The ability of cancer cells to proliferate in the absence of adhesion to extracellular matrix (ECM)1 proteins, termed anchorage independence of growth, correlates closely with tumorigenicity in animal models (14). This property of cancer cells presumably reflects the tendency of tumor cells to survive and grow in inappropriate locations in vivo. Such incorrect localization, as occurs in invasion and metastasis, is the characteristic that distinguishes malignant from benign tumors (31).

Great progress has been made in the last 20 years toward understanding how growth is controlled in normal cells and how oncogenes usurp these controls. Yet studies on how oncogenes (or loss of tumor suppressors) overcome the mechanisms that govern cellular location have lagged considerably. The finding that integrins transduce signals that influence intracellular growth regulatory pathways provided some insight into anchorage dependence. Available evidence indicates that integrin-dependent signals mediate the growth requirement for cell adhesion to ECM proteins.

Our understanding of integrin signaling has now reached a stage that connections to oncogenesis are becoming clear, enabling us to place a number of proto-oncogenes and oncogenes with respect to their adhesion dependence or independence. While many details of molecular mechanisms remain to be elucidated, sufficient information is now available to propose a general framework for how oncogenes lead to anchorage-independent growth.

Integrin Signaling

Integrins transduce a great many signals that impinge upon growth regulatory pathways (for review see 3, 37, 44). These include activation of tyrosine kinases such as focal adhesion kinase (FAK), pp60src, and c-Abl; serine-threonine kinases such as MAP kinases, jun kinase (JNK), and protein kinase C (PKC); intracellular ions such as protons (pH) and calcium; the small GTPase Rho; and lipid mediators such as phosphoinositides, diacylglycerol, and arachidonic acid metabolites. Integrin-mediated adhesion also regulates expression of immediate-early genes such as c-fos and key cell cycle events such as kinase activity of cyclin–cdk complexes and phosphorylation of the retinoblastoma protein (Rb).

It is striking that extensive investigations into integrin-dependent pathways have revealed no novel signaling pathways. Integrins appear to regulate the same pathways that have been identified in studies of oncogenes and growth factors. Mediators such as c-src, phosphoinositides, protein kinase C, and so on were well established as participants in cytokine or growth factor–dependent signaling. Even FAK, p130cas, and paxillin, which localize to focal adhesions and mediate integrin signaling, connect downstream to known growth factor–regulated pathways such as phosphatidylinositol (PI) 3-kinase (for FAK) and MAP kinase (for FAK, paxillin, and p130cas). Thus, integrins and growth factors regulate the same pathways. This fact then raises the question of how these pathways are jointly controlled by both cell adhesion to ECM proteins and soluble factors.

Convergence of Integrin and Growth Factor Pathways

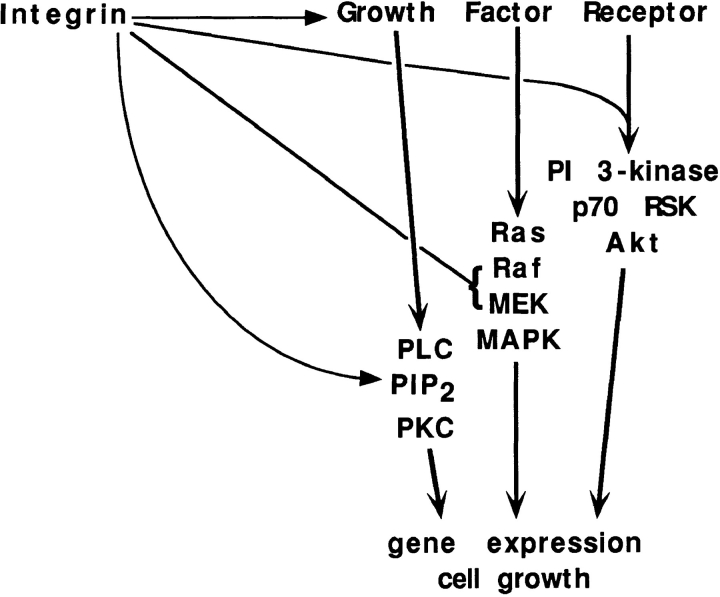

In many if not most instances where the combined effects of soluble factors and integrins have been examined, synergistic activation has been observed. Cell adhesion has been shown to greatly enhance autophosphorylation of the EGF and PDGF receptors in response to their cognate ligands (10, 23). In cells where growth factor receptor function is not affected by ECM, activation of PKC via hydrolysis of phosphoinositides depends on cell adhesion (22, 34). Cell adhesion regulates transmission of signals to MAP kinase by altering the activation of MEK or Raf (20, 30). There is also evidence that activation of PI 3-kinase and downstream components such as AKT and p70RSK in response to growth factors depends on cell adhesion (17, 18). Thus, at least three major signaling pathways controlled by growth factors also require cell adhesion (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Convergence of integrin and growth factor receptor pathways. Integrin-mediated adhesion regulates transmission of growth factor receptor signals in at least four steps. These steps are: autophosphorylation and activation of the receptors themselves; hydrolysis of phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate (PIP2) to produce diacylglycerol and inositol triphosphate, leading to activation of protein kinase C (PKC); activation of Raf and/or MEK in the MAP kinase pathway; and activation of PI 3-kinase, leading to activation of p70RSK and Akt protein kinases.

In the cases listed above, the combined output from integrins and growth factors is synergistic. Thus, the response to either cell adhesion or growth factors alone is quite low in most cases, while both stimuli together give a strong response. These results imply that integrins and growth factor receptors act upon different points in the pathway. For example, in the case of inositol lipid hydrolysis, integrins control the synthesis and supply of phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate, whereas growth factor receptors control the activity of phospholipase C (22).

Many other instances of synergism have been observed. Integrin αvβ3 coprecipitates with IRS-1 after stimulation with insulin, and though the mechanism of the cooperation is unclear, this coprecipitation correlates with enhanced mitogenesis in response to insulin (39). Leukocyte activation in response to cytokines and antigens is also enhanced by cell adhesion, and in several cases, cell activation correlates with synergistic effects on protein tyrosine phosphorylation (for review see 32).

Expression of early cell cycle genes such as c-fos and c-myc is also stimulated by both cell adhesion and growth factors (12). Gene expression driven by the fos promoter shows strongly synergistic activation by integrin-mediated adhesion and growth factors (41). Later cell cycle events such as activation of G1 cyclin–cdk complexes and Rb phosphorylation require both cell adhesion to ECM and growth factors (for review see 3). There are also numerous examples in which complex cellular functions such as migration, proliferation, gene expression, or differentiation require stimulation by both integrin-mediated adhesion and soluble factors (for review see 1, 6, 13).

Implications for Oncogenes

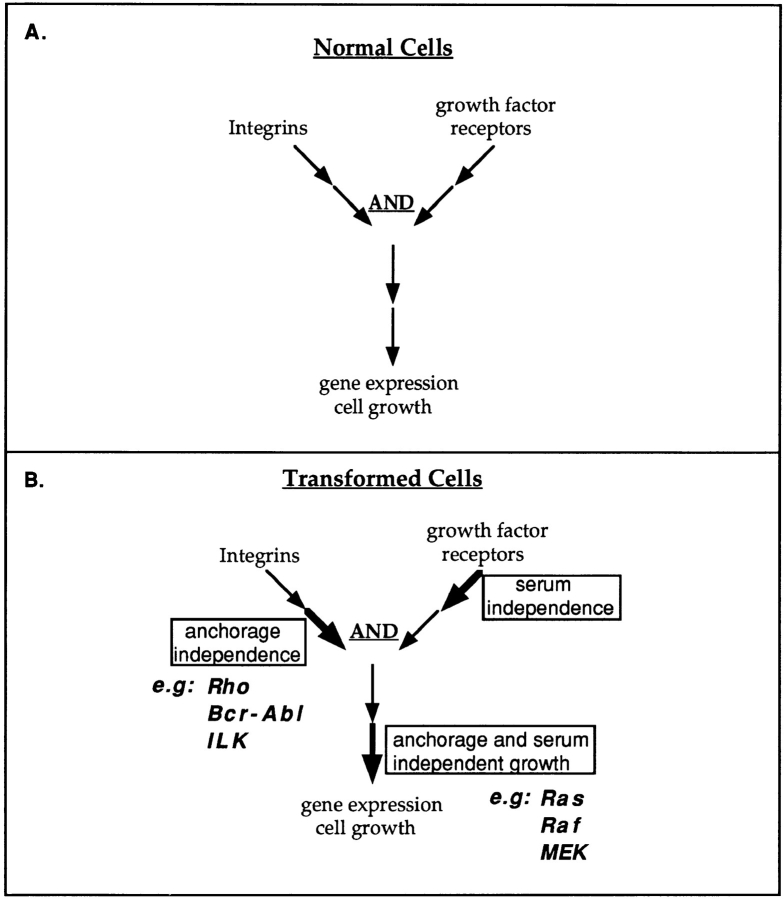

The pathways in Fig. 1 can be represented in a general way as shown in Fig. 2 A. This figure displays a basic conceptual framework for considering effects of integrins and growth factors on cell functions. Because oncogenes are points on normal growth regulatory pathways that are constitutively activated by mutation or overexpression, one can make predictions about the effects of oncogenes on cell growth based on the placement of the corresponding proto-oncogenes with respect to the integrin and growth factor receptor pathways. For example, constitutive activation of a step after convergence of integrin and growth factor pathways should bypass the requirements for both adhesion and serum, i.e., it should induce both serum- and anchorage-independent proliferation. Oncogenes such as Ras, src, or SV40 large T antigen appear to fit this description.

Figure 2.

Oncogenes and signaling pathways. (A) General scheme for convergence of integrin and growth factor–dependent pathways in which both are required for activation of gene expression and cell growth. (B) Constitutive activation is indicated by the boldface arrow. Activation of a step on the integrin arm of a pathway should lead to anchorage-independent growth, as illustrated by the behavior of Rho, Bcr-Abl, and ILK. Activation of a step on the growth factor receptor arm of the pathway should lead to serum independence. Activation of a step after convergence should induce both anchorage- and serum-independent growth.

On the other hand, constitutive activation of a step on the integrin arm of the pathway before convergence should give rise to anchorage-independent but serum-dependent growth. A number of oncogenes have recently been found to fit this description. Activation of Rho leads to anchorage-independent but serum-dependent growth (38), consistent with results suggesting that Rho mediates integrin-dependent signaling (4, 8, 29). The Rho family protein Cdc42 gives similar effects (26), and recent work suggests that Cdc42 is activated by integrins and plays an important role in cell spreading and cytoskeletal organization (Price, L., J. Leng, M. Schwartz, and G. Bokoch, manuscript submitted for publication; Clark, E., W. King, J. Brugge, M. Symons, and R. Hynes, manuscript in preparation). An activated variant of FAK was also shown to induce anchorage-dependent survival and growth of MDCK cells without altering their dependence on serum (15). Overexpression of the 70-kD integrin-linked kinase, a protein that was found to bind directly to integrin cytoplasmic domains, also induces anchorage-independent but serum-dependent growth (27).

The Abl tyrosine kinase provides a particularly interesting example. Chronic myelogenous leukemia (CML) is caused by the Philadelphia chromosomal translocation, which fuses Bcr to the NH2 terminus of c-Abl to produce the Bcr-Abl oncogene (for review see 40). CML cells exit the bone marrow and enter the circulation prematurely, where they proliferate excessively. Thus the behavior of CML cells is reminiscent of anchorage-independent growth in vitro. Indeed, expression of Bcr-Abl in 3T3 cells induced anchorage-independent but serum-dependent growth (28). Consistent with these results, c-Abl localization and tyrosine kinase activity are regulated by integrin-mediated cell adhesion (19). Thus, at least some of the behavior of Bcr-Abl can be understood as constitutive activation of c-Abl's adhesion-dependent functions.

Conversely, one would predict that constitutive stimulation of growth factor pathways would be mitogenic but not necessarily oncogenic. Such mutations might give rise to benign tumors, where cells show accelerated growth but their structure and behavior remain relatively normal (31). Production of autocrine growth factors is a prime candidate for effects of this sort. In support of this model, ectopic expression of growth factors in vivo induces benign hyperplasia in several animal models (7, 21, 33); in some cases neoplasia results but occurs at a later stage and arises focally, indicating a requirement for additional mutations (33). In vitro, autocrine growth factor expression can also be associated with accelerated or serum-independent growth of otherwise normal cells (24). Circumstances where autocrine expression of growth factors lead to anchorage independence are discussed below.

The Plot Thickens

The conceptual scheme shown in Fig. 2 is simple, but signaling pathways may not be. The proto-oncogene c-src, for example, associates both with growth factor receptors and with FAK (2, 9, 43). Oncogenic variants of src induce tyrosine phosphorylation both of focal adhesion proteins and proteins involved in growth factor receptor signaling (16). Thus, a multifunctional tyrosine kinase like src might phosphorylate substrates that independently induce anchorage and serum independence.

Second, incorrect targeting or compartmentalization of a signaling protein may result in novel functions that do not occur under normal conditions. For example, attachment of a membrane localization sequence to c-Abl (as in v-Abl or mutant forms of Bcr-Abl) creates a much more potent oncogene that strongly induces both anchorage- and serum-independent growth (11, 28), most likely by phosphorylating substrates that are normally inaccessible.

Third, very strong activation of a pathway may overcome a partial blockade. For example, loss of integrin- mediated adhesion inhibits the activation of MAP kinase by serum or active forms of Ras or Raf by 75–90% (20, 30). However, oncogenic Ras or Raf activate the pathway two to three times more strongly than serum. Hence, ERK activation in suspended Ras- or Raf-transformed cells is ∼40% of that obtained in adherent cells treated with serum. These oncogenes can therefore induce a significant degree of anchorage independence. It should be noted, however, that the rate of growth of suspended transformed cells is still much slower than when they are adherent.

An obvious question stemming from this model is why do oncogenes that derive from growth factors or receptors sometimes induce complete transformation of fibroblast cell lines. For example, expression of v-sis, which codes for PDGF-B, promotes growth in soft agar, even though addition of PDGF to the medium does not (25, 42). This question may be resolved by the observation that v-sis stimulation of the PDGF receptor in an intracellular compartment is crucial to its transforming activity (5). This result makes the prediction that intracellular receptors might evade some of the adhesion-dependent controls discussed above, thereby enabling v-sis to stimulate growth of nonadherent cells.

Summary and Conclusions

Some of the earliest experiments identifying signals from integrins showed that oncogenes were able to activate these pathways in suspended cells (16, 35, 36). Thus, anchorage-independent growth of tumor cells could be seen as a consequence of anchorage-independent activation of specific pathways. Recent advances have shown that this view is basically correct but have considerably enriched our understanding. Integrins and growth factor receptors regulate the same pathways, in many instances in such a way that ligation of both is required for activation of downstream events. Oncogenes that constitutively activate integrin-dependent events before convergence with growth factor pathways should induce anchorage-independent growth without affecting serum dependence. Conversely, activation of growth factor–dependent events before convergence should induce accelerated proliferation without causing anchorage independence. And constitutive activation of events after convergence should result in both anchorage and serum independence.

These predictions have been tested in several instances. Rho, FAK, Cdc42, ILK, and c-Abl have been implicated in integrin signaling, and activation or overexpression of these proteins induces anchorage-independent but serum-dependent growth. Activation of MAP kinase, PI 3-kinase, expression from the c-fos promoter, kinase activity of cyclin D- and cyclin E–cdk complexes, and Rb phosphorylation all depend on both adhesion and growth factors, and oncogenes such as v-fos, v-Ras , v-src, and SV40 large T that constitutively activate these pathways induce both anchorage and serum independence. That these oncogenes are potent transforming agents may be due in part to their ability to overcome cellular requirements for both anchorage and growth factors.

The majority of deaths from cancer are due not to primary tumors but to secondary tumors that arise via invasion and metastasis. The ability of tumor cells to survive and grow in inappropriate environments therefore lies very much at the core of the problem. This behavior is reflected in vitro by anchorage-independent growth. Constitutive activation of integrin-dependent signaling events by oncogenes provides a molecular explanation for the link between growth and adhesion.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grants RO1 GM47214 and PO1 HL48728.

Abbreviations used in this paper

- CML

chronic myelongenous leukemia

- ECM

extracellular matrix

- FAK

focal adhesion kinase

- PI

phosphatidylinositol

- Rb

retinoblastoma protein

Footnotes

Address all correspondence to Martin A. Schwartz, Department of Vascular Biology, The Scripps Research Institute, 10550 N. Torrey Pines Road, La Jolla, CA 92037. Tel.: (619) 784-7140. Fax: (619) 784-7360. E-mail: schwartz@scripps.edu

I am grateful to Sanford Shattil, Mark Ginsberg, and Josephine Adams for critical reading of the manuscript and to Bette Cessna for expert secretarial assistance. I thank many colleagues for making unpublished work available.

References

- 1.Adams JC, Watt FM. Regulation of development and differentiation by the extracellular matrix. Development. 1993;117:1183–1198. doi: 10.1242/dev.117.4.1183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anderson D, Koch CA, Grey L, Ellis C, Moran MF, Pawson T. Binding of SH2 domains of phospholipase Cγ1, GAP and src to activated growth factor receptors. Science (Wash DC) 1990;250:979–981. doi: 10.1126/science.2173144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Assoian RK. Anchorage-dependent cell cycle progression. J Cell Biol. 1997;136:1–4. doi: 10.1083/jcb.136.1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barry ST, Flinn HM, Humphries MJ, Critchley DR, Ridley AJ. Requirement for Rho in integrin signalling. Cell Adhes Commun. 1997;4:387–398. doi: 10.3109/15419069709004456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bejcek BE, Li DY, Deuel TF. Transformation by v-sis occurs by an internal autoactivation mechanism. Science (Wash DC) 1989;245:1496–1499. doi: 10.1126/science.2551043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carey DJ. Control of growth and differentiation of vascular cells by extracellular matrix. Annu Rev Physiol. 1991;53:161–177. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ph.53.030191.001113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chang JM, Metcalf D, Gonda TJ, Johnson GR. Long-term exposure to retrovirally expressed granulocyte-colony-stimulating factor induces a nonneoplastic granulocytic and progenitor cell hyperplasia without tissue damage in mice. J Clin Invest. 1989;84:1488–1496. doi: 10.1172/JCI114324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chong LD, Traynor-Kaplan A, Bokoch GM, Schwartz MA. The small GTP-binding protein Rho regulates a phosphatidylinositol 4-phosphate 5-kinase in mammalian cells. Cell. 1994;79:507–513. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90259-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cobb BS, Schaller MD, Leu TH, Parsons JT. Stable association of pp60src and pp50fyn with the focal adhesion associated protein tyrosine kinase pp125FAK. Mol Cell Bio. 1994;14:147–155. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.1.147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cybulsky AV, McTavish AJ, Cyr MD. Extracellular matrix modulates epidermal growth factor receptor activation in rat glomerular epithelial cells. J Clin Invest. 1994;94:68–78. doi: 10.1172/JCI117350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Daley GQ, McLaughlin J, Witte ON, Baltimore D. The CML-specific p210 bcr/abl protein, unlike v-abl, does not transform NIH 3T3 cells. Science (Wash DC) 1987;237:532–535. doi: 10.1126/science.2440107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dike LE, Farmer SR. Cell adhesion induces expression of growth-associated genes in suspension-arrested fibroblasts. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1988;85:6792–6796. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.18.6792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Donjacour AA, Cunha GR. Stromal regulation of epithelial function. Cancer Treat Res. 1991;53:335–364. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4615-3940-7_16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Freedman VH, Shin S. Cellular tumorigenicity in nude mice: correlation with cell growth in semisolid medium. Cell. 1974;3:355–359. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(74)90050-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Frisch SM, Vuori K, Ruoslahti E, Chan PY. Control of adhesion dependent cell survival by focal ahesion kinase. J Cell Biol. 1996;134:793–799. doi: 10.1083/jcb.134.3.793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Guan J-L, Shalloway D. Regulation of pp125FAK both by cellular adhesion and by oncogenic transformation. Nature (Lond) 1992;358:690–692. doi: 10.1038/358690a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Khwaja A, Rodriguez-Viciana P, Wennstrom S, Warne PH, Downward J. Matrix adhesion and Ras transformation both activate a phosphoinositide 3-OH kinase and protein kinase B/Akt cellular survival pathway. EMBO (Eur Mol Biol Organ) J. 1997;16:2783–2793. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.10.2783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Koyama H, Raines EW, Bornfeldt KE, Roberts JM, Ross R. Fibrillar collagen inhibits arterial smooth muscle proliferation through regulation of cdk2 inhibitors. Cell. 1996;87:1069–1078. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81801-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lewis JM, Renshaw MW, Taagepera S, Baskaran R, Schwartz MA, Wang JYJ. c-Abl tyrosine kinase in integrin-dependent signal transduction. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:15174–15179. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.26.15174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lin TH, Chen Q, Howe A, Juliano RL. Cell anchorage permits efficient signal transduction between ras and tis downstream kinases. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:8849–8852. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lloyd RV, Jin L, Chang A, Kulig E, Camper SA, Ross BD, Downs TR, Frohman LA. Morphologic effects of hGRH gene expression on the pituitary, liver, and pancreas of MT-hGRH transgenic mice. An in situ hybridization analysis. Am J Pathol. 1992;141:895–906. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McNamee HM, Ingber DE, Schwartz MA. Adhesion to fibronectin stimulates inositol lipid synthesis and enhances PDGF-induced inostol lipid breakdown. J Cell Biol. 1992;121:673–678. doi: 10.1083/jcb.121.3.673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Miyamoto S, Teramoto H, Gutkind JS, Yamada KM. Integrins can collaborate with growth factors for phosphorylation of receptor tyrosine kinases and MAP kinase activation: roles of integrin aggregation and occupancy of receptors. J Cell Biol. 1996;135:1633–1642. doi: 10.1083/jcb.135.6.1633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Modrowski D, Lomri A, Marie PJ. Endogenous GM-CSF is involved as an autocrine growth factor for human osteoblastic cells. J Cell Physiol. 1997;170:35–46. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4652(199701)170:1<35::AID-JCP5>3.0.CO;2-M. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Potapova O, Fakhrai H, Baird S, Mercola D. Platelet-derived growth factor-B/v-sis confers a tumorigenic and metastatic phenotype to human T98G glioblastoma cells. Cancer Res. 1996;56:280–286. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Qiu RG, Abo A, McCormick F, Symons M. Cdc42 regulates anchorage-independent growth and is necessary for Ras transformation. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:3449–3458. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.6.3449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Radeva G, Petrocelli T, Behrend E, Leung-Hagesteijn C, Filmus J, Slingerland J, Dedhar S. Overexpression of the integrin-linked kinase promotes anchorage-independent cell cycle progression. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:13937–13944. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.21.13937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Renshaw MW, McWhirter JR, Wang JYJ. The human leukemia oncogene bcr-abl abrogates the anchorage requirement but not the growth factor requirement for proliferation. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15:1286–1293. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.3.1286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Renshaw MW, Toksoz D, Schwartz MA. Involvement of the small GTPase Rho in integrin-mediated activation of MAP kinase. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:21691–21694. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.36.21691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Renshaw, M.W., X.D. Ren, and M.A. Schwartz. 1997. Activation of the MAP kinase pathway by growth factors requires integrin-mediated cell adhesion. EMBO (Eur. Mol. Biol. Organ.) J. In press.

- 31.Robbins, S.L., R.S. Cotran and V. Kumar. 1984. Neoplasia. In Pathologic Basis of Disease. W.B. Saunders. Philadelphia, PA.

- 32.Rosales C, Juliano RL. Signal transduction by cell adhesion receptors in leukocytes. J Leukocyte Biol. 1995;57:189–198. doi: 10.1002/jlb.57.2.189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sandgren EP, Luetteke NC, Palmiter RD, Brinster RL, Lee DC. Overexpression of TGF α in transgenic mice: induction of epithelial hyperplasia, pancreatic metaplasia, and carcinoma of the breast. Cell. 1990;61:1121–1135. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90075-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schwartz MA, Lechene C. Adhesion is required for protein kinase C-dependent activation of the Na-H antiporter by platelet-derived growth factor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:6138–6141. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.13.6138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schwartz MA, Both G, Lechene C. The effect of cell spreading on cytoplasmic pH in normal and transformed fibroblasts. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1989;86:4525–4529. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.12.4525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schwartz MA, Rupp EE, Frangioni JV, Lechene CP. Cytoplasmic pH and anchorage independent growth induced by v-Ki-ras, v-src or polyoma middle T. Oncogene. 1990;5:55–58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schwartz MA, Schaller MD, Ginsberg MH. Integrins: emerging paradigms of signal transduction. Ann Rev Cell Biol. 1995;11:549–599. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cb.11.110195.003001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schwartz MA, Toksoz D, Khosravi-Far R. Transformation by Rho exchange factor oncogenes is mediated by activation of an integrin-dependent pathway. EMBO (Eur Mol Biol Organ) J. 1996;15:6525–6530. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Vuori K, Ruoslahti E. Association of insulin receptor substrate-1 with integrins. Science (Wash DC) 1994;266:1576–1578. doi: 10.1126/science.7527156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wang JYJ. Abl tyrosine kinase in signal transduction and cell cycle regulation. Curr Opin Gen Dev. 1993;3:35–43. doi: 10.1016/s0959-437x(05)80338-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wary KK, Maneiro F, Isakoff SJ, Marcantonio EE, Giancotti FG. The adapter protein Shc couples a class of integrins to the control of cell cycle progression. Cell. 1996;87:733–743. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81392-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Williams LT. The sis gene and PDGF. Cancer Surv. 1986;5:233–241. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Xing Z, Chen H-C, Nowlen JK, Taylor SJ, Shalloway D, Guan J-L. Direct interaction of v-src with the focal adhesion kinase mediated by the src SH2 domain. Mol Biol Cell. 1994;5:413–421. doi: 10.1091/mbc.5.4.413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yamada KM, Miyamoto S. Integrin transmembrane signaling and cytoskeletal control. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1995;7:681–689. doi: 10.1016/0955-0674(95)80110-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]