Short abstract

What is the best way to achieve concordance? The authors summarise the evidence and indicate the way ahead for doctors to involve patients in making decisions about treatment

Much prescribed medicine is not taken, and we know that few patients adhere to “prescription” guidance.1 It is also clear that patients' beliefs and attitudes influence how they take drugs.2 This is particularly true for preventive medicine (thus largely for conditions without symptoms) and for drugs that have side effects or other drawbacks. As interest in the concept of patient autonomy increases, we are becoming more aware, and more respectful, of intentional dissent—where better informed patients decline certain drugs.3 Concordance describes the process whereby the patient and doctor reach an agreement on how a drug will be used, if at all. In this process doctors identify and understand patients' views and explain the importance of treatment, while patients gain an understanding of the consequences of keeping (or not keeping) to treatment.

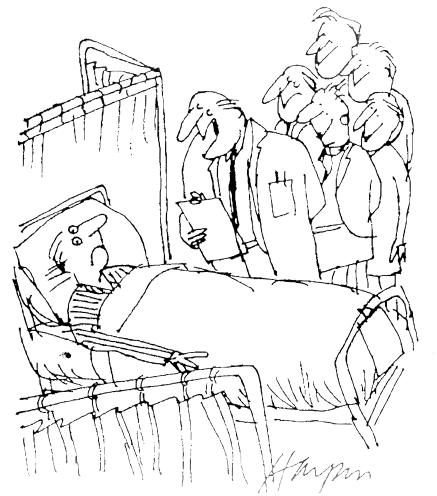

Figure 1.

“When we want your opinion, we'll give it to you”

Credit: PUNCH CARTOON LIBRARY

Evidence base

Few well conducted, randomised controlled trials of interventions to help patients follow their prescriptions have been done.4 Our article is based on a number of reviews in this field and a recent systematic review of concordance.1,4-6 Changes in terminology in this area have mirrored an increasing rejection of the power relation implicit in the term “to prescribe.” The authority laden term “compliance” gave way to the view that patients “adhered” (or not) to treatment. Recently the term concordance has been used to describe an agreed plan between patient and doctor about the use of treatment—one of the results of a shared decision making process.7,8

Box 1: Concordance tasks

Elicit the patient's views on the possibility of having to take medicine

Explore those views with the patient

Inform the patient of the pros and cons of taking and not taking medicine

Involve the patient in the treatment decisions—over time, if necessary, and after reflection

What is known about the prescribing process?

Although the concept of patient centredness has strongly influenced recent teaching practice, training in communication skills has largely concentrated on history taking and diagnosis. Less attention has been paid to decision making tasks, and recent research shows that patients are rarely involved in these processes.9,10

Doctors may initiate a discussion about treatment, but then they dominate the discussion.6 They do not always name the drug they prescribe and may not describe how new drugs differ in mechanism or purpose from those previously prescribed to a patient. They do not usually check patients' understanding of a treatment or explore their concerns about a drug, and when they do encourage patients to ask questions the patients seldom do so.6 Evidence shows that doctors rarely discuss their patients' ability to follow a treatment plan, even though doctors report that they do this in about half of their consultations.6 They discuss the benefits of treatment more than the harms, precautions, or risks, even though patients see these topics as essential.6 Even in formal assessment conditions, where general practitioners are awarded marks for sharing management options with patients, videos show that they fail to do so.11 This failure to explore patients' beliefs and hopes about medicines and to inform them of the pros and cons of treatment options leaves much room for misunderstanding, for unaddressed concerns, and for ambivalence about the drugs prescribed to them.12,13

The patient's perspective

Patients find it hard to adjust to the role of someone who has to take drugs. During this adjustment many doctors do not engage with patients' points of view, seeing the provision of a diagnosis as substantiation enough that medication is a “good thing.”12 Of course, drugs are essential for many patients to maintain reasonable lives: to curb angina, restrain Parkinson's disease, and control asthma and other inflammatory diseases. But many patients with chronic illnesses are ambivalent about medication and experiment with dose titration and drug-free intervals.14 Given that patients are circumspect about taking drugs, such behaviour will be even more marked when the benefits are less clear and not immediate—as with drugs for controlling blood pressure or lowering cholesterol. Gaining an understanding of the harms and benefits of drugs may not go hand in hand with the broader public health goal of reducing the overall risk of a disease.

What can be done?

The interaction between doctor and patient is full of emotional undercurrents, including hope, trust, belief, and confidence. Such emotions are active ingredients in the placebo effect and ought not to abandoned, but the prescribing process has to change for concordance to be achieved. It is no longer tenable for doctors to prescribe without first completing four largely neglected tasks (box 1). These tasks form the basis of the decision sharing skills—the “how to do it” steps for doctors to achieve concordance (box 2).

Patients' views on using drugs may differ widely from those of professionals and should be elicited early, especially as patients may be reticent. For example, it is known that patients don't like to disclose previous self treatments, including complementary treatments. Such disclosure is affected by patients' perceptions of the legitimacy of self treatment, which can only be addressed if doctors discuss it directly.16 If a patient does not want to take a drug for a particular problem you need to acknowledge this wish and discuss the reasons. Patients may have various concerns about drugs that may or may not correspond to the drug's actual adverse reactions or side effects, as described in pharmacological texts. A difficult challenge to concordance is when the doctor and patient disagree over the need for a drug, such as when the patient wants an antibiotic but the doctor is not convinced of the need. In such cases doctors need to pay special attention to the tasks in box 1.

Box 2: Steps for sharing decision making with patients15

Define the problem: clearly specify the problem that requires a decision, taking in your views and the patient's views

Convey equipoise: make it clear that professionals may not have a set opinion about which treatment option is the best, even when the patient's priorities are taken into account

Outline the options: describe one or more treatment options and, if relevant, the consequences of no treatment

Provide information in preferred format: identify the patient's preferences if this will be useful in the decision making process

Check understanding: ascertain the patient's understanding of the options

Explore ideas: elicit the patient's concerns and expectations about the clinical condition, the possible treatment options, and the outcomes

Ascertain the patient's preferred role: check that the patient accepts the decision sharing process and identify his or her preferred role in the interaction

Involve the patient: involve the patient in the decision making process to the extent the patient wishes

Defer, if necessary: review the patient's needs and preferences after he or she has had time for further consideration, including with friends or family, if the patient needs it

Review arrangements: review treatment decisions after a specified time period

When is a patient “informed”?

For patients to be informed, is it sufficient for doctors to outline the options and share information? Critics would say that the key outcome is not the giving of information, or even information exchange, but the achievement of understanding by the patient. This understanding should include awareness of particular outcomes of treatment and their characteristics, including benefits, possible harms, the seriousness of the harms and their probabilities (as expressed in absolute and relative terms), the factors that influence susceptibility, and the difficulty of avoiding harmful consequences.17 It is more likely that such understanding occurs when decision making is seen as a process and not as an outcome (see box 2). Proper understanding means that patients can make informed decisions about treatment, based on balancing assessment of information with their own priorities (box 3).18

Box 3: Characteristics of informed decisions

An informed decision about a treatment option is based on:

Accurate assessment of information about the relevant alternatives and their consequences

Assessment of the likelihood and desirability of the alternatives, in relation to the patients' priorities, and

A “trade-off” between (a) and (b)

Achieving concordance by sharing treatment decisions

Treatment options may be as simple as whether or not to take a drug. When doctors have addressed patients' concerns and provided information the foundation is laid for involving them in the decision itself. Current research into the role of patients in health care is looking at how the role develops as the patient's confidence grows, through engagement in the treatment process and as patients become “expert” at managing their condition during its course. The use of conversation analysis in the study of actual consultations shows that patients need to be helped to play an active role.19,20 However, the roles that patients play are not fixed. Patients sometimes take on more responsibility for their treatment than at other times, according to their particular social circumstances.21 Concordance is a dynamic concept, and achieving it needs continual exploration.

Finding out whether patients wish to take part in the decision making process is a critical step. Although this may be necessary at various specific decision points (tests or referrals, for example), taking a drug is the ultimate expression of personal decision making and “agency,” as it is something we do to ourselves by ourselves, often every day for many years. Even when patients do not want to take part in decision making their views should be taken into account in the prescribing process—otherwise there is a chance of misunderstanding and of low motivation to use the drug. Interactions in which patients are well informed and satisfied with a decision (whether it is to accept or decline an intervention) is better.

Summary points

The way patients take medicines varies widely and is strongly influenced by their beliefs and attitudes

Concordance describes the process whereby patients and professionals exchange their views on treatment and come to an agreement about the need (or not) for a particular treatment

Concordance requires that patients are involved in decision making processes

Ensuring that patients use drugs effectively sometimes requires additional support, such as involvement of patients' support groups and systems for monitoring adherence to treatment

Recent developments

The recent history of guideline implementation shows that exhortations have little impact, however prestigious their source. Doctors can improve their communication and become more skilled at involving patients in decisions, but improving doctors' skills takes time and may not be practical amid the pressure of current clinical settings.6 However, several ways to improve patients' medicine taking hold promise, including the use of patients' groups to inform, educate, and manage drug use22; the monitoring by administrative staff of drug use23; and failsafe reviews of repeat prescribing (of underuse and overuse). In the United Kingdom the Medicines Partnership Task Force is supporting concordance facilitators who can lead local initiatives. An educational resource that helps prescribers to monitor their prescribing has been developed.24

Possible directions

Health care has to come to terms with “agency”—that is, that patients should be able to determine their own preferences. Doctors who start from the position of recognising, respecting, and enhancing the agency and autonomy of patients will also legitimise their own agency as experts and will practice differently. To what extent the enhancement of patients' agency depends on shifts in attitudes of healthcare professionals or on the development of tools to help patients become involved in decision making processes is not yet known.25 It is probable that interventions and innovations in both these areas will be needed, leading not to “adherence” to treatment but to fully considered decisions to take or not take a treatment. Concordance refers to the process by which decisions are made and is not necessarily linked to a behavioural outcome. If we achieve such levels of “informedness” we will have gone a considerable way to involving patients effectively in treatment decisions. Engaging patients in this way is likely to achieve better results for the clinician-patient relationship and to improve health outcomes in the long term, albeit with an acceptance that a trade-off between biomedical improvement and patients' wishes is needed.

Contributors and sources: GE and AE recently hosted the second international conference on shared decision making that the University of Wales, Swansea, and have been active in research in this field. NB is an expert on prescribing behaviours and concordance.

Competing interests: NB was a member of the Concordance Co-ordinating Group of the Royal Pharmaceutical Society, which received funding from Merck Sharp & Dohme, and has been paid for speaking at a conference.

References

- 1.Haynes RB, McDonald H, Garg AX, Montague P. Interventions for helping patients to follow prescriptions for medications. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2002;(2): CD000011. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Britten N, Ukoumunne O, Boulton MG. Patients' attitudes to medicines and expectations for prescriptions. Health Expect 2002;5: 256-69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Coulter A. The autonomous patient. London: Nuffield Trust, 2002.

- 4.McDonald HP, Garg AX, Haynes RB. Interventions to enhance patient adherence to medication prescriptions: scientific review. JAMA 2002;288: 2868-79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carter S, Taylor D. A question of choice: compliance in medicine taking. London: Medicine Partnership, Royal Pharmaceutical Centre, 2003.

- 6.Cox K, Stevenson F, Britten N, Dundar Y. A systematic review of communication between patients and health care professionals about medicine-taking and prescribing. London: GKT Concordance Unit, King's College, 2002.

- 7.Marinker M. Writing prescriptions is easy. BMJ 1997;314: 747-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Elwyn G, Edwards A, Kinnersley P. Shared decision making: the neglected second half of the consultation. Br J Gen Pract 1999;49: 477-82. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Elwyn G, Edwards A, Wensing M, Hood K, Robling M, Atwell C, et al. Fleeting glimpses of shared decision making: developing the OPTION scale for measuring patient involvement. Qual Saf Health Care 2002;12: 93-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stevenson FA, Barry CA, Britten N, Barber N, Bradley CP. Doctor-patient communication about drugs: the evidence for shared decision making. Soc Sci Med 2000;50: 829-40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Campion P, Foulkes J, Neighbour R, Tate P. Patient centredness in the MRCGP video examination: analysis of large cohort. BMJ 2002;325: 691-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Britten N, Stevenson FA, Barry CA, Barber N, Bradley CP. Misunderstandings in prescribing decisions in general practice: qualitative study. BMJ 2000;320: 484-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Barry CA, Bradley CP, Britten N, Stevenson FA, Barber N. Patients' unvoiced agendas in general practice consultations: qualitative study. BMJ 2000;320: 1246-50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Donovan JL, Blake DR. Patient non-compliance: deviance or reasoned decision-making? Soc Sci Med 1992;34: 507-13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Elwyn G, Edwards A, Kinnersley P, Grol R. Shared decision making and the concept of equipoise: defining the competences of involving patients in healthcare choices. Br J Gen Pract 2000;50: 892-9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stevenson FA, Britten N, Barry CA, Bradley CP, Barber N. Self-treatment and its discussion in medical consultations: how is medical pluralism managed in practice? Soc Sci Med 2003;57: 513-27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Weinstein ND. What does it mean to understand a risk? Evaluating risk comprehension. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr 1999;25: 15-20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bekker H. Genetic testing: facilitating informed choices. In: D Cooper, N Thomas (eds). Encyclopaedia of the human genome: ethical, legal and social issues. New York: Nature Publishing Group, 2003.

- 19.Drew P, Chatwin J, Collins S. Conversation analysis: a method for research into interactions between patients and health-care professionals. Health Expect 2001;4: 58-70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.J Gafaranga, N Britten. “Fire away”: the opening sequence in general practice consultations. Fam Pract 2003;20: 242-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ashcroft A, Hope T, Parker M. Ethical issues and evidence based patient choice. In: A Edwards, G Elwyn (eds). Evidence based patient choice: inevitable or impossible? Oxford: Oxford Univeristy Press, 2001.11359538

- 22.Bodenheimer T, Lorig K, Holman H, Grumbach K. Patient self-management of chronic disease in primary care. JAMA 2002;288: 2469-75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Simon GE, VonKorff M, Rutter C, Wagner E. Randomised trial of monitoring, feedback, and management of care by telephone to improve treatment of depression in primary care. BMJ 2000;320: 550-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jenkins L, Britten N, Barber N, Bradley N. Resource pack for reviewing and monitoring prescribing. London: GKT Concordance Unit, King's College, 2002.

- 25.O'Connor AM, Rostom A, Fiset V, Tetroe J, Entwistle V, Llewellyn-Thomas H, et al. Decision aids for patients facing health treatment or screening decisions: systematic review. BMJ 1999;319: 731-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]