Abstract

In this study we examined cognitive features that have been posited to contribute to depressive vulnerability in adolescents. Using a longitudinal sample of 331 young adolescents followed from 6th to 7th grade, cross-lagged structural equation analyses were conducted. Controlling for baseline levels of depressive, conduct, and anxiety symptoms, low self-worth was associated with a vulnerability to both depressive symptoms and conduct problems, whereas rejection sensitivity was uniquely predictive of increases in anxiety. In support of cognitive “scar” models, baseline depressive and conduct problems were both predictive of a more negative attributional style. Depressive symptoms also predicted more rejection sensitivity, whereas conduct problems predicted lower self-esteem.

Cognitive models of depression emphasize the role of negative cognitions or maladaptive belief systems as diatheses in the initiation and continuation of depressive symptomatology. Two of the central theories that have received considerable empirical support in adult populations are hopelessness theory and Beck’s (1967) cognitive theory (Abramson et al., 2002; Ingram, Miranda, & Segal, 1998). Hopelessness theory proposes that individuals who attribute negative life events to global and stable causes, who perceive disastrous consequences from such events, and who infer negative characteristics about the self are vulnerable to depression when confronted with negative life experiences (Abela & Sarin, 2002; Abramson, Alloy, & Metalsky, 1988). Similarly, Beck’s cognitive model proposes that negative views of the self, the world, and the future—the negative cognitive triad—serve as a proximal cause for depression in the face of negative life events.

Cognitive theories have recently been expanded to the interpersonal domain by considering not only thoughts about oneself but also representations of others and the self in interactions with others (Abela et al., 2005; Hammen, 1992). Cognitive–interpersonal theories of depression suggest that persons with depression or prone to depression are likely to seek negative information about themselves, to believe they are unworthy of positive social attention, and to enter interpersonal situations with pessimistic expectations (Rudolph & Clark, 2001). One classic framework for explaining risk for depression, incorporating cognitive interpretation with relational experiences, is the interactional view of depression put forth by Coyne (1976), in which excessive reassurance-seeking coupled with rejection by others results in an increasingly negative interpersonal experience and greater depression.

Generally, strong support has emerged for the cognitive diathesis for depression among children and adolescents. Negative attributional style and low self-worth have been found to be associated with depressive symptoms and clinical depression across age, gender, and sample type (Abramson et al., 2002; Harter & Whitesell, 1996; Mezulis, Abrahamson, Hyde, & Hankin, 2004). In line with cognitive interpersonal theories, the diathesis extends to interpersonal areas, as young adolescents with depressive symptoms hold more negative interpersonal expectancies (Rudolph & Clark, 2001; Rudolph, Hammen, & Burge, 1997), have maladaptive relationship-oriented beliefs and more negative conceptions of peer relationships (Hammen et al., 1995; Rudolph & Clark, 2001), and process and view interactions more negatively (Shirk, Van Horn, & Leber, 1997). Thus, negative views of the self, events, and expectations of interactions with others have all been associated with depressive symptoms.

Directionality of the Association Between Cognitive Style and Psychopathology

In most theoretical discussions, including hopelessness theory and Beck’s (1967) cognitive theory, cognitive features have been conceptualized as a diathesis for depression (Shahar, Blatt, Zuroff, Kuperminc, & Leadbeater, 2004). This cognitive vulnerability hypothesis posits that the presence of certain cognitive features (e.g., low self-esteem, negative attributional style) predisposes individuals to a higher vulnerability for later depression or adjustment problems when the individual is exposed to stressful circumstances. Although some studies have found that cognitive features predict future depressive symptoms, others have revealed influences of depression on subsequent cognitions, such as attributional style and social perceptions (Kistner, David-Ferdon, Repper, & Joiner, 2006; Nolen-Hoeksema, Girgus, & Seligman, 1992; Rohde, Lewinsohn, & Seeley, 1990). It is possible that experiencing a depressive episode or a period of depressive symptoms can lead individuals to develop a more pessimistic explanatory style or to be more sensitive to rejection, features that remain after the depression subsides. Similarly, the presence of elevated depressive symptoms can lead to future underestimations of competence (Cole, Martin, Peeke, Seroczynski, & Hoffman, 1998; McGrath & Repetti, 2002). In line with these findings, the cognitive scar hypothesis posits that the experience of depression influences later cognitions. Although these two hypotheses have frequently been pitted against each other, it is quite possible that both are true and that there is a reciprocal or bidirectional relation (Gibb & Alloy, 2006).

Specificity of Cognitive Vulnerability for Depression

Among adolescents, conduct problems and anxiety commonly co-occur with depression (Angold & Costello, 1993; Angold, Costello, & Erkanli, 1999). Because of the high likelihood of comorbidity, it is unclear whether cognitive features are in fact specific to the development of depression or are related more broadly to the general development of psychopathology. The degree to which cognitive features are unique to depression has implications both for theories of etiology and for treatment. To the extent that cognitive vulnerabilities are shared between disorders, this may suggest a “core process” for the development of psychopathology and a common focus for treatment of different types of disorders.

Cognitive and cognitive–interpersonal models were proposed originally as etiological theories of depression (Hankin & Abramson, 2001), and very little research has been conducted examining cognitive features as risk factors for forms of psychopathology other than depression. According to a meta-analytic review of this area, only a small number of studies have tested cognitive theories of depression with children or adolescents while simultaneously measuring other symptoms or disorders to examine specificity, and the findings have been mixed (Joiner & Wagner, 1995). Many of the extant studies are further limited by the use of a cross-sectional design and small clinical samples.

In accordance with the notion that cognitive features create specific risk for depression, some studies have shown that children with high levels of self-reported depression have a more depressogenic attributional style compared to children with high levels of aggression (Quiggle, Garber, Panak, & Dodge, 1992) or conduct problems (Robinson, Garber, & Hilsman, 1995). Similarly, among clinical samples some studies have found differences in cognitive style between youth with depression diagnoses compared to those with other diagnoses (Kaslow, Rehm, Pollock, & Siegel, 1988; McCauley, Mitchell, Burke, & Moss, 1988). There also appears to be some specificity of automatic thought content depending on symptomatology, with thoughts of personal failure associated with depression and thoughts of hostility associated with externalizing symptoms (Schniering & Rapee, 2004). As for cognition in the interpersonal context, there is evidence that children with depressive symptoms have more negative conceptions of their social status than do aggressive children (Rudolph, Lambert, Clark, & Kurlakowsky, 2001) and are more likely to seek negative feedback, a trait that is specific to depression as opposed to anxiety (Joiner & Wagner, 1995). In a high school sample found that adolescents with a current depressive diagnosis did not differ from adolescents with a current disorder other than depression on their attributional style (Gotlib, Lewinsohn, Seeley, Rohde, & Redner, 1993). Furthermore, there has been some debate about the extent to which low perceived self-worth is related to depression versus conduct problems (Donnellan, Trzesniewski, Robins, Moffitt, & Caspi, 2005; Robinson et al., 1995). Social information processing biases, such as hostile attribution bias, are frequently associated with youth aggressive behavior (Coie & Dodge, 1998; Crick & Dodge, 1994).

Developmental Framework and This Study

The entry into adolescence is associated with general declines in self-esteem and competence beliefs as well with increased in risk of depression and externalizing disorders (Fenzel, 2000; Hankin et al., 1998; Wigfield & Eccles, 1994). Furthermore, as children enter adolescence, attributional style and competence beliefs become more stable and appear to play a stronger role in the development of depressive symptoms (Abela, 2001; Nolen-Hoeksema et al., 1992; Turner & Cole, 1994). During the transition to adolescence, children begin to understand that ability is a stable trait and to infer that repeated failures may represent a lack of ability (Mezulis et al., 2004; Stipek & MacIver, 1989). Thus, cognitive features may become especially salient as children near the transition to adolescence and become more discerning in their cognitive appraisals.

This study addresses two research questions that remain controversial in the cognitive literature: (a) To what extent do cognitive features have a bidirectional relation with youth psychopathology? (b) Are cognitive vulnerabilities associated specifically with adolescent depressive symptoms, or are they associated with conduct and anxiety problems as well? The cognitive features assessed include core elements from hopelessness theory, Beck’s 1967 cognitive theory, and interactional theories of depression: attributional style, beliefs about the self (self-worth), and rejection sensitivity. We hypothesized that influences between cognitive style and psychopathology would emerge in both directions and that cognitive vulnerability would be uniquely associated with depression. Structural models that explicitly model the natural co-occurrence among depression, anxiety, and conduct problems among adolescents were used to simultaneously examine the discriminant validity of cognitive features as they related to each type of psychopathology.

Method

Participants

This study was carried out as part of the Developmental Pathways Program, a community-based longitudinal study of the development of depression and co-occurring conduct problems in young adolescents, which was approved by the University of Washington Institutional Review Board. The project was conducted in two phases, beginning with depression and conduct problem screening of sixth-grade students in four Seattle public middle schools over a period of four successive school years (2001 to 2005). The 2,187 students who were screened (71% of enrolled sixth graders) were stratified into four psychopathology subgroups based on their screening scale scores. The comorbid group had mean scores on both depression and disruptive behavior dimensions of greater than .5 SD above the sample mean. The depressed group had an elevation .5 SD above the mean on the depression dimension only. The conduct disorder group had elevated conduct problem scores (.5 SD) only. The neither group had scores below .5 SD higher than the sample mean on both dimensions. Longitudinal study participants were randomly selected from the four psychopathology subgroups in the ratio of 1 comorbid: 1 depressed: 1 conduct disorder: 2 neither. The longitudinal sample was comprised of 521 children and a parent or guardian (65% of selected). All analyses were conducted using sampling weights that make the longitudinal sample comparable to the school population on depressive and conduct problems, gender, race, ethnicity, and educational program.

This study utilized a subsample of the longitudinal sample (n = 331), including those from the first three of four cohorts who had been administered each of the relevant cognitive and psychopathology measures. Use of the weighting procedures ensured that participants were representative of the larger school population. Of participating parent and guardians, 80% were biological or adoptive mothers, 15% were biological or adoptive fathers, and 5% were other adult guardians. Racial background of the participating children was 23.3% African American, 17.9% Asian or Pacific Islander, 3.3% Native American, and 56.2% European American, with 9% of the sample reporting Hispanic ethnicity. The sample included 156 girls and 175 boys, with a mean age of 12.0 (SD = .41). Family income for the sample was reported to be less than $35,000 for 28.1% of participants, between $35,000 and $75,000 for 35.9% of participants, and above $75,000 for 36.0% of participants. The highest level of education achieved by the primary caregiver in these families was high school or less (15.4%), some college (22.1%), associate’s or bachelor’s degree (33.9%), and advanced degree (28.6%).

Measures

Depressive symptoms

The Mood and Feelings Questionnaire is a self-report measure of depression designed for children ages 8 to 18. This questionnaire has 33 items that comprise both the full range of Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (3rd ed., revised; American Psychiatric Association, 1987) diagnostic criteria for depressive disorders, as well as additional items reflecting common affective, cognitive, and vegetative features of childhood depression (Costello & Angold, 1988). Previous validation studies have demonstrated high content and criterion validity, showing concordance with depressive diagnoses derived from standardized diagnostic interviews (Wood, Kroll, Moore, & Harrington, 1995). Using the Kiddie Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Aged Children major depression diagnosis as criterion, moderate discriminant validity (area under the curve = .82, area under the curve = .77) was demonstrated for the child version of the Mood and Feelings Questionnaire (Kent, Vostanis, & Feehan, 1997; Wood et al., 1995). Cronbach’s alpha coefficients for the Mood and Feelings Questionnaire in this sample were .90, (Time 1) and .89 (Time 2).

Conduct problems

The Child Behavior Checklist (Achenbach, 1991) has been used extensively in child psychiatric epidemiological studies to identify subgroups of children within the general population who are at risk of having psychiatric conditions (e.g., Pittsburgh Youth Study, Loeber et al., 1993; Great Smoky Mountains Study, Costello et al., 1996). The revised Child Behavior Checklist is a well-standardized measure with excellent reliability and validity. In evaluations of discriminant validity, the Child Behavior Checklistsyndrome subscales have correctly classified on average 80% of children as referred versus nonreferred, (Achenbach & Rescorla, 2001). The 1991 version of the externalizing scale, comprising 30 items, was used in this study (αs = .88 and .87, respectively).

Anxiety problems

We administered the Multidimensional Anxiety Scale for Children (March & MHS Staff, 1997), a 39-item self-report scale comprised of items that describe physical symptoms of anxiety, social anxiety, harm avoidance behavior, and separation anxiety. This scale has been standardized for children in 3rd through 12th grades. Internal validity and test–retest reliability have both been reported as excellent. A discriminant function analysis of the Total Anxiety Scale had 90% sensitivity and 84% specificity with a kappa of .74 to predict anxiety disorders made by clinicians (March & MHS Staff, 1997).

Attributional style

The Children’s Attributional Style Questionnaire–Revised is a 24-item scale that asks children to imagine they have encountered various hypothetical situations and has children choose between two explanations for why each situation would have happened to them (Thompson, Kaslow, Weiss, & Nolen-Hoeksema, 1998). The scale is designed to assess the child’s attributions for both positive and negative events, with higher scores reflective of more internal, stable, or global attributions (considered optimistic for positive events but pessimistic for negative events). We utilized attributional style for negative events only, as this has been generally conceptualized as the diathesis for onset of depression. The internal consistency for the negative scale is reported to be moderate (αs = .45 to .46) and test–retest reliability fair (r = .38) for 9- to 12-year-old African American and White girls and boys (Thompson et al., 1998). The Children’s Attributional Style Questionnaire–Revised has demonstrated good criterion-related validity with self-reported depressive symptoms. In this sample, Cronbach’s alpha coefficients for negative attributional style were .36 (Time 1) and .45 (Time 2).

Self-worth

The Self-Perception Profile for Children (Harter, 1985) was used to assess children’s report of their self-worth. Items involve structured alternatives (e.g., “Some kids like the kind of person they are” but “Other kids often wish they were someone else”). Children first choose which alternative is more true of them and then rate how true that alternative is for them. Three-month and 9-month test–retest reliabilities of .69 to .87 have been reported for third to ninth graders (Harter, 1982). The Global Self-Worth scale was used, reflecting the extent to which the child likes himself or herself as a person globally. Cronbach’s alpha for self-worth in this sample was .83 (at both time points). Higher scores are reflective of greater perceived self-worth.

Rejection sensitivity

The Children’s Rejection Sensitivity Questionnaire (Downey, Lebolt, Rincon, & Freitas, 1998) scale consists of 12 hypothetical social situations for which the child rates the extent to which he or she would anxiously expect rejection. For example, children are asked to imagine that they “had a really bad fight the other day with a friend” and then rate whether the friend would want to talk to them and listen to their problem. We utilized the Anxious Expectation of Rejection subscale, which combines their rating of how nervous they would feel and the extent to which they would expect rejection, with higher scores reflecting more rejection sensitivity. The scale has previously demonstrated good test–retest reliability (4-week r = .85 to .90) and internal consistency (αs = .72 to .84) among children in the fifth through seventh grades from minority ethnic groups. The scale has also demonstrated good criterion validity, correlating highly with other self-report measures of social cognition. Cronbach’s alpha for the anxious rejection sensitivity scale in this sample was .80 (Time 1) and .85 (Time 2).

Procedures

In Phase I of the study, students who had parental permission and who gave their written assent completed the screening questionnaire, administered in classrooms by study staff during one 50-min class period. Participants whose screening scores indicated a high level of emotional distress (16%) were seen for an individual follow-up evaluation; feedback was provided to the student, parents, and the school counselor. Written consent and assent were again obtained from parents and youth for their participation in Phase II, the longitudinal study. In Phase II participating students and a parent or guardian were interviewed separately by two research interviewers and administered each of the study measures, in private locations in family homes or other locations that were convenient to the family. Interviewers clarified the instructions and ensured that participants completed each measure thoroughly. Baseline (Time 1) interviews were conducted in sixth grade approximately 3 months after screening with a follow-up (Time 2) interview conducted 1 year later, when students were in the seventh grade.

Results

Paired t tests were conducted to examine change in each of the study variables from Time 1 to Time 2. As shown in Table 1, each of the changes was significant. Adolescents had higher self-worth, less negative attributional style, and less rejection sensitivity at the beginning of seventh grade as compared to the beginning of sixth grade. Moreover, there were overall decreases in depressive, conduct, and anxiety symptoms over the course of the year.

Table 1.

Means and Standard Deviations

| Time 1

|

Time 2

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | M | SD | M | SD | t Test (df) |

| Self-worth | 3.26 | .64 | 3.37 | .57 | 3.53* |

| Anxious rejection sensitivity | 9.50 | 4.27 | 7.56 | 3.88 | 10.14* |

| Negative attributional style | .22 | .14 | .19 | .14 | 3.24* |

| Depressive symptoms | 9.66 | 8.19 | 7.62 | 7.20 | 5.21* |

| Conduct symptoms | 7.56 | 6.63 | 6.40 | 5.98 | 4.59* |

| Anxiety symptoms | 43.49 | 16.05 | 38.27 | 15.09 | 6.42* |

p < .01.

Methods for Model Testing

Structural equation modeling was used to examine the relations among three cognitive features (attributional style for negative events, self-worth, and rejection sensitivity) and symptoms of depression, conduct problems, and anxiety. Structural equation modeling has been suggested as the procedure of choice when examining cross-lagged effects (Hays, Marshall, Wang, & Sherbourne, 1994). Clustering of students within schools was taken into account for all analyses.

Structural equation modeling models were specified, estimated, and evaluated using MPlus software (Version 3.13; Muthén & Muthén, 1998). Correlations among variables are shown in Table 2. All models included stability coefficients between baseline (Time 1) and 1-year follow-up (Time 2) for each measure, synchronous relation between variables measured at the same time, both in the form of intercorrelations between variables at Time 1 and correlations between residuals at Time 2, and cross-lagged effects from cognitive features to youth psychopathology. We included the chi-square likelihood ratio test statistic as one measure of goodness of fit of the models. However, because it is sensitive to minor departures from multivariate normality and is affected by sample size (Bollen, 1989), we also provided two other commonly used indexes of fit—the Comparative Fit Index and the root mean square error of approximation. For the Comparative Fit Index, values equal to or greater than .95 are typically used to indicate good model fit (Hu & Bentler, 1999). For the root mean square error of approximation, values ranging from .03 to .08 indicate good model fit. Chi-square difference tests were used to compare nested models, evaluating improvement of fit. A significant difference in chi-square indicates that the model with the lower chi-square value (the less restrictive model) is superior.

Table 2.

Correlations Among Variables

| 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time 1 | |||||||||||

| 1. Self-worth | −44 | −.36 | −.60 | −.21 | −.37 | .56 | −.47 | −.29 | −.48 | −.22 | −.24 |

| 2. Anxious rejection sensitivity | .23 | .35 | .10 | .41 | −.33 | .64 | .11 | .30 | .11 | .31 | |

| 3. Negative attributional style | .31 | .22 | .18 | −.20 | .23 | .40 | .27 | .20 | .07 | ||

| 4. Depressive symptoms | .19 | .47 | −.38 | .38 | .25 | .58 | .22 | .25 | |||

| 5. Conduct symptoms | .00 | −.19 | .15 | .19 | .17 | .71 | −.02 | ||||

| 6. Anxiety symptoms | −.28 | .33 | .13 | .33 | .04 | .55 | |||||

| Time 2 | |||||||||||

| 7. Self-worth | −.42 | −.27 | −.58 | −.26 | −.32 | ||||||

| 8. Anxious rejection sensitivity | .30 | .45 | .21 | .41 | |||||||

| 9. Negative attributional style | .36 | .23 | .16 | ||||||||

| 10. Depressive symptoms | .27 | .41 | |||||||||

| 11. Conduct symptoms | .07 | ||||||||||

| 12. Anxiety symptoms | |||||||||||

Note: All correlations greater than .11 are significant p < .05; correlations greater than .15 are significant p < .01.

Directionality

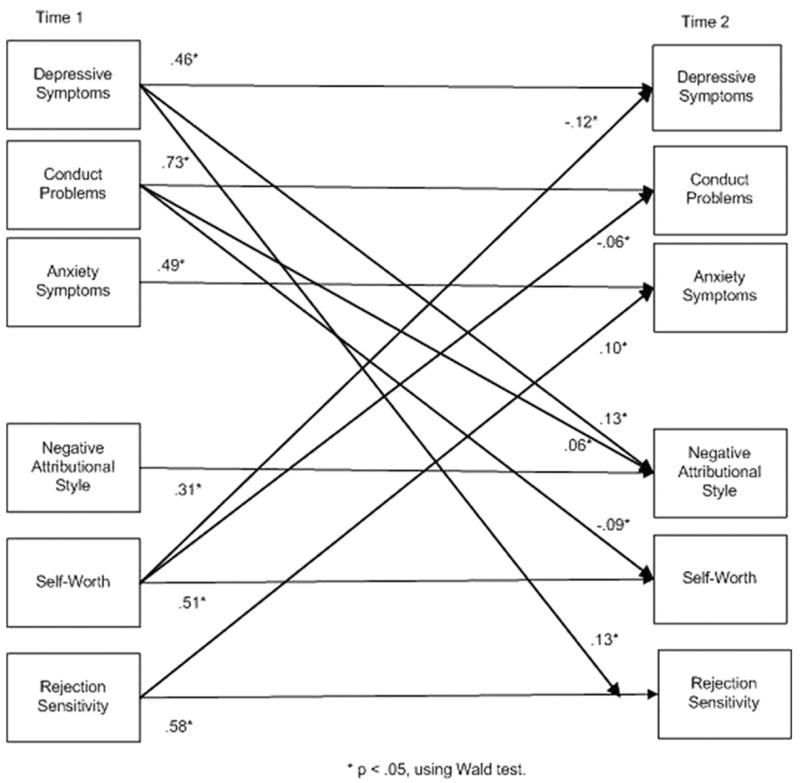

The cognitive vulnerability model was empirically compared to a bidirectional effects model that incorporated the paths from Time 1 psychopathology, including depressive symptoms, conduct problems, and anxiety symptoms, to Time 2 cognitive features using the chi-square difference test. Although both models demonstrated relatively good fit using the index criteria (see Table 3), the chi-square value for the bidirectional effects model was significantly lower (indicating better fit) than the chi-square for the cognitive vulnerability model, Satorra–Bentler adjusted Δχ2 (9) = 22.91, p = .006. Significant pathways emerged showing both vulnerability and scar effects of the cognitive features examined. Cross-lagged effects generated by the model are shown in Figure 1, with nonsignificant paths represented as dashed lines and synchronous paths omitted from the figure for clarity.

Table 3.

Comparative Model Fit

| Model Type | χ2 (df) | p Value | CFI | RMSEA |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cognitive Vulnerability Model | 36.92 (21) | .02 | .98 | .05 |

| Bidirectional Effects Model | 16.45 (12)* | .17 | 1.00 | .03 |

| Psychopathology General Model | 37.87 (24) | .04 | .99 | .04 |

Note: CFI = Comparative fit index; RMSEA = root mean square error of approximation.

p < .05 for chi-square difference test.

Figure 1.

Results of the bidirectional effects model (psychopathology specific).

Two of the cognitive features were associated with change in adolescent psychopathology over time, providing evidence for cognitive vulnerability. Lower self-worth was associated with increases in depressive symptoms (β = −.12, p ≪ .01) and conduct problems (β = −.06, p ≪ .05), whereas rejection sensitivity was associated with increases in anxiety symptoms (β = .10, p ≪ .01). All three of the cognitive features also changed as a function of psychopathology, providing evidence for cognitive scarring. More depressive symptoms at Time 1 were related to a more negative attributional style (β = .13, p ≪ .01) and more rejection sensitivity (β = .13, p ≪ .01), at Time 2. Higher levels of conduct problems also predicted a more negative attributional style (β = .06, p ≪ .05) and lower self-worth (β = −.09, p ≪ .01) at Time 2.

Stability coefficients for all variables were generally moderate in magnitude (βs ranged from .31 to .73, as shown on the left in Figure 1), indicating that youth cognitive features and psychopathology were relatively consistent from Time 1 to Time 2 but that meaningful change occurred for some participants. The estimated R2 values at Time 2 were .35 (depression) .56 (conduct problems), and .27 (anxiety). Correlations among residuals, shown in Table 4, were small to moderate in magnitude. Thirteen of these correlations were statistically significant, indicating that a portion of the unaccounted variance among these variables is attributable to common omitted variables not specified in the model.

Table 4.

Correlations Among Residuals

| Time 2 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Self-worth | −14** | −.11 | −.27** | −.08* | −.17** |

| 2. Anxious rejection sensitivity | .21** | .15** | .07** | .19** | |

| 3. Negative attributional style | .18** | .07** | .13 | ||

| 4. Depressive symptoms | .09** | .26** | |||

| 5. Conduct symptoms | .09** |

p < .05.

p < .01.

Specificity of Cognitive Features to Depressive Symptoms

To test for the specificity of these cognitive features to depression, we compared the bidirectional effects model reported previously, in which the cognitive vulnerability and scar paths were allowed to differ for depressive, conduct, and anxious symptoms, to a psychopathology-general model that constrained each of the vulnerability and scar path coefficients for each cognitive feature to be equal for all three types of psychopathology. In our psychopathology-general model, the path coefficient predicting depressive symptoms from self-esteem was forced to be identical to the path coefficients predicting conduct problems and anxiety from self-esteem, and similar constraints were held for negative attributional style and rejection sensitivity, in both directions.

Table 4 shows the chi-square and fit indexes for the psychopathology-general model, as well as the bidirectional effects model (which allowed for differences between model pathways). Both of the models demonstrated good fit according to fit index criteria; however, using the chi-square difference test, we found that the psychopathology-specific model fit significantly better than the psychopathology-general model, suggesting some specificity of the cognitive features depending on type of psychopathology, Satorra–Bentler adjusted Δχ2(12) = 22.19, p = .03. Using Wald tests of significance as our criterion for whether path coefficients were specific or general, we found that the vulnerability created by rejection sensitivity was specific to anxiety, whereas low self-worth was associated with vulnerability for both depressive and conduct problems. In terms of cognitive repercussions of psychopathology, both depressive and conduct problems resulted in more negative attributional style. Depressive symptoms were also related to more rejection sensitivity at Time 2, whereas conduct problems were associated with lower self-worth.

Discussion

Previous research on the cognitive vulnerability model to depression among youth has been based largely on cross-sectional designs with relatively small and often clinically derived samples. This research has yielded inconsistent results with respect to specificity. We used longitudinal data weighted to reflect a public middle school population to examine bidirectional associations and to test for specificity of attributional style, self-worth, and rejection sensitivity as they are associated with depressive versus conduct and anxiety problems during early adolescence. Our findings suggest that in general the temporal pathways between these cognitive features and psychopathology symptoms operate in both directions, although the influences in most cases were not symmetrical. In addition to vulnerabilities, cognitive scars emerged from the experience of elevated symptomatology. Moreover, both specific and general effects emerged for the cognitive features examined.

Contrary to the hopelessness theory, attributional style was not associated with vulnerability to depressive symptoms among adolescents but rather emerged as a scar effect, residual to the experience of elevated symptoms. The experience of depressed mood appears to precede negative attributions among young adolescents. These findings are compatible with other studies that have found that elevated depressive symptoms contribute to the development of negative attributional style in children (Bennett & Bates, 1995; Gibb et al., 2006; Nolen-Hoeksema et al., 1992). However, our results also indicate that the scar effects of depression on attributional style were not unique to depression but were also common to conduct problems. In a recent study, Gibb and colleagues (2006) found that negative attributional style accounted for some of the relation between two types of conduct problems (delinquency and oppositionality) with depressed mood. Because their study was cross-sectional, the authors were unable to tease apart the nature of these associations. Although our study is limited by the use of only two time points, these results suggest that the pathway may run from behavior to cognitions, with youth who display more conduct problems subsequently demonstrating pessimistic attributions, perhaps because their behavior generates negative outcomes. Thus, negative attributions may result from both depressive and conduct problems. Future research should examine the degree to which such attributions reflect a perceptual bias versus a realistic appraisal.

Although low self-worth created vulnerability to greater depression over the course of a year among adolescents, it was also bidirectionally associated with increased conduct problems. This could indicate that low self-worth is a “core process” shared between these two forms of psychopathology; that is, low self-worth could be a general risk that creates risk toward broad presentations of psychopathology. A recent debate has questioned whether youth with conduct problems have negative or overly positive views of themselves. Our study suggests that there is a negative self-evaluation component for adolescents with elevated conduct problems, largely consistent with a recent series of studies finding robust associations between low self-esteem and problem behavior among adolescents and young adults (Donnellan et al., 2005). It may be noteworthy that several of the studies that have indicated inflated self-appraisals among youth with externalizing problems were conducted with elementary school age children who are more prone to positive cognitive biases (Hoza, Waschbusch, Pelham, Molina, & Milich, 2000; Hughes, Cavell, & Grossman, 1997). Thus, one possible explanation for the inconsistency within the self-esteem literature that warrants further investigation is that there may be developmental shifts in self-appraisals for youth with externalizing behavior occurring between late childhood and early adolescence.

Our findings are also compatible with the notion that a negative self-image could function as a common link between the emergence of conduct and co-occurring depressive symptoms, which typically manifest subsequent to conduct problems (Biederman, Faraone, Mick, & Lelon, 1995). These results are compelling in suggesting further exploration into cascade models of psychopathology, which posit that poor functioning in one domain of behavior can snowball into problems within other domains (Burke, Loeber, Lahey, & Rathouz, 2005; Masten et al., 2005). The “failure model” proposed by Patterson and Capaldi (1990), for example, suggested that early conduct problems result in failure experiences that in turn create vulnerability to subsequent depression. Our research suggests that another consequence or “failure” created by conduct problems may be a shift toward a more negative view of the self. Future research should explore the role of both cognitions and consequences of failure experiences in understanding sequential comorbidity between conduct problems and depression.

The third cognitive feature examined, rejection sensitivity, was chosen based on cognitive interpersonal models of depression that suggest that depressed persons have negative expectations and experiences in their interactions with others. Rejection sensitivity created vulnerability only to anxiety symptoms but emerged as a cognitive scar of depression, such that having elevated depression was associated with a subsequent propensity to perceive and expect rejection in ambiguous situations and to react with anxious affect. These results support findings linking rejection sensitivity to loneliness and social anxiety (Downey, Bonica, London, & Paltin, in press), perhaps because of the nervous affect associated with anticipating rejection. The scar effect found here is also consistent with studies finding that depressive symptoms predict social self-perceptions (Kistner et al., 2006; Rohde et al., 1990). The interactional framework for depression suggests that the behaviors of depressed individuals lead them to get rejected by others (Coyne, 1976, 1999). It is possible, then, that youth who have elevated depressive symptoms are more sensitive to rejection due to the scarring effects of actually having experienced rejection more often or due to a social information processing residue that remains following a depressed mood.

Collectively, the findings advanced in this study are consistent with the mutual interplay of cognitive features with youth psychopathology, including particular cognitive features as risks for later psychopathology as well as the emergence of cognitive biases as a result of experiencing psychopathology. In terms of informing our theories of etiology, this research does not suggest that cognitive features uniquely contribute to a pathogenic process for depression. Rather, they suggest that negative evaluations of the self, events, and interpersonal situations emerge in tandem with varied presentations of psychopathology among youth. Several clinical implications of this research warrant further investigation. First, the results show that low self-worth in particular creates vulnerability toward depressive symptoms and conduct problems during the transition to adolescence. Thus, youth who have poor self-esteem may be an appropriate target group for indicated preventive intervention programs. The results also show that rejection sensitivity can result specifically from the experience of depression and would suggest that it would be beneficial to specifically address rejection (both real and perceived) as a component of intervening with depressed youth. Two of the more efficacious genres of treatment for adolescent depression, interpersonal psychotherapy and cognitive–behavioral therapy, can address rejection as an intervention goal, via the interpersonal focus of interpersonal psychotherapy and via the cognitive focus in cognitive–behavioral therapy. Application of a combined cognitive–interpersonal theoretical framework is potentially useful in intervening with depression in adolescents. A third clinical implication is that some focus on cognitions for youth with conduct problems may be warranted, given the associations found in this study. For example, youth with conduct problems may benefit from learning to reassess and reinterpret events in their lives, as well as from learning strategies for exerting control that is appropriate to the situation (Compas, Connor-Smith, Saltzman, Thomsen, & Wadsworth, 2001), instead of feeling helpless, relinquishing control, and experiencing numerous failures.

Because of several limitations of this study, broad conclusions must be tempered. Although the magnitude of effects was generally small, the findings are enhanced by the use of cross-lagged analyses that control for synchronous relations and stability of measures and that include depression, conduct problems, and anxiety simultaneously. The interval used for the prospective analyses was 1 year during early adolescence. A different interval during a different development period may have yielded different findings. Moreover, although having longitudinal data represents a step forward in understanding the role of cognitive vulnerability and psychopathology, we are limited by the use of cross-lagged panel analyses using only two time points. To facilitate a better understanding of directionality, research examining these constructs over a longer course of time and with more frequent assessments is needed. Likewise, it is unknown at this time to what extent relations between cognitive features and psychopathology are consistent throughout development. We limited our models to cognitive factors, excluding other important risk factors that clearly play a role in the development of youth psychopathology and may interact with cognitive factors, such as biological risk, family environment, and peer interactions. Moreover, our examination of cognitive features was not intended to be fully exhaustive; rather, we strove to include salient constructs that are represented in major cognitive and cognitive-interpersonal theories, but in doing so we have omitted other dimensions of cognition, such as automatic thought content and rumination. Finally, the Children’s Attributional Style Questionnaire–Revised has been criticized for its generally low internal consistency reliability (Hankin & Abramson, 2002a, 2002b), which may have attenuated the strength of the associations between cognitive style and emotional health conditions. Psychometrically stronger alternatives to assessing attributional style that are appropriate for this age range have only become available since this study began (e.g., Conley, 2001; Mezulis et al., in press) and should be considered in future research.

A number of strengths of the study warrant consideration in assessing the contribution of this research. First, we incorporated into our models various dimensions of cognitive style drawn from hopelessness, Beckian, and cognitive interpersonal theories, including attributional style, self-worth, and rejection sensitivity, dimensions not previously examined together. We also modeled and examined three forms of psychopathology to control for co-occurring symptoms. We used a longitudinal design, controlling for baseline levels of earlier symptoms, which allowed us to examine change over time instead of cross-sectional associations and contributed to our ability to disentangle vulnerability from scar effects. Finally, we utilized a school-based sample, weighted to generalize to a large, racially diverse public middle school population. The data support relations in both directions between cognitive features and youth psychopathology and demonstrate that various cognitive features are pertinent not only to depression but also to other forms of psychopathology. To advance the field to a broader understanding of cognitive processes in the development of psychopathology, further research, and an expanded longitudinal view of the interplay between cognitions and symptomatology throughout childhood, adolescence, and adulthood is needed. This understanding will be helpful in developing and refining effective prevention and intervention strategies.

References

- Abela JR. The hopelessness theory of depression: A test of the diathesis–stress and causal mediation components in third and seventh grade children. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2001;29:241–254. doi: 10.1023/a:1010333815728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abela JR, Hankin BL, Haigh EAP, Adams P, Vinokuroff T, Trayhern L. Interpersonal vulnerability to depression in high-risk children: The role of insecure attachment and reassurance seeking. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2005;34:182–192. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp3401_17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abela JR, Sarin S. Cognitive vulnerability to hopelessness depression: A chain is only as strong as its weakest link. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 2002;26:811–829. [Google Scholar]

- Abramson LY, Alloy LB, Hankin BL, Haefell GJ, MacCoon DG, Gibb BE. Cognitive vulnerability–stress models of depression in a self-regulatory and psychobiological context. In: Gotlib IH, Hammen CL, editors. Handbook of depression. New York: Guilford; 2002. pp. 268–294. [Google Scholar]

- Abramson LY, Alloy LB, Metalsky GI. The cognitive diathesis–stress theories of depression: Toward an adequate evaluation of the theories’ validities. In: Alloy LB, editor. Cognitive processes in depression. New York: Guilford; 1988. pp. 3–30. [Google Scholar]

- Achenbach T. Manual for the Child Behavior Checklist=4–18 and 1991 Profile. Burlington: University of Vermont, Department of Psychiatry; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Achenbach TM, Rescorla LA. Manual for the ASEBA school-age forms and profiles. Burlington: University of Vermont Research Center for Children, Youth, and Families; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 3. Washington, DC: Author; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Angold A, Costello EJ. Depressive comorbidity in children and adolescents: Empirical, theoretical and methodological issues. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1993;150:1779–1791. doi: 10.1176/ajp.150.12.1779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angold A, Costello EJ, Erkanli A. Comorbidity. Journal of Child Psychology & Psychiatry. 1999;40:57–87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT. Depression: Clinical, experimental, and theoretical aspects. New York: Harper & Row; 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Bennett DS, Bates JE. Prospective models of depressive symptoms in early adolescence: Attributional style, stress, and support. Journal of Early Adolescence. 1995;15:299–315. [Google Scholar]

- Biederman J, Faraone S, Mick E, Lelon E. Psychiatric comorbidity among referred juveniles with major depression: Fact or artifact? Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 1995;34:579–590. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199505000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bollen KA. Structural equations with latent variables. New York: Wiley; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Burke JD, Loeber R, Lahey BB, Rathouz PJ. Developmental transitions among affective and behavioral disorders in adolescent boys. Journal of Child Psychology & Psychiatry. 2005;46:1200–1210. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2005.00422.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coie JK, Dodge KA. Aggression and antisocial behavior. 5. Vol. 3. New York: Wiley; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Cole DA, Martin JM, Peeke LG, Seroczynski AD, Hoffman K. Are cognitive errors of underestimation predictive or reflective of depressive symptoms in children: A longitudinal study. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1998;107:481–498. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.107.3.481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Compas BE, Connor-Smith JK, Saltzman H, Thomsen AH, Wadsworth ME. Coping with stress during childhood and adolescence: Problems, progress, and potential in theory and research. Psychological Bulletin. 2001;127:87–127. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conley CS, Haines BA, Hilt LM, Metalsky GI. The children’s attributional style interview: Developmental tests of cognitive diathesis-stress theories of depression. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2001;106:251–259. doi: 10.1023/a:1010451604161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costello EJ, Angold A. Scales to assess child and adolescent depression: Checklists, screens, and nets. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 1988;27:726–737. doi: 10.1097/00004583-198811000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costello EJ, Angold A, Burns B, Stangl D, Tweed DL, Erkanli A, et al. The Great Smoky Mountains Study of Youth: Goals, design, methods, and the prevalence of DSM–III–Rdisorders. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1996;53:1129–1136. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1996.01830120067012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coyne JC. Toward an interactional description of depression. Journal for the Study of Interpersonal Process. 1976;39:28–40. doi: 10.1080/00332747.1976.11023874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coyne JC. Thinking interactionally about depression: A radical restatement. In: Joiner TE, Coyne JC, editors. The interactional nature of depression: Advances in interpersonal approaches. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 1999. pp. 365–392. [Google Scholar]

- Crick NR, Dodge K. A review and reformulation of social information-processing mechanisms in children’s social adjustment. Psychological Bulletin. 1994;115:74–101. [Google Scholar]

- Donnellan MB, Trzesniewski KH, Robins RW, Moffitt TE, Caspi A. Low self-esteem is related to aggression, antisocial behavior, and delinquency. Psychological Science. 2005;16:328–335. doi: 10.1111/j.0956-7976.2005.01535.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Downey G, Bonica C, London B, Paltin I. Causes and consequences of rejection sensitivity. Journal of Research on Adolescence in press. [Google Scholar]

- Downey G, Lebolt A, Rincon C, Freitas AL. Rejection sensitivity and children’s interpersonal difficulties. Child Development. 1998;69:1074–1091. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fenzel LM. Prospective study of changes in global self-worth and strain during the transition to middle school. Journal of Early Adolescence. 2000;20:93–116. [Google Scholar]

- Gibb BE, Alloy LB. A prospective test of the hopelessness theory of depression in children. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2006;35:264–274. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp3502_10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibb BE, Alloy LB, Walshaw PD, Comer JS, Shen GHC, Villari AG. Predictors of attributional style change in children. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2006;34:425–439. doi: 10.1007/s10802-006-9022-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gotlib IH, Lewinsohn PM, Seeley JR, Rohde P, Redner JE. Negative cognitions and attributional style in depressed adolescents: An examination of stability and specificity. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1993;102:607–615. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.102.4.607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammen C. Cognitive, life stress, and interpersonal approaches to a developmental psychopathology model of depression. Development and Psychopathology. 1992;4:191–208. [Google Scholar]

- Hammen C, Burge D, Daley SE, Davila J, Paley B, Rudolph KD. Interpersonal attachment cognitions and prediction of symptomatic responses to interpersonal stress. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1995;104:436–443. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hankin BL, Abramson LY. Development of gender differences in depression: An elaborated cognitive vulnerability–transactional stress theory. Psychological Bulletin. 2001;127:773–796. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.127.6.773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hankin BL, Abramson LY. Measuring cognitive vulnerability to depression in adolescence: Reliability, validity, and gender differences. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2002b;31:491–504. doi: 10.1207/S15374424JCCP3104_8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hankin BL, Abramson LY, Moffitt TE, Silva PA, McGee R, Angell KE. Development of depression from preadolescence to young adulthood: Emerging gender differences in a 10-year longitudinal study. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1998;107:128–140. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.107.1.128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harter S. The Perceived Competence Scale for Children. Child Development. 1982;53:87–97. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harter S. Manual for the self-perception profile for children. Denver, CO: University of Denver; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Harter S, Whitesell NR. Multiple pathways to self-reported depression and psychological adjustment among adolescents. Development and Psychopathology. 1996;8:761–777. [Google Scholar]

- Hays RD, Marshall GN, Wang EYI, Sherbourne CD. Four years cross-lagged associations between physical and mental health in a medical outcome study. Journal of Consulting & Clinical Psychology. 1994;62:441–449. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.62.3.441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoza B, Waschbusch D, Pelham W, Molina B, Milich R. Attention-deficit=hyperactivity disordered and control boys’ responses to social success and failure. Child Development. 2000;71:432–446. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu L, Bentler PM. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling. 1999;6:1–55. [Google Scholar]

- Hughes JN, Cavell TA, Grossman PB. A positive view of self: Risk or protection for aggressive children. Development and Psychopathology. 1997;9:75–94. doi: 10.1017/s0954579497001077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ingram RE, Miranda J, Segal ZV. Cognitive vulnerability to depression. New York: Guilford; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Joiner TE, Wagner KD. Attributional style and depression in children and adolescents: A meta-analytic review. Clinical Psychology Review. 1995;15:777–798. [Google Scholar]

- Kaslow NJ, Rehm LP, Pollock SL, Siegel AW. Attributional style and self-control behavior in depressed and nondepressed children and their parents. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 1988;16:163–175. doi: 10.1007/BF00913592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kent L, Vostanis P, Feehan C. Detection of major and minor depression in children and adolescents: Evaluation of the Mood and Feelings Questionnaire. Journal of Child Psychology & Psychiatry. 1997;38:565–573. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1997.tb01543.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kistner JA, David-Ferdon CF, Repper KK, Joiner TJ. Bias and accuracy of children’s perceptions of peer acceptance: Prospective associations with depressive symptoms. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2006;34:349–361. doi: 10.1007/s10802-006-9028-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loeber R, Wung P, Keenan K, Giroux B, Stouthamer-Loeber M, Van Kammen WB, et al. Developmental pathways in disruptive child behavior. Development and Psychopathology. 1993;5:103–133. [Google Scholar]

- March JM, Staff HS. Multidimensional Anxiety Scale for Children (MASC): Technical manual. North Tonawanda, NY: Multi-Health Systems; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Masten AS, Roisman GI, Long JD, Burt KB, Obradovic J, Riley JR, et al. Developmental cascades: Linking academic achievement and externalizing and internalizing symptoms over 20 years. Developmental Psychology. 2005;41:733–746. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.41.5.733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCauley E, Mitchell JR, Burke P, Moss S. Cognitive attributes of depression in children and adolescents. Journal of Consulting & Clinical Psychology. 1988;56:903–908. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.56.6.903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGrath EP, Repetti RL. A longitudinal study of children’s depressive symptoms, self-perceptions, and cognitive distortions about the self. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2002;111:77–87. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.111.1.77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mezulis AH, Abrahamson LY, Hyde JS, Hankin BL. Is there a universal positivity bias in attributions? A meta-analytic review of individual, developmental, and cultural differences in the self-serving attributional bias. Psychological Bulletin. 2004;139:711–747. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.130.5.711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mezulis A, Hyde JS, Abramson LY. The developmental origins of cognitive vulnerability to depression: Temperament, parenting, and negative life events in childhood as contributors to negative cognitive style. Developmental Psychology. 42:1012–1025. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.42.6.1012. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO. MPlus user’s guide: The comprehensive modeling program for applied researchers (1998–2004) Los Angeles: Author; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Nolen-Hoeksema S, Girgus JS, Seligman MEP. Predictors and consequences of childhood depressive symptoms: A 5-year longitudinal study. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1992;101:405–422. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.101.3.405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patterson GR, Capaldi DM. A mediational model for boys’ depressed mood. In: Rolf J, Master AS, Cicchetti D, Neuchterlin KH, Weintraub S, editors. Risk and protective factors in the development of psychopathology. New York: Cambridge University Press; 1990. pp. 141–163. [Google Scholar]

- Quiggle NL, Garber J, Panak WF, Dodge KA. Social information processing in aggressive and depressed children. Child Development. 1992;63:1305–1320. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson NS, Garber J, Hilsman R. Cognitions and stress: Direct and moderating effects on depressive versus externalizing symptoms during the junior high school transition. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1995;104:453–463. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.104.3.453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohde P, Lewinsohn PM, Seeley JR. Are people changed by the experience of having a depressed episode? A further test of the scar hypothesis. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1990;99:264–271. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.99.3.264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudolph KD, Clark AG. Conceptions of relationships in children with depressive and aggressive symptoms: Social–cognitive distortion or reality? Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2001;29:41–56. doi: 10.1023/a:1005299429060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudolph KD, Hammen C, Burge D. A cognitive–interpersonal approach to depressive symptoms in preadolescent children. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 1997;25:33–45. doi: 10.1023/a:1025755307508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudolph KD, Lambert SF, Clark AG, Kurlakowsky KD. Negotiating the transition to middle school: The role of self-regulatory processes. Child Development. 2001;72:929–946. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schniering CA, Rapee RM. The relationship between automatic thoughts and negative emotions in children and adolescents: A test of the cognitive content-specificity hypothesis. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2004;113:464–470. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.113.3.464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shahar G, Blatt SJ, Zuroff DC, Kuperminc GP, Leadbeater BJ. Reciprocal relations between depressive symptoms and self-criticism (but not dependency) among early adolescent girls (but not boys) Cognitive Therapy and Research. 2004;28:85–103. [Google Scholar]

- Shirk SR, Van Horn M, Leber D. Dysphoria and children’s processing of supportive interactions. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 1997;25:239–249. doi: 10.1023/a:1025752100781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stipek D, MacIver D. Developmental change in children’s assessment of intellectual competence. Child Development. 1989;60:521–538. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson M, Kaslow N, Weiss B, Nolen-Hoeksema S. Children’s attributional style questionnaire–revised: Psychometric examination. Psychological Assessment. 1998;10:166–170. [Google Scholar]

- Turner JE, Cole DA. Developmental differences in cognitive diatheses for child depression. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 1994;22:15–32. doi: 10.1007/BF02169254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wigfield A, Eccles JS. Children’s competence beliefs, achievement values, and general self-esteem: Change across elementary and middle school. Journal of Early Adolescence. 1994;14:107–138. [Google Scholar]

- Wood A, Kroll L, Moore A, Harrington R. Properties of the Mood and Feelings Questionnaire in adolescent psychiatric outpatients: A research note. Journal of Child Psychology & Psychiatry. 1995;36:327–334. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1995.tb01828.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]