Abstract

Objectives:

We investigated (1) whether sexual, physical, or emotional abuse experienced either as a child or as an adolescent/adult is associated with symptoms of urinary frequency, urgency, and nocturia, and (2) the extent to which the observed association between abuse and urologic symptoms may be causal.

Methods:

Analyses are based on data from the Boston Area Community Health (BACH) survey, a community-based epidemiologic study of many different urologic symptoms and risk factors. BACH used a multistage stratified cluster sample to recruit 5506 adults, aged 30[en]79 yr (2301 men, 3205 women; 1770 black [African American], 1877 Hispanic, and 1859 white respondents).

Results:

The symptoms considered are common, with 33% of BACH respondents reporting urinary frequency, 12% reporting urgency, and 28% reporting nocturia. All three symptoms are positively associated with childhood and adolescent/adult sexual, physical, and emotional abuse (p < 0.05), with abuse significantly increasing the odds of urinary frequency by a factor ranging from 1.6 to 1.9, the odds of urgency by a factor from 2.0 to 2.3, and the odds of nocturia by a factor from 1.3 to 1.5.

Conclusions:

Our analyses extend previous work. First, we show a strong association between abuse and urinary frequency, urgency, and nocturia in a community-based random sample. Second, we move beyond discussion of statistical association and find considerable evidence to suggest that the relationship between abuse and these symptoms may be causal.

Keywords: Abuse, Corticotrophin-releasing factor (CRF), Epidemiology, Nocturia, Stress, Symptom research, Urgency, Urinary frequency

1. Introduction

Abuse has been identified as a major public health issue, with national probability and community-based samples conservatively estimating that well over one quarter of the United States adult population report either physical or sexual lifetime abuse [1[en]4]. Medically, abuse is strongly associated with a range of gastroenterologic and genitourinary symptoms [5[en]13].

This linkage is not surprising because anxiety and fear may manifest as physical symptoms, especially urinary and sexual complaints, even years after the abuse has occurred [14]. Previous studies have focused on women or children who have been abused [7[en]10]. Conversely, examination of women and children with voiding complaints have found that a substantial portion were victims of abuse or severe psychological trauma [6]. This association between abuse and urinary complaints has been attributed to an underlying psychological issue rather than a physiologic abnormality [16]. However, contemporary studies of the neurobiologic basis for stress and anxiety offer a plausible mechanism whereby physical or psychological abuse can sensitize micturition pathways, leading to an overactive bladder characterized by urinary urgency, usually with frequency or nocturia [17[en]19]. Urologic symptoms are not uncommon in the population [20,21].

We extend existing literature in this area in two ways. First, we investigated the association of different types of abuse and the urologic symptoms of frequency, urgency, and nocturia in a diverse community-based random sample. Second, and moving beyond previous work, we considered whether the relationship between abuse and these symptoms may be said to be causal. To do this we drew from Sir Austin Bradford Hill's classic discussion of criteria for determining whether an association can be considered causal [22]. Although there is continuing debate on the subject of causality [23[en]25], Hills criteria provide a useful starting point when considering this question.

2. Methods

The Boston Area Community Health (BACH) survey is a community-based epidemiologic study of urologic symptoms and risk factors conducted from 2002 to 2005. BACH is a cross-sectional random sample of community-dwelling adults, not a convenience sample. Detailed methods are given in a previous paper in this issue [26]. In brief, BACH used a multistage stratified random sample to recruit 5506 adults aged 30[en]79 yr in three racial/ethnic groups from the city of Boston (2301 men, 3205 women, 1770 black [African American], 1877 Hispanic, 1859 white respondents). Information about urologic symptoms, comorbidities, lifestyle, anthropometrics, and psychosocial attributes was collected via an interviewer-administered questionnaire; respondents used a self-administered questionnaire to answer questions about sexual function and abuse.

The BACH survey asked several questions about urinary frequency, urgency, and nocturia (Table 1). Respondents were said to have: (a) urinary frequency if they needed to urinate again < 2 h after urinating (fairly often, usually, almost always) and/or had frequent urination during the day (fairly often, usually, almost always) and/or had (on average) eight or more urinations during the day; (b) urgency if they had difficulty postponing urination (fairly often, usually, almost always) and/or had a strong urge or pressure to urinate immediately with no or little warning (fairly often, usually, almost always) and/or had a strong urge or pressure to urinate immediately whether or not they urinated or leaked urine (several times, many times, every day); and (c) nocturia if they had to get up to urinate more than once during the night (fairly often, usually, almost always) and/or had (on average) two or more urinations during the night after falling asleep. Composite measures were created as we found that the different questions for frequency, urgency, and nocturia did not give similar responses. These composite measures are different from the current International Continence Society definitions [27].

Table 1.

Questions (and source used) to determine urologic symptoms and presence of abuse

| Measure | Question |

Possible responses |

Reference/source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Frequency | During the last month, how often have you had to urinate again < 2 h after you finished urinating? |

I do not have symptom, rarely, a few times, fairly often, usually, almost always |

49 |

| During the last month, how often have you had frequent urination during the day? |

I do not have symptom, rarely, a few times, fairly often, usually, almost always |

50 | |

| In the last 7 d, on average, how many times have you had to go to the bathroom to empty your bladder during the day? |

Number [en] 8+ |

51 | |

| Urgency | During the last month, how often have you had difficulty postponing urination? |

I do not have symptom, rarely, a few times, fairly often, usually, almost always |

49 |

| During the last month, how often have you had a strong urge or pressure to urinate immediately, with no, or little warning? |

I do not have symptom, rarely, a few times, fairly often, usually, almost always |

50 | |

| Some people experience a strong urge to urinate or a pressure to urinate that signals the need to urinate. In the last 7 d, how many times did you feel a strong urge or pressure that signaled the need to urinate immediately, whether or not you urinated or leaked urine? |

Not at all, once, a few times (2[en]3), Several times (4[en]6), many times (≥ 7), every day |

51 | |

| Nocturia | During the last month, how often have you had to get up to urinate more than once dung the night? |

I do not have symptom, rarely, a few times, fairly often, usually, almost always |

|

| In the last 7 d, on average, how many times have you had to go to the bathroom to empty your bladder during the night after falling asleep? |

Number [en] 2+ |

49 | |

| Sexual abuse |

During your childhood/adolescence or adulthood has any adult ever done the following? |

28 | |

| Exposed the sex organs of their body to you when you did not want it? |

Yes, no | ||

| Threatened to have sex with you when you did not want this? |

Yes, no | ||

| Touched the sex organs of your body when you did not want this? |

Yes, no | ||

| Made you touch the sex organs of their body when you did not want this? |

Yes, no | ||

| Forced you to have sex when you did not want this? |

Yes, no | ||

| Have you had any other unwanted sexual experiences not mentioned above? |

Yes, no | ||

| Physical abuse |

When you were a child/adolescent or adult, has any (other) adult done the following? |

28 | |

| Hit, kicked, or beaten you? |

Never, seldom, occasionally, often |

||

| Seriously threaten your life? |

Never, seldom, occasionally, often |

||

| Emotional abuse |

When you were a child/adolescent or adult, has any (other) adult emotionally abused, humiliated, or insulted you? |

Never, seldom, occasionally, often |

Highlighted/boldface responses are indicative of the urologic symptom.

Three types of abuse (sexual, physical, and emotional) were assessed over two life stages (childhood [age 13 or younger], adolescence/adulthood [age 14 or older]) using a validated self-administered questionnaire [28] (Table 1). Sexual abuse was defined as present if the respondent reported any of the following (unwanted) experiences (and the perpetuator was an adult): exposed sex organs of their body (only included in the definition of childhood sexual abuse), threatened to have sex, touched respondents sex organs, made respondent touch their sex organs, forced respondent to have sex, or other sexual experiences. Physical abuse was defined as present if the respondent reported being hit, kicked, or beaten by an adult (occasionally or often) or having his/her life seriously threatened (seldom, occasionally, or often). Emotional abuse was defined as present if an adult had emotionally abused, humiliated, or insulted the respondent (occasionally or often).

We used a Χ2 test of independence and logistic regression to determine if the urologic symptoms of frequency, urgency, and nocturia were associated with different types of abuse. A linear test for trend was performed for data on frequency of abuse and frequency of the urologic symptoms. Information on urologic symptoms from the interviewer-administered questionnaire was seldom missing (< 1%), but information about abuse from the self-administered questionnaire was more frequently missing (about 10%). Missing data were replaced by plausible values using 25 multiple imputations [29]. To be representative of the city of Boston, observations were weighted inversely proportional to their probability of selection [30]. Weights were then post-stratified to the Boston population according to the 2000 census. Analyses were conducted in version 9.1 of SAS (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA) and version 9.0.1 of SUDAAN (Research Triangle Institute, Research Triangle Park, NC, USA).

3. Results

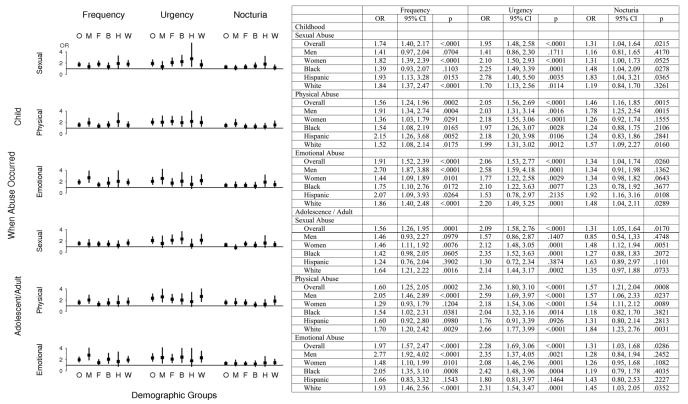

The prevalence of various types of abuse are comparable (Table 2) to the limited available information from other population-based US surveys [1[en]3]. The prevalence of urinary frequency, urgency, and nocturia was significantly (p < 0.05) higher in the group that had experienced abuse (Table 3). This was consistent for each urologic symptom and for each type of abuse. Moreover, these patterns hold if we look at various subgroups, gender and race/ethnicity (Fig. 1). In results not presented here, we used logistic regression to consider interactions between abuse and gender, abuse and race/ethnicity, and three-way interactions between abuse and gender and race/ethnicity. The only interactions that were significant (p < 0.05) were of emotional abuse (childhood and adult) and gender with urinary frequency. However, the association of emotional abuse and frequency is significant for both genders; therefore on examination of the interaction, we conclude that the effect is smaller for women compared to men.

Table 2.

Prevalence of frequency, urgency, nocturia, and different types of abuse overall and by gender

| Variable | Overall, % | Men, % | Women, % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Frequency | 32.6 | 27.8 | 36.9 |

| Urgency | 11.9 | 9.3 | 14.2 |

| Nocturia | 28.4 | 25.3 | 31.3 |

| Childhood | |||

| Sexual abuse | 21.6 | 16.2 | 26.5 |

| Physical abuse | 22.7 | 24.5 | 21.1 |

| Emotional abuse | 18.7 | 18.4 | 19.0 |

| Adolescence/adulthood | |||

| Sexual abuse | 19.5 | 12.6 | 25.7 |

| Physical abuse | 19.4 | 17.9 | 20.7 |

| Emotional abuse | 19.0 | 14.8 | 22.9 |

Table 3.

Prevalence of urologic symptoms for those who have or have not experienced different kinds of abuse and odds ratios for the association of different types of abuse and urologic symptoms (p values in parentheses)

| Frequency | Urgency | Nocturia | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prevalence, % |

Odds ratio |

Prevalence, % |

Odds ratio |

Prevalence, % |

Odds ratio |

|

| Childhood | ||||||

| Sexual abuse | (<.0001) | (<.0001) | (<.0001) | (<.0001) | (.0227) | (.0215) |

| Yes | 42.6 | 1.74 | 18.1 | 1.95 | 32.8 | 1.31 |

| No | 29.8 | 10.1 | 27.2 | |||

| p | (<.0001) | (<.0001) | (<.0001) | (<.0001) | (.0227) | (.0215) |

| Physical abuse | ||||||

| Yes | 40.4 | 1.56 | 18.4 | 2.05 | 34.7 | 1.46 |

| No | 30.3 | 9.9 | 26.6 | |||

| p | (.0004) | (.0002) | (<.0001) | (<.0001) | (.0034) | (.0015) |

| Emotional abuse |

||||||

| Yes | 40.8 | 1.91 | 19.0 | 2.06 | 33.5 | 1.34 |

| No | 30.6 | 10.1 | 27.3 | |||

| p | (<.0001) | (<.0001) | .0001 | (<.0001) | (.0344) | (.0260) |

| Adolescent/adult Sexual abuse | ||||||

| Yes | 40.8 | 1.56 | 19.0 | 2.09 | 33.0 | 1.31 |

| No | 30.6 | 10.1 | 27.3 | |||

| p | (.0001) | (.0001) | (<.0001) | (<.0001) | (.0224) | (.0170) |

| Physical abuse | ||||||

| Yes | 41.2 | 1.60 | 20.4 | 2.36 | 36.2 | 1.57 |

| No | 30.5 | 9.8 | 26.6 | |||

| p | (.0006) | (.0002) | (<.0001) | (<.0001) | (.0019) | (.0008) |

| Emotional abuse |

||||||

| Yes | 45.3 | 1.97 | 20.0 | 2.28 | 33.1 | 1.31 |

| No | 29.6 | 9.9 | 27.4 | |||

| p | (<.0001) | (<.0001) | (<.0001) | (<.0001) | (.0354) | (.0286) |

Fig. 1. Odds ratios (OR) and 95 percent confidence intervals (CI) for the association of frequency, urgency, and nocturia with different kinds of abuse, overall, by gender, and by race/ethnicity.

Odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals of frequency, urgency, and nocturia for each type of abuse. Line at 1 = no effect; O = overall; M = men; F = women; B = black (African American); H = Hispanic; W = white.

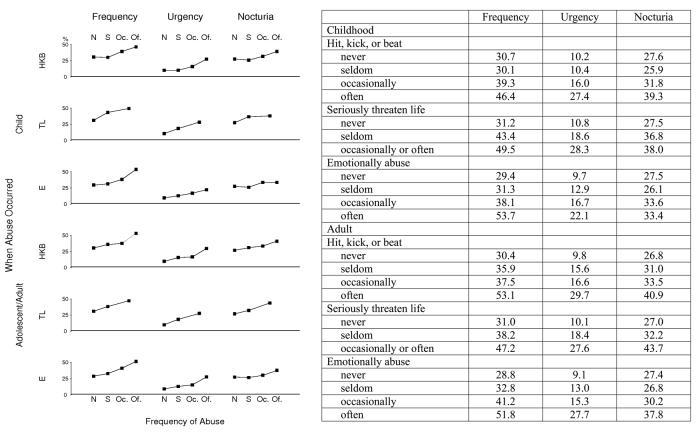

We sought to determine whether there is evidence of a dose-response relationship between abuse and urologic symptoms. If abuse is more frequent, does the prevalence of urinary frequency, urgency, and nocturia also increase? To examine this question, we compared the frequency of the urologic symptoms with increasing frequency of abuse (Fig. 2). (The prevalence of urologic symptoms for the group reporting that they have occasionally and often had someone seriously threaten their life are combined due to low numbers in these cells.) We found that the prevalence of all three urologic symptoms increases with the frequency of each type of abuse. A linear test for trend is significant (p < 0.05) for each plot.

Fig. 2. Prevalence (percent) of frequency, urgency, and nocturia by frequency and type of abuse.

Prevalence (percent) of frequency, urgency, and nocturia with increasing frequency of abuse. HKB = hit, kick, or beat; TL = seriously threaten life; E = emotionally abused; N = never, S = seldom; Oc = occasionally; Of = often.

4. Discussion

We drew from Hill's [22] criteria for determining causation to more systematically examine characteristics of the associations observed in BACH and to assess the extent to which these results constitute evidence of a causal relationship between abuse and urinary frequency, urgency, and nocturia. We also considered which kinds of evidence should be sought in future work to continue to move the field beyond documenting association and toward the identification of causal mechanisms. Table 4 summarizes our results.

Table 4.

The extent to which the relationship between abuse and urologic symptoms can be considered causal: summary of criteria proposed by Hill in 1965

|

Criteria for establishing causation |

Data meet this criterion |

Comment |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Strength | Yes | The prevalence of (a) urinary frequency increases by 33[en]50%, (b) urgency doubles, and (c) nocturia increases by 25% in the group that has experienced abuse compared to those who have not. |

| 2. Consistency | Yes | The relationship holds for both men and women, also for black (African American), Hispanic, and white respondents. |

| 3. Specificity | Not applicable No |

The association is not restricted to specific people. Abuse is associated with other symptoms other than urinary frequency, urgency, and nocturia. |

| 4. Temporality | Potentially | Childhood abuse precedes (in the aggregate) current urologic symptoms. Longitudinal data not yet available. |

| 5. Biologic gradient (dose-response) | Yes | Increasing frequency of abuse leads to increased prevalence of symptoms. |

| 6. Biologic plausibility | Yes | Animal models suggest a biologic pathway. |

| 7. Coherence | Yes | No known evidence to contradict this causal relationship. |

| 8. Experiment (reversibility) | Yes | Intensive psychotherapy may ameliorate urologic symptoms. |

| 9. Analogy | Potentially | Data on comparable phenomena (PTSD) not presently available, although CRF appears to play a role in many anxiety disorders (including PTSD). |

PTSD = posttraumatic stress disorder; CRF = corticotropin-releasing factor.

4.1. Strength

The overall strength of the association is large. The prevalence of urinary frequency increases by 33[en]50%, the prevalence of urgency doubles, and the prevalence of nocturia increases by 25% in those that report experiencing abuse compared to those who do not. Any relationship producing an odds ratio (OR) indicating at least a 2-fold difference (OR ≥ 2.0 or ≤ 0.5) is unlikely to be due to chance. Conversely, any odds ratio in the interval 0.8[en]1.25 is at high risk to alternative explanation. All odds ratios reported here are outside that range and one was 2.0.

4.2. Consistency

The consistency of the results across both gender and race/ethnicity adds support to the case for a causal relationship. Although much previous work has focused on women and children, we report a consistent pattern among both men and women, across black (African American), Hispanic, and white respondents, and also across the life course. With respect to emotional abuse, evidence suggests that its effect on urinary frequency may be greater in men than its effect in women. That the integrity of the result holds across different gender and race/ethnic groups adds support for the causal argument.

4.3. Specificity

Specificity has two components. In the first, Hill [22] was concerned with occupational hazards and whether an association was present among a specific group of workers. This criterion is not directly applicable here because all respondents are potentially subject to abuse. The second consideration of specificity is the question of whether the association of abuse is restricted to a specific set of complaints. This is obviously false because abuse has been found to be associated with a number of ailments [5,12,13,31].

4.4 Temporality

The temporal ordering of abuse and these urologic symptoms will be the subject of future longitudinal work in the BACH study. On one hand, there is a strong association between childhood abuse and current urologic symptoms. Here the reported abuse (at least for the majority who have experienced symptoms < 6 yr) has preceded the current symptoms, thereby strengthening the causal hypothesis. As BACH transitions to a longitudinal cohort study, we should be able to determine if respondents who did not report symptoms at baseline are more likely to develop these urologic symptoms if they have reported abuse at baseline.

4.5. Biologic gradient (dose-response)

As discussed above, we find evidence of a biologic gradient or dose-response curve (Fig. 2), which further supports the possibility of a causal relationship. The increased prevalence of these urologic symptoms with increased frequency of abuse suggests a much more specific association than one of general association.

4.6. Biologic plausibility

Recent research has reported that anxiety and behavioral responses to stress involve complex neural circuits and multiple neurochemical components. Acute and chronic stress due to abuse can alter these circuits, their neurochemical components, and bladder function [15,32].

Most of the evidence for biologic plausibility comes from animal experiments. Stress induced by water immersion, cold, or restraint alters bladder histology and pharmacology [17,18,33,34]. Stress increases muscarinic-induced contractile responses in the bladder [19]. These alterations have been hypothesized to derive from mediators of stress and involve the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis (HPA) with an effector system relying on peripheral humoral factors.

An alternative explanation to a purely peripheral effector system for mediating traumatic experiences on urinary function relies on central neural mechanisms involved in the stress response. A primary neurotransmitter expressed by neurons within the central stress network is corticotrophin-releasing factor (CRF). CRF is expressed by neurons within a pontine micturition center found in Barringtons nucleus and within regions in the spinal cord that form part of the micturition reflex pathway [35,36].

Exogenous administration of CRF has variable effects on bladder function. For example, intracerebroventricular administration of CRF has been reported to decrease, increase, or have no effect on bladder activity [37]. In contrast, intrathecal CRF induces urinary frequency and lowers micturition volumes [38]. In animals subjected to stress, CRF is up-regulated in Barringtons nucleus, the amygdala, and paraventricular nucleus [35]. Mice overexpressing CRF exhibit behaviors associated with anxiety and increased urinary frequency [32,38]. Thus, experimental data suggest that increased CRF release by neurons in the central nervous system may heighten bladder activity.

The case for CRF being a link between abuse and increased bladder activity is made more robust by a large body of literature demonstrating neural plasticity within the HPA and amygdala in the pathogenesis of anxiety in victims of sexual abuse or posttraumatic stress [15,39[en]42]. Abused subjects demonstrate increased levels of CRF in the cerebrospinal fluid and heightened responses of the HPA to exogenous CRF than controls [15,41,43[en]45]. Investigators postulate that the neuroendocrine stress response is permanently altered in abuse victims [15]. The working hypothesis is that CRF is involved in a positive feed-forward system that becomes supersensitive to stress responses. Compelling evidence for a link between stress, CRF, and bladder function is the finding that systemic CRF-1 antagonists reduce urinary frequency and micturition volumes either due to exogenous CRF or in rats exhibiting anxiety [32,38]. It is relevant that CRF antagonists are currently under development to treat stress-induced depression and irritable bowel syndrome [32].

4.7. Coherence

Hill [22] suggested “the cause-and effect interpretation of our data should not seriously conflict with the generally known facts of the natural history and biology of the disease.” We know of nothing in the literature that would contradict the argument for a causal relationship.

4.8. Experiment (reversibility)

This criterion focuses on evidence that if the cause is removed, then the purportedly associated symptom will be ameliorated. Although previously experienced abuse cannot be removed, psychotherapy may relieve its deleterious effects. Frewan reported improvement in urinary symptoms after psychotherapy plus bladder training [46]. Corroborative support for potential reversibility is provided by Macaulay and coworkers [47] who reported that sensory urgency, detrusor overactivity, and incontinence can be cured by intense psychotherapy even without bladder training.

4.9. Analogy

This criterion proposes that the case for causation is strengthened if other comparable phenomena are also associated with a similar effect. With respect to abuse for example, somewhat comparable traumatic phenomena could be natural disasters (Tsunami), warfare (Iraq), and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Although a search of PubMed for PTSD and urinary symptoms did not yield any useful citations, an alternate search of PTSD and CRF did. CRF appears to play a significant role in many anxiety disorders including PTSD [48].

4.10. Summary

Although sexual and physical abuse has been reported to be associated with urologic symptoms in small numbers of female or juvenile patients [6[en]11], this research extends these results and reports that this association is also evident in a large (n = 5506) diverse community-based random sample of both men and women and across three different race/ethnic groups. We also report an association of emotional abuse and urologic symptoms and find that the association of emotional abuse and urinary frequency may be even more evident in men than in women.

Attention has tended to focus on the association of abuse and pelvic pain [31], but our research suggests that attention needs to be broadened to include the symptoms of urinary frequency, urgency, and nocturia, especially because these symptoms are much more common in the population.

We also show that our data fulfill many of Hill's [22] criteria to suggest causation including strength, consistency, dose-response, biologic plausibility, coherence, experiment, and analogy. We do not claim that abuse is the only cause of urologic symptoms, which may have many causes. This research is an attempt to move the field of urologic epidemiology from statistical association to causation and eventually the identification of physiologic pathways that are amenable to treatment.

4.11. Strengths and limitations

BACH has many strengths. BACH is a random sample of community-dwelling adults not a convenience sample of patients. BACH includes men and women, covers a broad age range, and includes adequate representation of the US primary racial/ethnic groups. BACH used validated instruments whenever possible and included questions on many urologic symptoms and confounders. BACH has some limitations. It was conducted in one geographic area. However, when comparing results from some national surveys to BACH, the health characteristics of Boston residents are similar (details at www.neriscience.com) suggesting that, with appropriate adjustments, results could be generalized to the US population. BACH does not include some other important race/ethnic groups such as Asians or Native Americans due to logistical challenges (many languages) or insufficient numbers. Definitions pose a serious challenge for abuse research and, particularly in a cross-national context, we would expect cultural differences and expectations on abuse to limit the extent to which prevalence rates and odds ratios can be compared directly across studies.

5. Conclusion

We show that current symptoms of urinary frequency, urgency, and nocturia are associated with previously experienced sexual, physical, and emotional abuse for both men and women and for three race/ethnic groups. We show that this association meets several criteria that suggest a causal relationship. Our results suggest that clinicians (both urologists and primary care providers) should consider the possible contribution of abuse when managing patients who present with the symptoms of urinary frequency, urgency, and nocturia.

Acknowledgments

Funded by National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (grant: U01 DK56842)

Footnotes

Take-home message

Physical, sexual, and emotional abuses experienced as a child or as an adolescent/adult are positively associated with urinary frequency, urgency, and nocturia. This association meets many criteria to suggest causation in a diverse community-based random sample of adults.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Scher CD, et al. Prevalence and demographic correlates of childhood maltreatment in an adult community sample. Child Abuse Negl. 2004;28:167–80. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2003.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Davis J, Smith T, Marsden P. General social surveys, 1972[en]2002, 2nd ICPSR Version. Roper Center for Public Opinion Research, University of Connecticut, Inter-University Consortium for Political and Social Research; Ann Arbor, MI: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tjaden P, Thoennes N. Full report of the prevalence, incidence, and consequences of violence against women: findings from the National Violence Against Women Survey. National Institute of Justice and the Center for Disease Control and Prevention; Washington, DC: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fact Sheets. 2002 World Health Organization: http://www.who.int/violence_injury_prevention/violence/world_report/factsheets/en/index.html.

- 5.Talley NJ, et al. Gastrointestinal tract symptoms and self-reported abuse: a population-based study. Gastroenterology. 1994;107:1040–9. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(94)90228-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Davila GW, et al. Bladder dysfunction in sexual abuse survivors. J Urol. 2003;170(2 pt 1):476–9. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000070439.49457.d9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hulme PA, Grove SK. Symptoms of female survivors of child sexual abuse. Issues Ment Health Nurs. 1994;15:519–32. doi: 10.3109/01612849409006926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Klevan JL, De Jong AR. Urinary tract symptoms and urinary tract infection following sexual abuse. Am J Dis Child. 1990;144:242–4. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1990.02150260122044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Reinhart MA, Adelman R. Urinary symptoms in child sexual abuse. Pediatr Nephrol. 1989;3:381–5. doi: 10.1007/BF00850210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ellsworth PI, Merguerian PA, Copening ME. Sexual abuse: another causative factor in dysfunctional voiding. J Urol. 1995;153(3 pt 1):773–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jundt K, et al. Physical and sexual abuse in patients with overactive bladder: is there an association? Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. doi: 10.1007/s00192-006-0173-z. In press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Leserman J. Sexual abuse history: prevalence, health effects, mediators, and psychological treatment. Psychosom Med. 2005;67:906–15. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000188405.54425.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Toomey TC, et al. Relationship of sexual and physical abuse to pain and psychological assessment variables in chronic pelvic pain patients. Pain. 1993;53:105–9. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(93)90062-T. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Menninger K. Some observations on the psychological factors in urination and genitourinary afflictions. Psychoanal Rev. 1941;28:117–29. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Penza KM, Heim C, Nemeroff CB. Neurobiological effects of childhood abuse: implications for the pathophysiology of depression and anxiety. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2003;6:15–22. doi: 10.1007/s00737-002-0159-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McCauley J, et al. The “battering syndrome”: prevalence and clinical characteristics of domestic violence in primary care internal medicine practices. Ann Intern Med. 1995;123:737–46. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-123-10-199511150-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ercan F, Oktay S, Erin N. Role of afferent neurons in stress induced degenerative changes of the bladder. J Urol. 2001;165:235–9. doi: 10.1097/00005392-200101000-00070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cao J, et al. Acute stress and intravesical corticotropin-releasing hormone induces mast cell dependent vascular endothelial growth factor release from mouse bladder explants. J Urol. 2006;176:1208–13. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2006.04.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Saito M, Kondo A, Miyake K. Changes in rat bladder function following exposure to pain and water stimuli. Int J Urol. 1995;2:92–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2042.1995.tb00431.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Irwin DE, et al. Population-based survey of urinary incontinence, overactive bladder, and other lower urinary tract symptoms in five countries: results of the EPIC study. Eur Urol. 2006;50:1306–14. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2006.09.019. discussion 1314[en]5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hutchison A, et al. Characteristics of patients presenting with LUTS/BPH in six European countries. Eur Urol. 2006;50:555–61. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2006.05.001. discussion 562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hill AB. The environment and disease: association or causation? Proc R Soc Med. 1965;58:295–300. doi: 10.1177/003591576505800503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Susser M. What is a cause and how do we know one? A grammar for pragmatic epidemiology. Am J Epidemiol. 1991;133:635–48. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a115939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Phillips CV, Goodman KJ. The missed lessons of Sir Austin Bradford Hill. Epidemiol Perspect Innov. 2004;1:3. doi: 10.1186/1742-5573-1-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hofler M. The Bradford Hill considerations on causality: a counterfactual perspective. Emerg Themes Epidemiol. 2005;2:11. doi: 10.1186/1742-7622-2-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McKinlay JB, Link CL. Measuring the urologic iceberg: design and implementation of the Boston Area Community Health (BACH) survey. Eur Urol. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2007.03.013. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Abrams P, et al. The standardisation of terminology of lower urinary tract function: report from the Standardisation Sub-committee of the International Continence Society. Neurourol Urodyn. 2002;21:167–78. doi: 10.1002/nau.10052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Leserman J, Drossman DA, Li Z. The reliability and validity of a sexual and physical abuse history questionnaire in female patients with gastrointestinal disorders. Behav Med. 1995;21:141–50. doi: 10.1080/08964289.1995.9933752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schafer JL. Analysis of incomplete multivariate data. Chapman and Hall; New York: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cochran WG. Sampling techniques. 3d ed. Wiley; New York: 1997. p. xvi, 428. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lampe A, et al. Chronic pelvic pain and previous sexual abuse. Obstet Gynecol. 2000;96:929–33. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(00)01072-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Klausner AP, Steers WD. Corticotropin releasing factor: a mediator of emotional influences on bladder function. J Urol. 2004;172(6 pt 2):2570–3. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000144142.26242.f3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dalal E, et al. Moderate stress protects female mice against bacterial infection of the bladder by eliciting uroepithelial shedding. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1994;730:302–3. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1994.tb44273.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ercan F, San T, Cavdar S. The effects of cold-restraint stress on urinary bladder wall compared with interstitial cystitis morphology. Urol Res. 1999;27:454–61. doi: 10.1007/s002400050135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Peoples JF, et al. Ultrastructure of endomorphin-1 immunoreactivity in the rat dorsal pontine tegmentum: evidence for preferential targeting of peptidergic neurons in Barrington's nucleus rather than catecholaminergic neurons in the peri-locus coeruleus. J Comp Neurol. 2002;448:268–79. doi: 10.1002/cne.10260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rouzade-Dominguez ML, et al. Convergent responses of Barrington's nucleus neurons to pelvic visceral stimuli in the rat: a juxtacellular labelling study. Eur J Neurosci. 2003;18:3325–34. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2003.03072.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kawatani M, et al. Ultrastructural analysis of enkephalinergic terminals in parasympathetic ganglia innervating the urinary bladder of the cat. J Comp Neurol. 1989;288:81–91. doi: 10.1002/cne.902880107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Klausner AP, et al. The role of corticotropin releasing factor and its antagonist, astressin, on micturition in the rat. Auton Neurosci. 2005;123:26–35. doi: 10.1016/j.autneu.2005.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Koob GF. Corticotropin-releasing factor, norepinephrine, and stress. Biol Psychiatry. 1999;46:1167–80. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(99)00164-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Koob GF, Heinrichs SC. A role for corticotropin releasing factor and urocortin in behavioral responses to stressors. Brain Res. 1999;848:141–52. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(99)01991-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lee R, et al. Childhood trauma and personality disorder: positive correlation with adult CSF corticotropin-releasing factor concentrations. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162:995–7. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.5.995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bremner JD, et al. Positron emission tomographic imaging of neural correlates of a fear acquisition and extinction paradigm in women with childhood sexual-abuse-related post-traumatic stress disorder. Psychol Med. 2005;35:791–806. doi: 10.1017/s0033291704003290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mello Ade A, et al. Update on stress and depression: the role of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis. Rev Bras Psiquiatr. 2003;25:231–8. doi: 10.1590/s1516-44462003000400010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rinne T, et al. Hyperresponsiveness of hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis to combined dexamethasone/corticotropin-releasing hormone challenge in female borderline personality disorder subjects with a history of sustained childhood abuse. Biol Psychiatry. 2002;52:1102–12. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(02)01395-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Heim C, Nemeroff CB. The role of childhood trauma in the neurobiology of mood and anxiety disorders: preclinical and clinical studies. Biol Psychiatry. 2001;49:1023–39. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(01)01157-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Frewen WK. An objective assessment of the unstable bladder of psychosomatic origin. Br J Urol. 1978;50:246–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410x.1978.tb02818.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Macaulay AJ, et al. Micturition and the mind: psychological factors in the aetiology and treatment of urinary symptoms in women. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 1987;294:540–3. doi: 10.1136/bmj.294.6571.540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Risbrough VB, Stein MB. Role of corticotropin releasing factor in anxiety disorders: a translational research perspective. Horm Behav. 2006;50:550–61. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2006.06.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Barry MJ, et al. The American Urological Association symptom index for benign prostatic hyperplasia. The Measurement Committee of the American Urological Association. J Urol. 1992;148:1549–57. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)36966-5. discussion 1564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.O'Leary MP, et al. The interstitial cystitis symptom index and problem index. Urology. 1997;49(5A suppl):58–63. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(99)80333-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Propert K, Landis J. Interstitial cystitis data base. National Insitute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Disease Central Repository; 2005. [Google Scholar]