Short abstract

The Department of Health's Medicines Partnership is encouraging a shift away from the concept of drug compliance, with its tacit assumption of obedience and coercion, to one of concordance. However, Iona Heath argues that this is, at best, misguided and, at worst, simply window dressing

In 1997 a report of a working party of the Royal Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britain acknowledged that prescribing is “a technically difficult, and morally complex, problem” and that compliance is an ethically dubious aspiration.1 The report proposed the use of a new term—concordance—which was intended to describe the creation, during the process of prescribing, of an agreement that respected the beliefs and wishes of the patient.2 The intention of the working party was to foster a distinct change in culture in the relation between prescribing and drug taking and between patient and prescriber. The intention was honourable, but the initiative seems to be foundering.

Compliance

Compliance is indeed a pernicious concept which devalues patients and leaves the hubris of doctors dangerously exposed. It derives from the foundation of medical science within a modernist rationality, which seeks to identify general rules that can be applied to standardised situations. However, in the care of patients, doctors attempt to apply general rules to particular individuals in situations that are never standard and where there is no single right answer. When doctors exploit their power and claim a monopoly of relevant knowledge, the autonomy, dignity, and even legal rights3 of patients may be compromised. This inappropriate use of power is reflected in the concept of compliance, which embodies the belief that “doctor knows best” and implies that patients' responsibility is simply to follow medical advice.

The Medicines Partnership

In 2002 the Department of Health responded to the recommendations of the Royal Pharmaceutical Society's report by endorsing the concept of concordance and creating the Medicines Partnership Task Force. The task force has a budget of £1.3m ($2.2m, €1.9m) and a dedicated website.4 Scrutiny of the material posted on the website suggests that the intention of placing the processes of prescribing on a firmer ethical foundation is coming apart and that concordance is in danger of becoming little more than a modernist wolf in post-modernist clothing.5 While paying lip service to the view that the patient's version of truth is as valid as the doctor's, the rhetoric of the website clings to the conviction that there is, after all, a single objective account of reality and that this account is provided by medical science. The notion of compliance is at least explicitly coercive; the danger of concordance is that the coercion remains but is concealed.

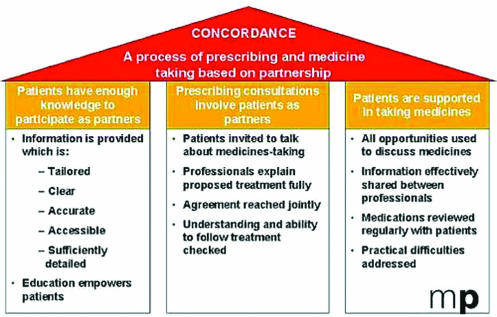

The website text implies, repeatedly, that every failure to establish concordance between doctor and patient carries a cost to the patient, the NHS, and society. Doctors and other healthcare professionals are accused of “pervasive failures to establish effective therapeutic partnerships” with their patients. One of the three pillars of concordance (see figure) is providing information that is tailored, clear, accurate, accessible, and sufficiently detailed, even though there is no evidence to show that more information improves compliance. Any doctor who has been a non-compliant patient knows that lack of information is not the issue. The website makes repeated calls for more education and training for healthcare professionals despite a lack of evidence for the effectiveness of such interventions. All this conveys a clear message that the best sort of concordance is one that looks very like the old model of compliance but with a contented patient who, in the language of the website, has been empowered to comply through education.

Figure 1.

Concordance as defined by the Medicines Partnership: “a new way to define the process of successful prescribing and medicine taking, based on partnership. It has three essential elements (shown above)” (www.medicines-partnership.org/about-us/concordance)

Excessive confidence in our present state of knowledge

History suggests that every generation of doctors looks back complacently at the ignorance of its predecessors while overestimating the robustness and longevity of its own knowledge. Many patients seem wiser and more cautious, apparently fully aware of the evolutionary process whereby today's miracle cure becomes tomorrow's killer. The recent research on the risks of hormone replacement therapy provides only the latest example of the shifting sands of medical knowledge.6 Medical science clings to a belief in measurable, linear relations between inputs and outputs in health care, despite the insights of complexity science that are starting to explain the clinical reality whereby the same treatment applied to different individuals carrying the same diagnostic label will have very different results. Whatever the strength of the evidence, no clinician can ever guarantee that any particular patient will benefit from the treatment that he or she offers.

The simplistic presentation of the vast majority of health education literature gives patients no notion of the uncertainties of the decision that both they and their doctors are facing. Where is the patient information on any topic that includes a discussion of numbers needed to treat and numbers needed to harm?7

The different contexts of preventive care, acute care of life threatening situations, and long term care of chronic illnesses have a profound effect on the priorities of both doctors and patients. According to one study, only 8% of Muslim patients believe that it is acceptable to use haraam drugs (containing forbidden components such as gelatine or alcohol) to treat a minor illness, whereas 36% believe that it is acceptable in more serious situations.8 Patients seem to operate a sliding scale, balancing the probability of benefit and the gravity of the situation against their own beliefs and values. Yet the professional literature seems to apply the concepts of both compliance and concordance in a blanket manner across diverse clinical circumstances,9 not even drawing a clear distinction between the compliance that may be required to protect the health of others, as in the case of tuberculosis or HIV infection, and that which affects only the health of the individual concerned.

Excessive prescribing

The PowerPoint presentation provided on the Medicines Partnership website begins with the assertion that, at any one time, 70% of the UK population is taking medicines to treat or prevent ill health or to enhance wellbeing. This statement is made with no further comment, but how can this level of drug taking be appropriate in a population that, by all objective measures, is healthier than ever before in history? The excessive consumption of drugs, particularly preventive medication, in richer countries is a powerful driver of global health inequalities, when there is much more profit to be made from developing and selling drugs to the rich and well than to the poor and sick.10

Excessive prescribing also drives iatrogenesis to the extent that 28% of US hospital admissions of elderly people are estimated to be caused by a drug related problem, with substantially more being the result of adverse reactions than of non-compliance.11 Too often a prescribing cascade is set in motion whereby the side effects of one drug produce a new health problem, and so a second drug is prescribed, which in turn produces a new symptom and the need for a third drug.12 The pathway that leads from osteoarthritis to a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug to mild hypertension to a thiazide diuretic and on to diabetes or gout is but one example. The rhetoric of compliance and, more recently, concordance seems to endorse excessive prescribing uncritically and unethically.

Is concordance the wrong term?

Until doctors and health policy makers accept that the patient, and the patient alone, has the right to decide whether he or she will take a drug, the change from compliance to concordance will remain cosmetic. Perhaps, after all, the problem is that concordance is the wrong term because it exaggerates the potential for concord between the aspirations of medical science and those of individual patients striving to make the best of complicated and challenging lives.

The transformation must be much more radical. What is needed is a term that makes explicit the likelihood of divergence and, indeed, the usefulness of disagreement as the basis of dialectic within a meeting of experts.13 If the dignity and autonomy of each patient is to be genuinely respected, the outcome of the consultation will often conflict with recommended medical guidance.14 Fundamentally, this is simply another manifestation of that familiar conflict between the utilitarian benefit of the many and the dignity and freedom of the individual, which has persisted throughout history as each successive utopian dream has degenerated into tyranny.15 The dream of perfect health is the contemporary utopia and comes, as always, accompanied by coercion. We need a term that draws attention to the possibility of coercion and helps to resist it. Concordance doesn't do this.

Patients need different information, not more of the same, and there is an urgent need for more honesty about the limitations of medicine and the uncertainties of medical knowledge. Patients need to be aware of the possibility of both benefits and harms and helped to make decisions based on their own valuation of the various possible outcomes.16 Information technology has the potential to support sophisticated modelling of this sort of decision making and, if it were serious about the original intention of concordance, the Medicines Partnership would surely be investing more effort in this area. The nub of the matter is that the extremely limited research into decision analysis (itself a relatively crude technique) shows that patients will make a range of decisions, many of which reject the standard medical advice.17 This is the outcome that the Medicines Partnership should be defending and promulgating. It is the only outcome that ensures that patients retain the freedom to set their own standards for health and to live their lives as they see fit.

Summary points

The notion of compliance is explicitly coercive; the danger of concordance is that the coercion remains but is concealed

The rhetoric of both compliance and concordance endorses excessive prescribing uncritically

Patients need different information, not more of the same, and more honesty about the uncertainties of medical knowledge is urgently needed

The Medicines Partnership should be investing more in techniques that help patients to make their own decisions based on their own values and priorities

Doctors have a responsibility to use their professional knowledge to envisage how patients' health could be improved, but they have no right to impose that vision on patients unless they lack the capacity to make their own decisions (when, under English law, a doctor is obliged to act in the patient's “best interest”). With this exception, there is no place for coercion in health care and, when it occurs, the profound comfort is how often patients arrange to subvert it through the tried and tested strategy of non-compliance.

Contributors and sources: IH has been a general practitioner in inner London since 1975 and has been chair of the Committee on Medical Ethics of the Royal Society of General Practitioners since 1998. In preparing this article, IH searched Medline for the terms “compliance” and “concordance.” Concordance yielded no useful information as this sense of the word is not recognised by Medline. IH also searched the internet for both terms using the Google search engine.

Competing interests: None declared

References

- 1.Royal Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britain. From compliance to concordance: achieving shared goals in medicine taking. London: RPS, 1997.

- 2.Marinker M, Shaw J. Not to be taken as directed. BMJ 2003;326: 348-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Donaldson MR. Re T (adult: refusal of medical treatment). [ 1992] 4 All ER 649-64.

- 4.Medicines Partnership. www.concordance.org, www.medicinespartnership.org (modified 12 Sep 2003).

- 5.Hodgkin P. Medicine, postmodernism, and the end of certainty. BMJ 1996;313: 1568-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Million Women Study Collaborators. Breast cancer and hormone-replacement therapy in the million women study. Lancet 2003;362: 419-27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Thornton H, Edwards A, Baum M. Women need better information about routine mammography. BMJ 2003;327: 101-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bashir A, Asif M, Lacey FM, Langley CA, Marriott JF, Wilson KA. Concordance in Muslim patients in primary care. Int J Pharm Pract 2001:9(suppl): R78. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Carter S, Taylor D, Levenson R. A question of choice—compliance in medicine taking. London: Medicines Partnership, 2003.

- 10.Pollock AM, Price D. New deal from the World Trade Organization. BMJ 2003;377: 571-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Col N, Fanale JE, Kronholm P. The role of medication non-compliance and adverse drug reactions in hospitalizations of the elderly. Arch Intern Med 1990;150: 841-5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rochon PA, Gurwitz JH. Optimising drug treatment for elderly people: the prescribing cascade. BMJ 1997;315: 1096-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tuckett D, Boulton M, Olson C, Williams A. Meetings between experts: an approach to sharing ideas in medical consultations. London: Tavistock, 1985.

- 14.Metcalfe D. The crucible. J R Coll Gen Pract 1986;36: 349-54. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zbigniew H. Damastes (also known as Procrustes) speaks. In: Report from the besieged city and other poems. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1983.

- 16.Butler CC, Kinnersley P, Prout H, Rollnick S, Edwards A, Elwyn G. Antibiotics and shared decision making in primary care. J Antimicrob Chemother 2001;48: 435-40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dowell J, Jones A, Snadden D. Exploring medication use to seek concordance with “non-adherent” patients: a qualitative study. Br J Gen Pract 2002;52: 24-32. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]