Abstract

Numerous studies have suggested that nitric oxide (NO) in the nucleus tractus solitarii (NTS) participates in modulating cardiovascular function. Nitric oxide synthase (NOS), the enzyme responsible for synthesis of NO, exists in 3 isoforms: endothelial NOS (eNOS), neuronal NOS (nNOS) and inducible NOS (iNOS). While the distribution of nNOS in the NTS has been well documented, the distribution of eNOS in the NTS has not. Because recent studies have shown that eNOS may contribute to regulation of baroreceptor reflexes and arterial pressure, we examined the distribution of eNOS and the types of cells that express it in rat NTS by using multiple-labels for immunofluorescent staining and confocal microscopy. Immunoreactivity (IR) for eNOS and nNOS was found in cells and processes in all NTS subnuclei, but eNOS-IR was more uniformly distributed than was nNOS-IR. Although structures containing either eNOS-IR or nNOS-IR often were present in close proximity, they never contained both isoforms. Almost all eNOS-IR positive structures, but no nNOS-IR positive structures, contained IR for the glial marker glial fibrillary acidic protein. Furthermore, while all nNOS-IR positive cells contained IR for the neuronal marker neuronal nuclear antigen (NeuN), none of the eNOS-IR positive cells contained NeuN-IR. We conclude that eNOS in the NTS is present only in astrocytes and endothelial cells, not in neurons. Our data complement previous physiological studies and suggest that while NO from nNOS may modulate neurotransmission directly in the NTS, NO from eNOS in the NTS may modulate cardiovascular function through an interaction between astrocytes and neurons.

Keywords: endothelial nitric oxide synthase, glial fibrillary acidic protein, immunohistochemistry, inducible nitric oxide synthase, neuronal nitric oxide synthase, neuronal nuclear antigen, nucleus tractus solitarii, rat

Introduction

The nucleus tractus solitarii (NTS), the primary site of termination of cardiovascular and visceral afferent fibers of the vagus and glossopharyngeal nerve, participates in circulatory, ventilatory, gastric, and gustatory control (Bradley et al., 1996; Kalia et al., 1980). Of the numerous putative neurotransmitters that are found in the NTS, nitric oxide (NO) is one of several that have been implicated in cardiovascular signal transduction at that site (Batten et al., 2000; Guyenet, 2006; Lawrence and Jarrott, 1996; Paton et al., 2005; Talman, 1997). NO is synthesized by the enzyme NO synthase (NOS), which exists in 3 isoforms: endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS), neuronal nitric oxide synthase (nNOS), and inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) (Knowles and Moncada, 1994; Moncada and Higgs, 1991). Supporting pharmacological and physiological studies for a role of nNOS in cardiovascular signal transmission in the NTS, nNOS has been found in neurons and fibers of the NTS and in vagal afferents and their terminals in the NTS (Lawrence et al., 1998; Lin et al., 1998; Lin et al., 2000).

The role of eNOS in cardiovascular regulation in the NTS has been implicated in recent studies that utilized gene transfer methodology. Using an adenoviral vector that expresses a dominant negative mutant of eNOS to down-regulate eNOS expression in the NTS, researchers have shown that spontaneous baroreceptor reflex gain was increased, while the heart rate decreased, in rats that had received the vector (Waki et al., 2003; Waki et al., 2006). In addition, the dominant negative mutant of eNOS also prevented angiotensin II-induced baroreflex attenuation (Paton et al., 2001). While these studies have suggested that NO derived from eNOS has an inhibitory effect on baroreflex transmission in the NTS, results of other studies may suggest a different role for NO from eNOS. For example, increasing NO production in the NTS with an adenoviral vector encoding eNOS caused hypotension and bradycardia in conscious rats (Hirooka et al., 2001; Hirooka et al., 2003; Sakai et al., 2000). Although the authors of the later studies utilized eNOS as a tool to study the role of NO in the NTS, their results suggest that NO derived from eNOS may be excitatory in the NTS. Despite these intriguing physiological studies, anatomical data supporting a role for eNOS in signal transduction in NTS is modest. One report briefly mentioned that eNOS positive neurons were not detected by immunohistochemistry in the medulla (Hirooka et al., 2001) while another report showed that eNOS immunoreactivity (IR) was found in neurons of the NTS where it colocalized with angiotensin II-IR (Paton et al., 2001). Because methods to characterize the cells were not used in the latter article, it cannot be affirmed that the eNOS-IR containing cells were indeed neurons. In addition to knowing the cell type, it is also important to know the anatomical relationship between eNOS positive cells and nNOS positive cells in the NTS. Both isoforms are implicated in cardiovascular signal transduction, but the effect of their products may differ. Specifically, as noted, NO synthesized by eNOS may inhibit baroreflex transmission while NO synthesized by nNOS may exert an excitatory effect (Hirooka et al., 2001; Hirooka et al., 2003; Paton et al., 2001; Talman et al., 2001; Talman and Dragon, 2004; Waki et al., 2003). However, a recent study, which showed that adenoviral vectors may transfect glia rather than neurons (Allen et al., 2006), and the study showing augmented baroreflex responses when eNOS was transduced in NTS with adenoviral vectors (Hirooka et al., 2001; Hirooka et al., 2003) suggests that the cellular origin of NO may not alone explain different effects of the compound after its synthesis. Irrespective of the cellular origin of NO from eNOS or nNOS the compound, with its limited diffusion sphere (Garthwaite, 1995), may produce its effects on the baroreflex through actions on similar neuronal structures in the baroreflex pathway. Therefore, we hypothesized that eNOS and nNOS may be localized in structures immediately adjacent to each other or indeed may be colocalized in the same structures. We felt the latter less likely in that different physiological effects of NO derived from the same source would necessitate a single cell’s “packaging” NO from nNOS differently than NO from eNOS in order to effect different responses. We used double fluorescent immunohistochemistry combined with confocal microscopy in the brain stem to examine the distribution of eNOS and nNOS in the NTS and immediately adjacent structures. In a separate immunofluorescent study we sought to determine if iNOS-IR was found in the NTS. Finally we performed triple fluorescent immunostaining for eNOS, nNOS and glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP, a glial marker) or for eNOS, nNOS and neuronal nuclear antigen (NeuN, a neuronal marker) to examine the types of cells that express eNOS and nNOS in the NTS.

Results

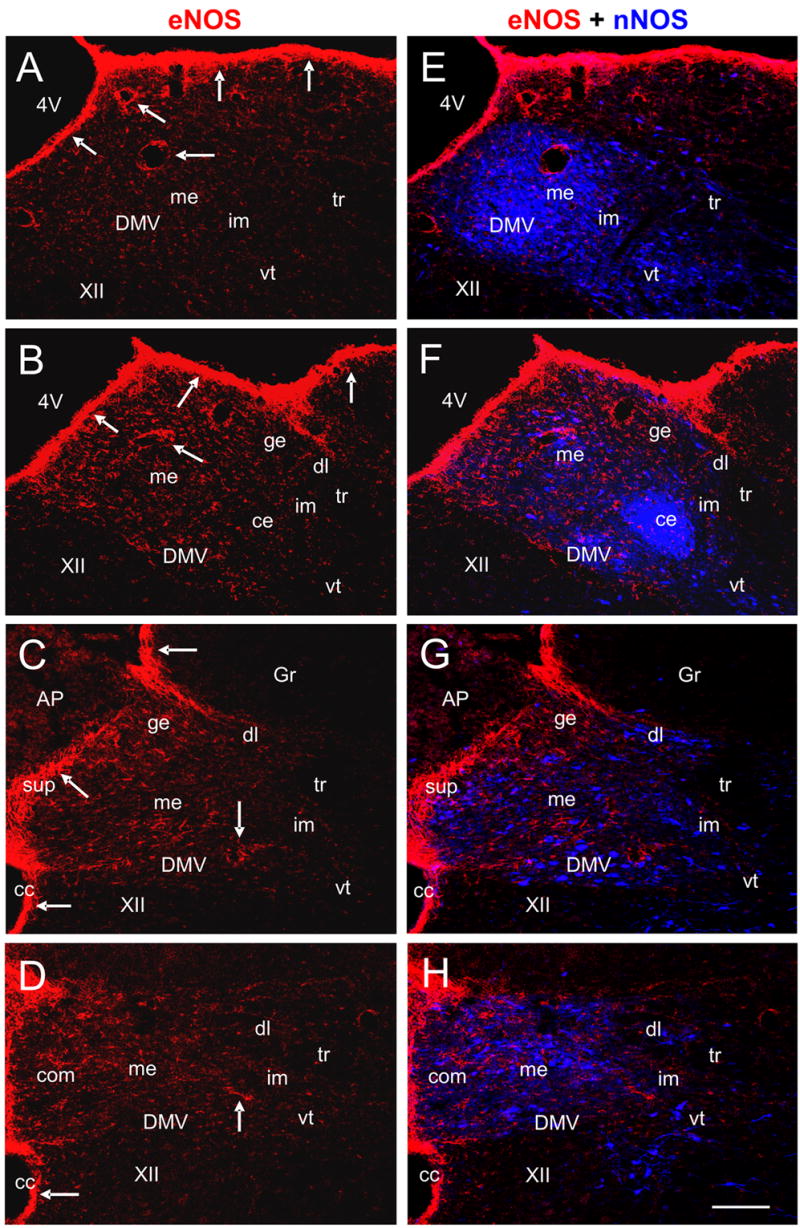

Many brain stem areas contained eNOS-immunoreactivity (IR). These included the NTS, area postrema, nucleus ambiguus, gracilis nucleus, cuneate nucleus, hypoglossal nucleus, and dorsal motor nucleus of vagus (DMV). On the other hand, none of these areas contained noticeable iNOS-IR. Fig. 1E contrasts the lack of iNOS-IR in the NTS, with prominent staining for eNOS-IR (Fig. 1D) and nNOS-IR (Fig. 1F) at the same site. Here we use the terms “intensity” and “levels” to describe the relative amount of immunoreactive labeling in positive structures when they were visually compared to others in the same section. These descriptors do not imply quantification of the respective protein. Very high levels of eNOS-IR were observed on the surface of the brain stem, along the lining of the 4th ventricle, and in blood vessels (Fig. 2). The inner aspect of the central canal also showed a high level of eNOS-IR (Fig. 2). However, at a higher magnification (not shown), we found that eNOS-IR in the region was largely, if not exclusively, in astrocytes that lay below the ependymal cell lining. The medial portion of the subpostrema nucleus, a zone of transition between the NTS and area postrema, also contained very high levels of eNOS-IR (Fig. 2C, 2G and Fig. 3C). Compared with surrounding areas, such as the hypoglossal nucleus and the gracilis nucleus, the NTS and the DMV were more intensely stained for eNOS-IR. In contrast, the nucleus ambiguus contained very low levels of eNOS-IR (not shown).

Fig. 1.

Confocal images in grey scale of immunofluorescent staining for eNOS, iNOS and nNOS in rat NTS. Immunoreactivity (IR) was not observed when primary antibodies were omitted from the incubation mixture (A, B, and C). Marked eNOS-IR (D) and nNOS-IR (F), but not iNOS-IR (E), were noted in the subpostremal level of the NTS when the respective primary antibody was included. Abbreviations: AP, area postrema; DMV, dorsal motor nucleus of vagus; NTS, nucleus tractus solitarii. Scale bar = 100 μm.

Fig. 2.

Low magnification pseudo-colored confocal images of double immunofluorescent staining for eNOS and nNOS in the rat NTS. Panels A to D show eNOS-IR (RRX labeled, red) alone at different levels of the NTS: the rostral (A), intermediate (B), subpostremal (C), and commissural (D) levels. Panels E to H show the merged images of eNOS-IR and nNOS-IR from the same section. Very high levels of eNOS-IR are noted in the subpostremal nucleus, blood vessels, and the outer surface of the brain stem (indicated by arrows in A to D). Compared to nNOS-IR (Cy5 labeled, blue), eNOS-IR in the NTS is more evenly distributed (E–H). Abbreviations: 4V, fourth ventricle; AP, area postrema; cc, central canal; ce, central subnucleus; com, commissural subnucleus; DMV, dorsal motor nucleus of vagus; ge, gelatinosus subnucleus; Gr, gracilis nucleus; me, medial subnucleus; im, intermediate subnucleus; sup, subpostremal nucleus; tr, tractus solitarius, vt, ventral subnucleus; XII, hypoglossal nucleus. Scale bar = 100 μm.

Fig. 3.

Pseudo-colored confocal images showing that eNOS-IR positive cells and processes (red) are not colocalized with neurons and fibers labeled for nNOS-IR (blue) in high magnification in the medial subnucleus (me, panel A), interstitial subnucleus (is, panel B), subpostremal nucleus (sup, panel C), dorsolateral subnucleus (dl, panel D), central subnucleus (ce, panel E) and the dorsal motor nucleus of vagus (DMV, panel F). White open arrows indicate cells or processes that are positive for eNOS-IR alone. Yellow open arrows indicate neurons or fibers that are positive for nNOS-IR alone. Although eNOS-IR and nNOS-IR are not found in the same structures, eNOS-IR containing cells or processes are frequently observed in close proximity of neurons or fibers that are positive for nNOS-IR (indicated by white arrows). Scale bar = 20 μm.

We examined eNOS-IR at different levels of the NTS. As shown in Fig. 2, marked eNOS-IR was observed from rostral to caudal levels of the NTS. In general, the NTS at the intermediate and subpostremal levels had a higher intensity of staining of eNOS-IR than rostral and commissural levels (Fig. 2A–D). For all the coronal sections, the medial parts of the NTS contained a slightly higher intensity of staining of eNOS-IR than did lateral parts of the NTS. There was no discernible difference in the intensity of staining for eNOS-IR among the subnuclei of the NTS (Fig. 2). This finding contrasted with nNOS-IR, whose distribution varied widely amongst those subnuclei (please see our other publications: (Lin et al., 2000; Lin et al., 2004; Lin and Talman, 2002; Lin and Talman, 2005)). However, the medial (Fig. 3A) and dorsolateral (Fig. 3D) subnuclei did demonstrate more intense eNOS-IR than did the interstitial (Fig. 3B), intermediate, central (Fig. 3E), and ventral subnuclei. Images of nNOS-IR alone are not shown in Fig. 2 as nNOS-IR in the NTS has been reported in several of our previous publications (Lin et al., 2000; Lin et al., 2004; Lin and Talman, 2002; Lin and Talman, 2005). Double immunostaining for eNOS and nNOS showed that their IR was located in different cells and fibers and were never colocalized in NTS subnuclei and the DMV (Fig. 3). This contrasting localization was observed even in areas such as the postremal nucleus where there was a high density of eNOS-IR and nNOS-IR containing fibers (Fig. 3C). On the other hand, in all NTS subnuclei and in the DMV, while eNOS-IR and nNOS-IR were not colocalized they were often found in fibers or cells that were very close to and sometimes apposed to, each other (Fig. 3A–F).

Higher magnification images showed that in many brain stem areas eNOS-IR was found in numerous cells that had the morphological appearance of astrocytes. This finding was particularly prominent in NTS subnuclei and in the DMV (Fig. 3). Triple immunostaining for eNOS, nNOS and GFAP confirmed that these cells were astrocytes. Indeed, all eNOS-IR positive cells also contained GFAP-IR (Fig. 4A–D). Neurons and fibers positive for nNOS-IR did not contain GFAP-IR (Fig. 4A–D). In addition, almost all of the numerous eNOS-IR positive processes scattered in NTS subnuclei and the DMV also demonstrated GFAP-IR. Of note, although the majority of GFAP-IR positive cells and processes also contained eNOS-IR, a small number of GFAP-IR positive cells and processes did not contain eNOS-IR.

Fig. 4.

Pseudo-colored confocal images showing triple fluorescent immunostaining for eNOS, nNOS and GFAP (A–D) and for eNOS, nNOS, and NeuN (E–H) in the medial subnucleus of the NTS. Panel D is the merged image of eNOS-IR (red, panel A), nNOS-IR (blue, panel B) and GFAP (green, panel C). Panel H is the merged image of eNOS-IR (red, panel E), nNOS-IR (blue, panel F) and NeuN (green, panel G). (A–D): Almost all eNOS-IR positive cells or processes contained GFAP-IR, but none of the nNOS-IR positive neurons or fibers contained GFAP-IR. White arrows indicate cells or processes that are positive for both eNOS-IR and GFAP-IR. White open arrows indicate processes that contain GFAP-IR alone. Pink open arrows indicate neurons or fibers that are positive for nNOS-IR alone. (E–H): None of the eNOS-IR labeled cells contained NeuN-IR, while almost all nNOS-IR positive neurons also contained NeuN-IR. Blue arrows indicate neurons that are labeled for both nNOS-IR and NeuN-IR. Yellow arrows indicate cells and processes that are positive for eNOS-IR alone. Pink arrows indicate some of the many neurons that contained NeuN-IR alone. Scale bar = 20 μm.

To test if any cells containing eNOS-IR in NTS subnuclei were neurons, we performed triple immunostaining of eNOS, nNOS and NeuN. We found NeuN-IR in all nNOS-IR positive neurons in NTS subnuclei and the DMV, an observation that is consistent with our earlier report (Lin and Talman, 2005). On the other hand, we rarely found NeuN-IR in cells that were eNOS-IR positive (Fig. 4E–H).

Discussion

This study makes several previously unreported observations and may contribute to an understanding of eNOS as a modulator of arterial baroreflex pathways in the NTS. First, the study shows that eNOS-IR positive cells and processes are present in all NTS subnuclei and are distributed differently from that of nNOS-IR positive neurons and fibers. Second, it provides evidence that eNOS-IR is expressed in astrocytes and endothelial cells, but not in neurons, in the NTS. Third, it demonstrates that eNOS-IR and nNOS-IR are found in different cells and processes in the NTS, and are never colocalized. Fourth, it shows that cells and processes expressing eNOS-IR lie in close proximity of neurons and fibers that express nNOS-IR. The study supports the suggestion that the role of eNOS in the NTS may be different from that of nNOS (Paton et al., 2001), and further suggests that if eNOS does affect cardiovascular function, it most likely does so through an interaction between glial cells and neurons.

Our observations here are consistent with a previous report that identified eNOS-IR in the NTS (Paton et al., 2001). However, both studies contrast with another report that eNOS-IR was not found in the NTS (Hirooka et al., 2001). The explanation for the discrepancy between these studies is not clear. The source of the eNOS antibody used in the study that reported a lack of eNOS was not listed in their publication. Our studies utilized an antibody that has been shown to be specific for eNOS in numerous publications (Cao et al., 2001; Luth et al., 2001; Sun and Liao, 2002; Tai et al., 2004). This antibody labeled exclusively one protein band of about 135 kDa in brain tissue assayed by Western blotting (Iwase et al., 2000; Luth et al., 2001; Wiencken and Casagrande, 1999).

To address what type of cells expresses eNOS in the NTS, we examined if these eNOS-IR positive cells contained a glial marker, GFAP, or a neuronal maker, NeuN. The eNOS immunoreactive cells colocalized GFAP and not NeuN, suggesting that they were astrocytes, not neurons. Other studies have shown expression of eNOS in endothelial cells (Chan et al., 2004; Seidel et al., 1997; Shochina et al., 1997) but it has also been found in astrocytes both in culture (Murphy et al., 1990; Sporbert et al., 1999) and in many areas of the brain (Barna et al., 1996; Caillol et al., 2000; Cho et al., 2005; Doyle and Slater, 1997; Gabbott and Bacon, 1996; Iwase et al., 2000; Luth et al., 2001; Wiencken and Casagrande, 1999). For example, astrocytes that expressed eNOS were observed in rat cortex, neocortex, caudate, and putamen, and in mouse brain (Barna et al., 1996; Gabbott and Bacon, 1996; Iwase et al., 2000; Wiencken and Casagrande, 1999). Similarly, in the suprachiasmatic nuclei of Syrian hamsters and rats, a subpopulation of GFAP immunoreactive astrocytes were found to contain eNOS (Caillol et al., 2000). In addition, GFAP expressing cells have also been shown to contain eNOS in the human and mouse hippocampus (Cho et al., 2005; Doyle and Slater, 1997). We found here that the staining pattens of eNOS-IR and the manner in which it colocalized with GFAP-IR in the NTS are parallel with what has been observed in the other areas of the brain in the aforementioned studies.

On the other hand, there are some publications that failed to show eNOS in glial cells in rat brain (Seidel et al., 1997; Topel et al., 1998). Use of different eNOS antibodies in the various studies may explain the discrepancy between results of the current studies and in those that showed eNOS in astrocytes. The studies that reported eNOS in glial cells used commercial polyclonal antibodies from various companies such as Transduction Laboratory, Santa Cruz and Affinity BioReagents. The studies that failed to show eNOS in glial cells used a monoclonal antibody, also from a commercial source. While specificities of eNOS antibodies used were not always verified, many investigators have confirmed the specificity of the antibody we used (Cao et al., 2001; Iwase et al., 2000; Luth et al., 2001; Sun and Liao, 2002; Tai et al., 2004; Wiencken and Casagrande, 1999). Further supporting our finding eNOS in astrocytes are studies that demonstrated NADPH diaphorase activity in eNOS-IR containing astrocytes in rat brain tissue (Gabbott and Bacon, 1996). However, studies that used in situ hybridization and failed to show eNOS mRNA in brain astrocytes (Blackshaw et al., 2003; Seidel et al., 1997) did not support our findings. While in situ hybridization may be free from problems associated with antibodies, the technique may nonetheless lead to false negative results (Bartlett, 2002; Tesch et al., 2006). Therefore, a definitive conclusion whether eNOS is present in astrocytes awaits further investigation.

Finding eNOS in astrocytes suggests that NO synthesized by it may participate in astroglial functions in the central nervous system. Besides helping maintain the blood brain barrier and inducing neuronal synaptogenesis, astrocytes are known to communicate with neurons and modulate communication between neurons (Fellin et al., 2006; Piet et al., 2004; Volterra and Steinhauser, 2004). Studies have suggested that NO generated from eNOS in astrocytes may regulate the association between local cortical activity and local changes in blood flow (Wiencken and Casagrande, 1999). It may also play a major role in photic regulated suprachiasmatic nucleus activity (Caillol et al., 2000). The functions of eNOS in the NTS remain to be fully defined but the enzyme may be associated with angiotensin II regulation of the cardiac baroreflex (Paton et al., 2001), and it may contribute to establishing the set point of arterial pressure in the spontaneous hypertensive rat (Waki et al., 2006). However, its presence in NTS astrocytes, but not neurons, suggests that its role in these functions may be indirect and involve communication between astrocytes and neurons.

This study clearly shows different cellular compartmentalization of eNOS-IR and nNOS-IR and demonstrates that localization of the two isoforms in NTS is similar to that described in other central sites. For example, nNOS has been localized mainly in neurons in the suprachiasmatic nucleus, whereas eNOS has been found in astrocytes in the nucleus (Caillol et al., 2000). The differential localization of eNOS and nNOS suggests that eNOS and nNOS mediate different functions in the NTS. This suggestion was supported by the report of Paton et al., who demonstrated that the angiotensin II-induced baroreceptor reflex depression can be prevented by eNOS specific blockers, but not by an nNOS specific blocker (Paton et al., 2001). On the other hand, although eNOS and nNOS are present in different compartments in the NTS, they are in close proximity, often being found less than 1–2 μm, of each other. Considering the close proximity of these point sources of NO and the highly diffusible nature of the molecule, which may spread as much as a 100 μm from its site of origin (Garthwaite, 1995), it is difficult to reconcile how the same compound released at nearly the same site may lead to such different physiological effects. Indeed, the findings in the current study again raise the possibility that NO may be a component of a larger biologically active compound, which could effect more complex, receptor mediated functions (Lipton et al., 2001; Ohta et al., 1997).

Experimental Procedures

All procedures conformed to standards established in the Guide for Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (National Academy Press, Washington, D.C. 1996). The Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees of the University of Iowa and Department of Veterans Affairs Medical Center, Iowa City reviewed and approved all protocols. Both institutions are AAALAC accredited. All efforts were made to minimize the number of animals used and their suffering.

Animals and tissue preparation

Adult male Sprague Dawley rats (275–340 g, n = 6) were deeply anesthetized with pentobarbital (50 mg/kg, i.p.) and perfused through the heart, first with chilled (4°C) phosphate buffered saline (PBS, pH 7.4, at a flow rate of 20 ml/min) for 2 min, then with freshly prepared chilled 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS for 20 min (also at a flow rate of 20 ml/min). The brain stem was then removed, postfixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 2 hr and then cryoprotected for 2 days in 30% sucrose in PBS at 4°C. Frozen 20 μm coronal sections were cut with a cryostat and processed for double immunofluorescent labeling (eNOS and nNOS; iNOS and nNOS) or triple immunofluorescent labeling (eNOS, nNOS, and GFAP; eNOS, nNOS, and NeuN).

Immunofluorescent labeling

For double immunofluorescent labeling for eNOS and nNOS, brain stem sections were washed with PBS and then blocked with 10% donkey normal serum (Jackson ImmunoResearch, PA) in PBS at 25°C for 1 hr. They were then incubated in a mixture of sheep anti-nNOS antibody (1:1000, K205, a generous gift from Dr. P. C. Emson) and rabbit anti-eNOS antibody (1:50, BD Transduction Labs., CA) in 10% donkey normal serum for 24 hr in a humid chamber at 25°C. The sensitivity and specificity of K205 sheep anti-nNOS antibody has been reported and the antibody has been used in a number of publications (Herbison et al., 1996; Lin et al., 2004; Lin and Talman, 2001; Lin and Talman, 2006; Simonian and Herbison, 1996). The eNOS antibody has also been shown to be specific for eNOS and has been used in many studies (Cao et al., 2001; Luth et al., 2001; Sun and Liao, 2002; Tai et al., 2004). After being washed with PBS, sections were incubated with rhodamine red X (RRX)-conjugated donkey anti-rabbit IgG (for eNOS antibody, 1:200, Jackson ImmunoResearch Labs., PA) or Cy5-conjugated donkey anti-sheep IgG (for nNOS antibody, 1:200, Jackson ImmunoResearch Labs.) in PBS for 20–24 hr at 4°C. Sections were then washed, air-dried, and mounted with Prolong Gold Antifade Reagents (Invitrogen-Molecular Probes, CA).

Similar procedures were used for double immunofluorescent labeling for iNOS and nNOS, except that rabbit anti-iNOS (1:50, BD Transduction Labs.) replaced rabbit anti-eNOS antibody. Like the other antibodies used here, the anti-iNOS antibody is also specific and has been used successfully by others (Mordue et al., 2001; Xie et al., 1992). For triple immunofluorescent labeling of nNOS, eNOS and either GFAP or NeuN, sections were incubated in a mixture of sheep anti-nNOS (1:1000), rabbit anti-eNOS antibody (1:50), and either mouse anti-GFAP (1:100, Sigma-Aldrich, MO) or mouse anti-NeuN (1:100, Millipore-Chemicon, CA). Sections were then incubated in a mixture of RRX-conjugated donkey anti-rabbit IgG, Cy5-conjugated donkey anti-sheep IgG, fluorescein (FITC)-conjugated donkey anti-mouse IgG (1:200, Jackson ImmunoResearch Labs.). Negative controls consisted of tissue processed a) in the absence of primary antibodies or b) after addition of only one of the primary antibodies. In these control experiments, no RRX (for eNOS and iNOS, Fig. 1A and Fig. 1B), or Cy5 (for nNOS, Fig. 1C), or FITC (for GFAP and NeuN, not shown) staining was apparent when the respective antibody had been omitted.

Confocal laser scanning microscopy

Labeled sections were analyzed with a Zeiss LSM 510 confocal laser scanning microscope, which was equipped with an inverted Axiovert 100M microscope, an argon laser (458/488/514 nm, 25 mW), a green helium/neon laser (543 nm, 1 mW) and a red helium/neon laser (633 nm, 5 mW) for excitation of FITC, RRX and Cy5, respectively. The LSM was controlled through a standard high-end Pentium® 4 PC (32 bit Microsoft Windows XP operating system) linking with the electronic control system via an ultrafast SCSI interface. We scanned specimens sequentially by two or three channels to separate labels. For optimal visualization of the relationship between RRX-, Cy5-, and FITC-labeled elements, images from 3 channels were assigned the pseudocolor red (for RRX), green (for fluorescein), or blue (for Cy5) and were superimposed. The pinhole size was set at 100 (at a scale of 0 – 1000) to give the effective optical section thickness of approximately 0.5–1.0 μm. Confocal images were obtained at 100X and 400X magnifications, either with or without zooming functions (1X – 3X), and were processed with software provided with the Zeiss LSM 510. Adobe Photoshop image editing software (Adobe Photoshop CS) was used to examine if a structure was labeled for eNOS, nNOS, GFAP, NeuN or combinations of any two or all three by switching between red, green and blue channels on the monitor. Another image editing program, Microsoft PowerPoint (2003), was used to create montages. Contrast and brightness of images were the only variables we adjusted digitally. Nomenclature used for subnuclei of NTS was based on publications of Kalia and Sullivan (Kalia and Sullivan, 1982) and Paxinos et al. (Paxinos et al., 1999).

Acknowledgments

This study was supported in part by NIH R01 HL59593 and by a VA Merit Review Tab 14.

Abbreviations

- 4V

fourth ventricle

- AP

area postrema

- cc

central canal

- ce

central subnucleus

- com

commissural subnucleus

- dl

dorsolateral subnucleus

- DMV

dorsal motor nucleus of vagus

- eNOS

endothelial nitric oxide synthase

- ge

gelatinosus subnucleus

- GFAP

glial fibrillary acidic protein

- Gr

gracilis nucleus

- im

intermediate subnucleus

- iNOS

inducible nitric oxide synthase

- IR

immunoreactivity

- im

intermediate subnucleus

- iNOS

interstitial nitric oxide synthase

- is

interstitial subnucleus

- me

medial subnucleus

- NeuN

neuronal nuclear antigen

- NO

nitric oxide

- NOS

nitric oxide synthase

- nNOS

neuronal nitric oxide synthase

- NTS

nucleus tractus solitarii

- PBS

phosphate buffered saline

- sup

subpostremal nucleus

- tr

tractus solitarius

- vt

ventral subnucleus

- XII

hypoglossal nucleus

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Allen AM, Dosanjh JK, Erac M, Dassanayake S, Hannan RD, Thomas WG. Expression of constitutively active angiotensin receptors in the rostral ventrolateral medulla increases blood pressure. Hypertension. 2006;47:1054–1061. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000218576.36574.54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barna M, Komatsu T, Reiss CS. Activation of type III nitric oxide synthase in astrocytes following a neurotropic viral infection. Virology. 1996;223:331–343. doi: 10.1006/viro.1996.0484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartlett JM. Approaches to the analysis of gene expression using mRNA: a technical overview. Mol Biotechnol. 2002;21:149–160. doi: 10.1385/MB:21:2:149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Batten TF, Atkinson D, Deuchars J. Nitric oxide systems in the medulla oblongata amd their involvement in autonomic control. In: Steinbusch HWM, De Vente J, Vincent SR, editors. Handbook of Chemical Neuroanatomy. Vol. 17. Elsevier; 2000. pp. 177–212. [Google Scholar]

- Blackshaw S, Eliasson MJ, Sawa A, Watkins CC, Krug D, Gupta A, Arai T, Ferrante RJ, Snyder SH. Species, strain and developmental variations in hippocampal neuronal and endothelial nitric oxide synthase clarify discrepancies in nitric oxide-dependent synaptic plasticity. Neurosci. 2003;119:979–990. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(03)00217-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradley RM, King MS, Wang L, Shu X. Neurotransmitter and neuromodulator activity in the gustatory zone of the nucleus tractus solitarius. Chem Senses. 1996;21:377–385. doi: 10.1093/chemse/21.3.377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caillol M, Devinoy E, Lacroix MC, Schirar A. Endothelial and neuronal nitric oxide synthases are present in the suprachiasmatic nuclei of Syrian hamsters and rats. Eur J Neurosci. 2000;12:649–661. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2000.00961.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao S, Yao J, McCabe TJ, Yao Q, Katusic ZS, Sessa WC, Shah V. Direct interaction between endothelial nitric-oxide synthase and dynamin-2. Implications for nitric-oxide synthase function. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:14249–14256. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M006258200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan Y, Fish JE, D’Abreo C, Lin S, Robb GB, Teichert AM, Karantzoulis-Fegaras F, Keightley A, Steer BM, Marsden PA. The cell-specific expression of endothelial nitric-oxide synthase: a role for DNA methylation. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:35087–35100. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M405063200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho JY, Kim HS, Kim DH, Yan JJ, Suh HW, Song DK. Inhibitory effects of long-term administration of ferulic acid on astrocyte activation induced by intracerebroventricular injection of beta-amyloid peptide (1–42) in mice. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2005;29:901–907. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2005.04.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doyle CA, Slater P. Localization of neuronal and endothelial nitric oxide synthase isoforms in human hippocampus. Neuroscience. 1997;76:387–395. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(96)00297-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fellin T, Sul JY, D’Ascenzo M, Takano H, Pascual O, Haydon PG. Bidirectional astrocyte-neuron communication: the many roles of glutamate and ATP. Novartis Found Symp. 2006;276:208–217. doi: 10.1002/9780470032244.ch16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabbott PL, Bacon SJ. Localisation of NADPH diaphorase activity and NOS immunoreactivity in astroglia in normal adult rat brain. Brain Res. 1996;714:135–144. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(95)01509-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garthwaite J. Neural nitric oxide signalling. Trends Neurosci. 1995;18:51–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guyenet PG. The sympathetic control of blood pressure. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2006;7:335–346. doi: 10.1038/nrn1902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herbison AE, Simonian SX, Norris PJ, Emson PC. Relationship of neuronal nitric oxide synthase immunoreactivity to GnRH neurons in the ovariectomized and intact female rat. J Endocrinol. 1996;8:73–82. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2826.1996.tb00688.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirooka Y, Sakai K, Kishi T, Ito K, Shimokawa H, Takeshita A. Enhanced depressor response to endothelial nitric oxide synthase gene transfer into the nucleus tractus solitarii of spontaneously hypertensive rats. Hypertens Res. 2003;26:325–331. doi: 10.1291/hypres.26.325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirooka Y, Sakai K, Kishi T, Takeshita A. Adenovirus-mediated gene transfer into the NTS in conscious rats. A new approach to examining the central control of cardiovascular regulation. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2001;940:197–205. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2001.tb03677.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwase K, Miyanaka K, Shimizu A, Nagasaki A, Gotoh T, Mori M, Takiguchi M. Induction of endothelial nitric-oxide synthase in rat brain astrocytes by systemic lipopolysaccharide treatment. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:11929–11933. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.16.11929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalia M, Mesulam MM, Mesulam MM. Brain stem projections of sensory and motor components of the vagus complex in the cat: II. laryngeal, tracheobronchial, pulmonary, cardiac, and gastrointestinal branches. J Comp Neurol. 1980;193:467–508. doi: 10.1002/cne.901930211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalia M, Sullivan JM. Brainstem projections of sensory and motor components of the vagus nerve in the rat. J Comp Neurol. 1982;211:248–264. doi: 10.1002/cne.902110304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knowles RG, Moncada S. Nitric oxide synthases in mammals. Biochem J. 1994;298:249–258. doi: 10.1042/bj2980249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence AJ, Castillo-Melendez M, McLean KJ, Jarrott B. The distribution of nitric oxide synthase-, adenosine deaminase- and neuropeptide Y-immunoreactivity through the entire rat nucleus tractus solitarius: Effect of unilateral nodose ganglionectomy. J Chem Neuroanat. 1998;15:27–40. doi: 10.1016/s0891-0618(98)00020-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence AJ, Jarrott B. Neurochemical modulation of cardiovascular control in the nucleus tractus solitarius. Prog Neurobiol. 1996;48:21–53. doi: 10.1016/0301-0082(95)00034-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin LH, Cassell MD, Sandra A, Talman WT. Direct evidence for nitric oxide synthase in vagal afferents to the nucleus tractus solitarii. Neurosci. 1998;84:549–558. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(97)00501-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin LH, Edwards RH, Fremeau RT, Fujiyama F, Kaneda K, Talman WT. Localization of vesicular glutamate transporters colocalizes with and neuronal nitric oxide synthase in rat nucleus tractus solitarii. Neurosci. 2004;123:247–255. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2003.08.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin LH, Emson PC, Talman WT. Apposition of neuronal elements containing nitric oxide synthase and glutamate in the nucleus tractus solitarii of rat: a confocal microscopic analysis. Neurosci. 2000;96:341–350. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(99)00560-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin LH, Talman WT. Colocalization of GluR1 and neuronal nitric oxide synthase in rat nucleus tractus solitarii neurons. Neurosci. 2001;106:801–809. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(01)00331-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin LH, Talman WT. Coexistence of NMDA and AMPA receptor subunits with nNOS in the nucleus tractus solitarii of rat. J Chem Neuroanat. 2002;24:287–296. doi: 10.1016/s0891-0618(02)00069-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin LH, Talman WT. Nitroxidergic neurons in rat nucleus tractus solitarii express vesicular glutamate transporter 3. J Chem Neuroanat. 2005;29:179–191. doi: 10.1016/j.jchemneu.2005.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin LH, Talman WT. Vesicular glutamate transporters and neuronal nitric oxide synthase colocalize in aortic depressor afferent neurons. J Chem Neuroanat. 2006;32:54–64. doi: 10.1016/j.jchemneu.2006.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipton AJ, Johnson MA, Macdonald T, Lieberman MW, Gozal D, Gaston B. S-nitrosothiols signal the ventilatory response to hypoxia. Nature. 2001;413:171–174. doi: 10.1038/35093117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luth HJ, Holzer M, Gartner U, Staufenbiel M, Arendt T. Expression of endothelial and inducible NOS-isoforms is increased in Alzheimer’s disease, in APP23 transgenic mice and after experimental brain lesion in rat: evidence for an induction by amyloid pathology. Brain Res. 2001;913:57–67. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(01)02758-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moncada S, Higgs EA. Endogenous nitric oxide: Physiology, pathology and clinical relevance. Eur J Clin Invest. 1991;21:361–374. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2362.1991.tb01383.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mordue DG, Monroy F, La Regina M, Dinarello CA, Sibley LD. Acute toxoplasmosis leads to lethal overproduction of Th1 cytokines. J Immunol. 2001;167:4574–4584. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.8.4574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy S, Minor RL, Jr, Welk G, Harrison DG. Evidence for an astrocyte-derived vasorelaxing factor with properties similar to nitric oxide. J Neurochem. 1990;55:349–351. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1990.tb08860.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohta H, Bates JN, Lewis SJ, Talman WT. Actions of S-nitrosocysteine in the nucleus tractus solitarii are unrelated to release of nitric oxide. Brain Res. 1997;746:98–104. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(96)01188-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paton JF, Deuchars J, Ahmad Z, Wong LF, Murphy D, Kasparov S. Adenoviral vector demonstrates that angiotensin II-induced depression of the cardiac baroreflex is mediated by endothelial nitric oxide synthase in the nucleus tractus solitarii of the rat. J Physiol (Lond) 2001;531:2–58. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2001.0445i.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paton JFR, Deuchars J, Wang S, Kasparov S. Nitroxergic modulation of visceral afferent signalling in the NTS. In: Undem BJ, Weinreich D, editors. Advances in Vagal Afferent Neurobiology. CRC Press; Boca Raton, Florida: 2005. pp. 209–246. [Google Scholar]

- Paxinos G, Carrive P, Wang H, Wang FL. Chemoarchitectonoic atlas of the rat brainstem. Academic Press; San Diego, CA: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Piet R, Poulain DA, Oliet SH. Contribution of astrocytes to synaptic transmission in the rat supraoptic nucleus. Neurochem Int. 2004;45:251–257. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2003.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakai K, Hirooka Y, Matsuo I, Eshima K, Shigematsu H, Shimokawa H, Takeshita A. Overexpression of eNOS in NTS causes hypotension and bradycardia in vivo. Hypertension. 2000;36:1023–1028. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.36.6.1023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seidel B, Stanarius A, Wolf G. Differential expression of neuronal and endothelial nitric oxide synthase in blood vessels of the rat brain. Neurosci Lett. 1997;239:109–112. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(97)00912-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shochina M, Loesch A, Rubino A, Miah S, Macdonald G, Burnstock G. Immunoreactivity for nitric oxide synthase and endothelin in the coronary and basilar arteries of renal hypertensive rats. Cell Tissue Res. 1997;288:509–516. doi: 10.1007/s004410050836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simonian SX, Herbison AE. Localization of neuronal nitric oxide synthase-immunoreactivity within sub-populations of noradrenergic A1 and A2 neurons in the rats. Brain Res. 1996;732:247–252. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(96)00687-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sporbert A, Mertsch K, Smolenski A, Haseloff RF, Schonfelder G, Paul M, Ruth P, Walter U, Blasig IE. Phosphorylation of vasodilator-stimulated phosphoprotein: a consequence of nitric oxide- and cGMP-mediated signal transduction in brain capillary endothelial cells and astrocytes. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 1999;67:258–266. doi: 10.1016/s0169-328x(99)00067-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun J, Liao JK. Functional interaction of endothelial nitric oxide synthase with a voltage-dependent anion channel. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:13108–13113. doi: 10.1073/pnas.202260999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tai MH, Hsiao M, Chan JY, Lo WC, Wang FS, Liu GS, Howng SL, Tseng CJ. Gene delivery of endothelial nitric oxide synthase into nucleus tractus solitarii induces biphasic response in cardiovascular functions of hypertensive rats. Am J Hypertens. 2004;17:63–70. doi: 10.1016/j.amjhyper.2003.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talman WT. Nitroxidergic transmission in the nucleus tractus solitarii. Ann NY Acad Sci. 1997;835:225–233. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1997.tb48633.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talman WT, Dragon DN. Transmission of arterial baroreflex signals depends on neuronal nitric oxide synthase. Hypertension. 2004;43:820–824. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000120848.76987.ef. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talman WT, Dragon DN, Ohta H, Lin LH. Nitroxidergic influences on cardiovascular control by NTS: a link with glutamate. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2001;940:169–178. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2001.tb03675.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tesch GH, Lan HY, Nikolic-Paterson DJ. Treatment of tissue sections for in situ hybridization. Methods Mol Biol. 2006;326:1–7. doi: 10.1385/1-59745-007-3:1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Topel I, Stanarius A, Wolf G. Distribution of the endothelial constitutive nitric oxide synthase in the developing rat brain: an immunohistochemical study. Brain Res. 1998;788:43–48. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(97)01506-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volterra A, Steinhauser C. Glial modulation of synaptic transmission in the hippocampus. Glia. 2004;47:249–257. doi: 10.1002/glia.20080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waki H, Kasparov S, Wong LF, Murphy D, Shimizu T, Paton JF. Chronic inhibition of endothelial nitric oxide synthase activity in nucleus tractus solitarii enhances baroreceptor reflex in conscious rats. J Physiol (Lond) 2003;546:1–42. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2002.030270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waki H, Murphy D, Yao ST, Kasparov S, Paton JF. Endothelial NO synthase activity in nucleus tractus solitarii contributes to hypertension in spontaneously hypertensive rats. Hypertension. 2006;48:644–650. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000238200.46085.c6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiencken AE, Casagrande VA. Endothelial nitric oxide synthetase (eNOS) in astrocytes: another source of nitric oxide in neocortex. Glia. 1999;26:280–290. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie QW, Cho HJ, Calaycay J, Mumford RA, Swiderek KM, Lee TD, Ding A, Troso T, Nathan C. Cloning and characterization of inducible nitric oxide synthase from mouse macrophages. Science. 1992;256:225–228. doi: 10.1126/science.1373522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]