Short abstract

What information do patients need about medicines? Partnership between health professionals and patients depends, in part, on the provision and exchange of accurate and reliable information about drugs, but who should provide it? We invited contributors to answer the question from the perspectives of patients, clinicians, and the pharmaceutical industry

“Drugs don't work in patients who don't take them.” This famous observation by C Everett Koop, former US surgeon general, is reinforced by the findings of a recent World Health Organization report on adherence to long term treatments. On average, half of the patients prescribed drugs for chronic conditions (such as hypertension, hypercholesterolaemia, and diabetes) in developed countries stop taking them after a year, and adherence rates are even worse in developing countries. The WHO concludes that improving adherence requires multidisciplinary and multilevel interventions that take individual patients' experiences of illness seriously. The impact of non-compliance—through avoidable morbidity and mortality, the cost of additional medical interventions, and (indirectly) lost productivity at work—adds considerably to the costs of health care.1

Providing access to accurate, balanced, evidence based, and comprehensive information about health-care options is particularly important in improving patients' adherence to treatment. When they are prescribed drugs, patients should also be able to obtain easily understandable information about the expected benefits and potential outcomes, and any risks, interactions, and side effects.

How can the pharmaceutical industry help?

European patients and consumers are increasingly demanding better access to such information to help them make informed choices about their health.2 Patients who take an active role in managing their health have better health outcomes than those who do not, and are therefore cost effective patients for society. This reinforces the case for better information for patients: it makes sense for both patients and the healthcare system.3

Pharmaceutical companies—which often have the best information on the drugs they discover, develop, manufacture, and market (with each activity carefully regulated at both European and national level)—have a role to play in meeting this demand for accurate and reliable health information. Such companies are uniquely positioned to provide comprehensive scientific and clinical information, where allowed by law, about their products based on the data obtained through the arduous process of preclinical research and clinical and regulatory development. These resources will be particularly important as doctors help patients to understand the optimum use of drugs, how to manage any side effects, and how to maximise their benefits by adherence to the proper regimen.

Evidence from consumer surveys and other studies show, for example, that “direct to consumer” communications from pharmaceutical companies provide valuable information on the benefits of treatments (and on risks and side effects); motivate consumers to seek additional information from physicians, pharmacists, and other sources; and help patients to improve adherence to treatment and make behavioural changes to improve health.4,5

Looking ahead

We think that patients and consumers would benefit most from a variety of tools to help them navigate through the wealth of information available from print, broadcast, and electronic sources, coupled with clear guidelines for judging the quality of the information (such as those proposed for internet information sources by the European Federation of Pharmaceutical Industries and Associations6), along with training in health literacy for consumers and providers. Developing such initiatives—and deciding how they should be structured, funded, and maintained—is an important opportunity for the European public health agenda in the years ahead.

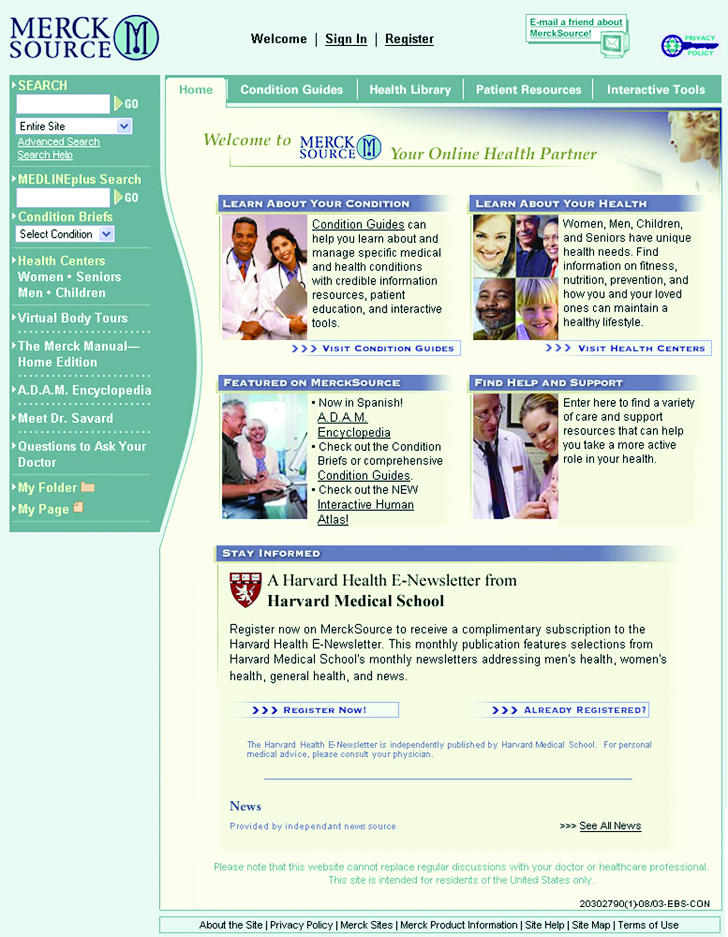

What might such information sources look like in practice? Merck's website (www.merck.com) provides an example of what a pharmaceutical company can offer, in its section Patients and Caregivers and in the Merck Manual Home Edition. The latter provides complete information about many therapeutic areas written in readily understandable language. The MerckSource website offers a portal into an extensive library of authoritative and readable reference works, balanced information on medical conditions and general health issues, and practical guides (from an independent source) of questions for patients to ask their physician (see figure). Unlike advertising, which is broadcast or “pushed” at people, these information resources are available to be “pulled” from the web when consumers and patients choose to seek them out.

Figure 1.

MerckSource provides patients and caregivers in the United States with a comprehensive guide to online health information and related resources they can use when they need them

Conclusions

Liberalisation of the guidelines governing direct to patient information from the pharmaceutical industry (in both print and electronic form) would help to broaden the range of resources available to patients who want to take a more active role in their own health care, enrich the dialogue between patients and health professionals, and thus improve adherence to long term treatment, with consequent improvement in clinical outcomes.

Contributors and sources: SB is responsible for (among other areas) global patient information materials related to Merck products and for much of the content of www.merck.com. JLS has worked with US and European patient organisations on health policy issues (including information for patients) for the past decade. He is a former member of the editorial advisory board of the Patients' Network.

Competing interests: Both authors are full time employees of Merck & Co, also known as Merck Sharp & Dohme.

References

- 1.World Health Organization. Adherence to long-term therapies: evidence for action. Geneva: WHO, 2003.

- 2.Coulter A, Magee H, eds. The European patient of the future. Maidenhead: Open University Press, 2003.

- 3.Greenfield S, Kaplan SH, Ware JE. Expanding patient involvement in care: effects on patient outcomes. Ann Intern Med 1985;102: 520-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bonaccorso SN, Sturchio JL. For and against: Direct to consumer advertising is medicalising normal human experience: against. BMJ 2002;324: 910-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Calfee JE, Winston C, Stempski R. Direct-to-consumer advertising and the demand for cholesterol-reducing drugs. J Law Economics 2002;45: 673-90. [Google Scholar]

- 6.European Federation of Pharmaceutical Industries and Associations. Guidelines for internet web sites available to health professionals, patients and the public in the EU. Brussels: EFPIA, 2001. (www.efpia.org/6_publ/Internetguidelines.pdf)