Short abstract

Curriculum pressures and a decline in hospital autopsy rates have reduced the opportunity for medical students to learn from autopsy findings

The use of autopsies to teach medical students has been falling worldwide over the past few decades. In 2002, however, Auckland, New Zealand, took the unprecedented step of legally prohibiting students from attending autopsy teaching, by barring them access to coronial autopsies. The decision means that students are denied a highly effective and popular learning resource and the autopsy is likely to decline further in clinical practice. The ultimate losers will be patients. This article examines the evidence supporting the relevance of autopsy in medical education and practice.

Auckland experience

Until recently, learning from autopsy was vibrant in Auckland. Many medical students from third year and above voluntarily attended daily autopsy teaching, and were enthusiastic about this method of learning. However, in early 2002, students were banned from attending coronial autopsies under an interpretation of New Zealand's Coroners Act. The decision was made in the environment following widespread media coverage of the discovery that children's hearts removed at autopsies had been retained for teaching without the family's consent in past decades.1 Media reporting of body organ retention has been noted to increase the negative perception of the autopsy and could result in a further fall from use.2

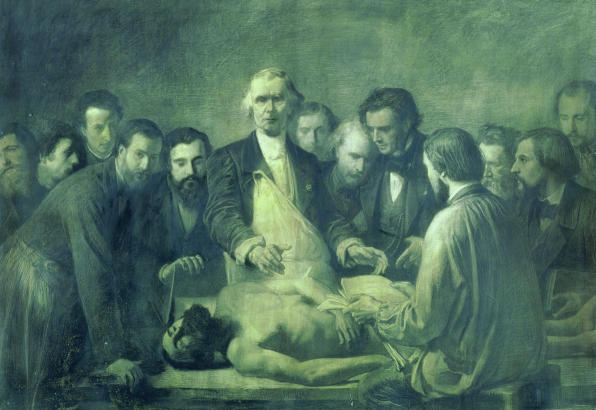

Figure 1.

Learning from autopsy

Credit: GIRAUDON/BAL

Decline of autopsy

At the beginning of the 20th century, autopsy had a fundamental role in medical education, guided by the influential Oslerian philosophy. Students not only attended autopsies, they learnt to conduct them.3 In contrast, today fewer than half of American medical schools require attendance at autopsy, and most students graduate without attending a single session.4

The demise in the educational role of autopsy has followed its decline in hospital practice. The autopsy rate for patients dying in hospital has dropped steeply over the past 40 years in New Zealand, the United Kingdom,2 and the United States.5 Too few hospital autopsies are now conducted in Auckland to provide a useful teaching resource, although rates of coronial autopsies have remained relatively steady. Perhaps the main reason for the fall is an increased confidence in new methods of diagnosis, particularly modern imaging techniques.2,6-8 Other reasons include doctors' discomfort in requesting permission from families, cost containment, and doubts about the value of the procedure.2,5-7 Fear of malpractice suits and pathologist apathy may also have had a role.5,7 Even when an autopsy is performed, the information is often underused, with unacceptable delays in reporting and a lack of participation from the clinicians involved.7-9

Educational role of autopsy

Hill and Anderson identified core areas of knowledge that can be learnt effectively by attending autopsy (box).10 Attendance also heightens awareness of the large number of patients with multiple conditions, and the level of uncertainty in medicine11; this experience is not easily gained elsewhere. Furthermore, autopsies raise opportunities to discuss ethical and legal aspects of death and death certification, as well as increasing empathy for dying patients and their families.10,11

Even in the first two years of medical education, the autopsy has been shown to foster deductive reasoning, integration of diverse material, and clinical problem solving.12 These skills are well beyond the focus of pathology.

Most students describe autopsies as educationally useful, although 20% find them distasteful.13 Postgraduate students may also benefit from teaching based on autopsy.6,11

Summary points

Autopsies no longer have a major role in medical teaching and their use has been effectively prohibited in Auckland

Teaching based on autopsy teaches valuable skills, some of which are not easily learnt elsewhere

Doctors who have not had autopsy based teaching as undergraduates are unlikely to request them

Reasons for the decline in autopsy based teaching include limited curriculum time, competing departmental demands and insufficient hospital autopsies.10 Hill and Anderson observed that instructors were unified in their belief in the autopsy as a teaching tool yet constantly finding reasons not to include them in the curriculum.10

Clinical role of autopsy

The autopsy still has a vital role in auditing medical care despite improvements in diagnostic techniques. This is highlighted by studies showing important discrepancies between clinical diagnoses and postmortem findings of patients dying in hospital.14,15 Clinicians may also find it difficult to predict which patients are likely to show such discrepancies.16

However, the fall of autopsy-based teaching has meant that few students are aware of its role in quality control. Indeed, students who graduate without autopsy experience will request an autopsy only if other techniques have failed to show a clear cause of death.17

The autopsy also continues to have an important role in understanding disease and informing public health and research. A recent history cited over 80 major conditions discovered or critically clarified by autopsy since 1950 and suggested there were, perhaps, thousands more minor examples.3

Core skills learnt from autopsies

Clinicopathological correlation

Pathophysiology

Anatomy

Observation skills

Advocating autopsies

Without exposure to autopsy, clinicians are unlikely to become advocates of autopsy6,10 or have the skills necessary for sensitively requesting postmortem examinations.18 The public generally accepts the need for autopsy, but families are unlikely to grant consent if they feel stressed or do not fully understand why a postmortem is required.19 Doctors cannot explain the need if they do not understand it themselves. Concerns about bodily disfigurement from autopsy, which is one of the largest sources of concern for families,6,19 can also often be allayed—for example, by comparing the autopsy to an operation.7 Most religions do not condemn the autopsy.20

Modern politically correct attitudes should pose no barrier to the autopsy. Indeed, such attitudes should be an ally, sharpening sensitivities in communicating with families and encouraging rapid and compassionate communication of results.

References

- 1.Coddington D. Heartbreak hospital. North and South Magazine 2002. Jun: 28-41.

- 2.Loughrey MB, McCluggage WG, Toner PG. The declining autopsy rate and clinicians' attitudes. Ulst Med J 2000;69: 83-9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hill RB, Anderson RE. The recent history of the autopsy. Arch Pathol Lab Med 1996;120: 702-12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Anderson RE, Hill RB. The current status of the autopsy in academic medical centers in the United States. Am J Clin Pathol 1989;92: S31-7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lundberg GD. Medicine without the autopsy. Arch Pathol Lab Med 1984;108: 449-54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Charlton R. Autopsy and medical education: a review. J R Soc Med 1994;87: 232-6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Welsh TS, Kaplan J. The role of postmortem examination in medical education. Mayo Clin Proc 1998;73: 802-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chariot P, Witt K, Pautot V, Porcher R, Thomas G, Zafrani ES, et al. Declining autopsy rate in a French hospital: physicians' attitudes to the autopsy and use of autopsy material in research publications. Arch Pathol Lab Med 2000;124: 739-45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hartmann, HRF, Sebastian M. An argument for the attendance of clinicians at autopsy. Arch Pathol Lab Med 1984;108: 522-3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hill RB, Anderson RE. The uses and value of autopsy in medical education as seen by pathology educators. Acad Med 1991;66: 97-100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Galloway, M. The role of the autopsy in medical education. Hosp Med 1999;60: 756-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sanchez H, Ursell P. Use of autopsy cases for integrating and applying the first two years of medical education. Acad Med 2001;76: 530-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Benbow EW. Medical students' views on necropsies. J Clin Pathol 1990;43: 969-76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Goldman L. Diagnostic advances v the value of the autopsy. Arch Pathol Lab Med 1984;108: 501-5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kirch W, Schafii C. Misdiagnosis at a university hospital in 4 medical eras. Medicine 1996;75: 29-40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kingsford DPW. A review of diagnostic inaccuracy. Med Sci Law 1995;35: 347-51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Botega NJ, Metze K, Marques E, Cruvinel A, Moraes ZV, Augusto L, et al. Attitudes of medical students to necropsy. J Clin Pathol 1997;50: 64-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sherwood SJ, Start RD, Birdi KS, Cotton DWK, Bunce D. How do clinicians learn to request permission for autopsies? Med Educ 1995;29: 231-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sanner MA. In perspective of the declining autopsy rate: attitudes of the public. Arch Pathol Lab Med 1994;118: 878-83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Geller SA. Religious attitudes and the autopsy. Arch Pathol Lab Med 1984;108: 494-6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]