Abstract

In the future, there will be an increased number of cervical revision surgeries, including 4- and more-levels. But, there is a paucity of literature concerning the geometrical and clinical outcome in these challenging reconstructions. To contribute to current knowledge, we want to share our experience with 4- and 5-level anterior cervical fusions in 26 cases in sight of a critical review of literature. At index procedure, almost 50% of our patients had previous cervical surgeries performed. Besides failed prior surgeries, indications included degenerative multilevel instability and spondylotic myelopathy with cervical kyphosis. An average of 4.1 levels was instrumented and fused using constrained (26.9%) and non-constrained (73.1%) screw-plate systems. At all, four patients had 3-level corpectomies, and three had additional posterior stabilization and fusion. Mean age of patients at index procedure was 54 years with a mean follow-up intervall of 30.9 months. Preoperative lordosis C2-7 was 6.5° in average, which measured a mean of 15.6° at last follow-up. Postoperative lordosis at fusion block was 14.4° in average, and 13.6° at last follow-up. In 34.6% of patients some kind of postoperative change in construct geometry was observed, but without any catastrophic construct failure. There were two delayed unions, but finally union rate was 100% without any need for the Halo device. Eleven patients (42.3%) showed an excellent outcome, twelve good (46.2%), one fair (3.8%), and two poor (7.7%). The study demonstrated that anterior-only instrumentations following segmental decompressions or use of the hybrid technique with discontinuous corpectomies can avoid the need for posterior supplemental surgery in 4- and 5-level surgeries. However, also the review of literature shows that decreased construct rigidity following more than 2-level corpectomies can demand 360° instrumentation and fusion. Concerning construct rigidity and radiolographic course, constrained plates did better than non-constrained ones. The discussion of our results are accompanied by a detailed review of literature, shedding light on the biomechanical challenges in multilevel cervical procedures and suggests conclusions.

Keywords: Cervical spine, Multilevel, Fusion, Instrumentation

Introduction

Four- and 5-level anterior arthrodeses of the cervical spine are rare surgeries even in busy spine centers. Whereas sufficient literature covers 1-, 2-, and 3-level anterior surgeries, the literature lacks comprehensive samples reporting the outcome following the challenge of 4- and 5-level anterior decompression, fusion and instrumentation [96]. However, in light of the increasing number of 2- and 3-level surgeries performed [66, 122], the need for redo surgeries will increase in the future, with extension of anterior fusion length resulting in salvage 4- and 5-level procedures [40]. Unfortunately, the biomechanical performance in vivo as well as the clinical details of the geometrical behaviour of multilevel ACPS remain incompletely documented [49]. There is an ongoing debate with increasing biomechanical backround as to whether anterior, posterior, or combined 360° stabilization and fusion should be recommended. Distinct indications could not be evidenced, yet.

Nowadays, multilevel (multilevel = more than two motion levels involved) discectomies and corpectomies merely are required for the cure of degenerative disorders, posttraumatic or postsurgical deformities, and neoplasy related instabilities [10, 23, 26, 96, 110]. In these situations diffuse spinal canal narrowing and kyphosis are common, and the surgical options are essentially anterior [70, 110]. In the past, the rate of complications with non-instrumented multilevel anterior cervical fusions has raised concerns [96], and necessitated prolonged immobilization with the Halo device. Thus it was desirable, and infact, using instrumentations gained an increase in lordotic curvature, as well as an increased primary stability with higher fusion rates [12, 22, 37, 49, 57, 76, 96, 98]. However, it was scrutinized that with the advantage of anterior cervical spine instrumentations came their own shortcomings, such as implant related complications [12, 20, 37, 115, 117]. We could not confirm this observation in general, yet to be proven with a thorough evaluation of our clinical and radiographical results.

Within the long-term performance following anterior multilevel decompressive surgeries, it remains an open question wether reconstruction of ‘normal’ cervical lordosis is imperative, and how much lordosis should be achieved. The literature offers some hints that reconstruction of cervical lordosis might be favourable concerning clinical outcome and neurologic recovery [32, 70, 72, 113]. However, the question of any influence of a distinct amount of lordotic realignement following the reconstruction of the multilevel decompressed cervical spine demands further investigation [12].

To address some of the puzzling questions in multilevel anterior cervical surgeries, we performed a study focussing on the clinical and radiographical outcome of 4- and 5-level instrumented fusions. Observations on the postoperative geometrical changes of the fusion construct and a comprehensive review of literature might enlarge further discussions concerning multilevel anterior cervical surgeries.

Methods and materials

This study is a consecutive case review of 26-instrumented 4- and 5-level anterior cervical fusions. The patients’ detailed medical records and radiographic studies were reviewed including demographics, diagnosis, medical history, as well as operative details and clinical outcome. Standing plain lateral radiographs obtained before and after index procedure, at 3–4 months, and at last follow-up visits were subsequently used to quantify changes in cervical lordosis and geometry of the fusion construct. Our study protocol determined a minimum follow-up of 6 months on basis of prior experience demonstrating that significant changes in construct geometry occur within about 3 months after surgery [23, 28, 36, 49, 111, 126]. We evaluated geometrical changes in sagittal plane and cervical lordosis with the widespread technique of Harrison et al. [38, 44, 111, 113, 123], using the angle formed between the tangential lines on the posterior edge of the vertebral bodies C2-7. In all 26 patients using the radiographs or digital imaging enhanced techniques relevant bony landmarks and fused levels were discernible, at least to one half of the posterior vertebral body wall at T1. Inferiorly to T1, disc space and vertebral body was only visible on tomographies in seven cases at last follow-up to determine ADD. The latter was defined as any significant change at last follow-up compared to index procedure with signs of DCI, loss of segmental hight, or kyphosis.

As concerns ongoing discussions on the benefits and drawbacks of CS- versus NC-plates used, we focused on changes in construct geometry, particularly at the screw-plate and screw-bone interfaces following ACPS. Lordosis at fusion block Cx − Cx+4/x+5 was measured at aforementioned intervals with the technique of Harrison et al. [44].

Normal values of a lordotic curve C2-7 have been reported to be about 24° [41] with a range of 10°–34° [3, 38, 42, 43, 81]. In our study, we determined an angle of <10° denoting a “hypolordotic” curvature, and <0° a “kyphotic” curvature at last follow-up. All angular measurements were done by one of the authors (H.K.). Significant changes of all angular measurements during the radiographic course were determined as such with ≥4° [41].

Radiographic determination of union and osseus incorporation of TMCs based on (1) the continuity of the trabeculae and/or complete osseus union at the graft/bone interface; (2) progressed bony trabeculation at the cage/bone interface without signs of lytic lining at the cage; (3) absence of lucencies or halo formation around the graft/cage with presence of bridging bone incorporating the graft/cage; (4) gross bony trabeculation on tomography or CT-films if there was any question concerning union.

We assessed clinical outcome with modified Odom criteria [6, 28, 49, 84]. Outcome was determined as excellent, good, fair, and poor. In those patients with myelopathia, excellent and good outcomes were assigned if patients depicted significant decrease of preoperative sensomotoric deficits in terms of two and one Nurick grades [83], respectively. Relevant patient characteristics and measurements are summarized in Tables 1 and 2.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics in 26 instrumented 4- and 5-level anterior cervical fusions

| Pt | Age | Sex | PACS | Fused levels | Anterior plate | Anterior and posterior techniques | FU | TCL C2-7 preop | TCL C2-7 at FU | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 50 | M | C3-7 | Δ C3-7 | ACDF C3-7, ICG | 12 | 6 | 8 | Excel | |

| 2 | 53 | F | C2-7 | □ C2-7 | ACDF C2-7, ICG | 6 | 2 | 17 | Good | |

| 3 | 57 | M | C3-7 | Δ C3-7 | ACDF C3-7, TMC C6-7, ICG | 11 | 4 | 17 | Good | |

| 4 | 53 | M | C3-7 | □ C3-7 | ACDF C3-7, ICG | 15 | 20.5 | 28 | Excel | |

| 5 | 52 | M | C3-7 | □ C3-7 | ACDF C3-7, ICG | 90 | 19 | 38 | Fair | |

| 6 | 56 | M | X | C3-7 | □ C3-7 | ACDF C3-4, Corp 5-6, TMCs C3-7; ICG; Post fusion C3-7 | 96 | −2 | 8 | Poor |

| 7 | 62 | F | C3-7 | □ C3-7 | ACDF C3-7, ICG | 6 | 2 | 8 | Good | |

| 8 | 53 | F | C3-7 | □ C3-7 | ACDF C3-7, ICG | 12 | 4 | 11 | Good | |

| 9 | 56 | M | X | C3-7 | □ C3-7 | IR, ACDF C3-7, ICG | 65 | 21 | 28 | Poor |

| 10 | 14 | M | C3-7 | □ C3-7 | Corp C4-6, ICG | 160 | −14 | −16 | Excel | |

| 11 | 57 | F | X | C3-7 | Δ C3-7 | IR C3-7, Corp C4, ACDF C5-7, ICG | 13 | −10 | 0 | Excel |

| 12 | 54 | M | C4-T1 | ▶ C4-T1 | ACDF C4-T1, TMC C7-T1, ICG | 6 | 10 | 23 | Excel | |

| 13 | 45 | F | X | C3-7 | ▶ C3-7 | IR C5-6, ACDF C3-7, TMC 5-6, ICG | 6 | 6 | 22 | Excel |

| 14 | 55 | F | X | C3-7 | □ C3-7 | ACDF C3-4, TMC C3-4, Corp C5-6, TMC C4-7, CB | 18 | 4 | 10 | Good |

| 15 | 52 | F | C4-T1 | □ C4-T1 | ACDF C4-T1, ICG | 20 | 16 | 15 | Good | |

| 16 | 59 | M | X | C4-T1 | □ C4-T1 | IR, ACDF C4-T1 , ICG | 30 | 14 | 20 | Good |

| 17 | 52 | F | C3-7 | □ C3-7 | ACDF C3-7, ICG | 106 | 0 | 14 | Excel | |

| 18 | 55 | M | C3-7 | ▶ C3-7 | ADF C3-7, TMC C6-7, ICG | 24 | 4 | 20 | Excel | |

| 19 | 62 | M | X | C3-7 | □ C3-7 | IR, Corp C4-6, ICG; Post fusion C3-7 | 6 | 0 | −10 | Good |

| 20 | 69 | F | C3-7 | Δ C3-7 | ACDF C3-7, TMCs C4-7, ICG | 8 | 8 | 12 | Excel | |

| 21 | 50 | M | C3-7 | ▶ C3-7 | Corp C4-6, TMC C3-7, ICG; Post fusion c3-7 | 6 | 14 | 22 | Good | |

| 22 | 53 | M | X | C3-7 | □ C3-7 | IR, ACDF C3-7, ICG | 21 | 7 | 22 | Excel |

| 23 | 63 | F | C3-7 | □ C3-7 | ACDF C3-7, ICG | 36 | 15 | 30 | Excel | |

| 24 | 70 | M | C3-T1 | Δ C3-4, ▶ C4-T1a | ACDF C3-T1, ICG | 6 | 9 | 31 | Good | |

| 25 | 52 | M | X | C3-7 | ▶ C3-7 | IR, ACDF C3-7, TMC C3-7 , ICG | 18 | 4 | 11.5 | Good |

| 26 | 52 | F | X | C3-7 | ▶ C3-7 | IR, Corp C4-6, TMC C3-7, ICG | 6 | 6 | 17 | Good |

FU = Follow-up; PACS = Previous anterior cervical surgery w/ fusion; ACDF = anterior cervical decompression and fusion, Δ = Alpha-plate (Stryker), non-constrained; □ = Strehli-plate (Stryker), non-constrained; ▶ = Reflex-plate (Stryker), constrained; ICG = Iliac Crest Graft; IR = Implant Removal; TCL = Total cervical lordosis C2-7: TMC = use of Titanium Mesh Cage

aCoupling of two anterior plates at C4 using a sandwhich-technique

Table 2.

Changes in total cervical lordosis C2-7 and lordosis at fusion block following 4- and 5-level fusions (in degrees); n = 26

| TCL preop | TCL postop | TCL 3 to 4 months FU | TCL last FU | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | 6.5 | 17.4 | 16.4 | 15.6 |

| SD | 8.4 | 9.3 | 10.6 | 12.0 |

| Range | −14 to 20.5 | −4 to 38 | −10 to 34 | −16 to 38 |

| Lordosis at FB postop | Lordosis at FB 3 to 4 months FU | Lordosis at FB last FU | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | 14.4 | 14.0 | 13.5 | |

| SD | 9.3 | 9.4 | 9.3 | |

| Range | −10 to 30 | −14 to 30 | −14 to 29 | |

Negative scale (- ) represents kyphotic angle, <0°

FB fusion block, FU follow-up, SD standard deviation, TCL total cervical lordosis C2-7

Surgical techniques and indications

In preoperative evaluation, including plain and dynamic cervical radiographs, CT-myelography or MRI, all but one patient had some form of hard and soft components of cervical stenosis. Spondylotic myeolopathy was present in 11 patients (42.3%) diagnosed either with MRI or electrophysiological testing. In 14 patients (53.8%), thoracic or thoracolumbar surgeries were performed previously to or after the index procedure at our institution (Fig. 1). Indications for multilevel surgery included symptomatic DCI and cervial stenosis with either radiculopathy, myelopathy, or axial neck pain as well as pseudoarthrosis, implant failure, or ADD following previous surgeries, and once a cervical congenital kyphotic deformity in a patient with neurofibromatosis (Fig. 2). Ten referred patients (38.5%) had a history of PACS with an anterior fusion length of 2.6 levels in average (range, 1–4). Two other patients had previous posterior surgery including a C1-2 fusion and C6-7 posterior nucleotomy, respectively.

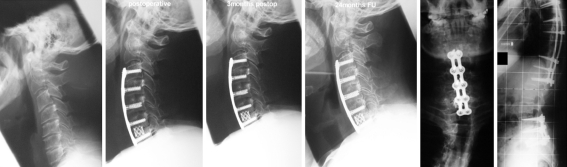

Fig. 1.

Case 23. A 55-years-old patient with DCI C3-7, axial neck pain, radiculopathia C6-8 left, and cervical kyphosis. There was no change in construct geometry following ACDF and stabilization with a CS-plate C3-7. A 24 months follow-up showed osseus union C3-7 and excellent clinical result. Patient also underwent correction of adult thoracic scoliosis and lumbar fusion with good clinical outcome

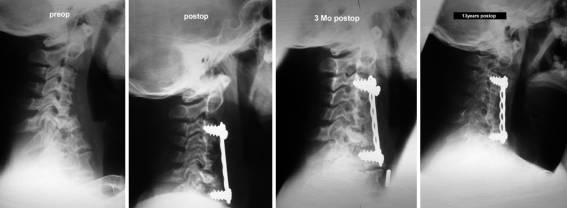

Fig. 2.

Case 12. A 14-years-old patient with neurofibromatosis, large thoracolumbar kyphoscoliosis, total kyphosis C2-7 with a sharp local rigid kyphosis C5-6. 3-level corpectomy with NC-plate C3-7 was performed. But, neutral sagittal balance could not be resotred. There was primary plate impingement C2-3 with further increase during clinial course and some rekyphosing at C5-6. At 13 years follow-up this satisfied patient showed an excellent clinical outcome

In those cases in which multilevel ACDF was feasible, arthrodesis was carried out using two bilaterally snug-fit impacted bicortical iliac crest grafts and/or TMC. If corpectomized levels had to be reconstructed, length adjusted iliac crest grafts or TMCs (Harms Surgical Titanium Mesh Cage, Depuy Spine, Limbach/Germany) were used, filled with corticocancellous bone from the iliac crest or corpectomy site-derived bone. Overall, TMCs were used in ten cases (38.5%). For multilevel decompression the authors prefer segmental discectomies, undercutting of the vertebral bodies, and/or if necessary by all means, performing corpectomies at the most severe involved levels. Semirigid followed by soft cervical collar usage was 3.6 months in average (range 3–6). In none of our cases a Halo device was applied. In 26 patients, the average number of anteriorly fused levels following the index procedure was 4.1. Once, the previous fusion C1-2 and ACDF with plate stabilization C2-6 resulted in a 6-level fusion block. Anterior plated fusion C3-7 was performed in 21 cases (80.8%), C4-T1 four times (15.4%), and each once C2-7 and C3-T1 (3.8%). In former times, NC-plates were applied in 19 cases (73.1%; Strehli-plate and Alpha-plate, Stryker®, Duisburg/Germany), and later on static CS-plates in seven (26.9%; Reflex™-plate; Stryker Spine®, Howmedica Osteonics, New Jersey/USA). In 19 cases (73.1%) 4- and 5-level ACDF using iliac crest grafts and/or TMC were performed (Figs. 3, 5). Hybrid reconstructions using discectomies and adjacent corpectomies at one to two levels were performed in three cases (11.5%). Four patients (15.4%) underwent 3-level corpectomies, whereas in one case with a hybrid 2-level corpectomy, and in two with a 3-level corpectomy additional posterior stabilization was scheduled early on (13.0%). Twice we used a LM-CSR (Stryker Oasys™, Stryker®, Duisburg/Germany), and once common LM-plates for posterior stabilization.

Fig. 3.

Case 33. PACS C3-6, radiculopathia C6-8 left with severe neck pain. At last follow-up there was solid osseus union following ACDF C3-7, maintained distraction using TMCs and CS-plate. There was no loss of construct geometry or lordosis. Patient showed good clinical outcome

Fig. 5.

Case 1. Patient with multisegmental DCI and block vertebra C2-3. He underwent 4-level ACDF and stabilization with a NC-plate. Follow-up at one year showed solid fusion. Patient was satisfied and showed excellent clinical result. Note subsidience with some telescoping and screw toggling at C6-7 early during postoperative course

Statistical analysis

To assess any statistically significant relations of radiological and clinical results, correlation analyses were done using Spearman’s correlation coefficient, and crosstabulation tables were analyzed using Fisher’s Exact and Pearson’s chi-square test. The significance of differences among means was analyzed with two-sided Student t tests. The level of significance was set at 5%. Data were analyzed using Statistica 6.1 (StatSoft, Tulsa, Oakland/USA).

Results

Demographics and union rate

Mean age of patients at index procedure was 54 ± 10 years (range 14–70). There were 15 male and 11 female patients with a mean follow-up of 30.9 months (range 6–160). In average, time to union was 3.6 months (range 2.5–5). In all patients a solid fusion and progressed bony incorporation at the graft/cage vertebral junctions was observed at last follow-up. With patient who depicted fair clinical outcome following a plated 4-level ACDF C3-7, there was suspicion of pseudoarthrosis C6-7 on lateral plain radiographs. However, scintigraphy, tomography, as well as CT-imaging revealed sufficient osseus trabeculation at 5 months follow-up. No further treatment was indicated, and poor outcome with suboccipital pain could be related to symptomatic arthrosis C1-2. In another ACDF C3-7 there was suspicion of delayed union at C4-6 at 3 months follow-up on plain radiographs. However, tomography demonstrated sufficient osseus trabeculation. Concerning TMC applied, they showed solid bony incorporation into adjacent vertebras without signs of instability or lytic lining at the cage/bone interfaces at last follow-up.

Medical and surgical complications

Following multilevel fusion ten patients (38.5%) displayed some sort of, mainly minor, complications: In one patient with a preoperative diagnosis of cardiac disease, postoperatively brady-tachyarrhytmia absoluta necessitated pace-maker implantation. Once a postoperative seroma following the additional posterior fusion indicated surgical revision. In two other patients postoperative hematoma at the site of iliac crest graft harvesting indicated surgical revision with uneventful clinical course afterwards. Once in a malnurished smoker with severe myelopathia recurrent deep infection at the posterior approach necessitated surgical revision twice. Finally, wounds healed uneventfully. Postoperative dysphagia was observed in four patients (15.4%). Symptoms resolved until 3–6 month follow-up. In the patient with severe myelopathia dysphagia and pneumonia necessitated temporary gastric tube feeding for 3 weeks. Postoperative hoarseness was observed in three patients (11.5%), and once a symptomatic anterior plate caused hoarseness with dysphagia, which both resolved after early implant removal. In the other patients hoarseness resolved during in hospital course or until clinical follow-up three to 6 months postoperatively. Otolaryngeal examinations showed intact RLN in all patients who presented with postoperative hoarseness.

Adjacent disc disease

Any kind of ADD was observed in three patients (19.2%): one patient with ACDF and stabilization using NC-plate C3-7 presented with symptomatic ADD and kyphosis C7-T1 5 years after index procedure. He underwent posterior fusion using spinous process wiring C5-T2. The wires fractured early during in hospital course and he underwent successful ACDF C7-T1 with LM-P posteriorly. But, at 90 months follow-up he displayed poor clinical outcome. In another patient primary plate impingement proximal at C2-3, and secondarily distal at C7-T1 caused ossification of the anterior longitudinal ligament C2-3, as well as ADD C7-T1. The third, resembling the only patient with plate-related symptoms of dysphagia, depicted proximal and distal primary plate-impingement following ACDF C4-T1. Dysphagia resolved completely following plate removal, however spontaneous fusion anteriorly at C3-4, and moderate ADD at T1-2 was observed at 20 months follow-up.

Overall, any form of adjacent-level impingement by the plate was seen in seven patients (26.9%), three can be classified as primary impingement, due to technical errors and worse visible landmarks at the CTJ, and four as secondary due to a change of construct geometry during clinical course. Two of the latter cases showed ADD at the last follow-up. However, all patients with any kind of plate impingement showed good or excellent clinical outcomes. Overall, two patients (7.7%) had further surgeries following 4- and 5-level anterior procedures because of ADD and a symptomatic plate, respectively. Two other patients (7.7%) depicted moderate atlantoaxial arthritis, with one of them having a good and the other a poor outcome complaining on significant suboccipital pain during head rotation.

Early and long-term changes of construct geometry

In nine out of the 26 patients (34.6%) some changes concerning construct geometry could be documented (Figs. 4, 5). An early change of lordosis (≥4°) at the fusion block was observed in seven patients (26.9%). Here, NC-plates were applied and average change of lordosis at fusion block was 5.4° (range 4–10°) postoperatively. Twice the lordosis increased, in the remaining cases there was loss of lordosis. Only one patient experienced a late loss of lordosis at fusion block (more than 3 months postoperatively). In eight patients (30.8%) some subsidence with telescoping of the grafts/cages and screw toggling was observed, more often encountered at the caudad end of the fusion construct. Telescoping was associated with either screw toggling at the plate-screw interface in NC-constructs, accompanied by secondary plate impingement on adjacent levels in 50%, or inside the end-vertebra at the bone-screw interface with the screws cutting through the cancellous bone. In five of these eight patients change of construct geometry was accompanied by a significant change (≥4°) of lordosis at fusion block, including one patient with a congenital rigid cervical kyphosis and 3-level corpectomy not undergoing supplemental posterior fusion (Fig. 2). Each once, a change of lordosis at fusion block occurred due to a slight kyphosis at the level with delayed bony consolidation, but without any distinctable change of the construct geometry, as well as in a 5-level ACDF due to multilevel subsidience at the fused levels. Interestingly, primary and secondary plate impingement showed a statistically significant correlation with changes of construct geometry (P = 0.002 and 0.008), as well as a reduced TCL C2-7 postoperatively (P = 0.031). This finding suggests that any kind of plate impingement can show unfavourable consequences on the constructed geometry and stability, as well as on the remaining adjacent motion segments, respectively. Oppositively, no change of construct geometry was observed in seven cases (26.9%) with CS-plates applied, once supplemented with posterior LM-CSR fixation. Accordingly, the use of CS-plates in conjunction with TMC showed a statistically significant decreased rate of change in construct geometry and changes at fusion block (P = 0.017).

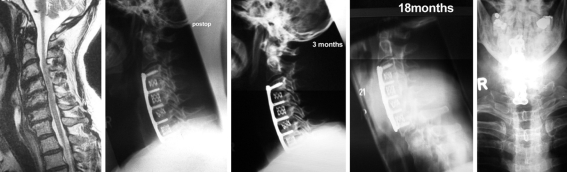

Fig. 4.

Case 17. PACS with non-instrumented ACDF C4-6. ADD at C6-7 and C3-4 with multilevel CS, radiculopathia of C6 and C7, and severe neck pain. At index procedure, hybrid technique with corpectomy of C5 and C6, and discectomy at C3-4 was performed. Intersegmental distraction was achieved using TMC at C3-4 and C4-7, packed with corpectomy site-derived bone. A NC-plate was applied. There was some early subsidience with minor plate impingement C7-T1, but no significant change of construct geometry. Of note, less lordosis was reconstructed using the rectangular cages and a non prebended plate. But, clinical outcome was good at last follow-up

As concerns 360° stabilizations, once a redo 3-level corpectomy reconstruction with week osteoporotic bone showed marked changes of construct geometry early postoperatively, indicating a second staged posterior stabilization. Another patient depicted early telescoping at C3-4 and screws in C3 cutting through the endplate of C3, followed by a secondary plate impingement at C2-3 with the TMC slightly backing out proximally during the postoperative course. Additionally, the patient underwent early scheduled posterior LM-CSR fixation C3-T1, and there was no further change in construct geometry. However, the patient showed severe neck pain at last follow-up. As expected, those 4-level fusions experiencing early secondary plate impingement and any change of construct geometry as a consequence of reduced rigidity of the instrumention showed an increased rate of posterior stabilizations performed (P = 0.008). Accordingly, with 3-level corpectomies there was an increased indication for supplemental posterior stabilization (P = 0.008). But, with the surgical strategies applied, there was no case of catastrophic graft/cage or plate dislodgement during inhospital stay. Of note, those patients showing any changes in construct geometry depicted a significantly increased incidence of any change or loss of lordosis at fusion block (P = 0.0003), as well as an associated change of TCL C2-7 during the clinical course (P = 0.0015). Correspondingly, the change of postoperative lordosis at fusions block showed a strong correlation with the change of TCL C2-7 (P = 0.00001). The findings suggest that diminishing the incidence of changes in construct geometry whilst increasing rigidity of multilevel anterior fusions might reduce the loss of lordosis postoperatively.

Early and long-term changes of sagittal alignment

In all 26 patients mean TCL C2-7 measured 6.5° preoperatively and 17.4° postoperatively, representing an increase of 10.9° (Table 2). Until last follow-up, mean loss of correction was 1.8° representing a final mean TCL of 15.6°. Postoperative lordosis at fusion block was 14.4° in average, and 13.6° at last follow-up (Table 2), which represents a slight decrease of 0.8°, only. In those patients in which multilevel ACDF was feasible, pre- and postoperative TCL C2-7 was significantly higher than in all other patients (P = 0.0094 and 0.0017), as it was the lordosis at fusion block postoperatively (P = 0.0025). Statistical calculations also showed that, in general, a higher preoperative TCL C2-7 correlated with a higher lordosis at fusion block postoperatively (P = 0.00047). Accordingly, an increased lordosis at fusion block postoperatively showed a statistically significant correlation with increased TCL C2-7 postoperatively (P = 0.00049). Opppositively, if lordosis of fusion block was low, it was the same with TCL C2-7 suggesting that there is less capability of the remaining motion segments in between C2 to T1 to compensate for a lack of postsurgical lordotic realignment following 4- or 5-level fusions. The average change in TCL pre- to postoperatively in 19 ACDF and one hybrid (1-level corpectomy) reconstruction was 12.0°, with a preoperative lordosis of 8.1° corrected to 20.1°. Mean cervical lordosis preoperatively was 1.0° in those patients undergoing 2- and 3-level corpectomies and 7.8° postoperatively, representating a mean correction of 6.8°, hence statistically significant less than compared to the former group (P = 0.0022). Of note, the evidence of PACS had no influence of the amount of correction achieved (P = 0.062). Overall, four patients (15.4%) showed a hypolordotic curve (0° < 10°), and two (7.7%) a kyphotic curve (<0°) at follow-up. Though, 20 patients (76.9%) showed a reconstructed lordotic cervical alignment at last follow-up.

Clinical results

According to the applied outcome measure, 11 patients (42.3%) showed an excellent outcome, 12 good (46.2%), one fair (3.8%), and two poor (7.7%). Due to the character of our study as a case retrospective review with comprehensive sample size (n = 26), and a low number of fair and poor outcomes, statistically significant correlations or prognostic factors for a diminished outcome could not be found. Although not statistically significant, it strikes that all patients with CS-plates applied showed a good or excellent clinical outcome. One of three patients with additional posterior fusion had a poor outcome with moderate to severe neck pain. Besides specific case histories mentioned, we did not find correlations between superior outcome and a distinct degree of TCL C2-7 achieved postoperatively. Surgical complications, such as temporary dysphagia or hoarseness, did not affect clinical outcome anyway.

At index procedure, myelopathia was present in 11 patients (42.3%) with an average of 2.4 points (range 1–5) according to the Nurick scale. It significantly decreased to an average of 0.8 points (range 0–4) in 10 patients at last follow-up (P = 0.01), whereas a late increase (Nurick 1 to 3) was documented in one patient, who presented also severe lumbar stenosis and associated myelopathy at 96 months follow-up. Noteably, we did not find any statistically significant correlation concerning neurologic recovery, change of construct geometry, and TCL C2-7 at last follow-up.

Discussion

In view of our results and challenges with 4- and 5-level cervical fusions, light is to be shed on the biomechanical background of successful multilevel anterior cervical procedures (Fig. 6).

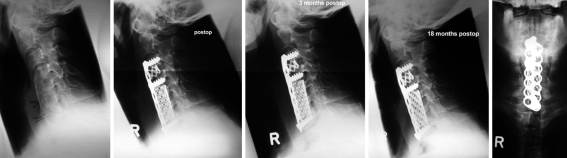

Fig. 6.

Case 16. PACS C5-6 and esophageal compression at C6-7, multisegmental DCI. At index procedure there was a kyphotic curvature at C2-5 with some TCL C2-7 of 6°. After implant removal C5-6, ACDF C3-7 was performed and a CS-plate applied. Follow-up after 3 and 6 months depicted solid osseus union C3-7, excellent clinical result with no loss of reconstructed TCL C2-7

Biomechanical considerations

Although using plates with rigid screw-plate locking mechanisms, reports on graft, cage, and plate failures particularly in multilevel corpectomies raised concerns on the limitations of these devices [117]. Several investigators confirmed complications frequently encountered with multilevel strut grafting and end-construct plate fixation spanning the strut graft without posterior fixation (graft/cage or plate dislodgement, loosening at the screw-plate or screw-bone interfaces, postsurgical kyphosis, and pseudoarthrosis). Failures increased as the number of decompressed levels increased [10, 22, 23, 26, 29, 48, 62, 90, 91, 96, 100, 104, 105, 114, 115, 117, 121]. Some of the consequences can encounter vascular, esophageal or neurologic injury [51, 55, 98]. Obviously, fusion rates in the spine have been shown to have a direct correlation to the mechanical stability of the fusion construct [39]. In multilevel procedures the hybrid technique addresses this concern. As an alternative to multilevel corpectomies in patients with indication for decompression and fusion at three or more levels, discontinuous corpectomies plus adjacent-level discectomy with retention of an intervening body has been successfully performed without plate loosening or graft migration [22, 28, 46, 105, 106]. The hybrid technique increases the inherent mechanical construct stability [5, 105], facilitates reduction of kyphotic deformity [110], serves to maintain the reconstructed alignment, and minimizes the chance of terminal screw-bone interface degradation (Fig. 4) [46, 49, 105, 110]. With the hybrid or continuous ACDF techniques, the number of graft/bone interfaces which have to undergoe osseus union increases compared to long interbody grafts and cages. Nirala et al. [80] observed an increased rate of pseudoarthrosis with multilevel interbody grafts as opposed to a single long strut graft. However, instrumentation for stabilization during mature of the arthrodesis was not performed. Recently, in series of Asheknazi et al. [5] 12 patients underwent 3-level and 13 4-level ACDF using TMCs and ACPs, the latter affixed to the intermediate vertebrae. No instrumentation failure occurred, but fusion in 100%, and a lordotic posture (22°–30°) was achieved in 84%. In the beginning of our series, one of three hybrid constructs with 2-level corpectomies stabilized with NC-plate underwent early additional posterior stabilization because of poor osseus anchorage of the anterior instrumentation as shown intraoperatively. Nevertheless, if feasible the hybrid or ACDF technique is preferred and with none of our 19 4- and 5-level ACDF and two hybrid constructs posterior stabilization and fusion was indicated. However, in some cases multilevel corpectomies can not be avoided. Unfortunately, long strut grafts are known to be biomechanically inferior [105], and vulnerable to failure requiring revision [23, 40, 48, 92, 115]. Accordingly, a challenging problem that the orthopedic surgeon faces is the patient who has had a multilevel decompressive surgery that has failed (Fig. 7a). Because long fixed-moment arm constructs tend to load the caudal screw-bone interface far more than the rostral [98, 115], the failures are mostly observed at the caudal rather than cephalad ends of the construct (Fig. 7a) [4, 47, 48, 56, 98, 106] with the graft or cage telescoping and cavitating into the caudal vertebra as well as “kicking out” of the graft/cage or plate [2, 4, 23, 34, 49, 90, 91, 95, 121]. Accordingly, in a study of Wang et al. [121] seven of 71 (9.9%) 3-level grafts and one of six (16.7%) 4-level grafts showed graft migration, particularly if the fusion ended at the C7 vertebral body. Five patients (7%) had redo surgeries. The study depicted that a greater number of vertebral bodies removed and a longer graft are directly related to increased frequency of graft displacement. Also, in a study of Herrmann et al. [49] on instrumented 1- to 4-level ACDF, the bottommost level suffered a significantly greater loss of lordosis than the remaining levels, particularly in 3- and 4-level fusions that showed subsidience in 52% bottommost levels.

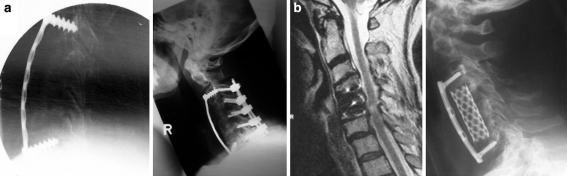

Fig. 7.

a Case 19. left Referred patient with non-instrumented 2-level corpectomy and adjacent discectomy, infection, tracheostoma and graft dislodgement. At index procedure he showed signs of advanced myelopathy. After implant removal, 3-level corpectomy C4-6 and NC-plate stabilization was performed (left). Insufficient construct stability following the index procedure with increase of the preexisting kyphosis C3-4 and marked subsidience of the graft caudally, telescoping at C6-7 with screw toogling at C7, as well as plate impingement on C7-T1 (seen on postop radiograph) demanded posterior fusion on the fourth postop day. Afterwards, the patient showed no further change of construct geometry, osseus union C3-7, good clinical outcome with moderate posterior neck pain at 6 months follow up. b Case 26, right 52-years old myelopathic referred patient with non-instrumented ACDF C4-6, DCI C3-4 and C6-7. Following implant removal the osseus defects demanded corpectomies C4-6 and ACPS using a CS-plate system. As there was good bone quality and sufficient construct rigidity intraoperatively, the patient was not considered to undergo additional posterior stabilization. Six months follow-up depicted satisfied patient, solid osseus incorporation at the cage-bone interface, as well as no loss of construct geometry

In general, the rigidity of the spine provided by an anterior cervical screw-plate system is a reflection of many factors including the design of the plate, the quality of the bone-screw and plate-screw interface, the major screw diameter and depth of insertion, and the bone mineral density [17, 21, 51]. Applying long and large-diameter screws can increase primary stability of cervical osteosynthesis, as it was the experience with our patients (Fig. 3). However, in terms of biomechanical rigidity use of uni- versus bi-cortical screws remains an issue of debate [69, 87]. Previous studies demonstrated a slightly enhanced stability with bi-cortical purchase [1, 35, 64, 93, 108]. But, following multilevel decompressions neither uni- nor bi-cortical screw fixation will determine the success of the construct survival, rather using a primary stable grafting technique, intermediate fixations points, whenever possible, and early scheduling posterior surgery if indicated. In our series, mainly longest uni-cortical screw purchase possible was applied, we did not observe any catastrophic graft/cage dislodgement, but plate-screw and screw-bone interface characteristics as discribed for NC-plates (Figs. 5, 7). Screw toggling is a phenomenon in which nonfixed-moment arm cantilever beam screw forces degrade the integrity of the bone and the screw-bone interface. The screw itself may sweep and abut the bone graft-enplate interface, thereby decreasing the surface area of contact and potentially diminishing the chance of solid fusion [37, 98]. Screw toggling accompanied with telescoping of the implants and graft/cage subsidience at the end-levels was observed in eight of our patients treated with NC-plates, whereas Spivak et al. [108] also observed a higher primary stability, particularly after cyclic loading, for CS-plates, and Lowery et al. [67] reported on significantly fewer failures for CS-plates than for NC-ones. Nowadays, with constrained ACPs (with/without dynamic features) the clinically observed failures usually do not occur by breakage or bending of the implants, but at the interface between bone and instrumentation [47, 48, 56, 98]. A reason of screw loosening even in CS-plate might be that the rigid long fixed-moment arm cantilever beam implanted may not adequately resists translational forces, resulting in degradation of the screw-bone interface and subsequent failure. The longer the implant, the more prone it is to these effects. The addition of intermediate points of fixation (Fig. 4), as with the hybrid technique or with posterior fixation results in greater resistance to translational and axial loads [28]. Concerning dynamic plate systems, aforescribed concerns and failure rates remain [13, 15, 19, 27, 30, 31, 78, 99]. As it was in our series, CS-plate systems tend to do better than NC-ones concerning the maintenance of reconstructed lordosis and construct rigidity [67]. Accordingly, we observed a significantly increased incidence of changes in construct geometry, loss of lordosis at fusion block, and loss of TCL C2-7 in those patients with NC-plates applied. Patients treated with CS-plates in our series had a significant shorter follow-up compared to patients treated with NC-plates (P = 0.01). But, significant changes in construct geometry mainly occur early in clinical course within 3 months after surgery [23, 28, 36, 49, 111, 126]. This was the case in eight of nine patients with NC-plates applied in our series. During the postoperative course we observed a mean change and mainly loss of lordosis at fusion block of 0.8° at all, only. However, it is to be emphasized that early additional posterior stabilization probably prevented construct failure in three patients, twice following 3-level corpectomies. From the point of view of testing or measuring techniques, combined 360° stabilization leaves no doubts, particularly in long corpectomy cases in which posterior stabilization alone was shown to be superior compared to anteriorly plated reconstructions [56, 58, 61, 104]. Anterior spinal implants are placed in a distraction mode and rely on the intrinsic properties of the posterior osseus and ligamentous structures to resist distraction and to obtain optimal security of fixation [98]. Hence, anterior plates under flexion loading in the setting of multicolumn instability can failure because they do not provide posterior column stability [24, 98], yet. Nevertheless, our study and literature review confirms that even in severe cervical stenosis the hybrid technique and multilevel ACDF serve for sufficient decompression, decrease the number of corpectomy levels, and thus the need for posterior support. But, if there are any doubts on stability and implant anchorage achieved intraoperatively, one should consider early additional posterior fixation. The latter deserves attention as concerns cases with PACS. Redo surgeries for failed anterior fusions showed an increased success rate with the use of posterior-only (94–98%) and circumferential fusion (94–100%) compared to anterior-only revision (55–57%) [16, 18, 66]. These reports suggest that posterior revision is indicated in failed PACS. However, as with our sample, anterior revisions are frequently performed for the purpose of removal of failed implants, resection of pseudoarthrosis, and correction of the anteriorly located deformity [110]. Notebly, prior studies did not address the correction of deformity following the posterior-only revisions [16, 18, 66]. In the current study, 40% of cases had PACS and in only two posterior stabiliziation was inidicated (Fig. 7a). Following anterior revision the remaining bone stock at the previous end-vertebrae is frequently observed to be insufficient to enable rigid fixation. Though, for the purpose of stabile anchorage of implants skipping or resection of at least one of the previous end-vertebrae was indicated in all of these cases. Extending fusion length to a sound end-vertebra acquires another intermediate point of fixation and strengthens the overall construct stability [110], which can avoid additional posterior fixation.

Influence of cervical lordosis

The sagittal plane neutral geometry of the cervical spine is an important biomechanical consideration [43]. A neutral sagittal vertical axis minimizes the muscular effort necessary to maintain an upright posture [3, 112]. In contrast, cervical kyphosis (CK) results in alteration of biomechanical forces acting on the neck and overload of the anterior parts of the spine [45]. CK may develop secondary to pseudoarthrosis, construct failure, and multilevel laminectomy or laminoplasty [82, 109, 110, 113]. An important cause for CK remains failed surgical restoration of lordosis [46,110]. With postsurgical CK, axial loads tend to cause further kyphosis via the application of a moment arm-induced bending. It initiates a vicious cycle of patholgical forces that can result in the development of a progressive deformity, in which chronic tensile forces may result in painful attenuation of the posterior ligaments and facet capsules, as well as muscle fatigue and imbalance. Progressive collapse with kyphosis of multilevel reconstructions can result in altered load distributions as well as in radiculopathy resulting from neural foraminal narrowing and myelopathy worsening from the cervical spinal cord beeing draped over the apex of the deformity [90, 95, 110, 113]. Progressive instability may cause severe pain and can retard neural recovery from the index decompression [90, 95, 110]. As it was the experience with our referred patients, the clinical result accompanying CK can be axial neck pain and neurologic compromise [3, 109, 110, 112, 113]. However, a “normal” or “pathological” cervical curvature has not been defined, yet. In a study of Grob et al. [41] mean TCL in asymptomatic and symptomatic individuals was 24.3° and 23.0°, respectively. In other surveys, normal TCL ranged between 10° and 34.5° [3, 38, 42, 43, 81]. As concerns postsurgical lordosis achieved, Sevki et al. [103] reported on successful reconstructions and no loss of sagittal alignment following the use of constrained ACPs, TMC, and posterior arthrodesis in twelve 3- to 4-level corpectomies. Mean sagittal Cobb angle was 9° before surgery, and 16.9° at last follow-up. Of note, the authors used precountered TMCs and a correction of 8° was achieved resembling a similar curve correction reported in other series including 2- and 3-level surgeries [6, 111]. With instrumented 3-level ACDF and hybrid reconstructions for the correction of postsurgical CK in 10 cases, Steinmetz et al. [110] achieved a mean correction of 20° with a mean lordosis of 8°. Majd et al. [70] reported on 34 patients, in which CS-plates were applied following 2-level corpectomies in 18 patients, 3-level in 5, and 4-level in 7. Average lordosis was 7.3° postoperatively using precountered TMC. Our study sample demonstrated a union rate of 100% and a favourable mean lordosis of 15.6°, representing a mean increase of 10.9° at last follow-up. In 88.5% of patients, good or excellent clinical results could be achieved. However, at last follow-up, we did not observe any statistically significant positive correlation between clinical outcome and TCL C2-7. As concerns the influence of lordosis on neurologic recovery, Ferch et al. [32] reported on 28 patients with progressive myelopathy and kyphotic deformity, which underwent instrumented ACDF. Improvement in myelopathy scores was significantly associated with a local postoperative lordotic angle of about 4°. Suda et al. [113] evaluated the outcome of 114 laminoplasties. Exceeding a local kyphosis of 13° without spinal cord signal intensity change on MRI, and 5° with signal intensity change on MRI were the most important risk factor combinations for poor outcomes. We did not find any significant correlation between neurologic recovery and postsurgical lordosis achieved. However, mean TCL at last follow-up was far high in our series (15.6°). Regarding Grob et al. [41] rather a sudden surgical alteration of a patient’s spinal curvature and introduction of changes in a previously balanced profile could be a cause of postsurgical pain, than not restoring anatomy towards “normal” lordosis. This observation might play a crucial role, in which restoration of a lordotic curvature is favourable, balances the sagittal profile, and prevents further kyphosis with possible implant loosening and neurologic deterioration. With respect to our series with only two poor clinical outcomes and a significant reduction of myelopathia scores postoperatively, we also consider the reconstruction of cervical lordosis, at least beyond 0°, a decisive factor for a good clinical outcome [12, 110, 111].

As in our cases, hybrid and ACDF techniques ease the reconstruction of cervical lordosis: segmental distraction and lordotic restoration is obtained at its best using wedged interbody grafts/cages in conjunction with ACPS [3, 7, 110]. It serves in foraminal and central decompression as the cord slightly shifts posteriorly, away of the mainly anteriorly situated stenosis [7, 112, 113]. Oppositively, cervical lordosis is difficult to be reconstructed effectively using large cages or grafts in case of multilevel corpectomies, because of the rectangular shape of most current devices or the design of the grafts [6, 48, 70]. Mean correction in patients with 2- and 3-level corpectomies was 6.8° in our series, resembling a similar value compared to other series [48, 52, 103], and mainly representing the lordotic shape of currently used ACPs (Fig. 7b). In contrast, our mean correction in multilevel ACDF and hybrid fusions (with a 1-level corpectomy) was 12.0°. The usage of prebend lordotic TMCs seems promising. But, if their use will increase the average amount of cervical lordosis reconstructed following a multilevel corpectomy is to be further investigated.

Adjacent disc degeneration

Although primary and secondary migration with impingement of ACPs on adjacent disc spaces is less documented, it can be seen over time in clinical practice and literature [25, 27, 76, 109, 114]. We observed it secondarily due to telescoping at the end of a long instrumentation in four of our patients, and primarily in three patients (Fig. 4). Plate impingement can cause ADD, levering of adjacent-level motions on the abutting implant, and thus promote implant loosening, and, as a consequence, changes in construct geometry. Although secondary plate impingement was symptomatic only once in our series, its incidence should be prevented by enhanced constructed rigidity. Obviously, primary plate impingement should be avoided, which is difficult by times at the radiographical worse visible CTJ.

Overall, symptomatic ADD following ACDF was reviewed as high as 15% [50], whereas in 20% of our patients any kind of adjacent-level pathology was observed. Ikenega [52] observed progression of ADD in 12% of his multilevel surgeries, but he also did not observe any significant differences regarding outcome. Excluding mentioned pitfalls, symptomatic ADD also in multilevel cases seems to reflect the normal course of some adjacent levels not included in the fusion construct at index procedure, but rather should so. Whether the incidence or the severity of ADD following multilevel reconstructions is related to any distinct amount of sagittal curve correction achieved, remains unsolved, but requires larger samples sizes.

Early in our study period we had one surgical failure after posterior wiring for ADD with kyphosis C7-T1. Patient finally underwent successful 360° fusion. If there is sufficient TCL and lordosis at fusion block with an anteriorly located stenosis accomponying the ADD, the authors currently recommend implant removal and ACDF at the involved segment. In case of ADD particularly at the CTJ, 360° stabilization should be considered to prevent construct failure due to the long lever-arm resulting from the preexisting cephalad fusion block [60, 62, 74].

Clinical failures in multilevel anterior cervical constructs

In the literature, the clinical results of multilevel cervical anterior fusion constructs vary, and only a few studies focus on the clinical and geometrical outcome of 2- and 3-level or 4- and 5-level fusions. Unfortunately, details on the number of instrumented vertebra, distribution of decompressed levels, and additional usage of the Halo are often lacking. Anecdotally, construct failures in multilevel corpectomies with stand-alone strut grafts have been reported and reviewed as high as 10–50% [33, 68, 89, 94, 96, 107], whereas stand-alone grafts do not support or halter the reconstructed cervical lordosis in multisegmental constructs [91]. Recently, Ikenaga et al. [52] reported a 85% fusion rate after 12 months in 112 multilevel corpectomies using long fibular grafts afixed with one screw caudally. However, a Halo vest was applied for six weeks with a semirigid collar for additional four weeks, and the time of recumbency was not given. Anterior instrumentations showed that the Halo can be despansible these days, but displaying their own biomechanical limits as part of anterior-only constructs: Steinmetz et al. [111] reported on the results of 13 2-level and six 3-level ACDF, as well as four 1-level, nine 2-level, and two 3-level corpectomies using dynamic CS-plates. 2- and 3-level corpectomies showed union in 89 and 50%, respectively. Twice anterior revision had to be performed. With 3-level ACDF union rate was 83%, which was similar to a series of Arnold et al. [4] on 18 4-level ACDF with CS-plate fixation. In a series of Bolesta et al. [12], seven (47%) of 15 patients with ACDF and CS-plate stabilization at 3 or 4 levels achieved solid arthrodesis. One third required a second surgery due to nonunion, implant failure, and ADD. Posterior fusion was successful in redo surgeries and was recommended for multilevel fusions. Barnes et al. [6] reported on 20 patients with 2- or multilevel ACDF, and six with multilevel corpectomies. ACPS with posterior stabilization in eight corpectomy cases resulted in a successful union rate of 93.5%. Swank et al. [114] reported on a nonunion rate of 44 and 54% for 3-level fusions using CS- and NC-plates, respectively. Instrumentation failure occured in 25–52% using three different plate systems. Overall, 29 patients (45%) had second procedures. Vaccaro et al. [117] reported results of a multicenter study with early failure rates of 9% for 2-level and 50% for 3-level corpectomies reconstructed with CS-plates in 33 and 12 patients, respectively. Six of twelve patients (50%) in the plated 3-level corpectomy group had graft/plate dislodgement. Daubs [23] reported on 23 corpectomies reconstructed with TMC and stabilized with CS-plates. There was one failure (6%) in the 1-level corpectomy group, four (67%) in the 2-level group, and three in the 3-level group (100%), once despite postoperative Halo immobilization. Revision surgery was indicated in 26%, six underwent circumferential fusion. Sasso et al. [95] reported a 6% failure rate in their patients who received CS-plates for 2-level corpectomy and fusion, but a 71% failure rate following 3-level corpectomies. All five failures were catastrophic graft/plate displacements and three underwent revision surgery. They had no failure of 3-level corpectomy reconstructions when posterior lateral mass screw stabilization was added. Hee et al [48] reported on 21 patients undergoing multilevel corpectomies and reconstruction with TMC and ACPS. Within a complication rate of 33%, the major complication was largely the result of failures of subsidience and bone-implant interface failures, especially in patients with osteopenic bone. The redo rate was 14%, and there was a trend towards a higher complication rate in patients who had more than 2-level corpectomies (60%) compared with those who had two-level corpectomies (25%). Finally, in a series of Lowery et al. [67] with surgeries including one disc level in 27 patients, 2 in 38, 3 in 27, 4 in 16, and 5 in 1 patient, second surgeries were indicated in albeit 37%, whereas 4- and 5-level ACDF with NC-plates showed a failure rate of 71 and 80%, respectively.

Biomechanical studies [24, 53, 54, 61, 75, 86, 95, 99, 100, 102, 104] and previous clinical studies [11, 22, 48, 55, 61, 62, 66, 73, 75, 90, 95, 100–102, 104, 118] called into question the use of anterior devices in multilevel fusions and corpectomy cases, and support the addition of posterior stabilization, particularly that of pedicle screw fixation [58, 59, 61, 97, 100]. However, one has to consider that with the biomechanical advantage of supplemental posterior stabilization is the addition of a second significant surgery and added risks, particularly in elderly and frail patients. There is the potential for a higher rate of infection, surgical morbidity and increased inhospital stay. Posterior dissection can cause significant myofascial pain due to the stripping of the musculature from the posterior elements and axial neck pain [5, 18, 52, 85, 89, 103, 110, 119]. Two of our three cases sustaining posterior fusion depicted severe and moderate posterior neck pain, respectively. Similar outcomes are explored during clinical work. Nevertheless, added stabilization with circumferential instrumentation of plated multilevel discectomies and corpectomies can improve the early and long-term construct stability. Example, in a series of McAfee et al. [73] with 15 patients, no patient had evidence of instrumentation failure using circumferential stabilization. Vanichkachorn et al. [118] reported on 11 patients with an average of 3.4 corpectomized levels, strut grafting and junctional plating. All patients had additional posterior fixation, no patient experienced construct failure. Schultz et al. [101] reported on successful 3-level corpectomies in 30 cases and 4-level in two following anterior decompression, fibula strut graft placement, ACPS, and posterior fixation. In a series of Rogers et al. [92], including 3-level corpectomies in ten patients and four in one, there were no failures but a 100% fusion rate following anterior strut grafting and posterior fixation, too.

In summary, the rate of nonunions in multilevel ACDF and the failure rates for long-length anterior cervical decompressions/corpectomies with multilevel fusion has been observed as high as 20–50% [4, 12, 26, 52, 114, 124], and up to 30–100% [8, 12, 19, 23, 48, 56, 67, 88, 95, 100, 111, 114, 117, 118, 124], respectively. Thirty–fifty percent of complications in multilevel cases are due to graft- and instrumentation related causes and carry a significant reoperation rate, which is reported between 10 and 100% [12, 19, 23, 40, 48, 67, 91, 95, 96, 98, 111, 114, 115, 121, 124]. The operative treatment of failed multilevel surgeries remain challenging salvage procedures with considerable risks and complications. The ideal goal is to prevent these complications in the first place [90, 95]. However, an open question remains: How much stability is indicated for a solid fusion in each instability pattern, and does this instability pattern imply the necessity of a combined anterior and posterior fixation [100]. Our study confirms experiences documented in literature that preferring hybrid techniques or multilevel ACDF can decrease the need for additional posterior fusion. If a solid snug-fit intersegmental fusion using structural grafts and/or cages, as well as proper surgical stabilization with CS-plates is performed, there will be a high rate of osseus union and long-term construct stability. If sufficient osseus anchorage even in 3- and more-level corpectomies can be achieved, than combined 360° stabilization is not necessarily demanded (Fig. 7b). But, our review of literature as well as our own results suggests that, if one wants to avoid immobilzation with the Halo, some anterior-only constructs including more than 2-level corpectomies [23, 48, 95, 111, 117] can show meaningful concerns regarding failure rates. Though, it seems appropriate to evaluate the achieved construct stability intraoperatively, and early consider additional posterior fixation in cases with more than 2-level corpectomies (Fig. 7a). In surgical situations, which encounter insufficient construct rigidity following ACPS with worse purchase of the implants particularly in weak osteoporotic bone, the construct rigidity can be assessed intraoperatively using passive flexion/extension testing. Further, from results reported in literature distinct indications for the combined approach include the evidence of severe osteoporosis or neoplastic subaxial disease with both anterior and posterior element involvement, salvage of failed multilevel anterior instrumentations, correction of rigid (Fig. 2) or postlaminectomy kyphosis, severe trauma cases with resultant three-column injury, and fractures in combination with ankylozing spondylitis, as otherwise a higher incidence of pseudoarthrosis and fixation failure can occur [2, 3, 10–12, 14, 22–24, 55, 60–62, 65, 71, 79, 92, 106, 109, 116, 120, 125].

Clinical outcome and surgical complications

The surgical complications in our series encountering only 4- and 5-level anterior fusions are comparable, and even less than compared to similar studies [6, 25, 77, 101, 110, 111, 126]. According to Lee et al., 50% of patients will suffer short-term dysphagia and about 10% have long-term sequelae following ACDFs [63]. Postoperatively, we observed temporary dysphagia in 17.6%, and transient hoarseness in 11.8%. In anterior redo surgeries, Beutler et al. [9] reported the incidence of RLN symptoms to be highest with 9.5%. In sight of albeit 40% of our patients sustaining anterior redo surgeries, our incidences observed are neglectable. We did not observe any dural, neural, esophageal or vertebral artery injury [28], or any anterior infection. 88.5% of our patients showed good or excellent outcome following 27.4 months in average. Our follow-up and sample size was comparable to previous studies (21.5 and 18.5, respectively [12, 25, 28, 48, 49, 52, 91, 101]). If clinical outcome was addressed in previous studies, it was satisfactory in more than 60–80% [28, 49, 52, 70]. If there is a decreased clinical outcome, the reasons can have their source in late construct failure, ADD, symptomatic implants, pseudoarthrosis, and severe rekyphosis. Also, one has to consider that multilevel posterior cervical approaches can be a significant source for pain [52]. Accordingly, in a study of Barnes et al. [6], a significantly lower rate of satisfactory outcomes was shown in those patients who underwent combined anterior–posterior multilevel procedures. As it was in our study, loss of cervical motion is not a meaningful concern [52, 110], and the evidence of PACS had no adverse effect on clinical outcome. The majority of our patients showed a lordotic cervical posture at follow-up. Though, reconstruction of cervical lordosis is favourable [12, 111]; however, a certain amount of lordosis that is to be reconstructed and cut-offs below which clinical outcome decreases were not found but demands further investigation.

Conclusion

Good to excellent clinical outcomes can be achieved in multilevel ACDF, if thorough decompression, distraction and grafting, reconstruction of a lordotic cervical posture, and ACPS is peformed. Within ACPS, constrained plates show increased construct rigidity compared to non-constrained ones. If there is a need for 360° stabilization and fusion, i.e., following more than 2-level corpectomies, it should be scheduled early. Drawing conclusions from the potential hazards in stabilizing multilevel corpectomies of the cervical spine with use of current anterior non-locking and even locking plate systems, stronger anterior fixation devices are demanded, eliminating the need for posterior supplemental fusion in some highly unstable multilevel decompressions.

Abbreviations

- ACPs

Anterior cervical plates

- ACPS

Anterior cervical plate stabilization

- ACDF

Anterior cervical (segmental) decompression/discectomy and fusion

- ADD

Adjacent disc disease

- CS- and NC-plate

Constrained and non-constrained screw-plate system

- CTJ

Cervicothoracic junction

- DCI

Degenerative cervical instability

- LM-P

Lateral mass plating

- LM-CSR

Lateral mass constrained screw-rod system

- PACS

Previous anterior cervical spine surgery

- RLN

Recurrent laryngeal nerve

- TMC

Titanium mesh cage(s)

- TCL

Total cervical lordosis C2-7

Contributor Information

Heiko Koller, Phone: +49-7151-65795, FAX: +49-7151-996824, Email: heiko.koller@t-online.de.

Axel Hempfing, Email: hempfing@yahoo.de.

References

- 1.AChen IH (1996) Biomechanical evaluation of subcorticl versus bicortical screw purchase in anterior cervical plating. Acta Neurchir 138:167–173 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Abdulhak M, Marzouk S (2005) Challenging cases in spine surgery. Thime Med Publ, Inc, New York, pp 10–13

- 3.Anderson DG, Silber JS, Albert TJ (2005) Management of cervical kyphosis caused by surgery, degenerative disease, or trauma. In: Clark CR (ed) The cervical spine. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia, pp 1135–1145

- 4.Arnold PM, Eckard DA (1999) Four-level anterior cervical discectomy and fusion report of 18 cases with one-year follow-up. Annual meeting CSRS-A, Podium Presentation #5

- 5.Ashkenazi E, Smorgick Y, Rand N, Millgram MA, Mirovsky Y, Floman Y (2005) Anterior decompression combined with corpectomies and discectomies in the management of multilevel cervical myelopathy: a hybrid decompression and fixation technique. J Neurosurg Spine 3:205–209 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Barnes B, Haid RW, Rodts G, Subach B, Kaiser M (2002) Early results using atlantis anterior cervical plate system. Neurosurg Focus 12(1):Article 13 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Bayley JC, Yoo JU, Kruger DM, Schlegel J (1995) The role of distraction in improving the space available for the cord in cervical spondylosis. Spine 20:771–775 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Bernard TN Jr, Whitecloud TS III (1987) Cervical spondylotic myelopathy and myeloradiculopathy: anterior decompression and stabilization with autogenous fibula strut graft. Clin Orthop Rel Res 221:149–160 [PubMed]

- 9.Beutler WJ, Sweeney CA, Conolly PJ (2001) Recurrent laryngeal nerve injury with anterior cervical spine surgery risk with laterality of surgical approach. Spine 26:1337–1342 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Bilsky MH, Boakye M, Collignon F, Kraus D, Boland P (2005) Operative management of metastatic and malignant primary subaxial cervical tumors. J Neurosurg Spine 2:256–264 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Blauth M, Schmidt U, Bastian C, Knop C, Tscherne H (1998) Die ventrale interkorporelle Spondylodese bei Verletzungen der Halswirbelsäule. Indikationen, Operationstechnik und Ergebnisse. Zentralbl Chir 123:919–929 [PubMed]

- 12.Bolesta MJ, Rechtine DR II, Chrin AM (2000) Three- and four-level anterior cervical discectomy and fusion with plate fixation: a prospective study. Spine 25:2040–2056 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Bose B (2003) Anterior cervical arthrodesis using DOC dynamic stabilization implant for improvement in sagittal angulation and controlled settling. J Neurosurg 98(1 Suppl):8–13 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.Bozkus H, Ames CP, Chamberlain RH, Nottmeier EW, Sonntag VKH, Papadopoulos SM, Crawford NR (2005) Biomechanical analysis of rigid stabilization techniques for three-column injury in the lower cervical spine. Spine 30:915–922 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Brodke DS, Gollogly S, Alexander MR, Nguyen BK, Dailey AT, Bachus AK (2001) Dynamic cervical plates: biomechanical evaluation of load sharing and stiffness. Spine 26:1324–1329 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Brodsky AE, Khalil MA, Sassard WR, Newman BP (1992) Repair of symptomatic pseudoarthrosis of anterior cervical fusion: posterior versus anterior repair. Spine 17:1137–1143 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Bryan C, Cordista AG, Horodyski M, Rechtine GR (2005) Biomechanical evaluation of the pullout strength of cervical screws. J Spinal Disord 18:506–510 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.Carreon L, Glassman SD, Campbell MJ (2006) Treatment of anterior cervical pseudoarthrosis: posterior fusion versus anterior revision. Sine J 6:154–156 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.Casha S, Fehlings MG (2003) Clinical and radiological evaluation of the Codman semiconstrained load-sharing anterior cervical plate: prospective multicenter trial and independent blinded evaluation of outcome. J Neurosurg 99(3 Suppl):264–270 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 20.Coe JD, Vaccaro AR (2004) Complications of anterior cervical plating. In: Clark CR (eds) The cervical spine, 4th edn. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia, pp 1147–1169

- 21.Conrad B, Cordista A, Horodyski MB, Rechtine G (2005) Biomechanical evaluation of the pullout strenght of cervical screws. J Spinal Disord Tech 18:506–510 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 22.Curylo L, An HS (2005) Spinal instrumentation on degenerative disorders of the cervical spine, 2nd edn. Lippincott Williams&Wilkins, Philadelphia

- 23.Daubs MD (2005) Early failures following cervical corpectomy reconstrcution with titanium mesh cages and anterior plating. Spine 30:1402–1406 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 24.Do Koh Y, Lim TH, Won You J, Eck J, An HS (2001) A biomechanical comparison of modern anterior and posterior plate fixation of the cervical spine. Spine 26:15–21 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 25.Dorai Z, Morgan H, Cimbra C (2003) Titanium cage reconstruction after cervical corpectomy. J Neurosurg 99(1 Suppl):3–7 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 26.DR Gore (2001) The arthrodesis rate in multilevel anterior cervical fusions using autogenous fibula. Spine 26:1259–1263 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 27.DuBois CM, Bolt PM, Todd AG, Gupta P, Wtzel FT, Phillips FM (2007) Static versus dynamic plating for multileve lanterior cervical discectomy and fusion. Spine J 7:188–193 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 28.Eleraky MA, Llanos C, Sonntag VKH (1999) Cervical corpectomy: report of 185 cases and review of literature. J Neurosurg 90(1 Suppl):35–41 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 29.Elsaghir H, Bohm H (2000) Anterior versus posterior cervical plating in cervical corpectomy. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 120:549–554 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 30.Epstein NE (2003) Anterior cervical dynamic ABC plating with single level corpectomy and fusion in forty-two patients. Spinal Cord 41:153–158 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 31.Epstein NE (2002) Reoperation rates for acute graft extrusion and pseudarthrosis after one-level anterior corpectomy and fusion with and without plate instrumentation: etiology and corrective management. Surg Neurol 56:73–80 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 32.Ferch RD, Shad Amjad, Cadoux-Hudson TAD, Teddy PJ (2004) Anterior correction of cervical kyphotic deformity: effects on myelopathy, neck pain, and sagittal alignment. J Neurosurg 100(1 Suppl Spine):13–19 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 33.Foley KT, Di Angelo DJ, Rampersaud YR, Vossel KA, Jansen TH (1999) The in vitro effects of instrumentation on multilevel cervical strut-graft mechanics. Spine 24:2366–2376 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 34.Foley KT, Smith MM, Wiles DA (1997) Anterior cervical plating does not prevent strut graft displacement in multilevel cervical corpectomy. In: Annual meeting of the CSRS-A. Rancho Mirage, California, Paper presentation

- 35.Gallagher MR, Maiman DJ, Reinartz J Pintar F, Yoganandan N (1993) Biomechanical evaluation of Caspar cervical screws: Comparative study under cyclic loading. Neurosurgery 33:1045–1050; Comments 1050–1051 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 36.Geisler FH, Caspar W, Pitzen T et al (1998) Reoperation in patients after anterior cervical plate stabilization in degenerative disease. Spine 23:911–920 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 37.Gonugunta V, Krishnaney AA, Benzel EC (2005) Anterior cervical plating. Neurol India 53:424–432 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 38.Gore DR, Sepic SB, Gardner GM (1986) Roentgenographic findings of the cervical spine in asymptomatic people. Spine 11:521–524 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 39.Greene DL, Crawford NR, Chamberlain RH, Park SC, Crandall D (2003) Biomechanical comparison of cervical interbody cage versus structural bone graft. Spine J 3:262–269 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 40.Greiner-Perth R, Allam Y, El-shagir H, Frank J, Boehm H (2006) Analysis of reoperations after surgical treatment of degenerative cervical spine disorders. A report on 900 cases. Eur Spine J 15(Suppl 4):S459 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 41.Grob D, Frauenfelder H, Mannion AF (2006) The association between cervical spine curvature and neck pain. Eur Spine J, E-pub Octob 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 42.Hardacker JW, Shuford RF, Capicotto PN, Pryor PW (1997) Radiographic stanting cervical segmental alignement in adult volunteers without neck symptoms. Spine 22:1472–1480 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 43.Harrison DD, Harrison DE, Janik TJ, Cailliet R, Ferrantelli JR, Haas JW, Holland B (2004) Modeling of the sagittal cervical spine as a method to discriminate hypolordosis. Spine 29:2485–2492 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 44.Harrison DD, Janik TJ, Troyanovich SJ, Holland B (1996) Comparisons of Lordotic cervical spine curvatures to a theoretical model of the static sagittal cervical spine. Spine 21:667–675 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 45.Harrison DE Harrison DD, Janik Tj, Jones WE, Calliet R, Normand M (2001) Comparison of axial and flexural stresses in lordosis and three buckled configurations of the cervical spine. Clin Biomech 16:276–284 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 46.Harrop JS, Steinmetz MP, Benzel EC (2005) Deformity surgery: subaxial cervical spine. In: Benzel EC (ed) Spine surgery. Elsevier, Philadelphia, pp 876–891

- 47.Hart R, Gillard J, Prem S, Shea M, Kitchel S (2005) Comparison of stiffness and failure load of two cervical spine fixation techniques in an in vitro human model. J Spinal Disord Tech 18:S115–118 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 48.Hee HT, Majd ME, Holt RT, Whitecloud TS III, Pemkowski D (2003) Complications of multilevel cervical corporectomies and reconstruction with titanium cages and anterior plating. J Spinal Disord Tech 16:1–9 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 49.Herrmann AM, Geisler FH (2004) Geometric results of anterior cervical plate stabilization in degenerative disease. Spine 29:1226–1234 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 50.Hilibrand AS, Robbins M (2004) Adjacent segment degeneration and adjacent segment disease: the consequences of spinal fusion. Spine J 4:190S–194S [DOI] [PubMed]

- 51.Hitchon PW, Brenton MD, Coppes JK, From AM, Torner JC (2003) Factors affecting pullout strength of self-drilling and self-tapping anterior cervical screws. Spine 28:9–13 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 52.Ikenaga M, ShikataJ, Tanaka C (2005) Anterior corpectomy and fusion with fibular strut grafts for multilevel cervical myelopathy. J Neurosurg Spine 3:79–85 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 53.Isomi T, Panjabi MM, Wang JL, Vaccaro AR, Garfin SR, Patel T (1999) Stabilizing potential of anterior cervical plates in multilevel corpectomies. Spine 24:2219–2223 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 54.Isomi T Panjabi MM, Wang JL et al (1999) Stabilizing potential of anterior cervical plates in multilevel corporectomies. Spine 24:2219–2223 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 55.Jeffrey D, Vaccaro C, Vaccaro AR (2004) Complications of anterior cervical plating. In: Clark CR (eds) The cervical spine. 4th edn. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia, pp 1147–1169

- 56.Jones EL, Heller JG, Silcox DH, Hutton WC (1997) Cervical pedicle screws versus lateral mass screws: anatomic feasibility and biomechanical comparison. Spine 22:977–982 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 57.Katsuura A, Hukuda S, Imanaka T, Miyamoto K, Kanemoto M (1996) Anterior cervical plate used in degenerative disease can maintain cervical lordosis. J Spinal Disord 9:470–476 [PubMed]

- 58.Kotani Y, Cunningham BW, Abumi K, McAfee PC (1994) Biomechanical analysis of cervical stabilization systems. An assessment of transpedicular screw fixation in the cervical spine. Spine 19:2529–2539 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 59.Kothe R, Rüter W, Schneider E, Linke B (2004) Biomechanical analysis of transpedicular screw fixation in the subaxial cervical spine. Spine 29:1869–1875 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 60.Kreshak JL, Kim DH, Lindsey DP, Kam AC, Panjabi MM, Yerby SA (2002) Posterior stabilization at the cervicothoracic junc-tion: a biomechanical study. Spine 27:2763–2770 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 61.Krikpatrick JS, Levy JA, Carillo J, Moeini SR (1999) Reconstruction after multilevel corporectomy in the cervical spine. A sagittal plane biomechanical study. Spine 24:1186–1191, Discussion 1191 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 62.Le H, Balabhadra R, Park J, Kim D (2003). Surgical treatment of tumors involving the cervicothoracic junction. Neurosurg Focus 15(5):Article 3 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 63.Lee JY, Lim MR, Albert TJ (2005) Dysphagia after anterior cervical spine surgery: pathophysiology, incidence, and prevention. www.csrs.org

- 64.Lehmann W, Briem D, Blauth M, Schmidt U (2005) Biomechanical comparison of anterior cervical spine locked and unlocked plate-fixation systems. Eur Spine J 14:243–249 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 65.Liu JK, Apfelbaum RI, Chiles III BW, Schmidt MH (2003) Cervical spinal metastasis: anterior reconstruction and stabilization techniques after tumor resection. Neurosurg Focus 15(5):Article 2 [PubMed]

- 66.Lower GL, Swank ML, McDonough RF (1995) Surgical revision for failed anterior cervical fusions. Articular pillar plating or anterior revision? Spine 20:2436–2441 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 67.Lowery GL, McDonough RF (1998) The significance of hardware failure in anterior cervical plate fixation. Patients with 2- to 7-year follow-up. Spine 23:181–186 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 68.MacDonald RL, Fehlings MG, Tator CH, Lozano A, Fleming JR, Gentili F, Bernstein M, Wallace MC, Tasker RR (1997) Multilevel anterior cervical corpectomy and fibular allograft fusion for cervical myelopathy. J Neurosurg 86:990–997 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 69.Maiman DJ, Pintar FA, Yoganandan N, Reinartz J, Toselli R, Woodward E, Haid R (1992) Pull-out strenght of Caspar cervical screw. Neurosurg 31:1097–1101 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 70.Majd ME, Vadhva M, Holt RT (1999) Anterior reconstruction using titanium cages with anterior plating. Spine 24:1604–1610 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 71.Mayr MT, Subach BR, Comey CH, Rodts GE, Haid RW Jr (2002) Cervical spinal stenosis: outcome after anterior corpectomy, allograft reconstruction, and instrumentation. J Neurosurg (Spine 1) 96:10–16 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 72.Mc Aviney J, Schulz D, Bock R, Harrison DE, Holland B (2005) Determining the relationship between cervical lordosis and neck complaints. J Manupulative Physiol Ther 28:187–193 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 73.McAfee PC Bohlmann HH, Ducker TB et al (1995) One stage anterior cervical decompression and posterior stabilization. J Bone Joint Surg 77-A:1791–1800 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 74.Metz-Stavenhagen P, Krebs S, Meier O (2001) Cervical fractures in ankylosing spondylitis. Orthopaede 30:925–931 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 75.Mummaneni PV, Haid RW, Traynelis VC, Sasso RC, Subach BR, Fiore AJ, Rodts GE (2002) Posterior cervical fixation using a new polyaxial screw and rod system: technique and surgical results. Neurosurg Focus 12:1/Article 8 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 76.Naideri S, Baldwin NG (2005) Ventral cervical decompression and fusion: To plate. In: Benzel EC (ed) Spinal surgery. Elsevier, Philadelphia, pp 2061–2064

- 77.Nakase H, Park Y-S, Kimura H, Sakaki T, Morimoto T (2006) Complications and long-term follow-up results in titanium mesh cage reconstruction after cervical corpectomy. J Spinal Disord Tech 19:353–357 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 78.Epstein NE (2003) Anterior cervical dynamic ABC plating with single level corprorectomy and fusion in forty-two patients. Spinal Cord 41:153–158 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 79.Nieto JH, Benzel EC (2005) Combined ventral-dorsal procedure. In: Benzel EC (eds). Spine surgery. 2nd edn. Elsevier, Philadelphia, pp 402–405

- 80.Nirala AP, Husain M, Vatsal DK (2004) A retrospective study of multiple interbody grafting and long segment strut grafting following anterior cervical decompression. Br J Neurosurg 18:227–232 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 81.Nojiri K, Matsumoto M, Chiba K, Maruiwa H, Nakamura M, Nishizawa T, Toyama Y (2003) Relationship between alignement of upper and lower cervical spine in asymptomatic individuals. J Neurosurg (Spine 1) 99:80–81 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 82.Nolan JP, Sherk HH (1988) Biomechanical evaluation of the extensor musculatur of the cervicle spine. Spine 13:9 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 83.Nurick S (1972) The pathogenesis of the spinal cord disorder associated with cervical spondylosis. Brain 95:87–100 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 84.Odom Gl, Finney W, Woodhall B (1958) Cervical disk lesions. JAMA 166:23–28 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 85.Ohnari H, Sasai K, Akagi S, Iida H, Takanori S, Kato I (2006) Investigation of axial symptoms after cervical laminoplasty, using questionnaire survay. Spine J 6:221–227 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 86.Panjabi MM, Isomi T, Wang JL (1999) Loosening at the screw-vertebra junction in multilevel anterior cervical plate constructs. Spine 24:2383–2388 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 87.Pitzen T, Barbier D, Tintinger F, Steudel WI, Strowitzki M (2002) Screw fixation to the posterior cortical shell does not influence peak torque and pullout in anterior cervical plating. Eur Spine J 11:494–499 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]