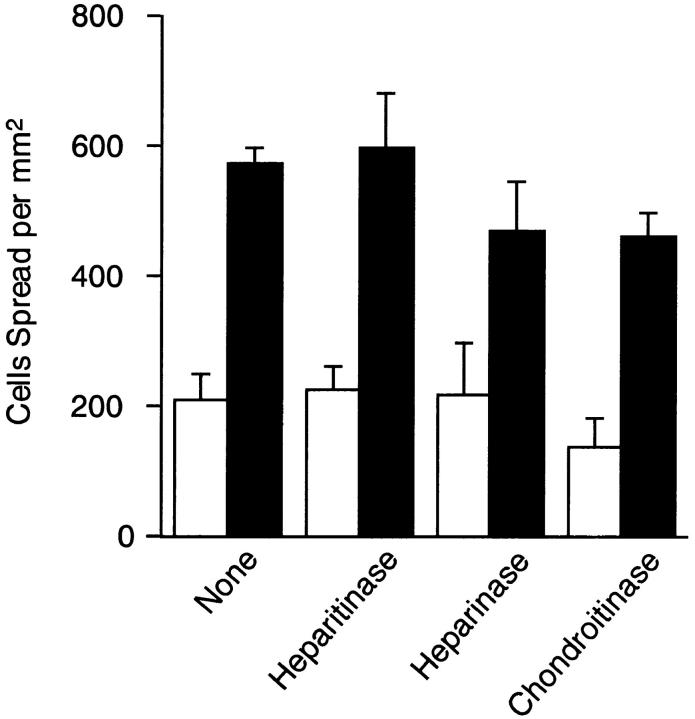

Interaction of the heparin-binding domain of FN with cell surface heparan sulfate has been shown to promote integrin α5β1-mediated cell spreading on FN-coated substrates (Woods et al., 1986). To examine the possible involvement of surface heparan sulfate in enhanced cell spreading onto EDA+ FN-coated substrates, HT1080 cells were treated with heparitinase I before incubation on FN-coated substrates. FACS® analysis using the anti-heparan sulfate mAb HepSS-1 showed that >95% of heparan sulfate on the cell surface was removed by heparitinase treatment (data not shown). The removal of surface heparan sulfate, however, did not significantly affect the spreading of HT1080 cells on substrates coated with either rFN(AC) or rFN(C) (Fig. 7). A similar result was obtained when CHO803 cells that are deficient in surface heparan sulfate (Esko et al., 1988) were used for the cell spreading assay (data not shown), confirming that cell surface heparan sulfate is apparently not involved in enhanced cell spreading seen on rFN(AC)-coated substrates.

Figure 7.

Effect of glycosidase treatments on spreading of HT1080 cells on recombinant FNs. HT1080 cells were treated with 0.1 U/ml of heparitinase I, heparinase, or chondroitinase ABC for 30 min at 37°C. Glycosidase-treated cells were added to microtiter plates precoated with 5 μg/ml of rFN(C) (open bars) or rFN(AC) (closed bars) and incubated for 30 min at 37°C. Cell spreading was quantified as described in Materials and Methods. Each bar represents the mean ± SD (n = 6).

Increased Affinity of Integrin α5β1 to EDA+ FN

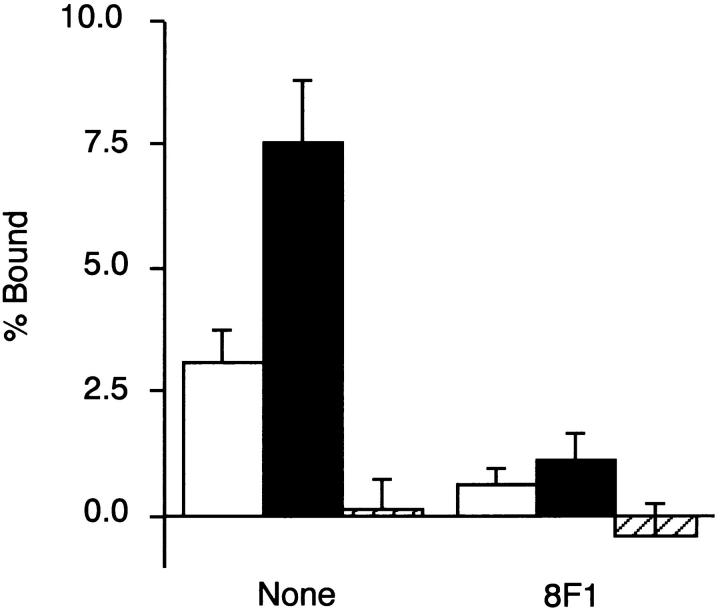

The results described above left us with the possibility that the binding affinity of integrin α5β1 to CCBD could be enhanced by inclusion of the EDA segment. To explore this possibility further, integrin α5β1 purified from human placenta and reconstituted into phosphatidylcholine liposomes containing [3H]dipalmitoyl phosphatidylcholine was tested for its binding avidity to recombinant FNs with or without the EDA segment. As depicted in Fig. 8, integrin α5β1 liposomes bound to rFN(AC) significantly more avidly than to rFN(C). Binding of integrin α5β1 liposomes to rFN(AC) was blocked by the anti-integrin α5 mAb 8F1, as was the case with the binding to rFN(C). No significant binding was observed with vitronectin, confirming that the purified α5β1 used in this study was devoid of other integrins capable of binding to both FN and vitronectin (i.e., αvβ3, αvβ5, αvβ6, and αIIbβ3).

Figure 8.

Binding of integrin α5β1 to recombinant FNs. Integrin α5β1 was purified from human placenta and reconstituted in phosphatidylcholine liposomes as described in Materials and Methods. The integrin α5β1-liposomes were added to microtiter plates precoated either with 20 μg/ml of rFN(C) (open bars) or rFN(AC) (closed bars), or with 5 μg/ml of vitronectin (hatched bars) in the presence or absence of the anti-integrin α5 mAb 8F1 (10 μg/ml) and incubated for 6 h at room temperature. Quantities of bound integrin α5β1 liposomes are expressed as percentage of the total input radioactivity after subtraction of the radioactivity bound to plates coated only with BSA. Each bar represents the mean ± SD (n = 6).

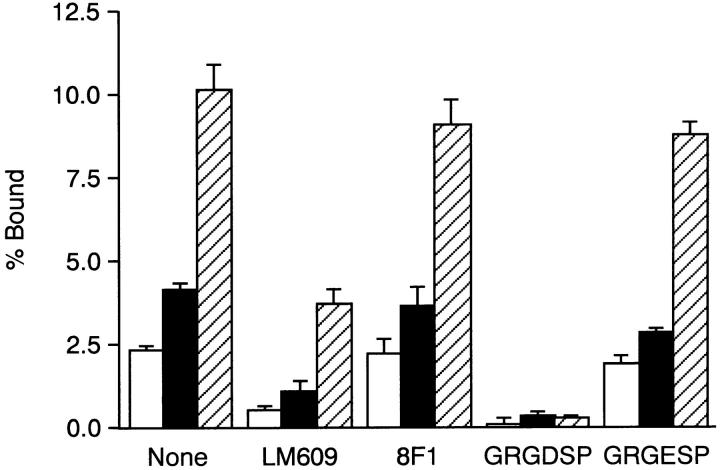

Binding of integrin α5β1 to FN has been shown to depend on both the RGD motif in the III10 module and the synergy site in III9 (Aota et al., 1991). Thus, enhanced binding of integrin α5β1 to rFN(AC) could conceivably be due to increased affinity of the integrin to either the RGD motif or the synergy site. To examine which site was responsible for the enhanced affinity of rFN(AC) towards α5β1, association of integrin αvβ3 with rFN(AC) or rFN(C) was examined. Binding of αvβ3 to FN has been shown to depend on the RGD motif in the III10 module, but not on the synergy site in the III9 module (Danen et al., 1995). Integrin αvβ3 purified from placenta and reconstituted in liposomes bound more avidly to rFN(AC) than to rFN(C), as was the case with α5β1 (Fig. 9). The binding was reproducibly inhibited by the anti-αvβ3 mAb LM609 and by GRGDSP peptide, but not by the anti-α5 mAb 8F1 or the control GRGESP peptide. Residual binding of αvβ3-liposomes to rFN(AC) in the presence of LM609 could result from the presence of αvβ5, another vitronectin-binding integrin, in the purified αvβ3 preparation. These results are consistent with the model that enhanced binding of integrin α5β1 to EDA+ FN is due to an increase in the affinity of α5β1 for the RGD motif in CCBD and that this increased affinity may result from an altered conformation or accessibility of CCBD in the presence of the EDA segment.

Figure 9.

Binding of integrin αvβ3 to recombinant FNs. Integrin αvβ3 liposomes were added to microtiter plates precoated either with 20 μg/ml of rFN(C) (open bars) or rFN(AC) (closed bars) or with 5 μg/ml of vitronectin (hatched bars) in the presence or absence of the anti-integrin αvβ3 mAb LM609 (50 μg/ml), the anti-integrin α5 subunit mAb 8F1 (10 μg/ml), GRGDSP peptide (1 mg/ml), or control GRGESP peptide (1 mg/ml). The binding assay was carried out as described in Fig. 8. Each bar represents the mean ± SD (n = 6).

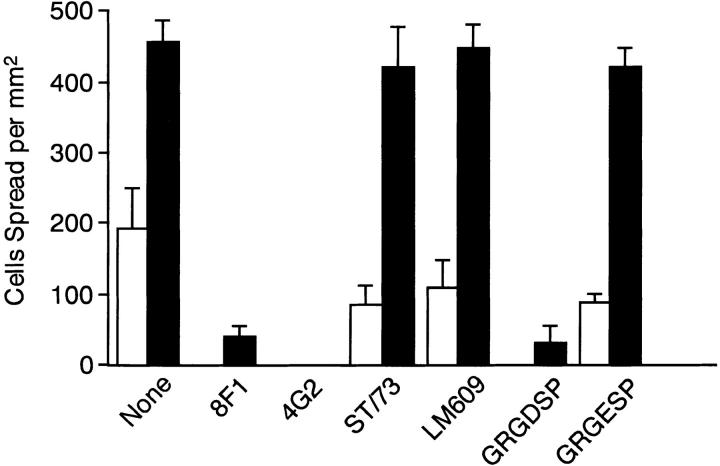

EDA-mediated Enhancement of Integrin Binding Is Not Observed with FN Fragments

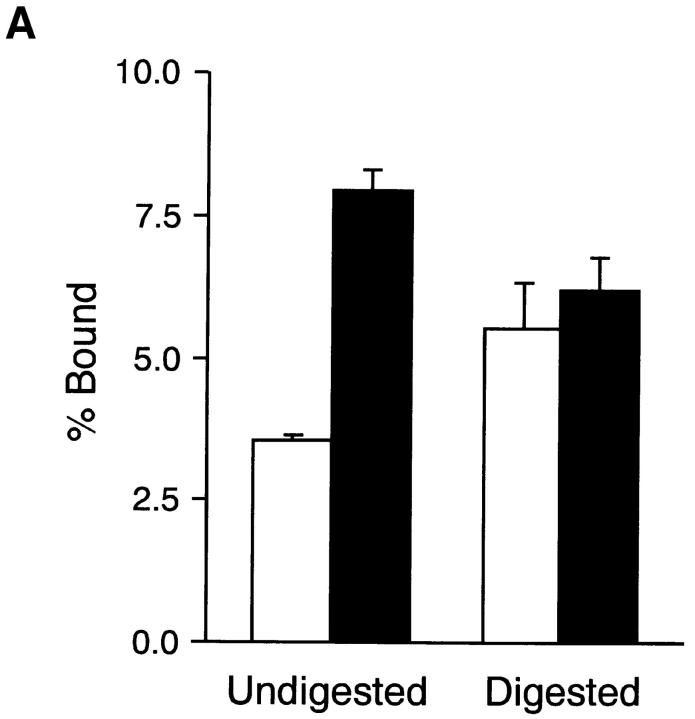

The EDA segment may alter the conformation of CCBD by two possible mechanisms. In one model, the EDA segment inserted between the III11 and III12 modules may induce steric distortion of its neighboring modules, i.e., III11 and III12, by readjusting the intermodular interfaces, which in turn affects the conformation of adjacent modules including RGD-containing III10. Alternatively, insertion of the EDA segment may alter the global conformation of the FN molecule by twisting the NH2-terminal two-thirds of the molecule. Adjacent type III modules have been shown to be interconnected with rotations along the long axis, often in a pseudotwofold relationship (Huber et al., 1994; Leahy et al., 1996). To test these two possibilities, we examined binding affinities of recombinant FNs for integrin α5β1 before and after limited proteolysis with thermolysin. Under the conditions employed (Sekiguchi et al., 1985), the central region of the FN molecule including CCBD and the adjacent Hep2 domain was released by thermolysin as 150–120-kD fragments from rFN(C) and as 160–130-kD fragments from rFN(AC) (data not shown). The integrin-binding activity of rFN(C) was significantly increased after limited proteolysis, reaching a level comparable to that of rFN(AC) after thermolysin digestion (Fig. 10 A). It was also noted that the integrin-binding activity of rFN(AC) was slightly decreased after limited proteolysis. These results do not fit with the first possibility based on the neighboring effects of the inserted EDA segment on the III10 module but rather support the second model that insertion of the EDA segment potentiates integrin binding to CCBD by altering the global conformation of the FN molecule, thereby either increasing integrin accessibility to CCBD or optimizing the local conformation of the RGD-containing III10 module by perturbing the constraints applied to CCBD.

Figure 10.

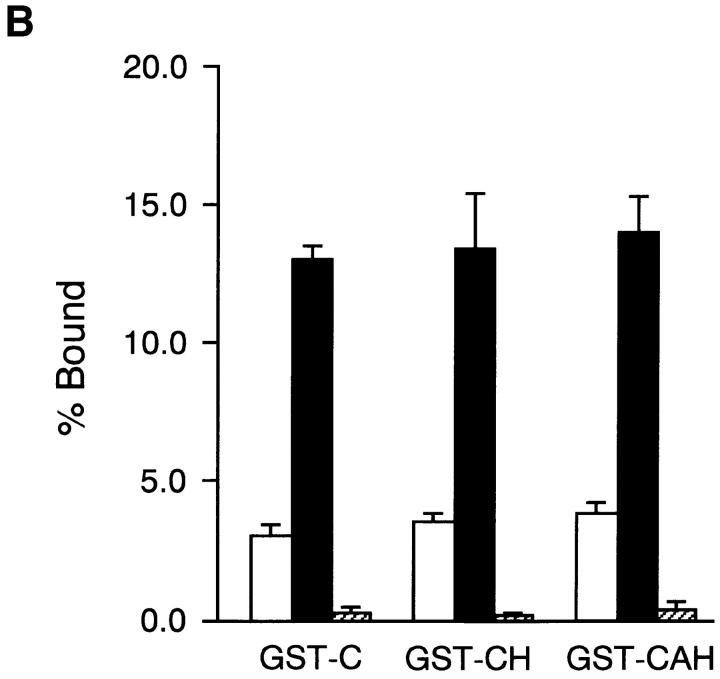

Binding of integrin α5β1 to FN fragments. (A) Microtiter plates were coated with 20 μg/ml of rFN(C) (open bars) or rFN(AC) (closed bars) that had been digested with thermolysin for 0 min (Undigested) and 10 min (Digested) as described in Materials and Methods. The plates were incubated with integrin α5β1 reconstituted in phosphatidylcholine liposomes for 6 h at room temperature. Quantities of bound integrin α5β1 liposomes were expressed as percentages of the total input radioactivity after subtraction of the radioactivity bound to plates coated only with BSA. Each bar represents the mean ± SD (n = 3). (B) Microtiter plates were coated with 20 μg/ml (open bars) or 80 μg/ml (closed and hatched bars) of GST fusion proteins containing the CCBD alone (GST-C) or both the CCBD and the Hep2 domain with (GST-CAH) or without (GST-CH) the EDA segment. Integrin α5β1 liposomes were added to the plates and incubated for 6 h at room temperature in the absence (open and closed bars) or presence (hatched bars) of the anti-integrin α5 mAb 8F1 (10 μg/ml). Each bar represents the mean ± SD (n = 6).

To explore the second possibility further, we expressed in bacteria recombinant FN fragments containing CCBD and the Hep2 domain with or without the inserted EDA segment and examined their binding to purified integrin α5β1. Integrin α5β1 bound equally well to both recombinant CCBD-Hep2 fragments with and without the EDA segment (designated GST-CH and GST-CAH; Fig. 10 B). The integrin binding to these fragments was completely inhibited by the anti-integrin α5 mAb 8F1, confirming the specificity of this binding assay. The recombinant CCBD-Hep2 fragments with and without the EDA segment were also equally active in promoting spreading of HT1080 cells (data not shown). These results provide further support for the conclusion that the EDA segment upregulates the integrin binding activity of CCBD through alteration of global conformation of the FN molecule (see Discussion). It should also be noted that no significant difference was detected in the integrin-binding activities of recombinant CCBD fragments with and without the Hep2 domain, indicating that the binding of CCBD to integrin α5β1 is independent of the adjacent Hep2 domain.

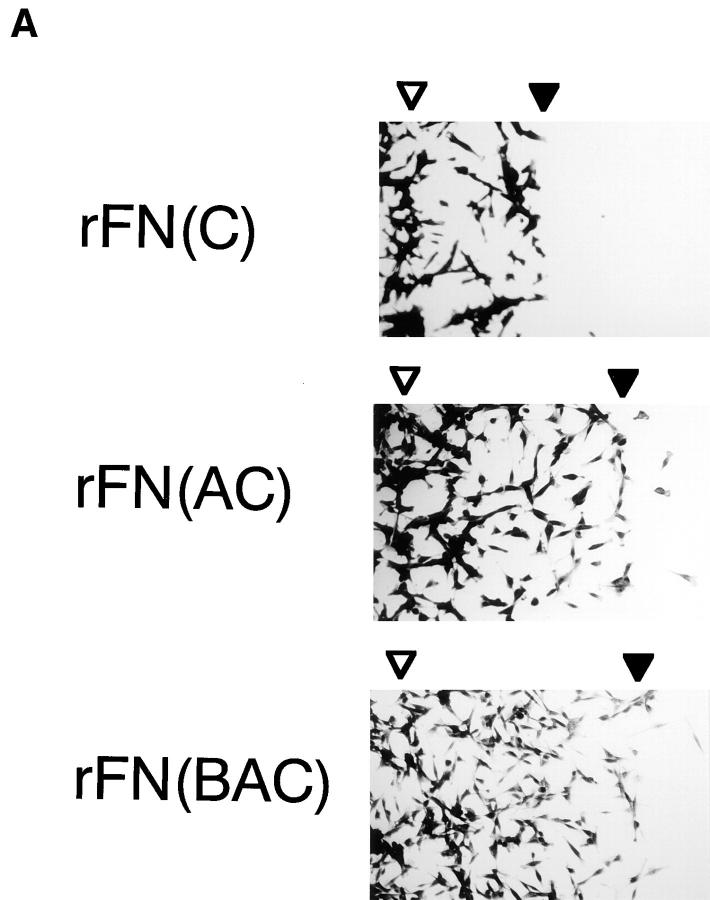

EDA+ FN Is More Active than EDA− FN in Promoting Cell Migration

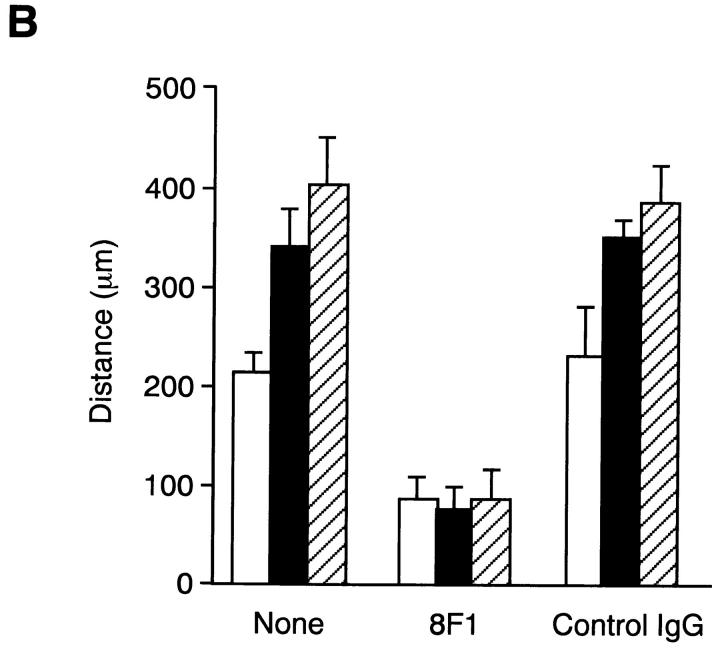

FN is known to promote cell migration via interaction with integrin α5β1 (Yamada et al., 1990). Increased binding avidity of integrin α5β1 for EDA+ FN may, therefore, lead to an enhanced cell motility on substratum coated with EDA+ FN. To test this possibility, migration of HT1080 cells on the substrates coated with EDA+ or EDA− FNs were compared (Fig. 11 A). HT1080 cells were significantly more migratory on rFN(AC) and rFN(BAC) than on rFN(C). No significant cell migration was observed on substrates coated with poly-l-lysine (data not shown). Quantitation of outward cell migration showed that HT1080 cells migrated 1.7–2 times farther on substrates coated with rFN(AC) or rFN(BAC) than on the substrate coated with rFN(C) (Fig. 11 B). Cell migration mediated by EDA+ and EDA− FNs was inhibited by anti-integrin α5 mAb 8F1 to a similar extent, suggesting that increased cell motility on the EDA+ FNs was due to the increased integrin recognition of CCBD flanked with the EDA segment.

Figure 11.

Migration of HT1080 cells on recombinant FNs. 96-well plates were precoated with 5 μg/ml of rFN(C) (open bars), rFN(AC) (closed bars), or rFN(BAC) (hatched bars) and then partially covered with plastic discs (φ 6 mm) that had been cut in half and coated with 0.01% poly-l-lysine. HT1080 cells were seeded onto the plates and incubated for 1.5 h at 37°C to allow them to spread. The plastic discs were then removed and the cells were further incubated at 37°C for 12 h to allow them to migrate into the open space left after removal of the discs. (A) The cells were photographed before and after migration at 37°C for 12 h. The positions of the cell front before and after the cell migration were indicated by open and closed arrowheads, respectively. (B) Cell motility on different substrates was quantified by measuring the distance of outward migration, i.e., the distance between the positions of the cell front before and after cell migration. Cell motility was assayed in the presence or absence of 20 μg/ml of the anti-integrin α5 subunit mAb 8F1 or control IgG. Each bar represents the mean ± SD (n = 6).

DISCUSSION

Though expression of the alternatively spliced EDA and EDB segments of FN show spacial and temporal regulation during development, wound healing, and tumorigenesis, little is known about the function of these variable domains. In the present study, we produced three different forms of recombinant FNs differing with respect to presence or absence of the EDA and/or EDB segments and compared their adhesive functions using homogeneous proteins. Our results showed that recombinant FNs containing the EDA segment were approximately twice as potent as those lacking EDA in their abilities to promote cell adhesion and migration, irrespective of the presence or absence of another variable domain, EDB. The binding affinity of EDA+ FN to its integrin receptor, α5β1, was 2–2.5 times greater than that of EDA− FN, indicating that alternative splicing at the EDA region regulates the binding affinity of FNs to integrin α5β1, thereby contributing to regulation of cell adhesion and migration on FN-containing extracellular matrices.

Functions of alternatively spliced EDA and EDB segments have been extensively studied by comparing the biological activities of the two forms of naturally occurring FNs, i.e., plasma and cellular FNs, only the latter of which contains substantial quantities of the EDA and/or EDB segments. Although plasma and cellular FNs differ in certain molecular properties such as posttranslational modification (Fukuda et al., 1982; Paul and Hynes, 1984) and solubility (Yamada et al., 1977), no significant differences have been found in their cell-adhesive activities (Yamada and Kennedy, 1979). Failure to detect differences in their adhesive properties could be due to heterogeneity of cellular FN used in earlier studies. Typically, cellular FN expressed in cultured fibroblasts contains as much as 50% of EDA− isoforms (Magnuson et al., 1991), leaving only 25% of the entire dimer population as EDA+ homodimers provided that dimerization of different forms of FN polypeptides occurs stochastically. In contrast, recombinant FNs used in this study were homogeneous in terms of the presence or absence of the EDA and/or EDB segments, allowing us to demonstrate clearly enhanced cell-adhesive activity of EDA+ FN isoforms.

Previously, Guan et al. (1990) reported expression and isolation of various forms of rat recombinant FNs. Comparison of the cell-adhesive activity of these recombinant FNs, however, showed no difference between EDA+ and EDA− isoforms. The apparent discrepancy between this report and our present study could be due to the difference in the molecular structure of the recombinant FNs used. The EDA+ FN used by Guan et al. (1990) did not contain the IIICS segment, whereas isoforms tested in the present study all included the complete IIICS segment, which has been shown to be critical for secretion of dimerized nascent FN polypeptides (Schwarzbauer et al., 1989). The EDA+ form of rat FN used by Guan et al. (1990) was predominantly secreted as monomer, whereas rFN(AC) used in the present study was secreted as dimer. It is possible that the IIICS region may be required for EDA-dependent potentiation of the cell-adhesive activity of FNs by ensuring dimer formation or rendering the FN molecule competent for conformational activation upon insertion of the EDA segment (see below).

Several lines of evidence indicate that the EDA segment enhances the cell-adhesive activity of FNs by increasing binding affinity to integrin α5β1 and not by providing an additional cell-adhesive site. Thus, function-blocking mAbs against CCBD or those against integrin α5β1 inhibited rFN(AC)-mediated cell spreading almost completely, while mAbs against the EDA segment showed no inhibition. Consistent with these observations, rFN(AC)-mediated cell spreading was also completely inhibited by GRGDSP peptide but not by the EDA-containing recombinant fragment. Enhanced binding affinity of EDA+ FN to integrin α5β1 was demonstrated by a direct binding assay using integrin α5β1 purified and reconstituted into liposomes.

Previously, Xia and Culp (1994, 1995) reported that a recombinant EDA segment alone or in combination with its neighboring type III modules promoted adhesion of mouse 3T3 cells. The recombinant EDA segment was also reported to transform rat lipocytes into myofibroblasts (Jarnagin et al., 1994). These observations may suggest the presence of a specific cell surface receptor for the EDA segment, although the molecular identity of the receptor remains elusive. Despite these previous reports, we could not obtain evidence to support direct interaction of the EDA segment with cells. Our MBP fusion protein consisting of III11, EDA, and III12 modules did not have an activity to mediate cell attachment or spreading. Although the reason for this discrepancy remains to be clarified, the putative EDA receptor(s) could be expressed only in limited types of cells (e.g., 3T3 cells). It may also be possible that a tag of histidine hexamer added to the recombinant EDA fragment (Xia and Culp, 1994, 1995) could potentiate the interaction of the EDA segment with putative EDA receptor(s).

Recently, Hino et al. (1996) reported that EDA-enriched cellular FN was more potent than plasma FN in promoting adhesion of human synovial cells. Adhesion of synovial cells to EDA-enriched FN was partially inhibited by anti-Hep2 mAb and also by heparitinase treatment of the cells, suggesting that insertion of the EDA segment may enhance the cell-adhesive activity of FN by potentiating the interaction of the Hep2 domain with cell surface heparan sulfate proteoglycans. Despite these observations, our results showed that the interaction of the Hep2 domain with heparan sulfate proteoglycans was not involved in the enhanced adhesion of HT1080 cells on EDA+ FN-coated substrates, since (a) heparitinase treatment did not affect cell spreading onto rFN(AC)-coated substrates; (b) glycosaminoglycan-deficient CHO cells were fully competent to reproduce the difference in the cell spreading activity seen between rFN(AC) and rFN(C); (c) none of the mAbs directed to the Hep2 domain inhibited adhesion of HT1080 cells to rFN(AC)-coated surfaces (Manabe, R., unpublished observation). Although the reason for this discrepancy is not clear, the role of the Hep2 domain in EDA+ FN-mediated cell adhesion may differ among different cell types, synovial cells being strongly dependent on the interaction of the Hep2 domain with heparan sulfate proteoglycans. Since the inhibition of synovial cell adhesion by anti-Hep2 mAb and by heparitinase treatment was only partial (Hino et al., 1996), it is likely that enhanced integrin binding due to the inserted EDA segment was also involved in increased synovial cell adhesion onto EDA-enriched FN.

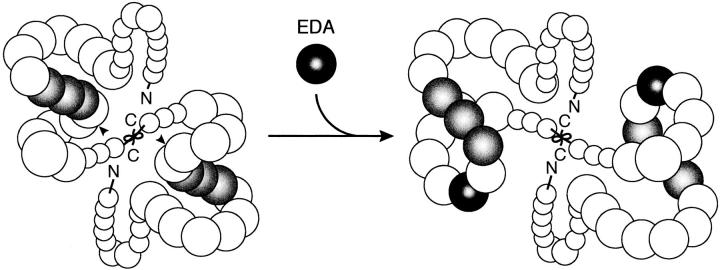

There are several possible mechanisms that may explain enhanced integrin-binding affinity of EDA+ FNs. First, the EDA segment might directly interact with integrins α5β1 and αvβ3, thereby synergizing with the binding of the RGD motif to these integrins (ffrench-Constant, 1995). This possibility seems unlikely, however, since binding of integrin α5β1 to the GST-fusion protein consisting of CCBD and the Hep2 domain was not affected by the presence or absence of the EDA segment. A second possibility is that insertion of the EDA segment alters the conformation of the neighboring type III modules including III10, thereby enhancing the integrin-binding affinity of CCBD (ffrench-Constant, 1995). Analyses of the three- dimensional structure of a recombinant FN fragment consisting of III7–III10 modules revealed that two adjacent type III modules are interconnected with tilts and rotations along the long axis (Leahy et al., 1996). Insertion of an extra type III module (i.e., the EDA module) could alter the conformation of the neighboring modules (i.e., III11 and III12) by readjusting the intermodular rotations and tilts, which could in turn alter the conformation of their neighboring modules including III10 so as to optimize the conformation of the RGD-containing loop. The third possibility is that insertion of the EDA segment alters the global conformation of the FN molecule by rotating the NH2-terminal portion of the FN polypeptide relative to the COOH terminus (Fig. 12). Given a pseudo-twofold relationship between adjacent type III modules (Huber et al., 1994; Leahy et al., 1996), the insertion of the EDA segment is expected to rotate the NH2-terminal two-thirds (the NH2 terminus through III11) up to 180° relative to the COOH-terminal one-third (III12 through the COOH terminus). Such a change in global conformation may not only increase the accessibility of the RGD motif in CCBD to the integrins α5β1 and αvβ3 but also induce partial unfolding of the III10 module by altering the tension and/or torsion applied to CCBD. Our results obtained with thermolysin-cleaved recombinant FNs and GST fusion proteins consisting of CCBD and the Hep2 domain clearly showed that enhanced integrin-binding of EDA+ FN was only observable in the context of the intact FN molecule, consistent with the third possibility. The significant increase in the integrin-binding affinity of EDA− FN after limited proteolysis suggests that the integrin binding site of EDA− FN is either partially cryptic in the intact molecule or folded into a conformation with suboptimal affinity for integrin α5β1. In support of this notion, the binding of plasma FN to hamster kidney cells has been reported to increase up to twofold after tryptic digestion (Hayashi and Yamada, 1983; Akiyama et al., 1985). It should also be noted that the integrin-binding activity of EDA+ FN was slightly decreased after limited proteolysis, suggesting that conformational change induced by the inserted EDA segment not only increases the exposure of the integrin-binding site on the surface of the FN molecule but also perturbs the local conformation of CCBD, particularly the RGD-containing III10, to optimize the affinity for integrin α5β1. In support of this possibility, the FN type III modules have been proposed to undergo reversible unfolding with a relatively weak force that is comparable to that required to dissociate a noncovalent protein–protein interaction (Erickson, 1994).

Figure 12.

A schematic model for EDA-induced conformational change of FN. The FN molecule is folded into a compact conformation due to intra- and/or inter-chain interactions. Insertion of the EDA segment (black) between CCBD (gray) and the Hep2 domain rotates the NH2-terminal region encompassing the NH2 terminus through the III11 module up to 180°C relative to the region COOH-terminal to the inserted EDA segment, leading to a change in the global conformation of the FN molecule. Such a conformational change may increase the accessibility of the RGD motif within CCBD to integrin α5β1 and/or alter the local conformation of the III10 module so as to optimize the binding of integrin α5β1 to the RGD motif. Arrowheads point to the position of the EDA insertion.

Accumulating evidence indicates that the strands of the FN molecule are folded into a compact shape under physiological buffer conditions and undergo conformational transitions from a compact to an extended form in solutions of high ionic strength or high pH (Williams et al., 1982; Erickson and Carrell, 1983). Such conformational transitions have also been observed in monomeric forms of FN subunits produced by reduction and subsequent carboxyamidomethylation of disulfides or by limited proteolysis (Erickson and Carrell, 1983; Benecky et al., 1990), indicating that the FN strands are folded into a compact structure by an intra-chain interaction (although involvement of an inter-chain interaction can not be rigorously excluded). Although the regions involved in intra- and/or inter-chain interaction have not been fully elucidated, the III1 module may play an important role. The III1 module was reported to bind multiple regions in FN including the NH2-terminal 70-kD region, the III10 module, and the COOH-terminal fibrin-binding domain (Aguirre et al., 1994; Hocking et al., 1996; Ingham et al., 1997). It is tempting to speculate that EDA-mediated rotation of the NH2-terminal two-thirds relative to the COOH terminus redirects intra- and/or inter-chain interactions, resulting in transition of the global conformation of the FN molecule from one state to another (Fig. 12).

The proposed EDA-induced change in the global conformation of FN is further supported by the following distinctions between the EDA+ and EDA− FN isoforms. Cellular FN containing EDA and/or EDB segments has been shown to be much less soluble than plasma FN under physiological buffer conditions (Yamada et al., 1977). Altered solubility can be easily explained by changes in global conformation that may increase the exposure of hydrophobic and/or charged surfaces of the FN molecule. Furthermore, alteration in global conformation may be compatible with an increased matrix assembly of the EDA+ FN isoforms. Guan et al. (1990) reported that EDA+ isoforms were more readily incorporated into the extracellular matrix than an isoform lacking both EDA and EDB segments. We also found that rFN(AC) is 2–3-fold more efficient than rFN(C) in assembling into the extracellular matrix (Manabe, R., unpublished observation). Although the molecular mechanisms for FN matrix assembly remain to be elucidated, FNs are considered to undergo a conformational change from a compact to an extended conformation upon binding to integrin receptors on cell surfaces, thereby dissociating intramolecular interactions and exposing sites for FN–FN interaction (Mosher, 1993; Sechler et al., 1996). The EDA-mediated conformational change may accelerate FN matrix assembly by facilitating the conformational activation of FNs upon binding to RGD-dependent integrins, particularly α5β1.

In vivo expression patterns of different FN isoforms suggest a role for EDA+ FN in cell growth as well as in cell migration. The EDA segment is included in FN species expressed in embryonic tissues but is spliced out of the molecule in most tissues as embryonic development progresses (Vartio et al., 1987; ffrench-Constant and Hynes, 1989). In adults, EDA+ FNs reappear during wound healing and in tumor tissues (ffrench-Constant et al., 1989; Oyama et al., 1989a ). In addition, levels of the EDA+ FN expression are significantly higher in invasive tumors than in noninvasive ones (Oyama et al., 1989a ). Since tissues where EDA+ FNs are highly expressed are populated with cells having high proliferative and migratory potentials, it seems likely that EDA+ FNs play an important role in promoting cell proliferation and migration in vivo. In support of this notion, our results show that EDA+ FN is more potent than EDA− FN in promoting migration of HT1080 cells. Under circumstances where vast cell proliferation and migration are required, the splicing pattern at the EDA region is apparently altered to produce more EDA+ FN isoforms and, in so doing, to strengthen signals from the surrounding FN matrix. Regulation of extracellular signals at the level of RNA splicing represents a novel mechanism for the control of proliferation, differentiation, and apoptosis of adherent cells.

Despite the importance of the EDA segment in regulating the cell-adhesive properties of FN, the function of the EDB segment remains to be defined. Since expression of EDB+ FN isoforms in vivo is more restricted than that of EDA+ isoforms (ffrench-Constant and Hynes, 1989), the EDB segment may have an important function only in highly specific situations, such as early embryonic development. By analogy with the EDA segment, the insertion of the EDB segment is expected to alter the global conformation of the FN molecule by rotating the NH2-terminal half (i.e., NH2 terminus through III7) relative to the COOH terminus. Although the EDB segment did not affect the cell-adhesive activity of EDA+ FNs, it may modulate other biological functions of FN through conformational perturbation. Further studies on the biological activities of a panel of recombinant FN isoforms differing with respect to presence or absence of EDA and EDB segments should provide clues to the function of the EDB segment.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Keiko Ichihara-Tanaka for generous gifts of the plasmid pHCF5 and pHCF93, Dr. Luciano Zardi for the mAbs IST-9 and BC-1, Hisanobu Hirano for the mAb OAL115, Eiji Sakashita for the mAb HHS01, and Dr. Masahiro Nakayama (Department of Pathology, Osaka Medical Center for Maternal and Child Health, Osaka, Japan) for allowing us to use term placenta for purification of integrins. We also thank Dr. Judith Healy for valuable comments on this manuscript.

This work was supported by the Special Coordination Fund from the Science and Technology Agency of Japan, the Grants-in-aid for Scientific Research on Priority Areas from the Ministry of Education, Science, and Culture of Japan, and a grant from Osaka Cancer Foundation.

Abbreviations used in this paper

- CCBD

central cell-binding domain

- FN

fibronectin

- GST

glutathione-S-transferase

- MBP

maltose-binding protein

- RGD

Arg-Gly-Asp

Footnotes

Address all correspondence to Kiyotoshi Sekiguchi, Research Institute, Osaka Medical Center for Maternal and Child Health, 840 Murodo, Izumi, Osaka 590-2, Japan. Tel.: (81) 725-56-1220 (ext. 5401). Fax: (81) 725-57-3021. e-mail: j61639@center.osaka-u.ac.jp

REFERENCES

- Aguirre KM, McCormick RJ, Schwarzbauer JE. Fibronectin self-association is mediated by complementary sites within the amino-terminal one-third of the molecule. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:27863–27868. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akamatsu H, Ichihara-Tanaka K, Ozono K, Kamiike W, Matsuda H, Sekiguchi K. Suppression of transformed phenotypes of human fibrosarcoma cells by overexpression of recombinant fibronectin. Cancer Res. 1996;56:4541–4546. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akiyama SK, Hasegawa E, Hasegawa T, Yamada KM. The interaction of fibronectin fragments with fibroblastic cells. J Biol Chem. 1985;260:13256–13260. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aota S, Nagai T, Yamada KM. Characterization of regions of fibronectin besides the arginine-glycine-aspartic acid sequence required for adhesive function of the cell-binding domain using site-directed mutagenesis. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:15938–15943. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aota S, Nomizu M, Yamada KM. The short amino acid sequence Pro-His-Ser-Arg-Asn in human fibronectin enhances cell-adhesive function. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:24756–24761. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benecky MJ, Kolvenbach CG, Wine RW, DiOrio JP, Mosesson MW. Human plasma fibronectin structure probed by steady-state fluorescence polarization: evidence for a rigid oblate structure. Biochemistry. 1990;29:3082–3091. doi: 10.1021/bi00464a027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borsi L, Carnemolla B, Catellani P, Rosellini C, Vecchio D, Allemanni G, Chang SE, Taylor-Papadimitriou J, Pande H, Zardi L. Monoclonal antibodies in the analysis of fibronectin isoforms generated by alternative splicing of mRNA precursors in normal and transformed cells. J Cell Biol. 1987;104:595–600. doi: 10.1083/jcb.104.3.595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowditch RD, Hariharan M, Tominna EF, Smith JW, Yamada KM, Getzoff ED, Ginsberg MH. Identification of a novel binding site in fibronectin: differential utilization by β3 integrins. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:10856–10863. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carnemolla B, Balza E, Siri A, Zardi L, Nicotra MR, Bigotti A, Natali PG. A tumor-associated fibronectin isoform generated by alternative splicing of messenger RNA precursors. J Cell Biol. 1989;108:1139–1148. doi: 10.1083/jcb.108.3.1139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen C, Okayama H. High-efficiency transformation of mammalian cells by plasmid DNA. Mol Cell Biol. 1987;7:2745–2752. doi: 10.1128/mcb.7.8.2745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J, Maeda T, Sekiguchi K, Sheppard D. Distinct structural requirements for interaction of the integrins α5β1, αvβ5, and αvβ6 with the central cell binding domain in fibronectin. Cell Adhes Commun. 1996;4:237–250. doi: 10.3109/15419069609010769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danen EHJ, Aota S, van Kraats AA, Yamada KM, Ruiter DJ, van Muijen GNP. Requirement for the synergy site for cell adhesion to fibronectin depends on the activation state of integrin α5β1. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:21612–21618. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.37.21612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erickson HP. Reversible unfolding of fibronectin type III and immunoglobulin domains provides the structural basis for stretch and elasticity of titin and fibronectin. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:10114–10118. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.21.10114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erickson HP, Carrell NA. Fibronectin in extended and compact conformations: electron microscopy and sedimentation analysis. J Biol Chem. 1983;258:14539–14544. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esko JD, Rostand KS, Weinke JL. Tumor formation dependent on proteoglycan biosynthesis. Science (Wash DC) 1988;241:1092–1096. doi: 10.1126/science.3137658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ffrench-Constant C. Alternative splicing of fibronectin: many different proteins but few different functions. Exp Cell Res. 1995;221:261–271. doi: 10.1006/excr.1995.1374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ffrench-Constant C, Hynes RO. Alternative splicing of fibronectin is temporally and spatially regulated in the chicken embryo. Development. 1989;106:375–388. doi: 10.1242/dev.106.2.375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ffrench-Constant C, Van De Water L, Dvorak HF, Hynes RO. Reappearance of an embryonic pattern of fibronectin splicing during wound healing in the adult rat. J Cell Biol. 1989;109:903–914. doi: 10.1083/jcb.109.2.903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukuda M, Levery SB, Hakomori S. Carbohydrate structure of hamster plasma fibronectin: evidence for chemical diversity between cellular and plasma fibronectins. J Biol Chem. 1982;257:6856–6860. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- George EL, Georges-Labouesse EN, Patel-King RS, Rayburn H, Hynes RO. Defects in mesoderm, neural tube and vascular development in mouse embryos lacking fibronectin. Development. 1993;119:1079–1091. doi: 10.1242/dev.119.4.1079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giancotti FG, Ruoslahti E. Elevated levels of the α5β1 fibronectin receptor suppress the transformed phenotype of Chinese hamster ovary cells. Cell. 1990;60:849–859. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90098-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guan J-L, Trevithick JE, Hynes RO. Retroviral expression of alternatively spliced forms of rat fibronectin. J Cell Biol. 1990;110:833–847. doi: 10.1083/jcb.110.3.833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi M, Yamada KM. Domain structure of the carboxyl-terminal half of human plasma fibronectin. J Biol Chem. 1983;258:3332–3340. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hino K, Maeda T, Sekiguchi K, Shiozawa K, Hirano H, Sakashita E, Shiozawa S. Adherence of synovial cells on EDA-containing fibronectin. Arthritis Rheum. 1996;39:1685–1692. doi: 10.1002/art.1780391011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirano H, Tachikawa T, Hino K, Sakashita E, Sekiguchi K. Development of enzyme-linked immunosorbent assasy (ELISA) for the detection of cellular type fibronectin by EDA-region specific monoclonal antibody. J Clin Lab Inst Reag. 1992;15:179–184. [Google Scholar]

- Hocking DC, Smith RK, McKeown-Longo PJ. A novel role for the integrin-binding III-10 module in fibronectin matrix assembly. J Cell Biol. 1996;133:431–444. doi: 10.1083/jcb.133.2.431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huber AH, Wang YE, Bieber AJ, Bjorkman PJ. Crystal structure of tandem type III fibronectin domains from Drosophilaneuroglian at 2.0 Å. Neuron. 1994;12:717–731. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(94)90326-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hynes, R.O. 1990. Fibronectins. Springer-Verlag, New York. 546 pp.

- Hynes RO. Integrins: versatility, modulation, and signaling in cell adhesion. Cell. 1992;69:11–25. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90115-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ichihara-Tanaka K, Titani K, Sekiguchi K. Recombinant carboxyl-terminal fibrin-binding domain of human fibronectin expressed in mouse L cells. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:401–407. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ingham KC, Brew SA, Huff S, Litvinovich SV. Cryptic self-association sites in type III modules of fibronectin. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:1718–1724. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.3.1718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jarnagin WR, Rockey DC, Koteliansky VE, Wang S, Bissell DM. Expression of variant fibronectins in wound healing: cellular source and biological activity of the EIIIA segment in rat hepatic fibrogenesis. J Cell Biol. 1994;127:2037–2048. doi: 10.1083/jcb.127.6.2037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman RJ. Selection and coamplification. Methods Enzymol. 1989;185:537–566. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(90)85044-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kornblihtt AR, Vibe-Pedersen K, Baralle FE. Human fibronectin: cell specific alternative mRNA splicing generates polypeptide chains differing in the number of internal repeats. Nucleic Acids Res. 1984;12:5853–5868. doi: 10.1093/nar/12.14.5853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kornblihtt AR, Umezawa K, Vibe-Pedersen K, Baralle FE. Primary structure of human fibronectin: differential splicing may generate at least 10 polypeptides from a single gene. EMBO (Eur Mol Biol Organ) J. 1985;4:1755–1759. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1985.tb03847.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laemmli UK. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of the bacteriophage T4. Nature (Lond) 1970;227:680–685. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leahy DJ, Aukhil I, Erickson HP. 2.0 Å crystal structure of a four-domain segment of human fibronectin encompassing the RGD loop and synergy region. Cell. 1996;84:155–164. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81002-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magnuson VL, Young M, Schattenberg DG, Mancini MA, Chen D, Steffensen B, Klebe RJ. The alternative splicing of fibronectin pre-mRNA is altered during aging and in response to growth factors. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:14654–14662. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuyama S, Ichihara-Tanaka K, Sekiguchi K. Targeting of the immunoglobulin-binding domain of protein A to the extracellular matrix using a minifibronectin expression vector. J Biochem. 1994;116:898–904. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a124613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meredith JE, Jr, Fazeli B, Schwartz MA. The extracellular matrix as a cell survival factor. Mol Biol Cell. 1993;4:953–961. doi: 10.1091/mbc.4.9.953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyake K, Hasunuma Y, Yagita H, Kimoto M. Requirement for VLA-4 and VLA-5 integrins in lymphoma cells binding to and migration beneath stromal cells in culture. J Cell Biol. 1992;119:653–662. doi: 10.1083/jcb.119.3.653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mosher DF. Assembly of fibronectin into extracellular matrix. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 1993;3:214–222. [Google Scholar]

- Müller U, Bossy B, Venstrom K, Reichardt LF. Integrin α8β1 promotes attachment, cell spreading and neurite outgrowth on fibronectin. Mol Biol Cell. 1995;6:433–448. doi: 10.1091/mbc.6.4.433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oyama F, Hirohashi S, Shimosato Y, Titani K, Sekiguchi K. Deregulation of alternative splicing of fibronectin pre-mRNA in malignant human liver tumors. J Biol Chem. 1989a;264:10331–10334. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oyama F, Murata Y, Suganuma N, Kimura T, Titani K, Sekiguchi K. Patterns of alternative splicing of fibronectin pre-mRNA in human adult and fetal tissues. Biochemistry. 1989b;28:1428–1434. doi: 10.1021/bi00429a072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oyama F, Hirohashi S, Sakamoto M, Titani K, Sekiguchi K. Coordinate oncodevelopmental modulation of alternative splicing of fibronectin pre-messenger RNA at ED-A, ED-B, and CS1 regions in human liver tumors. Cancer Res. 1993;53:2005–2011. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paul JI, Hynes RO. Multiple fibronectin subunits and their post-translational modifications. J Biol Chem. 1984;259:13477–13487. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersen TE, Thøgersen HC, Skorstengaard K, Vibe-Pedersen K, Sahl P, Sottrup-Jenesen L, Magnusson S. Partial primary structure of bovine plasma fibronectin: three types of internal homology. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1983;80:137–141. doi: 10.1073/pnas.80.1.137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersen, T.F., K. Skorstengaard, and K. Vibe-Pedersen. 1989. Primary structure of fibronectin. In Fibronectin. D.F. Mosher, editor. Academic Press, San Diego, CA. 1–24.

- Pytela R, Pierschbacher MD, Argraves S, Suzuki S, Ruoslahti E. Arginine-glycine-aspartic acid adhesion receptors. Methods Enzymol. 1987;144:475–489. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(87)44196-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruoslahti E, Pierschbacher MD. New perspectives in cell adhesion: RGD and integrins. Science (Wash DC) 1987;238:491–497. doi: 10.1126/science.2821619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwarzbauer JE, Tamkun JW, Lemischka IR, Hynes RO. Three different fibronectin mRNA arise by alternative splicing within the coding region. Cell. 1983;35:421–431. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(83)90175-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwarzbauer JE, Patel RS, Fonda D, Hynes RO. Multiple sites of alternative splicing of the rat fibronectin gene transcript. EMBO (Eur Mol Biol Organ) J. 1987;6:2573–2580. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1987.tb02547.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwarzbauer JE, Spencer CS, Wilson CL. Selective secretion of alternatively spliced fibronectin variants. J Cell Biol. 1989;109:3445–3453. doi: 10.1083/jcb.109.6.3445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sechler JL, Takada Y, Schwarzbauer JE. Altered rate of fibronectin matrix assembly by deletion of the first type III repeats. J Cell Biol. 1996;134:573–583. doi: 10.1083/jcb.134.2.573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sekiguchi K, Titani K. Probing molecular polymorphism of fibronectins with antibodies directed to the alternatively spliced peptide segments. Biochemistry. 1989;28:3293–3298. doi: 10.1021/bi00434a026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sekiguchi K, Siri A, Zardi L, Hakomori S. Differences in domain structure between human fibronectins isolated from plasma and from culture supernatants of normal and transformed fibroblasts: studies with domain-specific antibodies. J Biol Chem. 1985;260:5105–5114. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sekiguchi K, Klos AM, Kurachi K, Yoshitake S, Hakomori S. Human liver fibronectin complementary DNAs: identification of two different messenger RNAs possibly encoding the α and β subunits of plasma fibronectin. Biochemistry. 1986;25:4936–4941. doi: 10.1021/bi00365a032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]