Abstract

Many eukaryotic positive-strand RNA viruses transcribe subgenomic (sg) mRNAs that are virus-derived messages that template the translation of a subset of viral proteins. Currently, the premature termination (PT) mechanism of sg mRNA transcription, a process thought to operate in a variety of viruses, is best understood in tombusviruses. The viral RNA elements involved in regulating this mechanism have been well characterized in several systems; however, no corresponding protein factors have been identified yet. Here we show that tombusvirus genome replication can be effectively uncoupled from sg mRNA transcription in vivo by C-terminal modifications in its RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp). Systematic analysis of the PT transcriptional pathway using viral genomes harboring mutant RdRps revealed that the C-terminus functions primarily at an early step in this mechanism by mediating both efficient and accurate production of minus-strand templates for sg mRNA transcription. Our results also suggest a simple evolutionary scheme by which the virus could gain or enhance its transcriptional activity, and define global folding of the viral RNA genome as a previously unappreciated determinant of RdRp evolution.

Keywords: gene expression, protein evolution, RNA-dependent RNA polymerase, subgenomic mRNA, tombusvirus

Introduction

Eukaryotic positive-strand RNA viruses represent a distinct class of infectious agents that includes important pathogens of both plants and animals (Buck, 1996). Those that possess polycistronic genomes often transcribe subgenomic (sg) mRNAs during infections (Miller and Koev, 2000). These smaller virus-derived messages encode open reading frames (ORFs) that are translationally silent in the full-length viral genome and permit temporal and quantitative control of viral gene expression.

The virally encoded RNA-dependent RNA polymerases (RdRps) responsible for replicating positive-strand RNA virus genomes—via minus-strand RNA intermediates—are also the same catalytic subunits that transcribe sg mRNAs (Miller and Koev, 2000). To date, three distinct mechanistic models for sg mRNA transcription have been identified. The internal initiation (II) model involves initiation of transcription at a sg mRNA promoter located internally within the full-length minus-strand of a viral genome (Miller et al, 1985), whereas the discontinuous template synthesis (DTS) model entails the use of a discontinuously synthesized minus-strand template for sg mRNA transcription (Sawicki and Sawicki, 1998; van Marle et al, 1999a; Pasternak et al, 2001; Sola et al, 2005). In the premature termination (PT) model, the RdRp terminates prematurely while synthesizing a full-length minus-strand copy of the viral RNA genome and the 3′-truncated minus-strand RNA generated serves as a template for sg mRNA transcription (Sit et al, 1998; White, 2002). This PT mechanism is believed to be utilized by a variety of viruses, including those that infect mammals (e.g., toroviruses; van Vliet et al, 2002; Smits et al, 2005), aquatic invertebrates (e.g., roniviruses; Cowley et al, 2002), fish (e.g., betanodaviruses; Iwamoto et al, 2005), plants (e.g., dianthoviruses; Sit et al, 1998 and closteroviruses; Gowda et al, 2001), and insects (e.g., nodaviruses; Lindenbach et al, 2002).

The PT mechanism has been studied most extensively in Tomato bushy stunt virus (TBSV; genus Tombusvirus, family Tombusviridae) (White and Nagy, 2004). The positive-strand RNA genome of TBSV encodes five proteins (Hearne et al, 1990). The 5′ proximal p33 and its read-through product p92 (the RdRp) are translated directly from the viral genome, whereas more 3′-proximally positioned proteins are translated from two sg mRNAs that are transcribed during infections (Figure 1A; White and Nagy, 2004). Of these five viral proteins, only the p92 RdRp and its auxiliary factor p33 are required for genome replication and sg mRNA transcription (White and Nagy, 2004).

Figure 1.

TBSV genome and sg mRNA transcriptional RNA elements. (A) Schematic linear representation of the TBSV RNA genome and its coding organization. Boxes indicate encoded proteins. The p92 RdRp is translated directly from the viral genome by readthrough of the p33 stop codon (UAG). Proteins encoded downstream are translated from two sg mRNAs that are transcribed during infections. The relative positions (arrowheads) of interacting RNA elements that are involved in sg mRNA transcription are shown above the viral genome. Initiation sites for sg mRNA transcription are labeled sg1 and sg2 and bold arrows represent corresponding structures of the two sg mRNAs below. (B) RNA elements that regulate sg mRNA transcription in TBSV. Relevant sequences of the TBSV genome are shown with corresponding coordinates provided. The AS1/RS1 base pairing interaction is essential for sg mRNA 1 transcription, whereas the DE/CE and AS2/RS2 interactions are essential for transcription of sg mRNA2. Stem-loop structures containing AS1 and AS2 are connected by an 11-nt-long sequence (boxed). Initiation sites for the two sg mRNAs are indicated by small arrows and are separated from their respective AS/RS interactions by spacer elements (underlined). A PT mechanism for sg mRNA2 transcription is depicted at the bottom with relevant terminal sequences shown. The minus-strand generated by the termination event contains the sg mRNA promoter (shaded) and templates the transcription of sg mRNA2.

Studies of TBSV have identified numerous RNA elements in the viral genome that are involved in the PT mechanism, including distant RNA–RNA interactions (Zhang et al, 1999; Choi et al, 2001; Choi and White, 2002; Lin and White, 2004). Long-range interactions occur in the positive strand and involve RNA sequences located immediately 5′ to the transcriptional initiation sites for sg mRNA1 and sg mRNA2, termed receptor sequence-1 (RS1) and RS2, respectively (Figure 1B). These two RS elements base pair with corresponding activator sequence-1 (AS1) and AS2, located ∼1000 and ∼2100 nt upstream, respectively (Figure 1B). The RNA structures formed by the AS/RS interactions are essential for the RdRp termination events that occur during minus-strand synthesis, and lead to production of 3′-truncated templates (Choi and White, 2002; Lin and White, 2004). Interestingly, the long-range nature of these interactions is not essential, because an AS/RS element can be functionally replaced by a stable RNA hairpin positioned just upstream from its cognate transcription initiation site (Lin and White, 2004). Termination efficiency at these RNA structures is also influenced by the distance between the base paired element and the site of initiation (i.e., the length of the so-called spacer element) (Figure 1B; Lin et al, 2007). Subsequent utilization of 3′-truncated minus-strand templates for transcription relies on linear sg mRNA promoters located at their 3′-ends (Figure 1B). These promoters are structurally and functionally similar to that used by the virus to produce full-length positive-strand genomes (Lin and White, 2004). Thus, mechanistically, the main feature distinguishing TBSV sg mRNA transcription from genome replication is the manner by which the corresponding minus-strand templates are generated (i.e., termination internally versus termination at the 5′ end of the template).

Currently, no protein factors have been identified for any of the viruses that utilize a PT mechanism. For TBSV, previous mutational analysis of the RS1 element suggested a possible role for this sequence in modulating sg mRNA2 levels in vivo (Choi and White, 2002). However, because the RS1 sequence also encodes the C-terminus of the p92 RdRp (Figures 1A and 2A), it was unclear whether the defect was RNA- or protein-based. In this study, we systematically investigated the function of the C-terminus of the TBSV RdRp and demonstrate that viral genome replication can be efficiently uncoupled from sg mRNA transcription at the protein level. Our analyses also revealed the steps in the PT mechanism requiring the C-terminal activity and alluded to a plausible evolutionary scheme by which the virus could gain or enhance its transcriptional activity. Moreover, an important role for global RNA virus genome structure in modulating RdRp evolution was uncovered. Specific and general implications of these findings are discussed.

Figure 2.

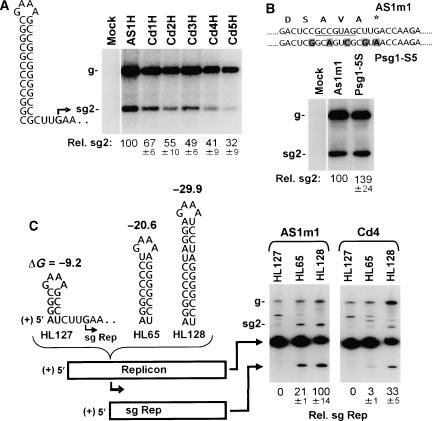

Mutational analysis of the C-terminus of the TBSV RdRp. (A) The AS1/RS1 interaction in the wt TBSV genome (i.e., T100) and corresponding coding region for the C-terminus of p92. Amino acids in the C-terminus of p92 are presented under the RNA sequence. The nucleotide substitutions in mutant AS1m1 are indicated by shading (see inset). (B) Deletion analysis of C-terminal residues of the RdRp. Mutant viral genomes containing deletions of 1–10 C-terminal amino acids (Cd1 through Cd10, respectively) were transfected into plant protoplasts and sg mRNA2 levels quantified by northern blot analysis with a virus-specific DNA probe following a 24 h incubation. The identities of the viral genomes used in the transfections are indicated at the top. The positions of the viral genome (g) and sg mRNAs (sg1 and sg2) are shown to the left. The values below, in this and in other similar experiments, correspond to means from three independent experiments (with standard deviations) and represent the ratios of sg mRNA2 levels to their corresponding genomic RNA levels, all normalized to that for the control (in this case, AS1m1), set at 100. (C) Western blot analysis of p92 (and p33) accumulation in transfected protoplasts for wt TBSV (T100), control viral genome AS1m1, and C-terminally truncated mutants Cd1 through Cd5. Viral proteins were detected with antiserum generated against a peptide corresponding to a region in p33 (which is also present in p92). Accordingly, both p33 and p92 are detected by this antiserum. (D) Transcriptional activity of viral genome mutants containing single substitutions in each of the five C-terminal residues in the RdRp. The wt residues are presented at the top of the northern blot, with the corresponding substitutions indicated immediately below. The left and right panels in panel D are from the same experiment but were analyzed on separate gels. The associated values were generated relative to the same internal control, AS1m1, that was included in both blots.

Results

The C-terminus of the RdRp is involved in sg mRNA transcription

An infectious clone of a previously constructed modified TBSV genome, AS1m1, was used for in vivo analysis of RdRp activity (Choi and White, 2002). In AS1m1, the upstream AS1 element contains translationally silent substitutions that prevent it from base pairing with its RS1 partner sequence (Figure 2A, inset). These changes uncouple the RdRp-coding function of RS1 from its RNA structure-related function, thus allowing for unfettered mutational analysis of the C-terminus of p92 within the viral genome. However, since sg mRNA1 is inactivated in AS1m1, the effect of RdRp modifications on sg mRNA transcription was monitored by assessing the accumulation levels of sg mRNA2.

Plant protoplasts were transfected with in vitro-transcribed wt (T100) and modified TBSV genomes, and the levels of viral RNA accumulation were determined by northern blot analysis following a 24-h incubation. C-terminal RdRp deletion analysis—that involved introduction of tandem termination codons at appropriate positions in the 3′ region of the p92 ORF—revealed that removal of the ultimate Ala residue in Cd1 caused a relative ∼5-fold decrease in sg mRNA2 accumulation (Figure 2B). Additional deletions of up to four residues in Cd2 through Cd4 resulted in ∼10-fold reductions in sg mRNA2 levels, whereas removal of one additional residue in Cd5 led to a ∼20-fold drop. This progressive decrease in sg mRNA2 was also observed at earlier time points and at lower incubation temperatures (data not shown). Interestingly, when six or more C-terminal residues were deleted (Cd6 through Cd10), no viral RNAs accumulated, signifying a lethal defect eliminating all forms of RNA synthesis (Figure 2B). For the viable mutants, western blot analysis of p92 revealed very low but relatively comparable levels of accumulation (Figure 2C), suggesting similar levels of protein stability.

The importance of the five C-terminal residues for sg mRNA transcription was investigated further by substituting each with three different amino acids of similar or contrasting chemical properties (Figure 2D). The most notable defects were observed at the third and fifth positions from the end, where substitutions of Ala or Asp, respectively, with (Asp, Lys) or (Asn, Lys) caused sg mRNA2 levels to drop by ∼80–90%. For the other modifications tested, none inhibited sg mRNA2 to levels below ∼46% (Figure 2D). Overall, the C-terminal substitution analysis revealed that (i) amino-acid identities are somewhat flexible, (ii) severe defects in sg mRNA transcription can also be induced through amino-acid substitutions and (iii) the Ser residue is not a phosphoregulator of transcriptional activity.

Mutant viral genomes are transcriptionally defective at the protein level

The results above pointed to a defective RdRp; however, the possibility that the long-distance RNA–RNA interactions essential for sg mRNA2 transcription may have been adversely affected by the sequence modifications needed to be critically addressed. To this end, sg mRNA2 transcription was uncoupled from its two essential long-range interactions, DE/CE and AS2/RS2 (Figure 1A; Zhang et al, 1999; Lin and White, 2004). This was accomplished by deleting CE and replacing RS2 with a local RNA hairpin positioned just upstream from the sg mRNA2 transcription initiation site (Figure 3A). When the C-terminally truncated RdRp mutants Cd1H through Cd5H were tested along with the AS1H control (encoding wt RdRp), the results were similar to those observed earlier (Figure 2B), except that the defects in transcription were less prominent (Figure 3A). This reduced inhibition could be related to differences in the structure and/or stability of the local RNA hairpin compared with those of the wt long-distance AS2/RS2 interaction. Importantly, the general trend of the transcriptional defect was reproducible for sg mRNA2 in a context lacking its cognate essential long-distance RNA–RNA interactions.

Figure 3.

Context-independent activity of mutant RdRps. (A) A local RNA hairpin (left) was substituted for the long-range AS2/RS2 interaction in mutant viral genomes. The identities of the mutant viral genomes used in the transfections are indicated at the top of the Northern blot. The relative sg mRNA2 values shown below were calculated as described in the legend to Figure 2B. (B) The five translationally silent substitutions in the C-terminal coding region of p92 in viral genome mutant Psg1-S5 are indicated by shading (top). Northern blot analysis of Psg1-S5 and control AS1m1. (C) HL127, HL65, and HL128 are small viral replicons (Replicon) containing different sized hairpin-type transcriptional cassettes (left). Free energy changes (ΔG, at 22°) for formation of each RNA structure are indicated in kcal/mol. The sg RNA that is transcribed from these replicons (sg Rep) is indicated below. Each replicon was cotransfected into protoplasts along with helper viral genome AS1m1 (wt RdRp) or Cd4 (mutant RdRp C-terminally truncated by four residues), and relative sg Rep accumulation levels assessed by northern blotting following a 24-h incubation period. The bands located between the genome (g) and sg mRNA2 (sg2) likely represent multimers of the replicon.

To further substantiate the proposed RdRp-dependent defect, two additional approaches were pursued. In the first, five substitutions were introduced simultaneously at degenerate codon positions in the C-terminal region of the RdRp (Figure 3B). When tested, the Psg1-S5 genome transcribed sg mRNA2 efficiently (Figure 3B), thereby excluding this RNA sequence from being directly involved in modulating sg mRNA2 production.

In the final approach, it was reasoned that if the RdRp was responsible for the reductions of sg mRNA2, then it should be possible to confer the defect in trans to another transcriptionally active viral RNA replicon. To test this hypothesis, small non-coding TBSV replicons (White, 1996) containing RNA hairpin-type transcriptional cassettes (Lin and White, 2004) were cotransfected with viral genomes containing a wt or C-terminally truncated RdRp (Figure 3C). Replicon-derived sg RNAs (sg Reps) were generated from HL65 and HL128 (containing the more stable RNA hairpins) when they were cotransfected with AS1m1, which provided wt RdRp in trans (Figure 3C). In contrast, when the same replicons were complemented with Cd4, a viral genome producing an RdRp truncated by four C-terminal residues, there was notably reduced levels of sg Rep accumulation (Figure 3C). The ability to confer the defect in trans further supports a protein-based activity. Thus, all three approaches used to assess the origin of the transcriptional defect point to the RdRp as the causal factor.

The C-terminus of the RdRp facilitates the termination step of the PT transcriptional mechanism

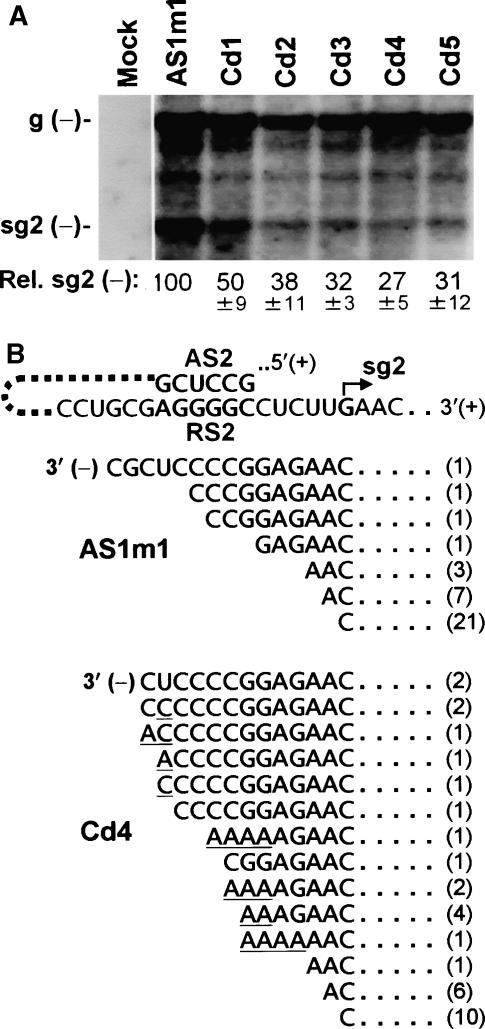

We next turned our attention to determining what step(s) in the PT mechanism the RdRp C-terminus was facilitating. An early event in this process is the attenuation of the RdRp that leads to its termination and the production of minus-stand intermediates (Figure 1B). In C-terminally truncated mutants, Cd1 through Cd5, relative levels of sg mRNA minus-strand accumulation were reduced to ∼30–50% that of the AS1m1 control (Figure 4A). Overall, the accumulation of these minus-strand sg mRNA templates was lowered by ∼2- to 3-fold; however, their corresponding plus-strand sg mRNAs were decreased by ∼5- to 20-fold (Figure 2B). This implied that the reduction in minus-strand templates had an amplified detrimental effect on plus-strand transcription, or that additional factors were contributing to the outcome.

Figure 4.

Minus-strand RNA analysis of C-terminally truncated RdRp mutants. (A) Northern blot analysis of minus-strand accumulation levels in protoplasts was performed 24 h post-transfection using a positive-sense RNA probe complementary to genomic and sg mRNAs. The mutants examined are indicated at the top and the positions of minus-strand viral genome (g (−)) and sg mRNA2 (sg2 (−)) are shown on the left. (B) Sequence analysis of the 3′ termini of sg mRNA2 minus strands. 3′-RACE was used to determine the terminal sequences for AS1m1 (wt RdRp) and Cd4 (mutant RdRp). The sequences of 3′-terminal regions of sg mRNA2 minus strands are shown below corresponding positive-strand sequence. The numbers in parentheses indicate the number of times each sequence was observed. Non-templated residues are underlined.

One possibility considered was that the 3′-termini of the minus strands generated were aberrant (i.e., contained extra or deleted residues relative to the 3′ end of the promoter sequence)—a feature known to adversely affect tombusvirus promoter activity (Panavas et al, 2002; Lin and White, 2004). Analysis of the 3′-termini of minus-strand templates from AS1m1 or Cd4 showed that the latter had approximately twice as many templates with 3′ ends that were extended past the initiating nucleotide (Figure 4B). Some of the Cd4-derived templates also contained non-templated residues. The higher proportion of aberrant 3′-termini generated by the C-terminally truncated Cd4 would act to decrease overall promoter activity and contribute to the reduced levels of sg mRNA. Primer extension analysis of the 5′ ends of sg mRNA2s from infections with Cd4 (and other C-terminally truncated mutants) revealed only authentic 5′ termini, indicating no defects in terms of the accuracy of initiation of transcription (data not shown).

Influence of base paired and linear components of the RNA attenuation signal on sg mRNA transcription

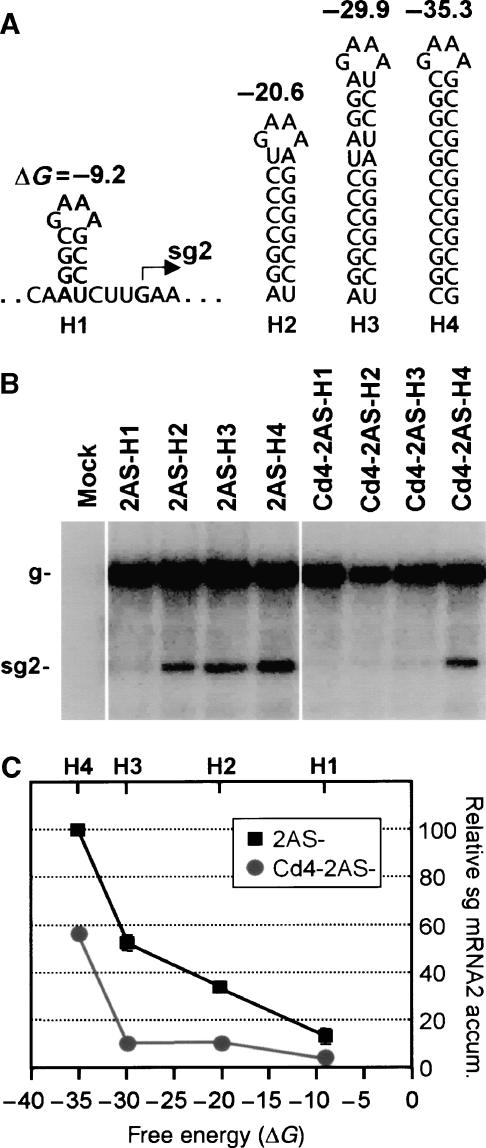

The RdRp attenuation signal includes both base paired and linear RNA elements, and its activity is affected by both the thermodynamic stability of the base paired structure and the length of the associated linear spacer element (Lin and White, 2004; Lin et al, 2007). Accordingly, these two components were examined with respect to the RdRp C-terminus. First, the transcriptional efficiency mediated by different sized RNA hairpins was assessed to determine how the C-terminal RdRp mutants would respond to structures with increasing thermodynamic stability (Figure 5A). This analysis was carried out using viral genomes that expressed an RdRp truncated by four residues (i.e., Cd4 based). Consistent with our other results (Figure 3A and C), the genomes expressing the mutant RdRp (Cd4-2AS-H1 through -H4) did not utilize the RNA hairpin signals as efficiently as their counterparts expressing the wt RdRp (2AS-H1 through -H4; Figure 5B). This relationship, depicted graphically in Figure 5C, indicates a general lower sensitivity of the mutant RdRp for detecting the base paired component of the RNA attenuation signal, particularly for H1 through H3 (note difference in slopes). In contrast, the corresponding relative accumulation profiles were comparable when spacer elements ranging in lengths from 0 to 6 nt were tested (Figure 6). Thus, a mutant RdRp lacking four C-terminal residues has spacer length requirements that are similar to those of the wt RdRp.

Figure 5.

Effect of hairpin stability on sg mRNA2 transcription by C-terminally truncated RdRp. (A) Depiction of RNA hairpin cassettes introduced into modified viral genomes. Free energy changes (ΔG, at 22°) for formation of each RNA structure are indicated in kcal/mol. (B) Hairpins were tested in genomic contexts that expressed either wt RdRp (2AS-H1 through -H4) or an RdRp C-terminally truncated by four residues (Cd4-2AS-H1 through -H4). Northern blot analysis of viral RNA accumulation 24 h post-transfection of protoplasts is presented. (C) Graphical representation of relative accumulation values for sg mRNA2 observed in panel B plotted against predicted RNA hairpin stability (ΔG). For relative sg mRNA2 accumulation levels presented, that for 2AS-H4 was set at 100 and the other values were normalized relative to this number. Vertical bars indicate standard deviations.

Figure 6.

Effect of spacer length on transcription from C-terminally truncated RdRp mutants. (A) In viral genome mutants S0 through S6, spacer sequences of 0–6 uridylates (Us) were tested for transcriptional activity in protoplast transfections. (B) Northern blot analysis of sg mRNA2 accumulation 24 h post-transfection of protoplasts is presented. The Cd4H series blot was exposed approximately twice as long as the AS1H series blot. (C) Graphical representation of relative accumulation values for sg mRNA2 observed in panel B plotted against spacer length. For relative sg mRNA2 accumulation levels presented, those for AS1H-S2 and Cd4H-S2 were set at 100 and the other corresponding values were normalized relative to those numbers. Vertical bars indicate standard deviations.

Sg mRNA promoter activity is adversely affected by C-terminally truncated RdRp

We next sought to determine if the C-terminal truncations were also affecting the ability of the RdRp to utilize the wt sg mRNA2 promoter. In TBSV, sg mRNA promoters and the genome plus-strand promoter have similar linear structures and sequence identities (Figure 7A) and are interchangeable (Lin and White, 2004). Thus, to address the potential effects of the C-terminal truncations on sg mRNA promoter activity in a context independent of the sg mRNA-specific transcription attenuation components, we repositioned the sg mRNA2 promoter to the end of a small viral replicon (Rep-HL47) and compared the level of replication with that of a wt replicon containing the genomic promoter (Figure 7A). The mutant RdRps were provided in trans—through cotransfection with mutant viral genomes Cd1 through Cd5—and effects of the C-terminal deletions on the activities of the two promoters were monitored via replicon accumulation. Results from these cotransfection studies revealed that with increasing C-terminal deletions, accumulation levels of Rep-HL47 were more negatively affected than those of the wt replicon (Figure 7B). This general trend for the defects suggests that the C-terminal truncations preferentially affect the ability of the mutant RdRps to utilize the wt sg mRNA2 promoter (Figure 7C). Thus, even if these mutant RdRps were to generate wt promoters (i.e., minus-strand templates with 3′ termini corresponding to the transcription initiation site), they would be slightly compromised (∼10 to ∼35%) in their ability to utilize them.

Figure 7.

Sg mRNA2 promoter activity with wt and C-terminally truncated RdRps. (A) Schematic representation of a replicon with complementary wt or sg mRNA2 5′-terminal minus-strand sequences (i.e., promoters) expanded above. Nucleotide differences in the two sequences are highlighted. (B) Northern blot analysis of replicon RNA accumulation levels when protoplasts were cotransfected with viral genomes expressing wt (AS1m1) or C-terminally truncated (Cd1 through Cd5) RdRps. (C) Graphical representation of relative accumulation values for replicons observed in panel B plotted against viral genomes expressing wt and mutant RdRps (provided in trans). For relative accumulation levels presented, that for the wt replicon cotransfected with AS1m1 (wt RdRp) was set at 100 and the other corresponding values were normalized relative to that number. Vertical bars indicate standard deviations. The differences between Rep (wt) and HL47 accumulation levels were statistically significant for Cd4 (P<0.01) and Cd5 (P<0.05).

RdRp coding and functional RNA elements involved in sg mRNA transcription overlap

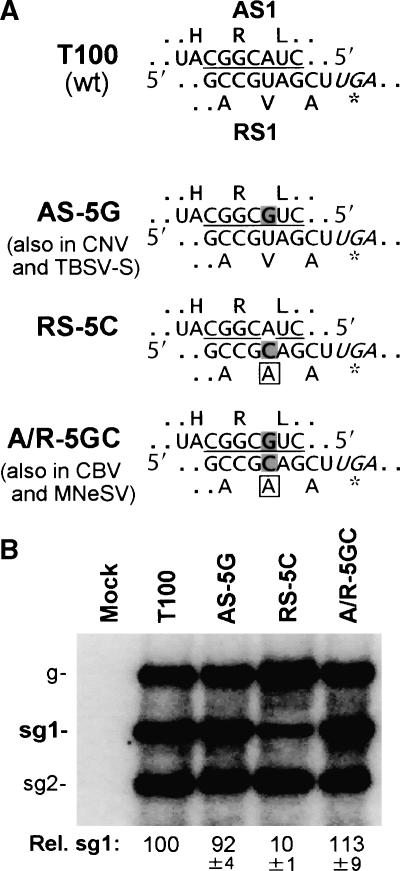

An interesting aspect of the TBSV RdRp is that the RNA sequence encoding its transcription-specific C-terminus is also an RNA regulatory element involved in directing sg mRNA1 transcription (Choi and White, 2002). In particular, the RS1 element shares its sequence with the codons that specify the last three residues of the RdRp (refer to Figure 2A). This is a fascinating example of precisely overlapping sub-elements where both components mediate the same viral process, that is, sg mRNA transcription. This tight coupling must, in turn, place unique evolutionary constraints on these elements. Despite such limitations, it is interesting to note that two tombusviruses, Cucumber Bulgarian virus (CBV) and Maize necrotic streak virus (MNeSV), contain modifications in this region that maintain both RNA- and protein-based functions. In these two viral genomes, the predicted AS1/RS1 interactions contain a GC base pair (which maintains the AS1/RS1 interaction) in place of the corresponding AU base pair in TBSV (compare structures of A/R-5GC and T100, respectively, in Figure 8A). In CBV and MNeSV, the nucleotide substitutions in their AS1 and RS1 elements result in the maintenance of Leu residues internally and Val-to-Ala substitutions at the C-termini of their RdRps, respectively. To assess the effects of these modifications in the context of TBSV, we constructed a mutant genome that contained the double substitution of the AU-to-GC base pair, as well as the single substitution mutants A-to-G (at AS1) or U-to-C (at RS1; Figure 8A). As anticipated, sg mRNA1 levels were preferentially affected, showing relative accumulation levels of ∼92% (for the UG wobble pair; mutant AS-5G), ∼10% (for the AC mismatch; RS-5C) and ∼113% (for the compensatory GC pair; A/R-5GC), as compared with that for the wt T100 (Figure 8B). Thus, although coding and RNA-based regulatory activities are tightly coupled in a common sequence, the AS1 and RS1 elements possess the capacity to evolve while maintaining both of these functions. Further relevance of this finding to RdRp evolution is presented in the following section.

Figure 8.

Analysis of AS1/RS1 interaction in wt TBSV genome (T100). (A) AS1 and RS1 sequences from wt (T100) and mutant viral genomes (AS-5G, RS-5C and A/R-5GC) and their corresponding encoded p92 amino acids. Substituted nucleotides are shaded and corresponding amino-acid changes are boxed. Note, the sequences shown for mutants AS-5G and A/R-5GC are present naturally in (CNV and TBSV-S) and (CBV and MNeSV), respectively. (B) Northern blot analysis of mutant viral genomes isolated from protoplasts 24 h post transfection. Relative levels of sg mRNA1 (sg1) accumulation are indicated at the bottom.

Discussion

Uncoupling virus genome replication from sg mRNA transcription

Our results have identified the C-terminus of the TBSV RdRp as a key determinant of sg mRNA transcription. Deletion of up to five C-terminal residues caused major reductions in sg mRNA accumulation, with comparatively minor effects on viral genome replication (Figure 9A). However, removal of one additional residue completely abolished TBSV genome replication, indicating a tight, but separable, physical coupling of crucial RNA replication and transcription functions within the C-terminus (Figure 9A).

Figure 9.

Role of C-terminus of TBSV RdRp in viral RNA synthesis. (A) Summary schematic diagram depicting the role of the C-terminal residues of p92 in sg mRNA transcription and viral genome replication as determined by progressive terminal deletion analysis. (B) A PT model for TBSV sg mRNA transcription highlighting the role of the C-terminus of p92 in the different steps of the process. P92 is depicted with classical right hand RdRp topology (fingers, F; palm, P; and thumb, T, domains). The C-terminus (C) in the cartoon is circled and the arrows point to the steps (i, ii, and iii) in the PT mechanism that are facilitated by these residues. See text for details.

The uncoupling of replication from transcription has been reported in plus-strand RNA viruses that utilize transcriptional mechanisms other than PT. For example, in the alphavirus Sindbis virus (SINV)—that employs an II transcriptional mechanism—mutation of centrally located Arg residues in the nsP4 RdRp prevented it from binding to its sg mRNA promoter and specifically abolished sg mRNA transcription in vitro (Li and Stollar, 2004, 2007). However, this uncoupling was not reproducible in vivo, because the same mutations proved to be lethal to the virus (Li and Stollar, 2004). In contrast, mutations in either SINV nsP3 (unknown function) or in nsP2 (a protease, in addition to other functions) of Semliki Forest virus (also an alphavirus) caused significant defects in sg mRNA transcription in vivo, while maintaining virus viability (LaStarza et al, 1994; Suopanki et al, 1998). The uncoupling of sg mRNA transcription in vivo has also been achieved in an arterivirus, Equine arteritis virus, where mutation of two different proteins that contain zinc-binding domains, nsp1 and nsp10 (neither is the RdRp), caused specific defects in the DTS mechanism of sg mRNA transcription (van Marle et al, 1999a, 1999b; Tijms et al, 2001). These examples illustrate that the II and DTS transcriptional processes in these viruses are complex and involve multiple viral proteins; however, with the exception of SINV nsP4, the specific roles played by these assorted viral factors remain to be determined.

Before this study, nothing was known about the protein components involved in the PT mechanism. Accordingly, the results from this study are significant in several respects. The TBSV RdRp represents the first protein factor to be identified as a key regulator of the PT mechanism of sg mRNA transcription—for any virus. Also noteworthy is that this is the first demonstration, for a plant virus, that genome replication can be efficiently uncoupled—at the protein level—from sg mRNA transcription. Moreover, this is the only example of a viral RdRp specifically modulating sg mRNA synthesis in vivo. These findings increase our general understanding of the PT mechanism and provide novel insights into fundamental viral RdRp activities.

Role of the RdRp in the PT transcriptional mechanism

The PT mechanism involves a defined series of steps and, through systematic analyses, we have identified those that are facilitated by the C-terminus of the RdRp. As summarized in Figure 9B, our results indicate major involvement at the level of sg mRNA minus-strand production and a possible lesser role with subsequent use of the sg mRNA promoter.

Viral RdRps take on a general right-hand topology that includes fingers, palm and thumb domains (Ferrer-Orta et al, 2006; Figure 9B). Our results indicate that in TBSV, the extreme C-terminus mediates efficient RdRp detection of the base paired components of the RNA attenuation signals (Figure 9Bi). Accordingly, the important C-terminal residues must either allow the RdRp to communicate directly with the RNA structures or mediate an indirect interaction via an auxiliary factor(s). Active tombusvirus replicase complexes purified from transfected yeast cells contain at least four different host proteins (in addition to p33 and p92) (Serva and Nagy, 2006) and can direct complementary strand synthesis in vitro when incubated with exogenous viral RNA templates (Serva and Nagy, 2006). However, this extract, as well as similar replicase extracts from plants, is thus far unable to recognize the RNA attenuation signals for sg mRNA transcription in vitro (PD Nagy, personal communication). Therefore, either the extracts are missing a key factor(s) or the isolated complexes are perturbed in a way that inhibits this process. If the RdRp interacts directly with the attenuation signal, the C-terminal residues could function to organize the RdRp into a conformation that induces it to pause when it encounters the attenuation signal—thus providing an opportunity for termination.

Results from the spacer analysis revealed similar length requirements for wt and mutant RdRps (Figure 6), indicating that the C-terminal residues are not involved in defining the span of intervening sequence that is optimal for function. Conversely, the mutant RdRp showed altered positions of minus-strand termination as well as enhanced incorporation of non-templated residues (Figure 4B). The latter activity is a known property of viral RdRps (Nagy and Simon, 1997) and, for TBSV, C-terminal modifications appear to enhance this feature. For the wt RdRp, ∼60% of its minus-strand 3′-ends corresponded to the initiating nucleotide. In contrast, only ∼30% of the 3′-ends generated by the mutant RdRp mapped to this position (Figure 4B). Since aberrant 3′-termini negatively affect promoter utilization in TBSV, the higher proportion of 3′-extensions generated by the mutant RdRp could largely account for the proportionally greater reduction in sg mRNA accumulation—versus corresponding minus-strands (Figure 9Bii). In some cases, this imbalance may also be related to reduced ability of certain C-terminally truncated RdRps (e.g., Cd4) to utilize the sg mRNA promoter (Figure 9Biii). Thus, the combined effect of several distinct defects likely account for the overall reductions in sg mRNA accumulation levels (Figure 9B).

Collectively, these studies have provided important new mechanistic insights into the role of the RdRp in mediating sg mRNA transcription under physiological conditions (i.e., in host cell infections). Specifically, the RdRp was found to (i) mediate efficient generation of minus-strand sg mRNA templates, (ii) facilitate accurate termination of minus-strands, and (iii) possibly promote efficient utilization of the wt sg mRNA promoter (Figure 9B).

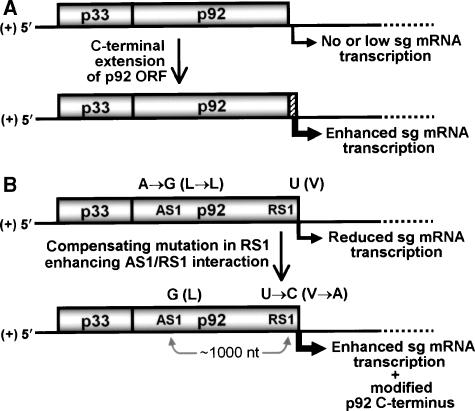

Origin and evolution of sg mRNA transcription in TBSV

In a theoretical evolutionary model, it is logical to suppose that replication of a viral RNA genome (e.g., encoding a polyprotein) preceded the emergence of sg mRNA transcription (Tijms et al, 2001). Indeed, for the PT mechanism, this scenario is supported by our demonstration that replication can be effectively uncoupled from transcription. How then was sg mRNA transcription introduced into a viral replication system? The necessity of the C-terminus for transcription, but not for replication, suggests a potential pathway for gaining (or enhancing) sg mRNA transcription through the C-terminal extension of a more primitive tombusvirus RdRp. Although other possibilities exist, this type of read-through genetic mechanism has been implicated in the evolution of cellular proteins derived from humans (Fiddes and Goodman, 1980), Drosophila (Levine et al, 2006) and yeast (Namy et al, 2003).

In our proposed viral scenario, the primitive RdRp would originally have limited or no ability to recognize RNA attenuation signals. However, in gaining this function—via extension of its ORF—it would then be able to efficiently generate smaller minus-sense RNAs that could potentially be used as templates to synthesize a new class of smaller viral RNA (i.e., sg (m)RNAs; Figure 10A). This scheme is attractive because the RdRp would not need to gain new structural features to allow it to bind to a distinct sg mRNA promoter (as is the case for SINV; Li and Stollar, 2004), since it would utilize the same type of plus-strand promoter that functions for viral genome replication (Lin and White, 2004). In using a common type of plus-strand promoter for both processes, the RdRp adaptation necessary to gain the ability to transcribe sg mRNAs would be reduced. In this regard, the biogenesis of the PT system represents a simple but ingenious mechanism for relocating dormant internally positioned sg mRNA promoters to the 3′ termini of minus-strand templates—where they become highly active.

Figure 10.

Models for RdRp evolution. (A) Gain or enhancement of sg mRNA transcription function via extension of the p92 RdRp ORF. The 5′ portion of the TBSV genome is shown schematically. The genome at the top encodes a primitive RdRp lacking notable transcriptional activity, whereas that below contains a C-terminally extended p92 ORF (hatched box) that confers enhanced transcriptional activity. See text for details. (B) Influence of a long-distance RNA–RNA interaction (i.e., global folding) on the structure of the C-terminus of the p92 RdRp. The genome at the top has gained an A-to-G nucleotide substitution in AS1, whereas that below contains a second compensating mutation in RS1. Nucleotide substitutions are indicated along with effects on the corresponding amino-acid sequences (in parentheses). See text for details.

Global virus genome structure influences RdRp evolution

Another intriguing feature of the RdRp C-terminus is that the sequence encoding it is also the RS1 transcriptional regulatory element (Figure 2A). This relationship is further complicated by the necessity for the RS1 element to base pair with its AS1 partner sequence located ∼1000 nt upstream. This convoluted interdependence suggests that AS1, via its basepairing requirement with RS1, could influence the coding of the RdRp C-terminus—and thus the structure and function of this protein. The coexistence and coevolution of localized functional RNA elements and their corresponding coding sequences in mRNAs has been explored previously both in silico (Konecny et al, 2000; Pedersen et al, 2004) and in natural populations (Parmley et al, 2007). However, the concept that an RNA sequence can act via a long-range tertiary RNA–RNA interaction to influence protein coding at a distal location has not been investigated and, as described below, our data support the occurrence of such an event in nature.

As mentioned earlier, two tombusviruses (CBV and MNeSV) contain a GC base pair in the AS1/RS1 interaction in place of the AU base pair in TBSV (also present in nine other tombusviruses; not shown). Considering that 10 out of 14 sequenced tombusviruses contain the AU base pair, it is reasonable to believe that the GC variant arose from the former ‘consensus' base pair. This concept is also supported by the observation that the introduction of the GC base pair into a TBSV context induced slightly improved levels of sg mRNA1 accumulation (i.e., ∼113%; Figure 8), which would presumably confer enhanced fitness by providing more coat protein for virus assembly. In terms of the order of appearance of the individual substitutions, the presence of GU wobble base pairs in two tombusviruses (Cucumber necrosis virus (CNV) and TBSV-statice isolate (TBSV-S); refer to Figure 8A) suggests that the A-to-G substitution at the distal AS1 occurred first, followed by a compensating U-to-C at RS1 (Figure 10B). This order is also supported experimentally in TBSV, where the GU base pair-containing intermediate was found to be somewhat compromised (∼92%), but considerably more transcriptionally active than the AC mismatch-containing intermediate (∼10%) (Figure 8). The greater functionality of the GU wobble base pair would aid it competitively and allow it to persist long enough—as suggested by its existence in natural tombusvirus populations of CNV and TBSV-S—for the compensatory change to occur (Rousset et al, 1991). Therefore, following this line of reasoning, the substitution at the distal AS1 element would initiate the cascade of events that lead to the modification of the C-terminus of the RdRp encoded ∼1000 nt downstream (Figure 10B). Moreover, as mfold analysis predicts formation of the AS1/RS1 interaction in the context of a folded full-length TBSV RNA genome (Choi and White, 2002), these data suggest a previously unappreciated role for the global structure of an RNA virus genome in modulating viral protein evolution. The implications of this finding are also relevant to understanding evolutionary processes in other viruses such as Hepatitis C virus (Kim et al, 2003), Dengue virus (Alvarez et al, 2005), Flock house virus (Lindenbach et al, 2002) and Barley yellow dwarf virus (Miller and White, 2006), all of which contain functional long-distance RNA–RNA interactions involving coding regions. Furthermore, as there is computational (Meyer and Miklos, 2005) and experimental (Nackley et al, 2006) evidence for functional higher-order RNA structures in coding regions of cellular mRNAs, the relevance of this concept will likely extend beyond viral messages.

Materials and methods

Plasmid construction

Constructs previously described that were used in this study include: T100, the wt TBSV genome construct (Hearne et al, 1990); AS1m1 and Psg1-S5, modified TBSV genomes with 3-nt substitutions in AS1 (Choi and White, 2002) or five silent mutations in RS1 (Zhang et al, 1999), respectively; a TBSV replicon corresponding to a prototypical TBSV DI RNA (Wu et al, 2001) and HL47, a replicon containing a sg RNA promoter as its plus-strand promoter (Lin and White, 2004). Based on the above constructs, additional modifications were introduced and the relevant differences are presented in the accompanying figures. All modifications were made using PCR-based mutagenesis and standard cloning techniques (Sambrook et al, 1989). The PCR-derived regions introduced into the constructs were sequenced completely to ensure that only the intended modifications were present.

In vitro transcription, protoplast inoculation, and RNA isolation

In vitro RNA transcripts of viral RNAs were generated using T7 RNA polymerase as described previously (Wu et al, 2001). Preparation and inoculation of cucumber protoplasts and extraction of total nucleic acids were carried out as outlined in Choi and White (2002). Briefly, isolated cucumber protoplasts (3 × 105) were transfected with RNA transcripts (3 μg for genomic RNA; 1 μg for replicon RNA). The transfected protoplasts were incubated at 22°C for 24 h under constant lighting. Total nucleic acids were isolated and analyzed as described below.

Viral RNA analysis

Total nucleic acid preparations isolated from virus-inoculated protoplasts were subjected to northern blot analysis for detection of plus- and minus-strand viral RNAs as described previously (Choi and White, 2002). Nucleic acids were either treated with glyoxal and separated in 1.4% agarose gels, or denatured in formamide-containing buffer and separated in 4.5% polyacrylamide-8 M urea gels (Figures 3C and 7B only). Equal loading of lanes was confirmed before transfer via staining the gels with ethidium bromide. Following electrophoretic transfer to nylon membranes, positive-strand viral RNAs were detected using 32P-labeled DNA oligonucleotide probes and negative strands were detected by RNA riboprobe. Relative isotopic levels were determined using PharosFx Plus Molecular Imager (BioRad).

Sequence analysis of the 3′ termini of minus-strand sg mRNA2 was accomplished by ligation with a phosphorylated oligonucleotide with RNA ligase, reverse transcription–PCR amplification of the cDNA, and subsequent cloning and sequencing (Lin and White, 2004).

RNA structures were predicted and free energy changes calculated using mfold version 2.3 (Mathews et al, 1999; Zuker et al, 1999).

Viral protein analysis

After a 24-h incubation period, protoplasts were vortexed in 50 μl 2 × SDS–PAGE loading buffer for 30 s, followed by heating at 100°C for 5 min. Proteins were separated on 12% SDS–PAGE. After electrotransfer to a nitrocellulose membrane, p33 and p92 were detected using a polyclonal antibody against a peptide of p33 (McCartney et al, 2005). HRP-conjugated secondary antibody (Sigma, A0545) and Amersham ECL Plus western blotting detection reagents (GE Healthcare, RPN 2132) were used for further processing of the blot.

Acknowledgments

We thank Robert Mullen for anti-p33/92 antiserum, Han-xin Lin for technical assistance, and members of our laboratory for reviewing the manuscript. This work was supported by NSERC, a Steacie Fellowship, and a Canada Research Chair.

References

- Alvarez DE, Lodeiro MF, Luduena SJ, Pietrasanta LI, Gamarnik AV (2005) Long-range RNA–RNA interactions circularize the dengue virus genome. J Virol 79: 6631–6643 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buck KW (1996) Comparison of the replication of positive-stranded RNA viruses of plants and animals. Adv Virus Res 47: 159–251 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi IR, Ostrovsky M, Zhang G, White KA (2001) Regulatory activity of distal and core RNA elements in Tombusvirus subgenomic mRNA2 transcription. J Biol Chem 276: 41761–41768 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi IR, White KA (2002) An RNA activator of subgenomic mRNA1 transcription in tomato bushy stunt virus. J Biol Chem 277: 3760–3766 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cowley JA, Dimmock CM, Walker PJ (2002) Gill-associated nidovirus of Penaeus monodon prawns transcribes 3′-coterminal subgenomic mRNAs that do not possess 5′-leader sequences. J Gen Virol 83: 927–935 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrer-Orta C, Arias A, Escarmis C, Verdaguer N (2006) A comparison of viral RNA-dependent RNA polymerases. Curr Opin Struct Biol 16: 27–34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiddes JC, Goodman HM (1980) The cDNA for the beta-subunit of human chorionic gonadotropin suggests evolution of a gene by readthrough into the 3′-untranslated region. Nature 286: 684–687 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gowda S, Satyanarayana T, Ayllon MA, Albiach-Marti MR, Mawassi M, Rabindran S, Garnsey SM, Dawson WO (2001) Characterization of the cis-acting elements controlling subgenomic mRNAs of citrus tristeza virus: production of positive- and negative-stranded 3′-terminal and positive-stranded 5′-terminal RNAs. Virology 286: 134–151 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hearne PQ, Knorr DA, Hillman BI, Morris TJ (1990) The complete genome structure and synthesis of infectious RNA from clones of tomato bushy stunt virus. Virology 177: 141–151 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwamoto T, Mise K, Takeda A, Okinaka Y, Mori K, Arimoto M, Okuno T, Nakai T (2005) Characterization of Striped jack nervous necrosis virus subgenomic RNA3 and biological activities of its encoded protein B2. J Gen Virol 86: 2807–2816 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim YK, Lee SH, Kim CS, Seol SK, Jang SK (2003) Long-range RNA–RNA interaction between the 5′ nontranslated region and the core-coding sequences of hepatitis C virus modulates the IRES-dependent translation. RNA 9: 599–606 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konecny J, Schoniger M, Hofacker I, Weitze MD, Hofacker GL (2000) Concurrent neutral evolution of mRNA secondary structures and encoded proteins. J Mol Evol 50: 238–242 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaStarza MW, Lemm JA, Rice CM (1994) Genetic analysis of the nsP3 region of Sindbis virus: evidence for roles in minus-strand and subgenomic RNA synthesis. J Virol 68: 5781–5791 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levine MT, Jones CD, Kern AD, Lindfors HA, Begun DJ (2006) Novel genes derived from noncoding DNA in Drosophila melanogaster are frequently X-linked and exhibit testis-biased expression. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 103: 9935–9939 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li ML, Stollar V (2004) Identification of the amino acid sequence in Sindbis virus nsP4 that binds to the promoter for the synthesis of the subgenomic RNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 101: 9429–9434 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li ML, Stollar V (2007) Distinct sites on the Sindbis virus RNA-dependent RNA polymerase for binding to the promoters for the synthesis of genomic and subgenomic RNA. J Virol 81: 4371–4373 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin HX, White KA (2004) A complex network of RNA–RNA interactions controls subgenomic mRNA transcription in a tombusvirus. EMBO J 23: 3365–3374 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin HX, Xu W, White KA (2007) A multicomponent RNA-based control system regulates subgenomic mRNA transcription in a tombusvirus. J Virol 81: 2429–2439 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindenbach BD, Sgro JY, Ahlquist P (2002) Long-distance base pairing in Flock House virus RNA1 regulates subgenomic RNA3 synthesis and RNA2 replication. J Virol 76: 3905–3919 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathews DH, Sabina J, Zuker M, Turner DH (1999) Expanded sequence dependence of thermodynamic parameters improves prediction of RNA secondary structure. J Mol Biol 288: 911–940 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCartney AW, Greenwood JS, Fabian MR, White KA, Mullen RT (2005) Localization of the Tomato bushy stunt virus replication protein p33 reveals a peroxisome-to-endoplasmic reticulum sorting pathway. Plant Cell 17: 3513–3531 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer IM, Miklos I (2005) Statistical evidence for conserved, local secondary structure in the coding regions of eukaryotic mRNAs and pre-mRNAs. Nucleic Acids Res 33: 6338–6348 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller WA, Dreher TW, Hall TC (1985) Synthesis of brome mosaic virus subgenomic RNA in vitro by internal initiation on (−)-sense genomic RNA. Nature 313: 68–70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller WA, Koev G (2000) Synthesis of subgenomic RNAs by positive-strand RNA viruses. Virology 273: 1–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller WA, White KA (2006) Long-distance RNA–RNA interactions in plant virus gene expression and replication. Annu Rev Phytopathol 44: 447–467 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nackley AG, Shabalina SA, Tchivileva IE, Satterfield K, Korchynskyi O, Makarov SS, Maixner W, Diatchenko L (2006) Human catechol-O-methyltransferase haplotypes modulate protein expression by altering mRNA secondary structure. Science 314: 1930–1933 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagy PD, Simon AE (1997) New insights into the mechanisms of RNA recombination. Virology 235: 1–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Namy O, Duchateau-Nguyen G, Hatin I, Hermann-Le Denmat S, Termier M, Rousset JP (2003) Identification of stop codon readthrough genes in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Nucleic Acids Res 31: 2289–2296 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panavas T, Pogany J, Nagy PD (2002) Analysis of minimal promoter sequences for plus-strand synthesis by the Cucumber necrosis virus RNA-dependent RNA polymerase. Virology 296: 263–274 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parmley JL, Urrutia AO, Potrzebowski L, Kaessmann H, Hurst LD (2007) Splicing and the evolution of proteins in mammals. PLoS Biol 5: e14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pasternak AO, van den Born E, Spaan WJ, Snijder EJ (2001) Sequence requirements for RNA strand transfer during nidovirus discontinuous subgenomic RNA synthesis. EMBO J 20: 7220–7228 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen JS, Forsberg R, Meyer IM, Hein J (2004) An evolutionary model for protein-coding regions with conserved RNA structure. Mol Biol Evol 21: 1913–1922 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rousset F, Pelandakis M, Solignac M (1991) Evolution of compensatory substitutions through G–U intermediate state in Drosophila rRNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 88: 10032–10036 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sambrook J, Fritsch EF, Maniatis T (1989) Molecular Cloning: a Laboratory Manual, 2nd edn. Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press [Google Scholar]

- Sawicki SG, Sawicki DL (1998) A new model for coronavirus transcription. Adv Exp Med Biol 440: 215–219 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serva S, Nagy PD (2006) Proteomics analysis of the tombusvirus replicase: Hsp70 molecular chaperone is associated with the replicase and enhances viral RNA replication. J Virol 80: 2162–2169 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sit TL, Vaewhongs AA, Lommel SA (1998) RNA-mediated transactivation of transcription from a viral RNA. Science 281: 829–832 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smits SL, van Vliet AL, Segeren K, el Azzouzi H, van Essen M, de Groot RJ (2005) Torovirus non-discontinuous transcription: mutational analysis of a subgenomic mRNA promoter. J Virol 79: 8275–8281 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sola I, Moreno JL, Zuniga S, Alonso S, Enjuanes L (2005) Role of nucleotides immediately flanking the transcription-regulating sequence core in coronavirus subgenomic mRNA synthesis. J Virol 79: 2506–2516 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suopanki J, Sawicki DL, Sawicki SG, Kaariainen L (1998) Regulation of alphavirus 26S mRNA transcription by replicase component nsP2. J Gen Virol 79: 309–319 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tijms MA, van Dinten LC, Gorbalenya AE, Snijder EJ (2001) A zinc finger-containing papain-like protease couples subgenomic mRNA synthesis to genome translation in a positive-stranded RNA virus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 98: 1889–1894 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Marle G, Dobbe JC, Gultyaev AP, Luytjes W, Spaan WJ, Snijder EJ (1999a) Arterivirus discontinuous mRNA transcription is guided by base pairing between sense and antisense transcription-regulating sequences. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 96: 12056–12061 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Marle G, van Dinten LC, Spaan WJ, Luytjes W, Snijder EJ (1999b) Characterization of an equine arteritis virus replicase mutant defective in subgenomic mRNA synthesis. J Virol 73: 5274–5281 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Vliet AL, Smits SL, Rottier PJ, de Groot RJ (2002) Discontinuous and non-discontinuous subgenomic RNA transcription in a nidovirus. EMBO J 21: 6571–6580 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White KA (1996) Formation and evolution of tombusvirus defective interfering RNAs. Semin Virol 7: 409–416 [Google Scholar]

- White KA (2002) The premature termination model: a possible third mechanism for subgenomic mRNA transcription in (+)-strand RNA viruses. Virology 304: 147–154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White KA, Nagy PD (2004) Advances in the molecular biology of tombusviruses: gene expression, genome replication and recombination. Prog Nucleic Acids Res Mol Biol 78: 187–226 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu B, Vanti WB, White KA (2001) An RNA domain within the 5′ untranslated region of the tomato bushy stunt virus genome modulates viral RNA replication. J Mol Biol 305: 741–756 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang G, Slowinski V, White KA (1999) Subgenomic mRNA regulation by a distal RNA element in a (+)-strand RNA virus. RNA 5: 550–561 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuker M, Mathews DH, Turner DH (1999) Algorithms and thermodynamics for RNA secondary structure prediction: a practical guide. In: RNA Biochemistry and Bio/Technology, Barciszewski J, Clark BFC (eds), pp 11–43. Dordrecht/Norwell, MA: Kluwer Academic Publishers [Google Scholar]