Abstract

Background

Prior studies suggest racial/ethnic differences in the associations between alcohol misuse and spouse abuse. Some studies indicate that drinking patterns are a stronger predictor of spouse abuse for African Americans but not whites or Hispanics, while others report that drinking patterns are a stronger predictor for whites than African Americans or Hispanics. This study extends prior work by exploring associations between heavy drinking, alcohol-related problems, and risk for spouse abuse within racial/ethnic groups as well as variations associated with whether the perpetrator is drinking during the spouse abuse incident.

Methods

Cases (N = 7,996) were all active-duty male, enlisted Army spouse abusers identified in the Army’s Central Registry (ACR) who had also completed an Army Health Risk Appraisal (HRA) Survey between 1991 and 1998. Controls (N = 17,821) were matched on gender, rank, and marital and HRA status.

Results

We found 3 different patterns of association between alcohol use and domestic violence depending upon both the race/ethnicity of the perpetrator and whether or not alcohol was involved in the spouse abuse event. First, after adjusting for demographic and psychosocial factors, weekly heavy drinking (>14 drinks per week) and alcohol-related problems (yes to 2 or more of 6 alcohol-related problem questions, including the CAGE) were significant predictors of domestic violence among whites and Hispanics only. Also for the white soldiers, the presence of family problems mediated the effect of alcohol-related problems on spouse abuse. Second, alcohol-related problems predicted drinking during a spouse abuse incident for all 3 race groups, but this relation was moderated by typical alcohol consumption patterns in Hispanics and whites only. Finally, alcohol-related problems predicted drinking during a spouse abuse incident, but this was a complex association moderated by different psychosocial or behavioral variables within each race/ethnic group.

Conclusion

These findings suggest important cultural/social influences that interact with drinking patterns.

Keywords: Alcohol, Violence, Intimate Partner Violence, Ethnicity, Race, Army

ALCOHOL AND SPOUSE ABUSE

Alcohol consumption patterns and alcohol-related problems have both been linked to spouse abuse (Bell et al., 2004; Hamilton and Collins, 1981; Hoffman et al., 1994; International Clinical Epidemiologists Network, 2000; Kantor, 1993; Kantor and Straus, 1987, 1989). Alcohol abuse is associated with interpersonal violence (IPV) even when the perpetrator has not consumed alcohol immediately before or during the actual violent event, suggesting that both acute and chronic alcohol exposures are important as well as behaviors (aggression, impulsivity) that may covary with alcohol use patterns (Bell et al., 2004; Caetano et al., 2001b; Cunradi et al., 1999; Hamilton and Collins, 1981; Kantor and Straus, 1987, 1989; Tjaden and Thoennes, 2000). There are a myriad of theories attempting to explain proximal and distal effects of alcohol consumption patterns and alcohol problems on risk for IPV. A review of these theories is beyond the scope of this article but may be obtained through perusal of several well-referenced studies (Bell and Fuchs, 2005; Bell et al., 2004; Brown et al., 1998; Caetano et al., 2001a; Cunradi et al., 2002; Fals-Stewart, 2003; Gleason, 1997; Graham et al., 1998; Gustafson, 1985; Hamilton and Collins, 1981; Jacob and Leonard, 1988; Kantor and Straus, 1987; Leonard et al., 1985; Leonard and Jacob, 1988; Leonard and Quigley, 1999; MacDonald et al., 2000; Murphy et al., 2001; Pan et al., 1994; Quigley and Leonard, 2000; Steele and Josephs, 1990; Testa et al., 2003; White and Chen, 2002; Zhang et al., 2002).

Further complicating matters, there are racial/ethnic subgroup differences in the association between alcohol use and spouse abuse (Bell et al., 2004; Caetano et al., 2000a, 2001a, 2001b; Cunradi et al., 1999; Field and Caetano, 2003; Kantor, 1997). The direction of these associations varies across studies. Some have found that alcohol-related problems are a significant predictor of spouse abuse for African Americans, but not whites (Caetano et al., 2001b; Cunradi et al., 1999). Cunradi et al. (1999) found that when sociodemographic characteristics, psychosocial factors, and typical weekly alcohol consumption were controlled, African American males who report alcohol-related problems [defined using Diagnostics Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders—fourth edition (DSM-IV) criteria based on self-reported symptoms of alcohol dependence as well as selected drinking-related social consequences] were 10 times more likely to also report IPV than African American males without alcohol problems, while the association between alcohol problems and male to female IPV was not statistically significant for white or Hispanic males (Cunradi et al., 1999). Data from the 1995 couples survey also found that alcohol-related problems were a significant predictor of male to female IPV among African American males only (Caetano et al., 2001b). Similarly, a study of married, male active-duty Army soldiers in Alaska found that alcohol-related problems as well as depression and marital discord were more strongly associated with spouse abuse among African American soldiers than white soldiers (Rosen et al., 2002). Drinking during an IPV event may also be more common among African American than white or Hispanic men (Caetano et al., 2000a). Conversely, some data suggest that alcohol consumption patterns, such as heavy drinking, may be less predictive of abuse events among African American perpetrators than among white perpetrators (Caetano et al., 2001a; Cunradi et al., 1999; Field and Caetano, 2003).

The reasons for variations in the association between alcohol use and spouse abuse across racial ethnic groups may be multifaceted but are probably explained by 1 or both of the following moderator or mediator models.

Moderator (Interaction) Model

This model postulates that there are race-related factors that interact with alcohol use and result in different risks for spouse abuse. For example, depression in conjunction with alcohol abuse may have a greater impact on spouse abuse for minorities due to racism. Boyd et al. found that for any level of alcohol consumption ethnic minorities experience greater alcohol problems (Boyd et al., 2003. Herd (1994) found evidence that race was associated with the experience of alcohol-related problems such that African American men reported more problems at given drinking levels than white men in national probability sample. Herd also reports race differences in the interaction between alcohol consumption (heavy drinking) and alcohol problems such that increases in heavy drinking resulted in greater risk for alcohol problems for African American men than for white. Jones-Webb et al. (1997b) found that African American impoverished men experienced more alcohol-related problems than white impoverished men. While economic disparities exist between racial/ethnic groups, studies suggest that these differences do not fully explain the disparity between whites, African Americans, and Hispanics with regard to the negative consequences of alcohol abuse.

Heavy drinking or problem drinking may also result in different long-term trajectories or may differentially impact people of different racial/ethnic backgrounds. For example, Mudar et al. (2002) found that in the first few years of marriage white males who were heavy drinkers reduced their drinking consumption while African American male heavy drinkers drinking remained stable. In addition, white males with alcohol problems reported fewer problems after 2 years of marriage while African American males with alcohol problems reported MORE problems.

There may be race/ethnic differences in utilization and possibly access to treatment services for alcohol problems that could also affect the outcome of alcohol abuse differentially across racial/ethnic groups (Schmidt et al., 2006). There is also evidence of racial differences in susceptibility to dependence [Caetano and Kaskutas, 1995; Galvan and Caetano, 2003; National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA), 2002; White and Jackson, 2004/2005].

Mediator Model

Alcohol abuse may be antecedent to other factors that in turn completely explain the link between alcohol and spouse abuse, and these factors may differ by race/ethnicity. For example, the link between alcohol abuse and spouse abuse may be completely explained by the association between alcohol abuse and psychosocial factors (risk taking, impulsivity, poor cognition, poverty, alcohol expectancy, etc.). Race differences may be explained by differences in the extent to which people of different backgrounds experience these psychosocial factors (Caetano et al., 2001b; Corvo, 2000).

This study relies on data from the U.S. Army. The military is a unique environment where there are prescreening tests and considerable oversight of personal behavior both on and off the job. However, the Army is also one of the nation’s largest employers and includes jobs such as cook, driver, mechanic, nurse, secretary, executive, physician, pilot, and many other jobs that are also found in the civilian sector. Thus, the findings of this study may be relevant to both active-duty soldiers and young employed civilian men. Army personnel are an important study population for several reasons. First, they may be at greater risk for spouse abuse because of their demographic composition and greater exposure to certain risk factors for spouse abuse. The Army population is generally younger and more racially diverse and male than nonmilitary occupational cohorts. In addition, surveys suggest Army soldiers may be more likely to engage in high-risk drinking than their same aged civilian peers (Bray et al., 2003). They may also be at greater risk for severe spouse abuse (Heyman and Neidig, 1999). Finally, it is a useful study population because data are available on alcohol use and other behaviors measured before, and independent of, the spouse abuse event.

The goal of this study is to better understand the relationships between alcohol-related problems, alcohol consumption patterns, race/ethnicity, and spouse abuse. Ultimately this information may be used to build more culturally sensitive theoretical models and intervention strategies.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Data come from the Total Army Injury and Health Outcomes Database (TAIHOD), a collection of files containing demographic and health information on active-duty Army personnel that can be linked through individual identifiers (Amoroso et al., 1997, 1999). Portions of the TAIHOD used in this article include the Army Central Registry (ACR) of child and spouse abuse data, Health Risk Appraisal (HRA) surveys, and personnel records (demographic and discharge information) from the Defense Manpower Data Center (DMDC). Army policy only recognizes incidents of spouse abuse between married persons; therefore, the ACR contains information about IPV between partners if they were married at the time of the event. Case reports are investigated by a multidisciplinary committee at the nearest Army medical treatment facility and substantiated cases are recorded in the ACR. Health Risk Appraisal surveys were completed by subjects prior to, and unrelated to, the spouse abuse incident.

Selection of Cases and Controls

All male, enlisted, active-duty soldiers with a substantiated case of perpetration of spouse abuse between 1991 and 1998 who had no prior substantiated events in the ACR database (i.e., first time reported offenders) comprised the spouse abuse perpetrator group (cases).1,2 All married, enlisted male soldiers who were on active duty at the time of the case incident date but who had no recorded ACR incidents during their time on active duty were eligible to be controls. The spouse abuse incident date was used to match controls and as the point in time when demographic data were collected. There were 24,998 male cases and 64,442 male controls who met the initial criteria for inclusion in this study. Next, we selected cases and controls who had completed a HRA (alcohol and other health behavior measures) before the abuse event date. Approximately 31% of spouse abuse perpetrators (N = 7,761) and 34% of controls (N = 21,786) had taken a HRA before the event date (N = 29,547).

Skip patterns in some of the early versions of the Army’s HRA (nondrinkers skipped the section of the survey about alcohol problems—including the 4-item CAGE), resulted in missing data on alcohol problems for some cases (n = 1,222) and controls (n = 3,845) who were excluded from the analysis. However, there was little demographic variation among samples with and without CAGE data. In addition, 177 soldiers were missing race/ethnicity data. The final study population comprised 24,328 soldiers (6,507 cases and 17,821 controls) with complete alcohol use data on HRAs taken before the spouse abuse event date.

Measures

Alcohol Problems

The Army’s HRA was routinely offered to Army soldiers throughout the 1990s during in-processing to new job assignments, routine physical exams and to entire units as part of the Army’s health and wellness program. Survey items include measures of alcohol-related problems and weekly alcohol consumption (Bell et al., 2002, 2003; Burge and Schneider, 1999; Senier et al., 2003). Six HRA alcohol-related problem questions, including the 4 items comprising the CAGE, were used in this study to define alcohol problems. The CAGE is a 4-item screening measure used to detect alcohol problems (Ewing, 1984). While a positive CAGE screen is not necessarily indicative of alcohol dependence it is a reasonable initial screening tool for alcohol dependence and alcohol problems. To improve sensitivity, responses to 2 additional related questions about consequences of drinking were combined with responses to the 4 CAGE items. These included “Do your friends ever worry about your drinking?” and “Have you ever had a drinking problem?” Respondents answering yes to 2 or more of any of these 6 combined alcohol-related problem items are considered at greater risk for alcohol dependence and defined as positive for “alcohol problems” for purposes of this study. These 6 items showed moderate internal consistency (coefficient α = 0.68).

Alcohol Consumption Patterns

Typical alcohol consumption was assessed by responses to the HRA question, “How many drinks of alcoholic beverages do you have in a typical week?” Responses were grouped into 4 categories based upon published guidelines for safe and unsafe drinking as follows: none (“abstainers”), 1 to 7 drinks, 8 to 14 drinks, and 15 or more drinks per week (“heavy drinkers”) (Campbell et al., 1999; Gordis, 1992; Sanchez-Craig et al., 1995). Although these self-reported items, as well as the weekly alcohol consumption measures, are susceptible to reporting bias, prior work has shown that they display good internal and external validity and are strong predictors of alcohol-related hospitalizations and early separation from service due to alcoholism (Bell et al., 2003).

Psychosocial Factors

Several other HRA measures of social support, social and family problems, and depression were included in this analysis. These items, including the availability of support in general (“How often are there people available that you can turn to for support in bad moments or illness?”), family problems (“How often do you have any serious problems dealing with your husband or wife, parents, friends or with your children?”), job stress (“How often do you feel that your present work situation is putting you under too much stress?”), job satisfaction (“I am satisfied with my present job assignment and unit”), and depressed mood (“In the past year, how often have you experienced repeated or long periods of depression?”) were dichotomized for ease of analysis.

Demographic Factors

Demographic variables were drawn from Army personnel files and included age, race/ethnicity, education, military rank, number of months in grade, and number of dependents. Race was coded white, African American, Hispanic, or other in the DMDC files; however, the “other” category was too small for meaningful comparison. Education was coded as some college or greater versus no college education. Military rank was grouped according to job seniority and responsibility as follows: junior enlisted (E1–E4), mid-level enlisted (E5–E6), and senior enlisted (E7–E9). Months in grade relative to peers was calculated by dividing total time in grade for soldiers in a given pay grade into tertiles and then assigning a category based upon a soldier’s length of time in that pay grade relative to his peers in the same rank category (the group with the average amount of time in grade was used as reference category). Time between date of HRA administration and incident date was grouped into quintiles as follows: 0 to 182; 183 to 444; 445 to 784; 785 to 1,296 days; and 1,297 days or more.

Perpetrator Drinking During the Spouse Abuse Incident

Information about alcohol use by the perpetrator at the time of the spouse abuse incident came from the ACR.

Data Analysis

Logistic regression analysis was used to identify associations between alcohol problems, alcohol consumption patterns, and risk of spouse abuse. A second series of analyses were performed to evaluate risk factors for alcohol-involved spouse abuse events (Caetano et al., 2000a; Cunradi et al., 1999; Field and Caetano, 2003; Jasinski, 2001).

To assess the independent effects of family problems, depressed mood, social supports, and work problems on the risk for spouse abuse, each of these variables was incorporated separately in the full base model (alcohol problems, weekly alcohol consumption, and sociodemographic characteristics). In separate models, we tested for the presence of interactions between alcohol problems and alcohol consumption, family problems, depressed mood, social support, work stress, and job satisfaction. To examine whether the psychosocial items were potential confounders of the association between alcohol problems and spouse abuse, we examined whether the removal of each HRA item resulted in at least a 10% change in the regression coefficient for the risk variable. Analyses were stratified on racial/ethnic background.

Analyses were conducted using SAS version 6 (2000). All analyses for this project adhere to the policies for the protection of human subjects as prescribed in Army Regulation 70–25 and with the provisions of 45 CFR 46.

RESULTS

Race, Alcohol Problems, and Heavy Drinking

African American soldiers (both cases and controls) were at greatest risk for alcohol problems [African American vs white soldiers odds ratio (OR) = 1.26, confidence interval (CI) = 1.16–1.37]; There were no statistically significant differences between Hispanic and white soldiers (OR = 0.94, CI = 0.82–1.07). Although African American soldiers were more likely to report alcohol problems, white soldiers were more likely to report heavier weekly drinking amounts. Typical weekly alcohol use of 8 to 14 (moderate) and 15 or more drinks (heavy) was more common among white than African American or Hispanic soldiers. Typical weekly drinking levels did not differ between African American and Hispanic soldiers (data not shown).

Spouse Abuse, Alcohol Problems, and Heavy Drinking by Race/Ethnicity

Table 1 displays the demographic characteristics of cases and controls within racial/ethnic groups. Factors associated with spouse abuse across all racial/ethnic groups include: self-reported alcohol problems, heavy weekly drinking, fewer years of education, lower rank, younger age, family, problems depression, low social support, and low job satisfaction (Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics of Cases and Controls: Enlisted Male Army Soldiers With HRA Completed Before the Event (1991–1998)

| White

|

African American

|

Hispanic

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | Cases (n = 2,657) % | Controls (n = 10,594) % | Cases (n = 3,141) % | Controls (n = 5,119) % | Cases (n = 709) % | Controls (n = 2,108) % |

| Alcohol problemsa,b | ||||||

| 1 symptom or less | 86.2 | 89.6 | 85.3 | 87.2 | 85.7 | 90.8 |

| 2 or more symptoms | 13.8 | 10.4 | 14.7 | 12.8 | 14.3 | 9.2 |

| Drinks per weekb | ||||||

| None | 32.2 | 33.4 | 33.8 | 35.2 | 32.9 | 37.4 |

| 1 to 7 | 46.3 | 49.1 | 53.1 | 53.6 | 52.1 | 51.8 |

| 8 to 14 | 12.3 | 11.0 | 8.6 | 7.7 | 9.4 | 8.2 |

| 15 or more | 9.2 | 6.5 | 4.5 | 3.5 | 5.6 | 2.6 |

| Educationb | ||||||

| Noncollege | 95.0 | 86.8 | 93.3 | 86.5 | 91.6 | 84.5 |

| College | 5.0 | 13.2 | 6.7 | 13.5 | 8.4 | 15.5 |

| Months in gradeb | ||||||

| Below | 35.6 | 32.1 | 31.3 | 30.5 | 38.3 | 33.5 |

| Average | 33.3 | 34.3 | 34.3 | 32.6 | 31.3 | 32.8 |

| Above | 31.1 | 33.6 | 34.4 | 36.9 | 30.4 | 33.7 |

| Grade | ||||||

| E1 to E4 | 48.9 | 24.3 | 41.3 | 16.1 | 39.4 | 20.3 |

| E5 to E6 | 42.7 | 52.0 | 49.9 | 54.3 | 49.6 | 52.2 |

| E7 to E9 | 8.4 | 23.7 | 8.8 | 29.6 | 11.0 | 27.6 |

| Number dependents | ||||||

| 1 | 30.7 | 30.1 | 27.4 | 21.5 | 24.4 | 21.6 |

| 2 | 28.6 | 25.1 | 28.1 | 24.0 | 27.4 | 23.1 |

| 3 | 23.9 | 26.3 | 23.0 | 29.3 | 24.5 | 30.5 |

| 4 or more | 14.4 | 14.2 | 19.6 | 21.2 | 21.2 | 20.5 |

| Unknown | 2.4 | 4.3 | 1.9 | 4.0 | 2.5 | 4.3 |

| Interval in years between HRA and eventb | ||||||

| <1 year | 32.9 | 26.5 | 32.4 | 26.1 | 31.6 | 23.8 |

| 2 years | 25.0 | 21.5 | 25.2 | 20.2 | 23.4 | 22.9 |

| 3 years | 15.8 | 15.7 | 16.0 | 16.0 | 14.9 | 16.6 |

| 4 years | 10.9 | 11.7 | 10.2 | 11.9 | 12.7 | 12.3 |

| 5 or more years | 15.4 | 24.6 | 16.2 | 25.8 | 17.4 | 24.3 |

| Family problemsb | ||||||

| Never/seldom | 68.5 | 80.7 | 67.1 | 78.6 | 68.2 | 80.3 |

| Sometimes/often | 31.5 | 19.3 | 32.9 | 21.4 | 31.8 | 19.7 |

| Depressed moodb | ||||||

| Never/seldom | 86.9 | 90.7 | 84.9 | 90.1 | 83.3 | 89.1 |

| Sometimes/often | 13.1 | 9.3 | 15.1 | 9.9 | 16.7 | 10.9 |

| Social supportb | ||||||

| Always/sometimes | 87.5 | 91.6 | 87.6 | 90.5 | 88.1 | 90.3 |

| Hardly ever/never | 12.5 | 8.4 | 12.4 | 9.5 | 11.9 | 9.7 |

| Work stressb | ||||||

| Never/seldom | 69.5 | 69.7 | 69.5 | 74.1 | 66.9 | 67.9 |

| Sometimes/often | 30.6 | 30.3 | 30.5 | 25.9 | 33.1 | 32.1 |

| Job satisfactionb | ||||||

| Satisfactory | 69.3 | 71.7 | 62.1 | 65.5 | 70.4 | 71.5 |

| Sometimes/never | 30.7 | 28.3 | 37.9 | 34.4 | 29.6 | 28.5 |

Alcohol problems: comprised of traditional 4 CAGE items (cut down, annoy, guilty, eye opener) plus “friends worry” and “ever have a drinking problem.”

Missing data: White—drinking (20 cases, 77 controls), college (30 cases, 188 controls), family (9 cases, 44 controls), depressed (6 cases, 30 controls), support (17 cases, 90 controls), stress (29 cases, 120 controls), job (36 cases, 130 controls); African American—drinking (41 cases, 48 controls), college (30 cases, 49 controls), family (16 cases, 29 controls), depressed (20 cases, 28 controls), support (42 cases, 77 controls), stress (48 cases, 77 controls), job (57 cases, 75 controls); Hispanic—drinking (5 cases, 16 controls), college (14 cases, 25 controls), family (2 cases, 9 controls), support (1 case, 9 controls), support (9 cases, 31 controls), stress (14 cases, 26 controls), job (7 cases, 30 controls).

HRA, Health Risk Appraisal.

In unadjusted logistic regression models, the odds of perpetrating spouse abuse are greater for soldiers reporting alcohol problems and for soldiers reporting heavy weekly drinking (>14 drinks per week) though the magnitude of the association differed by racial/ethnic group. In general, alcohol problems and typical alcohol consumption patterns were stronger predictors of spouse abuse among white and Hispanic soldiers than among African American soldiers (data not shown).

In multivariate (adjusted) logistic regression models the association between alcohol problems and spouse abuse is statistically significant only among white soldiers and is moderated by the cooccurrence of family problems (Table 2). Family problems were significantly associated with spouse abuse among African American and Hispanic soldiers and among white soldiers who also report alcohol-related problems.

Table 2.

Multivariate Logistic Regression Model: Risk Factors Predicting Perpetration of Spouse Abuse Among Married Active-Duty Enlisted Male Army Soldier with HRA Completed Before the Event (1991–1998)

| Racial/ethnic group [OR (95% CI)]

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | Whitea | African Americanb | Hispanicc |

| Alcohol problemsd | |||

| 1 symptom or less | See interaction below | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 2 symptoms or more | See interaction below | 1.12 (0.96–1.30) | 1.28 (0.95–1.72) |

| Number drinks typical weeka | |||

| None | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 1 to 7 | 1.03 (0.92–1.14) | 1.10 (0.98–1.23) | 1.25 (1.02–1.53) |

| 8 to 14 | 1.19 (1.01–1.39) | 1.10 (0.90–1.34) | 1.19 (0.83–1.69) |

| 15 or more | 1.24 (1.03–1.49) | 1.15 (0.88–1.50) | 1.97 (1.21–3.21) |

| Age in years | 0.90 (0.89–0.92) | 0.89 (0.88–0.90) | 0.94 (0.91–0.96) |

| Educationa | |||

| Noncollege | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| College | 0.67 (0.54–0.82) | 1.11 (0.92–1.34) | 0.80 (0.58–1.11) |

| Months in grade | |||

| Below | 1.11 (1.00–1.25) | 0.92 (0.81–1.04) | 1.10 (0.88–1.37) |

| Average | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Above | 1.03 (0.91–1.16) | 0.97 (0.85–1.10) | 0.97 (0.76–1.24) |

| Grade | |||

| E1 to E4 | 1.92 (1.52–2.42) | 2.06 (1.62–2.62) | 2.47 (1.59–3.84) |

| E5 to E6 | 1.17 (0.97–1.41) | 1.38 (1.15–1.65) | 1.62 (1.16–2.27) |

| E7 to E9 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Number dependents | |||

| 1 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 2 | 1.43 (1.27–1.62) | 1.16 (1.01–1.34) | 1.20 (0.92–1.56) |

| 3 | 1.80 (1.57–2.06) | 1.17 (1.01–1.36) | 1.21 (0.92–1.60) |

| 4 or more | 2.62 (2.23–3.09) | 1.89 (1.61–2.22) | 2.16 (1.58–2.94) |

| Unknown | 1.55 (1.13–2.12) | 0.86 (0.60–1.23) | 1.11 (0.60–2.03) |

| Interval in years between HRA and event | |||

| <1 year | 1.13 (0.97–1.31) | 1.12 (0.96–1.30) | 1.23 (0.92–1.65) |

| 2years | 1.15 (0.99–1.34) | 1.25 (1.07–1.47) | 0.98 (0.72–1.32) |

| 3 years | 1.10 (0.93–1.30) | 1.06 (0.89–1.26) | 0.94 (0.68–1.30) |

| 4 years | 1.14 (0.96–1.37) | 1.08 (0.89–1.39) | 1.24 (0.88–1.74) |

| 5 or more years | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Family problems | |||

| Never/seldom | See interaction below | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Sometimes/often | See interaction below | 1.63 (1.44–1.83) | 1.72 (1.38–2.14) |

| Depressed mood | |||

| Never/seldom | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Sometimes/often | 1.05 (0.90–1.23) | 1.11 (0.95–1.31) | 1.23 (0.92–1.64) |

| Social support | |||

| Always/sometimes | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Hardly ever/never | 1.33 (1.14–1.55) | 1.18 (1.00–1.40) | 0.97 (0.71–1.33) |

| Work stress | |||

| Never/seldom | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Sometimes/often | 0.87 (0.78–0.97) | 1.05 (0.93–1.18) | 1.01 (0.81–1.26) |

| Job satisfaction | |||

| Satisfied | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Somewhat/not satisfied | 1.00 (0.90–1.12) | 0.99 (0.90–1.11) | 0.86 (0.69–1.07) |

| Alcohol problems×Family problems | |||

| Family problems | 0.85 (0.68–1.07) | NA | NA |

| No family problems | 1.39 (1.16–1.66) | NA | NA |

736 observations were deleted from this model due to missing data yielding a total of 12,514 observations.

527 observations were deleted from this model due to missing data yielding a total of 7,733 observations.

179 observations were deleted from this model due to missing data yielding a total of 2,638 observations.

Alcohol problems: comprised of traditional 4 CAGE items (cut down, annoy, guilty, eye opener) plus “friends worry” and “ever have a drinking problem.

HRA, Health Risk Appraisal; NA, not applicable.

The odds for perpetrating spouse abuse are slightly increased among African American soldiers reporting alcohol problems [OR = 1.12 (0.96–1.30)] and Hispanic soldiers [OR = 1.28 (0.95–1.72)] but neither OR achieved statistical significance. Heavy weekly alcohol consumption (15 or more drinks) was a significant risk factor for perpetration of spouse abuse among white and Hispanic soldiers, but not for African American soldiers (Table 2).

For all racial/ethnic groups, younger age, lower rank, and larger families (more dependents) were significantly associated with increased risk for perpetration of spouse abuse. College education was protective against abuse only among white soldiers. Presence of social supports was protective against abuse among white soldiers and bordered on significance among African American soldiers (Table 2).

Risk Factors for Alcohol-Involved Spouse Abuse Incidents

Almost a third (29%) of the perpetrators were drinking during the abuse incident, though percentages varied by racial/ethnic background as follows: white, 34.1%; African American, 24.4%; Hispanic, 31.9%. African American (OR = 0.62; CI = 0.57–0.70) and Hispanic (OR = 0.88; CI = 0.73–1.06) perpetrators were at lower risk for drinking during the spouse abuse incident than white perpetrators, though the Hispanic OR was not statistically significant (data not shown).

Perpetrators reporting alcohol problems on HRA surveys taken well before the spouse abuse incident date were at significantly greater risk of drinking during subsequent spouse abuse events (OR = 1.67). The relationship between race/ethnicity and likelihood of drinking during a spouse abuse incident is influenced by alcohol problems. Self-reported alcohol problems seem to more strongly influence the likelihood of drinking during a spouse abuse incident among African American perpetrators than among white or Hispanic perpetrators. In analyses assessing interactions between racial/ethnic groups, self-reported alcohol problems and likelihood that a perpetrator will drink during the spouse abuse incident, African American perpetrators with alcohol problems were at twice the risk for drinking at the event compared with African American perpetrators who do not report alcohol-related problems (OR = 2.00, CI 1.60–2.50). While white and Hispanic perpetrators who report alcohol-related problems are more likely to be drinking during the spouse abuse incident than white and Hispanic perpetrators who do not report alcohol-related problems the effect size is smaller than that observed for African American perpetrators reporting alcohol-related problems (white, 1.40, CI 1.10–1.78, Hispanic 1.33, CI 0.83–2.12; data not shown).

Although African American perpetrators with alcohol-related problems are at greatest risk for spouse abuse incidents involving drinking (unadjusted OR = 2.00), the association is significant across all 3 racial/ethnic groups (unadjusted white OR = 1.40, unadjusted Hispanic OR = 1.33) (data not shown). However, for white and Hispanic perpetrators, the association is moderated by weekly alcohol consumption patterns. That is, once weekly drinking is taken into account (in models including just the alcohol problems and the weekly alcohol consumption measures), the association between alcohol problems and drinking during a spouse abuse event is no longer significant for white and Hispanic perpetrators. Alcohol problems do remain a significant, independent predictor of drinking at the spouse abuse event for African American perpetrators (alcohol problems OR adjusted for weekly drinking only = 1.75, 95% CI = 1.38–2.21), even after adjusting for weekly alcohol consumption patterns (e.g., heavy drinking; data not shown).

Table 3 displays results from full multivariate models predicting risk for drinking at the abuse incident among perpetrators in each racial/ethnic group. Once all psychosocial factors were taken into account, there was no single variable that uniformly predicted drinking at the abuse event across all racial and ethnic groups. In addition, several race/ethnicity-specific interactions were identified. Where interactions are identified, only the combined effects of the interacting variables should be interpreted. These are presented at the end of the table.

Table 3.

Multivariate Logistic Regression Model: Alcohol Problems and Typical Weekly Drinking Behaviors as Predictors of Drinking During Spouse Abuse Incidents—Adjusted for Demographic, Psychosocial Factors, and Interactions

| Perpetrator Racial/ethnic group [OR (95% CI)]

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | Whitea | African Americanb | Hispanicc |

| Alcohol problemsd | |||

| 1 symptom or less | See interactions | See interactions | See interactions |

| 2 symptoms or more | See interaction | See interactions | See interactions |

| Number drinks typical week | |||

| None | 1.00 | 1.00 | See interactions |

| 1 to 7 | 1.85 (1.49–2.30) | 1.57 (1.27–1.96) | See interactions |

| 8 to 14 | 3.60 (2.66–4.86) | 2.19 (1.48–3.26) | See interactions |

| 15 or more | 3.05 (2.16–4.32) | 1.91 (1.24–3.00) | See interactions |

| Age in years | 1.02 (1.00–1.05) | 1.08 (1.05–1.11) | 1.01 (0.97–1.06) |

| Education | |||

| Noncollege | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| College | 0.76 (0.48–1.19) | 0.93 (0.63–1.37) | 0.49 (0.23–1.04) |

| Months in grade | |||

| Below | 1.03 (0.82–1.28) | 1.08 (0.85–1.37) | 0.72 (0.46–1.12) |

| Average | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Above | 1.17 (0.93–1.48) | 1.17 (0.93–1.47) | 0.66 (0.40–1.09) |

| Grade | |||

| E1 to E4 | 0.73 (0.46–1.16) | See interactions | 0.83 (0.35–1.99) |

| E5 to E6 | 0.81 (0.55–1.18) | 0.96 (0.47–1.95) | |

| E7 to E9 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |

| Number dependents | |||

| One | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 2 | 1.08 (0.85–1.37) | 1.01 (0.78–1.31) | 1.20 (0.71–2.03) |

| 3 | 1.21 (0.94–1.57) | 1.36 (1.03–1.79) | 1.06 (0.61–1.83) |

| 4 or more | 0.88 (0.64–1.20) | 1.27 (0.95–1.70) | 1.03 (0.57–1.88) |

| Unknown | 0.76 (0.40–1.45) | 0.52 (0.22–1.25) | 1.38 (0.40–4.76) |

| Interval in years between HRA and event | |||

| <1 year | See interactions | 1.01 (0.75–1.36) | 1.24 (0.66–2.33) |

| 2 years | See interactions | 1.08 (0.80–1.46) | 1.73 (0.92–3.25) |

| 3 years | See interactions | 1.10 (0.79–1.52) | 1.59 (0.80–3.18) |

| 4 years | See interactions | 0.85 (0.59–1.24) | 1.79 (0.88–3.66) |

| 5 or more years | See interactions | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Family problems | |||

| Never/seldom | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Sometimes/often | 0.77 (0.56–0.86) | 0.82 (0.66–1.02) | 1.28 (0.84–1.96) |

| Depressed mood | |||

| Never/seldom | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Sometimes/often | 0.79 (0.58–1.06) | 0.94 (0.71–1.25) | 0.88 (0.50–1.53) |

| Social support | |||

| Always/sometimes | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Hardly ever/never | 1.05 (0.79–1.42) | 0.82 (0.61–1.10) | 0.86 (0.46–1.59) |

| Work stress | |||

| Never/seldom | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Sometimes/often | 0.92 (0.75–1.14) | 1.02 (0.83–1.27) | 1.18 (0.77–1.80) |

| Job satisfaction | |||

| Satisfactory | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Sometimes/never | 0.98 (0.80–1.21) | 0.94 (0.77–1.16) | 0.89 (0.58–1.37) |

| Alcohol problems×HRA interval | |||

| <1 year | 1.82 (1.17–2.83) | NA | NA |

| 2 years or more | 0.89 (0.64–1.23) | NA | NA |

| Alcohol problems×grade | |||

| E1 to E4 | NA | 2.08 (1.09–3.99) | NA |

| E5 to E6 | NA | 1.50 (1.05–2.15) | NA |

| E7 to E8 | NA | 2.42 (1.69–3.46) | NA |

| Alcohol problems×weekly drinking amount | |||

| 1 to 7 drinks | NA | NA | 0.66 (0.32–1.38) |

| 8 to 14 drinks | NA | NA | 0.45 (0.12–1.73) |

| 15+ drinks | NA | NA | 3.77 (0.38–37.6) |

| No drinks | NA | NA | 3.81 (1.07–13.5) |

125 spouse perpetrators with missing information are excluded from this analysis yielding a total of 2,251 observations.

181 spouse perpetrators with missing information are excluded from this analysis yielding a total of 2,584 observations.

44 spouse perpetrators with missing information are excluded from this analysis yielding a total of 597 observations.

Alcohol problems comprised of traditional 4 CAGE items (cut down, annoy, guilty, eye opener) plus “friends worry” and “ever have a drinking problem.

HRA, Health Risk Appraisal; NA, not applicable.

Among whites, there was a negative interaction between alcohol problems and the amount of time between alcohol use assessment (HRA date) and spouse abuse event date, indicating that more recent assessments of alcohol problems were most strongly predictive of drinking during the spouse abuse event.

Among African American perpetrators, the influence of alcohol problems on risk for drinking at the abuse event was moderated by occupational grade/rank such that the association between alcohol problems and drinking at the event was lower among lower ranking African American perpetrators; alcohol-related problems were more strongly associated with alcohol-involved spouse abuse events among higher ranking African American perpetrators.

For Hispanics, there was a negative interaction between alcohol problems and typical weekly drinking; Hispanic perpetrators who reported both having experienced alcohol-related problems and current abstention from alcohol on health surveys taken well before the spouse abuse incident date were at increased risk for alcohol-involved spouse abuse incidents compared with light or moderate drinking Hispanic perpetrators, suggesting that may relapse and begin consuming alcohol and engage in physical abuse of their spouses concurrently. The odds of drinking at the event were also substantially increased for Hispanics who reported both alcohol problems and heavy drinking patterns on health surveys taken before the spouse abuse incident but, possibly due to small sample size, the OR did not achieve statistical significance [OR = 3.77 (0.38–37.6)]. Thus, it appears there may be 2 Hispanic groups at risk for alcohol-involved spouse abuse incidents: those who report ever having had an alcohol-related problem who are attempting to abstain from alcohol and those who report ever having an alcohol-related problem and are heavy drinkers.

Among other factors predictive of drinking at the abuse incident were typical heavy drinking and older age (white and African American perpetrators). Surprisingly, family problems were protective for white soldiers; White soldiers reporting family problems, while at greater risk for abuse incidents per se, were at lower risk for abuse incidents involving alcohol.

DISCUSSION

This study of male enlisted married soldiers identified associations between spouse abuse perpetration and 2 independent patterns of alcohol use: self-reported alcohol problems and heavy drinking. The associations between self-reported alcohol problems, heavy drinking, and spouse abuse varied by race/ethnicity and by whether the perpetrator was drinking during the abuse incident.

Race, Drinking, and Spouse Abuse

In the unadjusted models, heavy drinking and alcohol problems were both independently associated with spouse abuse across all racial/ethnic groups. Once the models were adjusted for psychosocial and demographic factors, alcohol problems and heavy drinking were no longer statistically significant predictors for African American soldiers. For African American soldiers the initial (unadjusted) association between heavy drinking (alcohol consumption patterns) and spouse abuse was mediated (completely explained) by demographic factors including age, rank, and number of children. These factors also attenuated the influence of alcohol problems but alcohol problems nonetheless remained a significant predictor of spouse abuse for African Americans until we also took into account depressed mood, social support, and family problems. This finding is similar to other studies that found alcohol-related problems to be more predictive of spouse abuse than heavy drinking among African Americans (Cunradi et al., 1999; Field and Caetano, 2003; Rosen et al., 2003). Once demographic and psychosocial factors were accounted for, however, alcohol-related problems also dropped out of the model for African Americans leaving only lower occupational rank, larger families (more dependents), and family problems as key predictors of spouse abuse among African American soldiers. Studies identifying a link between drinking problems and spouse abuse among African American males after controlling for alcohol consumption may be seeing unmeasured associations between drinking problems and depression or family problems.

In incremental model building, we found that the inclusion of either family problems or depressed mood caused alcohol problems to drop out of the model for African Americans only. For white and Hispanic soldiers, the inclusion of either of these variables did not force alcohol problems out of the model, though the family problems variable did cause a notable decrease in the OR for spouse abuse for both whites and Hispanics. In a study of African American and white active-duty, married male Army soldiers, researchers found that depression was more strongly associated with severe spouse abuse perpetration as well as childhood history of abuse for African American soldiers than white soldiers (Rosen et al., 2002).

Heavy drinking patterns were significantly associated with spouse abuse for white and Hispanic soldiers only. Among white and Hispanic soldiers, alcohol use patterns may covary with traditional gender roles and beliefs about power and aggression and thus alcohol may be indirectly related to spouse abuse through the covariance with these other factors. Rosen et al. (2003) found that white males scoring negatively on a masculinity scale were more likely to abuse their spouses than were African American male soldiers. Holtzworth-Munroe and Stuart (1994) suggest that the profile of white spouse abusers may differ from that of African American male abusers such that white perpetrators may be more likely to have narcissistic personality traits and other antisocial behaviors while African American perpetrators may be better characterized as dysphoric and passive (Holtzworth-Munroe and Stuart, 1994).

While we did find an association between drinking patterns and violence among Hispanics in our population, (Caetano et al., 2001a), in nationally representative cross-sectional data did not identify a link between drinking patterns and IPV among Hispanics. The contrast in findings from our study and the Caetano et al. study may be explained in part by differences between military and civilian Hispanic populations. It is possible, for example, that Hispanics in the military are more acculturated than those in a national sample. A study by Caetano et al. (2000b) found that heavy drinking is associated with IPV only among Hispanics with moderate or high levels of acculturation (Caetano et al., 2000b).

Self-reported family problems ascertained sometimes even years before the event appears to be a potent predictor of subsequent risk for spouse abuse among all race/ethnic groups, though it was modified by the cooccurrence of alcohol problems among white soldiers. Family problems may be an indicator or proxy for experiencing childhood abuse among some soldiers. Rosen et al. (2002) found that African American soldiers who had experienced physical or emotional abuse as a child were at increased risk for problems with marital adjustment. It is also possible that IPV at the point when the HRA was administered was already occurring and the report of family problems on the HRA was an earlier indicator of spouse abuse than the ACR event report. The persistent association between family problems and violence across racial/ethnic groups even after controlling for a number of other demographic, psychosocial, and behavioral factors suggests that including a question about family problems during routine health screening might be indicated and may provide an opportunity for earlier detection of problems as well as intervention.

Low social support was a significant risk factor for spouse abuse among white soldiers and bordered on significance for African American soldiers. This is particularly concerning as a study of violence among soldiers at an Alaskan post found that more severe IPV was also associated with self-reported low peer support (Rosen et al., 2003). Military life, with the frequent moves and transitions to new job assignments, different states, and even countries, may pose a particular hardship for soldiers already distressed by family problems or other factors. Low social support, particularly in the context of frequent moves, deserves further research and consideration.

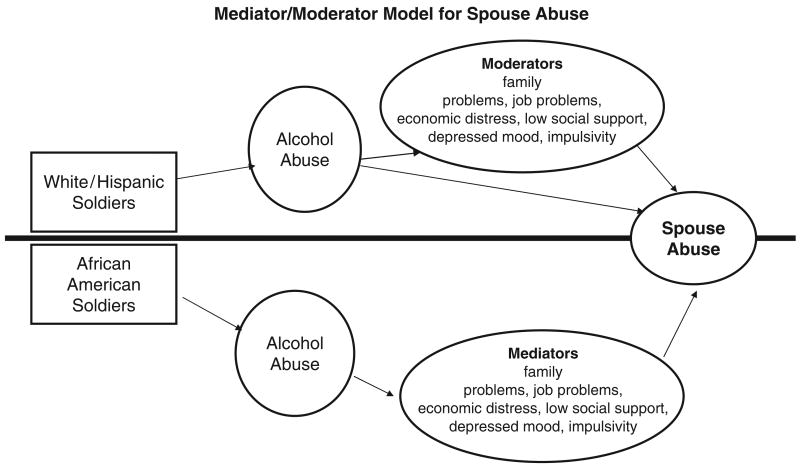

These findings all suggest that there may be 2 different models explaining alcohol and spouse abuse associations based on race/ethnicity (Fig. 1). Results from our study indicate that depression, family problems, and other psychosocial issues fully explain, or mediate, the association between alcohol and spouse abuse for African Americans. For whites and Hispanics these factors serve as moderators of the relationship between alcohol and spouse abuse meaning that the psychosocial variables do not completely explain the relationship between drinking and spouse abuse but they influence the association and they do so in different ways for white versus Hispanic soldiers (see Fig. 1; Baron and Kenny, 1986).

Fig. 1.

The Mediator/Moderator Model postulates that the psychosocial issues fully explain the association between alcohol abuse and spouse abuse for African Americans and modify the association between alcohol and spouse abuse among white and Hispanic soldiers.

Members of minority groups still face greater challenges related to discrimination and social disenfranchisement in our country (Institute of Medicine, 2002; National Research Council, 2004). These experiences may lead directly to alcohol abuse to cope or may lead indirectly to alcohol abuse by contributing to depression. Similarly, these factors could result in alcohol-related problems, interpersonal problems, poverty, or a whole host of other problems. Studies indicate that approval for alcohol varies by race/ethnic groups such that white populations generally have a more tolerant positive viewpoint about alcohol consumption than either African American or Hispanic groups (Caetano and Clark, 1999; Caetano and Kaskutas, 1995; Galvan and Caetano, 2003). Thus, the psychosocial factors that covary with conditions under which some African Americans drink are likely to be very different from those in whites drink. Once psychosocial risk factors associated with minority race are held constant in the model, alcohol is no longer a significant predictor of spouse abuse—it is completely mediated by the other factors. Future research should evaluate the potential role played by alcohol expectancy and traditional gender role identification as well as acculturation in the United States and in the Army.

Race, Drinking, and Alcohol-Involved Spouse Abuse Events

White perpetrators were at substantially greater risk for spouse abuse events involving alcohol. African American soldiers were at substantially lower risk than whites or Hispanics for alcohol-involved events. Hispanics were at lower risk than whites but the difference was not statistically significant. This is consistent with studies of drinking in the United States which generally find that African American males are less likely to be heavy drinkers than white males (Calahan and Room, 1974; Herd, 1994; Sterne, 1967). Conversely, the finding is not consistent with a study that found drinking during the spouse abuse event is more common among African American men than among white or Hispanic (Caetano et al., 2000a). Differences may be attributed to study design (cross-sectional design vs our case–control design where alcohol is measured before and independent of the spouse abuse event), variations in the definition of abuse, reporting bias, or differences in alcohol consumption or race/ethnicity composition in each population (civilian vs military) (Cherpitel, 1995, 1999; Cherpitel and Clark, 1995; Jones-Webb et al., 1997a).

Variations in study findings might also depend upon whether researchers considered effect modifiers. For all 3 racial/ethnic groups, the influence of alcohol problems on the likelihood of drinking during the event was affected by the presence of a third variable (interactions) but these moderating factors varied by race/ethnic group. While African American perpetrators overall were underrepresented among spouse abuse cases involving alcohol, African American perpetrators who report having alcohol problems were more likely than white or Hispanics with alcohol problems to be drinking during spouse abuse events. Thus, alcohol problems among African American soldiers are an important predictor of abuse events involving alcohol, but not for spouse abuse events per se.

These race differences may reflect cultural differences associated with alcohol expectancy—beliefs about how alcohol use affects behavior. Corvo (2000), in a study of African American and white second- and third-grade children in Cleveland, Ohio, found that alcohol expectancies varied significantly by race with African American children being more likely to believe that drinking alcohol would invoke stronger emotional responses and make them more likely to be aggressive or fight. Corvo suggests the finding might reflect variations in how alcohol is marketed to certain African American audiences and neighborhoods. Alcohol expectancy may explain in part greater tendency among African American perpetrators with alcohol dependence to engage in spouse abuse while intoxicated.

These variations may also reflect race-related differences in alcohol problem detection and treatment efficacy. For white perpetrators, alcohol problems were moderated by the time that had elapsed since their alcohol problem status had been assessed. Only white soldiers who had recently been identified with an alcohol problem were at increased risk for alcohol-involved events. This might suggest that early stages of recovery from alcohol problems are a particularly vulnerable period for white soldiers, or it could be that some of these soldiers will “age out” of problematic drinking patterns while African American soldiers with alcohol problems may be less likely to decrease heavy drinking and their alcohol-related problems may not improve or may even get worse over time (Mudar et al., 2002). This may also explain the interaction between alcohol problems and rank. Among African American perpetrators, alcohol problems are associated with abuse events involving alcohol but the association interacts with rank such that soldiers in the highest rank who report alcohol problems are particularly likely to be involved in abuse events where they have been drinking. Alcohol problems and related drinking behaviors that persist over time (as would be necessary in order for the soldier to achieve a higher rank) may be more indicative of alcohol dependence and frequent drinking among African American soldiers. This would also increase the likelihood that they were drinking during the abuse event and may also have resulted in cognitive changes that are associated with chronic alcohol misuse. The association between higher rank, alcohol problems, and alcohol-involved events also mirrors national trends which suggest that African Americans initiate alcohol consumption and achieve peak consumption levels at an older age than whites (Johnston et al., 1995). While African Americans tend to start drinking later in life than whites they are less likely than whites to “age out” of unhealthy drinking habits in general and their drinking habits appear less susceptible to the attenuating affect of getting married than are the drinking habits of white males (Caetano and Kaskutas, 1995; Mudar et al., 2002). Thus, these higher ranking (older) African American soldiers who report alcohol problems may represent the group of African Americans who are at increased risk for maintenance of unhealthy drinking behaviors and associated alcohol problems, or alcohol problems among African Americans may not emerge until they age and move into upper grades. It is also possible that greater rank is a proxy for higher socioeconomic status. Studies suggest that African Americans of higher socioeconomic status report greater racism and racial stress (Forman, 2003).

For Hispanic perpetrators, alcohol problems are associated with increased likelihood of drinking during the event but only among Hispanics who report being abstainers. While a full assessment of the etiology of this association is not possible with this study, we might speculate that this association could indicate a greater tendency toward relapse among Hispanic soldiers with a history of alcohol problems. Others have identified an increased risk for spouse abuse among alcohol abstainers compared with light drinkers particularly among men who approve of physical punishment of their spouse (Kantor and Straus, 1987). It is important to point out that the Hispanic study subpopulation was smallest resulting in reduced power to detect significant associations during subanalysis of alcohol-involved spouse abuse events. Odds of alcohol involvement among Hispanics reporting alcohol problems were greater among those who were both abstainers and heavy drinkers but the latter OR (though greater than 3.0) did not achieve statistical significance. The potential curvilinear association between alcohol consumption patterns and risk for drinking during an abuse event among Hispanics also reporting alcohol problems deserves further study.

Study Limitations And Strengths

The following are limitations of this study. First, the identification of spouse abuse cases may not result in uniform identification of all abuse incidents. Abuse events among soldiers residing on post, for example, may be more likely to be identified; these soldiers may be disproportionately young and of lower rank than soldiers who can afford off-post housing. Similarly, only the more severe cases are likely to be identified. Thus, other studies using a broad population-based survey approach, such as the Conflict Tactics Scale assessment, are likely to identify a broader cross-section of perpetrators. Second, there may be bias in the measurement of drinking at the abuse event. As the determination of alcohol involvement is made after a review of perpetrator and victim testimony, police report, and other interviews, it is possible that there is measurement error and that this error could be systematically biased based upon perpetrator race/ethnicity, age, rank, or other factors. Also, the alcohol problems measures are based on lifetime experience and not necessarily reflective of current drinking problems. Third, the race/ethnicity measure does not take into account heterogeneity of the broad race/ethnicity categories nor are we able to account for degree of acculturation, which has been correlated with risk for IPV (Caetano et al., 2000b; Kantor, 1997). However, one might expect that serving in the U.S. military might facilitate a more rapid assimilation into mainstream U.S. culture. Fourth, the psychosocial factors included in this study (social support, social and family problems, depression, and work problems) are single-item risk assessment factors used in the health risk assessment and have limited reliability and validity assessment (Bell et al., 2002, 2003; Senier et al., 2003). Fifth, because there were no a priori hypothesized interactions in this study and the fact that only a few of the many interactions explored were statistically significant, some caution is warranted, pending future study.

Despite these limitations there are also several notable study strengths. First, the study design measures alcohol use patterns before and independent of spouse abuse case identification. This is an advantage over other studies that use cross-sectional data where both drinking and spouse abuse are measured concurrently. Second, these data come from a large, diverse population with relatively complete data. Some other studies have been hampered by unstable models due to small cell values (Field and Caetano, 2003). Third, while some studies have relied on incarcerated populations, or populations of perpetrators in treatment for substance abuse or violence, this population of Army soldiers is relatively highly functioning and represents a broader cross-section of the general U.S. population than other populations of convenience (Murphy et al., 2001; O’Farrell et al., 2004; Stuart et al., 2003). In addition, Army soldiers have universal access to health care and are all employed. This reduces potential confounding of the relationship between race/ethnicity and spouse abuse.

Acknowledgments

This publication was made possible by Grant R01-AA13324 from the NIAAA. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the Department of Defense, the U.S. Army, or NIAAA. The authors would like to acknowledge Ms. Lauren Komp for her assistance in creating the analytic database and running early descriptive frequencies, Ms. Ilyssa Hollander for her assistance with formatting and manuscript preparation, and Dr. Hayley Thompson at Mount Sinai School of Medicine for careful review of this document and helpful suggestions.

This research has been supported by a grant from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA), Grant R01-AA13324.

Footnotes

Approximately 97% of the active-duty spouse abuse perpetrators in the ACR are enlisted, and approximately 92% are male.

We examined ACR data from 1970 through 1998 and excluded potential cases if they had any abuse records before the study period.

References

- Amoroso PJ, Swartz WG, Hoin FA, Yore MM. Total Army Injury and Health Outcomes Database: Description and Capabilities. U.S: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Army Research Institute of Environmental Medicine. Natick MA, Amoroso PJ, Yore MM, Weyandt B, Jones BH. Chapter 8. Total army injury and health outcomes database: a model comprehensive research database. Mil Med. 1999;164(suppl):1–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baron RM, Kenny DA. The moderator–mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1986;51:1173–1182. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.51.6.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell NS, Fuchs CF. Heavy alcohol consumption and spouse abuse in the army. Joining Forces/Joining Fam. 2005;8:5–6. [Google Scholar]

- Bell NS, Harford T, McCarroll JE, Senier L. Drinking and spouse abuse among U.S. army soldiers. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2004;28:1890–1897. doi: 10.1097/01.ALC.0000148102.89841.9B. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell NS, Williams JO, Senier L, Amoroso PJ, Strowman SR. The U.S. Army’s Health Risk Appraisal (HRA) Survey Part II: Generaliz-ability, Sample Selection, and Bias. U.S. Army Research Institute of Environmental Medicine; Natick, MA: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Bell NS, Williams JO, Senier L, Strowman SR, Amoroso PJ. The reliability and validity of the self-reported drinking measures in the army’s health risk appraisal survey. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2003;27:826–834. doi: 10.1097/01.ALC.0000067978.27660.73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Unequal Treatment: Confronting Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care. The National Academies Press; Washington, DC: 2002. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Measuring Racial Discrimination: Panel on Methods for Assessing Discrimination. The National Academies Press; Washington, DC: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Boyd MR, Phillips K, Dorsey CJ. Alcohol and other drug disorders, comorbidity, and violence: comparison of rural African American and Caucasian women. Arch Psychiatr Nurs. 2003;17:249–258. doi: 10.1053/j.apnu.2003.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bray RM, Hourani LL, Rae KL, Dever JA, Brown JM, Vincus AA, Pemberton MR, Marsden ME, Faulkner DL, Vandermaas-Peeler R. 2002 Department of Defense Survey of Health Related Behaviors Among Military Personnel. Research Triangle Institute; Research Triangle Park, NC: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Brown TG, Werk A, Caplan T, Shields N, Seraganian P. The incidence and characteristics of violent men in substance abuse treatment. Addict Behav. 1998;23:573–586. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(98)00004-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burge SK, Schneider FD. Alcohol-related problems: recognition and intervention. Am Fam Physician. 1999;59:361–70. 372. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caetano R, Clark CL. Trends in situational norms and attitudes toward drinking among whites, blacks, and Hispanics: 1984–1995. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1999;54:45–56. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(98)00148-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caetano R, Cunradi CB, Clark CL, Schafer J. Intimate partner violence and drinking patterns among white, black, and Hispanic couples in the U.S. J Subst Abuse. 2000a;11:123–138. doi: 10.1016/s0899-3289(00)00015-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caetano R, Kaskutas LA. Changes in drinking patterns among whites, blacks and Hispanics, 1984–1992. J Stud Alcohol. 1995;56:558–565. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1995.56.558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caetano R, Nelson S, Cunradi C. Intimate partner violence, dependence symptoms and social consequences from drinking among white, black and Hispanic couples in the United States. Am J Addict. 2001a;10(suppl):60–69. doi: 10.1080/10550490150504146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caetano R, Schafer J, Clark C, Cunradi C, Raspberry K. Intimate partner violence, acculturation, and alcohol consumption among Hispanic couples in the United States. J Interpers Violence. 2000b;15:30–45. [Google Scholar]

- Caetano R, Schafer J, Cunradi CB. Alcohol-related intimate partner violence among white, black, and Hispanic couples in the United States. Alcohol Res Health. 2001b;25:58–65. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calahan D, Room R. Problem Drinking among American Men. Rutgers Center for Alcohol Studies; New Brunswick, NJ: 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell NR, Ashley MJ, Carruthers SG, Lacourciere Y, McKay DW. Lifestyle modifications to prevent and control hypertension. 3. Recommendations on alcohol consumption. Canadian Hypertension Society, Canadian Coalition for High Blood Pressure Prevention and Control, Laboratory Centre for Disease Control at Health Canada, Heart and Stroke Foundation of Canada. Can Med Assoc J. 1999;160(suppl):S13–S20. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cherpitel CJ. Analysis of cut points for screening instruments for alcohol problems in the emergency room. J Stud Alcohol. 1995;56:695–700. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1995.56.695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cherpitel CJ. Gender, injury status and acculturation differences in performance of screening instruments for alcohol problems among US Hispanic emergency department patients. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1999;53:147–157. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(98)00122-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cherpitel CJ, Clark WB. Ethnic differences in performance of screening instruments for identifying harmful drinking and alcohol dependence in the emergency room. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1995;19:628–634. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1995.tb01559.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corvo K. Variation by race in children’s alcohol expectancies. J Subst Abuse. 2000;11:1–5. doi: 10.1016/s0899-3289(99)00024-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunradi CB, Caetano R, Clark CL, Schafer J. Alcohol-related problems and intimate partner violence among white, black, and Hispanic couples in the U.S. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1999;23:1492–1501. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunradi CB, Caetano R, Schafer J. Alcohol-related problems, drug use, and male intimate partner violence severity among US couples. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2002;26:493–500. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ewing JA. Detecting alcoholism. The CAGE questionnaire. JAMA. 1984;252:1905–1907. doi: 10.1001/jama.252.14.1905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fals-Stewart W. The occurrence of partner physical aggression on days of alcohol consumption: a longitudinal diary study. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2003;71:41–52. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.71.1.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Field CA, Caetano R. Longitudinal model predicting partner violence among white, black, and Hispanic couples in the United States. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2003;27:1451–1458. doi: 10.1097/01.ALC.0000086066.70540.8C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forman TA. The social psychological costs of racial segmentation in the workplace: a study of African Americans’ well-being. J Health Soc Behav. 2003;44:332–352. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galvan FH, Caetano R. Alcohol use and related problems among ethnic minorities in the United States. Alcohol Res Health. 2003;27:87–94. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gleason WJ. Psychological and social dysfunctions in battering men: a review. Aggression Violent Behav. 1997;2:43–52. [Google Scholar]

- Gordis E. Moderate Drinking—A Commentary, in Alcohol Alert. National Institute of Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism; Bethesda, MD: 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Graham K, Leonard KE, Room R, Wild TC, Pihl RO, Bois C, Single E. Current directions in research on understanding and preventing intoxicated aggression. Addiction. 1998;93:659–676. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.1998.9356593.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gustafson R. Alcohol and aggression: pharmacological versus expectancy effects. Psychol Rep. 1985;57(3 part 1):955–966. doi: 10.2466/pr0.1985.57.3.955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton CJ, Collins JJ., Jr . The role of alcohol in wife beating and abuse: a review of the literature. In: Collins JJ Jr, editor. Drinking and Crime: Perspectives on the Relationships between Alcohol Consumption and Criminal Behavior. Guilford Press; New York: 1981. pp. 253–287. [Google Scholar]

- Herd D. Predicting drinking problems among black and white men: results from a national survey. J Stud Alcohol. 1994;55:61–71. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1994.55.61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heyman RE, Neidig PH. A comparison of spousal aggression prevalence rates in the U.S. Army and civilian representative samples. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1999;67:239–242. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.67.2.239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman MJ, Demo DH, Edwards JN. Physical wife abuse in a nonwestern society: an integrated theoretical approach. J Marriage Fam. 1994;56:131–146. [Google Scholar]

- Holtzworth-Munroe A, Stuart G. Typologies of male batterers: three subtypes and the differences among them. Psychol Bull. 1994;116:476–497. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.116.3.476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smedley BD, Stith AY, Nelson AR, editors. Institute of Medicine. Unequal Treatment in Health: Confronting Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2003. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- International Clinical Epidemiologists Network. Domestic violence in India. A summary report of a multi-site household survey. International Centre for Research on Women; Washington: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Jacob T, Leonard KE. Alcoholic–spouse interaction as a function of alcoholism subtype and alcohol consumption interaction. J Abnorm Psychol. 1988;97:231–237. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.97.2.231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jasinski JL. Physical violence among Anglo, African American, and Hispanic couples: ethnic differences in persistence and cessation. Violence Vict. 2001;16:479–490. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG. National Survey Results on Drug Use from the Monitoring the Future study 1975–1994. Volume I: Secondary School Students. National Institute on Drug Abuse; Rockville, MD: 1995. p. 316. [Google Scholar]

- Jones-Webb R, Hsiao CY, Hannan P, Caetano R. Predictors of increases in alcohol-related problems among black and white adults: results from the 1984 and 1992 National Alcohol Surveys. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 1997a;23:281–299. doi: 10.3109/00952999709040947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones-Webb R, Snowden L, Herd D, Short B, Hannan P. Alcohol-related problems among black, Hispanic and white men: the contribution of neighborhood poverty. J Stud Alcohol. 1997b;58:539–545. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1997.58.539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kantor GK. Refining the brushstrokes in portraits of alcohol and wife assaults. In: Martin SE, editor. Alcohol and Interpersonal Violence: Fostering Multi-disciplinary Perspectives. NIAAA Res Monogr 24. National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism; Rockville: 1993. pp. 281–290. [Google Scholar]

- Kantor GK. Alcohol and spouse abuse ethnic differences. In: Galanter M, editor. Recent Developments in Alcoholism Volume 13: Alcoholism and Violence. Vol. 13. Plenum Press; New York: 1997. pp. 57–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kantor GK, Straus MA. The “drunken bum” theory of wife beating. Soc Problems. 1987;34:213–231. [Google Scholar]

- Kantor GK, Straus MA. Substance abuse as a precipitant of wife abuse victimizations. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 1989;15:173–189. doi: 10.3109/00952998909092719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leonard KE, Bromet EJ, Parkinson DK, Day NL, Ryan CM. Patterns of alcohol use and physically aggressive behavior in men. J Stud Alcohol. 1985;46:279–282. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1985.46.279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leonard KE, Jacob T. Alcohol, alcoholism, and family violence. In: Van Hasselt VB, Morrison RL, Bellack AS, Hersen M, editors. Handbook of Family Violence. Plenum Press; New York: 1988. pp. 383–406. [Google Scholar]

- Leonard KE, Quigley BM. Drinking and marital aggression in newlyweds: an event-based analysis of drinking and the occurrence of husband marital aggression. J Stud Alcohol. 1999;60:537–545. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1999.60.537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacDonald G, Zanna MP, Holmes JG. An experimental test of the role of alcohol in relationship conflict. J Exp Soc Psychol. 2000;36:182–193. [Google Scholar]

- Mudar P, Kearns JN, Leonard KE. The transition to marriage and changes in alcohol involvement among black couples and white couples. J Stud Alcohol. 2002;63:568–576. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2002.63.568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy CM, O’Farrell TJ, Fals-Stewart W, Feehan M. Correlates of intimate partner violence among male alcoholic patients. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2001;69:528–540. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.69.3.528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. Alcohol and minorities: an update. Alcohol Alert. 2002;55:1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Blank RM, Dabady M, Citro CF, editors. National Research Council. Measuring Racial Discrimination: Panel on Methods for Assessing Discrimination. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- O’Farrell TJ, Murphy CM, Stephan SH, Fals-Stewart W, Murphy M. Partner violence before and after couples-based alcoholism treatment for male alcoholic patients: the role of treatment involvement and abstinence. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2004;72:202–217. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.72.2.202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan HS, Neidig PH, O’Leary KD. Predicting mild and severe husband-to-wife physical aggression. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1994;62:975–981. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.62.5.975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quigley BM, Leonard KE. Alcohol and the continuation of early marital aggression. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2000;24:1003–1010. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosen LN, Kaminski RJ, Moore Parmley A, Knudson KH, Fancher P. The effects of peer group climate on intimate partner violence among married male U.S. army soldiers. Violence Against Women. 2003;9:1045–1071. [Google Scholar]

- Rosen LN, Parmley AM, Knudson KH, Fancher P. Intimate partner violence among married male U.S. Army soldiers: ethnicity as a factor in self-reported perpetration and victimization. Violence Vict. 2002;17:607–622. doi: 10.1891/vivi.17.5.607.33716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez-Craig M, Wilkinson DA, Davila R. Empirically based guidelines for moderate drinking: 1-year results from three studies with problem drinkers. Am J Public Health. 1995;85:823–828. doi: 10.2105/ajph.85.6.823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SAS. SAS. 8.2. SAS Institute Inc; Cary, NC: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt L, Greenfield T, Mulia N. Unequal treatment: racial and ethnic disparities in alcoholism treatment services. Alcohol Res Health. 2006;29:49–54. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Senier L, Bell NS, Schempp C, Strowman SR, Amoroso PJ. The U.S. Army’s Health Risk Appraisal Survey Part I: History, Reliability, and Validity. U.S. Army Research Institute of Environmental Medicine; Natick, MA: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Steele CM, Josephs RA. Alcohol myopia. Its prized and dangerous effects. Am Psychol. 1990;45:921–933. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.45.8.921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sterne MW. Drinking patterns and alcoholism among American Negroes. In: Pitman DJ, editor. Alcoholism. Harper & Row; New York: 1967. pp. 66–99. [Google Scholar]

- Stuart GL, Moore TM, Kahler CW, Ramsey SE. Substance abuse and relationship violence among men court-referred to batterers’ intervention programs. Subst Abuse. 2003;24:107–122. doi: 10.1080/08897070309511539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Testa M, Quigley BM, Leonard KE. Does alcohol make a difference? Within-participants comparison of incidents of partner violence. J Interpers Violence. 2003;18:735–743. doi: 10.1177/0886260503253232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tjaden P, Thoennes N. Extent, Nature, and Consequences of Intimate Partner Violence. National Institute of Justice; Rockville, MD: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- White HR, Chen PH. Problem drinking and intimate partner violence. J Stud Alcohol. 2002;63:205–214. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2002.63.205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White HR, Jackson K. Social and psychological influences on emerging adult drinking behavior. Alcohol Res Health. 20042005;28:182–190. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L, Welte JW, Wieczorek WW. The role of aggression related alcohol expectancies in explaining the link between alcohol and violent behavior. Subst Use Misuse. 2002;37:457–471. doi: 10.1081/ja-120002805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]