Abstract

Participants were 443 (52.6% male, 47.4% female) ethnically diverse, 1st-grade, lower achieving readers attending 1 of 3 school districts in Texas. Using latent variable structural equation modeling, the authors tested a theoretical model positing that (a) the quality of teachers’ relationships with students and their parents mediates the associations between children’s background characteristics and teacher-rated classroom engagement and that (b) child classroom engagement, in turn, mediates the associations between student–teacher and parent–teacher relatedness and child achievement the following year. The hypothesized model provided a good fit to the data. African American children and their parents, relative to Hispanic and Caucasian children and their parents, had less supportive relationships with teachers. These differences in relatedness may be implicated in African American children’s lower achievement trajectories in the early grades. Implications of these findings for teacher preparation are discussed.

Keywords: student, teacher relationship, home/school relationship, engagement, achievement, ethnicity

Students’ sense of social relatedness at school is a key construct in contemporary theories of academic motivation and engagement (Connell & Wellborn, 1991; Eccles, Wigfield, & Schiefele, 1998; Stipek, 2002). When students experience a sense of belonging at school and supportive relationships with teachers and classmates, they are motivated to participate actively and appropriately in the life of the classroom (Anderman & Anderman, 1999; Birch & Ladd, 1997; Skinner & Belmont, 1993). Students’ sense of belonging at school has been linked both to engaged versus disaffected school identities and to learning outcomes (Battistich, Solomon, Watson, & Schaps, 1997; Skinner, Zimmer-Gembeck, & Connell, 1998). Although the vast majority of the extant research on social relatedness and engagement has been conducted with students in Grades 3 and higher (for reviews, see Furrer & Skinner, 2003, and Stipek, 2002), recent research suggests that children’s social relatedness in the primary grades may establish patterns of school engagement and motivation that have long-term consequences for their academic motivation and achievement (Hamre & Pianta, 2001; Ladd, Birch, & Buhs, 1999).

Positive relations with teachers in the classroom and between home and school appear to be less common for low-income and racial minority children than for higher income, White students (Entwisle & Alexander, 1988; Hamre & Pianta, 2001; Hill et al., 2004; Kohl, Weissberg, Reynolds, & Kasprow, 1994; Ladd et al., 1999). Furthermore, several researchers have suggested that these early racial and income differences in relatedness may contribute to disparities in achievement (Pianta, Rimm-Kauffman, & Cox, 1999; Pianta & Walsh, 1996). The need to improve the academic achievement among ethnic minority and poor families is one of the most urgent challenges facing education and U.S. society today (Shonkoff & Phillips, 2000). For example, according to the National Assessment of Educational Progress (National Center for Education Statistics, 2005c), in 2005, 41% of White fourth graders were proficient in reading, compared with 13% of Black and 16% of Hispanic students. Results for math were similar, with 47% of White students proficient compared with 13% of Black and 19% of Hispanic students. Of great concern is the fact that racial and income disparities in achievement increase with children’s time in school (The Future of Children, 2005).

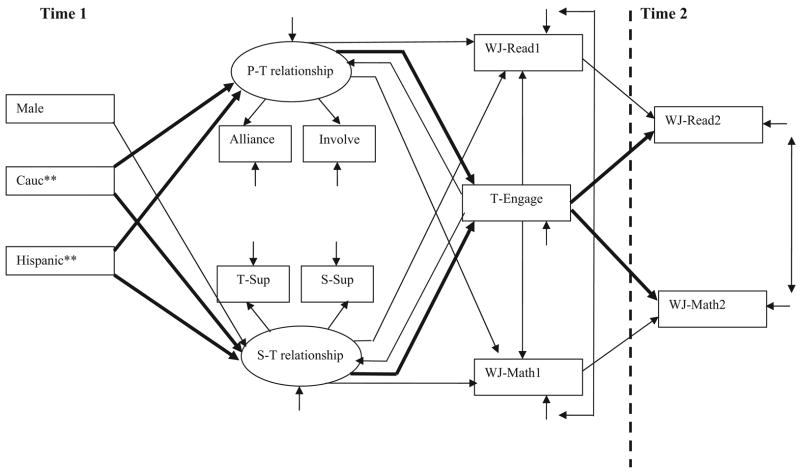

This study tests a model of early school adaptation that integrates research on the centrality of social factors in students’ academic motivation (Connell & Wellborn, 1991; Furrer & Skinner, 2003; Wentzel, 1999) with research on racial and income disparities in achievement. Specifically, our theoretical model, depicted in Figure 1, posits that children’s background characteristics (gender and race–ethnicity) predict the quality of parent–teacher and student–teacher relationships and that the quality of these relationships has consequences for children’s achievement. Furthermore, we expect that children’s classroom engagement in learning activities is one mechanism by which relationship quality in the early grades affects subsequent achievement. In the next sections, we provide the empirical and theoretical support for each link in this complex model. First, we present evidence on gender and racial disparities in student–teacher and parent–teacher relationship quality. Second, we summarize evidence that student–teacher and parent–teacher relationship quality influences children’s academic motivation and engagement. Third, we present evidence to support the premise that student motivation and engagement in classroom learning activities are the proximal processes accounting for the effect of relationship quality on achievement.

Figure 1.

Theoretical model. Bolded arrows indicate the hypothesized mediation effects; there are reciprocal relations between parent–teacher relationship and teacher-perceived engagement and between student–teacher relationship and teacher-perceived engagement. Asterisks indicate variables are dummy coded, with African American students as the reference group. Variables are as follows: Male (male =1, female =0); Caucasian (Cauc; Caucasian =1, others =0); Hispanic (Hispanic =1, others =0); Alliance scale score describing home–school relationship (Alliance); General Parent Involvement scale score describing home–school relationship (Involve); teacher-rated support (T-Sup); peer-rated support (S-Sup); parent–teacher relationship (P-T relationship); student–teacher relationship (S-T relationship); teacher-perceived engagement (T-Engage); Woodcock–Johnson III Broad Reading Test score at Time 1 (WJ-Read1); Woodcock–Johnson III Broad Mathematics Test score at Time 1 (WJ-Math1); Woodcock–Johnson III Broad Reading Test score at Time 2 (WJ-Read2); Woodcock–Johnson III Broad Mathematics Test score at Time 2 (WJ-Math2).

Racial–Ethnic and Gender Differences in Parents’ and Students’ Relationships With Teachers

Multiple factors contribute to the quality of student–teacher and parent–teacher relationships. Not surprising, students who exhibit under-controlled or aggressive behaviors establish relationships with teachers characterized by lower levels of support and acceptance and higher levels of conflict (Birch & Ladd, 1998; Silver, Measelle, Armstrong, & Essex, 2005). Compared with girls, boys’ relationships with teachers are characterized by less closeness and more conflict (Birch & Ladd, 1997, 1998; Saft & Pianta, 2001; Silver et al., 2005), perhaps because boys are less conforming and self-regulated than girls. Of particular interest to this investigation are findings that minority, especially African American, children and children of low socioeconomic status (SES) are less likely than Caucasian or higher SES children to enjoy supportive relationships with teachers (Entwisle & Alexander, 1988; Hamre & Pianta, 2001; Ladd et al., 1999; Wehlage & Rutter, 1986). Although the reasons for these differences are not known, the fact that the teacher workforce in the United States is predominantly Caucasian and middle class may contribute to racial and income differences in teacher–student relationship quality. In 2003–2004, 84% of elementary teachers in the United States were Caucasian (National Center for Education Statistics, 2005a). Conversely, 42% of elementary children in 2003 were part of an ethnic minority (National Center for Education Statistics, 2005b). The ethnic imbalance between teachers and students gains in significance in light of several studies reporting that teacher–child ethnicity match is associated with more positive teacher ratings of closeness (Saft & Pianta, 2001; Zimmerman, Khoury, Vega, Gil, & Warheit, 1995). Perhaps teachers are more attuned to children who share their racial or ethnic background and are, therefore, more accurate in interpreting their behavior and performance and more responsive to their needs (Alexander, Entwisle, & Thompson, 1987; Saft & Pianta, 2001). The finding that African American children experience less supportive relationships with teachers may also be explained by racial differences in behavioral orientation and academic task engagement. Because African American children are less conforming and more active than are Caucasian children at school entrance (Hudley, 1993; Rock & Stenner, 2005), teachers’ interactions with African American students may be characterized by more criticism and less support.

Similarly, minority and low-SES parents experience less positive relationships with teachers and engage in fewer school involvement activities than do Caucasian and higher SES parents (for review, see Boethel, 2003). Teachers perceive ethnic minority parents as engaging in fewer involvement behaviors and as less cooperative than Caucasian parents (Kohl et al., 1994). Teachers and principals tend to attribute lower levels of parent involvement among ethnic minority parents to a lack of motivation to cooperate, a lack of concern for their children’s education, and a lower value placed on education (Clark, 1983; Lopez, 2001). Teachers’ perceptions of and attributions for minority parents’ involvement in their children’s schooling may negatively impact the frequency and quality of their interactions with minority parents.

It is important to note that parents’ perceptions of their own school involvement and educational beliefs and values show low correspondence with teachers’ perceptions of their involvement and beliefs (Epstein, 1984, 1996). Wong and Hughes (in press) found that African American parents report levels of parent involvement that are comparable to or higher than that of Caucasian parents, whereas teachers rate African American parents’ involvement as lower than that of Caucasian parents. Other studies have reported that minority parents endorse attitudes toward education similar to those of Caucasian parents and exhibit levels of involvement in home-based parent involvement activities similar to, if not higher than, those of Caucasian parents (Chavkin & Williams, 1993).

According to Ogbu (1993), parents’ beliefs about appropriate parenting practices and ways to interact with the school vary according to ethnic identity and social class. According to this view, because teachers in the United States are overwhelmingly Caucasian and middle class, misunderstandings of each other’s intentions would be more likely to occur in the context of teacher–parent interactions with minority parents versus Caucasian parents (Lasky, 2000; Ogbu, 1993). Unfortunately, data on the frequency of teacher–parent misunderstandings for matched and mismatched ethnicity dyads are not available. One possible negative consequence of a mismatch between the culture of the school and the culture of the family is a weaker alliance between home and school and lower parent involvement in school, both of which may negatively impact the child’s school adjustment.

Consequences of Relationship Quality for Academic Motivation and Engagement

Student–Teacher Relationships

It is well established that the quality of children’s relationships with their teachers in the early grades has important implications for children’s concurrent and future academic and behavioral adjustment (Howes, Hamilton, & Matheson, 1994; Hughes, Cavell, & Jackson, 1999; Meehan, Hughes, & Cavell, 2003; Pianta, Steinberg, & Rollins, 1995). The association between teacher–student relationship quality and children’s subsequent adjustment holds when previous levels of adjustment are statistically controlled (Hughes, Cavell, & Jackson, 1999; Ladd et al., 1999; Meehan et al., 2003). Furthermore, an effect for teacher–student relationship quality assessed in kindergarten on achievement is found up to 8 years later, controlling for relevant baseline child characteristics (Hamre & Pianta, 2001).

Several studies have reported specific links between teacher–student relationship quality and student engagement (for review, see Furrer & Skinner, 2003). Engagement has been defined in different ways by different investigators, but it most often refers to behavioral engagement as indexed by cooperative participation, conformity to classroom rules and routines, self-directedness, persistence, and effort (Fredricks, Blumenfeld, & Paris, 2004). Students who enjoy a close and supportive relationship with a teacher are more engaged in that they work harder in the classroom, persevere in the face of difficulties, accept teacher direction and criticism, cope better with stress, and attend more to the teacher (M. Little & Kobak, 2003; Midgley, Feldlauffer, & Eccles, 1989; Ridley, McWilliam, & Oates, 2000; Skinner & Belmont, 1993; Wentzel, 1999). These findings hold when relationship quality is assessed by the teacher (Birch & Ladd, 1997, 1998), the student (Battistich et al., 1997; Marks, 2000; Skinner & Belmont, 1993), or observers (Ladd et al., 1999).

Given teachers’ preference for students who are conscientious, conforming, and self-regulated, it is not surprising that the relationship between engagement and teacher–student relationship quality appears to be reciprocal (Ladd et al., 1999; Skinner & Belmont, 1993). Thus, children with lower school readiness competencies are less likely to receive the teacher support that might enhance their adaptive classroom engagement and learning. Furthermore, those children who are most at-risk for school failure on the basis of level of behavioral adjustment, quality of parenting, low SES, or ethnic minority status are most affected by the quality of their relationships with teachers (Hamre & Pianta, 2001; Silver et al., 2005). For example, Burchinal, Peisner-Feinberg, Pianta, and Howes (2002) found that supportive student–teacher relationships were more predictive of reading skills for African American than for Caucasian students. In a sample of children of poor single parents, Brody, Dorsey, Forehand, and Armistead (2002) found that the quality of children’s classroom experiences served a stabilizing–protective function for children whose home environments were compromised.

Parent–Teacher Relationships

The parent–teacher relationship is also implicated in children’s early school adjustment. Generally, when parents participate in their children’s education, both at home and at school, and experience relationships with teachers characterized by mutuality, warmth, and respect, students achieve more, demonstrate increased achievement motivation, and exhibit higher levels of emotional, social, and behavioral adjustment (Fan & Chen, 2001; Henderson & Mapp, 2002; Marcon, 1999; Reynolds, 1991). Several researchers have distinguished between parent involvement behaviors or activities and the quality of the parent–teacher relationship (Kohl, Lengua, & McMahon, 2000; Rimm-Kaufman, La Paro, Downer, & Pianta, 2005; Vickers & Minke, 1995). Parent involvement behaviors include volunteering at school, communicating with the teacher, attending school functions, and assisting with homework. Parent–teacher relationship quality refers to the affective quality of the home–school connection, as indexed by trust, mutuality, affiliation, support, shared values, and shared expectations and beliefs about each other and the child (Vickers & Minke, 1995). Numerous studies with samples differing in ethnicity and income have demonstrated that both of these dimensions of the home–school mesosystem are associated with student academic engagement and achievement (Boethel, 2003). For example, Rimm-Kaufman et al. (2005) found that kindergarten teachers’ reports of parents’ attitudes toward education predicted child participation and engagement after accounting for SES and maternal sensitivity.

Classroom Engagement and Achievement

Not surprising, children who are actively engaged in classroom learning activities as indexed by effort, persistence, attention, and cooperative participation achieve at a higher level (for review, see Wigfield & Eccles, 2000). Fredricks et al. (2004) reviewed empirical evidence demonstrating that each of three types of student engagement (i.e., behavioral, emotional, and cognitive) is associated concurrently and prospectively with students’ achievement in elementary, middle, and high school grades. For example, the Beginning School Study found that teachers’ ratings of behavioral engagement in the first grade predicted achievement test score gains 4 years later as well as decisions to drop out of school (Alexander, Entwisle, & Horsey, 1997). Pianta (2006) has suggested that engagement is the proximal factor that accounts for the longitudinal effect of teacher–student relationship quality. In support of this view, Ladd et al. (1999) reported that negative patterns of classroom participation (e.g., failure to follow classroom rules, not accepting the teacher’s authority) in kindergarten mediated the association between conflict in the student–teacher relationship and achievement.

Teacher support is best considered a component of the classroom context that interacts with other aspects of the context in exerting its influence on student engagement. Among the other contextual features of classrooms known to influence student engagement are classroom goal structure (for review, see Urdan & Midgley, 2003), classroom task structures (Simpson & Rosenholtz, 1986), teacher frame of reference (Marsh & Craven, 2002), and peer acceptance (Ladd et al., 1999). Consistent with a transactional theory (Sameroff, 1975) perspective, these classroom processes are expected to exert their influence via reciprocal causal processes.

Purpose of This Study

The purpose of this study was to examine the associations between student background variables, the quality of early school relationships (i.e., student–teacher and parent–teacher relationships), and changes across academic years in measured academic ability in a diverse sample of first-grade children at risk for school difficulties because of relatively low literacy skills. Specifically, we tested a theoretical model positing that (a) student ethnicity and gender predict measures of parent–teacher and student–teacher relationship quality and that (b) measures of relationship quality indirectly affect cross-year changes in children’s achievement via their direct effect on child classroom engagement (see Figure 1). On the basis of Skinner and Belmont (1993) and Ladd et al. (1999), we expected the association between teacher support and student engagement to be reciprocal.

Method

Participants

Participants were 443 (52.6% male, 47.4% female) first-grade children attending one of three school districts (1 urban, 2 small city) in southeast and central Texas, drawn from a larger (N =742) sample of African American (N =182), Caucasian (N =267), and Hispanic (N =293) children participating in a longitudinal study examining the impact of grade retention on academic achievement. Participants were recruited across two sequential cohorts in first grade during the fall of 2001 and 2002. Children were eligible to participate in the longitudinal study if they (a) scored below the median score on a state-approved, district-administered measure of literacy administered in either May of kindergarten or September of first grade and (b) had not been previously retained in first grade. Of 1,374 children who were eligible to participate in the larger study, 1,316 were classified by the school district as African American, Caucasian, or Hispanic, a criterion for inclusion in this study. Written parental consent for study inclusion was obtained for 742 (56.3%) of these children. Children with and without consent to participate did not differ on age, gender, ethnic status, bilingual class placement, eligibility for free or reduced lunch, or literacy test scores.

A total of 443 (59.7%) participants (ethnic composition was 104 African American, 176 Hispanic, and 163 Caucasian) had complete data on teacher questionnaires, peer sociometric ratings, and an individually administered test of academic achievement given in Year 1 and 1 year later. Children with and without complete data did not differ on any demographic variables or study variables at baseline, with one exception. Children with complete data had higher scores on a standardized measure of reading achievement (η2 =.009, p =.01). At entrance to first grade, children’s mean age was 6.05 (SD =0.63) years. Children’s mean score for intelligence as measured with the Universal Nonverbal Intelligence Test (Bracken & McCallum, 1998) was 93.18 (SD =14.01). Participants’ age-standard scores on the Woodcock–Johnson III Broad Reading and Broad Mathematics tests (Woodcock, McGrew, & Mather, 2001) at Time 1 were 97.41 (SD =17.97) and 101.19 (SD =13.48), respectively. On the basis of family income, 62.1% of participants were eligible for free or reduced lunch. For 34.6%, the highest educational level in the household was a high school certificate or less. The ethnic composition for the 133 teachers (92.6% female, 7.4% male) completing the teacher questionnaires was 85.7% Caucasian, 10.3% Hispanic, 1.6% African-American, and 1.6% other. The mean years of teaching experience was 4.33 (SD =1.78), and 97.0% of teachers held teacher certification (3.0% held provisional or alternative certification). All teachers had at least a bachelor’s degree; 27.0% had taken some graduate work but did not obtain a master’s degree; and 18.0% held a master’s degree or higher.

Design Overview

During the months of November through March of Year 1, when study participants were in first grade, research staff individually administered tests of reading and math achievement. These tests were readministered the next school year.1 In March of Year 1, teachers were mailed a questionnaire packet for each study participant. This packet included the measures of the teacher’s perception of student–teacher support, parent–teacher alliance, parent involvement in school, and the child’s academic ability. Teachers received $25.00 for completing and returning the questionnaires. Classmates’ perceptions of the level of student–teacher support were obtained via individual interviews conducted between February and May of Year 1.

Measures

Academic achievement

The Woodcock–Johnson III (WJ-III) Tests of Achievement (Woodcock et al., 2001) is an individually administered measure of academic achievement for individuals ages 2 to adulthood. For our purposes, we used the WJ-III Broad Reading W scores (Letter–Word Identification, Reading Fluency, Passage Comprehension subtests) and the WJ-III Broad Mathematics W scores (Calculations, Math Fluency, and Math Calculation Skills subtests). Broad Reading and Broad Mathematics W scores are based on the Rasch measurement model, yielding an equal interval scale, which facilitates modeling growth in the underlying latent achievement. Extensive research documents the reliability and construct validity of the WJ-III and its predecessor (Woodcock, & Johnson, 1989; Woodcock et al., 2001). The 1-year stability for this age group ranges from .92 to .94 (Woodcock et al., 2001).

The Batería Woodcock–Muñoz: Pruebas de Aprovechamiento—Revisada (Batería–R; Woodcock & Muñoz-Sandoval, 1996) is the comparable Spanish version of the Woodcock–Johnson Psycho-Educational Battery—Revised (WJ–R; Woodcock & Johnson, 1989), the precursor of the WJ-III. If children or their parents spoke any Spanish, children were administered the Woodcock–Muñoz Language Survey (Woodcock & Muñoz-Sandoval, 1993) to determine the child’s language proficiency in English and Spanish and selection of either the WJ-III or the Batería–R. The Woodcock Compuscore program (Woodcock & Muñoz-Sandoval, 2001) yields W scores for the Batería–R that are comparable to W scores on the WJ–R. The Broad Reading and Broad Mathematics W scores were used in this study.

Child engagement

Child engagement was measured by a teacher-report, 10-item scale comprising 8 items from the Conscientious scale of the Big Five Inventory (BFI; John & Srivastava, 1999) and 2 items taken from the Social Competence Scale (Conduct Problems Prevention Research Group, 2004) that were consistent with our definition of classroom engagement (effort, attention, persistence, and cooperative participation in learning). Although the Big Five Inventory is conceptualized as a measure of personality traits, the selected items from the Conscientious scale are similar to items used by other researchers to assess classroom engagement (Ladd et al., 1999; Ridley et al., 2000). Example items are “Is a reliable worker,” “Perseveres until the task is finished,” “Tends to be lazy” (reverse scored), and “Is easily distracted.” The two items from the Social Competence Scale were “Sets and works toward goals” and “Turns in homework.” Items are rated on a 1–5 Likert-type scale. The internal consistency of these 10 items for our sample was .95.

Teacher perception of student–teacher support

The 22-item Teacher Relationship Inventory (TRI; Hughes, Cavell, & Willson, 2001) is based on the Network of Relationships Inventory (Buhrmester & Furman, 1987). Teachers indicate on a 5-point Likert-type scale their level of support (16 items) or conflict (6 items) in their relationships with individual students. An exploratory factor analysis on 335 first-grade participants from the first cohort of the larger study suggested three factors: Support (13 items), Intimacy (3 items), and Conflict (6 items). Results of confirmatory factor analysis on 449 participants from the second cohort of the larger study found that the three-factor model provided an adequate fit for the data, χ2(204) =697.803, p <.001, comparative fit index (CFI) =.92, root-mean-square error of approximation (RMSEA) =.074. Furthermore, the null hypothesis of factor invariance across cohorts and times could be retained at the .01 level. Because the Intimacy and Support scales were moderately correlated (.43) and both assess positive relatedness, a total Support score was computed as the mean item score on these 16 items. The internal consistency was .92 for the Support score and .94 for the Conflict score. Example Support scale items include “I enjoy being with this child,” “This child gives me many opportunities to praise him or her,” “I find I am able to nurture this child,” and “This child talks to me about things he/she doesn’t want others to know.” In a previous study with second- and third-grade children, TRI Support scores correlated moderately with teachers’ reports of student–teacher relational conflict (r =− .56) and with peer nominations of student–teacher relationship support (r =.53; Hughes, Yoon, & Cavell, 1999). In a longitudinal study of behaviorally at-risk elementary students, the TRI Support score predicted changes in behavioral adjustment and peer relationships (Meehan et al., 2003).

We used only the Support scale, based on Hughes’s (Hughes, Cavell, & Jackson, 1999; Hughes et al., 2001) and others’ (Birch & Ladd, 1998; Silver et al., 2005) findings that teachers’ reports of relational conflict are difficult to discriminate from their reports of child conduct problems. Silver et al. (2005) suggested that teacher reports of conflict in the teacher–child relationship may reflect child-driven effects on teachers’ interpretations of relationships, whereas teacher reports of closeness may be “more representative of a teacher’s ability to foster trust and warmth with a child” (p. 54).

Teacher perception of parent–teacher relationship

We developed the teacher-report home–school relationship questionnaire to assess parent involvement in education. The measure was initially derived from a pool of 28 items rated on a 1–5 scale. Twenty-one items were adapted from the Parent–Teacher Involvement Questionnaire—Teacher-Report (Kohl et al., 2000), and 7 items were adapted from the teacher version of the Joining scale of the Parent–Teacher Relationship Scale (Vickers & Minke, 1995). An exploratory factor analysis based on the teachers of 311 first-grade children in the first cohort participating in the larger study yielded a three-factor solution that accounted for 57.3% of the variance. The three factors were Alliance (8 items, α=.93; sample item: “I can talk and be heard by this parent”), General Parent Involvement (8 items, α=.75; sample item: “How often does this parent ask questions or make suggestions about his/her child?”), and Teacher Initiation (4 items, α=.66; sample item: “How often do you tell this parent when you are concerned?”). A confirmatory factor analysis on a second sample of 296 first-grade children in the second cohort found that the three-factor model provided an adequate fit for the data, χ2(167) =394.38, p<.001, CFI =.94, RMSEA =.07. Furthermore, the factor structure was invariant across Year 1 and Year 2, Δχ 2(20) =27, p =.135. Because the Teacher Initiative scale assesses a teacher’s involvement behaviors toward parents in general rather than a teacher’s relationships with individual parents, only the Alliance and General Parent Involvement scales were used in this study.

Peer nominations of teacher–student support

A modified version of the Class Play (Masten, Morison, & Pellegrini, 1985) and a roster rating of liking for classmates were used to obtain children’s evaluations of the provision of teacher support to children. Research assistants individually interviewed children at school. Children were asked to nominate as few or as many classmates as they wished who could best play each of several parts in a class play. Of interest to this study is the item “These children get along well with their teachers. They like to talk to their teachers, and their teachers enjoy spending time with them. What kids in your class are like this?” Each classmate receives a student–teacher support score based on the number of nominations that child receives. Sociometric scores were standardized within classrooms. Elementary children’s peer nomination scores derived from procedures similar to those used in this study have been found to be stable over periods from 6 weeks to 4 years and to be associated with concurrent and future behavior and adjustment (for review, see Hughes, 1990). Because reliable and valid sociometric data can be collected through the use of the unlimited nomination approach when as few as 40% of children in a classroom participate (Terry, 1999), sociometric scores were computed only for children located in classrooms in which more than 40% of classmates participated in the sociometric assessment. A total of 182 of 784 children were eliminated from the study because of missing sociometric data. The mean rate of classmate participation in sociometric administrations was .65 (range =.40–.95).

Results

The hypothesized model is shown in Figure 1. The bolded arrows indicate the hypothesized mediation effects, which involve the parent–teacher relationship and the student–teacher relationship constructs and teacher-rated child engagement as mediators. Table 1 presents the correlations between all continuous variables in the theoretical model.

Table 1.

Zero-Order Correlations for All Continuous Variables in the Theoretical Model

| Scale | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Alliance | — | ||||||||

| 2. Involve | .48 | — | |||||||

| 3. T-Sup | .50 | .29 | — | ||||||

| 4. S-Sup | .24 | .16 | .29 | — | |||||

| 5. T-Engage | .46 | .23 | .59 | .28 | — | ||||

| 6. WJ-Read1 | .25 | .25 | .20 | .08 | .36 | — | |||

| 7. WJ-Math1 | .07 | .09 | .06 | .07 | .13 | .28 | — | ||

| 8. WJ-Read2 | .26 | .23 | .21 | .00 | .36 | .72 | .17 | — | |

| 9. WJ-Math2 | .09 | .09 | .05 | 3.01 | .18 | .19 | .66 | .31 | — |

| M | 4.03 | 2.17 | 30.08 | 3.71 | 3.24 | 435.60 | 463.20 | 462.80 | 476.20 |

| SD | 0.76 | 0.50 | 0.91 | 0.76 | 1.04 | 26.05 | 12.72 | 21.34 | 10.26 |

Note. N =443. Correlations (absolute value) equal to or larger than .08 are significant at p<.05 (one-tailed); correlations (absolute value) equal to or larger than .12 are significant at p<.01 (one-tailed). The Woodcock–Johnson scores are W scores; the more interpretable corresponding reading and math age-standard scores are 97.41 (SD =17.97) and 101.19 (SD =13.48), respectively. Alliance =Alliance scale measuring home–school relationship; Involve =General Parent Involvement scale measuring home–school relationship; T-Sup =teacher-rated support; S-Sup =peer-rated support; T-Engage =teacher-perceived engagement; WJ-Read1 =Woodcock–Johnson III Broad Reading Test at Time 1; WJ-Math1 =Woodcock–Johnson III Broad Mathematics Test at Time 1; WJ-Read2 =Woodcock–Johnson III Broad Reading Test at Time 2; WJ-Math2 =Woodcock–Johnson III Broad Mathematics Test at Time 2.

The theoretical structural model was examined by using maximum likelihood estimation with robust standard errors and a mean-adjusted chi-square statistic test (MLR; Muthén & Muthén, 2004). To account for the dependency among the observations (students) within clusters (classrooms), we conducted analyses using the complex analysis feature in Mplus (Version 3.13, Muthén & Muthén, 2004), which accounts for the nested structure of the data by adjusting the standard errors of the estimated coefficients. The use of multiple reporters and methods to measure relationship constructs reduces potential bias due to a shared method of measurement or reporter between the predictor (i.e., relationship constructs) and predicted (i.e., engagement) variables (Bank, Dishion, Skinner, & Patterson, 1990).

The hypothesized model included only indirect effects of gender and ethnicity on Time 1 engagement and on reading and math at Time 1 and Time 2. The original theoretical model was analyzed and the mediation-related path coefficients were all significant, but the overall model fit was not fully satisfactory. To improve the overall model fit, we modified the model by adding the direct paths from the ethnic contrasts to engagement and to Time 1 reading and Time 1 math and the direct paths from gender to engagement and both Time 1 and Time 2 math. These modifications are consistent with a model positing both indirect and direct effects of background variables on academic engagement and achievement. Because the modifications were theoretically tenable and improved fit, they were incorporated into the revised model. The residual variances between the teacher-reported home–school relationship variables and teacher-rated support were allowed to correlate because these measures are completed by the same source, and allowing the errors to correlate significantly improved model fit (Bentler, 2000).

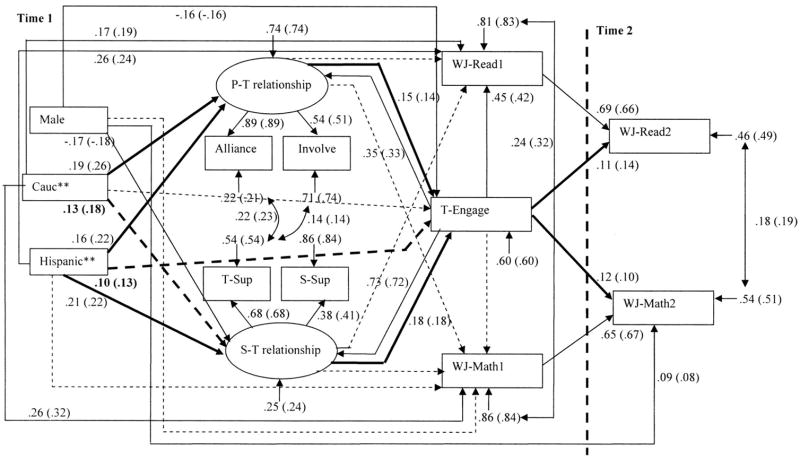

The revised model provided an adequate fit to the data, χ2(29) =73.20, p<.001, CFI =.96, RMSEA =.059, standardized root-mean-square residual =.062. All bolded paths related to the hypothesized mediation effects were significant (at p <.05), except the effect of the ethnicity contrast between Caucasian and African American students on student–teacher relationship (γ =.13, p =.08). To address the missingness, we also analyzed the modified model with the full data (i.e., N =742) using the full information maximum likelihood (FIML) method under Mplus, which applies the expectation maximization algorithm described in R. J. A. Little and Rubin (1987). We found a very similar pattern of results (i.e., coefficients presented in parentheses in Figure 2). With the full data, all hypothesized mediation-related path coefficients were significant, including the effect of the ethnicity contrast between Caucasian and African American students on student–teacher relationship (γ=.18, p<.05, R2 =.03). The significant result of this effect based on the full data implies that the nonsignificant effect of the Caucasian contrast on student–teacher relationship from the analysis using the sample with complete data (N =443) may be due to insufficient statistical power.

Figure 2.

Modified theoretical model with the relationship constructs and teacher-perceived engagement as mediators (adjusted for dependency).χ2(29) =73.20, p<.001; comparative fit index =.96; root-mean-square error of approximation =.059; standardized root-mean-square residual =.062. To reduce the complexity of the figure, we included only coefficients significant at p<.05. All coefficients are standardized (N =443). Coefficients in parentheses are based on the full information maximum likelihood (FIML) procedure with full data (N =742). The dashed paths indicate nonsignificant effects. The bolded dashed paths indicate inconsistent findings between the complete data (N =443) and the full data using the FIML procedure (N =742); for example, the path coefficient from Caucasian to student–teacher relationship was nonsignificant ( p<.10) for the complete data (N =443) but significant ( p<.05) for the full data (N =742). Asterisks indicate variables are dummy coded, with African American students as the reference group. See Figure 1 caption for details on variables.

Because ethnicity was dummy coded, with African American students as the reference group, the positive effects of the ethnicity variables on both relationship constructs indicated that both Caucasian and Hispanic students had higher scores on both relationship constructs than did African American students (although the effect for the ethnicity contrast between Caucasian and African American students was significant only with the full data). Moreover, the positive effects of both relationship constructs on teacher-rated child engagement indicated that both relationship constructs are associated with higher child engagement. In turn, child engagement had a substantial and positive longitudinal impact on students’ academic performances measured the following year after controlling for the previous academic performances. This analysis was also repeated on a smaller subsample with family SES data (N =227), and a similar pattern of results was found (i.e., significant effects of the ethnicity contrasts on the relationship constructs after controlling for family SES).

According to Baron and Kenny’s (1986) procedure (see also Kenny, Kashy, & Bolger, 1998, for more updated information), the first step in testing the mediation effect is to establish a significant relation between the predictor and outcome variables, although this is not a rigidly required step (MacKinnon, Krull, & Lockwood, 2000; MacKinnon, Lockwood, Hoffman, West, & Sheets, 2002; Shrout & Bolger, 2002).2 The second and third steps, respectively, are to establish a significant relation between the predictor and mediator variables and a significant relation between the mediator and outcome variables. The final step involves testing the significance of the mediated effect. The mediated effect is tested by multiplying the path coefficients from Steps 2 and 3. A significant mediated effect suggests that the mediator partially or fully explains the relation between the predictor and outcome. According to Kenny et al.’s (1998) procedure, the mediation effects can be tested by multiplying the nonstandardized path coefficients corresponding to the mediation effects. Sobel’s (1982) test of mediation effects (i.e., ) along with the delta method standard error (i.e., ) was used (Krull & MacKinnon, 1999, 2001).

Following Baron and Kenny’s (1986) steps, a structural model with proximal direct relations (or cross-sectional relations) between the ethnicity contrasts and engagement was examined. All the ethnicity contrasts had significant direct effects on teacher-perceived engagement (Caucasian contrast on teacher-perceived engagement: γ=.14, p<.05; Hispanic contrast on teacher-perceived engagement: γ=.19, p<.05). On the other hand, the distal direct effects (or longitudinal direct effects) of both relationship constructs on the WJ-III Reading and Math scores measured in the following year after controlling for the previous year WJ-III Reading and Math scores were not significant. Shrout and Bolger (2002) suggested skipping Baron and Kenny’s (1986) first step especially when examining mediation of distal effects, which can reduce the risk of increasing the Type II error on testing the whole mediation system. Hence, we proceeded to the second and third steps and examined the hypothesized longitudinal mediation effects.

For Steps 2 and 3, all path coefficients related to the hypothesized mediation effects as shown in Figure 2 were significant (at p<.05). The tests of all hypothesized mediation effects are summarized in Table 2. The results presented in Table 2 indicate that both relationship constructs significantly mediated the relations between the ethnicity contrasts and engagement. Similarly, engagement significantly mediated the longitudinal relations between both relationship constructs and the WJ-III Reading and Math scores in the following year after controlling for the previous WJ-III Reading and Math scores. For the parent–teacher relationship, 4.1% of the variance was explained by the ethnicity contrasts. Similarly, 5.9% of the total variance of the student–teacher relationship was accounted for by the ethnicity contrasts. For teacher-rated child engagement, 35.0% of the total variance was explained by both relationship constructs. Nevertheless, 2.0% of the total variance of the WJ-III Reading score and 1.0% of the total variance of the WJ-III Math score were solely explained by teacher-rated child engagement in the following year after controlling for the corresponding scores measured in the previous year.

Table 2.

Tests of Hypothesized Mediation Effects (N =443)

| Path | α̂ | Path | β̂ | Mediation effect (α̂× β̂) | SEα̂ | SEβ̂ | SEα̂× β̂ | Zα̂× β̂ | p (one-tailed) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mediation effects between ethnicity and engagement, with relationship constructs as the mediators | |||||||||

| Cauc →PT | .266 | PT → Engage | .228 | .061a | .111 | .032 | .027b | 2.259c | .012 |

| Hispan →PT | .213 | PT → Engage | .228 | .049 | .100 | .032 | .024 | 2.041 | .021 |

| Cauc →ST | .142 | ST → Engage | .360 | .051 | .082 | .028 | .030 | 1.700 | .045 |

| Hispan →ST | .221 | ST → Engage | .360 | .080 | .075 | .028 | .028 | 2.857 | .002 |

| Mediation effects between relationship constructs and academic performances, with engagement as the mediator | |||||||||

| PT → Engage | .228 | Engage → Read | .023 | .005 | .032 | .008 | .002 | 2.500 | .006 |

| ST → Engage | .360 | Engage → Read | .023 | .008 | .028 | .008 | .003 | 2.667 | .004 |

| PT → Engage | .228 | Engage → Math | .011 | .003 | .032 | .004 | .001 | 3.000 | .001 |

| ST → Engage | .360 | Engage → Math | .011 | .004 | .028 | .004 | .002 | 2.000 | .023 |

Note. Path coefficients α̂ and β̂ are nonstandardized. Delta method ; Hispan =Hispanic contrast; PT =parent–teacher relationship; ST =student–teacher relationship; Engage =teacher-perceived engagement; Read =Woodcock–Johnson III Broad Reading Test score (following year score controlled for the previous year score); Math =Woodcock–Johnson III Broad Mathematics Test score (following year score controlled for the previous year score).

Mediation effect between Caucasian, parent–teacher relationship, and teacher-perceived engagement= (.266) × (.228) = .061.

.

Zα̂ × β̂ = 061/.027 = 2.259.

Moreover, we examined the possible gender and ethnic differences on the mediation effects of engagement on the relations between the relationship constructs and the second year WJ-III Reading and Math scores based on the modified model. Because of the use of a robust estimator, the Satorra–Bentler adjusted chi-square difference test (Satorra, 2000) was adopted to examine the possible group difference on the mediation effects. None of the adjusted chi-square difference tests was significant, indicating that all the mediation effects were invariant across different gender and ethnic groups.

Discussion

Support for Effect of Relationship Quality on Achievement

Consistent with the central role of social relatedness in students’ academic motivation and performance, early elementary students gain more in achievement when they and their parents experience supportive relationships with teachers. Furthermore, the effect of student–teacher and parent–teacher relationship quality in first grade on achievement the following year is indirect, via child classroom engagement. Achievement was measured with an individually administered and psychometrically sound measure of reading and math achievement in Year 1 and 1 year later. Thus, results cannot be explained by shared method in measuring relationship variables and achievement. The finding that relationship and engagement variables predict measured academic achievement the following year, when controlling for Year 1 achievement, although expected, is noteworthy given the stability of achievement from Year 1 to Year 2.

This study makes an important contribution to the literature by demonstrating that student–teacher and parent–teacher relationship quality make unique contributions to children’s engagement and achievement in the early grades. The study is the first to use a prospective design to test the effects of relationship quality on achievement in the early grades, controlling for baseline achievement, and to test the processes that account for the effect of relationship quality on achievement. Thus, these findings add to the rapidly accumulating evidence that social relatedness is critical to children’s engagement and academic success or, conversely, to disaffection and failure.

Whereas we found a concurrent effect of engagement on reading achievement, we did not find an effect on math achievement. The difference may be due to the fact that reading and literacy instruction consumes approximately twice the amount of classroom time in these first-grade classrooms as math instruction does. Thus, there may be more opportunities for student effort and attention to influence reading outcomes than math outcomes.

It was important to determine whether the ethnicity contrasts would predict relationship variables if SES were included in the model. Unfortunately, SES was available for only 227 of the 443 participants. According to the results from the subsample with SES data (N =227), the effects of the ethnicity contrasts on the relationship constructs were still significant ( p<.05) after controlling for SES. In addition, SES had a significant effect on the parent–teacher relationship (b =.35, p<.05) but not on the student–teacher relationship.

Racial Differences in Relational Supports

Of importance, our results suggest that African American children and their parents are less likely to experience home–school relationships and student–teacher relationships that support children’s achievement. Positive connections between parents and teachers constitute social capital, defined as “a task specific construct that relates to the shared expectations and mutual engagement by adults in the active support and social control of children” (Sampson, Morenoff, & Earls, 1999, p. 635). Future research should address factors that contribute to these differences.

Several possibilities may explain the lower teacher relationship quality of African American students and their parents. First, African American children in the early grades exhibit more under-controlled behavior and have more active and assertive interactional styles, a finding that has been replicated across different assessment sources and methods (Hudley, 1993). Both African American teachers and Caucasian teachers rate African American students as having more behavioral difficulties (Alexander, Entwisle, & Thompson, 1987; Pigott & Cowen, 2000). In our sample, African American children had significantly higher standardized peer nomination scores for aggressive behaviors (N =127, M =0.36, SD =1.19) than did either Caucasian (N =215, M =−0.03, SD =0.87) or Hispanic (N =230, M =−0.10, SD =0.93) children. Through a transactional process, initial differences in African American children’s behavioral styles may contribute to less satisfactory connections across home and school and within the classroom, which lead to diminished academic motivation and engagement.

Differences in the parenting practices, communication styles, and educational beliefs between teachers and African American parents are a second possibility for lower teacher relatedness for African American students and parents. When parties do not share a common culture, it is more difficult to establish shared understanding and to build trust. Supporting this interpretation is the finding that ethnic congruence between teachers and students is associated with higher teacher ratings of closeness and lower ratings of student conflict and dependency (Saft & Pianta, 2001).

Third, some researchers report that African American parents communicate more frequently with teachers and are more likely to criticize teachers and the school than are Hispanic parents, who are more deferential (Ritter, Mont-Reynaud, & Dornbusch, 1993). Teachers may be less comfortable with and accepting of the more assertive approach of African American parents relative to the more deferential style of Hispanic parents.

Fourth, teachers may endorse ethnic or racial stereotypes about children, which may influence their feelings toward students and their parents and lead to behavioral self-fulfilling prophecies (Babad, 1992; Jussim, 1986). Previous studies have found that teachers are less accurate in rating minority children’s academic ability than the ability of Caucasian children and react differently to the same behaviors exhibited by African American and Caucasian children (Alexander et al., 1987; Murray, 1996; Partenio & Taylor, 1985). Teachers in our sample may have expected less collaborative or more strained relationships with African American parents and students. These expectations may have resulted in fewer or less warm interactions with students and parents, which, in turn, led to lower levels of parent involvement and student classroom engagement.

Regardless of the reasons for the relationship gap, these findings are of great concern. A recent research synthesis on school readiness (The Future of Children, 2005) reported that about one half of the test score gap between African American and Caucasian high school students is evident when children start school. Our results suggest that, rather than leveling the playing field, early social experiences in school may contribute to widening racial disparities in educational attainment.

Study Limitations and Future Directions

These findings need to be interpreted in the context of study limitations. Because participants were selected on the basis of scoring below average on a test of early literacy, our findings may not generalize to higher achieving students. Because three of the four measures of relationship constructs were completed by the teacher, who also completed ratings of child engagement, shared source may account for some of the association found between the relationship constructs and child engagement. Because measures of relationship quality and measures of engagement were taken at one point in time, alternative explanations for the associations cannot be ruled out. Three waves of data are necessary to provide strong support for mediational models (Cole & Maxwell, 2003). Additional waves of data would also address whether an effect for relationship constructs in first grade continues beyond the following year.

It is likely that reciprocal causal processes among engagement, achievement, and relationship variables are at play in children’s early school achievement. On the basis of previous research (Ladd et al., 1999; Skinner & Belmont, 1993), the hypothesized model included the reciprocal effect of teacher-rated engagement on the parent–teacher and student–teacher relationship. Additional reciprocal effects may also be at play. For example, it is likely that children’s academic competencies at school entrance affect and are affected by their patterns of classroom engagement (Miles & Stipek, 2006; Skinner et al., 1998; Trzesniewski, Moffitt, Caspi, Taylor, & Maughan, 2006). Similarly, children who enter school with greater academic competencies may elicit more positive responses from teachers, which, in turn, impacts their achievement. Studies that include measures of achievement, engagement, and relationship quality at a minimum of two time points are necessary to provide a stronger basis for testing reciprocal causal processes.

Finally, observational measures of student–teacher and parent–teacher interactions as well as child engagement are needed to locate more precisely the processes that account for the observed effects. The teacher rating of engagement covers several specific processes that may account for why engagement mediated the association between relationship constructs and achievement. Perhaps students who experience supportive relationships with teachers try harder (follow the rules, do their homework, listen to the teacher), or perhaps they are better able to cope with classroom stressors and, therefore, better able to concentrate on assignments and to attend to instruction.

An additional limitation of the study is the lack of sufficient racial and ethnic diversity among the teachers to investigate whether these findings might be moderated by student–teacher ethnic or racial match. Saft and Pianta (2001) found that teachers rated relationships with children whose ethnicity matched theirs as closer and less conflicted than relationships with children whose ethnicity was different from theirs. With only 6 African American children taught by African American teachers, we were unable to investigate the role of ethnic congruence on teacher perceptions of relationship constructs and child ability.

Implications for School Practices

Schools’ efforts to enhance home–school relationships focus almost exclusively on increasing parents’ involvement (Brooks-Gunn & Markman, 2005), to the neglect of enhancing the affective quality of home–school relationships. Researchers who have included measures of relationship quality as well as involvement behaviors have reported stronger effects for measures of relationship quality than for measures of parent school involvement behaviors (Hughes, Gleason, & Zhang, 2005; Kohl et al., 1994; Rimm-Kaufman, Pianta, Cox, & Bradley, 2003). Our findings emphasize the importance of improving the quality of the home–school relationship, especially for African American and low-income families.

If results of this study are replicated in new samples, they would have implications for teacher preparation and teacher professional development. Teachers receive very little or no preparation in building successful alliances with parents or supportive and warm relationships with students. In a national study of 3,595 kindergarten teachers, Early, Pianta, Taylor, and Cox (2001) found that although teachers were unlikely to receive training in building home–school connections, those who did were much more likely to use all types of strategies to promote a successful transition to school, including making personal contacts with parents. In a synthesis of the literature on early home–school connection, Boethel (2003) reported that the most individualized, relationship-building activities tend to be the least used and that urban schools and schools serving more minority children were least likely to use higher intensity contacts. Our findings suggest that an increased focus on helping teachers connect with students and their parents is one means of helping children at risk for academic failure get off to a good start in school.

Footnotes

The varying test times were primarily a result of insufficient manpower to assess all participants within a shorter window of time each year. Thus, children in some classrooms and schools were tested earlier than children in other classrooms and schools. The average interval between the two testing occasions was 341 (SD =74) days. Compared with ordinary least squares regression, which assumes independent observations, the robust estimation method (multiple linear regression) under Mplus can take into account the nesting structure in our data (i.e., the potential dependent responses between students from the same classroom) by adjusting the standard errors of the unbiased estimates. To investigate whether the interval between the two testing occasions might have affected the results, we split the sample into two groups based on the interval between Time 1 and Time 2 administrations of the achievement tests. Using the mixed-analysis procedure under SPSS (with Bonferroni correction for p values), we found no statistically significant correlation between test interval and the 13 variables in the tested model. Thus, we concluded that test interval did not have a significant effect on the obtained results.

Several studies (MacKinnon et al., 2000; MacKinnon et al., 2002; Shrout & Bolger, 2002) have indicated that the first step of Baron and Kenny’s (1986) procedure (i.e., testing the direct effect) is not necessary because this test may not be significant under certain circumstances, such as the examination of distal mediation effects or the presence of suppression effects. Keeping this restricted step may eventually result in risking a Type II error of testing the full mediation system (Shrout & Bolger, 2002).

References

- Alexander KL, Entwisle DR, Horsey CS. From first grade forward: Early foundations of high school dropout. Sociology of Education. 1997;70:87–107. [Google Scholar]

- Alexander KL, Entwisle DR, Thompson MS. School performance, status relations, and the structure of sentiment: Bringing the teacher back in. American Sociological Review. 1987;52:665–682. [Google Scholar]

- Anderman LH, Anderman EM. Social predictors of changes in students’ achievement goal orientations. Contemporary Educational Psychology. 1999;24(10):21–37. doi: 10.1006/ceps.1998.0978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babad E. Teacher expectancies and nonverbal behavior. In: Feldman RS, editor. Applications of nonverbal behavioral theories and research. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum; 1992. pp. 167–190. [Google Scholar]

- Bank L, Dishion TJ, Skinner M, Patterson GR. Method variance in structural equation modeling: Living with “glop”. In: Patterson GR, editor. Depression and aggression in family interaction: Advances in family research. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum; 1990. pp. 247–279. [Google Scholar]

- Baron RM, Kenny DA. The moderator–mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1986;51:1173–1182. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.51.6.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Battistich V, Solomon D, Watson M, Schaps E. Caring school communities. Educational Psychologist. 1997;32:137–151. [Google Scholar]

- Bentler PM. Judea’s parameter over identification. 2000 September 2; Message posted to SEMNET, archived at http://bama.ua.edu/cgi-bin/wa?A2=ind0009&L=semnet&P=R1330&I=1.

- Birch SH, Ladd GW. The teacher–child relationship and children’s early school adjustment. Journal of School Psychology. 1997;35:61–79. [Google Scholar]

- Birch SH, Ladd GW. Children’s interpersonal behaviors and the teacher–child relationship. Developmental Psychology. 1998;34:934–946. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.34.5.934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boethel M. Diversity: School, family, and community connections. Annual Synthesis 2003. Austin, TX: Southwest Educational Development Laboratory, National Center for Family and Community Schools; 2003. Retrieved February 18, 2005, from http://www.sedl.org/connections/resources/diversity-synthesis.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Bracken BA, McCallum S. Universal Nonverbal Intelligence Test. Chicago: Riverside; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Brody GH, Dorsey S, Forehand R, Armistead L. Unique and protective contributions of parenting and classroom processes to the adjustment of African American children living in single-parent families. Child Development. 2002;73:274–286. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks-Gunn J, Markman LB. The contribution of parenting to ethnic and racial gaps in school readiness. The Future of Children. 2005;15:139–168. doi: 10.1353/foc.2005.0001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buhrmester D, Furman W. The development of companionship and intimacy. Child Development. 1987;54:1386–1399. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1987.tb01444.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burchinal MR, Peisner-Feinberg E, Pianta R, Howes C. Development of academic skills from preschool through second grade: Family and classroom predictors of developmental trajectories. Journal of School Psychology. 2002;40:415–436. [Google Scholar]

- Chavkin NF, Williams DL. Minority parents and the elementary school: Attitudes and practices. In: Chavkin NF, editor. Families and schools in a pluralistic society. Albany, NY: SUNY Press; 1993. pp. 73–83. [Google Scholar]

- Clark R. Family life and school achievement: Why poor Black children succeed or fail. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Cole DA, Maxwell SE. Testing mediational models with longitudinal data: Questions and tips in the use of structural equation modeling. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2003;112:558–577. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.112.4.558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conduct Problems Prevention Research Group. Teacher social competence. 2004 Available from http://www.fasttrackproject.org/techrept/t/tsc/

- Connell JP, Wellborn JG. Competence, autonomy and relatedness: A motivational analysis of self-system processes. In: Gunnar M, Sroufe LA, editors. Minnesota Symposium on Child Psychology: Self processes and development. Vol. 2. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 1991. pp. 43–77. [Google Scholar]

- Early DM, Pianta RC, Taylor LC, Cox JJ. Transition practices: Findings from a national survey of kindergarten teachers. Early Childhood Education Journal. 2001;28:199–206. [Google Scholar]

- Eccles JS, Wigfield A, Schiefele U. Motivation to succeed. In: Damon W, Eisenberg N, editors. Handbook of child psychology: Social and personality development. Vol. 4. New York: Wiley; 1998. pp. 1017–1095. [Google Scholar]

- Entwisle DR, Alexander KL. Factors affecting achievement test scores and marks of Black and White first graders. Elementary School Journal. 1988;88:449–471. [Google Scholar]

- Epstein JL. Single parents and the schools: Effects of marital status on parent and teacher evaluation (Rep. No. 353) Baltimore: John Hopkins University, Center for Social Organization of Schools; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Epstein JL. Perspectives and previews on research and policy for school, family, and community partnerships. In: Booth A, Dunn JF, editors. Family school links: How do they affect educational outcomes? Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum; 1996. pp. 209–246. [Google Scholar]

- Fan X, Chen M. Parental involvement and students’ academic achievement: A meta-analysis. Educational Psychology Review. 2001;13:1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Fredricks JA, Blumenfeld PC, Paris AH. School engagement: Potential of the concept, state of the evidence. Review of Educational Research. 2004;74:59–109. [Google Scholar]

- Furrer C, Skinner E. Sense of relatedness as a factor in children’s academic engagement and performance. Journal of Educational Psychology. 2003;95:148–162. [Google Scholar]

- The Future of Children. School readiness: Closing racial and ethnic gaps. Princeton, NJ: The Woodrow Wilson School of Public and International Affairs at Princeton University and the Brookings Institution; 2005. Retrieved February 15, 2005, from http://www.futureofchildren.org/information2826/information_show.htm?doc_id=25598. [Google Scholar]

- Hamre BK, Pianta RC. Early teacher–child relationships and the trajectory of children’s school outcomes through eighth grade. Child Development. 2001;72:625–638. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henderson AT, Mapp KL. A new wave of evidence: The impact of school, family, and community connections on student achievement. Annual Synthesis 2002. Austin, TX: Southwest Educational Development Laboratory, National Center for Family & Community Connections with Schools; 2002. Available from www.sedl.org/connections/resources/evidence.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Hill NE, Castellino DR, Lansford JE, Nowlin P, Dodge KA, Bates JE, Pettit GS. Parent academic involvement as related to school behavior, achievement, and aspirations: Demographic variations across adolescence. Child Development. 2004;75:1491–1509. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2004.00753.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howes C, Hamilton CE, Matheson CC. Children’s relationships with peers: Differential associations with aspects of the teacher–child relationship. Child Development. 1994;65:253–263. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1994.tb00748.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hudley CA. Comparing teacher and peer perceptions of aggression: An ecological approach. Journal of Educational Psychology. 1993;85:377–384. [Google Scholar]

- Hughes J. Assessment of children’s social competence. In: Reynolds CR, Kamphaus R, editors. Handbook of psychological and educational assessment of children. New York: Guilford Press; 1990. pp. 423–444. [Google Scholar]

- Hughes JN, Cavell TA, Jackson T. Influence of teacher–student relationship on childhood aggression: A prospective study. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology. 1999;28:173–184. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp2802_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes JN, Cavell TA, Willson V. Further evidence of the developmental significance of the teacher–student relationship. Journal of School Psychology. 2001;39:289–302. [Google Scholar]

- Hughes JN, Gleason K, Zhang D. Relationships as predictors of teachers’ perceptions of academic competence in academically at-risk minority and majority first-grade students. Journal of School Psychology. 2005;43:303–320. doi: 10.1016/j.jsp.2005.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes JN, Yoon J, Cavell TA. Child, teacher, and peer reports of teacher–student relationship: Cross-informant agreement and relationship to school adjustment; Paper presented at the biennial meeting of the Society for Research in Child Development; Albuquerque, NM. 1999. Apr, [Google Scholar]

- John OP, Srivastava S. The Big Five trait taxonomy: History, measurement, and theoretical perspectives. In: Pervin LA, John OP, editors. Handbook of personality: Theory and research. Vol. 2. New York: Guilford Press; 1999. pp. 102–138. [Google Scholar]

- Jussim L. Self-fulfilling prophecies: A theoretical and integrative review. Psychological Review. 1986;93:429–445. [Google Scholar]

- Kenny DA, Kashy DA, Bolger N. Data analysis in social psychology. In: Gilbert DT, Fiske ST, Lindzey G, editors. The handbook of social psychology. 4. Vol. 1. New York: McGraw-Hill; 1998. pp. 233–265. [Google Scholar]

- Kohl GO, Lengua LJ, McMahon RJ. Parent involvement in school conceptualizing multiple dimensions and their relations with family and demographic risk factors. Journal of School Psychology. 2000;38:501–523. doi: 10.1016/S0022-4405(00)00050-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohl GO, Weissberg RP, Reynolds AJ, Kasprow WJ. Teacher perceptions of parent involvement in urban elementary schools: Sociodemographic and school adjustment correlates; Paper presented at the annual meeting of the American Psychological Association; Los Angeles, CA. 1994. Aug, [Google Scholar]

- Krull JL, MacKinnon DP. Multilevel mediation modeling in group-based intervention studies. Evaluation Review. 1999;23:418–444. doi: 10.1177/0193841X9902300404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krull JL, MacKinnon DP. Multilevel modeling of individual and group level mediated effects. Multivariate Behavioral Research. 2001;36:249–277. doi: 10.1207/S15327906MBR3602_06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ladd GW, Birch SH, Buhs ES. Children’s social and scholastic lives in kindergarten: Related spheres of influence? Child Development. 1999;70:1373–1400. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lasky S. The cultural and emotional politics of teacher–parent interactions. Teaching and Teacher Education. 2000;16:843–860. [Google Scholar]

- Little M, Kobak R. Emotional security with teachers and children’s stress reactivity: A comparison of special-education and regular-education classrooms. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2003;32:127–138. doi: 10.1207/S15374424JCCP3201_12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Little RJA, Rubin DB. Statistical analysis with missing data. New York: Wiley; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Lopez GR. The value of hard work: Lessons on parent involvement from an (im)migrant household. Harvard Educational Review. 2001;71:416–437. [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP, Krull JL, Lockwood CM. Equivalence of the mediation, confounding and suppression effect. Prevention Science. 2000;1:173–181. doi: 10.1023/a:1026595011371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP, Lockwood CM, Hoffman JM, West SG, Sheets V. A comparison of methods to test mediation and other intervening variable effects. Psychological Methods. 2002;7:83–104. doi: 10.1037/1082-989x.7.1.83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcon RA. Positive relationships between parent school involvement and public inner-city preschoolers’ development and academic performance. School Psychology Review. 1999;28:395–412. [Google Scholar]

- Marks HM. Student engagement in instructional activity: Patterns in the elementary, middle, and high school years. American Educational Research Journal. 2000;37:153–184. [Google Scholar]

- Marsh HW, Craven R. The pivotal role of frames of reference in academic self-concept formation: The big fish little pond effect. In: Pajares F, Urdan T, editors. Adolescence and education. II. Greenwich, CT: Information Age; 2002. pp. 83–123. [Google Scholar]

- Masten AS, Morison P, Pellegrini DS. A revised class play method of peer assessment. Developmental Psychology. 1985;21:523–533. [Google Scholar]

- Meehan BT, Hughes JN, Cavell TA. Teacher–student relationships as compensatory resources for aggressive children. Child Development. 2003;74:1145–1157. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Midgley C, Feldlauffer H, Eccles J. Student/teacher relations and attitudes toward mathematics before and after the transition to junior high school. Child Development. 1989;60:981–992. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1989.tb03529.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miles SB, Stipek D. Contemporaneous and longitudinal associations between social behavior and literacy achievement in a sample of low-income elementary school children. Child Development. 2006;77:103–117. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2006.00859.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray CB. Estimating achievement performance: A confirmation bias. Journal of Black Psychology. 1996;22:67–85. [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus user’s guide. Los Angeles: Muthén & Muthén; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- National Center for Education Statistics. Characteristics of schools, districts, teachers, principals, and school libraries in the United States 2003–04: Schools and Staffing Survey. 2005a [Table 18]. Retrieved December 14, 2006, from http://nces.ed.gov/pubsearch/pubsinfo.asp?pubid=2006313.

- National Center for Education Statistics. Digest of education statistics: 2005. 2005b Retrieved December 14, 2006, from http://nces.ed.gov/programs/digest/d05/tables/dt05_094.asp.

- National Center for Education Statistics. National assessment of educational progress: The nation’s report card. U.S. Department of Education. 2005c Retrieved December 21, 2005, from http://nces.ed.gov/nationsreportcard/

- Ogbu J. Variability in minority school performance: A problem in search of an explanation. In: Jacob E, Jordon C, editors. Minority education: Anthropological perspectives. Norwood, NJ: Ablex; 1993. pp. 83–111. [Google Scholar]

- Partenio I, Taylor RL. The relationship of teacher ratings and IQ: A question of bias? School Psychology Review. 1985;14:79–83. [Google Scholar]

- Pianta RC. Teacher–child relationships and early literacy. In: Dickinson D, Neuman S, editors. Handbook of early literacy research. Vol. 2. New York: Guilford Press; 2006. pp. 149–162. [Google Scholar]

- Pianta RC, Rimm-Kauffman SE, Cox MJ. The transition to kindergarten. Baltimore, MD: Brookes Publishing; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Pianta RC, Steinberg MS, Rollins KB. The first two years of school: Teacher–child relationships and deflections in children’s classroom adjustment. Development and Psychopathology. 1995;7:295–312. [Google Scholar]

- Pianta RC, Walsh DJ. High-risk children in schools: Constructing sustaining relationships. New York: Routledge; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Pigott RL, Cowen EL. Teacher race, child race, racial congruence, and teacher ratings of children’s school adjustment. Journal of School Psychology. 2000;38:177–196. [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds AJ. Early schooling of children at risk. American Educational Research Journal. 1991;28:392–422. [Google Scholar]

- Ridley SM, McWilliam RA, Oates CS. Observed engagement as an indicator of child care program quality. Early Education and Development. 2000;11:133–146. [Google Scholar]

- Rimm-Kaufman SE, La Paro KM, Downer JT, Pianta RC. The contribution of classroom setting and quality of instruction to children’s behavior in kindergarten classrooms. The Elementary School Journal. 2005;105:377–394. [Google Scholar]

- Rimm-Kaufman SE, Pianta RC, Cox JJ, Bradley R. Teacher-rated family involvement and children’s social and academic outcomes in kindergarten. Early Education and Development. 2003;14:179–198. [Google Scholar]

- Ritter PL, Mont-Reynaud R, Dornbusch SM. Minority parents and their youth: Concern, encouragement, and support for school achievement. In: Chavkin NF, editor. Families and schools in a pluralistic society. Albany, NY: SUNY Press; 1993. pp. 107–119. [Google Scholar]

- Rock DA, Stenner AJ. Assessment issues in the testing of children at school entry. The Future of Children. 2005;15(1):15–34. doi: 10.1353/foc.2005.0009. Retrieved February 15, 2005, from www.futureofchildren.org. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Saft EW, Pianta RC. Teachers’ perceptions of their relationships with students: Effects of child age, gender, and ethnicity of teachers and children. School Psychology Quarterly. 2001;16:125–141. [Google Scholar]

- Sameroff AJ. Transactional models in early social relations. Human Development. 1975;18:65–79. [Google Scholar]

- Sampson RJ, Morenoff JD, Earls F. Beyond social capital: Spatial dynamics of collective efficacy for children. American Sociological Review. 1999;64:633–660. [Google Scholar]

- Satorra A. Scaled and adjusted restricted tests in multi-sample analysis of moment structures. In: Heijmans RDH, Pollock DSG, Satorra A, editors. Innovations in multivariate statistical analysis: A Festschrift for Heinz Neudecker. London: Kluwer Academic; 2000. pp. 233–247. [Google Scholar]

- Shonkoff JP, Phillips D, editors. From neurons to neighborhoods: The science of early childhood development. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 2000. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shrout PE, Bolger N. Mediation in experimental and non-experimental studies: New procedures and recommendations. Psychological Methods. 2002;7:422–445. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silver RB, Measelle JR, Armstrong JM, Essex MJ. Trajectories of classroom externalizing behavior: Contributions of child characteristics, family characteristics, and the teacher–child relationship during the school transition. Journal of School Psychology. 2005;43:39–60. [Google Scholar]

- Simpson CH, Rosenholtz SJ. Classroom structure and the social construction of ability. In: Richardson JG, editor. Handbook of theory and research for the sociology of education. New York: Greenwood Press; 1986. pp. 113–138. [Google Scholar]

- Skinner E, Belmont M. Motivation in the classroom: Reciprocal effects of teacher behavior and student engagement across the school year. Journal of Educational Psychology. 1993;85:571–581. [Google Scholar]

- Skinner EA, Zimmer-Gembeck MJ, Connell JP. Individual differences and the development of perceived control. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development. 1998;63(2–3) Whole No. 204. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobel ME. Asymptotic confidence intervals for indirect effects in structural equation models. In: Leinhardt S, editor. Sociological methodology 1982. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 1982. pp. 290–312. [Google Scholar]

- Stipek DJ. Motivation to learn: From theory to practice. 4. Needham Heights, MA: Allyn & Bacon; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Terry R. Measurement and scaling issues in sociometry: A latent trait approach; Paper presented at the biennial meeting of the Society for Research in Child Development; Albuquerque, NM. 1999. Apr, [Google Scholar]

- Trzesniewski KH, Moffitt TE, Caspi A, Taylor A, Maughan B. Revisiting the association between reading achievement and antisocial behavior: New evidence of an environmental explanation from a twin study. Child Development. 2006;77:72–88. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2006.00857.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urdan T, Midgley C. Changes in the perceived classroom goal structure and pattern of adaptive learning during early adolescence. Contemporary Educational Psychology. 2003;28:524–551. [Google Scholar]

- Vickers HS, Minke KM. Exploring parent–teacher relationships: Joining and communication to others. School Psychology Quarterly. 1995;10:133–150. [Google Scholar]

- Wehlage GG, Rutter RA. Dropping out: How much do schools contribute to the problem? Teachers College Record. 1986;87:374–392. [Google Scholar]

- Wentzel KR. Social–motivational processes and interpersonal relationships: Implications for understanding motivation at school. Journal of Educational Psychology. 1999;91:76–97. [Google Scholar]

- Wigfield A, Eccles JS. Expectancy–value theory of achievement motivation. Contemporary Educational Psychology. 2000;25:68–81. doi: 10.1006/ceps.1999.1015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong SW, Hughes JN. Ethnicity and language contributions to dimensions of parent involvement. School Psychology Review. in press. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodcock RW, Johnson MB. Woodcock–Johnson Psycho-Educational Battery—Revised. Allen, TX: DLM Teaching Resources; 1989. [Google Scholar]