Abstract

A 1000-member uridinyl branched peptide library was synthesized on PS-DES support using IRORI technology. High-throughput screening of this library for anti-tuberculosis activity identified several members with a MIC90 value of 12.5 μg/mL.

Keywords: Mureidomycins, Uridine-based library, Solid-phase synthesis, IRORI technology, Anti-tuberculosis activity

Due to the emergence and spread of multi-drug resistant microbes such as multidrug-resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, and penicillin-resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae, there is an urgent need to develop new antibiotics to treat these problematic pathogens.1 Mureidomycins (Figure 1) were first isolated from the culture filtrate of Streptomyces flavidovirens in 1989,2 and these nucleoside peptidyl antibiotics have notable activity in vitro against a variety of drug resistant pathogens with an acceptable selectivity index. Mureidomycin C (R = Gly) is the most active member within this chemical class with minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) values of 0.1-3.13 μg/mL against various strains of P. aeruginosa.3 Mechanistic studies have revealed that Mureidomycins are inhibitors of the MraY enzyme, a transmembrane translocase, which performs an essential role in bacterial peptidoglycan biosynthesis and is currently not targeted by any approved antibacterial treatments.4 In the literature, a number of studies have reported the synthesis and evaluation of Mureidomycin and Pacidamycin analogues that have garnered an understanding of the structure activity relationship of this class suggesting that some chemical modifications to these molecules are possible.5 The major problem of this class of inhibitors is their large molecular weight and consequent poor bioavailability. Mureidomycins thus represent an attractive natural product scaffold for the development of novel antibiotics agents, especially if more bioavailable analogues could be developed.

Figure 1.

Mureidomycins A, C, and uridinyl branched peptide urea library 1.

The synthesis of chemical libraries derived around natural product templates is an attractive approach to discovery of pharmacologically active compounds. In this study we report the generation and evaluation of a simplified uridinyl branched peptide urea library with structural similarity to the Mureidomycin class of antibiotics. We recently reported the solid-phase synthesis of a thymidinyl/2′-deoxyuridinyl Ugi library6 and a thymidinyl dipeptide urea library7 for use as discovery libraries and probes for sugar nucleotide utilizing enzymes. Biological screening of these libraries identified a few active compounds against M. tuberculosis (MIC90 = 50 μg/mL). This study focused on the solid-phase synthesis and biological evaluation of an advanced, more complex uridinyl branched peptide urea library 1 (Figure 1). Compared with the previous libraries, two important structural features were incorporated into this library. First, the nucleoside scaffold is uridine derived rather than thymidine or 2′-deoxyuridine. Since uridine templates are more commonly present in naturally occurring nucleoside antibiotics including tunicamycins, liposidomycins, and capuramycins etc.,8 a uridine scaffold may have a better chance of being recognized by the target enzyme. Second, a branched functionality was introduced to explore greater structural diversity and to increase the potential for a broader range of interactions with the target enzyme.

From a synthetic viewpoint, these modifications posed new challenges for the synthesis of this library 1. First, in contrast to the chemical structures of thymidine or 2′-deoxyuridine, the starting nucleoside contains an extra 2′-hydroxy group. This hydroxyl could lead to over-acylation byproducts and decreased loading capacity of the resin due to bis-addition to the solid support. Therefore, a parallel experiment was designed and carried out to evaluate if 2′-OH causes over-acylation and compare the loading capacity of uridine, 2′-deoxythymidine, and 2′-deoxyuridine. The loading capacity, determined by following an established protocol,7 was found to be 52% for the uridine, slightly lower than that obtained for thymidine and 2′-deoxyuridine. The decreased loading is attributable to increased steric hinderance and some bis-loading of the diol. Evidence for over-acylation of the free hydroxyl group was not seen under the standard peptide and urea formation condition used in the library synthesis.

The next major synthetic challenge involved the introduction of the branched functionality. Two potential strategies could be applied based on availability of starting materials and compatibility with the silyl ether resin linker. The first approach evaluated used an orthogonally protected diaminoacid derivative, ivDde protected 1,3-diaminopropionic acid (Fmoc-Dpr(ivDde)-OH9, 2 in Figure 2). The ivDde protecting group is stable to Fmoc removal conditions of 20% piperidine and can be selectively removed by 2% hydrazine in DMF allowing for selective cleavage of either protecting group. The second approach evaluated used a modified Fmoc protected azido deoxyserine residue (Fmoc-Ser(N3)-OH, 3 in Figure 2). In this case the azido group is used to mask the second amino functionality. Orthogonal azide reduction or Fmoc removal conditions could then be used to selectively afford each primary amine. In test reactions both methods yielded good results after final cleavage based upon model compound synthesis. Fmoc-Ser(N3)-OH was ultimately chosen for library synthesis based on cost. Key starting material 3 (~100 g) was prepared in a large scale in 3-step sequence from Fmoc-Ser-OH using the protocol of Schmidt10 with a minor modification: PPh3/CBr4/NaN3 was used to replace PPh3/DEAD/HN3 for the azide introduction step for safety purposes.

Figure 2.

Building blocks evaluated for branched functionality incorporation.

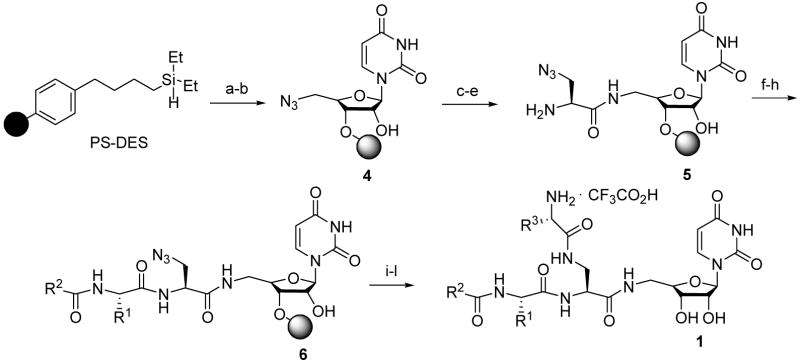

A 1000-member library with three sites of diversity(R110 × R210 × R310) was synthesized using IRORI directed sorting technology11 as outlined in Scheme 1. The two sets of Fmoc protected amino acids (Fmoc-AA1 or AA2-OH) and one set of isocyanates or chloroformates with diverse functional groups were selected as building blocks for the synthesis and are listed in Figure 3. Solid-supported PS-DES-Ser(N3)-uridine 5 was prepared in bulk in a 500 mL solid-phase peptide synthesizer using a five step synthesis of PS-DES resin activation,12 resin loading, azide reduction, Fmoc-Ser(N3)-OH coupling, and Fmoc removal using standard protocols.7 The only minor modification was the Fmoc removal step, which was performed using 25% 4-methylpiperidine rather than piperidine due to new restrictions on the use of piperidine.13 The freshly prepared resin 5 was evenly distributed into 1000 MiniKans containing Rf tags (60 mg, 0.087 mmol/Kan). The first library step was then performed by Fmoc-AA1-OH coupling using DIC-HOBt activation, in 10 reaction flasks each containing 100 MiniKans.7 This was followed by washing, pooling, Fmoc deprotection on mass prior to sorting into 10 reaction vessels. Capping with the second diversity element using either isocyanates R2 {1-9} or chloroformate R2 {10} was then performed to provide the corresponding solid supported urea or carbamate derivatives 6. Washing and pooling of MiniKans was followed by azide reduction to activate the branching position. The final diversity step of Fmoc-AA2-OH coupling was then performed. Fmoc deprotection and final simultaneous cleavage of the linker and side chain protecting groups by 10% TFA in DCM gave the targeted library 1 as discrete compounds.

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of targeted library 1 on solid supporta,b

aReagents and conditions: (a) 1,3-dichloro-5,5-dimethylhydantoin (3 eq.), anhydrous CH2Cl2, rt, 2 h; (b) 5′-azido-5′-deoxyuridine (3 eq.), imidazole (3.5 eq.), anhydrous DMF, rt, 4 h; (c) SnCl2/HSPh/NEt3 (1:4:5), rt, overnight; (d) Fmoc-Ser(N3)-OH (5 eq.), HOBt (5 eq.), anhydrous CH2Cl2/DMF(1/1, v/v), DIC (5 eq.), rt, 5 h; (e) 4-methylpiperidine/DMF (25%, v/v), rt, 20 min.; (f) Fmoc-AA1-OH (3.5 eq.), HOBt (3.5 eq.), anhydrous CH2Cl2/DMF (1/1, v/v), DIC (3.5 eq.), rt, overnight; (g) 4-methylpiperidine/DMF (25%, v/v), rt, 1 h; (h) R2NCO or i-butylOC(O)Cl/TEA (4 eq.), anhydrous CH2Cl2, 24 h; (i) SnCl2/HSPh/NEt3 (1:4:5), rt, overnight; (g) Fmoc-AA2-OH (3.5 eq.), HOBt (3.5 eq.), anhydrous CH2Cl2/DMF (1/1, v/v), DIC (3.5 eq.), rt, overnight; (k) 4-methylpiperidine/DMF (25%, v/v), rt, 1 h; (l) 10% TFA/CH2Cl2, rt, overnight.

bThe point of attachment of 5′-azido-5′-deoxyuridine to the solid support could be via 2′-OH or 3′-OH.

Figure 3.

Building blocks for library 1 (10×10×10) synthesis.

The same set of building blocks as AA1 {1-10} except for {2} Fmoc-Phe-OH was used to replace Fmoc-ß-Ala-OH and {9} Fmoc-Phe(NO2)-OH was used to replace Fmoc-Phe-OH

Library members bearing the same R3 substituent from the last step synthesis were archived in glass vials in 8 × 12 array format. A randomly selected row (12 samples) of each array was subsequently selected for reverse phase HPLC and mass spectrometry analysis (total 120 samples, 12% of library size). Purity of products was confirmed by HPLC with UV254nm detection and MS. Thirty percent of the samples analyzed had > 80% HPLC purity, 43% had HPLC purity ranging from 60-80%, 21% had 40-60% purity, and 6% gave an HPLC purity of < 40%. Among the 120 analyzed samples, 97% of them provided the desired product by mass spectrometry. The overall yield was slightly disappointing, 8% by gravimetric analysis. However, this yield was sufficient to supply enough compound for all the required antimicrobial testing in multiple assays.

This library was screened for anti-tuberculosis activity.14 Ten initial hits were identified from primary screening against M. tuberculosis (H37Rv). These ten library members were subsequently resynthesized by applying the same solid-phase methodology, purified by preparative RP-HPLC, and retested. Their characterization data and anti-tuberculosis activity are shown in Table 1. The structures of these compounds were assigned and confirmed by mass spectrometry, 1H and 13C NMR, 1H-13C HSQC, and 1H-1H COSY.15 The most active compounds are 1 {9,1,10}, {8,5,9}, {8,1,10}, and {10,5,10} with MIC value of 12.5 μg/mL.

Table 1.

Characterization data and anti-tuberculosis activity of library members after resynthesis, purification and retesting of primary hits

| Compds | MS [M+Na]a (m/z) | HPLC purityb (%) | tRc (min) | MIC90 (μg/mL) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 {10,8,7} | 813.4 | 100(100) | 4.67 | >200 |

| 1 {10,8,10} | 885.5 | 100(100) | 4.94 | 50 |

| 1 {10,6,10} | 871.5 | 100(100) | 5.09 | 50 |

| 1 {10,1,10} | 851.5 | 100(100) | 5.22 | 25 |

| 1 {10,9,10} | 809.5 | 100(100) | 4.83 | 100 |

| 1 {9,1,10} | 790.5[M+1] | 100(100) | 5.23 | 12.5 |

| 1 {8,5,9} | 856.5 | 100(100) | 4.79 | 12.5 |

| 1 {8,1,10} | 806.5[M+1] | 100(100) | 5.04 | 12.5 |

| 1 {4,6,9} | 822.5 | 100(100) | 4.99 | 100 |

| 1 {10,5,10} | 873.5 | 96(98) | 4.98 | 12.5 |

Mass spectra were recorded on a Bruker Esquire LC-MS using ESI.

Analytical RP-HPLC was conducted on a Shimadzu HPLC system with a Phenomenex C18 column (100Å, 3 μm, 4.6 × 50 mm), flow rate 1.0 mL/min and a gradient of solvent A (H2O 0.1% TFA) and solvent B (CH3CN): 0-2.min 100% A; 2-8.min 0-100% B (linear gradient). UV detection at 254 nm; figures in parenthesis indicate HPLC purity detected at 218 nm.

Retention time.

Hydrophobic moieties (e.g., tryptophan at R3 position and n-hexyl or 4-methoxyphenyl at R2 position) appear to be required for anti-tuberculosis activity. These ten compounds were also assessed for antimicrobial activity against B. anthracis (Sterne strain), B. subtilis, E. coli (K-12), E. faecalis, and methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus (MSSA). No inhibitory activity was found, this suggests that these compounds have the potential to be developed into narrow spectrum antibiotics targeting M. tuberculosis.

In conclusion, a more complex uridinyl branched peptide urea library was synthesized using IRORI directed sorting technologies. High-throughput screening of this library identified several library members with moderate anti-tuberculosis activity (MIC: 12.5 μg/mL). These compounds represented a good starting point for further expansion and optimization, a more focused small library is currently being designed and synthesized in an effort to enhance this activity of this class. Studies to determine if these compounds inhibit the MraY pathway in M. tuberculosis remain to be performed. These studies will be reported in due course.

Figure 4.

Uridinyl branched peptide urea targeted library 1.

Acknowledgments

We thank National Institutes of Health grant AI057836 for financial support. We thank Angela Buckman for help with the large scale preparation of Fmoc-Ser(N3)-OH and Jerrod Scarborough’s assistance with HPLC analysis of the library.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References and Notes

- 1.Antimicrobial Resistance. WHO Fact Sheet No 194. Geneva: Health Communications, WHO; 2002. http://www.who.int/inf-fs/en/fact194.html. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Inukai M, Isono F, Takahashi S, Enokita R, Sakaida Y, Haneishi T. J Antibiot. 1989;42:662. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.42.662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Isono F, Katayama T, Inukai M, Haneishi T. J Antibiot. 1989;42:674. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.42.674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Inukai M, Isono F, Takatsuki A. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1993;37:980. doi: 10.1128/aac.37.5.980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.For papers related to Mureidomycins, see: Gentle CA, Bugg TDH. J Chem Soc Perkin Trans. 1999;1:1279.Gentle CA, Harrison SA, Inukai M, Bugg TDH. J Chem Soc Perkin Trans. 1999;1:1287.Bozzoli A, Kazmierski W, Kennedy G, Pasquarello A, Pecunioso A. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2000;10:2759. doi: 10.1016/s0960-894x(00)00560-6.Howard NI, Bugg TDH. Bioorg Med Chem. 2003;11:3083. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0896(03)00270-0. For papers related to pacidamycins, see: Boojamra CG, Lemoine RC, Lee JC, Léger R, Stein KA, Vernier NG, Magon A, Lomovskaya O, Martin PK, Chamberland S, Lee MD, Hecker SJ, Lee VJ. J Am Chem Soc. 2001;123:870. doi: 10.1021/ja003292c.Boojamra CG, Lemoine RC, Blais J, Vernier NG, Stein KA, Magon A, Chamberland S, Hecker SJ, Lee VJ. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2003;13:3305. doi: 10.1016/s0960-894x(03)00682-6.

- 6.Sun D, Lee RE. Tetrahedron Lett. 2005;46:8497. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sun D, Lee RE. J Comb Chem. 2007;9:370. doi: 10.1021/cc060154w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.For a recent review regarding naturally occurring nucleoside antibiotics, see: Kimura K, Bugg TDH. Nat Prod Rep. 2003;20:252. doi: 10.1039/b202149h.

- 9.Fmoc-Dpr(ivDde)-OH is available from Novabiochem, ($948/5 g).

- 10.Schmidt U, Mundinger K, Biedl B, Haas G, Lau R. Synthesis. 1992;1201 [Google Scholar]

- 11.http://www.irori.com

- 12.PS-DES resin (100-200 mesh, loading: 1.45 mmol/g) is commercially available from Argonaut Technologies, now a Biotage company.

- 13.Hachmann J, Lebl M. J Comb Chem. 2006;8:149. doi: 10.1021/cc050123l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Compounds were screened for MIC activity against M. tuberculosis H37Rv using the microbroth dilution method in Middlebrook 7H9 ADC media according to CLSI guidelines. Compounds were dissolved and diluted in DMSO. 4μl of this solution was then added to 196μl of culture media containing 2×104 bacteria. In the primary assay compounds were tested at 20, 10, 5μg/ml concentrations, based on recovered yield. The resynthesized compounds were tested as a serial 1:1 dilution from 200 to 1.56 μg/ml for accurate MIC determination. A hit in the primary screen assay was determined to be compounds with MIC90 <20 μg/ml Controls included wells containing no drug as a negative control and Isoniazid as a positive control (reproducible MIC90 0.031 μg/ml).

-

15.Representative analytical data for library members after resynthesis and purification by preparative HPLC.

1 {9,1,10}. 64.4 mg, 17.8% overall purified yield. 1H NMR, 500 MHz (DMSO-d6): δ 11.34 (d, 1H, J = 1.7 Hz, N3H), 10.98 (d, J = 2.0 Hz, 1H, NH(Trp)), 8.58 (t, J = 5.7 Hz, 1H, NH), 8.14 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 1H, NH), 8.05 (t, J = 5.6 Hz, 1H, NH), 8.02 (d, J = 3.9 Hz, 3H, ), 7.70 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H, CH(Trp)), 7.66 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 1H, C6H), 7.36 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 1H, CH(Trp)), 7.26 (m, 2H, Phe), 7.19 (m, 4H, 3CH(Phe) and CH(Trp)), 7.09 (dd, J = 7.1 and 8.1 Hz, 1H, CH(Trp)), 7.00 (dd, J = 7.1 and 7.8 Hz, 1H, CH(Trp)), 6.18 (t, J = 5.4 Hz, 1H, NH(Urea)), 6.11 (d, J = 6.8 Hz, 1H, NH(Urea)), 5.74 (d, J = 5.4 Hz, 1H, H-1′), 5.63 (dd, J = 2.0 and 8.1 Hz, 1H, C5H), 5.42 (br s, 1H, OH), 5.18 (br s, 1H, OH), 4.47 (m, 1H, CH(Ser)), 4.24 (m, 1H, CH(Phe)), 4.06 (t, J = 5.4 Hz, 1H, H-2′), 3.95 (m, 1H, CH(Trp)), 3.86 (m, 2H, H-3′ and H-4′), 3.20-3.58 (m, 5H, CH2-5′, CH2(Ser), and CHa(Trp)), 3.02 (m, 2H, CHa′ (Trp) and CHb(Phe)), 2.89 (m, 2H, NCH2(n-Hex)), 2.79 (dd, J = 9.5 and 13.9 Hz, 1H, CHb (Phe)), 1.22 (m, 8H(n-Hex)), 0.84 (t, J = 7.1 Hz, 3H, CH3(n-Hex)). 13C NMR, 500 MHz (DMSO-d6): δ 172.50, 169.72, 168.96, 163.06, 158.10, 150.71, 141.27, 137.84, 136.34, 129.18, 128.11, 127.01, 126.28, 124.96, 121.16, 118.42, 111.47, 106.87, 102.00, 88.32, 82.33, 72.52, 70.84, 55.13, 52.85, 52.55, 41.22, 40.49, 39.0 (overlapped with DMSO-d6 peak), 37.54, 31.02, 29.67, 27.33, 26.00, 22.07, 13.92. Mass spectrum (ESI) m/z [M+1]+ 790.5. HPLC purity: 100%, tR = 5.23 min.

1 {9,1,10}. 64.4 mg, 17.8% overall purified yield. 1H NMR, 500 MHz (DMSO-d6): δ 11.34 (d, 1H, J = 1.7 Hz, N3H), 10.98 (d, J = 2.0 Hz, 1H, NH(Trp)), 8.58 (t, J = 5.7 Hz, 1H, NH), 8.14 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 1H, NH), 8.05 (t, J = 5.6 Hz, 1H, NH), 8.02 (d, J = 3.9 Hz, 3H, ), 7.70 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H, CH(Trp)), 7.66 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 1H, C6H), 7.36 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 1H, CH(Trp)), 7.26 (m, 2H, Phe), 7.19 (m, 4H, 3CH(Phe) and CH(Trp)), 7.09 (dd, J = 7.1 and 8.1 Hz, 1H, CH(Trp)), 7.00 (dd, J = 7.1 and 7.8 Hz, 1H, CH(Trp)), 6.18 (t, J = 5.4 Hz, 1H, NH(Urea)), 6.11 (d, J = 6.8 Hz, 1H, NH(Urea)), 5.74 (d, J = 5.4 Hz, 1H, H-1′), 5.63 (dd, J = 2.0 and 8.1 Hz, 1H, C5H), 5.42 (br s, 1H, OH), 5.18 (br s, 1H, OH), 4.47 (m, 1H, CH(Ser)), 4.24 (m, 1H, CH(Phe)), 4.06 (t, J = 5.4 Hz, 1H, H-2′), 3.95 (m, 1H, CH(Trp)), 3.86 (m, 2H, H-3′ and H-4′), 3.20-3.58 (m, 5H, CH2-5′, CH2(Ser), and CHa(Trp)), 3.02 (m, 2H, CHa′ (Trp) and CHb(Phe)), 2.89 (m, 2H, NCH2(n-Hex)), 2.79 (dd, J = 9.5 and 13.9 Hz, 1H, CHb (Phe)), 1.22 (m, 8H(n-Hex)), 0.84 (t, J = 7.1 Hz, 3H, CH3(n-Hex)). 13C NMR, 500 MHz (DMSO-d6): δ 172.50, 169.72, 168.96, 163.06, 158.10, 150.71, 141.27, 137.84, 136.34, 129.18, 128.11, 127.01, 126.28, 124.96, 121.16, 118.42, 111.47, 106.87, 102.00, 88.32, 82.33, 72.52, 70.84, 55.13, 52.85, 52.55, 41.22, 40.49, 39.0 (overlapped with DMSO-d6 peak), 37.54, 31.02, 29.67, 27.33, 26.00, 22.07, 13.92. Mass spectrum (ESI) m/z [M+1]+ 790.5. HPLC purity: 100%, tR = 5.23 min. 1 {8,5,9}. 75.0 mg, 19.8% overall purified yield. 1H NMR, 500 MHz (DMSO-d6): δ 11.34 (d, 1H, J = 1.7 Hz, N3H), 9.20 (br s, 1H, OH), 8.54 (t, J = 5.7 Hz, 1H, NH), 8.49 (s, 1H, NH(Urea)), 8.36 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 1H, NH), 8.10 (m, 5H, CH, CH, and ), 8.02 (t, J = 5.7 Hz, 1H, NH), 7.66 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 1H, C6H), 7.45 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 2H), 7.13 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 2H), 6.99 (d, J = 8.3 Hz, 2H), 6.72 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 2H), 6.66 (d, J = 8.3 Hz, 2H), 6.17 (d, J = 7.1 Hz, 1H, NH(Urea)), 5.74 (d, J = 5.4 Hz, 1H, H-1′), 5.64 (dd, J = 2.0 and 8.1 Hz, 1H, C5H), 5.45 (br s, 1H, OH), 5.18 (br s, 1H, OH), 4.52 (m, 1H, CH(Ser)), 4.36 (m, 1H, CH(Tyr)), 4.06 (t, J = 5.1 Hz, 1H, H-2′), 4.02 (m, 1H, CH(Phe(4-NO2)), 3.87 (m, 2H, H-3′ and H-4′), 3.68 (m, 1H, CHa(Ser)), 3.67 (s, 3H, CH3), 3.34 (m, overlapped with H2O peak, 2H, CH2-5′), 3.16 (m, 2H, CHa (Ser) and CHb (Phe(4-NO2)), 2.94 (m, 2H, CHb′ (Phe(4-NO2)) and CHc(Tyr)), 2.69 (dd, J = 8.8 and 13.9 Hz, 1H, CHc′ (Tyr)). 13C NMR, 500 MHz (DMSO-d6): δ 172.40, 169.68, 168.06, 163.04, 155.90, 155.15, 153.95, 150.69, 146.71, 143.06, 141.17, 133.11, 130.88, 130.10, 127.38, 123.46, 119.05, 115.01, 113.81, 101.99, 88.33, 82.28, 72.56, 70.89, 55.04, 54.79, 53.15, 51.96, 41.19, 40.56, 37.21, 36.53. Mass spectrum (ESI) m/z [M+Na]+ 856.5. HPLC purity: 100%, tR = 4.79 min.

1 {8,5,9}. 75.0 mg, 19.8% overall purified yield. 1H NMR, 500 MHz (DMSO-d6): δ 11.34 (d, 1H, J = 1.7 Hz, N3H), 9.20 (br s, 1H, OH), 8.54 (t, J = 5.7 Hz, 1H, NH), 8.49 (s, 1H, NH(Urea)), 8.36 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 1H, NH), 8.10 (m, 5H, CH, CH, and ), 8.02 (t, J = 5.7 Hz, 1H, NH), 7.66 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 1H, C6H), 7.45 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 2H), 7.13 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 2H), 6.99 (d, J = 8.3 Hz, 2H), 6.72 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 2H), 6.66 (d, J = 8.3 Hz, 2H), 6.17 (d, J = 7.1 Hz, 1H, NH(Urea)), 5.74 (d, J = 5.4 Hz, 1H, H-1′), 5.64 (dd, J = 2.0 and 8.1 Hz, 1H, C5H), 5.45 (br s, 1H, OH), 5.18 (br s, 1H, OH), 4.52 (m, 1H, CH(Ser)), 4.36 (m, 1H, CH(Tyr)), 4.06 (t, J = 5.1 Hz, 1H, H-2′), 4.02 (m, 1H, CH(Phe(4-NO2)), 3.87 (m, 2H, H-3′ and H-4′), 3.68 (m, 1H, CHa(Ser)), 3.67 (s, 3H, CH3), 3.34 (m, overlapped with H2O peak, 2H, CH2-5′), 3.16 (m, 2H, CHa (Ser) and CHb (Phe(4-NO2)), 2.94 (m, 2H, CHb′ (Phe(4-NO2)) and CHc(Tyr)), 2.69 (dd, J = 8.8 and 13.9 Hz, 1H, CHc′ (Tyr)). 13C NMR, 500 MHz (DMSO-d6): δ 172.40, 169.68, 168.06, 163.04, 155.90, 155.15, 153.95, 150.69, 146.71, 143.06, 141.17, 133.11, 130.88, 130.10, 127.38, 123.46, 119.05, 115.01, 113.81, 101.99, 88.33, 82.28, 72.56, 70.89, 55.04, 54.79, 53.15, 51.96, 41.19, 40.56, 37.21, 36.53. Mass spectrum (ESI) m/z [M+Na]+ 856.5. HPLC purity: 100%, tR = 4.79 min.