Abstract

Non-homologous end-joining is an important pathway for repairing DNA double-strand breaks. The budding yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae possesses two proteins, Nej1/Lif2 and Ntr1/Spp382, which play a role in restricting the activity of Dnl4-Lif1, the complex that executes the final ligation step of this process.

Keywords: Non-homologous end-joining, Ligase complex, Saccharomyces cerevisiae

Since DNA double-strand breaks (DSBs) are the most serious type of DNA damage, their repair is essential for maintaining genome stability and cell viability. Cells have evolved two major pathways for repairing DSB, homologous recombination (HR) and non-homologous end-joining (NHEJ). NHEJ was discovered in mammals, where it represents the main DSB repair pathway. The core mammalian NHEJ factors are the DNA-dependent protein kinase (DNA-PK), consisting of the catalytic subunit (DNA-PKcs) and the two DNA end-binding components (KU70 and KU80), and the DNA ligase IV-XRCC4 complex in association with the recently identified CERNUNNOS/XLF protein (referred to hereafter as XLF) (reviewed in [1] and Refs. [2,3]). In contrast to mammals, the budding yeast S. cerevisiae repairs DSBs primarily by HR, despite the presence of the KU70, KU80, DNA ligase IV, XRCC4 and XLF homologues in this organism, designated Yku70, Yku80, Dnl4, Lif1 and Nej1/Lif2 (referred to hereafter as Nej1), respectively. Although S. cerevisiae lacks a homologue of DNA-PKcs, this organism additionally requires the Mre11-Rad50-Xrs2 complex for NHEJ, which does not appear to be the case in mammals (for reviews, see [4,5]).

The final step of the NHEJ process is carried out by the ligase complex. If activity of this complex is impaired, NHEJ rejoins DSBs with lower frequency and fidelity, a consequence of which is genome instability and in some cases cancer onset in multicellular organisms. Importantly, not only chromosome-internal DSB, but also chromosome ends with dysfunctional telomeres are joined by this complex [6]. The latter process gives rise to end-to-end chromosome fusions, and hence to dicentric chromosomes. Breakage of these chromosomes results in nonreciprocal translocations that are evident in most cancer cells. These observations indicate a need to precisely control the ligation step of NHEJ and to restrict the activity of the ligase complex under certain circumstances. Here, we review evidence that two proteins help achieve this in S. cerevisiae – one primarily globally, Nej1, the other locally, Ntr1/Spp382 (referred to hereafter as Ntr1).

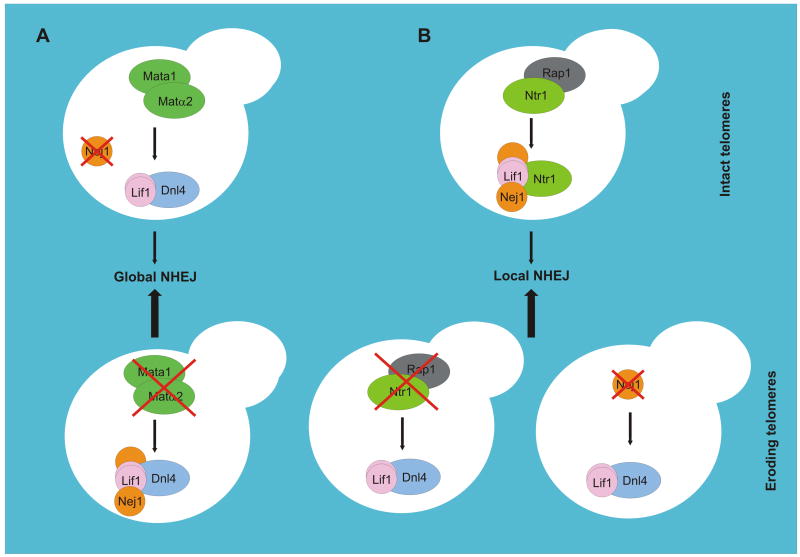

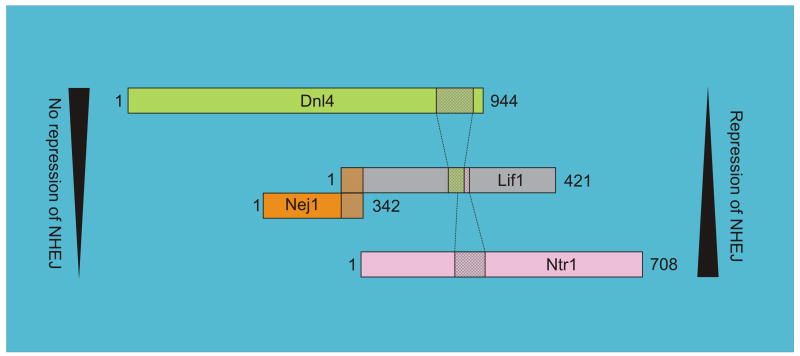

A first indication that NHEJ is under active control in S. cerevisiae appeared in the late 1990s when it was demonstrated that this process is down-regulated by Mata1-Matα2, resulting in less efficient NHEJ in diploid cells compared to haploid cells [7,8]. Subsequently, the responsible target protein, Nej1, was identified [9–12] and shown to be encoded by a haploid-specific gene, expression of which is virtually undetectable in the presence of Mata1-Matα2 because of a consensus-binding site for this repressor in the NEJ1 promoter [9,10]. Since Nej1 interacts with the Dnl4-Lif1 complex [9–12], the ligation step of NHEJ was proposed to be transcriptionally down-regulated in diploid yeast cells (Fig. 1A), in which HR is the preferred DSB repair pathway due to the ready availability of homologous chromosome donors. Interaction of Nej1 with the ligase complex is mediated mainly through Lif1, specifically by the C- (residues 272–342) and N- (residues 2–69) termini of Nej1 and Lif1, respectively (Fig. 2) [11,12]. As a result of this interaction, Nej1 was suggested to promote Dnl4-Lif1 import into nucleus [9], although this requires re-examination, as others did not observe defective nuclear or chromatin localization of Lif1 in nej1 mutants [10,13]. It would thus appear that Nej1 stimulation of NHEJ is more direct, but little is known about the mechanism of this effect. A hint came with the prediction that Nej1 and Lif1 fold similarly, with N-terminal globular head and internal coiled-coil domains [14]. This suggested that Nej1 might regulate the ligase complex by binding to Dnl4 through its coiled-coil in a manner analogous to Lif1 [15,16], presumably replacing Lif1 in the Dnl4 complex. This concept has not found support in recent interaction studies [17], but importantly such a switch might be dependent on the chromatin or DSB context. Neither DSB chromatin immunoprecipitation nor in vitro NHEJ reconstitution have yet been reported with attention to the role of Nej1 and will be important to resolving these issues.

Fig. 1.

Ways of restricting the activity of the ligase complex in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. (A) A global way. In diploid cells, the Mata1-Matα2 repressor binds to promoter region of the NEJ1 gene. Consequently, in these cells NEJ1 is not transcribed and the Nej1 protein is entirely absent. In contrast, haploid cells contain Nej1 due to unrepressed NEJ1 expression, where it interacts with the ligase complex and enhances NHEJ efficiency. This net effect is lower NHEJ efficiency in diploid compared to haploid cells. (B) A local way. The Ntr1 protein deposited at telomeres, possibly via its association with Rap1, assembles with Lif1 and disrupts the ligase complex, creating putative Ntr1-Lif1 and Ntr1-Lif1-Nej1 complexes as an outcome (only the situation in a haploid cell is shown). This process may lead to local inhibition of the ligation step of NHEJ at telomeres. In contrast, if Ntr1 does not or cannot interact with Lif1, for example due to decreased Rap1 binding, fully active ligase complex is retained. Such complex can support NHEJ at telomeres leading to unwanted end-to-end chromosomal fusions. In addition, at eroding telomeres Nej1 suppresses NHEJ by a mechanism which is not clearly understood yet. Therefore, if this protein is missing, eroded chromosome ends are fused in a Dnl4-dependent manner. Presumably, a novel, yet unidentified, role of Nej1 drives action of this protein in opposing direction compared to its role in canonical NHEJ. For references, see text.

Fig. 2.

Interacting domains within the ligase complex in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Dnl4- and Ntr1-interacting domains in Lif1 map to the regions 205–228 and 220–240, respectively, indicating a competition between Dnl4 and Ntr1 for the binding site in Lif1. The drawings are not to scale and are shown in a haploid cell. For details and references, see text.

Recently, Nej1 has been shown to be phosphorylated in response to DNA damage [13], pointing to a further potential mode of regulation of the Dnl4-Lif1 activity by this protein via its post-translational modification. But what does this regulation do? The mild NHEJ phenotype of cells unable to support Nej1 phosphorylation suggests that this regulation is not strictly required for NHEJ, at least in a plasmid-based simple religation assay. However, it might be that other DNA end structures, such as those requiring additional reactions prior to ligation, or chromosomal DSB may raise demand for phosphorylated Nej1. Since the main phosphorylation sites in Nej1, serines 297 and 298, seem to lie within the Lif1-interacting region (Fig. 2), Ahnesorg and Jackson suggested that phosphorylation represents a control mechanism affecting the Lif1-Nej1 interaction [13], which might be expected to release Nej1 from the ligase complex. Another possibility is that phosphorylation does not alter the Lif1-Nej1 interaction and that phosphorylated Nej1 instead alters the function of the ligase complex. Whatever is the case, the biological consequence of Nej1 phosphorylation remains unclear and needs to be elucidated. A speculative hypothesis is that phosphorylated Nej1, either alone or in complex with Lif1, might interact with a novel partner. Nej1 together with this partner could acquire a novel, yet unidentified, role, which may extend action of this protein beyond NHEJ. This is exactly what may happen at telomeres where Nej1 was shown to protect chromosomes from Dnl4-dependent end-to-end fusions under telomere erosion conditions [18], thereby paradoxically suppressing NHEJ in this context while promoting it in others. In this respect, it would be interesting to know whether telomere attrition represents a signal leading to Nej1 phosphorylation and whether yeast incapable of Nej1 phosphorylation display increased telomeres fusion events. In summary, Nej1 appears to provide several potentially overlapping modes of control over the final ligation step during NHEJ, including its regulated expression, phosphorylation, direct stimulation of repair, and context-dependent effects.

For a long time, database searches failed to reveal Nej1 homologues outside of the Saccharomyces yeasts. However, Nej1 homologues were recently found in a number of other organisms including humans, where it is known as XLF [2,15,16]. Nej1 and XLF are highly divergent in primary sequence, which may be because both genes have evolved under positive selection leading to disproportionate retention of DNA changes that alter the encoded amino acids [19,20], but are predicted to adopt a similar tertiary structure. In vitro, XLF has a DNA binding activity, reinforcing a function of this protein in directly stimulating the ligase activity of DNA ligase IV-XRCC4 [16,21]. Interestingly, XLF has only a weak effect on joining of cohesive DNA ends, but strongly promotes the ligation of blunt, less cohesive and mismatched DNA ends [22]. Although Nej1 is expected to have a mechanistic function analogous to XLF, its specificity for various DNA end structures may differ because XLF has a particularly important role in NHEJ of 3′ overhangs during V(D)J recombination of the immunoglobulin genes [22], a process strictly restricted to lymphocytes.

Recently, Herrmann et al. discovered another Lif1-interacting partner, Ntr1 [23], an essential protein that functions in the spliceosome disassembly process [24]. Interestingly, the region in Lif1 responsible for interaction with Ntr1 (residues 220–240) overlaps to a large extent with the region involved in binding to Dnl4 (residues 205–228) [25], indicating that Ntr1 competes with Dnl4 for binding to Lif1 (Fig. 2). Outstanding questions are why a cell might need to channel Ntr1 into complex with Lif1 and where this might happen. Given that Ntr1 was demonstrated to co-localize with telomere-associated proteins, it is reasonable to suggest that this protein functions to disrupt the ligase complex at telomeres, causing the down-regulation of NHEJ at these chromosomal regions [23]. But what happens if Ntr1 cannot interact with Lif1 and how this may occur? As reported, one of the telomere-associated proteins co-localizing with Ntr1 is Rap1 [23]. Rap1 directly binds the telomeres and the amount bound increases with number of telomeric repeats. Once bound it in part recruits other factors to chromosome ends, assigning their roles in telomere metabolism. Interestingly, Rap1 loss results in NHEJ-dependent chromosome end-to-end fusions in yeasts [26] and humans [27], though the mechanism underlying NHEJ suppression by Rap1 is not clearly understood yet. Notably, apart from the ligase complex, all other core NHEJ factors in S. cerevisiae are constitutively bound to telomeres, where they help maintain telomere repeat lengths, gene silencing and other functions. For this reason, ligation seems to be the best step for regulating NHEJ at telomeres without also impacting other processes. We speculate that Rap1 may also serve to deposit Ntr1 at chromosome ends. Once there, Ntr1 may locally sequester Lif1 in an inactive complex, thereby suppressing NHEJ-dependent ligation in its close proximity. Upon telomere attrition, when the number of Rap1 molecules bound to the telomeres decreases, local availability of Ntr1 can be severely reduced, leading to de-repression of NHEJ (Fig. 1B).

In summary, control over the activity of the NHEJ ligase complex at telomeres appears to be at least two-fold – one restriction imposed by Nej1 at telomeres that are undergoing a process of shortening, the other through Ntr1 at intact telomeres. Both controls serve to suppress NHEJ at these chromosomal regions, thereby protecting them from unwanted fusions. It will be of considerable interest to continue to test these hypotheses, establish the associated mechanisms, and explore the degree to which they are inter-dependent or synergistic in NHEJ regulation.

Acknowledgments

Research in the MC and TEW laboratory is supported by the Slovak Research and Development Agency (contract No. APVV-51-042705) and the National Institutes of Health (CA102563), respectively.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Hefferin ML, Tomkinson AE. Mechanism of DNA double-strand break repair by non-homologous end joining. DNA Repair (Amst) 2005;4:639–648. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2004.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Buck D, Malivert L, de Chasseval R, Barraud A, Fondaneche MC, Sanal O, Plebani A, Stephan JL, Hufnagel M, Le Deist F, Fischer A, Durandy A, de Villartay JP, Revy P. Cernunnos, a novel nonhomologous end-joining factor, is mutated in human immunodeficiency with microcephaly. Cell. 2006;124:287–299. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.12.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ahnesorg P, Smith P, Jackson SP. XLF interacts with the XRCC4-DNA ligase IV complex to promote DNA nonhomologous end-joining. Cell. 2006;124:301–313. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.12.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dudášová Z, Dudáš A, Chovanec M. Non-homologous end-joining factors of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2004;28:581–601. doi: 10.1016/j.femsre.2004.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Daley JM, Palmbos PL, Wu D, Wilson TE. Nonhomologous end joining in yeast. Annu Rev Genet. 2005;39:431–451. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.39.073003.113340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Smogorzewska A, Karlseder J, Holtgreve-Grez H, Jauch A, de Lange T. DNA ligase IV-dependent NHEJ of deprotected mammalian telomeres in G1 and G2. Curr Biol. 2002;12:1635–1644. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(02)01179-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Åström SU, Okamura SM, Rine J. Yeast cell-type regulation of DNA repair. Nature. 1999;397:310. doi: 10.1038/16833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee SE, Pâques F, Sylvan J, Haber JE. Role of yeast SIR genes and mating type in directing DNA double-strand breaks to homologous and non-homologous repair paths. Curr Biol. 1999;9:767–770. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(99)80339-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Valencia M, Bentele M, Vaze MB, Herrmann G, Kraus E, Lee SE, Schär P, Haber JE. NEJ1 controls non-homologous end joining in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Nature. 2001;414:666–669. doi: 10.1038/414666a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kegel A, Sjöstrand JOO, Åström SU. Nej1p, a cell type-specific regulator of nonhomologous end joining in yeast. Curr Biol. 2001;11:1611–1617. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(01)00488-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ooi SL, Shoemaker DD, Boeke JD. A DNA microarray-based genetic screen for nonhomologous end-joining mutants in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Science. 2001;294:2552–2556. doi: 10.1126/science.1065672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Frank-Vaillant M, Marcand S. NHEJ regulation by mating type is exercised through a novel protein, Lif2p, essential to the ligase IV pathway. Genes Dev. 2001;15:3005–3012. doi: 10.1101/gad.206801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ahnesorg P, Jackson SP. The non-homologous end-joining protein Nej1p is a target of the DNA damage checkpoint. DNA Repair (Amst) 2007;6:190–201. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2006.09.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gromiha MM, Parry DA. Characteristic features of amino acid residues in coiled-coil protein structures. Biophys Chem. 2004;111:95–103. doi: 10.1016/j.bpc.2004.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Callebaut I, Malivert L, Fischer A, Mornon JP, Revy P, de Villartay JP. Cernunnos interacts with the XRCC4/DNA ligase IV complex and is homologous to the yeast nonhomologous end-joining factor Nej1. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:13857–13860. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C500473200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hentges P, Ahnesorg P, Pitcher RS, Bruce CK, Kysela B, Green AJ, Bianchi J, Wilson TE, Jackson SP, Doherty AJ. Evolutionary and functional conservation of the DNA non-homologous end-joining protein, XLF/CERNUNNOS. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:37517–37526. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M608727200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Deshpande RA, Wilson TE. Modes of interaction among yeast Nej1, Lif1 and Dnl4 proteins and comparison to human XLF, XRCC4 and Lig4. DNA Repair. 2007 doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2007.04.014. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liti G, Louis EJ. NEJ1 prevents NHEJ-dependent telomere fusions in yeast without telomerase. Mol Cell. 2003;11:1373–1378. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00177-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sawyer SL, Malik HS. Positive selection of yeast nonhomologous end-joining genes and a retrotransposon conflict hypothesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:17614–17619. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0605468103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pavlicek A, Jurka J. Positive selection on the nonhomologous end-joining factor Cernunnos-XLF in the human lineage. Biol Direct. 2006;1:15. doi: 10.1186/1745-6150-1-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lu H, Pannicke U, Schwarz K, Lieber MR. Length-dependent binding of human XLF to DNA and stimulation of XRCC4:DNA ligase IV activity. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:11155–11162. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M609904200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tsai CJ, Kim SA, Chu G. Cernunnos/XLF promotes the ligation of mismatched and noncohesive DNA ends. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:7851–7856. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0702620104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Herrmann G, Kais S, Hoffbauer J, Shah-Hosseini K, Bruggenolte N, Schober H, Fasi M, Schär P. Conserved interactions of the splicing factor Ntr1/Spp382 with proteins involved in DNA double-strand break repair and telomere metabolism. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:2321–2332. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tsai RT, Fu RH, Yeh FL, Tseng CK, Lin YC, Huang YH, Cheng SC. Spliceosome disassembly catalyzed by Prp43 and its associated components Ntr1 and Ntr2. Genes Dev. 2005;19:2991–3003. doi: 10.1101/gad.1377405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dore AS, Furnham N, Davies OR, Sibanda BL, Chirgadze DY, Jackson SP, Pellegrini L, Blundell TL. Structure of an Xrcc4-DNA ligase IV yeast ortholog complex reveals a novel BRCT interaction mode. DNA Repair (Amst) 2006;5:362–368. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2005.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pardo B, Marcand S. Rap1 prevents telomere fusions by nonhomologous end joining. EMBO J. 2005;24:3117–3127. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bae NS, Baumann P. A RAP1/TRF2 complex inhibits nonhomologous end-joining at human telomeric DNA ends. Mol Cell. 2007;26:323–334. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.03.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]